Reconstruction of the anterior skull base with free muscle flap after iatrogenic injury

Rekonstrukce přední jámy lební volným svalovým lalokem po iatrogenním poškození

Autoři deklarují, že v souvislosti s předmětem studie nemají žádné komerční zájmy.

Redakční rada potvrzuje, že rukopis práce splnil ICMJE kritéria pro publikace zasílané do biomedicínských časopisů.

Authors:

A. Sukop 1,2; M. Patzelt 1 3; J. Kozák 4; R. Leško 4

Authors‘ workplace:

Department of Plastic Surgery, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Czech Republic

1; Department of Plastic Surgery, Royal Vinohrady Teaching Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic

2; Department of Anatomy, Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Czech Republic

3; Department of Neurosurgery, Second Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Motol University Hospital, Czech Republic

4

Published in:

Cesk Slov Neurol N 2018; 81(6): 707-708

Category:

Letters to Editor

doi:

https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn2018707

Overview

Autoři deklarují, že v souvislosti s předmětem studie nemají žádné komerční zájmy.

Redakční rada potvrzuje, že rukopis práce splnil ICMJE kritéria pro publikace zasílané do biomedicínských časopisů.

Dear Editor,

The anterior skull base is an important barrier between the sinonasal tract and intracranial space [1]. After major neurosurgical resections, traumas or even iatrogenic injury, it is necessary to meticulously close the defect in the skull base. Otherwise, the defect can cause meningitis, epidural abscess, leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or even death [2]. The primary goal is to separate the non-sterile space of the nasal cavity and sterile extradural space. It is also necessary to support the brain and orbit, to reestablish the nasal cavities, to provide volume to decrease dead space and to restore the appearance of the face [3]. There are several techniques for skull base defect closure. In case of small defects, local flaps such as the temporalis muscle are often used. If the defect is larger or infected, distant flaps such as the latissimus dorsi or trapezius muscle should be used. Even better results covering large defects are obtained using free flaps like the rectus abdominis muscle [4,5]. Free flaps have many advantages; they can fill the dead space, cover large defects and provide a well-vascularized environment and stable barrier between the nasopharynx and extradural space [6]. The skull base reconstructions are, however, technically difficult and their failure can cause life-threatening complications.

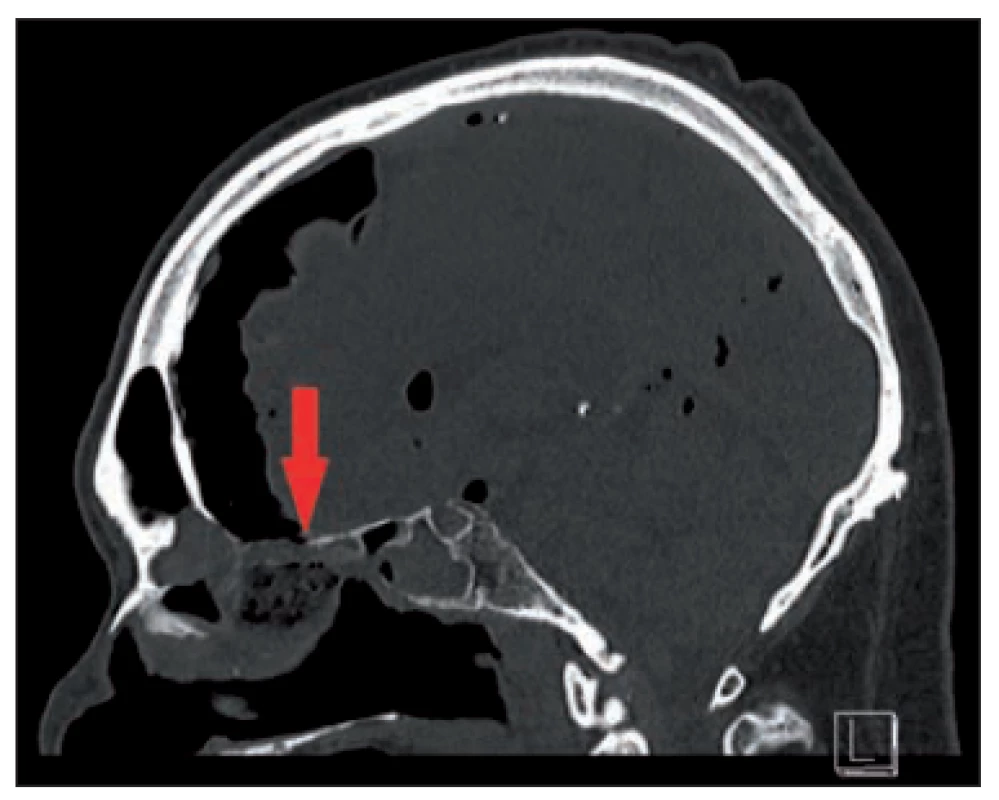

We report on a 70-year-old patient who suffered from chronic osteomyelitis of the frontal bone following trauma. He underwent a common nasal polypectomy and shortly after the procedure, he developed nasal liquorrhea from the right nostril. CT images showed a pneumocephalus and a defect in the right part of the ethmoidal bone (Fig. 1). First, the ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeon indicated closure of the defect with a nasoseptal flap, which showed no effect. A team consisting of a maxillar surgeon, neurosurgeon and ENT surgeon tried to close the defect of the rhinobasis using the pericranial flap for cranialization of the frontal sinus. After the procedure the liquorrhea stopped; however, 2 weeks after the operation the patient’s state deteriorated. He started to be septic with purulent meningitis. PET-CT showed no infectious focus, but repeated nasal endoscopy showed a purulent slime mass. The smears from the rhinobasis and hemoculture examination confirmed the extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumonie and coagulase negative Staphylococcus. Repeated CT and MRI showed no intracranial infectious complication and good cranio-nasal separation. However, the patient was septic, he developed a heavy psychoorganic syndrome and he needed vasopressor therapy with norepinephrine. After repeated nasal endoscopy and debridement, the defect in the rhinobasis reoccurred. Therefore, a team of physicians came up with the last possible solution – closure of the rhinobasis defect with a free muscle flap.

Obr. 1. Předoperační CT, šipka ukazuje

defekt a následně vzniklý pneumocefalus.

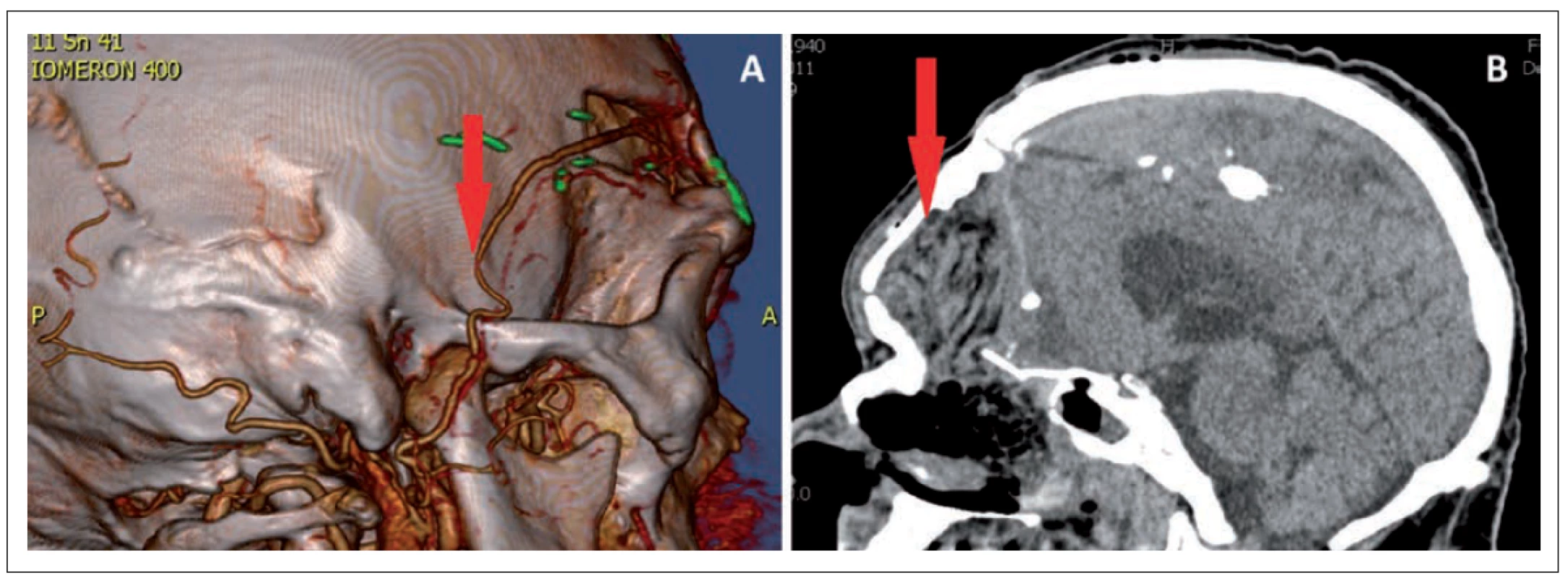

For the reconstruction, we decided to use the left rectus abdominis muscle. Two teams operated on the patient. The first team raised the free muscle flap from a paramedian incision, dissected the inferior epigastric artery and vein and closed the donor site primarily. The second team operated on the head from the old bicoronal incision. We transferred the flap to the defect in the rhinobasis. The flap separated the nasopharynx from the anterior cranial base. We sutured the pedicle vessels to the right superficial temporal artery and vein (Fig. 2A).

Obr. 2. A – CTA, šipka ukazuje arteriální anastomózu, B – CT po 2 dnech od operace, šipka ukazuje lalok.

In the early postoperative period, there was a slight left-sided hemiparesis and minor swelling of the frontal lobes, which was caused by the pressure of the flap and frontal bone. However, both problems subsided gradually. There were no complications related to the flap or donor site. We checked the anastomosis patency via hand Doppler US and CTA. After the operation, the patient showed no sign of liquorrhea, pneumocephalus or infection (Fig. 2B). After 20 days, the skin suture was completely healed.

The patient did not need any other operation since then and the anastomosis was patent at the 1-year follow-up.

Cranial base reconstruction is a life-saving procedure. In the past two decades, several techniques have been developed. Local flaps such as the temporalis muscle represent a good choice for reconstruction, when the defect is small and the soft tissue requirement is minimal [7]. Free muscle flaps like the rectus abdominis muscle or anterolateral thigh are an excellent choice for covering larger defects, since they can easily obliterate dead space; they are suitable for people who underwent radiation therapy and they provide a well-vascularized environment, which is necessary for dealing with infection and for proper healing [5]. For the closure of the defect of the rhinobasis of our patient, we used the free rectus abdominis muscle. Beside our preference, this free flap has a long vascular pedicle with a large diameter, which provides vascular anastomosis outside of the skull. The dissection of this flap is relatively easy and thanks to its localization, it is possible for two teams to work on it simultaneously [8]. With regard to complications at the donor site, there is the possibility of lower abdominal wall weakness [9]. Risk of these complications is minimal when we harvest a unilateral flap. It is also possible to use a fascia lata free flap, which also has a long pedicle and its donor-site morbidity is very low due to a lack of tension. More common free flaps are the latissimus dorsi muscle and gracilis muscle. Latissimus dorsi muscle flap can cover large defects; however, two teams cannot work on it simultaneously. Gracilis flap is suitable for harvesting at the same time while the other surgical team operates on the head; conversely, it has a short vascular pedicle and smaller volume [5]. Comparing local and free flaps, local flaps have lower morbidity at the donor site, easier surgical transfer and shorter operating time. Free flaps are, however, highly resistant to infection, provide a well-vascularized environment and sufficiently cover bone defects, so it is not necessary to use bone grafts. Cranial base reconstruction procedure was perfected during the past few years, mainly due to improvements in microvascular technique, endoscopic equipment and image guidance. However, it is still a very risky operation with many possible complications. The most common ones are CSF fistula, infection, pneumocephalus and free flap pedicle vessel thrombosis.

The skull base defect is a serious condition, which demands well-planned surgery with multidisciplinary cooperation among the ENT surgeon, neurosurgeon and plastic surgeon along with a very good knowledge of the anatomy of the skull base.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manu script met the ICMJE “uniform requirements” for biomedical papers.

Accepted for review: 23. 5. 2018

Accepted for print: 29. 8. 2018

Matěj Patzelt, MD

Department of Plastic Surgery

Third Faculty of Medicine

Charles University

Šrobárova 1150/50

100 34 Prague

Czech Republic

Sources

1. Hoffmann TK, El Hindy N, Müller OM et al. Vascula-rised local and free flaps in anterior skull base reconstruction. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2013; 270(3): 899– 907. doi: 10.1007/ s00405-012-2109-1.

2. Lo KC, Jeng CH, Lin HC et al. A free composite de-epithelialized anterolateral thigh and the vastus lateralis muscle flap for the reconstruction of a large defect of the anterior skull base: a case report. Microsurgery 2011; 31(7): 568– 571. doi: 10.1002/ micr.20919.

3. Pusic AL, Chen CM, Patel S et al. Microvascular reconstruction of the skull base: a clinical approach to surgical defect classification and flap selection. Skull Base 2007; 17(1): 5– 16. doi: 10.1055/ s-2006-959331.

4. Chang DW, Langstein HN, Gupta A et al. Reconstructive management of cranial base defects after tumor ablation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001; 107(6): 1346– 1355. doi: 10.1097/ 00006534-200105000-00003.

5. Şenyuva C, Yücel A, Okur I et al. Free rectus abdominis muscle flap for the treatment of complications after neurosurgical procedures. J Craniofac Surg 1996; 7(4): 317– 321. doi: 10.1097/ 00001665-199607000-00014.

6. Hanasono MM, Silva A, Skoracki RJ et al. Skull base reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011; 128(3): 675– 686. doi: 10.1097/ PRS.0b013e318221dcef.

7. Bakamjian VY, Souther SG. Use of temporal muscle flap for reconstruction after orbito-maxillary resections for cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg 1975; 56(2): 171– 177.

8. Piza-Katzer H. Free allogeneic muscle transfer for cranial reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg 2002; 55(5): 436– 438. doi: 10.1054/ bjps.2002.3857.

9. Urken ML, Turk JB, Weinberg H et al. The rectus abdominis free flap in head and neck reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1991; 117(9): 1031.

Labels

Paediatric neurology Neurosurgery NeurologyArticle was published in

Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

2018 Issue 6

- Memantine Eases Daily Life for Patients and Caregivers

- Possibilities of Using Metamizole in the Treatment of Acute Primary Headaches

- Metamizole at a Glance and in Practice – Effective Non-Opioid Analgesic for All Ages

- Memantine in Dementia Therapy – Current Findings and Possible Future Applications

- Advances in the Treatment of Myasthenia Gravis on the Horizon

-

All articles in this issue

- Diagnostics, symptomatology and findings in diseases and disorders of the autonomic nervous system in neurology

- Patients with extensive early changes (ASPECTS < 5) – recanalization YES

- Patients with extensive early changes (ASPECTS < 5) – recanalization NO

-

Pacient s rozsiahlymi skorými zmenami (ASPECTS < 5) – rekanalizácia

Komentár ku kontroverziám - Pragnancy and multiple sclerosis from a neurologist’s point of view

- Quality of life of caregivers of patients with progressive neurological disease

- New-onset refractory status epilepticus and considered spectrum disorders (NORSE/ FIRES)

- The efficacy of cochlear implantation in adult patients with profound hearing loss

- Clinical results of cervical discectomy and fusion with anchored cage – prospective study with a 24-month follow-up

- A comparison of mini-invasive percutaneous versus classic open pedicle screw fixation of thoracolumbar fractures – retrospective analysis

- Dural reconstruction with usage of xenogenic biomaterial

- Meningococcal meningitis with Chiari malformation (type I)

- Fingolimod attenuates harmaline-induced passive avoidance memory and motor impairments in a rat model of essential tremor

- Comment to the article N. Dahmardeh et al. Fingolimod attenuates harmaline-induced passive avoidance memory and motor impairments in a rat model of essential tremor

- Evaluation of systolic and diastolic cardiac functions and heart rate variability in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

- Reconstruction of the anterior skull base with free muscle flap after iatrogenic injury

- A Bulgarian family with epileptic seizures as a first manifestation of familial cerebral cavernous malformations

- Solitary cerebellar metastasis of uterine cervical carcinoma

- Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- About the journal

Most read in this issue

- Diagnostics, symptomatology and findings in diseases and disorders of the autonomic nervous system in neurology

- New-onset refractory status epilepticus and considered spectrum disorders (NORSE/ FIRES)

- Clinical results of cervical discectomy and fusion with anchored cage – prospective study with a 24-month follow-up

- Pragnancy and multiple sclerosis from a neurologist’s point of view