-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Altered Gene Expression and DNA Damage in Peripheral Blood Cells from Friedreich's Ataxia Patients: Cellular Model of Pathology

The neurodegenerative disease Friedreich's ataxia (FRDA) is the most common autosomal-recessively inherited ataxia and is caused by a GAA triplet repeat expansion in the first intron of the frataxin gene. In this disease, transcription of frataxin, a mitochondrial protein involved in iron homeostasis, is impaired, resulting in a significant reduction in mRNA and protein levels. Global gene expression analysis was performed in peripheral blood samples from FRDA patients as compared to controls, which suggested altered expression patterns pertaining to genotoxic stress. We then confirmed the presence of genotoxic DNA damage by using a gene-specific quantitative PCR assay and discovered an increase in both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA damage in the blood of these patients (p<0.0001, respectively). Additionally, frataxin mRNA levels correlated with age of onset of disease and displayed unique sets of gene alterations involved in immune response, oxidative phosphorylation, and protein synthesis. Many of the key pathways observed by transcription profiling were downregulated, and we believe these data suggest that patients with prolonged frataxin deficiency undergo a systemic survival response to chronic genotoxic stress and consequent DNA damage detectable in blood. In conclusion, our results yield insight into the nature and progression of FRDA, as well as possible therapeutic approaches. Furthermore, the identification of potential biomarkers, including the DNA damage found in peripheral blood, may have predictive value in future clinical trials.

Published in the journal: Altered Gene Expression and DNA Damage in Peripheral Blood Cells from Friedreich's Ataxia Patients: Cellular Model of Pathology. PLoS Genet 6(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000812

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000812Summary

The neurodegenerative disease Friedreich's ataxia (FRDA) is the most common autosomal-recessively inherited ataxia and is caused by a GAA triplet repeat expansion in the first intron of the frataxin gene. In this disease, transcription of frataxin, a mitochondrial protein involved in iron homeostasis, is impaired, resulting in a significant reduction in mRNA and protein levels. Global gene expression analysis was performed in peripheral blood samples from FRDA patients as compared to controls, which suggested altered expression patterns pertaining to genotoxic stress. We then confirmed the presence of genotoxic DNA damage by using a gene-specific quantitative PCR assay and discovered an increase in both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA damage in the blood of these patients (p<0.0001, respectively). Additionally, frataxin mRNA levels correlated with age of onset of disease and displayed unique sets of gene alterations involved in immune response, oxidative phosphorylation, and protein synthesis. Many of the key pathways observed by transcription profiling were downregulated, and we believe these data suggest that patients with prolonged frataxin deficiency undergo a systemic survival response to chronic genotoxic stress and consequent DNA damage detectable in blood. In conclusion, our results yield insight into the nature and progression of FRDA, as well as possible therapeutic approaches. Furthermore, the identification of potential biomarkers, including the DNA damage found in peripheral blood, may have predictive value in future clinical trials.

Introduction

Friedreich's ataxia (FRDA; OMIM# 229300) is the most common autosomal-recessively inherited ataxia beginning in childhood and leading to death in early adulthood. Patients exhibit neurodegeneration of the large sensory neurons and spinocerebellar tracts, along with variable systemic manifestations that include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, scoliosis, and diabetes mellitus (see http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/dispomim.cgi?id=229300).

FRDA results from the partial loss of frataxin (FXN; Entrez Gene ID 2395), a small nuclear encoded 18-kDa protein targeted to the mitochondrial matrix [1]. A GAA triplet repeat expansion in the first intron impairs transcription of frataxin, resulting in a significant reduction in mRNA and protein levels [2]–[4]. The exact physiological function of frataxin is still unclear, but it has been shown to bind iron and play a role in iron-sulfur cluster (ISC) assembly [5],[6]. A decrease in frataxin may also increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by increases in bioavailable iron [5], [7]–[10] and the lack of iron detoxification [11]. The conclusions of several studies indicate that a defect in ISC assembly is the primary event in frataxin-deficient cells [5], [12]–[14] and that ROS production is a secondary event [8],[15]. Napoli et al. [12] believe the dysfunction of biosynthesis of mitochondrial iron-sulfur clusters, and deficiency of ISC enzyme activity, produces a defect in heme, which in turn causes a loss of cytochrome C. Impairment of electron transport activity results in higher levels of ROS production [14], and according to Napoli et al. [12], it is the decrease in cytochrome C that leads to the unchecked increase in production of mitochondrial ROS in Friedreich's ataxia patients. This hypothesis is further supported by studies of yeast strains with reduced frataxin, which accumulate mitochondrial iron and generate reactive hydroxyl radicals that damage membranes, proteins, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), ultimately resulting in the decreased capacity for ATP synthesis through impaired oxidative phosphorylation [15],[16]. Moreover, evidence consistent with nuclear DNA (nDNA) damage is demonstrated by decreasing the levels of frataxin in a RAD52 (854976) double-strand break repair deficient yeast strain, which results in rapid G2/M cell cycle arrest [16].

In FRDA patients, iron deposition is observed in neuronal and myocardial cells and suggests the potential for free radical damage [17],[18]; however, we note that the case for oxidative stress has been somewhat controversial. Cell models support sensitivity to oxidative stress, and patient studies have found markers of oxidative stress [7],[19],[20], but a conditional knock-out (KO) mouse model did not show oxidative stress, or improvement, when overexpressing superoxide dismutase (SOD) [21]. Recent studies have also failed to replicate the previous marker data [22],[23]. Therefore, it is important to examine other markers of oxidative stress by more sensitive and specific means, such as testing for mtDNA damage in the patient. There is good evidence to suggest that hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which leads to the death of most FRDA patients, is probably a consequence of iron-catalyzed Fenton chemistry causing damage to mitochondrial macromolecules followed by muscle fiber necrosis and a chronic reactive myocarditis [24]. More work is needed to understand the causes of the pathobiology associated with the progression of FRDA.

While genome-wide scans in frataxin-deficient model organisms and mammalian cells have previously been published [15], [25]–[27], we report the first study involving transcription profiling of total blood from children with FRDA. These gene expression data were further validated in a second cohort of adults with FRDA, who were compared to an independent group of controls. Importantly, we observed previously unreported signatures of gene expression associated with DNA damage responses. Based on these results, we further analyzed patient mitochondrial and nuclear DNA from peripheral blood and detected high levels of damage as compared to control samples. These results provide insights into the nature of the disease and a working model for frataxin deficiency in humans.

Results

Microarray analysis of global gene expression in total blood from children with FRDA

We set out to identify mechanisms involved in the nature and progression of Friedreich's ataxia by analyzing global gene expression changes in blood samples from 28 FRDA children involved in an idebenone clinical trial [22] (Table S1). Blood samples were collected from the children prior to the administration of idebenone. The protocol only allowed one 8.5 ml sample of blood for the RNA isolation, which resulted in a limited amount of RNA for this study. Furthermore, control unaffected children were not included in this clinical trial; therefore, we used the youngest control adults available from an NIEHS sponsored study [28] for the gene expression analysis (Table S1).

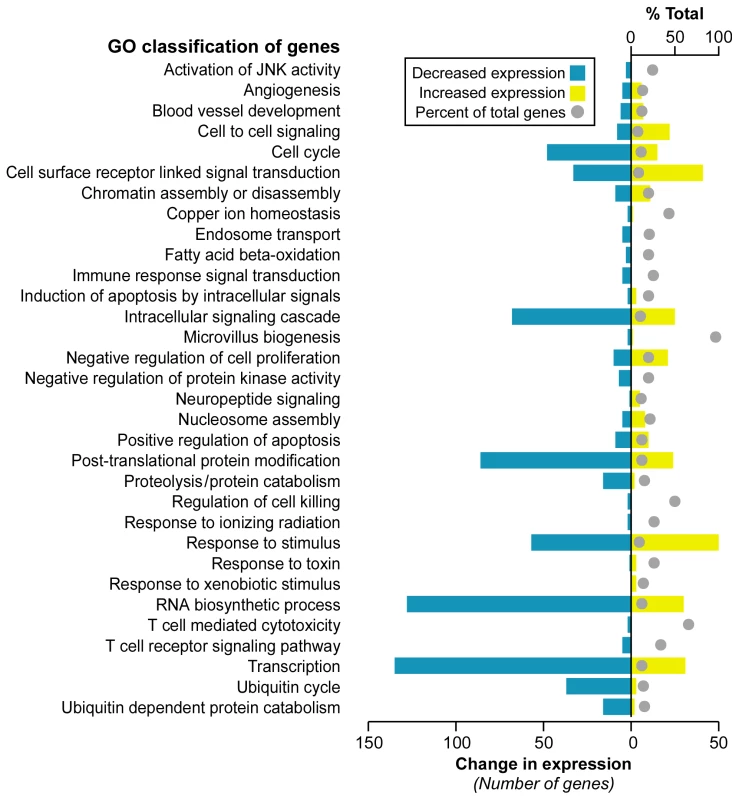

Significance Analysis of Microarray (SAM) [29] identified 1,370 differentially expressed genes at a false discovery rate (FDR) less than 0.023% (Dataset S1). A majority of genes, 899, were downregulated in FRDA compared with control, while 471 genes were upregulated. We further investigated whether these altered transcripts (FDR<0.023%) were associated to specific gene ontology (GO) terms, at p≤0.05, in order to assess the global impact of FRDA on gene expression. This analysis identified significant functional groups that included apoptosis signaling, transcription/RNA processing, cell-cell signaling, cell cycle, ubiquitin cycle, proteolysis/protein catabolism, response to stimuli, and fatty acid beta-oxidation (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Selected gene classifications according to biological processes.

Significantly regulated genes (SAM FDR<0.023%; n = 1,370) from FRDA children versus healthy young adults were grouped according to the gene ontology category of biological process (p≤0.05 in updown, over, or under [expression] output lists). The percent of total (displayed with a gray ball) is based on the number of significantly changed genes out of the total number of genes assigned to each gene ontology term. The change in expression for each GO term is depicted in yellow for upregulation and blue for downregulation. Although age-matched control children were not available for this study, we decided not to use data uploaded to GEO by other laboratories. It is important to minimize cross-platform differences, which can give rise to large technical variation that may obscure small biological differences in blood cells. Therefore, the controls we used were gene expression profiles from young adults processed in our same facility, on the same oligonucleotide chip design, by the same operator. However, we did assess what effect age might have on gene expression by using SAM to test for any association. This analysis was performed in the controls, and age was dichotomized by comparison to the median age of the controls. Age was not found to be associated with any gene expression value after multiple testing correction (min q = 0.47); thus no age-specific gene expression changes were discerned in our control group.

Gene Set Analysis reveals common gene signatures to genotoxic stress responses in children and a validation cohort of adults with FRDA

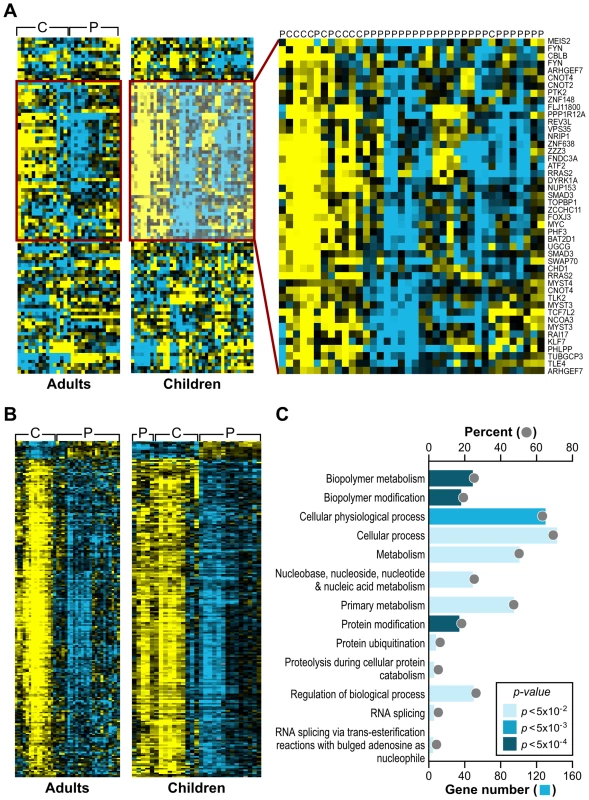

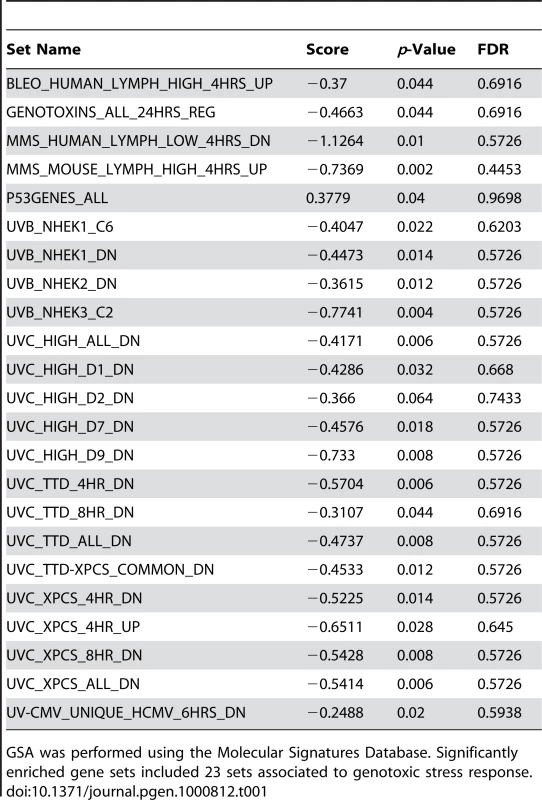

As an alternative approach to gene ontology enrichment analysis, the microarray data for children with FRDA were further analyzed by employing Gene Set Analysis (GSA), a tool that uses predefined gene sets to identify significant biological changes in microarray datasets [30],[31]. We searched for significantly associated gene sets from Molecular Signatures Database subcatalog C2, a database of 1684 microarray experiment gene sets, pathways, and other groups of genes [31]. The analysis yielded many biologically informative sets (Dataset S2) consisting of genes enriched in brain cortex and heart atria, as well as biological processes such as mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation, and reactive oxygen species. The application of GSA also identified 23 gene sets associated to genotoxic stress response (Table 1). P53genes_all is composed of transcriptional targets of p53 (7157), a regulator of gene expression in response to various signals of genotoxic stress, with genes such as GADD45A (1647), PMAIP1 (5366), and SESN1 (27244) displaying repressed expression. Genotoxins_all_24h_reg consists of downregulated genes regulated in mouse lymphocytes at 24 hours by cisplatin, methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), mitomycin C, taxol, hydroxyurea, and etoposide [32]. Other gene sets consist of mostly downregulated genes in response to bleomycin, MMS, ultraviolet B (UVB), and ultraviolet C (UVC) radiation, which were also downregulated in the FRDA dataset (denoted by the negative GSA scores) (Table 1). We next asked if there were genes in common across the 23 genotoxic-stress-response gene sets. Transcripts present in at least 25% of the gene lists (81 genes total) were subjected to unsupervised clustering and displayed segregation into two groups of controls and patients (Figure 2A, right panels, and Dataset S3). Most of these genes fall in the gene ontology categories of transcription, signal transduction, and cell cycle (data not shown).

Fig. 2. Analogous gene expression responses in blood from children and adults with FRDA.

(A) A common gene signature is representative of a genotoxic stress response found by Gene Set Analysis. Twenty-three genotoxic stress response gene sets were searched for common genes. This heat map, generated by unsupervised clustering, displays the genes present in at least 6 of the 23 gene sets and compares transcript levels between FRDA patients, the adult and children cohorts, and controls. Yellow = upregulated; Blue = downregulated. C = Control; P = Patient. Note that while three patients and one control did not segregate with their respective groups, all adult patients and controls clustered in two separate groups in this unsupervised clustering. (B) Heat-map generated by unsupervised clustering of FRDA and control samples, which displays the overlap of significantly differentially expressed genes (SAM FDR<0.023%; n = 228) in the FRDA children and FRDA adults (overlap p≤0.007). C = control; P = patient. (C) A selected list of significant GO groups representing the overlap gene list described in (B). All controls used for comparison to the FRDA children are young adults (see Table S1). The percent of total (displayed with a gray ball) is based on the number of significantly changed genes out of the total number of genes assigned to each gene ontology term. The gene number for each GO group is shown with a blue bar, the intensity of which is indicative of the p-value. Tab. 1. Gene Set Analysis demonstrates a signature of DNA damage in FRDA patients.

GSA was performed using the Molecular Signatures Database. Significantly enriched gene sets included 23 sets associated to genotoxic stress response. To validate the gene expression changes observed in the child FRDA cohort, we examined an adult FRDA cohort (n = 14). These patients were compared with a new group of 15 adult controls, obtained from an NIEHS sponsored study [28] (Table S2). SAM analysis yielded 2,874 genes at an FDR of less than 0.018% (Dataset S4). This dataset was also analyzed with GSA, yielding significant gene sets related to genotoxic stress response, DNA repair, insulin response, and apoptosis (Dataset S5). When we performed unsupervised clustering of the same list of 81 genes found in the children with FRDA, we observed a similar segregation of patients from controls in this independent group of adults (Figure 2A), thus helping to validate this gene set.

The FRDA adult and FRDA children's datasets were further compared by limiting to significant SAM genes in common and taking into account the direction of differential expression. As stated earlier, a total of 1370 probesets were found significant in the children's cohort (FDR<0.023%), and the median FDR for these probesets in the second cohort was 0.34%. These analyses resulted in 228 mostly downregulated genes in common in both gene sets (FDR<0.018%; overlap p = 0.007 – based on the probability of the hypergeometric distribution) (Figure 2B). This list of 228 genes was analyzed for specific GO category enrichment (Figure 2C) (categories similar to those displayed in Figure 1 are not included; for the full list, see Table S3) and significantly associated to ubiquitin cycle, protein ubiquitination, and proteolysis/catabolism, as well as cell cycle. Using the Ingenuity Knowledge Base (see Materials and Methods), we further mapped the genes to biological function categories and specific pathways, which included apoptosis signaling and oxidative phosphorylation (Table S4). Additionally, the Fisher's exact test was used to search the Molecular Signatures Database for gene sets enriched with genes found in the overlap. These results yielded similar genotoxic gene sets as those observed with the children's data as a whole (Table S5).

FRDA patients have significant mitochondrial and nuclear DNA lesions

Having seen a genotoxic stress response in the microarray data of the FRDA patients, we sought to validate these findings and test whether damage to the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes is elevated in patients with FRDA. Moreover, although genotoxic responsive gene sets in the children and adult cohorts had highly significant p-values, some had high false discovery rates, requiring further biological validation.

Blood DNA from the same 28 children studied for gene expression was analyzed using a quantitative PCR (QPCR) assay to detect DNA damage [33]. In addition to the 28 children evaluated by gene expression profiling, we obtained 19 more DNA samples from affected children in the same clinical study (Table S6) [22]. Only one 8.5 ml sample, per child, of whole blood was allotted for DNA isolation; all DNA samples were prepared by one person using the same protocol (see Materials and Methods). Blood from 15 young adults was obtained from an NIH blood bank in Bethesda, MD and used as controls (Table S6).

The QPCR technique we used has successfully identified lesions in nDNA and mtDNA, resulting from oxidative stress, in a number of organisms, including human and rat cell cultures [34]–[36], yeast [16], and mice [37]. However, this is the first time the assay has been used for DNA derived from human blood. The approach involves the amplification of a large 8.9 kb and 12.2 kb fragment for mtDNA and nDNA, respectively. Previous work by our group suggests that damage is distributed evenly throughout both genomes [34],[38],[39]. The large mtDNA amplification product constitutes ∼54% of the genome and is the representative of the overall genome. The primers used to amplify the product were designed to specifically avoid the D-loop region – a region that is often single-stranded and could increase DNA damage because of its high mutation frequency. Additionally, amplification of a short, ∼200 bp mtDNA fragment, which due to its small size has less chance of containing a lesion, is used to normalize for mitochondrial copy number in the amplification of the large mtDNA fragment. Oxidative damage induces a spectrum of lesions, such as strand breaks, abasic sites, and some base damage (i.e. thymine glycol), which interfere with the progression of the thermostable polymerase to replicate the template DNA. Thus, during amplification, the presence of an oxidative lesion results in the inability of the polymerase to synthesize the template DNA. The final amount of amplified DNA is inversely proportional to the number of oxidative lesions. The QPCR gene-specific damage assay is based on differential amplification of target genes in affected controls as compared to a control population. Excess DNA damage in the affected group will show as a decrease in amplification as compared to the control group.

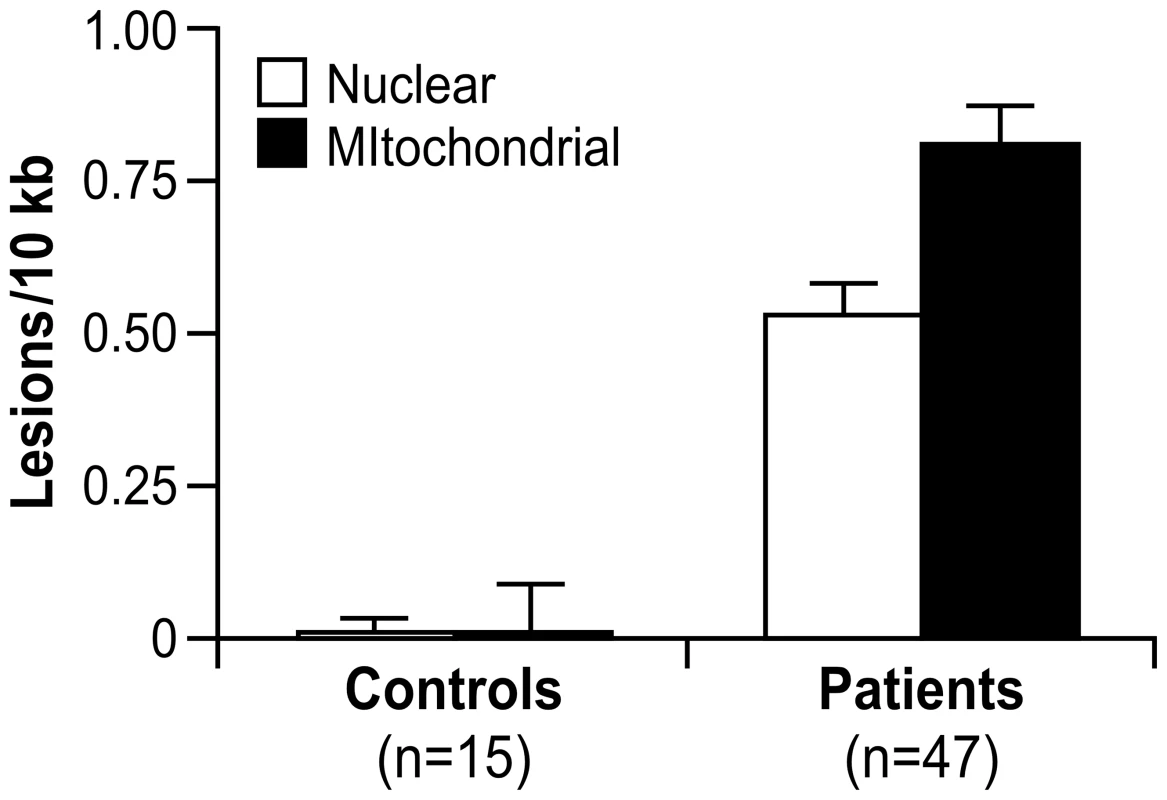

A significant number of nuclear (0.53 lesions/10 kb) and mitochondrial DNA lesions (0.81 lesions/10 kb) was observed in the 47 FRDA children compared to 15 young adult controls (Table S6), with p<0.0001, respectively, by Mann Whitney U-test (Figure 3). There was also a significantly higher number of mitochondrial lesions than nuclear lesions (p<0.002, Mann Whitney U), and both mtDNA and nDNA lesions were found to be highly correlated by Spearman's rank test (Rho = 0.700; p<0.0001). Since this study did not have age-matched control children, for the two DNA damage variables (nDNA and mtDNA), we used a t-test to detect any association with age in the control group. This analysis was performed in the controls after stratifying the subjects as “higher” or “lower” than the median age of the group. Age was not found to be associated with mtDNA damage (p = 0.98) or nDNA damage (p = 0.10).

Fig. 3. Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA damage are identified by QPCR analysis of blood DNA from 47 patients with FRDA and 15 controls.

These data represent the number of excess lesions found per 10 kb of DNA from both mtDNA and nDNA genomes in FRDA patients as compared to the controls. A significant number of nuclear (0.53 lesions/10 kb) and mitochondrial DNA lesions (0.81 lesions/10 kb) were observed (p<0.0001, respectively, by Mann-Whitney U test). There is a significantly higher number of mitochondrial lesions than nuclear lesions (p<0.002 by Mann-Whitney U test), and both types of lesions are highly correlated (p<0.0001 by Spearman's Rank Correlation). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Finally, mtDNA and nDNA damage samples were classified as “high damage” or “low damage” if the lesions/10 kb of DNA was >0.85 or <0.85 (based on the distribution pattern; data not shown), respectively. GSA was then used to test the association of the DNA damage to predefined gene sets. A positive score would indicate enrichment in samples with high DNA lesions/10 kb, and a negative score would point to enrichment in samples with less lesions/10 kb. This analysis showed higher levels of DNA lesions associating to gene sets involving neuronal and synapse formation, as well as several others regarding a genotoxic stress response (p≤0.01) (Dataset S6).

Extracting gene expression patterns identifies potential biomarkers of disease progression

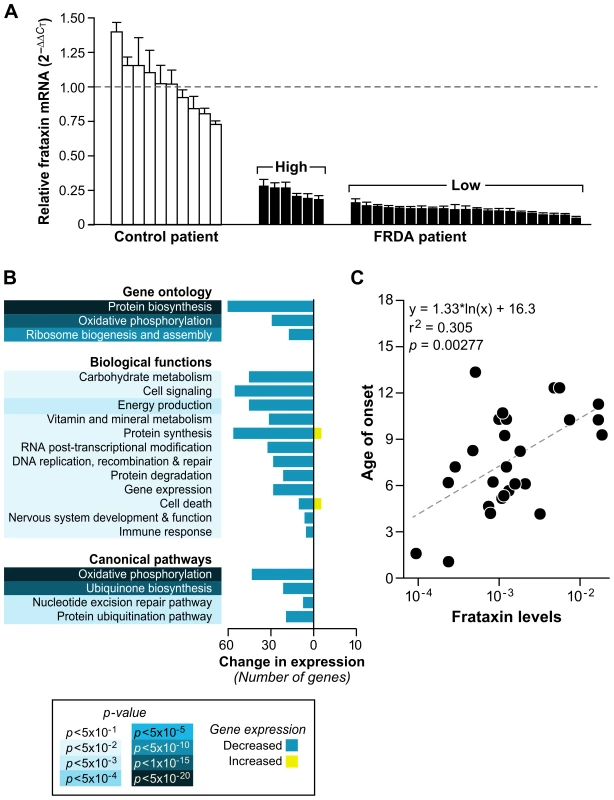

Since the bioinformatics analyses in this study were applied to SAM-derived data based on pooling the raw data from all 28 children (Materials and Methods), we tested the hypothesis that a discrete set of genes would be differentially expressed in patients with the lowest levels of frataxin. We next generated a transcription profile comparing patients with the lowest amount of frataxin, analyzed by Real-time PCR, to those with the highest. The samples were stratified into two groups, based on the expression distribution, where the values formed two distinct modes (see Figure S1 legend). A threshold of −2.5 was selected to separate these two modes, resulting in six patients considered “high-frataxin expressers” and 21 patients designated “low-frataxin expressers” (Figure 4A and Figure S1). Significant gene changes were determined using SAM at a cutoff of FDR≤8% (p≤0.05) for a total of 973 genes. These genes were analyzed for gene ontology enrichment and mapped to pathways in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base. Top scoring categories and pathways included protein biosynthesis, oxidative phosphorylation, ubiquinone biosynthesis, nucleotide excision repair, and protein ubiquitination, all of which were downregulated in those patients expressing lower levels of frataxin (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4. Patients with lower levels of frataxin correlate with age of onset of disease and have more compromised mitochondrial and protein biosynthetic function.

(A) Real-time PCR of frataxin levels in all patients with available RNA (27) were compared to controls (10). Levels of frataxin are relative to the average ΔCT of the controls (dotted line). The error bars represent standard deviations. Brackets encompass the patients stratified by their expression distribution into those expressing higher levels of frataxin (n = 6) and those expressing lower levels of frataxin (n = 21) (see Figure S1). (B) Global gene expression changes were analyzed in the patients with low levels of frataxin vs. patients with high levels of frataxin. Significantly differentially expressed genes (SAM FDR≤8%; p≤0.05; n = 973) were further examined for gene ontology groups categorized by biological process. The same list of genes was analyzed with IPA (Ingenuity Systems), which identified significant biological functions and canonical pathways. All gene groups contain mostly downregulated genes, indicating compromised mitochondrial and biosynthetic function in patients with the lowest expression of frataxin. (C) Age of onset plotted against the Real-time PCR frataxin levels yields a correlation of r2 = 0.305 (p = 0.00277). Since we had quantified the level of frataxin for each patient, we sought to find an association of these levels to the expression of each gene in our genotoxic signaling list (Dataset S3). A univariate linear model was constructed to test this association, and no genes in this set were found to be significantly associated with frataxin levels. The minimum p-value was 0.002, which was not significant after multiple testing correction (q = 0.20). We further sought to find correlations of frataxin mRNA levels to all available clinical data for each child, including DNA lesions and disease duration, but only found an association, by univariate linear modeling, with age of onset and number of short GAA repeats. This resulted in p = 0.00277 and r2 = 0.305 for the relationship of frataxin mRNA levels to age of onset (Figure 4C), and p = 0.00131 (r2 = 0.344) for the relationship of frataxin mRNA levels with the short GAA repeat length (Figure S2). These correlations of frataxin mRNA to short GAA repeat length and age of onset are in agreement with other published studies [1],[40],[41].

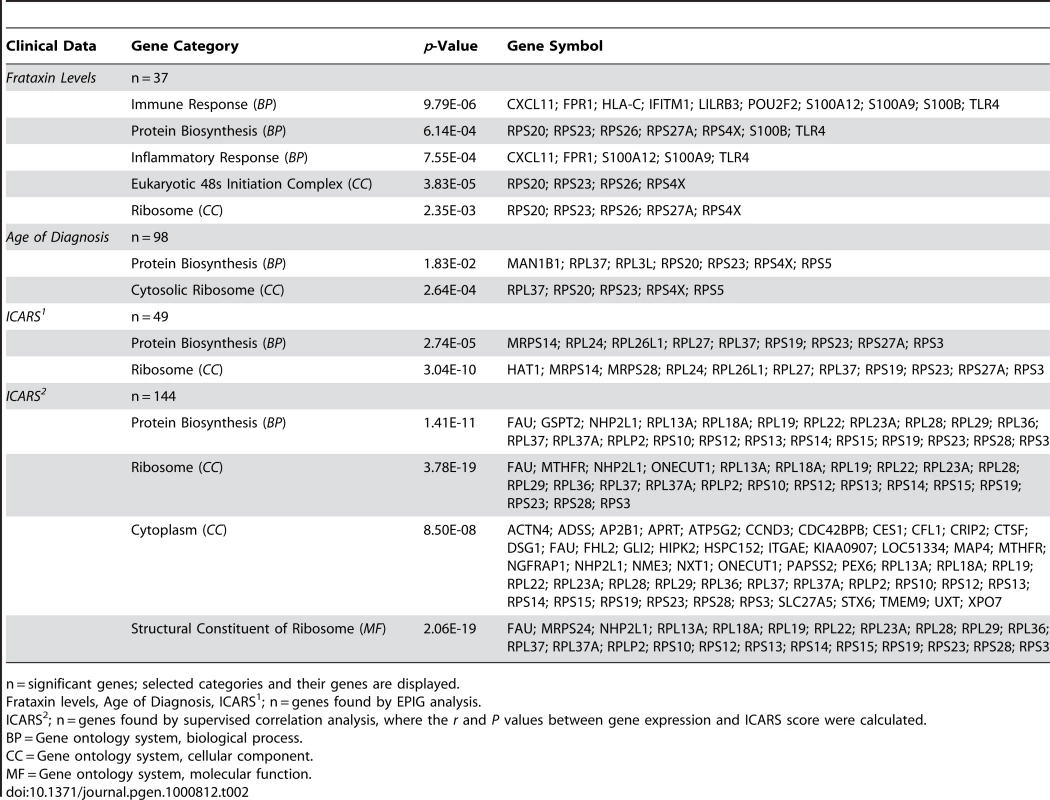

Intrigued by these associations to clinical data, we wondered if we could directly associate the global gene expression data to all clinical data and decided to use a method called EPIG, which extracts microarray gene expression patterns and identifies co-expressed genes (see Materials and Methods) [42]. Indeed, not only did we validate the SAM gene lists for the FRDA children, but we extracted patterns that associated the mostly downregulated transcriptional changes to their frataxin levels, age of diagnosis, and International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale scores – a scoring method used to discern the level of disability in the FRDA patient (Table 2) [43]. Patterns correlating levels of frataxin to gene expression encompassed 37 responsive genes. These genes were grouped most strongly in the GO categories of immune response and protein biosynthesis. Patient age of diagnosis and ICARS score associated with 98 and 48 genes, respectively, with protein biosynthesis as a highly significant category. Supervised correlation analysis was also performed, where correlation r values and p-values between each gene expression profile and ICARS score were calculated. This analysis generated a list of 144 positively and negatively correlated genes at a p-value threshold of 0.01. Protein biosynthetic function was once again highly significant as a GO category, resulting from the input of these genes (Table 2). Genes correlated with ICARS are potential biomarker candidates that may help to classify the progression of the disease.

Tab. 2. Potential biomarkers of FRDA: gene associations to clinical data based on differential expression.

n = significant genes; selected categories and their genes are displayed. Analysis of the second patient cohort shows consistent alterations in gene expression with FRDA children

EPIG was further utilized to extract patterns and compare between the FRDA children and FRDA adults. We were interested in finding biomarker gene candidates based on duration of disease and representative of severity. Of particular interest were genes that were very significant in both cohorts, regulated in the same direction, but displaying larger differential expression in the adults. A detailed examination of the gene profiles was employed using the signal to noise ratio, ANOVA, Student's t-test, and fold changes, and resulted in fifteen genes that are potential biomarkers of disease progression in need of further testing: SERPINC1 (462), DHFRL1 (200895), IRX2 (153572), SGCE (8910), ADAM23 (8745), TBX3 (6926), SLC5A4 (6527), CCAR1 (55749), MS4A2 (2206), IMPACT (55364), NDUFA5 (4698), CEACAM6 (4680), C10orf88 (80007), ITGA4 (3676), and CD69 (969) (first seven genes are upregulated and the subsequent eight genes are downregulated). Entrez IDs for these genes and all genes described in this paper can be found in Table S7.

Discussion

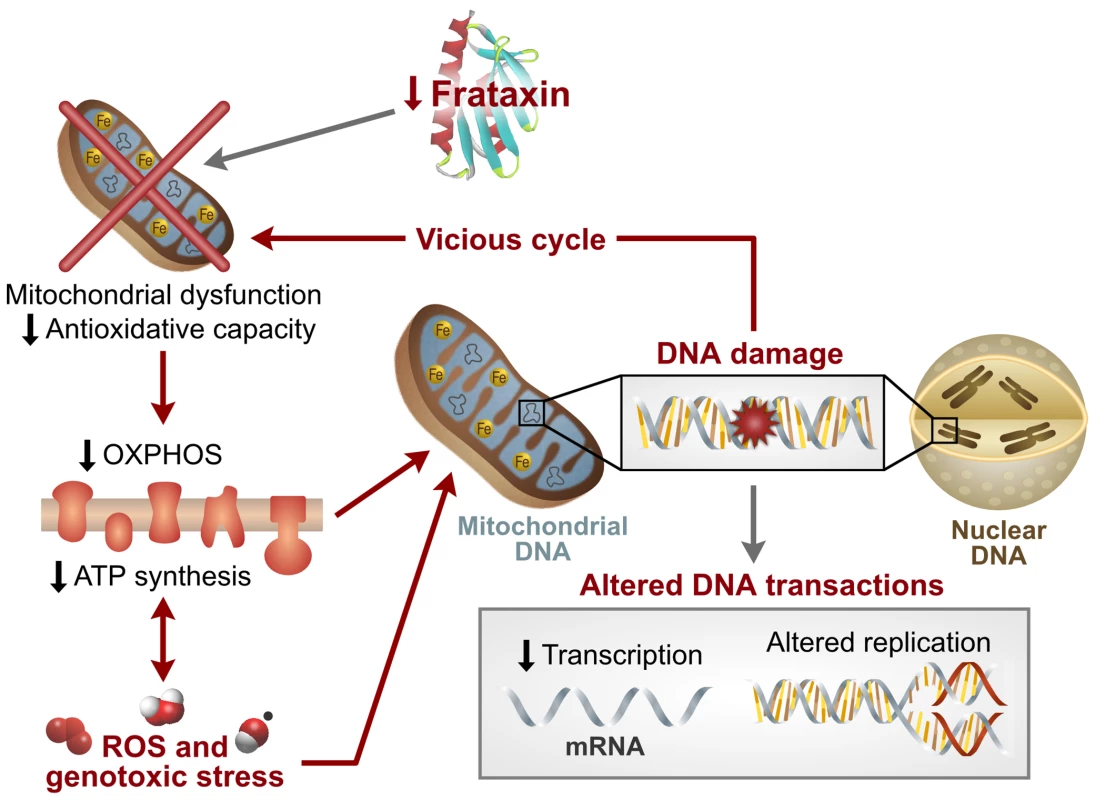

This study provides the first summary of gene expression changes in the blood of 28 children with Friedreich's ataxia and the association of this global response to the nuclear and mitochondrial DNA damage found in 47 children (including the 28 children from the gene expression analysis). These data – the 23 gene sets associated to a genotoxic stress response and the direct biological evidence of mtDNA and nDNA damage in the blood – result in a working model of the disease, where repressed levels of frataxin create a vicious cycle of mitochondrial dysfunction (probably due to ISC biosynthesis impairment), decreased oxidative phosphorylation, and increased reactive oxygen species production and genotoxic stress (Figure 5). These events result in DNA damage and altered DNA transactions, which likely contribute to the decreased protein biosynthesis, signaling, transcription, DNA replication/recombination/repair, apoptosis, and ubiquitination, as well as the altered immune response and proliferation indicated in the transcription profiling. Such changes in the blood may relate to the clinical manifestations of neurodegenerative and cardiovascular disease in FRDA patients, while also providing biomarker candidates for their disease.

Fig. 5. Model of Friedreich's ataxia pathology based on this study.

Data presented in this study are consistent with a dysregulation of mitochondrial function, decreased oxidative phosphorylation, increased ROS production, and subsequent mitochondrial and nuclear DNA damage. These factors contribute to decreased signaling and altered DNA transactions, which are likely to result in subsequent loss of protein synthesis and decreased protein degradation, as suggested in the transcription profiling. These alterations may cause tissue damage, altered immune response, and the clinical pathology associated with FRDA. Gene expression changes in peripheral blood of FRDA patients compared to lymphoblastoid cell lines

Cortopassi and coworkers have previously published two global gene expression analyses of cells from FRDA patients [25] and tissue from frataxin-KO mice (26). While direct analyses of these published studies with the work presented here is not possible, since these previous data were not apparently deposited in a public database, several points are worth noting. Tan et al. [25] reported 48 significant frataxin-dependent differentially expressed genes in at least two of the human cell types. In particular, they focused on seven downregulated transcripts belonging to the sulfur amino acid (SAA) and iron-sulfur cluster biosynthetic pathways. When they combined data from mouse and human frataxin-deficient cells and tissues, mitochondrial coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CPOX; 1371), which is involved in the heme pathway, and the homologue of yeast COX23 (856516) were most consistently downregulated [27]. These transcripts were not found to be significant in our dataset. The authors conclude that frataxin deficiency leads to heme deficiency. While our work with both FRDA patient cohorts did not show the heme pathway as significantly repressed, the downregulated mitochondrial pathways we did observe are easily affected by, or could contribute to, heme deficiency. Ultimately, these changes in heme biosynthesis could cause DNA damage [44] recapitulated in our patients.

We wanted to further validate the datasets derived from children and adults with FRDA, so we analyzed ten FRDA lymphoblastoid cell lines, compared with seven age-matched controls, and data from a previous report involving two lymphoblastoid cell lines (one control and one affected) (Table S8) [45]. Particularly interesting overlaps with the blood data were observed with GSA analysis, which also yielded significant gene sets related to genotoxic stress response (for biologically informative sets in common between the FRDA children's data and the lymphoblastoid data, see Dataset S7 and Figure S3). Furthermore, GSA analysis of the lymphoblastoid data also found an association to significant gene sets like electron_transport_chain, mitochondrion, and ubiquinone biosynthesis, which are indicative of the mitochondrial dysfunction expected in frataxin-deficient cells (Dataset S7).

Consequences of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA damage in FRDA patients

While the QPCR assay used in this study cannot directly identify the type of DNA damage inhibiting the progression of the thermostable polymerase, the increase in mtDNA damage, as compared to nDNA damage, is consistent with a large number of studies from our and other laboratories, indicating that mtDNA is more prone to oxidative stress [16], [34]–[37]. The increased DNA damage observed in the children suggests oxidant injury in their blood cells, probably caused by an increase in bioavailable iron in the mitochondria. Persistent mtDNA damage in FRDA patients could impair mitochondrial function. Experiments with mammalian cell cultures, treated with hydrogen peroxide, indicate that relentless mtDNA damage decreases oxidative phosphorylation and ATP production (unpublished observation). In vivo evidence of impaired mitochondrial ATP production has, in fact, been seen in the muscle of FRDA patients [46],[47] and in KO mice [48]. Karthikeyan et al. [16] also demonstrate how yeast strains with reduced frataxin accumulate mitochondrial iron and generate reactive hydroxyl radicals, which damage cell membranes, proteins, and mitochondrial DNA, resulting in the decreased capacity for ATP synthesis through impaired oxidative phosphorylation. The same study further demonstrates how low levels of frataxin in a RAD52 double-strand break repair deficient yeast strain lead to rapid G2/M cell cycle arrest, which is consistent with nuclear damage. Moreover, reports depicting an increased sensitivity to gamma irradiation in FRDA skin fibroblasts, and the induction of chromosomal damage by mutagens in blood lymphocytes, support a hypothesis of increased susceptibility and/or altered DNA repair capacity in these patients [49],[50].

The eukaryotic cell, in response to DNA damage, employs different strategies for damage recognition and repair in order to maintain the integrity of the genome. DNA damage sensors such as ATM (472) and p53 are crucial in detecting double-strand breaks and general DNA damage responses, respectively [51]. Although the ATM and p53 genes are not differentially expressed in the datasets presented here, we observed, via GSA and the Ingenuity Knowledge Base (data not shown), that many interacting network partners of these two proteins are significantly altered.

The significant increase in persistent DNA damage we found in FRDA patients, as well as the transcription profiling results, indicate altered repair capacity and altered apoptosis signaling events. Furthermore, a significant number of genes included in the Ingenuity biological function category of Cancer (104 and 475 genes in Cancer and its subcategories, p≤0.05, for FRDA children and FRDA adults, respectively; data not shown) may explain the malignant transformation potential of frataxin-deficient cells, both in vitro and in vivo [10],[48],[52]. This hypothesis is supported by work done in mice by Thierbach et al. [48], albeit a mouse model completely deleted for frataxin. When they disrupted expression of frataxin in mouse hepatocytes, lifespan was not only reduced, but the livers had increased oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. This was paralleled by reduced activity of iron-sulfur cluster containing proteins and the development of multiple hepatic tumors. The authors also reported impaired phosphorylation of the stress-inducible p38 MAP kinase and suggest that frataxin may, in fact, be a mitochondrial tumor suppressor protein. Thus, while reports of cancer in FRDA patients are rare [53]–[56], the incidence may be underestimated due to premature mortality of these patients in early adulthood.

The overall decrease in transcription and DNA damage we observed are likely consequences of dysfunctional ISC biosynthesis and reduced activity of proteins containing iron-sulfur centers. In fact, several damage recognition and DNA repair proteins are iron-sulfur containing and could be directly linked to the DNA damage described [57]–[60]. Currently, we are analyzing protein levels, in frataxin-deficient cell lines, of a panel of iron-sulfur containing proteins important to DNA repair. Some candidate proteins with iron-sulfur centers include the MutY (4595) homologue (a glycosylase in base excision repair); the yeast protein, Rad3 (856918), which is essential for viability, and its human homologues XPD (2068) and Fancj (83990) (helicases involved in nucleotide excision repair and the Fanconi anemia repair pathway, respectively); and Pri2 (853821) (essential to RNA primer synthesis) [57]–[60].

The likely sequence of events leading to the DNA damage we observed are as follows: 1) deficiency of frataxin generates a defect in ISC assembly and biogenesis [5], [12]–[14]; 2) the dysfunction of biosynthesis of mitochondrial iron-sulfur clusters, and deficient ISC enzyme activity, produces a defect in heme and a lack of cytochrome C [12]; 3) impairment of electron transport activity, which is dependent on iron-sulfur biogenesis, and the decrease in cytochrome C, results in higher levels of ROS production [12],[14]; and 4) due to lack in antioxidative capacity, which we explain below, eventual DNA damage occurs. Therefore, we believe the DNA damage in the blood of the Friedreich's ataxia patient is a secondary event to the primary one of frataxin depletion and neurodegeneration. However, the secondary event of cellular oxidative stress and DNA damage is a significant component to the underlying pathology of the disease.

Adaptation to chronic stress

We further propose that the downregulation of many key pathways (Figure S4A and Figure 4C) and GO categories (Figure 1, Figure 2C, and Figure 4B), in this study, may suggest a systemic survival response to chronic genotoxic stress and consequent DNA damage. Chronic genotoxic stress in FRDA probably results from iron accumulation in the mitochondria, and it might be expected that cellular redox homeostasis, such as that regulated by NRF2 (4780), would protect the cell from excessive reactive oxygen metabolites. However, we observed the downregulation of the NRF2-mediated oxidative stress pathway (Figure S4B), strengthening published reports suggesting a disabled antioxidant defense response in FRDA [9],[10],[61], including a recent study by Paupe et al. [62] showing that cultured fibroblasts from patients with FRDA exhibit hypersensitivity to oxidative stress because of an impaired NRF2 signaling pathway. Furthermore, Chantrel-Groussard et al. [9] found that reduced frataxin does not induce superoxide dismutases nor the import iron machinery by endogenous oxidative stress in FRDA fibroblasts compared to controls. Superoxide dismutase activity is also not induced in the heart of conditional knock-out mice [21]. Conversely, overexpression of human frataxin in murine cells increases antioxidant defense via activation of glutathione peroxidase and elevation of reduced thiols, and reduces the incidence of ROS-induced malignant transformation [10]. Sturm et al. [61] reported data strongly indicating that a reduction in frataxin does not affect the mitochondrial labile iron pool in human cell lines and suggests that these cells have a decreased antioxidative capacity. Overall, these studies support a mechanism by which iron-sulfur proteins are lost [13] and there are increased amounts of ROS and a disabled antioxidant defense system.

Based on our blood analysis of FDRA patients showing chronic genotoxic stress responses and chronic DNA damage, we believe these stressors cause a genetic reprogramming of fundamental biological pathways as a protective survival response. A similar idea was reported by Niedernhofer et al., [63] who analyzed a case of XPF/ERCC1 (2072/2067) progeroid syndrome and a knockout mouse model of this disease. They concluded that chronic DNA damage causes cells to deemphasize growth activities in order to ensure organismal preservation and maximal lifespan, despite an increase in cellular senescence and apoptosis.

The level of injury in the cells of these patients is not only exacerbated by the loss of antioxidative defense, but also by the downregulation of oxidative phosphorylation and the shutdown of protein synthesis and translation, as was observed in the gene expression analysis of patients with lower levels of frataxin as compared to patients with higher levels. EPIG analysis further demonstrated a marked decrease in genes involved in protein synthesis, and genes encoding ribosomal proteins, correlating with frataxin levels, age of diagnosis, and ICARS scores. Many of the significant genes involved in the category of protein synthesis include the repression of several initiation factors. Paschen et al. [64] discuss how such events suggest the relationship between the shutdown of translation and induction of neuronal cell death. It is our hypothesis that such global responses are triggered by chronic stress.

We also found interesting the effect frataxin deficiency has on ubiquitin cycle and protein degradation in both FRDA children and FRDA adults. Modifications to the function of ubiquitinating enzymes by oxidative stress have been reported [4]. Degradation of damaged proteins by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is one of the most important processes in the cell, and a decreased capacity for protein degradation is related to several neurodegenerative diseases and pathologies of the inflammatory immune response [65],[66].

In summary, this study provides the first evidence of increased mitochondrial and nuclear DNA damage, as well as gene expression patterns consistent with DNA damage, in peripheral blood cells of patients with FRDA. Analyses of clinical features and gene expression patterns correlate with age of onset and frataxin mRNA levels, as well as altered protein synthesis with frataxin levels, ICARS score, and age of diagnosis. Future studies with Friedreich's ataxia patients will help better define these gene sets and DNA damage as candidate biomarkers of disease severity and progression. Additionally, biomarkers are vital to the development of therapeutic approaches, and our study points to possible drug interventions, like modulating the ubiquitin-proteasome system or upregulating molecular chaperone activity, which may be as useful for FRDA as they are in other neurodegenerative diseases. However, the development of effective therapeutic approaches also depends on an enhanced understanding of signaling pathways and other cellular responses to chronic genotoxic stress.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

Peripheral blood samples were collected from 48 children with FRDA participating in a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial for idebenone [registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00229632, and approved by the NIH Institutional Review Board at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), protocol # 05-N-0245]. Samples from 14 anonymous FRDA adults were collected in the reference center clinic dedicated to cerebellar ataxias and aspartic paraplegias at the University Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris; samples were exempted by the NIH Institutional Review Board at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), exempt # 3984. All controls used for transcriptional profiling were young healthy adults from an acetaminophen study [28], approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, protocol # GCRC-2265. Controls used for the DNA damage assay were obtained from an NIH blood bank. Blood and/or apheresis samples were obtained from healthy volunteer donors who gave signed consent to participate in an IRB-approved protocol for use of their blood in laboratory research studies; these samples were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), protocol # 99-CC-0168.

RNA isolation from blood

Peripheral blood samples were collected from 48 children with FRDA participating in a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. All whole blood samples in this study were collected before administration of idebenone. A detailed description of all subjects and clinical endpoints was recently published [22]. Due to other endpoints, this study only allotted one 8.5 ml sample of blood from each patient for RNA isolation. RNA was isolated by one person, utilizing the PAXgene blood RNA isolation kit (PreAnalytiX/QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol, including the optional on-column DNase digestion, except that the centrifugation time after proteinase K digestion was increased from 3 to 20 minutes in order to obtain a tighter debris pellet. RNA quality was assessed with an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Palo Alto, CA) to ensure that samples with intact 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA peaks were used for microarray analysis. Of the 48 patients, twenty samples were lost during the isolation procedures, leaving 28 high-quality RNA samples remaining. The demographics for these subjects are detailed in Table S1. RNA was also isolated, using the same methods already described, from 14 anonymous FRDA adults (Table S2). All controls used were young healthy adults (see demographics data in Table S1 and Table S2) from an acetaminophen study [28]. Two independent sets of control populations were used separately to compare to the children and the adult validation cohort.

Gene profiling

Gene expression profiling was conducted using Agilent Human 1A(V2) Oligo arrays with ∼20,000 genes represented (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Each sample was hybridized against a human universal RNA control (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). 500 ng of total RNA was amplified and labeled using the Agilent Low RNA Input Fluorescent Linear Amplification Kit, according to manufacturer's protocol. For each two color comparison, 750 ng of each Cy3 - (universal control) and Cy5-labeled (sample) cRNA were mixed and fragmented using the Agilent In Situ Hybridization Kit protocol. Hybridizations were performed for 17 hours in a rotating hybridization oven according to the Agilent 60-mer oligo microarray processing protocol prior to washing and scanning with an Agilent Scanner (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE). The data were obtained with the Agilent Feature Extraction software (v9.1), using defaults for all parameters. The Feature Extraction Software performs error modeling before data are loaded into a database system. Images and GEML files, including error and p-values, were exported from the Agilent Feature Extraction software and deposited into Rosetta Resolver (version 5.0, build 5.0.0.2.48) (Rosetta Biosoftware, Kirkland, WA). All gene expression data have been deposited in the public Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database and are available under the series ID GSE11204.

Statistical and data analyses

Supervised analysis to find genes associated with case versus control or low frataxin expression versus high expression was performed using Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) after pooling the raw data [29]. The two-class unpaired SAM algorithm was used and the false discovery rate was set to less than or equal to 1% for all analyses. Gene Set Analysis (GSA) [30] was also performed for these comparisons to test the association of gene sets instead of individual genes. The database of gene sets used for GSA was obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDb) [30]. Gene sets demonstrating a p-value less than 0.01 were considered significant.

Biologically relevant themes in the lists of significant genes from SAM were analyzed with gene ontology tools, GoMiner and DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery) [67],[68]. GO terms with p≤0.05 for upregulated, downregulated, and/or combined direction of change were selected for analysis. Both tools group genes according to the GO categories of biological process, cellular component, and molecular function, based on ranking by a hypergeometric test p-value. These data were also uploaded into Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software v 5.5.1 (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA), a program that categorizes genes into biological functions but also enables visualization of biologically relevant networks and canonical pathways (“canonical” implies “established”). Go to www.Ingenuity.com for specifics regarding the application. Unsupervised clustering and heat-map generation were carried out with Cluster and Treeview programs [69].

The levels of DNA damage were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test or Spearman's Rank Correlation because the data is not normally distributed or homoskedastic.

In order to test association between gene expression and age, we used SAM. For the two DNA damage variables we used a Student's t-test to detect association with age. All these analyses were performed in the controls, and age was dichotomized by comparison to the median age of the controls.

A univariate linear model was constructed to test the association of each gene in the genotoxic gene set list (genes found in 25% of gene lists from significant gene sets) to patient frataxin levels (determined by Real-time PCR). Correlations of frataxin mRNA levels to all available clinical data for each child were also performed by univariate linear modeling.

In extracting gene expression patterns, EPIG [42] uses a filtering process where all profiles initially are considered as pattern candidates. Briefly, using all pair-wise correlations, any candidate profile, whose local cluster size is less than a predefined size Mt or its correlation with another profile is higher (>Rt) but has a lower local cluster size M, is removed from pattern construction consideration. Among the remaining profiles, EPIG then creates representative profiles for the corresponding local clusters and removes those profiles with a signal-to-noise ratio or magnitude less than given thresholds. After this filtering processing, the remaining profiles consist of the extracted patterns, which are used to be the representatives to each of the local clusters. Subsequently, EPIG categorizes each significant gene to a pattern, for which it has the highest correlation with the gene profile. A gene not assigned to any extracted pattern is considered an “orphan” if its highest correlation r-value is lower than the given threshold R.

TaqMan real-time PCR

The frataxin probe on the Agilent chip was observed to lack sensitivity for both the individual lymphoblastoid cell lines from affected people (data not shown) and the whole blood from FRDA patients. We, therefore, decided to obtain relative gene expression levels of frataxin by TaqMan Real-time PCR [70]. The sequence information of the probe used for TaqMan is the proprietary information of PE Applied Biosystems, but we know it is 75 nucleotides that span across the exon 1 and exon 2 boundary. On the other hand, the probe on the microarray chip is mostly from the 3′ UTR of frataxin.

One microgram of total RNA from 27 patients and 10 controls was used for reverse transcription with TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents (PE Applied Biosystems). To determine relative frataxin mRNA levels, Real-time PCR was carried out using the ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system. Primer and probe sets for frataxin and glucuronidase-beta were purchased as pre-developed assays from PE Applied Biosystems. Relative quantification was obtained using the threshold cycle method after verification of primer performance, following the manufacturer's guidelines. The levels of frataxin obtained are relative to the average ΔCT from 10 controls.

Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA quantitative PCR assay

Total DNA from whole blood was successfully isolated from 47 children enrolled in the study and 15 adult controls obtained from an NIH blood bank in Bethesda, MD, (Table S6) using the PAXgene blood DNA isolation kit (PreAnalytiX/QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, one 8.5 ml sample of whole blood, per child, was collected in PAXgene blood DNA tubes for DNA isolation; each blood sample was transferred to a processing tube containing a lysing solution. Lysed red and white blood cells were centrifuged, and the resulting pellet of nuclei and mitochondria was washed and resuspended. After digestion with protease, DNA was precipitated by addition of isopropanol and dissolved in water. All DNA samples were prepared by one person. DNA lesion frequencies were calculated as described previously [33]. Briefly, the amplification of patient samples (Apatient) was compared to the amplification of non-damaged controls (Acontrol) resulting in a relative amplification ratio. Assuming a random distribution of lesions and using the Poisson equation [f(x) = .e ˜−λ λx/x!, where λ is the average lesion frequency for the nondamaged template (i.e., the zero class; x = 0)], the average lesion per DNA strand was determined by the following equation: .λ = .−ln APatient/Acontrol. Amplification of the large mitochondrial target was normalized to mitochondrial copy number by examination of a short mitochondrial target, which due to its short size, should be free of damage.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. CampuzanoV

MonterminiL

LutzY

CovaL

HindelangC

1997 Frataxin is reduced in Friedreich ataxia patients and is associated with mitochondrial membranes. Hum Mol Genet 6 1771 1780

2. CampuzanoV

MonterminiL

MoltoMD

PianeseL

CosseeM

1996 Friedreich's ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science 271 1423 1427

3. OhshimaK

MonterminiL

WellsRD

PandolfoM

1998 Inhibitory effects of expanded GAA.TTC triplet repeats from intron I of the Friedreich ataxia gene on transcription and replication in vivo. J Biol Chem 273 14588 14595

4. BidichandaniSI

AshizawaT

PatelPI

1998 The GAA triplet-repeat expansion in Friedreich ataxia interferes with transcription and may be associated with an unusual DNA structure. Am J Hum Genet 62 111 121

5. MuhlenhoffU

RichhardtN

RistowM

KispalG

LillR

2002 The yeast frataxin homolog Yfh1p plays a specific role in the maturation of cellular Fe/S proteins. Hum Mol Genet 11 2025 2036

6. StehlingO

ElsasserHP

BruckelB

MuhlenhoffU

LillR

2004 Iron-sulfur protein maturation in human cells: evidence for a function of frataxin. Hum Mol Genet 13 3007 3015

7. SchulzJB

DehmerT

ScholsL

MendeH

HardtC

2000 Oxidative stress in patients with Friedreich ataxia. Neurology 55 1719 1721

8. WongA

YangJ

CavadiniP

GelleraC

LonnerdalB

1999 The Friedreich's ataxia mutation confers cellular sensitivity to oxidant stress which is rescued by chelators of iron and calcium and inhibitors of apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet 8 425 430

9. Chantrel-GroussardK

GeromelV

PuccioH

KoenigM

MunnichA

2001 Disabled early recruitment of antioxidant defenses in Friedreich's ataxia. Hum Mol Genet 10 2061 2067

10. ShoichetSA

BaumerAT

StamenkovicD

SauerH

PfeifferAF

2002 Frataxin promotes antioxidant defense in a thiol-dependent manner resulting in diminished malignant transformation in vitro. Hum Mol Genet 11 815 821

11. GakhO

ParkS

LiuG

MacomberL

ImlayJA

2006 Mitochondrial iron detoxification is a primary function of frataxin that limits oxidative damage and preserves cell longevity. Hum Mol Genet 15 467 479

12. NapoliE

TaroniF

CortopassiGA

2006 Frataxin, iron-sulfur clusters, heme, ROS, and aging. Antioxid Redox Signal 8 506 516

13. PuccioH

SimonD

CosseeM

Criqui-FilipeP

TizianoF

2001 Mouse models for Friedreich ataxia exhibit cardiomyopathy, sensory nerve defect and Fe-S enzyme deficiency followed by intramitochondrial iron deposits. Nat Genet 27 181 186

14. CalabreseV

LodiR

TononC

D'AgataV

SapienzaM

2005 Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular stress response in Friedreich's ataxia. J Neurol Sci 233 145 162

15. FouryF

CazzaliniO

1997 Deletion of the yeast homologue of the human gene associated with Friedreich's ataxia elicits iron accumulation in mitochondria. FEBS Lett 411 373 377

16. KarthikeyanG

SantosJH

GraziewiczMA

CopelandWC

IsayaG

2003 Reduction in frataxin causes progressive accumulation of mitochondrial damage. Hum Mol Genet 12 3331 3342

17. LamarcheJB

CoteM

LemieuxB

1980 The cardiomyopathy of Friedreich's ataxia morphological observations in 3 cases. Can J Neurol Sci 7 389 396

18. WaldvogelD

van GelderenP

HallettM

1999 Increased iron in the dentate nucleus of patients with Friedrich's ataxia. Ann Neurol 46 123 125

19. EmondM

LepageG

VanasseM

PandolfoM

2000 Increased levels of plasma malondialdehyde in Friedreich ataxia. Neurology 55 1752 1753

20. BradleyJL

HomayounS

HartPE

SchapiraAH

CooperJM

2004 Role of oxidative damage in Friedreich's ataxia. Neurochem Res 29 561 567

21. SeznecH

SimonD

BoutonC

ReutenauerL

HertzogA

2005 Friedreich ataxia: the oxidative stress paradox. Hum Mol Genet 14 463 474

22. Di ProsperoNA

BakerA

JeffriesN

FischbeckKH

2007 Neurological effects of high-dose idebenone in patients with Friedreich's ataxia: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 6 878 886

23. MyersLM

LynchDR

FarmerJM

FriedmanLS

LawsonJA

2008 Urinary isoprostanes in Friedreich ataxia: lack of correlation with disease features. Mov Disord 23 1920 1922

24. MichaelS

PetrocineSV

QianJ

LamarcheJB

KnutsonMD

2006 Iron and iron-responsive proteins in the cardiomyopathy of Friedreich's ataxia. Cerebellum 5 257 267

25. TanG

NapoliE

TaroniF

CortopassiG

2003 Decreased expression of genes involved in sulfur amino acid metabolism in frataxin-deficient cells. Hum Mol Genet 12 1699 1711

26. CoppolaG

ChoiSH

SantosMM

MirandaCJ

TentlerD

2006 Gene expression profiling in frataxin deficient mice: microarray evidence for significant expression changes without detectable neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis 22 302 311

27. SchoenfeldRA

NapoliE

WongA

ZhanS

ReutenauerL

2005 Frataxin deficiency alters heme pathway transcripts and decreases mitochondrial heme metabolites in mammalian cells. Hum Mol Genet 14 3787 3799

28. HarrillAH

WatkinsPB

SuS

RossPK

HarbourtDE

2009 Mouse population-guided resequencing reveals that variants in CD44 contribute to acetaminophen-induced liver injury in humans. Genome Res

29. TusherVG

TibshiraniR

ChuG

2001 Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 5116 5121

30. EfronB

TibshiraniR

2006 On testing the significance of sets of genes. Tech report 1 32

31. SubramanianA

TamayoP

MoothaVK

MukherjeeS

EbertBL

2005 Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 15545 15550

32. HuT

GibsonDP

CarrGJ

TorontaliSM

TiesmanJP

2004 Identification of a gene expression profile that discriminates indirect-acting genotoxins from direct-acting genotoxins. Mutat Res 549 5 27

33. SantosJH

MeyerJN

MandavilliBS

Van HoutenB

2006 Quantitative PCR-based measurement of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA damage and repair in mammalian cells. Methods Mol Biol 314 183 199

34. YakesFM

Van HoutenB

1997 Mitochondrial DNA damage is more extensive and persists longer than nuclear DNA damage in human cells following oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94 514 519

35. SantosJH

HunakovaL

ChenY

BortnerC

Van HoutenB

2003 Cell sorting experiments link persistent mitochondrial DNA damage with loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and apoptotic cell death. J Biol Chem 278 1728 1734

36. MandavilliBS

BoldoghI

Van HoutenB

2005 3-nitropropionic acid-induced hydrogen peroxide, mitochondrial DNA damage, and cell death are attenuated by Bcl-2 overexpression in PC12 cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 133 215 223

37. MandavilliBS

AliSF

Van HoutenB

2000 DNA damage in brain mitochondria caused by aging and MPTP treatment. Brain Res 885 45 52

38. SalazarJJ

Van HoutenB

1997 Preferential mitochondrial DNA injury caused by glucose oxidase as a steady generator of hydrogen peroxide in human fibroblasts. Mutat Res 385 139 149

39. Van HoutenB

ChengS

ChenY

2000 Measuring gene-specific nucleotide excision repair in human cells using quantitative amplification of long targets from nanogram quantities of DNA. Mutat Res 460 81 94

40. FillaA

De MicheleG

CavalcantiF

PianeseL

MonticelliA

1996 The relationship between trinucleotide (GAA) repeat length and clinical features in Friedreich ataxia. Am J Hum Genet 59 554 560

41. PianeseL

TuranoM

Lo CasaleMS

De BiaseI

GiacchettiM

2004 Real time PCR quantification of frataxin mRNA in the peripheral blood leucocytes of Friedreich ataxia patients and carriers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 75 1061 1063

42. ChouJW

ZhouT

KaufmannWK

PaulesRS

BushelPR

2007 Extracting gene expression patterns and identifying co-expressed genes from microarray data reveals biologically responsive processes. BMC Bioinformatics 8 427

43. TrouillasP

TakayanagiT

HallettM

CurrierRD

SubramonySH

1997 International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale for pharmacological assessment of the cerebellar syndrome. The Ataxia Neuropharmacology Committee of the World Federation of Neurology. J Neurol Sci 145 205 211

44. OnukiJ

ChenY

TeixeiraPC

SchumacherRI

MedeirosMH

2004 Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA damage induced by 5-aminolevulinic acid. Arch Biochem Biophys 432 178 187

45. BurnettR

MelanderC

PuckettJW

SonLS

WellsRD

2006 DNA sequence-specific polyamides alleviate transcription inhibition associated with long GAA.TTC repeats in Friedreich's ataxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 11497 11502

46. LodiR

CooperJM

BradleyJL

MannersD

StylesP

1999 Deficit of in vivo mitochondrial ATP production in patients with Friedreich ataxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 11492 11495

47. VorgerdM

ScholsL

HardtC

RistowM

EpplenJT

2000 Mitochondrial impairment of human muscle in Friedreich ataxia in vivo. Neuromuscul Disord 10 430 435

48. ThierbachR

SchulzTJ

IskenF

VoigtA

MietznerB

2005 Targeted disruption of hepatic frataxin expression causes impaired mitochondrial function, decreased life span and tumor growth in mice. Hum Mol Genet 14 3857 3864

49. LewisPD

CorrJB

ArlettCF

HarcourtSA

1979 Increased sensitivity to gamma irradiation of skin fibroblasts in Friedreich's ataxia. Lancet 2 474 475

50. EvansHJ

Vijayalaxmi

PentlandB

NewtonMS

1983 Mutagen hypersensitivity in Friedreich's ataxia. Ann Hum Genet 47 193 204

51. FinkelT

HolbrookNJ

2000 Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature 408 239 247

52. SchulzTJ

ThierbachR

VoigtA

DrewesG

MietznerB

2006 Induction of oxidative metabolism by mitochondrial frataxin inhibits cancer growth: Otto Warburg revisited. J Biol Chem 281 977 981

53. De PasT

MartinelliG

De BraudF

PeccatoriF

CataniaC

1999 Friedreich's ataxia and intrathecal chemotherapy in a patient with lymphoblastic lymphoma. Ann Oncol 10 1393

54. KiddA

ColemanR

WhitefordM

BarronLH

SimpsonSA

2001 Breast cancer in two sisters with Friedreich's ataxia. Eur J Surg Oncol 27 512 514

55. AckroydR

ShorthouseAJ

StephensonTJ

1996 Gastric carcinoma in siblings with Friedreich's ataxia. Eur J Surg Oncol 22 301 303

56. BarrH

PageR

TaylorW

1986 Primary small bowel ganglioneuroblastoma and Friedreich's ataxia. J R Soc Med 79 612 613

57. LillR

MuhlenhoffU

2008 Maturation of iron-sulfur proteins in eukaryotes: mechanisms, connected processes, and diseases. Annu Rev Biochem 77 669 700

58. KlingeS

HirstJ

MamanJD

KrudeT

PellegriniL

2007 An iron-sulfur domain of the eukaryotic primase is essential for RNA primer synthesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14 875 877

59. LukianovaOA

DavidSS

2005 A role for iron-sulfur clusters in DNA repair. Curr Opin Chem Biol 9 145 151

60. RudolfJ

MakrantoniV

IngledewWJ

StarkMJ

WhiteMF

2006 The DNA repair helicases XPD and FancJ have essential iron-sulfur domains. Mol Cell 23 801 808

61. SturmB

BistrichU

SchranzhoferM

SarseroJP

RauenU

2005 Friedreich's ataxia, no changes in mitochondrial labile iron in human lymphoblasts and fibroblasts: a decrease in antioxidative capacity? J Biol Chem 280 6701 6708

62. PaupeV

DassaEP

GoncalvesS

AuchereF

LonnM

2009 Impaired nuclear Nrf2 translocation undermines the oxidative stress response in friedreich ataxia. PLoS ONE 4 e4253

63. NiedernhoferLJ

GarinisGA

RaamsA

LalaiAS

RobinsonAR

2006 A new progeroid syndrome reveals that genotoxic stress suppresses the somatotroph axis. Nature 444 1038 1043

64. PaschenW

ProudCG

MiesG

2007 Shut-down of translation, a global neuronal stress response: mechanisms and pathological relevance. Curr Pharm Des 13 1887 1902

65. MukhopadhyayD

RiezmanH

2007 Proteasome-independent functions of ubiquitin in endocytosis and signaling. Science 315 201 205

66. HerrmannJ

LermanLO

LermanA

2007 Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins in protein regulation. Circ Res 100 1276 1291

67. ZeebergBR

FengW

WangG

WangMD

FojoAT

2003 GoMiner: a resource for biological interpretation of genomic and proteomic data. Genome Biol 4 R28

68. DennisGJr

ShermanBT

HosackDA

YangJ

GaoW

2003 DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol 4 P3

69. EisenMB

SpellmanPT

BrownPO

BotsteinD

1998 Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 14863 14868

70. HeidCA

StevensJ

LivakKJ

WilliamsPM

1996 Real time quantitative PCR. Genome Res 6 986 994

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Activation of Mutant Enzyme Function by Proteasome Inhibitors and Treatments that Induce Hsp70Článek Maternal Ethanol Consumption Alters the Epigenotype and the Phenotype of Offspring in a Mouse ModelČlánek Genetic Dissection of Differential Signaling Threshold Requirements for the Wnt/β-Catenin PathwayČlánek Distinct Type of Transmission Barrier Revealed by Study of Multiple Prion Determinants of Rnq1

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2010 Číslo 1- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Irradiation-Induced Genome Fragmentation Triggers Transposition of a Single Resident Insertion Sequence

- A Major Role of the RecFOR Pathway in DNA Double-Strand-Break Repair through ESDSA in

- Kidney Development in the Absence of and Requires

- Modeling of Environmental Effects in Genome-Wide Association Studies Identifies and as Novel Loci Influencing Serum Cholesterol Levels

- Inverse Correlation between Promoter Strength and Excision Activity in Class 1 Integrons

- Activation of Mutant Enzyme Function by Proteasome Inhibitors and Treatments that Induce Hsp70

- Postnatal Survival of Mice with Maternal Duplication of Distal Chromosome 7 Induced by a / Imprinting Control Region Lacking Insulator Function

- The Werner Syndrome Protein Functions Upstream of ATR and ATM in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition and Double-Strand DNA Breaks

- Maternal Ethanol Consumption Alters the Epigenotype and the Phenotype of Offspring in a Mouse Model

- Understanding Gene Sequence Variation in the Context of Transcription Regulation in Yeast

- miR-30 Regulates Mitochondrial Fission through Targeting p53 and the Dynamin-Related Protein-1 Pathway

- Elevated Levels of the Polo Kinase Cdc5 Override the Mec1/ATR Checkpoint in Budding Yeast by Acting at Different Steps of the Signaling Pathway

- Alternative Epigenetic Chromatin States of Polycomb Target Genes

- Co-Orientation of Replication and Transcription Preserves Genome Integrity

- A Comprehensive Map of Insulator Elements for the Genome

- Environmental and Genetic Determinants of Colony Morphology in Yeast

- U87MG Decoded: The Genomic Sequence of a Cytogenetically Aberrant Human Cancer Cell Line

- The MCM-Binding Protein ETG1 Aids Sister Chromatid Cohesion Required for Postreplicative Homologous Recombination Repair

- Genetic Dissection of Differential Signaling Threshold Requirements for the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway

- Differential Localization and Independent Acquisition of the H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 Chromatin Modifications in the Adult Germ Line

- Genetic Crossovers Are Predicted Accurately by the Computed Human Recombination Map

- Collaborative Action of Brca1 and CtIP in Elimination of Covalent Modifications from Double-Strand Breaks to Facilitate Subsequent Break Repair

- Distinct Type of Transmission Barrier Revealed by Study of Multiple Prion Determinants of Rnq1

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies as a Novel Susceptibility Gene for Osteoporosis

- and Regulate Reproductive Habit in Rice

- Nonsense-Mediated Decay Enables Intron Gain in

- Altered Gene Expression and DNA Damage in Peripheral Blood Cells from Friedreich's Ataxia Patients: Cellular Model of Pathology

- The Systemic Imprint of Growth and Its Uses in Ecological (Meta)Genomics

- The Gift of Observation: An Interview with Mary Lyon

- Genotype and Gene Expression Associations with Immune Function in

- The Elongator Complex Regulates Neuronal α-tubulin Acetylation

- Rising from the Ashes: DNA Repair in

- Mis-Spliced Transcripts of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor α6 Are Associated with Field Evolved Spinosad Resistance in (L.)

- BRIT1/MCPH1 Is Essential for Mitotic and Meiotic Recombination DNA Repair and Maintaining Genomic Stability in Mice

- Non-Coding Changes Cause Sex-Specific Wing Size Differences between Closely Related Species of

- Evidence for Pervasive Adaptive Protein Evolution in Wild Mice

- Evolutionary Mirages: Selection on Binding Site Composition Creates the Illusion of Conserved Grammars in Enhancers

- VEZF1 Elements Mediate Protection from DNA Methylation

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- A Major Role of the RecFOR Pathway in DNA Double-Strand-Break Repair through ESDSA in

- Kidney Development in the Absence of and Requires

- The Werner Syndrome Protein Functions Upstream of ATR and ATM in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition and Double-Strand DNA Breaks

- Alternative Epigenetic Chromatin States of Polycomb Target Genes

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy