-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Aripiprazole in the Maintenance Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: A Critical Review of the Evidence and Its Dissemination into the Scientific Literature

Background:

Aripiprazole, a second-generation antipsychotic medication, has been

increasingly used in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder and

received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this

indication in 2005. Given its widespread use, we sought to critically review

the evidence supporting the use of aripiprazole in the maintenance treatment

of bipolar disorder and examine how that evidence has been disseminated inthe scientific literature.

Methods and Findings:

We systematically searched multiple databases to identify double-blind,

randomized controlled trials of aripiprazole for the maintenance treatment

of bipolar disorder while excluding other types of studies, such as

open-label, acute, and adjunctive studies. We then used a citation search to

identify articles that cited these trials and rated the quality of their

citations. Our evidence search protocol identified only two publications,

both describing the results of a single trial conducted by Keck et al.,

which met criteria for inclusion in this review. We describe four issues

that limit the interpretation of that trial as supporting the use ofaripiprazole for bipolar maintenance:

(1) insufficient duration to

demonstrate maintenance efficacy; (2) limited generalizability due to its

enriched sample; (3) possible conflation of iatrogenic adverse effects of

abrupt medication discontinuation with beneficial effects of treatment; and

(4) a low overall completion rate. Our citation search protocol yielded 80

publications that cited the Keck et al. trial in discussing the use of

aripiprazole for bipolar maintenance. Of these, only 24 (30%)

mentioned adverse events reported and four (5%) mentioned studylimitations.

Conclusions:

A single trial by Keck et al. represents the entirety of the literature on

the use of aripiprazole for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.

Although careful review identifies four critical limitations to the

trial's interpretation and overall utility, the trial has beenuncritically cited in the subsequent scientific literature.

:

Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Published in the journal: Aripiprazole in the Maintenance Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: A Critical Review of the Evidence and Its Dissemination into the Scientific Literature. PLoS Med 8(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000434

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000434Summary

Background:

Aripiprazole, a second-generation antipsychotic medication, has been

increasingly used in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder and

received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this

indication in 2005. Given its widespread use, we sought to critically review

the evidence supporting the use of aripiprazole in the maintenance treatment

of bipolar disorder and examine how that evidence has been disseminated inthe scientific literature.

Methods and Findings:

We systematically searched multiple databases to identify double-blind,

randomized controlled trials of aripiprazole for the maintenance treatment

of bipolar disorder while excluding other types of studies, such as

open-label, acute, and adjunctive studies. We then used a citation search to

identify articles that cited these trials and rated the quality of their

citations. Our evidence search protocol identified only two publications,

both describing the results of a single trial conducted by Keck et al.,

which met criteria for inclusion in this review. We describe four issues

that limit the interpretation of that trial as supporting the use ofaripiprazole for bipolar maintenance:

(1) insufficient duration to

demonstrate maintenance efficacy; (2) limited generalizability due to its

enriched sample; (3) possible conflation of iatrogenic adverse effects of

abrupt medication discontinuation with beneficial effects of treatment; and

(4) a low overall completion rate. Our citation search protocol yielded 80

publications that cited the Keck et al. trial in discussing the use of

aripiprazole for bipolar maintenance. Of these, only 24 (30%)

mentioned adverse events reported and four (5%) mentioned studylimitations.

Conclusions:

A single trial by Keck et al. represents the entirety of the literature on

the use of aripiprazole for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.

Although careful review identifies four critical limitations to the

trial's interpretation and overall utility, the trial has beenuncritically cited in the subsequent scientific literature.

:

Please see later in the article for the Editors' SummaryIntroduction

First-generation antipsychotic medications have been used for many decades in the short-term treatment of acute manic episodes associated with bipolar disorder [1]. Second-generation antipsychotic medications have increasingly gained popularity for this use as well [2]. However, their promotion for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder is a more recent phenomenon [3]–[6]. In one recently published nationally representative survey of physicians, mood disorders accounted for the majority of antipsychotic medication prescriptions [7], and a recent shift to prescription of antipsychotic medications was observed in a sample of San Diego county Medicaid beneficiaries with bipolar disorder [8].

Traditionally, the clinical care of patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder has been divided into three phases (borrowed from clinical consensus about the phases of treatment for major depressive disorder [9],[10]): treatment of acute episodes to symptomatic remission, continuation treatment to prevent relapse, and maintenance treatment to prevent recurrence. The 2 mo following recovery from the acute episode is commonly described as acute phase recovery, and the continuation phase of treatment (during which the natural course of the episode is considered still active even though the patient may be asymptomatic) is defined as lasting from months 2 through 6 [11],[12]. The medication used for treatment in the acute phase is often extended for treatment in the continuation and maintenance phases [13],[14] and in this context may include lithium, valproate, lamotrigine, or a second-generation antipsychotic medication such as olanzapine, aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, or ziprasidone [15]. However, although the use of second-generation antipsychotic medications to treat acute mania is supported by a relatively well-established evidence base [16]–[18], efficacy in treatment of acute mania does not necessarily imply efficacy for maintenance or prophylaxis [13],[19],[20]. As Goodwin and Jamison note: “Simply because a drug has anti-manic properties (and if continued, will protect against relapse back into mania in the months after the acute episode), one cannot assume that it will be effective in the prevention of new episodes. While this assumption may be true (to some extent) for lithium, it is not well supported by the data with respect to all the other antimanic agents” (p. 800) [21].

Despite the need for robust evidence on the maintenance and/or long-term prophylactic treatment of bipolar disorder, to date very little has been supplied in this regard [4],[15],[22],[23]. There remains little consensus about recommended courses of maintenance or prophylactic treatment, and consequently overall psychopharmacological treatment patterns vary widely [24]–[28]. Aripiprazole, first approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of schizophrenia in 2002, is the newest of the second-generation antipsychotic medications to have obtained FDA approval for use in bipolar disorder. In 2004 it was approved for the treatment of acute manic and mixed episodes associated with bipolar disorder, and in 2005 it was granted an additional indication for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder [29]. Since its approval, aripiprazole has rapidly become a popular choice among clinicians in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Total U.S. sales for aripiprazole (across all indications) increased from US$1.5 billion in 2005 to US$4 billion in 2009 [30]. In a recent study in which U.S.-based physicians were queried about their preferred pharmacological treatments for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, only 3% of psychiatrists and 7% of primary care physicians named aripiprazole as their first choice for treating schizophrenia, whereas 23% of psychiatrists and 16% of primary care physicians named aripiprazole as their first choice for treating bipolar disorder [31]. Consistent with this survey, from 2002–2007, the most common indication for the prescription of aripiprazole in office-based practice settings was for bipolar disorder (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] Diagnosis Code 296.0) [32].

In the setting of chronic illnesses such as bipolar disorder, critical appraisal of long-term treatments has important implications for policy making. Overall medication costs for the chronically ill are driven largely by decisions about the ongoing use of prescription medications, rather than by decisions about whether to initiate their use [33]. Spending on prescription medications is the fastest-growing category of the U.S. health care budget [34], further underscoring the need for a rigorous evidence-based approach regarding their prescription and use. Given the rapid adoption and widespread use of aripiprazole in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder, we decided to review the scientific data supporting its use in this setting. A secondary aim of this study was to examine the diffusion of this data into the subsequent scientific literature.

Methods

Primary Evidence Search

We sought to identify double-blind (i.e., where participants and physicians administering medications were blind to treatment assignment), randomized controlled studies of aripiprazole for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder, while also avoiding inadvertent inclusion of acute treatment studies or other study designs. Therefore we required studies to have a duration greater than 4 mo in order to be included in our review, and excluded open-label, acute, and adjunctive studies. We searched for published literature as well as unpublished and ongoing clinical trials, with no language restrictions. The following systematic search strategy was employed to search PubMed: “bipolar disorder”[MeSH Terms] OR (“bipolar”[All Fields] AND “disorder”[All Fields]) OR (“bipolar disorder”[All Fields]) AND (“aripiprazole”[Substance Name] OR “aripiprazole”[All Fields]) AND (“maintenance”[MeSH Terms] OR “maintenance”[All Fields]). We also searched Scopus (including Embase and MEDLINE) using the same search terms (“bipolar disorder” OR “bipolar” AND “disorder” AND “aripiprazole” AND “maintenance”). We also searched ClincalTrials.gov, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 3 of 4, July 2010), and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal using the terms “aripiprazole” and “bipolar.” We did not attempt to contact the manufacturer directly to inquire about possibly unpublished trials, but we screened all listings on the Bristol-Myers Squibb Clinical Trials Disclosure Web site under Clinical Trial Results, Psychiatric Disorders [35]. All searches were conducted in July 2010. And finally, we submitted a request under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act [36] for the supplemental New Drug Application (NDA) filed by the study sponsor to obtain additional labeling for the use of aripiprazole as maintenance therapy in bipolar I disorder [29], and we searched it manually for further reference to other published or unpublished studies.

Citation Search

We also sought to better understand the influence of the primary evidence on the broader scientific literature. To do this, we used the Web of Science(R) Science Citation Index Expanded to search for articles that cited the primary evidence identified through the evidence search protocol detailed above. Next, we evaluated the articles on how they cited the primary evidence, using criteria similar to those used in a previous study on the quality of news media reports of medication trials [37]. Each of the citing articles was rated on three quality criteria by a single study author (NZR). A 15% random sample of articles (n = 15) was double-coded independently by another study author (ACT), and the Cohen's kappa coefficient was calculated in order to assess the degree of inter-rater agreement [38]. We chose dichotomous quality ratings to provide conservative estimates of citation quality and in order to limit subjective judgments by the rater. First, articles were screened for any mention of the use of aripiprazole specifically for ongoing, maintenance, or prophylactic treatment of bipolar disorder. If the answer to this question was “yes,” then the article was further rated on the three quality criteria: (1) whether the article reported any quantitative data from the primary evidence (e.g., odds ratios, percentages, or p-values); (2) whether the article mentioned any adverse events described in the primary evidence; and (3) whether the article mentioned any limitations of the primary evidence.

Although our citation search protocol was not specifically targeted towards identifying treatment guidelines and review articles on pharmacological treatment strategies in bipolar disorder, we manually highlighted for further discussion those that were identified in the citation search. Our citation search protocol likely underestimates the influence of the primary evidence because we did not also use a database such as Google Scholar that could have also identified guidelines implemented by hospitals, government, or other institutions whose documents in this area have not been published in peer-reviewed journals or indexed in services such as PubMed. However, we chose to highlight treatment guidelines and reviews because they can be particularly influential in shaping prescribing behavior.

Results

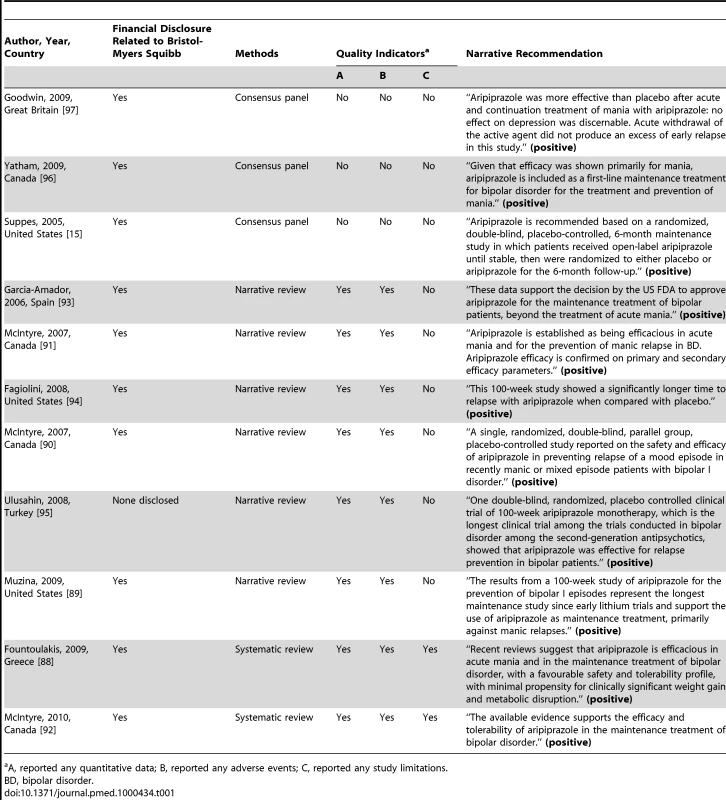

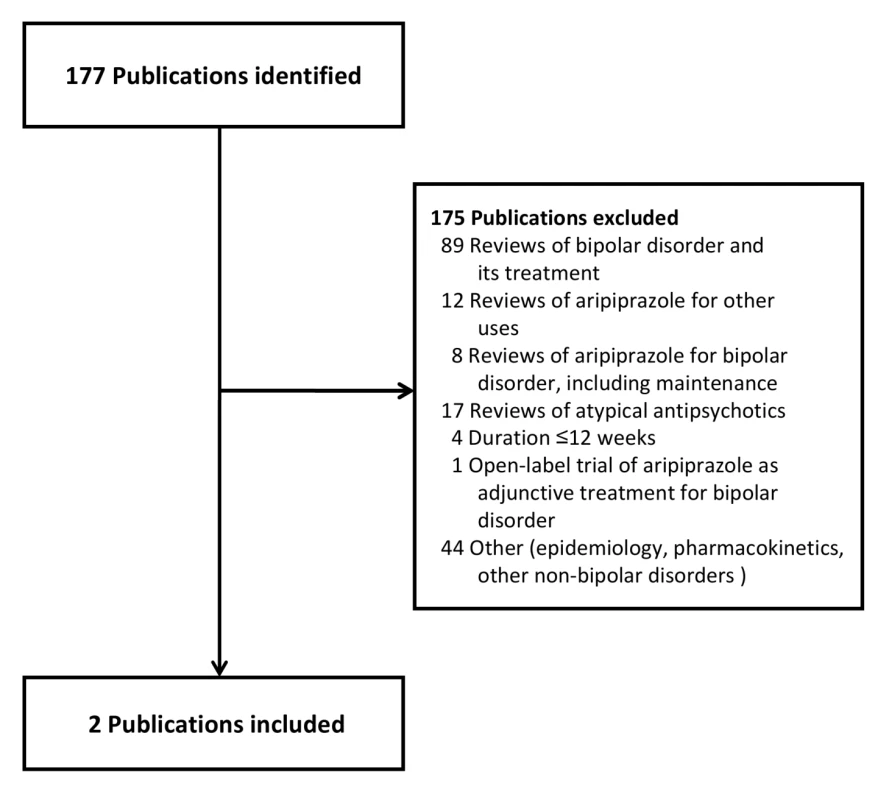

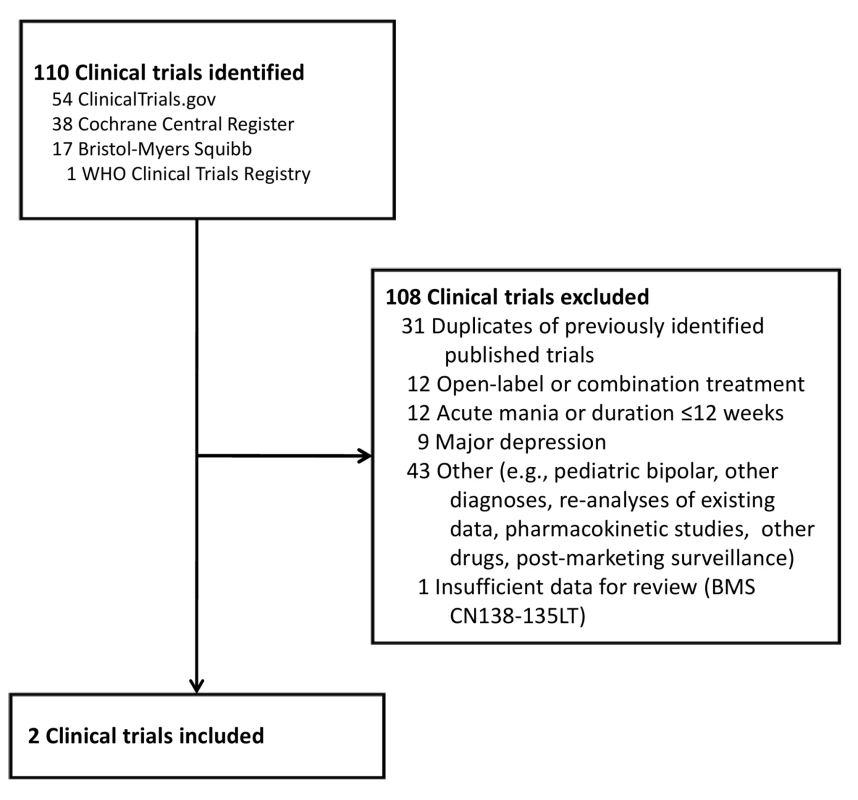

Our primary evidence search protocol identified 177 unique citations (Figure 1). Of these 177 citations, only two publications met criteria for inclusion in our review [39],[40]. Searching the clinical trials registries yielded two listings meeting inclusion criteria, but these referred to the two publications already identified (Figure 2) [39],[40]. Further details on the excluded acute and adjunctive studies are provided in Tables S1 and S2. Two unpublished trials initially appeared to meet criteria for inclusion but were ultimately excluded. The first, Otsuka NCT00606177 [41], was a 3-wk placebo-controlled trial of aripiprazole for treatment of acute mania with a 22-wk extension phase, but it was described as currently still recruiting study participants. The second, BMS CN138-135LT [42], was a completed 40-wk extension of a 12-wk randomized lithium - and placebo-controlled trial of aripiprazole for acute mania. Although the 12-wk acute outcomes data from BMS CN138-135 were published in a peer-reviewed journal [43], the outcomes data from the 40-wk extension have not, to our knowledge, been published (and the little data made available in the synopsis posted online by the manufacturer were inadequate for detailed critical assessment). The manufacturer's synopsis indicates that 4.5% of participants on aripiprazole completed the extension phase, compared to 8.1% for those on lithium. A third arm of the study, completed by 8.5% of participants, entailed treatment with placebo for 3 wk followed by crossover to aripiprazole. Finally, the supplemental NDA contained no references to additional studies, published or unpublished, meeting inclusion criteria (Text S1) [29].

Fig. 1. Publications identified for review.

Fig. 2. Clinical trials identified for review.

The two peer-reviewed publications included in our review report the results of a single randomized trial (hereafter referred to as “the Keck trial”) implemented under the auspices of the Aripiprazole Study Group and sponsored by the manufacturer of the drug, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. One publication describes the initial 26-wk double-blind phase [39], and the other its 74-wk extension [40]. We also identified a post hoc subgroup analysis of data from the Keck trial focused on participants diagnosed with the rapid-cycling variant of bipolar disorder [44]. We also identified a separate trial [45], also authored by Keck and colleagues, examining the efficacy of aripiprazole in the treatment of acute manic episodes, with outcomes assessed at 3 wk. Given the paucity of available evidence on aripiprazole for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder, we decided to review the Keck trial [39],[40] in detail.

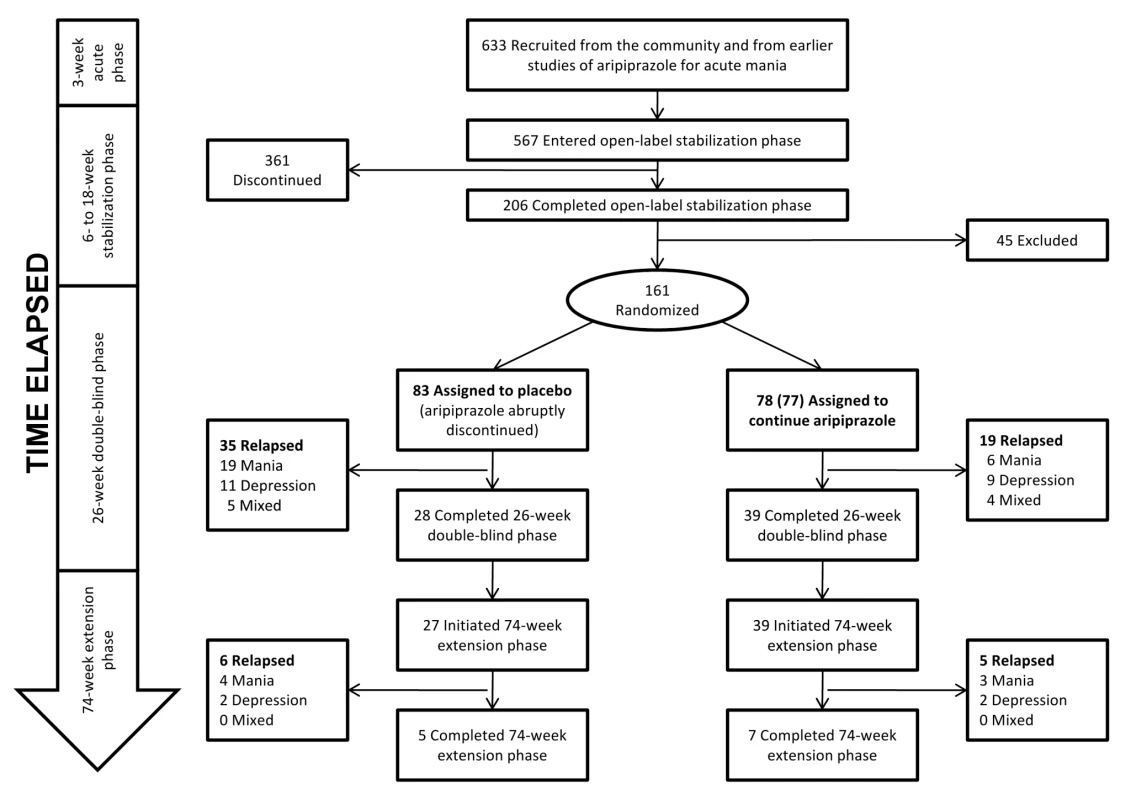

The Keck Trial

A total of 633 adult participants meeting DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder were enrolled in the Keck trial. A flow chart of the trial is shown in Figure 3. For inclusion, participants must either have completed a prior 3-wk acute mania trial [45], met eligibility criteria for a prior acute mania trial but declined participation in that trial, or experienced a manic or mixed episode within the prior 3 mo. The publication describing the 26-wk double-blind phase [39] indicates that participants were recruited from 76 sites in the U.S., Mexico, and Argentina (but does not specify the numbers of sites within each country or the numbers of patients from each site). Of the original enrollees, 567 entered the “stabilization phase,” which consisted of open-label treatment with aripiprazole for 6–18 wk. Participants remained in this phase until their Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) was ≤10 and their Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) was ≤13 during four consecutive visits over a minimum of 6 wk. 206 participants completed the stabilization phase. Of these, 161 entered the double-blind phase. The supplemental NDA indicates that participants who completed the stabilization phase and entered randomization were derived from 45 sites in the U.S. (n = 124), three sites in Argentina (n = 7), and two sites in Mexico (n = 30). These 161 participants were assigned either to an intervention arm in which they continued taking aripiprazole at the stabilizing dose (n = 77 or 78; both numbers are reported [40]) or to a placebo arm in which aripiprazole was abruptly discontinued and replaced with placebo (n = 83). 39 (50% of the 77 or 78 who entered randomization) in the intervention arm and 28 participants (34%) in the placebo arm completed the 26-wk double-blind phase. Time to relapse was described as longer for participants treated with aripiprazole compared to those who were switched to placebo. Mean times to relapse were not provided, but the hazard ratio for relapse was given as 0.52 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.30–0.91). When time to relapse was partitioned into manic versus depressive relapse, the difference in overall time to relapse was found to be driven primarily by an effect on manic relapse (23% relapse rate on placebo versus 8% relapse rate on aripiprazole). No differences in time to depressive relapse (13% versus 12%) or to mixed state relapse (6% versus 5%) were noted. Keck and colleagues concluded that aripiprazole “was superior to placebo in maintaining efficacy in patients with bipolar I disorder with a recent manic or mixed episode who were stabilized and maintained on aripiprazole treatment for 6 weeks” (p. 626) [39].

Fig. 3. Keck study participant flow.

The extension phase of the Keck trial, published as a separate paper [40], followed the remaining participants over the subsequent 74 wk: 27 participants in the placebo group (of the 28 who completed the double-blind phase) and 39 participants in the aripiprazole group. The authors concluded: “Over a 100-week treatment period, aripiprazole monotherapy was effective for relapse prevention in patients who were initially stabilized on aripiprazole for 6 consecutive weeks, and it maintained a good safety and tolerability profile” (p. 1480) [40]. Similar to the data from the first 26 wk, time to manic relapse was reported to be longer for the aripiprazole group (with no difference between groups in time to depressive relapse).

Four Substantive Criticisms of the Keck Trial

Although the Keck trial was the sole basis for aripiprazole receiving an additional FDA-approved indication for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder [29], we believe that reading the Keck trial as supporting the use of aripiprazole for this indication is an overinterpretation of the trial's design and the data it generated. First, the duration of the Keck trial was insufficient to demonstrate prophylactic efficacy. Second, the double-blind phase of the Keck trial was based on an enriched sample of patients who had already responded to the medication during the stabilization phase, thereby limiting generalizability of the trial's findings. Third, the randomized discontinuation design of the Keck trial may conflate iatrogenic adverse effects of abrupt medication discontinuation with the beneficial effects of short-term continuation treatment. All of the putative benefit occurred during the double-blind phase of the trial, and little improvement was gained during the extension phase. And finally, the overall completion rate was 1.3%, requiring unrealistic extrapolation to draw meaningful conclusions. Keck et al. [39],[40] mention lack of generalizability as a potential limitation of the enrichment design, but they do not discuss how these other limitations may have compromised the trial's internal validity.

The FDA's review of the Keck trial identified other substantive concerns, including the fact that the p-value for the primary analysis changed from 0.02 to 0.10 when the statistical reviewer excluded data from one of the trial's two Mexican sites (where the relapse rate among participants in the aripiprazole arm was lower than the other trial sites) [46]. While of general concern, this and other issues identified by the FDA are unrelated to our methodological critiques. All of these factors undercut even a cautious interpretation of the Keck trial as supporting the use of aripiprazole for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Below we review each of these criticisms in detail.

Insufficient duration to demonstrate prophylactic efficacy

In the open-label phase of the Keck trial, stability was defined by whether or not a participant maintained YMRS and MADRS scores in the asymptomatic range for at least 6 consecutive weeks. To meet this criterion, on average the trial participants spent 89 d in the stabilization phase. Comparing their own work to other randomized discontinuation studies of maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder that required a shorter duration of stability [47]–[49], Keck et al. describe their stability criterion as “the most stringent criteria to date to define stability” (p. 634) [39]. Intervention-arm participants who had achieved stability on aripiprazole were then assigned to continue with aripiprazole, and placebo-arm participants abruptly switched to placebo, for the following 26 wk.

Contrary to the authors' claims, we argue here that, given the natural history of bipolar disorder, the design of the Keck trial was unsuitable for evaluating the efficacy of aripiprazole in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. The episodic nature of recurrent mania and depression require investigators to randomize, enroll, and retain patients for a duration sufficient to demonstrate maintenance and/or prophylactic efficacy. While there is high interindividual variation, the median length of untreated episodes has been reported to vary from 3–6 mo in clinical trial settings and from 2–3 mo in epidemiological studies [50], with depressive episodes typically lasting longer than manic episodes [21],[51]. Thus, even if one does not accept the other methodological concerns we describe in this paper, the Keck trial, with its stabilization criterion of 6 wk, could at best be used to demonstrate a short-term benefit of continuation treatment in preventing relapse of symptoms attributable to an ongoing acute episode [52]. Demonstration of maintenance efficacy in preventing recurrence of mood episodes would require benefit to be shown at least 6 mo after the acute phase. 6 mo has been traditionally recognized as the point at which continuation treatment becomes maintenance treatment [10],[11],[12],[52]–[54]. Appropriately, the clinical review contained in the supplemental NDA describes a meeting with the study's sponsors in which the FDA's Division of Neuropharmacological Drug Products “expressed that the duration of the open-label stabilization phase defines duration of effect and noted that an optimal study design would include a six month open-label stabilization phase and randomized withdrawal of patient subgroups at specified timepoints” (p. 9) [55]. The leading textbook in the field suggests an even more stringent threshold study duration: “Because the natural history of bipolar disorder is for it to recur, on average, every 16–18 months, true prophylaxis cannot be evaluated in 6 or 12 months” (p. 801) [21]. Although somewhat controversial, the idea that demonstration of true prophylactic efficacy requires a study duration longer than that which has been typically utilized has been supported by other leading researchers as well [11],[52],[56].

Limited generalizability due to the enriched sample

Only participants who had responded to aripiprazole in the stabilization phase of the trial were included in the double-blind phase of the trial. Of the 567 participants who entered the stabilization phase, only 206 completed it. Some of the randomized participants received unblinded medication and were therefore discontinued [29], so the double-blind efficacy dataset consisted of 161 participants. This means that 361 of the 567 (74%) participants who entered the stabilization phase but dropped out were excluded from randomization because of adverse events, lack of efficacy, withdrawal of consent, and other reasons as detailed in the publication—leaving behind a selected group of participants who had responded favorably to aripiprazole in the stabilization phase to be subsequently randomized. This design could have the effect of biasing the trial's findings away from the null [57], and, even in the absence of such bias, the results from this enriched sample cannot be generalized to the majority of persons diagnosed with bipolar disorder. This limitation of the randomized discontinuation design has long been recognized by drug trialists [11],[12],[56],[58]–[65] and is not dissimilar to criticisms voiced about the first generation of randomized trials evaluating the use of lithium for maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder, i.e., that those study designs selected preferentially for lithium-responsive variants of the disorder [66],[67].

Possible conflation of iatrogenic effects with beneficial effects

The randomized discontinuation study design could explain the putatively positive findings on preventing relapse even in the absence of a true drug effect. In the Keck trial, the randomization sample was enriched with participants who had already responded to aripiprazole in the stabilization phase and were therefore more likely to experience an iatrogenic relapse of symptoms when aripiprazole was abruptly discontinued in the double-blind phase. Abrupt discontinuation, or even abrupt partial removal, of a drug used for maintenance has long been known to provoke relapse in patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder [68]–[77]. This “bipolar rebound phenomenon” has been most often described for lithium, but it has also been observed in the setting of abruptly withdrawn antiepileptic [78], antipsychotic [3],[12],[48],[56],[78]–[80], and antidepressant medications [59],[75],[78],[81] administered to persons diagnosed with other mood and psychotic disorders. For this reason, Geddes et al. specifically excluded studies with a randomized discontinuation design from their systematic review and meta-analysis of the long-term use of lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder [82].

Thus, if aripiprazole had no effect on preventing relapse, the Keck trial might still be expected to show a higher relapse rate early in the double-blind phase among participants assigned to the placebo arm (compared to those assigned to the intervention arm), and then similar relapse rates between study arms during the extension phase. This particular design element appears to have substantially influenced the outcome of the Keck trial, as is evident from a comparison of data from the 26-wk double-blind phase with data from the 74-wk extension phase. During the 26-wk double-blind phase, 19 out of 83 participants (23%) in the placebo arm experienced a manic relapse, whereas only four (5%) did so in the subsequent 74-wk extension phase.

When relapse data from the 74-wk extension phase are examined separately from those from the first 26 wk (Figure 3), only four participants in the placebo arm experienced a relapse to mania, compared to 3 participants in the intervention arm (4.8% versus 3.8%). This information is not explicitly presented in either paper and can only be discerned by comparing the papers side by side and calculating the differences by hand. Figure 4 in the 74-wk extension phase publication (p. 1486) [40] shows that 28% of participants in the placebo arm relapsed to mania over 100 wk of follow up. Given n = 83 in the placebo arm, this suggests 23 participants in the placebo arm relapsed to mania over 100 wk of follow up. Because 19 participants in the placebo arm relapsed to mania in the first 26 wk (Figure 5 in the 26-wk double-blind phase publication [p. 531] [39]), this means four participants relapsed to mania during the 74-wk extension phase. We employed similar reasoning to calculate the number of participants who relapsed to mania in the intervention arm, as well as the number of participants who relapsed to depressive and mixed states. Similar patterns are observed for relapse to depression and relapse to mixed state for the placebo and aripiprazole arms. Thus, virtually all of the reported placebo-aripiprazole difference in relapse occurred during the first 26 wk of the trial.

Fig. 4. Publications citing the Keck study.

Limitations of the low completion rate

Only seven of 39 (18%) aripiprazole-treated participants and five of 27 (19%) placebo-treated participants completed the 74-wk extension phase. The low completion rate in the treatment arm is especially striking given that only participants who had proven to be responders in the initial stabilization phase were included in the double-blind and extension phases and that the placebo group matched the aripiprazole group in terms of trial completion. Out of the 633 participants who entered the trial, after excluding the 83 who were switched to placebo, only seven aripiprazole-treated participants completed the 100-wk trial, for a completion rate among aripiprazole-treated participants of less than 1.3%. This is not explicitly noted anywhere in the paper [40]. Keck et al. [40] acknowledge that only 12 participants completed the trial, but the smaller denominator used for comparison is the number of participants who entered the 74-wk extension phase rather than all participants who entered the trial.

We argue that drawing meaningful conclusions from a trial with an overall completion rate of less than 1.3% is an inappropriate undertaking. The completion rate substantially limits generalizability of the trial's findings, as trial completers very likely were dissimilar to the enrolled and/or randomized participant pools. The meaningful differences between completers and noncompleters were demonstrated in a randomized trial of divalproex versus lithium for relapse prevention in bipolar disorder [83]: participants who completed the trial had milder symptoms at baseline and a less severe lifetime illness course [84]. Keck et al. identify the low completion rate in the extension phase as a potential limitation but appeal to the low completion rates observed in other maintenance trials [47],[48] to support the generalizability of their results. In contrast, we view the similar completion rates observed in other long-term studies as similarly raising concerns about how to draw inferences from these trials to inform routine clinical practice. Still, we observe that other investigators have successfully implemented long-term studies in this patient population with greater rates of completion: for example, earlier studies of lithium in the treatment of affective disorders demonstrated completion rates of 92.9% (26/28) [85] and 73.2% (74/101) [86] among lithium-treated participants.

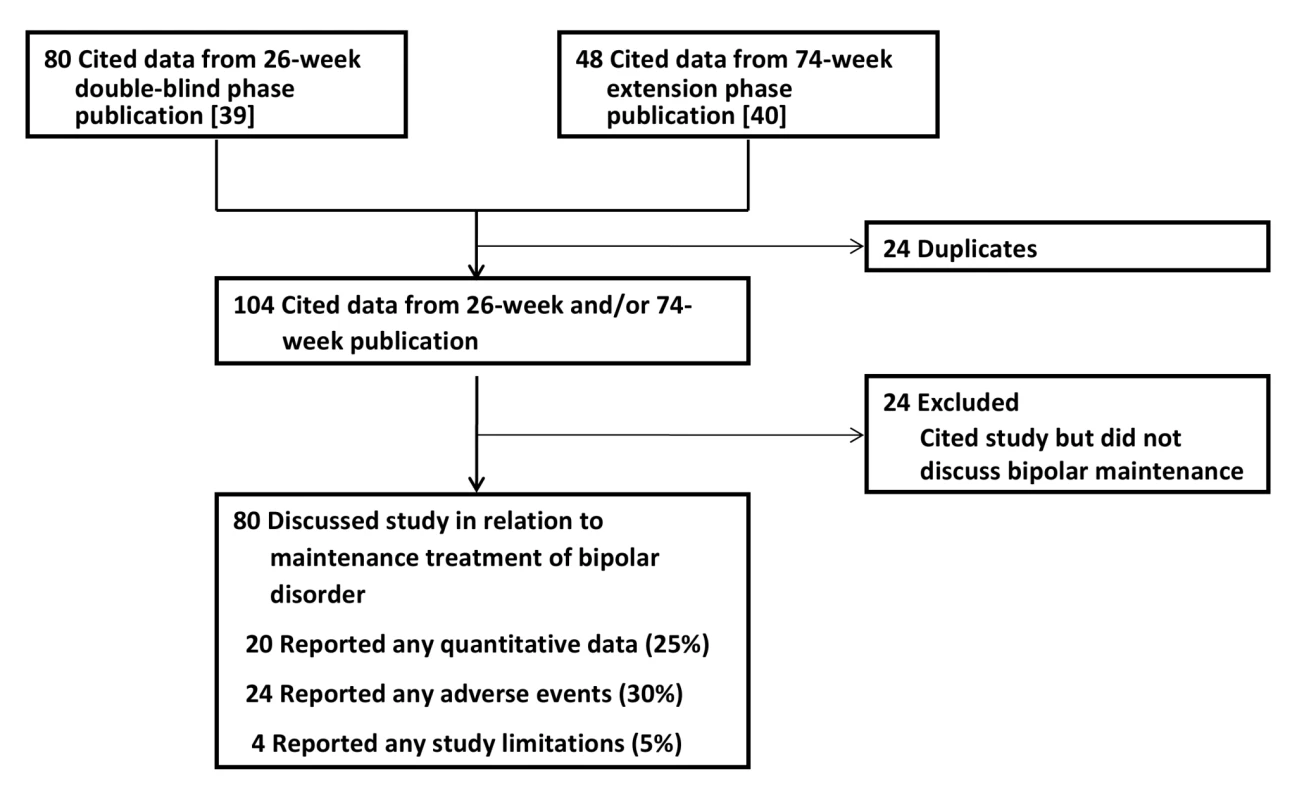

Impact of the Keck Trial on the Literature

Our citation search protocol identified 80 articles that cited the results from the 26-wk double-blind phase [39] and 48 articles that cited the results of the 74-wk extension phase [40]. After eliminating duplicates, the two publications from the Keck trial garnered 104 subsequent citations in total. Of these citing articles, 24 did not contain any mention of the Keck trial in relation to long-term or maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder and were excluded from further analysis (Figure 4). Double-coding revealed a high degree of inter-rater agreement on the quality assessment measures. There was 100% agreement on whether the publications were classified as mentioning aripiprazole for maintenance treatment. Among the double-coded publications mentioning maintenance treatment, there was 100% agreement on whether quantitative data and limitations were mentioned. There was one disagreement about whether adverse events were mentioned, yielding a kappa coefficient of 0.75 (95% CI 0.05–0.95). The overall kappa coefficient was 0.95 (95% CI 0.73–0.99).

Of the 80 articles that cited the Keck trial in reference to maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder, only 20 (25%) presented any quantitative data from the Keck trial; the remainder reported qualitative statements only (e.g., “Aripiprazole significantly delayed the time to relapse into a new mood episode in patients with bipolar I disorder over both 26 and 100 weeks of treatment.” [87]). 24 publications (30%) mentioned any of the adverse events reported in the trial. Only four (5%) made any mention of study limitations.

Among the articles identified through our citation search protocol were eight literature reviews [88]–[95] and three bipolar treatment guidelines [15],[96],[97] that specifically discussed the use of aripiprazole in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Because review articles and treatment guidelines can be particularly influential in shaping policy and prescribing behavior, we chose to highlight these in our discussion (Table 1). The evidence summaries employed the methodologies of consensus panel (n = 3), narrative review (n = 6), or systematic review (n = 2). Ten of the 11 reviews and treatment guidelines contained a financial disclosure related to Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Overall, the eight reviews were favorable in their assessment as to the putative efficacy of aripiprazole in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Solely on the basis of the results of the Keck trial, the Texas Medication Algorithm Project update listed aripiprazole as having “level 2” evidence (out of five levels of quality, with level 1 being the highest-quality) for maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder [15]. The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments and International Society for Bipolar Disorders recommended aripiprazole as first-line maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder, although it is noted that this is “mainly for preventing mania” (p. 235) [96]. This treatment recommendation was based on the Keck trial, along with a 30-wk pediatric bipolar trial that has only been published in abstract form [98]. The British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) based its positive endorsement of aripiprazole for relapse prevention solely on the Keck trial [97]. Contrary to the criticisms we described earlier, the BAP guidelines note, “Acute withdrawal of the active agent did not produce an excess of early relapse in this study” (p. 26).

Discussion

Our evaluation of the evidence base supporting the use of aripiprazole for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder reveals that the justification for this practice relies on the results from a single trial by Keck and colleagues published in two peer-reviewed journal articles [39],[40]. The methodology and reporting of the Keck trial are such that the results cannot be generalized to inform the treatment of most patients with bipolar disorder. Published interpretations of the data notwithstanding, in our opinion the Keck trial does not provide data to support the use of aripiprazole in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. This lack of robust evidence of benefit should be weighed against the potential for long-term harms that have been described with other antipsychotic medications [3] and adverse events related to aripiprazole use, including tremor, akathisia, and significant weight gain [39]. Our concern about the critical imitations in this trial is further accentuated by the apparent widespread use of aripiprazole as a first-line agent for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder [31],[32].

Although we appreciate that the unique clinical features of bipolar disorder make controlled study extremely difficult [67],[84],[99]–[103], many of the weaknesses we document stem from the use of the randomized discontinuation design. Further study is needed in order to determine whether the problems described in this particular case are also more widely applicable to other continuation or maintenance treatment studies in bipolar disorder. We find unpersuasive the argument that a randomized discontinuation study such as this is valuable because it reflects common clinical practice [104],[105]. The two-arm, parallel randomized controlled trial may yield information that is more clinically useful than the discontinuation design. Under the parallel design, data from all participants (not just those who demonstrated an acute response) would contribute to our understanding of the drug's short - and long-term efficacy: one of two medications (or placebo) would be given to participants in the acute phase, and they would be followed throughout the continuation and maintenance phases (and beyond) to document response to treatment. (This study design, as well as the other study designs we describe, clearly could be used to study nonpharmacological treatments, including evidence-based psychotherapies. However, because this paper has emphasized discussion about pharmacologic treatments, we use the phrase “medication” for simplicity.) A two-arm, parallel randomized controlled trial of sufficient duration would directly answer the substantive research question, “Does aripiprazole treat symptoms to remission and prevent recurrent episodes when given to patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder presenting in a manic or mixed state?” This is clearly different from the question answered by the discontinuation design, “Among patients diagnosed with bipolar presenting in a manic or mixed state who have achieved a reasonable symptomatic improvement after being given aripiprazole, should aripiprazole be continued to maintain the initial improvement?” [106].

The primary disadvantage of the parallel design is that a greater proportion of (acutely ill) study participants would be subjected to placebo for the full duration of the trial, exactly the ethical issue that the discontinuation design was intended to address [107],[108]. Keck et al. [39] stated that they sought to minimize the extent to which stabilized participants were administered placebo. Yet their study could have been modified to diminish its exposure to the weaknesses that we have described above. First, the duration of stability required prior to randomization could be lengthened. One likely cost of this design modification is that the proportion of participants actually randomized would decrease further [109]. A second modification would be to gradually taper the discontinuation of medication among participants randomized to receive placebo. In previously published randomized discontinuation studies, medications administered during the open-label phase were tapered over a period of 2 to 3 wk rather than abruptly discontinued [47],[83]. Greenhouse et al. [59] suggest implementing the taper over several months.

Aside from these modifications to the parallel design, other alternatives have been suggested. Greenhouse et al. [59] proposed an alternative randomization scheme in which study participants are randomized to one of six treatment strategies. In the acute phase of treatment, study participants would receive one of two medications. In the maintenance phase of treatment, study participants would either remain on the medication initiated during the acute phase, be switched (gradually) to the alternative medication, or be switched (gradually) to placebo. This innovative study design would address the substantive research question, “Which treatment strategy is better in controlling and preventing the recurrence of depression?” (p. 318) [59]. A pure prophylactic design has also been recommended [10],[12],[100], in which patients previously diagnosed with a recurrent mood disorder would be enrolled during a medication-free remission period. Then, while participants are in remission, they would be offered one of two medications (or placebo). All participants would be followed in the study for a prespecified duration, and the treatment arms would be compared in terms of time to recurrence of a mood episode. This design would avoid the previously described error of possibly conflating beneficial treatment effects with iatrogenic adverse effects of abrupt medication discontinuation. However, as noted by Goodwin, Whitman, and Ghaemi [12], the failure of the divalproex study by Bowden et al. [83] was partly attributed to its enrollment of participants with low severity of illness [84]—and it was the last study to utilize the lithium-era prophylaxis design.

We recognize that the proposed study designs will be regarded by some as too costly or infeasible. Although some have suggested that a study with selected limitations may be useful in guiding clinical practice [104], we would disagree with this argument. The current “anti-Hippocratic” state of psychopharmacological practice described by Ghaemi [56],[110] raises questions about the extent to which research with substantive limitations is appropriately interpreted with conservative sensibilities. These concerns are borne out in our data. Thomson Reuters Essential Science Indicators(SM) places the 26-wk double-blind phase publication in the top 1%, and the 74-wk extension phase publication in the top 1%–2%, of papers published in the fields of psychiatry and psychology. Thus, by our conservative estimates, the Keck trial could be regarded as relatively influential. More importantly, we found that the Keck trial was cited uncritically by a subsequent generation of authors, through treatment guidelines, reviews, and other publications. All failed to note the consequences of abrupt and premature discontinuation of antimanic medication, especially during the vulnerable continuation period. The uncritical manner in which the Keck trial has been cited is reminiscent of the “echo chamber” effect described by Carey et al. [111] in their assessment of the now-discredited use of gabapentin in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Although the analogy is somewhat limited as there were no reportedly positive double-blind trials examining the use of gabapentin for this indication, we document a similar pattern of uncritical citations of the primary evidence regarding aripiprazole in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.

Of further concern regarding the uncritical citation of the Keck trial's claims is that ten of the 11 treatment guidelines and review articles in our sample contained a financial disclosure related to the drug's manufacturer, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. Financial conflicts of interest are highly prevalent across a wide range of medical subfields [112], and while they are known to be associated with recommendations in review articles [113], there is no systematic research documenting their influence on clinical practice guideline recommendations [114]. However, financial conflicts of interest have been found to be associated with biased reporting of outcomes in randomized trials [115],[116], which serve as the evidence upon which treatment guideline recommendations are based.

In summary, we provide here a critical appraisal of the available evidence regarding the use of aripiprazole for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. The available evidence consists of a single trial by Keck et al. [39],[40], which is subject to several substantive methodological limitations but has nonetheless been cited uncritically in the ensuing scientific literature. Several alternative modifications or study designs may improve the probability of generating more useful data from studies in this vulnerable patient population to inform the treatment of similar patients in the future. We are concerned that the publication and apparently uncritical acceptance of this trial may be diverting patients away from more effective treatments.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Tohen

M

Jacobs

TG

Feldman

PD

2000

Onset of action of antipsychotics in the treatment of

mania.

Bipolar Disord

2

261

268

2. Wolfsperger

M

Greil

W

Rossler

W

Grohmann

R

2007

Pharmacological treatment of acute mania in psychiatric

in-patients between 1994 and 2004.

J Affect Disord

99

9

17

3. Healy

D

2006

The latest mania: selling bipolar disorder.

PLoS Med

3

e185

doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030185

4. Malhi

GS

Adams

D

Berk

M

2009

Medicating mood with maintenance in mind: bipolar depression

pharmacotherapy.

Bipolar Disord

11

Suppl 2

55

76

5. Spielmans

GI

Parry

PI

2010

From evidence-based medicine to marketing-based medicine:

evidence from internal industry documents.

J Bioeth Inquiry

7

13

29

6. Healy

D

2010

From mania to bipolar disorder.

Yatham

LN

Maj

M

Bipolar disorder: clinical and neurobiological foundations

Oxford

John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

1

7

7. Mark

TL

2010

For what diagnoses are psychotropic medications being

prescribed?: a nationally representative survey of

physicians.

CNS Drugs

24

319

326

8. Depp

C

Ojeda

VD

Mastin

W

Unutzer

J

Gilmer

TP

2008

Trends in use of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers among

Medicaid beneficiaries with bipolar disorder, 2001-2004.

Psychiatr Serv

59

1169

1174

9. Frank

E

Prien

RF

Jarrett

RB

Keller

MB

Kupfer

DJ

1991

Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of

terms in major depressive disorder. Remission, recovery, relapse, and

recurrence.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

48

851

855

10. Storosum

JG

van Zwieten

BJ

Vermeulen

HD

Wohlfarth

T

van den Brink

W

2001

Relapse and recurrence prevention in major depression: a critical

review of placebo-controlled efficacy studies with special emphasis on

methodological issues.

Eur Psychiatry

16

327

335

11. Ghaemi

SN

Pardo

TB

Hsu

DJ

2004

Strategies for preventing the recurrence of bipolar

disorder.

J Clin Psychiatry

65

Suppl 10

16

23

12. Goodwin

FK

Whitham

EA

Ghaemi

SN

2011

Relapse prevention in bipolar disorder: have any neuroleptics

been shown to be ‘mood stabilizers’?

CNS Drugs

In press

13. Sachs

GS

1996

Bipolar mood disorder: practical strategies for acute and

maintenance phase treatment.

J Clin Psychopharmacol

16

32S

47S

14. Sachs

GS

Printz

DJ

Kahn

DA

Carpenter

D

Docherty

JP

2000

The expert consensus guideline series: medication treatment of

bipolar disorder 2000.

Postgrad Med Spec No

1

104

15. Suppes

T

Dennehy

EB

Hirschfeld

RM

Altshuler

LL

Bowden

CL

2005

The Texas implementation of medication algorithms: update to the

algorithms for treatment of bipolar I disorder.

J Clin Psychiatry

66

870

886

16. Perlis

RH

Welge

JA

Vornik

LA

Hirschfeld

RM

Keck PE Jr.

2006

Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of mania: a

meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

J Clin Psychiatry

67

509

516

17. Scherk

H

Pajonk

FG

Leucht

S

2007

Second-generation antipsychotic agents in the treatment of acute

mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled

trials.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

64

442

455

18. Vieta

E

Sanchez-Moreno

J

2008

Acute and long-term treatment of mania.

Dialogues Clin Neurosci

10

165

179

19. Bauer

MS

Mitchner

L

2004

What is a “mood stabilizer”? An evidence-based

response.

Am J Psychiatry

161

3

18

20. Ghaemi

SN

2001

On defining ‘mood stabilizer’.

Bipolar Disord

3

154

158

21. Goodwin

FK

Jamison

KR

2007

Manic-depressive illness: bipolar disorders and recurrent

depression.

New York

Oxford University Press

22. Suppes

T

Vieta

E

Liu

S

Brecher

M

Paulsson

B

2009

Maintenance treatment for patients with bipolar I disorder:

results from a north american study of quetiapine in combination with

lithium or divalproex (trial 127).

Am J Psychiatry

166

476

488

23. Geddes

JR

Goodwin

GM

Rendell

J

Azorin

JM

Cipriani

A

2010

Lithium plus valproate combination therapy versus monotherapy for

relapse prevention in bipolar I disorder (BALANCE): a randomised open-label

trial.

Lancet

375

385

395

24. Ghaemi

SN

Hsu

DJ

Thase

ME

Wisniewski

SR

Nierenberg

AA

2006

Pharmacological treatment patterns at study entry for the first

500 STEP-BD participants.

Psychiatr Serv

57

660

665

25. Lim

PZ

Tunis

SL

Edell

WS

Jensik

SE

Tohen

M

2001

Medication prescribing patterns for patients with bipolar I

disorder in hospital settings: adherence to published practice

guidelines.

Bipolar Disord

3

165

173

26. Frangou

S

Raymont

V

Bettany

D

2002

The Maudsley bipolar disorder project. A survey of psychotropic

prescribing patterns in bipolar I disorder.

Bipolar Disord

4

378

385

27. Blanco

C

Laje

G

Olfson

M

Marcus

SC

Pincus

HA

2002

Trends in the treatment of bipolar disorder by outpatient

psychiatrists.

Am J Psychiatry

159

1005

1010

28. Tohen

M

Baraibar

G

Kando

JC

Mirin

J

Zarate CA Jr.

1995

Prescribing trends of antidepressants in bipolar

depression.

J Clin Psychiatry

56

260

264

29. U.S. Food and Drug Administration

2005

Approval package for 21-436/S-005 & S-008 &

21-713/S-003.

Rockville (Maryland)

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

30. IMS Health

2010

Top 15 U.S. pharmaceutical products by sales. IMS National Sales

Perspectives(TM).

Norwalk

IMS Health

31. Chow

ST

von Loesecke

A

Hohenberg

KW

Epstein

M

Buurma

AK

2008

Brands and strategies: atypical antipsychotics.

Waltham (Massachusetts)

Decision Resources, Inc

32. Diak

I

Mehta

H

2008

New Molecular Entity review follow-up:

aripiprazole.

Rockville (Maryland)

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

33. Cuttler

L

Silvers

JB

Singh

J

Tsai

AC

Radcliffe

D

2005

Physician decisions to discontinue long-term medications using a

two-stage framework: the case of growth hormone therapy.

Med Care

43

1185

1193

34. Levit

K

Smith

C

Cowan

C

Lazenby

H

Sensenig

A

2003

Trends in U.S. health care spending, 2001.

Health Aff (Millwood)

22

154

164

35. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company

2010

Clinical trials registry.

New York

Bristol Myers Squibb Co

36. Gidiere

S

2006

The federal information manual.

Chicago

American Bar Association

37. Moynihan

R

Bero

L

Ross-Degnan

D

Henry

D

Lee

K

2000

Coverage by the news media of the benefits and risks of

medications.

N Engl J Med

342

1645

1650

38. Fleiss

J

1981

Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd

edition.

New York

Wiley

39. Keck

PE

Jr

Calabrese

JR

McQuade

RD

Carson

WH

Carlson

BX

2006

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 26-week trial of

aripiprazole in recently manic patients with bipolar I

disorder.

J Clin Psychiatry

67

626

637

40. Keck

PE

Jr

Calabrese

JR

McIntyre

RS

McQuade

RD

Carson

WH

2007

Aripiprazole monotherapy for maintenance therapy in bipolar I

disorder: a 100-week, double-blind study versus placebo.

J Clin Psychiatry

68

1480

1491

41. Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

2010

A multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind investigative

extension trial of the safety and efficacy of aripiprazole in the treatment

of patients with bipolar disorder experiencing a manic or mixed episode

(NCT00606177).

Tokyo

Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd

42. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company

2008

A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

of aripiprazole monotherapy in the treatment of acutely manic patients with

bipolar I disorder (CN138-135LT).

New York

Bristol-Myers Squibb Co

43. Keck

PE

Orsulak

PJ

Cutler

AJ

Sanchez

R

Torbeyns

A

2009

Aripiprazole monotherapy in the treatment of acute bipolar I

mania: a randomized, double-blind, placebo - and lithium-controlled

study.

J Affect Disord

112

36

49

44. Muzina

DJ

Momah

C

Eudicone

JM

Pikalov

A

McQuade

RD

2008

Aripiprazole monotherapy in patients with rapid-cycling bipolar I

disorder: an analysis from a long-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled

study.

Int J Clin Pract

62

679

687

45. Keck

PE

Jr

Marcus

R

Tourkodimitris

S

Ali

M

Liebeskind

A

2003

A placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the efficacy and

safety of aripiprazole in patients with acute bipolar mania.

Am J Psychiatry

160

1651

1658

46. He

K

2004

Statistical review and evaluation. Center for Drug Evaluation and

Research approval package for 21-436/S-005 & S-008 &

21-713/S-003.

Rockville (Maryland)

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

47. Bowden

CL

Calabrese

JR

Sachs

G

Yatham

LN

Asghar

SA

2003

A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium

maintenance treatment in recently manic or hypomanic patients with bipolar I

disorder.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

60

392

400

48. Tohen

M

Calabrese

JR

Sachs

GS

Banov

MD

Detke

HC

2006

Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of olanzapine as maintenance

therapy in patients with bipolar I disorder responding to acute treatment

with olanzapine.

Am J Psychiatry

163

247

256

49. Calabrese

JR

Bowden

CL

Sachs

G

Yatham

LN

Behnke

K

2003

A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium

maintenance treatment in recently depressed patients with bipolar I

disorder.

J Clin Psychiatry

64

1013

1024

50. Angst

J

Sellaro

R

2000

Historical perspectives and natural history of bipolar

disorder.

Biol Psychiatry

48

445

457

51. Tohen

M

Frank

E

Bowden

CL

Colom

F

Ghaemi

SN

2009

The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Task Force

report on the nomenclature of course and outcome in bipolar

disorders.

Bipolar Disord

11

453

473

52. Ghaemi

SN

2010

From BALANCE to DSM-5: taking lithium seriously.

Bipolar Disord

12

673

677

53. Quitkin

FM

Rabkin

JG

1981

Methodological problems in studies of depressive disorder:

utility of the discontinuation design.

J Clin Psychopharmacol

1

283

288

54. Quitkin

F

Rifkin

A

Klein

DF

1976

Prophylaxis of affective disorders. Current status of

knowledge.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

33

337

341

55. Prodruchny

TA

2004

Clinical review. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research approval

package for 21-436/S-005 & S-008 & 21-713/S-003.

Rockville (Maryland)

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

56. Ghaemi

SN

2006

Hippocratic psychopharmacology for bipolar disorder: an

expert's opinion.

Psychiatry (Edgmont)

3

30

39

57. Deshauer

D

Fergusson

D

Duffy

A

Albuquerque

J

Grof

P

2005

Re-evaluation of randomized control trials of lithium

monotherapy: a cohort effect.

Bipolar Disord

7

382

387

58. Smith

LA

Cornelius

V

Warnock

A

Bell

A

Young

AH

2007

Effectiveness of mood stabilizers and antipsychotics in the

maintenance phase of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of randomized

controlled trials.

Bipolar Disord

9

394

412

59. Greenhouse

JB

Stangl

D

Kupfer

DJ

Prien

RF

1991

Methodologic issues in maintenance therapy clinical

trials.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

48

313

318

60. Wehr

TA

1990

Unnecessary confusion about opposite findings in two studies of

tricyclic treatment of bipolar illness.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

47

787

788

61. Sachs

GS

Thase

ME

2000

Bipolar disorder therapeutics: maintenance

treatment.

Biol Psychiatry

48

573

581

62. Shapiro

DR

Quitkin

FM

Fleiss

JL

1990

Unnecessary confusion about opposite findings in two studies of

tricyclic treatment of bipolar illness. Reply.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

47

788

63. Deshauer

D

Moher

D

Fergusson

D

Moher

E

Sampson

M

2008

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for unipolar depression:

a systematic review of classic long-term randomized controlled

trials.

CMAJ

178

1293

1301

64. Levenson

M

2008

Antiepileptic drugs and suicidality.

Rockville (Maryland)

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

65. Stone

M

Laughren

T

Jones

ML

Levenson

M

Holland

PC

2009

Risk of suicidality in clinical trials of antidepressants in

adults: analysis of proprietary data submitted to US Food and Drug

Administration.

BMJ

339

b2880

66. Calabrese

JR

Rapport

DJ

Shelton

MD

Kimmel

SE

2001

Evolving methodologies in bipolar disorder maintenance

research.

Br J Psychiatry

Suppl 41

s157

163

67. Calabrese

JR

Rapport

DJ

1999

Mood stabilizers and the evolution of maintenance study designs

in bipolar I disorder.

J Clin Psychiatry

60

Suppl 5

5

13; discussion 14-15

68. Lapierre

YD

Gagnon

A

Kokkinidis

L

1980

Rapid recurrence of mania following lithium

withdrawal.

Biol Psychiatry

15

859

864

69. Mander

AJ

Loudon

JB

1988

Rapid recurrence of mania following abrupt discontinuation of

lithium.

Lancet

2

15

17

70. Baldessarini

RJ

Suppes

T

Tondo

L

1996

Lithium withdrawal in bipolar disorder: implications for clinical

practice and experimental therapeutics research.

Am J Ther

3

492

496

71. Suppes

T

Baldessarini

RJ

Faedda

GL

Tondo

L

Tohen

M

1993

Discontinuation of maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder:

risks and implications.

Harv Rev Psychiatry

1

131

144

72. Faedda

GL

Tondo

L

Baldessarini

RJ

Suppes

T

Tohen

M

1993

Outcome after rapid vs gradual discontinuation of lithium

treatment in bipolar disorders.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

50

448

455

73. Baldessarini

RJ

1995

Risks and implications of interrupting maintenance psychotropic

drug therapy.

Psychother Psychosom

63

137

141

74. Baldessarini

RJ

Tondo

L

Faedda

GL

Suppes

TR

Floris

G

1996

Effects of the rate of discontinuing lithium maintenance

treatment in bipolar disorders.

J Clin Psychiatry

57

441

448

75. Baldessarini

RJ

Tondo

L

Ghiani

C

Lepri

B

2010

Illness risk following rapid versus gradual discontinuation of

antidepressants.

Am J Psychiatry

167

934

941

76. Suppes

T

Baldessarini

RJ

Faedda

GL

Tohen

M

1991

Risk of recurrence following discontinuation of lithium treatment

in bipolar disorder.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

48

1082

1088

77. Goodwin

GM

1994

Recurrence of mania after lithium withdrawal. Implications for

the use of lithium in the treatment of bipolar affective

disorder.

Br J Psychiatry

164

149

152

78. Franks

MA

Macritchie

KA

Mahmood

T

Young

AH

2008

Bouncing back: is the bipolar rebound phenomenon peculiar to

lithium? A retrospective naturalistic study.

J Psychopharmacol

22

452

456

79. Viguera

AC

Baldessarini

RJ

Hegarty

JD

van Kammen

DP

Tohen

M

1997

Clinical risk following abrupt and gradual withdrawal of

maintenance neuroleptic treatment.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

54

49

55

80. Baldessarini

RJ

Viguera

AC

1998

Medication removal and research in psychotic

disorders.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

55

281

283

81. Healy

D

2010

Treatment-induced stress syndromes.

Med Hypotheses

74

764

768

82. Geddes

JR

Burgess

S

Hawton

K

Jamison

K

Goodwin

GM

2004

Long-term lithium therapy for bipolar disorder: systematic review

and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Am J Psychiatry

161

217

222

83. Bowden

CL

Calabrese

JR

McElroy

SL

Gyulai

L

Wassef

A

2000

A randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and

lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder. Divalproex

Maintenance Study Group.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

57

481

489

84. Bowden

CL

Swann

AC

Calabrese

JR

McElroy

SL

Morris

D

1997

Maintenance clinical trials in bipolar disorder: design

implications of the divalproex-lithium-placebo study.

Psychopharmacol Bull

33

693

699

85. Coppen

A

Noguera

R

Bailey

J

Burns

BH

Swani

MS

1971

Prophylactic lithium in affective disorders. Controlled

trial.

Lancet

2

275

279

86. Prien

RF

Caffey EMJr., Klett CJ

1973

Prophylactic efficacy of lithium carbonate in manic-depressive

illness. Report of the Veterans Administration and National Institute of

Mental Health collaborative study group.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

28

337

341

87. Kemp

DE

Canan

F

Goldstein

BI

McIntyre

RS

2009

Long-acting risperidone: a review of its role in the treatment of

bipolar disorder.

Adv Ther

26

588

599

88. Fountoulakis

KN

Vieta

E

2009

Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in the treatment of bipolar

disorder: a systematic review.

Ann Gen Psychiatry

8

16

89. Muzina

DJ

2009

Treatment and prevention of mania in bipolar I disorder: focus on

aripiprazole.

Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat

5

279

288

90. McIntyre

RS

Woldeyohannes

HO

Yasgur

BS

Soczynska

JK

Miranda

A

2007

Maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder: a focus on

aripiprazole.

Expert Rev Neurother

7

919

925

91. McIntyre

RS

Soczynska

JK

Woldeyohannes

HO

Miranda

A

Konarski

JZ

2007

Aripiprazole: pharmacology and evidence in bipolar

disorder.

Expert Opin Pharmacother

8

1001

1009

92. McIntyre

RS

2010

Aripiprazole for the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder:

a review.

Clin Ther

32

Suppl 1

S32

38

93. Garcia-Amador

M

Pacchiarotti

I

Valenti

M

Sanchez

RF

Goikolea

JM

2006

Role of aripiprazole in treating mood disorders.

Expert Rev Neurother

6

1777

1783

94. Fagiolini

A

2008

Practical guidance for prescribing with aripiprazole in bipolar

disorder.

Curr Med Res Opin

24

2691

2702

95. Ulusahin

A

2008

Ikiuclu bozuklukta aripiprazol [Aripiprazole for the

treatment of bipolar disorder].

Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni [Bulletin of Clinical

Psychopharmacology]

18

S27

S34

96. Yatham

LN

Kennedy

SH

Schaffer

A

Parikh

SV

Beaulieu

S

2009

Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and

International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of

CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder:

update 2009.

Bipolar Disord

11

225

255

97. Goodwin

GM

2009

Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised

second edition—recommendations from the British Association for

Psychopharmacology.

J Psychopharmacol

23

346

388

98. Forbes

A

Findling

RL

Nyilas

M

Forbes

RA

Aurang

C

2008

Long-term efficacy of aripiprazole in pediatric patients with

bipolar I disorder.

New Research Abstracts; May 3-8 American Psychiatric

Association

297

99. Baldessarini

RJ

Tohen

M

Tondo

L

2000

Maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

57

490

492

100. Goodwin

GM

Malhi

GS

2007

What is a mood stabilizer?

Psychol Med

37

609

614

101. Bowden

CL

Calabrese

JR

Wallin

BA

Swann

AC

McElroy

SL

1995

Illness characteristics of patients in clinical drug studies of

mania.

Psychopharmacol Bull

31

103

109

102. Post

RM

Keck

P

Jr

Rush

AJ

2002

New designs for studies of the prophylaxis of bipolar

disorder.

J Clin Psychopharmacol

22

1

3

103. Prien

RF

Kupfer

DJ

1989

Outside analysis of a multicenter collaborative

study.

Arch Gen Psychiatry

46

462

464

104. Tohen

M

Lin

D

2006

Maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder.

Psychiatry (Edgmont)

3

43

45

105. Swann

AC

2006

Treating bipolar disorder: for the patient or against the

illness?

Psychiatry (Edgmont)

3

40

42

106. Mallinckrodt

C

Chuang-Stein

Štítky

Interné lekárstvo

Článek The Transit Phase of Migration: Circulation of Malaria and Its Multidrug-Resistant Forms in AfricaČlánek If You Could Only Choose Five Psychotropic Medicines: Updating the Interagency Emergency Health Kit

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2011 Číslo 5- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Statinová intolerance

- Genetický podklad a screening familiární hypercholesterolémie

- Metabolit živočišné stravy produkovaný střevní mikroflórou zvyšuje riziko závažných kardiovaskulárních příhod

- DESATORO PRE PRAX: Aktuálne odporúčanie ESPEN pre nutričný manažment u pacientov s COVID-19

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Primary Prevention of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Large-for-Gestational-Age Newborns by Lifestyle Counseling: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial

- Meta-analyses of Adverse Effects Data Derived from Randomised Controlled Trials as Compared to Observational Studies: Methodological Overview

- Effectiveness of Early Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation to Improve Survival among HIV-Infected Adults with Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study

- Characterizing the Epidemiology of the 2009 Influenza A/H1N1 Pandemic in Mexico

- The Joint Action and Learning Initiative: Towards a Global Agreement on National and Global Responsibilities for Health

- Let's Be Straight Up about the Alcohol Industry

- Advancing Cervical Cancer Prevention Initiatives in Resource-Constrained Settings: Insights from the Cervical Cancer Prevention Program in Zambia

- The Transit Phase of Migration: Circulation of Malaria and Its Multidrug-Resistant Forms in Africa

- Health Aspects of the Pre-Departure Phase of Migration

- Aripiprazole in the Maintenance Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: A Critical Review of the Evidence and Its Dissemination into the Scientific Literature

- Threshold Haemoglobin Levels and the Prognosis of Stable Coronary Disease: Two New Cohorts and a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- If You Could Only Choose Five Psychotropic Medicines: Updating the Interagency Emergency Health Kit

- Migration and Health: A Framework for 21st Century Policy-Making

- Maternal Influenza Immunization and Reduced Likelihood of Prematurity and Small for Gestational Age Births: A Retrospective Cohort Study

- The Impact of Retail-Sector Delivery of Artemether–Lumefantrine on Malaria Treatment of Children under Five in Kenya: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial

- Medical Students' Exposure to and Attitudes about the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Systematic Review

- Estimates of Outcomes Up to Ten Years after Stroke: Analysis from the Prospective South London Stroke Register

- Low-Dose Adrenaline, Promethazine, and Hydrocortisone in the Prevention of Acute Adverse Reactions to Antivenom following Snakebite: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

- PLOS Medicine

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Low-Dose Adrenaline, Promethazine, and Hydrocortisone in the Prevention of Acute Adverse Reactions to Antivenom following Snakebite: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

- Effectiveness of Early Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation to Improve Survival among HIV-Infected Adults with Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study

- Medical Students' Exposure to and Attitudes about the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Systematic Review

- Estimates of Outcomes Up to Ten Years after Stroke: Analysis from the Prospective South London Stroke Register

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy