-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Heritable Change Caused by Transient Transcription Errors

Transmission of cellular identity relies on the faithful transfer of information from the mother to the daughter cell. This process includes accurate replication of the DNA, but also the correct propagation of regulatory programs responsible for cellular identity. Errors in DNA replication (mutations) and protein conformation (prions) can trigger stable phenotypic changes and cause human disease, yet the ability of transient transcriptional errors to produce heritable phenotypic change (‘epimutations’) remains an open question. Here, we demonstrate that transcriptional errors made specifically in the mRNA encoding a transcription factor can promote heritable phenotypic change by reprogramming a transcriptional network, without altering DNA. We have harnessed the classical bistable switch in the lac operon, a memory-module, to capture the consequences of transient transcription errors in living Escherichia coli cells. We engineered an error-prone transcription sequence (A9 run) in the gene encoding the lac repressor and show that this ‘slippery’ sequence directly increases epigenetic switching, not mutation in the cell population. Therefore, one altered transcript within a multi-generational series of many error-free transcripts can cause long-term phenotypic consequences. Thus, like DNA mutations, transcriptional epimutations can instigate heritable changes that increase phenotypic diversity, which drives both evolution and disease.

Published in the journal: Heritable Change Caused by Transient Transcription Errors. PLoS Genet 9(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003595

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003595Summary

Transmission of cellular identity relies on the faithful transfer of information from the mother to the daughter cell. This process includes accurate replication of the DNA, but also the correct propagation of regulatory programs responsible for cellular identity. Errors in DNA replication (mutations) and protein conformation (prions) can trigger stable phenotypic changes and cause human disease, yet the ability of transient transcriptional errors to produce heritable phenotypic change (‘epimutations’) remains an open question. Here, we demonstrate that transcriptional errors made specifically in the mRNA encoding a transcription factor can promote heritable phenotypic change by reprogramming a transcriptional network, without altering DNA. We have harnessed the classical bistable switch in the lac operon, a memory-module, to capture the consequences of transient transcription errors in living Escherichia coli cells. We engineered an error-prone transcription sequence (A9 run) in the gene encoding the lac repressor and show that this ‘slippery’ sequence directly increases epigenetic switching, not mutation in the cell population. Therefore, one altered transcript within a multi-generational series of many error-free transcripts can cause long-term phenotypic consequences. Thus, like DNA mutations, transcriptional epimutations can instigate heritable changes that increase phenotypic diversity, which drives both evolution and disease.

Introduction

Stable phenotypic change is mostly associated with DNA alteration [1], the hardware of the cell, but rarely as the consequence of errors in the transmission of cellular genetic programs, the software of the cell [2], [3]. Transcription factors play a critical role in establishing cellular programs and heritable cellular identity [4], as elegantly shown by somatic cell nuclear transfer [5] and more recently reprogramming of differentiated cells into pluripotent cells [6]. Among cellular genetics programs, bistable gene networks play an important role in cellular differentiation and identity by allowing expression of multiple stable and heritable phenotypes from one single genome [7]. Examples of bistable systems include the E. coli lactose-operon-repressor system [8], the lambda bacteriophage lysis–lysogeny switch [9], the genetic toggle switch in bacteria [10] and human cells [11], phosphate response in yeast [12], cellular signal transduction pathways in Xenopus [13], HIV virus development [14], and the “restriction point”: the critical switch by which mammalian cells commit to proliferation and become independent of growth stimulation in cancer [15]. Recent studies on single cell genealogy analysis have revealed that heritable stochastic change can occur by dysregulation of bistable regulatory networks [16], [17]. This phenotypic switching has been associated with infrequent large bursts in transcription, generated by the stochastic dissociation of a transcription factor from its DNA regulatory site and resulting in a change of expression pattern [17].

Our previous studies suggested that transcription infidelity could contribute to stochastic heritable phenotypic change in a bistable gene network [18]. We showed that the removal of transcription fidelity factors in the cell, GreA and GreB (functional analogs of eukaryotic TFIIS), triggers heritable stochastic change [18]. Therefore, we proposed that an overall decrease in transcription fidelity affecting all nascent transcripts in the cell can increase stochastic switching in this system by altering the quality of the transcription factor involved in the bistable switch. However, these transcription fidelity factors also have other functions in transcription initiation and elongation [19]. In addition, a global decrease in transcription fidelity may indirectly trigger phenotypic switching by globally impacting the physiology of the cell, instead of directly altering the transcription factor mRNA [20], [21]. Due to the unstable nature of mRNA, the direct capture of the erroneous mRNA responsible for the phenotypic switch is not currently possible since by the time the cell exhibits the new phenotype, the initial erroneous mRNA will have been degraded. Hence, we have now developed a novel genetic approach to show that mRNA errors specifically in a transcription factor involved in a bistable switch can directly trigger heritable phenotypic change in a clonal cell lineage.

In E. coli, the lac operon has been shown to behave like a bistable switch and is considered a model system of gene regulation. The lac operon comprises a positive feedback loop that allows bistability under a specific concentration of inducer, thio-methylgalactoside (TMG), known as the maintenance concentration [8]. The lactose permease protein (encoded by the lacY gene) transports its own inducer, which in turn activates permease synthesis by derepressing its operon via inactivation of the lac repressor. Due to this autocatalytic positive feedback loop the lac operon exhibits two persistent and heritable expression states depending on the cellular history [8], [18], [22]. In the presence of the maintenance level of inducer, cells with permease will stay induced (ON) and cells without permease will stay uninduced (OFF) but will have a probability of switching ON. In their classic experiment, Novick and Weiner showed the persistence of the two heritable expression states for over 180 generations in a chemostat [8].

To directly test that transcription errors in the mRNA of a transcription regulator can promote phenotypic change, we engineered a transcriptional error-prone sequence into the lacI repressor gene, which dictates the fate of a heritable ON/OFF epigenetic switch in the lac operon. If our model that transcription errors cause epigenetic switching is correct, we predict that this engineered transcription error-prone sequence would lead to increased epigenetic ON-switching in the bistable lac system.

Results and Discussion

Engineering an Error-prone Sequence in the lacI Transcript

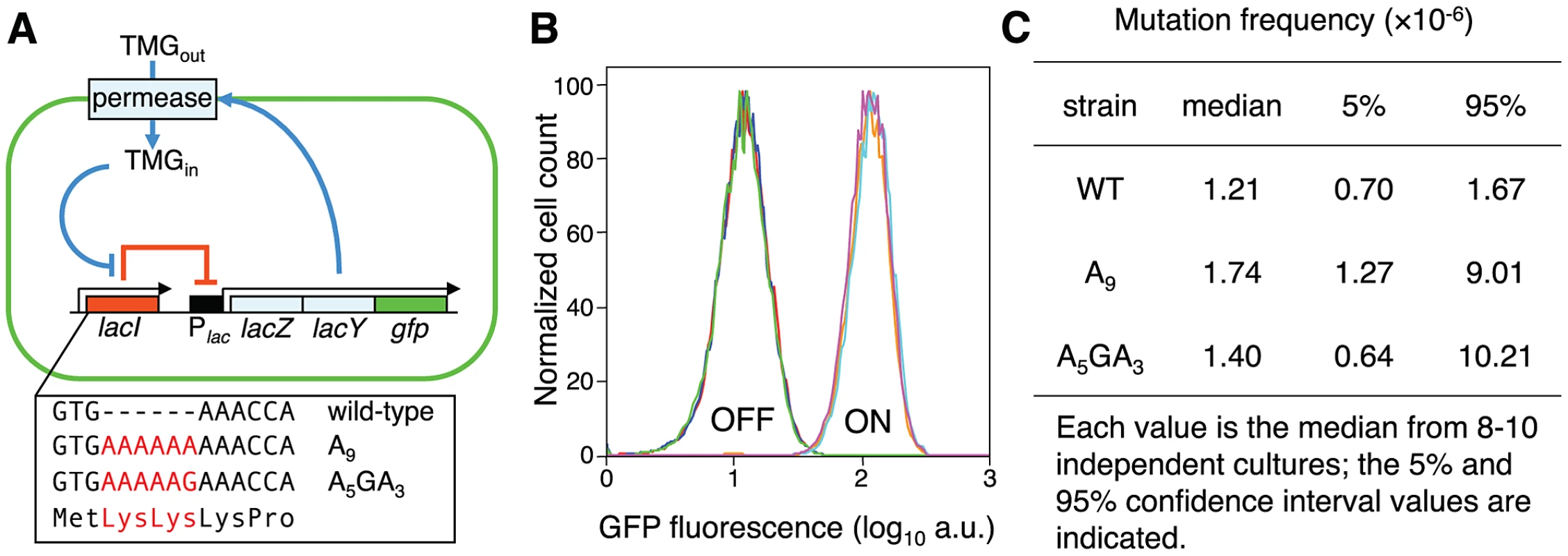

To directly look at the consequence of transcription errors in lacI mRNA, we elongated the native A3 sequence at the 5′ end of the chromosomal lacI gene to an A9 run or an A5GA3 control sequence (Figure 1A; Figure S4A) and thereby created a novel lac repressor that has two additional N-terminal appended Lys residues. Monotonous runs of adenines in DNA are hotspots for RNA polymerase slippage events during transcription in E. coli [23]–[26], Thermus thermophilus [27], yeast [25], [28] and human cells [29]–[31]. During transcription, the ∼8 bp hybrid between the nascent RNA chain and the DNA template maintains the proper register of the RNA transcript [32]. With a T9 run in the template (and an A9 run in the coding strand, as is found in our study), the growing chain with eight or nine A residues can dissociate from the template and realign out of frame, while still maintaining the required 8 bp RNA∶DNA hybrid. Therefore, the minimum length of the T run to promote transcriptional slippage is T9 [24], [27], [28]. In a wild-type gene, this transcriptional slippage results in the addition or deletion of a ribonucleotide in the A run in the transcript, resulting in a shift in the open reading frame and producing a burst of nonfunctional truncated protein.

Fig. 1. Novel system to study the consequences of error-prone transcription sequences.

(A) Under maintenance conditions, the lac operon is OFF (indicated by the solid red line) and the inducer TMG remains extracellular; stochastic events that lead to a transient derepression of the lac operon will initiate an autocatalytic positive-feedback response (indicated by solid blue lines). The box highlights the first three codons of the wild-type lac repressor gene and the Lys-Lys additions encoded by the A9 and A5GA3 lacI alleles (in red). (B) The lacI A9 and A5GA3 Lys-Lys N-terminal addition alleles encode functional lac repressors. Representative flow cytometry analyses measuring GFP fluorescence of OFF and ON populations of wild-type (red, brown), A9 (blue, light blue) and A5GA3 (green, violet) lacI cells produce identical histograms; 104 cells of each strain were interrogated. (C) Forward lacI+→lacI− mutation frequencies. No significant difference in mutation frequency between the A9 and A5GA3 strains is observed (Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test, p = 0.23). The wild-type strain is added for comparison. Single cell analysis by flow cytometry shows that the GFP fluorescence histograms produced from OFF and ON populations of wild-type, A9 and A5GA3 repressor strains are identical demonstrating that the engineered Lys-Lys addition does not perturb repressor function (Figure 1B). The altered repressors still recognize and bind the lac operator, negatively regulate the lac operon and remain responsive to TMG, which binds to the structurally distinct C-terminal core domain and induces an allosteric transition in lac repressor so that it no longer binds to the lac operator. Moreover, all three repressor allele strains (wild-type, A9 and A5GA3) exhibit the same basal level of β-galactosidase activity in OFF populations indicating that the altered repressors bind as well as the wild-type repressor to the lac operator (Figure S4B). In addition, there is no difference in the spontaneous lacI+→lacI− mutation frequency for these two altered lacI alleles (Figure 1C; Text S1). Finally, the A9 and A5GA3 repressor/lac operon gene networks also exhibit bistability and hysteresis as has been shown for the native lac system (Figures 2, 3A,B; Figure S4C) [8], [18], [22]. To interrogate a larger number of cells, we used flow cytometry (Figure S1) and validated this method by showing that the frequencies of switching in diverse genetic backgrounds are similar to what we previously published (Figure S2). Thus, the discrimination afforded by flow cytometry analysis of GFP fluorescence between ON and OFF cells for the wild-type and variant lacI alleles is sensitive and sufficient to monitor stochastic switching.

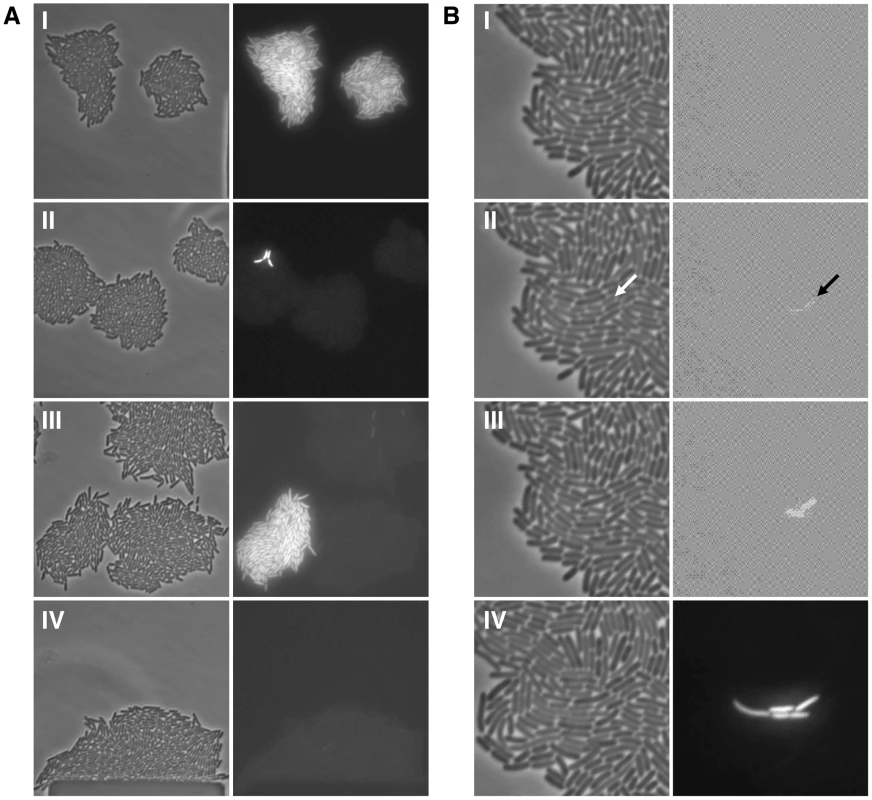

Fig. 2. Bistability, hysteresis and stochastic switching in the lac system.

(A) Single lacI A9 cells in minimal succinate media ± maintenance TMG were grown into microcolonies in a microfluidic flow chamber (approximately 100 cell divisions per microcolony originating from a single cell; number of divisions equals final number of cells in a microcolony minus 1). Comparison of bright field images (panel series on the left) with GFP fluorescence images (panel series on the right) allows clear distinction between OFF and ON cells in the microcolony. (I) panels show microcolonies that arose from single ON cells that were subsequently grown in the presence of maintenance level TMG; (II) panels show mirocolonies that arose from single OFF cells that were subsequently grown in the presence of maintenance level TMG; (III) panels show mirocolonies that arose from single OFF and single ON cells that were subsequently grown in the presence of maintenance level TMG; (IV) panels show a mirocolony that arose from ON cells that were subsequently grown in the absence of maintenance level TMG. Exposure to fluorescence illumination was 3000 ms. (B) A single lacI A9 cell in minimal succinate media+maintenance TMG was grown into a microcolony in a microfluidic flow chamber and monitored by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. Presented here are four still images from a full time series of images (available as Movie S1; images shown correspond to frames 25, 28, 30, 39). Comparison of bright field images (panel series on the left) with GFP fluorescence images (panel series on the right) allows distinction between OFF and ON cells in the microcolony. (I) all cells in the microcolony are OFF (100 ms exposure to fluorescence illumination); (II) a recently divided cell is just becoming ON indicated by the arrow (100 ms exposure to fluorescence illumination); (III) the now separated cells have become ON (100 ms exposure to fluorescence illumination); (IV) further cell division has occurred in the microcolony creating one lineage of ON cells amongst many other lineages of OFF cells (3000 ms exposure to fluorescence illumination). The 100 ms exposure time images were over-exposed using the ColorSync Utility to observe the faint fluorescence signal. Fig. 3. The error-prone A9 run in the lacI transcript increases stochastic phenotypic switching.

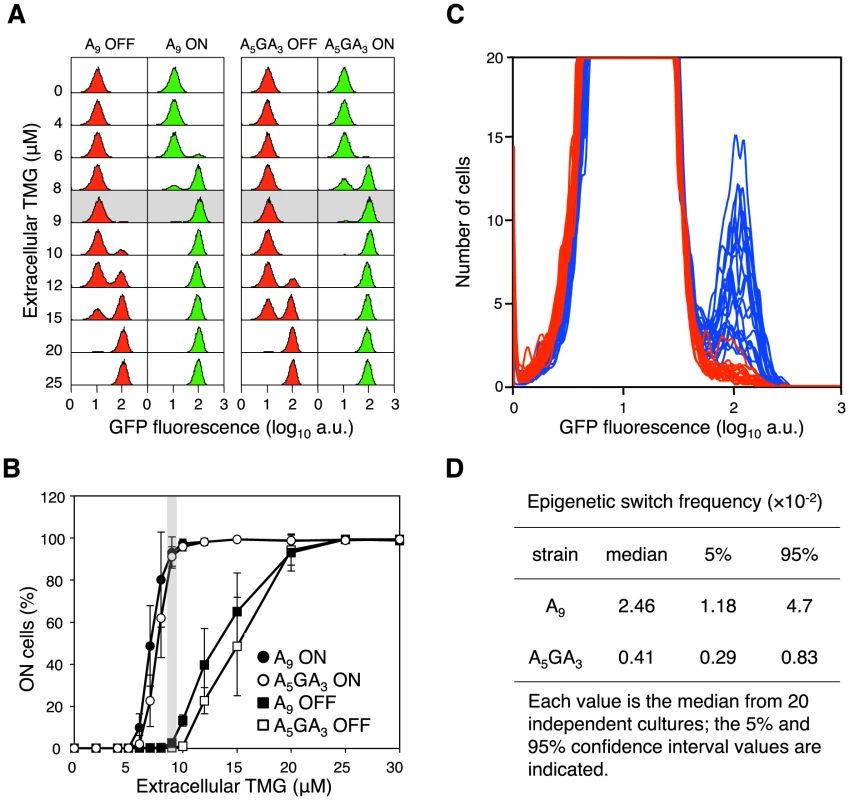

(A) Representative flow cytometry GFP fluorescence histogram series of A9 and A5GA3 lacI cells that were originally ON (green histograms) or OFF (red histograms) were sub-cultured and grown in media containing various concentrations of TMG indicated on the vertical axis (104 cells interrogated). Below 5 µM TMG and above 20 µM TMG, the previous history of the cell (ON or OFF) does not affect the current state of the cell; between these TMG concentrations the system exhibits hysteresis. The shaded area highlights the maintenance concentration of 9 µM TMG for these strains. (B) Cells that were originally ON or OFF were sub-cultured and grown in media containing various concentrations of TMG, as above. Each value is the average ± SD from 5 to 15 independent cultures. The shaded area highlights the maintenance concentration of 9 µM TMG for these strains. (C) OFF A5GA3 lacI cells (red histograms) and A9 lacI cells (blue histograms) were diluted and grown in media containing 9 µM TMG. After 42 h growth, flow cytometry was performed to determine the frequency of epigenetically ON cells in 20 independent cultures of each strain; the A5GA3 histograms are superimposed over the A9 histograms (104 cells interrogated). (D) The A9 epigenetic-switch frequency is significantly increased over the A5GA3 value (Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test, p<0.001). Transcriptional Slippage in the lacI Gene Increases Epigenetic Stochastic Switching

To determine the proportion of cells that are ON, we used the green fluorescent protein gene integrated within the lac operon (Figure 1A) [18]. During growth of OFF cells in a maintenance concentration of TMG, if a cell suffers a stochastic event leading to derepression of the lac operon, e.g. a transcription slippage error in lacI, the lac operon will be transiently derepressed triggering permease synthesis and activation of the autocatalytic positive-feedback loop, resulting in green fluorescent cells [18]. As a result, the OFF state will transition to the ON state and be heritably maintained in the following generations, mimicking lacI mutation in this system (i.e. transient stochastic events in information transfer can have heritable phenotypic consequences; Figure 2A,B) [8], [18]. We calculate the switch frequency as number of ON cells over the total number of cells interrogated, following the convention used in determining lacI− mutation frequencies [33]. The observed ON switch frequency is therefore dependent on both the number of switch events that have occurred and the number of generations after a discrete switch event has occurred, as in a classical fluctuation test; our experiments run for ∼28 bacterial generations (see Materials and Methods).

Between the two strains harbouring A9 and A5GA3 alleles, we can assess how slippery transcription sequences affect stochastic switching in the bistable lac system. We observe a 6 to 12-fold increase in switch frequency (Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test, p<0.001) for the A9 construct compared with the A5GA3 control in a wild-type background at the maintenance concentration of TMG (Figure 3C,D; Figure S5). This A9 epigenetic switch frequency is fully 10,000 times greater than the genetic lacI− mutation frequency demonstrating that it is not mutation underlying the observed stochastic switching.

In addition, the observed increase in phenotypic switch frequency cannot be explained by problems in transcription initiation or early termination for the following reasons. First, native lacI mRNA, produced from a weak constitutive promoter, includes a 28 nucleotide (nt) untranslated leader sequence before the GTG initiation codon [34] and the A9 run (or the A5GA3 broken run) should not affect transcription initiation. Since the nascent transcript is 31 nt in length before the A9 run is first encountered, transcription of this sequence will be the processive synthesis of RNA as an RNA polymerase-DNA transcription complex and not as an RNA polymerase-promoter initial transcribing complex [35]. Second, aborted transcripts, if they occur from the lacI promoter, are also not relevant here; abortive events occur within 8–15 nt from the promoter, far away from the A9 (and the A5GA3) sequence. The absence of GreA function increases transcription abortion [35], however, we see no difference in transcript elongation in lacI monitored by a lacIZYA fusion in the absence of GreA, GreB or GreA,B function with these constructs whereas we see a significant increase in phenotypic switching in the absence of GreA,B (Figure 4). Third, we show that ±1 frameshifting in the coding sequence of lacI does not cause early transcription termination before downstream transcription into the lac operon (Figure S6). Together these experiments suggest that perturbations in transcription initiation and early termination are not involved in the increased OFF to ON switching frequency we observe. The net decrease in functional repressor in a cell, due to transcription error, may further require the dilution of ‘old’ wild-type repressors via partitioning during cell division to promote stochastic switching [36].

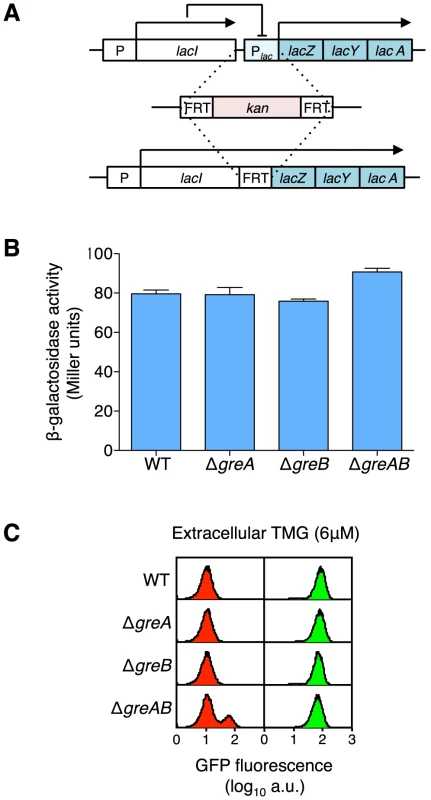

Fig. 4. Creation of a lacIZYA operon fusion to assess the levels of gene expression from the lacI gene promoter.

(A) An operon fusion was created by first inserting a kanamycin cassette from pKD4 (Table S3) into the intervening region between lacI and lacZ and then, via a flippase reaction, removing most of lac operator O3, the complete lac promoter and lac operator O1. Therefore, the lacIZYA fusion transcript is under the expression of the weakly constitutive lacI promoter with no interference from any lac repressor binding (lac repressor does not negatively regulate lac expression through O2 alone) [60]. The complete sequence of the intervening region from the TGA stop codon of the lacI gene to the ATG start codon of the lacZ gene is shown in Figure S3. (B) Expression levels of the lacIZYA operon fusion strains are equivalent regardless of GreA, GreB or GreAB status indicating the absence of any or all Gre functions does not influence overall lac expression levels. Cells were grown in minimal A salts plus glucose and β-galactosidase levels were determined by the method of Miller [33]; the average ± SD for three independent cultures is shown. To make functional β-galactosidase in this fusion strain the transcription complex must produce at least a 4,271 nt transcript including the lacI non-translated leader, the lacI gene, the FRT scar sequence and the lacZ gene; if the transcript terminates after lacA, at the usual lac termination site, then the entire transcript will be over 6.2 kb in length. (C) At maintenance level of TMG, the absence of GreA or GreB does not increase stochastic switching over wild-type levels but when both Gre functions are absent a significant increase in stochastic switch frequency is observed [18]. Representative flow cytometry histograms of wild-type, ΔgreA, ΔgreB and ΔgreAB cells that were originally ON (green histograms) or OFF (red histograms) were sub-cultured and grown in media containing a maintenance level of 6 µM TMG. All strains are equally responsive to TMG at this concentration (all ON populations remain ON, i.e., maintain their previous state), but only OFF ΔgreAB cells exhibit an increased stochastic switching frequency over that observed when wild-type OFF cells were grown at maintenance level of TMG; each histogram represents the interrogation of 104 cells. Therefore, it is not an overall decrease of lacI expression that causes the significant increase in stochastic switch frequency in the absence of GreAB. Transcription not Translation Errors Influence Stochastic Switching

To gain experimental evidence that transcription error and not translational frameshifting promotes stochastic switching in the A9 lacI allele, we introduced the A9 and A5GA3 lacI alleles into a ΔgreAB strain that contains deletions of the greA and greB genes that encode auxiliary fidelity factors that facilitate the proofreading of misincorporations that arise in nascent mRNAs during transcription [37]–[39]. We reasoned that if the switching is due to transcription slippage, removing transcription fidelity factors GreAB may promote more slippage and increase phenotypic switching. The increase in switch frequency in the presence of an error-prone sequence in the absence of RNA editing function is more than additive: the median switch frequency for the A9 allele in the ΔgreAB background (42.4%) is greater than the median switch frequency for the A9 allele (2.46%) and the ΔgreAB A5GA3 background (26.7%) combined (Figure 5A,B). When a slippery transcribed sequence is in a sloppy RNA transcription fidelity background, the switching frequency is significantly increased (Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test, p<0.001), suggesting that misalignments due to transcriptional frameshifting are prevented by RNA editing of the Gre factors via transcription back-tracking/correction and support the role of transcription slippages in phenotypic change.

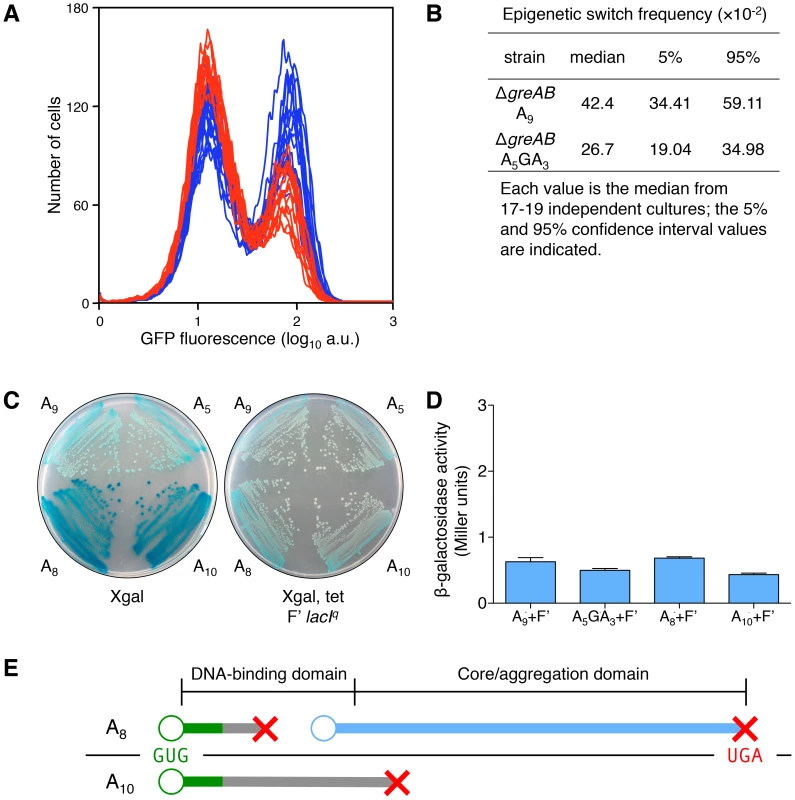

Fig. 5. Transcription errors, not translational frameshifting, at the lacI A9 sequence influences stochastic switching.

(A) Stochastic phenotypic switching is significantly increased when the error-prone A9 run is in a transcription fidelity-deficient background (ΔgreA ΔgreB cells). OFF ΔgreAB A5GA3 lacI cells (red histograms) and ΔgreAB A9 lacI cells (blue histograms) were diluted and grown in media containing 9 µM TMG. After 42 h growth, flow cytometry was performed to determine the frequency of epigenetically ON cells in 17–19 independent cultures of each strain; the histograms from the ΔgreAB A5GA3 lacI cultures are superimposed over the histograms from the ΔgreAB A9 lacI cultures; each histogram represents the interrogation of 104 cells. (B) The median for the ΔgreAB A9 lacI strain is significantly different from the ΔgreAB A5GA3 lacI value (Mann-Whitney Rank Sum Test, p<0.001). (C) To model translation frameshifting in our system we have created merodiploids that provide a 10-fold excess of wild-type transcripts over ±1 frameshift transcripts (as modeled by the A8 and A10 lacI alleles). Therefore, the ratio of wild-type transcript over frameshifted transcript, at the level of transcription (10∶1), will be a very conservative approximation of the situation that would arise if during the translation of one A9 transcript, one translational frameshift event would occur (20∶1 wild-type sub-units over frameshifted sub-units). The wild-type repressor allele is completely dominant over the frameshifted repressor alleles: left panel, the lacI allele strains without the F′; right panel, the lacI allele strains with the F′ overproducing wild-type lacI. The glucose minimal plates include Xgal (40 µg/ml) and tetracycline (Tet, 12.5 µg/ml), as indicated beneath the plate. Tet is used to maintain the F′ in the cell. (D) Quantitative measurement of the phenotype observed in (C). The level of β-galactosidase in all four strains is comparable and does not exceed 1 Miller unit, which is the basal β-galactosidase of uninduced E. coli cells [33]; the average ± SD for three independent cultures is shown. (E) A −1 translational frameshifting event at the A9 sequence would cause translation to terminate at codon 4/5 (green line denotes wild-type protein; gray line denotes frameshifted protein; red X denotes translation termination; blue line denotes translation reinitiation protein; the A9 transcript is shown as a black line with the GUG start codon in green letters and the UGA stop codon in red letters; the protein domain structure is indicated above the translation products). Therefore, no functional lac repressor sub-unit could be produced; however, it has been shown that a dominant-negative sub-unit could be produced by translational reinitiation [61]. Reinitiation could occur at codons 23, 24, 38 or 42 [34], producing repressor sub-units lacking the DNA-binding domain but the core aggregation domain would be intact and able to bind and interfere with wild-type sub-unit function. Therefore, there is the possibility that one −1 translational frameshifting event would not only decrease the net total of repressor sub-units by one, but might also decrease the cell's net lac repressors by one, since it has been shown that one dominant-negative sub-unit with three wild-type sub-units may abolish the function of the tetrameric lac repressor [42]. A +1 translational frameshifting event at the A9 sequence (generating a A10 transcript) would cause translation to terminate at codon 83/84 and would therefore only result in the net decrease of one repressor sub-unit in the cell, since no dominant-negative sub-unit can be made this far into the core domain. When the wild-type sub-unit is made at 10-fold the level of ±1 transcription frameshift events (and ±1 translation protein products), the wild-type sub-units dominate and the lac operon is repressed (as seen in the Xgal Tet F′ lacIq plate in (C) and therefore any net decrease by one translation frameshift event is negligible when compared to the net decrease in repressor sub-units due to a transcription error. When a transcription error occurs at the A9 sequence, all the nascent lac repressor sub-units will be non-functional (and/or dominant-negative); when a translational frameshift occurs at the A9 sequence, less than 1/10 of all nascent lac repressor sub-units will be non-functional (and/or dominant-negative). Furthermore, phenotypic switching has been associated with a large burst in permease synthesis [17]. An average gene transcript in E. coli will produce about 20–40 full-length polypeptides [40], [41]. Therefore, one transcription frameshift will produce 20–40 non-functional lac repressor sub-units (lac repressor is a tetramer), while one translational frameshift event will produce only one non-functional lac repressor sub-unit along with 20–40 functional lac repressor sub-units; a ratio of at least 20∶1 of functional over non-functional lac repressor sub-units will be the result. Therefore, the effects of a transcription error will be amplified nonlinearly over the original stochastic event generating tens of aberrant lac repressor polypeptides allowing a large burst of permease that is required for phenotypic change [17].

To measure the effect of translation frameshifting on lac operon induction, we created merodiploids that provide a 10-fold excess of wild-type transcripts over ±1 frameshift transcripts derived from the lacI A8 and A10 alleles we constructed on the chromosome (Table S2). We introduced an F′ factor with a wild-type lacI gene under control of the Iq up-promoter mutation, producing 10-fold more lacI transcription [42], into recA derivatives of our A8 and A10 frameshifted lacI strains (and into recA derivatives of our A9 and A5GA3 in-frame lacI strains; see Table S2). Therefore, the ratio of wild-type transcript over frameshifted transcript, at the level of transcription (10∶1), will be a very conservative approximation of the situation that would arise if during the translation of one A9 transcript, one translational frameshift event would occur since a ratio of at least 20∶1 of wild-type repressor sub-units over frameshifted sub-units would result. As shown in Figure 5C,D,E, a translation error on a pristine mRNA producing just one aberrant polypeptide amongst many wild-type polypeptides has no large effect on lac operon induction, demonstrating that more than one frameshifted repressor sub-unit is required to promote phenotypic switching.

Finally, efficient translation frameshifting is dependant on specific downstream sequence elements in E. coli [27] that are not obvious in our A9 lacI construct.

All together, these results show that insertion of a known transcription slippage sequence in the lacI transcript increases phenotypic switching in the bistable lac system due to transcription error in the mRNA and accumulation of a frameshifted and non-functional lac repressor leading to a transcription burst of lac permease.

Stochastic Errors in Information Transfer Have Heritable Phenotypic Consequences

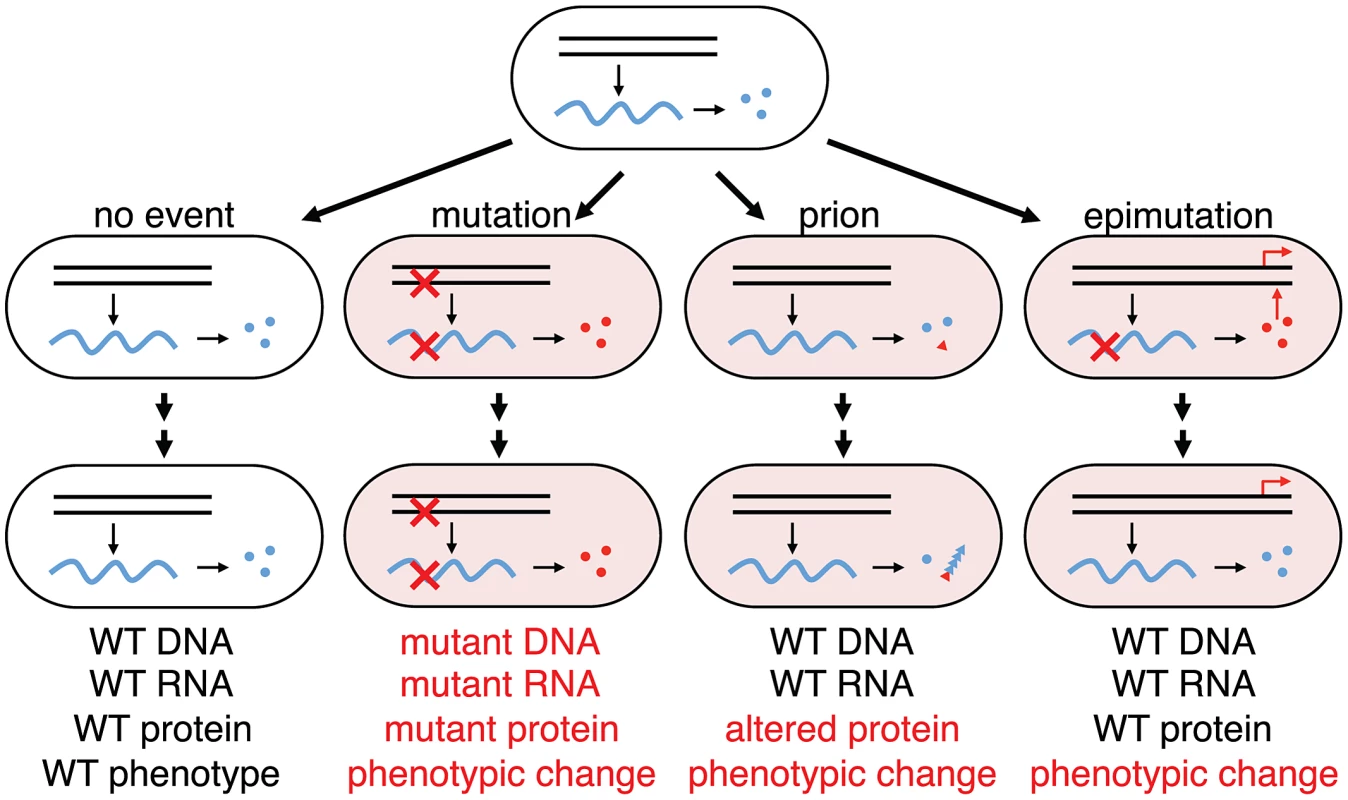

DNA makes RNA makes protein; until now, errors in making two of the three elements in information transfer, DNA replication and protein folding, have been shown to modify cellular inheritance through mutation or prion conformational change [43] (Figure 6). Our results show that acute errors in mRNA, the transient element in information transfer, can also effect heritable change when they affect transcription factors involved in bistable gene networks. Transcription errors have been shown to have phenotypic consequences for the cell, but in the cases reported so far, chronic transcription errors can provide partial function or ‘leakiness’ giving an altered phenotype from a mutant or wild type gene [29]–[31], [44]–[46]. For example, a −1 frameshift mutation in the apolipoprotein B gene in a polyA run caused hypobetalipoproteinemia and transcription slippage at the polyA track restores the reading frame by insertion of an additional A and ameliorates the disease [29], [30]. In Alzheimer's patients, it was found that −2 frameshifts accumulated in amyloid precursor and ubiquitin B transcripts over time, which are thought to be important in nonfamilial early - and late-onset forms of Alzheimer's disease [47]. In contrast to these examples of chronic transcriptional errors producing a partial phenotype, we show that one acute transcription error on a poorly transcribed mRNA may promote heritable phenotypic change due to a change of connectivity in a transcription network. Although epimutation, a heritable change in gene expression that does not affect the actual base pair sequence of DNA, is usually associated with methylation patterns and epigenetic silencing of gene expression, the heritable stochastic switching due to transient transcription error we observe here, may also be included as epimutation.

Fig. 6. Phenotypic consequences from errors in information transfer in a cellular lineage.

Wild-type genes (black parallel lines) make wild-type transcripts (blue wavy lines) make wild-type functional proteins (blue circles); mutant genes make mutant transcripts (red crosses) make mutant proteins (red circles); protein mis-folding can trigger phenotypic change by changing protein conformation to the prion state (red triangle) that can self-perpetuate by templating the aberrant conformation with nascent native proteins (blue triangles). From wild-type genes can also come altered mRNA (epimutation) making altered proteins that can perturb transcriptional networks in a nonlinear manner generating a heritable phenotypic change (red arrows) from a transient stochastic error in information transfer. In this case no trace of the error will remain in the lineage after the phenotypic change as indicated: while change through mutation will retain evidence of the original stochastic error in the progeny cell (mutant DNA, mutant RNA and mutant protein), change through epimutation will retain no evidence of the original stochastic error in the progeny cell (WT DNA, WT RNA and WT protein). Errors in DNA and RNA synthesis occur at rates of, very roughly, 10−9 and 10−5 errors per residue, respectively [48]; yeast cells in the non-prion [psi−] state spontaneously switch [43] to [PSI+] at a frequency of 10−6; the great majority of cells will not have sustained any errors in information transfer. RNA transcription errors are inevitable, ubiquitous and frequent (about 10,000 times more frequent than DNA replication errors) [48] and bistable gene networks sensitive to stochastic fluctuation in protein level are found in bacteria [17], yeast [49], fly [50], Xenopus [13], mammalian stem cells [51] and viruses such as HIV and lambda [52]. Furthermore, recent studies in E. coli [53], yeast [54] and human cells [55], [56] have shown that a majority of proteins involved in transcription networks are usually present at low abundance so it is easy to imagine that errors in one low abundant mRNA can have a drastic reduction in the protein concentration and trigger epigenetic change. So far, permanent activation or removal of transcription factors by genetic manipulation has been shown to promote a stable change of phenotype in a process known as transdifferentiation [57] and we speculate that transient disappearance of a transcription factor involved in a bistable switch may have the same phenotypic effect. Although here we focus on a slippery A9 sequence in the lacI gene, any kind of transcription error along the lacI transcript that would generate a non-functional lac repressor, may also initiate a stochastic switching event. Indeed, any transcribed DNA sequence that is problematic for RNA polymerase, due to a mono-, di-, tri - or some higher order nucleotide repeat or to hairpin or other secondary structures would produce a variety of mRNA species from the same gene. Therefore, transcription errors, epimutation, might be a general mechanism to create epigenetic heterogeneity in a clonal cell population and should be considered as one of the origins of phenotypic change that could lead to altered or aberrant cell behavior, impacting human health, including cancer if the dysregulation of key genetic bistable networks are altered by errors in transcription [58].

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains

All strains used in this study are derived from the wild-type sequenced E. coli MG1655 strain (Table S2). Manipulation of the MG1655 genome was accomplished by standard methodologies [33], [59]. To monitor the proportion of cells that are ON or OFF for lac operon expression, we have replaced the lacA gene in the wild-type E. coli MG1655 chromosome with a gfp cassette, so that when the lacZYA::gfp transcript is expressed, β-galactosidase, galactoside permease, and green fluorescent protein are produced from the lacZ, lacY, and gfp genes, respectively.

Growth Conditions and Media

To demonstrate hysteresis and bistability in lac operon expression in single cells, a bacterial culture grown in minimal A salts [33] plus MgSO4 (1 mM) with succinate (0.2%), was diluted 1∶5 in fresh medium with (ON culture) or without 1 mM TMG (OFF culture) and shaken at 37°C for 7 h. After this induction period, the two cultures were individually diluted and ∼200 cells were seeded to new tubes containing fresh medium that contained varying amounts of TMG, and shaken at 37°C for 42 h (∼28 generations). Flow cytometry was used to determine the percentage of cells that were induced for lac operon expression (ON cells).

To determine epigenetic and genetic switch frequencies, a bacterial culture grown in minimal succinate media, was diluted and ∼200 cells were seeded to new tubes containing fresh medium, with (epigenetic assay) or without (genetic assay) a maintenance level of TMG, and shaken at 37°C for 42 h. To determine genetic-mutation frequencies, dilutions of the subcultures were spread on selection plates (minimal A medium supplemented with 75 µg/ml phenyl-β-D-galactoside [Pgal] and 1.5% purified agar) and minimal A glucose (0.2%) plates and incubated for 2–3 days at 37°C. Pgal is a substrate of β-galactosidase and can act as a carbon source but does not induce lac operon expression, therefore only cells constitutively expressing β-galactosidase (lacI−) can form colonies [33].

Flow Cytometry

To determine the percentage of cells that were induced for lac operon expression (ON cells), 10 µl of culture was diluted into 300 µl filtered minimal A salts plus MgSO4 (1 mM) and subjected to flow cytometry analysis with GFP fluorescence measured in a BD FACSCanto II Flow Cytometer (Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA) with Diva acquisition software (Becton Dickinson) and FloJo analysis software (Tree Star, Inc. USA). To monitor fluorescent cells in a culture we used a narrow gating for forward and side scattering so that the most represented cell population was evaluated (Figure S1). For each independent culture 10,000 cells were interrogated.

Microscopy and Microfluidics

To follow the growth of single cells into microcolonies we used the CellASIC ONIX Microfluidic Platform (Millipore) including microfluidic perfusion system, microfluidic flow chamber for bacteria (BO4A plates) and FG software. Time-lapse microscopy was performed using a Zeiss HAL100 inverted fluorescence microscope. Fields were acquired at 100× magnification with an EM-CCD camera (Hammamatsu). Bright field and fluorescence (EGFP cube = Chroma, #41017; X-Cite120 fluorescence illuminator [EXFO Photonic Solutions]) images were acquired and image analysis was performed using AxioVision Rel. 4.6 (Zeiss). To maintain a constant 37°C environment throughout the experiment, the microscope was housed in an incubation system consisting of Incubator XL-S1 (PeCon) controlled by TempModule S and Heating Unit XL S (Zeiss).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. RandoOJ, VerstrepenKJ (2007) Timescales of genetic and epigenetic inheritance. Cell 128 : 655–668 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.023

2. DrummondDA, WilkeCO (2009) The evolutionary consequences of erroneous protein synthesis. Nat Rev Genet 10 : 715–724 doi:10.1038/nrg2662

3. SatoryD, GordonAJ, HallidayJA, HermanC (2011) Epigenetic switches: can infidelity govern fate in microbes? Curr Opin Microbiol 14 : 212–217 doi:10.1016/j.mib.2010.12.004

4. MonodJ, JacobF (1961) General conclusions: teleonomic mechanisms in cellular metabolism, growth, and differentiation. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 26 : 389–401.

5. PasqueV, JullienJ, MiyamotoK, Halley-StottRP, GurdonJB (2011) Epigenetic factors influencing resistance to nuclear reprogramming. Trends Genet 27 : 516–525 doi:10.1016/j.tig.2011.08.002

6. TakahashiK, TanabeK, OhnukiM, NaritaM, IchisakaT, et al. (2007) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131 : 861–872 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019

7. DubnauD, LosickR (2006) Bistability in bacteria. Mol Microbiol 61 : 564–572 doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05249.x

8. NovickA, WeinerM (1957) Enzyme induction as an all-or-none phenomenon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 43 : 553–566.

9. Ptashne M (2004) A genetic switch. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 164 p.

10. GardnerTS, CantorCR, CollinsJJ (2000) Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature 403 : 339–342 doi:10.1038/35002131

11. KalmarT, LimC, HaywardP, Muñoz-DescalzoS, NicholsJ, et al. (2009) Regulated fluctuations in Nanog expression mediate cell fate decisions in embryonic stem cells. PLoS Biol 7: e1000149 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000149.g008

12. WykoffDD, RizviAH, RaserJM, MargolinB, O'SheaEK (2007) Positive feedback regulates switching of phosphate transporters in S. cerevisiae. Mol Cell 27 : 1005–1013 doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.022

13. FerrellJE, MachlederEM (1998) The biochemical basis of an all-or-none cell fate switch in Xenopus oocytes. Science 280 : 895–898.

14. WeinbergerLS, DarRD, SimpsonML (2008) Transient-mediated fate determination in a transcriptional circuit of HIV. Nat Genet 40 : 466–470 doi:10.1038/ng.116

15. YaoG, LeeTJ, MoriS, NevinsJR, YouL (2008) A bistable Rb–E2F switch underlies the restriction point. Nat Cell Biol 10 : 476–482 doi:10.1038/ncb1711

16. KaufmannBB, YangQ, MettetalJT, van OudenaardenA (2007) Heritable stochastic switching revealed by single-cell genealogy. PLoS Biol 5: e239 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050239

17. ChoiPJ, CaiL, FriedaK, XieXS (2008) A stochastic single-molecule event triggers phenotype switching of a bacterial cell. Science 322 : 442–446 doi:10.1126/science.1161427

18. GordonAJE, HallidayJA, BlankschienMD, BurnsPA, YatagaiF, et al. (2009) Transcriptional infidelity promotes heritable phenotypic change in a bistable gene network. PLoS Biol 7: e44 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000044.st002

19. StepanovaE, LeeJ, OzerovaM, SemenovaE, DatsenkoK, et al. (2007) Analysis of promoter targets for Escherichia coli transcription elongation factor GreA in vivo and in vitro. J Bacteriol 189 : 8772–8785 doi:10.1128/JB.00911-07

20. KaplanC (2009) Alternate explanation for observed epigenetic behavior? PLoS Biol 7: e44 Available: http://www.plosbiology.org/annotation/listThread.action?root=22157.

21. GordonAJE (2009) Pregnant pauses? PLoS Biol 7: e44 Available: http://www.plosbiology.org/annotation/listThread.action?root=9457.

22. OzbudakEM, ThattaiM, LimHN, ShraimanBI, Van OudenaardenA (2004) Multistability in the lactose utilization network of Escherichia coli. Nature 427 : 737–740 doi:10.1038/nature02298

23. ChamberlinM, BergP (1962) Deoxyribonucleic acid-directed synthesis of ribonucleic acid by an enzyme from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 48 : 81.

24. WagnerLA, WeissRB, DriscollR, DunnDS, GestelandRF (1990) Transcriptional slippage occurs during elongation at runs of adenine or thymine in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Research 18 : 3529–3535.

25. StrathernJN, JinDJ, CourtDL, KashlevM (2012) Isolation and characterization of transcription fidelity mutants. Biochim Biophys Acta 1819 : 694–699 doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.02.005

26. StrathernJ, MalagonF, IrvinJ, GotteD, ShaferB, et al. (2013) The fidelity of transcription: RPB1 (RPO21) mutations that increase transcriptional slippage in S. cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 288 : 2689–2699 doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.429506

27. LarsenB, WillsNM, NelsonC, AtkinsJF, GestelandRF (2000) Nonlinearity in genetic decoding: homologous DNA replicase genes use alternatives of transcriptional slippage or translational frameshifting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97 : 1683–1688.

28. ZhouYN, LubkowskaL, HuiM, CourtC, ChenS, et al. (2013) Isolation and characterization of RNA Polymerase rpoB mutations that alter transcription slippage during elongation in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 288 : 2700–2710 doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.429464

29. LintonMF, PierottiV, YoungSG (1992) Reading-frame restoration with an apolipoprotein B gene frameshift mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89 : 11431–11435.

30. LintonMF, RaabeM, PierottiV, YoungSG (1997) Reading-frame restoration by transcriptional slippage at long stretches of adenine residues in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 272 : 14127–14132.

31. YoungM, InabaH, HoyerLW, HiguchiM, KazazianHH, et al. (1997) Partial correction of a severe molecular defect in hemophilia A, because of errors during expression of the factor VIII gene. Am J Hum Genet 60 : 565–573.

32. NudlerE, MustaevA, LukhtanovE, GoldfarbA (1997) The RNA-DNA hybrid maintains the register of transcription by preventing backtracking of RNA polymerase. Cell 89 : 33–41.

33. Miller JH (1992) A short course in bacterial genetics. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 456 p.

34. SteegeDA (1977) 5′-Terminal nucleotide sequence of Escherichia coli lactose repressor mRNA: features of translational initiation and reinitiation sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 74 : 4163–4167.

35. GoldmanSR, EbrightRH, NickelsBE (2009) Direct detection of abortive RNA transcripts in vivo. Science 324 : 927–928 doi:10.1126/science.1169237

36. HuhD, PaulssonJ (2010) Non-genetic heterogeneity from stochastic partitioning at cell division. Nat Genet 43 : 95–100 doi:10.1038/ng.729

37. ErieDA, HajiseyedjavadiO, YoungMC, Hippel vonPH (1993) Multiple RNA polymerase conformations and GreA: control of the fidelity of transcription. Science 262 : 867–873.

38. ShaevitzJW, AbbondanzieriEA, LandickR, BlockSM (2003) Backtracking by single RNA polymerase molecules observed at near-base-pair resolution. Nature 426 : 684–687 doi:10.1038/nature02191

39. ZenkinN, YuzenkovaY, SeverinovK (2006) Transcript-assisted transcriptional proofreading. Science 313 : 518–520 doi:10.1126/science.1127422

40. KennellD, RiezmanH (1977) Transcription and translation initiation frequencies of the Escherichia coli lac operon. J Mol Biol 114 : 1–21.

41. CaiL, FriedmanN, XieXS (2006) Stochastic protein expression in individual cells at the single molecule level. Nature 440 : 358–362 doi:10.1038/nature04599

42. Müller-HillB, CrapoL, GilbertW (1968) Mutants that make more lac repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 59 : 1259–1264.

43. HalfmannR, JaroszDF, JonesSK, ChangA, LancasterAK, et al. (2012) Prions are a common mechanism for phenotypic inheritance in wild yeasts. Nature 482 : 363–368 doi:10.1038/nature10875

44. van LeeuwenF, van der BeekE, SegerM, BurbachP, IvellR (1989) Age-related development of a heterozygous phenotype in solitary neurons of the homozygous Brattleboro rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86 : 6417–6420.

45. BensonKF (2004) Paradoxical homozygous expression from heterozygotes and heterozygous expression from homozygotes as a consequence of transcriptional infidelity through a polyadenine tract in the AP3B1 gene responsible for canine cyclic neutropenia. Nucleic Acids Research 32 : 6327–6333 doi:10.1093/nar/gkh974

46. TaddeiF, HayakawaH, BoutonM, CirinesiA, MaticI, et al. (1997) Counteraction by MutT protein of transcriptional errors caused by oxidative damage. Science 278 : 128–130.

47. van LeeuwenFW (1998) Frameshift mutants of β amyloid precursor protein and Ubiquitin-B in Alzheimer's and Down patients. Science 279 : 242–247 doi:10.1126/science.279.5348.242

48. NinioJ (1991) Connections between translation, transcription and replication error-rates. Biochimie 73 : 1517–1523.

49. OzbudakEM, BecskeiA, van OudenaardenA (2005) A system of counteracting feedback loops regulates Cdc42p activity during spontaneous cell polarization. Developmental Cell 9 : 565–571 doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2005.08.014

50. WernetMF, MazzoniEO, ÇelikA, DuncanDM, DuncanI, et al. (2006) Stochastic spineless expression creates the retinal mosaic for colour vision. Nat Cell Biol 440 : 174–180 doi:10.1038/nature04615

51. MacArthurBen D, Ma'ayanA, LemischkaIR (2009) Systems biology of stem cell fate and cellular reprogramming. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10 : 672–681 doi:10.1038/nrm2766

52. NachmanI, RamanathanS (2008) HIV-1 positive feedback and lytic fate. Nat Genet 40 : 382–383 doi:10.1038/ng0408-382

53. TaniguchiY, ChoiPJ, LiGW, ChenH, BabuM, et al. (2010) Quantifying E. coli proteome and transcriptome with single-molecule sensitivity in single cells. Science 329 : 533–538 doi:10.1126/science.1188308

54. HollandMJ (2002) Transcript abundance in yeast varies over six orders of magnitude. J Biol Chem 277 : 14363–14366 doi:10.1074/jbc.C200101200

55. VelculescuVE, MaddenSL, ZhangL, LashAE, YuJ, et al. (1999) Analysis of human transcriptomes. Nat Genet 23 : 387–388.

56. SigalA, MiloR, CohenA, Geva-ZatorskyN, KleinY, et al. (2006) Variability and memory of protein levels in human cells. Nature 444 : 643–646 doi:10.1038/nature05316

57. JoplingC, BoueS, BelmonteJCI (2011) Dedifferentiation, transdifferentiation and reprogramming: three routes to regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12 : 79–89 doi:10.1038/nrm3043

58. BrulliardM, LorphelinD, CollignonO, LorphelinW, ThouvenotB, et al. (2007) Nonrandom variations in human cancer ESTs indicate that mRNA heterogeneity increases during carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104 : 7522–7527 doi:10.1073/pnas.0611076104

59. DatsenkoKA, WannerBL (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97 : 6640–6645 doi:10.1073/pnas.120163297

60. OehlerS, EismannER, KrämerH, Müller-HillB (1990) The three operators of the lac operon cooperate in repression. EMBO J 9 : 973–979.

61. PlattT, WeberK, GanemD, MillerJH (1972) Translational restarts: AUG reinitiation of a lac repressor fragment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 69 : 897–901.

62. KleinaLG, MillerJH (1990) Genetic studies of the lac repressor. XIII. Extensive amino acid replacements generated by the use of natural and synthetic nonsense suppressors. J Mol Biol 212 : 295–318 doi:10.1016/0022-2836(90)90126-7

63. ClarkeND, BeamerLJ, GoldbergHR, BerkowerC, PaboCO (1991) The DNA binding arm of lambda repressor: critical contacts from a flexible region. Science 254 : 267–270.

64. SellittiMA, PavcoPA, SteegeDA (1987) lac repressor blocks in vivo transcription of lac control region DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84 : 3199–3203.

65. AboT, InadaT, OgawaK, AibaH (2000) SsrA-mediated tagging and proteolysis of LacI and its role in the regulation of lac operon. EMBO J 19 : 3762–3769.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek PARP-1 Regulates Metastatic Melanoma through Modulation of Vimentin-induced Malignant TransformationČlánek The Genome of : Evolution, Organization, and Expression of the Cyclosporin Biosynthetic Gene ClusterČlánek Distinctive Expansion of Potential Virulence Genes in the Genome of the Oomycete Fish PathogenČlánek USF1 and hSET1A Mediated Epigenetic Modifications Regulate Lineage Differentiation and TranscriptionČlánek Comprehensive High-Resolution Analysis of the Role of an Arabidopsis Gene Family in RNA EditingČlánek Extensive Intra-Kingdom Horizontal Gene Transfer Converging on a Fungal Fructose Transporter Gene

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2013 Číslo 6- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- BMS1 Is Mutated in Aplasia Cutis Congenita

- High Trans-ethnic Replicability of GWAS Results Implies Common Causal Variants

- How Cool Is That: An Interview with Caroline Dean

- Genetic Architecture of Vitamin B and Folate Levels Uncovered Applying Deeply Sequenced Large Datasets

- Juvenile Hormone and Insulin Regulate Trehalose Homeostasis in the Red Flour Beetle,

- Meiosis-Specific Stable Binding of Augmin to Acentrosomal Spindle Poles Promotes Biased Microtubule Assembly in Oocytes

- Environmental Dependence of Genetic Constraint

- H3.3-H4 Tetramer Splitting Events Feature Cell-Type Specific Enhancers

- Network Topologies and Convergent Aetiologies Arising from Deletions and Duplications Observed in Individuals with Autism

- Effectively Identifying eQTLs from Multiple Tissues by Combining Mixed Model and Meta-analytic Approaches

- Altered Splicing of the BIN1 Muscle-Specific Exon in Humans and Dogs with Highly Progressive Centronuclear Myopathy

- The NADPH Metabolic Network Regulates Human Cardiomyopathy and Reductive Stress in

- Negative Regulation of Notch Signaling by Xylose

- A Genome-Wide, Fine-Scale Map of Natural Pigmentation Variation in

- Transcriptome-Wide Mapping of 5-methylcytidine RNA Modifications in Bacteria, Archaea, and Yeast Reveals mC within Archaeal mRNAs

- Multiplexin Promotes Heart but Not Aorta Morphogenesis by Polarized Enhancement of Slit/Robo Activity at the Heart Lumen

- Latent Effects of Hsp90 Mutants Revealed at Reduced Expression Levels

- Impact of Natural Genetic Variation on Gene Expression Dynamics

- DeepSAGE Reveals Genetic Variants Associated with Alternative Polyadenylation and Expression of Coding and Non-coding Transcripts

- The Identification of -acting Factors That Regulate the Expression of via the Osteoarthritis Susceptibility SNP rs143383

- Pervasive Transcription of the Human Genome Produces Thousands of Previously Unidentified Long Intergenic Noncoding RNAs

- The RNA Export Factor, Nxt1, Is Required for Tissue Specific Transcriptional Regulation

- Inferring Demographic History from a Spectrum of Shared Haplotype Lengths

- Histone Acetyl Transferase 1 Is Essential for Mammalian Development, Genome Stability, and the Processing of Newly Synthesized Histones H3 and H4

- PARP-1 Regulates Metastatic Melanoma through Modulation of Vimentin-induced Malignant Transformation

- DNA Methylation Restricts Lineage-specific Functions of Transcription Factor Gata4 during Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation

- The Genome of : Evolution, Organization, and Expression of the Cyclosporin Biosynthetic Gene Cluster

- Distinctive Expansion of Potential Virulence Genes in the Genome of the Oomycete Fish Pathogen

- Deregulation of the Protocadherin Gene Alters Muscle Shapes: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Facioscapulohumeral Dystrophy

- Evidence for Two Different Regulatory Mechanisms Linking Replication and Segregation of Chromosome II

- USF1 and hSET1A Mediated Epigenetic Modifications Regulate Lineage Differentiation and Transcription

- Methylation of Histone H3 on Lysine 79 Associates with a Group of Replication Origins and Helps Limit DNA Replication Once per Cell Cycle

- A Six Months Exercise Intervention Influences the Genome-wide DNA Methylation Pattern in Human Adipose Tissue

- The Gene Desert Mammary Carcinoma Susceptibility Locus Regulates Modifying Mammary Epithelial Cell Differentiation and Proliferation

- Hooked and Cooked: A Fish Killer Genome Exposed

- Distinct Neuroblastoma-associated Alterations of Impair Sympathetic Neuronal Differentiation in Zebrafish Models

- Mutations in Cause Autosomal Recessive Congenital Ichthyosis in Humans

- Integrated Transcriptomic and Epigenomic Analysis of Primary Human Lung Epithelial Cell Differentiation

- RSR-2, the Ortholog of Human Spliceosomal Component SRm300/SRRM2, Regulates Development by Influencing the Transcriptional Machinery

- Comparative Polygenic Analysis of Maximal Ethanol Accumulation Capacity and Tolerance to High Ethanol Levels of Cell Proliferation in Yeast

- SPO11-Independent DNA Repair Foci and Their Role in Meiotic Silencing

- Budding Yeast ATM/ATR Control Meiotic Double-Strand Break (DSB) Levels by Down-Regulating Rec114, an Essential Component of the DSB-machinery

- Comprehensive High-Resolution Analysis of the Role of an Arabidopsis Gene Family in RNA Editing

- Functional Analysis of Neuronal MicroRNAs in Dauer Formation by Combinational Genetics and Neuronal miRISC Immunoprecipitation

- DNA Ligase IV Supports Imprecise End Joining Independently of Its Catalytic Activity

- Extensive Intra-Kingdom Horizontal Gene Transfer Converging on a Fungal Fructose Transporter Gene

- Heritable Change Caused by Transient Transcription Errors

- From Many, One: Genetic Control of Prolificacy during Maize Domestication

- Neuronal Target Identification Requires AHA-1-Mediated Fine-Tuning of Wnt Signaling in

- Loss of Catalytically Inactive Lipid Phosphatase Myotubularin-related Protein 12 Impairs Myotubularin Stability and Promotes Centronuclear Myopathy in Zebrafish

- H-NS Can Facilitate Specific DNA-binding by RNA Polymerase in AT-rich Gene Regulatory Regions

- Prophage Dynamics and Contributions to Pathogenic Traits

- Global DNA Hypermethylation in Down Syndrome Placenta

- Fragile DNA Motifs Trigger Mutagenesis at Distant Chromosomal Loci in

- Disturbed Local Auxin Homeostasis Enhances Cellular Anisotropy and Reveals Alternative Wiring of Auxin-ethylene Crosstalk in Seminal Roots

- Causes and Consequences of Chromatin Variation between Inbred Mice

- Genome-scale Analysis of FNR Reveals Complex Features of Transcription Factor Binding

- Distinct and Atypical Intrinsic and Extrinsic Cell Death Pathways between Photoreceptor Cell Types upon Specific Ablation of in Cone Photoreceptors

- Sex-stratified Genome-wide Association Studies Including 270,000 Individuals Show Sexual Dimorphism in Genetic Loci for Anthropometric Traits

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- BMS1 Is Mutated in Aplasia Cutis Congenita

- Sex-stratified Genome-wide Association Studies Including 270,000 Individuals Show Sexual Dimorphism in Genetic Loci for Anthropometric Traits

- Distinctive Expansion of Potential Virulence Genes in the Genome of the Oomycete Fish Pathogen

- Distinct Neuroblastoma-associated Alterations of Impair Sympathetic Neuronal Differentiation in Zebrafish Models

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy