-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Reconstructive and esthetic breast surgery after solid organ transplantation – a systematic review, proposal of a novel protocol and case presentations

Authors: B. Basso Robertino; Eugenia Maria Salto; F. Mayer Horacio

Authors place of work: Plastic Surgery Department, University of Buenos Aires School of Medicine, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires University Institute, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Published in the journal: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 63, 3, 2021, pp. 102-112

doi: https://doi.org/10.48095/ccachp2021102Introduction

Great advancements in solid organ transplantation (SOT) have allowed patients to have better chances to survive longer and enjoy a quality life after surgery. The number of organ transplant recipients all around the world has risen annually, with a 7.25% overall increase between 2015 and 2017 [1]. This increasing number of SOTs and improved long-term survival rates lead to an increasing demand for plastic, esthetic and reconstructive procedures. Furthermore, improved surgical techniques and the development of immunosuppressive agents have also fueled this trend [2,3]. Nevertheless, the use of immunosuppressive agents in patients undergoing esthetic and reconstructive surgeries might result in more complications if compared to patients who are not treated with these drugs [4]. These problems require special attention and should not be underestimated.

Studies on reconstructive and esthetic plastic breast surgery in SOT recipients seems scanty. In this study, a systematic literature review with summarized outcomes from the available studies is presented. On the other hand, there is no protocol to define specific precautions when performing general esthetic and reconstructive surgery on transplant organ recipients. Therefore, we summarized special considerations regarding immunosuppressive therapy as well as perioperative management when performing breast procedures presenting a novel protocol. Representative cases of breast plastic surgery in transplant recipients are also presented.

Material and methods

In January 2020, a literature search was conducted across three databases using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar were systematically used searching the following terms: "allotransplantation", "solid organ transplant", "organ transplantation", "transplant recipient", "plastic surgery", "reconstructive surgical procedures", "breast cancer", "mastectomy", "breast surgery", "breast reduction", "breast augmentation", "breast reconstruction", "mammoplasty" and "mastopexy".

The inclusion criteria were limited to articles with clinical data of esthetic and reconstructive breast surgery in SOT patients with detailed description of reported cases. Articles that were not written in English were excluded. Two researchers carefully scrutinized to determine which of these articles were relevant to the study and evaluated with respect to the inclusion criteria, and any disagreements were resolved through consensus with a third reviewer. References from included articles were also examined for additional studies of interest. Fig. 1 illustrates the complete search process that followed the PRISMA guidelines [5].

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram depicting the flow of information through the different phases of our systematic review.

PRISMA – Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Included articles were then analyzed to extract data points of interest including patient age, type of surgery, organ transplanted, underlying conditions associated with organ transplantation, follow-up, immunosuppressive drugs and their side effects, perioperative management and complications related to the breast plastic procedures in SOT recipients.

Results

Bibliographic search

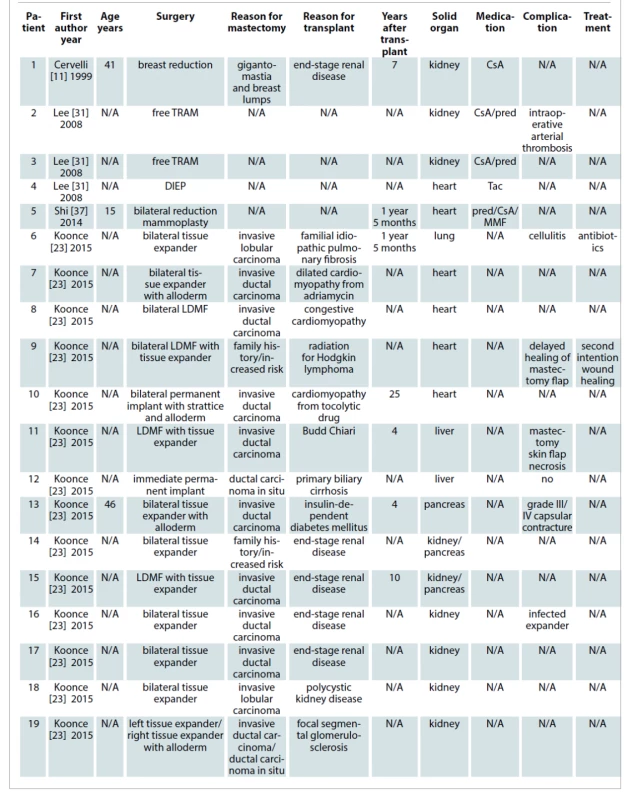

A total of 1,298 articles were retrieved from the mentioned electronic databases. Duplicated studies and abstracts not-related to our search were removed resulting in 111 citations full-text for review. Eight full articles were finally included in this systematic review based on the described search strategy. In these articles, a total of 41 cases of breast plastic surgery after solid organ transplantation were reported. Those represented more than one surgery in cases that required a second stage reconstruction. The average patient age was 41.9 years (range 15–65 years). The time after SOT until breast surgery ranged from 16 months to 25 years (average time 7.26 years). The procedures were esthetic in nature in 26.83% of cases (11 of 41 cases) and reconstructive in 73.17% of them (30 of 41 cases). The most frequent SOT involved was kidney transplantation with 41.46%. The percentage of heart transplants, pancreas transplants, lung transplants and liver transplants were 17.07%, 9.75%, 2.43% and 7.31% respectively. Twenty-two percent of SOT involved were not described. Minor complications were detected in 13 cases (31.7%), while in two opportunities major surgical complications required returning to the operating room (4.88%). No death was reported. The results are summarized in Tab. 1.

Tab. 1. Characteristics of studies comparing breast procedures outcomes for solid organ transplantation.

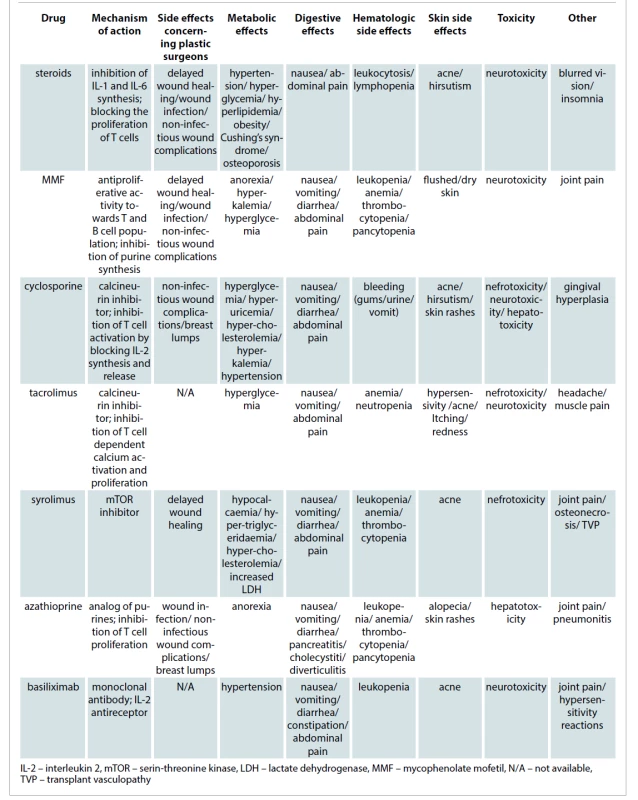

Immunosuppressive drugs

Common adverse effects of immunosuppressants are well documented and include metabolic side effects, toxicities and infectious complications. Those are described in Tab. 2. Current standardization of immunosuppressive protocols helps to predict the susceptibility to infection and impairment of wound healing [6].

Tab. 2. Side effects of drugs in chronic immunosuppression.

The type, dose, and long-term duration of immunosuppressive agents utilized to prevent graft rejection after transplantation have all been shown to affect the risk of cancer development without identification of an individual agent in cancer outcomes since a variety of drugs are needed during any stage for prevention of organ rejection [7]. It is possibly related to chronic inflammation and weakness of cellular immune responses.

Steroids

These drugs are known to inhibit all phases of wound healing, wound contraction, collagen deposition, epithelialization. This effect is due to their interruption of the normal inflammatory response. Glucocorticoids lower the levels of transforming growth factor-B (TGF-B) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) in wounds. Both growth factors are necessary in the inflammatory cascade leading to collagen synthesis. The resulting inhibitory effects affect wound healing, delay of recovered wound tensile strength and increase friability of the skin and superficial blood vessels carrying important surgical implications [8].

Steroids are associated not only with delayed wound healing and increased risk of infection but also with a large number of side effects such as hypertension, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, obesity, effects on bone metabolism, weight gain, eye disorders, Cushing’s syndrome depending on the timing of administration [4,6,8].

The elimination of steroids or doses < 10mg/day in the post-transplant immunosuppression regimen has greatly contributed to improved physical appearance and better wound healing in these patients. If corticosteroids are necessary during the postoperative period, they should be administered three or more days after wound healing to reduce inhibitory effects on wound healing [4].

Some patients still require chronic low-dose steroids. Receiving their usual dose of corticosteroids instead of a stress dose plays a significant role in reducing side effects related to wound breakdown, psychiatric disturbances, and blood sugar control in elective surgery [9]. If any signs of adrenal insufficiency appear as a long-term consequence of corticosteroid therapy, steroid replacement giving low peak doses every 8 h and tapering to baseline over a short period of time, such as 1–3 days is recommended to mimic the physiologic response to stress [9].

The timing of esthetic breast surgery procedures relative to the transplant procedure itself is critical. All elective surgical procedures should be postponed during any interval requiring reintroduction or increased dose of steroids. Papadopoulos et al reported a series of 41 transplant recipients undergoing plastic surgery procedures. In their series, only patients undergoing plastic surgery procedures early after transplantation experienced an increased morbidity [2]. It is advised that mean elapsed time after transplant should be more than 6 months for elective cases to prevent graft rejection trying to avoid acute rejection episodes [9].

An univariate analysis was performed by Sbitany et al to assess the correlation between the various immunosuppressive medications and the frequency of any complication in microvascular free tissue transfer. This analysis illustrates a statistically significant association between prednisone and complications we mentioned before, but no statistically significant associations of other drugs were found [9].

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporine-treated patients more often experience cosmetic side effects such as acne, hirsutism and gingival hyperplasia, whereas gastrointestinal complications and neurotoxic effects are more frequent in tacrolimus-treated patients. Gigantomastia and breast lumps have also been described in a kidney transplant recipient. Rolles and Calne were the first to describe breast lumps after receiving an allograft under cyclosporine A treatment in 1980 [10,11]. Switching from cyclosporine to tacrolimus after an early evaluation of hormones and a breast ultrasound was found to be effective not only to prevent the progression of nodules but also disappearance of lumps avoiding the need for breast surgery [12]. Cyclosporine A has no proven effect in the process of wound healing [13].

Sirolimus

Special attention for plastic surgeons is warranted in the subpopulation of transplant patients who are maintained on sirolimus. This drug, reserved for patients who do not tolerate other immunosuppressive agents, is a well-known inhibitor of fibroblast and cell proliferation. The potential effects of sirolimus on inhibition of wound healing, which are seen in some patients, are due to the drug’s blockage of the response to interleukin-2 [14]. The use of sirolimus might be a relative contraindication to esthetic surgery. Its use has been related to a high rate of wound complications when compared to tacrolimus despite lowering the administered dose [15]. The transplant team should evaluate switching sirolimus to an alternate medication during the perioperative time. Awareness of the altered pathophysiology and special requirements of the immunosuppressed host will prompt the surgeon to modify the treatment plans accordingly to achieve a successful outcome with a minimal incidence of complications.

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)

MMF has a high rate of gastrointestinal complications and leukopenia and is commonly associated with headache and fatigue [16]. As sirolimus, the use of MMF may be a relative contraindication to esthetic surgical procedures. In a retrospective study, MMF was found to cause more wound infection and noninfectious wound complications when compared to azathioprine in kidney recipients [17].

Azathioprine

Azathioprine is a purine analogue prodrug that requires enzyme action to convert into active compounds. As cyclosporine, azathioprine has no proven effect in the process of wound healing [2]. Other side effects related to this drug are leukopenia, gastrointestinal disturbances or elevated liver function tests. The side effects of most common drugs used in immunosuppressive therapy for SOT recipients that the plastic surgeon must know are summarized in Tab. 3.

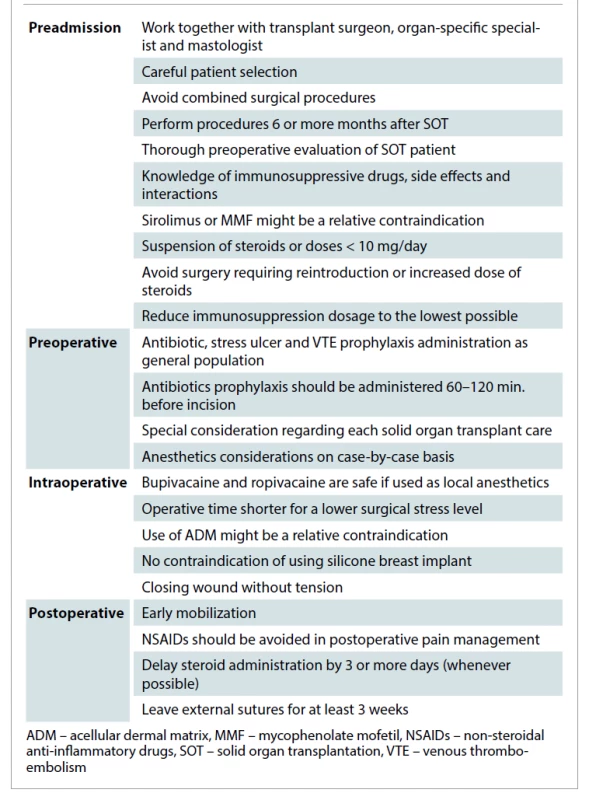

Tab. 3. Proposed management protocol for breast plastic surgery in solid organ transplantation patients.

Management considerations

Anesthesiology

There is no ideal anesthetic for the use in organ transplant recipients. When performing a non-transplant surgery, perioperative anesthetic management in the majority of recipients is like the standard practice for any patient. Despite that, specific considerations should be kept in mind such as the adverse effects of immunosuppressive drugs, its interaction with anesthetic drugs, the potential of organ rejection, blood product administration, as well as the risk and benefits of invasive monitoring in these patients [9,18]. The indications for invasive monitoring will be based on other criteria than the presence of immunosuppression and the condition after organ transplantation. Another issue is the importance of keeping the operative time shorter for a lower surgical stress level [18,19]. Minimal invasiveness and reduced operative time will be essential for these patients.

Special care must be taken into consideration regarding each SOT case, such as avoiding non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs in kidney transplants recipients [18]. We suggest working with an experienced anesthetist who knows pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions among the drugs that the patients take after transplantation. All of our patients are managed by anesthesiologists with long experience in working with this kind of patient. Also, we recommend avoiding long or combined surgical procedures and guiding patients in the direction of separating the sessions or correcting the most desired disorder.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Transplant recipients have an increased susceptibility to infection, but the degree of risk is not uniform throughout the post-transplant period. The risk of infection is higher during the periods of greatest immunosuppression. This is usually during the first 6 months after transplantation and during acute rejection episodes. At present, there is no evidence that prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis protocols provide advantages to preventing infectious complications in some groups of patients, and could predispose to infections [20]. A systematic review compared the use of extended antibiotics versus single dose prophylaxis prior breast surgery with implants and demonstrated a significantly reduced incidence of surgical site infection with extended prophylactic antibiotics (4.6 vs. 11% average infection rate) especially at “higher risk” group of immunosuppressed patients [21]. Since there is no data suggesting a different bacteriology of surgical site infections in these patients, antimicrobial coverage need not to be expanded to include atypical or opportunistic organisms [22]. We recommend the same antibiotic prophylaxis we use with the general population.

Wound healing

The risk of wound-healing complications is higher in transplant patients maintained on steroids chronically. In 2015, Koonce et al demonstrated non-delayed wound healing on patients continuing with immunosuppression drugs (tacrolimus, azathioprine, prednisone, cyclosporine, or MMF) despite none of them were using sirolimus [23]. Surgical wound dehiscence had a negative impact on the physical and social functioning, and bodily pain dimensions of health-related quality of life and on mental health [24]. The impaired wound healing and delay in the attainment of expected wound tensile strength in patients receiving corticosteroids have important surgical implications. Closing the wound without tension is crucial in transplant patients. It is important to use suture materials that have prolonged survival time and to leave sutures, tapes, or clips in the skin closure for at least 3 weeks since the tensile strength of the most absorbable suture materials weakens in the time required to obtain adequate strength in the wound [25]. Since immunosuppressive agents are used in combinations, their individual potential for wound complications is difficult to estimate.

Representative cases

Case 1. A 47-year-old female who underwent a liver transplantation, suffered transplant rejection requiring re-transplantation 30 years ago due to glycogenosis type 1 disease at our hospital. She was interested in breast augmentation and was referred to us by the medical transplant team. Her immunosuppressive therapy included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, meprednisone (from 20 mg/day to 2 mg/day). In addition, she was receiving levothyroxine for hypothyroidism and acenocoumarol due to hepatic thrombosis. The preoperative evaluation of liver function was close to normal. The immunosuppressive drugs were routinely monitored and there was a switch from anticoagulant to enoxaparin sodium injection. She received a preoperative stress dose steroid (hydrocortisone hemisuccinate 50 mg i.v. prior to the procedure), and prophylactic antibiotic (cefazolin). The patient’s perioperative course was uneventful. After a 4-year--follow-up, she had not reported any abnormality or complications (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. A 47-year-old female who underwent a liver transplantation was interested in breast augmentation and was referred to us by the medical transplant team; A) preoperative anterior view; B) postoperative anterior view at one year.

Case 2. A 59-year old female patient, a liver transplant recipient 5 years earlier due to autoimmune hepatitis with the presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA), was referred to us by a breast surgeon after performing a right radical modified mastectomy. No other comorbidity was found. Her immunosuppressive therapy included tacrolimus, MMF, meprednisone (from 20 mg/day to 2 mg/day). She received chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin), radiotherapy treatment and the same immunosuppressive drugs as she had used before. Her liver function tests were close to normal. A two-stage implant-based breast reconstruction was carried out placing first a 450 cm3 breast tissue expander into a subpectoral pocket.

In order to avoid a painful delayed expansion process and only after considering the associated risks, we decided to start expansions as soon as wound healing was completed and the surgical scar looked strong and solid. At week 3, we started injecting 60 cm3 per week, completing the process 6 weeks later. A second stage replacing the expander by the permanent breast implant and a simultaneous contralateral symmetrization with a silicone breast implant was carried out 5 months later. As the patient was previously irradiated, she received a week of antibiotic prophylaxis with trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole [26]. She recovered without any complication (Fig. 3). As we recommend avoiding long surgical procedures, the possibility of long autologous breast reconstruction was not considered.

Fig. 3. A 59-year old female patient, a liver transplant recipient 5 years earlier was referred to us by a breast surgeon after performing right radical modified mastectomy for breast reconstruction; A) preoperative anterior view; B) postoperative view at 3 months after placing an expander; C) late postoperative view at 1 year after replacing an expander by the permanent implant and symmetrization with a breast implant.

Case 3. A 32-year old male patient who underwent a kidney transplant 5 years earlier due to end-stage renal disease and at that time suffering from bilateral gynecomastia was referred to us by his nephrologist. No other comorbidity was found. His immunosuppressive therapy included a triple scheme including cyclosporine, steroids and aziatropina. He underwent a bilateral subcutaneous mastectomy the postoperative recovery of which was uneventful. During follow--up, hypertrophic scarring was detected in both sides requiring scar revision under local anesthesia without any complications (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. A 32-year old male patient who underwent a kidney transplant and was suffering from bilateral gynecomastia was referred to us by his nephrologist; A) a preoperative anterior view; B) postoperative view at 14 months.

In all of these patients, preoperative evaluation was carried in strict collaboration with the transplant surgery departments. All of our patients received the usual antibiotics for those procedures despite being transplant recipients. In all of our patients we used permanent sutures in the different layers of closure. External sutures were avoided, and when required they were removed after one month. They were a true challenge for the entire medical team, where multidisciplinary work enabled a successful end to the all three patients. A proposed protocol of management is presented in Tab. 2.

Discussion

As time goes by, transplant recipient patients have greatly benefited from improved outcomes and a reduced rate of complications due to substantial advances within the last decade [3]. The improved long-term survival rates in transplant recipient patients has led to an increased demand for plastic and reconstructive procedures [2,3].

There is no protocol to define specific precautions when performing general esthetic and reconstructive surgery on transplant organ recipients. These considerations are usually independent of the type of transplant immunosuppressed state. When transplant recipients require non-transplant surgery, immune competence can be altered from the stress of surgery, acute illness, or disruption of the regimen by inexperienced providers. A coordinated teamwork between the plastic surgery and the transplant surgery teams is very important, since a successful and gratifying outcome is possible when all the available resources are brought to bear in the care of these complex patients expecting a comparable degree of success following plastic surgery as the remaining segment of the population [9].

Just case reports, case series or survey-based studies were found in this systematic review, which denotes the need for studies with less bias and greater validity. Indeed, plastic surgeons need to design stronger studies at higher levels of evidence to reach valid conclusions on any topic. Nevertheless, case series and case reports will still be needed for rare conditions and new technical developments among other reasons [27]. Another limitation present in this systematic review is the strong heterogeneity between the studies, which did not make it possible to carry out a quantitative analysis by a meta-analysis and to compare the results.

As expected, reconstructive breast procedures in SOT patients were much more frequent than esthetic ones with the 3/1 ratio (reconstructive/esthetic). In 2016, 1,308 plastic surgeons from all the world participated in a web-based survey related to esthetics surgery in SOT patients. Interestingly, 30% of them performed esthetic procedure on SOT recipients where 92% of respondents reported no complications [19]. This conclusion does not correlate with the percentage of complications reported by the patient population in this study (31.7% complications). This is one piece of evidence that valid data is not available to be statistically analyzed.

Breast augmentation is one of the most popular esthetic surgeries in many countries including ours [28,29]. Therefore, no wonder one of our representative cases was breast augmentation. Although the incidence of breast cancer in SOT recipients is comparable to that in the general population, the prognosis is generally poor [30]. Cyclosporine-treated patients often experience cosmetic side effects such as gynecomastia which was present in our male kidney transplant patient herein reported [10,11].

The use of silicone breast implants for esthetic or reconstructive purposes is controversial. Basic-Jukic et al suggested an association between silicone gel and induction of the immunological response involved in acute allograft rejection shortly after breast implant surgery based on two cases [31]. However further studies with stronger evidence are needed. On the other hand, according to recent statistics from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, over 85% of all breast reconstructions carried out in the US and other countries are implant-based [28,32]. Both female patients, herein presented, underwent their esthetic and reconstructive procedures with silicone breast implants not presenting implant-related complications after 4 years of follow-up.

Reconstructive options after mastectomy may vary depending on the incisions required to perform transplant surgery; for example, lung transplantation that requires section of the latissimus dorsi muscle or kidney transplantation with abdominal incision and its difficulty in using the transverse rectus myocutaneous (TRAM) or deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flaps. The convenience of undergoing long reconstructive microsurgical procedures should be also carefully taken into account. Notwithstanding, Lee et al demonstrated in a multicenter retrospective study that it is safe to perform microsurgical procedures in selected transplant patients [33].

It is supposed that acellular dermal matrices (ADM), very frequently used in implant-based breast reconstruction, should not be recognized as foreign body inducing minimal or no host immune inflammatory response [34]. However, the use of ADM has been reported as a relative contraindication being immunosuppressed [35]. On the other hand, ADM-assisted breast reconstructions are usually linked to a higher likelihood of infection rate if compared to breast reconstructions without the use of ADM [36,37]. Notwithstanding, Koonce et al reported a case using ADM in bilateral breast reconstruction after kidney transplantation without any complications [23]. We suggest not to use it until further studies with stronger levels of evidence are available.

The plastic surgeon has an advantage to manage cases, especially those of esthetic nature, through careful patient selection, investigation of medications, preoperative anesthesiology consultations, and patient information for possible complications. Since esthetic plastic surgery is elective, there are many opportunities to choose the most favorable timing to perform these procedures [38]. It is critical to ensure that the patient is far enough in the postoperative course and is on a stable immunosuppressive schedule to determine the appropriate timing for elective surgery. It is advised that mean elapsed time after transplant should be more than 6 months for elective cases to prevent graft rejection trying to avoid acute rejection episodes [9]. Also, all elective surgeries should be postponed during any interval requiring reintroduction or increased dose of steroids. Unfortunately, some cases such as breast reconstruction following breast cancer are not elective, and in these cases the optimization of medication and care are of paramount importance.

Conclusions

This study represents the first systematic literature review of esthetic and reconstructive breast procedures after SOT. Only case reports, case series or survey-based studies were found in this review. However, data analysis revealed several interesting trends that may aid plastic surgeons in managing transplant recipient patients.

Although esthetic and reconstructive breast surgery could be performed safely in SOT recipients, the dosage of immunosuppression and patient's overall health status with regard to the length and extent of the planned procedure should always be taken into account. Mean elapsed time after transplant should always be more than 6 months for elective cases to prevent graft rejection trying to avoid acute rejection episodes. From the literature data analysis, it is not possible to draw a statistical conclusion that the complication rate of surgery in immunosuppressed post-transplant patients is the same as in normal, not immunosuppressed population. Further and more valid clinical studies are warranted.

Role of authors: R. B. Basso and M. E. Salto conducted the literature search, designed the flowchart and analyzed the collected data. R. B. Basso wrote the manuscript with the input from all authors. H. F. Mayer conceived the study and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All the authors approved the version to be published.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This is a review study with case reports. Our Research Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Patient consent: Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data and photographs.

Horacio F. Mayer, MD, FACS

Perón 4190 (1181), 1st. floor

Buenos Aires

Argentina

horacio.mayer@hospitalitaliano.org.ar

Submitted: 2. 5. 2021

Accepted: 24.7.2021

Zdroje

1. Carmona M. 2017 Global Report. [online]. Available from: www.transplant-observatory.org/download/2017-activity-data-report/.

2. Papadopoulos O., Konofaos P., Chrisostomidis C., et al. Reconstructive surgery for kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2005, 37(10): 4218–4222.

3. Sweis I., Tzvetanov I., Benedetti E. The new face of transplant surgery: a survey on cosmetic surgery in transplant recipients. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009, 33(6): 819–826.

4. Wang AS., Armstrong EJ., Armstrong AW. Corticosteroids and wound healing: clinical considerations in the perioperative period. Am J Surg. 2013, 206(3): 410–417.

5. Liberati A., Altman DG., Tetzlaff J., et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009, 151(4): W65–W94.

6. Whitaker IS., Duggan EM., Alloway RR., et al. Composite tissue allotransplantation: a review of relevant immunological issues for plastic surgeons. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008, 61(5): 481–492.

7. Dantal J., Soulillou JP. Immunosuppressive drugs and the risk of cancer after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2005, 352(13): 1371–1373.

8. Sbitany H., Xu X., Hansen SL., et al. The effects of immunosuppressive medications on outcomes in microvascular free tissue transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014, 133(4): 552–558.

9. Gohh RY., Warren G. The preoperative evaluation of the transplanted patient for non-transplant surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2006, 86(5): 1147–1166.

10. Rolles K., Calne RY. Two cases of benign lumps after treatment with cyclosporin A. Lancet. 1980, 2(8198): 795.

11. Cervelli V., Orlando G., Giudiceandrea F., et al. Gigantomastia and breast lumps in a kidney transplant recipient. Transplantation Proc. 1999, 31(8): 3224–3225.

12. Iaria G., Pisani F., De Luca L., et al. Prospective study of switch from cyclosporine to tacrolimus for fibroadenomas of the breast in kidney transplantation. Transplantation Proc. 2010, 42(4): 1169–1170.

13. Bootun R. Effects of Immunosuppressive therapy on wound healing. Int Wound J. 2013, 10(1): 98–104.

14. Sehgal SN. Rapamune (RAPA, rapamycin, sirolimus): mechanism of action immunosuppressive effect results from blockade of signal transduction and inhibition of cell cycle progression. Clin Biochem. 1998, 31(5): 335–340.

15. Dean PG., Lund WJ., Larson TS., et al. Wound-healing complications after kidney transplantation: a prospective, randomized comparison of sirolimus and tacrolimus. Transplantation. 2004, 77(10): 1555–1561.

16. Petrò L., Ponti A., Roselli E., et al. Perioperative management for patients with a solid organ transplant. Practical Trends in Anesthesia and Intensive Care. 2018, Springer, Cham.

17. Humar A., Ramcharan T., Denny R., et al. Are wound complications after a kidney transplant more common with modern immunosuppression? Transplantation. 2001, 72(12): 1920–1923.

18. Herborn J., Parulkar S. anesthetic considerations in transplant recipients for nontransplant surgery. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017, 35(3): 539–553.

19. Vandegrift MT., Nahai F. Is aesthetics surgery safe in the solid organ transplant patient? An international survey and review. Aesth Surg J. 2016, 36(8): 954–958.

20. Berry PS., Rosenberger LH., Guidry CA., et al. Intraoperative versus extended antibiotic prophylaxis in liver transplant surgery: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Liver Transpl. 2019, 25(7): 1043–1053.

21. Huang N., Liu M., Yu P., et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in prosthesis-based mammoplasty: a systematic review. Int J Surg. 2015, 15 : 31–37. 22. Bliven K., Snow K., Carlson A., et al. Evaluating a change in surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in kidney transplant recipients. Cureus. 2018, 10(10): e3433.

23. Koonce SL., Giles B., McLaughlin SA., et al. Breast reconstruction after solid organ transplant. Ann Plast Surg. 2015, 75(3): 343–347.

24. Corrêa NFM., de Brito MJ., de Carvalho Resende MM., et al. Impact of surgical wound dehiscence on health-related quality of life and mental health. J Wound Care. 2016, 25(10): 561–570.

25. Cohen M., Pollak R., Garcia J., et al. Reconstructive surgery for immunosuppressed organ-transplant recipients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989, 83(2): 291–295.

26. Mirzabeigi MN., Lee M., Smartt JM., et al. Extended trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis for implant reconstruction in the previously irradiated chest wall. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012, 129(1): 37–45.

27. Agha RA., Devesa M., Whitehurst K., et al. Levels of evidence in plastic surgery – bibliometric trends and comparison with five other surgical specialties. Eur J Plast Surg. 2016, 39(5): 365–370.

28. American Society of Plastic Surgeons 2019 statistics. [online]. Available from: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2019/plastic-s urgery-statistics-full-report-2019.pdf.

29. Mayer HF., Loustau HD.. Immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction in the previously augmented patient. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015, 68(9): 1311–1313.

30.Wong G., Au E., Badve SV., et al. Breast Cancer and Transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2017, 17(9): 2243–2253.

31. Basic-Jukic N., Ratkovic M., Radunovic D., et al. Association of silicone breast implants and acute renal allograft rejection. Med Hypotheses. 2019, 123 : 81–82.

32. Mayer HF., de Belaustegui EA., Loustau HD. Current status and trends of breast reconstruction in Argentina. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2018, 71(4): 607–609.

33. Lee AB., Dupin CL., Colen L., et al. Microvascular free tissue transfer in organ transplantation patients: Is it safe? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008, 121(6): 1986–1992.

34. Macadam SA., Lennox PA. Acellular dermal matrices: use in reconstructive and aesthetic breast surgery. Can J Plast Surg. 2012, 20(2): 75–89.

35. Rebowe RE., Allred LJ., Nahabedian MY. The evolution from subcutaneous to prepectoral prosthetic breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018, 6(6): e1797.

36. Ho G., Nguyen TJ., Shahabi A., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of complications associated with acellular dermal matrix-assisted breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2012, 68(4): 346–356.

37. Hallberg H., Lewin R., Søfteland MB., et al. Complications, long-term outcome and quality of life following Surgisis® and muscle-covered implants in immediate breast reconstruction: a case-control study with a 6-year follow-up. Eur J Plast Surg. 2019, 42 : 33–42.

38. Thakurani S., Gupta S. Evolution of aesthetic surgery in India, current practice scenario, and anticipated post-COVID-19 changes: a survey-based analysis. Eur J Plast Surg. 2020, 1–10.

39. Shi Y-D., Qi F-Z., Feng Z-H. Bilateral reduction mammoplasty after heart transplantation. Heart Surg Forum. 2014, 17(4): E224–E226.

40. Zellner E., Lentz R. Complications following plastic surgery in solid organ transplant recipients: a descriptive cohort study. J Aesthet Reconstr Surg. 2016, 2 : 10.

41. Özkan B., Albayati A., Eyüboğlu AA., et al. Aesthetic surgery in transplantation patients: a single center experience. Exp Clin Transplant. 2018, Suppl 1(Suppl 1): 194–197.

42. Pan Y., Grindstaff A., Cassada D., et al. Bilateral reduction mammoplasty in a patient treated with calcium channel blocker and cyclosporine after renal transplant: a case report. Transplantation. 1997, 63(7): 1032–1033.

Štítky

Chirurgia plastická Ortopédia Popáleninová medicína Traumatológia

Článok vyšiel v časopiseActa chirurgiae plasticae

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2021 Číslo 3- Metamizol jako analgetikum první volby: kdy, pro koho, jak a proč?

- Kombinace metamizol/paracetamol v léčbě pooperační bolesti u zákroků v rámci jednodenní chirurgie

- Antidepresivní efekt kombinovaného analgetika tramadolu s paracetamolem

- Metamizol v terapii akutních bolestí hlavy

- Srovnání analgetické účinnosti metamizolu s ibuprofenem po extrakci třetí stoličky

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Editorial

- Fournier’s gangrene secondary to male’s circumcision – a case report and review of the literature

- Reconstructive and esthetic breast surgery after solid organ transplantation – a systematic review, proposal of a novel protocol and case presentations

- Characteristics of fingertip injuries and proposal of a treatment algorithm from a hand surgery referral center in Mexico City

- Platelet-rich plasma improves esthetic postoperative outcomes of maxillofacial surgical procedures

- Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma – an evolution through the decades: citation analysis of the top fifty most cited articles

- Bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma

- Three-dimensional navigation in maxillofacial surgery – the way to minimize surgical stress and improve accuracy in fibula free flap and Eagle’s syndrome surgical procedures

- Is it a second scrotum?

- Professor Radana Königová Prize awards

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma

- Platelet-rich plasma improves esthetic postoperative outcomes of maxillofacial surgical procedures

- Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma – an evolution through the decades: citation analysis of the top fifty most cited articles

- Characteristics of fingertip injuries and proposal of a treatment algorithm from a hand surgery referral center in Mexico City

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy