Pitfalls in screening for gestational diabetes in the Czech Republic – patient survey

Úskalí screeningu gestačního diabetu v České republice – průzkum mezi pacienty

Cíl:

Cílem naší studie bylo prozkoumat, jak probíhá screening gestačního diabetu v České republice s ohledem na správnost metodických postupů screeningu.

Metodika:

Celkem 1100 anonymních dotazníků bylo rozdáno těhotným ženám v prenatální poradně Gynekologicko-porodnické kliniky 1. LF UK a VFN v Praze v období od července do září 2015.

Výsledky:

958 (87,0 %) dotazníků bylo možno analyzovat; 794 (82,9 %) dotazovaných mělo alespoň jeden rizikový faktor pro vznik GDM. OGTT byl proveden u 751 (94,6 %) žen, s rizikovými faktory pro GDM a 153 (93,3 %) žen s nízkým rizikem rozvoje GDM. Z 904 provedených oGTT bylo 154 (17,0 %) provedeno zcela podle doporučených postupů. Ve zbývajících případech byla zaznamenána alespoň jedna metodická chyba. Výsledky oGTT poskytlo 364 (40,3 %) respondentů. V této skupině mělo 71 (19,5 %) žen pozitivní screening GDM podle kritérii Mezinárodní asociace pro studium diabetu v těhotenství (IADPSG). Většinou to však nebyly ty ženy, které byly gynekologem označeny jako screening pozitivní.

Závěr:

Screening GDM nebyl často proveden v souladu s doporučeným postupem a použitá diagnostická kritéria nebyla jednotná.

Klíčová slova:

gestační diabetes mellitus, screening, orální glukózový toleranční test, glykémie nalačno, průzkum

Authors:

Patrik Šimják 1

; Kateřina Anderlová 1,2

; Hana Krejčí 1,2

; Vratislav Krejčí 1

; P. Pařízková 3; M. Mráz 4,5; M. Kršek 6; M. Haluzík 4,5,7,8

; A. Pařízek 1

Published in:

Ceska Gynekol 2018; 83(5): 348-353

Category:

Overview

Objective:

The aim of our survey was to investigate gestational diabetes (GDM) screening policy in the Czech Republic with regards to the correct methodology of the screening.

Materials and methods:

1100 anonymous questionnaires were distributed among patients of a tertiary level obstetric department from July 2015 to September 2015.

Results:

958 (87.0%) questionnaires were found eligible for analysis. 794 (82.9%) of participants had at least one risk factor for GDM development. The oGTT was performed in 751 (94.6%) women at risk of GDM and 153 (93.3%) women at low risk of GDM. From the 904 performed oGTT, 154 (17.0%) were performed completely by recommended standards. In the remaining cases, at least one deviation from standard was noted. The results of oGTT were provided by 364 (40.3%) of respondents. In this subgroup, 71 (19.5%) matched International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group‘s (IADPSG) criteria for GDM diagnosis. However, these women were often not those who were evaluated as screening positive by the office gynaecologist.

Conclusion:

The screening for GDM was frequently not performed in accordance with the national guidelines and the diagnostic criteria used were not uniform.

Keywords:

gestational diabetes mellitus, screening, oral glucose tolerance test, fasting blood glucose, survey

INTRODUCTION

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a carbohydrate intolerance resulting in hyperglycaemia that is first recognized during pregnancy [22]. In addition to known perinatal complications associated with GDM, such as fetal macrosomia, shoulder dystocia and birth injury, evidence suggesting long-term consequences for both mother and children accumulate. Women who had GDM have markedly increased risk of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) within first five years postpartum and up to 60% lifetime risk of developing diabetes [13]. Infants born from pregnancies complicated by GDM are at increased risk of obesity [9], T2DM [4], cardiovascular diseases [3, 23] and neuropsychiatric morbidity [18]. Proper management of GDM during pregnancy and postpartum lifestyle interventions may be beneficial to both the mothers and the offspring, although currently there is no convincing evidence of impact on future metabolic status of the newborn [6, 11, 12]. Nevertheless, effective screening in pregnancy is necessary for initiating treatment.

Screening for GDM has been a topic of debate for years and different screening strategies are being used over the world [19]. Formerly, the screening in the Czech Republic followed the recommendations of the World Health Organization [22]. In 2015, Czech Diabetes Society and Czech Gynecological and Obstetrical Society came to a mutual consensus and national guidelines for screening and management of GDM in reaction to IADPSG recommendations have been issued [2, 15].

In the Czech Republic, the screening for GDM is administered by the office gynaecologists, who either refer pregnant women to laboratory or perform the screening in the office settings. Until the new national guideline was issued in 2015, the screening was selectively aimed at women at risk of developing GDM [22]. The current guidelines recommend to screen the entire pregnant population except for those with already known impairment of glucose metabolism as the risk-based screening can miss up to half of the GDM cases [10]. First, it is necessary to rule out women with unrecognized pregestational diabetes, because it represents different risks, including increased risk of congenital malformations, and requires different management [1, 16]. Therefore fasting blood glucose should be assessed in the first trimester. Unless the result is positive, women undergo standard 75g, 2-hour oGTT in the second trimester. The test should be performed at 24–28 weeks of gestation and is carried out under standard laboratory conditions with respect to factors potentially altering the results [20]. After at least 8 hours of fasting, venous blood is obtained and blood glucose is measured prior glucose challenge. As soon as the result of fasting blood glucose is available and is negative, women undergo standard glucose challenge during which venous blood glucose is measured after one and two hours. Immediate processing of the samples or usage of tubes containing effective glycolysis inhibitor is necessary for minimizing glycolysis. Women should restrain excessive activity during the test as it can alter the results. With regards to possible adverse effects of the challenge, such as nausea and vomiting, women should not be allowed to leave the laboratory during the test. Finally, the new guideline recommends using diagnostic cut-off values for 75g, 2-hour oGTT proposed by IADPSG [15]. These replaced former cut-off values suggested by the WHO [22]. In addition to former recommendation, plasma glucose after 1 hour from glucose challenge needs to be assessed as well.

It is well known that the incidence of gestational diabetes is influenced by the chosen cut-offs [21]. However, less emphasis is placed on prior patient education and actual execution of screening although these have the potential impact as well [7]. To this end, our research focused on the performance of screening for GDM in the Czech Republic. The aim of our patient survey was to investigate whether the screening for gestational diabetes in the Czech Republic is done in all eligible patients and whether the correct methodology and appropriate cut-offs are being applied. Furthermore, we tried to estimate how deviations from the recommended protocol can impact the reported incidence of GDM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was performed at a single, regional tertiary level obstetric department with approximately 4800 births every year. An anonymous questionnaire intelligible for pregnant women was designed to assess whether screening for GDM in the Czech Republic is done in accordance with new national guideline. The survey was conducted from July 2015 to September 2015. The set of 1100 questionnaires was given to every patient who attended predelivery pregnancy counseling at our obstetric department starting at 36 to 37 weeks of gestation. Filled anonymous questionnaires were then handed in when the women were admitted to the hospital for labour. All of the questionnaires were then checked for completeness and logical mistakes. Incomplete or unclear questionnaires or those containing inconsistent answers were excluded from analysis. The rest were analysed using XLSTAT–Biomed.

RESULTS

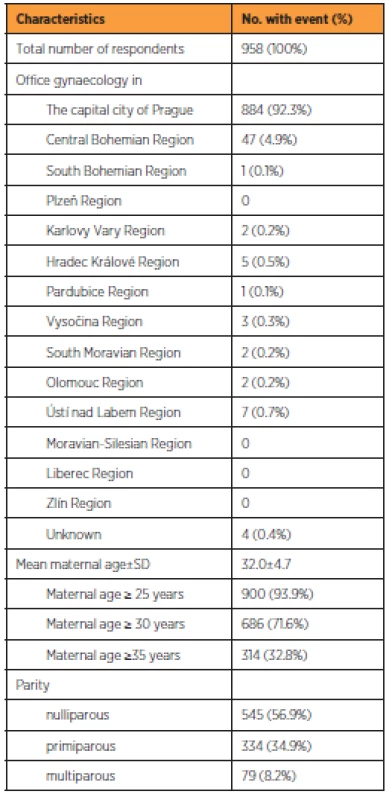

During the observation period, 958 (87.0%) completed questionnaires were found eligible for analysis. Table 1 shows the characteristics of respondents. The majority attended gynaecological offices in Prague (884; 92.3%), followed by the Central Bohemian region (47; 4.9%). The other regions of the Czech Republic were negligibly represented. The mean age of participants was 32.0±4.7 years. The majority of respondents were nulliparous (545; 56.9%). One previous delivery was reported by 334 (34.9%) women and more than one by 79 (8.2%) women.

Population screened

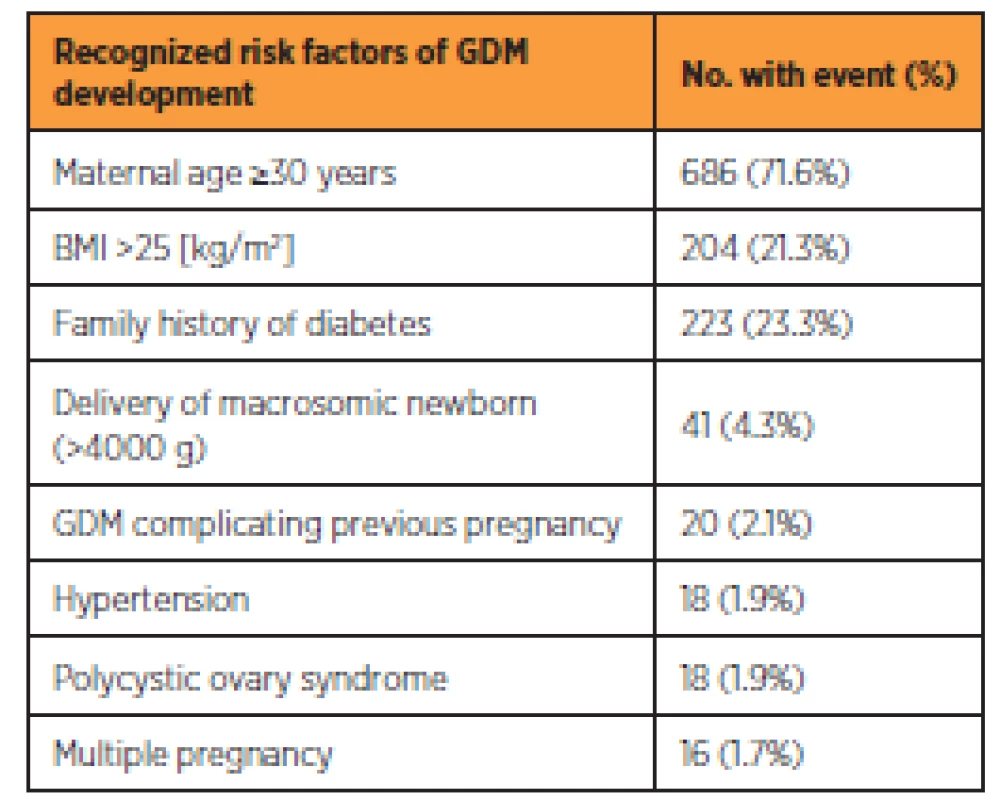

Table 2 shows the incidence of risk factors for GDM among the respondents. The three most common risk factors among the respondents were maternal age of 30 years or more (346; 36.1%), family history of diabetes (223; 23.3%) and BMI of more than 25 (204; 21.3%). From the entire group, 794 (82.9%) women had at least one risk factor for developing GDM, whereas 164 (17.1%) did not have any risk factor. The oGTT was performed in 751 (94.6%) and 153 (93.3%) women with at least one risk factor and without any risk factor respectively. Overall 904 (94.4%) of women had oGTT performed.

Methodological performance of screening for GDM

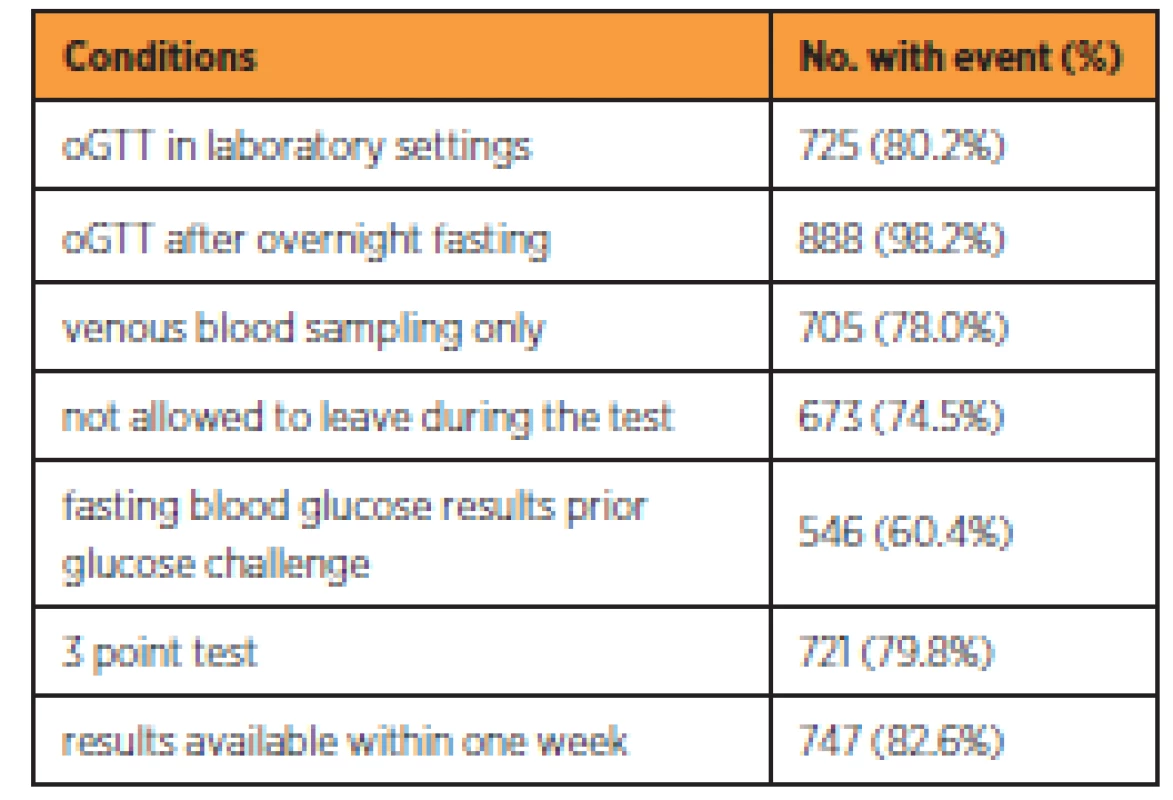

In the studied cohort 430 (44.9%) women reported having fasting blood glucose measured in the first phase of GDM screening in the first trimester. Overall 904 (94.4%) of women had oGTT performed, from which 121 (12.6%) had it in the first half of pregnancy, 848 (88.5%) in the second half and 65 (6.8%) had oGTT performed twice during pregnancy. Despite the recommendation of their physician, 19 (2.0%) women refused oGTT. Table 3 shows the number and percentage of oGTT correctly performed for each methodologic condition.

From the 904 performed oGTT, 725 (80.2%) were performed in the settings of an accredited laboratory. The majority of women (888; 98.2%) underwent the test after overnight fasting. The most common deviations from recommended protocol were administering glucose solution before knowing the results of fasting blood glucose (358; 39.6%), leaving the laboratory during the test and returning for blood sampling (231; 25.6%), replacing venous blood sampling with the capillary blood sampling (199; 22.0%) and not performing 3 point test (183; 20.2%). The women were informed about the results of the test within one week in the majority of cases (747; 82.6%). It can be concluded that 154 tests (17.0%) were performed completely by recommended standards. In the remaining cases, at least one deviation from standards was noted.

Diagnostic criteria

The office gynaecologists evaluated 56 (6.2 %) oGTTs as positive in either first or second half of the pregnancy. All women with positive oGTT were referred to diabetology. Above that, gynaecologists evaluated another 39 (4.3%) of oGTT results as borderline. However, management of these cases was not uniform. Of these so-called borderline cases, 19 (48.7%) were referred to diabetologist and the rest of the women was not.

The results of the oGTT were provided by 364 respondents (40.3%). The new diagnostic cut-off criteria were applied. Of the 364 known results, 71 (19.5%) matched criteria for GDM diagnosis. Positive fasting blood glucose, 60 and 120 minutes glycaemia were found in 44 (62.0%), 22 (31.0%) and 11 (15.5%) of tests, respectively. In 65 (91.5%) of positive oGTTs, there was only one glycemia above threshold for GDM diagnosis.

From those, who were positive according to the new guidelines, 49 (69.0%) were referred to diabetologist. On the contrary 2 (0.7%) had received unnecessary diabetology care despite negative results according to the new diagnostic criteria.

DISCUSSION

Our results show current practice of GDM screening based on information from a representative sample of pregnant women attending our clinic. To our knowledge, this is the first survey that aims to evaluate current practice of the screening for GDM based on information obtained from pregnant women and not from healthcare professionals.

There has been no selection of the population as every woman attending antenatal counseling during study period had been given a questionnaire to participate. The limitation of our study is that it predominantly reflects the GDM screening policy in the capital city of Prague and Central Bohemian Region. The screening policy can differ in other regions of the Czech Republic, due to the access to healthcare.

It is well documented, that the prevalence of GDM is affected by the population screened and by the chosen approach [21]. However, methodology can also have an impact on the results [7]. Some of the information regarding the process of screening can only be given by women themselves. These include fasting prior the test, capillary blood sampling instead of venous blood sampling and physical activity during the test. Health care professionals might give inaccurate data because they routinely do not obtain this information. Therefore the survey was addressed to pregnant women, keeping in mind that the reliability of the data is influenced by the understanding of the questions based on an educational level. The reliability of the data can also be affected by the fact, that women had to recall the screening procedure in the current pregnancy. Despite these limitations, 958 (87.0%) questionnaires were filled in completely and were found eligible for analysis.

Our results show more than 90% of women undergo oGTT during pregnancy. This applies to both women at increased risk of developing GDM and the low-risk population.

The assessment of fasting blood glucose should be routinely performed in the first trimester [1]. However, a surprisingly low number of women in both groups reported having it done. It is essential for diagnosing unrecognized prepregnancy impairment of glucose metabolism. Presumably, the participating women were often not aware of it being performed together with other blood tests in the first trimester of pregnancy.

Methodological deviations in performance of oGTT were common. Nearly all women complied with at least 8-hour fasting before oGTT. This standard period of fasting prior the test is important since fasting glycemia of the same individual can vary significantly, and the screening is highly sensitive to incorrect preparation phase [1]. The survey proves that 179 (19.8%) of oGTT are carried out in an office gynaecology settings instead of accredited laboratories. This has further implications, because the equipment for immediate assessment of glucose from venous blood is often lacking. Therefore in this settings replacing venous blood sampling by capillary blood sampling and bedside analysis of the sample is a common practice. This has an impact on the results as random and fasting venous blood glucose are higher than capillary blood glucose but lower for sampling 2 hours after oral glucose administration [5]. A way to overcome this in office settings is to perform venous sampling and transport the sample to the laboratory, however, there is a risk of delay. Unless the samples are analyzed immediately, the blood glucose values would become inaccurate [8]. Also, in these settings women were more frequently allowed to leave and come back for next blood sampling, resulting in physical activity. Physical aerobic activity has the potential effect on glucose metabolism and can alter the results [14]. IADPSG suggests 3-point oGTT and single value above the threshold is sufficient for diagnosing GDM. However, 183 (20.2%) respondents stated, that glycaemia was measured less than three times. 60-minutes glycaemia was omitted in these cases. 60-minutes glycaemia was the only single positive value of oGTT in 17 (23.9%) and so it importantly contributes to diagnosis and cannot be neglected.

From the results of the oGTT provided by the respondents, it can be concluded, that the new cut-off values suggested by IADPSG were not generally applied at the time of the study. Despite the new national guideline, the gynaecologists often used previous diagnostic criteria suggested by WHO [22]. Therefore women diagnosed with GDM by office gyneacologists were often not those who met new diagnostic criteria for GDM and it was also reflected in care provided. The false positivity rate of screening carried out this inconsistent way was 0.05 and false negativity rate was 0.22.

An important finding of our survey is, that 44 (62.0%) of GDM cases were diagnosed from fasting blood glucose without the necessity of glucose challenge. In these cases the administration of glucose is improper. Obtaining fasting blood glucose results prior drinking the glucose solution could prevent unnecessary and burdensome glucose challenge in many cases.

According to information provided by the subjects, 1 in 5 oGTT is completely done according to recommended standards of the test. The results also raise doubts about applying the cut-off criteria suggested by the IADPSG instead of the previous WHO criteria. Altogether these deviations from standard screening protocol influence the incidence of GDM but more importantly treatment of the condition in the individual woman.

Taken together, our survey has shown that deviations from standard screening process are frequent in Prague and the Central Bohemian region of the Czech Republic. A similar situation can be expected in other regions of the Czech Republic and probably in other countries as well. The new national guideline was often not followed by the health care professionals, insufficient attention was given to the correct methodological performance of the oGTT and applied diagnostic criteria were not uniform at the time of the survey. Incorrect screening eclipses true incidence of GDM and leads to improper management with potentially serious consequences. The pursuit for standard screening process on national and international level should be one of the priorities in obstetrics given the increasing incidence of GDM. Without this unification, it is hard to apply results of studies concerning GDM on population screened differently.

Correspondence:

MUDr. Kateřina Anderlová, Ph.D.

Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics

and 3rd Department of Medicine

First Faculty of Medicine Charles University

General University Hospital

Apolinářská 18

128 08 Prague

e-mail: kanderlova@centrum.cz

Acknowledgments: We thank our colleagues from Czech Society of Midwives who provided assistance in promoting the survey and collecting data.

This research was supported by the Czech Health Research Council (NV 15-27630A).

Sources

1. American Diabetes Association. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2017, 40, suppl. úůp1, p. 11–24.

2. Andelova, K., Anderlova, K., Cechurova, D., et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus – guideline. 2015. Retrieved from http://www.prolekare.cz/en/czech-gynaecology-article/gestacni-diabetes-mellitus-doporuceny-postup-57027.

3. Boney, CM., Verma, A., Tucker, R., Vohr, BR. Metabolic syndrome in childhood: association with birth weight, maternal obesity, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics, 2005, 115(3), p. 290–296.

4. Clausen, TD., Mathiesen, ER., Hansen, T., et al. Overweight and the metabolic syndrome in adult offspring of women with diet-treated gestational diabetes mellitus or type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2009, 94, p. 2464–2470.

5. Colagiuri, S., Sandbaek, A., Carstenten, B., et al. Comparability of venous and capillary glucose measurements in blood. Diabet Med, 2003, 20, p. 953–956.

6. Crowther, CA., Hiller, JE., Moss, JR., et al. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Eng J Med, 2005, 352, p. 2477–2486.

7. Daly, N., Flynn, I., Carrol, C., et al. Impact of implementing preanalytical laboratory standards on the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective observational study. Clin Chem, 2016, 62, p. 387–391.

8. Daly, N., Stapleton, M., O’Kelly, R., et al. The role of preanalytical glycolysis in the diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus in obese women. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2015, 213(1), p. 84.e1–84.e5.

9. Desai, M., Beall, M., Ross, MG. Developmental origins of obesity: programmed adipogenesis. Curr Diab Rep, 2013, 13, p. 27–33.

10. Griffin, ME., Coffey, M., Johnson, H., et al. Universal versus risk factor based screening for gestational diabetes mellitus detection rates, gestation at diagnosis and outcome. Diabet Med, 2000, 17, p. 26–32.

11. Guo, J., Chen, JL., Whittemore, R., Whitaker, E. Postpartum lifestyle interventions to prevent type 2 diabetes among women with history of gestational diabetes: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J Womens Health, 2016, 25, p. 38–49.

12. Hartling, L., Dryden, DM., Guthrie, A., et al. Benefits and harms of treating gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the National Institutes of Health Office of Medical Applications of Research. Ann Intern Med, 2013, 159, p. 123–129.

13. Kim, C., Newton, KM., Knopp, RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 2002, 10, p. 1862–1868.

14. Knudsen, S., Karstoft, K., Pedersen, BK., et al. The immediate effects of a single bout of aerobic exercise on oral glucose tolerance across the glucose tolerance continuum. Physiological Reports, 2014, 2(8), p. e12114.

15. Metzger, BE., Gabbe, SG., Persson, B., et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care, 2010, 33, p. 676–682.

16. Mills, JL. Malformations in infants of diabetic mothers. Birth defects research. Part A. Clin Molecular Teratol, 2010, 88(10), p. 769–778.

17. Mooy, JM., Grootenhuis, PA., deVries, H., et al. Intra-individual variation of glucose, specific insulin and pro–insulin concentrations measured by two oral glucose tolerance tests in a general Caucasian population; The HOORN Study. Diabetologia, 1996, 39, p. 298–305.

18. Nahum Sacks, K., Friger, M., Shoham-Vardi, I., et al. Prenatal exposure to gestational diabetes mellitus as an independent risk factor for long-term neuropsychiatric morbidity of the offspring. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2016, 215(3), p. 380.e1–380.e7.

19. Petrovic, O., Belci, D. A critical appraisal and potentially new conceptual approach to screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes. J Obstet Gynaecol, 2017, 37(6), p. 691–699.

20. Sacks, DB., Arnold, M., Bakris, GL., et al. Guidelines and recommendations for laboratory analysis in the diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus. Clin Chem, 2011, 57, p. e1–e47.

21. Shirazian, N., Mahboubi, M., Emdadi, R., et al. Comparison of different diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus based on the 75-g oral glucose tolerance test: a cohort study. Endocrine Practice, 2008, 14(3), p. 312–317.

22. World Health Organization. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications: report of a WHO consultation, part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. 1999. 2nd ed.

23. Wu, CS., Nohr, EA., Bech, BH., et al. Long-term health outcomes in children born to mothers with diabetes: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One, 2012, 7, p. e36727.

Labels

Paediatric gynaecology Gynaecology and obstetrics Reproduction medicineArticle was published in

Czech Gynaecology

2018 Issue 5

-

All articles in this issue

- HCG level after embryo transfer as a prognostic indicator of pregnancy finished with delivery

- Advance maternal age – risk factor for low birhtweight

- Eating disorders in pregnancy

- Factors affecting the uterine sarcomas developement and possibilities of their clinical diagnosis

- Vaginal microbiome

- The effect of polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorinated pesticides on human reproduction

- Pelvic actinomycosis and IUD

- Screening and the diagnostics of the gestational diabetes mellitus

- Gestational diabetes mellitus

- Effects of cervical cerclage on cervical length and the impact of changes in cervical length on pregnancy prognosis

- Pitfalls in screening for gestational diabetes in the Czech Republic – patient survey

- Consecutive intrapartum uterine rupture following endoscopic resection of deep rectovaginal and bladder endometriosis

- Czech Gynaecology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- About the journal

Most read in this issue

- HCG level after embryo transfer as a prognostic indicator of pregnancy finished with delivery

- Vaginal microbiome

- Pelvic actinomycosis and IUD

- Eating disorders in pregnancy