Moriarty's sign – predictor of skin graft take

Authors:

Veena W. P.; Shanthakumar S.; Kumaraswamy M.; Udayashankar O.

Authors‘ workplace:

Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, M S Ramaiah Medical College and Hospital, Bangalore, India

Published in:

ACTA CHIRURGIAE PLASTICAE, 63, 4, 2021, pp. 166-170

doi:

https://doi.org/10.48095/ccachp2021166

Introduction

Resurfacing of wound beds with split skin graft is the commonest procedure undertaken in the field of plastic surgery. The success of skin graft depends on local vascularity and wound microbiology on one side and on hemostasis and adhesion of the skin graft to the wound bed on the other side.

The fact that a successful split skin graft procedure is associated with more pain at a donor site than at a recipient site has been tacitly recognized from the early days of skin transfer but

Dr. Stark delineated in his text of 1962: “If there is no discharge from the graft or pain in the immediate area, the dressing on a graft is left undisturbed for at least a week (Moriarty’s sign); if the reverse is true, the dressing should be removed earlier [1]".

Since no further literature has been published on this aspect, keeping the clinical application in mind in terms of patient management, we felt it would be useful to popularize this simple clinical assessment of graft take, which also enabled us to decide on the day of first graft inspection.

Split skin graft adheres to its new bed by fibrin within 24–48 hours which then starts breaking down [2]. This coincides with the outgrowth of capillary buds from the recipient area that unite with those on the deep surface of the graft by 3rd day, which appears clinically as increasing pinkness in the graft. [2].

This adhesion is maintained by proliferation of fibroblasts and deposition of collagen to replace fibrin; the strength of these attachment increases quickly providing an anchorage within 4 days which allows the graft to be handled safely if reasonable care is taken.

The variation in graft thickness relates to the thickness of their dermal component and this influences the vascularity. The dermis is less vascular in its deeper part. A number of cut capillary ends exposed when a thick skin graft cut is smaller than with a thin graft and with a full thickness skin graft, there are even fewer capillary ends. Hence, the thin grafts generally get to take easier than thick grafts [3].

Rapid revascularization of graft depends on the distance to be travelled by the capillary ends from wound bed to link-up with the graft. Hence, the graft has to be in the closest possible contact with the bed. The most common cause of separation is hematoma acting as a barrier to link-up the outgrowing capillaries [4]. The graft also has to lie immobile on the bed until it firmly attaches itself. Hence, an optimized bed capable of providing the necessary capillary outgrowth to vascularize the graft is necessary for complete graft take [5].

The authors have conducted a prospective study of 100 patients, based on Dr. Stark’s observation which states the simplicity of the test to assess the pain in the donor area which can be correlated for graft take in the recipient area. Pain at the donor area is caused by exposed donor dermal cut nerve endings after skin graft harvesting. The recipient area is painless as the wound is covered. However, a negative Moriarty’s sign is also a predictor of graft failure.

The study not only validates the Moriarty’s sign but also solves the dilemma of the time of inspection of the grafted recipient site.

Methods

The authors hereby present a single center based prospective study in 100 consecutive patients in a period of 18 months between January 2014 and June 2015 at the Department of Plastic Surgery in a tertiary care centre.

Patients with varied range of age, gender, diagnosis and anatomical site of lesion were included in the study. Traumatic, infective, diabetic or post burn wounds, post tumor excisional defects, congenital defects and flap donor areas were included. Children below 5 years and full thickness grafts were excluded from the study.

All wounds were resurfaced with a split thickness skin graft. The grafts were fenestrated (meshed) except those used for face and neck areas, where sheet grafts were used. Both donor and recipient sites were dressed conventionally using non-adhesive dressing i.e. Sofra-tulle and burn mesh, respectively, covered by well-padded Gamjee rolls and crepe bandages.

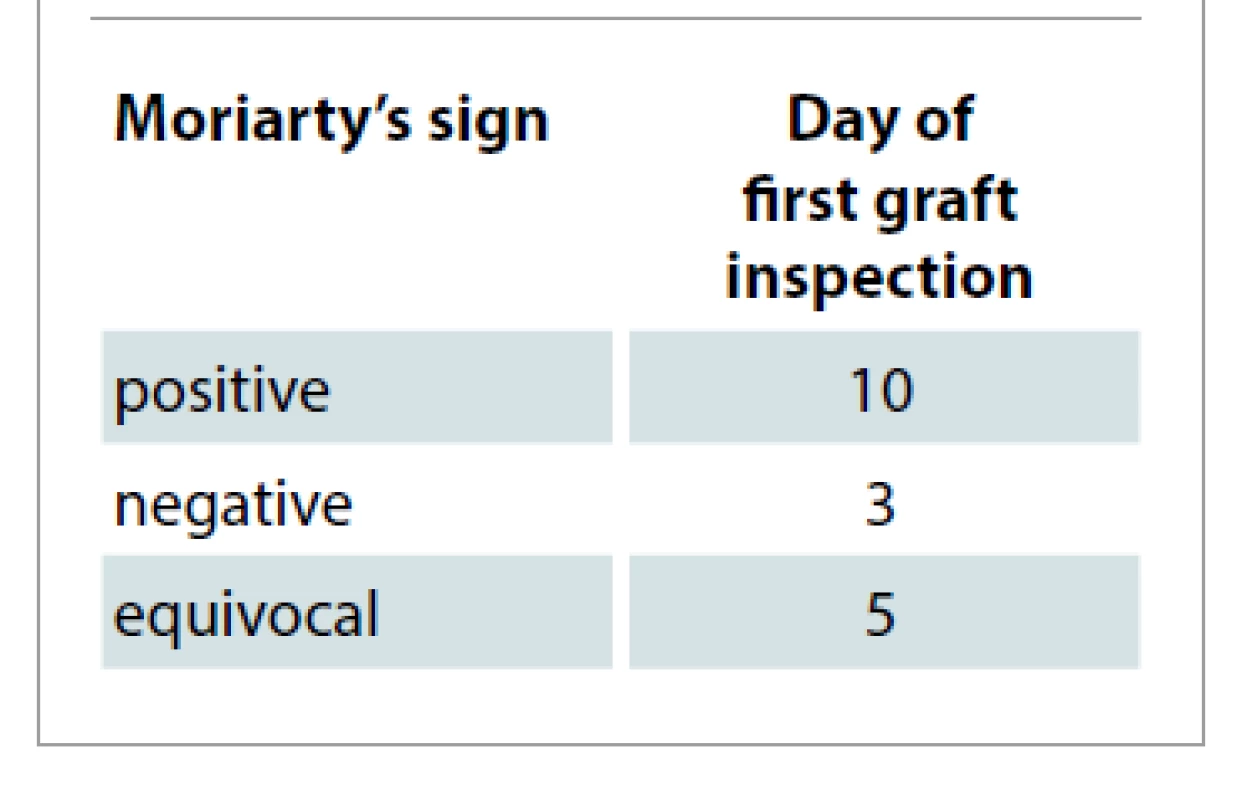

Daily enquiries were made by two surgeons who operated and the pain was assessed on a 5-point VAS scale. Detailed clinical assessment was carried out based on questions posed to the patients to elicit Moriarty’s sign. The patients with more pain in the donor area compared to recipient area were considered as Moriarty’s sign positive. Post-operatively, the recipient site was left undisturbed for 10 days (double the conventional time of 5 days) in patients with positive Moriarty’s sign. In patients with negative Moriarty’s sign, the graft was inspected on 3rd day. In patients with equivocal response grafts were inspected on 5th day. Discharge and smell were also taken into consideration for early change of dressing.

Descriptive statistics of Moriarty’s sign was summarized in terms of percentage. The patients were categorized as positive and negative based on Moriarty’s sign. The validity of predicting the graft uptake based on Moriarty’s sign was assessed by sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value.

Results

All 100 patients in the study group were questioned as to whether pain was more in the donor or recipient areas and was recorded on VAS scale. Among the cases, the average age was 42.3 ± 18.7 years; 63% were males and 37% females. The most common co-morbidities in the selected cases were diabetes (59.8%), hypertension (44.5%) and peripheral vascular disease (17.8%).

Most of the patients (67%) had wound resurfaced with split thickness skin graft (SSG) in the lower limb; next most common site was the upper limb (17%). Head and neck included 7%, trunk and abdomen 6% and 3% of patients had multiple sites.

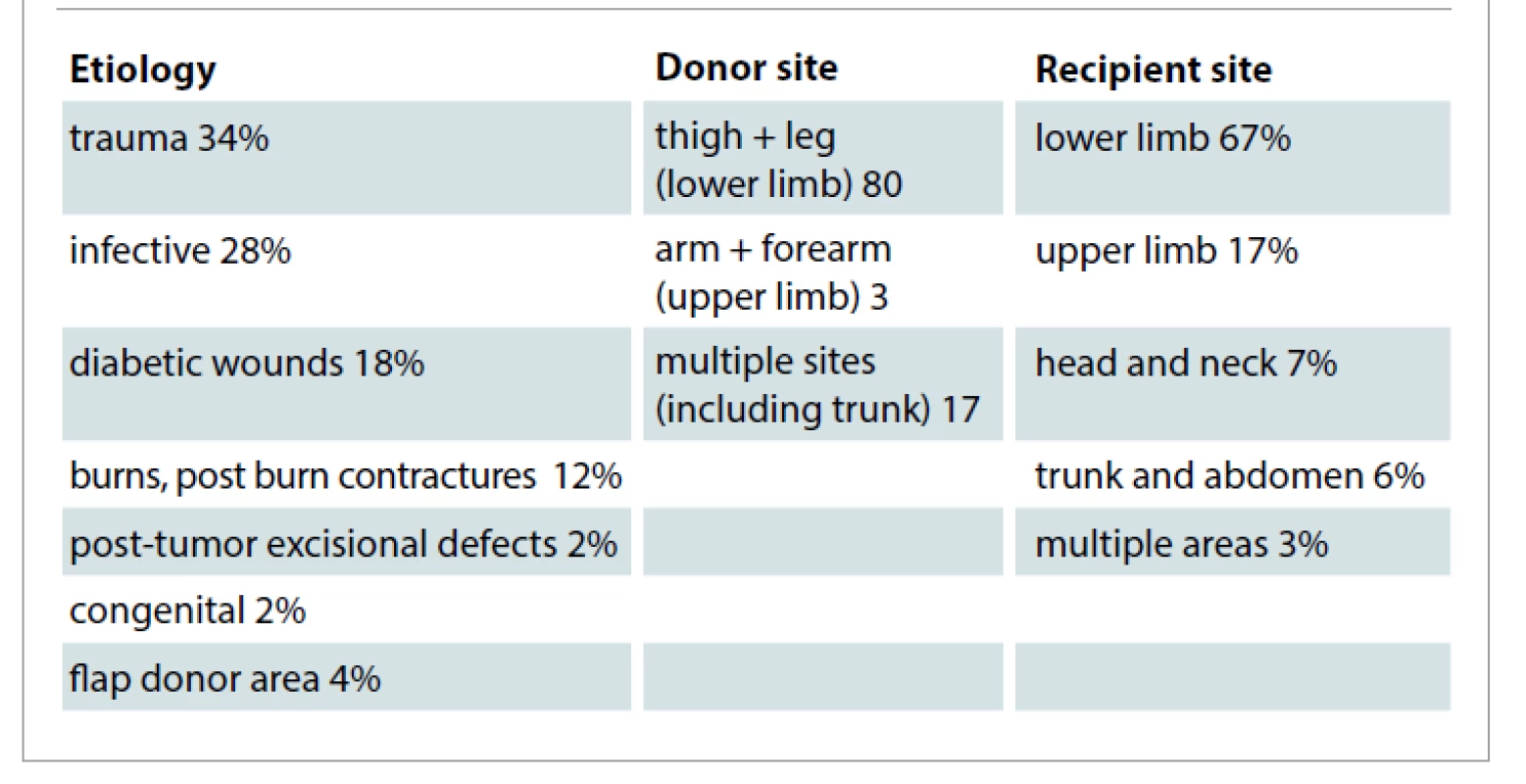

In the study, large number of wounds were of traumatic etiology followed by infective or diabetic, burns, post tumor excisional wounds or congenital and flap donor areas (Fig. 1, Tab. 1).

The authors harvested split skin graft commonly from the thigh, with other areas being upper limbs and the trunk.

The grafts were fixed to wound bed with sutures or skin staples. Autologous platelet rich plasma was also applied on the wound bed as an adhesive in many patients [6].

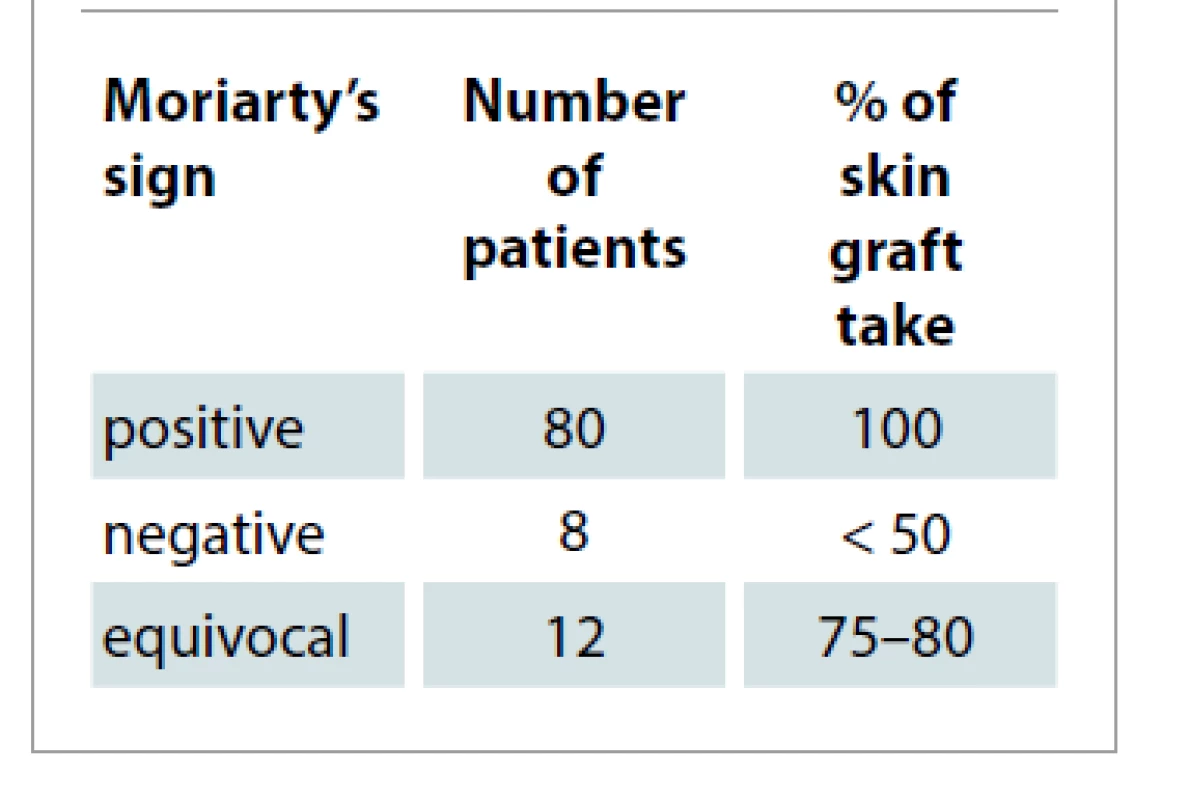

Pain at both donor and recipient sites were compared for 10 days post-operatively. Graft take was assessed qualitatively by clinical observation. In 80%, the patients with positive Moriarty’s sign had their first graft inspection on 10th day with 100% graft take (Tab. 2). In patients with negative Moriarty’s sign, first dressing was changed as early as 3rd day with graft uptake less than 50%, and 12% of patients in whom the response was equivocal had first dressing changed on 5th day with 75–80% graft take. Discharge and smell were also taken in to consideration for early dressing change in both donor and recipient areas.

Moriarty’s sign positive patients underwent graft inspection on 10th day as the dressings were dry and there was no smell (Fig. 2, 3).

In patients with strongly negative Moriarty’s sign, graft inspection was done as early as on the 3rd day, as by that time the graft would have adhered to the wound bed [2]. Here the loss was due to hematoma, infection and shearing (neck and trunk region due to unwarranted movement by the patients). Patients with equivocal response underwent graft inspection conventionally on 5th day and the graft loss was due to seroma and mild infection (Tab. 3).

It is noted that all patients with positive Moriarty’s sign had a positive graft uptake indicating high sensitivity and specificity for clinical outcome evaluation.

Discussion

This study confirms the usefulness of Moriarty’s sign as simple bedside clinical test which gives reliable information about the graft take. The population includes different age groups, ranging from 9–74 years. In our series, post-traumatic skin loss, acute burns, post burn contracture release and flap donor sites were the indications for SSG. The most common donor sites were thighs, arms and trunk. The grafts were fixed to wound bed with sutures or skin staples. Autologous platelet rich plasma was also applied on the wound bed in many patients as an alternative to adhere the graft [6]. The test was applied in our sample study to all sizes of split thickness skin grafts except full thickness skin grafts.

The test was applied from the 1st post-operative day. The dressings are conventionally changed for the first time by 5 days after skin grafting [7]. In our study, first graft inspection was done on 10th post-operative day, in all patients with positive Moriarty’s sign. In patients with equivocal and negative response, early dressings were undertaken (Fig. 4).

It was observed that the graft take was 100% in patients with strongly positive Moriarty’s sign.

Frequent causes of graft loss are [8] seroma, hematoma which separates grafts from the bed, shearing movements which prevent adhesion between the graft and its bed and infection [9–11].

In our study, in patients with equivocal response (12%), the graft loss was due to seroma formation and mild infection. In patients with negative Moriarty’s sign (8%), the graft loss was due to hematoma, infection and shearing (neck and trunk region due to unwarranted movement by the patients).

The cutting of SSG leaves variable portion of pilosebaceous apparatus and sweat glands in the donor area. The epithelium regenerates and spreads from multiple foci until the area is resurfaced with skin. The remnants of pilosebaceous apparatus are much more active as foci of epithelial regeneration than sweat gland remnants, which react sluggishly.

The donor site of a thin graft with its full complement of cut pilosebaceous follicle heals in approx. 7–9 days, while the donor site of a thick graft depending virtually entirely on sweat gland remnants heals more slowly, with healing time of 14 days or more [7].

Traditionally, the donor areas were dressed with Sofra-tulle over which absorbent gauze was laid and held in position with crepe bandages [12,13]. The dressing of donor area in our patients was left in situ until it got separated spontaneously; an approach which is practical if it remained dry.

This study demonstrates that Moriarty’s sign is not only an excellent predictor of graft take but can also be used as a determinant for the time of graft inspection. There were relatively few patients in the failure category (8%).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that Moriarty’s sign is a reliable clinical predictor of split thickness skin graft take and may be useful as a guide to determine the day of the first graft inspection. It is an effective method for even the junior members of the surgical and nursing team to monitor the parameters in relation to this sign. It can be practiced in smaller group of hospitals, too. Its clinical application helps to reduce the discomfort and cost of frequent changes of dressing, time and man power, especially in busy clinical units.

Hence, the authors recommend to integrate this clinical assessment in routine practice.

Role of authors: All authors have been actively involved in the planning, preparation, analysis and interpretation of the findings, enactment and processing of the article with the same contribution.

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors declare that this study has received no financial support. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. An informed written consent was obtained from all patients.

Dr. S. Shanthakumar

Associate professor

Department of Plastic Surgery

M S Ramaiah Medical College

and Hospital Bangalore

Karnataka

India

e-mail: shanthakumarshivalingappa@gmail.com

Submitted: 5.6.2021

Accepted: 30.8.2021

Sources

1. Birchall MA., Varma S., Milward TM. The Moriarty’s sign: an appraisal. Br J Plast Surg. 1991; 44(2): 149–150.

2. Mc Gregor AD., Mc Gregor IA. Fundamental techniques of plastic surgery and their surgical applications. 10th ed. Churchill Livingstone publication 2000; 36.

3. Thornton JF., Gosman AA. Skin grafts and skin substitutes. Selected Readings in Plastic Surgery 2004; 10(1).

4. Mathes SJ (ed). Mathes Plastic Surgery. Saunders Elsevier publication 2006; 312.

5. Aston SJ., Beasley RW., Thorne CH. Grabb and Smith’s plastic surgery. 5th ed. Lippincott Raven publication1997; 18.

6. Veena PW., Shanthakumar S. Comparison between conventional mechanical fixation and use of autologous platelet rich plasma in wound beds prior to resurfacing with split thickness skin graft. [online]. Available from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5f88/eb758d505006a3fa7f198b0276a6741055a5.pdf?_ga=2.134365873.158388215.1635142816-615204396.1635142816.

7. Neligan PC. (ed). Plastic Surgery. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders 2013; 330.

8. Guyuron B., Eriksson E., Persing JA. Plastic surgery: indications and practice. Saunders Elsevier 2009; 102.

9. Sakir Ü., Gülden E., Ferit D., et al. Analysis of skin-graft loss due to infection: infection-related graft loss. Ann Plast Surg. 2005, 55(1): 102–106.

10. Pruitt BA. Jr., McManus AT., Kim SH., et al. Burn wound infections. World J Surg. 1998; 22(2): 135–145.

11. Krizek TJ., Robson MC. Evolution of quantitative bacteriology in wound management. Am J Surg. 1975; 130(5): 579–584.

12. Barnea Y., Amir A., Leshem D., et al. Clinical comparative study of aquacel and paraffin gauze dressing for split-skin donor site treatment. Ann Plast Surg. 2004; 53(2): 132–136.

13. Voineskos, SH., Ayeni OA, McKnight L., et al. Systematic review of skin graft donor-site dressings. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 124(1): 298–306.

Labels

Plastic surgery Orthopaedics Burns medicine TraumatologyArticle was published in

Acta chirurgiae plasticae

2021 Issue 4

- Possibilities of Using Metamizole in the Treatment of Acute Primary Headaches

- Metamizole at a Glance and in Practice – Effective Non-Opioid Analgesic for All Ages

- Metamizole vs. Tramadol in Postoperative Analgesia

- Spasmolytic Effect of Metamizole

- Safety and Tolerance of Metamizole in Postoperative Analgesia in Children

-

All articles in this issue

- Editorial

- Moriarty's sign – predictor of skin graft take

- Fractional CO2 laser therapy of hypertrophic scars – evaluation of efficacy and treatment protocol optimization

- Anterior open bite – diagnostics and therapy

- Cyanide poisoning in patients with inhalation injury – the phantom menace

- Cooperation of the maxillofacial and plastic surgeon in reconstructive surgical procedures in gunshot injury – a case report

- Surgical treatment and management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in patients with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa – a case report

- Combined fungal and bacterial infection in deep burns of the lower limb – a case report

- Celebrating the career and retirement of Dr Hana Řihová

- Acta chirurgiae plasticae

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- About the journal

Most read in this issue

- Anterior open bite – diagnostics and therapy

- Fractional CO2 laser therapy of hypertrophic scars – evaluation of efficacy and treatment protocol optimization

- Cyanide poisoning in patients with inhalation injury – the phantom menace

- Moriarty's sign – predictor of skin graft take