Diagnostic Challenges of Ocular Rosacea

Authors:

Simona Motešická

Authors‘ workplace:

Department of Ophthalmology, Pardubice Regional Hospital, Czech Republic

Published in:

Čes. a slov. Oftal., 80, 2024, No. 2, p. 76-85

Category:

Review Article

doi:

https://doi.org/10.31348/2024/3

Overview

Objective: This study aims to address the issues surrounding the diagnosis of ocular rosacea and to evaluate the development of the patients’ condition after treatment, as well as to distinguish between healthy and diseased patients using a glycomic analysis of tears.

Methodology: A prospective study was conducted to assess a total of 68 eyes in 34 patients over a six-week period. These patients were diagnosed with ocular rosacea based on subjective symptoms and clinical examination. The study monitored the development of objective and subjective values. The difference between patients with the pathology and healthy controls was established by means of analysis of glycans in tears.

Results: Skin lesions were diagnosed in 94% of patients with ocular rosacea, with the most commonly observed phenotype being erythematotelangiectatic (68.8%). The mean duration of symptoms was 29.3 months (range 0.5–126 months) with a median of 12 months. Throughout the study, an improvement in all monitored parameters was observed, including Meibomian gland dysfunction, bulbar conjunctival hyperemia, telangiectasia of the eyelid margin, anterior blepharitis, uneven and reddened eyelid margins, and corneal neovascularization. The study also observed improvements in subjective manifestations of the disease, such as foreign body sensation, burning, dryness, lachrymation, itching eyes, photophobia, and morning discomfort. The analysis of glycans in tears partially separated tear samples based on their origin, which allowed for the differentiation of patients with rosacea from healthy controls. In the first sample, the pathology was determined in a total of 63 eyes (98.4%) of 32 patients, with further samples showing a change in the glycomic profile of patients’ tears during treatment.

Conclusion: The study demonstrated objective and subjective improvements in all the patients. Tear sampling and analysis could provide a means of timely diagnosis of ocular rosacea.

Keywords:

acne rosacea – ocular rosacea – dry eye syndrome – blepharitis – Meibomian gland dysfunction – rosacea diagnosis – glycomic analysis of tears

INTRODUCTION

Rosacea is a chronic, inflammatory skin condition which most frequently affects adult individuals in middle age with a fair skin phototype [1,2]. Ocular affliction is present in 58–75% of patients with the skin form of rosacea, and is bilateral in the majority of cases [1,3,4]. In 15–20% of cases the ocular symptoms precede the skin symptoms [1,3]. Despite the fact that the ocular symptoms are usually mild, the cornea is affected in as many as 41% of cases [1].

The worldwide prevalence of rosacea is estimated at approximately 5.46% of the adult population (range 0.09%–24.1%), with the greatest incidence in the third to the fifth decade of life [1,3]. The prevalence of the ocular form of rosacea is estimated at approximately 1–8%, but the actual prevalence is probably underestimated [5].

A certain influence in the origin of the pathology may be exercised also by genetic predisposition, which is responsible for up to 50% of mechanisms of the pathogenesis of rosacea [3]. The triggering factors which may induce or exacerbate the course of the pathology include e.g. UV radiation, exposure to sunlight, increased physical activity, emotional stress, extreme temperatures, hot beverages, spicy food etc. [6–8].

Pro-inflammatory markers such as interleukin-1a and b, gelatinase B (metalloproteinase‑9) and collagenase-2 (MMP-8) appear in increased concentrations in the tears of patients with ocular rosacea [9]. One of the options for distinguishing patients with rosacea from healthy individuals is glycomic analysis. Higher levels of sulphated O-linked oligosaccharides were measured in patients with rosacea with the aid of high-resolution mass spectrometry, in contrast with a high level of fucosylated N-linked oligosaccharides in the control group [10]. Rosacea and ocular form of rosacea so far remain a clinical diagnosis [1]. In 2017 the classification criteria for rosacea were updated according to phenotypes to diagnostic, primary and secondary (Table 1) [6]. For determination of a diagnosis of rosacea we require the presence of one diagnostic and/or two primary phenotypes [6]. Secondary criteria can only support the diagnosis [11].

Patients with ocular rosacea suffer from a feeling of a foreign body (FB) in the eye, pain, burning, stinging, lachrymation, itching or reddening of the eyes and photophobia [4]. In 2019 the ROSCO panel issued adjusted recommendations, in which it described ten typical signs of ocular rosacea, see Table 2 [11].

Specific criteria for the diagnosis of the ocular form of rosacea in the absence of skin symptoms have not been compiled to date [11]. In patients with ocular symptomatology, examinations are recommended in the following order, see Table 3 [11].

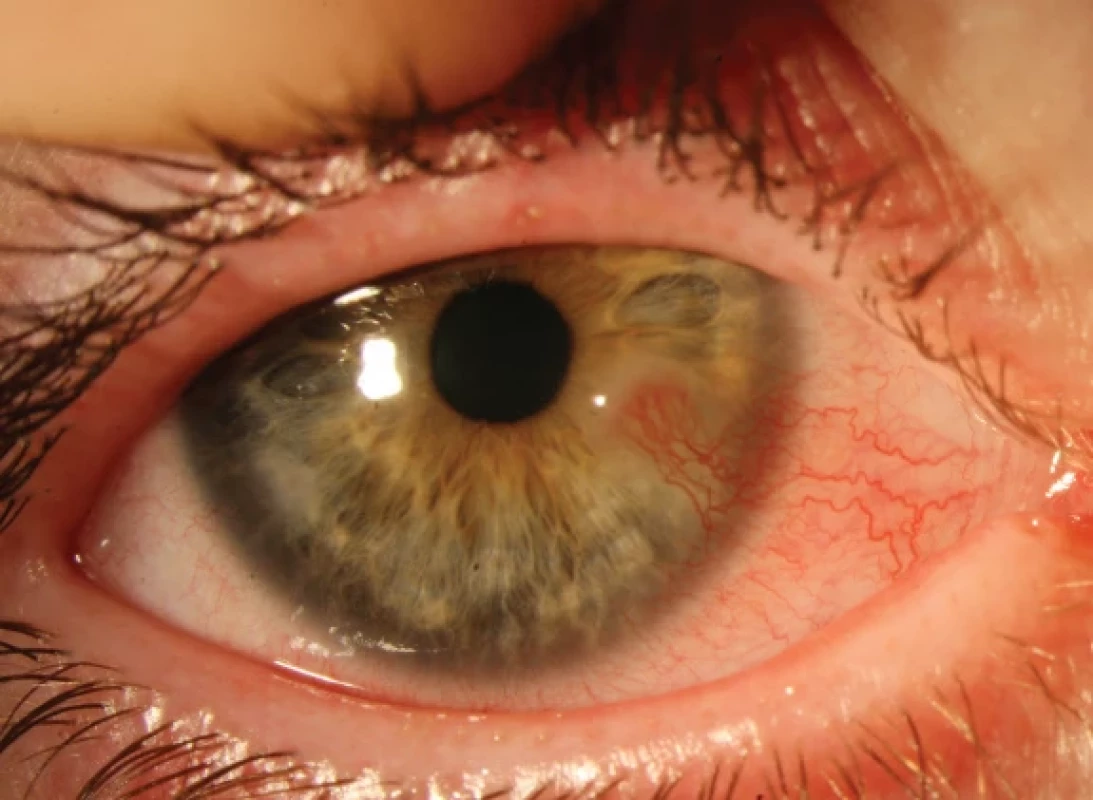

On the bulbar conjunctiva we find hyperemia especially within the scope of the ocular aperture, while on the tarsal conjunctiva, especially on the lower, we observe a papillofollicular reaction [3,4]. We find scarring of the conjunctivae in less than 10% of cases of ocular rosacea, developing as a consequence of chronic inflammation, and in severe cases this may lead to shallowing of the fornices [4,8]. Changes on the cornea may cause sight-threatening complications. The most common findings include punctate epitheliopathy, peripheral infiltrates of the cornea and vascularization, in severe cases with the formation of ulcers up to corneal perforation [4,8]. Chronic inflammation may lead to the formation of Salzmann’s nodular corneal degeneration (Fig. 1) and thinning of the cornea in the lower pole [4,12].

Of pathologies on the eyelids we observe telangiectasia and erythema of the eyelid margin (Fig. 1), which is present in 50–94% of patients, and anterior blepharitis in up to 50% of patients [4]. Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) is present in 92% of patients [4]. On the basis of a clinical examination we may subsequently determine the severity of the ocular form of rosacea, see Table 4.

Treatment should be commenced as early as possible in order to prevent the progression of the pathology and to reduce the risk of development of irreversible ocular changes [12]. The basis for suppression of the symptoms of rosacea is to identify and eliminate the triggering factor of the disease [7]. Conservative therapy consists in hygiene of the eyelids [7]. Lubricants help alleviate dryness of the eyes and reduce the concentration of inflammatory mediators [9]. Topical corticosteroids should be used in the short term in order to manage exacerbations, with progressive discontinuation, while an alternative is topical cyclosporine. In the Czech Republic an available preparation is Ikervis (0.1% cyclosporine) in a dose of 1x per day [9]. In severe cases of the skin and ocular form of rosacea it is possible to support local therapy with the administration of systemic treatment. Doxycycline with delayed release in a dose of 40 mg 1x per day is the only oral FDA-approved treatment of inflammatory lesions upon a background of rosacea. Treatment is conducted long-term, usually for 8–16 weeks [10]. Other antibiotics suitable for the treatment of rosacea and ocular rosacea are clarithromycin, erythromycin, azithromycin and ampicillin [10].

Children constitute a separate group of patients. With regard to ocular manifestations we may find similar symptoms as in adult individuals, but skin symptoms have not yet been manifested, which makes diagnosis more difficult. It is important to pay attention the family medical history of skin form of rosacea and previous episodes of occurrence of chalazions [12]. An example of the finding is presented in Fig. 2.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

The cohort comprised a total of 68 eyes of 34 adult patients, in whom ocular form of rosacea had been diagnosed on the basis of subjective complaints and a clinical examination. All the patients were referred for an examination by a dermatologist for confirmation and treatment of the skin form of rosacea. The subtype of rosacea was indicated as ETR (erythmatotelangiectatic), PPR (papulopustular), or PR (phymatous).

A tear sample was taken from both eyes of all patients in the cohort. The tear sampling took place under sterile conditions, without touching the eyelashes or eyeball, with the use of a glass capillary with a volume of 10 μl. Each sample was then immediately placed in a freezer box at a temperature of -20 °C and sent to the Faculty of Pharmacy at Charles University in Hradec Králové for analysis. A sterile Schirmer filter paper was used as a stimulation aid in order to trigger lachrymation, suspended inside the edge of the lower eyelid by the inner corner of the eye for a period of 30 seconds. With the aid of alkaline hydrolysis, glycans in these tears were released from their bond to proteins, and were subsequently analyzed using the technique of high-performance liquid chromatography with high-resolution mass detection. As a control group, tears were sampled from adult volunteers who did not manifest any symptoms of rosacea. With reference to the time options of the study, samples were taken on the first day, after 6 weeks and after 18 weeks.

The scope of ocular affliction was determined, in which we focused on the presence of telangiectasia on the eyelid margins, hyperemia of the bulbar conjunctiva, MGD and the presence of corneal neovascularization – used classification scale according to Prabhasawat et al. [14].

MGD was examined by means of expression of the glands through pressure on the upper and lower eyelid using a cotton wool swab stick. These four parameters were indicated by a scale of 0–4, see Table 5. In addition, the presence of anterior blepharitis, unevenness, thickening and reddening of the eyelids was evaluated.

Tear breakup time (TBUT) was measured with the aid of 1% fluorescein eye drops, a time longer than 10 seconds was determined as normal, while a time shorter than 10 seconds was considered pathological. Each eye was measured three times and an average was taken of these times. Epitheliopathy was then evaluated with the aid of a standardized Oxford scale.

A lachrymation test was performed with the aid of a Schirmer’s test without the application of a local anesthetic, in which a filter paper of the size of 5x35 mm was inserted behind the temporal edge of the lower eyelid for a period of 5 minutes. A value higher than 15 mm was considered normal, less than 10 mm as impaired function, under 5 mm severe disorder of tear secretion. The average length of complaints before the commencement of treatment was determined on the basis of the patients’ medical history. Subjective complaints of the patients were included among further evaluated parameters. These were presence of burning, presence of FB or dryness, lachrymation, photophobia, itching of eyes, morning discomfort and formation of chalazions.

Treatment was configured individually for each patient according to the severity of the complaints. Follow-up examinations were set in the second, sixth and eighteenth week. Patients with allergic manifestations or concurrent treatment of herpes simplex or herpes zoster were excluded from the study. None of the patients had undergone refractive surgery, patients following cataract surgery were allowed to remain, numbering 8 patients (23.5%) in our cohort. The average time between the operation and the first examination was 3 years and 1 month, with 2 patients (5.9%) stating that their complaints had started immediately after cataract surgery.

Table 1. Classification from 2017 [3]

|

Diagnostic criteria (phenotypes) |

Main criteria (phenotypes) |

Secondary criteria (phenotypes) |

|

Persistent centrofacial redness, which can worsen temporarily |

Papules and pustules |

Itching, burning |

|

Flushing (transient erythema) |

Edema |

|

|

Phymatous changes |

Teleangiectasia |

Dryness |

|

Ocular manifestations (burning and itching of the eyes as signs of conjunctival hyperemia, conjunctivitis, hordeolum, chalazion) |

Table 2. Modified recommendations of the ROSCO Panel [11]

|

Ten typical signs of ocular rosacea Teleangiectasia of the eyelid margins: typically red edges of the eyelids, especially the lower eyelids |

Table 3. Procedure for the diagnosis of ocular rosacea [11]

|

Procedure for the diagnosis of ocular rosacea Skin and eye history |

Table 4. Severity of ocular abnormalities in ocular rosacea (according to Tan et al., [13], taken from [10])

|

Severity |

Features |

|

Mild |

Mild blepharitis with teleangiectasia at the lid margins |

|

Mild to moderate |

Blepharoconjuctivitis |

|

Moderate to severe |

Blepharokeratoconjuctivitis |

Table 5. Scoring system of ocular involvement [15,16]

|

Sign/Score |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

Eyelid teleangiectasia |

None |

Mild |

Moderate |

Severe |

Extremely severe |

|

Conjunctival hyperemia |

None |

Mild |

Moderate |

Severe |

Extremely severe |

|

MGD |

Clear |

Cloudy |

Granular |

Pasty |

Not expressible |

|

Corneal neovascularization |

None |

Up to 2 mm from limbus |

Over 2 mm from limbus |

Extending to corneal center |

In the corneal cen - ter with fibrosis |

Table 6. CFS over time (the table indicates the number of eyes)

CFS – corneal fluorescein staining

|

CFS (Oxford scale) |

First day |

Two weeks |

Six weeks |

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

4 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

|

3 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

|

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

|

1 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

|

0 |

57 |

56 |

61 |

RESULTS

A total of 68 eyes in 34 patients diagnosed with ocular rosacea were examined, comprising 21 men (61.8%) and 13 women (38.2%). The average age at the time of diagnosis was 57.6 years (range 28–82 years), the average observation period was 6 weeks. In 15 patients the observation period reached 18 weeks, and therefore this control period was used only in tear analysis. The average length of complaints before determination of the diagnosis was 29.3 months (range 0.5–126), median 12 months.

At the time of diagnosis MGD was present in all patients (100%), anterior blepharitis in 21 patients, total 42 eyes (61.8%), punctate epitheliopathy in 7 patients, total 11 eyes (16.2%), neovascularization in 7 patients, total 11 eyes (16.2%), Salzmann’s nodular degeneration was present in 2 patients, total 3 eyes (4.4%), unevenness or reddening of the edges of the eyelids was observed in 20 patients, total 40 eyes (58.8%). At least 1 chalazion had appeared during the medical history of 7 patients (20.6%).

Affliction of the skin was diagnosed in almost all patients (94.1%), in one patient (2.9%) no skin changes were manifested and in one female patient (2.9%) scleroderma was diagnosed. The representation of the skin phenotypes of rosacea is illustrated in Graph 1. The most commonly occurring phenotype is the ETR form (68.8%).

In our cohort a finding of telangiectasia of the eyelid margin was present in 33 patients, total 66 eyes (97.1%). The presence and degree of severity of telangiectasia depending on the skin phenotype of rosacea is illustrated in Graph 2, from which it ensures that the form of skin affliction does not correlate with the affliction of the eyelids or vice versa.

A certain degree of hyperemia of the bulbar conjunctiva was present in all patients (100%), over time an improvement of the finding was achieved; the difference is evident in Graph 3. With reference to the chronic character of the condition, certain changes, such as dilation of blood vessels, are irreversible. As a result, after treatment the largest representation of hyperemia of the bulbar conjunctiva was of a mild (61.8%) and medium (23.5%) degree.

The severity of MG is illustrated by Graph 4. An improvement of the content of the glands and their expressibility was achieved after 6 weeks in 23 patients, total 46 eyes (67.6%).

Neovascularization was evident in 7 patients, total 11 eyes (16.2%), in the second week in 6 patients, total 10 eyes (14.7%) and in the sixth week in 6 patients, total 9 eyes (13.2%).

Anterior blepharitis was described in 21 patients, total 42 eyes (61.8%), in the second week in 15 patients, total 29 eyes (42.6%) and in the sixth week in 9 patients, total 14 eyes (20.6%).

In an evaluation of epitheliopathy with the aid of corneal fluorescein staining (CFS), an improvement was observed over time. A summary of the data is presented in table 6. On the first day (CFS score 1–5) it was present in 7 patients, total 11 eyes (16.2%), in the second week (CFS score 1–3) in 6 patients, total 12 eyes (17.6%) and in the sixth week (CFS score 1–3) in 4 patients, total 7 eyes (10.3%).

Throughout the entire observation period, the mean TBUT value was 6.11 (±0.082) and the value of the Schirmer’s lachrymation test was 14.0 (±0.078). No statistically significant differences over time were recorded in either values (T-test, value p > 0.05).

In an evaluation of subjective patient complaints, on the first day the most widely represented was a feeling of a FB in 25 patients (73.5%), followed by burning of the eyes in 24 patients (70.1%) and dryness of the eyes in 23 patients (67.6%). Lachrymation of the eyes was present in 14 patients (41.2%), itching of the eyes was recorded in 10 patients (29.4%), photophobia and morning discomfort was stated by 7 patients (20.1%).

Graph 5 records the reporting of subjective complaints over time, the individual curves illustrate a decrease already in the second week, after 6 weeks a feeling of a FB was recorded in 5 patients (14.7%), burning of the eyes in 6 patients (17.6%), dryness of the eyes in 5 patients (14.7%), lachrymation and itching of the eyes in 3 patients (8.8%), photophobia and morning discomfort persisted in 2 patients (5.9%).

Sampling of tears in a sufficient quantity of processing was performed in 32 patients, total 64 eyes (94.1%), a total of 15 volunteers, total 30 eyes (100%) were included in the control group. A broad spectrum of glycans was found in the tear samples, with a total of 83 identified. The data was further processed with the aid of a multivariate analysis. A partial division of the samples on the basis of their origin was conducted with the aid of the OPLS-DA (orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis) method, i.e., it was possible to differentiate patients with rosacea from healthy control subjects, as illustrated in Graph 6. It is possible to observe a change of the glycomic profile of tears of patients during the course of treatment. Despite the fact that in the first sample 32 patients, total 63 eyes (98.4%) were classified in the group with ocular rosacea, in a number of them (4 patients, total 8 eyes, 12.5%) the second and third sample placed them in the group of healthy subjects. By contrast, in the healthy control group 2 volunteers, total 4 eyes (13.3%) were classified among subjects with ocular rosacea.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of ocular rosacea may be highly difficult for the ophthalmologist if the ocular symptoms are imperceptible or non-specific [5]. A significant limitation on the diagnosis of ocular rosacea is limited awareness of the attending doctor, manifested for example in the small cohorts of patients in studies even after a longer period of observation [17]. Differential diagnostics of other ocular pathologies with a similar finding, such as dry eye syndrome, may be demanding especially at times when the ophthalmologist is not certain about the presence of skin affliction, and may therefore attribute the ocular affliction to another ocular pathology [5]. Cooperation between an ophthalmologist and dermatologist plays an important role in improving diagnosis.

In a systematic review from 2018, the ETR form was considered the most common subtype of rosacea, appearing in 70–80% of cases [5], as is also documented by our cohort. According to Jabbehdari et al., the ocular form of rosacea may appear in all skin forms of rosacea, by which ocular rosacea would become a mere anatomical manifestation of a skin condition [3].

In our cohort the average time from the beginning of the complaints to the determination of the diagnosis was within a range from 15 days to 126 months. This data is not presented in the studies available to us, which can be explained by the difficulty of diagnosis and the underestimation of diagnosis. The incidence of individual symptoms of ocular rosacea differs in the individual studies within the range of dozens of percentage points, which is due to the very small cohorts of patients [4,9].

In ocular rosacea, inflammation is present in the Meibomian glands, which resemble the sebaceous glands, and MGD is described as one of the most common symptoms [1,5,9]. MGD leads to an abnormal composition of the lipid layer of the lachrymal film, and later to the occurrence of dry eye [5]. Dryness of the eyes and recurrent chalazion are often the first key to the diagnosis of ocular rosacea [5]. MGD is a non-specific finding that is present in 39% of the population, while in patients with rosacea it is present in as many as 92% [4,9]. In our cohort we diagnosed MGD in all patients, in whom an improvement was achieved in 67.6%.

Closely connected with MGD is anterior blepharitis, which occurred in more than one half of the patients, whose common treatment is a core factor for success. The severity and type of skin affliction are not linked with the severity of ocular complaints, as is evident also in our cohort [12].

Changes in the conjunctiva are another important symptom of the inflammatory process of rosacea, primarily affecting the bulbar conjunctiva with interpalpebral distribution. The severity consists in chronicity, in which scarring may even occur. In the most severe cases it can lead to shallowing of the fornices, the formation of symblepharons, entropion and trichiasis [4]. In our cohort this was the most common manifestation of the pathology, together with MGD.

Peripheral corneal infiltrates or vascularization and epitheliopathy, usually localized in the lower half of the cornea, are among the most common findings on the cornea, appearing in 25–50% of patients with ocular rosacea [4,9]. This condition may progress as far as peripheral corneal thinning and the occurrence of irregular astigmatism [9]. In our cohort corneal affliction was present in 12 patients, 21 eyes in total (30.1%).

Overall, the value of the Schirmer’s test in patients with rosacea was reduced in comparison with healthy control subjects [18]. Pathological TBUT was recorded in 29 patients, in a total of 50 eyes (73.5%). This jointly confirms that dry eye syndrome is a frequent problem of patients with the ocular form of rosacea [18].

Subjective complaints were very frequent, in practice this concerned the most common primary reason for visiting our clinic. Symptoms included a feeling of a FB, burning and dryness of the eyes, also lachrymation and itching of the eyes. After treatment a very rapid alleviation of the complaints was achieved.

At present no diagnostic test exists in order to confirm the doctor’s suspicions. The first studies have now been published describing the difference in the glycan profile in the tears of patients and healthy control subjects 9,19]. A similar analysis was conducted on the tears of the patients included in this study, in which it was possible to differentiate between the tears of patients with ocular rosacea from healthy control subjects in 98.4% of cases with the aid of a developed analytical method and subsequent OPLS-DA. The glycomic profile of tears changed during the course of treatment, when the patients shifted in a direction towards the control group in terms of their tear composition. However, this did not apply to all the samples, which may have been caused by the higher degree of severity of the pathology, application of a less aggressive therapy, erroneous classification of the patient, imprecision of the analytical method, or last but not least poor compliance with treatment.

A limitation of our study is the small cohort of patients and the short observation period. Based on the observed symptoms and subjective complaints rosacea was diagnosed in the patients, which was furthermore confirmed by a glycomic analysis in 98.4% of patients. Despite the high percentage of success in classifying patients, this still nevertheless represents a non-specific method of diagnosing ocular form of rosacea. An analysis of glycan changes has already been applied also in other pathologies such as atopy, diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis [20]. In addition, the used analytical method is very costly and therefore cannot be simply introduced into clinical practice. As a result it is essential to conduct further research in this area with the aim of identifying changes in the glycomic profile of tears which is specific to the ocular form of rosacea, and subsequently to develop a diagnostic method established specifically on these selected glycans. After configuration of treatment it would then be possible to observe the development of the pathology with a positive trend for improvement of the investigated parameters.

CONCLUSION

Diagnosis of ocular rosacea is difficult, nonetheless timely identification and commencement of therapy may prevent the onset of irreversible changes and bring about both especially pronounced subjective alleviation and objective improvement within a relatively short time. Emphasis is placed on correct patient education regarding the nature of the pathology and on cooperation in care of the eyelids and eyes as such. The treatment itself is demanding on the patient both in mechanical terms, since patients must warm and massage their eyelids, as well as in financial terms. In general compliance is low with regard to the application of artificial tears, due to the time burden placed on young patients, whereas in the case of older patients problems of financing quality artificial tears predominate, resulting in failure to adhere to the recommended frequency of application. A significant problem occurs in the sphere of outpatient care, when patients are repeatedly sent home with a diagnosis of conjunctivitis and different types of antibiotics, which in their result have no effect, thereby contributing not only to the onset of ocular complications, but also to an intensification of antibiotic resistance.

In future it shall be highly important to find a biomarker that is typical of ocular form of rosacea and to develop a simple diagnostic test for timely detection of these patients, in which an analysis of the glycomic profile of tears may be one of the potential options.

Acknowledgements

We express our heartfelt thanks to Dr. Kateřina Plachká, Dr. Hana Chmelařová, and the team of the Department of Analytical Chemistry at the Faculty of Pharmacy at Charles University in Hradec Králové for their assistance with the processing and analysis of the tear samples.

Sources

1.Tavassoli S, Wong N, Chan E. Ocular manifestations of rosacea: A clinical review. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2021;49(2):104-117.

2. Saá FL, Cremona F, Chiaradia P. Association Between Skin Findings and Ocular Signs in Rosacea.Turk J Ophthalmol. 2021;51(6):338-343.

3. Jabbehdari S, Memar OM, Caughlin B, Djalilian AR. Update on the pathogenesis and management of ocular rosacea: an interdisciplinary review. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2021;31(1):22-33.

4. Alvarenga LS, Mannis MJ. Ocular rosacea. Ocul Surf. 2005;3(1):41-58.

5. Sinikumpu SP, Vähänikkilä H, Jokelainen J, Tasanen K, Huilaja L. Ocular Symptoms and Rosacea: A Population-Based Study. Dermatology. 2022;238(5):846-850.

6. Ihrisky SA. Rozacea-současný pohled. Cesk Dermatol. 2018;92(5):161-204.

7. Wladis EJ, Adam AP. Treatment of ocular rosacea. Surv Ophthalmol . 2018;63(3):340-346.

8. Vieira AC, Mannis MJ. Ocular rosacea: common and commonly missed.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 Suppl 1):S36-41.

9. Awais M, Anwar MI, Iftikhar R, Iqbal Z, Shehzad N, Akbar B. Rosacea – the ophthalmic perspective. Cutan Ocul Toxicol . 2015;34(2):161-166.

10. Rulcová J. Rozacea. In: Nevoralová Z, Rulcová J, Benáková N, editors. Obličejové dermatózy: Mladá Fronta, Edice Aeskulap; 2018.

11. Sobolewska B, Schaller M, Zierhut M. Rosacea and Dry Eye Disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm . 2022;30(3):570-579.

12. Vieira AC, Höfling-Lima AL, Mannis MJ. Ocular rosacea--a review. Arq Bras Oftalmol . 2012;75(5):363-9.

13. Tan J, Almeida LMC, Bewley A. Updating the diagnosis, classification and assessment of rosacea: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(2);431-438.

14. Prabhasawat P, Ekpo P, Uiprasertkul M, et al. Long-term result of autologous cultivated oral mucosal epithelial transplantation for severe ocular surface disease.Cell Tissue Bank. 2016;17.

15. Kılıç Müftüoğlu İ, Aydın Akova Y. Clinical Findings, Follow-up and Treatment Results in Patients with Ocular Rosacea. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2016;46(1):1-6.

16. Nichols KK, Mousavi M. Chapter 2 - Clinical Assessments of Dry Eye Disease: Tear Film and Ocular Surface Health. In: Galor A, editor. Dry Eye Disease: Elsevier; 2023. p. 15-23.

17. Al-Amry MA, Al-Ghadeer HA. Ocular acne rosacea in tertiary eye center in Saudi Arabia.Int Ophthalmol. 2018;38(1):59-65.

18. Lazaridou E, Fotiadou C, Ziakas NG, Giannopoulou C, Apalla Z, Ioannides D. Clinical and laboratory study of ocular rosacea in northern Greece. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2011;25(12):1428-1431.

19. Vieira AC, An HJ, Ozcan S, Kim J-H, Lebrilla CB, Mannis MJ. Glycomic Analysis of Tear and Saliva in Ocular Rosacea Patients: The Search for a Biomarker. Ocul Surf. 2012;10(3):184-192.

20. Messina A, Palmigiano A, Tosto C et al. Tear N-glycomics in vernal and atopic keratoconjuctivitis. Allergy 2021;76 : 2500-2509

Labels

OphthalmologyArticle was published in

Czech and Slovak Ophthalmology

2024 Issue 2

-

All articles in this issue

- Multimodal Imaging of Choroidal Nodules in Neurofibromatosis Type I

- Diagnostic Challenges of Ocular Rosacea

- Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. A Review

- Comparison of Early Vision Quality of SBL-2 and SBL-3 Segmented Refractive Lens

- The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Quality of Examination in Eye Clinics in the Czech Republic – Questionnaire Study

- Kaposi’s Sarcoma. A Case Report

- Czech and Slovak Ophthalmology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- About the journal

Most read in this issue

- Diagnostic Challenges of Ocular Rosacea

- Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. A Review

- Multimodal Imaging of Choroidal Nodules in Neurofibromatosis Type I

- Kaposi’s Sarcoma. A Case Report