-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Long-term donor-site morbidity after thumb reconstruction with twisted-toe technique

Authors: Tomáš Kempný 1; Olga Košková 2,3; Karel Urbášek 2,3; Martin Zvonař 4; Kateřina Kolářová 4; Břetislav Lipový 1,3; Martin Knoz 1,3,5; Jakub Holoubek 1,3

Authors place of work: Department of Burns and Plastic Surgery, University Hospital Brno, Czech Republic 1; Department of Pediatric Plastic Surgery – Department of Pediatric Surgery, Orthopedics and Traumatology, University Hospital Brno, Czech Republic 2; Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic 3; Department of Kinesiology, Faculty of Sport Studies, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic 4; Department of Plastic and Aesthetic Surgery, St. Anne‘s University Hospital, Brno, Czech Republic 5

Published in the journal: ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 63, 2, 2021, pp. 46-51

doi: https://doi.org/10.48095/ccachp202146Introduction

Traumatic thumb loss is a serious injury with an enormous health impact and effect on patient's daily life. An effort to restore the handgrip is the goal during post-traumatic recovery, allowing the patient to return to a near normal hand functionality. There are many thumb reconstruction methods ranging from lengthening the first metacarpal or index finger pollicization to toe transplantation [1]. Plastic surgeons attempt to find the delicate balance between restoring handgrip while minimizing damage to donor areas. From many published studies, there are only a few that concern the inevitable health impact on the donor site after thumb reconstruction. Patients should be informed about all benefits and limitations of this surgery.

The aim of the study was to determine the effects on patient's gait after thumb reconstruction by the twisted-toe technique modified by Kempný et al. [2]. According to this method, a neothumb is constructed with a partial onychocutaneous flap from the great toe and an osteotendinous flap from the second toe. Subsequently, a neo-great toe is created by combining the onychocutaneous part of the second toe and the remaining parts of the great toe (Fig. 1, 2).

Fig. 1. Aesthetic result in one case, 11 years postoperatively.

Fig. 2. Functional result in one case, 11 years postoperatively.

Foot pressure distribution in static and dynamic conditions during barefoot walking, walking with a standard type of shoes, and 3D-gait analysis were evaluated in patients with thumb reconstruction by twisted-toe technique. Combining results of all pedobarography measurements and gait analysis enabled us to describe changes in plantar pressure and lower limb joint loading postoperatively.

Material and methods

Study design

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Brno. Patients who suffered a traumatic thumb loss and were treated by the same plastic surgeon (Kempný, MD) were included in the study. All patients underwent a thumb reconstruction using the twisted-toe technique modified by Kempný. The patients included in the study fulfilled the following criteria: age 15–65 years, no comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, prior stroke, oncological diseases of musculoskeletal or nervous system), no trauma of lower limbs or spine in the past, no congenital malformation or degenerative diseases of the musculoskeletal system, and BMI < 30. The study included only patients whose post-surgery period had exceeded two years.

All patients in the study underwent the following tests: the Emed® Novel pedobarography system for evaluating foot pressure distribution in static and dynamic conditions, the Pedar® Novel system for step timing analysis during walking in shoes equipped with sensor insoles, and 3D-gait analysis for monitoring of lower extremity joints loading.

Principles of pedobarography tests and gait analysis

The Emed® Novel pedobarography system is one of the methods for measuring plantar pressure distribution in static and dynamic conditions. The limitation of this system is that the patient is required to walk barefoot maintaining natural gait and at the same time step in the center of the sensor platform in order to obtain accurate readings [3].

This system provides data about the foot contact area on the pressure sensor pad, maximum force, peak pressure (the highest value in each region) and pressure time integral (including both the pressure affecting the pad during the whole gait phase contact and its time). A customized mask comprised of 10 foot regions (M1–M10) was fitted to each pedobarographic image (Fig. 3). The results for the entire foot surface and each region are available separately. Standardized partitioning of each foot image allowed for a comparison of the left and the right foot for all patients (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. Ten regions of foot made by automask program Emed® Novel pedobarography systems.

Fig. 4. Distribution of plantar pressure on the left foot (affected limb with a neo-toe) and on the right foot (non-affected foot).

The Pedar® Novel system is an in-shoe dynamic pressure measuring system. Its advantages include better monitoring of natural gait, making it ideal for standardized step timing analysis. The time value of stride (from right-heel contact to the subsequent right-heel contact), step (from right-heel contact to left-heel contact), stance (one foot contact time with pad), swing (time when the foot is not in contact with pad), and others were assessed.

The 3D-gait analysis was performed by the Vicon motion capture system (8 infrared cameras T020) and 2 force plates (AMTI OR6-7-2000). Six parameters were chosen to describe gait changes: sagittal ankle kinematics and 5 kinetic parameters (ankle sagittal and frontal moment, ankle sagittal power, knee frontal moment in the first and second part of stance phase). These parameters were selected mainly because they are ideal for reflecting gait cycle alternations for this specific pathological condition. The first ray (hallux) is loaded particularly in the second half of the stance phase, the reason being is to divide frontal knee kinetics into the 1st and 2nd half of stance phase. The hallux is important for transmitting muscle propulsion power generated by the triceps surae muscle and other plantar flexors in the pre-swing phase. Sagittal ankle joint loading and propulsion energy are predominantly represented by ankle sagittal moment and ankle sagittal power. Another presumption was there would be obvious gait changes of ankle and knee frontal balance parameters represented by frontal knee moments in patients undergoing twisted-toe thumb reconstruction.

Statistical analysis

The gait characteristics obtained by all three methods were compared between the affected and non-affected extremity in all patients. The third step method was applied in Emed® Novel pedobarography system: the first two steps represent acceleration gait phase and then the actual monitoring is performed starting with the third step, as the gait is stabilized. To avoid variations in the gait cycle, the patient continued to walk even after the foot made contact with the sensor platform [4]. The resulting values of maximum force, peak pressure, pressure time integral, and contact area were determined as an average value of five measurements. Step timing analysis by the Pedar® Novel system and gait characteristics by 3D-gait analysis were also established as a mean value of at least three measured trials of each patient. The analysis was carried out using the statistical package STATISTICA Ver. 12, and the Wilcoxon matched pairs test was used while assessing statistically a significant level at P ≤ 0.1.

Results

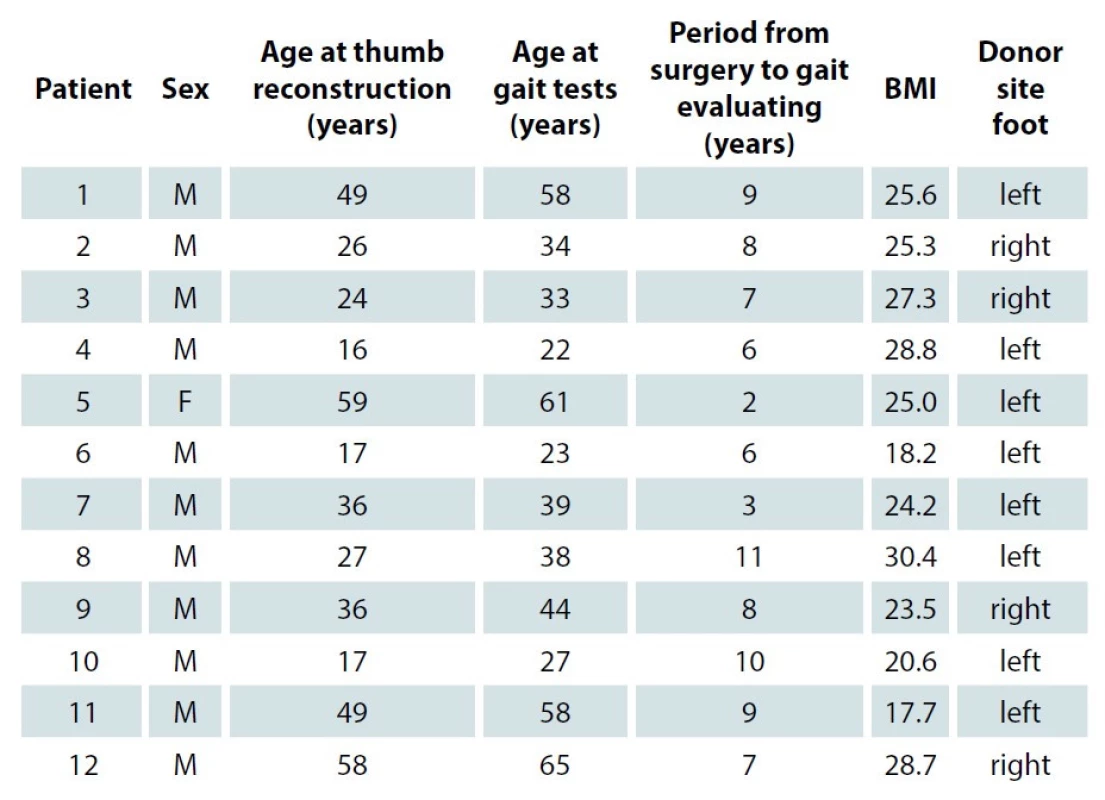

Twelve patients were included in the study: 11 males and 1 female (Tab. 1). The mean age of the patients during this study was 41.8 years (22–65 years). The mean age of the patients at the time of thumb reconstruction was 34.5 years (16–59 years). The left foot was used as a donor site in 8 cases (66.7%). The mean interval between pedobarography measurement and surgery was 7.2 years (2–11 years).

Tab. 1. Characteristics of all patients treated with twisted-toe technique.

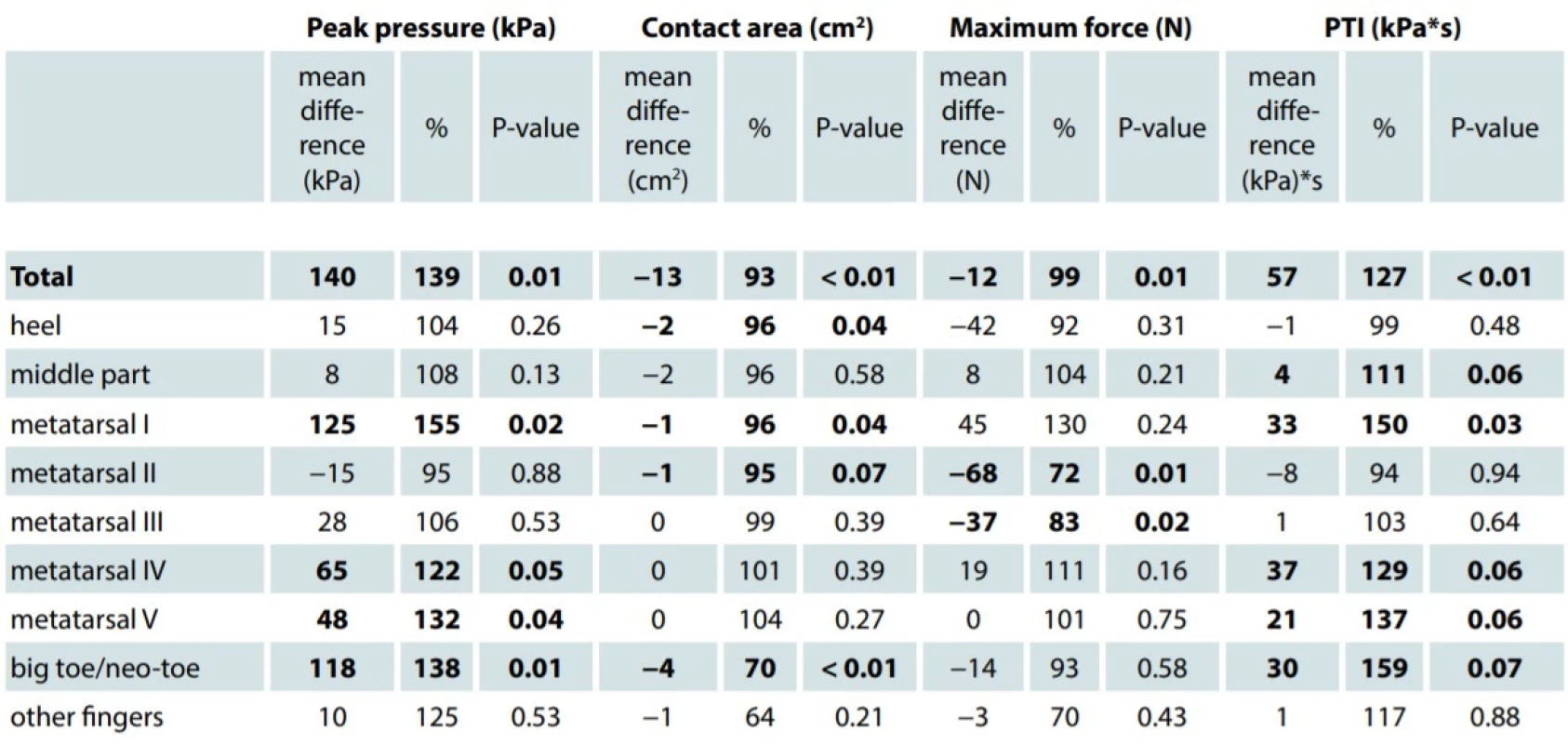

BMI - body mass index, F - female, M - male The differences of maximal plantar pressure between the affected and non-affected extremity were statistically significant in the following areas: I., IV. and V. metatarsal region, neo–great toe and total peak pressure of the whole foot (Tab. 2). Pressure time integral, which indicates the time of maximal pressure action in a defined area, was significantly higher by 27% in I. metatarsal region. The mean peak pressure of the affected foot was significantly higher by 39%; conversely, the maximal force was lower by 1% in total, and up to 28% in the area of II. metatarsal region. In comparison to the non-affected limb, the contact area of the affected foot was statistically significantly reduced by 7%, with the difference averaging 13 cm2. The significant part of the reduction was registered at the neo-toe as well as at the heel and the I. metatarsal region.

Tab. 2. The differences of maximal plantar pressure, pressure time integral, contact area and maximum force between the affected and non-affected foots. The minus sign and the decrease under 100% mean reduction of the parametr in the affected limb. The significance levels were set at P ≤ 0.1 (in bold).

Median values of temporal gait characteristics were equal for both affected and non-affected extremities. The stride was measured at 1.12 sec, the step at 0.56 sec, the stance at 0.69 sec, and the swing at 0.44 sec.

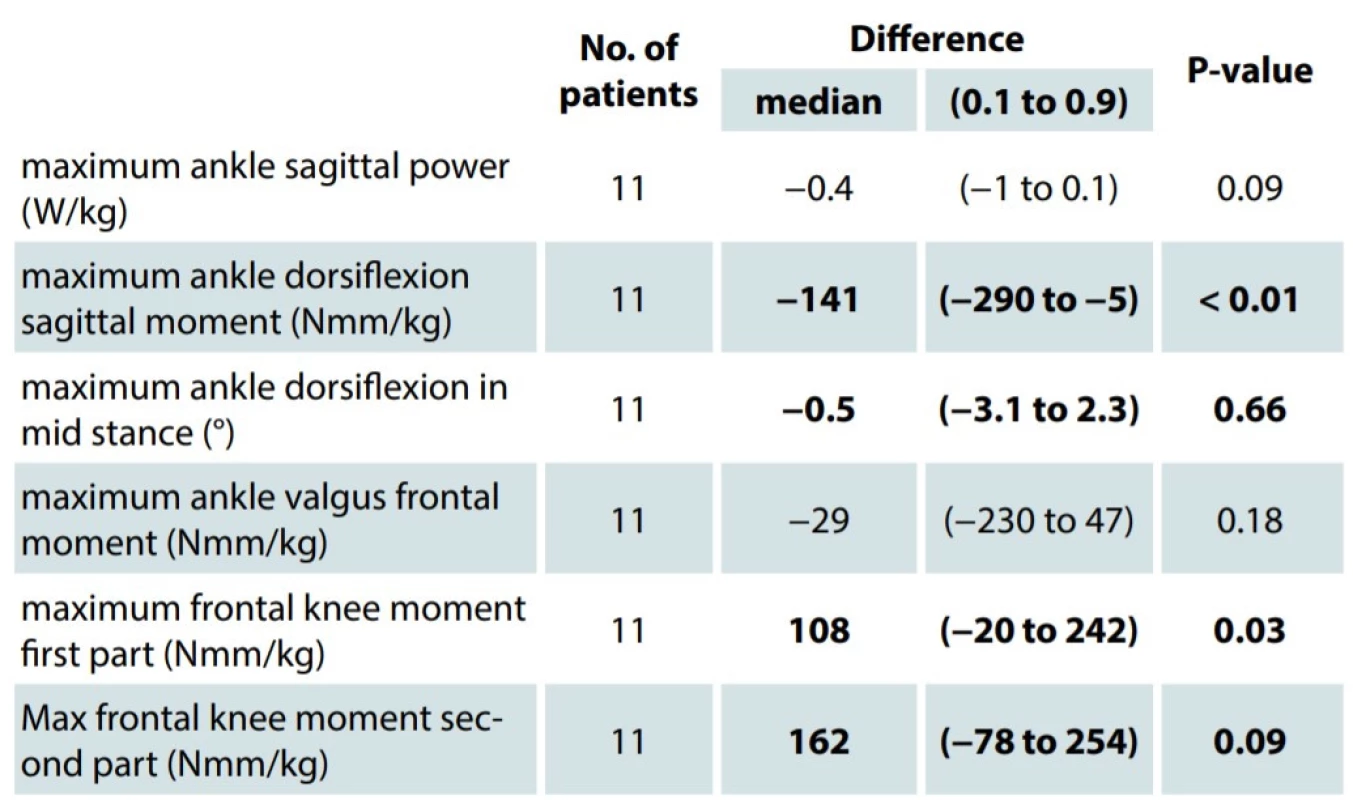

The 3D-gait analysis was only completed by 11 patients. One patient was excluded from the study due to non-compliance during examination resulting in invalid test values. The difference between the affected and non-affected limb was statistically significant in parameters representing ankle loading in the sagittal plane (maximal sagittal ankle moment and maximal ankle sagittal power) and knee loading (maximal frontal knee moment in the first and second half of the stance phase). There were no statistically significant differences in maximal frontal ankle moment and sagittal ankle kinematics (representing ankle loading in frontal plane and ankle range of movement (Tab. 3).

Tab. 3. Parameters of 3D-gait analysis. The minus sign means reduction of the parameter in the affected limb. The significance levels were set at P ≤ 0.1 (in bold).

Discussion

Traumatic thumb loss is a serious injury affecting patient´s ability to work and function in daily life activities. Microsurgical or non-microsurgical methods of thumb reconstruction are available and they are based on the post-traumatic condition of the affected hand, sufficient blood supply of the affected hand and donor site, patient´s comorbidities, and reasonable goals for post-operative hand functioning.

The twisted-toe technique was first described by Foucher in 1980 and subsequently developed and modified by Tsai, Aziz and Iglesias [5–7]. The twisted-toe technique allows a reconstructive surgeon to create a very natural-appearing neothumb with good stability and grip force [2]. Many published studies focus on the long-term results of hand functioning [8,9], but fewer on the impact at the donor site. Studies analyzing foot conditions – specifically after toe-to-hand transfer [10] or thumb reconstruction by modified wraparound flap [11] – are based more on subjective observations of patients [12] than on objective assessment. Pedobarography and the 3D-gait analysis are used for objective evaluation of gait, pressure distribution, and joint loading [12]. Currently these two methods are commonly used in studies of gait in obese [13,14] and diabetic [15–17] patients, or in studies evaluating post-traumatic conditions [18,19]. In patients with less common diagnoses, such as Down syndrome [20], Ehlers-Danlos syndrome [21] or ankylosing spondylitis [22], these two methods might be utilized as well. Pan et al. [23] published outcomes of 20 patients who underwent thumb reconstruction applying the modified wraparound flap method. No significant differences in 5 biomechanical parameters (timing, trajectory, symmetry, average peak force, and peak pressure between donor foot and contralateral foot) were found in gait analysis or in dynamic pedodynographic measurements.

This study reveals that patients who underwent the thumb reconstruction by twisted-toe technique do not bear any visible signs of lower extremity disability during gait. Patients do not limp, and there were no significant differences in temporal gait parameters between the affected and non-affected extremity. However, the thumb reconstruction had some effects: plantar pressure distribution is changed in terms of higher plantar pressure of neo-toe and the I. metatarsal area, reduction of total contact area (not only of the neo-toe, but also of the heel region) and lower maximal force of the affected foot. The result is forefoot overloading.

The donor foot condition is comparable with a more common foot deformity, hallux valgus (HV). There are a few studies discussing gait parameters associated with HV [24]. Many describe greater hallux peak pressure, peak pressure under the first metatarsal head [25], and greater mean pressure [26] in HV subjects compared to controls. HV has been linked to foot pain, poor balance and increased falls in older adults [27,28]. Similar changes in foot pressure distribution in patients with halux valgus are seen in patients from this study, suggesting the development of a foot disability after thumb reconstruction.

According to the 3D-gait analysis, tissue harvesting at the donor site leads to uneven loading of the ipsilateral knee joint, especially increased loading of its medial compartment – the area of the knee most commonly affected by osteoarthritis (OA) [29,30]. In their MOST study, Sharma et al. [31] found that varus alignment is a risk factor for incident cartilage damage which leads to OA of the knee. A similar pathology is presented in this study, wherein patients undergoing thumb reconstruction by twisted-toe technique are at risk of knee joint OA. Insoles, especially lateral wedge insoles, are commonly recommended for patients with medial knee OA [32].

Based on these findings, and considering other foot pathologies, individually adapted shoe insoles might be appropriate for the prevention of medial compartment cartilage damage and foot pain.

Conclusion

The twisted-toe technique is a thumb reconstruction method associated with a very natural - appearing neo-thumb with good stability and grip force [2]. The degree of functional disability of the donor limb was observed using pedobarography systems and 3D-gait analysis. There were no changes in temporal gait parameters recorded. The plantar pressure distribution differed in the donor: increased plantar pressure in neo-toe and I. metatarsal areas were measured. The forefoot overloading and overloading of medial knee joint compartment were also observed. Post-operative anatomic and functional changes of the affected limb might cause earlier development of knee joint osteoarthritis.

Roles of authors: All authors contributed equally to this work.

Financial disclosures: None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

Disclosure: Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Brno and proceeded according to the general principles of good clinical practice. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Olga Košková MD, PhD

Department of Pediatric Plastic Surgery – Department of Pediatric Surgery, Orthopedics and Traumatology

University Hospital Brno

Černopolní 9

613 00 Brno

Czech Republic

e-mail: koskova.olga@fnbrno.cz

Submitted: 28. 02. 2021

Accepted: 02. 05. 2021

Zdroje

- Kempný T., Lipový B., Brychta P. Historie a současnost rekonstrukce palce ruky. Rozhl v Chir. 2015, 94 : 145–152.

- Kempny T., Paroulek J., Marik V., et al. Further developments in the twisted-toe technique for isolated thumb reconstruction: our method of choice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013, 131 : 871–879.

- Abdul Razak AH., Zayegh A., Begg RK., et al. Foot plantar pressure measurement system: a review. Sensors. 2012, 12 : 9884–9912.

- Bus SA., Lange AD. A comparison of the 1-step, 2-step, and 3-step protocols for obtaining barefoot plantar pressure data in the diabetic neuropathic foot. Clin Biomech. 2005, 20 : 892–899.

- Foucher G., Chabaud M. The bipolar lengthening technique: a modified partial toe transfer for thumb reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998, 102 : 1981–1987.

- Tsai T-M., Aziz W. Toe-to-thumb transfer: a new technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991, 88 : 149–153.

- Iglesias M., Butron P., Serrano A. Thumb reconstruction with extended twisted toe flap. J Hand Surg Am. 1995, 20 : 731–736.

- Kotkansalo T., Vilkki S., Elo P. Long-term results of finger reconstruction with microvascular toe transfers after trauma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2011, 64 : 1291–1299.

- Lin PY., Sebastin SJ., Ono S., et al. A systematic review of outcomes of toe-to-thumb transfers for isolated traumatic thumb amputation. Hand. 2011, 6 : 235–243.

- Stupka I., Veselý J., Dražan L., et al. Foot morbidity following toe to hand transfers. Eur J Plast Surg. 2004, 27 : 283–287.

- Kotkansalo T., Elo P., Luukkaala T., et al. Long-term effects of toe transfers on the donor feet. J Hand Surg Eur. 2014, 39 : 966–976.

- Wafai L., Zayegh A., Woulfe J., et al. Identification of foot pathologies based on plantar pressure asymmetry. Sensors (Basel). 2015, 15 : 20392–20408.

- Periyasamy R., Mishra A., Anand S., et al. Foot pressure distribution variation in pre-obese and non-obese adult subject while standing. Foot. 2012, 22 : 276–282.

- Butterworth PA., Urquhart DM., Landorf KB., et al. Foot posture, range of motion and plantar pressure characteristics in obese and non-obese individuals. Gait Posture. 2015, 41 : 465–469.

- Bennetts CJ., Owings TM., Erdemir A., et al. Clustering and classification of regional peak plantar pressures of diabetic feet. J Biomech. 2013, 46 : 19–25.

- Lobmann R., Kayser R., Kasten G., et al. Effects of preventive footwear on foot pressure as determined by pedabarography in diabetic patients: a prospective study. Diabet Med. 2001, 18 : 314–319.

- Fernando M., Crowther RG., Cunningham M., et al. The reproducibility of acquiring three dimensional gait and plantar pressure data using established protocols in participants with and without type 2 diabetes and foot ulcers. J Foot Ankle Res. 2016, 9 : 4.

- Jansen H., Frey SP., Ziegler C., et al. Results of dynamic pedobarography following surgically treated intra-articular calcaneal fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013, 133 : 259–265.

- Schepers T., Kieboom BC., Kieboom B., et al. Pedobarographic analysis and quality of life after Lisfranc fracture dislocation. Foot ankle Int. 2010, 31 : 857–864.

- Pau M., Galli M., Crivellini M., et al. Relationship between obesity and plantar pressure distribution in youths with Down syndrome. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013, 92 : 889–897.

- Pau M., Galli M., Celletti C., et al. Plantar pressure patterns in women affected by Ehlers-Danlos syndrome while standing and walking. Res Dev Disabil. 2013, 34 : 3720–3726.

- Aydin E., Turan Y., Tastaban E., et al. Plantar pressure distribution in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Biomech. 2015, 30 : 238–242.

- Pan Y., Zhang L., Tian W., et al. Donor foot morbidity following modified wraparound flap for thumb reconstruction: a follow-up of 69 cases. J Hand Surg Am. 2011, 36 : 493–501.

- Nix SE., Vicenzino BT., Collins NJ., et al. Gait parameters associated with hallux valgus: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Res. 2013, 6 : 1–12.

- Bryant A., Tinley P., Singer K. Radiographic measurements and plantar pressure distribution in normal, hallux valgus and hallux limitus feet. Foot. 2000, 10 : 18–22.

- Martínez-Nova A., Sánchez-Rodríguez R., Pedrera-Zamorano JD., et al. Plantar pressures determinants in mild hallux valgus. Gait Posture. 2010, 32 : 425–427.

- Chaiwanichsiri D., Janchai S., Tantisiriwat N. Foot disorders and falls in older persons. Gerontology. 2009, 55 : 296–302.

- Nix S., Smith M., Vicenzino B. Prevalence of hallux valgus in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res. 2010, 3 : 21.

- Massardo L., Watt I., Cushnaghan J., et al. Osteoarthritis of the knee joint: an eight year prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989, 48 : 893–897.

- Johnson F., Leitl S., Waugh W. The distribution of load across the knee. A comparison of static and dynamic measurements. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1980, 62 : 346–349.

- Sharma L., Chmiel JS., Almagor O., et al. The role of varus and valgus alignment in the initial development of knee cartilage damage by MRI: the MOST study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013, 72 : 235–240.

- Jordan KM., Arden NK., Doherty M., et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: Report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003, 62 : 1145–1155.

Štítky

Chirurgia plastická Ortopédia Popáleninová medicína Traumatológia

Článok vyšiel v časopiseActa chirurgiae plasticae

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2021 Číslo 2- Metamizol jako analgetikum první volby: kdy, pro koho, jak a proč?

- Kombinace metamizol/paracetamol v léčbě pooperační bolesti u zákroků v rámci jednodenní chirurgie

- Antidepresivní efekt kombinovaného analgetika tramadolu s paracetamolem

- Srovnání analgetické účinnosti metamizolu s ibuprofenem po extrakci třetí stoličky

- Možnosti využití metamizolu v léčbě akutních primárních bolestí hlavy

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Editorial

- Dlouhodobé výsledky morbidity donorského místa po rekonstrukci palce twisted-toe technikou

- Supraklavikulární ostrůvkový lalok v rekonstrukci hlavy a krku

- Volný lalok tensor fasciae latae

- Přítomnost cirkulujících nádorových buněk u pacientky s mnohočetnými invazivními bazocelulárními karcinomy - kazuistika

- Pyoderma gangrenosum - vzácná komplikace redukční mammoplastiky - kazuistika

- Podtlaková léčba a její využití v orofaciální oblasti u onkologických pacientů - dvě kazuistiky

- Třicet pět let Oddělení plastické chirurgie a léčby popálenin FN Hradec Králové

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Pyoderma gangrenosum - vzácná komplikace redukční mammoplastiky - kazuistika

- Volný lalok tensor fasciae latae

- Supraklavikulární ostrůvkový lalok v rekonstrukci hlavy a krku

- Dlouhodobé výsledky morbidity donorského místa po rekonstrukci palce twisted-toe technikou

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy