-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Phosphate Flow between Hybrid Histidine Kinases CheA and CheS Controls Cyst Formation

Genomic and genetic analyses have demonstrated that many species contain multiple chemotaxis-like signal transduction cascades that likely control processes other than chemotaxis. The Che3 signal transduction cascade from Rhodospirillum centenum is one such example that regulates development of dormant cysts. This Che-like cascade contains two hybrid response regulator-histidine kinases, CheA3 and CheS3, and a single-domain response regulator CheY3. We demonstrate that cheS3 is epistatic to cheA3 and that only CheS3∼P can phosphorylate CheY3. We further show that CheA3 derepresses cyst formation by phosphorylating a CheS3 receiver domain. These results demonstrate that the flow of phosphate as defined by the paradigm E. coli chemotaxis cascade does not necessarily hold true for non-chemotactic Che-like signal transduction cascades.

Published in the journal: Phosphate Flow between Hybrid Histidine Kinases CheA and CheS Controls Cyst Formation. PLoS Genet 9(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004002

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004002Summary

Genomic and genetic analyses have demonstrated that many species contain multiple chemotaxis-like signal transduction cascades that likely control processes other than chemotaxis. The Che3 signal transduction cascade from Rhodospirillum centenum is one such example that regulates development of dormant cysts. This Che-like cascade contains two hybrid response regulator-histidine kinases, CheA3 and CheS3, and a single-domain response regulator CheY3. We demonstrate that cheS3 is epistatic to cheA3 and that only CheS3∼P can phosphorylate CheY3. We further show that CheA3 derepresses cyst formation by phosphorylating a CheS3 receiver domain. These results demonstrate that the flow of phosphate as defined by the paradigm E. coli chemotaxis cascade does not necessarily hold true for non-chemotactic Che-like signal transduction cascades.

Introduction

Rhodospirillum centenum is a photosynthetic member of the Azospirillum clade, members of which associate with root rhizospheres in a broad range of plants. These aerobic nitrogen fixating organisms are capable of promoting plant growth by the donation of both fixed nitrogen and plant hormones [1]. Inoculating fields and/or seeds with Azospirillum sp. have significantly enhanced crop yields of a wide diversity of cultivars including corn and wheat [2], [3]. An additional feature of this group is the capability of forming metabolically dormant cysts that promotes survival during droughts [4]. Encystment involves several morphological transitions during which cells round up and form a thick outer exopolysaccharide coat termed the exine layer [5]. The formation of cysts also correlates with the appearance of intracellular poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) granules that are presumably used as energy reserves [6]. Once water and nutrients are available, cysts germinate by reforming vegetative cells that emerge from the exine coat [5].

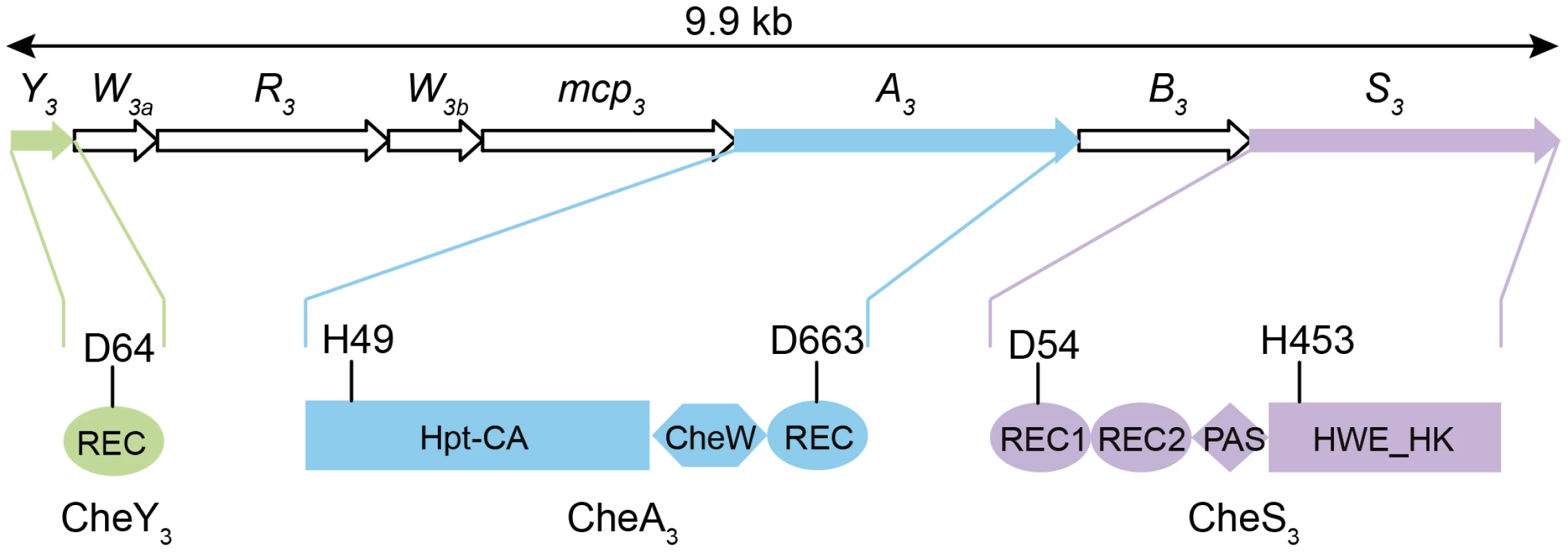

Azospirillum species are morphologically similar to myxospores synthesized by Myxobacteria. Both groups are soil-dwelling, Gram-negative proteobacteria that form highly desiccation resistant resting cells. In Myxococcus xanthus a two-component system (TCS) comprised of a membrane bound histidine kinase (HK) CrdS, which phosphorylates a DNA binding response regulator (RR) CrdA to control myxospore development. The Che-like Che3 signaling cascade negatively regulates CrdA by functioning as a phosphatase [7]. As is the case with Myxobacteria, cyst formation in R. centenum also utilizes a novel chemotaxis-like signal transduction cascade (Che3) to control the timing of development [8]. The R. centenum che3 gene cluster (Figure 1) is comprised of eight genes coding for homologs of CheA (CheA3), CheW (CheW3a and CheW3b), CheB (CheB3), CheR (CheR3), a methyl-accepting chemorecepter (MCP3) and CheY (CheY3). CheA3 is a CheA-CheY hybrid (Figure 1) belonging to Class II HKs, which include homologs of the E. coli CheA with a conserved histidine residue located in a histidine phosphotransfer (Hpt) domain rather than a dimerization and hisitidine phosphotransfer (DHp) domain found in Class I HKs. In addition to CheA3, the che3 cluster also codes for a second HK (CheS3). CheS3 has two REC domains followed by a PAS (Per, Arnt, Sim) domain and a HWE Class I HK domain (Figure 1); however, only one of the CheS3 REC domains contains a predicted phosphorylatable aspartate (D54 in REC1, Figure 1) with the comparable position in the second REC being substituted by an alanine (A191 in REC2, Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Gene arrangement of the R. centenum che3 cluster and domain organizations of CheA3, CheS3, and CheY3.

Arrow length is proportional to gene length. Abbreviations: REC, receiver domain; PAS, Per, Arnt, Sim domains; HWE_HK, HWE superfamily of histidine kinases; Hpt, histidine phosphotransfer domain; CA, catalytic and ATP-binding domain. Conserved histidine and aspartate residues as putative phosphorylation sites are denoted for each protein. The start and end amino acid positions of the receiver domains as well as those of the full proteins are also labeled according to the prediction by SMART [48]. Clearly the presence of a second HK and two additional phosphorylatable REC domains in the R. centenum Che3 cascade indicates that the flow of phosphate is more complex in this signaling pathway than for the E. coli Che signaling cascade. In the classic Escherichia coli chemotaxis model, CheA is tethered to the MCP-CheW complex and its autophosphorylation at a conserved His in the Hpt domain is enhanced upon repellents binding to MCP and inhibited upon binding of attractants. CheA phosphorylates a conserved Asp in CheY; phosphorylated CheY in turn binds to the flagellum's rotor causing reversal of flagellar rotation. Similar to the smooth-swimming and tumbling phenotypes exhibited in E. coli chemotaxis mutants, in-frame deletions of individual che3 genes produce distinctly opposing phenotypes [8]. Deletions of cheS3, cheY3, or cheB3 lead to a hyper-cyst phenotype characterized by premature formation of cysts, whereas null mutants of mcp3, cheW3a, cheW3b, cheR3, or cheA3 produce hypo-cyst strains that are defective for cyst development [8]. These genetic studies indicate that CheS3 and CheY3 may constitute cognate partners in a TCS that suppresses encystment, and that CheA3 either inhibits phosphorylation of the CheS3-CheY3 TCS or is part of a separate pathway. Here we report that CheY3 indeed accepts phosphates from CheS3 and not CheA3, and that CheA3 derepresses cyst formation by phosphorylating the REC1 domain of CheS3.

Results

Mutations in cheA3, cheS3 and cheY3 lead to defects in cyst formation

We previously reported that deletions of hybrid histidine kinase (HHK) genes cheA3 and cheS3 lead to opposing defects in the timing of cyst formation [8]. Specifically, a deletion of cheA3 resulted in severely defective encystment, while a deletion of cheS3 resulted in enhanced encystment. We also observed that a cheY3 null mutation is indistinguishable from the hypercyst phenotype exhibited by a null mutation of cheS3. In order to further probe the importance of the linked CheA3 and CheS3 REC domains we introduced alanine substitutions at the predicted Asp sites of phosphorylation and recombined these mutations into the native R. centenum chromosomal loci (Figure 1). Mutated strains were subsequently assayed for cyst development by growth on either nutrient-rich CENS medium that promotes vegetative growth or on cyst-inducing CENBA medium. Phase contrast microscopy was then used to visually assess cyst production coupled with flow cytometry quantitation of vegetative/cyst cell populations (Figure 2).

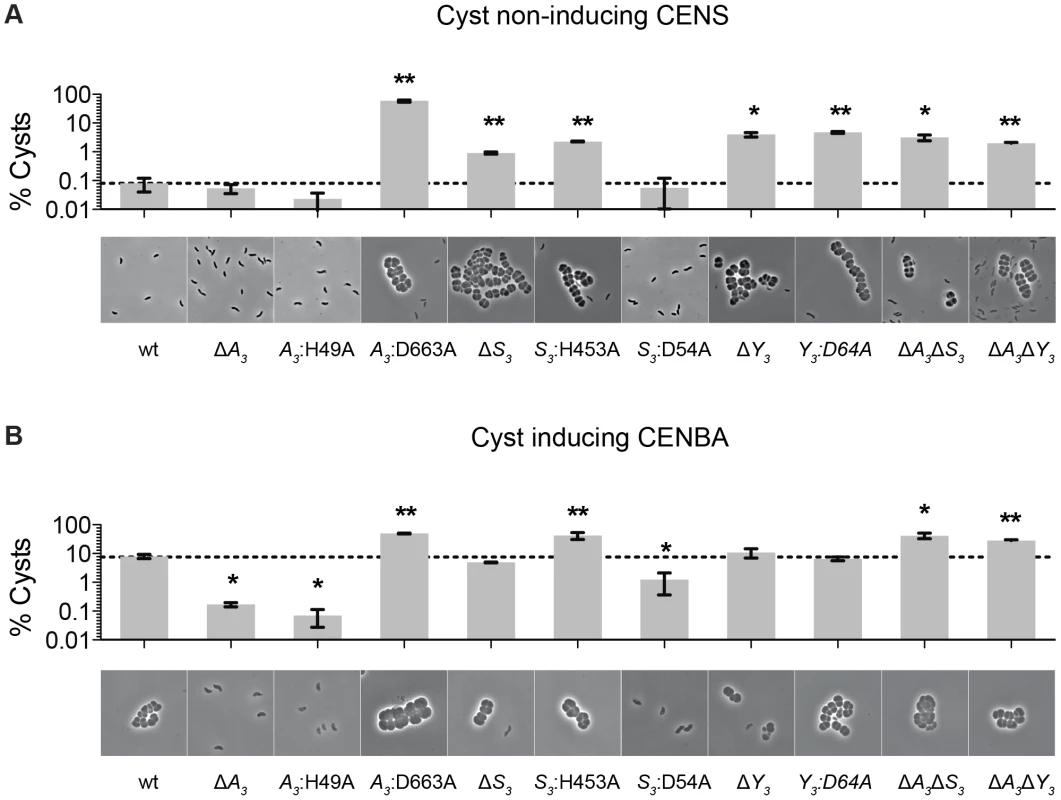

Fig. 2. Characterization of cheS3, cheA3 and cheY3 mutants.

The encystment phenotypes of 11 strains including wild type and single, double, and point mutants of cheS3, cheA3 and cheY3 were measured qualitatively by phase contrast microscopy and quantitatively by flow cytometry. (A) Growth on nutrient-rich CENS medium reveals hyper-cyst strains that overproduce cysts relative to wild type. (B) Growth on nutrient-limiting CENBA medium identifies hypo-cyst strains that under-produce cyst cells relative to wild type. Error bars in the bar graphs represent standard deviation obtained from two biological replicates. * (p<0.05), ** (p<0.01) when compared to the wild type (wt) strain in an unpaired t-test. As observed in previous studies, growth of wild type cells in CENS medium visibly leads to >99% vegetative cells (Figure 2A), whereas growth in CENBA medium produces large cyst clusters (Figure 2B). Separation of individual vegetative cells from cyst clusters using flow cytometry indicates that the large population of vegetative cells present in CENS medium form a tight pattern near the origin of a side scatter (SSC) versus forward scatter (FSC) flow cytometry plot (Figure S1). In contrast, wild type cells grown in CENBA medium, which microscopically have a large number of cysts clusters, shows a distinct “comet tail” comprised of larger cyst cells that separate from the tight clustering of smaller single vegetative cells during flow cytometry (Figure S1). The tight clustering of vegetative cells is indicative of a high degree of uniformity of cell size (∼1 µm) [9] and internal complexity whereas the “comet tail” distribution of the cyst cell population shows that there is a wider distribution of sizes (2–8 µm) [10] present with varying internal complexity due in part to varying numbers and sizes of large PHB storage granules inside cysts [10], [11]. Because each cyst cluster typically contains 2 to 6 cells, the number of cyst cells is significantly higher (estimated to be ∼4-fold higher) than what is measured by flow cytometry quantitation of cyst clusters.

Flow cytometry analysis of wild type cells grown on cyst inducing CENBA medium show that ∼10% of the cell culture can be separated from the vegetative cell population as larger cyst clusters (Figure 2B). In contrast, growth of the ΔcheA3 mutant in cyst inducing CENBA shows a two-log reduction in cyst formation (Figure 2B) to a level that is comparable with that of wild type cells growth in vegetative CENS medium (Figure 2A). Not surprisingly, the cheA3:H49A HK mutant resembles a ΔcheA3 mutant, as this strain also contains a large predominance of vegetative cells irrespective of growth on nutrient-rich CENS or cyst-inducing CENBA medium. Interestingly, the cheA3:D663A REC mutant exhibits an opposing phenotype in that it forms large numbers of cysts in both CENS and CENBA growth media (Figure 2). Indeed the level of cyst production by the cheA3:D663A REC mutant exceeds that of wild type cells grown in CENBA.

The cyst deficient phenotypes exhibited by the ΔcheA3 and cheA3:H49A mutants are markedly contrasted by the ΔcheS3 and cheS3:H453A HK mutant strains that produce cysts in both CENS and CENBA medium. Interestingly, similar to what was observed in the CheA3 HK and REC mutant strains, the cheS3:D54A REC mutant exhibits a cyst defective phenotype that is opposite of the hypercyst phenotype exhibited by the ΔcheS3 and cheS3:H453A HK mutant strains (Figure 2). The opposing encystment phenotypes produced by the cheA3 and cheS3 HK and REC domain mutations indicates that the REC domains have regulatory control over the linked HK domains in both kinases. Similar to the ΔcheS3 and cheS3:H453A mutants, both the ΔcheY3, and cheY3:D64A mutants produced cyst cells when grown in both vegetative CENS and cyst inducing CENBA growth media (Figure 2).

Finally, to determine the hierarchy of CheA3 and CheS3 within the Che3 signaling cascade, we constructed ΔcheA3ΔcheS3 and ΔcheA3ΔcheY3 double mutants and assayed for encystment. These double mutations resulted in hyper-cyst strains that resemble the ΔcheS3 and ΔcheY3 phenotypes (Figure 2), suggesting that CheA3 functions upstream of CheS3 and CheY3 in this developmental signaling pathway.

Divalent metal cation dependencies to address intramolecular phosphate flow within CheA3

HHKs are generally able to undergo four reactions in the presence of ATP and divalent metal cations: (1) autophosphorylation, where the conserved His residue within the HK domain is phosphorylated by the adjacent catalytic and ATP-binding domain (CA) using ATP as a substrate; (2) autodephosphorylation of the phospho-His residue within the HK domain; (3) phosphotransfer, where the REC domain dephosphorylates phospho-His and transfers the phosphate to its conserved Asp; and (4) autodephosphorylation of the phospho-Asp residue within the REC domain to yield inorganic phosphates (Pi) (Figure S2). In addition, phosphoryl group transfer from a response regulator back to its cognate HK is also possible. This reverse reaction has been observed in the EnvZ-OmpR TCS [12] as well as in phosphorelay systems involving a Hpt domain where the forward phosphorylation reaction (His1→Asp1→His2→Asp2) is partially reversible (Asp2→His2→Asp1→Pi) [13]. In the presence of ATP, HHKs may therefore exist as a mixture of four different phosphorylation states as illustrated in Figure 3A: unphosphorylated, His-phosphorylated (His∼P), Asp-phosphorylated (Asp∼P), and His-and-Asp-phosphorylated (His∼P/Asp∼P).

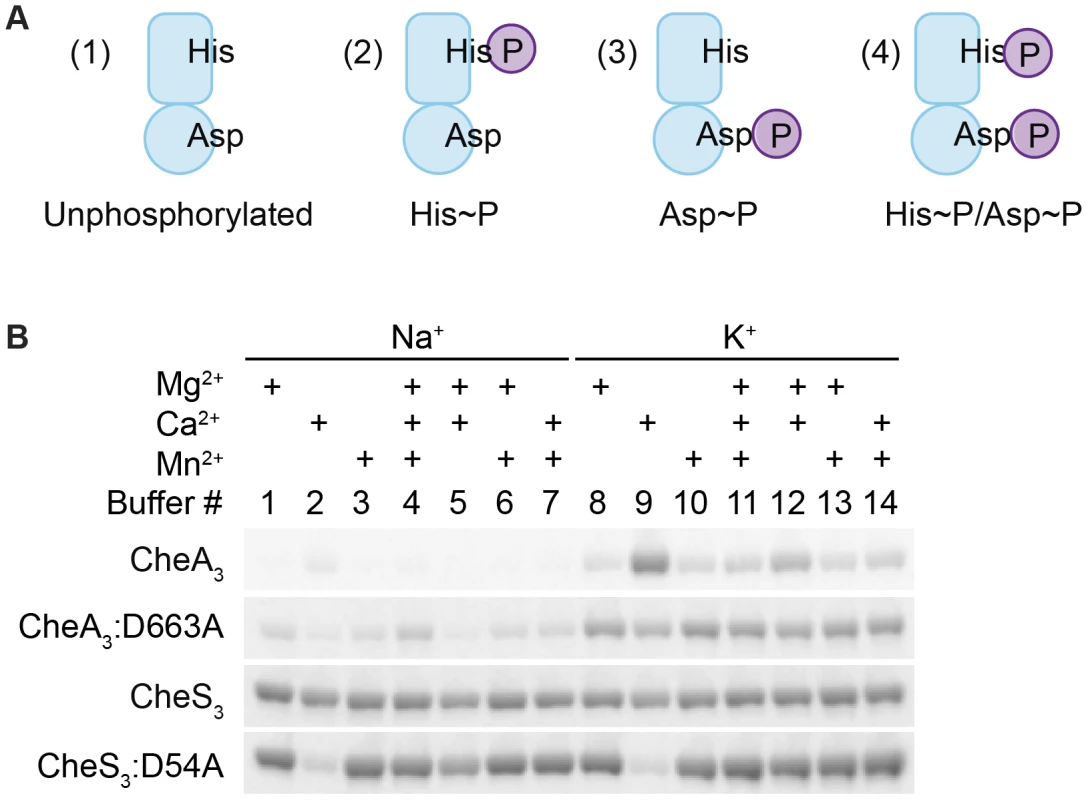

Fig. 3. Metal ion dependent phosphorylation of CheA3 and CheS3.

(A) Four possible phosphorylation states of phosphorylated hybrid histidine kinases (HHKs). (B) Metal cation dependencies of phosphorylation of isolated HHKs CheS3 and CheA3 and their receiver domain mutants. In order to characterize potential phosphorylation states of wild type CheA3 and CheS3, we isolated CheA3 and CheS3 with hexahistidine tags at their N-termini and performed in vitro phosphorylation assays. In early experiments we observed little radioactive labeling on CheA3 with [γ-33P] ATP in buffers containing Na+ and Mg2+, which made it difficult to biochemically characterize CheA3. Earlier studies showed that potassium but not sodium stimulates autophosphorylation of E. coli CheA [14]. Additionally, the Salmonella typhimurium CheY∼P autodephosphorylates at a high rate in the presence of Mg2+ leading to a low amount of 32P protein labeling, whereas in the presence of Ca2+ autodephosphorylation is impeded leading to a high level of 32P labeling [15]. To test whether different metal ions affected HHK phosphorylation, we performed kinase assays on wild type CheA3, CheS3 and on CheA3, CheS3 REC domain mutants in 14 buffers containing 25 mM Tris pH 7.5 and varying in 100 mM monovalent and 6 mM total divalent salt compositions (Table S1, Buffers 1–14). As shown in Figure 3B, CheA3 exhibited nearly undetectable labeling in Buffers 1 and 3–7, all of which contain NaCl as a monovalent salt. CheA3 labeled considerably better in all K+-containing buffers with maximum labeling observed in Buffer 9 containing Ca2+ as the sole divalent ion. When D663 was replaced with an alanine, 33P labeling was greatly improved in nearly all buffer conditions (Figure 3B). The enhanced labeling of CheA3:D663A compared with wild type CheA3 suggests that the N-terminal HK domain transfers the phosphate to D663 in the REC domain, which subsequently undergoes rapid autodephosphorylation. The D663A REC domain mutation would thus effectively trap the phosphate at H49, thereby allowing increased accumulation of phosphates. Regarding the enhanced phosphorylation of wild type CheA3 observed in Buffer 9, we propose that phosphate is captured at both H49 and D663 residues due to Ca2+ mediated inhibition of receiver domain autodephosphorylation. This conclusion is further supported by acid-base stability assays described below. Unlike CheA3, CheS3 shows no particular metal ion preference (Figure 3B). CheS3:D54A exhibits much lower 33P incorporation in Buffers 2 and 9, which contain Ca2+ as the only divalent metal ion.

CheA3 undergoes intramolecular phosphotransfer between HK and REC domains

HHKs are found in most bacterial genomes [16] with the role of the linked REC domain not well established in most cases. However, in several studies it has been shown that the HK domain favors intramolecular phosphotransfer to the linked REC domain [17]–[19]. We tested whether intramolecular phosphotransfer occurs in CheA3 and CheS3 by determining the phosphorylation states of the HK and REC domains. To capture the His∼P, Asp∼P, and His∼P/Asp∼P forms of these phospho-kinases, we used an acid-base stability assay based on differential pH sensitivity of His and Asp phosphorylated residues. Specifically, His∼P (Figure 3A-2) bonds are labile in acidic conditions but stable in basic conditions [20] while acylphosphates like Asp∼P (Figure 3A-3) are both acid - and base-labile [21].

In this experiment, we phosphorylated CheA3 and CheS3 in Buffer 9 (containing Ca2+ as the only divalent cation) for 30 min, denatured the phospho-proteins with SDS and treated samples with Tris buffer, HCl, or NaOH. Samples were then assayed for 33P-labeling by SDS-PAGE, with the assumption being that phosphorylation is preserved in a buffered solution with a physiological pH (Tris pH 7.5) and thus would represent 100% phosphorylation of the kinases before acid or base treatment.

In Figure 4A we show that ∼50% of wild type CheA3∼P was hydrolyzed by exposure to 0.1 M HCl and that it increased to ∼90% hydrolysis by exposure to 1 M HCl. This is contrasted by >90% hydrolysis of phosphate observed with the mutant (CheA3:D663A∼P) in both low and high HCl concentrations. The different stability profiles of the wild type CheA3 and D663A mutant suggest that Asp∼P likely exists in the wild type CheA3∼P. This is confirmed by treatment with NaOH, which dephosphorylates only Asp∼P. In this case nearly 100% CheA3:D663A∼P withstood high pH while the phosphate on wild type CheA3 is extremely labile (Figure 4A). This demonstrates that CheA3:D663A∼P is indeed only phosphorylated on a His residue and that wild type CheA has the majority (>90%) of its phosphate located at D663. Collectively these data suggest that the phosphate group flows from the HK domain to the REC domain within wild type CheA3. This conclusion is also confirmed by observing direct transfer of phosphate from CheA3:D663A∼P to a truncated version of CheA3 comprised of only the C-terminal receiver domain (CheA3-REC) (Figure 4C). Intermolecular phosphoryl transfer to CheA3-REC was also detected using the wild type CheA3∼P as the donor (Figure S3A) that has a linked REC domain competing with intermolecular phosphoryl transfer to the truncated REC domain.

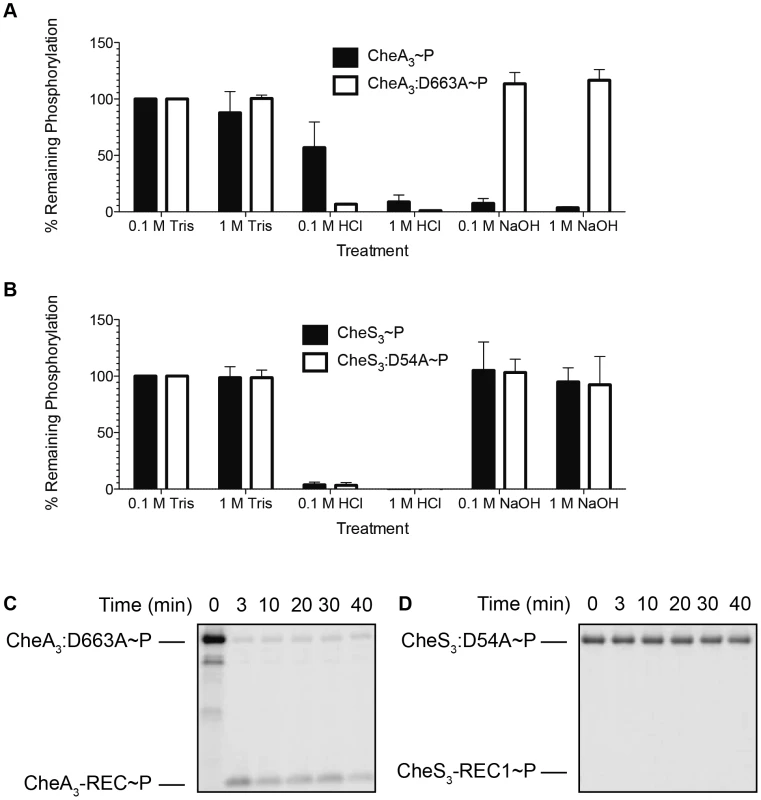

Fig. 4. Identification of intramolecular phosphoryl transfer within CheA3 and CheS3.

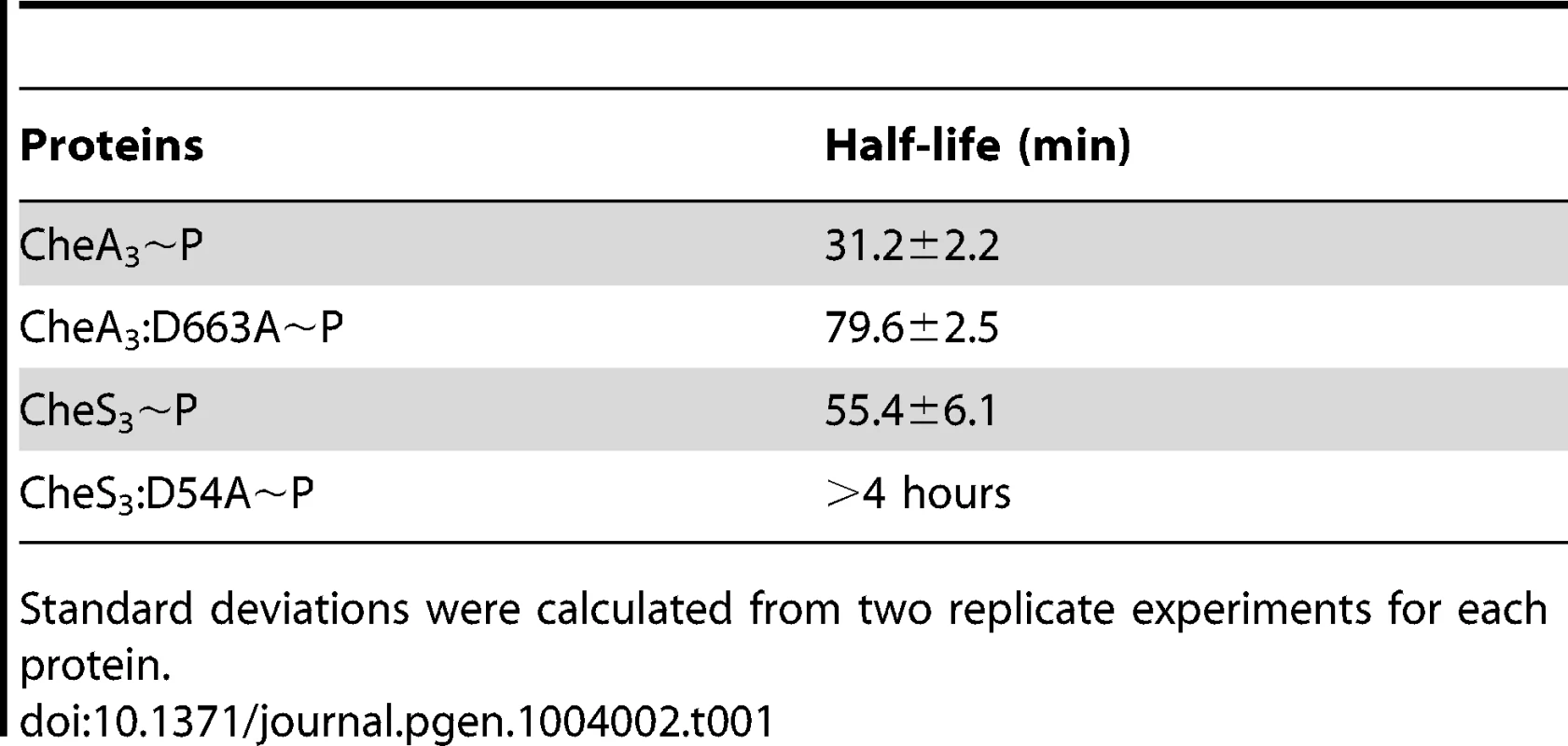

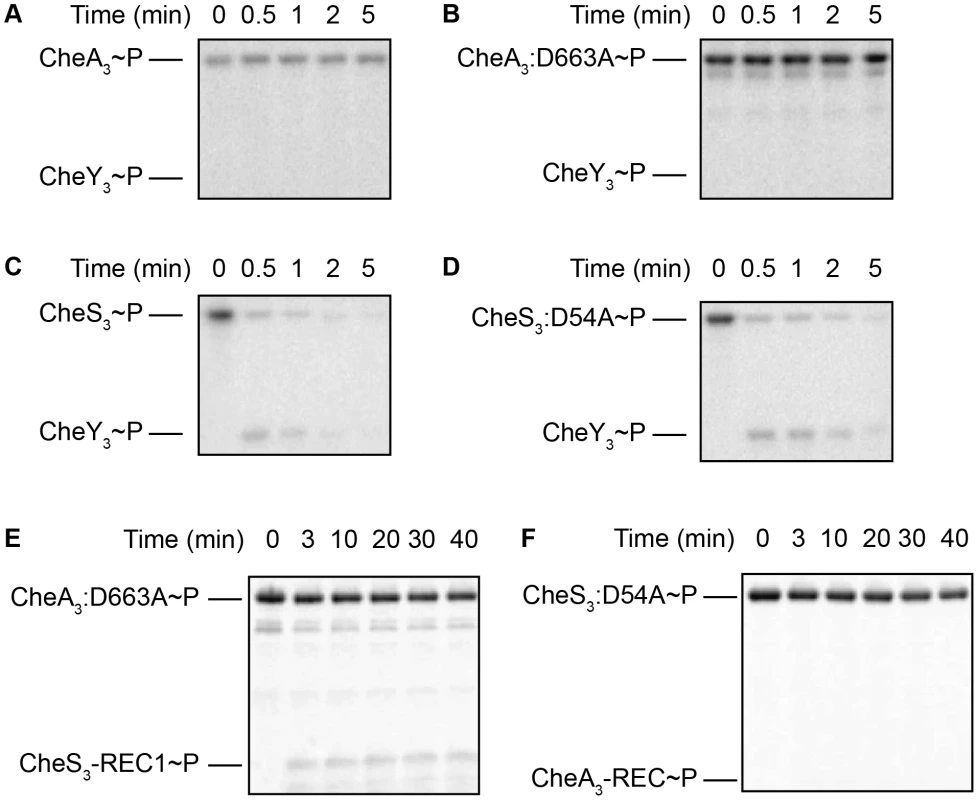

(A) CheA3∼P is acid- and alkaline-labile, whereas the REC mutant CheA3:D663A∼P is acid-labile and base-resistant. (B) Both CheS3∼P and its REC mutant CheS3:D54A are acid-labile and alkaline-stable. (C) CheA3:D663A∼P phosphorylates CheA3-REC truncation protein in Buffer 15 containing K+ and 18 mM Mg2+. (D) Phosphoryl transfer from CheS3:D54A∼P to CheS3-REC1 truncation protein was not observed in Buffer 15. Tethered receiver domains in HHKs can either function as an intermediate within a multicomponent phosphorylation cascade, or as a phosphate sink, removing phosphate from the HK domain to impede it from phosphorylating an untethered cognate REC domain. We believe the latter is the case with CheA3 as the half-life of the phosphate on the CheA3:D663A mutant is nearly 3-fold higher (80 min, Table 1) than is observed with wild type CheA3 (31 min, Table 1). Taken together, it appears that the REC domain in CheA3 functions to modulate the phosphorylation state of the HK domain by accepting a phosphate that is then rapidly lost by hydrolysis.

Tab. 1. Half-lives of phospho-HHKs.

Standard deviations were calculated from two replicate experiments for each protein. In contrast to the acid and base stability of CheA3, CheS3∼P is only acid-labile (Figure 4B). Furthermore, substitution of the predicted D54 phosphorylation site to an alanine in the first REC domain does not alter pH sensitivity. These results indicate that His∼P (Figure 3A-2) is the primary autophosphorylation form of CheS3∼P. Because CheS3:D54A showed reduced 33P incorporation in Buffer 9 (Figure 3B), we repeated this assay with CheS3∼P and CheS3:D54A∼P prepared in Buffer 5 (containing both Ca2+ and Mg2+) in order to rule out any ion effects imparted upon the phosphorylation equilibriums discussed above (Figure S2). We observed the same results of high HCl sensitivity and NaOH resistance regardless of the buffer conditions (Figure S4). In agreement with this conclusion, no phosphoryl transfer was detected from CheS3∼P to a truncated version of CheS3 comprised of only the N-terminal CheS3-REC1 domain (Figure 4D). Interestingly, despite evidence against CheS3 intramolecular phosphoryl transfer, the >4 hour stability of CheS3:D54A∼P is substantially greater than the 55 min stability observed with CheS3∼P (Table 1) suggesting that D54 may play a role in promoting autodephosphorylation of the HK domain.

CheS3 phosphorylates CheY3

Based on the CheA-CheY paradigm from E. coli, we tested the ability of CheA3 to phosphorylate CheY3. In our assays CheA3∼P and the more stable CheA3:D663A∼P mutant did not exhibit any detectable ability to transfer a phosphate to CheY3 (Figure 5A, 5B) in Buffer 9. Since the E. coli CheY and other response regulators exhibit a wide range of binding affinities to divalent metals (Kd of 0.4–47 mM under pH 6.0–10.0 have been reported [15], [22]–[24]), we also assayed CheA3 phosphorylation of CheY3 in Buffers 15–21 with higher (18 mM) total divalent metal concentrations (Table S1). This assay condition also failed to obtain phosphoryl transfer from CheA3∼P or CheA3:D663A∼P to CheY3 (Figure S5).

Fig. 5. Intermolecular phosphoryl transfer events assayed among CheS3, CheA3, and CheY3.

2–5 µM CheS3, CheA3, or their REC mutant forms were autophosphorylated in 200 µM ATP for 30 min before 1/10 volumes of 65 mM CheY3 or REC domain truncations were added. (A, B) Neither CheA3∼P nor CheA3:D663A∼P are able to phosphorylate CheY3 in Buffer 9 containing K+ and 6 mM Ca2+. (C, D) CheS3∼P and CheS3:D54A∼P phosphorylates CheY3 within 15 sec of CheY3 addition in Buffer 5 containing Na+, 3 mM Ca2+, and 3 mM Mg2+. (E) Intermolecular phosphoryl transfer analyses of CheA3 and CheS3. (A) CheA3:D663A∼P phosphorylates CheS3-REC1 in Buffer 15 containing K+ and 18 mM Mg2+. (F) CheS3 is unable to phosphorylate CheA3-REC in Buffer 15. In contrast to the hypo-cyst phenotype exhibited by null mutation of cheA3, null mutations in cheS3 and cheY3 both exhibit indistinguishable hyper-cyst phenotypes (Figure 2) indicating that CheS3 might be the cognate kinase of CheY3. To test whether CheS3 can phosphorylate CheY3 we phosphorylated CheS3 for 30 min and then added CheY3. Upon addition of CheY3, rapid phosphoryl transfer from CheS3∼P to CheY3 was observed within 30 sec (Figure 5C). We also observed that CheS3:D54A is capable of phosphorylating CheY3 (Figure 5D) and that the H453A point mutation renders CheS3 unable to autophosphorylate (Figure S6). Thus, the phosphoryl group appears to transfer directly from H453 from CheS3 to CheY3. We also note that CheY3 appears to have a fast autodephosphorylation rate similar to chemotaxis CheYs [25]–[27].

CheA3 phosphorylates the REC1 domain of CheS3

Since the REC1 domain of CheS3 is not phosphorylated by the tethered HK domain, we questioned whether CheA3 participates in the CheS3 pathway by phosphorylating the REC1 domain of CheS3. We initially performed a phosphotransfer assay using CheA3∼P as the phospho-donor and did not observe CheS3-REC1 phosphorylation in Buffer 9 (Figure S3B) or Buffer 15 (Figure S3C). We reasoned that it may be difficult to observe an in vitro intermolecular transfer of phosphate from CheA3 to CheS3 as the intramolecular transfer from the HK domain of CheA3 to the tethered REC domain of CheA3 may outcompete this reaction. We therefore repeated the assay using the CheA3:D663A mutant as the tethered mutated REC domain would not compete with this intermolecular transfer. As shown in Figure 5E, CheA3:D663A does indeed transfer a phosphate to the CheS3-REC1 domain. This transfer from CheA3 to CheS3-REC1 also demonstrates a level of specificity typically exhibited between cognate HK-RR partners, as phosphate does not flow from CheS3 to CheA3-REC (Figure 5F, Figure S3D).

As shown in Figure 2, a D54A mutation in the CheS3 REC1 domain that would be unable to accept a phosphate in the REC domain exhibits a cyst deficient hypo-cyst phenotype. This is opposite of the hyper-cyst phenotype exhibited by a H453A mutation (Figure 2) that would disrupt CheS3 kinase activity. These opposing phenotypes suggest that phosphorylation of the CheS3 REC1 domain by the HK domain from CheA3 would have an inhibitory effect on autophosphorylation of CheS3 or a stimulating effect on autodephosphorylation of CheS3. This conclusion is also supported by genetic and epistasis studies which indicates that cheS3 null mutants are hyper-cyst and also epistatic to the hypo-cyst phenotype exhibited by cheA3 null mutants (Figure 2).

Discussion

The R. centenum che3 gene cluster encodes a complex chemotaxis system of alternative cellular functions

Chemotaxis and chemotaxis-like signaling pathways represent some of the more complex multicomponent signal transduction systems present in prokaryotes. A recent bioinformatic analysis of 450 non-redundant prokaryotic genomes found that 245 contained at least one chemotaxis-like protein [28]. In these 245 genomes there are a total of 416 chemotaxis-like systems that contain at least an MCP, CheA, and CheW homologs, which together are considered a minimum chemotaxis core [28]. Together, Che-like signal transduction cascades are known to control three classes of function: flagellar motility, type IV pili-based motility (TFP), and alternative cellular functions (ACF) [28]. The ACF class comprises approximately 6% of all the identified chemotaxis systems, regulating cellular processes such as cell development [29], [30], biofilm formation [31], exopolysaccharide production [32], cell-cell interactions [33], [34], and flagellum biosynthesis [35]. In fact, most identifiable Che-like signal transduction cascades are yet to be genetically disrupted so the function of many of these pathways remains to be elucidated.

Chemotaxis systems either exhibit typical chemotaxis architecture as found in E. coli, or have evolved to include additional auxiliary proteins and/or multi-domain hybrid components. Only a few of the more complex Che-like systems containing auxiliary proteins have been biochemically and genetically assayed for the flow of phosphate among protein components. Consequently, it remains unclear whether the CheA-CheY paradigm from E. coli will hold true for the many other, and often more complex, Che-like cascades from other species. Clearly the results of this study indicate that the Che3 cascade from R. centenum differs from this paradigm in that CheA3 functions to regulate the CheS3-CheY3 TCS. In some respects this is similar to the Che3 cascade from M. xanthus where a CheA homolog controls developmental program by acting as a phosphatase to the DNA binding RR CrdA [7].

HHKs with appended REC domains are often present in organisms that adopt complex life styles such as M. xanthus [36]–[39] and R. centenum [29], [40], allowing for added layers of regulation within signaling systems. In some cases, intramolecular phosphoryl transfer occurs within HHKs. For example, RodK from M. xanthus has three REC domains that are all essential for fruiting body formation but the HK domain selectively transfers a phosphate to its third REC domain [36]. In E. coli, the HK and REC domains of RcsC are involved in a HK→REC→Hpt→REC phosphorelay, which regulates capsular synthesis and swarming [41]. In other cases, the receiver domain can either prevent the HK from autophosphorylating, presumably by an occluding mechanism [42], or enhance gene expression by interacting with the cognate response regulator of the HHK [43].

Cysts are a dormant, non-growing state needed for survival in poor growth conditions, so the decision to form or impede this developmental pathway must involve multiple inputs and checkpoints. In the R. centenum Che3 cascade, there are three receivers that are capable of accepting a phosphate from two HHKs (CheB3 is not discussed here since CheB homologs are typically involved in MCP modification and not downstream signaling). CheA3 and CheS3 are HHKs containing respective C-terminal and N-terminal REC domains whereas CheY3 is a stand-alone receiver without an identifiable output domain. The presence of three REC domains and two HK domains encoded in this gene cluster potentially makes the Che3 signaling cascade quite complex with the possibility of multiple inputs and check points, which are presumably necessary to control the decision to induce cyst formation.

Phosphorylation levels of CheA3 and CheS3 are modulated by their receiver domains, which have direct impact on the timing of cyst formation

We showed that CheA3∼P is acid - and base-labile, indicating that an intramolecular phosphoryl transfer occurs between the tethered HK and REC domains. This transfer is inhibited when D663 is substituted with an Ala, giving rise to a His-phosphorylated CheA3:D663A∼P that is stable at high pH. The phosphate on CheA3:D663A is much more stable than observed with wild type CheA3, indicating that the tethered REC domain likely functions as a phosphate sink, attenuating phosphorylation of its own HK domain. Fused REC domains serving as phosphate sinks are not unprecedented. CheAY2, a CheA-CheY hybrid in Helicobacter pylori has also been shown to use its REC domain as a phosphate sink by rapidly dephosphorylating the linked kinase domain [27].

Unlike CheA3, the REC1 domain of CheS3 appears to serve a different function. CheS3∼P is acid-labile and base-resistant and also does not phosphorylate its receiver truncation (CheS3-REC1) in vitro. This indicates that the CheS3 HK domain does not phosphorylate its own REC1 domain. While it is unclear whether the CheS3 REC1 domain directly interacts with the HK domain, it is evident that the REC1 domain greatly affects the phosphorylation state of H453. This is evidenced by the half-life of CheS3:D54A∼P that is prolonged by many hours relative to wild type CheS3∼P (Table 1). Furthermore, the CheS3:D54A mutant has an opposing in vivo phenotype from a CheS3:H453A mutant thereby indicating that the CheS3 REC1 domain has regulatory control over phosphorylation of the CheS3 HK domain. Based on these results, we propose that D54 stimulates autodephosphorylation of the C-terminal HK domain by a mechanism other than transferring and accepting phosphates from the CheS3 HK domain. Although we do not yet have molecular details on how Asp-phosphorylated CheS3 inhibits the HK domain of CheS3, genetic and biochemical results clearly suggest that CheA3 promotes cyst formation by phosphorylating the REC1 domain in CheS3. It is likely that Asp-phosphorylated REC1 domain causes a conformational adoption that either inhibits CheS3 autophosphorylation or accelerates autodephosphorylation of the tethered HK domain.

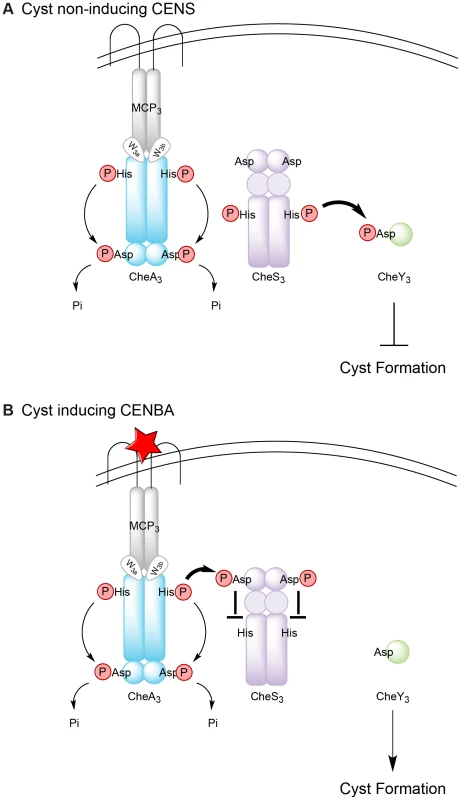

The present Che3 pathway model involves communication between CheA3 and CheS3

The results of this study allow us to establish a working model for the Che3 signal transduction cascade in R. centenum (Figure 6). Under cyst non-inducing conditions, CheA3 has low basal level of kinase activity that directs intramolecular phosphate flow in the direction of His→Asp→Pi. The REC1 domain of CheS3 remains unphosphorylated so the HK domain of CheS3 operates at a high level of activity that effectively transfers phosphoryl groups to CheY3. CheY3∼P subsequently activates downstream components that repress cyst formation (Figure 6A). Upon starvation or desiccation (cyst inducing conditions), a signal is sensed by MCP3, which fully activates the kinase activity of CheA3 (Figure 6B). Activated CheA3 is now able to phosphorylate the REC1 domain of CheS3 thereby turning off the HK domain of CheS3 leading to unphosphorylated CheY3 that induces cyst formation (Figure 6B).

Fig. 6. Model for regulation of Che3 signal transduction pathway.

(A) In the absence of unknown signals, CheA3 is deactivated; CheS3 autophosphorylates and transfers phosphates to its cognate response regulator CheY3; activated CheY3 then interacts with downstream components to repress cyst formation. (B) In the presence of an unknown signal (denoted by a red star), CheA3 autophosphorylation is activated; His-phosphorylated CheA3 constantly transfers the phosphates to its C-terminal REC domain, which serves as a phosphate sink. CheA3∼P also phosphorylates the REC1 domain of CheS3, inhibiting CheS3 kinase activity and CheY3 remains unphosphorylated. Cyst formation is therefore derepressed without activated CheY3. The thickness of the arrows represents the level of phosphate flow. This model also readily explains the opposing phenotypes of the cheA3:D663A and cheS3:D54A REC mutant strains (Figure S7). In the cheA3:D663A REC mutant, intramolecular phosphoryl transfer, which acts as a CheA3 phosphate sink, would be blocked. The resulting elevated phosphate concentration at the CheA3 HK domain would subsequently lead to elevated phosphoryl transfer from CheA3 to the REC1 domain of CheS3 under both vegetative and cyst inducing growth conditions. Constitutive phosphorylation of the REC1 domain of CheS3 by CheA3:D663A would lead to a reduction in the HK activity of CheS3 and subsequent reduction in phosphorylation of CheY3. Thus, the cheA3:D663A strain should have a cyst defective phenotype under all growth conditions, which is what is observed (Figure S7A and B).

For the cheS3 REC1 mutant, CheA3 is no longer capable of phosphorylating the CheS3 REC1 domain due to the D54A substitution (Figure S7C). Therefore the CheS3 HK domain is able to autophosphorylate and phosphorylate CheY3 under all growth conditions. This would result in constitutive repression of cyst formation, which is also observed (Figure S7C and D).

Multiple cyst developmental signal transduction circuits require integration

Even though details of the Che3 phosphorylation cascade have been revealed, several features of this pathway still require clarification. First, based on the E. coli chemotaxis model, CheA3 should be activated by an extracellular signal received by MCP3, the nature of which is currently unknown. Second, it is unclear whether CheS3 is regulated only from phosphorylation by CheA3 or if it also directly senses changes in metabolism during encystment via a PAS domain. Third, the outputs and the downstream components of the Che3 signal transduction cascade remain elusive. One possibility is that CheY3 passes its phosphate onto unidentified downstream components.

Also not yet reconciled is how the Che3 pathway is integrated with the cGMP signaling in R. centenum. This signaling nucleotide is synthesized as cells transition from vegetative growth into the cyst developmental phase [44]. While this is a newly identified signaling pathway, a cGMP responsive CRP-like transcription factor has been identified and is required to induce cyst development [44]. How these two seemingly independent pathways together control the induction and timing of cyst formation constitutes a significant challenge in our understanding of this Gram-negative developmental pathway.

Materials and Methods

Construction of cheS3 and cheA3 point mutation suicide vectors

cheS3 was PCR amplified with 500 bp of flanking DNA as two fragments using wild type cells as template for colony PCR with primer pairs listed in Table S2. PCR amplified fragments were separately cloned and sequenced in pTOPO. Using a Quikchange (Stratagene) point mutagenesis kit, the D54A mutation was made within the 5′ cheS3 fragment harboring plasmid, whereas a H453A mutation was made in the plasmid harboring the 3′ cheS3 fragment using primers described in Table S2. Suicide vector constructs for cheS3 containing D54A or H453A mutations were then constructed by ligating the appropriate 5′ and 3′ cheS3 fragments directly into pZJD29a using external BamHI and XbaI sites and were internally joined by a BbsI site common to both fragments. After sequence confirmation, plasmids were mated from E. coli S17-1 (λpir) into an R. centenum ΔcheS3 strain [8]. Initial recombinants were selected for on CENSGm and second recombinants with chromosomal cheS3 point mutants were identified by phenotypic (GmS/SucR) and colony PCR analyses. Suicide vector constructs for cheA3:H49A, cheA3:D663A, and cheY3:D64A were similarly constructed using point mutagenesis primers detailed in Table S2, with cheA3 internally ligated using a ClaI site and cheY3 cloned as one fragment. See Table S3 for a complete list of R. centenum strains used in this study.

Characterization of cellular morphology and % cyst formation by flow cytometry

Two types of media were used to assay for encystment: CENS was used for vegetative growth [45], and CENBA for inducing cyst formation [46]. Encystment uninduced cells were prepared by overnight growth in CENS at 37°C. Encystment induced cells were prepared by washing overnight CENS cultures twice in CENBA, subculturing 1∶40 into CENBA and then incubating at 37°C for 3 days.

For microscopic observations, phase-contrast microscopy was performed on a Nikon E800 light microscope equipped with a 100× Plan Apo oil objective. For flow cytometry, CENS and CENBA cultures were diluted in 40 mM phosphate buffer and sonicated briefly (∼1 sec) at lower power to disaggregate cyst cells. All samples were stained in 2 µM Syto-9 (Life Technologies/Molecular Probes, Grand Island, NY) for 1.5 hours. Syto-9 is a permeant DNA stain that was shown microscopically to penetrate both vegetative and cyst cells similarly (data not shown). Initially fluorescent calibration beads of 880 nanometers and 10 microns were used to set the limits for background. After staining, cells were diluted ∼1∶10–1∶20 in 40 mM phosphate buffer just prior to running to achieve ∼1000 events per second on a Becton Dickenson FACS Calibur flow cytometer running CellQuest Pro data collection software using an argon laser (488 nm). 100,000 events were collected per sample with two biological replicates analyzed for each bacterial strain grown in each media. Forward and side scatter (SSC vs FSC) were plotted in logarithmic scales. Hypo-cyst ΔcheA3 and hyper-cyst ΔcheS3 strains were used to determine the appropriate gating to use for vegetative cells versus cyst cells. FlowJo version 10 (Tree Star, Inc.) was used to analyze the data and plot the data for publication. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Protein overexpression and purification

Coding regions of CheS3, CheA3, CheY3, and the receiver domains of CheA3 and CheS3 (CheA3-REC and CheS3-REC1) were PCR amplified from R. centenum genomic DNA with primers listed in Table S1. Gel-purified PCR products were cloned into pBluescript SK+ or pGEM-T, sequenced, then subcloned into the NdeI and XhoI sites in vector pET28a. pET28a plasmids for overexpression of CheS3 and CheA3 point mutants were generated using the appropriate pZJD29a vector as template for PCR using primers detailed in Table S1. All pET28a constructs were transformed into E. coli BL21 Rosetta 2 (DE3) cells (Novagen). See Table S3 for a complete list of E. coli strains used in this study. For overexpression, overnight cultures of E. coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) cells were subcultured 1∶100 into 1 L LB medium and shaken at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.5. Protein overexpression was induced at an isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside concentration of 0.4 mM and cultures were incubated overnight at 16°C with gentle agitation. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and stored at −80°C until further use. For purification of all proteins, cell pellets were resuspended and lysed by ultrasonication in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole and 10% glycerol). Purification was performed on 1 mL HisTrap HP (GE Healthcare) columns using an FPLC system. His-tagged proteins were eluted in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffers with a gradient of 25–500 mM imidazole. Fractions containing purified proteins were dialyzed into a storage buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl in 30% glycerol) and stored at −20°C until further use.

Autophosphorylation, phosphotransfer and stability assays

Twenty-one Tris buffers containing common mono - and divalent metal ions were used in this study for HHK phosphorylation and phosphotransfer assays (see the full list of buffer compositions in Table S1). All kinase reactions and phospho-transfers were performed in 0.2 mM final ATP concentration except for the half-life determination experiments. All reactions were stopped by addition of 6× SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer. All phospho-proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and gels were examined by autoradiography on a Typhoon 9100 scanner (GE Healthcare) located in the Indiana University Physical Biochemistry Instrumentation Facility.

In the metal ion dependency assays (shown in Figure 3B and Figure S3), isolated kinases were diluted in the indicated buffers to 2–5 µM. Kinase reactions were initiated by adding 1/20 volume of ATP/[γ-33P] ATP mix in 25 mM Tris pH 7.5 and allowed to proceed for 30 min at room temperature. For phosphoryl transfer to CheY3 shown in Figure S3, 1/10 volume of 65 mM CheY3 was also added to each reaction mixture at the end of 30 min autophosphorylation for another 30 min incubation at room temperature.

In assays assessing intermolecular phosphoryl transfer shown in Figure 4C, Figure 5, and Figure 6, ATP mixes and protein dilutions were made in same buffer as indicated in the text. 2–5 µM kinases were first phosphorylated in 0.2 mM ATP for 30 min followed by addition of 1/10 volume of 65 µM CheY3 or receiver domain truncations (CheS3-REC1 or CheA3-REC). The time of receiver addition was set to time 0. Phosphoryl transfer was then assessed at various time intervals.

To determine the half-lives of phosphorylated kinases, 2–5 µM CheA3 and CheA3:D663A were pre-autophosphorylated in the presence of 10 µM ATP mix in Buffer 9 for 50 min before passing through Bio-Rad Micro Spin 6 chromatography columns to remove excess ATP. Dephosphorylation was monitored at room temperature by removing 10 µL of the filtrates at various time intervals. Phosphorylation of the kinases was quantified using ImageJ software by integrating the grayscale density of the radioactive bands. % Kinase phosphorylation was plotted over 300 min and data points were fitted to one phase exponential decay using Prism. Half-lives of CheS3 and CheS3:D54A were measured with the same protocol with the exception that Buffer 5 was used in place of Buffer 9.

Acid-base stability assays

The phosphorylation state of all CheS3 and CheA3 variants was determined by assaying phosphoprotein stability under acidic or basic conditions using a non-filter based assay [47]. Kinases were allowed to autophosphorylate at room temperature for 30 min, after which phosphoproteins were denatured by adding 0.1 volume of 20% SDS. Aliquots were withdrawn and mixed with equal volumes of 0.1 or 1.0 M Tris pH 7.5, HCl or NaOH and incubated for 30 min at 37°C before being neutralized with 1.0 M Tris-HCl pH 7.5. Samples were then mixed with 6× loading dye and resolved by SDS-PAGE and assayed for phosphorylation by autoradiography. Phosphorylation of the kinases was quantified using ImageJ software by integrating the grayscale density of the radioactive bands.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. SteenhoudtO, VanderleydenJ (2000) Azospirillum, a free-living nitrogen-fixing bacterium closely associated with grasses: genetic, biochemical and ecological aspects. Fems Microbiol Rev 24 : 487–506.

2. DoddIC, Ruiz-LozanoJM (2012) Microbial enhancement of crop resource use efficiency. Curr Opin Biotechnol 23 : 236–242 doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2011.09.005

3. OkonY, ItzigsohnR (1995) The development of Azospirillum as a commercial inoculant for improving crop yields. Biotechnol Adv 13 : 415–424 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0734-9750(95)02004-M

4. SadasivanL, NeyraCA (1985) Flocculation in Azospirillum brasilense and Azospirillum lipoferum: exopolysaccharides and cyst formation. J Bacteriol 163 : 716–723.

5. BerlemanJE, BauerCE (2004) Characterization of cyst cell formation in the purple photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum centenum. Microbiology (Reading, Engl) 150 : 383–390.

6. StadtwalddemchickR, StadtwalddemchickR, TurnerFR, TurnerFR, GestH, et al. (1990) Physiological properties of the thermotolerant photosynthetic bacterium, Rhodospirillum centenum. Fems Microbiol Lett 67 : 139–143.

7. WillettJW, KirbyJR (2011) CrdS and CrdA comprise a two-component system that is cooperatively regulated by the Che3 chemosensory system in Myxococcus xanthus. MBio 2: e00110–11–e00110–11 doi:10.1128/mBio.00110-11

8. BerlemanJE, BauerCE (2005) Involvement of a Che-like signal transduction cascade in regulating cyst cell development in Rhodospirillum centenum. Molecular Microbiology 56 : 1457–1466 doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04646.x

9. RagatzL, JiangZY, JiangZY, BauerCE, BauerCE, et al. (1995) Macroscopic phototactic behavior of the purple photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum centenum. Arch Microbiol 163 : 1–6.

10. BerlemanJE, BauerCE (2004) Characterization of cyst cell formation in the purple photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum centenum. Microbiology (Reading, Engl) 150 : 383–390.

11. FavingerJ, StadtwaldR, GestH (1989) Rhodospirillum centenum, sp. nov., a thermotolerant cyst-forming anoxygenic photosynthetic bacterium. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 55 : 291–296.

12. DuttaR, InouyeM (1996) Reverse phosphotransfer from OmpR to EnvZ in a kinase−/phosphatase+ mutant of EnvZ (EnvZ.N347D), a bifunctional signal transducer of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 271 : 1424–1429 Available: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=8576133&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks.

13. GeorgellisD, KwonO, De WulfP, LinE (1998) Signal decay through a reverse phosphorelay in the arc two-component signal transduction system. J Biol Chem 273 : 32864–32869 Available: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=9830034&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks.

14. HessJF, OosawaK, KaplanN, SimonMI (1988) Phosphorylation of three proteins in the signaling pathway of bacterial chemotaxis. Cell 53 : 79–87.

15. LukatGS, StockAM, StockJB (1990) Divalent metal ion binding to the CheY protein and its significance to phosphotransfer in bacterial chemotaxis. Biochemistry-Us 29 : 5436–5442 Available: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=2201404&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks.

16. WuichetK, CantwellBJ, ZhulinIB (2010) Evolution and phyletic distribution of two-component signal transduction systems. Curr Opin Microbiol 13 : 219–225 Available: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=20133179&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks.

17. CapraEJ, PerchukBS, AshenbergO, SeidCA, SnowHR, et al. (2012) Spatial tethering of kinases to their substrates relaxes evolutionary constraints on specificity. Molecular Microbiology 86 : 1393–1403 doi:10.1111/mmi.12064

18. TownsendGE, RaghavanV, ZwirI, GroismanEA (2013) Intramolecular arrangement of sensor and regulator overcomes relaxed specificity in hybrid two-component systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: E161–E169 doi:10.1073/pnas.1212102110

19. Wegener-FeldbrüggeS, Søgaard-AndersenL (2009) The atypical hybrid histidine protein kinase RodK in Myxococcus xanthus: spatial proximity supersedes kinetic preference in phosphotransfer reactions. J Bacteriol 191 : 1765–1776 Available: http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/191/6/1765.

20. FujitakiJM, SmithRA (1984) Techniques in the detection and characterization of phosphoramidate-containing proteins. Meth Enzymol 107 : 23–36 Available: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=6438441&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks.

21. KoshlandDE (1952) Effect of Catalysts on the Hydrolysis of Acetyl Phosphate. Nucleophilic Displacement Mechanisms in Enzymatic Reactions 74 : 2286–2292 Available: http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja01129a035.

22. FeherVA, ZapfJW, HochJA, DahlquistFW, WhiteleyJM, et al. (1995) 1H, 15N, and 13C backbone chemical shift assignments, secondary structure, and magnesium-binding characteristics of the Bacillus subtilis response regulator, Spo0F, determined by heteronuclear high-resolution NMR. Protein Sci 4 : 1801–1814 doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040915

23. GuilletV (2002) Crystallographic and Biochemical Studies of DivK Reveal Novel Features of an Essential Response Regulator in Caulobacter crescentus. J Biol Chem 277 : 42003–42010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204789200

24. NeedhamJV, ChenTY, FalkeJJ (1993) Novel ion specificity of a carboxylate cluster Mg(II) binding site: strong charge selectivity and weak size selectivity. Biochemistry-Us 32 : 3363–3367 Available: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=8461299&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks.

25. SourjikV, SchmittR (1998) Phosphotransfer between CheA, CheY1, and CheY2 in the chemotaxis signal transduction chain of Rhizobium meliloti. Biochemistry-Us 37 : 2327–2335 Available: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=9485379&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks.

26. LukatGS, LEEBH, MOTTONENJM, StockAM, StockJB (1991) Roles of the Highly Conserved Aspartate and Lysine Residues in the Response. Regulator of Bacterial Chemotaxis 266 : 8348–8354 Available: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=1902474&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks.

27. Jiménez-PearsonM-A, DelanyI, ScarlatoV, BeierD (2005) Phosphate flow in the chemotactic response system of Helicobacter pylori. Microbiology (Reading, Engl) 151 : 3299–3311 doi:10.1099/mic.0.28217-0

28. WuichetK, ZhulinIB (2010) Origins and diversification of a complex signal transduction system in prokaryotes. Sci Signal 3: ra50 doi:10.1126/scisignal.2000724

29. BerlemanJE, BauerCE (2005) Involvement of a Che-like signal transduction cascade in regulating cyst cell development in Rhodospirillum centenum. Molecular Microbiology 56 : 1457–1466 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04646.x

30. KirbyJR, ZusmanDR (2003) Chemosensory regulation of developmental gene expression in Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100 : 2008–2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0330944100

31. HickmanJW, TifreaDF, HarwoodCS (2005) A chemosensory system that regulates biofilm formation through modulation of cyclic diguanylate levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102 : 14422–14427 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507170102

32. BlackWP, SchubotFD, LiZ, YangZ (2010) Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation among Dif chemosensory proteins essential for exopolysaccharide regulation in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol 192 : 4267–4274 doi: 10.1128/JB.00403-10

33. BibleAN, StephensBB, OrtegaDR, XieZ, AlexandreG (2008) Function of a chemotaxis-like signal transduction pathway in modulating motility, cell clumping, and cell length in the alphaproteobacterium Azospirillum brasilense. J Bacteriol 190 : 6365–6375 doi:10.1128/JB.00734-08

34. BibleA, RussellMH, AlexandreG (2012) The Azospirillum brasilense Che1 chemotaxis pathway controls swimming velocity, which affects transient cell-to-cell clumping. J Bacteriol 194 : 3343–3355 doi:10.1128/JB.00310-12

35. BerlemanJE, BauerCE (2005) A che-like signal transduction cascade involved in controlling flagella biosynthesis in Rhodospirillum centenum. Molecular Microbiology 55 : 1390–1402 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04489.x

36. RasmussenAA, Wegener-FeldbrüggeS, PorterSL, ArmitageJP, Søgaard-AndersenL (2006) Four signalling domains in the hybrid histidine protein kinase RodK of Myxococcus xanthus are required for activity. Molecular Microbiology 60 : 525–534 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05118.x

37. RasmussenAA, PorterSL, ArmitageJP, Søgaard-AndersenL (2005) Coupling of multicellular morphogenesis and cellular differentiation by an unusual hybrid histidine protein kinase in Myxococcus xanthus. Molecular Microbiology 56 : 1358–1372 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04629.x

38. HiggsPI, JagadeesanS, MannP, ZusmanDR (2008) EspA, an Orphan Hybrid Histidine Protein Kinase, Regulates the Timing of Expression of Key Developmental Proteins of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol 190 : 4416–4426 doi: 10.1128/JB.00265-08

39. KimuraY, NakanoH, TerasakaH, TakegawaK (2001) Myxococcus xanthus mokA encodes a histidine kinase-response regulator hybrid sensor required for development and osmotic tolerance. J Bacteriol 183 : 1140–1146 doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1140-1146.2001

40. DinN, ShoemakerCJ, AkinKL, FrederickC, BirdTH (2011) Two putative histidine kinases are required for cyst formation in Rhodospirillum centenum. Arch Microbiol 193 : 209–222 doi:10.1007/s00203-010-0664-7

41. TakedaS, FujisawaY, MatsubaraM, AibaH, MizunoT (2001) A novel feature of the multistep phosphorelay in Escherichia coli: a revised model of the RcsC→YojN→RcsB signalling pathway implicated in capsular synthesis and swarming behaviour. Molecular Microbiology 40 : 440–450 Available: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=11309126&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks.

42. InclánYF, LaurentS, ZusmanDR (2008) The receiver domain of FrzE, a CheA-CheY fusion protein, regulates the CheA histidine kinase activity and downstream signalling to the A - and S-motility systems of Myxococcus xanthus. Molecular Microbiology 68 : 1328–1339 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06238.x

43. WiseAA, FangF, LinY-H, HeF, LynnDG, et al. (2010) The receiver domain of hybrid histidine kinase VirA: an enhancing factor for vir gene expression in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol 192 : 1534–1542 Available: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=20081031&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks.

44. MardenJN, DongQ, RoychowdhuryS, BerlemanJE, BauerCE (2011) Cyclic GMP controls Rhodospirillum centenum cyst development. Molecular Microbiology 79 : 600–615 doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07513.x

45. JiangZY, RushingBG, BaiY, GestH, BauerCE (1998) Isolation of Rhodospirillum centenum mutants defective in phototactic colony motility by transposon mutagenesis. J Bacteriol 180 : 1248–1255.

46. BerlemanJE, BauerCE (2004) Characterization of cyst cell formation in the purple photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum centenum. Microbiology (Reading, Engl) 150 : 383–390.

47. SainiDK (2004) DevR-DevS is a bona fide two-component system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis that is hypoxia-responsive in the absence of the DNA-binding domain of DevR. Microbiology (Reading, Engl) 150 : 865–875 Available: http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&id=15073296&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks.

48. SchultzJ, MilpetzF, BorkP, PontingCP (1998) Colloquium Paper: SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: Identification of signaling domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95 : 5857–5864 doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5857

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Interaction between and during Mammalian Jaw Patterning and in the Pathogenesis of SyngnathiaČlánek Clustering of Tissue-Specific Sub-TADs Accompanies the Regulation of Genes in Developing LimbsČlánek Transcription Factor Occupancy Can Mediate Active Turnover of DNA Methylation at Regulatory RegionsČlánek Tay Bridge Is a Negative Regulator of EGFR Signalling and Interacts with Erk and Mkp3 in the Wing

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2013 Číslo 12- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Stressing the Importance of CHOP in Liver Cancer

- The AmAZI1ng Roles of Centriolar Satellites during Development

- Flies Get a Head Start on Meiosis

- Recommendations from Jane Gitschier's Bookshelf

- And Baby Makes Three: Genomic Imprinting in Plant Embryos

- Bugs in Transition: The Dynamic World of in Insects

- Defining the Role of ATP Hydrolysis in Mitotic Segregation of Bacterial Plasmids

- Synaptonemal Complex Components Promote Centromere Pairing in Pre-meiotic Germ Cells

- Cohesinopathies of a Feather Flock Together

- Genetic Recombination Is Targeted towards Gene Promoter Regions in Dogs

- Parathyroid-Specific Deletion of Unravels a Novel Calcineurin-Dependent FGF23 Signaling Pathway That Regulates PTH Secretion

- MAN1B1 Deficiency: An Unexpected CDG-II

- Phosphate Flow between Hybrid Histidine Kinases CheA and CheS Controls Cyst Formation

- Basolateral Mg Extrusion via CNNM4 Mediates Transcellular Mg Transport across Epithelia: A Mouse Model

- Truncation of Unsilences Paternal and Ameliorates Behavioral Defects in the Angelman Syndrome Mouse Model

- Autozygome Sequencing Expands the Horizon of Human Knockout Research and Provides Novel Insights into Human Phenotypic Variation

- Huntington's Disease Induced Cardiac Amyloidosis Is Reversed by Modulating Protein Folding and Oxidative Stress Pathways in the Heart

- Low Frequency Variants, Collapsed Based on Biological Knowledge, Uncover Complexity of Population Stratification in 1000 Genomes Project Data

- Targeted Ablation of and in Retinal Progenitor Cells Mimics Leber Congenital Amaurosis

- Genomic Imprinting in the Embryo Is Partly Regulated by PRC2

- Binary Cell Fate Decisions and Fate Transformation in the Larval Eye

- The Stress-Regulated Transcription Factor CHOP Promotes Hepatic Inflammatory Gene Expression, Fibrosis, and Oncogenesis

- A Global RNAi Screen Identifies a Key Role of Ceramide Phosphoethanolamine for Glial Ensheathment of Axons

- Functional Analysis of the Interdependence between DNA Uptake Sequence and Its Cognate ComP Receptor during Natural Transformation in Species

- Cross-Modulation of Homeostatic Responses to Temperature, Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide in

- Alcohol-Induced Histone Acetylation Reveals a Gene Network Involved in Alcohol Tolerance

- Molecular Characterization of Host-Specific Biofilm Formation in a Vertebrate Gut Symbiont

- CRIS—A Novel cAMP-Binding Protein Controlling Spermiogenesis and the Development of Flagellar Bending

- Dual Regulation of the Mitotic Exit Network (MEN) by PP2A-Cdc55 Phosphatase

- Expanding the Marine Virosphere Using Metagenomics

- Detection of Slipped-DNAs at the Trinucleotide Repeats of the Myotonic Dystrophy Type I Disease Locus in Patient Tissues

- Interaction between and during Mammalian Jaw Patterning and in the Pathogenesis of Syngnathia

- Mutations in the UQCC1-Interacting Protein, UQCC2, Cause Human Complex III Deficiency Associated with Perturbed Cytochrome Protein Expression

- Reactivation of Chromosomally Integrated Human Herpesvirus-6 by Telomeric Circle Formation

- Anoxia-Reoxygenation Regulates Mitochondrial Dynamics through the Hypoxia Response Pathway, SKN-1/Nrf, and Stomatin-Like Protein STL-1/SLP-2

- The Midline Protein Regulates Axon Guidance by Blocking the Reiteration of Neuroblast Rows within the Drosophila Ventral Nerve Cord

- Tomato Yield Heterosis Is Triggered by a Dosage Sensitivity of the Florigen Pathway That Fine-Tunes Shoot Architecture

- Selection on Plant Male Function Genes Identifies Candidates for Reproductive Isolation of Yellow Monkeyflowers

- Role of Tomato Lipoxygenase D in Wound-Induced Jasmonate Biosynthesis and Plant Immunity to Insect Herbivores

- Meiotic Cohesin SMC1β Provides Prophase I Centromeric Cohesion and Is Required for Multiple Synapsis-Associated Functions

- Identification of Sphingolipid Metabolites That Induce Obesity via Misregulation of Appetite, Caloric Intake and Fat Storage in

- Genome-Wide Screen Reveals Replication Pathway for Quasi-Palindrome Fragility Dependent on Homologous Recombination

- Histone Methylation Restrains the Expression of Subtype-Specific Genes during Terminal Neuronal Differentiation in

- A Novel Intergenic ETnII-β Insertion Mutation Causes Multiple Malformations in Mice

- The NuRD Chromatin-Remodeling Enzyme CHD4 Promotes Embryonic Vascular Integrity by Transcriptionally Regulating Extracellular Matrix Proteolysis

- A Domesticated Transposase Interacts with Heterochromatin and Catalyzes Reproducible DNA Elimination in

- Acute Versus Chronic Loss of Mammalian Results in Distinct Ciliary Phenotypes

- MBD3 Localizes at Promoters, Gene Bodies and Enhancers of Active Genes

- Positive and Negative Regulation of Gli Activity by Kif7 in the Zebrafish Embryo

- A Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Mouse Model Supports a Role of ZFYVE26/SPASTIZIN for the Endolysosomal System

- The CCR4-NOT Complex Mediates Deadenylation and Degradation of Stem Cell mRNAs and Promotes Planarian Stem Cell Differentiation

- Reconstructing Native American Migrations from Whole-Genome and Whole-Exome Data

- Contributions of Protein-Coding and Regulatory Change to Adaptive Molecular Evolution in Murid Rodents

- Comprehensive Analysis of Transcriptome Variation Uncovers Known and Novel Driver Events in T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- A -Acting Protein Effect Causes Severe Eye Malformation in the Mouse

- Clustering of Tissue-Specific Sub-TADs Accompanies the Regulation of Genes in Developing Limbs

- Germline Progenitors Escape the Widespread Phenomenon of Homolog Pairing during Development

- Transcription Factor Occupancy Can Mediate Active Turnover of DNA Methylation at Regulatory Regions

- Somatic mtDNA Mutation Spectra in the Aging Human Putamen

- ESCRT-I Mediates FLS2 Endosomal Sorting and Plant Immunity

- Ethylene Promotes Hypocotyl Growth and HY5 Degradation by Enhancing the Movement of COP1 to the Nucleus in the Light

- The PAF Complex and Prf1/Rtf1 Delineate Distinct Cdk9-Dependent Pathways Regulating Transcription Elongation in Fission Yeast

- Dual Regulation of Gene Expression Mediated by Extended MAPK Activation and Salicylic Acid Contributes to Robust Innate Immunity in

- Quantifying Missing Heritability at Known GWAS Loci

- Smc5/6-Mms21 Prevents and Eliminates Inappropriate Recombination Intermediates in Meiosis

- Smc5/6 Coordinates Formation and Resolution of Joint Molecules with Chromosome Morphology to Ensure Meiotic Divisions

- Tay Bridge Is a Negative Regulator of EGFR Signalling and Interacts with Erk and Mkp3 in the Wing

- Meiotic Crossover Control by Concerted Action of Rad51-Dmc1 in Homolog Template Bias and Robust Homeostatic Regulation

- Active Transport and Diffusion Barriers Restrict Joubert Syndrome-Associated ARL13B/ARL-13 to an Inv-like Ciliary Membrane Subdomain

- An Regulatory Circuit Modulates /Wnt Signaling and Determines the Size of the Midbrain Dopaminergic Progenitor Pool

- Variants Induce Differential Protection to Viruses in : A Phenotypic and Phylogenomic Analysis

- Base Pairing Interaction between 5′- and 3′-UTRs Controls mRNA Translation in

- Evidence That Masking of Synapsis Imperfections Counterbalances Quality Control to Promote Efficient Meiosis

- Insulin/IGF-Regulated Size Scaling of Neuroendocrine Cells Expressing the bHLH Transcription Factor in

- Sumoylated NHR-25/NR5A Regulates Cell Fate during Vulval Development

- TATN-1 Mutations Reveal a Novel Role for Tyrosine as a Metabolic Signal That Influences Developmental Decisions and Longevity in

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- The NuRD Chromatin-Remodeling Enzyme CHD4 Promotes Embryonic Vascular Integrity by Transcriptionally Regulating Extracellular Matrix Proteolysis

- Mutations in the UQCC1-Interacting Protein, UQCC2, Cause Human Complex III Deficiency Associated with Perturbed Cytochrome Protein Expression

- The Midline Protein Regulates Axon Guidance by Blocking the Reiteration of Neuroblast Rows within the Drosophila Ventral Nerve Cord

- Tomato Yield Heterosis Is Triggered by a Dosage Sensitivity of the Florigen Pathway That Fine-Tunes Shoot Architecture

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy