-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Circulating Mitochondrial DNA in Patients in the ICU as a Marker of Mortality: Derivation and Validation

Background:

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a critical activator of inflammation and the innate immune system. However, mtDNA level has not been tested for its role as a biomarker in the intensive care unit (ICU). We hypothesized that circulating cell-free mtDNA levels would be associated with mortality and improve risk prediction in ICU patients.Methods and Findings:

Analyses of mtDNA levels were performed on blood samples obtained from two prospective observational cohort studies of ICU patients (the Brigham and Women's Hospital Registry of Critical Illness [BWH RoCI, n = 200] and Molecular Epidemiology of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome [ME ARDS, n = 243]). mtDNA levels in plasma were assessed by measuring the copy number of the NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene using quantitative real-time PCR. Medical ICU patients with an elevated mtDNA level (≥3,200 copies/µl plasma) had increased odds of dying within 28 d of ICU admission in both the BWH RoCI (odds ratio [OR] 7.5, 95% CI 3.6–15.8, p = 1×10−7) and ME ARDS (OR 8.4, 95% CI 2.9–24.2, p = 9×10−5) cohorts, while no evidence for association was noted in non-medical ICU patients. The addition of an elevated mtDNA level improved the net reclassification index (NRI) of 28-d mortality among medical ICU patients when added to clinical models in both the BWH RoCI (NRI 79%, standard error 14%, p<1×10−4) and ME ARDS (NRI 55%, standard error 20%, p = 0.007) cohorts. In the BWH RoCI cohort, those with an elevated mtDNA level had an increased risk of death, even in analyses limited to patients with sepsis or acute respiratory distress syndrome. Study limitations include the lack of data elucidating the concise pathological roles of mtDNA in the patients, and the limited numbers of measurements for some of biomarkers.Conclusions:

Increased mtDNA levels are associated with ICU mortality, and inclusion of mtDNA level improves risk prediction in medical ICU patients. Our data suggest that mtDNA could serve as a viable plasma biomarker in medical ICU patients.

Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Published in the journal: Circulating Mitochondrial DNA in Patients in the ICU as a Marker of Mortality: Derivation and Validation. PLoS Med 10(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001577

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001577Summary

Background:

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a critical activator of inflammation and the innate immune system. However, mtDNA level has not been tested for its role as a biomarker in the intensive care unit (ICU). We hypothesized that circulating cell-free mtDNA levels would be associated with mortality and improve risk prediction in ICU patients.Methods and Findings:

Analyses of mtDNA levels were performed on blood samples obtained from two prospective observational cohort studies of ICU patients (the Brigham and Women's Hospital Registry of Critical Illness [BWH RoCI, n = 200] and Molecular Epidemiology of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome [ME ARDS, n = 243]). mtDNA levels in plasma were assessed by measuring the copy number of the NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene using quantitative real-time PCR. Medical ICU patients with an elevated mtDNA level (≥3,200 copies/µl plasma) had increased odds of dying within 28 d of ICU admission in both the BWH RoCI (odds ratio [OR] 7.5, 95% CI 3.6–15.8, p = 1×10−7) and ME ARDS (OR 8.4, 95% CI 2.9–24.2, p = 9×10−5) cohorts, while no evidence for association was noted in non-medical ICU patients. The addition of an elevated mtDNA level improved the net reclassification index (NRI) of 28-d mortality among medical ICU patients when added to clinical models in both the BWH RoCI (NRI 79%, standard error 14%, p<1×10−4) and ME ARDS (NRI 55%, standard error 20%, p = 0.007) cohorts. In the BWH RoCI cohort, those with an elevated mtDNA level had an increased risk of death, even in analyses limited to patients with sepsis or acute respiratory distress syndrome. Study limitations include the lack of data elucidating the concise pathological roles of mtDNA in the patients, and the limited numbers of measurements for some of biomarkers.Conclusions:

Increased mtDNA levels are associated with ICU mortality, and inclusion of mtDNA level improves risk prediction in medical ICU patients. Our data suggest that mtDNA could serve as a viable plasma biomarker in medical ICU patients.

Please see later in the article for the Editors' SummaryIntroduction

Multidimensional scoring systems based on commonly measured clinical and physiologic parameters help to improve the prognostication of patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) [1]. Despite the improvement in prognostication there is a need to develop biomarkers that can help clinicians to further improve risk prediction for patients in the ICU [2]. While many biomarkers (>170) have been evaluated in various ICU subpopulations, few have been tested in large populations, or add substantially to the predictive value of multidimensional scoring systems [1]. Only a small number of biomarkers reflecting the severity of critical illness are commonly measured in clinical practice (e.g., lactate and procalcitonin) [3],[4]. Accumulating evidence suggests that cellular mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) levels are decreased [5],[6] and circulating cell-free mtDNA levels are increased in response to stimuli such as trauma [7] and microbial infection [8]–[10]. Moreover, mtDNA acts as a damage-associated molecular pattern [11] that can drive molecular processes, leading to inflammatory responses and organ injuries [7],[10],[12],[13]. Based on these findings we hypothesized that circulating cell-free mtDNA levels would be associated with mortality and would improve risk prediction in ICU patients. The objective of this study was to test whether measuring circulating cell-free mtDNA is useful as a biomarker in the ICU. To our knowledge this is the first study to provide replicated evidence that plasma mtDNA levels both are associated with mortality and improve risk prediction in the field of critical care illness.

Methods

The protocols for patient recruitment and data collection for the two patient cohorts, the Brigham and Women's Hospital Registry of Critical Illness (BWH RoCI, primary patient cohort) and the Molecular Epidemiology of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ME ARDS, replication cohort), have been described previously [14]–[16] and are discussed in detail in Text S1 in Supporting Information S1. In brief, from 24 July 2008 to 14 June 2011, 200 patients were prospectively recruited into the BWH RoCI study from the Brigham and Women's Hospital medical intensive care unit (MICU), for whom clinical phenotype data, including mortality, and blood plasma samples were subsequently collected. Acute kidney injury was defined as a ≥0.5 mg/dl increase in serum creatinine [17]. Presence of respiratory, heart, and liver failure were defined by admitting physician report. For replication, we selected 243 patients from the ME ARDS study, which recruited patients from ICUs at Massachusetts General Hospital from 10 November 2002 to 16 June 2010 and at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center from 1 February 2007 to 24 April 2010, for whom both 28-d mortality data and a blood plasma sample had been collected. In addition to baseline demographic data, assessments of sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) were performed, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores were measured [18]–[20]. 28-d mortality [21] (in both cohorts) and in-hospital mortality (in the BWH RoCI cohort) were ascertained from patient medical records, and long-term mortality was assessed in the BWH RoCI cohort by linking the cohort to the US Social Security Administration's Death Master File [22]. Written informed consent and institutional review board approval were obtained.

Preparation and Quantification of Plasma DNA

In the BWH RoCI study, blood samples were drawn and transferred into blood collection tubes within 24 h of study inclusion, and processed within 2 h after venipuncture [14]. In the ME ARDS study, blood samples were drawn and transferred into blood collection tubes within 48 h after the establishment of a diagnosis [23].

DNA isolation from plasma

Plasma used in this study (from both RoCI and ME ARDS) was collected in EDTA-coated blood collection tubes. The plasma samples were stored at −80°C. DNA was isolated from plasma using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (#69504; Qiagen), according to the manufacture's manual [12]. Samples were thawed on ice and were then mixed briefly by vortex. The 100 µl of plasma was mixed with 100 µl of PBS, followed by brief vortex. The diluted plasma was centrifuged at 700g at 4°C for 5 min, and the supernatant (190 µl) was carefully saved by avoiding touching any pellets and the bottom of the tubes with pipette tips. The obtained supernatant was further centrifuged at 18,000g at 4°C for 15 min, and the resulting supernatant (170 µl) was carefully saved. Contamination of cells, cell debris, or pellets into supernatant might lead to a significant change of the results. The obtained supernatant was processed for DNA isolation. In brief, we incubated plasma samples with lysis buffer (included in the kit) and proteinase K at 56°C for 15 min. At the final step of DNA isolation, DNA was eluted in 200 µl of elution buffer (included in the kit). For the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay, the DNA solution was further diluted 10 times with nuclease-free deionized, distilled H2O.

Primers and qPCR

DNA level in diluted samples was measured by SYBR Green dye-based qPCR assay using a PRISM 7300 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The primer sequences were as follows: human NADH dehydrogenase 1 gene (mtDNA): forward 5′-ATACCCATGGCCAACCTCCT-3′, reverse 5′-GGGCCTTTGCGTAGTTGTAT-3′ [7],[24]; human β-globin (nuclear DNA): forward 5′-GTGCACCTGACTCCTGAGGAGA-3′, reverse 5′-CCTTGATACCAACCTGCCCAG-3′ [25]; bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA: forward 5′ - CGTCAGCTCGTGTTGTGAAA-3′, reverse 5′-GGCAGTCTCCTTGAGTTCC-3′ [7]. Plasmid DNA with complementary DNA sequences for human mtDNA was obtained from ORIGENE (SC101172), and plasmid DNA with complementary DNA sequences for human nuclear DNA was obtained from Sino Biological. Concentrations were converted to copy number using the formula; mol/gram×molecules/mol = molecules/gram, via a DNA copy number calculator (http://cels.uri.edu/gsc/cndna.html; University of Rhode Island Genomics and Sequencing Center) [26],[27]. DNA solutions were diluted in 10-fold serial dilutions and used as standards.

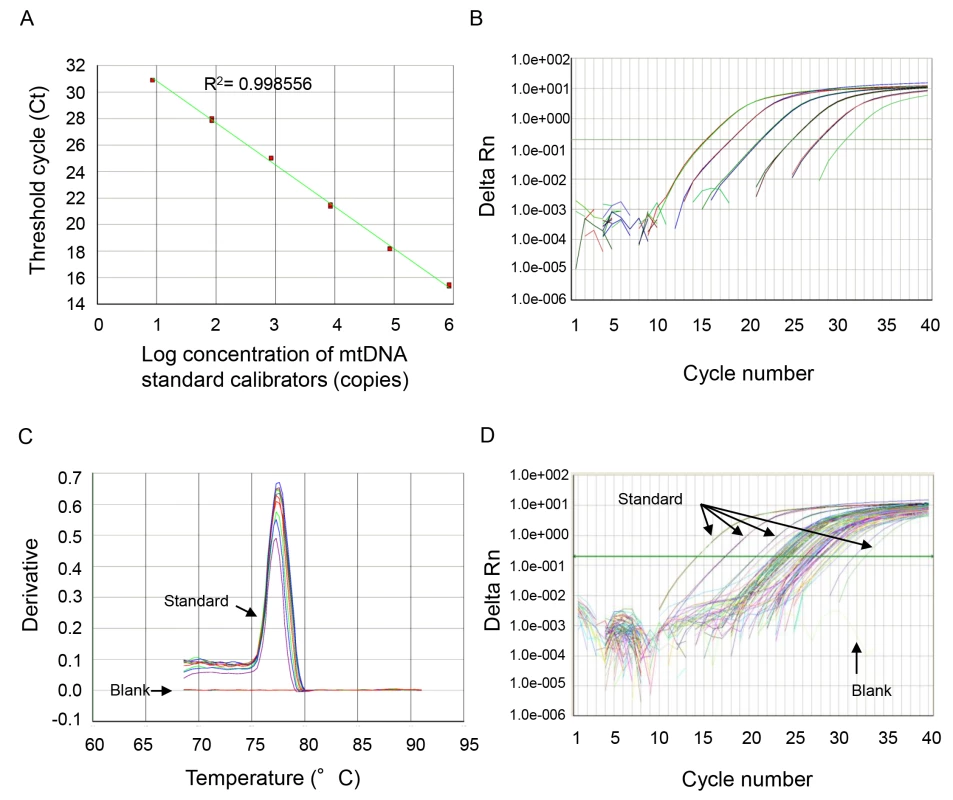

The thermal profile for detecting mtDNA was carried out as follows: an initiation step for 2 min at 50°C is followed by a first denaturation step for 10 min at 95°C and a further step consisting of 40 cycles for 15 s at 95°C and for 1 min at 60°C. A representative standard curve, dissociation curve, and amplification plot are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Representative standard curve, amplification plot, and dissociation curve, and amplification plot from the patients' samples.

(A) NADH dehydrogenase 1 complementary DNA was serially (1∶10) diluted to prepare a series of calibrators (mtDNA standard) with known DNA copy number. The assay was linear over the range (8.48–848000 copies) of DNA copy numbers (R2 = 0.997866). (B) The amplification plot (ΔRn versus cycle [log] view) shows no irregular amplification for the standard diluents (848,000, 84,800, 8,480, 848, 84.8, 8.48). (C) The dissociation curve shows a single melting temperature of the specific products generated with standard template. Also, there is no melting temperature observed in the no-template control wells (blank). These dissociation curves indicate that the reactions are free of primer-dimer or any other spurious products. (D) Similar amplification plots were observed after qPCR using patients' samples. The amplification curves generated from human samples were paralleled with the curves from standards and were in the range of amplification plots for standard diluents. All samples were analyzed in duplicate, and a no-template control was included in every analysis. mtDNA levels in all of the plasma analyses were expressed in copies per microliter of plasma based on the following calculation [28]:

where c is the concentration of DNA in plasma (copies/microliter plasma); Q is the quantity (copies) of DNA determined by the sequence detector in a PCR; VDNA is the total volume of plasma DNA solution obtained after extraction, typically 200 µl per extraction; VPCR is the volume of plasma DNA solution used for PCR, typically 5 µl of ten times diluted plasma DNA solution; and Vext is the volume of plasma extracted, typically 50–100 µl.The specificity of mtDNA primers was examined using bacterial DNA (Text S2 in Supporting Information S1; Figure S1) and by BLAST search (Text S3 and Tables S1 and S2 in Supporting Information S1).

Procalcitonin Measurement

Plasma level of procalcitonin was measured using the Procalcitonin Human ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) Kit (ab100630; Abcam).

Statistical Analysis

mtDNA level was assessed as both a continuous and a binary variable, where indicated. Because mtDNA levels were non-normally distributed, continuous levels from the BWH RoCI cohort were assessed after log10 transformation and dichotomized using visual inspection and iterative methods (using c-statistics) [29] to select the level of mtDNA that maximized the area under the curve for the prediction of 28-d mortality (mtDNA ≥3,200 copies/µl versus <3,200 copies/µl). This level was then replicated in the ME ARDS cohort. Survival was assessed as both a binary and a time-dependent variable. Bivariate analyses were conducted with Fisher's exact tests (for categorical variables) and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (for continuous variables). Both bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used in association analyses. Survival analyses were performed using log-rank and Cox-proportional hazards models.

To assess the value of mtDNA level in risk prediction, we compared bivariate and multivariate models with and without mtDNA level using the net reclassification improvement approach [30] (using risk categories in increments of 10% from 0% to 100%). In contrast to c-statistics, the net reclassification index (NRI) may have unique value in assessing the ability of a biomarker to improve risk prediction when groups can be split up into risk strata. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software version 9.2 (SAS Institute). Analyses comparing c-statistics and net reclassification were performed using rocplus [31]. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

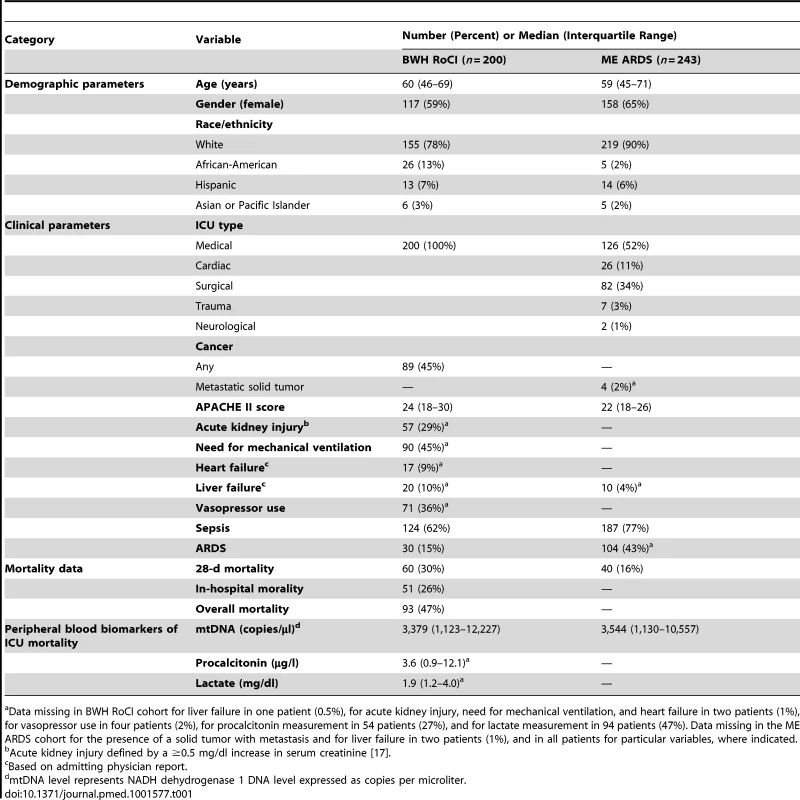

Baseline characteristics of ICU patients included in the BWH RoCI (n = 200) and the ME ARDS (n = 243) cohorts are presented in Table 1. While the BWH RoCI cohort was entirely composed of MICU patients, the ME ARDS cohort included patients from different ICU types. Patients in both studies were more likely to be white, to be female, and to carry a diagnosis of sepsis; however, these covariates were even more prevalent among patients in the ME ARDS cohort. A diagnosis of ARDS was more common in ME ARDS patients than in BWH RoCI patients. Age, APACHE II scores, and mtDNA levels were similar in both studies. Of note, only one patient in either study (in ME ARDS) received activated protein C during their stay in the ICU.

Tab. 1. Baseline characteristics of the ICU patients.

a Data missing in BWH RoCI cohort for liver failure in one patient (0.5%), for acute kidney injury, need for mechanical ventilation, and heart failure in two patients (1%), for vasopressor use in four patients (2%), for procalcitonin measurement in 54 patients (27%), and for lactate measurement in 94 patients (47%). Data missing in the ME ARDS cohort for the presence of a solid tumor with metastasis and for liver failure in two patients (1%), and in all patients for particular variables, where indicated. The additional analysis of patient characteristics is shown in Text S4 in Supporting Information S1.

Of the 200 patients in the BWH RoCI study, 60 (30%) died within 28 d of MICU admission, and 51 (25%) died in the hospital. The median follow-up time for the group that died in the hospital was 5 d (interquartile range 1–54 d). In the ME ARDS study, 40 patients (16%) died within 28 d of ICU admission. In the ME ARDS study, the rate of death among MICU patients (i.e., medical or cardiac ICU patients, n = 31 deaths, 20%) differed from that among non-MICU patients (i.e., surgical, trauma, or neurological ICU patients, n = 9 deaths, 10%, p = 0.03 for the difference). A majority of plasma samples were drawn within 4 d of ICU admission in both the BWH RoCI (n = 186, 93%) and the ME ARDS (n = 194, 90%, data missing on 34 patients) studies.

mtDNA Level and Mortality

BWH RoCI

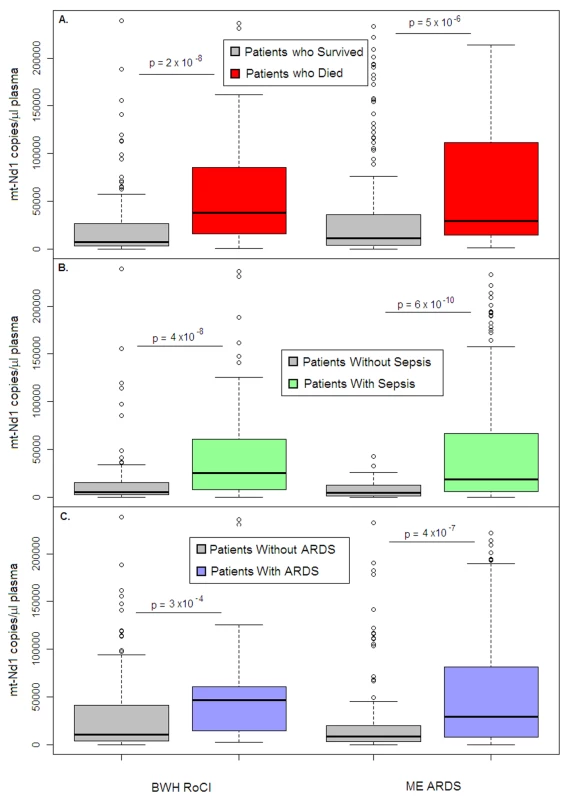

In the BWH RoCI cohort, mtDNA level was higher in ICU patients who died within 28 d of MICU admission than in those who did not (median 9,504 copies/µl versus 1,927 copies/µl, p = 2×10−8; Figure 2A), as well as in patients with diagnoses commonly associated with mortality in the ICU such as sepsis (Figure 2B) and ARDS (Figure 2C). For each log10-unit increase in mtDNA level, patients had an increased odds of dying within 28-d of MICU admission (odds ratio [OR] 1.9, 95% CI 1.5–2.4, p = 2×10−7). Patients with an mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl had an increased odds of dying within 28 d of MICU admission (Table 2) and an increased odds of dying in the hospital (OR 8.4, 95% CI 3.7–19.2, p = 4×10−7). Of those who died within 28 d of MICU admission, 80% (n = 48 of 60) had an mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl compared to 38% (n = 53 or 140) of those who did not die. In the BWH RoCI cohort, the odds of dying within 28 d of MICU admission was higher among those with an mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl when the level was obtained <48 h after ICU admission (n = 52, OR 23.0, 95% CI 4.4–120.0, p = 2×10−4) compared to those with an mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl that was obtained ≥48 h after ICU admission (n = 148, OR 4.4, 95% CI 1.9–9.8, p = 4×10−4); however, this difference was of borderline statistical significance (mtDNA by ICU status interaction p = 0.08). The additional analysis of nuclear DNA level and mtDNA level in different patient groups in the BWH RoCI study is shown in Texts S5 and S6 in Supporting Information S1.

Fig. 2. Cell-free mtDNA level in the plasma of ICU patients.

Boxplots comparing measures of cell-free mtDNA level (mtDNA [NADH dehydrogenase 1] expressed as copy number/µl of plasma) in the plasma of (A) patients who died within 28 d after ICU admission (red) versus those who survived (gray), (B) patients with (green) versus without (gray) sepsis, and (C) patients with (blue) versus without (gray) ARDS in the BWH RoCI (left) and ME ARDS (right) cohorts. mtDNA copy number in the plasma is presented as median value (black line), interquartile range (box), and 5th and 95th percentiles (whiskers). p-Values are noted in the figure for each cohort. Tab. 2. Bivariate and multivariate analyses of association between elevated mtDNA levels and 28-d MICU mortality.

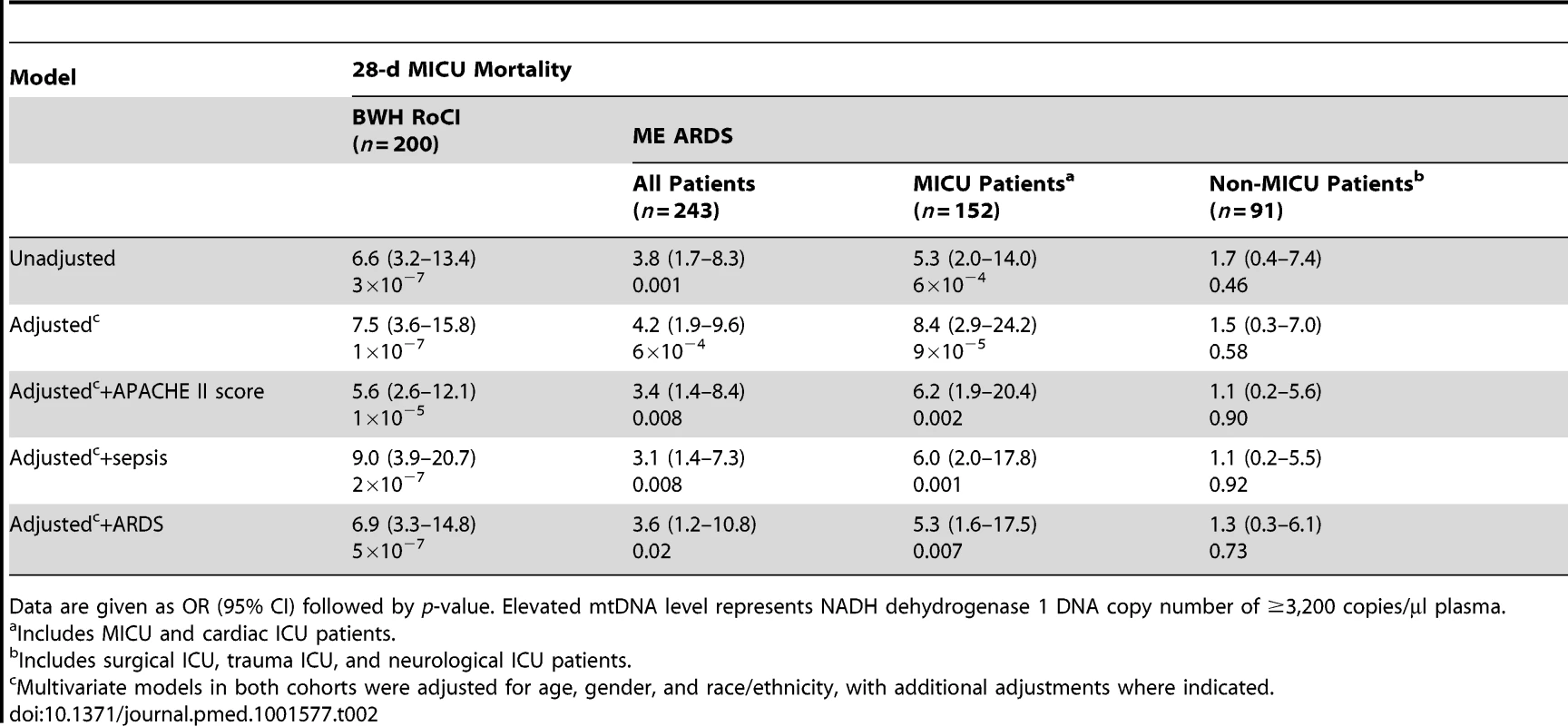

Data are given as OR (95% CI) followed by p-value. Elevated mtDNA level represents NADH dehydrogenase 1 DNA copy number of ≥3,200 copies/µl plasma. There was no evidence in the BWH RoCI cohort that the association between mtDNA level and MICU mortality was attenuated in models adjusted for clinical covariates, including APACHE II score, sepsis, or ARDS (Table 2). There was no statistical evidence that any of these variables significantly modified the effect of mtDNA level on mortality.

While an elevated mtDNA level was associated with acute kidney injury (OR 3.2, 95% CI 1.7–6.3, p = 4×10−4), the need for mechanical ventilation (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.5–4.8, p = 7×10−4), the use of vasopressors (OR 3.6, 95% CI 1.9–6.6, p = 6×10−5), and an underlying diagnosis of cancer (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.0–3.1, p = 0.05), there was no significant association of elevated mtDNA with physician report of either liver failure (p = 0.65) or heart failure (p = 0.45). The association between an elevated mtDNA level and 28-d mortality remained significant in the BWH RoCI cohort even after adjustment for additional variables including use of vasopressors, need for mechanical ventilation, cancer, acute kidney injury, or admitting physician impression of either heart or liver failure (OR 9.5, 95% CI 3.5–25.6, p = 3×10−5; see Table S3 in Supporting Information S1).

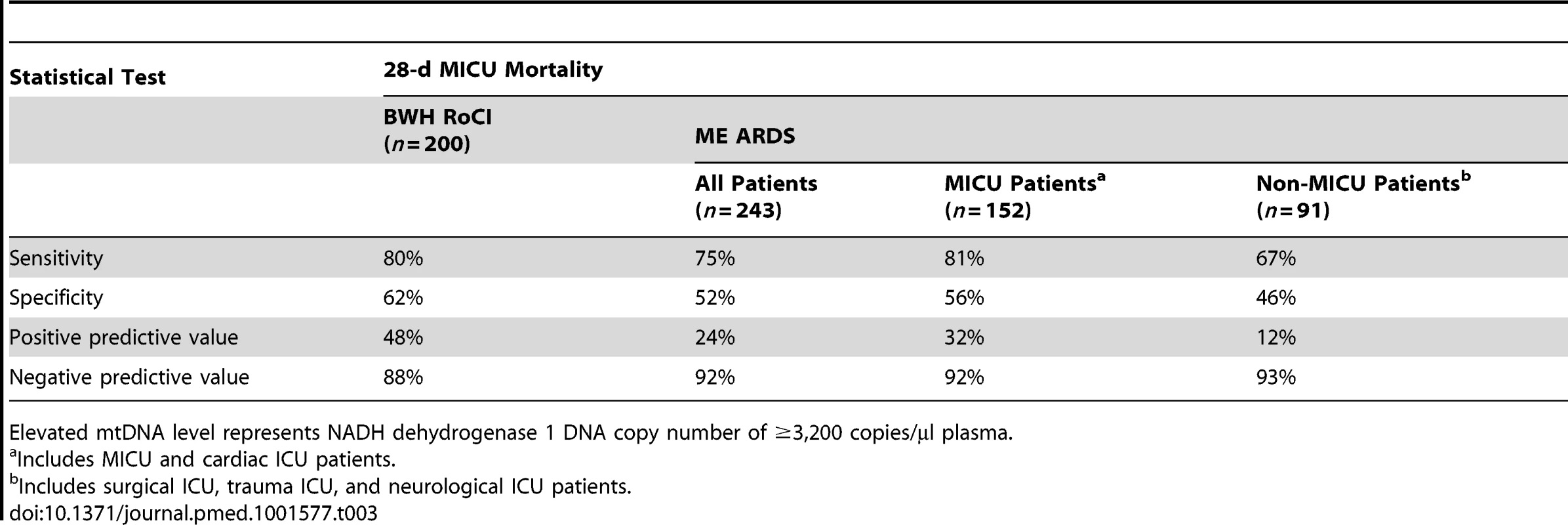

Binary classification analysis for elevated mtDNA levels and 28-d MICU mortality are shown in Table 3.

Tab. 3. Elevated mtDNA levels and 28-d MICU mortality by group.

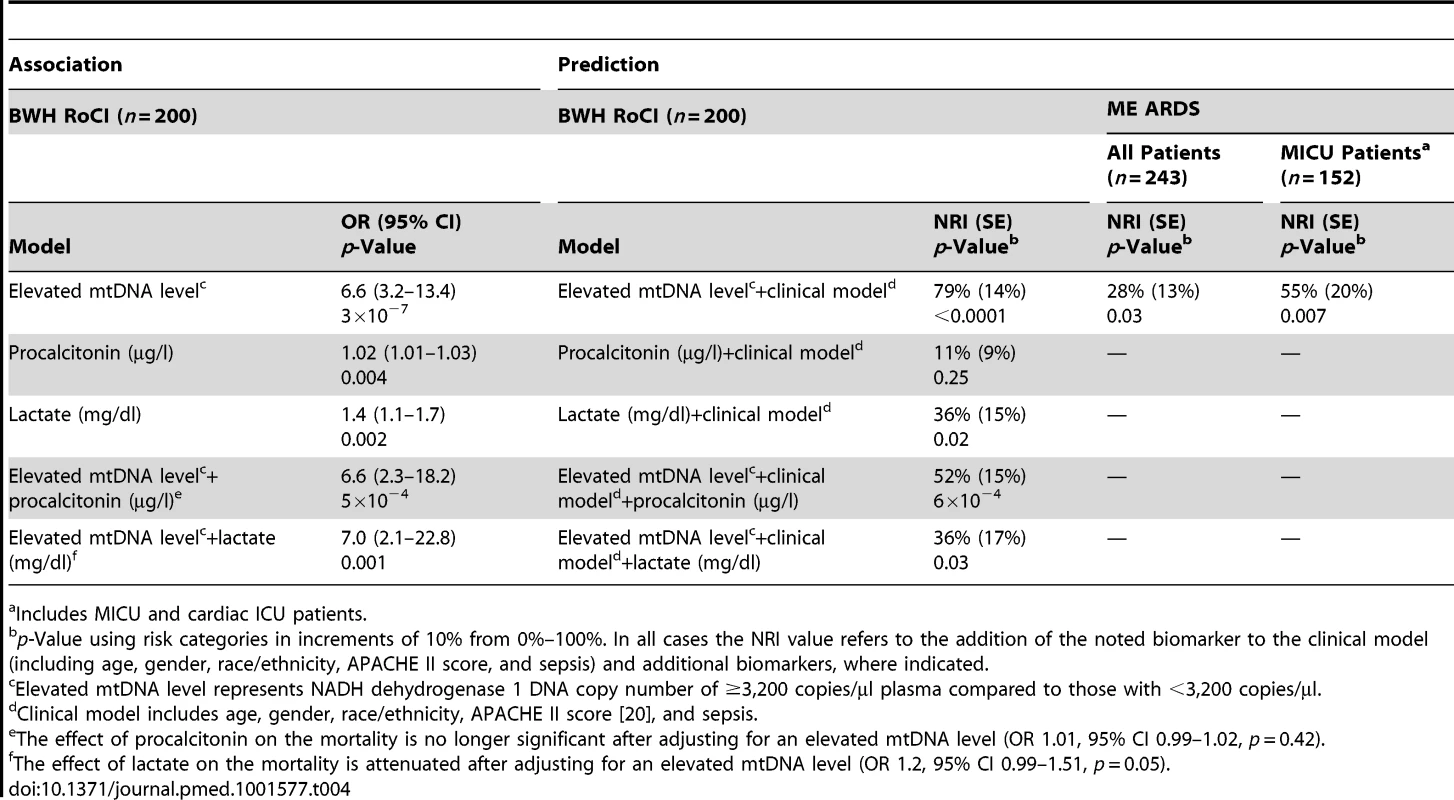

Elevated mtDNA level represents NADH dehydrogenase 1 DNA copy number of ≥3,200 copies/µl plasma. Of the 200 patients from the BWH RoCI cohort, we were able to obtain simultaneous measurements of procalcitonin in 146 (73%) and lactate in 106 (53%) patients. To determine whether the association between mtDNA and 28-d mortality could be explained by measures of procalcitonin or lactate, we tested each of these biomarkers for association with mortality and then assessed whether adjusting for either procalcitonin or lactate attenuates the association between mtDNA and mortality. All three biomarkers were significantly associated with 28-d mortality (Table 4). mtDNA level remained significantly associated with 28-d mortality even after adjusting for either procalcitonin or lactate. In contrast, the associations between procalcitonin and lactate and mortality were attenuated in models additionally adjusting for mtDNA level (Table 4).

Tab. 4. Peripheral blood biomarkers and 28-d ICU mortality.

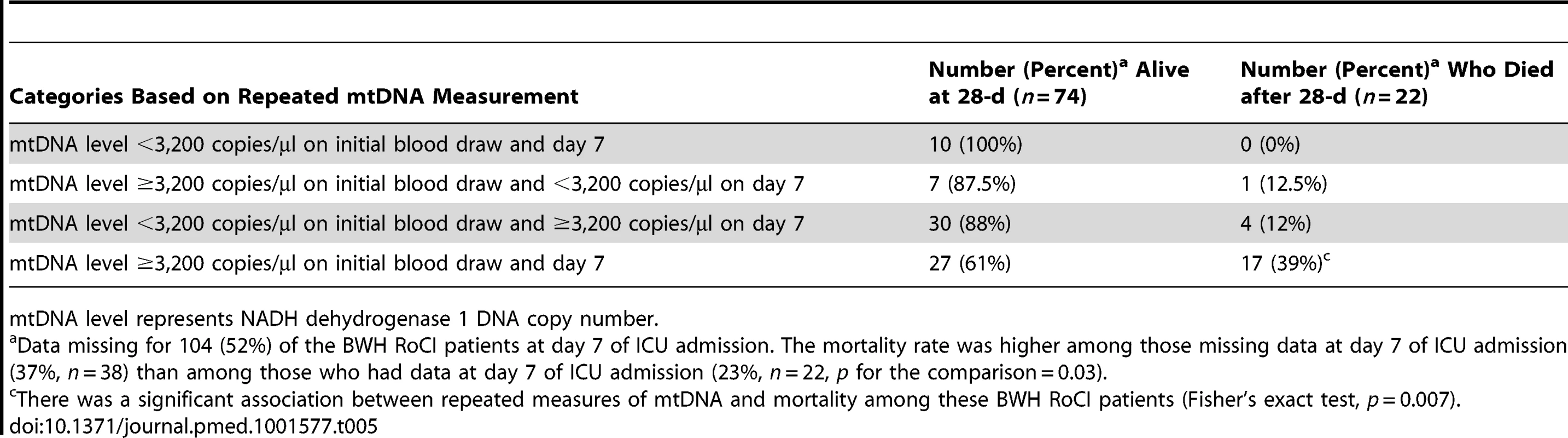

a Includes MICU and cardiac ICU patients. Of the 200 BWH RoCI patients, 96 (48%) remained in the ICU for 7 d and had a repeat measurement of mtDNA. Mortality level was lowest among patients with mtDNA levels <3,200/µl copies at both their initial blood draw and day 7 (0% mortality), highest in those with levels ≥3,200/µl copies at both visits (39% mortality), and intermediate for those with an elevated mtDNA level at only one of the two time points (∼12% mortality; see Table 5).

Tab. 5. Repeated measures of mtDNA and 28-d mortality in the BWH RoCI cohort.

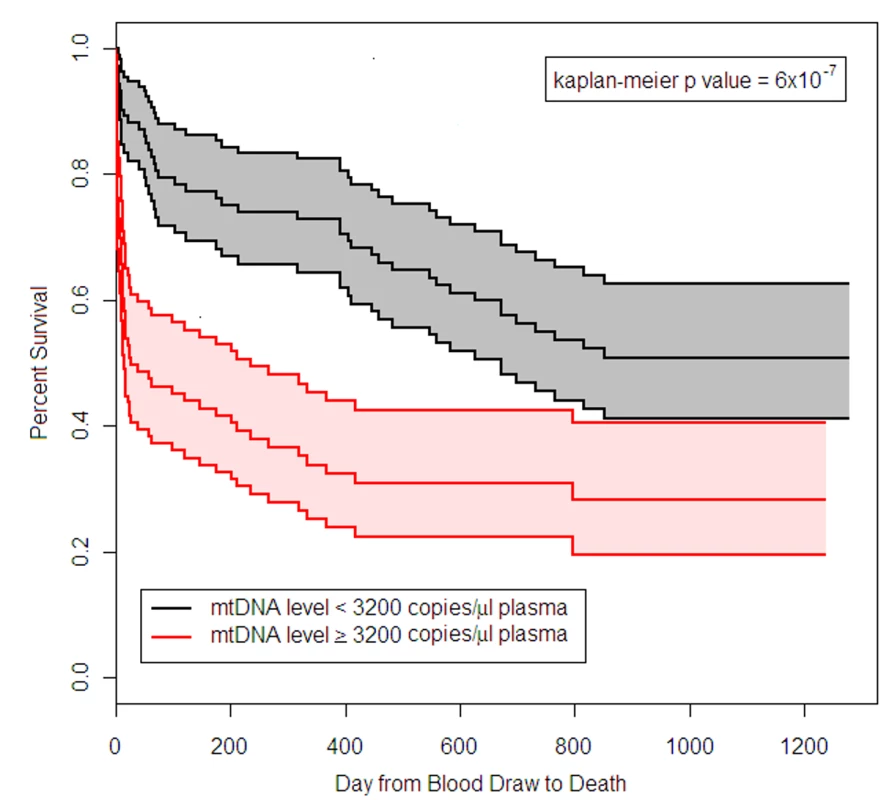

mtDNA level represents NADH dehydrogenase 1 DNA copy number. Follow-up data were available on the patients in the BWH RoCI study for periods ranging from 1 d to 3.5 y after admission to the ICU. 54% (n = 108) of the cohort died during follow-up. Patients who had an mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl had an increased risk of death (hazard ratio 2.4, 95% CI 1.6–3.6, p<1×10−4; see Figure 3). There was no evidence that the effect of mtDNA level on the risk of death was attenuated in adjusted models (Text S7 in Supporting Information S1). mtDNA level was associated with an increased risk of death even in analyses limited to patients with sepsis (after adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and APACHE II score, an mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl was associated with an increase in the risk of death, hazard ratio 3.0, 95% CI 1.5–6.3, p = 0.003) or ARDS (after adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and APACHE II score, an mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl was associated with a 2.3-fold increase in the risk of death, hazard ratio 2.3, 95% CI 1.5–3.5, p = 2×10−4).

Fig. 3. Survival of BWH RoCI MICU patients stratified by mtDNA level.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival for patients who had plasma mtDNA levels ≥3,200 copies/µl (n = 101) and <3,200 copies/µl (n = 99) in the BWH MICU. The middle black line indicates the Kaplan-Meier survival curve for patients who had mtDNA <3,200 copies/µl, with 95% confidence intervals (outer black lines and gray shading). The middle red line indicates the Kaplan-Meier survival curve for patients who had mtDNA ≥3,200 copies/µl, with 95% confidence intervals (outer red lines and pink shading). Survival in patients with mtDNA ≥3,200 copies/µl was significantly lower than in patients with mtDNA <3,200 copies/µl (p-value noted in the figure). ME ARDS

Comparable to our findings in the BWH RoCI cohort, mtDNA levels were higher in ME ARDS patients who died within 28 d of ICU admission (median 7,457 copies/µl) than in patients who did not (median 2,846 copies/µl, p = 5×10−6; Figure 2A), and were higher in patients with sepsis (Figure 2B) or ARDS (Figure 2C) than in patients without these conditions. Also similarly to the BWH RoCI cohort, for each log10-unit increase in mtDNA level, patients had an increased odds of dying within 28-d of ICU admission (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2–2.0, p = 9×10−4), those with an mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl had an increased odds of dying within 28 d of ICU admission (Table 2), and there was no evidence that the association between mtDNA level and ICU mortality was attenuated in models adjusted for covariates (Table 2).

In contrast to the BWH RoCI study, the ME ARDS study included ICU patients from non-medical ICUs (i.e., surgical, trauma, and neurological ICUs). In stratified analyses, the association between an elevated mtDNA level and 28-d mortality was limited to MICU patients. Importantly, there was no evidence for an association between mtDNA level and 28-d mortality in non-MICU patients (mtDNA by ICU status interaction 0.03; see Table 2).

mtDNA Level and 28-d Mortality Reclassification and Prediction

BWH RoCI

To further assess the importance of mtDNA as an ICU biomarker, we tested the ability of mtDNA level to improve reclassification of patients in the BWH RoCI cohort. The inclusion of mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl resulted in a 79% improvement in net reclassification when added to a clinical model (including age, gender, race/ethnicity, APACHE II score, and sepsis; see Table 4). The improvement in net reclassification remained significant, albeit attenuated, when mtDNA level was added to clinical models including known ICU biomarkers (e.g., procalcitonin or lactate; see Table 4). While measurement of lactate levels improved the reclassification of patients when added to a clinical model, measurement of procalcitonin did not (Table 4). In contrast, measurement of lactate did not improve reclassification when added to a clinical model that included mtDNA level (NRI 4%, standard error [SE] 14%, p = 0.80). Similarly, in the BWH RoCI cohort there was evidence that an mtDNA level of ≥3,200 copies/µl improved 28-d mortality prediction when added to a model with clinical variables using c-statistics (the c-statistic was 0.76, 95% CI 0.68–0.83, for a model including age, gender, race/ethnicity, APACHE II score, and sepsis, which improved to 0.83, 95% CI 0.77–0.90, with the inclusion of mtDNA level, p<0.001 for the comparison) (Figure 4A).

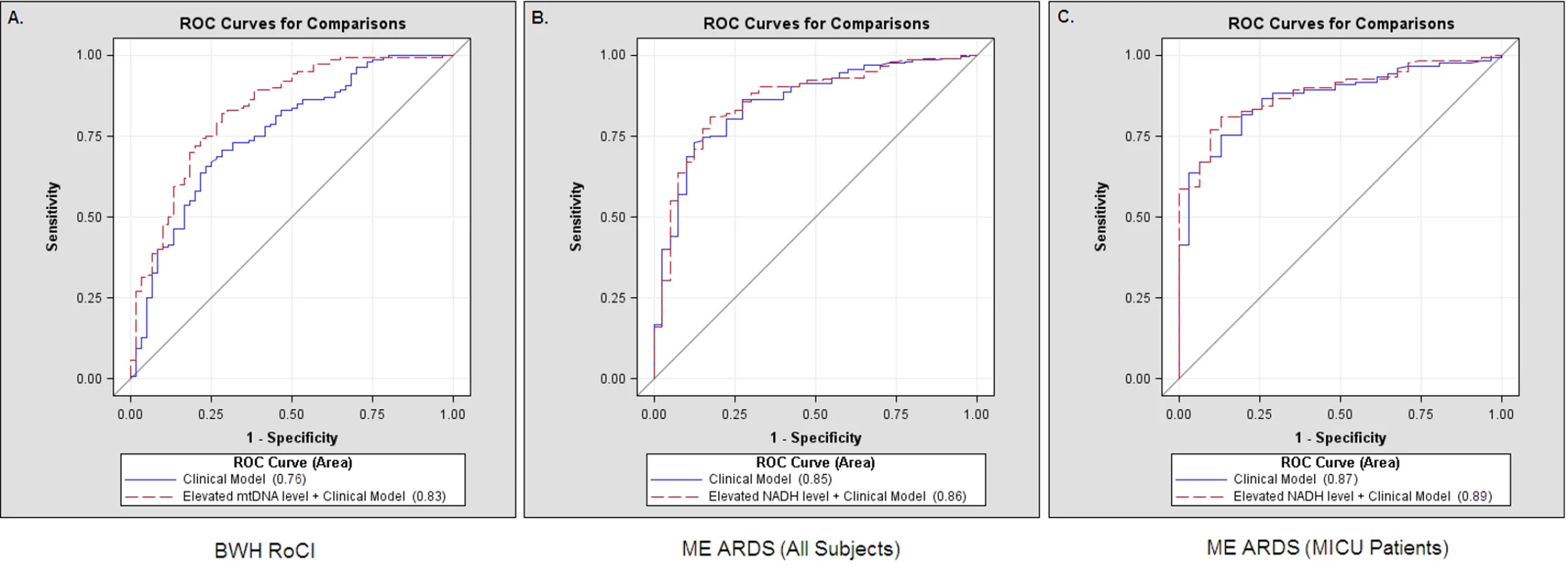

Fig. 4. Receiver operating characteristic curves, mtDNA, and death in ICU patients.

Comparisons of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for a clinical model (including age, gender, race/ethnicity, APACHE II score, and sepsis) (solid lines) and a clinical model with an mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl (dashed lines) to predict 28-d mortality in ICUs. (A) The area under the curve was 0.76 for a clinical model and was 0.83 for a clinical model with an mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl in the BWH RoCI cohort. (B) The area under the curve was 0.85 for a clinical model and was 0.86 for a clinical model with an mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl in the ME ARDS cohort when all patients were included. (C) The area under the curve was 0.87 for a clinical model and was 0.89 for a clinical model with an mtDNA level ≥3,200 copies/µl in the subpopulation of ME ARDS MICU patients. ME ARDS

Similar to our findings in the BWH RoCI cohort, the addition of an elevated mtDNA level improved net reclassification of ICU patients when added to a clinical model in the ME ARDS cohort (Table 4). The improvement in net reclassification in the ME ARDS cohort was due to the improvement in reclassifying MICU patients (Table 4), as no significant improvement was noted in non-MICU patients (NRI 4%, SE 16%, p = 0.82). Similarly, there was evidence that an mtDNA level of ≥3,200 copies/µl improved 28-d mortality prediction when added to a model with clinical variables using c-statistics (the c-statistic was 0.85, 95% CI 0.79–0.92, for a model including age, gender, and APACHE II score, which improved to 0.86, 95% CI 0.80–0.92, with the inclusion of mtDNA level, p = 0.02 for the comparison) in the ME ARDS cohort (Figure 4B), although improvement in prediction was limited to MICU patients (the c-statistic was 0.87, 95% CI 0.81–0.93, for a model including age, gender, and APACHE II score, which improved to 0.89, 95% CI 0.83–0.94, with the inclusion of mtDNA level, p = 0.008 for the comparison) (Figure 4C), as no significant improvement was noted in non-MICU patients (the c-statistic was 0.82 regardless of the inclusion of mtDNA level, p = 0.97 for the comparison).

Additional analyses combining both cohorts are presented in Text S8 and Table S4 in Supporting Information S1.

Discussion

Elevated levels of circulating cell-free mtDNA are associated with ICU mortality, particularly among MICU patients, from multiple cohorts. We demonstrate that mtDNA can improve risk prediction beyond commonly measured biomarkers, such as lactate, and combined measures of baseline characteristics and underlying physiology (e.g., APACHE II score) among MICU patients. In the BWH RoCI cohort, based primarily on the strength of the association between elevated mtDNA level and 28-day mortality, elevated mtDNA levels predicted an increased risk of death that persisted over up to 3.5 y of follow-up.

Based on the data we present in this study, it is not possible to determine whether the observed increased circulating cell-free mtDNA levels were increased as the result of the severity of illness alone, or whether mtDNA actively contributes to disease pathogenesis in MICU patients [32]–[34]. Recent observations [12] show that mtDNA contributes to activation of inflammasome, a large multimolecular complex that controls the proteolytic enzyme caspase-1 [33],[34]. Inflammasome activation is exclusively responsible for caspase-1-mediated IL-1β and IL-18 maturation and secretion in immune cells [33],[34], and circulating IL-1β and IL-18 levels are known to be increased in critically ill patients with both sepsis and ARDS [1],[14],[35]. These findings, in conjunction with the findings presented in here, suggest that circulating mtDNA could serve as a marker of death and, independently, may represent an important pathogenic determinant that contributes to an exaggerated systemic inflammatory response [36].

Our data are consistent with prior studies demonstrating that circulating cell-free mtDNA levels are elevated in critically ill subpopulations including adults with community-acquired bacterial meningitis [8], trauma [7], or sepsis in the emergency room [37], and further implicates the mitochondria, both in terms of genotyping (mtDNA haplogroups) [38] and now cell-free mtDNA plasma measurement, as an important factor predicting survival. In addition, our study demonstrates, to our knowledge for the first time, that elevated mtDNA levels may be particularly important in improving risk prediction in the MICU.

In addition to the evidence that elevated mtDNA levels are associated with sepsis, ARDS, and mortality, an important and unique aspect of our study is that we provide replicated evidence that mtDNA level improves risk prediction in MICU patients. Metrics of association and prediction should not be confused, as only the latter suggest that a finding may have clinical applicability as a test for an individual patient [39]. Although we present statistical evidence that mtDNA level improves our ability to predict death among MICU patients using both c-statistics and reclassification methods, it is important to note that some studies suggest that reclassification methods are more sensitive than c-statistics when comparing the magnitude of predictive improvement [30],[40].

Our study has a number of important limitations. First, although we demonstrate that an elevated mtDNA measurement is associated with ICU mortality among MICU patients from multiple cohorts, there was no evidence for a similar association among non-medical (predominantly surgical) ICU patients. Although we cannot definitively determine the reasons behind these differences within the context of this study, we can't rule out that subtle differences in the timing of sample collection could have influenced the associations within these two groups. In addition, these findings suggest that mtDNA could be released from cells or tissue as the result of surgery, and in this situation an elevated mtDNA level may be unlikely to be associated with an increased risk of mortality. Of note, although some studies demonstrate that patients who meet criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) have worse outcomes [41], this does not appear to hold among surgical ICU patients, where the presence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome is very common [42]. Second, some of the comparisons between biomarkers in the BWH RoCI study are limited because of missing data (e.g., lactate measurements). Third, although our assessments of repeated measures of mtDNA suggest that the trajectory of this measurement may be of clinical importance, we urge caution in interpreting these results, as our findings also demonstrate that the probability of being alive to have had mtDNA remeasured was also dependent on the initial mtDNA level. These findings support the idea that future studies of mtDNA in MICU patients could benefit from repeated measurements, including those prior to ICU presentation. Fourth, although fungemia was rare in both the BWH RoCI and ME ARDS cohorts (Text S4 in Supporting Information S1), it is worth noting that fungi have mtDNA that may cross-react with human mtDNA primers [10],[43]. Finally, it is important to note that our analyses reflect that the mtDNA level adds to, rather than replaces, information gleaned from commonly measured physiologic parameters and biomarkers.

In conclusion, we show that mtDNA level in plasma is associated with mortality in MICU patients. Elevated mtDNA level adds to mortality risk prediction in the ICU, and represents an advance over currently used ICU biomarkers and the APACHE score. Given the relative ease and rapidity (the entire process currently takes <6 h) of mtDNA measurement, circulating cell-free mtDNA could be a valuable addition to assessment of MICU patients, and points the way to the possibility of new diagnostic and/or therapeutic approaches for patients with critical illness.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. PierrakosC, VincentJL (2010) Sepsis biomarkers: a review. Crit Care 14: R15.

2. SchetzMR, Van den BergheG (2005) Do we have reliable biochemical markers to predict the outcome of critical illness? Int J Artif Organs 28 : 1197–1210.

3. AduenJ, BernsteinWK, KhastgirT, MillerJ, KerznerR, et al. (1994) The use and clinical importance of a substrate-specific electrode for rapid determination of blood lactate concentrations. JAMA 272 : 1678–1685.

4. Christ-CrainM, Jaccard-StolzD, BingisserR, GencayMM, HuberPR, et al. (2004) Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded intervention trial. Lancet 363 : 600–607.

5. PyleA, BurnDJ, GordonC, SwanC, ChinneryPF, et al. (2010) Fall in circulating mononuclear cell mitochondrial DNA content in human sepsis. Intensive Care Med 36 : 956–962.

6. SulimanHB, Welty-WolfKE, CarrawayMS, SchwartzDA, HollingsworthJW, et al. (2005) Toll-like receptor 4 mediates mitochondrial DNA damage and biogenic responses after heat-inactivated E. coli. FASEB J 19 : 1531–1533.

7. ZhangQ, RaoofM, ChenY, SumiY, SursalT, et al. (2010) Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature 464 : 104–107.

8. LuCH, ChangWN, TsaiNW, ChuangYC, HuangCR, et al. (2010) The value of serial plasma nuclear and mitochondrial DNA levels in adult community-acquired bacterial meningitis. QJM 103 : 169–175.

9. CossarizzaA, PintiM, NasiM, GibelliniL, ManziniS, et al. (2011) Increased plasma levels of extracellular mitochondrial DNA during HIV infection: a new role for mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns during inflammation. Mitochondrion 11 : 750–755.

10. SursalT, Stearns-KurosawaDJ, ItagakiK, OhSY, SunS, et al. (2013) Plasma bacterial and mitochondrial DNA distinguish bacterial sepsis from sterile systemic inflammatory response syndrome and quantify inflammatory tissue injury in nonhuman primates. Shock 39 : 55–62.

11. KryskoDV, AgostinisP, KryskoO, GargAD, BachertC, et al. (2011) Emerging role of damage-associated molecular patterns derived from mitochondria in inflammation. Trends Immunol 32 : 157–164.

12. NakahiraK, HaspelJA, RathinamVA, LeeSJ, DolinayT, et al. (2011) Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol 12 : 222–230.

13. CollinsLV, HajizadehS, HolmeE, JonssonIM, TarkowskiA (2004) Endogenously oxidized mitochondrial DNA induces in vivo and in vitro inflammatory responses. J Leukoc Biol 75 : 995–1000.

14. DolinayT, KimYS, HowrylakJ, HunninghakeGM, AnCH, et al. (2012) Inflammasome-regulated cytokines are critical mediators of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185 : 1225–1234.

15. GongMN, SaiY, ZhouW, ThompsonBT, XuLL, et al. (2003) Genotyping patients with recent blood transfusions. Epidemiology 14 : 744–747.

16. SheuCC, GongMN, ZhaiR, ChenF, BajwaEK, et al. (2010) Clinical characteristics and outcomes of sepsis-related vs non-sepsis-related ARDS. Chest 138 : 559–567.

17. ClermontG, AckerCG, AngusDC, SirioCA, PinskyMR, et al. (2002) Renal failure in the ICU: comparison of the impact of acute renal failure and end-stage renal disease on ICU outcomes. Kidney Int 62 : 986–996.

18. LevyMM, FinkMP, MarshallJC, AbrahamE, AngusD, et al. (2003) 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med 31 : 1250–1256.

19. BernardGR, ArtigasA, BrighamKL, CarletJ, FalkeK, et al. (1994) The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 149 : 818–824.

20. KnausWA, DraperEA, WagnerDP, ZimmermanJE (1985) APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 13 : 818–829.

21. AbrahamE, LaterrePF, GargR, LevyH, TalwarD, et al. (2005) Drotrecogin alfa (activated) for adults with severe sepsis and a low risk of death. N Engl J Med 353 : 1332–1341.

22. HillME, RosenwaikeI (2001) The Social Security Administration's Death Master File: the completeness of death reporting at older ages. Soc Secur Bull 64 : 45–51.

23. BajwaEK, KhanUA, JanuzziJL, GongMN, ThompsonBT, et al. (2009) Plasma C-reactive protein levels are associated with improved outcome in ARDS. Chest 136 : 471–480.

24. McGillMR, SharpeMR, WilliamsCD, TahaM, CurrySC, et al. (2012) The mechanism underlying acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in humans and mice involves mitochondrial damage and nuclear DNA fragmentation. J Clin Invest 122 : 1574–1583.

25. MoreiraVG, PrietoB, RodriguezJS, AlvarezFV (2010) Usefulness of cell-free plasma DNA, procalcitonin and C-reactive protein as markers of infection in febrile patients. Ann Clin Biochem 47 : 253–258.

26. NgaTV, KarkeyA, DongolS, ThuyHN, DunstanS, et al. (2010) The sensitivity of real-time PCR amplification targeting invasive Salmonella serovars in biological specimens. BMC Infect Dis 10 : 125.

27. Zozaya-HinchliffeM, MartinDH, FerrisMJ (2008) Prevalence and abundance of uncultivated Megasphaera-like bacteria in the human vaginal environment. Appl Environ Microbiol 74 : 1656–1659.

28. ChiuRW, ChanLY, LamNY, TsuiNB, NgEK, et al. (2003) Quantitative analysis of circulating mitochondrial DNA in plasma. Clin Chem 49 : 719–726.

29. HosmerDW, TaberS, LemeshowS (1991) The importance of assessing the fit of logistic regression models: a case study. Am J Public Health 81 : 1630–1635.

30. CookNR (2007) Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation 115 : 928–935.

31. May Clinic Division of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics (2013) Locally written SAS macros. Available: http://www.mayo.edu/research/departments-divisions/department-health-sciences-research/division-biomedical-statistics-informatics/software/locally-written-sas-macros. Accessed 23 August13.

32. van der VaartM, PretoriusPJ (2008) Circulating DNA. Its origin and fluctuation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1137 : 18–26.

33. DavisBK, WenH, TingJP (2011) The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu Rev Immunol 29 : 707–735.

34. Henao-MejiaJ, ElinavE, StrowigT, FlavellRA (2012) Inflammasomes: far beyond inflammation. Nat Immunol 13 : 321–324.

35. MakabeH, KojikaM, TakahashiG, MatsumotoN, ShibataS, et al. (2012) Interleukin-18 levels reflect the long-term prognosis of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Anesth 26 : 658–663.

36. EscamesG, LopezLC, GarciaJA, Garcia-CorzoL, OrtizF, et al. (2012) Mitochondrial DNA and inflammatory diseases. Hum Genet 131 : 161–173.

37. KungCT, HsiaoSY, TsaiTC, SuCM, ChangWN, et al. (2012) Plasma nuclear and mitochondrial DNA levels as predictors of outcome in severe sepsis patients in the emergency room. J Transl Med 10 : 130.

38. BaudouinSV, SaundersD, TiangyouW, ElsonJL, PoynterJ, et al. (2005) Mitochondrial DNA and survival after sepsis: a prospective study. Lancet 366 : 2118–2121.

39. KraftP, WacholderS, CornelisMC, HuFB, HayesRB, et al. (2009) Beyond odds ratios—communicating disease risk based on genetic profiles. Nat Rev Genet 10 : 264–269.

40. KathiresanS, MelanderO, AnevskiD, GuiducciC, BurttNP, et al. (2008) Polymorphisms associated with cholesterol and risk of cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 358 : 1240–1249.

41. Rangel-FraustoMS, PittetD, CostiganM, HwangT, DavisCS, et al. (1995) The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A prospective study. JAMA 273 : 117–123.

42. PittetD, Rangel-FraustoS, LiN, TararaD, CostiganM, et al. (1995) Systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock: incidence, morbidities and outcomes in surgical ICU patients. Intensive Care Med 21 : 302–309.

43. DowlerWM, ShawPD, GottliebD (1963) Terminal oxidation in cell-free extracts of fungii. J Bacteriol 86 : 9–17.

Štítky

Interné lekárstvo

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2013 Číslo 12- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Intermitentní hladovění v prevenci a léčbě chorob

- Statinová intolerance

- Co dělat při intoleranci statinů?

- Metabolit živočišné stravy produkovaný střevní mikroflórou zvyšuje riziko závažných kardiovaskulárních příhod

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Editors' Wishes for an Illuminated Season and an Open New Year

- Artemisinin Combination Therapy: A Good Antimalarial, but Is the Dose Right?

- Early HIV Infection in the United States: A Virus's Eye View

- Financial Conflicts of Interest and Reporting Bias Regarding the Association between Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Weight Gain: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews

- Investigating the Intersection of Policing and Public Health

- Improving Treatment of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: The Role of Non-specialist Care Providers

- Data Sharing in a Humanitarian Organization: The Experience of Médecins Sans Frontières

- Why Growing Retractions Are (Mostly) a Good Sign

- Challenges in Addressing Plagiarism in Education

- Experiences with Policing among People Who Inject Drugs in Bangkok, Thailand: A Qualitative Study

- Non-Specialist Psychosocial Interventions for Children and Adolescents with Intellectual Disability or Lower-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review

- Malaria and Severe Anemia: Thinking beyond

- Financing Essential HIV Services: A New Economic Agenda

- Timing and Completeness of Trial Results Posted at ClinicalTrials.gov and Published in Journals

- Circulating Mitochondrial DNA in Patients in the ICU as a Marker of Mortality: Derivation and Validation

- The Effect of Dosing Regimens on the Antimalarial Efficacy of Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine: A Pooled Analysis of Individual Patient Data

- Major Burden of Severe Anemia from Non-Falciparum Malaria Species in Southern Papua: A Hospital-Based Surveillance Study

- HIV-1 Transmission during Early Infection in Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Phylodynamic Analysis

- PLOS Medicine

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Artemisinin Combination Therapy: A Good Antimalarial, but Is the Dose Right?

- Circulating Mitochondrial DNA in Patients in the ICU as a Marker of Mortality: Derivation and Validation

- Timing and Completeness of Trial Results Posted at ClinicalTrials.gov and Published in Journals

- Malaria and Severe Anemia: Thinking beyond

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy