Development of a questionnaire for a patient-reported outcome after nasal reconstruction

Authors:

Dvořák- Z. 1 3; Křenková V. 2; Hudcová L. 4; Knoz M. 1,2; Kubát M. 1,2; Pink R. 3,5

Authors‘ workplace:

Department of Plastic and Aesthetic Surgery, St. Anne`s University Hospital, Brno, Czech Republic

1; Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

2; Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University Hospital, Olomouc, Czech Republic

3; Faculty of Economics and Administration, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

4; Faculty of Medicine, Palacky University, Olomouc, Czech Republic

5

Published in:

ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 64, 1, 2022, pp. 24-30

doi:

https://doi.org/10.48095/ccachp202224

Introduction

With the progress in plastic surgery and the introduction of more complicated modern methods, the demands on a better esthetic outcome are increasing. A satisfying esthetic outcome, especially on the face, means an obvious increase in the quality of patient’s life, because he/she is no longer excluded from the society and restrained from his/her social contacts. An esthetically pleasing result is the main goal for all face injuries reconstructions as the face has a fundamental function in social life. [1].

The modern concept of nasal reconstruction is constantly evolving. The oldest rule is the selection of the forehead flap as the best donor for the reconstruction of nasal skin cover [2]. At the end of the 20th century, the greatest innovators in nasal reconstruction were American surgeons Millard, Burget, Baker and Menick [3]. They promoted a transition from a two-phase use of the forehead flap to a three-phase use in nasal reconstruction. If more than 50% of the subunit of the nose is missing, it is better to replace the whole subunit. The complex reconstruction of the supporting skeleton is an essential part of the nasal reconstruction plan. For all previous principles to be met, it is essential to build everything on the well-vascularized intranasal lining [4].

With modern nasal reconstruction concept, it is possible to achieve better functional results that are more stable over time and have a better esthetical outcome than previous methods. However, a more sophisticated technique of reconstruction is associated with an increase in patient’s discomfort during his/her treatment [5]. As the number of surgeries required for successful reconstruction are increasing, the whole treatment is prolonged. It takes up to several months to finish the whole procedure, see illustrative photos (Fig. 1–4). As the result of this trend, patients are repeatedly hospitalized and exposed to pain during various stages of reconstruction [6].

It may be assumed that all the above mentioned can negatively affect patients’ social ties and worsen their mental state during and after the treatment [7].

The important question remains – whether the quality of patient life really increases with reconstruction and whether difficulties of the treatment do not exceed its benefits. For this purpose, authors searched for an already developed suitable tool – patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) [8], which would help to obtain required information. The FACE-Q questionnaires were developed by the team of Dr. Stephen B. Baker M.D., D.D.S. from Georgetown University hospital to obtain patient-reported outcomes after face surgeries [7].

Even though the FACE-Q questionnaires meet standards and recommendations for PROMs [9–11] and there are specific questions on nasal reconstruction, the authors came to the conclusion that FACE-Q questionnaires are of limited use, mainly due to the questions aimed more at reconstructions done for an esthetical indication. Its questions do not cover the modern nasal reconstructions done for other indications (injuries and defects), e.g. higher number of surgeries, prolonged time of reconstruction and living with nose defect before and during the treatment [12]. Copyright do not allow the authors to modify the FACE-Q questionnaires. Another obstacle to use FACE-Q was absence of Czech translation at present.

The main goal of the project was to objectify the subjective patient’s point of view on nose reconstruction, prove the increased quality of life and find out whether it actually increased after the reconstruction. Furthermore, the aim was to obtain complex patient feedback on the whole procedure and outcome of the treatment, to find out difficulties that have crucial impact on patient overall satisfaction with treatment by means of structured and specific questions, which could result in reasonable improvement of provided healthcare. A new questionnaire was developed for this purpose.

Materials and methods

The development and assessment of the questionnaire were divided into three main phases. In the first phase, the first version of the questionnaire was designed and sent to five selected patients from the whole group. In the second phase, the data from the first survey was analyzed. It resulted in the development of the second version of questionnaire, which was sent to the whole group of respondents. In the third phase, collected data was analyzed and the third final version of questionnaire was developed.

Phase 1

Five patients who underwent modern nasal reconstruction in the years 2016 – 2020 were selected to participate in the first phase of questionnaire development. They were supposed to be able to fill in the questionnaire by themselves. At least two males and two females were included in the study to cover both genders equally. According to their achieved level of education, at least one person with university degree, one with secondary education and one with primary education were selected. It was decided to include at least two patients over the age of 70. The criteria were chosen to demonstrate the comprehensibility of the questionnaire for patients of different ages, from different social groups and of different cognitive abilities. The first group consisted of two males and three females who achieved various education levels. The average age of the responders was 70 years. The youngest was 57 years old and the oldest 74 years old.

In the first phase, a prototype questionnaire was created to find out the required information. The selection of questions was based on the experience of surgeon’s targeted interview with patients who underwent reconstruction, with simultaneous reviews of related literature [13]. A psychologist reviewed the questionnaire. Based on her expert opinion, some questions were added, modified or deleted. In cooperation with a statistician, the questionnaire was structured into six categories (A–F) and adjusted according to a planned mathematical analysis and interpretation.

The pilot questionnaire was sent to five selected responders who were asked besides its completing to provide more extensive feedback on its length, complexity and comprehensibility.

Phase 2

The questionnaire created in the first phase was further modified on the basis of respondents’ feedbacks and statistical analysis of the results. The second version of the questionnaire was developed. Thirty-nine patients who met the given criteria were selected for the second phase of the study; they underwent nose reconstruction using modern methods at the Department of Plastic and Aesthetic Surgery in Brno in the years 2016–2020 and were able to fill in the questionnaire by themselves. Due to the average responder’s age of 69 years, it was decided to send the questionnaire by post in paper form with a return envelope instead of an electronic questionnaire.

To increase the number of returned completed questionnaires, the cover letter was attached and two appeals to its responders were made after 14 days by e-mail and phone call. At the request of some responders, the questionnaire was resent. After the next 14 days, the collection of filled in questionnaires was completed. The total time for data collection was 4 weeks [14].

Phase 3

Collected data was statistically analyzed and interpreted. The second version of the questionnaire was revised which led to the development of the third and final version of the questionnaire (Fig. 5,6).

Structure of the questionnaire

The questionnaire is structured into six categories (A–F): Category A contains basic demographic data, indication for surgery, depth and extent of the face defect, time between surgeries, number of surgeries performed and complications during the treatment. It helps to define the group of responders. Categories B–E are focused on specific aspects of the treatment: B – satisfaction with the esthetic outcome, C – functional outcome and stability of reconstructed nose, D – satisfaction with medical treatment, E – social and psychological impacts. Category F represents overall satisfaction with the treatment.

Most questions use a five-point rating scale with the best possible score "1" and the worst possible score "5". In each category, the numerical rating scale has been redesigned into verbal evaluation for better comprehensibility. For example, number "1" is replaced by "very nice" and number “5” is replaced by "very ugly" in category B – satisfaction with the aesthetic result. In some specific questions, a choice of two options or an open answer is used.

Statistical analysis

Within the statistical analysis, several regression models were created and tested (see below) and the parameters of the model were estimated using the least square method (estimating the relationship between a single dependent variable and several other independent, explanatory variables). Separate models were created for the given categories B–E.

Category B–E questions represented explanatory variables. For the purposes of the analysis, questions in category F that determine overall satisfaction were defined from more than one perspective. By compiling the average scale from the individual F-category questions, the variable F was created, which reflects the impact on the patient's quality of life, whether the patient perceives the operation as successful or unsuccessful and whether he would undergo it again with full knowledge of what he/she can expect. Variable F was then used in the models as a dependent variable to examine the relationship between patient satisfaction (explained variable F) and independent explanatory variables (the questions in categories B–E).

The data was analyzed and regression analysis was performed with Gretl statistical software. Gretl is an open-source statistical package. The name is an acronym for Gnu Regression, Econometrics and Time-series Library. It is free, open-source software. It could be redistributed and/or modified under the terms of the General Public License (GPL) as published by the Free Software Foundation.

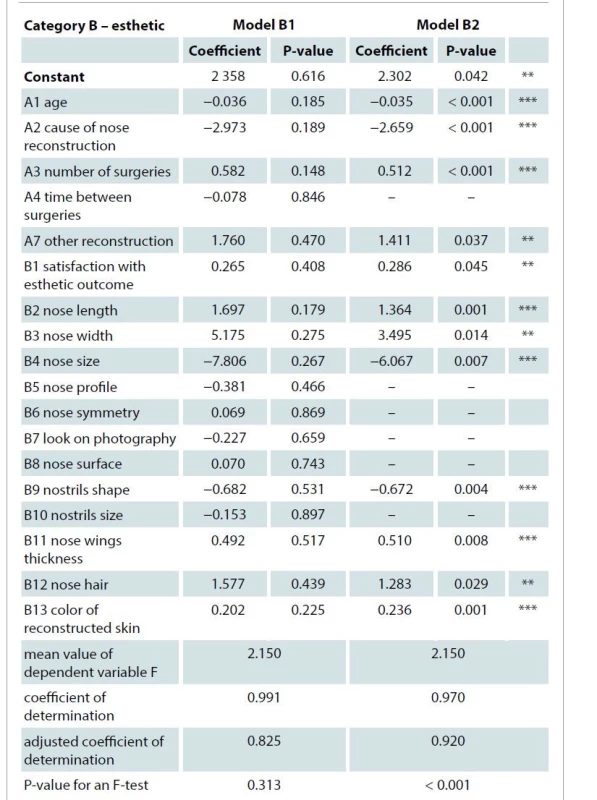

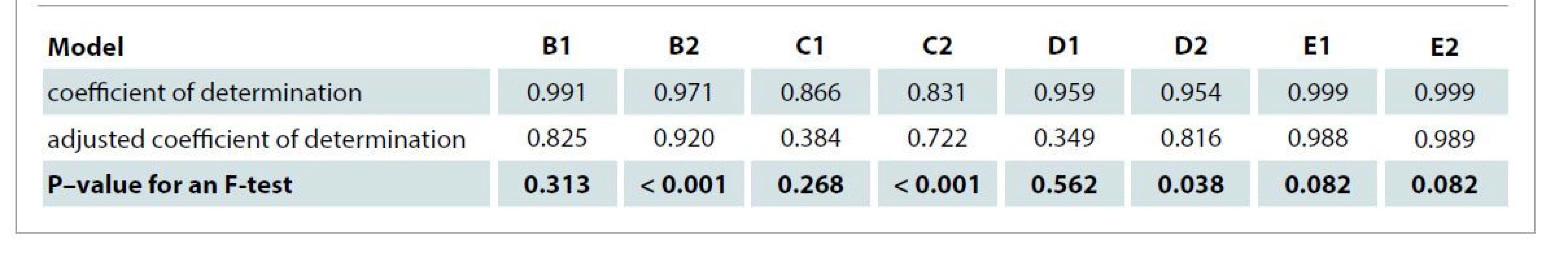

A base model – “model 1” (models B1, C1, D1 and E1) was created for each category of the questionnaire. Each model consisted of individual questions in given category, the explanatory variables, and the dependent variable – an arithmetic average of category F. For example, model B1 was designed to clarify how a patient's satisfaction with the aesthetic result affects his overall satisfaction with the reconstruction, and to include all the questions from the second version of the questionnaire. Insignificant variables (questions that did not have a statistically significant effect on the overall satisfaction) were gradually taken from each initial model until the best model was reached – model 2. Models B2, C2, D2, and E2 were created and compared with the initial models by using the adjusted coefficient of determination (model B1 with B2, C1 with C2, etc. were compared) (Tab. 1). Each final model (model 2) contained only statistically significant questions for which the P-value, generally indicating the lowest possible level of significance, at which the null hypothesis of the insignificance of the variable in the model can be rejected based on the implementation of test statistics, was based on at least 10% and higher (P ≤ 0.1). Based on individual tests of the significance of a given variable in the specific model, the already mentioned statistically significant questions, which can be said to affect overall satisfaction, remained in the model. For example, the statistical processing of category B was given here (Tab. 1).

Discussion

In the third phase of the questionnaire development, several models of mathematical analysis were tested. The models were designed for each category B–E individually. For categories B, C and D, initial models (B1–D1) needed to be further modified due to insufficient significance of particular variables – questions in the model, which reflected the high P-values of these variables, and due to the overall insignificance of the model, which described low coefficients of determination and F-tests of individual models. Questions within these categories providing feedback on patient satisfaction with esthetics, functionality and stability of reconstructed nose and satisfaction with medical treatment did not show a significant effect on the resulting change in F, or overall satisfaction, in these models. It was different for category E, in which the first model came out with a high value of the coefficient of determination (0.999) and the overall F-test (0.082), which proved the overall significance of the model. The individual variables then turned out to be statistically significant in all cases (P ≤ 0.1).

For initial models B1, C1 and D1, statistically insignificant variables (questions) were gradually removed according to their significance level – P-value (from the highest P-value downwards, P-value ≥ 0.1) and only those questions showing satisfactory significance in the model remained (P-value < 0.1). For all categories, this gradual removal of insignificant variables resulted in final adjusted models (B2–D2) that can be described as the best according to the value of the adjusted coefficient of determination, and only questions that have a statistically demonstrable effect on overall satisfaction were left in the final models of the given categories.

The coefficient of determination, inside the range of <0,1>, expresses the percentage of variability, which is expressed by the model. It provides a measure of how well the observed outcomes are replicated by the model. In other words, it can be interpreted as a measure of a fit of a model. A coefficient of determination of 1 indicates that the regression predictions perfectly fit the data. In our survey, the coefficient of determination was high (> 0.9 for all models B, D, E) and (> 0.8 for models C) which means that each model explains the resulting values of F (overall satisfaction) very well.

According to the interpretation of the results of the final models’ analysis, where only statistically significant questions were included, psychological and social impacts of the treatment can be included among the most important factors influencing the overall patient satisfaction. The model (E2) itself was significant at a significance level of 10%. The satisfaction with treatment (D2) model was statistically significant at a significance level of 5%. The models focused on the esthetics (B2) and functionality and stability of the reconstructed unit (C2) then turned out to be significant at a significance level of 1%.

A considerable limitation of the questionnaire analysis is the small number of observations, which did not allow performing regression analysis on a model in which all questions from the entire questionnaire would appear as independent variables. As a general rule, the number of observations should be greater than the number of variables, so an analysis of a single model in which all questions in the whole questionnaire would be independent variables could not be performed. For this reason, an alternative procedure was chosen where separate models were created according to the given categories of the questionnaire. It is therefore necessary to mention that the resulting estimates always relate only to the category and not to the questionnaire as a whole.

The main benefit of the statistical analysis was to identify the questions to which the expert should pay particular attention, since they provide relevant feedback – the way the responder answers these questions has effect on his/her overall satisfaction. Obtaining this information also led to the development of the third shorter version of the questionnaire with only significant questions. A shorter questionnaire with well-chosen questions can positively affect the quality of the feedback and increase the number of patients willing to provide feedback this way [14].

When interpreting the results, it is important to consider the size of the group of patients on whom the questionnaire was tested. The resulting values can be hereby significantly affected. The authors consider the main advantages of the questionnaire to be its simplicity and the content of the questionnaire – selected relevant questions that fit to the modern concept of nasal reconstruction.

In the future, the authors can see the potential of the questionnaire to find other connections between particular aspects of treatment with the overall satisfaction, which could contribute to an increase in the quality of care. The current limitation of the questionnaire is the need to verify its final version by more clinical testing, which means further cooperation together with statistics to interpret the data. The questionnaire is now provided to the professional public as an instrument to obtain patient’s feedback after nose reconstruction, more or less this questionnaire is the only one of its kind. By obtaining further observations and testing the questionnaire, it will be possible to further innovate the questionnaire as a quality tool for PROMs.

Conclusion

The final questionnaire provides information about the overall satisfaction of patients after the treatment, their satisfaction with particular aspects of the whole procedure and shows connection between these two. The questionnaire allows to identify those specific difficulties that could have a crucial impact on patient overall satisfaction and thus provides sophisticated feedback on the treatment from patient’s point of view, which can lead to the improvement of the quality of provided healthcare and increase in the quality of patient’s life.

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors declare that this study has received no financial support. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Role of authors: Z. Dvořák, V. Křenková and L. Hudcová conducted the literature search, designed the flowchart and analyzed the collected data.

Z. Dvořák and V. Křenková wrote the manuscript with the input from all authors.

M. Knoz, M. Kubát and R. Pink conceived the study and revised it critically for important intellectual content.

All the authors approved the version to be published.

Vlasta Křenková

Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University,

Kamenice 5

625 00 Brno

Czech Republic

e-mail: vlasta.krenkova@gmail.com

Submitted: 7. 11. 2021

Accepted: 30. 1. 2022

Sources

1. Mureau MAM., Moolenburgh SE., Levendag PC., et al. Aesthetic and functional outcome following nasal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007, 120(5): 1217–1227.

2. Dvořák Z., Novák P., Výška T., et al. Reconstruction of defects with forehead flap. Acta Chir Plast. 2015, 57(3–4): 46–48.

3. Dvořák Z., Heroutová M., Sukop A., et al. Příčina, diagnostika, klasifikace defektů nosu a historie rekonstrukce nosu. Otorinolaryngol Foniatr. 2018, 67(4): 95–99.

4. Dvořák Z., Kubek T., Pink R., et al. Moderní principy rekonstrukce nosu. Otorinolaryngol Foniatr. 2018, 67(4): 100–106.

5. Menick FJ. A 10-year experience in nasal reconstruction with the three-stage forehead flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002, 109(6): 1839–1855; discussion 1856–1861.

6. Baker SR. Principles of nasal reconstruction. Springer 2011.

7. Klassen AF., Cano SJ., Schwitzer JA., et al. FACE-Q scales for health-related quality of life, early life impact, satisfaction with outcomes, and decision to have treatment: development and validation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015, 135(2): 375–386.

8. Weldring T., Smith SMS. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Health Serv Insights. 2013, 6 : 61–68.

9. Aaronson N., Alonso J., Burnam A., et al. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002, 11(3): 193–205.

10. Lasch KE., Marquis P., Vigneux M., et al. PRO development: rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Qual Life Res. 2010, 19(8): 1087–1096.

11. Patrick DL., Burke LB., Gwaltney CJ., et al. Content validity – establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1 – eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011, 14(8): 967–977.

12. Schwitzer JA., Sher SR., Fan KL., et al. Assessing patient-reported satisfaction with appearance and quality of life following rhinoplasty using the FACE-Q appraisal scales. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015, 135(5): 830e–837e.

13. Rothrock NE., Kaiser KA., Cella D. Developing a valid patient-reported outcome measure. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011, 90(5): 737–742.

14. Edwards P., Roberts I., Clarke M., et al. Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: systematic review. BMJ. 2002, 324(7347): 1183.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine TraumatologyArticle was published in

Acta chirurgiae plasticae

2022 Issue 1

- Possibilities of Using Metamizole in the Treatment of Acute Primary Headaches

- Metamizole vs. Tramadol in Postoperative Analgesia

- Spasmolytic Effect of Metamizole

- Metamizole at a Glance and in Practice – Effective Non-Opioid Analgesic for All Ages

- Safety and Tolerance of Metamizole in Postoperative Analgesia in Children

-

All articles in this issue

- Depression and anxiety disorders in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome after surgery – a case control study

- Recurrence of breast ptosis after mastopexy – a prospective pilot study

- Development of a questionnaire for a patient-reported outcome after nasal reconstruction

- Breast reconstruction with autologous abdomen-based free flap with prior abdominal liposuction – a case-based review

- Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap on extremity defects – case series

- Emergency evacuation low-pressure suction for the management of extravasation injuries – a case report

- Editorial

- Efficacy of pedicled anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of regional defects – a record analysis

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- About the journal

Most read in this issue

- Superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap on extremity defects – case series

- Efficacy of pedicled anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction of regional defects – a record analysis

- Recurrence of breast ptosis after mastopexy – a prospective pilot study

- Breast reconstruction with autologous abdomen-based free flap with prior abdominal liposuction – a case-based review