Authors:

T. Fujimura 1; J. Kinoshita 1; I. Makino 1; K. Nakamura 1; K. Oyama 1; H. Fujita 1; H. Tajima 1; H. Takamura 1; I. Ninomiya 1; H. Kitagawa 1; S. Fushida 1; T. Ohta 1; K. Miwa 2

Authors‘ workplace:

Gastroenterologic Surgery, Kanazawa University Hospital, Kanazawa, Japan

1; Toyama Rosai Hospital, Uozu, Japan

2

Published in:

Rozhl. Chir., 2012, roč. 91, č. 6, s. 346-352.

Category:

Various Specialization

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in gastric carcinogenesis

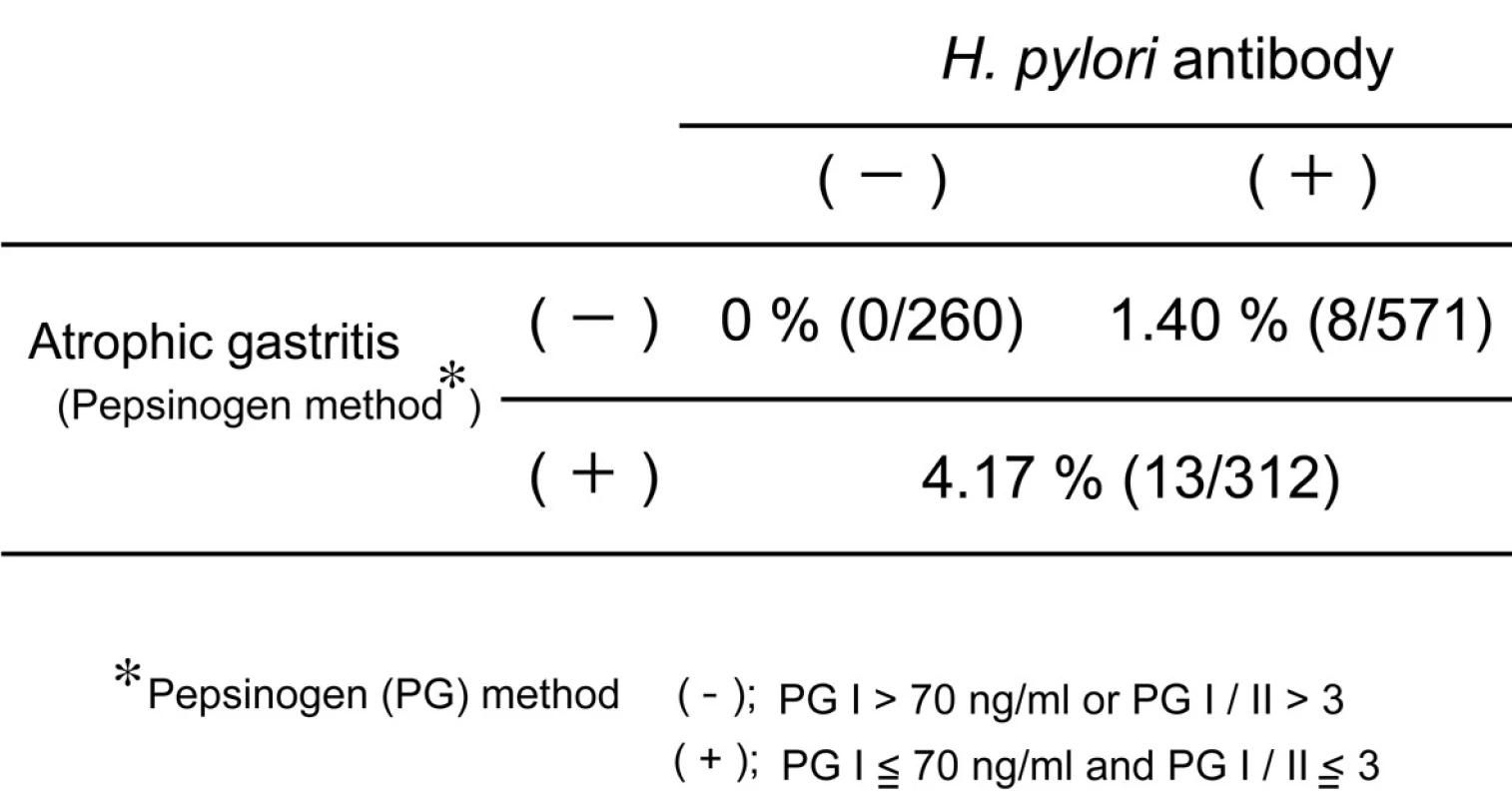

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is strongly associated with development of atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer, especially antral cancer. Previously H. pylori infection was very popular in Japan because of poor socioeconomic circumstance. But recently, the prevalence of H. pylori is less than 20% in younger population, while it is still more than 70 % in elder population. These facts predict that the incidence of antral gastric cancer would decrease in the near future in Japan. Many studies disclosed that eradication of H. pylori reduced the incidence of gastric cancer [1, 2]. But Japanese government permits insurance coverage on H. pylori eradication only for the patients with peptic ulcer, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. The incidence of gastric cancer in the people who did not suffer from H. pylori infection or chronic gastritis was very rare (Table 1). The combination test of serum anti-H. pylori antibody and serum pepsinogen (a marker of atrophic gastritis) is recommended as a useful screening examination of gastric cancer from the viewpoint of a cost-benefit effect. Extensive atrophic gastritis is diagnosed on the pepsinogen (PG) test positive criteria; i.e. PG I equal to or less than70 ng/ml and PG I/II equal to or less than 3. It was reported that no gastric cancer developed in healthy subjects without H. pylori infection and atrophic gastritis during the 7.7-year follow-up period [3]. Thus, screening examination of gastric cancer to such subjects should be performed every 5 years, but not every year.

Staging and treatment algorithm

Gastric cancer is staged according to tumor invasion depth (T category), lymph node metastasis (N category), and distant metastasis (M category) including peritoneal and hepatic metastases by Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. Since Japanese Gastric Cancer Association published the first edition of the classification in 1962, there have been 13 editions gone through. The 14th edition was just published in March, 2010 [4]. There were many systemic differences between the Japanese Classification and the TNM classification by UICC. For example, the N category in the Japanese Classification was classified by the anatomic location of metastatic lymph node while it has been estimated by the number of metastatic lymph node in the TNM classification. But many contents in the 14th edition dramatically changed to fit the 7th edition of the TNM classification. Similarity of both classifications will help to understand staging and treatment of gastric cancer each other.

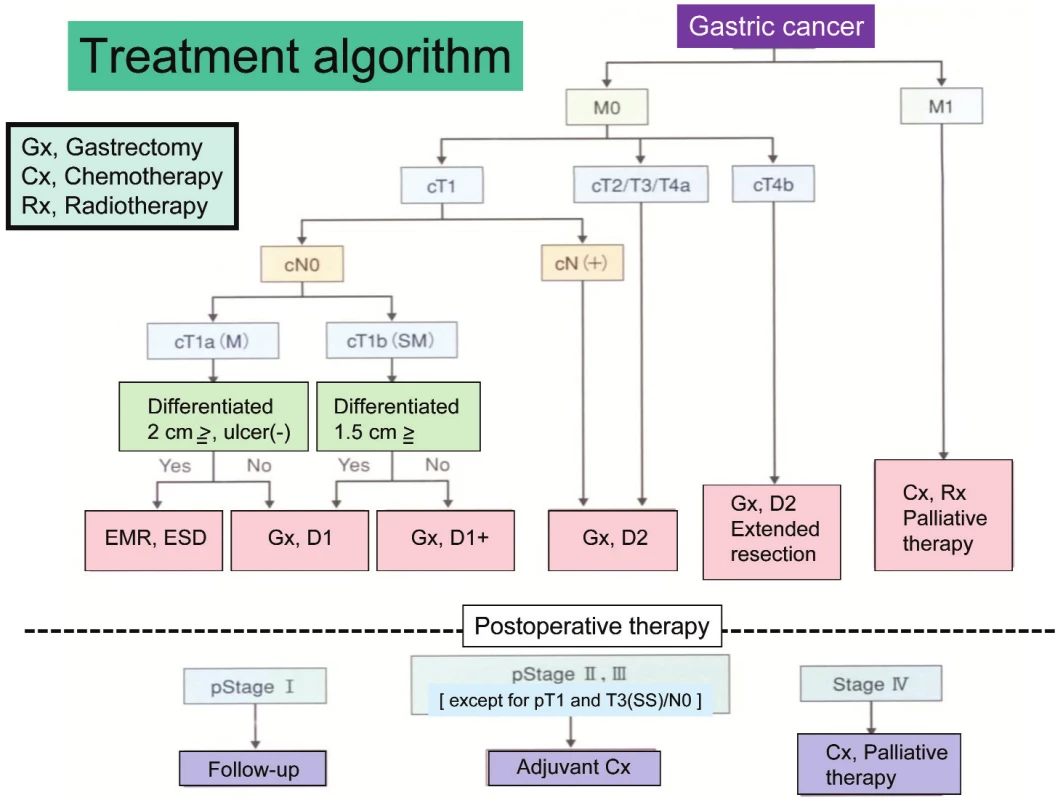

Treatment strategy, decided according to the preoperative staging, is precisely described in Gastric Cancer Treatment Guideline. This Treatment Guideline is also edited by Japanese Gastric Cancer Association and the third edition was just published in Oct, 2010 [5]. The guideline shows indication of treatments including endoscopic therapy, surgery, chemotherapy and palliative therapy using a concise flowchart (Tab. 1). Clinical evidences are necessary to make the Treatment Guideline. Previously many single-institutional studies were independently carried out for finding new therapeutic modalities in Japan. But no study produced any fruits. Recently, several study groups such as JCOG (Japan Clinical Oncology Group), JACCRO (Japan Clinical Cancer Research Organization) and WJOG (West Japan Oncology Group) were established to resolve this problem.

Endoscopic treatments for early gastric cancer

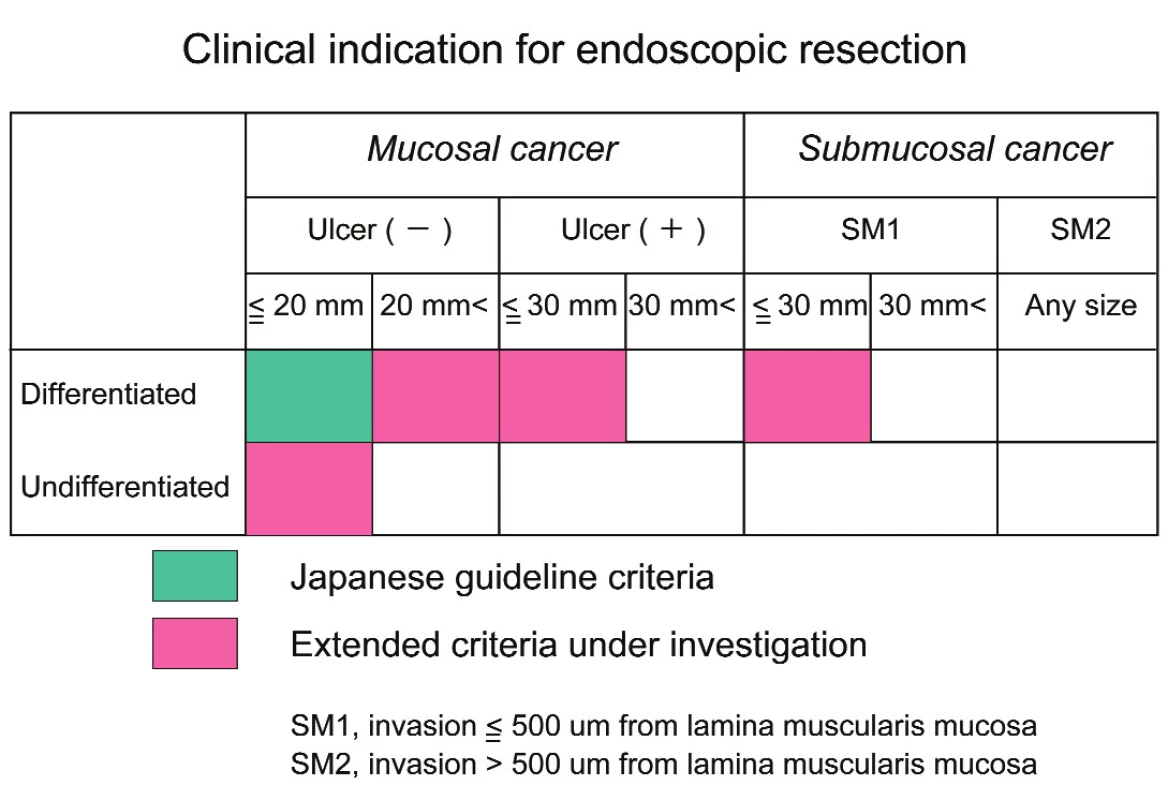

Recently more than 60% patients of gastric cancer had early gastric cancer (mucosal or submucosal cancer) in Japan. Nation-wide screening examination using barium-meal study and upper GI endoscopy contributed to early detection of gastric cancer. Early gastric cancer with mucosal invasion and differentiated-type is treated by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in Japan. EMR and ESD were officially indicated for differentiated-type mucosal cancer with a diameter of less than or equal to 2 cm and without ulceration or radiographic lymph node metastases according to Gastric Cancer Treatment Guideline. ESD is a relatively new technique like an intragastric surgery. It is developed to enable the resection of large and ulcerative lesion, regardless of tumor location. The outcomes of EMR and ESD are satisfactory for the treatment of mucosal gastric cancer by developments of preoperative diagnosis, specialized dissecting devices and physician’s technique (6). Recently the National Cancer Center of Japan extended the indication criteria for ESD to selected cases as a curative procedure depending upon the risk of lymph node metastasis in a large cohort of surgically treated patients with early gastric cancer (Tab. 2).

Surgical treatments for early gastric cancer

But when tumor invades to submucosal layer or has poorly differentiated-type, surgery is necessary. The extent of gastric resection and lymphadenectomy in early gastric cancer is controversial. Conventional gastrectomy with D2 produces postgastrectomy syndrome, including postprandial epigastric fullness, dumping syndrome, cholecystic dysfunction, malnutrition, and regurgitant gastroesophagitis. Since the incidence of lymph node metastasis is 15 to 20%, reductive surgery is expected to improve the postoperative QOL of patients with early gastric cancer. However, blind reduction in lymphadenectomy may run the risk of recurrences in the lymph nodes, liver, and other remote organs. The preoperative and intraoperative diagnoses of lymph node metastasis are essential for reductive surgery. Sentinel node (SN) mapping is expected to assist with the detection of lymph node metastasis intraoperatively. We have validated the SN concept in early gastric cancer [7]. According to the results of several feasibility studies of SN mapping, it was reported that the SN detection rate was as high as 96 to 100% and the sensitivity for lymph node metastasis was 85 to 100%, which seems acceptable for clinical application. Furthermore, a promising outcome of the multi-institutional validation study, conducted by the Japanese Society of SN Navigation Surgery, was reported at the ASCO 2009 meeting. Based on the favorable results of our feasibility study of the SN concept, we have established function-preserving radical gastrectomy using lymphatic basin dissection [8]. Function-preserving radical gastrectomy for early gastric cancer includes local resection, transectional gastrectomy cardia resection, and antral resection.

Function-preserving radical gastrectomy with SN mapping was attempted in 166 patients with early gastric cancer between November, 2000 and August, 2008. Fourteen patients underwent conventional D2 gastrectomy because of macroscopic or microscopic metastasis in the SN. Finally, 60 patients received transectional gastrectomy; local resection in 15, cardia resection in 15, and antral resection in 16. Distal or total gastrectomy was performed in the remaining patients because they did not have lymph node metastasis, but had three lymphatic basins. One patient, who had lymph node metastasis, died of para-aoritc lymph node recurrence, but the remaining 165 patients survived without recurrence, although three died of pneumonia. These results validated the curability of function-preserving radical gastrectomy navigated by SN mapping in early gastric cancer.

Transectional Gastrectomy

Transectional gastrectomy navigated by SN mapping is performed for early gastric cancer of middle third of the stomach without clinical or radiographic lymph node metastases (cT1N0) and with a diameter of less than 4 cm [9]. All macroscopic or histological types are included. SN mapping is carried out by a dual method, using dye and a radioisotope. The radioisotope such as 99mTc-phytate or 99mTc-tin-colloid is injected into the gastric submucosa at four points around the tumor, using upper gastrointestinal endoscope 1 day before surgery, and a dye such as Patent Blue or lymphazurin is injected in the same manner during the operation. About 15 min after the injection of the dye, some lymphatics and lymph nodes are gradually stained blue. We refer to the stained lymph nodes as “blue nodes” and the stained area along a feeding artery as the “lymphatic basin” (Tab. 3).

When lymphatic basins along the left gastric artery and the right gastroepiploic artery are stained, transectional gastrectomy is indicated. Lymphatic basin dissection, i.e. en-bloc dissection of lymphatic basins, is carried out, and blue nodes and radioactive nodes are identified with the naked eye and a gamma probe, respectively, on the side table. Retrieved nodes are submitted to the pathology department for intraoperative biopsy. Transectional gastrectomy is performed if no metastasis is found (Fig. 1). However, if lymphatic metastases are detected, the standard operation, namely, conventional distal gastrectomy (CDG) with D2, is selected. Distal or total gastrectomy is carried out when a patient has more than two lymphatic basins because more than two feeding arteries are resected by lymphatic basin dissection. Gastrotomy is necessary for confirming 2-cm margin from the tumor before transection of the stomach. The resected area of the stomach depends on the tumor size and location on an individual basis.

To confirm the advantages of transectional gastrectomy, postoperative QOL and endoscopic findings were investigated in comparison with CDG. The results of a questionnaire survey among patients indicated greater volume of food intake and body weight gain after transectional gastrectomy than after CDG. Furthermore, redness of gastric mucosa and bile reflux observed endoscopically were less frequent in patients treated with transectional gastrectomy than in those treated with CDG. These observations confirmed the superiority of transectional gastrectomy to CDG with regard to postoperative QOL.

Laparoscopic or laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy

Laparoscopic gastrectomy is performed for early gastric cancer in many institutes. Distal gastrectomy with D1 was first reported, while recently proximal gastrectomy and total gastrectomy were carried out in advanced institutes. But laparoscopic gastrectomy is still a investigational treatment, not a standard one in the Treatment Guideline because no evidence for safety or radicality of laparoscopic gastrectomy has been established. Then, the safety of laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy (LADG) was examined by credentialed surgeons under the phase II setting (JCOG study 0703) [10]. That trial confirmed the safety of LADG in terms of the incidence of anastomotic leakage or pancreatic fistula formation. A phase III trial (JCOG study 0912) to confirm the non-inferiority of LADG to an open gastrectomy in terms of overall survival is ongoing for clinical stage I gastric cancer.

The laparoscopic approach provides minimal invasiveness to the patients, with reduced wound pain and inflammatory responses in the early postoperative period. On the other hand, SN navigation surgery improves QOL in the late postoperative period by limiting stomach resection and lymphadenectomy. The combination of laparoscopic surgery and SN navigation surgery will become an ideal operation for early gastric cancer [11].

Advanced gastric cancer

D2 gastrectomy is defined as a gastrectomy resecting more than two-thirds of whole stomach with a regional lymphadenectomy in the Treatment Guideline. D2 lymphadenectomy means lymph node dissection of stations from #1 to #12a for total gastrectomy, and stations from #1 to #9 and #11p and #12a for distal gastrectomy. D2 gastrectomy has been regarded as a standard operation for advanced gastric cancer in Japan. But there was no significant difference in overall survival between D1(limited) and D2(standard) gastrectomy in the previous Dutch and British randomized trials [12, 13]. Furthermore both trials revealed that D2 gastrectomy showed significantly higher morbidity and mortality compared with D1 gastrectomy. Thus, the D2 gastrectomy could not be recognized as a worldwide standard treatment for advanced gastric cancer. But recently, the 15-year follow-up data of the Dutch Gastric Cancer Trial was disclosed [14]. It was reported that there was no significant difference in 15-year survival between D1 and D2 gastrectomy, while gastric-cancer-related death rate was significantly higher in the D1 group (48%) compared with the D2 group (37%). Additionally, D2 gastrectomy is associated with lower local and regional recurrences compared to D1 gastrectomy. These favorable results from western country would encourage standardization of D2 gastrectomy in the world.

Para-aortic lymph node metastasis

Para-aortic lymph node (PAN) metastasis frequently develops in advanced gastric cancer. Lymph node dissection of PAN has been performed in several institutes to improve survival of the patients with PAN metastasis or with risk factors for PAN metastasis. There were many reports describing risk factors predicting PAN metastases. Macroscopic N stage (N2 to N4), tumor size (equal to or more than 5 cm in diameter), depth of tumor invasion, total number of metastatic lymph nodes, and lymphatic metastases to the stations #7 and #8 were associated with PAN metastasis. But it is difficult to obtain such information correctly before or during operation. To confirm the indication and survival benefit by PAN dissection, the Japanese randomized trial comparing standard D2 with D2 plus additional PAN dissection for advanced gastric cancer was conducted by the JCOG (JCOG study 9501) between July 1995 and April 2001. Unfortunately, that trial did not demonstrate any difference in survival between two groups [15]. But it is unknown whether there is any prognostic benefit in dissection for subgroups of PAN. We examined non-inferiority in survival of the patients with PAN metastasis to the patients having n2-metastasis, according to the subgroup of PANs and the tumor location [16]. The survival curve of n2-patients (n=131) were retrospectively compared with that of patients with PAN metastasis (n=55), and also compared with that of patients with metastasis to subgroup of PANs by the location of primary tumor (regions U, M, and L ). PAN was subgrouped into a1, a2-lat, a2-int, b1-lat, b1-int, and b2 according to Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. Expectedly, the prognosis of the n2-patients is significantly better than that of the patients with PAN metastasis. But there was no difference in the survival times between the n2(+) group and the a2-lat(+) or the b1-int(+) group (Fig 2), suggesting that the a2-lat or the b1-int dissection matched the D2 dissection. Furthermore the importance in dissection of the a2-lat and the b1-int was investigated according to the primary tumor location. The patients with metastasis to a2-lat in the region U, a2-lat and b1-int in the region M, and b1-int in the region L demonstrated prognostic non-inferiority to the patients having n2-metastasis. Selective lymphadenectomy of subgroups of PANs in which metastases are highly suspected according to the tumor location is one of the treatment options to advanced gastric cancer.

Cardia cancer with esophageal invasion

Though the incidence of gastric cancer decreases in almost countries of the world, cardia cancer gradually increases in number not only in the western countries, but also in Japan. Cardia cancer is frequently accompanied with esophageal invasion. Gastric cancer invading esophagus is usually treated with gastrectomy plus lower esophagectomy by transhiatal approach according to the outcome of JCOG study 9502 [17]. But it is very difficult to perform esophagojejunal anastomosis using circular stapler at the middle level in the mediastinum. We use EEA 21 or 25 Tilt Top Plus (OrVil) for intramediastinal esophagojejunostomy (Graph 1). An anvil of this device is orally inserted to the esophagus. During surgery esophagus is obliquely dissected with a linear stapler (GIA Universal). An anvil with an introducer is inserted from mouth to the end of esophagus, where is opened using scissors to get out the tip of the introducer. The anvil is led to the end of esophagus by pulling out the introducer. A string to fix anvil and introducer is cut to place correctly the anvil at the end of esophagus. The anvil and the center rod of a circular stapler are connected and esophagus and jejunum are anastomosed in the manner of hemi-double technique. A special circular stapler, DST Series EEA 21 - or 25 - 4.8 XL Circular Stapler, is used for this anastomosis with the Orvil.

We performed intramediastinal esophagojejunostomy with the Orvil after total gastrectomy with lower esophagectomy in three patients, and proximal gastrectomy with lower esophagectomy in four. Tumor ranged in size from 3 to 9.5 cm (Average 5 cm); macroscopic tumor invasion ranged in length from 10 to 55 mm (Average 23 mm) and the length of resected esophagus ranged from 20 to 60 mm (Average 40 mm). The postoperative morbidity included one major leakage and one minor leakage, which were cured with conservative therapies. Thus, esophagojejunal anastomosis using Orvil after transhiatal lower esophagectomy is a feasible and useful technique to simplify intramediastinal anastomosis.

Furthermore around 10% patients of cardia cancer invading lower esophagus directly infiltrates diaphragm. In particular, the diaphragmatic infiltration is frequent in the cardia cancer with serosal invasion and more than 2-cm invasion toward lower esophagus. In the case of cardia cancer with the diaphragmatic infiltration, cancer nests in the diaphragm must remain by the gastrectomy with lower esophagectomy using a regular transhiatal approach. Thus, we have developed a complete resection of the diaphragmatic infiltration in gastric cancer using the technique of perihiatal phrenic resection (Fig 3). Basically, we perform total or proximal gastrectomy and splenectomy with D2 and #16a2 lat lymph node dissection for advanced cardia cancer. When the diaphragmatic infiltration is suspected, we circumferentially resect the radix of diaphragm surrounding esophagus with around 1-cm cuff and lineally cut the diaphragm in the ventral direction to expose lower mediastinum. After lymph node dissection of #110 and #111, the esophagus is transected. Reconstruction of intestinal continuity is carried out by double tract method using circular staplers or Orvil as mentioned before in both esophagojejunal and jejunoduodenal anastomoses.

Chemotherapy

Up to the end of the 20th century continuous 5-FU intravenous administration (5-FU civ) was only standard regimen of chemotherapy for unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric cancer in Japan. JCOG study 9912 demonstrated that there was no difference in the prognosis of advanced or recurrent gastric cancer between 5-FU civ and S1 (an oral compound of 5FU, 5-chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyrimidine, and potassium oxonate) and SPIRITS trial revealed a superiority of S1 + CDDP to S1 alone in both overall and progression-free survival in the first decade of the 21st century [18, 19]. Furthermore, S1 monotherapy was compared to other combination therapies such as S1 + irinotecan (TOP002/GC0301) and S1 + docetaxel (START/ JACCRO GC03). But both trials failed to show significant prognostic benefits though median survival times of these combined therapies were long by 2 months compared to S1 monotherapy. Thus S1 + CDDP regimen is now a standard chemotherapy in Japan. Its treatment schedule is as follows; S1 is orally administered at 80 mg/m2/day, 3-week on, 2-week off and CDDP is intravenously at 60 mg/m2, on Day 8.

More recently, 5FU + CDDP/capecitabine + CDDP regimen in combination with trastuzumab to the HER2-positive gastric cancer was permitted for insurance coverage in Japan, according to the outcomes of ToGA study. Such molecular targeted therapy, triplet chemotherapy and second-line chemotherapy will be established in the near future to improve far-advanced and recurrent gastric cancer.

Takashi Fujimura

Gastroenterologic Surgery, Kanazawa University,

13–1 Takaramachi, Kanazawa, 920-8641, Japan

e-mail: tphuji@staff.kanazawa-u.ac.jp

Sources

1. Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med 2001;345 : 784–789.

2. Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, et al. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008,372 : 392–397.

3. Ohata H, Kitauchi S, Yoshimura N, et al. Progression of chronic atrophic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori infection increases risk of gastric cancer. Int J Cancer 2004;109 : 138–143.

4. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association Japanese: Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma, Fourteenth Edition. Kanehara, Tokyo, 2010. (in Japanese)

5. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association; Gastric Cancer Treatment Guideline, Third Edition. Kanehara, Tokyo, 2010. (in Japanese)

6. Oda I, Saito D, Tada M, et al. A multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2006;9 : 262–270.

7. Miwa K, Kinami S, Taniguchi K, et al. Mapping sentinel nodes in patients with early-stage gastric carcinoma. Br J Surg 2003;90 : 178–182.

8. Fujimura T, Kinami T, Fushida S, et al. Limited Surgery (Function-preserving curative gastrectomy) for Gastric Cancer Shokakigeka (Gastroenterological Surgery) 2008, 31 : 708–715. (in Japanese)

9. Fujimura T, Fushida S, Kayahara M, et al. Transectional gastrectomy:An old but renewed concept for early gastric cancer. Surg Today 2010;40 : 398–403.

10. Katai H, Sasako M, Fukuda H, et al. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with suprapancreatic nodal dissection for clinical stage I gastric cancer: a multicenter phase II trial (JCOG 0703) Gastric Cancer 2010;13 : 238–244.

11. Kitagawa Y, Kitano S, Kubota T, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for gastric cancer – toward a confluence of two major streams: a review Gastric Cancer 2005;8 : 103-110.

12. Cuschieri A, Weeden S, Fielding J, et al. Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: long-term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial. Surgical Co-operative Group, Br J Cancer 1999;79 : 1522–1530.

13. Bonenkamp JJ, Hermans J, Sasako M, et al. Dutch Gastric Cancer Group. Extended lymph-node dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med 1999;340 : 908–914.

14. Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, et al. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11 : 439–449.

15. Sasako M, Sano T, Yamamoto S, et al. D2 lymphadenectomy alone or with para-aortic nodal dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med 2008;359 : 453–462.

16. Fujimura T, Nakamura K, Oyama K, et al. Selective lymphadenectomy of para-aortic lymph nodes for advanced gastric cancer. Oncol Rep 2009;22 : 509–514.

17. Sasako M, Sano T, Yamamoto S, et al. Left thoracoabdominal approach versus abdominal-transhiatal approach for gastric cancer of the cardia or subcardia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2006;7 : 644–651.

18. Boku N, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H, et al. Gastrointestinal Oncology Study Group of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group. Fluorouracil versus combination of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus S-1 in metastatic gastric cancer: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2009;10 : 1063–1069.

19. Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, et al. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 2008;9 : 215–221.

Labels

Surgery Orthopaedics Trauma surgeryArticle was published in

Perspectives in Surgery

2012 Issue 6

- Possibilities of Using Metamizole in the Treatment of Acute Primary Headaches

- Metamizole vs. Tramadol in Postoperative Analgesia

- Spasmolytic Effect of Metamizole

- Metamizole at a Glance and in Practice – Effective Non-Opioid Analgesic for All Ages

-

All articles in this issue

- Meckel´s diverticulum in adults – our five-year experience

- Comparison of laparotomic and laparoscopic techniques for implantation of the peritoneal part of the shunt in the treatment of hydrocephalus

- Percutaneous interspinous dynamic stabilization (In-Space) in patients with degenerative disease of the lumbosacral spine – a prospective study

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia – awareness of the general public and quality of preventive care

- The significance of biological intracranial meningioma behaviour for their long-term management

- Laparoscopic appendectomy in pregnancy – a case report

- Treatment of an asymptomatic splenic cyst using percutaneous drainage

- Metastasis of breast cancer in gastointestinal tract – report of a case and review of the literature

- Perspectives in Surgery

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- About the journal

Most read in this issue

- Treatment of an asymptomatic splenic cyst using percutaneous drainage

- Meckel´s diverticulum in adults – our five-year experience

- Laparoscopic appendectomy in pregnancy – a case report

- Percutaneous interspinous dynamic stabilization (In-Space) in patients with degenerative disease of the lumbosacral spine – a prospective study