-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

The Werner Syndrome Protein Functions Upstream of ATR and ATM in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition and Double-Strand DNA Breaks

WRN-1 is the Caenorhabditis elegans homolog of the human Werner syndrome protein, a RecQ helicase, mutations of which are associated with premature aging and increased genome instability. Relatively little is known as to how WRN-1 functions in DNA repair and DNA damage signaling. Here, we take advantage of the genetic and cytological approaches in C. elegans to dissect the epistatic relationship of WRN-1 in various DNA damage checkpoint pathways. We found that WRN-1 is required for CHK1 phosphorylation induced by DNA replication inhibition, but not by UV radiation. Furthermore, WRN-1 influences the RPA-1 focus formation, suggesting that WRN-1 functions in the same step or upstream of RPA-1 in the DNA replication checkpoint pathway. In response to ionizing radiation, RPA-1 focus formation and nuclear localization of ATM depend on WRN-1 and MRE-11. We conclude that C. elegans WRN-1 participates in the initial stages of checkpoint activation induced by DNA replication inhibition and ionizing radiation. These functions of WRN-1 in upstream DNA damage signaling are likely to be conserved, but might be cryptic in human systems due to functional redundancy.

Published in the journal: The Werner Syndrome Protein Functions Upstream of ATR and ATM in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition and Double-Strand DNA Breaks. PLoS Genet 6(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000801

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000801Summary

WRN-1 is the Caenorhabditis elegans homolog of the human Werner syndrome protein, a RecQ helicase, mutations of which are associated with premature aging and increased genome instability. Relatively little is known as to how WRN-1 functions in DNA repair and DNA damage signaling. Here, we take advantage of the genetic and cytological approaches in C. elegans to dissect the epistatic relationship of WRN-1 in various DNA damage checkpoint pathways. We found that WRN-1 is required for CHK1 phosphorylation induced by DNA replication inhibition, but not by UV radiation. Furthermore, WRN-1 influences the RPA-1 focus formation, suggesting that WRN-1 functions in the same step or upstream of RPA-1 in the DNA replication checkpoint pathway. In response to ionizing radiation, RPA-1 focus formation and nuclear localization of ATM depend on WRN-1 and MRE-11. We conclude that C. elegans WRN-1 participates in the initial stages of checkpoint activation induced by DNA replication inhibition and ionizing radiation. These functions of WRN-1 in upstream DNA damage signaling are likely to be conserved, but might be cryptic in human systems due to functional redundancy.

Introduction

Werner syndrome (WS) is associated with rapid acceleration of aging, and is caused by mutations in the RecQ family DNA helicase gene, WRN [1]. Clinical symptoms of WS include short stature, hair-graying, cataract formation, type II diabetes, osteoporosis, atherosclerosis, and neoplasm of mesenchymal origins [2]–[5]. The role of WRN in premature aging may be linked to telomere regulation. WS fibroblasts have a reduced replicative life span, which is alleviated by the forced expression of the human telomerase (hTERT) gene [6]. A link between WRN, telomere DNA metabolism and progeria has been demonstrated in mouse Wrn and Terc (telomerase RNA) knockout models [7]. Symptoms of Werner syndrome appeared in late-generation Wrn and Terc double mutant mice together with accelerated telomere loss, while the corresponding single mutants did not show such phenotypes. The role of WRN in telomere DNA metabolism is also supported by a report showing that WRN localizes to telomeric DNA during the S-phase of telomerase-defective ALT cells and by its ability to resolve telomeric D loops via its helicase and nuclease functions in vitro [8].

WRN is one of the five human RecQ family helicases and possesses an N-terminal exonuclease domain homologous to E. coli RNaseD [9]–[12]. The two enzymatic activities of WRN and the presence of chromosomal rearrangements and deletions in WS cells led to the notion that WRN is involved in the resolution of stalled replication forks, and in various DNA repair and recombination pathways [2]–[5]. This view is supported by the fact that WRN interacts with proteins known to participate in DNA processing, such as FEN1, RPA, polymerase δ, PCNA, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1, NBS1, γ-H2AX, and Ku80/70 [3],[4],[13],[14]. Moreover, WRN is a 3′—5′ helicase capable of unwinding a variety of DNA structures that act as intermediates in recombinational repair of stalled replication forks such as Holliday junctions, bubble substrates, D-loops, flap duplexes, and 3′-tailed duplex substrates [2],[3].

Nevertheless, relatively little is known about the cellular functions of WRN in DNA repair and in DNA damage signalling. Furthermore, it is not known if any of the in vitro biochemical activities reported for WRN are required for its function in vivo. Human WRN was implicated in a G2 cell cycle checkpoint, in response to the inhibition of chromosomal decatenation [15]. In addition, human WRN is required for full ATM activation and for slowing down S-phase progression in response to DNA interstand crosslinks or in response to the inhibition of DNA replication [16].

Here we exploit the Caenorhabditis elegans germ line which is the only proliferative tissue in adult worms, as an experimental system to analyse the functions of WRN in DNA damage signalling. The gonad contains various germ cell types that are arranged in an ordered distal to proximal gradient of differentiation [17; Figure 1A]. The distal end of the gonad is comprised of a mitotic stem cell compartment, followed by a ‘transition zone’ where entry into meiotic prophase occurs. DNA replication failure and DNA double strand breaks lead to a prolonged cell cycle arrest of mitotic germ cells [18].

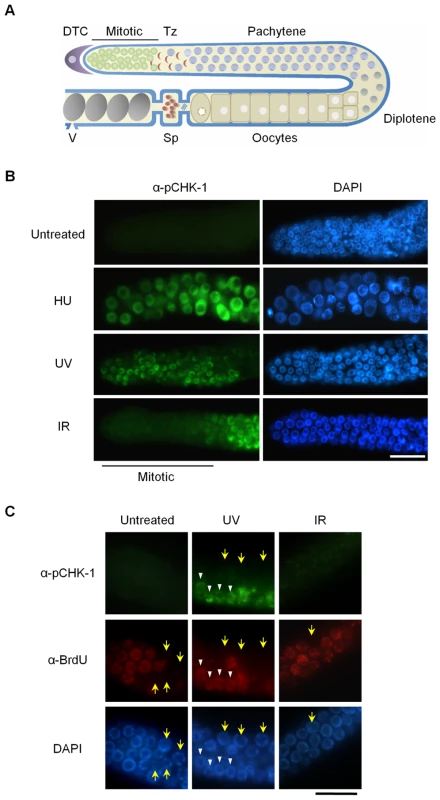

Fig. 1. CHK-1 phosphorylation in C. elegans germ cells after DNA replication inhibition or DNA damage.

(A) Schematic representation of a gonad arm in an adult C. elegans hermaphrodite. DTC, distal tip cell; Mitotic, mitotically proliferating region, Tz, transition zone; Sp, spermathecum containing sperms; V, vulva at the uterus containing embryos. (B,C) To inhibit DNA replication, wild-type N2 C. elegans worms were treated with 25 mM hydroxyurea (HU) from the L4 stage for 16 h. DNA damage was induced by irradiating one-day-old adult worms with UV (100 J/m2) or γ-rays (75 Gy), and cultivating them for 1 h. In (C), worms were fed with BrdU-labeled E. coli cells for 30 min before DNA damage and then with unlabeled E. coli cells for 1 h after the damage. Gonads were isolated and reacted with (B) phospho-CHK1(Ser345) antibody and with (C) both phospho-CHK1(Ser345) and BrdU antibodies. Mitotic (premeiotic) regions of the gonads were observed under a fluorescence microscope. Magnification bars, 25 μm. The C. elegans genome encodes four worm RecQ family proteins that correspond to their human orthologs. C. elegans WRN-1 is most closely related to human WRN, but has no exonuclease domain [19]. We previously showed that WRN-1 depletion by RNA leads to reduced lifespan. We also observed an increased incidence of diverse developmental defects whose frequency was further accentuated by γ-irradiation [19]; a phenotype likely associated with DNA repair defects occurring during development [20]. In addition, we provided evidence for an abnormal checkpoint response to DNA replication blockage.

In this study, we further explore DNA damage response defects associated with WRN-1 in the C. elegans germ cell system, and particularly focus on the role of wrn-1 in the cell cycle checkpoint in response to DNA replication blockage and ionizing radiation. We show that WRN-1 functions together with RPA-1 upstream of C. elegans ATR in the intra S-phase checkpoint pathway, and upstream of C. elegans ATM and RPA to trigger cell cycle arrest in response to IR-induced double-strand DNA breaks.

Results

CHK-1 Phosphorylation in Proliferating Germ Cells of C. elegans Is Induced by DNA Replication Blockage and UV, and Is Associated with S-Phase Arrest

To probe activation of the DNA damage checkpoint in mitotic C. elegans germ cells and also to examine the relationship between WRN-1 and CHK-1, we used a commercially available antibody against the conserved Ser345 phosphoepitope of human CHK1 corresponding to C. elegans Ser344. In humans, CHK1 is phosphorylated by ATR on Ser317 (which is not conserved in C. elegans) and/or Ser345 when DNA replication is inhibited or upon DNA damage induced by UV, ionizing radiation, or genotoxic chemicals [21]. As shown in Figure 1B, CHK-1 phosphorylation was absent before induction of DNA damage, but became apparent in the nuclei of enlarged germ cells that result from inhibition of DNA replication by hydroxyurea (HU). It had been previously shown that treating C. elegans germ lines with the deoxyribonucleotide-depleting drug hydroxyurea leads to transient germ cell cycle arrest [22]. Germ cell cycle arrest results in enlarged cells and nuclei due to cessation of cell division while cellular growth continues unabated. CHK-1 phosphorylation was also observed in the majority of germ cell nuclei after UV radiation (Figure 1B). One hour after γ-irradiation (IR: ionizing radiation), phosphorylation of CHK-1 was observed in germ cell nuclei at the pachytene and transition stages but not in those of the mitotically proliferating region (Figure 1B).

To ask why phosphorylation of CHK1 Ser345 is detected in some cells of the proliferating region after UV treatment but not after IR treatment, we labeled S-phase cells with 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). Adult worms were exposed to BrdU for 30 min and irradiated with UV or IR, followed by incubation of 1 h in the absence of BrdU. Thereafter the gonads were simultaneously reacted with antibodies against BrdU and pCHK1-Ser345. Incorporation of BrdU into chromosomal DNA was observed in medium-sized germ cells of the mitotic region, but not in smaller and larger cells (marked by yellow arrows) that are probably in G1 or G2 phase, respectively (Figure 1C). Likewise, medium-sized UV-treated germ cells showed nuclear BrdU-staining, and only those cells (marked by white arrowheads in Figure 1C) were positive for pCHK1-Ser345, suggesting that CHK1-Ser345 phosphorylation is associated with S phase. One hour after IR treatment, none of the germ cells were positive for pCHK1-Ser345, although more than half of the IR-treated cells in the distal part of the germ line showed nuclear BrdU-staining. The observation that pCHK1-Ser345 was absent even in S phase IR-treated germ cells, agrees with the finding that phosphorylation of CHK1-Ser345 is not induced by double-strand DNA breaks in mammalian cells [23]. IR-treated germ cells in the mitotic region finally arrest in G2 phase [24], but 1 h after irradiation they were still in various phases of the cell cycle, which has been estimated to last 16–24 h [25].

WRN-1 Is Required for CHK-1 Phosphorylation after DNA Replication Blockage, but Not after UV Radiation

Our previous RNAi-based results hinted that wrn-1 might be involved in the S-phase DNA replication checkpoint [19]. To confirm this result and to further examine the function of wrn-1 in the DNA replication checkpoint, we obtained wrn-1 deletion mutants and backcrossed them six times to eliminate unlinked mutations (Figure S1A). The 196 bp deletion mutation of wrn-1 (gk99) eliminates the start codon of wrn-1 and results in the complete absence of WRN-1 protein as determined by immunostaining germ cells with the specific WRN-1 antibodies that we generated (Figure S1B) and by Western blotting (data not shown). We next wished to determine the role of WRN-1 in relation to the previously established roles of ATL-1 (worm ATR), and CHK-1 in the DNA replication checkpoint by analyzing the morphology of DAPI-stained nuclei of germ cells after HU treatment (Figure S2A). In contrast to the wild type where germ cell nuclei were enlarged and had a diffuse distribution of chromatin in response to HU treatment, the majority of nuclei in wrn-1(gk99), atl-1(RNAi), or chk-1(RNAi) worms were small and apparently continued to divide. These nuclei had unusually compact chromatin and showed signs of extensive chromatin fragmentation, a phenotype likely to reflect escape from S-phase arrest and subsequent abnormal mitosis (Figure S2A). Inhibition by chk-1 and atl-1 RNAi was not complete but extensive, as determined by reverse transcription of mRNAs followed by quantitative PCR amplification (Figure S3A). In contrast, atm-1(gk186) cells, the nuclei were uniformly enlarged as in wild type cells, suggesting that ATM-1 is not required for the DNA replication checkpoint, in agreement with Garcia-Muse and Boulton [26]. The convergence of the wrn-1(gk99) and the atl-1 and chk-1 RNAi phenotypes suggested that wrn-1, atl-1, and chk-1 might act in the same genetic pathway needed for HU-mediated cell cycle arrest. To test this hypothesis we asked if the phenotypes resulting from atl-1 or chk-1 RNAi were aggravated in the wrn-1(gk99) background and found that this was not the case (Figure S2A). Thus it is likely that wrn-1 indeed functions in the same linear genetic pathway as atl-1 and chk-1 to mediate HU-dependent cell cycle arrest.

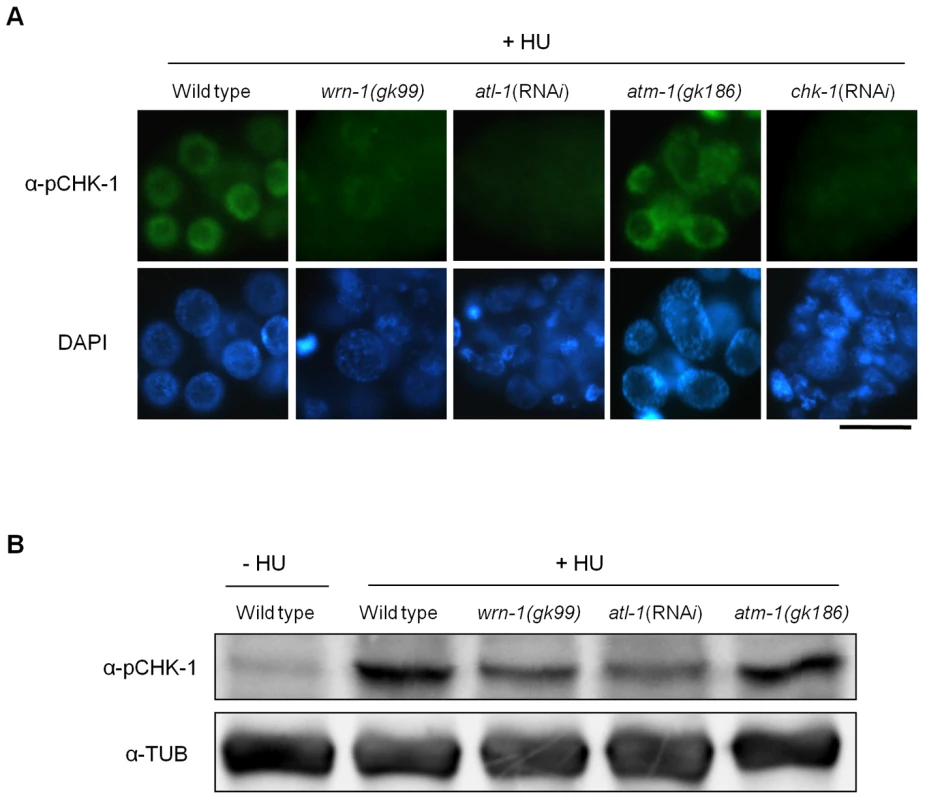

Having established that wrn-1, atl-1, and chk-1 are required for activation of the intra S-phase checkpoint, we next tested if CHK-1 phosphorylation after HU treatment depends on WRN-1 (Figure 2A). We found that CHK-1 phosphorylation in germ cells was greatly reduced in a wrn-1(gk99) mutant (and also after RNAi-mediated wrn-1 knockdown, data not shown) and after atl-1 RNAi (Figure 2A). The dependence of CHK-1 phosphorylation on WRN-1 and ATL-1 after DNA replication inhibition was also confirmed by Western blotting of worm extracts with the pSer345 CHK1 antibody (Figure 2B), indicating that CHK-1 phosphorylation is reduced in wrn-1 and atl-1 in the extracts. This reduction is not as extensive as the reduction observed by the immunostaining of germ cells but nevertheless appears to reflect a reduction in CHK-1 phosphoprylation. CHK-1 protein levels are likely to be the same in wild-type, wrn-1 or atl-1 worms, given that we did not observe a difference in chk-1 mRNA levels in those strains (Figure S3B). We could not directly confirm CHK-1 proteins levels due to the absence of a specific antibody (data not shown). Unlike the cases of wrn-1 and atl-1 deficiencies, the CHK1 phosphorylation was not affected by knockout of a C. elegans ATM homolog, ATM-1 (Figure 2A and 2B).

Fig. 2. WRN-1 is required for the phosphorylation of CHK-1(S345) induced by inhibition of DNA replication.

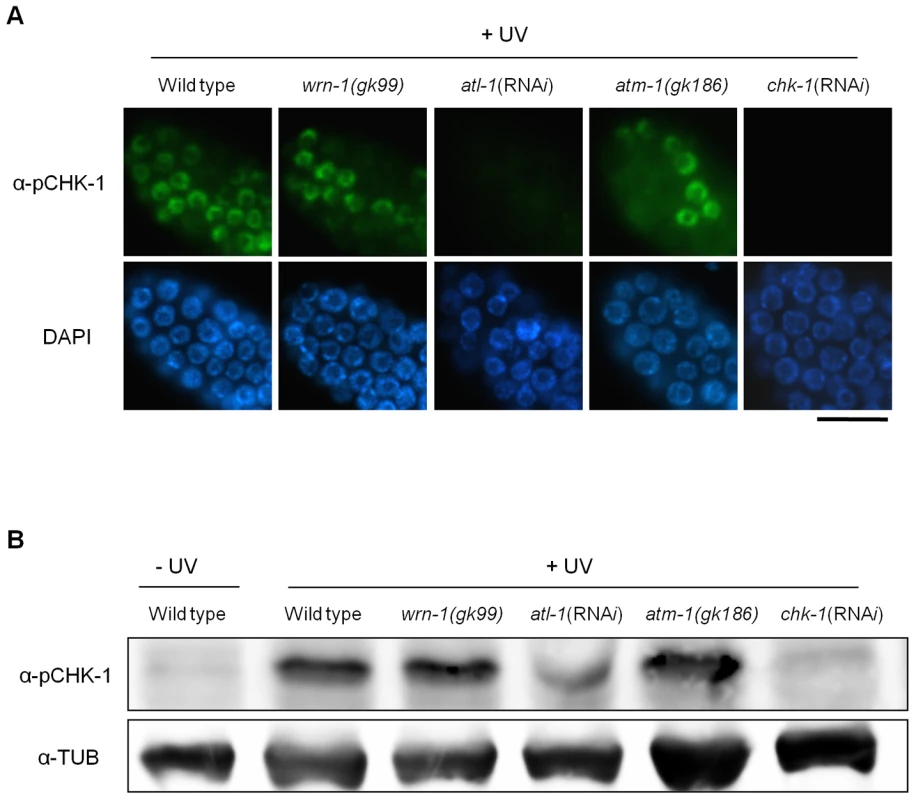

Wild-type N2, wrn-1(gk99), atl-1(RNAi), atm-1(gk186), and chk-1(RNAi) worms were treated with 25 mM hydroxyurea (HU) from the L4 stage for 16 h. To knockdown atl-1 (ATR homolog) or chk-1 expression, worms were fed E. coli cells expressing the cognate double-stranded RNA from the L1 stage to the adult stage. (A) Phosphorylation of CHK-1(S345) in premeiotic germ cells probed with phospho-CHK1(S345) antibody. Magnification bar, 10 μm. (B) Worm extracts analyzed by western blotting using antibodies to phospho-CHK1(S345), and to α-tubulin as a control. In contrast to the effect of DNA replication inhibition, CHK-1 phosphorylation caused by UV-radiation was not affected by the wrn-1 mutation (Figure 3A), whereas it was greatly attenuated by atl-1 RNAi. This observation in germ cells was confirmed by Western analysis of worm extracts (Figure 3B). In summary, our data suggest that WRN-1 functions upstream of CHK-1 in the DNA replication checkpoint but not in the DNA damage checkpoint activated by UV radiation. Either deficiency of atm-1 or wrn-1 was not detrimental enough to induce CHK-1 phosphorylation, in the absence of UV-radiation (Figure S4).

Fig. 3. The wrn-1 mutation does not affect the phosphorylation of CHK-1(S345) after UV-irradiation.

Wild-type N2, wrn-1(gk99), atl-1(RNAi), atm-1(gk186), and chk-1(RNAi) worms were irradiated as one-day-old adults with UV radiation (100 J/m2) and cultured for 1 h before immunostaining. atl-1 and chk-1 expression was knocked down as in Figure 2. Phosphorylation of CHK-1(S345) was probed as in Figure 2 by (A) immunostaining of mitotic germ cells and (B) western analysis of worm extracts. Magnification bar, 25 μm. WRN-1 Is Required for the Efficient Formation of RPA-1 Foci in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition

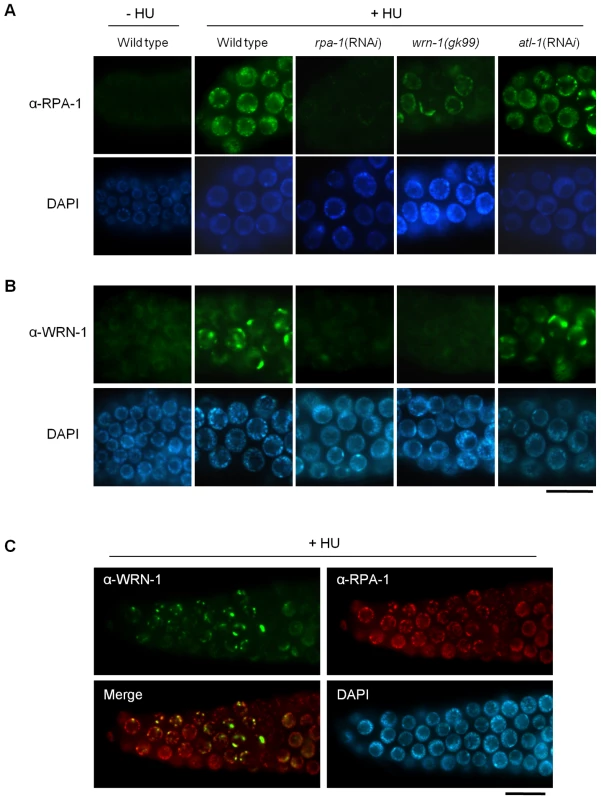

Since WRN-1 controls CHK-1 phosphorylation after DNA replication inhibition, we asked whether RPA focus formation, which occurs upstream of CHK1 and ATR in mammalian cells, is also influenced by WRN-1. After HU treatment the nuclei of wild type cells were enlarged and contained RPA-1 foci, as demonstrated by Garcia-Muse and Boulton [26] (Figure 4A). RPA-1 foci disappeared, and RPA-1 protein (Figure S5C) in worm extracts was greatly reduced by rpa-1 RNAi as well as the mRNA level (Figure S3A), (this also confirms efficient RPA-1 depletion and the specificity of our antibody). In wrn-1(gk99) germ cells, RPA-1 foci were not as abundant or intensely fluorescent as in wild type cells (Figure 4A and Figure S5A with and without HU treatment, respectively). However, RPA-1 focus formation was not affected by atl-1 knockdown, as shown by Garcia-Muse and Boulton [26], and in agreement with the fact that in mammalian cells RPA binds to single-stranded DNA and then recruits ATR by binding to ATRIP [27]. In line with the results of Figure 2, rpa-1 RNAi also largely eliminated the phosphorylation of CHK-1-Ser345 induced by HU (Figure S2B). The observation that the wrn-1 mutation affects RPA-1 focus formation suggested that WRN-1 either functions upstream of RPA-1 or in the same step as RPA-1 focus formation. To distinguish between these possibilities, we tested whether nuclear localization of WRN-1 was affected by RPA-1. WRN-1 was present in the nuclei of all control germ cells and its abundance increased significantly after HU treatment (Figure 4B). In addition, the distribution of WRN-1 in the nucleoplasm became uneven, and WRN-1 aggregated into spots or lumps that were less abundant than RPA-1 foci in response to HU treatment. In rpa-1 knockdown cells, neither the increase in WRN-1 abundance nor its aggregation into spots or lumps occurred upon HU treatment (Figure 4B and Figure S5B with and without HU treatment, respectively). At present, we can not completely rule out that the failure of CHK-1-Ser345 phosphorylation and WRN-1 spot formation upon RPA-1 depletion could be due to abolished DNA replication predicted to occur when RPA-1 is fully depleted. We consider that this possibility is unlikely, as we only partially depleted RPA-1 allowing a continued germ cell proliferation and DNA replication. Furthermore, we found that almost all WRN-1 nuclear spots colocalized with RPA-1 foci, but not vice versa (Figure 4C), further supporting the notion that RPA-1 may acts prior to or in the same step as WRN-1 at stalled replication forks.

Fig. 4. Reciprocal dependence of RPA-1 focus formation and nuclear localization of WRN-1 after DNA replication inhibition.

One-day old adult wild-type N2, rpa-1(RNAi), wrn-1(gk99), and atl-1(RNAi) worms were treated with hydroxyurea (25 mM) for 8 h. Knockdown of atl-1 and rpa-1 was carried out as in Figure 2 but from the L4 stage for 16 h, and premeiotic germ cells were stained with antibodies against (A) RPA-1 and (B) WRN-1. (C) Partial colocalization of RPA-1 and WRN-1 in the nuclei of premeiotic germ cells after hydroxyurea treatment. All the WRN-1 spots overlap with RPA-1 foci but not vice versa. Magnification bars, 10 μm. WRN-1 Participates Upstream of ATM-1 and RPA-1, but Downstream of MRE-11, in the Checkpoint Activation Induced by Ionizing Radiation

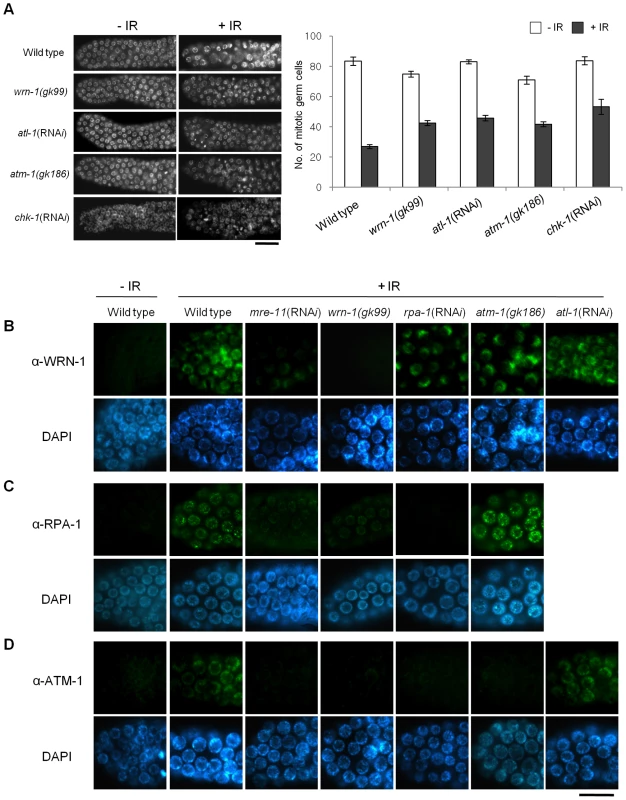

We next wished to test if wrn-1 functions in the checkpoint pathway that leads to cell cycle arrest of γ-irradiated proliferating germ cells. After γ-irradiation, the number of germ cells in the mitotic region of gonads is greatly reduced in wild type worms (Figure 5A) due to cell cycle arrest. Arrested cells, however, enlarge due to continued cellular growth in the absence of cell division [18]. We found that in response to IR the number of mitotic germ cells was much less reduced in wrn-1(gk99), atl-1(RNAi), atm-1(gk186), and chk-1(RNAi) gonads as compared to wild type gonads, suggesting that WRN-1 and the three other well-known checkpoint proteins play significant roles in IR-dependent cell cycle arrest (Figure 5A). To determine the epistatic relationships of WRN-1 in this checkpoint signaling pathway, we examined whether the nuclear localization of WRN-1 was altered in response to IR and if so whether this depended on various known DNA damage checkpoint and repair proteins. We found that WRN-1 accumulated on the chromatin of irradiated wild type cells and that this accumulation was greatly attenuated by mre-11(RNAi), but was unaffected by rpa-1(RNAi), atl-1(RNAi), and the atm-1(gk186) mutation (Figure 5B and Figure S6A with and without IR, respectively) (the RNAi efficiencies were confirmed in Figure S3A). Since C. elegans RPA-1 was reported to form nuclear foci in response IR [26], we tested whether their formation was affected by WRN-1. In fact, IR-induced RPA-1 focus formation was significantly reduced by the wrn-1(gk99) mutation (Figure 5C). In contrast, RPA-1 focus formation was more evident in the atm-1 mutant than in wild type cells, indicating that atm-1 is not required for RPA-1 focus formation, a result in agreement with the previous report by Garcia-Muse and Boulton [26]. We next asked if ATM accumulates on chromatin in response to IR and if so whether this depends on wrn-1. For this purpose, we generated a specific ATM-1 antibody and found that ATM accumulated on the chromatin of wild type cells in response to IR treatment (Figure 5D). However, it did not accumulate significantly upon IR treatment of mre-11(RNAi), wrn-1(gk99), or rpa-1(RNAi) cells, implying that the IR-dependent accumulation of ATM on chromatin requires the products of all three genes (Figure 5D and Figure S6B with and without IR, respectively). In contrast, atl-1 knockdown did not affect ATM-1 localization (Figure 5D), suggesting that ATM-1 acts in a parallel or independent pathway. Our combined results therefore suggest that sequential action of MRE-11 and WRN-1 is needed for efficient RPA-1 focus formation, and that this in turn leads to the nuclear accumulation of ATM-1 in response to IR.

Fig. 5. WRN-1 influences cell cycle arrest and the nuclear localization of ATM-1 and RPA-1 after γ-irradiation.

(A) L4-stage wild-type N2, wrn-1(gk99), atl-1(RNAi), atm-1(gk186) and chk-1(RNAi) worms were irradiated with γ-rays (75 Gy), and cultured for 12 h before scoring germ cells. Germ cells in the mitotically proliferating region of gonads (within 75 µm of the tip cell) were stained with DAPI and counted under a fluorescence microscope. Error bars indicate standard errors of means of 12 worms of each genotype. (B–D) One-day-old adult worms of wild-type N2, wrn-1(gk99), atl-1(RNAi), atm-1(gk186), chk-1(RNAi), rpa-1(RNAi), and mre-11(RNAi) strains were irradiated with γ -rays (75 Gy) and cultured for 1 h before immunostaining. Mitotic germ cells were stained using antibody against (B) WRN-1, (C) RPA-1, and (D) ATM-1. Knockdown of atl-1, chk-1, mre-11, and rpa-1 were carried out from (A) the L1 and (B–D) L4 stages. Magnification bars, (A) 25 µm and (B–D) 10 µm. Discussion

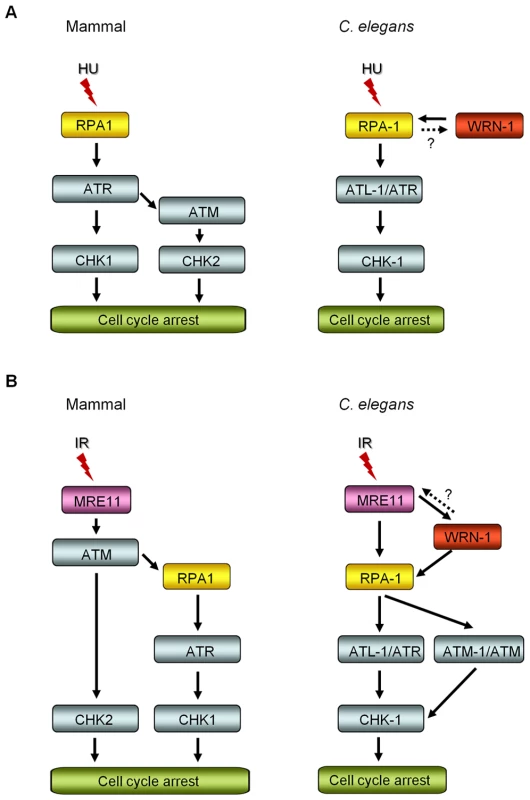

We have demonstrated that WRN-1 regulates the DNA replication checkpoint upstream of CHK-1, and probably in the same step as RPA-1, but that the checkpoint activation induced by UV is not affected by WRN-1. It is an intriguing question whether the helicase activity of WRN-1 is required for the DNA replication checkpoint. We have observed normal cell cycle regulation after HU - or IR-treatment of wrn-1(tm764) mutants, which have a deletion from the fifth exon to the following intron (Figure S1A, S1B, S1C, S1D). Since this deletion eliminates the helicase motif, it is likely to abolish the helicase activity of wild type WRN-1 that was measured by Hyun et al. [28] in vitro. Therefore, the helicase activity of WRN-1 seems not to be essential for checkpoint function. However, this activity is probably essential for the function of WRN-1 in DNA repair, since the wrn-1(tm764) as well as the wrn-1(gk99) mutation resulted in increased frequency of developmental defects in response to IR (Figure S1E, S1F). A similar observation was made for SGS1, the only RecQ helicase in S. cerevisiae: its helicase activity was not required for activation of RAD53, a CHK2 homolog [29], after inhibition of DNA replication. Among five RecQ homologs in humans, only limited checkpoint activity has been observed for WRN, namely upon inhibition of chromosomal decatenation [15] and in the activation of ATM induced by interstrand DNA crosslinking and DNA replication inhibition [16]. We propose that WRN-1 affects CHK-1, and probably also ATL-1/ATR activation, by increasing the stability of RPA on the single stranded DNA (ssDNA) at arrested DNA replication forks (Figure 6A). While the components of the so called 9-1-1 complex, implicated in recognizing arrested replication forks are conserved in C. elegans [30]–[32], the gene coding for ATRIP, which recruits ATR to RPA on ssDNA, has not been identified in C. elegans. WRN-1 may be able to substitute for ATRIP and recruit ATL-1/ATR to the fork, a hypothesis supported by the finding that RPA physically interacts with WRN [28],[33] and by the colocalization of WRN-1 and RPA-1 (Figure 4C). However, at present we do not know if C. elegans WRN-1 physically interacts with RPA and ATL-1/ATR in vivo. The positioning of WRN-1 in the same step or upstream of RPA-1 in our model differs from the situation in human cells, where depletion of WRN does not affect fork recovery but impairs fork progression after replication inhibition [34]. Another possible function of WRN-1 is to promote the uncoupling of DNA polymerase and helicase activities at stalled replication forks, thereby increasing the length of ssDNA and the concomitant coating of the ssDNA with RPA-1 [35]. Although we place WRN-1 in the same step as RPA-1, upstream of ATR and CHK1, WRN-1 is not as essential for worm survival under normal conditions as these three checkpoint proteins. A possible reason for this difference is that WRN-1 may only respond to exogenously induced stalls of replication forks, but not to those formed spontaneously. In agreement with this idea, RAD-51 foci, indicative of replication fork collapse, were not observed in wrn-1(gk99) cells in the absence of exogenously-induced DNA damage (data not shown), whereas they were observed in the atl-1(tm853) mutant [26]. Unlike the case of DNA replication inhibition, WRN-1 is not needed for the checkpoint activation induced by UV; this could be due to the ability of ATR to bind to UV-damaged DNA [36] or due to the presence of another protein that recruits ATR to UV-damaged DNA.

Fig. 6. Comparison of DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways between mammals and C. elegans, and roles of the C. elegans WRN homolog in these pathways.

(A) After DNA replication inhibition by hydroxyurea (HU), ATM-CHK2 activation is induced in the downstream of ATR in mammals, in addition to ATR-CHK1 activation [51]. In C. elegans, the nuclear focus formation of RPA-1 and WRN-1 are interdependent, however RPA-1 knockdown may have indirectly affected WRN-1 foci by reducing the number of replication forks. ATR/ATL-1 is inserted between RPA-1 and CHK-1, because it was positioned below RPA-1 by Garcia-Muse and Boulton [26]. (B) Ionizing radiation (IR) induces ATR-CHK1 activation in the downstream of ATM, as proposed by Jazayeri et al. [44] in mammals. In C. elegans, the nuclear localization of WRN-1 in response to IR is affected by MRE-11 and is a prerequisite for efficient RPA-1 focus formation. It needs to be determined whether WRN-1 conversely affects the nuclear localization or function of MRE-11, as labeled by a question mark. The nuclear accumulation of ATM requires WRN-1 and RPA-1, as well as MRE-11. ATR/ATL-1 is positioned below RPA-1, as proposed by Garcia-Muse and Boulton [26], and is required for effective cell cycle arrest (Figure 5A). CHK-1 is located below ATR, because it was shown to be essential for cell cycle arrest in response to IR by Kalogeropoulos et al. [52] and also in Figure 5A. We found that in contrast to wild type, the cell cycle arrest was significantly alleviated in wrn-1 mutants by treatment with 75 Gy of IR, as well as in atl-1, atm-1, and chk-1 deficient animals (Figure 5A). Stergiou et al. [37] found that the atm-1 mutation did not affect the cell cycle arrest induced by high dose IR (120 Gy), but they noted a moderate effect on the apoptosis of germ cells after low dose IR (20–40 Gy). However, another study based on atm-1 RNAi reported that ATM-1 is needed for IR-dependent cell cycle arrest upon treatment with 75 Gy of IR [26].

Our results suggest that WRN-1 is an upstream component of the signaling pathway that mediates IR-dependent cell cycle arrest. We found that in response to IR the nuclear localization of WRN-1 depended on the presence of MRE-11 to a significant extent (Figure 5B), and that RPA-1 focus formation was promoted by WRN-1 (Figure 5C). In human cells, WRN interacts with the MRN complex via the NBS1 subunit of MRN, and WRN focus formation depends on NBS1 [13],[14]. Nevertheless, it is likely that the accumulation of C. elegans WRN-1 is regulated differently, as there is no NBS1 homolog in the worm genome. However, the fact that WRN translocates to double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) within a few minutes, with the same kinetics as NBS1, also agrees with the proposed role of WRN-1 at the initial stage of the checkpoint pathway [38].

We propose that WRN-1 functions downstream of MRE-11 and upstream of RPA-1 in the DSB signaling pathway leading to cell cycle arrest, as illustrated in Figure 6B. Nevertheless, it is not yet clear whether WRN-1 also affects the nuclear localization or function of MRE-11. Recently, the MRN complex, CtIP, and Exo1 nucleases were found to be involved in the resection of DSBs to produce ssDNA in vertebrate cells [39]–[41], the process that initiates ATR-mediated DNA damage signaling [42] and homologous recombination: a RecQ family helicase BLM participates in the DSB resection as a partner of Exo1 [43]. Likewise, C. elegans WRN-1 may affect the activity of MRE-11 nuclease, which could explain the stimulation of RPA-1 focus formation by WRN-1. In the model of DNA damage signaling pathway depicted in Figure 6B, ATM-1 is located downstream of RPA-1, unlike ATM in mammals which functions upstream of RPA [44]. However, another single-stranded DNA binding protein, hSSB1, was recently found to be essential for ATM activation in response to IR [45]. We therefore speculate that the role of RPA-1 in activating ATM in C. elegans may have been acquired by hSSB1 in vertebrates.

Ionizing radiation (IR) did not induce CHK-1-Ser345 phosphorylation in mitotically proliferating germ cells (Figure 1A). However, CHK-1 was required for the efficient inhibition of germ cell proliferation upon IR (Figure 5A) in accord with previous reports. The absence of CHK-1-Ser345 phosphorylation (Figure 1B) is in line with a previous report showing that Ser345 of CHK1 is not phosphorylated by IR in mammalian cells whereas Ser317, which is not conserved in C. elegans, is phosphorylated [23]. We thus hypothesize that some other residue in C. elegans CHK-1 is phosphorylated after IR to activate the protein.

In summary, the C. elegans homolog of human WRN helicase, WRN-1, regulates the DNA damage signaling pathway induced by DNA replication inhibition and double-stranded DNA breaks upstream of ATR, probably at or close to the step involving RPA localization, and upstream of ATM. Human WRN was recently found to be essential for the activation of ATM after treating cells with UV-activated psoralen and hydroxyurea, but ATM activation induced by γ-rays was not dependent on WRN [16]. These results in humans differ from our findings in C. elegans, where WRN-1 is required for the nuclear accumulation of ATM induced by DSBs, as well as for activation of ATR and CHK1 at stalled replications forks. Presumably, the relative levels of key proteins involved in DNA damage signaling vary between organisms, tissues, and cell types, so that the extent of the contribution of various proteins of each (sub)pathway is likely to differ between organisms. We therefore consider that the upstream DNA damage signaling functions of WRN-1 uncovered here are likely to be conserved, but might be cryptic in human systems due to functional redundancy. It will be interesting to follow up this possibility in future studies and to ask how C. elegans WRN-1 recruits and activates RPA and ATM in response to checkpoint activation.

Materials and Methods

Strains and EST Clones

C. elegans strain Bristol N2 was maintained as described [46] at 20°C unless noted. The wrn-1(gk99) and atm-1(gk186) strains were obtained from the C. elegans Genetics Center (St Paul, MN, USA). wrn-1(tm764), which was generated as part of the National Bioresource Project (Japan), was obtained from Dr. Shohei Mitani (Tokyo Women's Medical University School of Medicine). The mutant strains were outcrossed six times with N2 to remove possible unrelated mutations. The EST clones of atl-1 (yk1218d05), chk-1 (yk1302e07), rpa-1 (yk787c12), and mre-11 (yk133b9) were provided by Dr. Y. Kohara (National Institute of Genetics, Japan).

Bacteria-Mediated RNAi

Bacteria-mediated RNAi of chk-1, atl-1, rpa-1, and mre-11 was performed as described, with minor modifications [47]. An approximately 1.2 kb cDNA fragment of the open reading frame (ORF) of Y39H10A.7 (CHK-1) was derived from the EST clone yk1302e07 after being digested with XhoI. The EST clone yk1218d05 of atl-1 was digested using BamHI and PstI to produce a 1.1 kb cDNA fragment. The EST clone yk787c12 of rpa-1 was digested using XhoI to produce a 0.64 kb cDNA fragment, and yk133b9 of mre-11 using XhoI and XbaI to produce a 1.6 kb fragment.

The cDNA fragments were cloned into pPD129.36(L4440) plasmid and transformed into Escherichia coli strain HT115(DE3). Ten N2 worms were allowed to lay embryos on plates covered with E. coli cells producing double-stranded RNA of targeted genes for 2 h. F1 worms were grown on RNAi feeding plates to the L4 stage or 1-day-old adults at 25°C before being treated with DNA damaging agents. In the experiments shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5B–5D), RNAi was performed for 16 h from the L4 stage (instead of the L1 stage) before treatment with HU or IR.

Hydroxyurea Treatment

To observe pCHK1 expression or nuclear morphology, worms were grown from L1 to L4 larvae on RNAi feeding plates at 25°C. L4 stage worms were transferred to new RNAi feeding plates containing 25 mM hydroxyurea. After 16 h, their gonads were dissected out and immunostained using rabbit-anti-phospho-CHK1(Ser345) antibody. To visualize WRN-1 and RPA-1 expression, worms were grown from L4 larvae to 1-day-old adults (for 16 h) on RNAi feeding plates at 25°C, and then transferred to RNAi feeding plates containing 25 mM hydroxyurea for 8 h. Dissected gonads were immunostained with anti-WRN-1 and anti-RPA1 antisera.

γ - and UV Radiation

Worms were grown from L1 larvae to 1-day-old adults at 25°C on RNAi feeding plates (except for Figure 5B–5D, where RNAi was performed from the L4 stage for 16 h). They were γ-irradiated (75 Gy) using a 137Cs source (IBL 437C, CIS Biointernational) or UV-irradiated (100 J/m2) using a CL-1000 UV crosslinker (Ultra-Violet Products). After 1 h, gonads were dissected and immunostained.

Antibody Preparation

Polyclonal antiserum to WRN-1 protein was generated by immunizing mice and rabbits with an amino-terminal WRN-1 fragment corresponding to amino acids 1–209, as described in Lee et al. [19]. The mouse and rabbit anti-WRN-1 polyclonal antibodies were used for immunostaining and Western blot analysis, respectively.

The 1–699 bases of the rpa-1 open reading frame (ORF) were amplified by PCR from EST clone yk787c12 with forward primer 5′-CACCATGGCGGCAATTCACATCAATCAC and reverse primer 5′-TACGTACGGTGTAACCATTGA. An atm-1 cDNA fragment containing 748–1950 nucleotides of the ORF was prepared from EST clone yk444h6 by PCR with forward primer 5′-CACCGAAATTGCAATGCTTGACG and reverse primer 5′-CTACAAAAACGGCATCCAT. The amplicons were subcloned into pENTR/D/TOPO (Invitrogen). The constructs were subsequently cloned into pDEST15 using the Gateway cloning system (Invitrogen). pDEST15 recombinants containing the rpa-1 or atm-1 fragment were transformed into E. coli BL21AI. The E. coli cells were grown at 37°C to an OD600 nm of 0.5 in LB medium containing 100 µg/mL ampicillin. L-arabinose (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to a final concentration of 0.2% (w/v), and the cells were grown for an additional 4 h at 37°C. The overexpressed proteins were used to generate antibodies in rats. Rabbit anti-CHK1(pSer345), mouse anti-α-tubulin, and anti-BrdU antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, and Becton-Dickinson, respectively.

Immunostaining

Gonads were extruded by decapitating adult worms, fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, and immunostained as described [48]. However, to enhance immunostaining of phospho-CHK1 and WRN-1, we used a tyramide signal amplification system (Invitrogen). Gonads were reacted with rabbit anti-CHK1(pSer345) or mouse anti-WRN-1 (1∶50 dilution), followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-goat anti-rabbit (or anti-mouse) IgG at 1∶100 dilution. Alexa Fluor 488 tyramide at 1∶100 dilution was used to detect HRP. Anti-RPA-1 and anti-ATM-1 antisera (1∶50 dilution) were incubated with gonads, which were then reacted with Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rat secondary antibodies (Molecular probes, 1∶1000 dilution). When mouse anti-BrdU antiserum (1∶10 dilution) was used as a primary antibody, Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Molecular Probes) was used as the secondary antibody. After staining with DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, 1 mg/ml), specimens were observed with a fluorescence microscope (DMR HC, Leica).

BrdU Labeling and Immunostaining

To incorporate BrdU into E. coli chromosomal DNA, E. coli MG1693 cells, which are thymidine auxotrophs (from E. coli Genetic Stock Center), were grown overnight in LB containing 10 µg/ml trimethoprim, 0.5 µM thymidine, and 10 µM BrdU, as described by Ito and McGhee [49]. C. elegans chromosomal DNA was labeled with BrdU by culturing hermaphrodites for 30 min on NGM plates seeded with BrdU-labeled E. coli cells. Adult worms were treated with γ - or UV radiation and transferred to plates containing unlabeled E. coli OP50 cells. After 1 h, gonads were extruded, fixed and washed, and then soaked in 2 N HCl for 15 min at room temperature to denature DNA and expose the BrdU epitope. This was followed by neutralization in 0.1 M sodium tetraborate solution for 15 min at room temperature and double immunostaining for pCHK-1 and BrdU.

Western Blot Analysis

Adult worms were washed off ten NGM plates (dia. 55 mm) with 1×PTW (PBS with 0.1% Tween 20). The pellets were mixed with 2 volumes of 2× sample loading buffer (200 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.4 mM PMSF) and kept in boiling water for 10 min. The lysates were electrophoresed on 8% SDS polyacrylamide gels and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell BioScience). The antibody dilutions were 1∶1000 for phospho-CHK1, WRN-1, and RPA-1, and 1∶10,000 for α-tubulin. Secondary anti-rabbit, anti-mouse or anti-rat HRP (Jackson Bioresearch, 1∶1000 dilution) antibody was used and detected using ECL (Amersham Sciences). Luminescence was captured with a LAS-3000 imaging system (Fujifilm).

Assessment of Cell Cycle Arrest

L4 larvae were treated with 75 Gy of γ-rays, and their gonads were dissected out 12 h later. After staining with DAPI, the gonads were observed using a fluorescence microscope. The cell cycle arrest phenotype was assessed by counting the number of mitotic nuclei present in one focal plane within 75 µm of the distal tip cell.

Measurement of mRNA by quantitative RT-PCR

To determine RNAi efficiency targeting chk-1, mre-11, rpa-1, and atl-1, worms were grown from L4 larvae to 1-day-old adults (for 16 h) on RNAi feeding plates at 25°C (Figure S3A). To test whether atl-1 RNAi indirectly affected the level of chk-1 mRNA, worms were grown from L1 to L4 larvae on the feeding plates at 25°C (Figure S3B). L4 stage worms were transferred to new RNAi feeding plates containing 25 mM hydroxyurea and grown for 16 h (Figure S3B). The worms were washed three times in 1× PTW (PBS with 0.1% Tween 20) to free them of bacteria. RNA extraction and quantitation of relative mRNA levels were performed as described previously [50]. Primers used for amplification (in 5′ to 3′ orientation) were;

chk-1: GGAGAGACAGAATGCTTCG, GACATCCACATTGATCGAG

mre-11: GAGTATGGGACAAGTTTCTGCA, ATCCCTTTTCTTGGATGGAGC

atl-1: TATCCAGAAGCAGGGCAATGG, TTAGAGGGTCGCCATCCAACC

rpa-1: ATGGCGGCAATTCACATCAATCAC, TACGTACGGTGTAACCATTGC

tbb-1 (β-tubulin as a control): TCCTTCTCGGTTGTTCCATC, GGGAATGGAACCATGTTGAC.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. YuCE

OshimaJ

FuYH

WijsmanEM

HisamaF

1996 Positional cloning of the Werner's syndrome gene. Science 272 258 262

2. ShenJ

LoebLA

2001 Unwinding the molecular basis of the Werner syndrome. Mech Ageing Dev 122 921 944

3. OzgencA

LoebLA

2005 Current advances in unraveling the function of the Werner syndrome protein. Mutat Res 577 237 251

4. ChengWH

MuftuogluM

BohrVA

2007 Werner syndrome protein: functions in the response to DNA damage and replication stress in S-phase. Exp Gerontol 42 871 878

5. BohrVA

2008 Rising from the RecQ-age: the role of human RecQ helicases in genome maintenance. Trends Biochem Sci 33 609 620

6. WyllieFS

JonesCJ

SkinnerJW

HaughtonMF

WallisC

2000 Telomerase prevents the accelerated cell ageing of Werner syndrome fibroblasts. Nat Genet 24 16 17

7. ChangS

MultaniAS

CabreraNG

NaylorML

LaudP

2004 Essential role of limiting telomeres in the pathogenesis of Werner syndrome. Nat Genet 36 877 882

8. OpreskoPL

OtterleiM

GraakjaerJ

BruheimP

DawutL

2004 The Werner syndrome helicase and exonuclease cooperate to resolve telomeric D loops in a manner regulated by TRF1 and TRF2. Mol Cell 14 763 774

9. HuangS

LiB

GrayMD

OshimaJ

MianIS

1998 The premature ageing syndrome protein, WRN, is a 3′–>5′ exonuclease. Nat Genet 20 114 116

10. MoserMJ

HolleyWR

ChatterjeeA

MianIS

1997 The proofreading domain of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I and other DNA and/or RNA exonuclease domains. Nucleic Acids Res 25 5110 5118

11. ShenJC

GrayMD

OshimaJ

Kamath-LoebAS

FryM

1998 Werner syndrome protein. I. DNA helicase and dna exonuclease reside on the same polypeptide. J Biol Chem 273 34139 34144

12. SuzukiN

ShiratoriM

GotoM

FuruichiY

1999 Werner syndrome helicase contains a 5′–>3′ exonuclease activity that digests DNA and RNA strands in DNA/DNA and RNA/DNA duplexes dependent on unwinding. Nucleic Acids Res 27 2361 2368

13. ChengWH

von KobbeC

OpreskoPL

ArthurLM

KomatsuK

2004 Linkage between Werner syndrome protein and the Mre11 complex via Nbs1. J Biol Chem 279 21169 21176

14. ChengWH

SakamotoS

FoxJT

KomatsuK

CarneyJ

2005 Werner syndrome protein associates with gamma H2AX in a manner that depends upon Nbs1. FEBS Lett 579 1350 1356

15. FranchittoA

OshimaJ

PichierriP

2003 The G2-phase decatenation checkpoint is defective in Werner syndrome cells. Cancer Res 63 3289 3295

16. ChengWH

MufticD

MuftuogluM

DawutL

MorrisC

2008 WRN is required for ATM activation and the S-phase checkpoint in response to interstrand cross-link-induced DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Biol Cell 19 3923 3933

17. KimbleJ

CrittendenSL

2007 Controls of germline stem cells, entry into meiosis, and the sperm/oocyte decision in Caenorhabditis elegans. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 23 405 433

18. GartnerA

MilsteinS

AhmedS

HodgkinJ

HengartnerMO

2000 A conserved checkpoint pathway mediates DNA damage-induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in C. elegans. Mol Cell 5 435 443

19. LeeSJ

YookJS

HanSM

KooHS

2004 A Werner syndrome protein homolog affects C. elegans development, growth rate, life span and sensitivity to DNA damage by acting at a DNA damage checkpoint. Development 131 2565 2575

20. ClejanI

BoerckelJ

AhmedS

2006 Developmental modulation of nonhomologous end joining in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 173 1301 1317

21. ZhaoH

Piwnica-WormsH

2001 ATR-mediated checkpoint pathways regulate phosphorylation and activation of human Chk1. Mol Cell Biol 21 4129 4139

22. MacQueenAJ

VilleneuveAM

2001 Nuclear reorganization and homologous chromosome pairing during meiotic prophase require C. elegans chk-2. Genes Dev 15 1674 1687

23. GateiM

SloperK

SorensenC

SyljuasenR

FalckJ

2003 Ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) and NBS1-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1 on Ser-317 in response to ionizing radiation. J Biol Chem 278 14806 14811

24. MoserSC

von ElsnerS

BussingI

AlpiA

SchnabelR

2009 Functional dissection of Caenorhabditis elegans CLK-2/TEL2 cell cycle defects during embryogenesis and germline development. PLoS Genet 5 e1000451 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000451

25. CrittendenSL

LeonhardKA

ByrdDT

KimbleJ

2006 Cellular analyses of the mitotic region in the Caenorhabditis elegans adult germ line. Mol Biol Cell 17 3051 3061

26. Garcia-MuseT

BoultonSJ

2005 Distinct modes of ATR activation after replication stress and DNA double-strand breaks in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J 24 4345 4355

27. CortezD

GuntukuS

QinJ

ElledgeSJ

2001 ATR and ATRIP: partners in checkpoint signaling. Science 294 1713 1716

28. HyunM

BohrVA

AhnB

2008 Biochemical characterization of the WRN-1 RecQ helicase of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochemistry 47 7583 7593

29. BjergbaekL

CobbJA

Tsai-PflugfelderM

GasserSM

2005 Mechanistically distinct roles for Sgs1p in checkpoint activation and replication fork maintenance. EMBO J 24 405 417

30. AhmedS

AlpiA

HengartnerMO

GartnerA

2001 C. elegans RAD-5/CLK-2 defines a new DNA damage checkpoint protein. Curr Biol 11 1934 1944

31. GartnerA

BoagPR

BlackwellTK

2008 Germline survival and apoptosis. WormBook 1 20

32. StergiouL

HengartnerMO

2004 Death and more: DNA damage response pathways in the nematode C. elegans. Cell Death Differ 11 21 28

33. DohertyKM

SommersJA

GrayMD

LeeJW

von KobbeC

2005 Physical and functional mapping of the replication protein a interaction domain of the werner and bloom syndrome helicases. J Biol Chem 280 29494 29505

34. SidorovaJM

LiN

FolchA

MonnatRJJr

2008 The RecQ helicase WRN is required for normal replication fork progression after DNA damage or replication fork arrest. Cell Cycle 7 796 807

35. ByunTS

PacekM

YeeMC

WalterJC

CimprichKA

2005 Functional uncoupling of MCM helicase and DNA polymerase activities activates the ATR-dependent checkpoint. Genes Dev 19 1040 1052

36. Unsal-KacmazK

MakhovAM

GriffithJD

SancarA

2002 Preferential binding of ATR protein to UV-damaged DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 6673 6678

37. StergiouL

DoukoumetzidisK

SendoelA

HengartnerMO

2007 The nucleotide excision repair pathway is required for UV-C-induced apoptosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Death Differ 14 1129 1138

38. LanL

NakajimaS

KomatsuK

NussenzweigA

ShimamotoA

2005 Accumulation of Werner protein at DNA double-strand breaks in human cells. J Cell Sci 118 4153 4162

39. GravelS

ChapmanJR

MagillC

JacksonSP

2008 DNA helicases Sgs1 and BLM promote DNA double-strand break resection. Genes Dev 22 2767 2772

40. SartoriAA

LukasC

CoatesJ

MistrikM

FuS

2007 Human CtIP promotes DNA end resection. Nature 450 509 514

41. SchaetzleinS

KodandaramireddyNR

JuZ

LechelA

StepczynskaA

2007 Exonuclease-1 deletion impairs DNA damage signaling and prolongs lifespan of telomere-dysfunctional mice. Cell 130 863 877

42. ShiotaniB

ZouL

2009 Single-stranded DNA orchestrates an ATM-to-ATR switch at DNA breaks. Mol Cell 33 547 558

43. NimonkarAV

OzsoyAZ

GenschelJ

ModrichP

KowalczykowskiSC

2008 Human exonuclease 1 and BLM helicase interact to resect DNA and initiate DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 16906 16911

44. JazayeriA

FalckJ

LukasC

BartekJ

SmithGC

2006 ATM - and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol 8 37 45

45. RichardDJ

BoldersonE

CubedduL

WadsworthRI

SavageK

2008 Single-stranded DNA-binding protein hSSB1 is critical for genomic stability. Nature 453 677 681

46. BrennerS

1974 The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 71 94

47. TimmonsL

FireA

1998 Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature 395 854

48. JonesAR

FrancisR

SchedlT

1996 GLD-1, a cytoplasmic protein essential for oocyte differentiation, shows stage - and sex-specific expression during Caenorhabditis elegans germline development. Dev Biol 180 165 183

49. ItoK

McGheeJD

1987 Parental DNA strands segregate randomly during embryonic development of Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell 49 329 336

50. ParkJE

LeeKY

LeeSJ

OhWS

JeongPY

2008 The efficiency of RNA interference in Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Mol Cells 26 81 86

51. StiffT

WalkerSA

CerosalettiK

GoodarziAA

PetermannE

2006 ATR-dependent phosphorylation and activation of ATM in response to UV treatment or replication fork stalling. EMBO J 25 5775 5782

52. KalogeropoulosN

ChristoforouC

GreenAJ

GillS

AshcroftNR

2004 chk-1 is an essential gene and is required for an S-M checkpoint during early embryogenesis. Cell Cycle 3 1196 1200

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Activation of Mutant Enzyme Function by Proteasome Inhibitors and Treatments that Induce Hsp70Článek Maternal Ethanol Consumption Alters the Epigenotype and the Phenotype of Offspring in a Mouse ModelČlánek Genetic Dissection of Differential Signaling Threshold Requirements for the Wnt/β-Catenin PathwayČlánek Distinct Type of Transmission Barrier Revealed by Study of Multiple Prion Determinants of Rnq1

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2010 Číslo 1- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Irradiation-Induced Genome Fragmentation Triggers Transposition of a Single Resident Insertion Sequence

- A Major Role of the RecFOR Pathway in DNA Double-Strand-Break Repair through ESDSA in

- Kidney Development in the Absence of and Requires

- Modeling of Environmental Effects in Genome-Wide Association Studies Identifies and as Novel Loci Influencing Serum Cholesterol Levels

- Inverse Correlation between Promoter Strength and Excision Activity in Class 1 Integrons

- Activation of Mutant Enzyme Function by Proteasome Inhibitors and Treatments that Induce Hsp70

- Postnatal Survival of Mice with Maternal Duplication of Distal Chromosome 7 Induced by a / Imprinting Control Region Lacking Insulator Function

- The Werner Syndrome Protein Functions Upstream of ATR and ATM in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition and Double-Strand DNA Breaks

- Maternal Ethanol Consumption Alters the Epigenotype and the Phenotype of Offspring in a Mouse Model

- Understanding Gene Sequence Variation in the Context of Transcription Regulation in Yeast

- miR-30 Regulates Mitochondrial Fission through Targeting p53 and the Dynamin-Related Protein-1 Pathway

- Elevated Levels of the Polo Kinase Cdc5 Override the Mec1/ATR Checkpoint in Budding Yeast by Acting at Different Steps of the Signaling Pathway

- Alternative Epigenetic Chromatin States of Polycomb Target Genes

- Co-Orientation of Replication and Transcription Preserves Genome Integrity

- A Comprehensive Map of Insulator Elements for the Genome

- Environmental and Genetic Determinants of Colony Morphology in Yeast

- U87MG Decoded: The Genomic Sequence of a Cytogenetically Aberrant Human Cancer Cell Line

- The MCM-Binding Protein ETG1 Aids Sister Chromatid Cohesion Required for Postreplicative Homologous Recombination Repair

- Genetic Dissection of Differential Signaling Threshold Requirements for the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway

- Differential Localization and Independent Acquisition of the H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 Chromatin Modifications in the Adult Germ Line

- Genetic Crossovers Are Predicted Accurately by the Computed Human Recombination Map

- Collaborative Action of Brca1 and CtIP in Elimination of Covalent Modifications from Double-Strand Breaks to Facilitate Subsequent Break Repair

- Distinct Type of Transmission Barrier Revealed by Study of Multiple Prion Determinants of Rnq1

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies as a Novel Susceptibility Gene for Osteoporosis

- and Regulate Reproductive Habit in Rice

- Nonsense-Mediated Decay Enables Intron Gain in

- Altered Gene Expression and DNA Damage in Peripheral Blood Cells from Friedreich's Ataxia Patients: Cellular Model of Pathology

- The Systemic Imprint of Growth and Its Uses in Ecological (Meta)Genomics

- The Gift of Observation: An Interview with Mary Lyon

- Genotype and Gene Expression Associations with Immune Function in

- The Elongator Complex Regulates Neuronal α-tubulin Acetylation

- Rising from the Ashes: DNA Repair in

- Mis-Spliced Transcripts of Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor α6 Are Associated with Field Evolved Spinosad Resistance in (L.)

- BRIT1/MCPH1 Is Essential for Mitotic and Meiotic Recombination DNA Repair and Maintaining Genomic Stability in Mice

- Non-Coding Changes Cause Sex-Specific Wing Size Differences between Closely Related Species of

- Evidence for Pervasive Adaptive Protein Evolution in Wild Mice

- Evolutionary Mirages: Selection on Binding Site Composition Creates the Illusion of Conserved Grammars in Enhancers

- VEZF1 Elements Mediate Protection from DNA Methylation

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- A Major Role of the RecFOR Pathway in DNA Double-Strand-Break Repair through ESDSA in

- Kidney Development in the Absence of and Requires

- The Werner Syndrome Protein Functions Upstream of ATR and ATM in Response to DNA Replication Inhibition and Double-Strand DNA Breaks

- Alternative Epigenetic Chromatin States of Polycomb Target Genes

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy