Alveolar echinococcosis – a rare disease with differential diagnostic problems

Alveolární echinokokóza – vzácné onemocnění s problematickou diferenciální diagnostikou

Úvod:

Alveolární echinokokóza je vzácné a závažné zoonotické parazitární onemocnění.

Kazuistika:

Autoři demonstrují případ mladého nemocného s postižením jater, bránice a plic touto formou infekce. Diagnóza echinokokové infekce byla stanovena na základě anamnézy, klinické symptomatologie v kombinaci s USG, CT, MRI a sérologickými metodami. Byla provedena radikální bloková resekce 7. jaterního segmentu, dolního plicního laloku vpravo a bránice. Definitivní stanovení diagnózy alveolární echinokokózy bylo provedeno histopatologicky a pomocí PCR metody ze vzorku resekované tkáně.

Závěr:

Nemocný je 8 měsíců po operaci bez potíž, trvale dispenzarizován s long-life terapií albendazolem.

Klíčová slova:

alveolární echinokokóza – diagnostika – léčba - dispenzarizace

Authors:

V. Třeška; L. Kolářová; H. Mírka; O. Daum; J. Matějů; V. Liška; A. Koubová; D. Sedláček

Authors‘ workplace:

Clinic of Surgery, MF Charles University, Teaching Hospital in Pilsen

Head of Department: prof. MUDr. V. Treska, DrSc.

1; National Reference Laboratory, Institute of Immunology and Microbiology, 1st MF Charles University, Prague

Head of Department: prof. RNDr. L. Kolarova, CSc.

2; Clinic of Radiodiagnostics, MF Charles University, Teaching Hospital in Pilsen

Head of Department: prof. MUDr. B. Kreuzberg, CSc.

3; Sikl´s Institute of Pathology, MF Charles University, Teaching Hospital in Pilsen

Head of Department: prof. MUDr. M. Michal, PhD.

4

Published in:

Rozhl. Chir., 2016, roč. 95, č. 6, s. 240-244.

Category:

Case Report

Overview

Introduction:

Alveolar echinococcosis is a life-threatening zoonotic parasitic disease. Its incidence is rare. In some cases, the correct and timely diagnosis can be difficult.

Case report:

The authors present the case of a young patient with liver, diaphragm and lung involvement. The suspicion of echinococcus infection was made on the basis of medical history, clinical symptoms, and a combination of ultrasonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging tests and serological methods. The patient underwent multimodal treatment with albendazole and en-bloc resection of the liver, lung and diaphragm. The definitive diagnosis of alveolar echinococcosis was determined from samples of the resected tissues using histopathology and polymerase chain reaction methods. The patient has been followed regularly and is on life-long treatment with albendazole.

Conclusion:

The precise diagnosis and multimodal therapy of alveolar echinococcosis is fundamental from the point of view of patient long-term survival.

Key words:

alveolar echinococcosis – diagnosis – multimodal treatment – follow-up

Introduction

Alveolar echinococcosis (AE) is a rare and prognostically serious zoonotic parasitic disease caused by the larval stages of the Echinococcus multilocularis (alveococcus) tapeworm. Humans are infected following ingestion of the parasite´s eggs that live in the gastrointestinal tract of carnivores, especially foxes. Human infection is characterised by a long incubation period (5−15 years) and in up to 95% of untreated patients, AE can be fatal within 10 years of diagnosis [1].

This disease has been documented in the northern hemisphere, whereby at the end of the last century, it was reported in Austria, Switzerland, southern Germany and the eastern parts of France. From the end of the last century, we have recorded an increasing number of cases, not only in the aforementioned regions but also in other European countries [2]. The increased incidence of this disease is probably due to the growing fox population as a consequence of rabies vaccination [3]. In the Czech Republic, this disease remains rare, with around two cases being recorded annually since 2007 [4,5].

The low number of AE cases diagnosed to date in our country may lead to differential diagnostic problems when determining the correct and timely diagnosis. This is why we present here the case of a young patient with a large AE infiltration involving the right liver lobe, diaphragm and lung.

Case report

The 21-year old patient was referred to the Pneumonology Department of another hospital for pain of the right hemithorax occurring on deep inspiration at the end of 2014. He had visited Egypt as a tourist in 2011 and 2012, but had not travelled abroad otherwise.

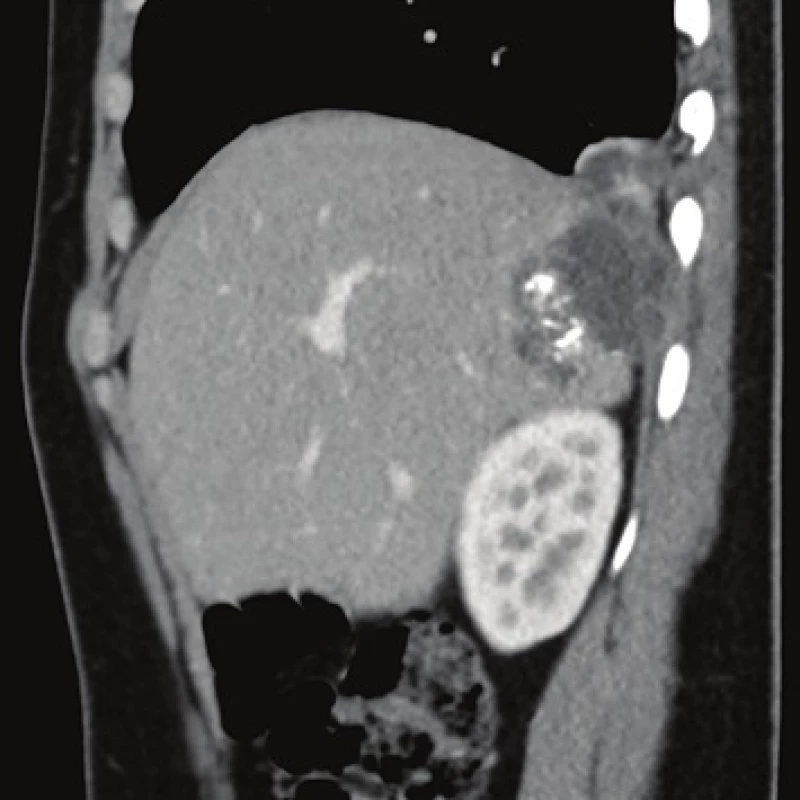

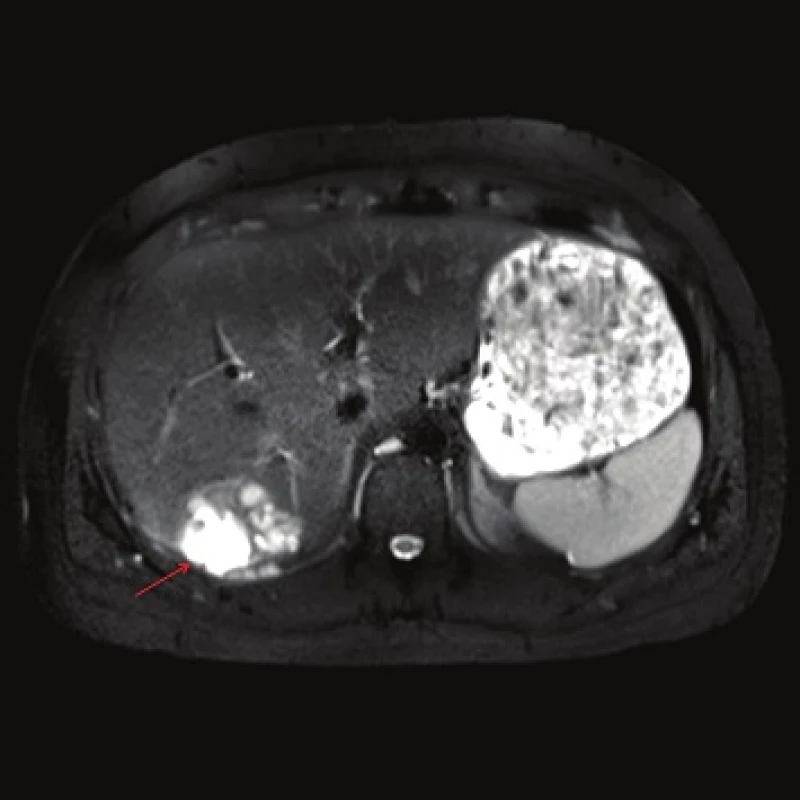

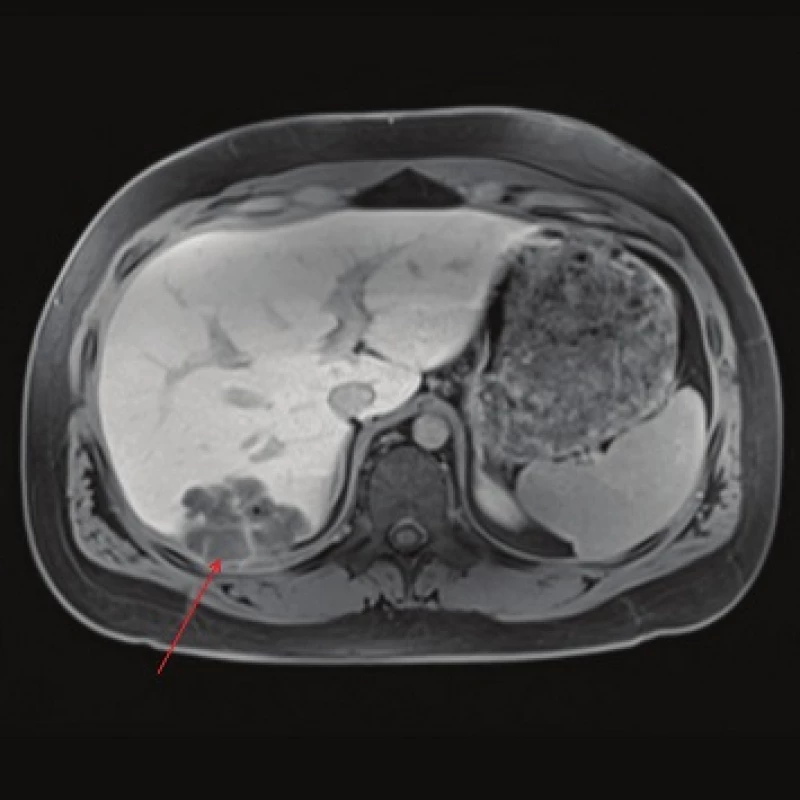

Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated the presence of a cystic lesion in the 7th liver segment, which spread to the base of the right lung (Fig. 1, 2). A parasitic infection, specifically echinococcus, was suspected. However, cytological examination of the aspirate was non-specific. The subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination was highly suspicious of echinococcosis. The MRI demonstrated the presence of a cystic component with calcification in the liver and lung parenchyma (Fig. 3−5).

The patient´s serum was then tested for the presence of anti-Echinococcus multilocularis antibodies using an accredited in-house ELISA IgG method and Western blot; for anti-Echinococcus multilocularis Em2plus and Echinococcus multilocularis Em2-Em18 using ELISA IgG (Bordier Affinity Products SA, Crissier, Switzerland) and for anti-Echinococcus multilocularis antibodies using Western blot (LDBIO, Lyon, France). The serological examinations demonstrated the presence of specific anti-Echinococcus multilocularis antibodies.

The patient was in a very good overall condition. Our inter-disciplinary team decided to perform an en-bloc resection of the liver, diaphragm and lung and to administer albendazole for three months before surgery. The patient tolerated treatment with albendazole well and experienced no complications. The surgery was performed in June 2015. We resected the base of the right lung, a section of the diaphragm and the 7th liver segment via a thoraco-phreno-laparotomy in the form of an en-bloc resection (Fig. 6). The post-operative course was uncomplicated and the patient was discharged after 12 days on continuous long-term albendazole therapy at a dose of 15mg/kg/day. He was followed-up in the Clinic of Infectious Diseases, and was in a very good condition 8 months after the operation.

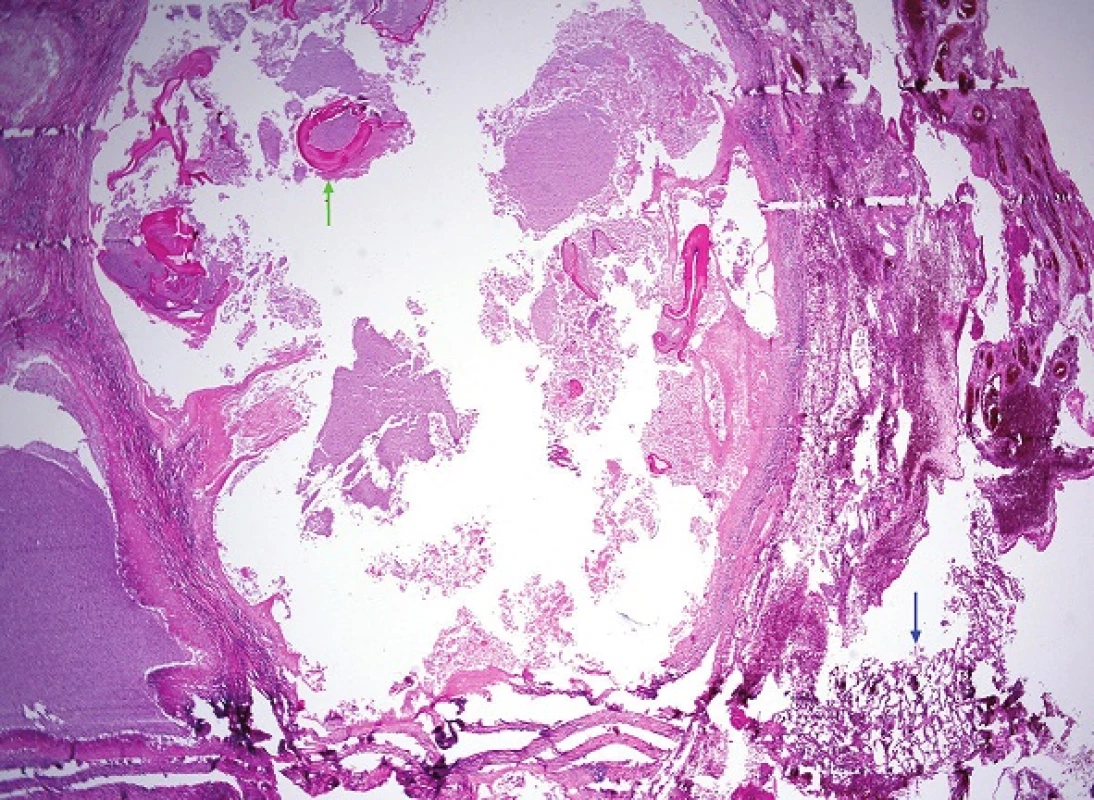

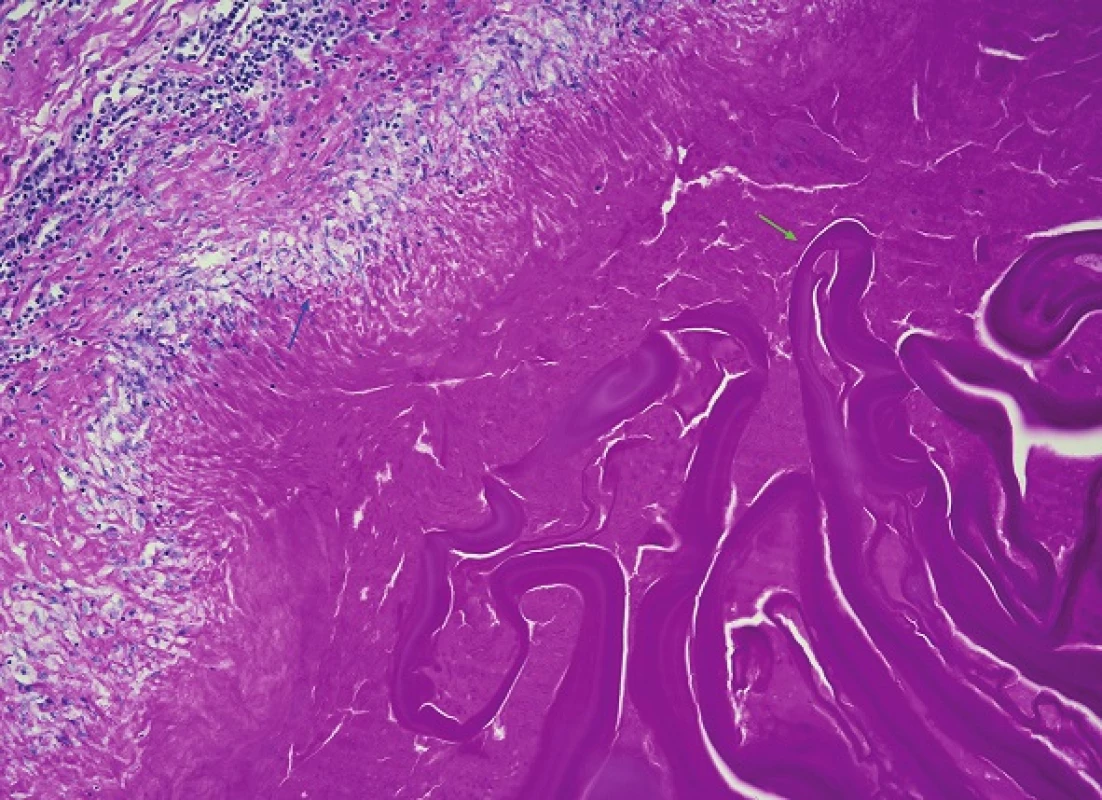

The formalin-fixed biopsy specimen from the lesion was stained with haematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). Microscopic examination of the specimens from the lung, liver and diaphragmatic tissue revealed the presence of cavities with granulation tissue, inflammatory exudate and membranes interspersed with necrotic matter. However, no protoscoleces were detected. Several structures possibly indicative of echinococcus cysts, especially the characteristic PAS-positive laminar membrane, were preserved within the necrotic tissue. It was impossible to unequivocally determine the type of echinococcocus infection based on the macroscopic or microscopic examination (Fig. 7, 8). Given that no tissue had been fixed for subsequent molecular biological examination, tissue embedded in a paraffin block was used to detect specific Echinococcus multilocularis parasitic DNA using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [6]. PCR then demonstrated the identity of our sample as Echinococcus multilocularis with 100% accuracy.

Discussion

In the Czech Republic, human AE remains a rare disease. It was first mentioned by Bartos [7] and its first detailed description was published by Slais et al. [8]. No further cases were described until the beginning of the 21st century. Since 2007, approximately two cases of full-blown AE have been reported annually, with four cases of this infection having been described to date [9,10,11].

The tapeworm eggs that are excreted in animal stools are capable of infecting the intermediate host (small mammals, humans) immediately after defecation. At the same time, the eggs can survive for many years in the external environment. Thus, persons living in areas where infected definitive carnivorous hosts (mainly foxes but also dogs, cats etc.) are present and who come into close contact with these carnivores run the risk of infection. AE transmission occurs mainly in sylvatic regions, but there is also a risk of infection in urban areas [12]. Tourists, gamekeepers and veterinarians who come into contact with infected animals or their excrements represent the population groups at risk of infection.

Today, the parasites and thus AE are prevalent, especially in the northern hemisphere (central Europe, Russia, China, Central Asia, Japan and North America) [13,14]. In some regions of North America, their prevalence among wild foxes and coyotes can reach 50% or higher.

Upon infecting humans, Echinococcus multilocularis affects the liver in the majority of cases (up to 99%), especially the right lobe [15]. The parasite´s growth is the result of exo - and endogenous budding of the alveococcus germinal layer to which adheres a strongly PAS-positive laminar membrane. The fibrotic membrane that would envelop the whole parasitic structure is only poorly developed (if at all). Thanks to its exogenous budding, the parasite spreads diffusely into the surrounding tissue. The histology then demonstrates the presence of parasite islets surrounded by a laminar membrane.

The exogenous type of multiplication creates conditions for the spread of infectious microorganisms via the bloodstream to other organs, where they develop into secondary echinococcal cysts. Echinococcus multilocularis grows very slowly (on average by several mm/year) and this corresponds to the very long incubation period (5−15 years). While it gradually grows on the periphery, its central part undergoes necrosis and progressive calcification. The growth of Echinococcus multilocularis in a given organ can mimic the growth of a tumour.

Patients may remain asymptomatic for several years following infection with AE. The clinical manifestations per se reflect the cyst´s location. In the liver, the hydatid cyst with several daughter cysts may cause obstruction of the adjoining biliary tract, portal vein or lower vena cava. The cyst may become infected during bacteraemia or via direct translocation of the infection from the biliary tract and its symptoms then resemble those of a pyogenic abscess. As it grows, the cyst then induces an inflammatory reaction in the surrounding tissue, which is associated with pressure-like pain in the area of the liver, abdominal discomfort, and respiratory problems especially on deep inspiration as was the case in our patient. The pressure exerted by the cyst may then cause obstruction of the biliary tract with subsequent jaundice and acute cholangitis [16]. Advanced involvement of the liver parenchyma then leads to the development of ascites and liver failure. The infiltrate surrounding the parasitic cyst may penetrate through the diaphragm and involve the adjacent lung segments with the possible development of a bronchial fistula. In such cases, the infection may manifest as respiratory distress, chronic cough, and sub-febrile temperatures. Weight loss and generalised weakness are usually symptoms of advanced AE infection.

The diagnosis is made on the basis of a thorough medical history, symptoms, radiodiagnostic methods, serology, histopathology and molecular biology techniques. Medical history should focus on any visits or sojourns in endemic regions. Small foci in the liver or lung parenchyma are asymptomatic and are diagnosed accidentally during ultrasonography (USG), CT or MRI examination of the abdomen or lungs is performed for different reasons. The USG and CT image shows heterogeneous, hypodense foci with central necrosis, calcifications and irregular contours. MRI is superior for demonstrating central necrosis, but calcifications and small lesions are more difficult to differentiate using this modality. Positron emission tomography (PET CT) is an important method for ruling out dissemination of the parasite within the organism, for detecting disease recurrence and for determining the parasite´s viability.

In its chronic phase, the disease is not associated with eosinophilia, but total IgE levels are significantly elevated. Serological tests (ELISA method – antigen Em2, Em10, Em18) have high but sometimes cross sensitivity (64–100%) and high specificity (up to 97%). Some authors claim that serology is important not only for determining the diagnosis, but also for disease dynamics [17,18]. However, it is not suitable for assessing treatment efficacy, as the antibody response persists long after treatment has been initiated. This is why it is useful to concomitantly monitor total IgE antibody levels, as their levels decrease when the treatment is successful. The definitive diagnosis is based on the characteristic histopathological findings and/or the results of molecular biological techniques.

Treatment of Echinococcus multilocularis infection is much more difficult than the treatment of Echinococcus granulosus infection. In the case of localised AE lesions, radical surgical resection with peri-operative and life-long treatment with albendazole are indicated, as was the case in our patient. This treatment gives patients a more than 80% chance of survival in the subsequent 10 years [19]. Palliative resection and subsequent treatment with albendazole (or praziquantel) may be an option if both liver lobes are involved and there is infiltration of the major vessels and surrounding bile ducts [20]. Liver transplant may be envisaged in the case of extensive liver involvement and chronic hepatic failure. Nonetheless, disease recurrence cannot be ruled out even following radical surgery including liver transplant and the long-term administration of albendazole [21,22]. Chances for a complete cure are minimal if patients receive pharmacotherapy alone without surgical treatment. Post-operative complications include the formation of biliary fistulas in 1−10% of cases. Stenosis of the biliary tract is rather rare. The risk of local recurrence is up to 10% and is often associated with more conservative therapeutic approaches, but may also be caused by careless manipulation with the cyst content [23,24]. The only prevention of this serious form of parasitic infection involves thorough hygiene and great care when in contact with animals and their excrements, especially in endemic regions. Patients must be followed closely for their whole lives because of the risk of recurrence of this serious disease.

Conclusion

AE is a rare and prognostically serious disease. Radical surgical treatment together with the administration of (sometimes life-long) chemotherapeutic treatment is fundamental from the aspect of patient long-term survival. However, the possibility of disease recurrence anywhere in the organism cannot be ruled out, despite optimal therapeutic approaches. For this reason, life-long follow-up of patients is necessary.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have not conflict of interest in connection with the emergence of and that the article was not published in any other journal.

Prof. MUDr. Vladislav Treska, DrSc.

Alej Svobody 80

304 60 Pilsen

e-mail: treska@fnplzen.cz

Sources

1. Dyachenko V, Pantchev N, Gawlowska S, et al. Echinococcus multilocularis infections in domestic dogs and cats from Germany and other European countries. Vet Parasitol 2008;157 : 244−53.

2. Auer H, Hermentin K, Aspock H. Demonstration of a specific echinococcus multilocularis antigen in the supernatant of in vitro maintained protoscoleces. Zbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg 1988;268 : 416−23.

3. Auer H, Aspöck H. Helminths and helminthoses in Central Europe: diseases caused by cestodes (tapeworms). Wien Med Wochenschr 2014;164 : 414−23.

4. Kolarova L, Mateju J, Hrdy J, et al. Human alveolar echinococcosis, Czech Republic, 2007–2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2015, in press.

5. Skalicky T, Treska V, Martinek K, et al. Alveolar hydatidosis – a rare case of liver involvement in the Czech Republic. Ces Slov Gastroent Hepatol 2008;62 : 30−3.

6. Schneider R, Gollackner B, Edel B. Development of a new PCR protocol for the detection of species and genotypes (strains) of echinococcus in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Int J Parasitol 2008;38 : 1065−71.

7. Bartos V. Alveolar echinococcosis in the liver. Cas Lek Ces 1928;67 : 1063.

8. Slais J, Madle A, Vanka K. Alveolar hydatidosis (echinococcosis) diagnosed by liver puncture biopsy. Cas Lek Ces 1979;118 : 472−5.

9. Lukacova L, Kolarova L, Roznovsky L, et al. Alveolar echinococcosis-a new emerging diseases? Cas Lek Ces 2009;148 : 132−6.

10. Kodet R, Hladik P, Padr R, et al. Fox tapeworm and real risk for human infection. Myslivost 1983;61 : 46–7.

11. Kupka T, Bala P, Hozakova L, et al. Rare case of cystic disease of the liver - alveolar echinococcosis of the liver. Vnitr Lek 2015;61 : 527−30.

12. Akcam AT, Ulku A, Koltas IS, et al. Clinical characterisation of unusual cystic echinococcosis in southern part of Turkey. Ann Saudi Med 2014;34 : 508−16.

13. Gottstein B, Stojkovic M, Vuitton DA, et al. Threat of alveolar echinococcosis to public health - a challenge for Europe. Trends Parasitol 2015;31 : 407−12.

14. Schweiger A, Ammann RW, Candinas D, et al. Human alveolar echinococcosis after fox population increase, Switzerland. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13 : 878−82.

15. Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta tropica 2010;114 : 1−16.

16. Graeter T, Ehing F, Oeztuerk S, et al. Hepatobiliary complications of alveolar echinococcosis: A long-term follow-up study. World J Gastroenterol 2015;28 : 4925−32.

17. Kodana Y, Fujita N, Shimizu T, et al. Alveolar echinocaccosis: MR findings in the liver. Radiology 2003;228 : 172−7.

18. Jeong JS, Han SY, Kim YH, et al. Serological and molecular characteristics of the first Korean case of echinococcus multilocularis. Korean J Parasitol 2013;51 : 595−7.

19. Wuestenberg J, Gruener B, Oeztuerk S, et al. Diagnostics in cystic echinococcosis: serology versus ultrasonography. Turk J Gastroenterol 2014;25 : 398−404.

20. Charbonnier A, Knapp J, Demonmerot F, et al. A new data management system for the French national registry of human alveolar echinococcosis cases. Parasite 2014;21 : 69.

21. Liu C, Zhang H, Yin J, Hu W. In vivo and in vitro efficacies of mebendazole, mefloquine and nitazoxanide against cyst echinococcosis. Parasitol Res 2015;114 : 2213−22.

22. Popa GL, Tanase I, Popa CA, et al. Medical and surgical management of a rare and complicated case of multivisceral hydatidosis; 18 years of evolution. New Microbiol 2014;37 : 387−91.

23. Farrokh D, Zandi B, Pezeshki RM, et al. Hepatic alveolar echinococcosis. Arch Iran Med 2015;18 : 199−202.

24. Ahn KS, Hong ST, Kang YN, et al. An imported case of cystic echinococcosis in the liver. Korean J Parasitol 2012;50 : 357−60.

Labels

Surgery Orthopaedics Trauma surgeryArticle was published in

Perspectives in Surgery

2016 Issue 6

- Metamizole vs. Tramadol in Postoperative Analgesia

- Metamizole at a Glance and in Practice – Effective Non-Opioid Analgesic for All Ages

- Safety and Tolerance of Metamizole in Postoperative Analgesia in Children

Most read in this issue

- Laparoscopic resection rectopexy in the treatment of obstructive defecation syndrome

- Different techniques of vessel reconstruction in kidney transplantation −10-years experiences

- Management of acute postoperative pain following thoracotomy – state of the art

- Videothoracoscopic excision of mediastinal parathyroid adenoma in primary hyperparathyroidism