The impact of aesthetic plastic surgery on body image, body satifaction and self-esteem

Authors:

E. Asimakopoulou 1; H. Zavrides 2; T. Askitis 3

Authors‘ workplace:

School of Health Sciences, Frederick University, Nicosia, Cyprus

1; Harris Zavrides Plastic Surgery Centre, Nicosia, Cyprus

2; Medical Centre of Sexual Health, Dr Thanos Askitis, Nicosia, Cyprus

3

Published in:

ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 61, 1-4, 2019, pp. 3-9

INTRODUCTION

Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery refers to a surgical specialty, which includes facial and body surgical procedures. Plastic Surgery deals with the maintenance, restoration or enhancement of an individual’s physical appearance1. While Reconstructive Plastic Surgery aims to reconstruct a part of the body or improve its function, Aesthetic Plastic Surgery aims to improve the appearance of it2. Therefore, aesthetic surgery is a means to improve quality of life, as its purpose is to improve a person’s appearance and/or to remove signs of aging3.

The number of cosmetic procedures performed in the United States has almost doubled since the start of the century, with the five most common surgeries being breast augmentation, liposuction, breast reduction, eyelid surgery and abdominoplasty4. Nearly 16 million cosmetic procedures were performed in the United States alone in 2014, of which 92% were performed in women4. Cosmetic surgical procedures were up 11% in 2017 and patients age was 35–50 years when they had the greatest percentage of surgical procedures performed (38.6% of the total number for all age groups)5.

In bibliography related to cosmetic surgery and body image, many factors may increase the popularity of cosmetic surgery, such as stress, low self-esteem, conformity and physical injuries. People, who have a negative body image by themselves, appear to be more interested in cosmetic surgery6,7. The term “body image” is used in many disciplines, including psychology, medicine, psychiatry, nursing and cultural studies and has been defined in different ways8. The most common refer to the individual’s experience of embodiment, personal perceptions and self-attitudes toward one’s appearance9. Moreover, the two most central body image dimensions are indicated to be the body image evaluation – satisfaction or dissatisfaction – and the body image investment – the importance of one’s appearance to his or her sense of self-worth9.

Cosmetic surgery does much more than enable people to feel better about their physical appearance. Plastic surgery helps patients to regain their self-esteem and self-respect10–13 and it has also an impact on their interpersonal relations, as it influences also social life, sexuality and personal relationships11.

The impact of surgery on body image has been studied for procedures such as breast augmentation, breast reduction, abdominoplasty, and facial plastic surgery, providing therefore a link between aesthetic surgery and physical and mental health14–18. A review by Crerand et al reported enhanced body image at two-years follow up in the majority of women who underwent breast augmentation15. Although the perception of women undergoing breast augmentation surgery is often unclear, the benefits of the process have shown a self-esteem rebound and positive emotion according to their sexuality2. The greatest sexual benefits were seen in women who underwent breast augmentation, breast lift, or body contouring procedures15,19. Macromastia was frequently associated with body image dissatisfaction and maladaptive behavioural changes. Body image improvement and symptom relief occurred independently of preoperative body weight19. Similar outcomes were observed in studies on abdominoplasty, which was associated with positive psychological effects, including improved evaluations of patients’ overall appearance, body image satisfaction, and self-esteem, especially in the massive weight loss population17,20,21. Finally, these aspects have been investigated also in patients undergoing facial plastic surgery16,18,22.

Cosmetic surgery in Cyprus has also developed recently. Traveling to undergo cosmetic surgery is usually a secondary reason. It could be due to affordability and quality of healthcare. The aims of this study was to:

- describe participants´ body image, body satisfaction, self-esteem and their feelings about their body,

- assess the impact of cosmetic surgery in altering participants´ body image, body satisfaction, self-esteem and their feelings about their body.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

A total of 150 consecutive patients visiting a Plastic Surgery Clinic were asked to participate in the study. Among them, 128 agreed to participate (response rate = 85.3%). Reasons of refusal related to time constraints and burden of participation. Those who agreed to participate and those who disagreed were not found to be different in terms of gender, age and type of surgery (p > 0.05). Informed consent was obtained from all individuals who agreed to participate in the study.

Measures

The questionnaire consisted of the following sections:

Demographic information and information about the type of surgery: Data were collected with regards to participants’ gender, age, family status, educational and employment status.

Feelings about one’s body: Consisted of twelve questions asking about participants’ negative and positive emotions about their body. For each emotion, responses were coded as a binary variable (yes–no).

Body image/body satisfaction: It consisted of three questions enquiring about participants’ degree of satisfaction with their physical appearance, their feelings when looking themselves naked to the mirror and their feelings about their body during sexual intercourse. Responses on all three questions were evaluated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 to 5 [1 = not at all and 5= very much] for the first item and 1 = very bad to 5 = very good for the remaining two. Composite scores were calculated for this section, as the internal consistency of the scale was considered high at both pre-intervention and post-intervention measures: Cronbach α = 0.84 before the intervention and Cronbach α = 0.85 after the intervention. Higher scores indicate greater satisfaction with one’s body.

Self-esteem: Answers are evacuated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Composite scores were calculated for this section, as the internal consistency of the scale was considered high at both pre-intervention and post-intervention measures: Cronbach α = 0.79 before the intervention and Cronbach α = 0.89 after the intervention. Higher scores indicate greater self-esteem.

The body image section of the questionnaire was developed so that its items could be utilized both independently (item analysis) and as a scale (composite score analysis). The self-esteem section of the questionnaire was created similarly. For their development, the following steps were undertaken:

Items were drafted after a thorough literature review and five qualitative interviews with women who had undertaken cosmetic surgery. The items were then reviewed by three experts on the field for appropriateness (1 researcher, 1 psychiatrist and 1 aesthetic plastic surgeon). The questionnaire was then pilot tested for its comprehensibility and appropriateness of the items on a sample of 20 individuals visiting the clinic (these 20 participants were not included in the present study). For each section, any item with item-total correlation below 0.3 was dropped. The final version of the instrument was administered in the present study.

Procedure

The questionnaire was administered to 128 people who had undergone certain aesthetic plastic surgery procedures one week before and three months after the surgery. Three months postoperative assessment is a good timing to have a quick follow up access to the whole sample. The less invasive procedures and the shorter recovery periods led us to make assessments after three months. In addition, it has been observed that there is no significant difference in patients’ satisfaction with health and appearance in a postoperative evaluation performed after three to six months20. The study was performed inductively to achieve psychological desensitization of subjects and to obtain objective measurements, because subjects would not be expected to describe their self-image the same way before the operation as afterwards4. The inductive approach ensured a higher degree of certainty in the answers of our sample. Collection of data took place in the Plastic Surgery Clinic at two time points: one week before the surgery and three months after the surgery. The patients had 15 minutes time; sufficient time for right and reliable completion of the questionnaire. They were not given detailed instructions, but only general information concerning the aim and the objectives of the research. The patients were encouraged to read carefully the first page of the questionnaire, which provided explicit and complete directions for its completion.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics was calculated using relative and absolute frequencies for categorical variables; while means and standard deviations were computed for continuous variables. In order to investigate differences before and after the procedure, for changes in frequencies of participants with regards to experiencing negative and positive feelings, McNemar test was employed, as the data are paired. Data regarding body satisfaction and self-esteem obtained from the questionnaires before and after the procedure are provided in corresponding tables. However, to explore the differences of participants’ body satisfaction and body self-esteem, a Related Samples Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test (non-parametric test) was used because data were not normally distributed. In terms of composite scores (body image scale score and self-esteem scale score), statistically significant differences were explored by employing paired samples t-test.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

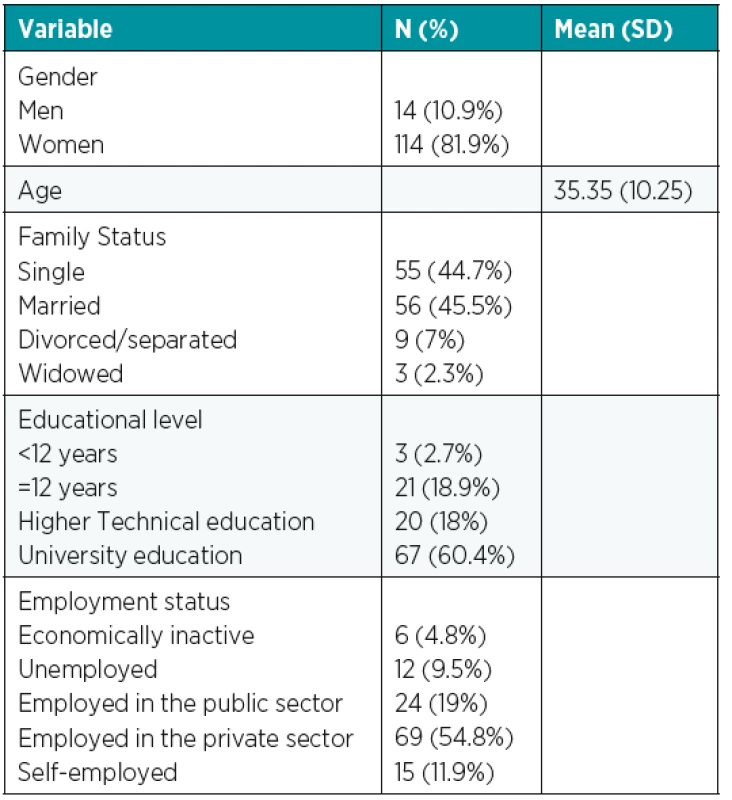

A total of 128 people participated in the present study. The vast majority were women (81.9%) and respondents’ mean age was 35.35 years. Approximately one out of two participants was single (44.7%) and one out of two was married (45.5%). The majority of respondents had completed undergraduate/postgraduate studies (60.4%) and one out of two participants was employed in the private sector (54.8%). Sample characteristics are presented in detail in Table 1.

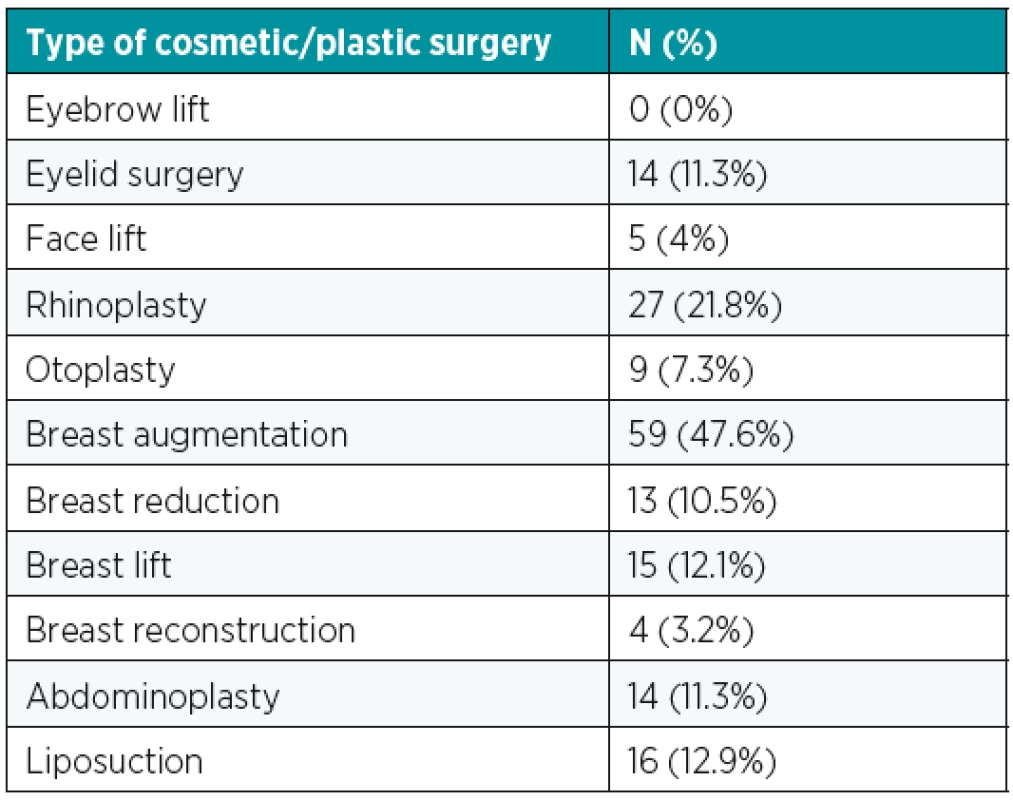

As shown in the Table 2, the most popular cosmetic surgery among respondents was breast augmentation with approximately one out of two participants, who have undergone this procedure (47.6%). Moreover, approximately one out of five respondents had undergone rhinoplasty (21.8%). The least popular forms of cosmetic surgery were eyebrow lift (0%), breast reconstruction (3.2%), and face lift (4%).

Body Image: Description and changes after the treatment

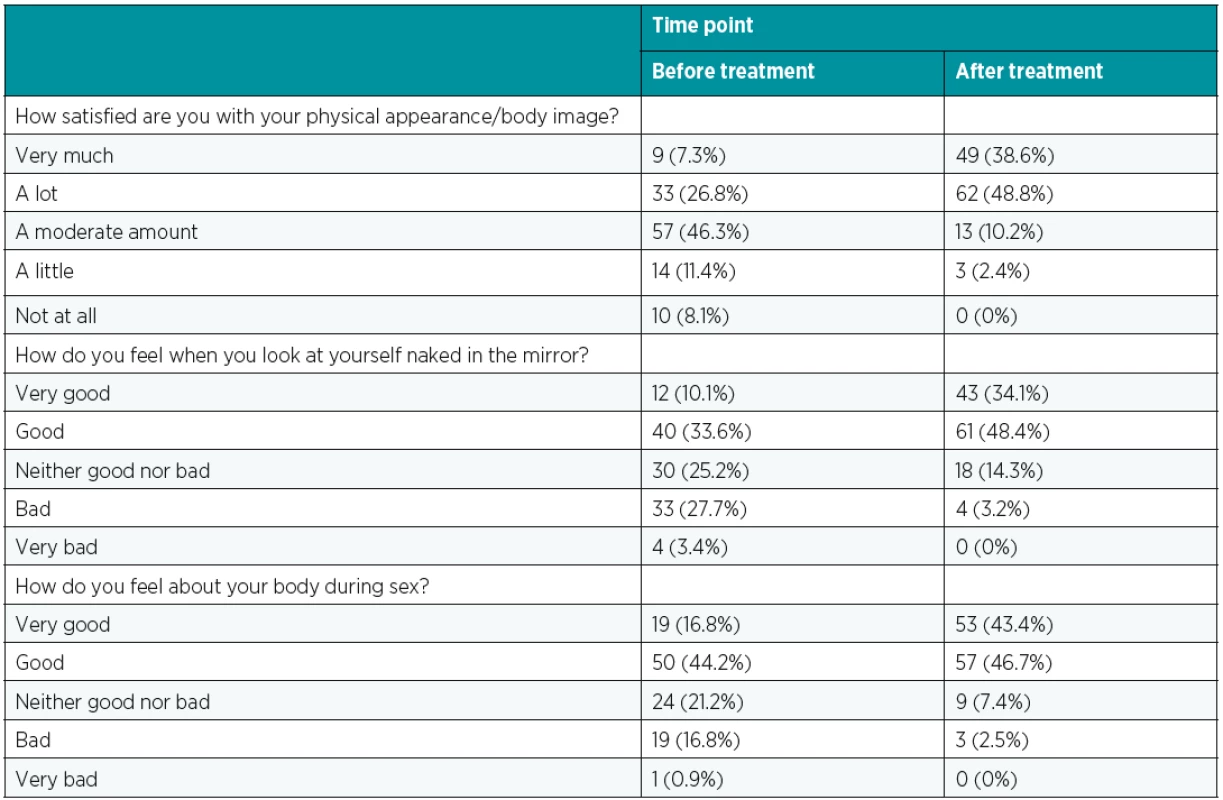

Prior to treatment, only a small minority of participants reported feeling of very satisfied with their physical appearance/body image (7.3%); however, after treatment this figure rose to 38.6%. A Related Samples Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test revealed a highly significant effect of treatment on respondents’ levels of satisfaction with their physical appearance/body image (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

Prior to treatment, approximately 30% of participants reported feeling of bad/very bad when they looked at themselves naked in the mirror (31.1%). This figure dropped to 3.2% after treatment; while the vast majority stated that they felt good/very good (82.5%). A Related Samples Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test revealed a highly significant effect of treatment on respondents’ levels of satisfaction with looking at themselves naked in the mirror (p < 0.001) (see Table 3).

In a similar way, a noteworthy percentage of participants reported feeling of bad/very bad about their body during sex (17.7%) before treatment. This figure dropped to 2.5% after treatment. A Related Samples Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test revealed a highly significant effect of treatment on respondents’ levels of satisfaction with their body during sex (p<0.001).

A similar pattern of results was shown when changes were explored in terms of composite scores. In particular, mean body satisfaction was found to be lower before than after the intervention: mean = 9.91 (SD = 2.67) and mean = 12.65 (SD = 1.9) respectively. A paired samples t-test revealed the difference to be statistically significant: t(108) = 10.71, p <0.001. (see Table 3).

Feelings about one’s body: Description and changes after treatment

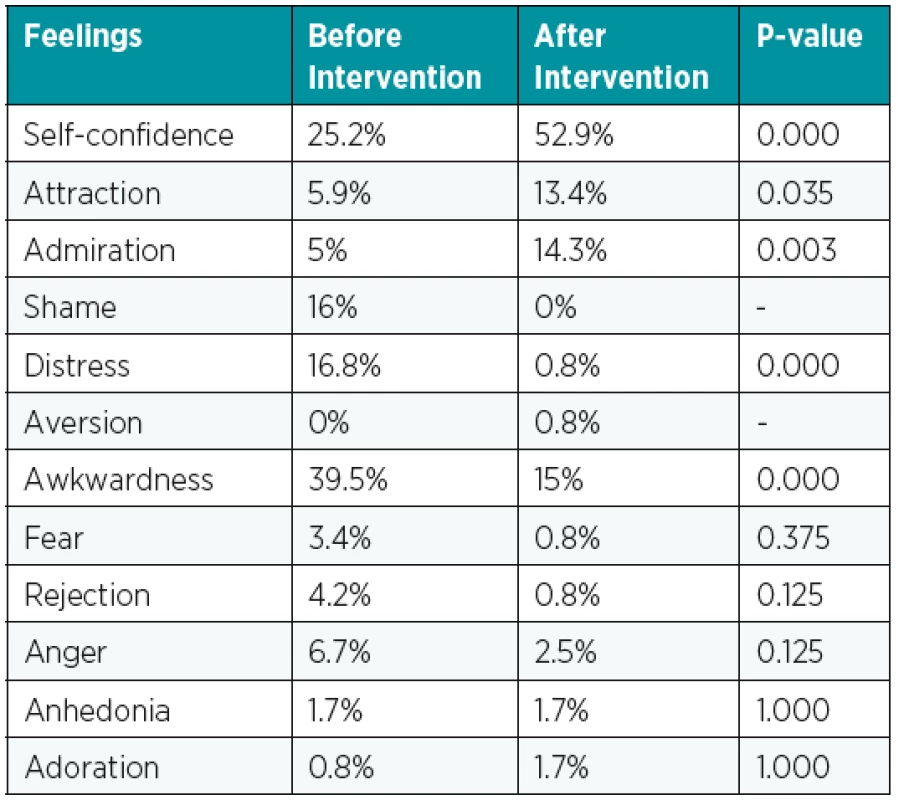

The preponderant feeling that the participants experienced about their body before treatment was found to be awkwardness (39.5%), followed by self-confidence (25.2%), distress (16.8%), and shame (16%). It merits noting that aversion, adoration and anhedonia were only reported by a small minority. On the contrary, after treatment, one out of two participants reported feeling of self-confidence, while the number of participants who were found to experience negative feelings about their body (shame, distress, aversion, fear, rejection and anhedonia) was close to zero (Table 4). Furthermore, as shown in Table 4, the intervention induced a statistically significant improvement (McNemar test was used) in three out of four positive feelings that the participants reported about their body: self-confidence, attraction and admiration. In the same time it also induced a statistically significant change in two out of eight negative feelings: distress and awkwardness.

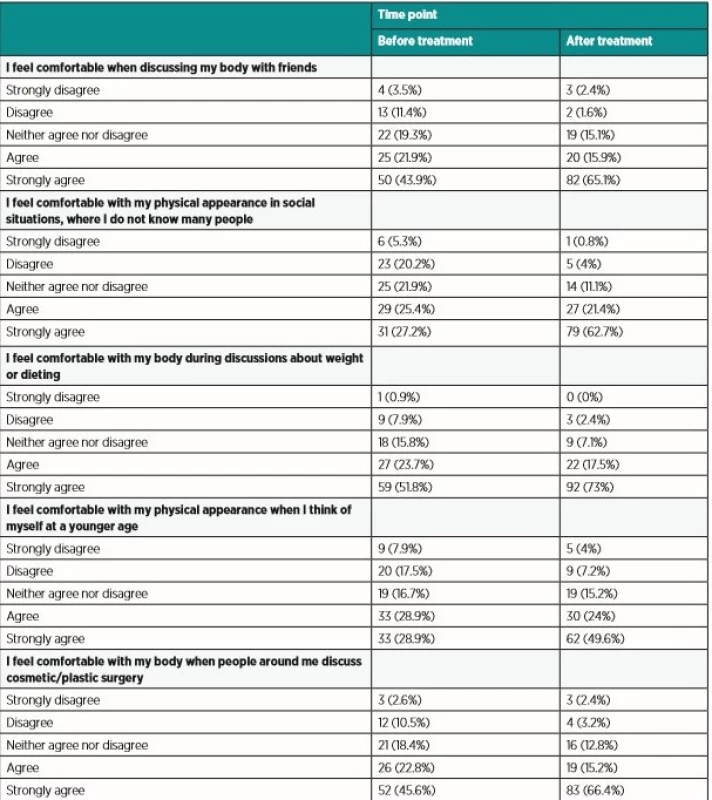

As shown in the Table 5, approximately 66% of respondents agreed with the statement that they feel comfortable when discussing their body with friends prior to receiving treatment. After the procedure, this percentage raised to approximately 80%. Approximately one out of two participants (52.6%) reported feeling to be comfortable with their physical appearance in social encounters/situations, where they did not know many people, prior to the procedure. This proportion increased to 84.1% after the treatment. The vast majority of respondents (75.5%) expressed their agreement with the statement “I feel comfortable with my body during discussions about weight or dieting” prior to treatment. This frequency raised further to 90.5% after the treatment.

Approximately one out of two participants expressed their comfort with their physical appearance when they think of themselves at a younger age (57.8%) prior to the procedure. After the procedure, the corresponding percentage raised to 73.6%. Before treatment, the vast majority of respondents was found to feel comfortable about their body when people around them discussed cosmetic/plastic surgery (68.4%). After the procedure, the corresponding figure reached 81.6%. A Related Samples Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test comparing the median item score prior to the procedure with the corresponding one after the procedure revealed a highly statistically significant effect (p < 0.001).

In a similar way, when composite scores were taken into consideration, respondents’ self-esteem was found to be significantly higher after treatment as compared to before treatment: mean = 19.1 and SD = 4.94 before treatment and mean = 21.89 and SD = 3.45 after treatment, t(113) = -8.02, p <0.001.

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to determine the effect of cosmetic surgery on body image, body satisfaction and self-esteem in Cypriot population. According to the sample characteristics, women are the majority of subjects who undergo cosmetic surgery. In both the UK and Brazil, approximately 90% of cosmetic surgeries is performed in women, as they are the primary targets of cosmetic surgery industry23,24. Another study, in which life satisfaction, self-esteem, and body image were examined in two groups of patients, aesthetic and reconstructive surgery candidates, the patients demanding aesthetic surgery were mostly female25. The average age in the current study was 35 years. In Brazil, which has the highest number of cosmetic surgeries in the world after the USA, approximately 15% of cosmetic surgeries reported in 2009 was on adolescents younger than 18 years of age23,24. Moreover, according to Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank in the USA for 2017, patients aged 35–50 years had the greatest percentage of surgical procedures performed5.

The top cosmetic surgery procedure in this study was breast augmentation and the second one was rhinoplasty. This result is confirmed by the international bibliography5,15. An increasing number of Norwegian women undergo breast enlargement surgery for cosmetic and reconstructive reasons26. In 2017, in the USA, there were 333,392 breast augmentation procedures performed, especially in the age group 19–34 years5. Rhinoplasty is a popular aesthetic and reconstructive surgical procedure. It is one of the top five surgical cosmetic procedures performed worldwide27.

The results showed that satisfaction with physical appearance/body image improved after a cosmetic surgery; in the comparison of the pre - and post-operative answers the rates had risen from 7.3% to 38.6%. Based on some reports16,17,28, patient satisfaction is the main factor that dictates the success of the cosmetic surgery procedure. Satisfaction with own appearance after cosmetic surgery is a variable that is thought to play a central role in understanding the psychology of cosmetic surgery patients16.

The intervention induced a statistically significant improvement in three out of four positive feelings that the participants reported about their body: self-confidence, attraction and admiration. Especially, almost one out of two participants reported feeling of self-confidence after the operation. In the same time, it also induced a statistically significant change in two out of eight negative feelings: distress and awkwardness (see Table 4). It is important to note that in spite of the beneficial effect of the cosmetic surgical procedure, the majority of participants did not report positive feelings like attraction, adoration and admiration for their body, even after the procedure. The fact that positive feelings do not reach higher levels even after the procedure (e.g. self-confidence does not get higher, or other feelings) suggests exactly the psychological component in body image concept. That means that cosmetic surgery reaches up to a certain point only and then, one has to act also psychotherapeutically for optimization29.

The percentage of participants who agreed with the statements that they feel comfortable to discuss their body when people around them discussed aesthetic plastic surgery and during discussions about weight or dieting raised significantly after an aesthetic surgical procedure. This study confirms the results of other studies in bibliography that the effect of aesthetic surgery on body image and self-esteem is positive11,12,16,24,25.

It is important to note that in this study only the short-term impact of aesthetic plastic surgery was investigated. The short-term psychological effects of cosmetic surgery may either over - or underestimate the long-term benefits of such procedures30. Further research is needed to investigate whether the short-term effects of cosmetic surgery shown in this article persist over several years.

The results presented in the current study represent a part of authors’ team research. In another study-publication, the correlation of cosmetic surgery with social life, sexuality and personal relationships should be clarified, as cosmetic surgery does much more than enable people to feel better about their physical appearance31. Moreover, closer attention should be paid especially to body image and self-esteem in breast augmentation and rhinoplasty surgery.

Although body image dissatisfaction improves following an aesthetic surgery, the success of aesthetic surgical techniques does not necessarily approve the improvements in one’s body satisfaction and self-esteem. Body image is a dynamic perception of oneself, changing with time, which is affected by internal as well as external factors, such as interpersonal, environmental and temporary influences (tradition, society)32. According to bibliography, 5% to 15% of individuals who seek aesthetic medical treatments suffer from Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD). Persons with BDD rarely experience improvement in their symptoms following these treatments, leading some studies to suggest that BDD is a contraindication to treatment33.

CONCLUSION

The present study provides methodologically evidence of changes in body image, body satisfaction and self-esteem in Cypriot patients after having experienced an aesthetic plastic surgery. As the major driver for an aesthetic plastic surgery procedure is improvement in body image and self-esteem, it is necessary for plastic surgery team to consider the psychological status of the patient. A general psychological screening, consisting of an assessment of patient motivations and expectations, psychiatric status and history, body image concerns and BDD symptoms can identify persons who are not ready for an aesthetic plastic surgery procedure. The cooperation of medical and mental health professionals is required to achieve the best results for patient’s satisfaction from health care services.

Declaration of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Financial disclosure: The authors declare that this study has received no financial support.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Evanthia Asimakopoulou

7, Y. Frederickou Str. Pallouriotisa

Nicosia 1036

Cyprus

E-mail: hsc.ae@frederick.ac.cy

Sources

1. Davis K. Dubious equalities and embodied differences: Cultural studies on cosmetic surgery. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc.; 2003.

2. Shakespeare V, Cole RP. Measuring patient-based outcomes in a plastic surgery service: breast reduction surgical patients. Br J Plast Surg. 1997, 50 : 242–8.

3. Dreher R, Blaya C, Tenório JLC. Quality of Life and Aesthetic Plastic Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016, 4 : 862.

4. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. National Clearinghouse of Plastic Surgery Procedural Statistics. New York: ASPS Public Relations; 2014. Available from: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2014/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2014.pdf

5. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics. New York: ASPS Public Relations; 2017. Available from: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2017/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2017.pdf

6. Swami V, Charnorro-Permuzic T, Bridges S. Acceptance of cosmetic surgery: Personality and individual difference predictors. Body image. 2009, 6 : 7–13.

7. Frederick DA, Lever J, Peplau LA. Interest in cosmetic surgery and body image: Views of men and women across the lifespan. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007, 120 : 1407–15.

8. Padurarua C, Rascanu R. Body Scheme and Self-Esteem of Plastic Surgery Patients. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2013, 78 : 355–9.

9. Sarwer DB, Cash TF. Body image: interfacing behavioral and medical sciences. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2008, 28 : 357–8.

10. Zavrides H. Prosopoplasty: A new term? Arch Plast Surg. 2014, 41 : 3–4.

11. Foustanos A, Pantazi ., Zavrides H. Representations in plastic surgery: the impact of self-image and self-confidence in the work environment. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007, 31 : 435–42.

12. Horch RE. The role of plastic surgery in remodeling the body image. MMW Fortschr Med. 2004, 146 : 32–6.

13.Moss TP, Harris DL. Psychological change after aesthetic plastic surgery: a prospective controlled outcome study. Psychol Health Med. 2009, 14 : 567–72.

14. Foustanos A, Zavrides H. Surgical reconstruction of iatrogenic symmastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121 : 143e–4e.

15. Crerand CE, Infield AL, Sarwer DB. Psychological considerations in cosmetic breast augmentation. Plast Surg Nurs. 2009, 29 : 49–57.

16. Von Soest T, Kvalem IL, Roald HE. The effects of cosmetic surgery on body image, self-esteem, and psychological problems. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009, 62 : 1238–44.

17. Bolton MA, Pruzinsky T, Cash TF. Measuring outcomes in plastic surgery: body image and quality of life in abdominoplasty patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003, 112 : 619–25.

18. Foustanos A, Zavrides H. Reconstruction of facial burn sequelae utilizing tissue expanders with embodiment injection site: case report. Acta Chir Plast. 2006, 48 : 103–7.

19. Glatt BS, Sarwer DB, O’Hara DE. A retrospective study of changes in physical symptoms and body image after reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999, 103 : 76–82.

20. Papadopulos NA, Kovacs L, Krammer S, Herschbach P, Henrich G & Biemer E. Quality of life following aesthetic plastic surgery: a prospective study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007, 60(8):915–21.

21. Lazar CC, Clerc I, Deneuve S. Abdominoplasty after major weight loss: improvement of quality of life and psychological status. Obes Surg. 2009, 19 : 1170–5.

22. Imadojemu S, Sarwer DB, Percec I. Influence of surgical and minimally invasive facial cosmetic procedures on psychosocial outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol.2013, 149 : 1325–33.

23. Berer M. Cosmetic surgery, body image and sexuality. Reprod Health Matters. 2010, 18 : 4–10.

24. Farshidfar Z, Dastjerdi R, Shahabizadeh F. Acceptance of cosmetic surgery: Body image, Self-esteem and conformity. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2013, 84 : 238–42.

25. Ozgur F, Tuncali D, Gursu G. Life satisfaction, self-esteem and body image: a psychosocial evaluation of aesthetic and reconstructive surgery candidates. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1998, 22 : 412–19.

26. Kalaaji A, Bergsmark Bjertness C, Nordahl C. Survey of Breast Implant Patients: Characteristics, Depression Rate, and Quality of Life. Aesth Surgery J. 2013, 33 : 252–7.

27. Lalezari S, Daar DA, Mathew PJ. Trends in Rhinoplasty Research: A 20-Year Bibliometric Analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018, 42 : 1071–84.

28. Ching S, Thoma A, McCabe RE. Measuring outcomes in Aesthetic surgery: A comprehensive review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003, 111 : 469–80.

29. Vaughan-Turnbull C, Lewis V. Body image, objectification and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2015, 20 : 179–96.

30. Cook SA, Rosser R, Salmon P. Is cosmetic surgery an effective psychotherapeutic intervention? A systematic review of the evidence. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006, 59 : 1133–51.

31. Neavin T, Ramineni P, Alford A. Better Sex From the Knife? An Intimate Look at the Effects of Cosmetic Surgery on Sexual Practices. Aesthet Surg J. 2006, 26 : 12–17.

32. Goldwyn RM. The patient and the plastic surgeon. Boston: Little Brown; 1991.

33. Sarwer D, Spitzer J. Body Image Dysmorphic Disorder in Persons Who Undergo Aesthetic Medical Treatments. Aesthet Surg J. 2012, 32 : 999–1009.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine TraumatologyArticle was published in

Acta chirurgiae plasticae

2019 Issue 1-4

- Possibilities of Using Metamizole in the Treatment of Acute Primary Headaches

- Metamizole at a Glance and in Practice – Effective Non-Opioid Analgesic for All Ages

- Metamizole vs. Tramadol in Postoperative Analgesia

- Spasmolytic Effect of Metamizole

- Safety and Tolerance of Metamizole in Postoperative Analgesia in Children

-

All articles in this issue

- České souhrny

- Bilobed flap in facial reconstruction

- Free-flap monitoring: review and clinical approach

- Giant basal carcinoma on the forehead and why should prevent them - case report

- Use of medial femoral condyle flap and anterolateral thigh free flap in proxymal tibial posttraumatic non-union with multiple anastomosis - case report

- The impact of aesthetic plastic surgery on body image, body satifaction and self-esteem

- Reconstruction of deep head burn with a free flap - a case study

- Acknowledgemets to reviewers

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- About the journal

Most read in this issue

- The impact of aesthetic plastic surgery on body image, body satifaction and self-esteem

- Free-flap monitoring: review and clinical approach

- Bilobed flap in facial reconstruction

- Use of medial femoral condyle flap and anterolateral thigh free flap in proxymal tibial posttraumatic non-union with multiple anastomosis - case report