-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Defective Repair of Oxidative Base Lesions by the DNA Glycosylase Nth1 Associates with Multiple Telomere Defects

Telomeres are chromosome end structures and are essential for maintenance of genome stability. Highly repetitive telomere sequences appear to be susceptible to oxidative stress-induced damage. Oxidation may therefore have a severe impact on telomere integrity and function. A wide spectrum of oxidative pyrimidine-derivatives has been reported, including thymine glycol (Tg), that are primarily removed by a DNA glycosylase, Endonuclease III-like protein 1 (Nth1). Here, we investigate the effect of Nth1 deficiency on telomere integrity in mice. Nth1 null (Nth1−/−) mouse tissues and primary MEFs harbor higher levels of Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions at telomeric repeats, in comparison to a non-telomeric locus. Furthermore, oxidative DNA damage induced by acute exposure to an oxidant is repaired slowly at telomeres in Nth1−/− MEFs. Although telomere length is not affected in the hematopoietic tissues of Nth1−/− adult mice, telomeres suffer from attrition and increased recombination and DNA damage foci formation in Nth1−/− bone marrow cells that are stimulated ex vivo in the presence of 20% oxygen. Nth1 deficiency also enhances telomere fragility in mice. Lastly, in a telomerase null background, Nth1−/− bone marrow cells undergo severe telomere loss at some chromosome ends and cell apoptosis upon replicative stress. These results suggest that Nth1 plays an important role in telomere maintenance and base repair against oxidative stress-induced base modifications. The fact that telomerase deficiency can exacerbate telomere shortening in Nth1 deficient mouse cells supports that base excision repair cooperates with telomerase to maintain telomere integrity.

Published in the journal: Defective Repair of Oxidative Base Lesions by the DNA Glycosylase Nth1 Associates with Multiple Telomere Defects. PLoS Genet 9(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003639

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003639Summary

Telomeres are chromosome end structures and are essential for maintenance of genome stability. Highly repetitive telomere sequences appear to be susceptible to oxidative stress-induced damage. Oxidation may therefore have a severe impact on telomere integrity and function. A wide spectrum of oxidative pyrimidine-derivatives has been reported, including thymine glycol (Tg), that are primarily removed by a DNA glycosylase, Endonuclease III-like protein 1 (Nth1). Here, we investigate the effect of Nth1 deficiency on telomere integrity in mice. Nth1 null (Nth1−/−) mouse tissues and primary MEFs harbor higher levels of Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions at telomeric repeats, in comparison to a non-telomeric locus. Furthermore, oxidative DNA damage induced by acute exposure to an oxidant is repaired slowly at telomeres in Nth1−/− MEFs. Although telomere length is not affected in the hematopoietic tissues of Nth1−/− adult mice, telomeres suffer from attrition and increased recombination and DNA damage foci formation in Nth1−/− bone marrow cells that are stimulated ex vivo in the presence of 20% oxygen. Nth1 deficiency also enhances telomere fragility in mice. Lastly, in a telomerase null background, Nth1−/− bone marrow cells undergo severe telomere loss at some chromosome ends and cell apoptosis upon replicative stress. These results suggest that Nth1 plays an important role in telomere maintenance and base repair against oxidative stress-induced base modifications. The fact that telomerase deficiency can exacerbate telomere shortening in Nth1 deficient mouse cells supports that base excision repair cooperates with telomerase to maintain telomere integrity.

Introduction

All eukaryotic linear chromosome ends consist of complex nucleoprotein structures, called telomeres. Telomeres are composed of tandem repeat sequences 5′-(TTAGGG)n-3′ whose lengths vary from about 10 kbps in humans to up to 100 kbps in mice. In mammals, telomere DNA is bound by the shelterin complex, including telomere repeat binding proteins TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 [1]. Telomeres prevent recombinogenic chromosome ends from inducing chromosomal rearrangements that destabilize the eukaryotic genome. Telomere attrition (shortening) or other forms of telomere dysfunction can evoke an ATM - or ATR - dependent DNA damage response that results in 53BP1 and γ-H2AX foci formation at telomeres, Chk1 and Chk2 phosphorylation, and the induction of cell cycle arrest, senescence, or apoptosis [2].

Telomere maintenance involves telomerase extension and telomere recombination, replication, and capping [3]. It is also affected by other factors, the most notable being oxidative stress [4]. Telomere length decreases after each cell division, due to the inability of DNA polymerases to completely replicate DNA ends. However, telomerase counteracts telomere shortening by replenishing telomeric repeats. Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein complex composed of telomerase reverse transcriptase (Tert) and an RNA component (Terc) [3]. In telomerase null mice, telomere length gradually decreases to a critical length, which activates a DNA damage checkpoint primarily in highly proliferating organs, such as bone marrow [5]. Recent data suggests that telomeres pose a challenge to replication machinery, resulting in defects similar to aphidicolin-induced fragile sites possibly caused by replication fork stalling [6], [7]. It has been suggested that the shelterin component, TRF1, might recruit BLM or RTEL helicases to telomeres, thereby helping to resolve G-quadruplex structures that may inhibit telomere replication [7].

Telomeric DNA appears to be more susceptible to damage as a result of exposure to exogenous physical and chemical agents, such as oxidants [8]–[12]. For example, single stranded breaks (SSBs) and base damage preferentially occur in telomeres in human cells with oxidative stress [8], [9]. Furthermore, oxidant-induced telomeric DNA damage triggers a persistent DNA damage response [12]. Although it has been proposed that G-rich telomeric sequence may be more susceptible to oxidative DNA damage [13]–[15], a wide spectrum of oxidized pyrimidine-derivatives, e. g. 5-hydroxycytosine (5-OH-Cyt), 5-hydroxyuracil (5-OH-Ura), and Tg has also been reported [16], [17] and may exist at telomeres. For example, thymine is relatively rich in telomere repeats and could be modified into Tg by oxidation, and Tg might potentially hamper DNA replication [18]–[20]. Furthermore, oxidative base lesions in telomere substrates reduce the binding of telomere binding proteins to telomere DNA [21], [22], which may, in turn, affect telomere maintenance.

Non-bulky oxidative base lesions are primarily repaired by the base excision repair (BER) pathway, and the first step in BER is carried out by a DNA glycosylase, which recognizes and removes damaged bases [23]. Mammalian cells express several glycosylases with overlapping but distinct specificity for various base lesions [23]. For example, 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1 (Ogg1) mostly recognizes oxidized guanine lesions, e.g. 8-oxoG, while Nth1 primarily recognizes oxidized bases other than 8-oxoG, e.g. 5-OH-Cyt, 5-OH-Ura and Tg [23], [24]. Nth1 is highly expressed during early and mid-S phase, suggesting that it plays a role in replicative repair [25]. Ogg1 deficiency results in the accumulation of oxidative 8-oxoG lesions in telomeres and attenuates telomere integrity [22], [26]. However, it is unclear if other types of oxidative base lesions might accumulate at telomeres and if ablation of their repair could affect telomere maintenance. Here, we utilize Nth1 null mice to evaluate these probabilities.

Results

Elevated level of Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions at telomeres in Nth1 deficient mouse tissues and primary MEFs

To determine if oxidative base lesions accumulate at telomeres, genomic DNA was isolated from wild-type and Nth1−/− mouse kidneys and primary MEFs, treated with Endonuclease III, and measured for Endonuclease III-sensitive lesions at telomeres using a quantitative telomere PCR method [27]. E. coli Endonuclease III has similar substrate specificity profiles as mammalian Nth1 and primarily excises oxidized bases including 5-OH-Cyt, 5-OH-Ura and Tg, resulting in abasic sites and subsequently single strand breaks (SSBs) [23] that impair PCR kinetics. The more base lesions are at telomeres, the more DNA nicks are generated by Endonuclease III treatment and hence the higher Ct values are produced. To eliminate interference by other potential DNA replication blocking lesions, e.g. spontaneous DNA strand breaks at telomeres, a duplicate mock digestion was set up for each corresponding sample in which Endonuclease III was excluded. Endonuclease III-sensitive lesions in a sample were normalized by comparing PCR kinetics in the mock - and Endonuclease III - treated samples, i.e. change in cycle threshold (ΔCt = Ct treated - Ct mock) [27]. A standard curve for Endonuclease III-sensitive lesions was generated using synthetic telomere oligonucleotides containing various numbers of Tg lesions (Figure S1A and Table S1) and was used to calculate the relative numbers of Endonuclease III-sensitive lesions per kilobase of telomeric DNA in each sample as described by O'Callaghan et al [27]. As shown in Figure S1B, mock - and Endonuclease III-treated Tg-free telomere oligonucleotides yield comparable Ct values. In contrast, Endonuclease III-treated Tg-containing telomere oligonucleotides show higher Ct values in comparison to mock-treated Tg-containing telomere oligonucleotides (Figure S1B). Similarly, mock-treated genomic DNA from wild-type and Nth1−/− mice have comparable Ct values, while Endonuclease III-treated Nth1−/− mouse genomic DNA displays higher Ct values than Endonuclease III-treated wild-type mouse genomic DNA (Figure S1C). These observations support that difference in PCR kinetics in mock - and Endonuclease III-treated mouse genomic DNA samples is due to cleavage of Endonuclease III-sensitive lesions in the DNA strand.

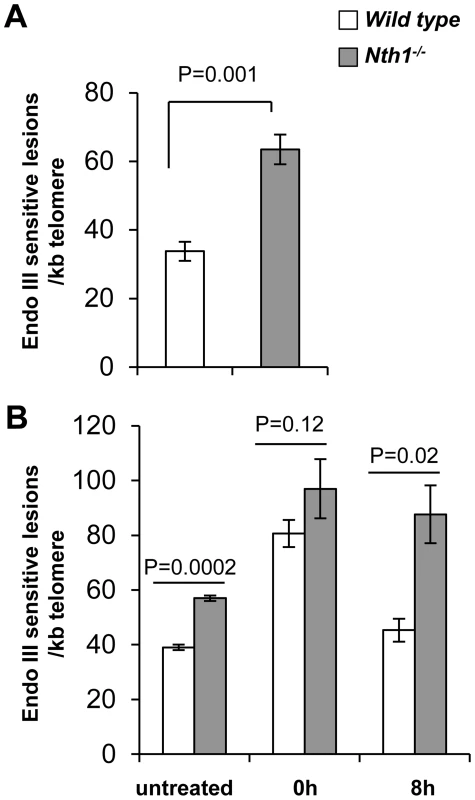

Genomic DNA from Nth1−/− kidney tissue and MEFs has about 2-fold and 1.8-fold more Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions at telomeres, compared to that from wild type (Figure 1A and B). However, Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions in an amplicon within a non-telomere locus (the 36B4 gene) are comparable in wild-type and Nth1−/− kidney tissue and MEFs, in contrast to those within telomeric repeats (Figure S2). Thus, Nth1 deficient mouse cells harbor a higher density of Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions at telomeres. These results are consistent with previous reports that oxidative 8-oxoG lesions and single strand breaks preferentially accumulate at telomeres in mammalian cells [8], [9].

Fig. 1. Detection of oxidative DNA base lesions at telomeres in mice.

Genomic DNA is detected for Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions per kilobase of telomeric DNA by a modified quantitative telomere PCR method. (A) Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions in wild-type and Nth1−/− mouse kidney (n = 6 mice). (B) Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions in primary MEFs (untreated) or MEFs exposed to 5 µM Benzo(a)pyrene for 24 hours followed by recovery for 0 hour or 8 hours. Each sample is analyzed in triplicate. Error bars denote standard deviation. P-values are calculated using a Student's t-test and adjusted using Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate-controlling method [57]. P-values<0.05 are statistically significant using the above method. To determine if ablation of Nth1 function affects oxidative base repair kinetics at telomeres, wild-type or Nth1−/− primary MEFs were treated with an oxidant, benzo[a]pyrene that induces oxidative modifications at DNA [28]. Primary MEFs were exposed to 5 µM benzo(a)pyrene for 24 hours and then recovered for 8 hours. Immediately after exposure (0 hour), an approximately 2-fold increase in the number of Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions is detected at telomeres in wild-type and Nth1−/− MEFs, compared to that in untreated MEFs. Persistent Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions are detected at telomeres during the recovery period in Nth1−/− MEFs, while they return to the basal levels in wild-type MEFs within 8 hours after exposure is terminated (Figure 1B). These data suggest that Nth1 plays an important role in repairing Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions in telomeres in vivo.

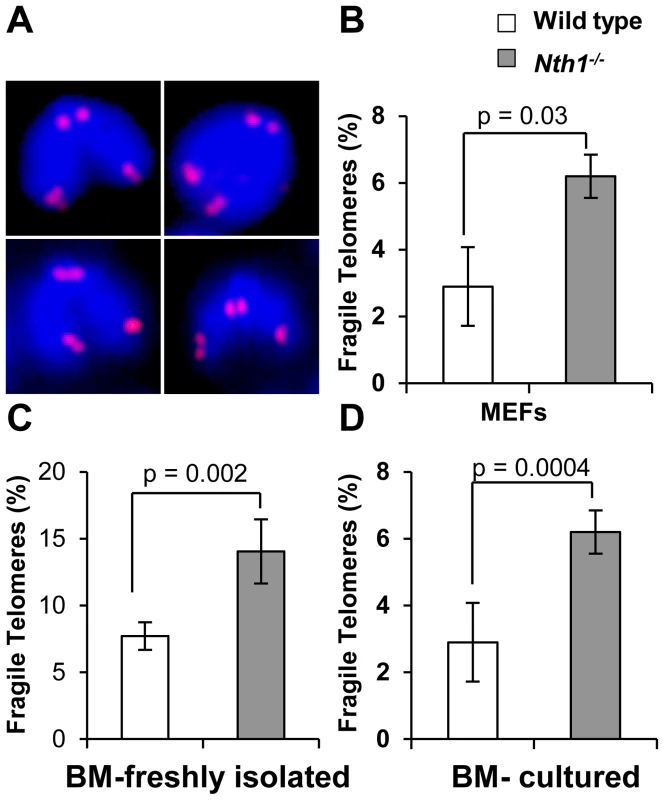

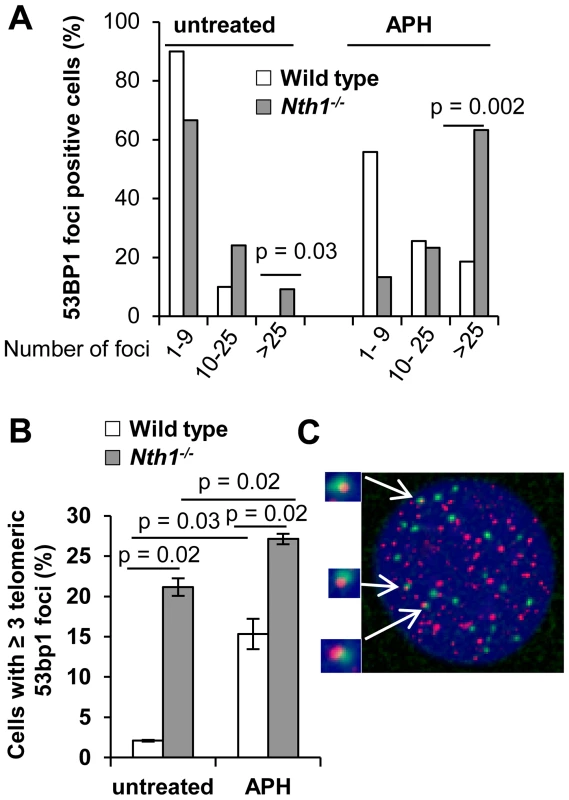

Higher incidence of fragile telomeres in Nth1 deficient mouse cells

Defective telomere replication associates with aberrant telomeres characterized by split signals or multiple signals at a telomere [7] (Figure 2A). These aberrant structures are described as fragile telomeres and are found in cells treated with low doses of aphidicolin (a specific inhibitor of DNA polymerases) and in cells deficient in the shelterin proteins and/or other proteins required for telomere replication [7], [29]–[33]. Oxidized bases might impede DNA replication [18]–[20] and perturb telomere-bound TRF1 [21] thereby disrupting telomere replication. Consistent with the hypothesis, the incidence of fragile telomeres is found to be higher in Nth1−/− primary MEFs and bone marrow cells than that in wild-type controls (Figure 2B–2D). Fragile telomeres are also evident in Ogg1−/− mouse bone marrow cells (Figure S3). Lastly, low-dose aphidicolin treatment enhances the numbers of fragile telomeres in wild-type cells, but not significantly in Nth1−/− cells (Table 1), supporting the idea that low doses of aphidicolin and Nth1 deficiency might influence telomere replication and hence fragility via the same mechanism. Collectively, these results suggest that oxidized bases and/or Nth1 deficiency affect telomere replication.

Fig. 2. Fragile telomeres in wild-type and Nth1−/− mouse cells.

(A) Examples of fragile telomeres by telomere-FISH analysis. (B–D) Percentage of fragile telomeres in primary MEFs (4 MEF lineages), freshly isolated bone marrow cells (11 mice), and bone marrow cells that are stimulated in culture (10 mice). At least 60 metaphases/sample are counted. Error bars indicate standard deviation. P-values are calculated using a Student's t-test. Tab. 1. Quantification of fragile telomeres in wild-type and Nth1−/− mouse bone marrow cells and primary MEFs treated with a low dose of aphidicolin.

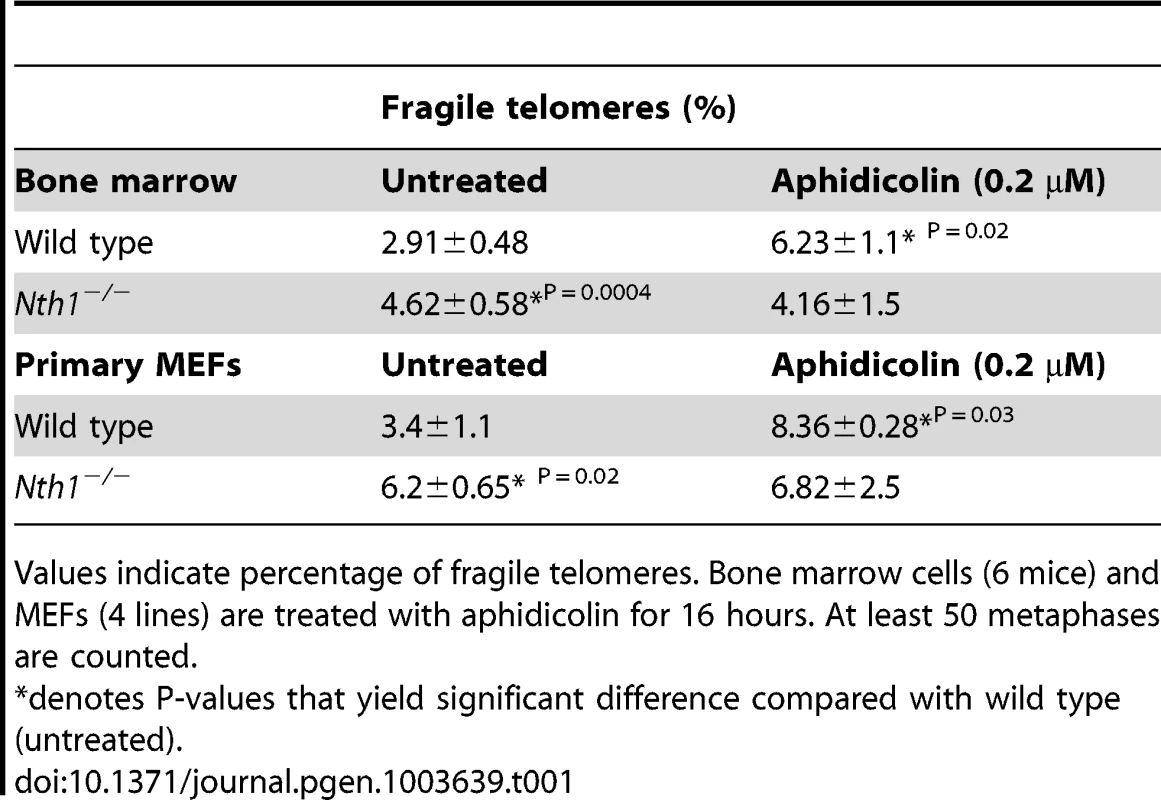

Values indicate percentage of fragile telomeres. Bone marrow cells (6 mice) and MEFs (4 lines) are treated with aphidicolin for 16 hours. At least 50 metaphases are counted. Higher incidence of genomic and telomeric DNA damage foci in Nth1 deficient mouse cells

Persistent oxidative base lesions may cause stalling of DNA replication leading to DNA damage signaling and double strand breaks (DSBs) at telomeres [34]. Oxidative base lesions may also inhibit the binding of telomere binding proteins to telomeric DNA [21] and ultimately their ability to mask telomeres from triggering a DNA damage response [2]. 53BP1 foci formation, a marker for DSBs or DNA damage signal [2], [35], was therefore examined to assess DSBs or a DNA damage response in the genome and telomeres of wild-type and Nth1−/− primary MEFs. The distribution of cells with different numbers of total 53BP1 foci were measured by indirect immunofluorescence (IF), and telomeric 53BP1 foci were then identified by IF-telomere FISH. A greater fraction of Nth1−/− MEFs has 10–25 or >25 53BP1 foci (24% and 10%, respectively) in comparison to wild-type MEFs (10% and 0%, respectively) (Figure 3A). In addition, more Nth1−/− MEFs have ≥3 telomeric 53BP1 foci in comparison to wild-type MEFs (21% and 2%, respectively) (Figure 3B). These results demonstrate that ablation of Nth1 function causes genomic and telomeric damage foci formation. Similar results were obtained in the wild-type and Nth1−/− bone marrow cells that were stimulated in culture (Figure S4).

Fig. 3. DNA damage foci in wild-type and Nth1−/− primary MEFs.

53BP1 foci at genome or telomeres are detected by IF and IF-telomere FISH, respectively. (A) Percentage of wild-type and Nth1−/− cells with various numbers of 53BP1 foci in the genome. (B) Percentage of wild-type and Nth1−/− cells with greater than or equal to three 53BP1 foci that colocalize with telomere DNA. APH: cells treated with 0.2 uM aphidicolin for 16 hours. (C) A representative Nth1−/− cell showing telomeric DNA (red) and 53BP1 foci (green). N = 4 mice, at least 100 cells/sample are counted. Error bars indicate standard deviation. P-values are calculated using a Student's t-test and adjusted using Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate -controlling method. P-values<0.05 are statistically significant using the above method. To further explore the relationship between DNA damage foci formation and DNA replication, wild-type and Nth1−/− primary MEFs were cultured in the presence of a low dose of aphidicolin (0.2 µM). After exposure to aphidicolin for 16 hours, the fraction of wild-type MEFs with >25 53BP1 foci is significantly increased (0% versus 18%; untreated versus treated) (Figure 3A). Aphidicolin treatment also increases the fraction of wild-type cells with ≥3 telomeric 53BP1 foci (2% versus 15%, untreated versus treated) (Figure 3B). Conversely, replication stress only moderately enhances the fraction of Nth1−/− cells with >25 53BP1 foci (24% versus 63%, untreated versus treated) (Figure 3A) and the fraction of Nth1−/− cells with ≥3 telomeric 53BP1 foci (20% versus 27%, untreated versus treated) (Figure 3B). Hence, replication stress significantly enhances telomere DNA damage in wild-type cells, but, to a lesser extent in Nth1−/− cells, supporting our hypothesis that Nth1 deficiency and low doses of aphidicolin may cause similar replication defects, thereby contributing to DNA damage foci formation in the genome and the telomeres.

Persistent DNA damage may trigger phosphorylation of DNA damage checkpoint effector proteins, Chk1 and Chk2 [35]. Because Nth1−/− primary MEFs display an increase in genomic and telomeric 53BP1 foci, we examined Nth1−/− primary MEFs for the presence of phosphorylated forms of Chk1 and Chk2 by Western blot analysis. Despite the presence of DNA damage foci, Chk1 and Chk2 phosphorylation is not detected in Nth1−/− primary MEFs (Figure S5). High-dose aphidicolin (5 µM) and gamma irradiation (10 Gy) induce DSBs and Chk1 and Chk2 phosphorylation in mammalian cells [36], [37], and these treatments cause Chk1 and Chk2 phosphorylation in Nth1−/− primary MEFs (Figure S5). Thus, the DNA damage check point response is intact in Nth1−/− primary MEFs. Collectively, these results suggest that the levels of DNA damage in Nth1−/− mouse cells might not be high enough to evoke a persistent DNA damage response.

Nth1 is involved in telomere length maintenance in mice

As shown above, Nth1 deficiency leads to telomere fragility and telomere DNA damage. These defects may affect telomere length maintenance or distribution. We therefore examined telomere length in wild-type and Nth1−/− mice by telomere-FISH. Flow-FISH analysis reveals that average telomere length does not undergo a significant change in Nth1−/− hematopoietic tissues, i.e. bone marrow and spleen (Figure S6A). Similar results are obtained by Q-FISH analysis of metaphase spreads of freshly isolated wild-type and Nth1−/− bone marrow cells (Figure S6B). It is noteworthy that marginal fluctuation in telomere length (lengthening or shortening) is occasionally observed in Nth1−/− hematopoietic tissues (data not shown).

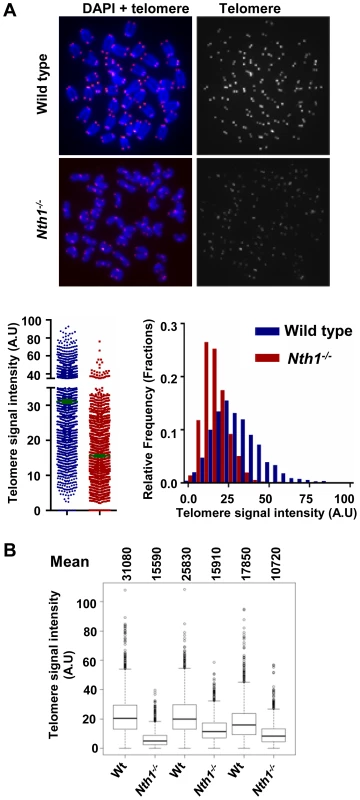

We also investigated if an increase in cell proliferation or oxidative stress could exacerbate telomere defects in Nth1−/− hematopoietic cells. Mouse bone marrow cells were stimulated by interleukin 6 and stem cell factor in culture in the presence of 20% oxygen. Under these conditions, Nth1−/− cells show reduced telomere signal intensity compared to wild-type cells (Figure 4). Thus, replication and/or oxidative stress can induce telomere attrition in the absence of Nth1.

Fig. 4. Telomere length in wild-type and Nth1−/− mouse cells.

Q-FISH analysis of ex vivo stimulated bone marrow cells. (A) Representative metaphase spreads of wild-type and Nth1−/− mouse bone marrow cells showing DAPI staining (blue) and telomere fluorescence signals (red dots in left panel and white dots in right panel). Quantitative measurement of telomere signal intensity is shown in a jitter plot displaying complete distribution of telomeres with diverse signal intensity (left panel) and in a combined histogram displaying relative frequency of telomeres plotted against telomere signal intensity (right panel). Bars (in green) denote mean telomere signal intensity. (B) Box plot of telomere signal intensity of bone marrow cells from three pairs of wild-type and Nth1−/− mice. Mean values are shown above each mouse sample. Telomere signal intensity is depicted in arbitrary units (A.U). Nth1 and telomerase cooperate in telomere maintenance

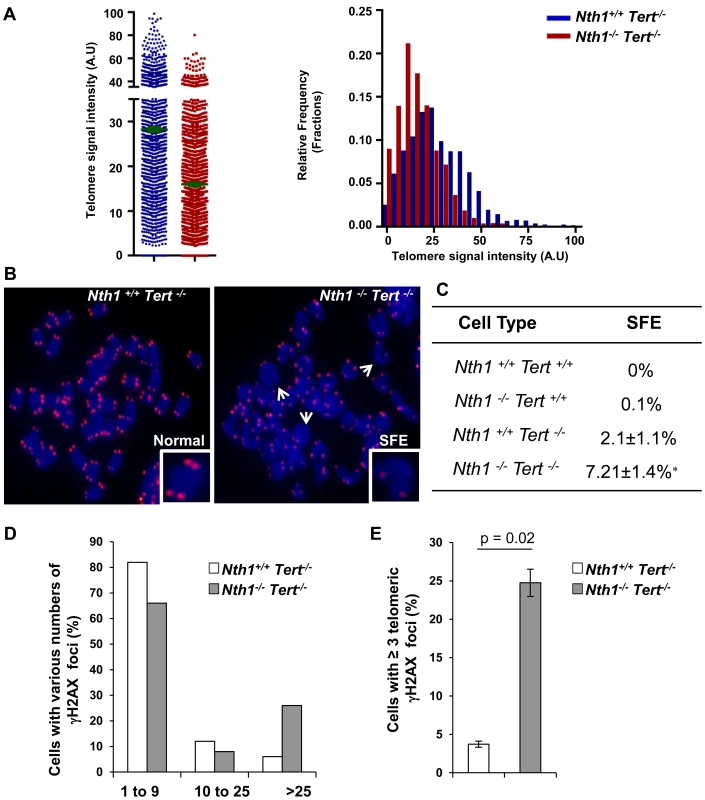

Telomerase is primarily responsible for telomere lengthening in Ogg1 deficient S. cerevisiae [22]. While most human somatic and primary cells express a low or an undetectable level of telomerase [38]–[40], mouse cells from most laboratory strains constitutively express a high level of telomerase [41]. As a consequence, the impact of Nth1 deficiency on telomere integrity could be masked by telomerase in mouse cells. To explore this possibility, Nth1 knockout mice were crossed into a strain lacking the telomerase reverse transcriptase, Tert to generate Nth1+/+Tert−/− and Nth1−/−Tert−/− mice. The bone marrow cells from Nth1+/+Tert−/− and Nth1−/−Tert−/− mice were examined for telomere length and DNA damage foci by Q-FISH and IF-telomere FISH, respectively. Nth1−/−Tert−/− mice have shorter telomere length than Nth1+/+Tert−/− mice (Figure 5A). Both Nth1+/+Tert−/− and Nth1−/−Tert−/− mice have detectable telomere signal free ends (SFEs), but remarkably, SFEs are significantly increased in Nth1−/−Tert−/− mice (7.21±1.4%) in comparison to Nth1+/+Tert−/− mice (2.1±1.1%), a phenotype that is not observed in the telomerase proficient background (Figure 5B and 5C). Furthermore, there are more genomic and telomeric γ-H2AX foci in Nth1−/−Tert−/− mice, compared to Nth1+/+Tert−/− mice (Figure 5D and 5E). These results provide evidence that telomerase deficiency exacerbates telomere defects in Nth1 deficient cells.

Fig. 5. Telomere length and DNA damage foci in Nth1+/+Tert−/− and Nth1−/−Tert−/− mouse cells.

(A) Q-FISH analysis of bone marrow cells derived from Nth1+/+ Tert−/− and Nth1−/−Tert−/− mice (n = 8). Representative quantitative measurement of telomere signal intensity is shown in jitter plot displaying complete distribution of telomeres with diverse signal intensity (left panel) and in a combined histogram displaying relative frequency of telomeres plotted against telomere signal intensity (right panel). Bars (in green) denote mean telomere signal intensity. (B) Representative metaphase spreads from indicated genotypes, showing enlarged chromosome ends with or without telomere signals (Normal and SFE, respectively). Arrows depict SFEs. (C) Quantification of SFEs in bone marrow cells with indicated genotypes (8 mice). At least 50 metaphases/sample are counted. Values depict mean values ± SD from each sample. P-values are calculated using a Student's t-test. * represents P = 0.01. (D–E) Percentage of Nth1+/+ Tert−/− and Nth1−/−Tert−/− cells with various numbers of γ-H2AX foci in the genome and telomeres by IF and IF-telomere FISH analysis, respectively. At least 100 cells/sample are counted. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Critically short telomeres can evoke a DNA damage response and result in cell apoptosis in highly proliferative organs [5], [42], [43]. We therefore examined for the presence of phosphorylated forms of Chk1 and Chk2 in Nth1+/+Tert−/− and Nth1−/−Tert−/− mouse cells by Western blot analysis (Figure S7A). Nth1+/+Tert−/− and Nth1−/−Tert−/− mouse cells display Chk1 and Chk2 phosphorylation (Fig. S7A), indicating that critically short telomeres in these telomerase null mice induce a DNA damage response. Despite the presence of higher number of critically short telomeres, the frequency of apoptosis is not elevated in Nth1−/−Tert−/− bone marrow cells (Figure S7B). Thus, the numbers of critically short telomeres have not reached its critical mass to influence cell viability in Nth1−/−Tert−/− mice. Although the basal level of apoptosis is comparable in Nth1+/+Tert−/− and Nth1−/−Tert−/− cells, a higher percentage of apoptosis is observed in Nth1−/−Tert−/− cells than in Nth1+/+Tert−/− cells after release from replication arrest induced by hydroxyurea (HU), an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase and therefore the synthesis of dNTP (Figure S7B, left panel). However, aphidicolin treatment causes similar increase in apoptosis in Nth1+/+Tert−/− and Nth1−/− Tert−/− cells (Figure S7B, right panel). Interestingly, HU treatment does not affect the rate of apoptotic cells in wild-type and Nth1−/− bone marrow cells in a telomerase proficient background (Figure S7C). Thus, HU, but not aphidicolin may induce apoptosis in Nth1−/−Tert−/− cells, likely by a mechanism involving a cooperative effect of telomerase and Nth1 against oxidative damage.

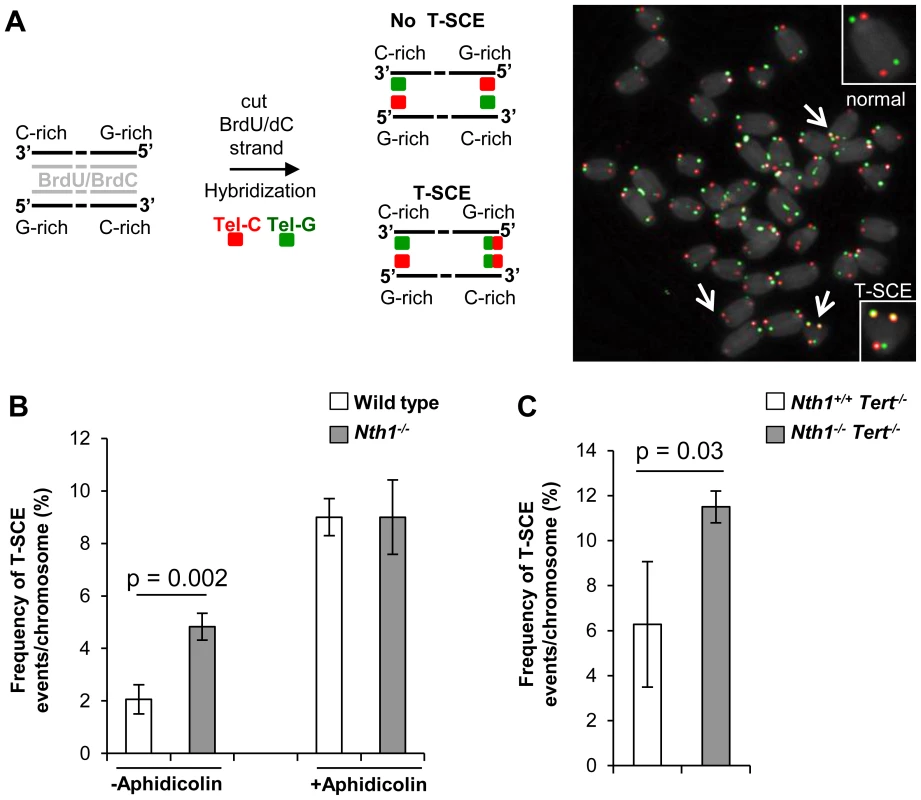

Higher incidence of telomere sister chromatid exchange in Nth1 deficient mouse cells

Telomere sister chromatid exchange via homologous recombination, referred to as T-SCE, may be influenced by defective telomere maintenance or repair [44], [45]. In addition, oxidized bases may impede DNA replication [18]–[20] or interfere with binding of the shelterin proteins to telomeres [21], thereby inducing telomere recombination. We thus measured the frequency of T-SCEs in wild-type and Nth1−/− bone marrow cells by CO-FISH (Figure 6A). Nth1−/− cells display a higher rate of T-SCEs than wild-type cells (4.8 vs. 2.0% T-SCEs/chromosomes, respectively) (Figure 6B, left panel). Furthermore, in the telomerase deficient background a higher rate of T-SCEs is also observed in Nth1−/− mouse bone marrow cells (Figure 6C). Thus, Nth1 deficiency can induce telomere recombination, independently of telomerase. To explore the relationship between telomere recombination and DNA replication, wild-type and Nth1−/− bone marrow cells were treated with a low dose of aphidicolin for 16 hours. T-SCE events are significantly increased in wild-type mouse cells, but to a lesser extent, in Nth1−/− mouse cells (Figure 6B, right panel); supporting that Nth1 deficiency and low doses of aphidicolin may cause similar replication defects, thereby contributing to telomere recombination.

Fig. 6. T-SCEs in wild-type and Nth1−/− mouse cells with or without telomerase.

CO-FISH analysis of ex vivo stimulated bone marrow cells. (A) A schematic presentation of CO-FISH. In brief, newly synthesized strands with BrdU/BrdC are removed, leaving parental strands to be detected by Alexa488-labeled (TTAGGG)3 (in green) and Cy3-labeled telomere (CCCTAA)3 (in red) PNA probes. In an event of T-SCE, an end shows telomere signals in both green and red. An example of T-SCEs in a metaphase of Nth1−/− cell showing DAPI staining (gray), leading strand telomere fluorescence signals (red) and lagging strand telomere fluorescence signals (green). Arrows: T-SCEs. (B) T-SCE events in bone marrow cells of wild-type and Nth1−/− mice (n = 7) with (+) or without (−) aphidicolin treatment at the concentration of 0.2 µM for 16 hours. (C) T-SCE events in bone marrow cells of Nth1+/+Tert−/− and Nth1−/−Tert−/− mice (n = 4). At least 90 metaphases/sample are counted. Error bars indicate standard deviation. P-values are calculated using a Student's t-test. Discussion

The BER pathway repairs non-bulky oxidative DNA lesions, including a number of potential replication-blocking lesions that hamper genome stability and cell viability, if left unrepaired. Telomeres are also critical for genomic integrity, because unprotected chromosome ends are highly prone to recombination and induce a DNA damage response. Telomeric DNA is sensitive to oxidative DNA damage [8], [9], [12], which may have negative impact on telomere maintenance. Here, we show that ablation of a BER repair protein, Nth1 leads to accumulation of telomere base damage and an increase in telomere attrition, fragility, recombination, and DNA damage foci. Telomerase deficiency exacerbates the telomere defects of Nth1 deficient mice.

It has been shown that there is a tissue and age-dependent accumulation of 2,6.-diamino-4-hydroxy-5-formamidopyrimidine and 4, 6.-diamino-5-formamidopyrimidine in Nth1−/− mouse genome by gas and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry detection methods [24], [46]. However, other Nth1-preferred base substrates, e.g. 5-OH-Cyt, 5-OH-Ura, and Tg do not persist in Nth1−/− mouse genome or are below the detection by the above methods [46]. In this study, we have utilized a quantitative PCR method to detect Endonuclease III (or Nth1)-sensitive DNA lesions at telomeric and non-telomeric loci in mice. A higher number of Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions are detected at the telomeres, but not at the 36B4 locus in Nth1 deficient kidney and MEFs, supporting that these oxidative base lesions preferentially accumulate at telomeres in the absence of Nth1. Since the extracts from Nth1−/− mice are unable to incise oxidized bases in 5-OH-Cyt, 5-OH-Ura, or Tg-containing oligonucleotides [47], it implies that there is a defective repair of these DNA base lesions in Nth1 deficient mice, which could be exacerbated at telomeres. Nth1−/− MEFs are also inefficient in repairing telomeric Endonuclease III-sensitive DNA lesions that are induced by an oxidant, benzo[a]pyrene (Figure 1B). Our results support that Nth1 plays an important role in the removal of certain oxidative base lesions at telomeres. Similarly, Ogg1−/− mouse cells show elevated levels of Fpg-sensitive lesions and defective base repair at telomeres [26]. These results confirm the importance of BER proteins in protecting telomere DNA from oxidative damage.

Besides base lesions, 53BP1 and γ-H2AX foci are also detected in the telomeres of Nth1−/− mice. It is likely that these telomeric damage foci are derived from stalled replication forks. For example, the DNA polymerase inhibitor, aphidicolin, at low doses causes 7.5-fold increase in the percentage of wild-type cells positive for telomeric damage foci. Nth1−/− cells accumulate oxidized base lesions, which may also impede DNA polymerases, causing replication stress. The fact that low-dose aphidicolin treatment only causes 1.2-fold increase in the percentage of Nth1−/− cells positive for telomeric damage foci indicates that oxidative base lesions may interfere with telomere replication via a mechanism similar to that of low doses of aphidicolin. This trend is also observed for telomere fragility, telomere recombination and apoptosis in Nth1−/− cells that are treated with low doses of aphidicolin. We speculate that low doses of aphidicolin and Nth1 deficiency might influence these phenotypes by acting in the same pathway, such as inhibiting DNA polymerases. However, there is no detectable Chk1 activation in Nth1 null cells, except with high-dose aphidicolin treatment. The differential response of Nth1−/− cells for telomere fragility and Chk1 activation could be due to different mechanisms and/or different doses (low or high) of aphidicolin in triggering these phenotypes. Sufficient DNA damage could trigger Chk1 activation [37], but the exact mechanism for the occurrence of fragile telomeres is yet unknown. Although Nth1 deficiency might sufficiently perturb DNA polymerases, to result in an increase in fragile telomeres, it may not lead to enough DNA damage to activate Chk1. Instead, high-dose aphidicolin treatment can significantly increase DNA damage [36], [37] and thus activate Chk1 in Nth1 deficient cells.

Although oxidative base lesions may interfere with telomere replication, Nth1 could directly interact with and be involved in the progression of the replication apparatus [48], [49]. SSBs, which usually accumulate in telomeric DNA in the vicinity of oxidative base lesions [8], [13]–[15], could also be converted to DSBs during DNA replication [34] to interfere with telomere replication. Nevertheless, these potential defects fail to activate a persistent DNA damage response in Nth1−/− mice, as Chk1 and Chk2 are not phosphorylated in the null mice. This is consistent with the fact that deletion of Nth1 alone does not lead to critically short telomeres and cell apoptosis.

When Nth1 null mice are bred with Tert null mice, Nth1−/−Tert−/− mice harbor more critically short telomeres in comparison to Nth1+/+Tert−/− mice. Thus, Nth1 cooperates with telomerase to maintain telomere length. Interestingly, HU does not affect the rate of apoptosis in Nth1−/− mouse cells in a telomerase proficient background, but it promotes apoptosis in Nth1−/− mouse cells in a telomerase deficient background (Figure S7B). These results imply that HU induces apoptosis by a mechanism involving a cooperative effect of telomerase and Nth1 against oxidative damage. Nth1+/+Tert−/− and Nth1−/−Tert−/− mice are currently being propagated for additional generations to further exhaust telomere reserves, which may help reveal the impact of defective oxidative base lesion repair on telomere function and cell viability in mouse aging.

Nth1 deficient mouse cells have a higher incidence of fragile telomeres, implying that replication encounters problems at telomeric DNA. We speculate that some Endonuclease III-sensitive base lesions, e.g. Tg pose a problem to the replication machinery in Nth1 deficient mice. However, fragile telomeres are also increased in Ogg1−/− mice that harbor 8-oxoG. Thus, the presence of oxidative base lesions may nevertheless affect telomere replication, independently of the nature of the lesions. Oxidative base lesions may also impair telomere replication via perturbing the binding of TRF1 to telomeres [21], which is required for telomere replication [7]. The replication inhibitor aphidicolin does not increase the frequency of fragile telomeres in Nth1 deficient mice. Similarly, aphidicolin fails to enhance fragile telomeres in mutant mice deficient in genes facilitating telomere replication, e.g. ATR or CTC1 [29], [31], [32]. These results further support our hypothesis that telomere replication is defective in Nth1 deficient mice.

Ex vivo-stimulated Nth1 deficient bone marrow cells display increased T-SCE events, which possibly reflects replication problem and DNA damage in telomeric DNA in Nth1 null cells [45]. In line with this, low-dose aphidicolin treatment increases T-SCE events in wild-type, but not in Nth1 deficient mouse cells (Figure 6B), supporting that low doses of aphidicolin or oxidative base lesion–induced replication stress contributes to telomere recombination. Alternatively, a DNA glycosylase may inhibit telomere recombination [50] and ablation of DNA glycosylase function would therefore relieve this inhibition and activate the recombination pathway. Lastly, Endonuclease III-sensitive base lesions may affect telomere recombination by disrupting the association of shelterin to telomeres [21].

Telomere length regulation involves many factors including telomerase, telomere binding proteins and telomere recombination/replication/capping. As discussed above, persistent oxidative DNA lesions and/or insufficient BER capacity could disrupt these processes, thereby interfering with telomere length homeostasis. Although Nth1 deficient hematopoietic tissues have a normal distribution of telomere length, they undergo telomere shortening after being stimulated in culture with 20% oxygen. This suggests that the impact of Nth1 deficiency on telomere length is dependent on cell proliferation and/or exposure to higher oxygen levels. Cultured Nth1 deficient bone marrow cells harbor more DNA damage that may also contribute to telomere attrition in these cells. Furthermore, damaged bases or Nth1 deficiency might interfere with telomere replication and thus telomere length, especially upon stimulating cell proliferation.

The Nth1 deficient mouse model is a valuable tool for assessing the role of BER in telomere maintenance. However, somatic cells from Nth1 deficient mice differ from human somatic cells in that the mouse cells express abundant telomerase activity. In this regard, it is important to note that the impact of Nth1 deficiency on telomere length is more severe in cells carrying the Tert null alleles. Moreover, Nth1 and Tert double null mouse bone marrow cells demonstrate an elevated rate of apoptosis after replication stress. Thus, Nth1 and Tert might cooperate in maintaining telomere function in replicating cells. Because most human somatic cells express a low level of telomerase, age-dependent changes in BER capacity [51] could have a significant impact on telomere maintenance and cell viability in human tissues.

Materials and Methods

Mice and primary mouse cells

The generation of Nth1 null (Nth1−/−) and Tert null (Tert−/−) mice was described previously [52], [53]. Nth1−/− mice were further backcrossed into C57BL/6 background. Wild-type and Nth1−/− mice were derived from heterozygous (Nth1+/−) breeders. To generate mice deficient for both Nth1 and Tert, Nth1−/− mice was bred with Tert−/− mice to obtain Nth1+/−Tert+/−, which were subsequently bred to generate Nth1+/+Tert−/− and Nth1−/− Tert−/− mice. Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from 13.5 day embryos of Nth1+/− female bred with Nth1+/− male and cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum in CO2 incubator in the presence of 20% oxygen. Bone marrow cells were flushed from femurs and tibias and cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum with interleukin 6 (200 U/mL; Peprotech) and stem cell factor (100 ng/mL; Peprotech). Single cell suspensions of spleen were obtained by passing the spleen suspension through a cell strainer (70 µm, BD Falcon). All animal experiments were carried out according to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (National Academy Press, USA, 1996), and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National Institute on Aging.

Detection of oxidative base lesions in telomeres

Identification of oxidative base lesions in telomeres was performed as previously described [27]. In brief, DNA was isolated from mouse kidney and primary MEFs by salting out [22], [26]. To excise oxidative base lesions and generate strand breaks at the resulting abasic sites, DNA was digested with Endonuclease III. 400 ng of duplex oligomer or genomic DNA were incubated overnight with 12 units of Endonuclease III (New England Biolabs) in 1× NEB Endonuclease III buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Dithiothreitol, pH 8.0). A duplicate digestion was also set up for each corresponding sample in mock digestion buffer (i.e. enzyme was excluded and substituted with H2O). All samples were set up on ice, then incubated at 37°C overnight to allow complete digestion and followed by the quantitative Real-Time amplification (qPCR) [54]. Five oligonucleotides containing TTAGGG repeats with 0, 1, 2, 4 or 8 thymine glycols were used for generation of a standard curve (Table S1). A reverse oligonucleotide was used to construct duplex substrates (GeneWorks, Adelaide). Forward and reverse oligonucleotides were mixed in a 1∶1 molar ratio. Annealing reactions were incubated at 95°C for 10 min and then cooled to room temperature for 30 min. For qPCR, each 20 µL reaction was composed as follows: 40 pg of digested or undigested oligonucleotides or 40 ng of digested or undigested genomic DNA, 1× SYBR Green master mix, 100 nM telo1 forward and 100 nM telo2 reverse primers [54]. All samples were run on an ABI 7300 Sequence Detection System with the SDS Ver. 1.9 software (Applied Biosystems). Cycling conditions were: 10 minutes at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for one minute. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. PCR efficiencies and correlation coefficients for genomic DNA and synthetic oligonucleotides are shown in Table S2. The Ct values for all the samples were obtained from PCR reactions run under the same conditions using the same reagents, and the ΔCT value (Ct treated - Ct mock) for each sample were converted into numbers of Endonuclease III-sensitive lesions by comparison to the standard curve, as described previously [27].

Telomere quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization

Flow-FISH: The average telomere fluorescence in populations of splenocytes and bone marrow cells was measured according to a previously published protocol [55]. In each set, data were pooled from at least five individual mice. A telomere-specific FITC conjugated (CCCTAA)3 PNA probe (0.3 µg/mL, Panagene) was employed and telomere fluorescent signal intensity was measured by Accuri O6 flow cytometer using FlowJo software.

Q-FISH: Mice were injected with 100 µl of 0.5% colchicine intraperitoneally for approximately 30 minutes before being sacrificed. Bone marrow cells were then collected by flushing 1 ml of PBS from femurs. Cultured bone marrow cells and primary MEFs were incubated with 0.1 µg/mL colcemid for 2–6 hours at 37°C to allow mitotic cells to accumulate. Metaphase spreads were obtained by incubating mouse cells in 0.075 M KCl for 15 minutes at 37°C, followed by fixing cells in ice-cold (3∶1) methanol and glacial acetic acid and dropping the fixed cells onto slides. Metaphase spreads were hybridized with Cy3-labeled (CCCTAA)3 (0.3 µg/mL, Panagene), washed, and then counterstained with 4, 6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) as previously described [56]. Images were captured using Cytovision software (Applied Imaging Corp.) on a fluorescence microscope (Axio2; Carl Zeiss, Germany); followed by quantification of individual telomere fluorescence signals using the TFL-Telo software (a kind gift from P. Lansdorp, Vancouver, BC). For histograms and box/jitter plots, data from different mice of each genotype were scored using R statistical package (http://www.r-project.org/) and Graphpad software. Metaphases from different mice of each genotype were scored for fragile telomeres (a chromatid with ≥2 telomere signals) and SFEs (chromosome ends without detectable telomere signals).

Chromosome-Orientation FISH (CO-FISH)

CO-FISH was used to measure T-SCEs as described previously [44]. Briefly, bone marrow cells were cultured in medium with 3∶1 ratio of BrdU/BrdC at a final concentration of 1×10−5 M for approximately 12 hours. Colcemid (0.1 µg/ml) was added for the final 2 hours. Metaphase spreads were prepared as described above, stained with Hoechst 33258, exposed to UV light and then digested with exonuclease III to remove newly synthesized strands. Remaining parental strands were hybridized with Cy3-labeled (CCCTAA)3 probe, then briefly washed with hybridization buffer and subsequently with Alexa 488–labeled (TTAGGG)3 probes. Hybridization and wash conditions were identical to those described for telomeric FISH. A chromosome with more than two telomeric DNA signals by both probes was scored as T-SCE positive.

IF and telomere FISH

Fibroblasts were grown overnight on chamber slides and bone marrow cells were spun onto Cytospin microscopic slides at 200 rpm for 3 minutes. Cells were washed in PBS, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, permeabilized with 0.5% tritonX-100 for 5 minutes on ice and blocked with 10% FBS for 1–2 hours. Cells were stained overnight at 4°C with a rabbit anti-γH2AX antibody (1∶200, Santa cruz) or a rabbit anti-53BP1 antibody (1∶500, Novus Biologicals), followed by Alexa 488-labeled secondary antibody (1∶500; Molecular Probes) for one hour at room temperature. Cells were washed in PBS, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, washed, dehydrated through ethanol series and briefly dried. Slides were immediately hybridized to Cy3-labeled (CCCTAA)3 probe (Panagene) for 2 hours at room temperature. Hybridization buffer and wash conditions were identical to those described for telomeric FISH. Slides were counterstained with DAPI. Z-stack images were captured on a fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 200M; Carl Zeiss).

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was quantified using the Annexin V: FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit as per the manufacturer's instructions (BD Pharmingen). Briefly, cells were harvested, washed twice with ice-cold PBS and resuspended in 1× Binding buffer supplied by the manufacturer. Cells were incubated with 5 µL PI and 5 µL FITC-Annexin V at room temperature for 15 minutes and analyzed using an Accuri O6 flow cytometer with FlowJo software.

Western blot

Cells were exposed to 5 µM aphidicolin for 8 hours or 2 mM HU for 24 hours as a positive control for Chk1 phosphorylation or 10 Gy Ionizing radiation with 1 hour recovery as a positive control for Chk2 phosphorylation [37]. Cells were lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5 M EDTA, 20% SDS) supplemented with complete, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablet and PhosSTOP Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail Tablet (Roche). Approximately 40–100 µg cell extracts were examined for phosphorylated-Chk1 or Chk2 and actin by rabbit phospho-Chk1 (S345) (1 : 1000, Cell signaling, 2341), mouse Anti-Chk2 (1∶500, BD Biosciences, 611570) or actin (1∶1000, Santa Cruz, SC-1616) antibodies.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. de LangeT (2005) Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev 19 : 2100–2110.

2. d'Adda di FagagnaF, TeoSH, JacksonSP (2004) Functional links between telomeres and proteins of the DNA-damage response. Genes Dev 18 : 1781–1799.

3. BlackburnEH (2001) Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell 106 : 661–673.

4. von ZglinickiT (2000) Role of oxidative stress in telomere length regulation and replicative senescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 908 : 99–110.

5. Liu Y, Harrington L (2012) Murine models of dysfunctional telomeres and telomerase; Lue N, Autexier C, editors. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 213–242 p.

6. CasperAM, NghiemP, ArltMF, GloverTW (2002) ATR regulates fragile site stability. Cell 111 : 779–789.

7. SfeirA, KosiyatrakulST, HockemeyerD, MacRaeSL, KarlsederJ, et al. (2009) Mammalian telomeres resemble fragile sites and require TRF1 for efficient replication. Cell 138 : 90–103.

8. PetersenS, SaretzkiG, von ZglinickiT (1998) Preferential accumulation of single-stranded regions in telomeres of human fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res 239 : 152–160.

9. RheeDB, GhoshA, LuJ, BohrVA, LiuY (2010) Factors that influence telomeric oxidative base damage and repair by DNA glycosylase OGG1. DNA Repair (Amst) 10 : 34–44.

10. RochettePJ, BrashDE (2010) Human telomeres are hypersensitive to UV-induced DNA Damage and refractory to repair. PLoS Genet 6: e1000926.

11. FumagalliM, RossielloF, ClericiM, BarozziS, CittaroD, et al. (2012) Telomeric DNA damage is irreparable and causes persistent DNA-damage-response activation. Nat Cell Biol 14 : 355–365.

12. HewittG, JurkD, MarquesFD, Correia-MeloC, HardyT, et al. (2012) Telomeres are favoured targets of a persistent DNA damage response in ageing and stress-induced senescence. Nat Commun 3 : 708–717.

13. HenleES, HanZ, TangN, RaiP, LuoY, et al. (1999) Sequence-specific DNA cleavage by Fe2+-mediated fenton reactions has possible biological implications. J Biol Chem 274 : 962–971.

14. OikawaS, KawanishiS (1999) Site-specific DNA damage at GGG sequence by oxidative stress may accelerate telomere shortening. FEBS Lett 453 : 365–368.

15. OikawaS, Tada-OikawaS, KawanishiS (2001) Site-specific DNA damage at the GGG sequence by UVA involves acceleration of telomere shortening. Biochemistry 40 : 4763–4768.

16. DavidSS, O'SheaVL, KunduS (2007) Base-excision repair of oxidative DNA damage. Nature 447 : 941–950.

17. SvilarD, GoellnerEM, AlmeidaKH, SobolRW (2011) Base excision repair and lesion-dependent subpathways for repair of oxidative DNA damage. Antioxid Redox Signal 14 : 2491–2507.

18. ClarkJM, BeardsleyGP (1986) Thymlne glycol lesions terminate chain elongation by DNA polymerase I in vitro. Nucleic Acids Research 14 : 737–749.

19. EvansJ, MaccabeeM, HatahetZ, CourcelleJ, BockrathR, et al. (1993) Thymine ring saturation and fragmentation products: lesion bypass, misinsertion and implications for mutagenesis. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology 299 : 147–156.

20. AllerP, RouldMA, HoggM, WallaceSS, DoublieS (2007) A structural rationale for stalling of a replicative DNA polymerase at the most common oxidative thymine lesion, thymine glycol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 814–818.

21. OpreskoPL, FanJ, DanzyS, WilsonDM3rd, BohrVA (2005) Oxidative damage in telomeric DNA disrupts recognition by TRF1 and TRF2. Nucleic Acids Res 33 : 1230–1239.

22. LuJ, LiuY (2010) Deletion of Ogg1 DNA glycosylase results in telomere base damage and length alteration in yeast. Embo J 29 : 398–409.

23. HegdeML, HazraTK, MitraS (2008) Early steps in the DNA base excision/single-strand interruption repair pathway in mammalian cells. Cell Res 18 : 27–47.

24. HuJ, de Souza-PintoNC, HaraguchiK, HogueBA, JarugaP, et al. (2005) Repair of Formamidopyrimidines in DNA Involves Different Glycosylases. Journal of Biological Chemistry 280 : 40544–40551.

25. LunaL, BjøråsM, HoffE, RognesT, SeebergE (2000) Cell-cycle regulation, intracellular sorting and induced overexpression of the human NTH1 DNA glycosylase involved in removal of formamidopyrimidine residues from DNA. Mutation Research/DNA Repair 460 : 95–104.

26. WangZ, RheeDB, LuJ, BohrCT, ZhouF, et al. (2010) Characterization of oxidative guanine damage and repair in mammalian telomeres. PLoS Genet 6: e1000951.

27. O'CallaghanN, BaackN, SharifR, FenechM (2012) A qPCR-based assay to quantify oxidized guanine and other FPG-sensitive base lesions within telomeric DNA. Biotechniques 51 : 403–411.

28. LeadonSA, StampferMR, BartleyJ (1988) Production of oxidative DNA damage during the metabolic activation of benzo[a]pyrene in human mammary epithelial cells correlates with cell killing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 85 : 4365–4368.

29. MartinezP, ThanasoulaM, MunozP, LiaoC, TejeraA, et al. (2009) Increased telomere fragility and fusions resulting from TRF1 deficiency lead to degenerative pathologies and increased cancer in mice. Genes Dev 23 : 2060–2075.

30. BadieS, EscandellJM, BouwmanP, CarlosAR, ThanasoulaM, et al. (2010) BRCA2 acts as a RAD51 loader to facilitate telomere replication and capping. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17 : 1461–1469.

31. McNeesCJ, TejeraAM, MartinezP, MurgaM, MuleroF, et al. (2010) ATR suppresses telomere fragility and recombination but is dispensable for elongation of short telomeres by telomerase. J Cell Biol 188 : 639–652.

32. GuP, MinJN, WangY, HuangC, PengT, et al. (2012) CTC1 deletion results in defective telomere replication, leading to catastrophic telomere loss and stem cell exhaustion. Embo J 31 : 2309–2321.

33. RemeseiroS, CuadradoA, CarreteroM, MartinezP, DrosopoulosWC, et al. (2012) Cohesin-SA1 deficiency drives aneuploidy and tumourigenesis in mice due to impaired replication of telomeres. EMBO J 31 : 2076–2089.

34. SedelnikovaOA, RedonCE, DickeyJS, NakamuraAJ, GeorgakilasAG, et al. (2010) Role of oxidatively induced DNA lesions in human pathogenesis. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research 704 : 152–159.

35. CicciaA, ElledgeSJ (2010) The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell 40 : 179–204.

36. GloverTW, BergerC, CoyleJ, EchoB (1984) DNA polymerase alpha inhibition by aphidicolin induces gaps and breaks at common fragile sites in human chromosomes. Hum Genet 67 : 136–142.

37. BrownEJ, BaltimoreD (2003) Essential and dispensable roles of ATR in cell cycle arrest and genome maintenance. Genes Dev 17 : 615–628.

38. HarleyCB, FutcherAB, GreiderCW (1990) Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 345 : 458–460.

39. HastieND, DempsterM, DunlopMG, ThompsonAM, GreenDK, et al. (1990) Telomere reduction in human colorectal carcinoma and with ageing. Nature 346 : 866–868.

40. WrightWE, PiatyszekMA, RaineyWE, ByrdW, ShayJW (1996) Telomerase activity in human germline and embryonic tissues and cells. Dev Genet 18 : 173–179.

41. ProwseKR, GreiderCW (1995) Developmental and tissue-specific regulation of mouse telomerase and telomere length. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92 : 4818–4822.

42. HemannMT, StrongMA, HaoLY, GreiderCW (2001) The shortest telomere, not average telomere length, is critical for cell viability and chromosome stability. Cell 107 : 67–77.

43. LeeHW, BlascoMA, GottliebGJ, HornerJW2nd, GreiderCW, et al. (1998) Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs. Nature 392 : 569–574.

44. BaileySM, GoodwinEH, CornforthMN (2004) Strand-specific fluorescence in situ hybridization: the CO-FISH family. Cytogenet Genome Res 107 : 14–17.

45. HagelstromRT, BlagoevKB, NiedernhoferLJ, GoodwinEH, BaileySM (2010) Hyper telomere recombination accelerates replicative senescence and may promote premature aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 : 15768–15773.

46. ChanMK, Ocampo-HafallaMT, VartanianV, JarugaP, KirkaliG, et al. (2009) Targeted deletion of the genes encoding NTH1 and NEIL1 DNA N-glycosylases reveals the existence of novel carcinogenic oxidative damage to DNA. DNA Repair 8 : 786–794.

47. KarahalilB, de Souza-PintoNC, ParsonsJL, ElderRH, BohrVA (2003) Compromised incision of oxidized pyrimidines in liver mitochondria of mice deficient in NTH1 and OGG1 glycosylases. J Biol Chem 278 : 33701–33707.

48. OtterleiM, WarbrickE, NagelhusTA, HaugT, SlupphaugG, et al. (1999) Post-replicative base excision repair in replication foci. Embo J 18 : 3834–3844.

49. OyamaM, WakasugiM, HamaT, HashidumeH, IwakamiY, et al. (2004) Human NTH1 physically interacts with p53 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 321 : 183–191.

50. de Souza-PintoNC, MaynardS, HashiguchiK, HuJ, MuftuogluM, et al. (2009) The recombination protein RAD52 cooperates with the excision repair protein OGG1 for the repair of oxidative lesions in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol 29 : 4441–4454.

51. MaynardS, SchurmanSH, HarboeC, de Souza-PintoNC, BohrVA (2009) Base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage and association with cancer and aging. Carcinogenesis 30 : 2–10.

52. LiuY, SnowBE, HandeMP, YeungD, ErdmannNJ, et al. (2000) The telomerase reverse transcriptase is limiting and necessary for telomerase function in vivo. Curr Biol 10 : 1459–1462.

53. ElderRH, DianovGL (2002) Repair of dihydrouracil supported by base excision repair in mNTH1 knock-out cell extracts. J Biol Chem 277 : 50487–50490.

54. O'CallaghanN, DhillonV, ThomasP, FenechM (2008) A quantitative real-time PCR method for absolute telomere length. Biotechniques 44 : 807–809.

55. RuferN, DragowskaW, ThornburyG, RoosnekE, LansdorpPM (1998) Telomere length dynamics in human lymphocyte subpopulations measured by flow cytometry. Nat Biotechnol 16 : 743–747.

56. ZijlmansJM, MartensUM, PoonSS, RaapAK, TankeHJ, et al. (1997) Telomeres in the mouse have large inter-chromosomal variations in the number of T2AG3 repeats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94 : 7423–7428.

57. BenjaminiY, HochbergY (1995) Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Statist Soc B 57 : 289–300.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Independent Evolution of Transcriptional Inactivation on Sex Chromosomes in Birds and MammalsČlánek The bHLH Subgroup IIId Factors Negatively Regulate Jasmonate-Mediated Plant Defense and DevelopmentČlánek Selective Pressures to Maintain Attachment Site Specificity of Integrative and Conjugative ElementsČlánek Reassembly of Nucleosomes at the Promoter Initiates Resilencing Following Decitabine ExposureČlánek Hepatocyte Growth Factor Signaling in Intrapancreatic Ductal Cells Drives Pancreatic Morphogenesis

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2013 Číslo 7- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- An Solution for Crossover Formation

- Genome-Wide Association Mapping in Dogs Enables Identification of the Homeobox Gene, , as a Genetic Component of Neural Tube Defects in Humans

- Independent Evolution of Transcriptional Inactivation on Sex Chromosomes in Birds and Mammals

- Stepwise Activation of the ATR Signaling Pathway upon Increasing Replication Stress Impacts Fragile Site Integrity

- Genomic Analysis of Natural Selection and Phenotypic Variation in High-Altitude Mongolians

- Modification of tRNA by Elongator Is Essential for Efficient Translation of Stress mRNAs

- Role of CTCF Protein in Regulating Locus Transcription

- Gene Set Signature of Reversal Reaction Type I in Leprosy Patients

- Mapping of PARK2 and PACRG Overlapping Regulatory Region Reveals LD Structure and Functional Variants in Association with Leprosy in Unrelated Indian Population Groups

- Is Required for Formation of the Genital Ridge in Mice

- Monopolin Subunit Csm1 Associates with MIND Complex to Establish Monopolar Attachment of Sister Kinetochores at Meiosis I

- Recombination Dynamics of a Human Y-Chromosomal Palindrome: Rapid GC-Biased Gene Conversion, Multi-kilobase Conversion Tracts, and Rare Inversions

- Mechanisms of Protein Sequence Divergence and Incompatibility

- Histone Methyltransferase DOT1L Drives Recovery of Gene Expression after a Genotoxic Attack

- Female Behaviour Drives Expression and Evolution of Gustatory Receptors in Butterflies

- Combinatorial Regulation of Meiotic Holliday Junction Resolution in by HIM-6 (BLM) Helicase, SLX-4, and the SLX-1, MUS-81 and XPF-1 Nucleases

- The bHLH Subgroup IIId Factors Negatively Regulate Jasmonate-Mediated Plant Defense and Development

- The Role of Interruptions in polyQ in the Pathology of SCA1

- Dietary Restriction Induced Longevity Is Mediated by Nuclear Receptor NHR-62 in

- Fine Time Course Expression Analysis Identifies Cascades of Activation and Repression and Maps a Putative Regulator of Mammalian Sex Determination

- Genome-scale Co-evolutionary Inference Identifies Functions and Clients of Bacterial Hsp90

- Oxidative Stress and Replication-Independent DNA Breakage Induced by Arsenic in

- A Moonlighting Enzyme Links Cell Size with Central Metabolism

- Budding Yeast Greatwall and Endosulfines Control Activity and Spatial Regulation of PP2A for Timely Mitotic Progression

- The Conserved Intronic Cleavage and Polyadenylation Site of CstF-77 Gene Imparts Control of 3′ End Processing Activity through Feedback Autoregulation and by U1 snRNP

- The BTB-zinc Finger Transcription Factor Abrupt Acts as an Epithelial Oncogene in through Maintaining a Progenitor-like Cell State

- The Cohesion Protein SOLO Associates with SMC1 and Is Required for Synapsis, Recombination, Homolog Bias and Cohesion and Pairing of Centromeres in Drosophila Meiosis

- The RNA-binding Proteins FMR1, Rasputin and Caprin Act Together with the UBA Protein Lingerer to Restrict Tissue Growth in

- Pattern Dynamics in Adaxial-Abaxial Specific Gene Expression Are Modulated by a Plastid Retrograde Signal during Leaf Development

- A Network of HMG-box Transcription Factors Regulates Sexual Cycle in the Fungus

- Bacterial Adaptation through Loss of Function

- ENU-induced Mutation in the DNA-binding Domain of KLF3 Reveals Important Roles for KLF3 in Cardiovascular Development and Function in Mice

- Interplay between Structure-Specific Endonucleases for Crossover Control during Meiosis

- FGF Signalling Regulates Chromatin Organisation during Neural Differentiation via Mechanisms that Can Be Uncoupled from Transcription

- The Arabidopsis RNA Binding Protein with K Homology Motifs, SHINY1, Interacts with the C-terminal Domain Phosphatase-like 1 (CPL1) to Repress Stress-Inducible Gene Expression

- Selective Pressures to Maintain Attachment Site Specificity of Integrative and Conjugative Elements

- The Conserved ADAMTS-like Protein Lonely heart Mediates Matrix Formation and Cardiac Tissue Integrity

- The cGMP-Dependent Protein Kinase EGL-4 Regulates Nociceptive Behavioral Sensitivity

- RBM5 Is a Male Germ Cell Splicing Factor and Is Required for Spermatid Differentiation and Male Fertility

- Disease-Related Growth Factor and Embryonic Signaling Pathways Modulate an Enhancer of Expression at the 6q23.2 Coronary Heart Disease Locus

- Yeast Pol4 Promotes Tel1-Regulated Chromosomal Translocations

- A Dual Role for SOX10 in the Maintenance of the Postnatal Melanocyte Lineage and the Differentiation of Melanocyte Stem Cell Progenitors

- SLC26A4 Targeted to the Endolymphatic Sac Rescues Hearing and Balance in Mutant Mice

- Odoriferous Defensive Stink Gland Transcriptome to Identify Novel Genes Necessary for Quinone Synthesis in the Red Flour Beetle,

- Prediction of Complex Human Traits Using the Genomic Best Linear Unbiased Predictor

- Gene × Physical Activity Interactions in Obesity: Combined Analysis of 111,421 Individuals of European Ancestry

- Reassembly of Nucleosomes at the Promoter Initiates Resilencing Following Decitabine Exposure

- Exquisite Light Sensitivity of Cryptochrome

- miR-133a Regulates Adipocyte Browning In Vivo

- Strabismus Promotes Recruitment and Degradation of Farnesylated Prickle in Planar Polarity Specification

- Hepatocyte Growth Factor Signaling in Intrapancreatic Ductal Cells Drives Pancreatic Morphogenesis

- Is a Potential Tumor Suppressor Gene Commonly Inactivated by Epigenetic Mechanisms in Colorectal Cancer

- Joint Molecule Resolution Requires the Redundant Activities of MUS-81 and XPF-1 during Meiosis

- The Mating Competence of Geographically Diverse Strains in Their Natural and Unnatural Sand Fly Vectors

- Defective Repair of Oxidative Base Lesions by the DNA Glycosylase Nth1 Associates with Multiple Telomere Defects

- Effective Blocking of the Enhancer Requires Cooperation between Two Main Mechanisms Suggested for the Insulator Function

- Trans-Ancestral Studies Fine Map the SLE-Susceptibility Locus

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- SLC26A4 Targeted to the Endolymphatic Sac Rescues Hearing and Balance in Mutant Mice

- Bacterial Adaptation through Loss of Function

- The Cohesion Protein SOLO Associates with SMC1 and Is Required for Synapsis, Recombination, Homolog Bias and Cohesion and Pairing of Centromeres in Drosophila Meiosis

- Gene × Physical Activity Interactions in Obesity: Combined Analysis of 111,421 Individuals of European Ancestry

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy