HIV among People Who Inject Drugs in the Middle East and North Africa: Systematic Review and Data Synthesis

Background:

It is perceived that little is known about the epidemiology of HIV infection among people who inject drugs (PWID) in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). The primary objective of this study was to assess the status of the HIV epidemic among PWID in MENA by describing HIV prevalence and incidence. Secondary objectives were to describe the risk behavior environment and the HIV epidemic potential among PWID, and to estimate the prevalence of injecting drug use in MENA.

Methods and Findings:

This was a systematic review following the PRISMA guidelines and covering 23 MENA countries. PubMed, Embase, regional and international databases, as well as country-level reports were searched up to December 16, 2013. Primary studies reporting (1) the prevalence/incidence of HIV, other sexually transmitted infections, or hepatitis C virus (HCV) among PWIDs; or (2) the prevalence of injecting or sexual risk behaviors, or HIV knowledge among PWID; or (3) the number/proportion of PWID in MENA countries, were eligible for inclusion. The quality, quantity, and geographic coverage of the data were assessed at country level. Risk of bias in predefined quality domains was described to assess the quality of available HIV prevalence measures. After multiple level screening, 192 eligible reports were included in the review. There were 197 HIV prevalence measures on a total of 58,241 PWID extracted from reports, and an additional 226 HIV prevalence measures extracted from the databases.

We estimated that there are 626,000 PWID in MENA (range: 335,000–1,635,000, prevalence of 0.24 per 100 adults). We found evidence of HIV epidemics among PWID in at least one-third of MENA countries, most of which are emerging concentrated epidemics and with HIV prevalence overall in the range of 10%–15%. Some of the epidemics have however already reached considerable levels including some of the highest HIV prevalence among PWID globally (87.1% in Tripoli, Libya). The relatively high prevalence of sharing needles/syringes (18%–28% in the last injection), the low levels of condom use (20%–54% ever condom use), the high levels of having sex with sex workers and of men having sex with men (15%–30% and 2%–10% in the last year, respectively), and of selling sex (5%–29% in the last year), indicate a high injecting and sexual risk environment. The prevalence of HCV (31%–64%) and of sexually transmitted infections suggest high levels of risk behavior indicative of the potential for more and larger HIV epidemics.

Conclusions:

Our study identified a large volume of HIV-related biological and behavioral data among PWID in the MENA region. The coverage and quality of the data varied between countries. There is robust evidence for HIV epidemics among PWID in multiple countries, most of which have emerged within the last decade and continue to grow. The lack of sufficient evidence in some MENA countries does not preclude the possibility of hidden epidemics among PWID in these settings. With the HIV epidemic among PWID in overall a relatively early phase, there is a window of opportunity for prevention that should not be missed through the provision of comprehensive programs, including scale-up of harm reduction services and expansion of surveillance systems.

Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Published in the journal:

HIV among People Who Inject Drugs in the Middle East and North Africa: Systematic Review and Data Synthesis. PLoS Med 11(6): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001663

Category:

Research Article

doi:

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001663

Summary

Background:

It is perceived that little is known about the epidemiology of HIV infection among people who inject drugs (PWID) in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). The primary objective of this study was to assess the status of the HIV epidemic among PWID in MENA by describing HIV prevalence and incidence. Secondary objectives were to describe the risk behavior environment and the HIV epidemic potential among PWID, and to estimate the prevalence of injecting drug use in MENA.

Methods and Findings:

This was a systematic review following the PRISMA guidelines and covering 23 MENA countries. PubMed, Embase, regional and international databases, as well as country-level reports were searched up to December 16, 2013. Primary studies reporting (1) the prevalence/incidence of HIV, other sexually transmitted infections, or hepatitis C virus (HCV) among PWIDs; or (2) the prevalence of injecting or sexual risk behaviors, or HIV knowledge among PWID; or (3) the number/proportion of PWID in MENA countries, were eligible for inclusion. The quality, quantity, and geographic coverage of the data were assessed at country level. Risk of bias in predefined quality domains was described to assess the quality of available HIV prevalence measures. After multiple level screening, 192 eligible reports were included in the review. There were 197 HIV prevalence measures on a total of 58,241 PWID extracted from reports, and an additional 226 HIV prevalence measures extracted from the databases.

We estimated that there are 626,000 PWID in MENA (range: 335,000–1,635,000, prevalence of 0.24 per 100 adults). We found evidence of HIV epidemics among PWID in at least one-third of MENA countries, most of which are emerging concentrated epidemics and with HIV prevalence overall in the range of 10%–15%. Some of the epidemics have however already reached considerable levels including some of the highest HIV prevalence among PWID globally (87.1% in Tripoli, Libya). The relatively high prevalence of sharing needles/syringes (18%–28% in the last injection), the low levels of condom use (20%–54% ever condom use), the high levels of having sex with sex workers and of men having sex with men (15%–30% and 2%–10% in the last year, respectively), and of selling sex (5%–29% in the last year), indicate a high injecting and sexual risk environment. The prevalence of HCV (31%–64%) and of sexually transmitted infections suggest high levels of risk behavior indicative of the potential for more and larger HIV epidemics.

Conclusions:

Our study identified a large volume of HIV-related biological and behavioral data among PWID in the MENA region. The coverage and quality of the data varied between countries. There is robust evidence for HIV epidemics among PWID in multiple countries, most of which have emerged within the last decade and continue to grow. The lack of sufficient evidence in some MENA countries does not preclude the possibility of hidden epidemics among PWID in these settings. With the HIV epidemic among PWID in overall a relatively early phase, there is a window of opportunity for prevention that should not be missed through the provision of comprehensive programs, including scale-up of harm reduction services and expansion of surveillance systems.

Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Introduction

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has been singled out as the region with little data and where the status of the HIV/AIDS epidemic remained unknown [1]–[8]. In 2005, the region was characterized as “a real hole in terms of HIV/AIDS epidemiological data” [9]. The MENA region has, however, witnessed a remarkable growth in HIV research over the last decade, with several countries developing surveillance systems to monitor the spread of HIV infection, including among most-at-risk populations [10].

A large fraction of studies conducted in the region has remained unpublished in the scientific literature, and only available in the form of difficult to access country reports. This has meant that data have not been analyzed or synthesized at either country or regional level, and no critical assessment of the quality of available evidence has been conducted. The rationale for this study came from signs of a growing HIV disease burden in the MENA region, which highlighted the urgent need for a critical and comprehensive evaluation of the status of the HIV epidemic and of the quality of evidence among the different population groups to inform HIV policy and programming in the region; this was the mandate of the MENA HIV/AIDS Synthesis Project, the largest HIV study in MENA to date [11].

The present article follows on from a series of studies conducted as part of the Synthesis Project. These studies include a high-level overview of HIV epidemiology in MENA [12], a systematic review of HIV molecular evidence [13], and the first documentation of the emerging HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men (MSM) in MENA [14]. The present study is, to our knowledge, the first systematic review and data synthesis to characterize the status of the HIV epidemic among people who inject drugs (PWID) in MENA. The presented regional analysis takes on an additional importance with the need to capture the volume of bio-behavioral surveillance data that became available within the last few years in MENA, and is yet to be analyzed and synthesized within a country-specific or a regional context [15].

PWID are one of the key populations at high risk of HIV in MENA, a region with several vulnerability factors for injecting drug use. For example, 83% of the global supply of heroin is produced in Afghanistan [16], and over 75% of this is trafficked through Iran and Pakistan. In 2009, Iran bore the highest fraction of the global opium and heroin seizures (89% and 33%, respectively) [16]. Increased availability and purity of heroin at lower prices in MENA appears to have led to a subsequent rise in injecting drug use [17]. In 2010, one gram of heroin in Afghanistan could be purchased for about US$4 compared with up to US$100 in West and Central Europe, US$200 in the United States and Northern Europe, and US$370 in Australia [16]. Most PWID in the region are young adults and marginalized by family members and society; they are stigmatized and lack access to comprehensive and confidential HIV prevention and treatment services [11].

The primary objective of this study was to assess the status of the HIV epidemic among PWID in MENA by describing HIV prevalence and incidence. The secondary objective was to describe the risk behavior environment and the HIV epidemic potential among PWID by describing (1) their injecting and sexual risk behavior and knowledge, and (2) prevalence of proxy biological markers of these behaviors, namely hepatitis C virus (HCV) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), respectively. The study also estimated the proportion and number of PWID in MENA.

Methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Text S1) [18],[19] and Cochrane Collaboration guidelines [20].

Data Sources and Search Strategy

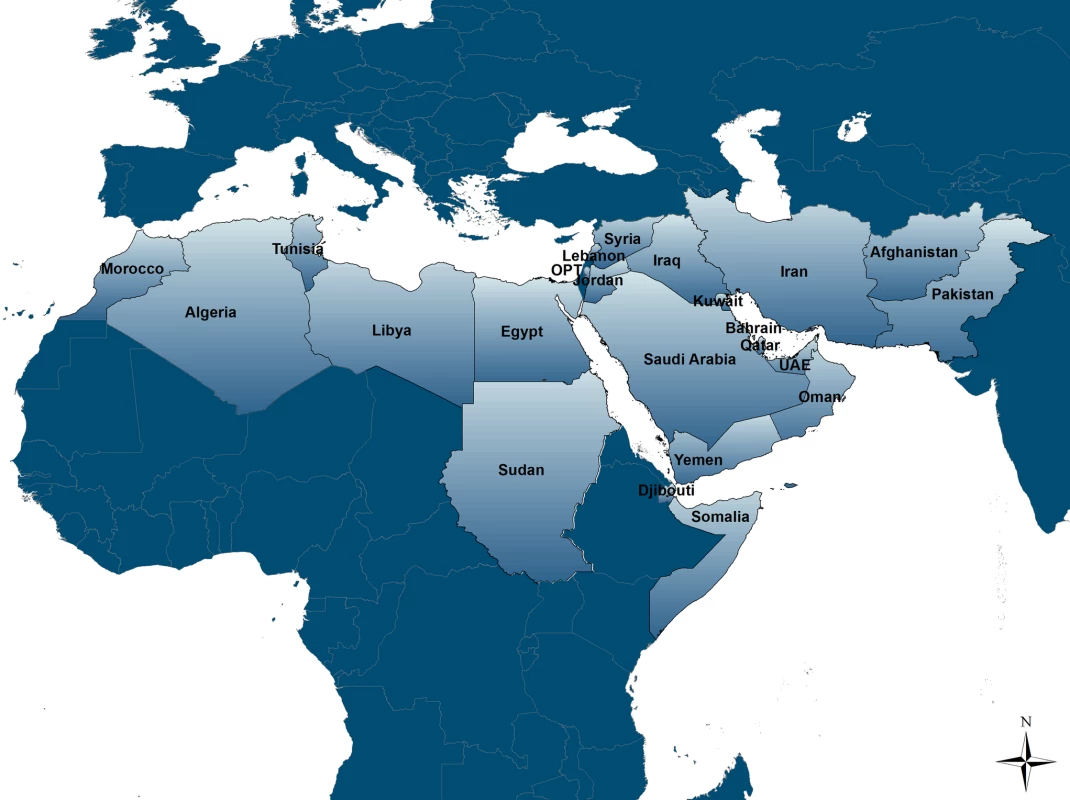

Our review covered the 23 countries included in the MENA definitions of the three international organizations leading the regional HIV response efforts in the region: the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office of the World Health Organization (WHO/EMRO), and the World Bank (Figure 1). These countries share specific similarities, whether historical, socio-cultural, or linguistic; and are conventionally included together as part of HIV/AIDS programming for the region.

The following sources of data were searched up to December 16, 2013: (1) Scientific databases (PubMed, Embase, and regional databases [WHO African Index Medicus [21] and WHO Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region [22]]), with no publication date or language restrictions. A generic search of “drug use” in MENA was performed in PubMed and Embase using MeSH/Emtree and text terms. The term “HIV” was not included to avoid detection bias. (2) The MENA HIV/AIDS Synthesis Project database of grey and mainly unpublished literature [11],[12]. (3) Abstracts of the International AIDS Conference 2002–2012 [23], the International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment 2001–2013 [24], and the International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research Conferences 2003–2013 [25]. (4) International and regional databases of HIV prevalence measures including the US Census Bureau database of HIV/AIDS [26], the WHO/EMRO HIV testing database [27], and the UNAIDS epidemiological fact sheets database [28].

Details of the search criteria are provided in Text S2. Reference lists of all relevant papers and review articles were also searched.

Study Selection

Titles and abstracts of all records identified were screened independently by two authors (GRM and SR), and consensus on potential eligibility reached. Full texts of potentially relevant records were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Studies satisfying any of the below criteria were eligible: (1) The proportion of PWID in the sample was specified, at least half were PWID, and data on any of the following outcomes were included: Prevalence or incidence of HIV; prevalence of injecting or sexual risk behaviors, or knowledge; prevalence or incidence of HCV; and prevalence or incidence of other STIs. HCV is transmitted primarily through percutaneous exposures and can be used as a proxy of the risk of parenteral exposure to HIV. Among PWID, a threshold HCV prevalence of about 30% implies sufficient risk behavior to sustain HIV transmission [29],[30]. Similarly, the prevalence of STIs is a useful marker of sexual risk behavior and potential for HIV sexual acquisition. (2) Data on population-based prevalence of injecting drug use or PWID population size estimates were reported.

Only studies with primary data were included. The only exception was in relation to national estimates of the number and proportion of PWID in a number of MENA countries where the only available source of data was from two global reviews [4],[31] that published data compiled through the Reference Group to the UN on HIV and Injecting Drug Use [32].

We used the term report to refer to the documents (papers, conference abstracts, or public health reports) presenting findings of a study [20]. Reports could contribute to more than one outcome. Findings duplicated in more than one report were included only once (using the more detailed report). Outcomes in more than one population/setting within a report were included separately.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted by one of the authors (GRM) using a pre-piloted data extraction form and entered into a computerized database. Double extraction on about 45% of records was confirmed by another author (LA-R). The few discrepancies were settled by consensus or by contacting authors. Data from articles in English, French, and Arabic were extracted from the full -texts. Data from records in Farsi (n = 6) were extracted from the English abstract. There were no records in other languages.

As supporting information, we also analyzed data extracted from countries' reporting on the HIV epidemic to WHO/EMRO in the format of aggregate HIV case notifications.

Scope and Quality of the Evidence

We appraised the status of the evidence on our main outcome, HIV prevalence, at country level by examining the following criteria that take into consideration the quantity, quality, and geographical coverage of available data: (1) the number of HIV prevalence measures and the total sample size they cover, (2) the number of geographic settings with HIV prevalence measures, (3) the number of multi-city studies and the maximum number of cities per study, (4) the number of rounds of integrated bio-behavioral surveillance surveys (IBBSS), and (5) the quality and precision of individual HIV prevalence measures.

The quality of individual HIV prevalence measures was assessed by describing the risk of bias (ROB). Since the number of prevalence measures among female PWID was very small and often based on small sub-samples, the quality appraisal was restricted to HIV prevalence among predominantly male PWID. Based on the Cochrane approach for assessing ROB [20], we classified each HIV prevalence measure as having a low, high, or unclear ROB for three quality domains: the sampling methodology, the type of HIV ascertainment, and the response rate. Low ROB was considered if (1) sampling was probability-based or preceded by ethnographic mapping, (2) HIV was ascertained with a biological assay, and (3) the response rate was over 80%; or over 80% of the target sample size was reached. HIV prevalence measures extracted from international and regional databases were considered of unknown quality since original reports were not available for assessing their ROB.

A minimum sample size of 100 was considered to produce estimates with good precision. For a median HIV prevalence among PWID in MENA of 8% (see Results), this implies a 95% CI of 4%–15%.

The quality of the evidence in each country was assessed by combining the above factors as described in Text S3. For example, quality was considered better if at least one round of IBBSS was conducted, since these surveys use standard methodology including state of the art sampling techniques of hard-to-reach populations (such as respondent-driven sampling). Countries were categorized as having: (1) No evidence: virtually no data. (2) Poor evidence: The majority of HIV biological measures were of poor quality. (3) Limited evidence: The number of HIV biological measures was small, but of reasonable quality. (4) Good evidence: The number of HIV biological measures was small, but with good quality and informative data. However, the overall volume of data was not sufficient to be conclusive of the status and scale of the epidemic at the national level. (5) Conclusive evidence: There was a sufficient volume of robust evidence to support the conclusion.

Analysis

The low-bound, middle, and high-bound national estimates of the number and prevalence of injecting drug use in MENA countries were extracted from reports. The pooled number and prevalence of PWID for the MENA region were estimated separately using the extracted country-level estimates. The lower (and upper) bound of our pooled regional estimate of the number of PWID in MENA was calculated by adding the lowest (and highest) reported number of PWID in all MENA countries. The middle figure for the number of PWID in MENA is the sum of the middle estimates in each of the MENA countries. When more than one such estimate was available per country, we used the median of the estimates. The pooled numbers of PWID were rounded up to the next thousand.

Middle estimates of the extracted prevalence of PWID were weighted by adult population size to derive the pooled prevalence of injecting drug use in MENA. When more than one such estimate was available per country, we used the median of the estimates. Adult population size was extracted from the United Nations World Population Database [33]. Sub-national estimates of the number and prevalence of injecting drug use were extracted from reports and described separately.

We calculated 95% CI for HIV and HCV prevalence for all reports with available information. The HIV biological data (HIV prevalence from reports and from databases, HIV incidence, and notified HIV cases) were synthesized at country level to assess the status of the HIV epidemic among PWID. Recent WHO/UNAIDS guidelines for classifying HIV epidemics [34],[35], which do not recommend use of rigid thresholds [34],[36], were adapted to classify the HIV epidemic level in PWID as: (1) Low-level HIV epidemic: HIV has not reached significant levels among PWID. (2) Concentrated HIV epidemic: HIV has reached significant levels and taken root among PWID through transmission chains between members of this population. Concentrated epidemics can be either emerging (HIV has started its initial growth and continues in a trend of increasing HIV prevalence); or established (the epidemic has reached its peak and HIV prevalence is stabilizing towards, or already is at, its endemic level). (3) “At least outbreak-type”: Insufficient evidence to support a concentrated epidemic among PWID, but some evidence, usually of lower quality, suggesting that significant HIV transmission has occurred, or is occurring, among at least some PWID groups.

The terms “national” or “at least localized” were assigned to concentrated epidemics to reflect the geographical spread of the epidemic within a given country.

Results

Results of Search Strategy

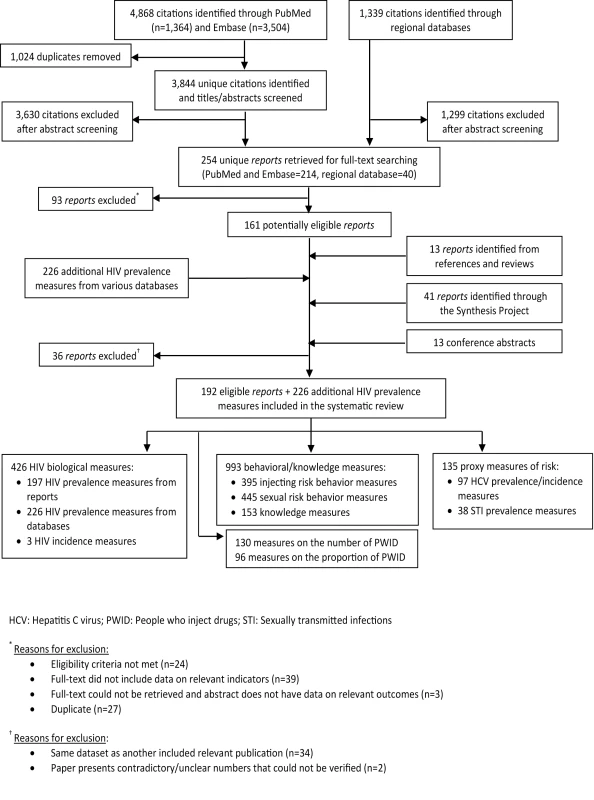

The study selection process is shown in Figure 2. A total of 6,207 citations were retrieved from PubMed, Embase, and the regional databases. After full-text screening and including reports from the other sources, 192 reports were eligible: 121 from PubMed and Embase, 41 from the MENA HIV/AIDS Synthesis Project, 13 from bibliographies of relevant reports and review articles, 13 from the search of scientific conferences, and four from the regional databases. In addition, 226 HIV point-prevalence measures were extracted from the databases of biological markers (Figure 2).

There were 423 HIV prevalence measures, 197 of which were extracted from the eligible reports and 226 from the databases of HIV prevalence; three HIV incidence measures; 93 HCV prevalence measures; four HCV incidence measures; 38 STI prevalence measures; and 993 behavioral and knowledge measures. There were also 130 and 96 measures on the number and proportion of PWID, respectively (Figure 2).

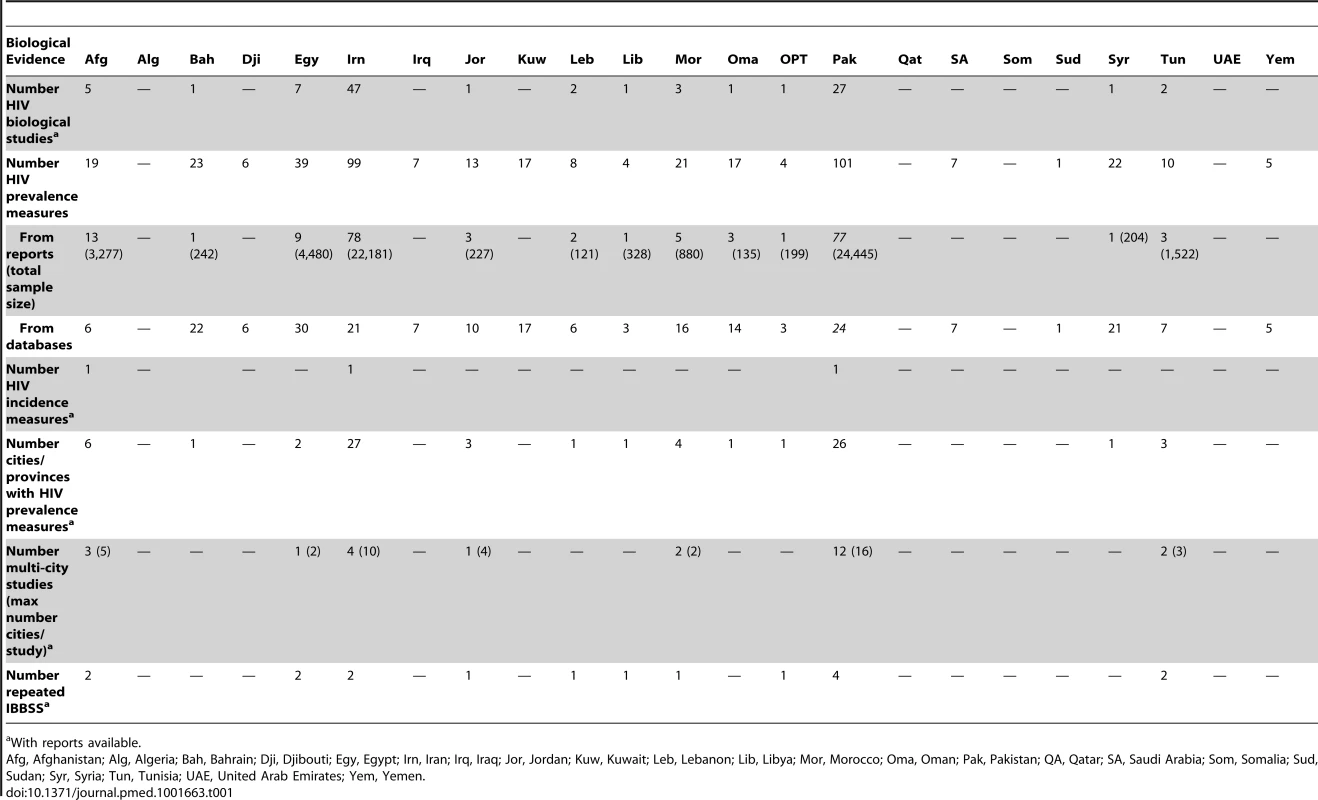

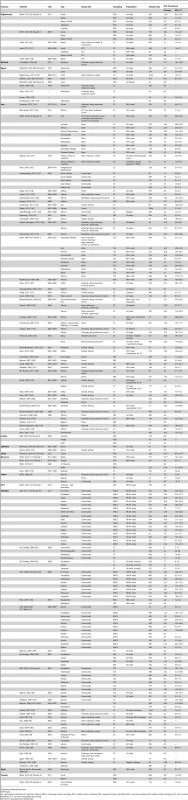

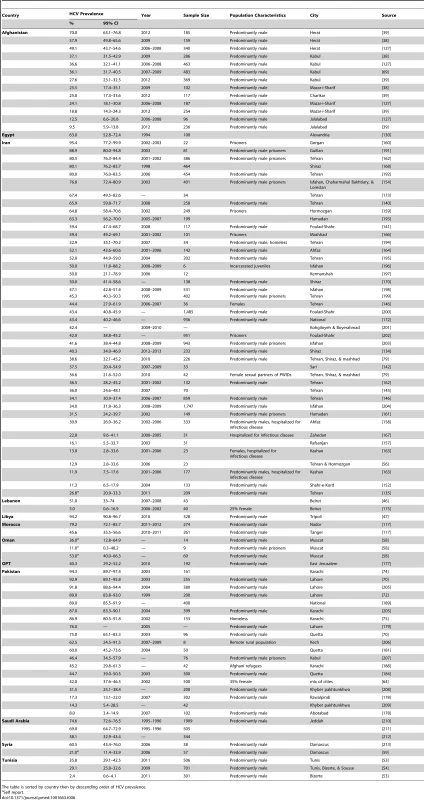

Scope and Quality of the Evidence

The number and quality of HIV prevalence measures varied by country. The largest volume of data was from Pakistan (101 HIV prevalence measures on a total of 24,445 PWID), Iran (99 HIV prevalence measures on a total of 22,181 PWID), and Egypt (39 HIV prevalence measures on a total of 4,480 PWID) (Table 1). A smaller number of HIV prevalence measures but covering a relatively large number of PWID were conducted in Afghanistan (3,277 PWID), Tunisia (1,522 PWID), and Morocco (880 PWID). Multi-city studies have been conducted in several countries including Pakistan, where up to 16 cities were included in one study [37]. IBBSS have been conducted in Afghanistan [38],[39], Egypt [40]–[42], Iran [43],[44], Jordan [45], Lebanon [46], Libya [47], Morocco [48], Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT) [49], Pakistan [37],[50]–[52], and Tunisia (Table 1) [53],[54]. Pakistan has the most repeated rounds of IBBSS with four rounds conducted between 2005 and 2011 [37],[50]–[52].

Of 190 HIV prevalence measures extracted from eligible reports and among predominantly male PWID, 98%, 53%, and 34% had low ROB in terms of HIV ascertainment, sampling methodology, and response rate, respectively. Over 60% of the 190 HIV prevalence measures had low ROB in at least two quality domains and 84% had good precision (Tables S1 and S2).

On the basis of the quality of the evidence assessment, the evidence was determined to be “conclusive” in Iran and Pakistan; “good” in Afghanistan, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, OPT, and Tunisia; “limited” in Bahrain and Syria; and “poor” in Djibouti, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Yemen. There was “no evidence” in Algeria, Qatar, Somalia, and the United Arab Emirates. A narrative justification for the classification of the scope and quality of evidence is in Text S3.

Although a formal quality assessment was not made for the secondary outcomes in terms of injecting and sexual risk behavior and knowledge, the majority of these data were extracted from the IBBSS studies using standard survey methodology and large samples. Details of these studies (with information on sample size, population characteristics, and/or sampling technique) can be found in the tables summarizing the prevalence of HIV and HCV among PWID (Tables 3 and 6).

Prevalence of Injecting Drug Use

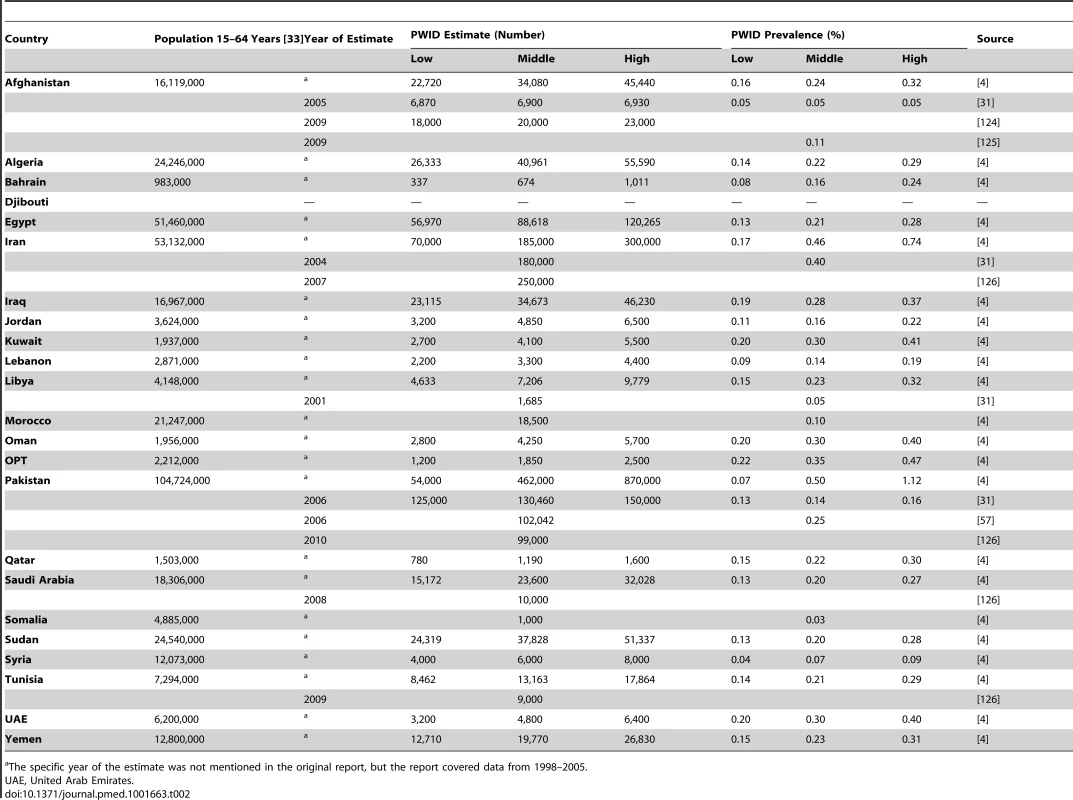

Table 2 describes national estimates of the number and prevalence of PWID. These national estimates were extracted from included reports where they were derived using different methodologies including indirect methods (such as capture-recapture and multiplier methods), population-based surveys, registered number of PWID, and rapid assessments. In two of the sources of data in Table 2 [4],[31], some of the country estimates are the collation of several such country-specific estimates using methods described in the original reports [4],[31].

Based on available data, the number of PWID in MENA ranges between a low bound of 335,000 and a high bound of 1,635,000, with a middle estimate of 626,000 PWID. Iran, Pakistan, and Egypt have the largest number, with a median of about 185,000, 117,000, and 89,000 PWID, respectively. The weighted mean prevalence of injecting drug use in MENA is 0.24 per 100 adults. It is lowest in Somalia (0.03%) and highest in Iran (0.43%) (Table 2).

Studies of sub-national populations showed geographical heterogeneity (Table S3). For example, in Iran, the prevalence of injecting drug use varied between 0.0% in rural Babol province [55] to 1.0% in Tehran [56]; and in Pakistan it ranged from 0.02% in Rawalpindi to 0.87% and 1.07% in Sargodha and Faisalabad, respectively [57].

Data on the prevalence of female PWID in MENA were scarce. Overall, the mean proportion of females among PWID in included studies was 2.3% (range: 0%–35%). In two studies in Oman and Syria, 25%–58% [58] and 48% [59] of PWID, respectively, reported knowing at least one female PWID.

HIV Prevalence, Incidence, and Mode of Transmission

HIV prevalence measures from reports and databases are summarized in Tables 3 and S4, respectively. Considerable variation in HIV prevalence was seen, with an overall median of 8% (interquartile range [IQR]: 1%–21%) (Table 3). HIV prevalence among PWID in MENA ranged between 0% in some prevalence measures in almost every country up to 7% in Cairo, Egypt in 2010 (n = 274) [42]; 18% in Afghanistan in one city near the Iranian borders, Herat, in 2009 (n = 159) [38]; 21% in Manama, Bahrain, in the early nineties (n = 242) [60]; 27% in Oman among incarcerated PWID (n = 33) [58]; 38% in Nador, northern Morocco, in 2008 (n = 233) [61]; 52% in the third largest metropolis in Pakistan, Faisalabad, in 2011 (n = 364) [37]; 72% in rural Iran in 2004–5 (n = 61) [62]; and 87% in Tripoli, Libya in 2010 (n = 328) [47] (Table 3). HIV prevalence was consistently low among PWID in Jordan, Lebanon, OPT, Syria, and Tunisia (0%–3.1%). Substantial intra-country variability in HIV prevalence was observed in Afghanistan, Iran, Morocco, and Pakistan (Table 3). In most countries with high HIV prevalence, recent studies report increasing HIV prevalence starting around 2003 (Tables 3 and S4).

Three HIV incidence studies were identified. In Kabul, Afghanistan, HIV incidence among a sample of 479 PWID in 2008 was 2.2/100 person-years (pyr), despite 72% of study participants reporting use of harm reduction services [63]. Among 500 PWID in three cities in Pakistan, HIV incidence was 1.7/100 pyr in 2006 [64]. A very high incidence rate (17.2/100 pyr) was reported in Tehran, Iran, in 2002 among 214 incarcerated PWID [65].

Analysis of notified HIV cases indicated that in 2011, injecting drug use contributed 20% (80/409), 23% (50/216), 38% (6/16), 49% (52/107), and 60% (948/1,588) of all newly notified cases in this year in Egypt, Pakistan, Bahrain, Afghanistan, and Iran, respectively. A smaller contribution was reported in the remaining countries (Table 4).

![Contribution of injecting drug use as a mode of HIV transmission to the total HIV/AIDS cases by country as per various studies/reports and countries' case notification reports <em class="ref">[126]</em>,<em class="ref">[190]</em>.](https://www.prelekara.sk/media/cache/resolve/media_object_image_small/media/image/33829d27fab8f5f4c7997a3e7925e754.png)

HIV Epidemic States

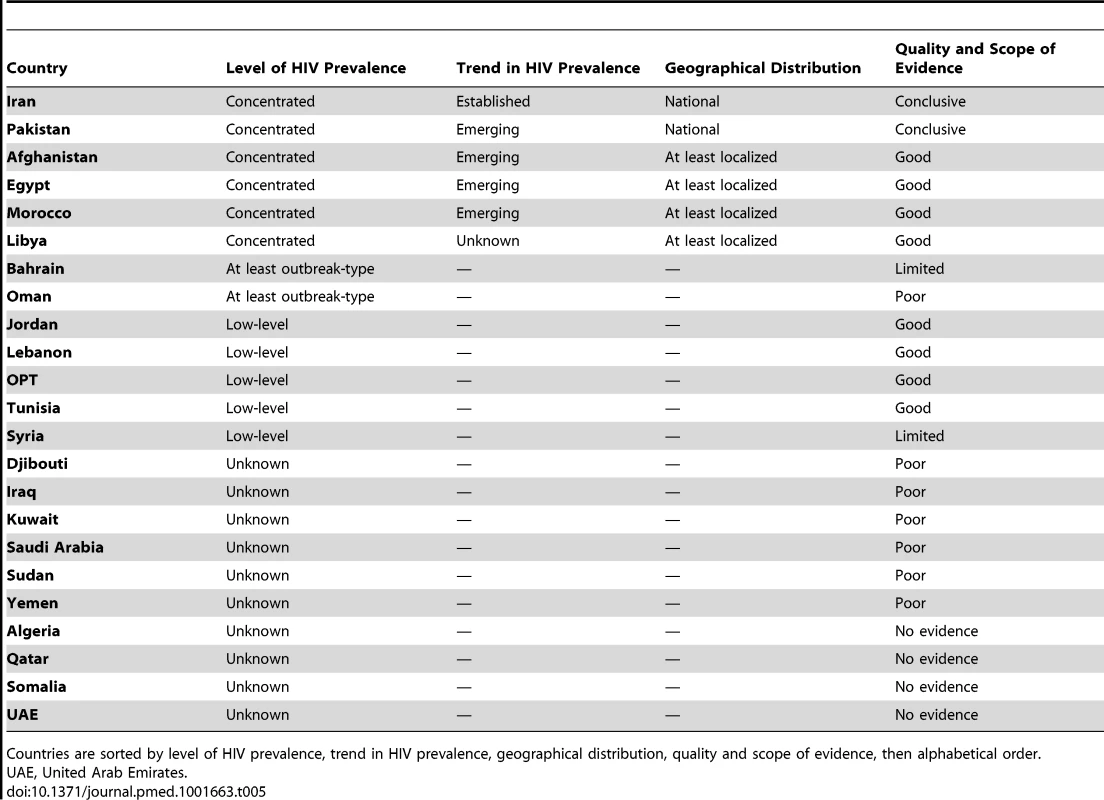

The evidence was sufficient to characterize the HIV epidemic state in 13 countries, summarized in Table 5. Details on how the conclusions were reached are in Text S3.

Concentrated HIV epidemics

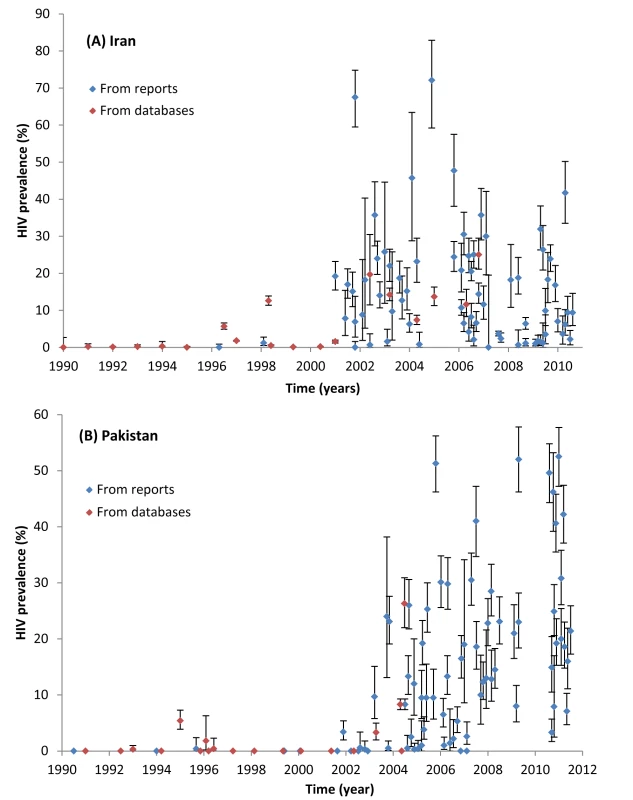

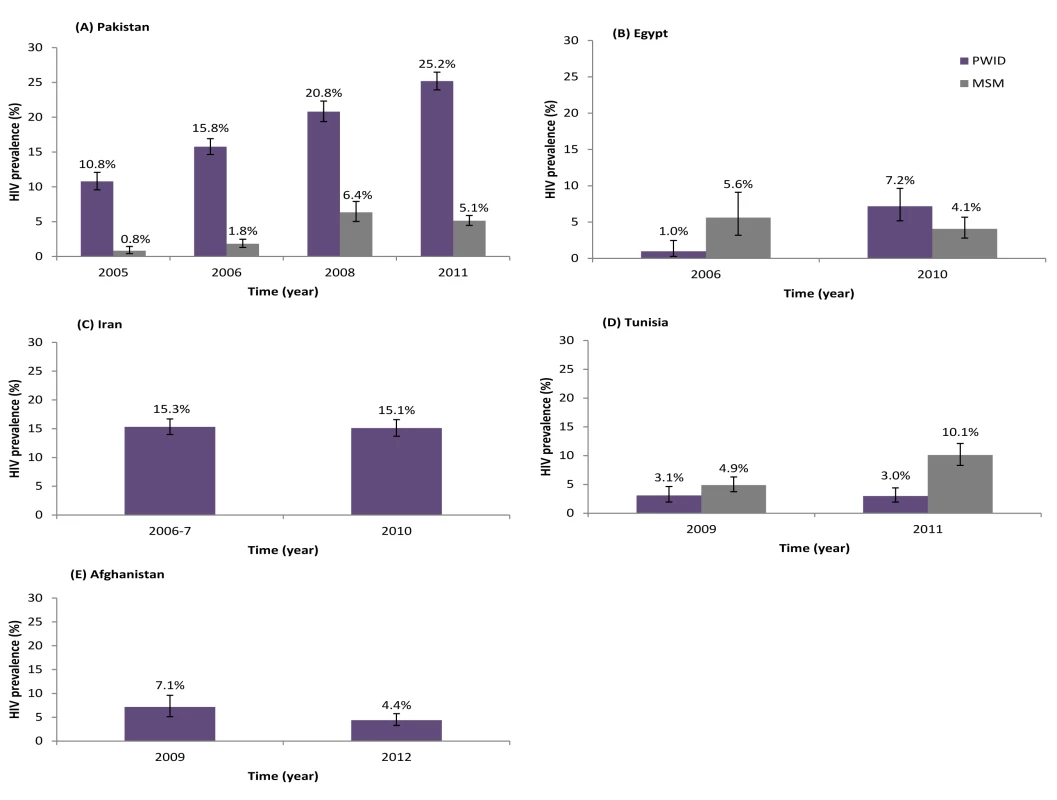

Concentrated HIV epidemics among PWID were observed in Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Egypt, Morocco, and Libya (Table 5). Iran is the only country with conclusive evidence for an established concentrated epidemic at the national level. The first HIV outbreaks among PWID in Iran were reported around 1996. HIV prevalence then increased considerably in the early 2000s, reaching a peak by the mid-2000s (Figure 3A). HIV prevalence in the 2006 and 2010 multi-city IBBSS was stable at 15% (n = 2,853 and n = 2,479, respectively) (Figure 4C) [43],[44]. The evidence suggests that the HIV epidemic among PWID in Iran is now established at concentrated levels of about 15%.

Emerging concentrated epidemics were seen in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Egypt, and Morocco (Table 5). For example, in Pakistan, after almost two decades of very low HIV prevalence among PWID, a trend of increasing prevalence was observed after 2003 (Figure 3B). This trend is national and ongoing, reaching over 40% in recent studies and with no evidence yet of stabilization (Figure 3B). This trend also manifests itself in the multi-province IBBSS where HIV prevalence among PWID has steadily increased from 10.8% in 2005 (n = 2,431) [52], to 15.8% in 2006 (n = 4,039) [51], 20.8% in 2008 (n = 2,969) [50], and 25.2% in 2011 (n = 4,593) [37] (Figure 4A). In view of the high HIV prevalence, the emerging HIV epidemic in Pakistan is considered advanced. Another example is Egypt where HIV prevalence was also very low for about two decades (Tables 3 and S4), including the first round of IBBSS in 2006 [40],[41], but increased to 6%–7% in both cities surveyed in the most recent IBBSS in 2010 (n = 284 and n = 274) (Figure 4B) [42]. Consistently, 19.6% of the 409 newly notified HIV cases in 2010 in Egypt were due to injecting drug use, compared with only 1.6% of the total notified cases up to 2008 (Table 4). In Afghanistan (Figure 4E) and Morocco, the HIV epidemic among PWID appears to be emerging in at least parts of the country, with notably high HIV prevalence in some settings, but still low HIV prevalence in others (Table 3).

The HIV epidemic in Libya is also concentrated, but the trend is unclear. Libya has the highest reported prevalence of HIV among PWID in MENA (87.2%, 95% CI 83.1%–90.6% in the IBBSS in Tripoli [47]). Earlier data, although of unclear quality, also indicate prevalence of up to 59% in 2001 among PWID in Tripoli (Table S4). This indicates a concentrated HIV epidemic among PWID in at least part of Libya. Although the epidemic in Tripoli is most likely to be established, the level of evidence overall is insufficient to characterize whether the national epidemic is emerging, with few outbreaks in the past, or is established with endemic HIV transmission among PWID.

“At least outbreak-type” HIV epidemics

In Bahrain and Oman, data show that there are, or have been, at least some pockets of HIV infection among PWID, with reported prevalence up to 21.1% (Bahrain, n = 242) [60] and 27% (Oman, n = 33) [58]. However, most available data are from studies with unknown methodology or high ROB; therefore, the quality of evidence is insufficient to indicate whether there is a concentrated epidemic in these two countries, even if localized.

Low-level HIV epidemics

The HIV epidemic among PWID is low-level in Jordan, Lebanon, Tunisia, OPT, and Syria (Table 5). In these countries (except Syria), at least one round of IBBSS has been conducted, in addition to other data; all indicate limited HIV spread among PWID (Figure 4D; Tables 3 and S4). The contribution of injecting drug use to the total notified cases also remains minimal in these countries, further confirming a low-level epidemic (Table 4).

Injecting Risk Behavior

Table S5 summarizes injecting risk behavior measures among PWID in MENA. The key risk behavior that exposes PWID to HIV infection is the use of non-sterile injecting equipment. Available data indicate that the lifetime prevalence of sharing needles/syringes among PWID in MENA was as high as 71% [45], 79% [66], 85% [47], 95% [67], and 97% [58] in Jordan, Pakistan, Libya, Iran, and Oman, respectively. The median prevalence of sharing in the last injection was 23% (IQR: 18%–28%). In Pakistan, most injecting occurs in groups and in public places, and reported use of “street doctors” or professional injectors was common, which is associated with high reuse of injecting equipment (Table S5) [50].

In MENA, PWID inject drugs at median of 2.2 injections per day, with reported rates of 3.3 [68] and 5.7 [69] injections per day among some PWID in Iran and Afghanistan, respectively. The median age at first injection was 26 years (IQR: 24–28 years), and the median duration of injecting drugs was 4.6 years (IQR: 3.8–6.1 years) (Table S5).

Sexual Risk Behavior

The majority of PWID in MENA are sexually active (Table S6). On average, 52% have been ever married (IQR: 35%–56%), 43%–89% report having sex with a regular female partner, 29%–60% reported multiple sexual partnerships, and 18%–42% report sex with non-regular female partners in the last year (Table S6). Reported levels of condom use varied but generally were on the low to intermediate range. Overall, 36% of PWID reported ever using condoms (IQR: 20%–54%) with the lowest prevalence in Afghanistan and Pakistan (10%–38% [70]–[76]), and the highest in Lebanon (88% [77]). Condom use during last sex was reported by 4%–38% of PWID, reaching 66% only in Libya [47]. Only 12%–25% of PWID reported consistent condom use in the last year (Table S6).

Mixing with Other High-Risk Populations

Risk behaviors of PWID in MENA overlap considerably with other high-risk populations, namely MSM and female sex workers. A median of 18% of male PWID in MENA reported ever having sex with men (IQR: 11%–27%), and a median of 7% did so in the last year (IQR: 2%–10%) (Table S6). The highest rates of same-sex sex have been reported in Pakistan. Reported condom use during anal sex was overall very low (Table S6).

PWID in MENA engage in sex work, either through buying or selling sex. A median of 45% reported ever having sex with a sex worker (IQR: 31%–64%), and a median of 23% did so in the last year (IQR: 15%–30%), with generally low levels of condom use (Table S6). Selling sex in the past year was reported by 5%–29% of PWID in Egypt, Iran, Morocco, OPT, and Pakistan (Table S6).

Proxy Biological Markers of Risk Behavior

There was substantial between-and within-country variation in HCV prevalence among PWID, with a median of 44% (IQR: 31%–64%) (Table 6). Very high HCV prevalence was reported such as in Afghanistan (70%, n = 185, Herat), Egypt (63%, n = 100, Alexandria), Iran (over 80%, n = 386 prisoners, Tehran), Libya (94%, n = 328, Tripoli), Pakistan (94%, n = 161, Karachi), and Saudi Arabia (75%, n = 1,909, Jeddah) (Table 6). These figures are consistent with the reported high levels of sharing of injection equipment, such as in Iran, Pakistan, and Libya (Table S5).

Available data on the prevalence of syphilis among PWID in Egypt, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan indicate relatively high prevalence up to 3%, 8%, 17%, and 18%, respectively (Table S6). Considerable herpes simplex virus type 2 prevalence has been reported among PWID in Afghanistan (4%–21%) and Pakistan (6%–19%) (Table S6). Data on the prevalence of gonorrhoea (0%–1.8%) and chlamydia (0%–0.7%) were available only in Pakistan (Table S6).

Knowledge of HIV/AIDS

Levels of basic HIV/AIDS knowledge among PWID in MENA were high overall, with a median of 93% having ever heard of HIV/AIDS (IQR: 72%–99%). Still, there was much variation in the proportion of PWID who correctly identified reuse of non-sterile needles/syringes and unprotected sex as modes of HIV transmission (Table S7). Only a median of 45% (IQR: 30%–63%) of PWID perceived themselves at risk of HIV/AIDS (Table S7). With a few exceptions of high levels of HIV testing such as in Lebanon and Oman, the median prevalence of lifetime testing among PWID ranged between 8% (Egypt) and 45% (Iran) (Table S7).

Discussion

Injecting Drug Use in MENA

We estimate that there are 626,000 PWID in the MENA region. Overall, the mean prevalence of injecting drug use (0.24%) is comparable with global figures which range from 0.06% in South Asia to 1.50% in Eastern Europe [31]. Prevalence of injecting drug use in MENA varied between countries and was higher in the eastern part of the region. Injecting drug use appears to be heavily concentrated among men; but female PWID are one of the hardest-to-reach populations in MENA, thereby limiting our knowledge of this vulnerable group. From limited available data, it appears that injecting drug use among females has a strong association with sex work and having a PWID sexual partner [78],[79].

Emerging HIV Epidemics and HIV Epidemic Potential among PWID

After synthesizing a large body of data, we documented HIV epidemics among PWID in one-third of MENA countries. The HIV epidemic is in a concentrated state in about half the countries with available data. Iran is the only country with an established concentrated epidemic, while the most common pattern is that of emerging concentrated epidemics. Most observed epidemics in the region are recent, occurring only in the last decade; around the same time that HIV epidemics among MSM appear to have emerged (2003) [14]. Of note, our classification of epidemic states did not depend only on the size of the epidemic, but also on the trend of HIV prevalence and other biological data. For example in Pakistan, despite high HIV prevalence, the epidemic was classified as emerging since HIV prevalence continues in an increasing trend. HIV prevalence among PWID in MENA countries with concentrated epidemics is overall in the range of 10%–15%, which is in the intermediate range compared to global figures [31]. However, there are settings with very high prevalence, most notably in Tripoli, Libya, which appears to have one of the highest HIV prevalence reported globally (87.1%) [31],[47].

In about 20% of MENA countries, the HIV epidemic among PWID was low level, with HIV prevalence consistently low for many years including the most recent IBBSS. In some countries, such as Jordan, Lebanon, and OPT, no HIV infections were found in the IBBSS. The available evidence in countries at low level is restricted to a few cities, and there could be hidden sub-epidemics in other sites. Nevertheless, the low prevalence could be reflective of the intrinsic HIV transmission dynamics, levels of risk behavior, and/or injecting network structure. HIV may not have been introduced to the PWID community, may have been recently introduced, or may have been spreading slowly and inefficiently for some time. The latter may reflect injecting networks with infrequent and few repeated transmission contacts among PWID to sustain HIV dynamics. In Lebanon and Syria for example, it appears that PWID form closed small networks with injecting occurring in private homes and among friends, and not in large groups or at shooting galleries [59],[80]. The low prevalence could also be a consequence of stochastic effects where the small number of individuals who introduced HIV to the PWID population happened by chance not to have links that could sustain transmission chains.

Whilst it is conceivable that HIV prevalence may not grow in countries currently at low level, there are settings where HIV prevalence increased considerably in a short period of time. For example in Karachi, Pakistan, after several years of near zero prevalence [74],[75],[81],[82], HIV prevalence in 2004 increased to 23% in less than 6 months [83], and reached 42% in 2011 [37]. This pattern is not surprising given the reported risky practices and high HCV prevalence. When HIV prevalence was still very low in Karachi, HCV prevalence was over 85% [74],[75], indicating substantial use of non-sterile injecting equipment and suggesting connectivity of injecting networks. In Iran, the substantial HCV prevalence (up to 80%) was predictive of the explosive HIV epidemic that occurred subsequently. In both Iran and Pakistan, injecting networks often seem to be well connected and we found reports of injecting and sharing occurring among persons who are not necessarily socially related, e.g. in shooting galleries [84],[85]. Data on HCV prevalence among PWID in MENA countries with low-level HIV epidemics are limited. However, HCV prevalence of 40%–61% among some PWID groups such as in Lebanon, OPT, and Syria suggest moderate HIV epidemic potential once the virus is introduced to the PWID community.

Bridging of the HIV Epidemic to Other Population Groups

We found considerable overlap of risk behavior between PWID and other high-risk groups in MENA; this could play a role in emerging HIV epidemics, as it creates opportunities for an infection circulating in one population to be bridged to another one. In Pakistan, the rapidly growing HIV epidemic among PWID was followed closely by an emerging epidemic among transgender sex workers (Figure 4A). Phylogenetic analyses found clustering of subtypes between the two populations, suggesting that the infection might have bridged from PWID to the transgender population [86]. A similar pattern, but in the opposite direction, may have occurred in Egypt where an emerging epidemic among MSM [14] preceded the nascent epidemic among PWID (Figure 4B). While supported by behavioral data [40],[42], this needs to be confirmed by phylogenetic analyses.

Our analysis, focused on the HIV disease burden among PWID, still masks the role of these epidemics in driving the onward transmission of HIV to the sexual partners of PWID and further in the population. The majority of PWID are sexually active and about half are married. They often engage in risky sexual behavior as confirmed by the prevalence of STIs. This puts sexual partners of PWID at risk of HIV. A substantial number of infections in MENA have been documented in women who acquired HIV from their PWID husbands; and in some countries, the majority of HIV infections among women were acquired from a PWID sexual partner [79],[87]–[89]. This highlights the vulnerability of sexual partners of PWID, who are often female spouses. An illustration of the role of the HIV epidemics among PWID in driving the onward transmission of HIV emerges from recent mode of transmission (MoT) modeling studies in the region [90]–[92]. For example, in Iran, PWID directly contributed 56% of the total HIV Incidence; and indirectly, only through infections to their current sexual partners, an additional 12% of the total incidence [92]. More onward HIV transmissions would arise if the sexual partners of PWID transmitted the infection to their other sexual partners.

Study Limitations

One limitation of our study is that the quantity and quality of data varied by countries. There were virtually no HIV data in four countries, and the data quality in six others was insufficient to assess the status of the epidemic. Longitudinal repeated IBBSS data were available in only five countries. Six countries have recently conducted their first round of IBBSS; and in most of these, subsequent rounds are either planned or being implemented. The quality of data was “good” or “conclusive” in ten out of the 23 countries.

While most of the data were from cross sectional surveys, there was a substantial improvement in the quality of data over time. Many studies were conducted with state of the art research methodologies in HIV research. These consist of IBBSS studies using innovative sampling methodologies for hard-to-reach populations such as respondent-driven sampling and time-location sampling. Most of these studies benefited from large sample sizes and some from broad geographical coverage at the national level.

Of note that in several countries there were no recent national estimates of the number and proportion of PWID. The only national data available for these countries were extracted from earlier global reviews of injecting drug use [4],[31]. The reviews were based mainly on estimates by the Reference Group to the UN on HIV and Injecting Drug Use, which systematically collects and analyses global data on injecting drug use and HIV [32]. The Reference Group is considered the main reference for PWID estimates globally, providing the estimates to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), WHO, and UNAIDS secretariats. We complemented the Reference Group data with PWID national risk-group size estimation studies that were conducted in the last few years in five countries namely Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia. Since we partly relied on secondary sources of data and since the data that we used came from studies using different methodologies, our pooled estimates of the number and prevalence of PWID in MENA should be considered as approximate figures.

In assessing the status of the epidemic at the country-level, we did not limit our analysis to one line of evidence, but synthesized and corroborated findings from different data sources and types such as HIV prevalence and incidence, notified HIV cases, injecting and sexual risk behavior, and other related and contextual data. Thus we could make a comprehensive assessment of the epidemic status and address potential limitations in any one line of evidence [93]. We did a rigorous appraisal of the scope and quality of the evidence within each country by assessing the amount and geographical coverage of available data, as well as the ROB and precision of individual point estimates. A qualifier for the scope and quality of the evidence at the country level was integrated with each HIV epidemic state assigned. Our search criteria were expansive, covering different literature sources. Before the present submitted work, the status of the epidemic across MENA country was poorly understood. On the basis of our integrated data synthesis and using rigorous methodology and data quality assessment, we were able to concretely qualify the epidemic status in 13 countries (over half of MENA countries), and to document the overall trend of emerging epidemics. The lack of evidence in several MENA countries does not preclude the possibility of hidden epidemics among PWID in these settings.

HIV Response among PWID in MENA

Not only does the region overall lag behind in responding to the emerging HIV epidemics among PWID; in occasions misguided policy has contributed to these epidemics. Most notably in Libya, the large HIV epidemic among PWID appears to have been exacerbated by restrictions imposed on the sale of needles and syringes at pharmacies in the late 1990s [11],[94]. Overall, harm reduction programs still remain limited in MENA, and there is a need to integrate such programs within the socio-cultural framework of the region [95]. Several countries though have made significant strides in initiating such programs in recent years [11],[96]. Needle/syringe exchange programs are currently implemented in nine countries, and opioid substitution therapy in five [96]. Iran remains the leader in the provision of harm reduction services to PWID with the highest coverage of needle/syringe exchange programs in the region [12],[96]. It appears also to be the only country in MENA to provide such services in prisons [96],[97] and to provide female-operated harm reduction services targeted at female drug users [96].

Iran has also initiated triangular clinics that integrate services for treatment and prevention of injecting drug use, HIV/AIDS, and other STIs; and these clinics have received international recognition as best practice [98]–[100]. Among other interventions implemented in Iran are drop-in centers, integration of substance use treatment and HIV prevention into the rural primary health care system, and community education centers [62],[101]–[105]. These efforts appear to have been successful in reducing sharing of injecting equipment [106]–[108], though the coverage of harm reduction continues to be lower than adequate [104].

Other countries in the region have also made progress in revising their policies, adopting harm reduction programs, and integrating such programs in their national strategic plans such as Afghanistan, Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, and Tunisia [11],[109]. Access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) has also expanded in MENA in recent years, and treatment outcomes reported by country ART programs are comparable to globally reported outcomes [110],[111]. Good adherence to ART has been also observed, such as in Morocco [112], though some non-adherence and treatment interruptions, among other obstacles, have been also reported in several countries [112]–[114].

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have been instrumental to the success in harm reduction in MENA. It can be noted that in countries where NGOs are strong, HIV response has been also strong [11],[109]. The Iranian NGO Persepolis, for example, played an important role in the transformation to effective policies in Iran [115]. Building on the growing role of NGOs, a regional civil society network was established in 2007 covering 20 countries in MENA; the Middle East and North Africa Harm Reduction Association (MENAHRA) [116]. MENAHRA has the objective of building the capacity of civil society organizations in harm reduction efforts through training, sharing of information, networking and providing direct support to NGOs to initiate or scale-up harm reduction services. The network is a collaborative initiative by regional and international organizations with funding from international donors, and has been influential in promoting harm reduction.

Despite the recent progress in harm reduction, HIV prevention efforts among PWID in MENA remain impeded by generic and routine planning, competing priorities, limited human capital, and lack of monitoring and evaluation [7]. National policies remain inadequate and not sufficiently reflecting evidence-informed approaches [7]. The scope and coverage of prevention services remain patchy across and within countries [11],[96],[109]. An indicator of the low effective coverage is that only a minority of PWID report ever being tested, and a smaller proportion report being tested within the last year [11]. In Morocco and Pakistan, two countries with a strong HIV response, only 32.5% [117], 47.8% [117], 6.1% [51], and 20.7% [50] of PWID in different surveys reported ever being tested. Even where services are available, PWID may not be aware of them, and when aware of them, they may not utilize them. In Pakistan for example, 37% of PWID in one study were aware of HIV prevention programs in their city, but only 19% ever used them [52]. There is an urgent need to expand the provision, scope, and coverage of HIV interventions among PWID in MENA to be ahead of the growing HIV epidemics.

Conclusion

Our study identified a large volume of HIV-related biological and behavioral data among PWID in the MENA region, including quality data that appear in the scientific literature for the first time. The in-depth analyses, the quality assessment of evidence, and the comprehensive synthesis of data facilitated, for the first time to our knowledge, a rigorous characterization of the state of the epidemic among PWID across different countries in this region.

We found robust evidence for HIV epidemics among PWID in multiple countries, most of which have emerged only recently and continue to grow. The high risk and vulnerability context suggest potential for further HIV spread. HIV surveillance among PWID must be expanded to detect and monitor these budding and growing HIV epidemics, and to inform effective HIV policy and programming. This mainly includes conducting IBBSS studies among PWID in countries where such surveys have not been conducted yet, and implementing subsequent rounds, for the provision of longitudinal data, in countries that are already developing their surveillance base. Population size estimations and mapping and ethnographic studies are also needed for a better understanding of the profile and injecting and sexual networks of PWID in MENA.

The window of opportunity to control the emerging epidemics should not be missed. HIV prevention among PWID must be made a priority for HIV/AIDS strategies in MENA; and obstacles must be addressed for the provision of comprehensive services and enabling environments for PWID [118]. There is need to review current HIV programs among PWID in light of the emerging epidemics, and to develop service delivery models with embedded links between community-based prevention (needle/syringe exchange programs and condom provision), HIV testing, and treatment (opioid substitution and ART). Such comprehensive approach has already proven its utility in preventing HIV transmission among PWID [119]–[121], but would require better resource allocation and sufficient services in priority areas for PWID.

Prevention efforts need to prioritize those most likely to be reluctant to approach facility-based services, and those with multiple and overlapping risks. Outreach and peer education can provide a means to reach those most at risk with information and services. Access to ART should be expanded in such a region with one of the lowest ART coverage globally [122]. Such expansion must address the low diagnosis rate among people living with HIV [110]. Reaching the at-risk populations even in discreet unpublicized ways would contribute positively to HIV prevention [14],[123]. Improving HIV programming among PWID in MENA is essential not only to confront the growing HIV problem in this population group, but also to prevent the onward transmission of HIV, and the bridging of the infection to other groups as has already occurred in parts of the region.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. ObermeyerCM (2006) HIV in the Middle East. BMJ 333: 851–854.

2. UNAIDS (2010) Global Report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. Available: http://www.unaids.org/documents/20101123_GlobalReport_em.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2014.

3. AceijasC, StimsonGV, HickmanM, RhodesT (2004) Global overview of injecting drug use and HIV infection among injecting drug users. AIDS 18: 2295–2303.

4. AceijasC, FriedmanSR, CooperHL, WiessingL, StimsonGV, et al. (2006) Estimates of injecting drug users at the national and local level in developing and transitional countries, and gender and age distribution. Sex Transm Infect 82(Suppl 3): iii10–iii17.

5. LopezAD, MathersCD, EzzatiM, JamisonDT, MurrayCJ (2006) Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 367: 1747–1757.

6. van GriensvenF, de Lind van WijngaardenJW, BaralS, GrulichA (2009) The global epidemic of HIV infection among men who have sex with men. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 4: 300–307.

7. KilmarxPH (2009) Global epidemiology of HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 4: 240–246.

8. AlkaiyatA, WeissMG (2013) HIV in the Middle East and North Africa: priority, culture, and control. Int J Public Health 58: 927–937.

9. BohannonJ (2005) Science in Libya. From pariah to science powerhouse? Science 308: 182–184.

10. SabaHF, KouyoumjianSP, MumtazGR, Abu-RaddadLJ (2013) Characterising the progress in HIV/AIDS research in the Middle East and North Africa. Sex Transm Infect 89(Suppl 3): iii5–iii9.

11. Abu-Raddad L, Akala FA, Semini I, Riedner G, Wilson D, et al.. (2010) Characterizing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa: time for Strategic Action. Middle East and North Africa HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Synthesis Project. World Bank/UNAIDS/WHO Publication. Available: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2010/06/04/000333038_20100604011533/Rendered/PDF/548890PUB0EPI11C10Dislosed061312010.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2014. Washington (D.C.): The World Bank Press.

12. Abu-RaddadLJ, HilmiN, MumtazG, BenkiraneM, AkalaFA, et al. (2010) Epidemiology of HIV infection in the Middle East and North Africa. AIDS 24(Suppl 2): S5–23.

13. MumtazG, HilmiN, AkalaFA, SeminiI, RiednerG, et al. (2011) HIV-1 molecular epidemiology evidence and transmission patterns in the Middle East and North Africa. Sex Transm Infect 87: 101–106.

14. MumtazG, HilmiN, McFarlandW, KaplanRL, AkalaFA, et al. (2011) Are HIV epidemics among men who have sex with men emerging in the Middle East and North Africa?: a systematic review and data synthesis. PLoS Med 8: e1000444.

15. MumtazGR, RiednerG, Abu-RaddadLJ (2014) The emerging face of the HIV epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 9: 183–191.

16. UNODC (2011) United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2011). World Drug Report. Available: http://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/WDR2011/World_Drug_Report_2011_ebook.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2014.

17. BeyrerC, WirtzAL, BaralS, PeryskinaA, SifakisF (2010) Epidemiologic links between drug use and HIV epidemics: an international perspective. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 55(Suppl 1): S10–S16.

18. MoherD, LiberatiA, TetzlaffJ, AltmanDG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6: e1000097.

19. LiberatiA, AltmanDG, TetzlaffJ, MulrowC, GotzschePC, et al. (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 6: e1000100.

20. The Cochrane collaboration (2008) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Hoboken (New Jersey): Wiley-Blackweill.

21. World Health Organization African Index Medicus (AIM). Available: http://indexmedicus.afro.who.int/. Accessed 16 May 2014.

22. World Health Organization Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region (IMEMR). Available: http://www.emro.who.int/lin/imemr.htm. Accessed 16 May 2014.

23. International AIDS Society International AIDS Conference Abstracts. Available: http://www.iasociety.org/Default.aspx?pageId=7. Accessed 16 May 2014.

24. International AIDS Society IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment Abstracts. Available: http://www.iasociety.org/Default.aspx?pageId=7. Accessed 16 May 2014.

25. International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research (ISSTDR) ISSTDR Conference Abstracts. Available: http://www.isstdr.org/previous-meetings.php. Accessed 16 May 2014.

26. U.S Department of Commerce United States Census Bureau International Database, Washington (D.C.). Available: http://www.census.gov/population/international/data/hiv/interactive/. Accessed 16 May 2014.

27. WHO/EMRO Regional database on HIV testing. Cairo: WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean.

28. UNAIDS (2008) UNAIDS/WHO/UNICEF Epidemiological Fact Sheets database on HIV and AIDS. Geneva: UNAIDS.

29. VickermanP, MartinNK, HickmanM (2012) Understanding the trends in HIV and hepatitis C prevalence amongst injecting drug users in different settings–implications for intervention impact. Drug Alcohol Depend 123: 122–131.

30. VickermanP, HickmanM, MayM, KretzschmarM, WiessingL (2010) Can hepatitis C virus prevalence be used as a measure of injection-related human immunodeficiency virus risk in populations of injecting drug users? An ecological analysis. Addiction 105: 311–318.

31. MathersBM, DegenhardtL, PhillipsB, WiessingL, HickmanM, et al. (2008) Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet 372: 1733–1745.

32. IDU Reference Group, The reference group to the UN on HIV and Injecting Drug Use. Available: https://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/project/injecting-drug-users-reference-group-reference-group-un-hiv-and-injecting-drug-use. Accessed 16 May 2014.

33. United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospects: the 2010 Revision Population Database. Available: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/index.htm. Accessed 16 May 2014.

34. UNAIDS/WHO working group on global HIV/AIDS and STI surveillance (2011) Guidelines on surveillance among populations most at risk for HIV. Geneva: WHO Press. Available: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2011/20110518_Surveillance_among_most_at_risk.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2014.

35. WilsonD, HalperinDT (2008) “Know your epidemic, know your response”: a useful approach, if we get it right. Lancet 372: 423–426.

36. UNAIDS/WHO working group on global HIV/AIDS and STI surveillance (2011) Guidelines for second generation HIV surveillance: an update: know your epidemic. Geneva: WHO Press. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85511/1/9789241505826_eng.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2014.

37. Pakistan National AIDS Control Program (2011) HIV second generation surveillance In Pakistan. National report round IV. Canada-Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project. National Aids Control Program, Ministry Of Health, Pakistan. Available: http://www.nacp.gov.pk/library/reports/Surveillance%20&%20Research/HIV-AIDS%20Surveillance%20Project-HASP/HIV%20Second%20Generation%20Surveillance%20in%20Pakistan%20-%20National%20report%20Round%20IV%202011.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2014.

38. Afghanistan National AIDS Control Program (2010) Integrated Behavioral & Biological Surveillance (IBBS) in Afghanistan: year 1 report. HIV Surveillance Project - Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, National AIDS Control Program, Ministry of Public Health. Kabul, Afghanistan.

39. Afghanistan National AIDS Control Program (2012) Integrated Behavioral & Biological Surveillance (IBBS) in selected cities of Afghanistan: findings of 2012 IBBS survey and comparison to 2009 IBBS survey. Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, National AIDS Control Program, Ministry of Public Health. Kabul, Afghanistan.

40. Family Health International and Ministry of Health Egypt (2006) HIV/AIDS Biological & Behavioral Surveillance Survey: round one summary report, Cairo, Egypt 2006. FHI in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and support from USAID – IMPACT project. Available: http://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/EgyptBioBSSsummaryreport2006.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2014.

41. SolimanC, RahmanIA, ShawkyS, BahaaT, ElkamhawiS, et al. (2010) HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of male injection drug users in Cairo, Egypt. AIDS 24(Suppl 2): S33–38.

42. Family Health International and Ministry of Health Egypt (2010) HIV/AIDS Biological & Behavioral Surveillance Survey: Round Two Summary Report, Cairo, Egypt 2010. FHI in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and support from the Global Fund. Available: http://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/BBSS%202010_0.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2014.

43. Iran Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Kyoto University School of Public Health (Japan) (2008) Integrated bio-behavioral surveillance for HIV infection among injecting drug users in Iran. Draft of the 1st analysis on the collected data. Tehran: Iran Ministry of Health and Medical Education.

44. Iran Ministry of Public Health (2010) HIV bio-behavioral surveillance survey among injecting drug users in the Islamic Repubic of Iran. Final report [Persian], Tehran: Iran Ministry of Public Health.

45. Jordan National AIDS Program (2010) Preliminary analysis of Jordan IBBSS among injecting drug users. Amman: Ministry of Health.

46. MahfoudZ, AfifiR, RamiaS, El KhouryD, KassakK, et al. (2010) HIV/AIDS among female sex workers, injecting drug users and men who have sex with men in Lebanon: results of the first biobehavioral surveys. AIDS 24(Suppl 2): S45–S54.

47. MirzoyanL, BerendesS, JefferyC, ThomsonJ, Ben OthmanH, et al. (2013) New evidence on the HIV epidemic in Libya: why countries must implement prevention programs among people who inject drugs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 62: 577–583.

48. Kingdom of Morocco Ministry of Public Health (2012) Country Report on UNGASS Declaration of Commitment. Rabat: Kingdom of Morocco Ministry of Public Health

49. Palestine Ministry of Health (2011) HIV bio-behavioral survey among injecting drug users in the East Jerusalem Governorate, 2010. Ramallah: Palestine Ministry of Health.

50. Pakistan National AIDS Control Program (2008) HIV second generation surveillance in Pakistan. National Report Round III. Canada-Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project. National Aids Control Program, Ministry Of Health, Pakistan. Available: http://www.nacp.gov.pk/library/reports/Surveillance%20&%20Research/HIV-AIDS%20Surveillance%20Project-HASP/HIV%20Second%20Generation%20Surveillance%20in%20Pakistan%20-%20National%20report%20Round%20III%202008.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2014.

51. Pakistan National AIDS Control Program (2006–07) HIV second generation surveillance in Pakistan. National Report Round II. Canada-Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project. National Aids Control Program, Ministry Of Health, Pakistan. Available: http://www.nacp.gov.pk/library/reports/Surveillance%20&%20Research/HIV-AIDS%20Surveillance%20Project-HASP/HIV%20Second%20Generation%20Surveillance%20in%20Pakistan%20-%20Round%202%20Report%202006-07.pdf. Last accessed 16 May 2014.

52. Pakistan National AIDS Control Program (2005) HIV second generation surveillance in Pakistan. National Report Round I. Canada-Pakistan HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project. National Aids Control Program, Ministry Of Health, Pakistan. Available: http://www.nacp.gov.pk/library/reports/Surveillance%20&%20Research/HIV-AIDS%20Surveillance%20Project-HASP/HIV%20Second%20Generation%20Surveillance%20in%20Pakistan%20-%20Round%201%20Report%20-%202005.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2014.

53. Tunisia Ministry of Health, Tunisian Association for Information and Orientation on HIV (2013) Enquête sérocomportementale du VIH et des hépatites virales C auprès des usagers de drogues injectables en Tunisie [French]. Biobehavioral surveillance of HIV and Hepatitis C among injecting drug users in Tunisia. Tunis: Tunisia Ministry of Health, Tunisian Association for Information and Orientation on HIV.

54. Tunisia Ministry of Health (2010) Synthèse des enquêtes de séroprévalence et sérocomportementales auprès de trois populations à vulnérables au VIH: Les usagers de drogues injectables, les hommes ayant des rapports sexuels avec des hommes et les travailleuses du sexe clandestines en Tunisie [French]. Synthesis of biobehavioral surveillance among the three populations vulnerable to HIV in Tunisia: Injecting drug users, men who have sex with men, and female sex workers. Tunis: Tunisia Ministry of Health.

55. MeysamieA, SedaghatM, MahmoodiM, GhodsiSM, EftekharB (2009) Opium use in a rural area of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 15: 425–431.

56. MeratS, RezvanH, NouraieM, JafariE, AbolghasemiH, et al. (2010) Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus: the first population-based study from Iran. Int J Infect Dis 14(Suppl 3): e113–116.

57. EmmanuelF, BlanchardJ, ZaheerHA, RezaT, Holte-McKenzieM, et al. (2010) The HIV/AIDS Surveillance Project mapping approach: an innovative approach for mapping and size estimation for groups at a higher risk of HIV in Pakistan. AIDS 24(Suppl 2): S77–84.

58. Oman Ministry of Health (2006) HIV risk among heroin and injecting drug users in Muscat, Oman. Quantitative survey. Preliminary data. Muscat: Oman Ministry of Health.

59. Syria Mental Health Directorate, Syria National AIDS Programme (2008) Assessment of HIV risk and sero-prevalence among drug users in greater Damascus. Damascus: Syrian Ministry of Health. UNODC. UNAIDS.

60. Al-HaddadMK, KhashabaAS, BaigBZ, KhalfanS (1994) HIV antibodies among intravenous drug users in Bahrain. J Commun Dis 26: 127–132.

61. Morocco Ministry of Health (February 2010) Situation épidémiologique du VIH/Sida et des IST au Maroc [French]. Epidemiological assessment of HIV/AIDS and STIs in Morocco. Rabat Morocco Ministry of Health.

62. MojtahedzadehV, RazaniN, MalekinejadM, VazirianM, ShoaeeS, et al. (2008) Injection drug use in Rural Iran: integrating HIV prevention into iran's rural primary health care system. AIDS Behav 12: S7–S12.

63. Todd C, Nasir A, Stanekzai MR, Rasuli MZ, Fiekert, et al.. (2010) Hepatitis C and HIV incidence among injecting drug users in Kabul, Afghanistan [Abstract MOPDC101]. In: Proceedings of AIDS 2010 - XVIII International AIDS Conference; 18–23 July 2010; Vienna, Austria.

64. Hadi DHMH, Shujaat PDMGSH, Waheed PDWuZ, Masood PDMGMA (2005) Incidence of hepatitis C virus and HIV among injecting drug users in Northern Pakistan: a prospective cohort study [Abstract MoOa0104]. In Proceedings: IAS 2005 - The 3rd IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment; 24–27 July 2005; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

65. JahaniMR, KheirandishP, HosseiniM, ShirzadH, SeyedalinaghiSA, et al. (2009) HIV seroconversion among injection drug users in detention, Tehran, Iran. AIDS 23: 538–540.

66. Nai Zindagi, Punjab Provincial AIDS Control Program (2009) Rapid situation assessments of HIV prevalence and risk factors among people injecting drugs in four cities of the Punjab. Punjab: Nai Zindagi, Punjab Provincial AIDS Control Program

67. KazerooniPA, LariMA, JoolaeiH, ParsaN (2010) Knowledge and attitude of male intravenous drug users on HIV/AIDS associated high risk behaviors in Shiraz Pir-Banon jail, Fars Province, Southern Iran. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal 12: 334–336.

68. AsadiS, MarjaniM (2006) Prevalence of intravenous drug use-associated infections. Iranian Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases 1: 59–62.

69. ToddCS, NasirA, StanekzaiMR, FiekertK, RasuliMZ, et al. (2011) Prevalence and correlates of HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B and C infection and harm reduction program use among male injecting drug users in Kabul, Afghanistan: A cross-sectional assessment. Harm Reduct J 8: 22.

70. KuoI, ul-HasanS, GalaiN, ThomasDL, ZafarT, et al. (2006) High HCV seroprevalence and HIV drug use risk behaviors among injection drug users in Pakistan. Harm Reduct J 3: 26.

71. HaqueN, ZafarT, BrahmbhattH, ImamG, ul HassanS, et al. (2004) High-risk sexual behaviours among drug users in Pakistan: implications for prevention of STDs and HIV/AIDS. Int J STD AIDS 15: 601–607.

72. Nai Zindagi, UNODCCP, UNAIDS. (1999) Baseline study of the relationship between injecting drug use, HIV and Hepatitis C among male injecting drug users in Lahore. Lahore: Nai Zindagi, UNODCCP, UNAIDS

73. StrathdeeSA, ZafarT, BrahmbhattH, BakshA, ul HassanS (2003) Rise in needle sharing among injection drug users in Pakistan during the Afghanistan war. Drug Alcohol Depend 71: 17–24.

74. AltafA, ShahSA, ZaidiNA, MemonA, Nadeem urR, et al. (2007) High risk behaviors of injection drug users registered with harm reduction programme in Karachi, Pakistan. Harm Reduct J 4: 7.

75. Altaf A, Shah SA, Memon A (2003) Follow up study to assess and evaluate knowledge, attitude and high risk behaviors and prevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV and Syphilis among IDUS at Burns Road DIC, Karachi. External report submitted to UNODC. Karachi: Marie Adelaide Habilitation Programme.

76. ToddCS, NasirA, Raza StanekzaiM, AbedAM, StrathdeeSA, et al. (2010) Prevalence and correlates of syphilis and condom use among male injection drug users in four Afghan cities. Sex Transm Dis 37: 719–725.

77. Aaraj E Report on the situation analysis on vulnerable groups in Beirut, Lebanon. Beirut: Lebanon Ministry of Health.

78. Burns K (2007) Women injecting drug users in Morocco: a study of women's vulnerability to HIV. Unofficial translation from the original French. GTZ Morocco.

79. AlipourA, HaghdoostAA, SajadiL, ZolalaF (2013) HIV prevalence and related risk behaviours among female partners of male injecting drugs users in Iran: results of a bio-behavioural survey, 2010. Sex Transm Infect 89(Suppl 3): iii41–iii44.

80. Mishwar IBBS_Lebanon (2008) Mishwar. An integrated bio-behavioral surveillance study among four vulnerable groups in lebanon: men who have sex with men; prisoners; commercial sex workers and intravenous drug users. Mid-term Report. Beirut: Mishwar IBBS_Lebanon.

81. BaqiS, NabiN, HasanSN, KhanAJ, PashaO, et al. (1998) HIV antibody seroprevalence and associated risk factors in sex workers, drug users, and prisoners in Sindh, Pakistan. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 18: 73–79.

82. ParvizS, FatmiZ, AltafA, McCormickJB, Fischer-HochS, et al. (2006) Background demographics and risk behaviors of injecting drug users in Karachi, Pakistan. Int J Infect Dis 10: 364–371.

83. BokhariA, NizamaniNM, JacksonDJ, RehanNE, RahmanM, et al. (2007) HIV risk in Karachi and Lahore, Pakistan: an emerging epidemic in injecting and commercial sex networks. Int J STD AIDS 18: 486–492.

84. RazzaghiEM, MovagharAR, GreenTC, KhoshnoodK (2006) Profiles of risk: a qualitative study of injecting drug users in Tehran, Iran. Harm Reduct J 3: 12.

85. EmmanuelF, FatimaM (2008) Coverage to curb the emerging HIV epidemic among injecting drug users in Pakistan: delivering prevention services where most needed. Int J Drug Policy 19(Suppl 1): S59–S64.

86. KhananiMR, SomaniM, RehmaniSS, VerasNM, SalemiM, et al. (2011) The spread of HIV in Pakistan: bridging of the epidemic between populations. PLoS ONE 6: e22449.

87. RamezaniA, MohrazM, GachkarL (2006) Epidemiologic situation of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV/AIDS patients) in a private clinic in Tehran, Iran. Arch Iran Med 9: 315–318.

88. Burrows D, Wodak A, WHO (2005) Harm reduction in Iran. Issues in national scale-up. Report for World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO.

89. Nai Zindagi, Punjab Provincial AIDS Control Program (2008) The hidden truth: a study of HIV vulnerability, risk factors and prevalence among men injecting drugs and their wives. Lahore: Government of Punjab.

90. Mumtaz G, Hilmi N, Zidouh A, El Rhilani H, Alami K, et al.. (2010) HIV modes of transmission analysis in Morocco. Rabat: Kingdom of Morocco Ministry of Health and National STI/AIDS Programme, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, and Weill Cornell Medical College - Qatar.

91. MumtazGR, KouyoumjianSP, HilmiN, ZidouhA, El RhilaniH, et al. (2013) The distribution of new HIV infections by mode of exposure in Morocco. Sex Transm Infect 89(Suppl 3): iii49–iii56.

92. GouwsE, CuchiP (2012) on behalf of the International Collaboration on Estimating HIV Incidence by Modes of Transmission (inlcluding Laith J. Abu-Raddad and Ghina R. Mumtaz) (2012) Focusing the HIV response through estimating the major modes of HIV transmission: a multi-country analysis. Sex Transm Infect 88: i76–i85.

93. RutherfordGW, McFarlandW, SpindlerH, WhiteK, PatelSV, et al. (2010) Public health triangulation: approach and application to synthesizing data to understand national and local HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health 10: 447.

94. Tawilah J, Ball A (2003) WHO/EMRO & WHO/HQ Mission to Libyan Arab Jamahiriya to Undertake an Initial Assessment of the HIV/AIDS and STI Situation and National AIDS Programme. Tripoli. 15–19 June 2003.

95. HasnainM (2005) Cultural approach to HIV/AIDS harm reduction in Muslim countries. Harm Reduct J 2: 23.

96. Harm Reduction International (2012) The global state of harm reduction 2012: towards an integrated response. Available: http://www.ihra.net/files/2012/07/24/GlobalState2012_Web.pdf. Accessed 16 May 2014.

97. Asfhar P, Kasrace F (2005) HIV prevention experiences and programs in Iranian Prisons [MoPC0057]. In: Proceedings Seventh International Congress on AIDS in Asia and the Pacific; 1–5 July 2005; Kobe, Japan.

98. WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (2004) Best practice in HIV/AIDS prevention and care for injecting drug abusers: the triangular clinic in Kermanshah, Islamic Republic of Iran. Cairo: WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean.

99. RazaniN, MohrazM, KheirandishP, MalekinejadM, MalekafzaliH, et al. (2007) HIV risk behavior among injection drug users in Tehran, Iran. Addiction 102: 1472–1482.

100. Nassirimanesh B, Trace M, Roberts M (2005) The rise of harm reduction in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Briefing Paper Eight, for the Beckley Foundation, Drug Policy Program. Oxford: The Beckley Foundation.

101. Iran Ministry of Health (2006) Treatment and medical education. Islamic Republic of Iran HIV/AIDS situation and response analysis. Tehran: Iran Ministry of Health.

102. ZamaniS, KiharaM, GouyaMM, VazirianM, NassirimaneshB, et al. (2006) High prevalence of HIV infection associated with incarceration among community-based injecting drug users in Tehran, Iran. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 42: 342–346.

103. UNAIDS/WHO (2004) AIDS epidemic update 2004. Geneva: UNAIDS/WHO.

104. ToddCS, NassiramaneshB, StanekzaiMR, KamarulzamanA (2007) Emerging HIV epidemics in Muslim countries: assessment of different cultural responses to harm reduction and implications for HIV control. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 4: 151–157.

105. ZamaniS, FarniaM, TavakoliS, GholizadehM, NazariM, et al. (2010) A qualitative inquiry into methadone maintenance treatment for opioid-dependent prisoners in Tehran, Iran. Int J Drug Policy 21: 167–172.

106. VazirianM, NassirimaneshB, ZamaniS, Ono-KiharaM, KiharaM, et al. (2005) Needle and syringe sharing practices of injecting drug users participating in an outreach HIV prevention program in Tehran, Iran: a cross-sectional study. Harm Reduct J 2: 19.

107. ZamaniS, VazirianM, NassirimaneshB, RazzaghiEM, Ono-KiharaM, et al. (2010) Needle and syringe sharing practices among injecting drug users in Tehran: a comparison of two neighborhoods, one with and one without a needle and syringe program. AIDS Behav 14: 885–890.

108. Bolhari J, Alvandi M, Afshar P, Bayanzadeh A, Rezaii M, et al.. (2002) Assessment of drug abuse in Iranian Prisons. New York: United National Drug Control Programme (UNDCP).

109. Abu-Raddad L, Akala FA, Semini I, Riedner G, Wilson D, et al.. (2010) Policy notes. Characterizing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Middle East and North Africa: time for strategic action. Middle East and North Africa HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Synthesis Project. World Bank/UNAIDS/WHO Publication. Washington (D.C.): The World Bank Press.

110. WHO/EMRO (2007) Progress towards Universal Access to HIV prevention, treatment and care in the health sector: report on an indicator survey for the year 2007 in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region. Geneva: WHO/EMRO.

111. WHO/EMRO (2008) Progress towards Universal Access to HIV Prevention, treatment and care in the health sector; report on an indicator survey for the year 2007 in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region. Geneva: WHO/EMRO.

112. BenjaberK, ReyJL, HimmichH (2005) A study on antiretroviral treatment compliance in Casablanca (Morocco) [French]. Med Mal Infect 35: 390–395.