-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

A Conserved DNA Repeat Promotes Selection of a Diverse Repertoire of Surface Antigens from the Genomic Archive

Chromosomal translocations can fuel genetic change or cause catastrophic genomic damage. African trypanosomes, exemplified by Trypanosoma brucei sub-species, are unicellular parasites that can chronically infect their human and livestock hosts by using a strategy of antigenic variation by which they repeatedly change their protein coats. Switching the surface coat requires the accurate selection and translocation of a single silent coat gene, from a large genomic archive, into an actively transcribed site. How the coat genes from within this deep archive are selected and activated was unproven. Here we show that a specific repetitive DNA sequence is required to access coat genes from diverse sites within the genome. The likely outcome of restricting this process of coat gene selection in natural infections would be a reduction in the chronic nature of African trypanosomiasis.

Published in the journal: A Conserved DNA Repeat Promotes Selection of a Diverse Repertoire of Surface Antigens from the Genomic Archive. PLoS Genet 12(5): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005994

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005994Summary

Chromosomal translocations can fuel genetic change or cause catastrophic genomic damage. African trypanosomes, exemplified by Trypanosoma brucei sub-species, are unicellular parasites that can chronically infect their human and livestock hosts by using a strategy of antigenic variation by which they repeatedly change their protein coats. Switching the surface coat requires the accurate selection and translocation of a single silent coat gene, from a large genomic archive, into an actively transcribed site. How the coat genes from within this deep archive are selected and activated was unproven. Here we show that a specific repetitive DNA sequence is required to access coat genes from diverse sites within the genome. The likely outcome of restricting this process of coat gene selection in natural infections would be a reduction in the chronic nature of African trypanosomiasis.

Introduction

African trypanosomes are protozoan parasites that have dedicated more than 20% of their coding capacity [1,2] and 10% total cellular protein content [3] to a single biological function. To survive in the challenging environmental niche of the mammalian bloodstream, subspecies of Trypanosoma brucei must regularly change their antigenic glycoprotein coat. In this manner, they are able to escape the antibody-mediated immune response of their host to cause a chronic infection of the bloodstream that results in death of both humans (African sleeping sickness) and livestock (nagana) if left untreated [4]. Each parasite’s coat is composed of a densely packed single member of a large family of Variant Surface Glycoproteins (VSG) [5], which are thought to share a conserved membrane-bound structure but are encoded by highly divergent genes [2].

The T. brucei genome encodes more than 2000 VSG genes and VSG pseudogenes within a genome consisting of 11 megabase chromosomes (MBC), a variable number (usually 5–10) of intermediate chromosomes, and about 100 minichromosomes (MC) [2,6]. Yet, only one VSG is expressed at a given time from one of ~15 possible Bloodstream Expression Sites (BES) located at the subtelomeres of MBCs [7]. BESs share a similar sequence and organization, including an RNA polymerase I promoter, a series of Expression Site Associated Genes (ESAGs), a large region of repetitive DNA (70-bp repeats) that precede VSG gene, which is located a short distance upstream of telomere [7]. While minichromosomal VSGs are also subtelomeric, the majority of the VSG archive is located in VSG arrays on the arms of the MBCs [1]. Survival of T. brucei in the bloodstream requires the regular activation of silent VSGs from the genomic archive.

Switching from the expression of one VSG coat to the next predominantly occurs by three genetic mechanisms. A change in the BES being transcribed, resulting in the expression of its subtelomeric VSG, is termed In Situ (IS) switching [8]. Telomeric Exchange (TE) is homologous recombination between subtelomeres that results in the exchange of a silent VSG with one in the active BES, retaining both VSG genes [9]. In contrast, duplicative Gene Conversion (GC), as the name implies, results in the duplication of a silent VSG donor into the active BES and simultaneous deletion of the previously expressed VSG gene [10]. Unlike IS and TE, which activate silent VSGs already located at subtelomeric sites, GC is the mechanism of VSG switching that permits access to the entire VSG archive (BES, MC, and MBC arrays). GC is thought to be the predominant mechanism during natural infections [11] and can be activated under laboratory conditions, where rates of switching are low (~1x10-5), by increasing subtelomeric DNA breakage at the active BES [12–14]. Among all switching mechanisms there appears to be a semi-predictable hierarchy of VSG gene selection that begins with the selection of BES-encoded subtelomeric VSGs, followed by non-BES subtelomeric VSGs (such as those on MCs), and finally those from non-telomeric sites in the genome (loosely organized VSG arrays) [15]. Selection of VSGs from other BESs is highly favored during early switch events and is the most common gene selection preference observed under laboratory conditions [12,15]. This is probably because BESs have very similar DNA sequences, including regions of near identity for many kilobases, which would provide ample homology for recombination during gene conversion [7]. Selection of BES-encoded VSGs alone, of which there are about 15, would not be expected to support chronic T. brucei infection.

DNA repeat expansions are a common source of genomic translocations (like gene conversions) and genomic instability among eukaryotic genomes, and can result in genetic disorders in humans (reviewed in [16]). Thus, the discovery that the 5’ limit of translocation during VSG switching was a long region of repetitive DNA (termed the 70-bp repeats based on their approximate length) led to the predictions that these repeats are possible sites of the DNA lesions that initiate switching, or the source of DNA homology for VSG donor selection in recombination-based switching [17–19]. Often described as imperfect AT-rich 70-bp repeats, observations that this sequence also occurs proximal to VSGs within the genomic archive bolstered the VSG selection prediction [1]. Similarly, their predicted role in forming DNA lesions fell into disfavor when it was shown that gene conversion in trypanosomes grown in vitro, albeit at a very low frequency, does not require 70-bp repeats [20], favoring the proposed role in providing homology for recombination.

Yet, the proposed function of the 70-bp repeats was never experimentally tested. This was due, in part, to the inability to analyze these events due to low levels of switching that occur under laboratory conditions. Here, we artificially increase the rate of VSG switching to determine how the 70-bp repeats affect VSG donor selection during gene conversion. The data presented herein confirm that the 70-bp repeats can function to promote selection of VSGs from throughout the silent repertoire. In addition, an expanded analysis of the 70-bp repeat sequence enabled us to identify a minimal 70-bp repeat region that promotes archival VSG selection. In the course of this analysis we also discovered that the 70-bp repeats could have previously unreported affects on the frequency of VSG switching and cell cycle progression. Furthermore, our data showed that the 70-bp repeats can direct VSG selection away from other BESs, their closest homologs, and toward the genomic archive, which has mechanistic and physiological implications. Our findings suggest that the 70-bp repeat regions are required for the normal outcomes of VSG switching, and thus the ability of T. brucei to survive in its host during a chronic infection.

Results

Conservation of the 70-bp repeat sequence within and among the genomes of African trypanosomes

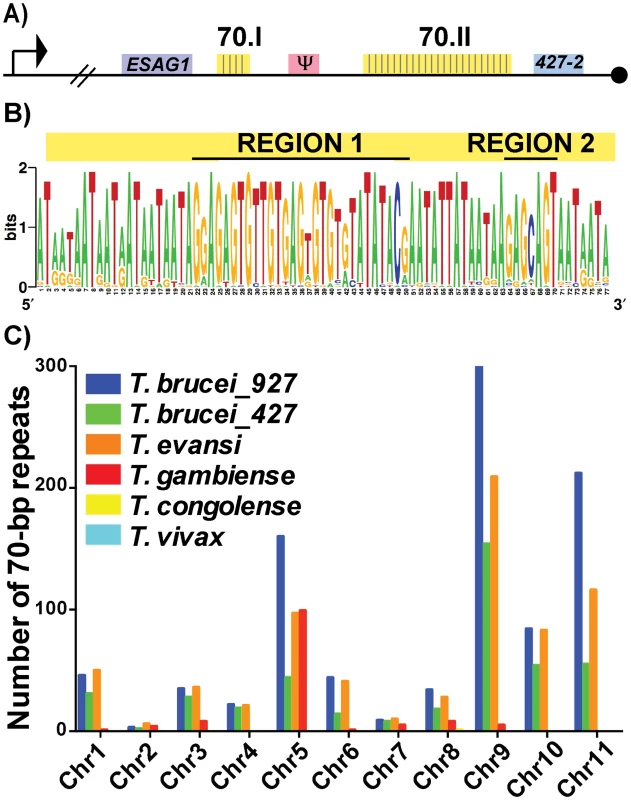

To investigate the putative functions of the 70-bp repeats we first subjected the two repeat regions of Lister427 BES1 (Fig 1A—70.I & 70.II) to fine mapping and the 42 identified repeat sequences were used to produce a consensus sequence logo (Fig 1B). Similar to previous studies of more limited sample sizes, the repeats were an average of 76-bp (usually running either 77-bp or 75-bp in length) and were AT-rich (78%). For the sake of consistency within the literature, the 70-bp repeat nomenclature will be maintained [17–19]. These data support previous work suggesting that the 70-bp sequence is highly conserved [18] and identified two pronounced GC-rich regions (Region1 and Region 2). Expanding the analysis to include repeat regions of additional BESs, within both Lister427 [7] and TREU927 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/downloads/protozoa/trypanosoma-brucei.html) genomes, showed that this conservation is consistent among T. brucei BES regions (S1 Fig and S1 Dataset). Thus, in the majority of BESs, a long region of conserved 70-bp sequence is maintained in close proximity to the sub-telomeric VSG gene.

Fig. 1. Conservation and genomic distribution of the 70-bp repeat sequence.

A) Map of T. brucei Lister 427 BES1 with promoter (bent arrow), terminal ESAG (ESAG1), VSG (blue), VSG pseudogene (pink), telomere (black circle), and 70-bp repeat regions (yellow) illustrated (70.I contains 3 repeats and 70.II contains 39 repeats). B) The identified 70-bp consensus sequence from shown as a logo created from the 42 repeats found in BES1 (weblogo.berkely.edu). C) Graph of the number of 70b-bp repeats (determined by e-value>40, identities> 70%, and length>40bp) enumerated per chromosome from the genomes of T. brucei brucei TREU927 (blue), T. brucei brucei Lister427 (green), T. evansi STIB805 (orange), T. brucei gambiense DAL972 (red), T. congolense IL3000 (yellow), and T. vivax Y486 (light blue). Aside from the BES sequences from these two genomes, direct comparison of the frequency and organization of the 70-bp repeat sequence within available African Trypanosome genomes is limited by the variable quality of each genomic assembly, especially near the subtelomeric regions (http://tritrypdb.org/tritrypdb/). Operating within these confines, we sought to determine the prevalence of the 70-bp regions by performing a BLAST analysis of the consensus sequence against each chromosome of the available genomes (Fig 1C). While the 70-bp repeat sequence was not found in the genomes of South American trypanosome species, which do not undergo antigenic variation, it was abundant within the genomes of T. brucei TREU 927, T. brucei Lister 427, T. evansi, and T. brucei gambiense (a human-infectious subspecies). The abundance of 70-bp repeats in T. evansi (an emerging pathogen among livestock in the Middle East and Asia) was anticipated as its genome has extensive similarity with that of T. brucei [21]. The observation that T. b. gambiense has fewer 70-bp repeats per chromosome than the other T. brucei subspecies is difficult to interpret as it could be an artifact resulting from the sequencing of its genome (the genome of another human-infectious form, T. b. rhodesiense, has not been sequenced). In contrast, the absence of the 70-bp repeats from T. congolense and T. vivax could reflect real biological differences in antigenic variation between these very distinct species [22].

In addition to BESs and megabase chromosomes, VSG-containing contigs from T. brucei Lister 427 minichromosomes contained the 70-bp consensus sequence in the proximity of VSGs (usually approximately 1.5 kb upstream) (S1 Table) [2]. Thus, the conserved 70-bp repeat sequence identified here is widely distributed among the genomes of African trypanosomes with anticipated positioning in long tracts on BESs and shorter tracts on the megabase and minichromosome arms in the proximity of VSG genes. The genomic conservation and distribution of this sequence lends support to the hypothesis that the 70-bp repeats contribute to homologous pairing and VSG donor selection during GC [20].

70-bp repeats promote VSG selection from diverse genomic sites

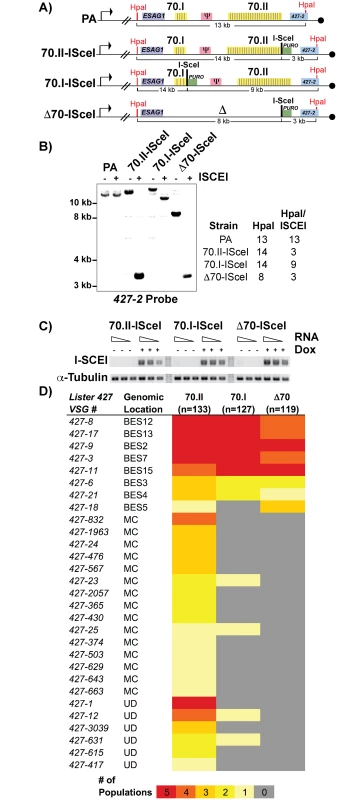

To test this hypothesis, we sought to genetically manipulate the 70-bp repeats of the active BES and monitor the effects on switching, but were hindered by the naturally low frequency of in vitro switching (~1x10-6) in the Lister 427 strain. We therefore established cell lines in which DNA double-stranded breaks (DSB) could be induced in the actively expressed BES, to increase the depth of analysis by increasing the frequency of switching by GC [12,14]. An ISceI enzymatic cleavage site was introduced into BES1 proximal to a long region of repeats (“70.II-ISceI”, 39 repeat iterations), a short region of repeats (“70.I-ISceI”, 3 repeats) and in a repeat deletion mutant (“Δ70-ISceI”, no repeats) (Fig 2A; oligos used for constructs are in S1 Text). The veracity of the ISceI cleavage sites was confirmed by Southern blot analysis and the consistent expression of the ISCEI enzyme among lines confirmed (Fig 1B and 1C). Five populations of each ISceI-bearing strain (70.II-ISceI, 70.I-ISceI, or Δ70-ISceI) were grown for 3 days under normal ( - doxycycline) or DSB-inducing (+ doxycycline) conditions, and cells that had switched from their initial VSG (427–2) to an alternative VSG gene were isolated over magnetic cell-sorting (MACS) columns, as described [12,13] (experimental pipeline details S2 Fig). The resulting VSG-switched cells were cloned by limiting dilution and the resulting clones were used to determine both the mechanism of switching (using established genetic methods [13,23]) and to identify the newly expressed VSG (using traditional RT-PCR followed by sequence analysis and VSGnome BLAST alignment at http://tryps.rockefeller.edu) for more than 100 clones from each line (S2–S4 Tables). As anticipated, based on previous studies [12,13], following DSB induction, all lines switched by GC and preferentially favored the selection of BES-encoded VSG donors (Fig 2D). Notably, when the 70-bp repeat region proximal to ISceI was long (70.II-ISceI), 48% of the selected VSGs arose from minichromosomal (MC) or undetermined sites (UD) as opposed to homologous BESs (Fig 2D). In contrast, ISceI break formation proximal to a very small repeat region (70.I-ISceI) or after repeat deletion (Δ70-ISceI) resulted in the selection of BES encoded VSGs in 98% or 100% of clones, respectively (Fig 2D). Thus, short or deleted 70-bp repeats appeared defective in selecting VSGs from the VSG genomic archive when compared with longer 70-bp repeat regions.

Fig. 2. Effects of 70-bp repeats on VSG donor selection and switching.

A) Map of BES1 modifications (in comparison to PA) used in analyzed strains illustrate ISceI site introduction with puromycin marker (green), HpaI restriction site location (red) used in Southern blot conformation is indicated along with anticipated sizes following digestion. B) Southern blots of representative clones from each BES1 modified line are shown for HpaI and HpaI/ISceI digestions probed with terminal BES1 VSG (427–2). C) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR of ISCEI enzyme expression for a 5-fold dilution of input RNA under non-inducting (- Dox) and inducing (+ Dox) conditions alongside a tubulin control. D) Heat map showing the number of populations in which clones (n = number of clones analyzed per strain) expressing a specific VSG arose: Lister427 VSG reference number and the predicted genomic locus (BES, MC, or undetermined [UD]) of the VSG are shown together with the number of populations (out of 5 total), in which it arose as depicted by color intensity using the color key (bottom). Gene conversion replaces defective 70-bp repeat regions

Following a DSB, either naturally occurring or induced, single-stranded DNA is liberated initiating a homology search that is likely resolved by break-induced replication. Genetic analysis of individual switched clones can determine the extent of DNA transferred from the donor site into the active BES during GC. One of the most common switching events observed was between BES1 and BES7, resulting in the expression of VSG427-3. Using a BES7 probe upstream of the VSG, clones that have recombined VSG427-3 into BES1 will form a new band (upon appropriate restriction digestion) whose length indicates the region of BES7 transferred during GC. The resulting data indicate how GC affects 70-bp repeat maintenance or the recovery of defective repeat regions (Fig 3).

Fig. 3. BES1 repeat content following GC with BES7.

Field-inversion gel electrophoresis and Southern blot analysis of VSG427-3 switched clones arising from A) BES1-70.II-ISceI or B) BES1-Δ70-ISceI GC with silent BES7 donor digested BglII digest or HindIII, respectively. BES7 probe (red bar) proximal to 427–3 results in the formation of a new band whose size approximates the region of BES7 transferred during gene conversion. Diagrams to the right of Southern blots show the predicted composition of the newly formed band. Clones arising from a BES1 with normal 70-bp repeats (Fig 3A—70.II-ISceI) showed a variety of outcomes that included the addition of no new repeats (5_H9 = 6.6 kb), partial addition of BES7 repeats (2_E5 ~8 kb & 5_F6 > 10 kb), or the translocation of full length BES7 repeats (2_B8 > 12 kb). In contrast, when BES1 harbors no 70-bp repeats (Fig 3B—Δ70-ISceI) the full region of BES7 repeats was consistently incorporated into BES1 during switching (1_A4, 3_A2, & 3_B10 > 12 kb). In one clone it appears that a region larger than the BES7 repeats was incorporated into BES1 (3_E9); similar long-range recombination events have been reported during GC switching in other studies [23]. It should be noted that the determination of the precise lengths of the regions transferred from BES7 to BES2 is hindered by the fact that the exact length of the repeats encoded in BES7 is unknown. Thus, we observe that the 70-bp repeat region in the active BES can be repopulated, maintained, or extended during GC-based recombination with another BES.

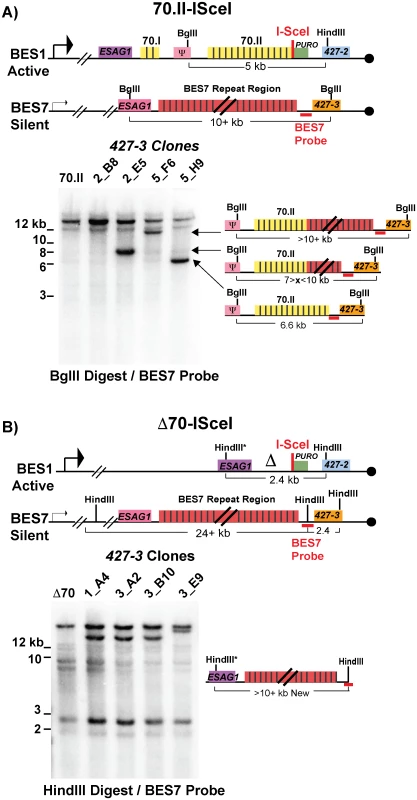

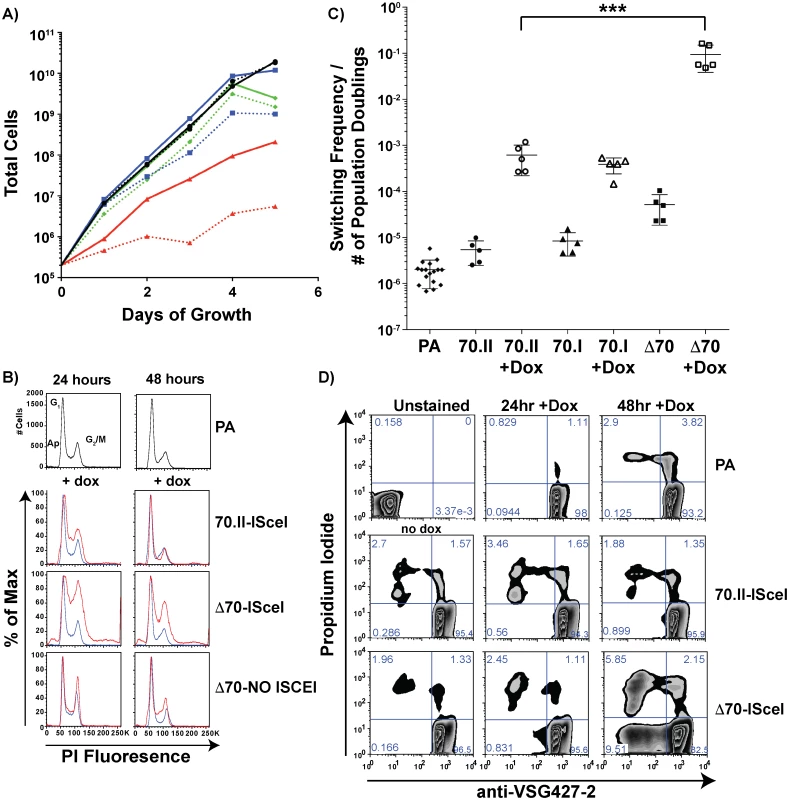

Effects of 70-bp repeats on growth, cell cycle progression, and VSG switching

The growth rate and frequency of VSG switching following DSB induction could affect the number of VSG donors selected. To verify that the VSG donor selection phenotypes reported in Fig 2 were dependent solely on the effect of the 70-bp repeat regions, cellular growth and VSG switching were monitored in these lines. Following doxycycline induction, all lines harboring an ISceI site in BES1 displayed a growth defect when compared to the parental line. For strains with intact 70-bp repeats (Fig 4A—70.II-ISceI [blue lines]) the delay in growth was modest, yet DSB formation in the 70-bp deletion mutant (Δ70-ISceI) exacerbated a pronounced preexisting growth defect (Fig 4A—Red lines). We predicted that the growth defect observed without doxycycline induction resulted from leaky expression of the ISCEI enzyme (a known complication of expression from the rDNA spacer [24]), and tested this prediction using a 70-bp repeat deletion mutant that did not harbor the ISCEI enzyme (Δ70-NO ISCEI). Deletion of the repeats from BES1 did not result in a growth defect in the absence of the ISCEI (as anticipated from previous work on a similar construction [20,25]). Thus, the observed growth defects in ISCEI-expressing lines appear to result from DSB formation in the active BES, which was most pronounced when the 70-bp repeats were deleted.

Fig. 4. Growth and VSG switching in 70-bp repeat analysis lines.

A) Growth of 70-bp repeat-analysis strains is shown over 5 days of consistent cell passage with (dashed lines) and without (solid lines) doxycycline induction for the ISCEI-bearing parental line (black ●), 70.II-ISceI (blue ■), and Δ70-ISceI (red ▲), as well as Δ70-No ISceI (green ◆). B) DNA content frequency histogram measured by PI fluorescence used to estimate the percentage of cells in G1 and G2/M at 24 & 48 hours following doxycycline induction for ISceI bearing strains (red) in comparison with parental strain (blue). C) Switching frequencies of 70-bp repeat analysis strains (PA = ♦, 70.II = ●, 70.I = ▲, Δ70 = ■) during growth with (filled symbol) or without (hollow symbol) doxycycline induction (three days) is normalized to the number of population doublings (***<0.0001, F-test) as determined from growth data in panel A. D) Flow-cytometry analysis of proportion of cells without VSG427-2 (x-axis) and staining with propidium iodide (y-axis), as a measure of VSG switching and cell death, respectively, shown as a zebra plot with frequencies of each population per quadrant shown. Because DSB formation can activate a cell cycle checkpoint (reviewed in [26,27]) and the Δ70-ISceI cell line has a growth defect, the effects of DSB formation on the cell cycle were examined in these lines. Cells harboring a DSB site near wild-type 70-bp repeat regions resulted in a minor cell cycle delay at 24 hours that was largely resolved by 48 hours (Fig 4B—70-II-ISceI). In contrast, deletion of the BES1 70-bp repeats resulted in a severe cell cycle defect that was only partially resolved at 48 hours post-induction (Fig 4B—Δ70-ISceI). To determine if the defect results from DSB formation, cell-cycle progression was monitored in the 70-bp repeat deletion mutant that does not harbor ISCEI (Δ70-No ISCEI). These cells did not have the cell cycle defect observed in ISCEI-expressing lines at 24 hours, but did display minor accumulation of cells in S-phase at 48 hours post-induction (this could result from naturally occurring breaks arising late in growth that are not resolved normally in this line). Together these data indicate that the growth delays observed in these cell lines are associated with cell cycle defects arising from DSB formation and suggest that the deletion of 70-bp repeats from the active site exacerbates these defects.

Multiple studies have shown that induction of ISceI-induced breaks in the active BES results in increased VSG switching, but the precise amount of switching can vary depending on the location of DSB formation an the activity of the ISCEI enzyme [12,14]. To determine if the diversity of VSG gene selection (reported in Fig 2) resulted from differences in switching dynamics, the VSG switching frequency was quantified for the ISceI-bearing cell lines and normalized to the number of population doublings (Fig 4C, normalization derived from Fig 4A). DNA break formation proximal to the long repeat region (Fig 4C—70.II) resulted in approximately 100-fold increase in switching, compared to wild-type cells, as previously observed [12]. DSB formation in the proximity of only three 70-bp repeats (70.I) resulted in a similar switching frequency, but a vastly different diversity in the selected VSGs (98% BES encoded VSGs selected compared with 52% in the 70.II cell line [Fig 2]). This comparison underscores the role of the 70-bp repeat region in selection of VSGs from the genomic archive. However, deletion of the 70-bp repeats resulted in a switching frequency, upon DSB induction, that was 10–100 fold greater than strains harboring 70-bp repeats (Fig 4C—Δ70-ISceI), such that 1 in 10 cells had switched (a frequency observable by flow-cytometry alone [Fig 4D]). This was in contrast with the previous report of a similarly constructed strain [12], probably because the slow growth phenotype had, in the previous study, led to the selection of a clone in which the ISceI site or enzymatic function was lost. The switching frequency calculated after DSB formation in the 70-ISceI line is likely affected by the observed growth and cell cycle defects, so is not directly comparable to the values calculated for isogenic lines containing repeats, where DSB-induction does not noticeably affect growth and cell-cycle progression. Nonetheless, the diminished capacity for VSG donor selection in the Δ70-ISceI line was definitely not the result of a reduction in switching frequency.

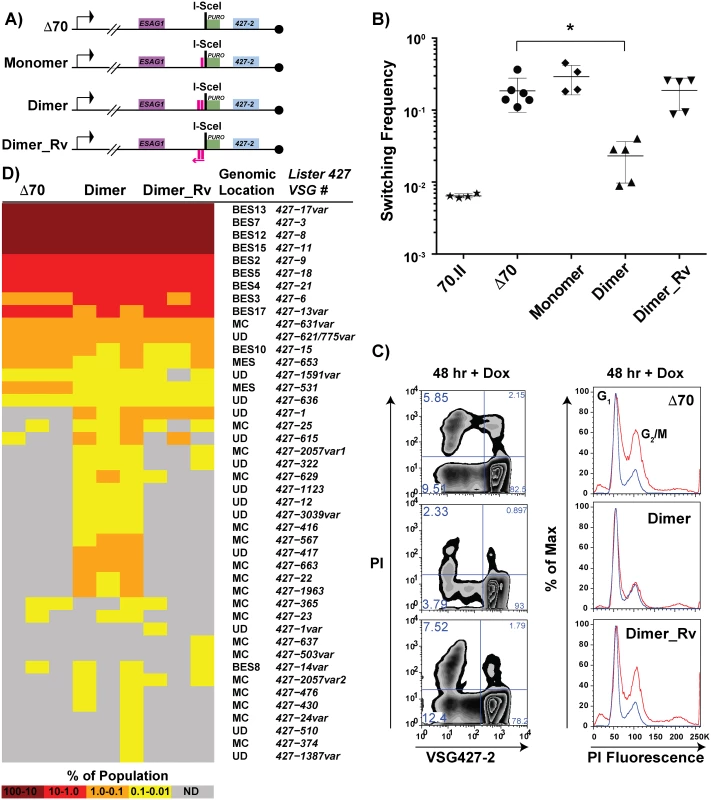

Identification of a minimal functional 70-bp repeat sequence

Based on the observation that the 70.I-ISceI has a normal switching frequency and a modest capacity for archival VSG donor selection, we predicted that a minimal 70-bp repeat region could recapitulate the phenotypes associated with the long, cognate 70-bp repeat regions. To test this prediction, the conserved 70-bp repeat sequence presented in Fig 1 was used to design synthetic 70-bp regions, which were introduced into the Δ70-ISceI landscape to produce stable cell lines and analyze their phenotypes. The resulting cell lines, which harbor discrete repeat regions proximal to the ISceI site, are as follows: “Monomer”, which bears a single 70-bp repeat; “Dimer”, consisting of two monomeric units separated by a cognate spacer (ATAATA); and “Dimer_Rv”, which harbors the Dimer sequence in the opposite orientation with respect to transcription (Fig 5A, repeat insertion sequences shown in S1 Text). DSB induction in the Dimer cell line reduced the VSG switching frequency nearly 10-fold from Δ70-ISceI levels (2.3x10-2 compared with 1.9x10-1, respectively), where strains harboring the 70-bp repeat Monomer or Dimer_Rv sequences were unchanged from the deletion mutant (Fig 5B). Similarly, the growth and cell cycle defects observed in the absence of 70-bp repeats (Fig 4—Δ 70-ISceI) were significantly improved by the addition of the Dimer region, while this was not the case for Monomer or Dimer_Rv lines (Fig 5C and S3 Fig). (Phenotypes of an additional mutated repeat line “Mut_Dimer” did not suppress the Δ70-ISceI phenotypes [shown only in S3 Fig]). If VSG switching and cell growth phenotypes correlate with VSG donor selection (as suggested by data in Figs 2 and 3), we would expect the Dimer cell line to result in selection of VSGs from within the genomic archive.

Fig. 5. Effects of engineered 70-bp repeat sequences on VSG switching and donor selection.

A) BES1 maps of cell lines bearing repeat deletions (Δ70) and introductions, shown as pink boxes, or in reverse (pink arrow). B) Observed switching frequencies of doxycycline induced strains bearing alternative repeat regions: wild-type repeats (70.II, ★), no repeats (Δ70, ●), monomeric motif (Monomer, ◆), dimeric motif (Dimer, ▴), and reverse dimeric motif (Dimer_Rv). Difference in switching between Δ70 and Dimer motif introduction is statistically significant (asterisk over bracket pval = 0.027). C) Flow-cytometry analysis of switched cells (427–2 negative population) and cell cycle (DNA content frequency histogram measured by PI fluorescence) at 48 hours following doxycycline induction. D) VSG-seq analysis of MACS-isolated switchers from three biological replicates of Δ70, Dimer, & Dimer_Rv is shown in the form of a heat diagram where the color intensity reflects the proportion of each VSG RNA in the population. The Lister427 VSG number and its predicted genomic location are shown on the right of the heat diagram where var indicates that the assembled VSG sequence had minor sequence variations from the most similar 427 reference VSG. To determine the effect of the synthetic repeat sequences on VSG donor selection at an increased depth, RNA was extracted from DSB-induced post-MACS eluates from biological triplicates of these lines for VSG-seq analysis [28]. The VSG-Seq method is distinct from the clonal analysis of VSG donor selection presented in Fig 2 in that it permits the identification of VSG RNAs comprising as little as 0.01% of the population [28]. At this sensitivity, we observed that the line lacking repeats in the active BES (Δ70-ISceI) could occasionally select VSGs from sites other than BESs (Fig 5D, supported by data in S5 Table), including two from metacyclic expression sites (MES), one from a MC, and four from other undetermined (UD) loci. Introduction of the repeat Dimer resulted in a significant (pval = 0.0026) increase in the number of VSGs selected when compared with the no-repeat line (average of 18 VSGs in Δ70-ISceI and 35 VSGs in Dimer populations, SI 9). This near doubling in the diversity of VSG selection was the result of a substantial increase in MC VSG selection (pval = 0.005, average Δ70-ISceI = 1 MC & Dimer = 11 MC) and a more modest, but statistically significant, increase in the selection of VSGs arising from undetermined loci (pval = 0.001, average Δ70-ISceI = 4 UD & Dimer = 12 UD). In contrast, addition of the Dimer_Rv sequence did not result in a significant increase in the selected VSG repertoire (pval = 0.205), although some subtle differences between Δ70-ISceI and Dimer_Rv strains can be observed (Fig 5D). These data have identified a minimal 70-bp repeat region able to partially suppress the collection phenotypes (i.e. cell growth defect, cell cycle delay, increased VSG switching, and reduced VSG donor selection) associated with DSB formation proximal to a 70-bp repeat deletion mutant and result in phenotypes similar to lines harboring cognate 70-bp repeats.

Discussion

While unbalanced chromosomal translocations can fuel evolutionary change, they are generally deleterious to eukaryotic, especially mammalian, genomes. African trypanosomes are a useful model of chromosomal translocations because their essential pathogenic process, antigenic variation, depends on them. The early observation that genetic transposition of a new VSG into the active BES terminates within a tract of repetitive DNA inspired passionate functional speculation. Yet, the available sequence information and genetic tools of the time (and of studies that followed in the 1990s) restricted the scope of possible analyses. Thus, a viable hypothesis, that the repeats provide homology for recombination, became widely accepted [29,30] but was not tested. In the present study we applied a variety of recently available sequencing databases (BESs, trypanosome genomes, and VSGnome), a next-generation sequencing method (VSG-seq), genetic tools (including ISceI DSB induction), and cell biology assays (such as VSG switching frequency quantification) to test this long-standing hypothesis.

Classic sequencing approaches of the mid-1980s allowed three groups to determine the essential characteristics of the 70-bp repeats [17–19] and analysis of cosmid clones suggested that VSG genes and 70-bp repeats were widely distributed in the genome [31]. Completion of the first African trypanosome genome sequencing project (TREU927) confirmed, in detail, that the 70-bp repeat sequence is not only found at the BES subtelomeres but also proximal to VSGs on the chromosome arms [1]. Yet, at that time, determining the degree of 70-bp repeat conservation within the genome was hindered by inherent challenges associated with assembling the sequences at the ends of chromosomes. Here, we utilized existing comprehensive BES sequence data (ABI 3730, with approximately 700-bp read length [7]) to produce a 70-bp consensus sequence and confirm its degree conservation among numerous BESs. The length and conservation of this sequence corroborates some early findings [18], but disagree somewhat with the often-asserted position that the 70-bp repeats are imperfect and have variable length [7,30,32,33]. While the length of the AT-rich regions between conserved repeating units can vary, as reported [19], we would suggest that the data presented in this study highlight the significance of the conserved repeating unit presented in Fig 1. It is important to note that the findings reported here do not address the putative function of the repetitive regions in DNA instability, the proposed function of the triplet repeats [19,34].

The order and conservation of the 70-bp repeats inspired us to revisit the question of function. Previous deletion of the BES1 70-bp repeat regions showed that the repeats themselves are not required for the low levels of gene conversion observed in vitro [20]. This finding was significant in that it challenged long-held speculation that the repeats function as specific endonuclease-cleavage sites. The recent availability of the Liste r427 VSGnome (sequences of all VSG genes within the genomic archive) [2] enabled testing of the second predicted function of the 70-bp repeats, namely providing homology in VSG donor selection. However, the amount of switching that occurs in vitro is too low (1x10-6) to permit a substantive analysis of VSG switching outcomes. This limitation was overcome through utilization of an artificial DNA breaking system that has been shown to increase the VSG switching frequency [12,14], which occurs by gene conversion, in a similar manner to those that occur through more natural DNA break systems analyzed [13]. Use of the established ISceI endonuclease cleavage system for DSB formation enabled in-depth analysis of how different regions, and mutations, of 70-bp repeats affect VSG switching and its outcomes. The caveat, of course, is that ISceI is an artificial system and limits our interpretation of the implications for naturally occurring infections. Nonetheless, this genetic tool enabled the observation of genetic phenomena that would not have been detectable otherwise. Thus, individual clonal analysis of switched cells using the VSGnome resource allowed us to demonstrate that the BES encoded repetitive regions are required for selection of a normal repertoire of VSG genes, the first observed phenotype for the 70-bp repeats.

The increase in switching frequency following DNA break formation in the BES1 constructions presented here also enabled us to observe unexpected outcomes of 70-bp repeat deletion and variations. Among these cell lines we observed that the 70-bp repeats have previously unappreciated and apparently connected effects on cell growth, cell cycle progression, and VSG switching following DSB formation. The observation that deletion of 70-bp repeats results in significant cell cycle delays following DSB formation could suggest that, in comparison to lines harboring wild-type repeats, this cell line is defective for DNA break repair. The fact that the same mutant cell line also switches much more frequently and results in increased cell death may suggest that cell lines harboring functional repeats process the DNA breaks more efficiently, as evidenced by the minimal cell cycle delay at 24 hours in 70.II-ISceI. These effects appear to depend on ISceI-induced DSB formation, as shown by the Δ70-No ISCEI cell line, whose behavior was largely unaffected by the repeat deletion, as expected from the literature [20]. This collection of phenotypes was consistent among all cell lines that harbor “functional” (70.II-ISceI, 70.I-ISceI, and Dimer) vs. “dysfunctional” (Δ70-ISceI, Monomer, & Dimer_Rv) 70-bp repeat regions. Alternatively, similar phenotypes might be observed if the 70-bp repeats affect the ISceI cutting efficiency. This could occur if there was steric hindrance at the cut site, which could result from binding proteins or DNA secondary structure. Further exploration of the phenotypic alterations associated with the 70-bp repeat variations could lead to new mechanistic understanding of the requirements for the chromosomal translocations that support T. brucei antigenic variation.

Diverse pathogens utilize antigenic variation to escape the host immune system; among them T. brucei has the most extensive archive of surface antigen genes (the VSGs) [35]. Yet, the extensive repertoire of VSG genes would be useless if they could not be activated. Here we have shown that the 70-bp repeats are a key feature that permits access to the VSG archive. This result experimentally validates previous speculations and extends our understanding by highlighting the specific DNA element, sequence, and orientation required for selection, at a depth of analysis only recently made possible by VSG-seq [28]. It is unclear at this time if the 70-bp repeats influence the formation of new VSG gene variants through mosaicism, a known from of repertoire expansion mediated by recombination within VSG coding sequences. At the sensitivity of VSG-seq and the discriminatory ability of its cognate assembly component, genes identified as VSG-variants (Fig 5D—“var”) appear to share similarities with mosaic VSGs.

BESs are essentially long homologous regions that not only contain the same organization, genes, and genetic elements, but are also nearly identical to one another at the sequence level for more than 50 kilobases [7]. As homology length generally determines the frequency of recombination [36], it is not unexpected that homologous BESs (harboring many kb of 70-bp repeats) are primary genomic sites favored during VSG selection. What is surprising is the extent to which regions of wild-type repeats select sites other than BESs (48% of VSGs selected following induction of 70.II-ISceI). While VSG donor selection could be based on homology alone, our findings raise the possibility that another external factor, acting on the 70-bp repeats, promotes selection of non-BES encoded VSGs. This effect could be in the form of repeat-specific DNA-binding proteins or be associated with subnuclear positioning during gene conversion, which is known to affect VSG expression [37]. Overall, this study demonstrates that, following DSB formation and subsequent liberation of ssDNA, the 70-bp repeats guide homologous pairing toward diverse genomic sites that harbor the VSG archive, a repertoire-expansion function that is crucial to the long-term survival of the parasite in its host. While the intricacies of VSG switching may be unique to African trypanosome parasites, the genetic processes described here have implications for chromosomal translocations that occur within other eukaryotic genomes.

Methods

Analysis of repeat sequence conservation and genomic distribution

The conserved repeat sequence was identified visually based on the BES sequences from T. brucei Lister 427, and logos produced by http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi. The same approach was then applied to TREU927 BES sequences (S1 Fig and S1 Dataset). The consensus sequence from the BES1 repeat logo was used to BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) the TREU927 genome and hits were called based on Max Score and Percent Identity. VSG proximity was called based on the TREU927 genome annotation. Contigs resulting from deep sequencing of the MC DNA fraction were used to determine repeat conservation and distance with respect to MC VSG genes [2]. The sequence of each of the 11 megabase chromosomes from TREU927 (T. brucei brucei), Lister427 (T. brucei brucei), DAL972 (T. brucei gambiense), IL3000 (T. congolense), STIB805 (T. evansi), and Y486 (T. vivax) genomes were downloaded from http://tritrypdb.org/tritrypdb/ and BLASTed (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) against the 77 bp consensus sequence (Fig 1A). Hits were counted as 70-bp repeats if their length was greater than 45 bp, had and e-value was greater than 40, and their identity was greater than 70%.

Trypanosoma brucei line constructions, growth, and cell cycle analysis

Cell lines were generated from Lister427 bloodstream-form trypanosomes derived from the “single marker” (SM) line [38]. “Wild-type” in this study was SM with a blasticidin-resistance gene inserted at the active BES1 promoter, which can be put under blasticidin selection to prevent BES transcriptional switching, as was done in the present study only to stabilize the population until the time of DSB induction. The parental line (PA) of all ISCEI introduction experiments is “SM-NLS-ISCEI-HA” [12], which has a copy of a tetracycline-inducible ISCEI enzyme encoded in the rDNA spacer region and a hygromycin resistance marker incorporated at the BES1 promoter. The ISceI cut site and recombinatorial homology to specific locations of BES1 were added to a puromycin selection cassette by PCR (oligos found in S1 Text), cloned into a pGEMT vector, and DNA fragments were liberated by digest prior to transfection using the AMAXA Nucleofector [39]. Sequences were confirmed and DNA fragments librated from the vector for AMAXA transfections. Transformants were selected in 10 μg/mL puromycin, screened for BES1 incorporation by PCR, and confirmed by Southern blot analysis. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed using Superscript III for cDNA amplification as described (thermofisher.com) followed by 25 cycles of PCR amplification using taq polymerase. Cell lines were cultured in vitro in HMI-9 medium at 37°C [40] and ISCEI induced using 1μg/mL doxycycline (dox). Strain growth was monitored by continuous passage by diluting daily to 1x105 cells and measuring additive growth over 5 days. Standard flow-cytometry approaches were used to measure cell death and cell cycle progression using propidium iodide [41].

Southern blot analysis

DNA restriction fragments were separated by either standard agarose gel electrophoresis (1–12 kb) or Field Inversion Gel Electrophoresis (FIGE) (1–25 kb) using established methods. Southern blots were produced using capillary blotting and neutral transfer paper (GE Scientific). DNA probes were made by PCR amplification, 32P-radiolabeled using Prime-It II Random Labeing Kit (Stratagene), and purified over G-50 microcolumns. Blots were probe-hybridized, washed and visualized by phosphorimaging (GE Healthcare).

Isolation and analysis of switched clones

An experimental pipeline was established for the direct comparison of switching frequency, mechanism, and VSG donor selection (S2 Fig). Cells were grown from 5,000 cells to 50 million cells in media with or without doxycycline. Approximately 50 million cells were harvested and depleted over magnetic-activated cell sorting columns (MACS) using anti-Lister427 VSG-2 antibody (monoclonal antibody available for order through Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center https://www.mskcc.org/research-advantage/core-facilities/monoclonal-antibody-core-facility) as described previously [13]. Half of the resulting “switcher-enriched” cells were used to quantify switching by flow-cytometry (measuring the number of switched cells as a proportion of the total population, as previously described [12]) and the other half was plated to limiting dilution and single cell clones were recovered and replica-plated for genetic analysis (similar to previous studies [13,23]), RNA extraction and VSG analysis, or long-term storage. Mechanisms of switching were determined by a combination of genetic tests and antibiotic sensitivity, as described [13,23]. RNA from clones was used to make cDNA, and the VSG was amplified by RT-PCR and sequenced directly from PCR products. The resulting sequence for each clone was aligned to the VSGnome database BLAST server (http://129.85.245.250/index.html) to identify the top VSG hit [2].

VSG-seq analysis of 70-bp repeat modified strains

Cell lines bearing BES1 70-bp deletion or alterations were doxycycline induced for ISCEI DSB formation and the resulting switched cells isolated by MACS, as described above. RNA was extracted from three biological replicate populations of each induced strain and this material was used to prepare VSG-seq libraries [28].

A reference VSG database was created from VSG sequences assembled with the de novo assembler Trinity [42]. Trinity was first run on each library individually, and then run on libraries grouped by condition. All open reading frames (ORFs) were identified in each assembled contig, where an ORF is defined as a start codon to stop codon, a start codon to the end of a contig, or the beginning of a contig to a stop codon. BLASTn (v2.2.28+) was used to identify VSG ORFs [43] and ORFS with an alignment to a 427 VSG sequence with an e-value of < 1e-10 were considered true VSG sequences. The sets of VSG sequences from all assemblies were then merged using cd-hit-est (cd-hit v4.6.1) [44,45], with the parameters -c 0.98 -n 8 -r 1 -G 1 -g 1 -b 20 -s 0.0 -aL 0.0 -aS 0.5. Final assembled VSG sequences were all checked against NCBI’s nr/nt database using BLASTn.

Once reference sequences were determined, quantification was performed as described previously [28]. Noise (VSGs measured below the limit of detection, 0.01%) and contamination (the starting VSG, 427–2) were removed. The relative abundance of each remaining expressed VSG was then calculated using its measured FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads). To evaluate donor selection with respect to genomic position, each of these expressed VSGs was then compared to the Lister427 VSGnome database (http://129.85.245.250/index.html). Assembled VSG sequences, when compared to the most similar 427 VSG, were identified as the 427 VSG when they had either 100% identity over >99% of the length of the assembled ORF or >99% identity over 100% of the assembled ORF. Otherwise, assembled VSGs were referred to as variants (“var” in Fig 5) of the most similar Lister427 VSG. These data were then used to create a heatmap using heatmap.2 from the gplots package in R (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/gplots/gplots.pdf).). The VSG-seq data have been deposited in the SRA database under the project number SRP062141.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Berriman M, Ghedin E, Hertz-Fowler C, Blandin G, Renauld H, Bartholomeu DC, et al. The genome of the African trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei. Science (New York, NY). 2005;309 : 416–422.

2. Cross GAM, Kim H-S, Wickstead B. Capturing the variant surface glycoprotein repertoire (the VSGnome) of Trypanosoma brucei Lister 427. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 2014;195 : 59–73. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2014.06.004 24992042

3. Overath P, Engstler M. Endocytosis, membrane recycling and sorting of GPI-anchored proteins: Trypanosoma brucei as a model system. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53 : 735–744. 15255888

4. Barry JD, McCulloch R. Antigenic variation in trypanosomes: enhanced phenotypic variation in a eukaryotic parasite. Adv Parasitol. 2001;49 : 1–70. 11461029

5. Cross GA. Identification, purification and properties of clone-specific glycoprotein antigens constituting the surface coat of Trypanosoma brucei. Parasitology. 1975;71 : 393–417. 645

6. Wickstead B, Ersfeld K, Gull K. The small chromosomes of Trypanosoma brucei involved in antigenic variation are constructed around repetitive palindromes. Genome Res. 2004;14 : 1014–1024. 15173109

7. Hertz-Fowler C, Figueiredo LM, Quail MA, Becker M, Jackson A, Bason N, et al. Telomeric expression sites are highly conserved in Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS ONE. 2008;3: e3527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003527 18953401

8. Michels PA, Van der Ploeg LH, Liu AY, Borst P. The inactivation and reactivation of an expression-linked gene copy for a variant surface glycoprotein in Trypanosoma brucei. EMBO J. 1984;3 : 1345–1351. 6086319

9. Pays E, Guyaux M, Aerts D, Van Meirvenne N, Steinert M. Telomeric reciprocal recombination as a possible mechanism for antigenic variation in trypanosomes. Nature. 1985;316 : 562–564. 2412122

10. De Lange T, Kooter JM, Michels PA, Borst P. Telomere conversion in trypanosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11 : 8149–8165. 6324075

11. Robinson NP, Burman N, Melville SE, Barry JD. Predominance of duplicative VSG gene conversion in antigenic variation in African trypanosomes. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19 : 5839–5846. 10454531

12. Boothroyd CE, Dreesen O, Leonova T, Ly KI, Figueiredo LM, Cross GAM, et al. A yeast-endonuclease-generated DNA break induces antigenic switching in Trypanosoma brucei. Nature. 2009;459 : 278–281. doi: 10.1038/nature07982 19369939

13. Hovel-Miner GA, Boothroyd CE, Mugnier M, Dreesen O, Cross GAM, Papavasiliou FN. Telomere length affects the frequency and mechanism of antigenic variation in Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8: e1002900. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002900 22952449

14. Glover L, Alsford S, Horn D. DNA break site at fragile subtelomeres determines probability and mechanism of antigenic variation in African trypanosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9: e1003260. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003260 23555264

15. Morrison LJ, Majiwa P, Read AF, Barry JD. Probabilistic order in antigenic variation of Trypanosoma brucei. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35 : 961–972. 16000200

16. Aguilera A, García-Muse T. Causes of genome instability. Annu Rev Genet. 2013;47 : 1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133232 23909437

17. Liu AY, Van der Ploeg LH, Rijsewijk FA, Borst P. The transposition unit of variant surface glycoprotein gene 118 of Trypanosoma brucei. Presence of repeated elements at its border and absence of promoter-associated sequences. J Mol Biol. 1983;167 : 57–75. 6306255

18. Campbell DA, van Bree MP, Boothroyd JC. The 5'-limit of transposition and upstream barren region of a trypanosome VSG gene: tandem 76 base-pair repeats flanking (TAA)90. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12 : 2759–2774. 6324125

19. Aline R, MacDonald G, Brown E, Allison J, Myler P, Rothwell V, et al. (TAA)n within sequences flanking several intrachromosomal variant surface glycoprotein genes in Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13 : 3161–3177. 2987874

20. McCulloch R, Rudenko G, Borst P. Gene conversions mediating antigenic variation in Trypanosoma brucei can occur in variant surface glycoprotein expression sites lacking 70-base-pair repeat sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17 : 833–843. 9001237

21. Carnes J, Anupama A, Balmer O, Jackson A, Lewis M, Brown R, et al. Genome and phylogenetic analyses of Trypanosoma evansi reveal extensive similarity to T. brucei and multiple independent origins for dyskinetoplasty. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9: e3404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003404 25568942

22. Schwede A, Macleod OJS, MacGregor P, Carrington M. How Does the VSG Coat of Bloodstream Form African Trypanosomes Interact with External Proteins? PLoS Pathog. 2015;11: e1005259. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005259 26719972

23. Kim H-S, Cross GAM. TOPO3alpha influences antigenic variation by monitoring expression-site-associated VSG switching in Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6: e1000992. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000992 20628569

24. Wickstead B, Ersfeld K, Gull K. Targeting of a tetracycline-inducible expression system to the transcriptionally silent minichromosomes of Trypanosoma brucei. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 2002;125 : 211–216. 12467990

25. Davies KP, Carruthers VB, Cross GA. Manipulation of the vsg co-transposed region increases expression-site switching in Trypanosoma brucei. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 1997;86 : 163–177. 9200123

26. Longhese MP, Mantiero D, Clerici M. The cellular response to chromosome breakage. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60 : 1099–1108. 16689788

27. Cann KL, Hicks GG. Regulation of the cellular DNA double-strand break response. Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;85 : 663–674. 18059525

28. Mugnier MR, Cross GAM, Papavasiliou FN. The in vivo dynamics of antigenic variation in Trypanosoma brucei. Science (New York, NY). 2015;347 : 1470–1473.

29. Borst P, Ulbert S. Control of VSG gene expression sites. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 2001;114 : 17–27. 11356510

30. Horn D. Antigenic variation in African trypanosomes. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 2014;195 : 123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2014.05.001 24859277

31. Van der Ploeg LH, Valerio D, De Lange T, Bernards A, Borst P, Grosveld FG. An analysis of cosmid clones of nuclear DNA from Trypanosoma brucei shows that the genes for variant surface glycoproteins are clustered in the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10 : 5905–5923. 6292859

32. Pays E, Nolan DP. Expression and function of surface proteins in Trypanosoma brucei. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 1998;91 : 3–36. 9574923

33. Borst P, Bitter W, Blundell PA, Chaves I, Cross M, Gerrits H, et al. Control of VSG gene expression sites in Trypanosoma brucei. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 1998;91 : 67–76. 9574926

34. Ohshima K, Kang S, Larson JE, Wells RD. TTA.TAA triplet repeats in plasmids form a non-H bonded structure. J Biol Chem. 1996;271 : 16784–16791. 8663378

35. Deitsch KW, Lukehart SA, Stringer JR. Common strategies for antigenic variation by bacterial, fungal and protozoan pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol. Nature Publishing Group; 2009;7 : 493–503.

36. Fujitani Y, Yamamoto K, Kobayashi I. Dependence of frequency of homologous recombination on the homology length. Genetics. 1995;140 : 797–809. 7498755

37. Navarro M, Gull K. A pol I transcriptional body associated with VSG mono-allelic expression in Trypanosoma brucei. Nature. 2001;414 : 759–763. 11742402

38. Wirtz E, Leal S, Ochatt C, Cross GA. A tightly regulated inducible expression system for conditional gene knock-outs and dominant-negative genetics in Trypanosoma brucei. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 1999;99 : 89–101. 10215027

39. Burkard G, Fragoso CM, Roditi I. Highly efficient stable transformation of bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 2007;153 : 220–223. 17408766

40. Hirumi H, Hirumi K. Axenic culture of African trypanosome bloodstream forms. Parasitol Today (Regul Ed). 1994;10 : 80–84.

41. Pozarowski P, Darzynkiewicz Z. Analysis of cell cycle by flow cytometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;281 : 301–311. 15220539

42. Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29 : 644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883 21572440

43. Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10 : 421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 20003500

44. Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22 : 1658–1659. 16731699

45. Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28 : 3150–3152. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565 23060610

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2016 Číslo 5- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Animal Models Are Valid to Uncover Disease Mechanisms

- Hypothalamic Leptin Resistance: From BBB to BBSome

- Spermatogenesis Studies Reveal a Distinct Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay (NMD) Mechanism for mRNAs with Long 3′UTRs

- Parental Origin of Interstitial Duplications at 15q11.2-q13.3 in Schizophrenia and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

- Antimicrobial Functions of Lactoferrin Promote Genetic Conflicts in Ancient Primates and Modern Humans

- Genomic Imprinting: A New Epigenetic Perspective of Sleep Regulation

- Embryonic Lethality of Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier 1 Deficient Mouse Can Be Rescued by a Ketogenic Diet

- Bayesian Inference of Reticulate Phylogenies under the Multispecies Network Coalescent

- A Conserved DNA Repeat Promotes Selection of a Diverse Repertoire of Surface Antigens from the Genomic Archive

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Animal Models Are Valid to Uncover Disease Mechanisms

- Embryonic Lethality of Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier 1 Deficient Mouse Can Be Rescued by a Ketogenic Diet

- Hypothalamic Leptin Resistance: From BBB to BBSome

- Parental Origin of Interstitial Duplications at 15q11.2-q13.3 in Schizophrenia and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy