-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Antibiotic Selection Pressure and Macrolide Resistance in Nasopharyngeal A Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial

Background:

It is widely thought that widespread antibiotic use selects for community antibiotic resistance, though this has been difficult to prove in the setting of a community-randomized clinical trial. In this study, we used a randomized clinical trial design to assess whether macrolide resistance was higher in communities treated with mass azithromycin for trachoma, compared to untreated control communities.Methods and Findings:

In a cluster-randomized trial for trachoma control in Ethiopia, 12 communities were randomized to receive mass azithromycin treatment of children aged 1–10 years at months 0, 3, 6, and 9. Twelve control communities were randomized to receive no antibiotic treatments until the conclusion of the study. Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected from randomly selected children in the treated group at baseline and month 12, and in the control group at month 12. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed on Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated from the swabs using Etest strips. In the treated group, the mean prevalence of azithromycin resistance among all monitored children increased from 3.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.8%–8.9%) at baseline, to 46.9% (37.5%–57.5%) at month 12 (p = 0.003). In control communities, azithromycin resistance was 9.2% (95% CI 6.7%–13.3%) at month 12, significantly lower than the treated group (p<0.0001). Penicillin resistance was identified in 0.8% (95% CI 0%–4.2%) of isolates in the control group at 1 year, and in no isolates in the children-treated group at baseline or 1 year.Conclusions:

This cluster-randomized clinical trial demonstrated that compared to untreated control communities, nasopharyngeal pneumococcal resistance to macrolides was significantly higher in communities randomized to intensive azithromycin treatment. Mass azithromycin distributions were given more frequently than currently recommended by the World Health Organization's trachoma program. Azithromycin use in this setting did not select for resistance to penicillins, which remain the drug of choice for pneumococcal infections.Trial registration:

www.ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00322972

: Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Published in the journal: Antibiotic Selection Pressure and Macrolide Resistance in Nasopharyngeal A Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial. PLoS Med 7(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000377

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000377Summary

Background:

It is widely thought that widespread antibiotic use selects for community antibiotic resistance, though this has been difficult to prove in the setting of a community-randomized clinical trial. In this study, we used a randomized clinical trial design to assess whether macrolide resistance was higher in communities treated with mass azithromycin for trachoma, compared to untreated control communities.Methods and Findings:

In a cluster-randomized trial for trachoma control in Ethiopia, 12 communities were randomized to receive mass azithromycin treatment of children aged 1–10 years at months 0, 3, 6, and 9. Twelve control communities were randomized to receive no antibiotic treatments until the conclusion of the study. Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected from randomly selected children in the treated group at baseline and month 12, and in the control group at month 12. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed on Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated from the swabs using Etest strips. In the treated group, the mean prevalence of azithromycin resistance among all monitored children increased from 3.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.8%–8.9%) at baseline, to 46.9% (37.5%–57.5%) at month 12 (p = 0.003). In control communities, azithromycin resistance was 9.2% (95% CI 6.7%–13.3%) at month 12, significantly lower than the treated group (p<0.0001). Penicillin resistance was identified in 0.8% (95% CI 0%–4.2%) of isolates in the control group at 1 year, and in no isolates in the children-treated group at baseline or 1 year.Conclusions:

This cluster-randomized clinical trial demonstrated that compared to untreated control communities, nasopharyngeal pneumococcal resistance to macrolides was significantly higher in communities randomized to intensive azithromycin treatment. Mass azithromycin distributions were given more frequently than currently recommended by the World Health Organization's trachoma program. Azithromycin use in this setting did not select for resistance to penicillins, which remain the drug of choice for pneumococcal infections.Trial registration:

www.ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00322972

: Please see later in the article for the Editors' SummaryIntroduction

Antibiotic selection pressure is thought to be an important mechanism of selecting for antibiotic resistance in populations [1]. High antibiotic use is correlated with antibiotic resistance in ecological studies [2]–[10], and cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control studies have confirmed these findings [11]–[13]. Although these studies suggest that population-level antibiotic pressure is associated with resistance, these study designs are subject to bias [14],[15]. A randomized controlled trial would provide the strongest evidence for a causal relationship between community antibiotic consumption and resistance.

Trachoma, caused by infection with ocular strains of Chlamydia trachomatis, is the leading infectious cause of blindness worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) endorses mass distributions of antibiotics as one component of an integrated trachoma control strategy. Mass antibiotic treatment clears chlamydial infection in both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, thus reducing the infectious reservoir of disease [16]. Most programs distribute community-wide azithromycin annually, though there is evidence that the most severely affected communities may require more frequent antibiotic distribution for trachoma elimination [17]–[19].

Communities receiving mass azithromycin treatments for trachoma are under intense antibiotic selection pressure. Although chlamydial resistance has not been reported [20],[21], nasopharyngeal pneumococcal resistance has been observed in uncontrolled studies after a single azithromycin treatment, and after repeated annual treatments [22]–[24]. Recently, we performed a population-based, cluster-randomized clinical trial of mass azithromycin for trachoma in Ethiopia [25]. In this study, entire communities were randomized either to intensive azithromycin treatments, or to no treatment, and monitored for trachoma. The trial also provided a unique opportunity to further characterize the community-level effects of antibiotic pressure on resistance. Here, we report nasopharyngeal S. pneumoniae resistance in children before and after frequent mass azithromycin treatments, and compare to untreated control communities.

Methods

The study had approval from the Committee for Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco, Emory University, and the Ethiopian Science and Technology Commission. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and overseen by a Data Safety and Monitoring Committee appointed by the National Institutes of Health-National Eye Institute.

Setting

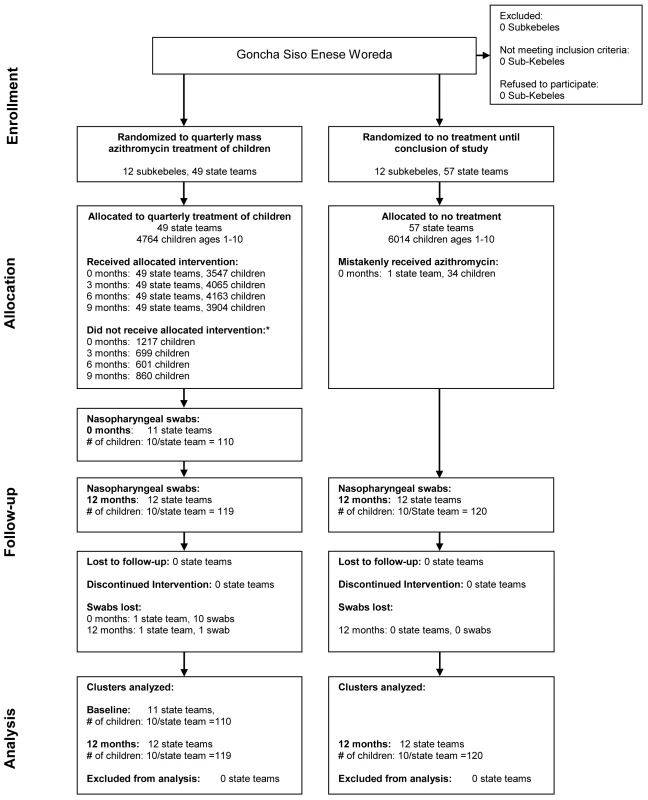

This study consists of a prespecified analysis from a cluster-randomized clinical trial conducted between May 2006 and May 2007 in the Goncha Siso Enese woreda (district) of the Amhara zone of Ethiopia [25]. As part of the clinical trial, 12 subkebeles (administrative units) were randomized to receive quarterly azithromycin treatment of children ages 1–10 y at months 0, 3, 6, and 9. Twelve control subkebeles were randomized to treatment of the entire community at month 12. Subkebeles were randomly chosen from an area of 72 contiguous subkebeles. This area excluded the local town, where the prevalence of trachoma would likely be low [26], and inaccessible communities (defined as those greater than a 3-h walk from the furthest point available to a four-wheel drive vehicle). The socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the included subkebeles were similar. The randomization sequence was generated by Kathryn Ray with the RANDOM and SORT functions in Excel (Version 2003) and concealed until assignment. Participant enrollment and treatment assignment was performed by BA. Each subkebele consisted of approximately four to six state teams (administrative subunits), termed “communities” for this report. All communities from the randomized subkebeles were treated identically to minimize contamination between study arms. One randomly chosen sentinel community was monitored for trachoma (results described elsewhere) [25]. In addition, nasopharyngeal S. pneumoniae antibiotic resistance was assessed in the sentinel communities, and is reported here (Figure 1; Texts S1 and S2).

Fig. 1. Trial profile.

24 subkebeles were randomized to mass treatment of children, or to a control group that received delayed treatment after the conclusion of the study. No sentinel communities were lost to follow-up, and none discontinued the intervention. All communities were included in the analyses at 12 mo. *Reasons for not receiving allocated intervention included absent, moved, or death. Intervention

In the children-treated arm, all children aged 1–10 y were offered one dose of directly observed oral azithromycin (20 mg/kg) every 3 mo for 1 y (at months 0, 3, 6, and 9). Treatments were offered to all children in the subkebele during a single antibiotic campaign lasting several days, and all subkebeles in the study were treated within several weeks of each other. In order to monitor for a secular trend, a delayed treatment arm (control arm) was enrolled at baseline, but not monitored until month 12, after which all individuals aged 1 y and older were offered azithromycin treatment. In both treatment groups, macrolide-allergic or self-reporting pregnant individuals eligible for treatment were offered a 6-wk course of twice-daily 1% tetracycline ointment. Antibiotic coverage was assessed by the antibiotic distributors against the baseline census. For ethical reasons, other than the baseline census, we collected no data from the control group until month 12 of the study.

Outcome Participants

We collected nasopharyngeal samples from ten randomly selected children aged <10 y from each sentinel community in (1) the children-treated arm at baseline and month 12, and (2) the control arm at month 12 only. Swabs were always collected just before a mass azithromycin distribution; therefore, the swabs collected at month 12 in the children-treated arm were collected 3 mo after the most recent treatment. The random sample was redrawn at each visit, so children selected at baseline may or may not have been selected again at month 12. An alternative list of five additionally randomly selected children was available at each visit, to be used if any of the first ten randomly selected children had moved, died, or were traveling during the collection period. Verbal informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians for each child in the local language, Amharic.

Sample Collection

Nasopharyngeal swabs were preserved and transported using skim milk-tryptone-glucose-glycerin medium, as previously described [27]. Samples were kept on ice in the field and then in a −20°C freezer, and subsequently shipped to the United States on ice. Samples arrived frozen, and were placed in a −80°C freezer for up to 6 mo until processed.

Laboratory Studies

S. pneumoniae colonies were identified using selective media (incubated at 35°C in 5% CO2) and optochin and bile solubility testing. S. pneumoniae isolates were evaluated for antimicrobial susceptibilities using Etest strips (bioMérieux - AB Biodisk) placed on Mueller-Hinton agar plates with 5% defibrinated sheep blood, which were incubated at 35°C in 5% CO2 for 20–24 h before determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs). S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 was used for quality control in each run. MIC values were determined from the FDA-approved package insert, using interpretation values for CO2 when provided. The following MICs were used to define resistance: azithromycin (CO2) (≥16 µg/ml), clindamycin (CO2) (>2 µg/ml), benzylpenicillin (≥2 µg/ml), and tetracycline (≥8 µg/ml). All susceptibility testing was performed by a technician masked to study arm and time point.

Genotyping

All azithromycin-resistant isolates underwent genotypic analysis for the mefA gene (M phenotype, drug efflux) and ermB gene (MLSB phenotype, ribosomal target modification). These two genes account for the vast majority of azithromycin resistance [28]–[31]. PCR was performed using oligonucleotide primers to amplify a 348-bp segment containing the mefA gene or a 639-bp segment containing the ermB gene element [32]. Positive controls for each primer pair and a negative control strain (S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619) were included with all runs.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted at the community level. Antibiotic coverage was defined as the proportion of children aged ≤10 y who accepted treatment with azithromycin or tetracycline at each time point, as determined from the baseline census. Note that children aged under 1 y were not eligible for azithromycin treatment, but were included in the coverage calculations since they were monitored for resistance. S. pneumoniae carriage was defined as the proportion of nasopharyngeal samples from which S. pneumoniae was isolated. S. pneumoniae resistance was defined as the proportion of S. pneumoniae isolates that displayed antibiotic resistance. The mean prevalence of S. pneumoniae carriage and S. pneumoniae resistance in children aged <10 y was estimated from the 12 sentinel communities of the children-treated arm at baseline and 1 y, and from the control arm at 1 y. The average proportion of resistant isolates that tested positive for ermB and mefA determinants was calculated, using only those communities with resistant isolates. Bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed (10,000 repetitions). If there were no observations for a proportion, exact binomial one-sided 97.5% CIs were calculated, ignoring clustering. The prespecified primary outcome compared the prevalence of resistance between communities in the treated and control arms at month 12 (Wilcoxon rank sum test). An additional prespecified outcome was the comparison of the prevalence of resistance within communities in the treated arm comparing month 0 to month 12 (Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Several non-prespecified analyses were also conducted. We performed univariate mixed effects logistic regression on the population of children colonized with pneumococcus, with the presence of azithromycin resistance at 12 mo as the response variable, and the treatment arm as the explanatory variable, while clustering at the subkebele level. We calculated the prevalence of antibiotic resistance among all monitored children, regardless of whether pneumococcus was isolated. The intraclass correlation (ICC) for the children-treated arm at 12 mo was calculated using the loneway command in Stata. As an exploratory analysis, an r×c contingency table (2 rows, 12 columns) was constructed plotting the presence or absence of the mefA genetic determinant against sentinel community, and a Fisher exact test was performed to test whether mefA-positive isolates were evenly distributed among communities. An identical analysis was performed for ermB. Intention-to-treat analyses were performed for all statistical tests. The trial had 90% power to detect a 30% difference between the two groups, assuming 24 clusters randomized in a 1∶1 allocation ratio, a S. pneumoniae carriage rate of 80%, a type-I error rate of 0.05, an ICC of 0.05 (determined from a previous study [33]), and a 50% prevalence of azithromycin resistance in the treated group at 12 mo. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata version 10.0.

Results

Characteristics of Treatment Arms

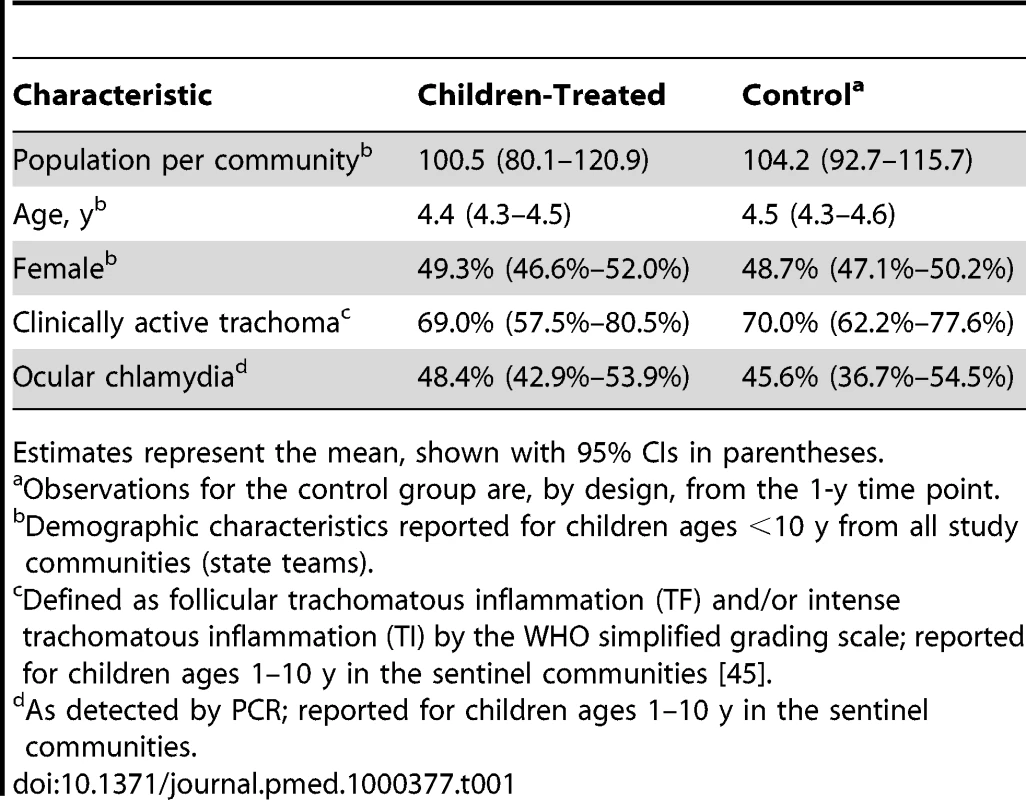

The pretreatment characteristics of the children included in the two study arms were not significantly different (Table 1). Among children ages ≤10 y in the sentinel communities of the treated group, azithromycin coverage at months 0, 3, 6, and 9 was 72.8% (95% CI 67.6%–76.9%), 76.3% (72.2%–80.1%), 80.4% (77.9%–2.9%), and 78.2% (75.2%–80.7%), and tetracycline coverage was 1.5% (0.6%–2.9%), 1.5% (0.6%–2.7%), 2.5% (1.1%–4.5%), and 4.8% (3.5%–6.2%), respectively. In the control arm, 34 children were mistakenly treated in one subkebele at baseline, including 12 children from the sentinel community. This mistakenly treated control sentinel community was retained in the control group for all analyses.

Tab. 1. Pretreatment characteristics of children in the children-treated group and the control group.

Estimates represent the mean, shown with 95% CIs in parentheses. S. pneumoniae Carriage and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Isolates

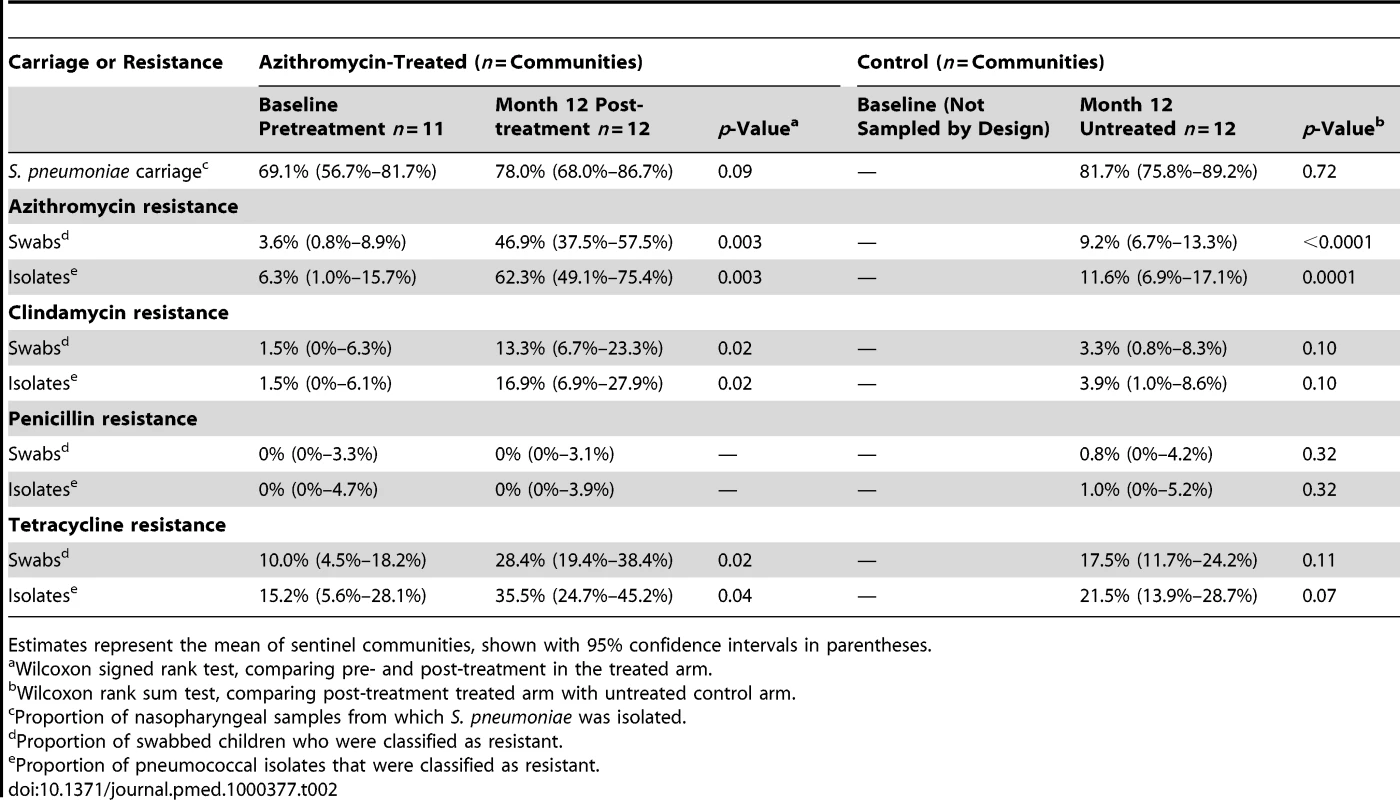

We collected a random sample of ten nasopharyngeal swabs from each sentinel community in the children-treated group at baseline and at month 12, and from each sentinel community in the control group at month 12. In a single community in the treated arm, all baseline samples were destroyed during a flood, and one sample was lost at month 12. Baseline characteristics of the community with missing data were not significantly different from the other sentinel communities (unpublished data). S. pneumoniae was isolated from 76 of 110 nasopharyngeal samples collected from the treated arm before mass azithromycin treatments (mean prevalence of S. pneumoniae carriage 69.1% [95% CI 56.7%–81.7%]), and from 93 of 119 samples 12 mo after the baseline treatment (78.0% [68.0%–86.7%]) (Table 2). Data was collected from the control group at month 12 only; in this untreated group, S. pneumoniae was isolated in 98 of 120 nasopharyngeal samples (81.7% [95% CI 75.8%–89.2%]) (Table 2).

Tab. 2. Nasopharyngeal pneumococcal carriage and resistance in children aged <10 y in the children-treated group (pre- and post-treatment), and the untreated control group.

Estimates represent the mean of sentinel communities, shown with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. The prevalence of antibiotic resistance among children aged <10 y is shown for the population of all swabbed children, and for the population of children from which pneumococcus was isolated (Table 2). Prior to treatment, three of the 11 sentinel communities in the treated group demonstrated azithromycin-resistant S. pneumoniae isolates, and a total of four of the 76 isolates were resistant (mean prevalence among pneumococcal isolates, 6.3% [95% CI 1.0%–15.7%]) (Table 2). After four azithromycin treatments within 1 y, azithromycin resistance was observed in all 12 communities, with 56 of 93 isolates demonstrating resistance (intraclass correlation [ICC] = 0.11 [95% CI 0–0.29]; mean prevalence 62.3% [95% CI 49.1%–75.4%], p = 0.003 compared to baseline, prespecified analysis). In the control group at month 12, nine of 12 communities exhibited azithromycin-resistant strains, with 11 of the 98 isolates testing positive for resistance (mean prevalence 11.6% [95% CI 6.9%–17.1%], p = 0.0001 compared to children-treated group at 1 y, prespecified analysis). Children from communities treated with quarterly mass antibiotics were more likely to be colonized with macrolide-resistant pneumococcus compared to children from untreated communities; OR 13.2 (95% CI 5.5–31.9; non-prespecified analysis).

Significant increases in clindamycin and tetracycline resistance were detected after mass antibiotic distributions (Table 2). In the treated arm, clindamycin resistance increased from one resistant isolate before mass treatment (mean prevalence 1.5% [95% CI 0%–6.1%]) to 16 resistant isolates after four quarterly treatments (mean prevalence 16.9% [6.9%–27.9%], p = 0.02), though this level was not significantly higher than time-matched untreated controls (four resistant isolates, corresponding to 3.9% of isolates [95% CI 1.0%–8.6%], p = 0.10). Before treatment, children carried strains resistant to tetracycline more than any other antibiotic tested, with 11 resistant isolates at the baseline visit in the children-treated arm (15.2% of all isolates [95% CI 5.6%–28.1%]). By month 12, 34 tetracycline-resistant isolates were recovered in the treated group (mean prevalence 35.5% [95% CI 24.7%–45.2%], p = 0.04), though this was not significantly greater than that of time-matched untreated controls (21 resistant isolates; mean prevalence 21.5% [13.9%–28.7%], p = 0.07).

The only antibiotic tested that did not demonstrate the emergence of significant resistance was benzyl-penicillin. Penicillin resistance in the community was rare, with no resistant isolates observed in the children-treated group, either before or after mass antibiotic treatments. In the untreated control group, a single resistant isolate was identified, which corresponded to 1.0% (95% CI 0%–5.2%) of the population.

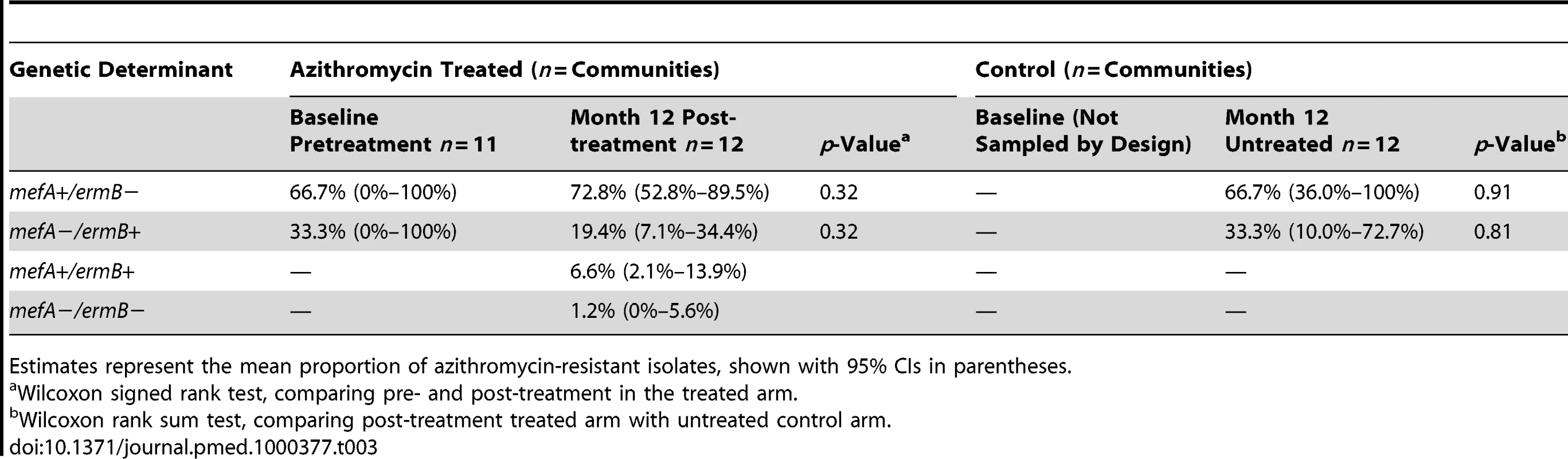

Genotyping of Azithromycin-Resistant Isolates

The average proportion of azithromycin-resistant strains testing positive for the two most common genetic elements encoding resistance is shown in Table 3. All ermB+ isolates, including 17 mefA−/ermB+ isolates and 4 mefA+/ermB+ isolates, also had high-level azithromycin resistance by Etest (MIC>256). Azithromycin resistance was moderate in the 49 mefA+/ermB− isolates (range 24 to >256; median = 192). In comparison, the 196 susceptible isolates had azithromycin MICs ranging from 0.19 to 2 (median = 1).

Tab. 3. Genotypic characteristics of azithromycin-resistant isolates from children aged <10 y old in the treated group (pre- and post-treatment), and the untreated control group.

Estimates represent the mean proportion of azithromycin-resistant isolates, shown with 95% CIs in parentheses. Four azithromycin-resistant isolates were detected at baseline in the children-treated group. The three isolates with mefA resistance at baseline came from two communities, and each of these communities demonstrated only mefA resistant strains at month 12. The ermB genetic determinant was seen in a separate community at baseline; at the 12-mo follow-up, this community demonstrated predominantly ermB resistance, but also a single isolate with both determinants. In seven of the 12 treated communities at 12 mo, all resistant isolates displayed the mefA genetic determinant (p = 0.09 for 2×12 contingency table). In contrast, there was only one community in the treated group at 1 y in which all isolates exhibited the ermB determinant (p = 0.01 for 2×12 contingency table). The prevalence of the mefA determinant in the children-treated group at month 12 did not differ from the prevalence of mefA in the children-treated group at baseline (p = 0.32), or from the control group at month 12 (p = 0.91).

Discussion

This cluster-randomized clinical trial demonstrates that frequent antibiotic use selects for community-level antibiotic resistance. In communities randomized to four azithromycin treatments within 1 y, azithromycin resistance was observed in 47% of all swabbed children and 62% of children colonized with pneumococcus; this was significantly higher than untreated control communities, in which resistance was found in 9% of swabbed children and 12% of children colonized with pneumococcus. Genotype analyses were consistent with the widely accepted theory that antibiotic selection pressure increases community antibiotic resistance by reducing susceptible bacterial strains and allowing clonal expansion of existing resistant strains.

Numerous ecological, analytic, and interventional studies have suggested that population-level antibiotic pressure selects for antibiotic resistance [34]–[36]. However, it has been difficult to rule out the possibility of bias in many of these studies, since antibiotic use in a population is difficult to quantitate, resistance testing is rarely population based, and unmeasured confounders cannot be ruled out. The study design used here had several advantages that helped minimize bias. First, our knowledge of the degree of antibiotic use was extremely accurate. This study was conducted in a rural region in Ethiopia with infrequent background macrolide use. A large, known amount of oral azithromycin was distributed to treated communities, and treatment was directly observed. Second, the study was a randomized controlled trial, which greatly reduces the possibility of an association caused by unmeasured confounders. Third, this study was cluster randomized. Although a previous clinical trial showed antibiotic resistance in individuals using macrolides [36], the cluster randomization of this study allows analysis of community-level antibiotic resistance. Furthermore, the likelihood of contamination from surrounding communities was reduced by randomizing government districts (subkebeles), and treating all communities in the district identically. Finally, bias was reduced by performing population-based monitoring on a random sample of children.

Antibiotic selection pressure is thought to increase community antibiotic resistance by reducing susceptible bacterial strains and shifting the competitive balance in favor of existing resistant strains [1]. The distribution of the mefA and ermB genetic determinants in this study suggests that clonal expansion of resistant strains occurred. For example, the three communities with a specific genetic element at baseline demonstrated a greater prevalence of that same determinant after treatment. In addition, genes encoding resistance were often present as an “all or none” phenomenon in a particular community, suggesting the spread of existing genetic determinants, rather than development of new ones. However, given the wide CIs around the prevalence of mefA and ermB, these results should be interpreted with caution.

Although we did not follow communities after treatments were stopped, there is evidence to suggest that pneumococcal resistance is transient in areas with endemic trachoma. In an uncontrolled study of a single community in Australia, 35% (10/29) of treated children exhibited macrolide resistance 2 mo after a single dose of azithromycin, but only 6% (2/34) did so 6 mo later [22]. Although this community did not receive mass azithromycin—approximately half of children received azithromycin—the study nonetheless suggests that resistance fades after antibiotic selection pressure is removed. In other studies, macrolide resistance was observed in only 5% of children 6 mo after the last of two or three annual mass treatments [23],[24]. These findings were corroborated by a population-based study in Ethiopia, in which the prevalence of macrolide resistance decreased dramatically after cessation of mass azithromycin treatments—from 77% after the last of six biannual mass treatments, to 21% by 2 y after the final treatment [33].

In this community-randomized clinical trial, quarterly azithromycin treatment of children was clearly effective in reducing ocular chlamydia [25]. Here, however, we report that more frequent mass treatments also select for pneumococcal resistance. It is notable that even the periodic treatments of this study were sufficient to select for resistant strains, at least in this rural Ethiopian setting with presumably efficient interhost transmission. Fortunately, any negative impact is tempered by several factors. First, resistance to penicillins, which would serve as first-line therapy for S. pneumoniae infections and are widely available and used in the study area, was not detected. Second, macrolides are rarely used in the region, based upon a survey of pharmacies (BA, unpublished data). Third, azithromycin resistance appears to be transient in similar communities once mass treatments are stopped [22],[33]. Fourth, the clinical significance of azithromycin resistance is unclear. There have been no reports of increased invasive pneumococcal disease or increased mortality in areas treated with mass azithromycin. To the contrary, a concomitant trial found that mass azithromycin distributions may even reduce childhood mortality [37]. Finally, in this study, antibiotics were distributed every 3 mo—much more frequently than the annual treatments recommended by WHO guidelines. This study is quite different from previous studies, which have monitored pneumococcal resistance after much lower levels of antibiotic selection pressure. In particular, this study cannot be extrapolated to the case of repeated annual mass treatments, for which pneumococcal macrolide resistance has never been shown to exceed 5% by 6 mo after treatment [23],[24]. Likewise, this study cannot be generalized to the case of a single mass azithromycin distribution, for which other studies have found at most only a single isolate of pneumococcal macrolide resistance between 6–12 mo after a community-wide treatment [38],[39].

The beneficial effects of mass azithromycin treatments for trachoma are very clear. Mass azithromycin distributions for trachoma have been tremendously successful in reducing the prevalence of ocular strains of chlamydia, and may even result in the elimination of infection in some areas [18],[40]–[42]. These activities will be instrumental in reducing blindness due to trachoma. The adverse effects of mass treatments are much less certain. Although we show considerable nasopharyngeal macrolide resistance following frequent mass azithromycin in this study, there is good reason to think that the clinical impact of resistance is minimal, as discussed above. We believe that the known benefits of mass azithromycin treatments clearly outweigh any uncertain adverse effects, and that trachoma programs should continue to distribute mass azithromycin treatments.

This study has several limitations. We did not collect baseline nasopharyngeal samples in the control group, since we did not want to mislead participants, who might have construed swabbing as treatment. Note, however, that because treatment group was randomly assigned, baseline measurements are not necessary for between-group comparisons. We did not collect cultures from other sites to monitor for invasive pneumococcal diseases such as meningitis, pneumonia, or bacteremia. We do not have follow-up data for these communities. We have not performed a genetic analysis of pneumococcal strains, though we do plan on completing such an analysis in the future. This study was performed in Ethiopian communities with very high rates of pneumococcal carriage. Although this rate of pneumococcal carriage is the norm in much of Africa, it is higher than that seen in most industrialized countries [43],[44]. However, our findings are consistent with many studies conducted in developed countries [2]–[12], which suggests that the central finding of this study—that community level S. pneumoniae resistance increases with antibiotic use—is not specific to Ethiopia, but is generalizable to other settings.

This study demonstrates the importance of antibiotic selection pressure for community antibiotic resistance. Although we found a considerable amount of pneumococcal macrolide resistance in children treated with mass azithromycin treatments every 3 mo, this finding has no bearing on current trachoma control activities, which use less frequent antibiotic distributions, and which likely select for far less pneumococcal resistance [22]–[24],[38],[39]. Our findings nonetheless highlight the importance of continued monitoring for the secondary effects of mass oral antibiotic distributions.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. LipsitchM

SamoreMH

2002 Antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance: a population perspective. Emerg Infect Dis 8 347 354

2. GoossensH

FerechM

Vander SticheleR

ElseviersM

2005 Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet 365 579 587

3. BronzwaerSL

CarsO

BuchholzU

MolstadS

GoettschW

2002 A European study on the relationship between antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance. Emerg Infect Dis 8 278 282

4. Van EldereJ

MeraRM

MillerLA

PoupardJA

Amrine-MadsenH

2007 Risk factors for development of multiple-class resistance to Streptococcus pneumoniae Strains in Belgium over a 10-year period: antimicrobial consumption, population density, and geographic location. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51 3491 3497

5. MeraRM

MillerLA

WhiteA

2006 Antibacterial use and Streptococcus pneumoniae penicillin resistance: a temporal relationship model. Microb Drug Resist 12 158 163

6. ArasonVA

SigurdssonJA

ErlendsdottirH

GudmundssonS

KristinssonKG

2006 The role of antimicrobial use in the epidemiology of resistant pneumococci: a 10-year follow up. Microb Drug Resist 12 169 176

7. ChenDK

McGeerA

de AzavedoJC

LowDE

1999 Decreased susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae to fluoroquinolones in Canada. Canadian Bacterial Surveillance Network. N Engl J Med 341 233 239

8. PihlajamakiM

KotilainenP

KaurilaT

KlaukkaT

PalvaE

2001 Macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae and use of antimicrobial agents. Clin Infect Dis 33 483 488

9. GranizoJJ

AguilarL

CasalJ

Dal-ReR

BaqueroF

2000 Streptococcus pyogenes resistance to erythromycin in relation to macrolide consumption in Spain (1986-1997). J Antimicrob Chemother 46 959 964

10. BergmanM

HuikkoS

PihlajamakiM

LaippalaP

PalvaE

2004 Effect of macrolide consumption on erythromycin resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes in Finland in 1997-2001. Clin Infect Dis 38 1251 1256

11. ArasonVA

KristinssonKG

SigurdssonJA

StefansdottirG

MolstadS

1996 Do antimicrobials increase the carriage rate of penicillin resistant pneumococci in children? Cross sectional prevalence study. BMJ 313 387 391

12. VanderkooiOG

LowDE

GreenK

PowisJE

McGeerA

2005 Predicting antimicrobial resistance in invasive pneumococcal infections. Clin Infect Dis 40 1288 1297

13. MetlayJP

FishmanNO

JoffeMM

KallanMJ

ChittamsJL

2006 Macrolide resistance in adults with bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia. Emerg Infect Dis 12 1223 1230

14. CarmeliY

SamoreMH

HuskinsC

1999 The association between antecedent vancomycin treatment and hospital-acquired vancomycin-resistant enterococci: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 159 2461 2468

15. BolonMK

WrightSB

GoldHS

CarmeliY

2004 The magnitude of the association between fluoroquinolone use and quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae may be lower than previously reported. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48 1934 1940

16. WrightHR

TurnerA

TaylorHR

2008 Trachoma. Lancet 371 1945 1954

17. MeleseM

ChidambaramJD

AlemayehuW

LeeDC

YiEH

2004 Feasibility of eliminating ocular Chlamydia trachomatis with repeat mass antibiotic treatments. JAMA 292 721 725

18. MeleseM

AlemayehuW

LakewT

YiE

HouseJ

2008 Comparison of annual and biannual mass antibiotic administration for elimination of infectious trachoma. JAMA 299 778 784

19. LietmanT

PorcoT

DawsonC

BlowerS

1999 Global elimination of trachoma: how frequently should we administer mass chemotherapy? Nat Med 5 572 576

20. HongKC

SchachterJ

MoncadaJ

ZhouZ

HouseJ

2009 Lack of macrolide resistance in Chlamydia trachomatis after mass azithromycin distributions for trachoma. Emerg Infect Dis 15 1088 1090

21. SolomonAW

MohammedZ

MassaePA

ShaoJF

FosterA

2005 Impact of mass distribution of azithromycin on the antibiotic susceptibilities of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49 4804 4806

22. LeachAJ

Shelby-JamesTM

MayoM

GrattenM

LamingAC

1997 A prospective study of the impact of community-based azithromycin treatment of trachoma on carriage and resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis 24 356 362

23. GaynorBD

ChidambaramJD

CevallosV

MiaoY

MillerK

2005 Topical ocular antibiotics induce bacterial resistance at extraocular sites. Br J Ophthalmol 89 1097 1099

24. FryAM

JhaHC

LietmanTM

ChaudharyJS

BhattaRC

2002 Adverse and beneficial secondary effects of mass treatment with azithromycin to eliminate blindness due to trachoma in Nepal. Clin Infect Dis 35 395 402

25. HouseJI

AyeleB

PorcoTC

ZhouZ

HongKC

2009 Assessment of herd protection against trachoma due to repeated mass antibiotic distributions: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 373 1111 1118

26. ZerihunN

1997 Trachoma in Jimma zone, south western Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health 2 1115 1121

27. O'BrienKL

BronsdonMA

DaganR

YagupskyP

JancoJ

2001 Evaluation of a medium (STGG) for transport and optimal recovery of Streptococcus pneumoniae from nasopharyngeal secretions collected during field studies. J Clin Microbiol 39 1021 1024

28. FarrellDJ

MorrisseyI

BakkerS

FelminghamD

2002 Molecular characterization of macrolide resistance mechanisms among Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes isolated from the PROTEKT 1999–2000 study. J Antimicrob Chemother 50 Suppl S1 39 47

29. FarrellDJ

MorrisseyI

BakkerS

MorrisL

BuckridgeS

2004 Molecular epidemiology of multiresistant Streptococcus pneumoniae with both erm(B) - and mef(A)-mediated macrolide resistance. J Clin Microbiol 42 764 768

30. LeclercqR

CourvalinP

1991 Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 35 1267 1272

31. SutcliffeJ

Tait-KamradtA

WondrackL

1996 Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes resistant to macrolides but sensitive to clindamycin: a common resistance pattern mediated by an efflux system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 40 1817 1824

32. SutcliffeJ

GrebeT

Tait-KamradtA

WondrackL

1996 Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 40 2562 2566

33. HaugS

LakewT

HabtemariamG

AlemayehuW

CevallosV

2010 The decline of pneumococcal resistance after cessation of mass antibiotic distributions for trachoma. Clin Infect Dis 51 571 574

34. SeppalaH

KlaukkaT

Vuopio-VarkilaJ

MuotialaA

HeleniusH

1997 The effect of changes in the consumption of macrolide antibiotics on erythromycin resistance in group A streptococci in Finland. Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. N Engl J Med 337 441 446

35. GuillemotD

VaronE

BernedeC

WeberP

HenrietL

2005 Reduction of antibiotic use in the community reduces the rate of colonization with penicillin G-nonsusceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis 41 930 938

36. Malhotra-KumarS

LammensC

CoenenS

Van HerckK

GoossensH

2007 Effect of azithromycin and clarithromycin therapy on pharyngeal carriage of macrolide-resistant streptococci in healthy volunteers: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet 369 482 490

37. PorcoTC

GebreT

AyeleB

HouseJ

KeenanJ

2009 Effect of mass distribution of azithromycin for trachoma control on overall mortality in Ethiopian children: a randomized trial. JAMA 302 962 968

38. GaynorBD

HolbrookKA

WhitcherJP

HolmSO

JhaHC

2003 Community treatment with azithromycin for trachoma is not associated with antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae at 1 year. Br J Ophthalmol 87 147 148

39. BattSL

CharalambousBM

SolomonAW

KnirschC

MassaePA

2003 Impact of azithromycin administration for trachoma control on the carriage of antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47 2765 2769

40. SolomonAW

HollandMJ

AlexanderND

MassaePA

AguirreA

2004 Mass treatment with single-dose azithromycin for trachoma. N Engl J Med 351 1962 1971

41. WestSK

MunozB

MkochaH

GaydosC

QuinnT

2007 Trachoma and ocular Chlamydia trachomatis were not eliminated three years after two rounds of mass treatment in a trachoma hyperendemic village. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48 1492 1497

42. BiebesheimerJB

HouseJ

HongKC

LakewT

AlemayehuW

2009 Complete local elimination of infectious trachoma from severely affected communities after six biannual mass azithromycin distributions. Ophthalmology 116 2047 2050

43. FeikinDR

DowellSF

NwanyanwuOC

KlugmanKP

KazembePN

2000 Increased carriage of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in Malawian children after treatment for malaria with sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine. J Infect Dis 181 1501 1505

44. HillPC

AkisanyaA

SankarehK

CheungYB

SaakaM

2006 Nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Gambian villagers. Clin Infect Dis 43 673 679

45. ThyleforsB

DawsonCR

JonesBR

WestSK

TaylorHR

1987 A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ 65 477 483

Štítky

Interné lekárstvo

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2010 Číslo 12- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Intermitentní hladovění v prevenci a léčbě chorob

- Statinová intolerance

- Co dělat při intoleranci statinů?

- Monoklonální protilátky v léčbě hyperlipidemií

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Clinical Features and Serum Biomarkers in HIV Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome after Cryptococcal Meningitis: A Prospective Cohort Study

- Scaling Up the 2010 World Health Organization HIV Treatment Guidelines in Resource-Limited Settings: A Model-Based Analysis

- Toward a Consensus on Guiding Principles for Health Systems Strengthening

- Association of Secondhand Smoke Exposure with Pediatric Invasive Bacterial Disease and Bacterial Carriage: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- The Health Crisis of Tuberculosis in Prisons Extends beyond the Prison Walls

- A Longitudinal Study of Medicaid Coverage for Tobacco Dependence Treatments in Massachusetts and Associated Decreases in Hospitalizations for Cardiovascular Disease

- Participatory Epidemiology: Use of Mobile Phones for Community-Based Health Reporting

- Nuclear Receptor Expression Defines a Set of Prognostic Biomarkers for Lung Cancer

- Antibiotic Selection Pressure and Macrolide Resistance in Nasopharyngeal A Cluster-Randomized Clinical Trial

- Clinical Benefits, Costs, and Cost-Effectiveness of Neonatal Intensive Care in Mexico

- Tuberculosis Incidence in Prisons: A Systematic Review

- PLOS Medicine

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Clinical Features and Serum Biomarkers in HIV Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome after Cryptococcal Meningitis: A Prospective Cohort Study

- Participatory Epidemiology: Use of Mobile Phones for Community-Based Health Reporting

- Clinical Benefits, Costs, and Cost-Effectiveness of Neonatal Intensive Care in Mexico

- Scaling Up the 2010 World Health Organization HIV Treatment Guidelines in Resource-Limited Settings: A Model-Based Analysis

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy