-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Histone Deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) Regulates Chromosome Segregation and Kinetochore Function via H4K16 Deacetylation during Oocyte Maturation in Mouse

Changes in histone acetylation occur during oocyte development and maturation, but the role of specific histone deacetylases in these processes is poorly defined. We report here that mice harboring Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− or Hdac2−/− oocytes are infertile or sub-fertile, respectively. Depleting maternal HDAC2 results in hyperacetylation of H4K16 as determined by immunocytochemistry—normal deacetylation of other lysine residues of histone H3 or H4 is observed—and defective chromosome condensation and segregation during oocyte maturation occurs in a sub-population of oocytes. The resulting increased incidence of aneuploidy likely accounts for the observed sub-fertility of mice harboring Hdac2−/− oocytes. The infertility of mice harboring Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/−oocytes is attributed to failure of those few eggs that properly mature to metaphase II to initiate DNA replication following fertilization. The increased amount of acetylated H4K16 likely impairs kinetochore function in oocytes lacking HDAC2 because kinetochores in mutant oocytes are less able to form cold-stable microtubule attachments and less CENP-A is located at the centromere. These results implicate HDAC2 as the major HDAC that regulates global histone acetylation during oocyte development and, furthermore, suggest HDAC2 is largely responsible for the deacetylation of H4K16 during maturation. In addition, the results provide additional support that histone deacetylation that occurs during oocyte maturation is critical for proper chromosome segregation.

Published in the journal: Histone Deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) Regulates Chromosome Segregation and Kinetochore Function via H4K16 Deacetylation during Oocyte Maturation in Mouse. PLoS Genet 9(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003377

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003377Summary

Changes in histone acetylation occur during oocyte development and maturation, but the role of specific histone deacetylases in these processes is poorly defined. We report here that mice harboring Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− or Hdac2−/− oocytes are infertile or sub-fertile, respectively. Depleting maternal HDAC2 results in hyperacetylation of H4K16 as determined by immunocytochemistry—normal deacetylation of other lysine residues of histone H3 or H4 is observed—and defective chromosome condensation and segregation during oocyte maturation occurs in a sub-population of oocytes. The resulting increased incidence of aneuploidy likely accounts for the observed sub-fertility of mice harboring Hdac2−/− oocytes. The infertility of mice harboring Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/−oocytes is attributed to failure of those few eggs that properly mature to metaphase II to initiate DNA replication following fertilization. The increased amount of acetylated H4K16 likely impairs kinetochore function in oocytes lacking HDAC2 because kinetochores in mutant oocytes are less able to form cold-stable microtubule attachments and less CENP-A is located at the centromere. These results implicate HDAC2 as the major HDAC that regulates global histone acetylation during oocyte development and, furthermore, suggest HDAC2 is largely responsible for the deacetylation of H4K16 during maturation. In addition, the results provide additional support that histone deacetylation that occurs during oocyte maturation is critical for proper chromosome segregation.

Introduction

Post-translational modifications of histones, e.g., phosphorylation, methylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation, are critically involved in a number of cellular processes that range from regulating gene expression to repair of DNA damage [1]–[3]. Lysine acetylation of histones is controlled by histone acetyl transferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). In mammals, eighteen HDACs have been identified and grouped into four classes [4]. Class I enzymes HDAC1 and HDAC2 are highly homologous and ubiquitously expressed in different tissues [5]. HDAC1 and HDAC2 lack a DNA binding domain, as do all histone deacetylases, and execute their function by interacting with transcription factors as either homo - or heterodimers, or being part of multi-component repressor complexes [5].

Loss-of-function studies in mice have generated important insights regarding the function of HDAC1 and HDAC2 in regulating cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation. One common theme of several tissue specific HDAC1/2 knockout studies is redundancy and compensation [6]–[9]. Nevertheless, results of other studies support the notion that HDAC1 and HDAC2 have distinct functions in some cells and tissues [10]–[13]. Taken together, these results indicate that the physiological functions of HDAC1 and HDAC2 are complicated and diversified in different tissues or cell types. Recently, we demonstrated compensatory functions of HDAC1 and HDAC2 during mouse oocyte development in which Hdac1 and Hdac2 were specifically deleted in oocytes [14]; deletion of both genes in oocytes results in infertility due to failure of follicle development beyond the secondary follicle stage with ensuing oocyte apoptosis attributed to hyperaceytlation of TRP53.

We also noted in that study that deleting Hdac1−/− in oocytes has no effect on fertility, as also observed for mice harboring Hdac1−/−/Hdac2−/+ oocytes. In contrast, mice in which Hdac2−/− was only deleted in oocytes are sub-fertile despite increased amounts of HDAC1 protein whereas their Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− counterparts are infertile [14]. Taken together, these results suggest a more prominent role for HDAC2 than HDAC1 in oocyte development, whereas HDAC1 plays a more prominent role in preimplantation development [13]. The molecular basis for the sub-fertility of mice harboring Hdac2−/− oocytes or infertility of mice harboring Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/−, however, was not examined.

We report here a characterization of the infertility and sub-fertilty phenotypes observed in mice harboring Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− or Hdac2−/− oocytes, respectively. We find that full-grown or nearly full-grown oocytes can be obtained from mice containing Hdac2−/− or Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes, respectively, albeit highly reduced numbers of Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes are recovered. Oocytes derived from Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice are not capable of supporting development due to defects beyond failure to develop past the secondary follicle stage that include abnormal spindle assembly or inability to initiate DNA replication following maturation and insemination. Similar to double mutant Hdac1 : 2−/− oocytes, Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes obtained from secondary follicles display reduced levels of transcription and decreased amounts of histone H3K4me1-3. A subset of Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and Hdac2−/− oocytes not only fails to undergo the maturation-associated deacetylation of histone H4K16 but also fails to segregate chromosomes correctly. This failure is likely a consequence of compromised kinetochore function in mutant oocytes manifested by a decreased ability to form cold-stable microtubule-kinetochore interactions and a reduced amount of CENP-A localized to centromeres. Last, although zygotes derived from Hdac2−/− eggs replicate their DNA, zygotes derived from Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− eggs do not.

Results

Oocyte Development Is Not as Severely Compromised in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− Mice as Compared to Hdac1 : 2−/− Mice

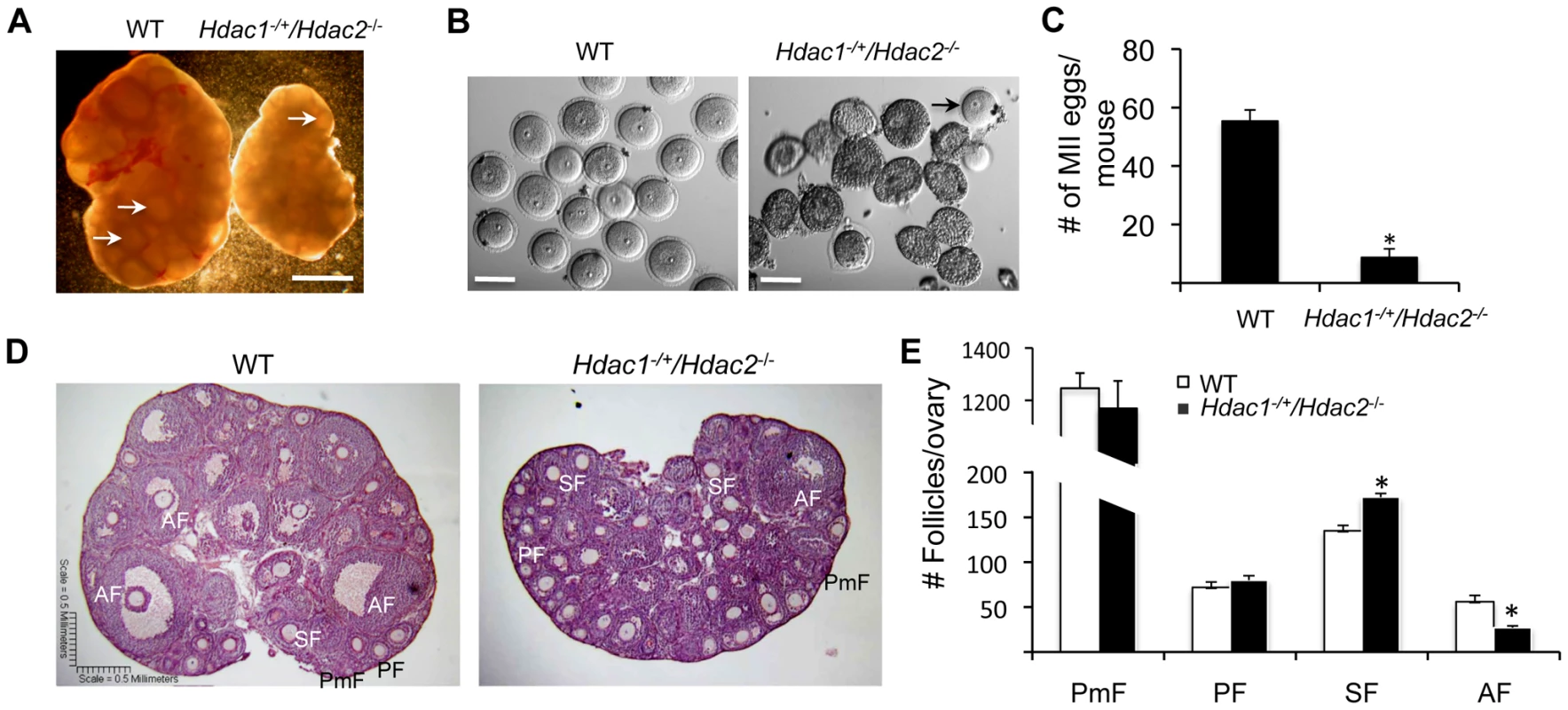

We previously found that ovarian weight in 6-week-old-mice was reduced by ∼60% in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice and by ∼70% in Hdac1 : 2−/− mice compared to wild-type (WT) mice [14]. The size of ovaries obtained from 6-week old Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice was intermediate of WT and double mutant mice (Figure 1A and Fig. 2 in [14]). In addition, although antral follicles were found in ovaries from Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice, their number appeared decreased when compared to WT ovaries (Figure 1A); no antral follicles were found in ovaries from Hdac1 : 2−/− mice [14]. Consistent with fewer antral follicles in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice significantly fewer oocytes were obtained (Figure 1B) and fewer MII eggs were recovered following ovulation (Figure 1C). The diameter of the Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes was about 90% that of full-grown wild-type oocytes (77.4±0.8 µm, wild-type; 69.9±1.1 µm mutant, mean ± SEM, p<0.0001).

Fig. 1. Decreased ovary size and defective oogenesis following specific targeting of Hdac2 and reduction of Hdac1 in oocytes.

(A) Ovary morphology from WT and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice 6 weeks-of-age. WT ovary shows presence of mature follicles (arrows), whereas fewer of such follicles are present in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice. The bar corresponds to 1 mm. (B) Full-grown oocytes are recovered from WT mice, whereas increased number of immature follicles and only a few oocytes are recovered from Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice. The bar corresponds to 100 µm. The arrow points to an oocyte that is nearly full-grown. (C) Fewer eggs are ovulated from Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice after hormonal stimulation. WT and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− 6-week-old females were superovulated with an intraperitoneal injection of 5 I.U eCG followed by administration of 5 I.U. hCG 48 h later. At least 10 mice from each genotype were used, and the average number of ovulated oocytes per female is indicated. * P<0.05. (D) Histological analysis of ovaries obtained from WT and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice18 days-of-age. Primordial (PmF), primary (PF), secondary (SF), and antral follicles (AF) are indicated. The bar corresponds to 0.5 mm. (E) Follicle counts from ovaries obtained from WT and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice 18 days-of-age. Data are from 3 different ovaries and are presented as mean ± SEM. * P<0.05. Fig. 2. Increased histone acetylation, and decreased global transcription and histone H3K4 methylation in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− growing oocytes.

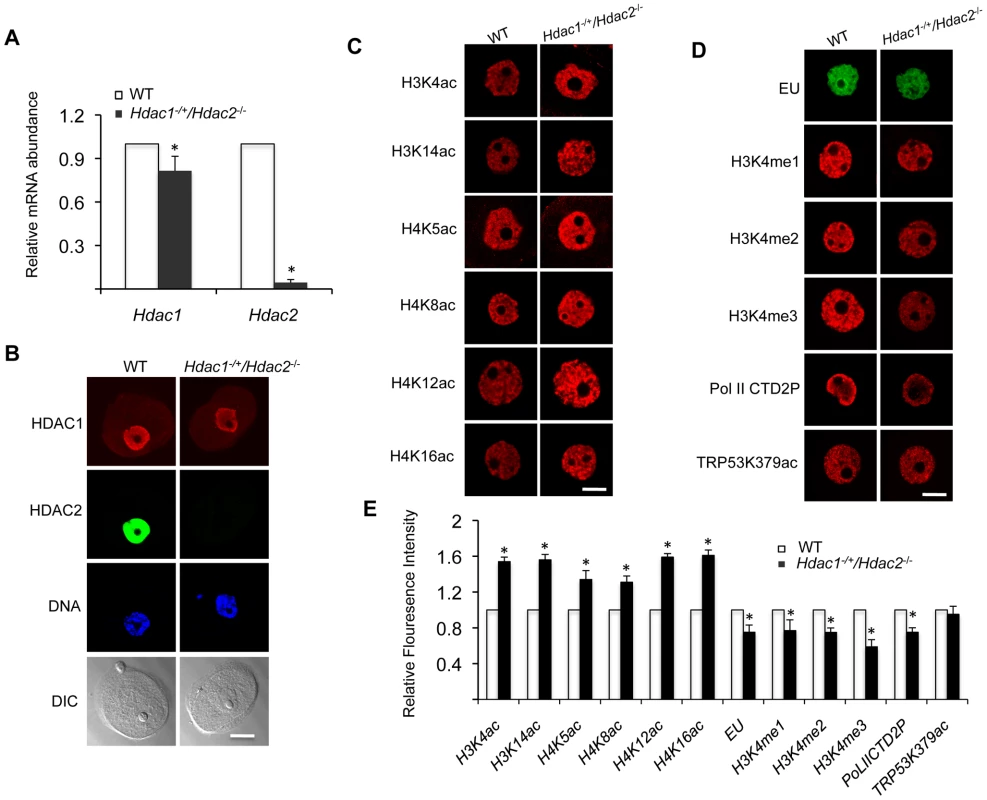

(A) Relative abundance of Hdac1 and Hdac2 transcripts in oocytes obtained from WT and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice 12 days-of-age. Data are expressed relative to that in WT oocytes. The experiment was performed four times and the data expressed as mean ± SEM. *, P<0.05. (B) Immunocytochemical detection of HDAC1 and HDAC2 in WT and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes obtained from mice 12-days-of-age. Oocytes were stained with an anti-HDAC1 antibody (Red), anti-HDAC2 antibody (Green) and DAPI (to detect DNA, Blue). Transmitted light micrographs are also shown (DIC). The bar corresponds to 20 µm. (C) Different acetylated histones were analyzed by immunocytochemistry using oocytes obtained from WT and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice 12 days-of-age. For each histone variant, at least 20 oocytes for each genotype were analyzed, and the experiment was conducted 3 times. Shown are representative images and only the nucleus is shown. The bar corresponds to 10 µm. (D) Immunocytochemical detection of H3K4 methylation, PolII-CTD-2P, EU and TRP53K379 acethylation in WT and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes obtained from mice 12-days-of-age. Shown are representative images and only the nucleus is shown. The bar corresponds to 10 µm. (E) Quantification of the data shown in panel D. Nuclear staining intensity of different proteins in WT oocytes was set to 1 and the data are expressed as mean ± SEM. At least 20 oocytes for each genotype and for each detected protein were analyzed; the experiment was conducted three times. *, p<0.05. Oocyte development is accompanied by a change in chromatin configuration, the so-called non-surrounded nucleolus (NSN) to surrounded nucleolus (SN) configuration, which is associated with acquisition of developmental competence [15]. This transition was modestly inhibited in mutant oocytes; whereas in WT oocytes about 75% of the oocytes are in the SN configuration, we found that 46% and 51% were in the SN configuration for Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and Hdac2−/− oocytes, respectively.

Histological analysis of ovarian sections was conducted using ovaries from mice 18-days of age to capture the full spectrum of follicle development; the size of mutant ovaries was smaller than ovaries present in wild-type mice (4.25±0.12 mg vs 2.46±0.18, n = 5, p = 0.005). The analysis revealed that primary, secondary, and antral follicles were observed in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− ovaries (Figure 1D). Although there were no differences in the number of primordial and primary follicles, mutant ovaries had more secondary follicles but fewer antral follicles than WT ovaries (Figure 1E). Thus, development of secondary follicles to antral follicles in mutant mice appeared either delayed or inhibited, with the decrease in the number of antral follicles being similar to the increase in the number of secondary follicles. These results demonstrated that in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice oocyte development was mainly blocked at the secondary follicle stage, and one allele of Hdac1 was not sufficient to overcome this block, supporting our previous conclusion that HDAC2 is the major HDAC in oocyte development [14]. Last, we observed no overt sign of oocyte degeneration in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice, which is in striking contrast to the increased incidence of oocyte degeneration in Hdac1 : 2−/− oocytes [14].

Reduced Transcription in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− Growing Oocytes Is Accompanied by Histone H3K4me1-3 Demethylation but Not Apoptosis

Our previous study characterizing the phenotype of Hdac1 : 2−/− oocytes was performed with 12-day-old mice [14]. Accordingly, we conducted studies regarding transcription and histone modifications using Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes collected on day-12 post-partum to make valid comparisons. Hdac2 transcripts were reduced by >95% in oocytes obtained from 12-day-old Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice, whereas Hdac1 mRNA level only decreased ∼15% (Figure 2A), which was reflected by a dramatic decrease in the nuclear staining of HDAC2 and only modest decrease (<15%) in HDAC1 nuclear staining (Figure 2B). The small decrease in Hdac1 mRNA likely reflects a compensatory increase in Hdac1 expression in face of loss of Hdac2 [14]. Similar to double mutant oocytes [14], there was an increase in acetylation of both histone H3 and H4 on specific lysine residues (Figure 2C and 2E).

Transcription was reduced by ∼20%, as assayed by EU incorporation, in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes when compared to WT oocytes (Figure 2D and 2E), being intermediate when compared to Hdac1 : 2−/− oocytes in which transcription is reduced by 40% [14]. Hdac2−/− oocytes did not exhibit any significant decrease in the extent of EU incorporation relative to WT (53±4 relative units vs 48±2 relative units, respectively; p>0.20. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM, and the number of oocytes examined was 16 and 24, respectively). We also observed a significant decrease in the intensity of H3K4me1&2 (∼20%) and H3K4me3 (∼40%) nuclear staining in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes (Figure 2D and 2E); active promoters are marked in general by trimethylated H3K4 (H3K4me3), whereas dimethylated H3K4 (H3K4me2) is often found in the coding region [16], [17]. A decrease in H3K4me1 of ∼20%, and a decrease in H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 of ∼35% and 60%, respectively were observed in Hdac1 : 2−/− oocytes (Figure 3 and Fig. 6D in [14]). By using antibodies that specifically recognize CTD S2 phosphorylation, which is a marker for RNA polymerase II engaged in transcription [18], a significant reduction (∼20%) was observed in CTD S2 phosphorylation in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− growing oocytes (Figure 2D and 2E). This decrease was consistent with the 20% decrease in global transcription.

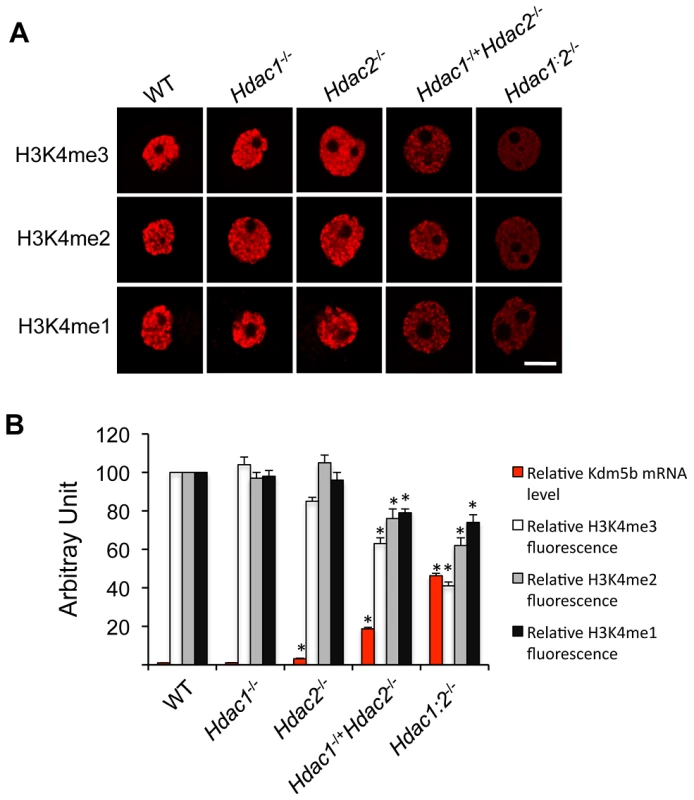

Fig. 3. Loss of HDAC1/2 leads to H3K4me1-3 demethylation and up-regulation of KDM5B.

(A) Immunocytochemical detection of H3K4me1, H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 in oocytes obtained from mice 12-days-of-age and lacking different combinations of Hdac1 and Hdac2. For each histone variant, at least 20 oocytes for each genotype were analyzed, and the experiment was conducted 3 times. Shown are representative images and only the nucleus is shown. The bar corresponds to 10 µm. (B) Quantification of the data shown in panel A and relative abundance of Kdm5b mRNA in different genotype oocytes obtained from mice 12-days-of-age. For immunoflurosecence quantification, the nuclear staining intensity of H3K4me1-3 in the WT oocytes was set to 100. The relative abundance of Kdm5b transcript was assayed by qRT-PCR and expressed relative to WT Kdm5b mRNA level that was set as 1. UBF was used as internal control. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. We previously observed a 40-fold increase in the amount of Kdm5b transcript in Hdac1 : 2−/− oocytes and no change in Hdac1−/− oocytes [14]; KDM5B is apparently the only histone lysine demethylase that can demethylate H3K4me3, H3K4me2 and H3K4me1 [19]. Kdm5b transcripts were also increased, as determined by qRT-PCR, by 18-fold in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes and 3-fold in Hdac2−/− oocytes. The extent of up-regulation of Kdm5b transcripts was related to the extent of loss of Hdac1 and Hdac2, with a corresponding decrease in histone H3K4me1-3 (Figure 3B). These results suggest that KDM5B plays a significant role in establishing the steady-state amount of methylated histone H3K4. In contrast to the dramatic increase in TRP53K379 acetylation that occurs in Hdac1 : 2−/− oocytes [14] and results in increased TRP53 activity [20], [21], TRP53 was not hyperacetylated in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes (Figure 2D and 2E), consistent with apoptosis not being observed in oocytes from these mice. The absence of TRP53 acetylation suggests that only one allele of Hdac1 or Hdac2 is sufficient to prevent increased TRP53 activity in growing oocytes.

Depletion of Maternal HDAC2 Leads to Hyperacetylation of H4K16 and Defective Chromosome Condensation and Segregation during Oocyte Maturation

Although most Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes were arrested within secondary follicles (Figure 1D and 1E), a small number of nearly full-grown oocytes could be recovered from Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− ovaries (Figure 1B). A single mutant of Hdac1 or Hdac2 has no apparent effect on oocyte maturation and subsequent preimplantation development [14] and Figures S1 and S2). We next asked if depletion of HDAC2 combined with a reduction of HDAC1 has any effect on oocyte maturation by using Hdac−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes.

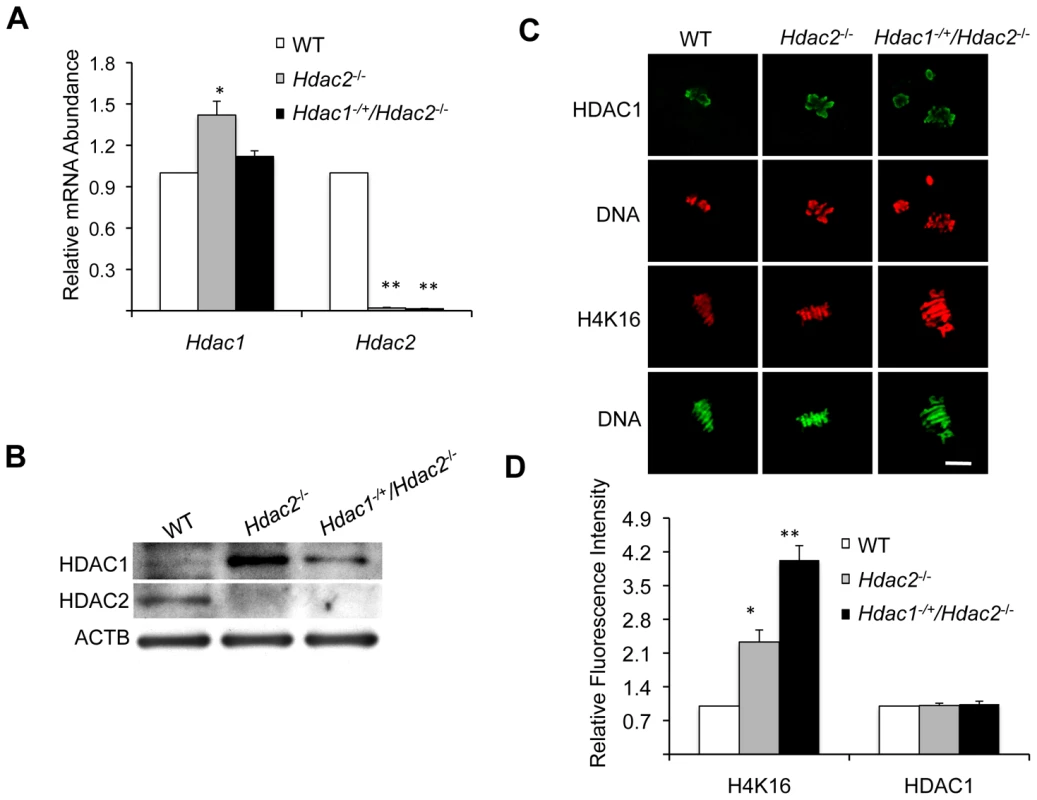

We first checked Hdac1 and Hdac2 expression in full-grown Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes. qRT-PCR revealed that Hdac2 mRNA was reduced by >98% in Hdac1+/−/Hdac2−/− full-grown oocytes (Figure 4A). Hdac1 mRNA levels, however, showed no difference between Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and WT oocytes (Figure 4A), which suggests an ∼2-fold compensatory increase in Hdac1 expression in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes. Consistent with these results, the amount of HDAC1 protein exhibited a mild increase in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes when compared to WT oocytes (Figure 4B), whereas there was a significant increase of both Hdac1 mRNA and HDAC1 protein in Hdac2−/− oocytes (Figure 4A and 4B). Because the amount of HDAC1 present in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and Hdac2−/− oocytes was similar to or more than that in WT oocytes, Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and Hdac2−/− oocytes provide a system to assess the role of maternal HDAC2 in oocyte maturation and subsequent fertilization and preimplantation development.

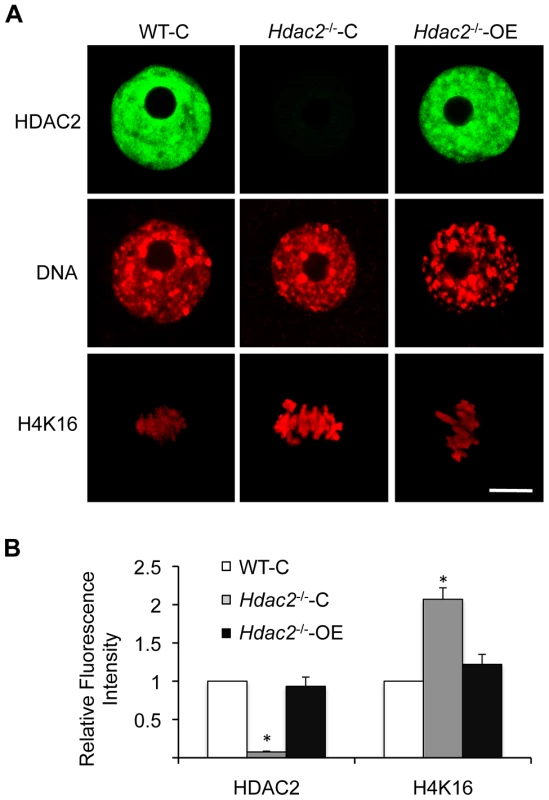

Fig. 4. Depletion of maternal HDAC2 results in increased histone H4K16 acetylation following oocyte maturation.

(A) Relative abundance of Hdac1 and Hdac2 transcripts in full-grown oocytes obtained from WT, Hdac2−/− and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice. Data are expressed relative to that in WT oocytes. The experiment was performed four times and the data expressed as mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.001. (B) Immunoblot analysis of HDAC1 and HDAC2 expression in WT and mutant full-grown oocytes; total protein was extracted from fully-grown oocytes (180 for HDAC1 and 80 for HDAC2) obtained from WT, Hdac2−/− and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice for immunoblotting. The experiment was conducted 3 times, and similar results were obtained in each case. ACTB was used as a loading control. (C) Immunocytochemical detection of HDAC1 and histone H4K16 acetylation in WT, Hdac2−/− and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− MII eggs; at least 20 oocytes from each genotype were analyzed, and the experiment was conducted 3 times. Shown are representative images and the DNA was stained with Sytox Green (green) or propidium iodide (Red). The bar corresponds to 10 µm. (D) Quantification of the data shown in panel C. Staining intensity of different proteins in WT eggs was set to 1 and the data are expressed as mean ± SEM. At least 20 eggs for each genotype and for each detected protein were analyzed; the experiment was conducted three times. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.001. Genome-wide histone deacetylation mediated by HDACs at several lysine residues occurs during oocyte maturation in mouse [22], [23], [24] and pig [25]. The identity of the responsible HDACs, however, is poorly defined in mouse. Accordingly, we first assessed the effect of deleting maternal HDAC2 on histone acetylation during oocyte maturation. Remarkably, immunostaining revealed that although the amount of HDAC1 associated with chromosomes was unchanged in mutant oocytes, the acetylation state of histone H4K16 was affected, being increased ∼2.3-fold in Hdac2−/− and ∼4-fold in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− MII eggs (Figure 4C and 4D); the maturation-associated deacetylation of histone H4K5, H4K8, H4K12, H3K4, H3K9, and H3K14 appeared to occur normally in these cells (Figure S3). It was unlikely that an increase in MYST1, an H4K16-specific histone acetyltransferase [26] and largely responsible for H4K16 acetylation [27], accounted for the observed increase in acetylated H4K16 following maturation because there was no obvious change in the amount of MYST1 protein in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− or Hdac2−/− oocytes (Figure S4A). The amount of acetylated H416 was increased in growing Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes, suggesting nuclear HDAC2 can deacetylate H4K16 (Figure 2C and 2D). Nuclear HDAC2 in full-grown oocytes, however, appeared unable to deacetylate H4K16 because similar amounts of acetylated H4K16 were observed in full-grown WT and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes (Figure S4B).

The increased acetylation of H4K16 following maturation of mutant oocytes was presumably due to loss of HDAC2 activity because Hdac2−/− oocytes injected with an Hdac2 cRNA, but not an Egfp cRNA, exhibited the maturation-associated decrease in acetylated H4K16 to a similar degree as observed in wild-type oocytes (Figure 5). Note that HDAC2 was expressed to similar levels in mutant oocytes when compared to wild-type oocytes, minimizing the likelihood that deacetylation of H4K16 was due to off-targeting effects. In addition, chromosomes appeared less condensed in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and Hdac2−/− MII eggs; whereas only 2.4% of WT eggs (4 out of 163) had chromosomes that appeared not fully condensed, this incidence increased to 30.8% (28 out of 91) and 44.9% (40 out of 89) in Hdac2−/− and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− MII eggs, respectively.

Fig. 5. Expression of HDAC2 in Hdac2−/− oocytes restores maturation-associated deacetylation of histone H4K16.

(A) Mutant oocytes were injected with a cRNA (0.4 µg/µl) encoding either Egfp (Hdac2−/−-C) or Hdac2 (Hdac2−/−-OE) and incubated 24 h in CZB containing milrinone to prevent maturation; controls were wild-type oocytes (WT-C). A portion of the cells was removed for immunoctyochemical detection of HDAC2 whereas the other portion was allowed to mature following transfer to milrinone-free medium. The eggs were then processed for immunocytochemical detection of acetylated histone H4K16. At least 8 cells were analyzed in each group. Shown are representative images. DNA was counterstained with propidium iodide. The bars corresponds to 10 µm. (B) Quantification of the relative amount of acetylated histone H4K16. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *, p<0.01. Fig. 6. Loss of maternal HDAC2 causes defective chromosome condensation and congression in MII eggs.

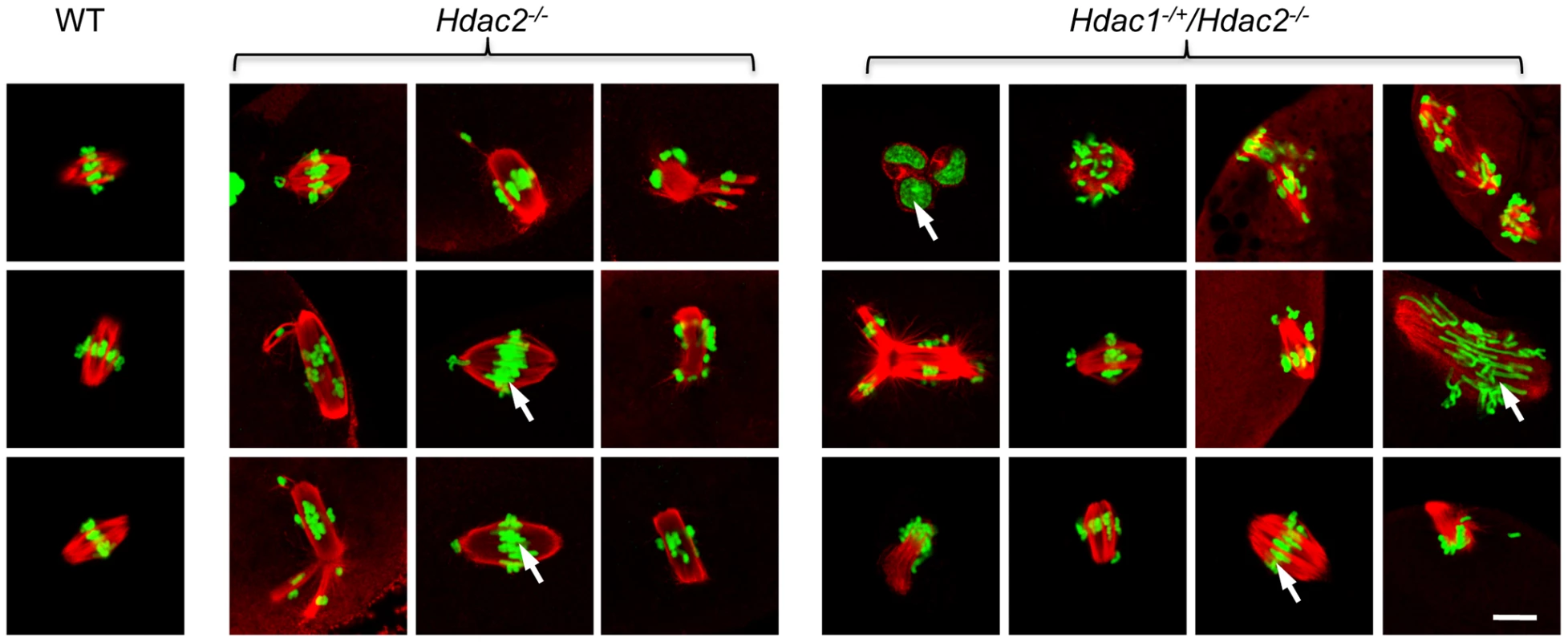

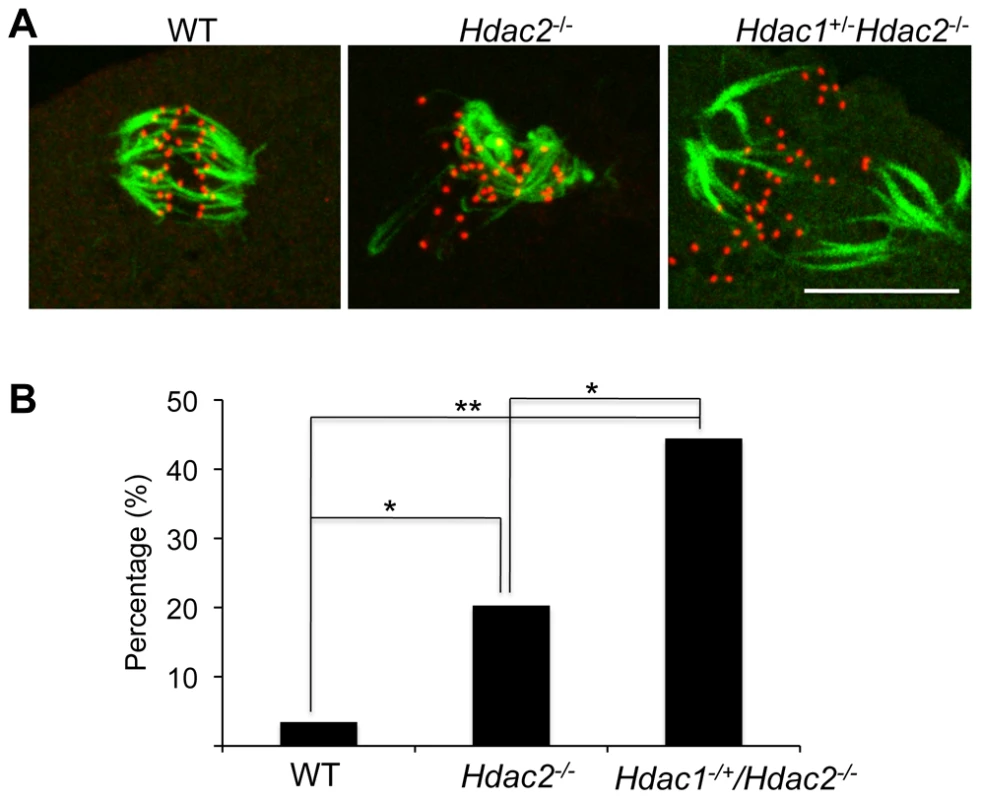

Spindle morphology in WT, Hdac2−/− and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− MII eggs. MII eggs were fixed and stained with anti-TUBB antibody (red); DNA was counterstained with Sytox green. Representative images are shown. The bar corresponds to 10 µm. The effect of deleting Hdac1 and Hdac2 on the acetylation state of H4K16 and chromosome condensation next led us to examine spindle formation and chromosome alignment in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and Hdac2−/− eggs following oocyte maturation. Analysis of meiotic spindle configurations in MII eggs revealed a significant increase in the proportion of eggs with abnormal spindles and misaligned chromosome in Hdac2−/− and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− eggs when compared to WT eggs (Table 1 and Figure 6). As anticipated the incidence of aneuploidy was increased in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and Hdac2−/− eggs (Table 2 and Figure S5). Absence of HDAC2 protein was likely the proximate cause for the observed increased incidence of abnormal spindles and misaligned chromosomes because over-expressing HDAC2 in Hdac2−/− oocytes restored, in large part, the WT phenotype (Figure 7).

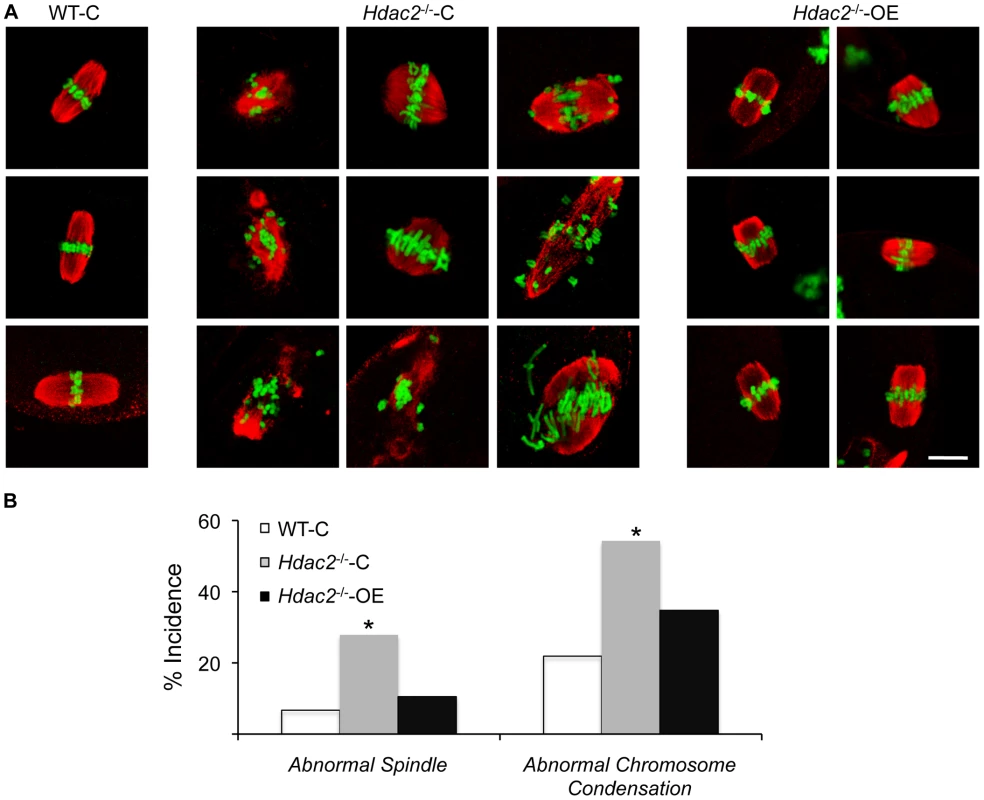

Fig. 7. Expression of HDAC2 in Hdac2−/− oocytes restores normal chromosome condensation and spindle formation in MII eggs.

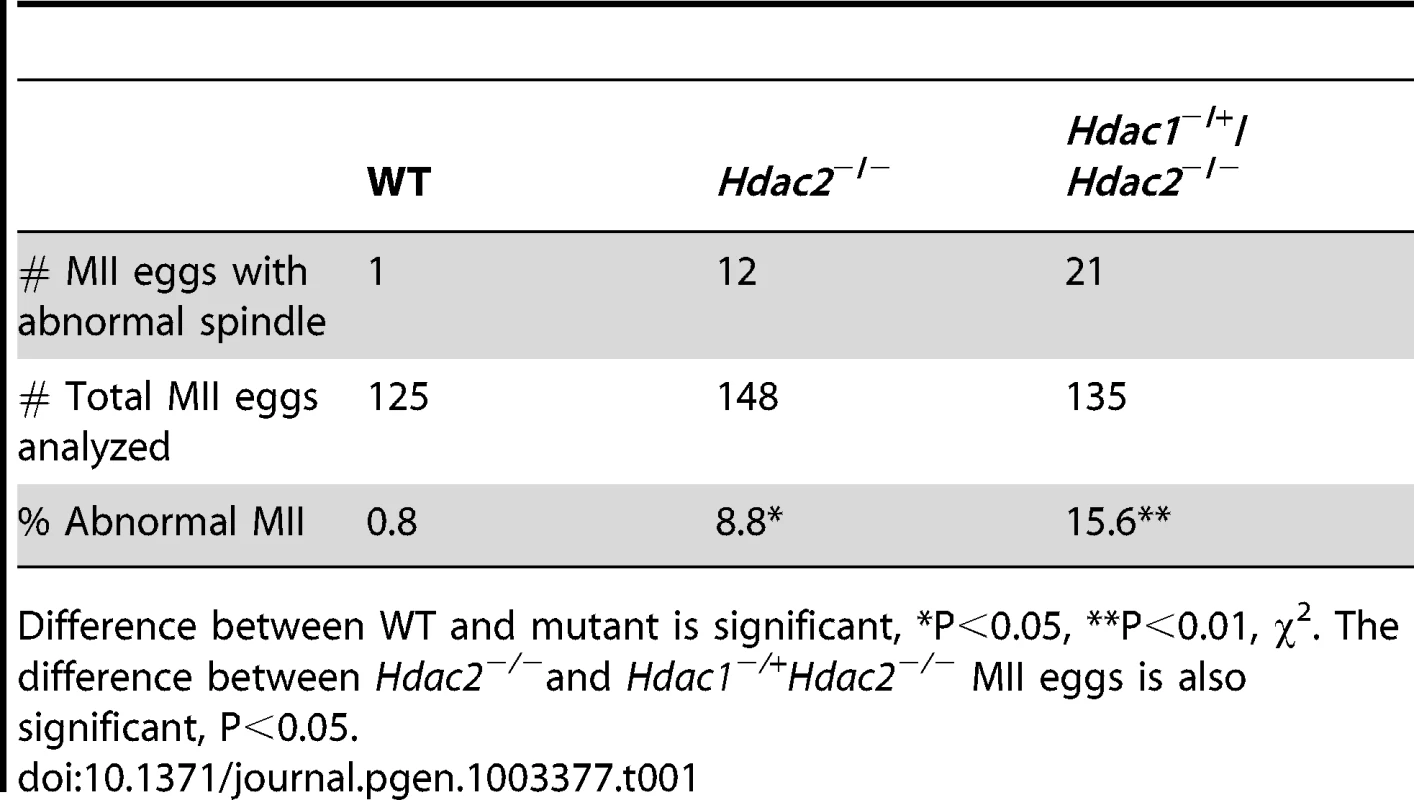

(A) Spindle morphology and chromosome alignment in MII eggs. Mutant oocytes were injected with a cRNA (0.4 µg/µl) encoding either Egfp (Hdac2−/−-C) or Hdac2 (Hdac2−/−-OE) and incubated 24 h in CZB containing milrinone to prevent maturation; controls were wild-type oocytes injected with Egfp cRNA (WT- C). The oocytes were allowed to mature following transfer to milrinone-free medium overnight. MII eggs were fixed and stained with ß-tubulin antibody (red); DNA was counterstained with Sytox green (green). Shown are representative images. The bar corresponds to 10 µm. (B) Frequency of abnormal spindles and abnormal chromosome condensation in WT-C, Hdac2−/−-C and Hdac2−/−-OE MII eggs. 104 WT-C eggs, 104 Hdac2−/−-C eggs and 76 Hdac2−/−-OE eggs were analyzed respectively. *, p<0.05, χ2. Tab. 1. Incidence of abnormal spindles in Hdac mutant MII eggs.

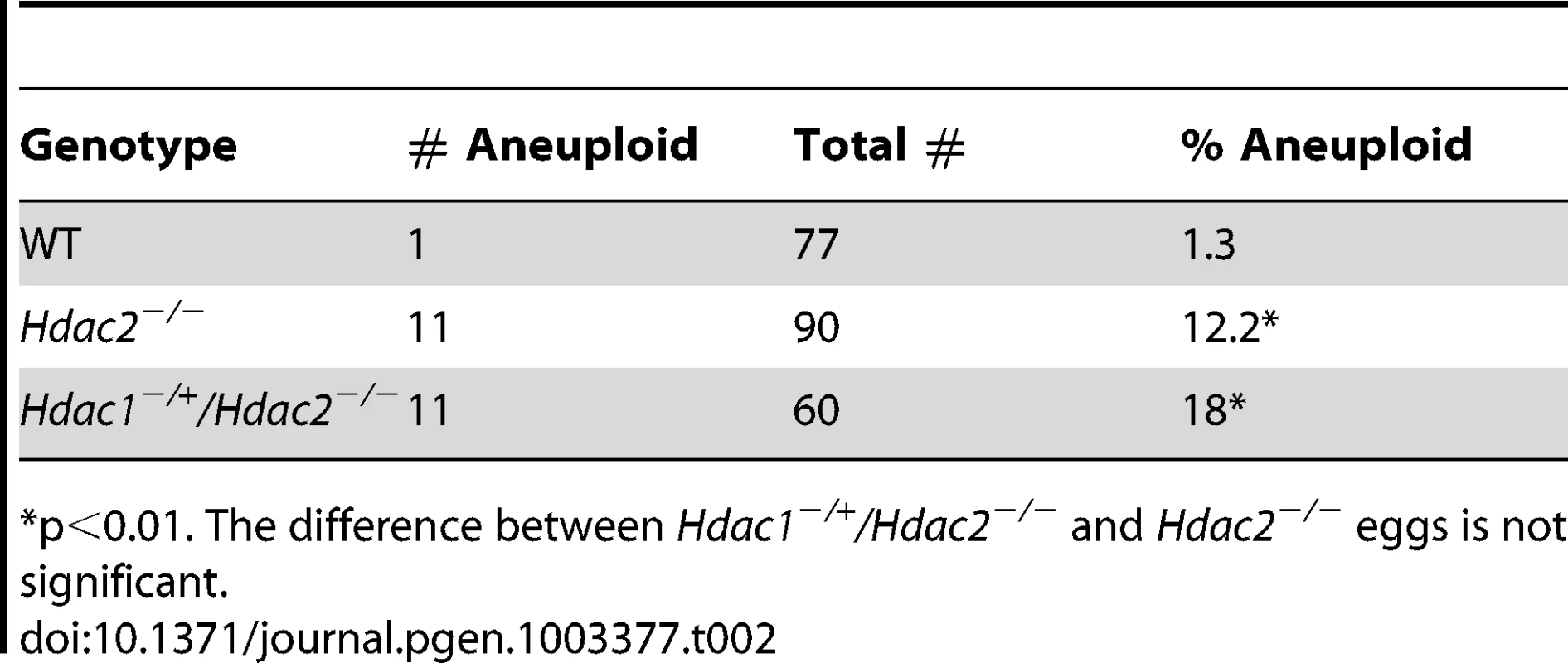

Difference between WT and mutant is significant, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, χ2. The difference between Hdac2−/−and Hdac1−/+Hdac2−/− MII eggs is also significant, P<0.05. Tab. 2. Incidence of aneuploidy in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and Hdac2−/− eggs.

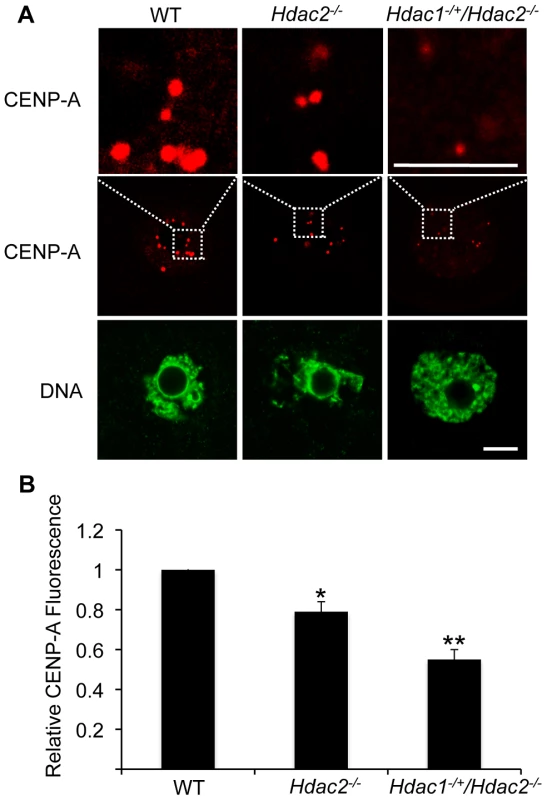

p<0.01. The difference between Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and Hdac2−/− eggs is not significant. In somatic cells, histone hyperacetylation can interfere with kinetochore assembly [28] and in budding yeast, which have 125 bp “point” centromeres (which contrasts to 0.1–5 Mb bp “regional” centromeres in fission yeast and humans), hypoacetylation of H4K16 is critical to maintain kinetochore function [29]. Hyperacetylation of H4K16 in oocyte lacking HDAC2, therefore, could also compromise kinetochore function and lead to the increased incidence of misaligned chromosomes on the spindle. Such appears to be the case. Most spindle microtubules depolymerize at low temperature, except for kinetochore microtubules, which are preferentially stabilized [30], i.e., compromised kinetochore function leads to a decrease in the number of cold-stable microtubules. Finding that the incidence of kinetochores, as detected by CREST staining, not associated with cold-stable microtubules was significantly increased in mutant oocytes strongly implies that kinetochore function is compromised (Figure 8). This conclusion is further buttressed by observing less CENP-A staining at centromeres in mutant oocytes (Figure 9).

Fig. 8. Loss of maternal HDAC2 impairs kinetochore-microtubule attachment in MI oocytes.

(A) Full-grown oocytes from WT, Hdac2−/− and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice were matured to MI by culturing them in CZB medium for 7 h prior to assaying for the presence of cold-stable microtubules. Kinetochores were detected by immunocytochemistry using CREST autoimmune serum (red) and anti-TUBB antibody (green) was used to detect microtubules. Shown are representative images. The bar corresponds to 10 µm. (B) Frequency of abnormal spindles and impaired kinetochore-microtubules attachment in WT, Hdac2−/−and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− MI oocytes. 58 WT oocytes, 69 Hdac2−/− oocytes and 54 Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes were analyzed respectively. *, p<0.05, **, p<0.01, χ2. Fig. 9. Deletion of maternal Hdac2 leads to reduced CENP-A expression in mouse oocytes.

(A) Immunocytochemical detection of CENP-A in WT, Hdac2−/− and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− full-grown oocytes; at least 20 oocytes from each genotype were analyzed, and the experiment was conducted 2 times. Shown are representative images and DNA was counterstained with Sytox green (green). The bar corresponds to 10 µm. The upper row shows an enlargement of the region in the outlined box. (B) Quantification of the data shown in panel A. Staining intensity of different proteins in WT eggs was set to 1 and the data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Signal intensities relative to WT in Hdac2−/− and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− are 81±4%, and 55±6% respectively. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01. Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− Eggs Are Fertilized but Fail to Initiate DNA Replication

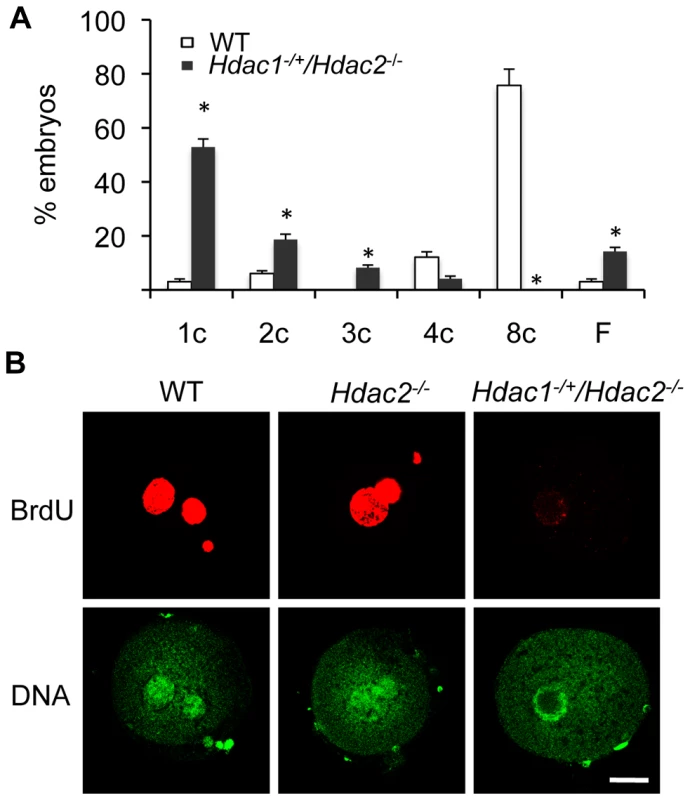

The incidence of aneuploidy in Hdac2−/− eggs could account for the observed sub-fertility in mutant female mice, but would not account for the infertility in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice. Accordingly we ascertained whether Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− eggs could be fertilized, and if so assessed their ability to develop. Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− eggs were readily fertilized as evidenced by formation of a male and female pronucleus; only small fraction (∼15%) of these eggs failed to be fertilized. When Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− female mice were mated to wild-type males, no blastocysts were recovered following development in vivo. Performing a similar mating in which 1-cell embryos were recovered and then permitted to develop in vitro demonstrated that most Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− embryos arrested at the 1-cell (53%) and 2-cell (∼20%) stages, and a higher incidence of fragmentation was observed (Figure 10A).

Fig. 10. Deletion of maternal HDAC2 results in failure to replicate DNA 1-cell embryos.

(A) Embryos derived from Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− females crossed to WT males arrest early in development. Results are presented as % embryos (average) ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. Abbreviations: c, cell; F, fragmented. (B) Confocal images of WT, Hdac2−/− and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− 1-cell embryos in which the incorporation of BrdU was detected by immunocytochemistry. Shown are representative images and DNA was counterstained with Sytox green (green). The experiment was conducted twice and at least 12 embryos were analyzed for each group. Only one of the two pronuclei was in the focal plane for the Hdac1+/−/Hdac2−/− sample. The bar corresponds to 10 µm. The high incidence of failure of Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− 1-cell embryos to cleave to the 2-cell stage led us to examine whether failure to undergo DNA replication was the cause. Whereas BrdU was readily incorporated by zygotes obtained from WT and Hdac2−/− eggs, all zygotes obtained from Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− eggs failed to incorporate BrdU (Figure 10B). The 2-cell embryos observed following insemination of Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− eggs, therefore, were likely the products of pseudo-cleavage. Last, BrdU incorporation by zygotes obtained from Hdac2−/− eggs suggests that the up-regulation of HDAC1 in Hdac2−/− oocytes compensates for loss of HDAC2.

Deleting both Hdac1 and Hdac2 in dividing cells results in a cell cycle block in G1 phase through induction of expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors P21 and P57 [9]. Due to the similar phenotype observed in zygotes derived from Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− eggs, we asked whether a similar situation occurred. Although there was an increased abundance of p57 and p21 transcripts in these zygotes compared to WT, there was no obvious increase in the amount of P57 or P21 protein (Figure S6A and S6B).

DNA replication in 1-cell embryos appears to require recruitment of two maternal mRNAs during maturation, namely, CDC6 and ORC6L [31], [32]. Cdc6 and Orc6l mRNAs were effectively recruited during maturation as evidenced by strong fluorescence signal observed in the pronuclei (Figure S6C); little or no CDC6 or ORCL protein is present in oocytes [31], [32]. This finding minimizes the likelihood that insufficient amounts of CDC6 and ORC6L protein were the cause for failure of fertilized Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− eggs to initiate DNA replication.

Discussion

We previously demonstrated that specifically deleting in oocytes both Hdac1 and Hdac2 genes led to developmental failure beyond the secondary follicle stage, the likely consequence of a 40% decrease in transcription, a massive perturbation in the transcriptome, and TRP53 hyperacetylation leading to apoptosis. The results reported here extend our understanding of HDAC1 and HDAC2 functions during oocyte development by identifying processes they control during oocyte maturation and following fertilization.

The ability of Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− or Hdac2−/− oocytes to reach the nearly full-grown or full-grown stage within preovulatory antral follicles is likely a consequence that they fail to undergo apoptosis because TRP53 is not hyperacetylated. Nevertheless, only a small fraction of Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes develop beyond the secondary follicle stage, whereas development beyond the secondary follicle stage is quite robust in Hdac2−/− oocytes. This difference may reflect that global transcription is reduced by 20% in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes but unaffected in Hdac2−/− oocytes. The perturbation in transcription in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes could impact the communication that exists between oocytes and the surrounding granulosa/cumulus cells and is essential for both oocyte growth and follicle cell proliferation [33]. Although not determined here, the transcriptome of Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes is likely dramatically perturbed as it is in double knock out oocytes [14]. That such an alteration could compromise follicle cell function, is supported by our finding that whereas ovarian weight increases ∼2-fold following eCG priming of 21-day-old WT mice, ovaries from mutant mice fail to respond (data not shown). We also find that deleting Hdac2 results in an increased incidence of aneuploidy that is associated with hyperacetylation of H4K16 following oocyte maturation, a finding implicating HDAC2 in chromosome condensation and segregation. Last, depletion of HDAC2 combined with reduction of HDAC1 in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes results in a subpopulation that can mature to MII, but following egg activation, fail to replicate their DNA.

There is no apparent effect on fertility of Hdac1−/−/Hdac2−/+ mice [14], whereas Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− mice are infertile, their infertility attributed to a combination of defects in oocyte development, maturation, and embryo development. These results provide further support that HDAC2 plays a more prominent role during oocyte development, whereas HDAC1, which is zygotically expressed, is the major HDAC regulating preimplantation development [13]. HDAC1 function during oocyte maturation and following fertilization remains less defined. The amount of HDAC1 protein in Hdac1−/− full-grown oocytes is ∼55% that of WT oocytes (Figure S1B), confounding analysis of HDAC1 function because such mice are fully fertile [14]. The highest levels of Hdac1 expression are in the primordial and primary follicle stages [14], [34], which may explain why the Zp3-Cre mediated strategy did not effectively deplete HDAC1; the Zp3 promoter becomes active during the primordial to primary follicle transition [35].

Oocyte growth is accompanied by a transition from the so-called non-surrounded nucleolus (NSN) configuration in which condensed chromatin does not surround the nucleolus to surrounded nucleolus (SN) configuration that is characterized by highly condensed chromatin around the nucleolus [36], [37]. During this transition, which is uncoupled for the onset of transcriptional quiescence [22], [38], [39], there is an increase in both histone acetylation and methylation [40]. These increases that occur during oocyte growth are not affected in Hdac2−/− oocytes (Figure S7A, S7B), i.e., full-grown mutant SN oocytes display the increase whereas mutant NSN oocytes do not.

Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes that develop beyond the secondary follicle stage and are capable of undergoing meiotic maturation display two phenotypes. One phenotype is a failure to condense fully chromosomes (see below for further discussion of HDAC2 in chromosome dynamics). For those oocytes that mature to MII, the phenotype is a failure to undergo DNA replication following insemination. Whether the failure to replicate DNA is directly linked to altered histone acetylation or a consequence of perturbed transcription during oocyte development/acetylation of non-histone proteins is unknown. In general, however, there is a positive relationship between histone acetylation and DNA replication ([41] and references therein), possibly a consequence of increased chromatin accessibility that facilitates pre-replicative complex assembly. Last, the observed early developmental arrest is similar to several maternal-effect mutants (e.g., Npm2, Stella, Zar1, Hsf1, MLL2, and Mater) [38], [39], [42]–[45], which arrest primarily at the 1-2-cell stage. No DNA replication defects, however, were reported for these mutants, suggesting a different mechanism for developmental arrest.

Mouse oocyte maturation is accompanied by a global decrease in acetylated H3 and H4 histones [22]–[24], but the responsible HDACs have yet to be identified. Histone H3 and H4 deacetylation are not observed during M-phase for preimplantation embryos, except for deacetylation of H4K5 [23]. A similar situation is observed in NIH 3T3 cells, i.e., only H4K5 is deacetylated during M phase [23]. HDACs are clearly active in full-grown GV-intact oocytes because treatment with TSA, an HDAC inhibitor, results in increased histone acetylation [22]. Likewise, histone hyperacetylation is observed in growing oocytes in which Hdac1 and Hdac2 have been specifically deleted [14]. The amount of acetylated histone in GV-intact oocytes, therefore, represents a steady-state level reflecting HDAC and HAT activities. HDAC activity presumably outstrips HAT activity following maturation, thus accounting for the global decrease in histone acetylation. For example, treating MII eggs with TSA does not lead to an increase in histone acetylation, suggesting that HATs are inactive (or cannot access their histone substrates). In contrast, HDACs remain functional (or have access to their histone substrates) because oocytes matured in the presence of TSA fail to exhibit histone deacetylation but do so shortly following transfer to TSA-free medium [23].

HDAC2 is clearly implicated in the maturation-associated deacetylation of H4K16 because an increase in H4K16 is observed in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and Hdac2−/− MII eggs, but not in Hdac1−/−/Hdac2−/+ oocytes (Figure S7C). The apparent greater increase in acetylated H4K16 in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− MII eggs when compared to Hdac2−/− MII eggs (Figure 4C) also suggests a role for HDAC1 in controlling the acetylation state of H4K16, albeit less than that of HDAC2. It should be noted that HDAC2 is not associated with chromosomes in MII eggs [13], [14] and the amount of chromosome-associated HDAC1 is similar in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and Hdac2−/− MII eggs (Figure 4C). Because the total amount of HDAC1 is greater in Hdac2−/− oocytes than in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− oocytes, HDAC1 not associated with chromosomes may be responsible for the decreased amount of acetylated H4K16 in Hdac2−/− eggs when compared to Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− eggs.

To date, only class III HDACs (sirtuins) have been shown to deacetylate specifically histone H4K16 [46]. Taken together, our results suggest that HDAC2 is the HDAC largely responsible for the maturation-associated deacetylation of H4K16, i.e., Class I HDACs are involved. This conclusion contrasts with the conclusion drawn from a study using porcine oocytes that Class I HDACs are not involved and was based on the inability of valproic acid, an inhibitor of Class I HDACs, to inhibit the maturation-associated decrease in histone acetylation [47]. That study, however, only assayed for the acetylation state of histone H4K8 and H3K14, and not H4K16, which could reconcile the different conclusions. Last, other acetylated lysine residues in H3 and H4 are deacetylated during maturation in both Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− or Hdac2−/− oocytes. The identity of the responsible HDACs remains to be determined.

A striking finding reported here is the increase in H4K16 acetylation in virtually all oocytes lacking HDAC2 following oocyte maturation and the associated failure of chromosomes to condense fully and align on the metaphase plate properly in a subpopulation; these failures presumably underlie the observed increased incidence in aneuploidy. That not all mutant oocytes show abnormal chromosome condensation and chromosome alignment despite an increase in H4K16 acetylation in all mutant oocytes is consistent with the finding that when global histone hyperacetylation is induced by treatment with TSA, a substantial fraction [but not all] of the maturing oocytes become euploid (∼40%) [48]. Thus, even when the maturation-associated deacetylation of histones is inhibited and histone acetylation is increased, oocytes/eggs apparently have robust mechanisms to ensure proper chromosome segregation. This ability is consistent with the centrality of oocytes/eggs in reproduction, i.e., robust mechanisms to segregate properly chromosomes are an outcome of strong selective pressures to maintain reproductive fitness. The lower incidence of aneuploidy exhibited in eggs lacking HDAC2, when compared to TSA-treated oocytes, is consistent with mutant oocytes undergoing normal histone deacetylation, except for H4K16.

Acetylation of H4K16 inhibits formation of the higher order 30 nm chromatin structure, and loss of H4K16 shows defects equivalent to the loss of the H4 tails [49]. The increased acetylation of H4K16 in oocytes lacking HDAC2 is likely contributes to the failure of chromosomes to condense fully during oocyte maturation, despite deacetylation of other acetylated lysines. In addition, the increased incidence in mutant oocytes of kinetochores not able to interact with microtubules to form cold-stable microtubules is a functional assay confirming that kinetochore function is indeed compromised. The basis for compromised kinetochore function may reside in histone hyperacetylation interfering with proper kinetochore assembly [50] that leads to the observed decrease in CENP-A staining in mutant oocytes.

Although an age-dependent loss of cohesion can account for the majority of aneuploidies associated with increased maternal age [51], compromised histone deacetylation during maturation may be another source. For example, following maturation of mouse oocytes obtained from old mice, normal deacetylation of H4K8 and H4K12 do not occur, whereas H4K16 and H3K14 are properly deacetylated [48]. Likewise, less deacetylation of histone H4K12 occurs following maturation of oocytes obtained from older women when compared to younger women, and moreover, residual acetylation is correlated with misaligned chromosomes [52]. Thus, compromised histone deacetylation following oocyte maturation in general may result in an increased incidence of aneuploidy by leading to misaligned chromosomes on the meiotic spindle.

In summary, the results reported here provide further evidence for a critical role of HDAC2 in oocyte development and provide explanations for the infertility observed in Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and sub-fertility in Hdac2−/− female mice. In particular, the results suggest that HDAC2 is largely responsible for deacetylation of H4K16 that occurs during oocyte maturation and that such deacetylation is critical for proper chromosome segregation.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Mutants and Collection of 1-Cell Embryos

Details for generating mutant mouse lines, histological analysis of ovaries, oocytes and embryos collection, RNA extraction and real time RT-PCR, immunostaining and immunoblot analysis are described in [14]. Hdac1 or Hdac2 mutants, in which the gene has only been deleted in oocytes, are referred to as Hdac1−/− or Hdac2−/−, respectively. Hdac1-Hdac2 mutants (double mutant) are referred to as Hdac1 : 2−/−. Hdac1 heterozygotes-Hdac2 null oocytes are referred to as Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− and Hdac1 null-Hdac2 heterozygote oocytes are referred to as Hdac1−/−/Hdac2−/+. To obtain 1-cell embryos for BrdU incorporation assays, Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− female mice were superovulated with the injection of 5 IU of PMSG, followed 48 hours later by 5 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). The mice were then mated with B6D2F1/J males (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and 1-cell embryos collected 24 h post hCG administration. Cumulus cells were removed by a brief hyaluronidase treatment (3 mg/ml). All animal experiments were approved by the institutional animal use and care committee and were consistent with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines.

cRNA Preparation and Microinjection

Mouse Hdac2 cDNA was cloned in a PIVT plasmid using standard recombinant DNA techniques. To prepare cRNAs, plasmids were linearized, and capped mRNAs were generated by in vitro transcription using T7 mMESSAGE mMachine (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following in vitro transcription, cRNA was polyadenylated using the PolyA Tailing Kit (Ambion). Synthesized cRNA was then purified using an MEGAclear Kit (Ambion), redissolved in RNase-free water, and stored at −80°C.

Full-grown oocytes were collected from mice of different genotypes and cultured in CZB [53] medium containing 0.2 mM IBMX in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37°C. Microinjection of oocytes was performed as previously described [54]. Injections were done in 10-µl drops of modified Whitten's medium [55] containing 15 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 7 mM Na2HCO3, 10 µg/ml gentamicin and 0.01% PVA containing 2.5 µM milrinone. Approximately 10 pl of EGfp or Hdac2 cRNA was injected into the cytoplasm of GV oocytes using a PLI-100 Pico-Injector (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) on the stage of a Nikon TE2000 microscope equipped with Hoffman optics and Narishige micromanipulators. Following microinjection, oocytes were cultured in CZB plus IBMX for 24 h, and then the injected oocytes were matured by washing and culturing them in IBMX-free CZB medium for 18 h.

In Vitro Transcription Assay

5-Ethynyl uridine (5EU) incorporation assays to detect transcription were performed as previously described [56]. Meiotically incompetent growing oocytes (or embryos) were cultured in the presence of 1 mM 5EU in CZB medium for oocytes or KSOM+AA for embryos [57] for 1 h and then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. 5EU incorporation into RNA was detected using Click-iT RNA Alexa Fluor 488 HCS Assay (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Fluorescence was detected on a Leica TCS SP laser-scanning confocal microscope. The intensity of fluorescence was quantified using Image J software (National institutes of Health) as previously described [58].

Incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU)

Assays were conducted as previously described [32] except the 1-cell embryos were cultured for 5–8 h rather than 30 min in KSOM medium supplemented with 10 µM BrdU (Sigma).

Monastrol Treatment, Kinetochore Immunocytochemistry, and Chromosome Counting

Monastrol treatment, immunocytochemical detection of kinetochores and chromosome counting were performed as previously described [51]. Images were collected with a spinning disk confocal miroscope at 0.4 µm intervals to span the entire region of the spindle, using a 100×1.4 NA oil immersion objective. To obtain a chromosome count for each egg, serial confocal sections were analyzed to determine the total number of kinetochores.

Cold-Stable Microtubule Assay

Wild-type, Hdac2−/− and Hdac1−/+/Hdac2−/− full-grown oocytes were matured in CZB medium for 7 h to MI and then transferred to in MEM medium and placed on ice for 8 min before fixing in 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Immunocytochemistry was performed with CREST autoimmune serum and anti-TUBB antibody to label kinetochores and microtubules, respectively. Images were collected with a spinning disk confocal miroscope at 0.4 µm intervals to span the entire region of the spindle, using a 100×1.4 NA oil immersion objective as described before [51].

TUNEL Labeling Assay

TUNEL (TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling) assays were performed with an In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for immunofluorescence and/or immunoblotting blotting: anti-CDC6 rabbit polyclonal antibody (11640-1AP; Proteintech; IF, 1∶200), anti-P21 mouse monoclonal antibody (556430, BD Pharmingen; IF, 1∶100), anti-P57 rabbit monoclonal antibody (2372-1; Epitomics; IF, 1∶200), anti-ORC6L rat monoclonal antibody (4737; Cell signaling; IF, 1∶100), and anti-CENP-A rabbit monoclonal antibody (2048; Cell signaling; IF, 1∶200). All the other antibodies used in this paper have been described previously [14].

Statistics

Experiments were performed at least three times and the values are presented as mean ± SEM. All proportional data were subjected to an arcsine transformation before statistical analysis. Statistics were calculated with Microsoft Excel software. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. KouzaridesT (2007) Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128 : 693–705.

2. IizukaM, SmithMM (2003) Functional consequences of histone modifications. Curr Opin Genet Dev 13 : 154–160.

3. JenuweinT, AllisCD (2001) Translating the histone code. Science 293 : 1074–1080.

4. de RuijterAJ, van GennipAH, CaronHN, KempS, van KuilenburgAB (2003) Histone deacetylases (HDACs): characterization of the classical HDAC family. Biochem J 370 : 737–749.

5. BrunmeirR, LaggerS, SeiserC (2009) Histone deacetylase HDAC1/HDAC2-controlled embryonic development and cell differentiation. Int J Dev Biol 53 : 275–289.

6. LeBoeufM, TerrellA, TrivediS, SinhaS, EpsteinJA, et al. (2010) Hdac1 and Hdac2 act redundantly to control p63 and p53 functions in epidermal progenitor cells. Dev Cell 19 : 807–818.

7. MontgomeryRL, DavisCA, PotthoffMJ, HaberlandM, FielitzJ, et al. (2007) Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 redundantly regulate cardiac morphogenesis, growth, and contractility. Genes Dev 21 : 1790–1802.

8. MontgomeryRL, HsiehJ, BarbosaAC, RichardsonJA, OlsonEN (2009) Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 control the progression of neural precursors to neurons during brain development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 : 7876–7881.

9. YamaguchiT, CubizollesF, ZhangY, ReichertN, KohlerH, et al. (2010) Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 act in concert to promote the G1-to-S progression. Genes Dev 24 : 455–469.

10. DoveyOM, FosterCT, CowleySM (2010) Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), but not HDAC2, controls embryonic stem cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 : 8242–8247.

11. GuanJS, HaggartySJ, GiacomettiE, DannenbergJH, JosephN, et al. (2009) HDAC2 negatively regulates memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Nature 459 : 55–60.

12. LaggerG, O'CarrollD, RemboldM, KhierH, TischlerJ, et al. (2002) Essential function of histone deacetylase 1 in proliferation control and CDK inhibitor repression. Embo J 21 : 2672–2681.

13. MaP, SchultzRM (2008) Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) regulates histone acetylation, development, and gene expression in preimplantation mouse embryos. Dev Biol 319 : 110–120.

14. MaP, PanH, MontgomeryRL, OlsonEN, SchultzRM (2012) Compensatory functions of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and HDAC2 regulate transcription and apoptosis during mouse oocyte development. Proc Natl Acad Sci, USA 109: E481–489.

15. ZuccottiM, PonceRH, BoianiM, GuizzardiS, GovoniP, et al. (2002) The analysis of chromatin organisation allows selection of mouse antral oocytes competent for development to blastocyst. Zygote 10 : 73–78.

16. StrahlBD, AllisCD (2000) The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403 : 41–45.

17. BergerSL (2007) The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature 447 : 407–412.

18. NiZ, SchwartzBE, WernerJ, SuarezJR, LisJT (2004) Coordination of transcription, RNA processing, and surveillance by P-TEFb kinase on heat shock genes. Mol Cell 13 : 55–65.

19. YamaneK, TateishiK, KloseRJ, FangJ, FabrizioLA, et al. (2007) PLU-1 is an H3K4 demethylase involved in transcriptional repression and breast cancer cell proliferation. Mol Cell 25 : 801–812.

20. ItoA, KawaguchiY, LaiCH, KovacsJJ, HigashimotoY, et al. (2002) MDM2-HDAC1-mediated deacetylation of p53 is required for its degradation. EMBO J 21 : 6236–6245.

21. TangY, ZhaoW, ChenY, ZhaoY, GuW (2008) Acetylation is indispensable for p53 activation. Cell 133 : 612–626.

22. De La FuenteR, ViveirosMM, WigglesworthK, EppigJJ (2004) ATRX, a member of the SNF2 family of helicase/ATPases, is required for chromosome alignment and meiotic spindle organization in metaphase II stage mouse oocytes. Dev Biol 272 : 1–14.

23. KimJM, LiuH, TazakiM, NagataM, AokiF (2003) Changes in histone acetylation during mouse oocyte meiosis. J Cell Biol 162 : 37–46.

24. SarmentoOF, DigilioLC, WangY, PerlinJ, HerrJC, et al. (2004) Dynamic alterations of specific histone modifications during early murine development. J Cell Sci 117 : 4449–4459.

25. EndoT, NaitoK, AokiF, KumeS, TojoH (2005) Changes in histone modifications during in vitro maturation of porcine oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev 71 : 123–128.

26. TaipaleM, ReaS, RichterK, VilarA, LichterP, et al. (2005) hMOF histone acetyltransferase is required for histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol 25 : 6798–6810.

27. SmithER, CayrouC, HuangR, LaneWS, CoteJ, et al. (2005) A human protein complex homologous to the Drosophila MSL complex is responsible for the majority of histone H4 acetylation at lysine 16. Mol Cell Biol 25 : 9175–9188.

28. RobbinsAR, JablonskiSA, YenTJ, YodaK, RobeyR, et al. (2005) Inhibitors of histone deacetylases alter kinetochore assembly by disrupting pericentromeric heterochromatin. Cell Cycle 4 : 717–726.

29. ChoyJS, AcunaR, AuWC, BasraiMA (2011) A role for histone H4K16 hypoacetylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae kinetochore function. Genetics 189 : 11–21.

30. RiederCL (1981) The structure of the cold-stable kinetochore fiber in metaphase PtK1 cells. Chromosoma 84 : 145–158.

31. AngerM, SteinP, SchultzRM (2005) CDC6 requirement for spindle formation during maturation of mouse oocytes. Biol Reprod 72 : 188–194.

32. MuraiS, SteinP, BuffoneMG, YamashitaS, SchultzRM (2010) Recruitment of Orc6l, a dormant maternal mRNA in mouse oocytes, is essential for DNA replication in 1-cell embryos. Dev Biol 341 : 205–212.

33. SuYQ, SugiuraK, EppigJJ (2009) Mouse oocyte control of granulosa cell development and function: paracrine regulation of cumulus cell metabolism. Seminars in reproductive medicine 27 : 32–42.

34. PanH, O'Brien MJ, WigglesworthK, EppigJJ, SchultzRM (2005) Transcript profiling during mouse oocyte development and the effect of gonadotropin priming and development in vitro. Dev Biol 286 : 493–506.

35. LanZJ, GuP, XuX, JacksonKJ, DeMayoFJ, et al. (2003) GCNF-dependent repression of BMP-15 and GDF-9 mediates gamete regulation of female fertility. EMBO J 22 : 4070–4081.

36. DebeyP, SzollosiMS, SzollosiD, VautierD, GirousseA, et al. (1993) Competent mouse oocytes isolated from antral follicles exhibit different chromatin organization and follow different maturation dynamics. Molecular reproduction and development 36 : 59–74.

37. ZuccottiM, PiccinelliA, Giorgi RossiP, GaragnaS, RediCA (1995) Chromatin organization during mouse oocyte growth. Molecular reproduction and development 41 : 479–485.

38. BurnsKH, ViveirosMM, RenY, WangP, DeMayoFJ, et al. (2003) Roles of NPM2 in chromatin and nucleolar organization in oocytes and embryos. Science 300 : 633–636.

39. Andreu-VieyraCV, ChenR, AgnoJE, GlaserS, AnastassiadisK, et al. (2010) MLL2 is required in oocytes for bulk histone 3 lysine 4 trimethylation and transcriptional silencing. PLoS Biol 8: e1000453 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000453

40. KageyamaS, LiuH, KanekoN, OogaM, NagataM, et al. (2007) Alterations in epigenetic modifications during oocyte growth in mice. Reproduction 133 : 85–94.

41. LiuJ, McConnellK, DixonM, CalviBR Analysis of model replication origins in Drosophila reveals new aspects of the chromatin landscape and its relationship to origin activity and the prereplicative complex. Mol Biol Cell 23 : 200–212.

42. ChristiansE, DavisAA, ThomasSD, BenjaminIJ (2000) Maternal effect of Hsf1 on reproductive success. Nature 407 : 693–694.

43. PayerB, SaitouM, BartonSC, ThresherR, DixonJP, et al. (2003) Stella is a maternal effect gene required for normal early development in mice. Curr Biol 13 : 2110–2117.

44. WuX, WangP, BrownCA, ZilinskiCA, MatzukMM (2003) Zygote arrest 1 (Zar1) is an evolutionarily conserved gene expressed in vertebrate ovaries. Biol Reprod 69 : 861–867.

45. TongZB, GoldL, PfeiferKE, DorwardH, LeeE, et al. (2000) Mater, a maternal effect gene required for early embryonic development in mice. Nat Genet 26 : 267–268.

46. VaqueroA, SternglanzR, ReinbergD (2007) NAD+-dependent deacetylation of H4 lysine 16 by class III HDACs. Oncogene 26 : 5505–5520.

47. EndoT, KanoK, NaitoK (2008) Nuclear histone deacetylases are not required for global histone deacetylation during meiotic maturation in porcine oocytes. Biol Reprod 78 : 1073–1080.

48. AkiyamaT, NagataM, AokiF (2006) Inadequate histone deacetylation during oocyte meiosis causes aneuploidy and embryo death in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 : 7339–7344.

49. Shogren-KnaakM, IshiiH, SunJM, PazinMJ, DavieJR, et al. (2006) Histone H4-K16 acetylation controls chromatin structure and protein interactions. Science 311 : 844–847.

50. RobbinsAR, JablonskiSA, YenTJ, YodaK, RobeyR, et al. (2005) Inhibitors of histone deacetylases alter kinetochore assembly by disrupting pericentromeric heterochromatin. Cell Cycle 4 : 717–726.

51. ChiangT, DuncanFE, SchindlerK, SchultzRM, LampsonMA (2010) Evidence that weakened centromere cohesion is a leading cause of age-related aneuploidy in oocytes. Curr Biol 20 : 1522–1528.

52. van den BergIM, EleveldC, van der HoevenM, BirnieE, SteegersEA, et al. (2011) Defective deacetylation of histone 4 K12 in human oocytes is associated with advanced maternal age and chromosome misalignment. Hum Reprod 26 : 1181–1190.

53. ChatotCL, ZiomekCA, BavisterBD, LewisJL, TorresI (1989) An improved culture medium supports development of random-bred 1-cell mouse embryos in vitro. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility 86 : 679–688.

54. KurasawaS, SchultzRM, KopfGS (1989) Egg-induced modifications of the zona pellucida of mouse eggs: effects of microinjected inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Dev Biol 133 : 295–304.

55. WhittenWK (1971) Nutrient requirements for the culture of preimplantation mouse embryo in vitro. Adv Biosci 6 : 129–139.

56. MainigiMA, OrdT, SchultzRM (2011) Meiotic and developmental competence in mice are compromised following follicle development in vitro using an alginate-based culture system. Biol Reprod 85 : 269–276.

57. HoY, WigglesworthK, EppigJJ, SchultzRM (1995) Preimplantation development of mouse embryos in KSOM: augmentation by amino acids and analysis of gene expression. Mol Reprod Dev 41 : 232–238.

58. AokiF, WorradDM, SchultzRM (1997) Regulation of transcriptional activity during the first and second cell cycles in the preimplanation mouse embryo. Dev Biol 181 : 296–307.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Ubiquitous Polygenicity of Human Complex Traits: Genome-Wide Analysis of 49 Traits in KoreansČlánek Alternative Splicing and Subfunctionalization Generates Functional Diversity in Fungal ProteomesČlánek RFX Transcription Factor DAF-19 Regulates 5-HT and Innate Immune Responses to Pathogenic Bacteria inČlánek Surveillance-Activated Defenses Block the ROS–Induced Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein ResponseČlánek Deficiency Reduces Adipose OXPHOS Capacity and Triggers Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Mice

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2013 Číslo 3- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Power and Predictive Accuracy of Polygenic Risk Scores

- Rare Copy Number Variants Are a Common Cause of Short Stature

- Coordination of Flower Maturation by a Regulatory Circuit of Three MicroRNAs

- Ubiquitous Polygenicity of Human Complex Traits: Genome-Wide Analysis of 49 Traits in Koreans

- Genomic Evidence for Island Population Conversion Resolves Conflicting Theories of Polar Bear Evolution

- Mechanistic Insight into the Pathology of Polyalanine Expansion Disorders Revealed by a Mouse Model for X Linked Hypopituitarism

- Genome-Wide Association Study and Gene Expression Analysis Identifies as a Predictor of Response to Etanercept Therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Problem Solved: An Interview with Sir Edwin Southern

- Long Interspersed Element–1 (LINE-1): Passenger or Driver in Human Neoplasms?

- Mouse HFM1/Mer3 Is Required for Crossover Formation and Complete Synapsis of Homologous Chromosomes during Meiosis

- Alternative Splicing and Subfunctionalization Generates Functional Diversity in Fungal Proteomes

- A WRKY Transcription Factor Recruits the SYG1-Like Protein SHB1 to Activate Gene Expression and Seed Cavity Enlargement

- Microhomology-Mediated Mechanisms Underlie Non-Recurrent Disease-Causing Microdeletions of the Gene or Its Regulatory Domain

- Ancient Evolutionary Trade-Offs between Yeast Ploidy States

- Differential Evolutionary Fate of an Ancestral Primate Endogenous Retrovirus Envelope Gene, the EnvV , Captured for a Function in Placentation

- A Feed-Forward Loop Coupling Extracellular BMP Transport and Morphogenesis in Wing

- The Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus Resistance Genes and Are Allelic and Code for DFDGD-Class RNA–Dependent RNA Polymerases

- The U-Box E3 Ubiquitin Ligase TUD1 Functions with a Heterotrimeric G α Subunit to Regulate Brassinosteroid-Mediated Growth in Rice

- Role of the DSC1 Channel in Regulating Neuronal Excitability in : Extending Nervous System Stability under Stress

- –Independent Phenotypic Switching in and a Dual Role for Wor1 in Regulating Switching and Filamentation

- Pax6 Regulates Gene Expression in the Vertebrate Lens through miR-204

- Blood-Informative Transcripts Define Nine Common Axes of Peripheral Blood Gene Expression

- Genetic Architecture of Skin and Eye Color in an African-European Admixed Population

- Fine Characterisation of a Recombination Hotspot at the Locus and Resolution of the Paradoxical Excess of Duplications over Deletions in the General Population

- Estrogen Mediated-Activation of miR-191/425 Cluster Modulates Tumorigenicity of Breast Cancer Cells Depending on Estrogen Receptor Status

- Complex Patterns of Genomic Admixture within Southern Africa

- Yap- and Cdc42-Dependent Nephrogenesis and Morphogenesis during Mouse Kidney Development

- Molecular Networks of Human Muscle Adaptation to Exercise and Age

- Alp/Enigma Family Proteins Cooperate in Z-Disc Formation and Myofibril Assembly

- Polycomb Group Gene Regulates Rice () Seed Development and Grain Filling via a Mechanism Distinct from

- RFX Transcription Factor DAF-19 Regulates 5-HT and Innate Immune Responses to Pathogenic Bacteria in

- Distinct Molecular Strategies for Hox-Mediated Limb Suppression in : From Cooperativity to Dispensability/Antagonism in TALE Partnership

- A Natural Polymorphism in rDNA Replication Origins Links Origin Activation with Calorie Restriction and Lifespan

- TDP2–Dependent Non-Homologous End-Joining Protects against Topoisomerase II–Induced DNA Breaks and Genome Instability in Cells and

- Recurrent Rearrangement during Adaptive Evolution in an Interspecific Yeast Hybrid Suggests a Model for Rapid Introgression

- Genome-Wide Association Study in Mutation Carriers Identifies Novel Loci Associated with Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risk

- Coincident Resection at Both Ends of Random, γ–Induced Double-Strand Breaks Requires MRX (MRN), Sae2 (Ctp1), and Mre11-Nuclease

- Identification of a -Specific Modifier Locus at 6p24 Related to Breast Cancer Risk

- A Novel Function for the Hox Gene in the Male Accessory Gland Regulates the Long-Term Female Post-Mating Response in

- Tdp2: A Means to Fixing the Ends

- A Novel Role for the RNA–Binding Protein FXR1P in Myoblasts Cell-Cycle Progression by Modulating mRNA Stability

- Association Mapping and the Genomic Consequences of Selection in Sunflower

- Histone Deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) Regulates Chromosome Segregation and Kinetochore Function via H4K16 Deacetylation during Oocyte Maturation in Mouse

- A Novel Mutation in the Upstream Open Reading Frame of the Gene Causes a MEN4 Phenotype

- Ataxin1L Is a Regulator of HSC Function Highlighting the Utility of Cross-Tissue Comparisons for Gene Discovery

- Human Spermatogenic Failure Purges Deleterious Mutation Load from the Autosomes and Both Sex Chromosomes, including the Gene

- A Conserved Upstream Motif Orchestrates Autonomous, Germline-Enriched Expression of piRNAs

- Statistical Analysis Reveals Co-Expression Patterns of Many Pairs of Genes in Yeast Are Jointly Regulated by Interacting Loci

- Matefin/SUN-1 Phosphorylation Is Part of a Surveillance Mechanism to Coordinate Chromosome Synapsis and Recombination with Meiotic Progression and Chromosome Movement

- A Role for the Malignant Brain Tumour (MBT) Domain Protein LIN-61 in DNA Double-Strand Break Repair by Homologous Recombination

- The Population and Evolutionary Dynamics of Phage and Bacteria with CRISPR–Mediated Immunity

- Long Noncoding RNA MALAT1 Controls Cell Cycle Progression by Regulating the Expression of Oncogenic Transcription Factor B-MYB

- Surveillance-Activated Defenses Block the ROS–Induced Mitochondrial Unfolded Protein Response

- DNA Topoisomerase III Localizes to Centromeres and Affects Centromeric CENP-A Levels in Fission Yeast

- Genome-Wide Control of RNA Polymerase II Activity by Cohesin

- Divergent Selection Drives Genetic Differentiation in an R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor That Contributes to Incipient Speciation in

- NODULE INCEPTION Directly Targets Subunit Genes to Regulate Essential Processes of Root Nodule Development in

- Spreading of a Prion Domain from Cell-to-Cell by Vesicular Transport in

- Deficiency in Origin Licensing Proteins Impairs Cilia Formation: Implications for the Aetiology of Meier-Gorlin Syndrome

- Deficiency Reduces Adipose OXPHOS Capacity and Triggers Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Mice

- The Conserved SKN-1/Nrf2 Stress Response Pathway Regulates Synaptic Function in

- Functional Genomic Analysis of the Regulatory Network in

- Astakine 2—the Dark Knight Linking Melatonin to Circadian Regulation in Crustaceans

- CRL2 E3-Ligase Regulates Proliferation and Progression through Meiosis in the Germline

- Both the Caspase CSP-1 and a Caspase-Independent Pathway Promote Programmed Cell Death in Parallel to the Canonical Pathway for Apoptosis in

- PRMT4 Is a Novel Coactivator of c-Myb-Dependent Transcription in Haematopoietic Cell Lines

- A Copy Number Variant at the Locus Likely Confers Risk for Canine Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Digit

- Evidence of Gene–Environment Interactions between Common Breast Cancer Susceptibility Loci and Established Environmental Risk Factors

- HIV Infection Disrupts the Sympatric Host–Pathogen Relationship in Human Tuberculosis

- Trans-Ethnic Fine-Mapping of Lipid Loci Identifies Population-Specific Signals and Allelic Heterogeneity That Increases the Trait Variance Explained

- A Gene Transfer Agent and a Dynamic Repertoire of Secretion Systems Hold the Keys to the Explosive Radiation of the Emerging Pathogen

- The Role of ATM in the Deficiency in Nonhomologous End-Joining near Telomeres in a Human Cancer Cell Line

- Dynamic Circadian Protein–Protein Interaction Networks Predict Temporal Organization of Cellular Functions

- Nuclear Myosin 1c Facilitates the Chromatin Modifications Required to Activate rRNA Gene Transcription and Cell Cycle Progression

- Robust Prediction of Expression Differences among Human Individuals Using Only Genotype Information

- A Single Cohesin Complex Performs Mitotic and Meiotic Functions in the Protist

- The Role of the Arabidopsis Exosome in siRNA–Independent Silencing of Heterochromatic Loci

- Elevated Expression of the Integrin-Associated Protein PINCH Suppresses the Defects of Muscle Hypercontraction Mutants

- Twist1 Controls a Cell-Specification Switch Governing Cell Fate Decisions within the Cardiac Neural Crest

- Genome-Wide Testing of Putative Functional Exonic Variants in Relationship with Breast and Prostate Cancer Risk in a Multiethnic Population

- Heteroduplex DNA Position Defines the Roles of the Sgs1, Srs2, and Mph1 Helicases in Promoting Distinct Recombination Outcomes

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Fine Characterisation of a Recombination Hotspot at the Locus and Resolution of the Paradoxical Excess of Duplications over Deletions in the General Population

- Molecular Networks of Human Muscle Adaptation to Exercise and Age

- Recurrent Rearrangement during Adaptive Evolution in an Interspecific Yeast Hybrid Suggests a Model for Rapid Introgression

- Genome-Wide Association Study and Gene Expression Analysis Identifies as a Predictor of Response to Etanercept Therapy in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy