-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Deceased donor uterus retrieval – The first Czech experience

Odběr dělohy k transplantaci od zemřelého dárce – první zkušenosti v České republice

Úvod:

Transplantace dělohy je nejmladší orgánovou transplantací popsanou v literatuře. Tento výkon představuje jedinou metodu léčby infertility pro ženy s vrozeným nebo získaným chyběním dělohy.Metoda:

Tato experimentální metoda dosud nebyla zavedena do klinické praxe, celkem bylo dosud na světě provedeno pouze 13 transplantací dělohy. Jediná dosavadní klinická studie prokázala, že transplantace dělohy u člověka je nejen proveditelná, ale současně i úspěšná ve smyslu narození zdravého dítěte.Výsledky:

V roce 2015 byla Ministerstvem zdravotnictví ČR povolena studie transplantace dělohy. Její první fázi představuje provedení a detailní popis odběru dělohy od zemřelého dárce.Závěr:

První odběr dělohy od zemřelého dárce jako součást multiorgánového odběru od zemřelé dárkyně byl proveden 13. 1. 2016 a je předmětem sdělení.Klíčová slova:

děloha – transplantace – zemřelý – dárce - odběr

Authors: J. Froněk 1; L. Janousek 1; Roman Chmel 2

Authors place of work: Transplant Surgery Department, Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine (IKEM) Prague, Head of Transplant Surgery Department: doc. J. Froněk, MD, Ph. D, FRCS 1; Department of Gynaecology nad Obstetrics, 2nd Faculty of Medicine, University Hospital Motol, Prague, Head of Department: R. Chmel, MD, Ph. D. 2

Published in the journal: Rozhl. Chir., 2016, roč. 95, č. 8, s. 312-316.

Category: Původní práce

Summary

Introduction:

Uterus transplantation is the youngest solid organ transplantation described in the literature. This procedure is the only treatment method for congenital or acquired Absolute Uterine Factor Infertility.Method:

The method is not recognised as standard clinical care yet, there were only some 13 cases performed worldwide so far. There is only one clinical trial worldwide, which has proven both feasibility and also healthy child delivery.Results:

Czech Republic Ministry of Health permitted the uterus transplant clinical trial in 2015. The first phase of the surgical part includes performance and description of the uterus retrieval from a deceased donor.Conclusions:

The first uterus retrieval from a deceased donor as a part of multi-organ retrieval was performed in the Czech Republic on January 13th, 2016; the case is described in the paper.Key words:

uterus – transplantation – deceased – donor – retrievalIntroduction

Uterus transplantation is the youngest organ transplantation. The first attempt at uterus transplantation (UTx = uterus transplantation) was performed in 1931 in Germany, the recipient was a transsexual woman from Denmark named Lili Elbe, who died 3 months after the transplantation due to graft rejection [1].

The first clinical uterus transplantation from a living donor was performed in Saudi Arabia on April 6th, 2000. The recipient was a 26-year-old woman, who underwent an abdominal hysterectomy 6 years prior to the transplantation for life-threatening peripartal haemorrhage. The donor was a 46-year-old woman, who underwent a planned abdominal hysterectomy for histopathologically confirmed benign multilocular ovarian cysts. The uterine vessels were elongated ex-vivo using grafts from the great saphenous vein, and the uterus was then orthotopically transplanted with vascular anastomoses to the pelvic vessels. Immunosuppression was administered in a triple combination of cyclosporine A, azathioprine and prednisolone; one rejection episode was recorded, which was treated with anti-thymocytic globulin (ATG). Hysterectomy of the graft was performed on the 99th day after transplantation due to thrombosis of the uterine vessels after uterine prolapse because of insufficient support of the uterus in the pelvis during transplantation [2].

The second clinical uterus transplantation, and the first transplantation from a deceased donor, was performed in Turkey on August 9th, 2011. The recipient was a 21-year-old woman with Mayer-Rokitanski-Küster-Hauser syndrome (agenesis of the uterus and vagina), the donor was a 22-year-old woman with confirmed brain death after traumatic brain injury from a motor vehicle accident. The patient underwent the first cryoembryotransfer after prior IVF 18 months after UTx, pregnancy was only confirmed biochemically (elevated serum levels of chorionic gonadotropin hCG). Subsequent fertilization led to ultrasonographic confirmation of intrauterine pregnancy, which was, however, terminated spontaneously by abortion in the 6th week of pregnancy. The Turkish group is continuously systematically studying the issue of UTx [3−9].

Neither of the above-mentioned uterus transplantations resulted in the desired aim, the delivery of a healthy baby.

The first clinical UTx trial was performed in 2012 and 2013 in Sweden, where a total of 9 UTx from previously planned 10 were performed and all consisted of transplantations from living donors. Two of the 9 grafts had to be removed; the first due to early acute thrombosis of the uterine arteries and veins, and the second was removed 4 months after UTx due to an abscess in the uterine cavity, which was untreatable by conservative treatment. Of the 7 women with a transplanted uterus, to date, 5 have delivered a healthy baby and the 6th had a miscarriage in the second trimester of pregnancy. The Swedish group has been actively studying the issue of UTx for many years and is justifiably considered the world leader in UTx [10−21]

In November 2015, a UTx from a living donor was performed in China [22], more information regarding this transplantation and this patient is currently not available.

At the end of February 2016, media released information regarding the first uterus transplantation from a deceased donor in Cleveland, USA; however, the uterus had to be removed from the recipient several days after the transplantation due to vascular thrombosis.

Since 2012, the Transplant Surgery Department IKEM in cooperation with the Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 2. Medical Faculty at Charles University and University Hospital Motol have been preparing a clinical trial of uterus transplantation from living and deceased donors. At the time of approval, this was probably the first trial in the world that included UTx from both living and deceased donors. The presented study was permitted by the Czech Ministry of Health in 2015 and was subsequently launched.

Method

Preparation for UTx in the Czech Republic included cooperation with the transplant department in Göteborg, Sweden. The uterus transplantation study was permitted by the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic on July 7, 2015 and approved by the Ethics Committee. A total of 20 UTx will be included in the study, 10 from living and 10 from deceased donors. The study was officially begun on November 9, 2015, after fulfilling all of the required criteria. A form for uterus procurement from a deceased donor was developed in cooperation with the Transplant Coordination Centre – Accompanying List of the Procured Organ.

In our study, possible uterus donors were all deceased donors with established brain death according to valid criteria set by the Transplantation law, who also fulfilled the following study criteria: female sex, up to 60 years of age, without history of hysterectomy or uterus malignancy. In the first phase of the trial, based on the approved protocol, the plan is to perform “practice” uterus retrievals from deceased donors, their number is set to be two and more. The number of retrievals is not set specifically, because thus far, only minimal experience with uterus retrievals from a deceased donor exist. The first uterus transplantation from a deceased donor as part of our study will take place after performing the “practice” retrievals once the surgical team is absolutely convinced of the quality of the procured organ. This approach was discussed and approved during meetings with the Czech Ministry of Health as well as with the Transplant Coordination Center.

The first uterus procurement from a deceased donor was performed January 13, 2016 in IKEM. The donor was a 41-year-old woman with intracerebral haemorrhage after aneurysm rupture, with two days of artificial lung ventilation, normal laboratory results, minimal circulatory support, one delivery by caesarean section in the past.

Deceased donor uterus retrieval – operation description

Uterus retrieval from a deceased donor was performed in several phases during multi-organ retrieval from a deceased donor with confirmed brain death. The first phase of uterus procurement includes a gynaecological ultrasound, the second phase is a macroscopic assessment of the quality of the uterus, the third phase involves preparation of the uterus and vessels, followed by perfusion, excision and subsequent ex-vivo assessment and documentation of the quality of the graft.

Phase 1 – Transvaginal ultrasound

Transvaginal ultrasonographic examination of a deceased donor prior to uterus procurement for transplantation is performed to rule out pathologies of the uterus, such as myoma, endometrial or cervical polyp, or possibly a different pathology regarding the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries. The procured uterus was not enlarged, no myomas were found, the endometrium reached a total ultrasound height of 6 mm and there were no signs of scar dehiscence after uterotomy performed during the prior caesarean section. The ovaries were also not enlarged, no preovulatory follicle was present (the phase of the ovulatory cycle was, of course, unknown).

Phase 2 - In situ assessment of uterus quality

The deceased donor with brain death was placed onto the operating table in the supine position, as is customary in multi-organ retrieval. Disinfection of the operating field -the abdomen, thorax and both lower limbs - was performed prior to the incision. A thoracolaparotomy was then performed from the jugular notch to the symphysis and the organs of the abdominal and thoracic cavities were examined to rule out malignancy or other pathology. Subsequently, preparation of the pelvic vessels, aorta and inferior vena cava, along with standard preparation of all procured organs of the abdominal and thoracic cavities was performed.

Macroscopic assessment of uterus quality: Colour homogeneity, rigidity, possible surrounding adhesions, signs of trauma, character of the scar after uterotomy, presence of focal lesions or endometriosis, a potentially pathological condition of the fallopian tubes and ovaries were evaluated.

Phase 3 – Preparation of the uterus and vessels

Preparation of the uterus and vessels in steps:

- Liberation of the utero-inguinal ligament at the pelvic wall, transection between ligatures

- Preparation of the ovarian veins bilaterally

- Preparation of the uterus from the urinary bladder while preserving the peritoneum above the urinary bladder with the uterus graft (for fixation to the pelvis in the recipient)

- Preparation along the edge of the uterus caudally up to the uterine vascular bundle

- Preparation of the uterine artery and vein separately up to half of their length between their divergence from the pelvic vessels and the edge of the uterus

- Detailed preparation of the pelvic vessels and distal ureters from their crossing of the iliac vessels to the orifice of the urinary bladder

- Preparation of the internal iliac artery and its branches

- Preparation of the uterine artery

- Preparation of the internal iliac vein and the orifice of the uterine vein

- All vessels of the uterus graft are marked with rubber slings

The uterus is then prepared for the subsequent part of the procurement - cannulation and perfusion

Phase 4 - In situ perfusion by conservation solution

For organ perfusion, it is necessary to prepare and cannulate both external pelvic arteries. The external iliac artery is prepared bilaterally and then distally ligated, two perfusion cannulas joined by a Y-connector are introduced into the arteriotomy at both sides.

Venous drainage is ensured by cannulating the inferior vena cava similarly to other multi-organ procurements. In addition, the external pelvic vein is ligated and after perfusion is begun, an opening is made into the external pelvic vein above the ligature to ensure blood drainage from the uterus. Then the donor is prepared for the final phase of the procurement - perfusion and subsequent organ excision. After perfusion is performed, all organs selected for procurement for waiting recipients are successively excised, and the uterus, being a non-lifesaving organ, is removed last.

Phase 5 - In situ graft excision

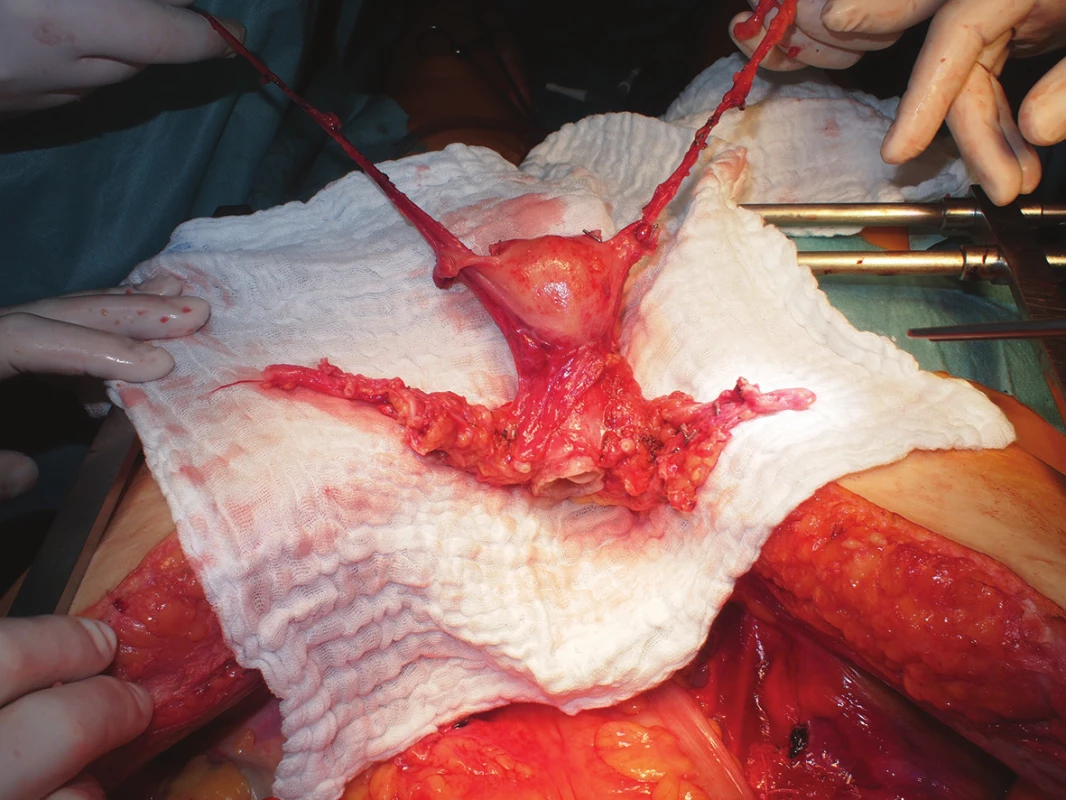

After macroscopic assessment of the quality of perfusion of the uterus (change in colour, homogenous character), all vascular structures are gradually transacted, both ovarian veins are left approximately 10 cm long, the uterine arteries and veins are collected along with a stump of the internal iliac artery and vein, respectively. The sacro-uterine ligaments are then cut, the vagina is sharply transsected circularly by scalpel about 1 cm below the palpable cervix (Fig. 1) and the removed uterus is placed into a container with preservation solution and melted ice.

Fig. 1. Uterus graft from a deceased donor after in-situ cold perfusion following graft excision

Phase 6 - Ex-vivo assessment and documentation of graft quality

The following are performed ex-vivo:

- Evaluation of perfusion quality

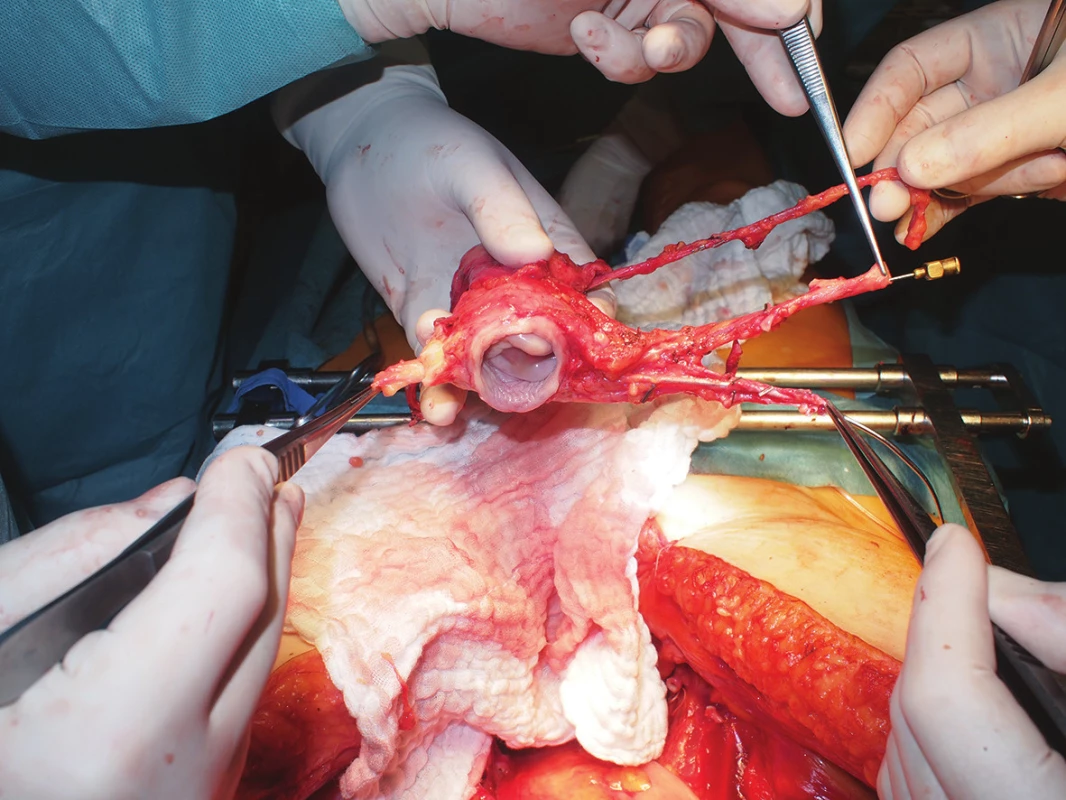

- Evaluation of the quality of all vessels, documentation, cannulations, measurements (Fig. 2)

- Ex-vivo perfusion with preservation solution and evaluation of the effluate, whether it still contains any blood

- Hysteroscopy – to rule out endometrial pathology

- uterus graft placement in preservation solution to assess the preservation injury in given intervals (will be published separately).

Fig. 2. Deceased donor uterus graft quality assessment, including related vasculature

RESULTS

Historically the first Czech uterus retrieval from a deceased donor was successfully performed in a donor with brain death, a young woman with medical history of one delivery by caesarean section. Due to this previous operation of the uterus with subsequent scarring, preparation in the vesicouterine excavation and right parametria was difficult, however, the quality of the dissected vessels was discovered to be very good. Because the donor was considered to be an “ideal” deceased donor, the uterus procurement was part of a multi-organ retrieval. The actual uterus retrieval, after standard opening of the abdominal and thoracic cavity, consisted of 40 minutes of initial preparation, the final excision of the uterus and vessels after perfusion at the end of the multi-organ procurement took an additional 10 minutes. The uterus retrieval did not negatively affect neither retrieval quality nor transplant outcomes.

Discussion

The issue of uterus transplantation is the subject of many theoretical academic publications, especially focussing on the future of UTx, individual projects, assumptions and hopes invested in this new experimental method of treating female infertility [13−17, 23−29]. A number of specialised publications address the ethical requirements and consequences of uterus transplantation [30−39]. Only a few works discuss the criteria and necessary examinations or protocol descriptions involved in the preparation of uterus transplantation [18,19,40−43]. Due to the yet very limited experience, only a minimal number of publications report on pregnancy and delivery after UTx [20,44−47]. Uterus living donation, which represents one half of our project, is also rarely described, as well as the risks and pitfalls associated with this method [21,48]. A description of the technique of retrieving the uterus from a deceased donor or specialized literature regarding this topic is also currently very limited [49−52]. We consider the presentation of our method and technique of retrieval of the uterus and all major vessels as an important beginning of our UTx study and also as a significant contribution to the discussion regarding preparation, standardization, and successful realization of the program of experimental uterus transplantation, which is currently being created and prepared at only several workplaces worldwide.

Our technique of practice procurement includes not only typical preparation for uterus transplantation from a deceased donor (concentrating on vessel preparation and not on ureters), but by partially liberating and attempting to preserve intact ureters, we are preparing for uterus retrieval from a living donor, which is technically more difficult and with regard to both ureters and uterine veins is definitely more risky. In the planned experimental clinical study of uterus transplantation from a deceased donor, testing for the presence of oncogenic HPV (human papillomavirus) will of course be performed in the cervix of the donor, which lacked significance in the case of practice uterus retrieval in preparation for future uterus transplantation. In the case of described uterus retrieval from a deceased donor, it is also not necessary to consider possible injury to pelvic nervous structures - especially the hypogastric nerve and the inferior hypogastric plexus. This injury, however, is not likely even in the case of a living donor. Uterus retrieval is technically different from a radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy, only the uterine vessels are dissected, all other surrounding tissues and structures are left in situ if retrieval is from a living donor.

CONCLUSION

The founding meeting of the International Uterus Transplantation Society took place in January 2016 in Göteborg, Sweden. Our team presented the concept of the uterus transplant trial (including “training” uterus procurement) in the Czech Republic, which was unequivocally met with positive acceptance.

Our first presented case of uterus retrieval for transplantation from a multi-organ deceased donor established that after adequate theoretical and practical preparation, this procedure is technically feasible, not only in terms of removal of the uterus and utero-inguinal and sacro-uterine ligaments and parietal peritoneum necessary for fixation of the uterus into the pelvis of the recipient, but also with regards to preparation and liberation of the ovarian veins, uterine arteries and veins and finally the necessary portions of the iliac arteries and veins from the surrounding tissues, including the ureters.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have not conflict of interest in connection with the emergence of and that the article was not published in any other journal.

Mr. Jiri Fronek, MD PhD FRCS

Associate professor of surgery

Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine

Videnska 1958/9

140 21 Prague

e-mail: jiri.fronek@ikem.cz

Zdroje

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uterus_transplantation

2. Fageeh W, Raffa H, Jabbad H, et al. Transplantation of the human uterus. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2002;76 : 245−51.

3. Ozkan O, Akar ME, Ozkan O, et al. Preliminary results of the first human uterus transplantation from a multiorgan donor. Fertil Steril 2013;99 : 470−6.

4. Erman Akar M, Ozkan O, Aydinuraz B, et al. Clinical pregnancy after uterus transplantation. Fertil Steril 2013;100 : 1358−63.

5. Ozkan O, Akar ME, Erdogan O, et al. Uterus transplantation from a deceased donor. Fertil Steril 2013;100:e41.

6. Akar ME, Erdogan O. Uterus transplantation. Fertil Steril 2013;100:e34.

7. Akar ME. Uterus transplantation research at the cutting edge? Fertil Steril 2013;100:e39.

8. Öztürk H. How real is the uterine transplantation? Ann Transplant 2014;19 : 82−3.

9. Akar ME. Might uterus transplantation be an option for uterine factor infertility? J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc 2015;16 : 45−8.

10. Brännström M, Johannesson L, Dahm-Kähler P, et al. First clinical uterus transplantation trial: a six-month report. Fertil Steril 2014;101 : 1228−36.

11. Johannesson L, Kvarnström N, Mölne J, et al. Uterus transplantation trial: 1-year outcome. Fertil Steril 2015;103 : 199−204.

12. Brännström M. The Swedish uterus transplantation project: the story behind the Swedish uterus transplantation project. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015;94 : 675−9.

13. Brännström M, Wranning CA, Racho El-Akouri R. Transplantation of the uterus. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2003;202 : 177−84.

14. Brännström M. Uterine transplantation: a future possibility to treat women with uterus factor infertility? Minerva Med 2007;98 : 211−6.

15. Johannesson L, Dahm-Kähler P, Eklind S, et al. The future of human uterus transplantation. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2014;10 : 455−67.

16. Johannesson L, Järvholm S. Uterus transplantation: current progress and future prospects. Int J Womens Health 2016;8 : 43−51.

17. Brännström M. Uterus transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2015;20 : 621–8.

18. Järvholm S, Johannesson L, Clarke A, et al. Uterus transplantation trial: Psychological evaluation of recipients and partners during the post-transplantation year. Fertil Steril 2015;104 : 1010−5.

19. Järvholm S, Johannesson L, Brännström M. Psychological aspects in pre-transplantation assessments of patients prior to entering the first uterus transplantation trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015;94 : 1035−8.

20. Brännström M, Johannesson L, Bokström H, et al. Livebirth after uterus transplantation. Lancet 2015;385 : 607−16.

21. Olausson M, Johannesson L, Brattgård D, et al. Ethics of uterus transplantation with live donors. Fertil Steril 2014;102 : 40−3.

22. Personal message, Göteborg, leden 2016.

23. Grynberg M, Ayoubi JM, Bulletti C, et al. Uterine transplantation: a promising surrogate to surrogacy? Ann N Y Acad Sci 2011;1221 : 47−53.

24. Kisu I, Banno K, Mihara M, et al. Current status of surrogacy in Japan and uterine transplantation research. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;158 : 135−40.

25. Farrell RM, Falcone T. Uterine transplantation. Fertil Steril 2014;101 : 1244−5.

26. Kisu I, Banno K, Mihara M, et al. Uterine transplantation: towards clinical application. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2013;76 : 74.

27. Saso S, Ghaem-Maghami S, Louis LS, et al. Uterine transplantation: what else needs to be done before it can become a reality? J Obstet Gynaecol 2013;33 : 232−8.

28. Dahm-Kähler P, Diaz-Garcia C, Brännström M. Human uterus transplantation in focus. Br Med Bull 2016;117 : 69−78.

29. Nau JY. The first uterine transplants are about to be authorized in France. Rev Med Suisse 2015;11 : 2198−9.

30. Nair A, Stega J, Smith JR, et al. Uterus transplant: evidence and ethics. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1127 : 83−91.

31. Arora KS, Blake V. Uterus transplantation: the ethics of moving the womb. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125 : 971−4.

32. Allahbadia GN. Human uterus transplantation: have we opened a Pandora’s box? J Obstet Gynaecol India 2015;65 : 1−4.

33. Gauthier T, Garnault D, Therme JF, et al. Uterine transplantation: is there a real demand? Gynecol Obstet Fertil 2015;43 : 133−8.

34. Benagiano G, Landeweerd L, Brosens I. Medical and ethical considerations in uterus transplantation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2013;123 : 173−7.

35. Lefkowitz A, Edwards M, Balayla J. Ethical considerations in the era of the uterine transplant: an update of the Montreal Criteria for the Ethical Feasibility of Uterine Transplantation. Fertil Steril 2013;100 : 924−6.

36. Arora KS, Blake V. Uterus transplantation: ethical and regulatory challenges. J Med Ethics 2014;40 : 396−400.

37. Dickens BM. Legal and ethical issues of uterus transplantation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016 Jan 15. pii: S0020-729200005−9.

38. Bayefsky MJ, Berkman BE. The Ethics of Allocating Uterine Transplants. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 2016;11 : 1−16.

39. Wilkinson S, Williams NJ. Should uterus transplants be publicly funded? J Med Ethics 2015 Dec 15. pii: medethics-2015-102999.

40. Lefkowitz A, Edwards M, Balayla J. The Montreal Criteria for the Ethical Feasibility of Uterine Transplantation. Transpl Int 2012;25 : 439−47.

41. Erman Akar M, Ozekinci M, Alper O, et al. Assessment of women who applied for the uterine transplant project as potential candidates for uterus transplantation. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015;41 : 12−6.

42. Saso S, Clarke A, Bracewell-Milnes T, et al. Survey of perceptions of health care professionals in the United Kingdom toward uterine transplant. Prog Transplant 2015;25 : 56−63.

43. Wennberg AL, Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Milsom I, et al. Attitudes towards new assisted reproductive technologies in Sweden: a survey in women 30-39 years of age. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016;95 : 38-44.

44. Erman Akar M, Ozkan O, Aydinuraz B, et al. Clinical pregnancy after uterus transplantation. Fertil Steril 2013;100 : 1358−63.

45. Donnez J. Live birth after uterine transplantation remains challenging. Fertil Steril 2013;100 : 1232−3.

46. Balayla J, Dahdouh EM, Lefkowitz A. Montreal Criteria for the Ethical Feasibility of Uterine Transplantation Research Group. Livebirth after uterus transplantation. Lancet 2015;385 : 2351−2.

47. Tzakis AG. The first live birth subsequent to uterus transplantation. Transplantation 2015;99 : 8−9.

48. Kisu I, Mihara M, Banno K, et al. Risks for donors in uterus transplantation. Reprod Sci 2013;20 : 1406−15.

49. Ozkan O, Akar ME, Erdogan O, et al. Uterus transplantation from a deceased donor. Fertil Steril 2013;100:e41.

50. Ozkan O, Akar ME, Ozkan O, et al. Preliminary results of the human uterus transplantation from multiorgan donor. Fertil Steril 2013;99 : 470−6.

51. Akar ME, Ozkan O, Ozekinci M, et al. Uterus retrieval in cadaver: technical aspects. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2014;41 : 293−5.

52. Gauthier T, Piver P, Pichon N, et al. Uterus retrieval process from brain dead donors. Fertil Steril 2014;102 : 476−82.

Štítky

Chirurgia všeobecná Ortopédia Urgentná medicína

Článok vyšiel v časopiseRozhledy v chirurgii

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2016 Číslo 8- Metamizol jako analgetikum první volby: kdy, pro koho, jak a proč?

- Kombinace metamizol/paracetamol v léčbě pooperační bolesti u zákroků v rámci jednodenní chirurgie

- Antidepresivní efekt kombinovaného analgetika tramadolu s paracetamolem

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Hodnocení diagnosticko - terapeutického postupu chirurga

- Surgical approaches to pineal region – review article

- Deceased donor uterus retrieval – The first Czech experience

- Treatment of acute appendicitis: Retrospective analysis

- Supravesical hernia as a rare cause of inguinal herniation and its laparoscopic treatment with TAPP approach

- Free-floating thrombus in the internal carotid artery treated by anticoagulation and delayed carotid endarterectomy

- The role of rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) in the perioperative period in a warfarinized patient (case report)

- Perforation of the right ventricle of the heart as a complication of CT guided percutaneous drainage of a subphrenic abscess – a case report

- Výsledky elektronických voleb do orgánů České chirurgické společnosti ČLS JEP

- Životné jubileum profesora Júliusa Mazuchy

- XXVI. Petřivalského − Rapantovy dny

- Rozhledy v chirurgii

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Surgical approaches to pineal region – review article

- Treatment of acute appendicitis: Retrospective analysis

- Free-floating thrombus in the internal carotid artery treated by anticoagulation and delayed carotid endarterectomy

- Supravesical hernia as a rare cause of inguinal herniation and its laparoscopic treatment with TAPP approach

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy