-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Characterization of Novel Antimalarial Compound ACT-451840: Preclinical Assessment of Activity and Dose–Efficacy Modeling

Sergio Wittlin and colleagues report in vivo and in vitro modelling of antimalarial activity and dose-efficacy of a new drug candidate.

Published in the journal: Characterization of Novel Antimalarial Compound ACT-451840: Preclinical Assessment of Activity and Dose–Efficacy Modeling. PLoS Med 13(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002138

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002138Summary

Sergio Wittlin and colleagues report in vivo and in vitro modelling of antimalarial activity and dose-efficacy of a new drug candidate.

Introduction

Malaria caused 438,000 deaths worldwide in 2015, of which 70% were in children under the age of 5 y [1]. Between 2000 and 2015, strategies for malaria control and eradication reduced the incidence of malaria by 48% in the WHO African Region. The upscaled interventions consisted of increased accessibility to long-lasting insecticidal bed nets, protection of the population at risk by indoor residual spraying, and increased access to rapid diagnostic tests and artemisinin-based combination therapies. However, with the detection of parasite resistance to artemisinin, the core compound of artemisinin-based combination therapies, in five countries of Southeast Asia, the availability of efficacious combination therapies is under threat [1]. Additionally, not a single new chemical class of antimalarials has been registered since 1996 [2], and the current global portfolio of antimalarial compounds in late clinical development relies largely on novel combinations of existing drugs, not novel compounds [3]. These elements highlight the critical and urgent need for new drugs to treat malaria.

In this search, ACT-213615, a compound from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (ACT) with a mode of action distinct from that of all registered antimalarials, was recently described [4]. The compound was discovered in a phenotypic screen and showed potent and fast-acting activity in in vitro assays against all asexual erythrocytic stages of P. falciparum (i.e., rings, trophozoites, and schizonts). Further investigations regarding the mode of action established an interaction of this compound class with P. falciparum multidrug resistance protein-1 (PfMDR1) [5,6].

The present work illustrates a novel antimalarial drug development process, in that the studies were performed in partnership with research groups around the globe from industry and academia. MMV (Geneva, Switzerland), a new model of not-for-profit public–private partnership, was instrumental in the establishment of those collaborations and has transformed the field of malaria therapy by providing guidance to the development of new drugs. The strategy of MMV is the prioritization of new treatments that provide a single exposure radical cure and prophylaxis (SERCaP). Prevention of transmission, prevention of relapse following infection by P. vivax and Plasmodium ovale, and significant post-treatment prophylaxis are the key properties sought for future medicines, as described in MMV's new target compound profiles (TCP) [7]. Achievement of the SERCaP objectives might require the combination of several compounds (two to three), each with specific profiles and properties. Ideally, a new malaria treatment requires at least one molecule capable of replacing the fast-acting artemisinin component described as target compound profile 1 (TCP1). Suitability as a TCP1 candidate can be assessed in experiments (A) determining potency in both P. falciparum and P. vivax strains, (B) including strains already resistant to other antimalarials including artemisinins, (C) measuring log kill in vitro in comparison to existing antimalarials, and (D) establishing efficacy in an appropriate in vivo animal model. The TCP2-type molecules would be used as long duration combination partners that complete the clearance of the blood stage parasites not eliminated by TCP1 molecules. Understanding the PK profile of a compound will determine its suitability as a TCP2 candidate. Molecules with a potential for blocking transmission should target mature gametocytes (TCP3b) and also antagonize other nondividing parasites such as hypnozoites (TCP3a). Finally, molecules blocking the infection of the host liver by sporozoites, or killing liver schizonts, will cover the need for TCP4 drugs [8].

Leveraging these TCPs, the continuous drug discovery effort in the new class of potent antimalarials around ACT-213615 led to the selection of ACT-451840. In the present study, the characterization of ACT-451840 is used to illustrate the new drug development paradigm in which new technical expertise and model-based methodologies are being used to improve the subsequent clinical development phases and reduce attrition rates. Firstly, the experiments to evaluate the biological potential of ACT-451840 in P. falciparum in vitro assays against all asexual erythrocytic stages and against a panel of clinical isolates including P. vivax are shown. Additionally, key PD properties of the compound are described, including its precise rapidity of action and parasite log kill, efficacy in two pharmacological murine models with both human and mouse malaria parasites, and in vitro inhibition of gamete formation from the male gametocyte stage, resulting in transmission blocking in mosquitoes. Finally, the modeling of efficacy in murine models defined either as antimalarial activity, or as survival, in relation to AUC, Cmax, and time over a threshold concentration, was used to determine the dose–efficacy relationship of ACT-451840. The subsequent prediction of the human efficacious exposure was used to guide the dose selection for the initiation of the POC study. The goal of the here described preclinical assessment of activity and dose–efficacy modeling of ACT-451840 was to lay the groundwork for the next phases of clinical development.

Methods

Ethics Statement

Animal experiments performed at Actelion Pharmaceuticals and at the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH), or performed at GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) were approved, respectively, by the Swiss Cantonal Authorities and by the Diseases of the Developing World Ethical Committee on Animal Research. The animal studies carried out at GSK were in accordance with European Directive 2010/63/EU and the GSK Policy on the Care, Welfare and Treatment of Animals and were accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Animal Laboratory Care for the ones performed at Diseases of the Developing World Laboratory Animal Science facilities. The results from the animal experiments are reported as per ARRIVE guidelines (S1 Checklist). The human biological samples were sourced ethically, and their research use was in accord with the terms of the informed consents. Ethical approval for the field studies were obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Territory Department of Health & Families and Menzies School of Health Research, Darwin, Australia (HREC 2010–1396), and the Eijkman Institute Research Ethics Commission, Jakarta, Indonesia (EIREC 47).

Synthesis of ACT-451840

The synthesis of ACT-451840 developed at Actelion Pharmaceuticals (Allschwil, Switzerland) is shown in the supporting material (S1 Fig). ACT-451840 is patented (WO 2011/083413).

In Vitro Antimalarial Activity against P. falciparum

The in vitro antimalarial activity of ACT-451840 was measured at the Swiss TPH (Basel, Switzerland) using the [3H]-hypoxanthine incorporation assay [9]. Results were expressed as the concentration resulting in 50% inhibition (IC50). In vitro time-, stage-, and concentration-dependent effects were assessed using pyrimethamine as a stage-specific and slow-acting control, as described elsewhere [10].

In Vitro Antimalarial Activity against P. falciparum Artemisinin-Resistant Strains

Ring-stage survival assays (RSA0-3h) were carried out at Columbia University Medical Center (New York, United States) as previously described [11,12]. Parasite cultures were synchronized using 5% sorbitol (Sigma-Aldrich), and schizonts were incubated in RPMI-1640 containing 15 units/ml sodium heparin for 15 min at 37°C to disrupt agglutinated erythrocytes. These schizonts were concentrated over a gradient of 75% Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich), washed once in RPMI-1640, and incubated for 3 h with fresh erythrocytes to allow time for merozoite invasion. Cultures were then subjected again to sorbitol treatment to eliminate remaining schizonts. The 0–3 h postinvasion rings were adjusted to 1% parasitemia and 2% hematocrit in 1 mL volumes (in 48-well plates) and exposed to a range of ACT-451840 drug concentration (700–35 nM) or 0.1% DMSO for 6 h. Duplicate wells were established for each parasite line ± drug concentration. One-mL cultures were then transferred to 15-mL conical tubes, centrifuged at 800xg for 5 min to pellet the cells, and the supernatants carefully removed. As a washing step to remove drug, 10 mL culture medium were added to each tube, and the cells were resuspended, centrifuged, and the medium was aspirated. Fresh medium without drug was then added to cultures, which were returned to standard culture conditions for 66 h. A media change was performed, and parasite viability was assessed by flow cytometry at 96 h. Stained parasites were detected using a BD Accuri 6 Flow Cytometer and analyzed using FlowJo Software. IC50 values were determined by nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism 6.0. For statistical analyses, Student’s t tests were performed, and significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ex Vivo Drug Susceptibility against Multidrug-Resistant P. falciparum and P. vivax Clinical Isolates

Ex vivo drug susceptibility testing in P. falciparum and P. vivax (often a mix of rings, trophozoites, and schizonts) was assessed in clinical isolates at the Timika Research Facility (Papua, Indonesia), an area with confirmed high levels of multidrug resistance to chloroquine, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, and amodiaquine in both species [13–15]. Thick blood films made from each well were stained with 5% Giemsa solution for 30 min and examined microscopically. The number of schizonts per 200 asexual-stage parasites was determined for each drug concentration and normalized to the control well. The dose–response data were analyzed using nonlinear regression analysis (WinNonLin 4.1, Pharsight Corporation), and the concentrations resulting in 50% inhibition (IC50) were derived using an inhibitory sigmoid Emax model. Ex vivo IC50 data were only used from predicted curves for which the E0 and Emax were within 15% of 1 and 100, respectively.

In Vitro Parasite Reduction Ratio

In vitro PRR testing was conducted at GSK (Tres Cantos, Madrid, Spain) as previously described [16]. The assay used the limiting dilution technique to quantify the number of parasites that remained viable after drug treatment. P. falciparum strain 3D7 (MR4) was treated with drug concentration corresponding to 10 x IC50. Conditions of parasites exposed to treatment were identical to those used at GSK in the IC50 determination (2% hematocrit, 0.5% parasitemia). Parasites were treated for 120 h. Drug in culture medium was renewed daily over the entire treatment period. Parasite samples were collected from the treated culture every 24 h (24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h time points); drug was washed out of the sample, and parasites were cultured drug-free in 96-well plates by adding fresh erythrocytes and culture medium. To quantify the number of viable parasites after treatment, 3-fold serial dilutions were used with the above mentioned samples after removing the drug. Four independent serial dilutions were performed with each sample to correct experimental variations. The number of viable parasites was determined after 21 and 28 d by counting the number of wells with growth using [3H]-hypoxanthine incorporation. The number of viable parasites was back-calculated by using the formula Xn-1 where n is the number of wells able to render growth and X the dilution factor (when n = 0, number of viable parasites is estimated as zero) [16]. The PRR, defined as the logarithm to base 10 of the number of parasites the drug can kill in one parasite life cycle and indicating the killing rate of the compound investigated, was calculated as the decrease in viable parasites over 48 h. A lag phase was considered to occur for as long as drug treatment did not produce the maximal rate of killing, and this period of time was excluded for PRR calculation. The parasite clearance time to kill 99.9% of the initial population was determined using a regression calculated on the log-linear phase of the parasite reduction, taking into account the lag phase.

In Vitro Antimalarial Activity against P. berghei

In vitro (ex vivo) activity against the mouse malaria parasite P. berghei was measured at the Swiss TPH as described elsewhere [17], with the following modifications: heparinised blood of P. berghei infected and uninfected control female NMRI mice (final hematocrit of 2.5%) was used and exposed to compounds for 16 h followed by 8 h of [3H]-hypoxanthine incorporation.

In Vivo Antimalarial Efficacy Studies

In vivo efficacy against P. berghei was conducted at the Swiss TPH as previously described [18], with the modification that female NMRI mice from Harlan (Horst, The Netherlands) (n = 3) were infected with a GFP-transfected P. berghei ANKA strain (kindly donated by A. P. Waters and C. J. Janse, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands) and parasitemia was determined using standard flow cytometry techniques. ACT-451840 was dissolved or suspended in corn oil before dosing and administered 24 h after infection (single-dose regimen) or 24, 48, and 72 h after infection (triple-dose regimen). With the single-dose regimen, blood was collected on Day 3 (72 h after infection). Samples for the triple-dose regimens were collected on Day 4 (96 h after infection). Antimalarial activity was calculated as the difference between the mean percent parasitemia for the control and treated groups expressed as a percent relative to the control group, consisting of five mice. Control mice were euthanized on Day 4 in order to prevent death typically occurring on Day 6. For the consistency in PK/PD modeling, Day 5 instead of Day 6 was considered the day of death, because treated animals were always euthanized one day before their natural death for animal welfare reasons. Animals were considered cured if there were no detectable parasites on Day 30 post-infection. To confirm the reliability of this assumption, blood from the surviving mice in curative experiments was inoculated into uninfected mice, and no parasitemia developed in these mice even after 30 d [19]. The antimalarial efficacy is defined either as antimalarial activity or as survival: the two readouts of the P. berghei murine model.

In vivo efficacy against P. falciparum was conducted at GSK according to the standard assay previously described [20,21]. Female NODscidIL2Rγnull mice were engrafted with human erythrocytes and infected with the isolate P. falciparum PfNF540230/N3, a strain developed at GSK for growth in engrafted mice. At Day 3 after infection, chloroquine (at 2 or 5 mg/kg) or ACT-451840 (3, 10, 30, or 100 mg/kg; n = 3 mice per dose, formulated in corn oil) were dosed via oral gavage once a day for four consecutive days (quadruple-dose regimen). Blood samples were collected on Days 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 (n = 3 per time point) for parasitemia measurement by flow cytometry. Similarly, blood samples were collected at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h after a single administration of 4.7 mg/kg of ACT-451840 to a parallel group of three P. falciparum-infected mice for PK parameters determination. Results are expressed exclusively as antimalarial activity in the P. falciparum murine model.

P. falciparum Dual Gamete Formation Assay (Pf DGFA)

Mature P. falciparum NF54 gametocytes were cultured at Imperial College London (London, United Kingdom), as previously described [22]. The cultures, which displayed between 0.2 and 0.4% exflagellation centers as a percentage of the total blood cell population, were then taken and divided into 96-well plates containing ACT-451840 in dose response (range 0.84 nM–20 μM). Final DMSO concentration in the assay did not exceed 0.25%. Plates were incubated for 24 h in the presence of ACT-451840 before male and female gametocyte viability was assessed by stimulating gamete formation by temperature decrease from 37°C to ~22°C and the addition of the gametocyte activating factor xanthurenic acid (5 μM). Male gamete formation was quantified by computer-aided automated identification and counting of exflagellation centers. Female gamete formation was visualized by live immunofluorescence with a Cy3-conjugated antibody specific for Pfs25—a female gamete expressed surface protein. Gamete formation was expressed as a percent inhibition, taking into consideration DMSO-negative control wells and 10 μM methylene blue-positive control wells, methylene blue being a potent inhibitor of the functional viability of male and female stage V gametocytes [22]. IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism version 6 using the logarithmic versus normalized response (variable slope) function (Graphpad Software, San Diego, US).

Oocyst Density Evaluation by Standard Membrane Feeding Assay

ACT-451840 was tested in the standard membrane feeding assay at TropIQ (Nijmegen, The Netherlands) in two modes, as previously described [23]. In the direct mode, the compound was directly added to a bloodmeal containing mature stage V gametocytes that was fed to Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes. In the indirect mode, mature stage V gametocytes were pre-exposed for 24 h to a serial dilution of compound (10−5 to 10−9 M final concentration) prior to mosquito feeding. Gametocytes were adapted to a hematocrit of 50% in full serum and fed to A. stephensi mosquitoes. Seven days after the bloodmeal, the number of oocysts in the midgut was determined by microscopy for both modes. ACT-451840 was tested in duplicate in a 9-point dose response series (1010–106 M in 0.5 log dilutions). Vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) and positive control (10 μM dihydroartemisinin) were included. Twenty mosquitoes were dissected per sample, and oocyst load was analyzed per mosquito. All assays passed the quality control criterion of >50% infected mosquitoes in the control cages.

Pharmacokinetic Studies

Female NMRI mice were purchased from Harlan (Horst, The Netherlands) by Actelion Pharmaceuticals. ACT-451840 was formulated as a solution in corn oil and dosed via oral gavage at 10, 100, and 300 mg/kg. Serial blood samples were collected at 0.5, 2, 4, and 8 h after dosing from two mice and after 1, 3, 6, and 24 h from two other mice, creating composite PK profiles from, in total, four mice per dose. Blood samples were analyzed using liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) after protein precipitation. PK parameters were estimated using non-compartmental analysis from the composite profiles.

Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling

A single compartment PK model with saturable absorption was obtained using naïve pooling to fit simultaneously the observed blood concentration time data from the PK studies done at a dose of 10, 100, and 300 mg/kg, as described above. Using this model, blood concentration time profiles were predicted for all dosing regimens used in the mouse antimalarial efficacy studies. Cmax, AUC, and time above a threshold concentration were subsequently calculated using non-compartmental analysis. PD modeling was done using an Emax model using Cmax, AUC, or time above a threshold concentration versus survival or antimalarial activity. All modeling and PK analyses were done using Phoenix Winonlin 6.3 (Cetara, Princeton, US).

Results

Characterization of ACT-451840 In Vitro and In Vivo against Asexual Blood Stage: Biological Activity against Relevant Parasites

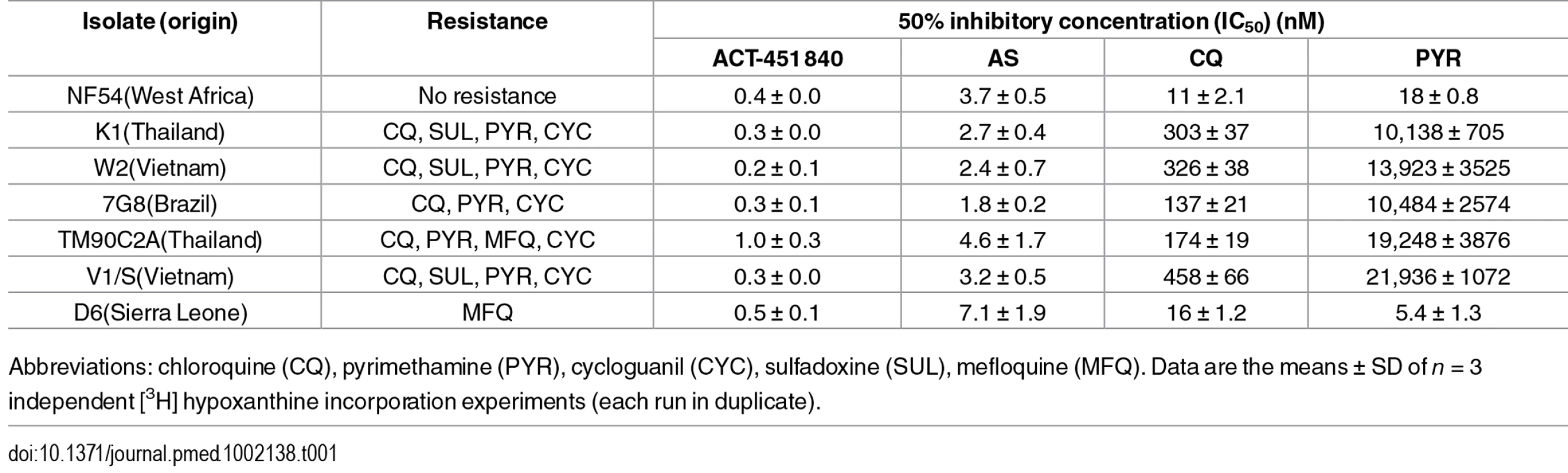

Antimalarial asexual blood-stage activity of ACT-451840 was evaluated against a panel of P. falciparum culture adapted isolates by a [3H] hypoxanthine incorporation assay (Table 1). ACT-451840 showed a low nanomolar activity against the drug-sensitive P. falciparum NF54 strain (mean IC50 = 0.4 ± 0.0 nM; IC90 = 0.6 ± 0.0 nM; IC99 = 1.2 ± 0.0 nM, n ≥ 3; ± SD) and was almost equally active against a number of drug-resistant isolates. The IC50 values of the control compounds, e.g., artesunate, chloroquine, and pyrimethamine, against the NF54 strain were 3.7 ± 0.5 nM, 11 ± 2.1 nM, and 18 ± 0.8 nM, respectively.

Tab. 1. In vitro activity against a panel of resistant and sensitive strains of P. falciparum.

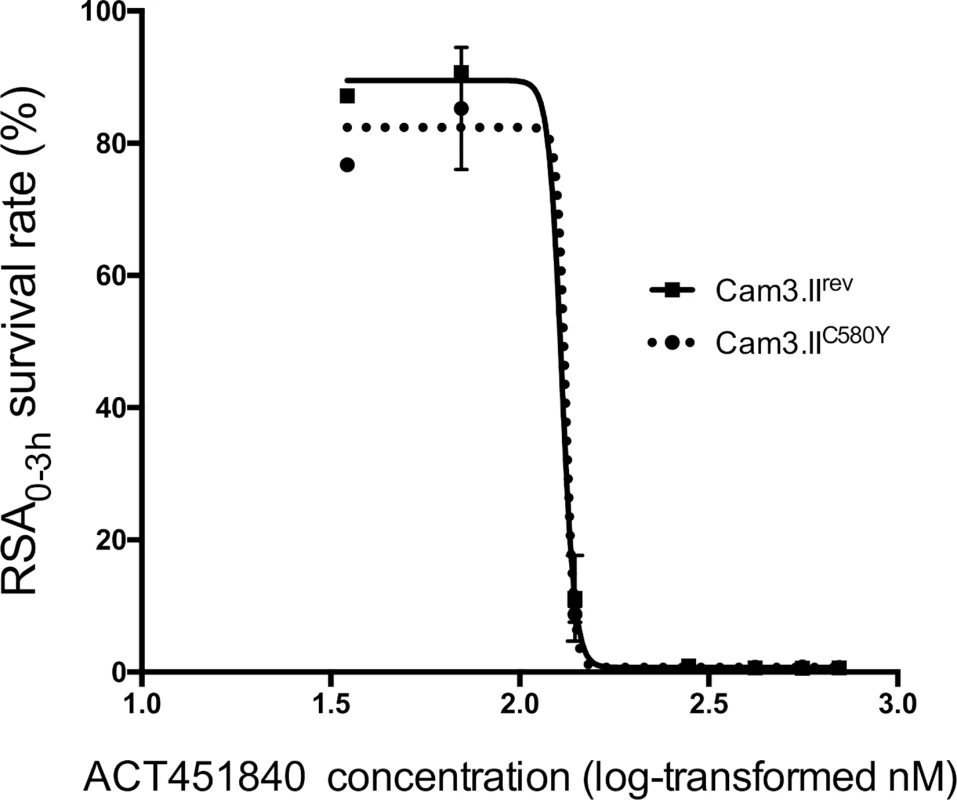

Abbreviations: chloroquine (CQ), pyrimethamine (PYR), cycloguanil (CYC), sulfadoxine (SUL), mefloquine (MFQ). Data are the means ± SD of n = 3 independent [3H] hypoxanthine incorporation experiments (each run in duplicate). Antimalarial asexual blood-stage activity of ACT-451840 was also evaluated against a Cambodian clinical isolate (Cam3.II, which has a K13 R539T mutation) that was gene-edited to the wild-type K13 gene (Cam3.IIrev) and against Cam3.IIC580Y, a gene-edited line that is artemisinin resistant and encodes the C580Y mutation in the K13 gene [11,12]. The mutation C580Y, conferring resistance to artemisinin, was found to not alter parasite susceptibility to ACT-451840, mefloquine, or artesunate in conventional 72-h dose–response assays that determine IC50 growth inhibition values on both the Cam3.II and V1/S backgrounds (S1 Text). Additionally, both Cam3.II lines were subjected to the recently developed ring-stage survival assay (RSA0-3h), in which parasites were exposed for a 6-h pulse to a range of drug concentration (35–700 nM), and parasite survival was assessed 66 h later [11,12]. No difference in survival rates was observed between the parasite harboring a wild-type K13 allele or the C580Y mutation (Fig 1), confirming that ACT-451840 is fully efficacious against artemisinin-resistant parasites. In contrast, the C580Y strain showed the expected grade of resistance versus the exposure to 700 nM dihydroartemisinin [11,12].

Fig. 1. K13 propeller mutation C580Y confers no cross-resistance to ACT-451840 in ring-stage survival assays (RSA0-3h).

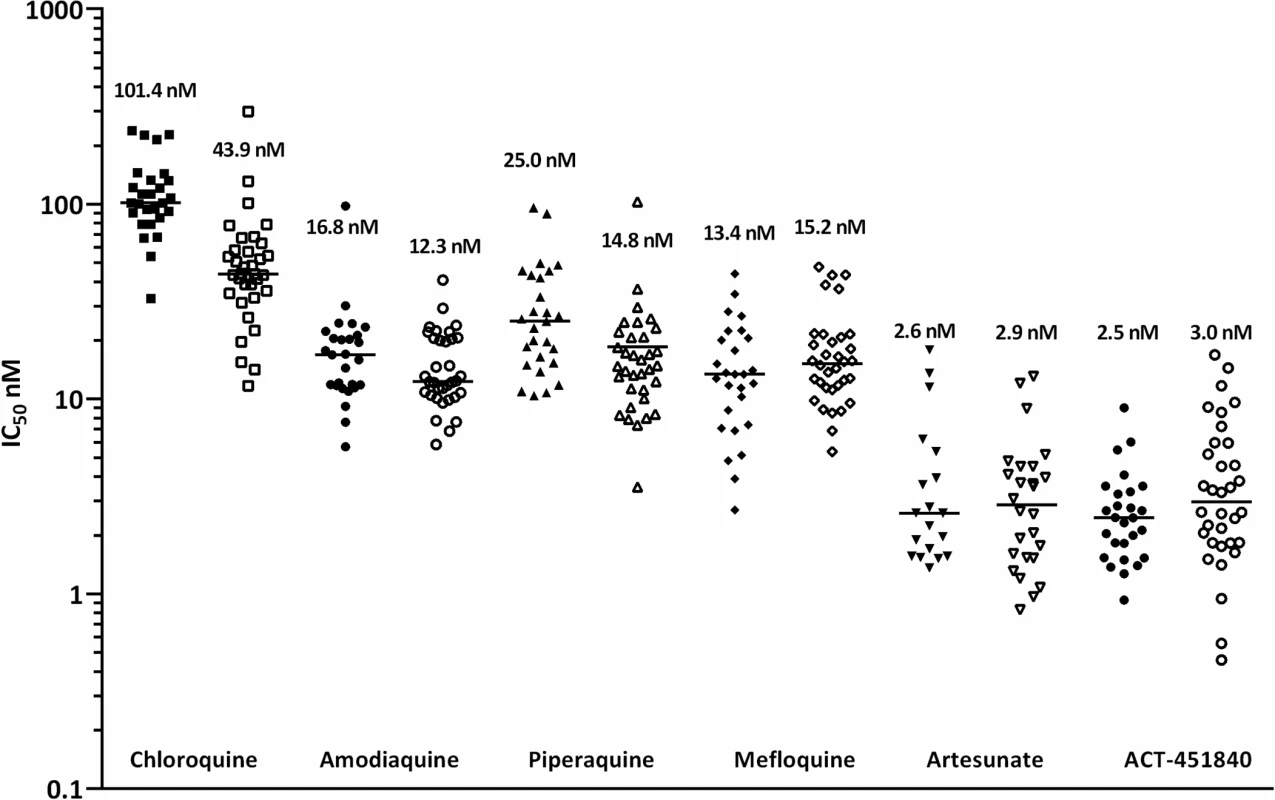

Graph shows mean ± standard error (SE) ring-stage survival values in the RSA0-3h. At least two biological replicates were performed per line, each consisting of two technical replicates Cam3.IIC580Y (dotted line) and Cam3.IIrev (solid line). Abbreviation: ring-stage survival assay (RSA0-3h). In ex vivo assays against a range of clinical isolates collected from patients with malaria from Papua, Indonesia, a region where multidrug-resistant malaria is endemic, ACT-451840 was as potent as artesunate against both P. falciparum (median IC50 = 2.5 [Range 0.9–9.0] nM, n = 27) and P. vivax (median IC50 = 3.0 [Range 0.5–16.8] nM, n = 34) (Fig 2). The IC50 value of ACT-451840 against the murine malaria parasite P. berghei was 13.5 nM in in vitro ex vivo assays.

Fig. 2. Ex vivo drug susceptibility.

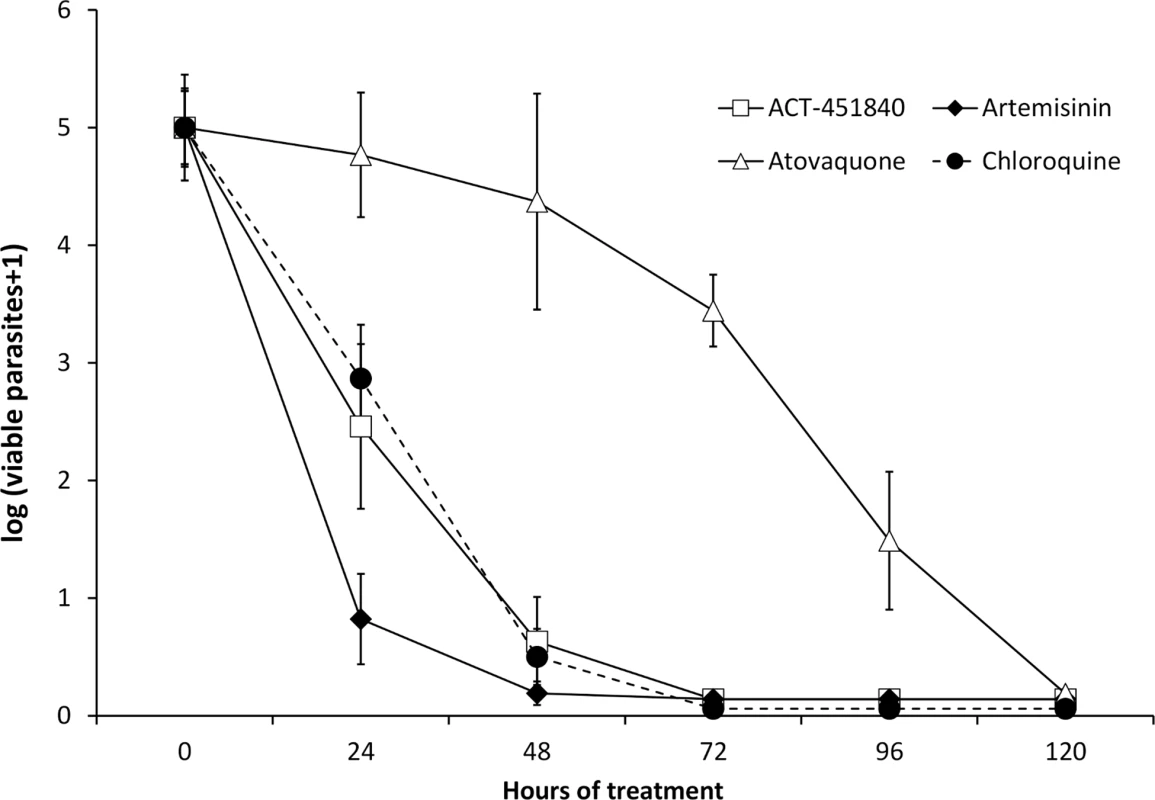

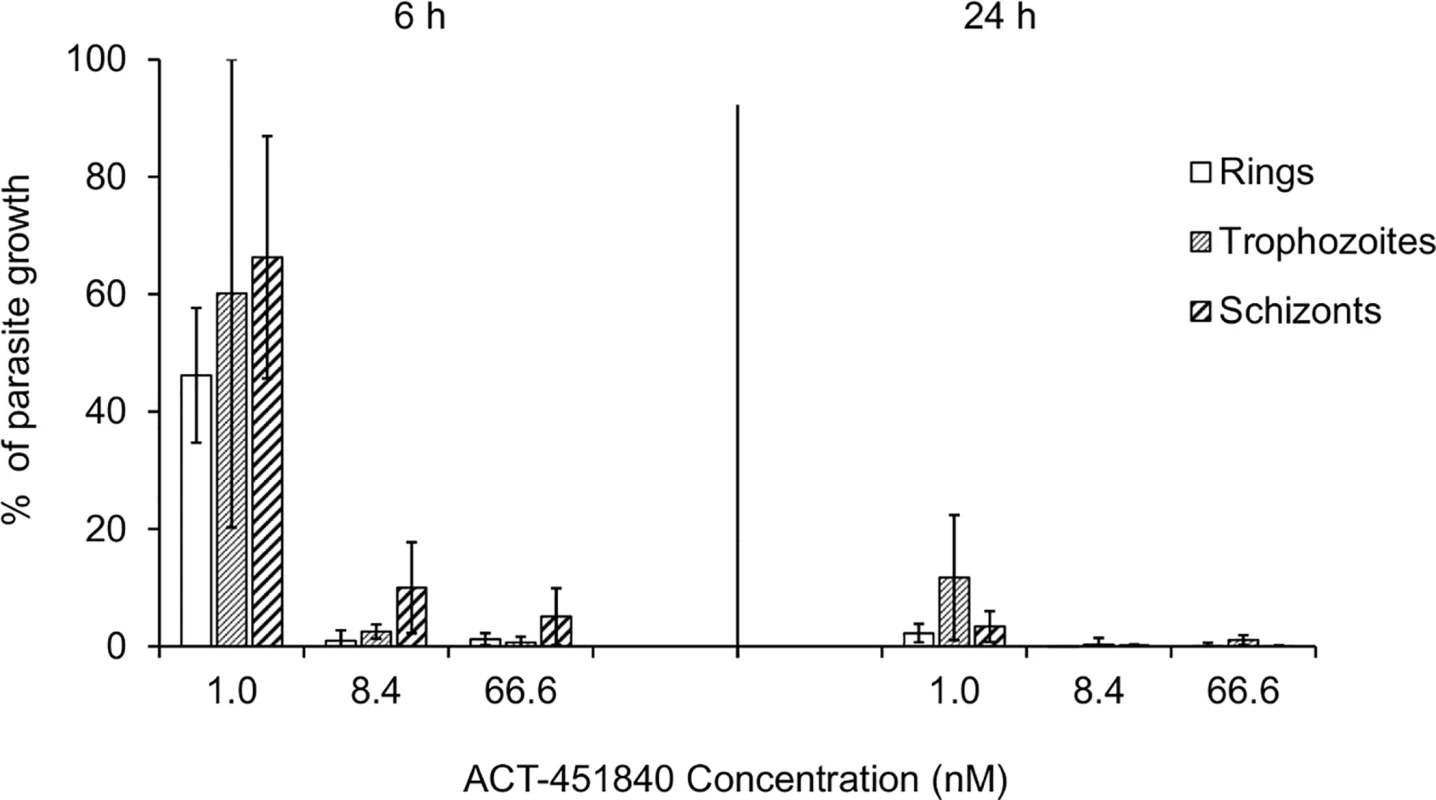

Median 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of standard antimalarials and ACT-451840 in P. falciparum (closed symbols; n = 27) and P. vivax (open symbols; n = 34) clinical isolates. In an in vitro PRR assay [16], ACT-451840 showed a fast parasite killing profile against P. falciparum similar to that of chloroquine (log PRR of 4.4 and 4.5, respectively) without lag phase in the killing curve in contrast to atovaquone (48 h). The parasite clearance time to kill 99.9% of the initial population was 28 h for ACT-451840, similar to that of artemisinin and chloroquine (less than 24 h and 32 h, respectively) (Fig 3). In vitro stage specificity assays [24] with synchronous cultures of P. falciparum NF54 were consistent with this rapid killing rate. ACT-451840 rapidly reduced parasite growth and affected all asexual erythrocytic stages equally in a time - and concentration-dependent manner, similar to artemether (Fig 4) [24].

Fig. 3. Parasite Reduction Ratio.

The number of viable P. falciparum strain 3D7 (MR4) versus treatment time is compared between ACT-451840 and a selection of standard antimalarials (data for the latter was previously reported in reference [24]). Data are the mean ± SD of four independent replicates. Fig. 4. Time-, stage-, and concentration-dependent effects of ACT-451840 on synchronous cultures of P. falciparum NF54 in vitro.

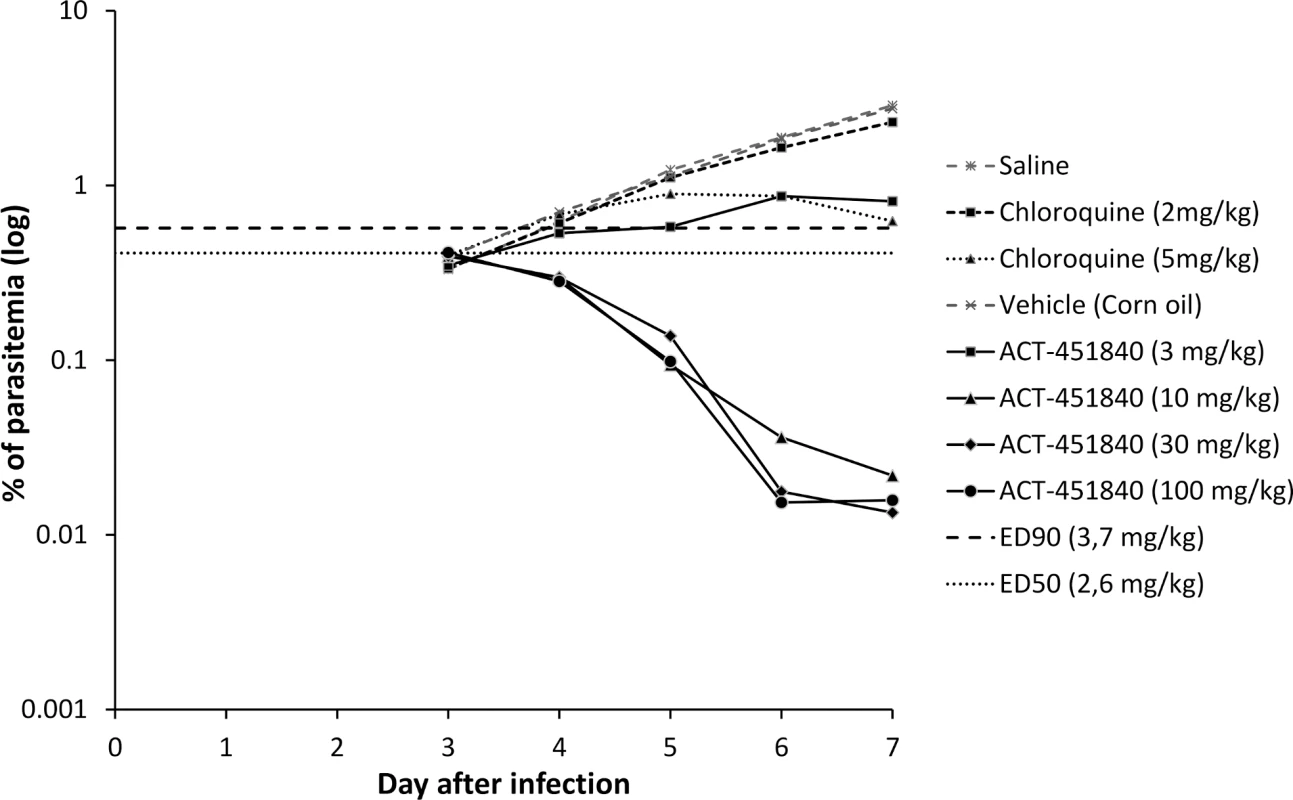

Parasites were exposed to ACT-451840 for 6 or 24 h at the indicated concentration. Results are expressed as the percentage of growth of the respective development stage relative to an untreated control. Each bar represents the mean + SD of three independent experiments. In vivo activity of ACT-451840 was assessed in the P. falciparum mouse model established at GSK (DDW, Tres Cantos, Spain). After an oral quadruple-dose regimen, ACT-451840 had a rapid onset of action and an effective dose, resulting in 90% antimalarial activity (ED90) of 3.7 mg/kg (3.3–4.9 mg/kg), which was comparable to the one of chloroquine (ED90 of 4.9 mg/kg) (Fig 5).

Fig. 5. Therapeutic efficacy against P. falciparum in vivo.

Parasitemia in peripheral blood of mice infected with P. falciparum NF540230/N3 and treated with vehicle, chloroquine, or ACT-451840 once daily for 4 d starting on Day 3 after infection. Data shown are mean parasitemia of three mice/group. Abbreviations: 50% effective dose (ED50), 90% effective dose (ED90). In a P. berghei mouse model, the ED90 after an oral triple-dose regimen of ACT-451840 was 13 mg/kg (11–16 mg/kg) (calculated from the data in S2 Text). This ED90 value was about 4-fold higher than the one observed in the P. falciparum mouse model (ED90 3.7 mg/kg). The difference in in vivo activities correlates with the difference in in vitro ex vivo activities of ACT-451840 against P. berghei (IC50 13.5 nM, see above) and P. falciparum ex vivo (IC50 2.5 nM, clinical isolates; Fig 2). Despite the lower activity of ACT-451840 against P. berghei, 20% and 100% of the infected mice were cured after 100 and 300 mg/kg triple-dose regimen, respectively (Fig 6 and S2 Text). In the same in vivo model, artesunate, the semisynthetic derivative of artemisinin, cured 50% of the mice at 100 mg/kg after a quadruple-dose regimen.

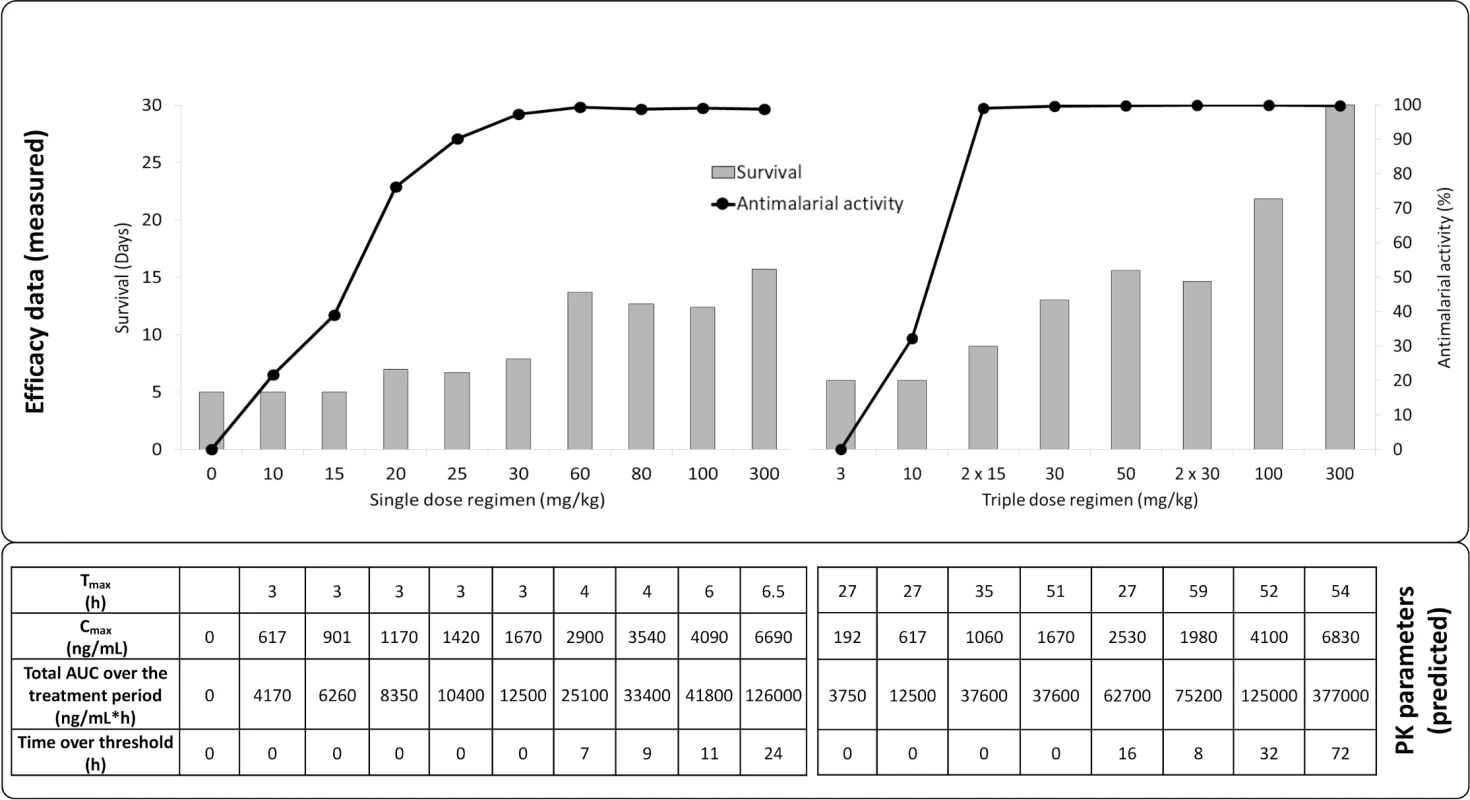

Fig. 6. In vivo efficacy (upper panel) and exposure (lower panel) of ACT-451840 against P. berghei.

Doses were administered once per day except for 2 x 15 mg/kg and 2 x 30 mg/kg, for which mice were dosed twice per day, with the second daily dose 8 h after the first dose. Abbreviations: pharmacokinetic (PK), time to reach the maximum observed plasma concentration (Tmax), maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax), area under the concentration versus time curve (AUC). In summary, ACT-451840 had an IC50 below 10 nM in vitro against a panel of sensitive and resistant strains of P. falciparum and was fully active against recently identified artemisinin-resistant strains. Furthermore, the compound showed ex vivo activity against P. falciparum and P. vivax as well as a single digit mg/kg ED90 in a P. falciparum murine model. In addition, the compound inhibited growth of all asexual blood stages of P. falciparum in vitro, and its in vitro PRR was similar to that of chloroquine. These key properties fully meet the criteria described in TCP1 [8].

Characterization of ACT-451840 In Vitro against Sexual Blood Stage: Potential for Blocking Transmission

Using two bioassays, the effects of ACT-451840 on the functional viability of both male and female mature gametocytes and oocysts of P. falciparum were explored to illustrate how the question of transmission is addressed.

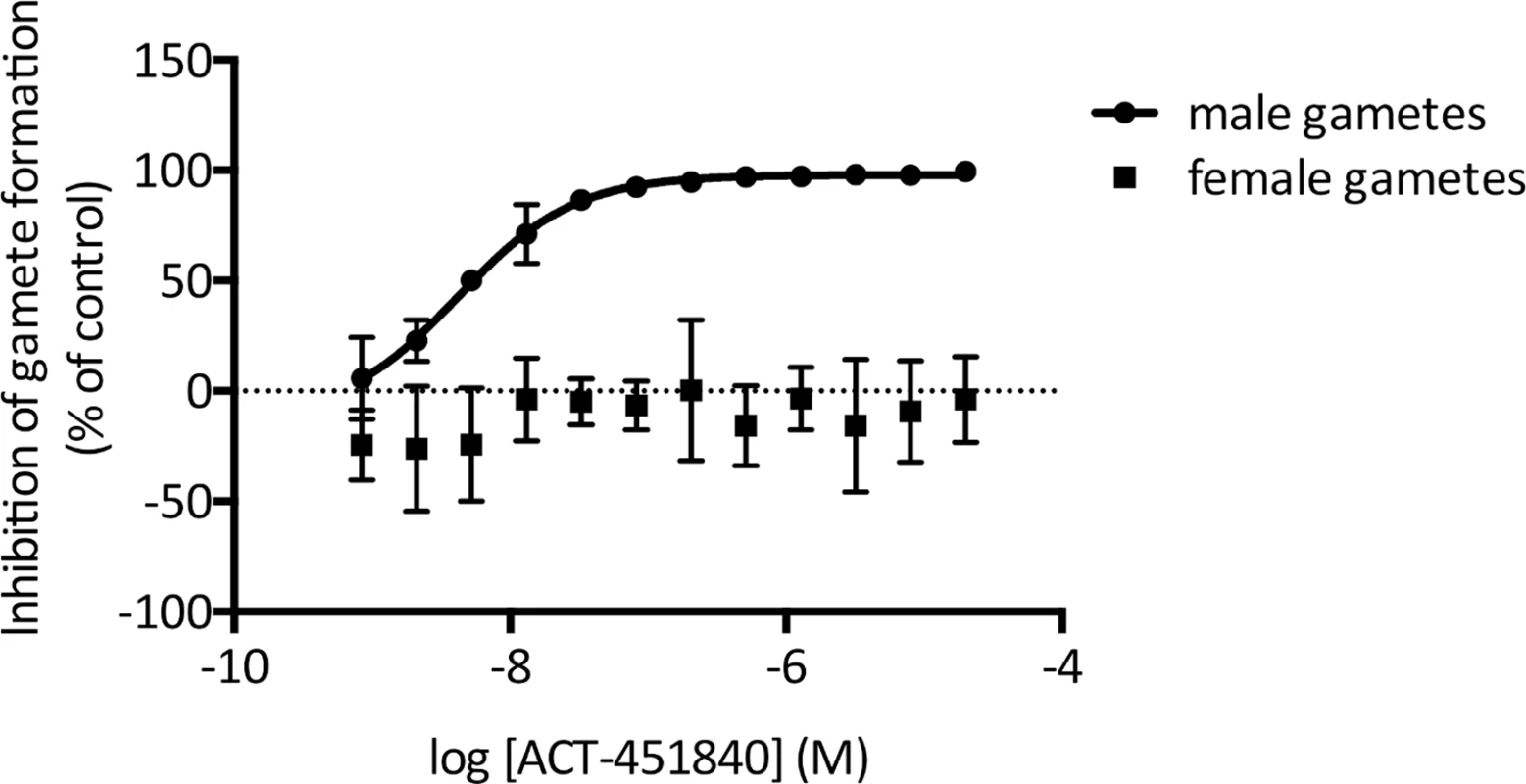

Within the human host blood, P. falciparum gametocytes are classified morphologically into five stages, denoted I–V, whilst P. vivax gametocytes do not show the same morphology. Although the various sexual stages do not cause clinical disease, stage V gametocytes are infective to mosquitoes. These gametocytes are not eliminated by the majority of current antimalarial agents [25] and therefore remain circulating in the human bloodstream for up to 3 wk, well after the disappearance of clinical symptoms of malaria [26]. Gamete formation is a functional readout for the viability of the mature stage V gametocyte [27]. ACT-451840 potently prevented male gamete formation from the gametocyte stage with an IC50 of 5.89 nM ± 1.80 nM (SD), as shown in Fig 7.

Fig. 7. P. falciparum dual gamete formation assay.

The effect of ACT-451840 on the functional viability of P. falciparum male and female gametocytes was tested in vitro in dose response. Male gametocyte viability was reported by microscopic detection of exflagellation centers and yielded an IC50 of 5.89 nM ± 1.80 nM (SD). ACT-451840 showed no activity against female gametocytes, as reported by the surface expression of the female gamete marker pfs-25. Data shown are the mean of four independent replicates. Error bars indicate SE. Interestingly, ACT-451840 had no effect on the functional viability of female gametocytes up to a concentration of 20 μM. Nevertheless, successful transmission requires viable gametocytes of both sexes to be present, as seen similarly with two male-specific molecules, MMV007116 and MMV085203, that demonstrate transmission blocking in a standard membrane feeding assay [27], supporting the potential of ACT-451840 to block malarial transmission.

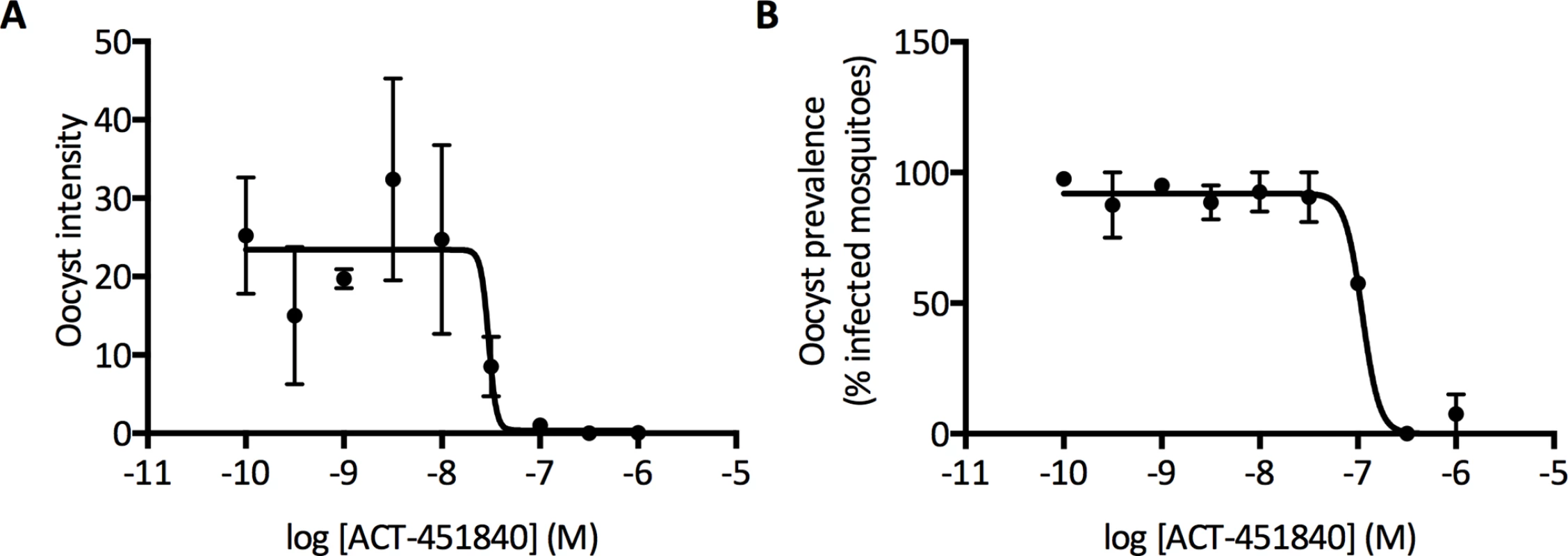

In line with this, ACT-451840 did indeed block transmission when tested in the standard membrane feeding assay. In this assay, parasite cultures containing P. falciparum stage V gametocytes were exposed to compound for 24 h prior to mosquito feeding. Seven days postinfection, control feeds showed an average parasite density of 26.2 oocysts per mosquito, which is well within the range of oocyst densities observed in laboratory infections [28]. ACT-451840 dose-dependently blocked oocyst development in the mosquito, with an IC50 of 30 nM (95% confidence interval: 23–39 nM) (Fig 8A). At this parasite exposure, the prevalence of infection (number of infected mosquitoes) was inhibited, with an IC50 of 104 nM (95% confidence interval: 98–110 nM) (Fig 8B).

Fig. 8. ACT-451840 blocking transmission.

Standard membrane feeding assays were performed with a 24 h pre-incubation of gametocytes with compound (indirect mode). (A) shows average oocyst intensity per mosquito and (B) shows average oocyst prevalence (percentage of mosquitoes with at least one oocyst). Error bars indicate SE from the measurements of the two groups of the 20 mosquitoes per sample. As the parasite exposure in the field is much lower (1–3 oocysts/mosquito), ACT-451840 potency might be underestimated and might have a greater effect on oocyst prevalence [29]. To address the specific effect of the compound against the parasite forms that develop in the mosquito midgut, a different mode of standard membrane feeding assay was performed, in which the compound was added to the parasite at the time of mosquito feeding. Here, ACT-451840 did not show any activity against P. falciparum oocysts at concentrations up to 1 μM (S2 Fig). These data strongly suggest that the transmission-blocking effect of ACT-451840 relies on its gametocytocidal activity.

Characterization of ACT-451840 Safety Profile: Initiation of Clinical Studies

In order to initiate investigation in humans, the preclinical safety profile of ACT-451840 was analyzed in dedicated toxicities studies performed in compliance with Good Laboratory Practice regulations and following the International Council for Harmonization guidelines. In safety pharmacology studies, no effects on central nervous and respiratory parameters were observed in rats dosed up to 1,000 mg/kg, and no effect on cardiovascular parameters were observed in dogs dosed up to 500 mg/kg. ACT-451840 was not genotoxic when assessed in vitro in a reverse mutation test or in a chromosome aberration study and in vivo in a micronucleus test. In the general oral toxicity studies performed with ACT-451840 for up to 4 wk, rats and dogs were dosed up to 2,000 mg/kg/day and 1,000 mg/kg/day, respectively. There was no evidence of local gastrointestinal toxicity. The no-observed-adverse-effect levels were established at 100 mg/kg/day in both species based on reduced body weight gain and clinical chemistry and histology findings, respectively. Based on these results, safety margins were calculated to cover the whole dose range to be tested in the single ascending dose Phase I study.

Translation of PD and PK Data from Animal Models into Man

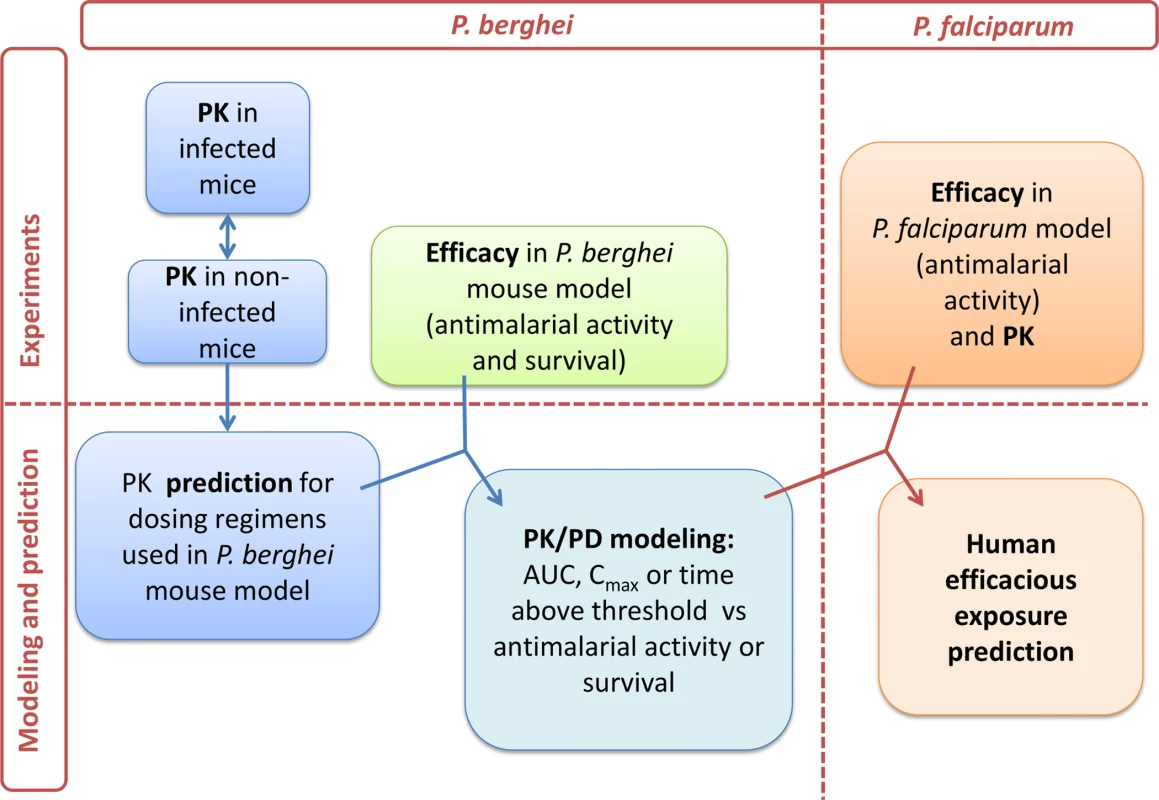

Towards the goal of initiation of a POC study and based on the results from the P. falciparum and P. berghei malaria mouse models, the human effective dose was predicted. The approach to model the PK/PD relationship is illustrated in Fig 9.

Fig. 9. PK/PD strategy.

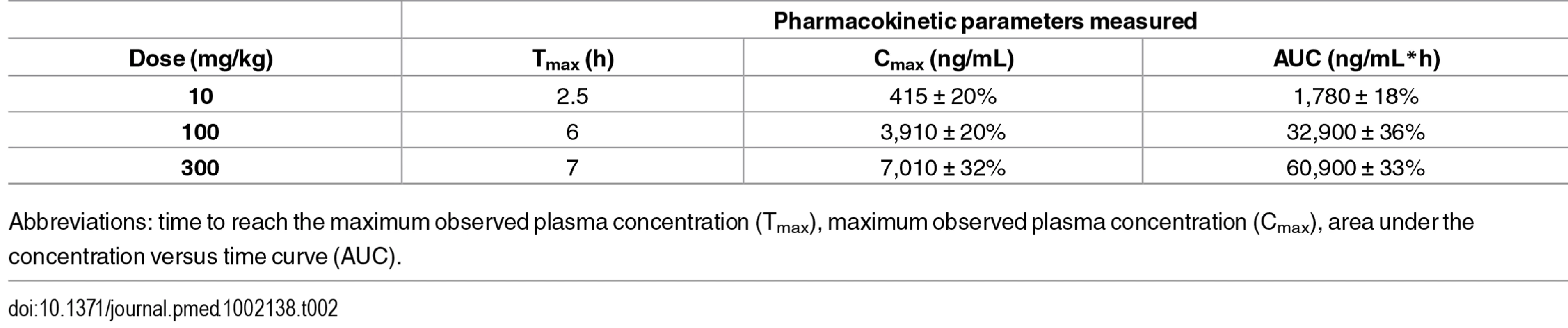

Workflow of PK and PD modeling approach towards human efficacious dose prediction. Abbreviations: maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax) and, area under the concentration versus time curve (AUC). As a first step, PK parameters of ACT-451840 were determined in healthy mice after a single oral dose of 10, 100, and 300 mg/kg body weight. The PK parameters were calculated and are shown in Table 2.

Tab. 2. Pharmacokinetics parameters of ACT-451840 in healthy mice (n = 4).

Abbreviations: time to reach the maximum observed plasma concentration (Tmax), maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax), area under the concentration versus time curve (AUC). To assess the PK parameters in infected mice, blood samples were taken at 1, 4, and 24 h after the first dose of a triple-dose regimen in the P. berghei efficacy studies. The employed doses were 15 or 30 mg/kg bis in die (b.i.d.), and 30, 50, 100, 300 mg/kg quaque die (q.d.) (n = 3/timepoint and dose). No significant difference in blood concentration was found between the time points studied in infected mice compared to those in healthy mice (S3 Fig).

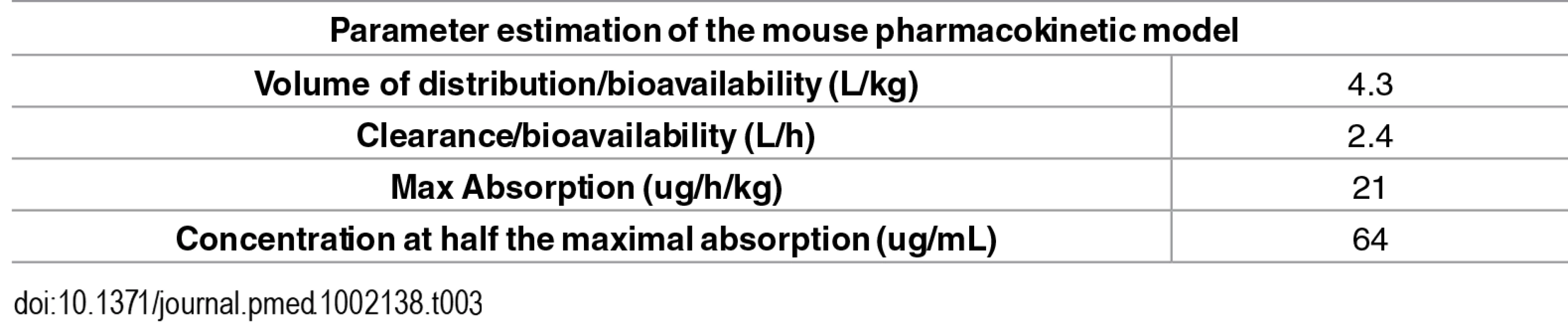

In order to analyze the PK/PD relationship, drug exposure was predicted for all tested doses in P. berghei mouse model using a single compartment model with saturable absorption based on the concentration–time profile observed after 10, 100, and 300 mg/kg single-dose regimen in healthy mice. PK model parameter estimates are shown in Table 3.

Tab. 3. Parameterization of the pharmacokinetic model.

The PK model was used to predict the blood PK parameters for all dosing regimens used in the P. berghei mouse model, as shown in Fig 6 and S2 Text.

The next step was to determine which of the PK parameters (Cmax, AUC, or time above a threshold concentration) was driving the curative efficacy of ACT-451840 in the P. berghei mouse model. To establish this PK/PD relationship, the predicted and measured PK properties were used to model curative efficacy in relation to AUC, Cmax, and time over a threshold concentration of 1,000 ng/mL. This threshold was defined as the minimum concentration needed to significantly increase the survival of mice treated with ACT-451840 after both single - and triple-dose regimens over that of control animals. The value of 1,000 ng/mL was estimated from the data in S2 Text, in which the triple-dose regimen of 10 mg/kg with a Cmax of 617 ng/mL showed no increase in survival compared to control animals, whereas the triple-dose regimen of 30 mg/kg with Cmax of 1,670 ng/mL showed an increase in survival up to 13 d.

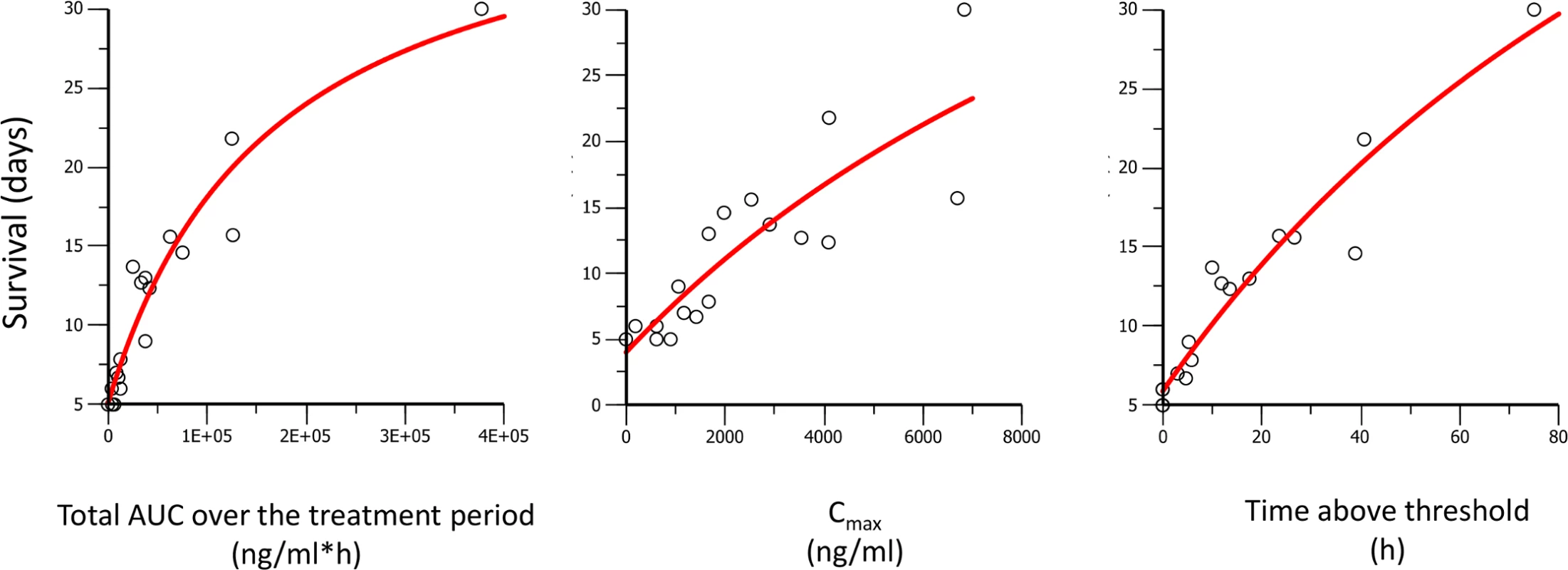

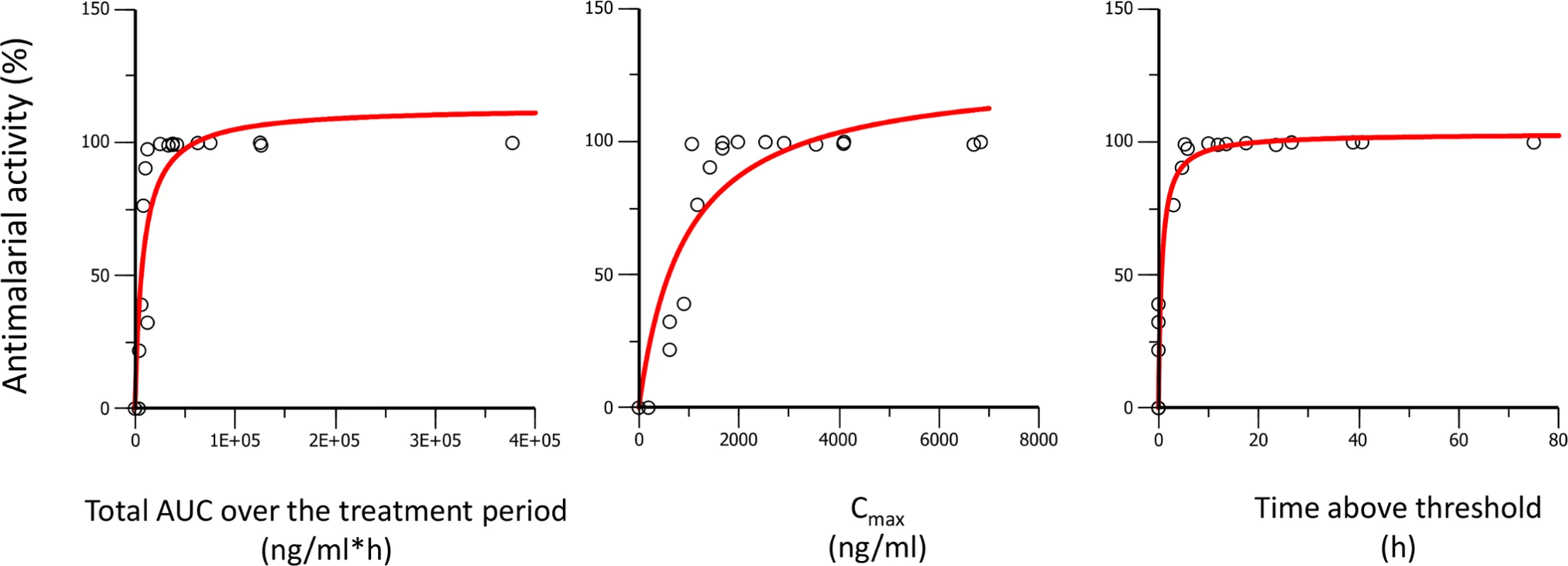

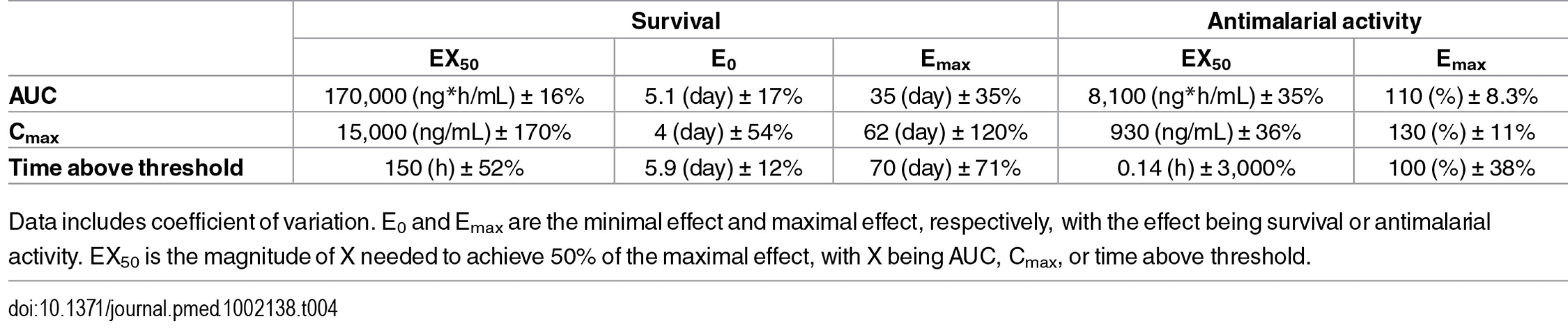

The PK/PD relationships for the P. berghei in vivo efficacy experiments are given in Fig 10 and Fig 11 and the resulting PK/PD parameters are shown in Table 4.

Fig. 10. Survival days of P. berghei infected mice plotted against AUC, Cmax, and time above threshold over the entire treatment period (1 or 3 d).

Dots are the observed days of survival; the line is the modeled relationship using a maximal effect (Emax) model. Fig. 11. Antimalarial activity in P. berghei infected mice plotted against AUC, Cmax, and time above threshold over the entire treatment period (1 or 3 d).

Dots are the observed antimalarial activity; the line is the modeled relationship using a maximal effect (Emax) model. Tab. 4. Pharmacodynamic parameters of ACT-451840 versus pharmacokinetic parameters.

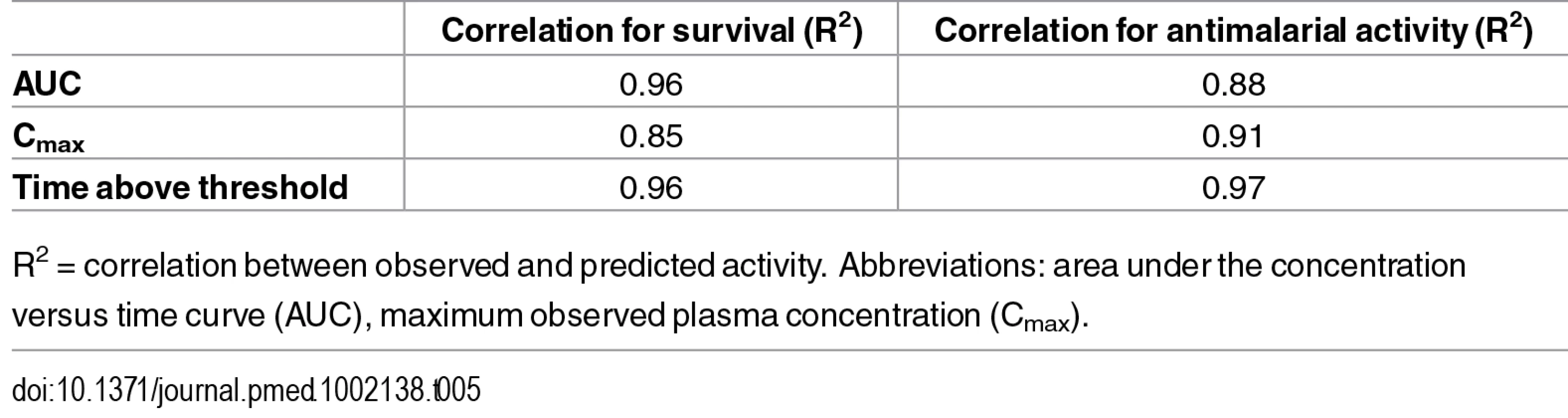

Data includes coefficient of variation. E0 and Emax are the minimal effect and maximal effect, respectively, with the effect being survival or antimalarial activity. EX50 is the magnitude of X needed to achieve 50% of the maximal effect, with X being AUC, Cmax, or time above threshold. The best fit for predicted versus observed PK/PD relationship was found for AUC and time above a threshold concentration versus survival, and time above a threshold concentration versus antimalarial activity, as illustrated by the correlation coefficients ≥0.96 (Table 5).

Tab. 5. Correlation of the observed survival or antimalarial activity versus modeled maximal effect relationship.

R2 = correlation between observed and predicted activity. Abbreviations: area under the concentration versus time curve (AUC), maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax). Survival and AUC were selected as parameters for the predictions in human. Survival is a robust readout and the relevant endpoint for clinical efficacy. AUC, rather than time above threshold, was used because the threshold value was based on PD endpoint in infected mice with P. berghei and may be different in humans infected with P. falciparum.

Having established AUC as the driver for survival in the P. berghei mouse model, this insight was used to predict an efficacious exposure against P. falciparum in humans with the results of the P. falciparum mouse model. In the P. falciparum mouse model after a quadruple-dose regimen, the ED90 of 3.7 mg/kg corresponded to a total AUC in blood of 227 ng*h/mL (linearly extrapolated from the exposure measured at a single dose of 4.7 mg/kg). The total AUC giving an ED90 in the P. berghei model (16,300 ng*h/mL after a triple-dose regimen of 13 mg/kg) was 23-fold lower than the total AUC giving cure (377,000 ng*h/mL after a triple-dose regimen of 300 mg/kg). Using this factor, the efficacious human total AUC was estimated to be 227 x 23 = 5,250 ng*h/mL, expressed in mouse blood. Correcting for the measured blood/plasma ratio of 0.6 (S3 Text), this corresponds to a predicted total efficacious human plasma AUC of 8,750 ng*h/mL. This exposure is about six times the exposure (1,408 ng*h/mL) observed after a single 500 mg dose in fed human subjects [30].

Discussion

This report presents results from vitro and in vivo experiments to preclinically characterize a novel antimalarial compound (ACT-451840). The data shown here indicate that ACT-451840 shares many of the favorable MMV TCP1 properties of artemisinin and its derivatives, such as its potency against P. falciparum and P. vivax, fast onset of action, activity against all asexual erythrocytic stages, and PRR of >4 log per cycle of asexual blood stage forms. In addition, although the potency observed in the standard membrane feeding assay was 10-fold lower than the potency of the compound against asexual blood stage parasites, ACT-451840's gametocytocidal activity blocks transmission, fulfilling the properties requested for a TCP3b [8].

In the global portfolio of malaria medicines, other recently discovered novel compounds are the synthetic peroxide OZ439 [18], the spiroindolone KAE609 [31], the imidazolopiperazines KAF156 [32], the dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor DSM265 [33], and the translation elongation factor 2 inhibitor DDD107498 [23]. ACT-451840 shares the fast-acting properties [34] with OZ439 and KAE609, which are both foreseen to be part of a single-exposure radical cure product, as the compounds fit the TCP1, 3b and TCP1, 2 and 3b, respectively [7,35]. Although KAF156 and DDD107498 share the transmission-blocking characteristics with ACT-451840, both are seen to be agents with potential for chemoprophylaxis due to their in vitro activity against liver schizonts [23,36]. Finally, DSM265 exhibits properties of a TCP 2, positioning this compound with its long duration as potential partner of a single-exposure combination, in addition to its prophylaxis potential (TCP4) [33].

In contrast to the artemisinins, the here described compound class acts through a distinct mode of action by interacting with the P. falciparum multidrug resistance protein-1 [4,5]. Combined with the finding that ACT-451840 was well tolerated in a recent single ascending dose study and exhibited a much longer terminal half-life than artemisinin, comparable to OZ439 (34 h, 2 h, and 25–30 h, respectively) [30,37,38], this novel compound has the potential to be used as a substitute for the artemisinin derivatives in combination treatments. Additionally, the in vitro activity against artemisinin-resistant strains positions ACT-451840 as a strong candidate in the race for malaria eradication.

PD properties of ACT-451840 were interpreted in two mouse models of malaria with respect to the PK properties, with the objective to establish the portable PK/PD parameters to estimate efficacious exposure following similar methodology validated with KAE609 [35]. In this PK/PD approach, the robust endpoint of animal survival and cure were chosen for clinical relevance. Using survival as endpoint, both AUC and time above a threshold concentration were drivers for efficacy. The AUC resulting in cure in the mouse models was further translated to a predicted efficacious exposure in man, which was actually about six times the exposure observed after a single dose of 500 mg in fed state in healthy subjects. Two elements might give prospect to this conservative prediction. Firstly, the threshold concentration specified in the current PK/PD analysis (1,000 ng/mL in the P. berghei model) was defined as two times the 99% inhibitory concentration in a recent publication [35]. The alternative approach used to assess efficacious concentrations in vivo calculated the minimum inhibitory concentration and estimated a minimum parasiticidal concentration from modeling of the exposure–efficacy in the P. falciparum murine model. Because exposure was measured at a single dose of ACT-451840, this method cannot be applied in this case. However, given P. berghei and P. falciparum differences, it is likely that both concentrations would be much lower for ACT-451840 than the threshold concentration in the P. berghei model. Considering the 99% inhibitory concentration of ACT-451840, the value of the threshold would be 1.8 ng/mL (2.4 nM) and would be covered for 72 h, corresponding to one and a half asexual blood reproductive cycles, after a single dose of 500 mg in fed state in healthy subjects. Secondly, the results of the phase I study indicated the presence of circulating active metabolites with, on average, a 4-fold increase in antimalarial activity [30]. Providing these active metabolites were not present in the malaria murine model (not investigated) and, therefore, not taken into account for the human efficacious dose prediction, the overall antimalarial activity in humans dosed with ACT-451840 could be even higher than expected.

The aim of efficacious dose prediction is to provide guidance for the selection of optimal doses to be investigated in POC clinical trials as monotherapy. Although artemisinin monotherapy offers rapid recovery and fast parasite clearance [39], the use of combination therapy is recommended to reduce the risk of recrudescence associated with monotherapy, which is high for treatment regimens less than 7 d in length [40], and to decrease the potential development of drug resistance [41]. This approach allowed short-course combination therapies to be deployed with excellent efficacy, tolerability, and adherence, as illustrated with the lumefantrine/artemether combination therapy Coartem [42,43]. In addition, as fat intake enhances absorption, particularly for lumefantrine [44] and ACT-451840 [30], the development of a lipid-based formulation in humans might be the next major improvement towards limiting the variability and increasing exposure. Of note, work performed at Actelion Pharmaceuticals (S4 Text) has shown that the food effect observed with ACT-451840 [30] could be mimicked by the use of lipid-based formulations in fasted conditions in dog PK studies. Therefore, dose prediction might be refined during the development of the future medicine with new formulation and combination partners.

ACT-451840 has been tested as a monotherapy in an experimental human malaria infection model, a clinical trial developed by MMV in partnership with QIMR Berghofer of Medical Research Institute (Brisbane, Australia) [45]. The dosing regimen for this POC study (500 mg in fed condition) was constrained by the conditions tested in the phase I study. The results of this study confirmed the fast action of ACT-451840 observed in in vitro and in vivo models and its gametocytocidal effect. This validates that ACT-451840 might be a good candidate for TCP1 and TCP3b in humans [34]. The future steps will consist of the development of a lipid-based formulation, the selection of a combination partner, and the determination of the activity of ACT-451840 in patients.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. World Malaria Report 2015. 2015;280.

2. Gamo F-J, Sanz LM, Vidal J, de Cozar C, Alvarez E, Lavandera J-L, et al. Thousands of chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Nature. 2010;465(7296):305–10. doi: 10.1038/nature09107 20485427

3. Wells TNC. New Medicines to Combat Malaria: An Overview of the Global Pipeline of Therapeutics. Treat Prev Malar. 2012;281–307. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-0346-0480-2

4. Brunner R, Aissaoui H, Boss C, Bozdech Z, Brun R, Corminboeuf O, et al. Identification of a new chemical class of antimalarials. J Infect Dis. 2012;206 : 735–43. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis418 22732921

5. Brunner R, Ng CL, Aissaoui H, Akabas MH, Boss C, Brun R, et al. UV-triggered affinity capture identifies interactions between the Plasmodium falciparum multidrug resistance protein 1 (PfMDR1) and antimalarial agents in live parasitized cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(31):22576–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.453159 23754276

6. Ng CL, Siciliano G, Lee MCS, Almeida MJ De, Corey VC, Bopp SE, et al. CRISPR-Cas9-modified pfmdr1 protects Plasmodium falciparum asexual blood stages and gametocytes against a class of piperazine-containing compounds but potentiates artemisinin-based combination therapy partner drugs. Mol Microbiol. 2016;1–35.

7. Burrows JN, van Huijsduijnen RH, Möhrle JJ, Oeuvray C, Wells TNC. Designing the next generation of medicines for malaria control and eradication. Malar J. 2013;12 : 187. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3685552&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-187 23742293

8. Leroy D, Campo B, Ding X, Jeremy, Burrows N, Cherbuin S. Defining the biology component of the drug discovery strategy for malaria eradication. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30(10): 478–90.

9. Snyder C, Chollet J, Santo-Tomas J, Scheurer C, Wittlin S. In vitro and in vivo interaction of synthetic peroxide RBx11160 (OZ277) with piperaquine in Plasmodium models. Exp Parasitol. 2007;115 : 296–300. 17087929

10. Schleiferböck S, Scheurer C, Ihara M, Itoh I, Bathurst I, Burrows JN, et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of the antimalarial lead compound SSJ-183 in Plasmodium models. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7 : 1377–84. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S51298 24255594

11. Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Khim N, Sreng S, Chim P, Kim S, et al. Novel phenotypic assays for the detection of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: In-vitro and ex-vivo drug-response studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(13):1043–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70252-4

12. Straimer J, Gnädig NF, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Duru V, Ramadani AP, et al. K13-propeller mutations confer artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates. Science. 2014;2624(1985):428–31.

13. Ratcliff A, Siswantoro H, Kenangalem E, Wuwung M, Brockman A, Edstein MD, et al. Therapeutic response of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine in southern Papua, Indonesia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101(4):351–9. 17028048

14. Hasugian AR, Purba HLE, Kenangalem E, Wuwung RM, Ebsworth EP, Maristela R, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine versus artesunate-amodiaquine: superior efficacy and posttreatment prophylaxis against multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax malaria. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(8):1067–74. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2532501&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract 17366451

15. Hasugian AR, Tjitra E, Ratcliff A, Siswantoro H, Kenangalem E, Wuwung RM, et al. In vivo and in vitro efficacy of amodiaquine monotherapy for treatment of infection by chloroquine-resistant plasmodium vivax. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(3):1094–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01511-08 19104023

16. Sanz LM, Crespo B, De-Cózar C, Ding XC, Llergo JL, Burrows JN, et al. P. falciparum in vitro killing rates allow to discriminate between different antimalarial mode-of-action. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2).

17. Desjardins RE, Canfield CJ, Haynes JD, Chulay JD. Quantitative assessment of antimalarial activity in vitro by a semiautomated microdilution technique. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16(6):710–8. 394674

18. Charman S, Arbe-Barnes S, Bathurst IC, Brun R, Campbell M, Charman WN, et al. Synthetic ozonide drug candidate OZ439 offers new hope for a single-dose cure of uncomplicated malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108 : 4400–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015762108 21300861

19. Fidock D a, Rosenthal PJ, Croft SL, Brun R, Nwaka S. Antimalarial drug discovery: efficacy models for compound screening. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(6):509–20. 15173840

20. Angulo-Barturen I, Jiménez-Díaz MB, Mulet T, Rullas J, Herreros E, Ferrer S, et al. A murine model of falciparum-malaria by in vivo selection of competent strains in non-myelodepleted mice engrafted with human erythrocytes. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(5).

21. Jiménez-Díaz MB, Mulet T, Viera S, Gómez V, Garuti H, Ibáñez J, et al. Improved murine model of malaria using Plasmodium falciparum competent strains and non-myelodepleted NOD-scid IL2Rγnull mice engrafted with human erythrocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(10):4533–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00519-09 19596869

22. Ruecker a., Mathias DK, Straschil U, Churcher TS, Dinglasan RR, Leroy D, et al. A Male and Female Gametocyte Functional Viability Assay To Identify Biologically Relevant Malaria Transmission-Blocking Drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(12):7292–302. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03666-14 25267664

23. Baragaña B, Hallyburton I, Lee MCS, Norcross NR, Grimaldi R, Otto TD, et al. A novel multiple-stage antimalarial agent that inhibits protein synthesis. Nature. 2015;522(7556):315–20. http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/nature14451 doi: 10.1038/nature14451 26085270

24. Maerki S, Brun R, Charman S a., Dorn A, Matile H, Wittlin S. In vitro assessment of the pharmacodynamic properties and the partitioning of OZ277/RBx-11160 in cultures of Plasmodium falciparum. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58(1):52–8. 16735432

25. Peatey CL, Leroy D, Gardiner DL, Trenholme KR. Anti-malarial drugs: how effective are they against Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes? Malar J. 2012;11(1):34.

26. Bousema T, Okell L, Shekalaghe S, Griffin JT, Omar S, Sawa P, et al. Revisiting the circulation time of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes: molecular detection methods to estimate the duration of gametocyte carriage and the effect of gametocytocidal drugs. Malar J. 2010;9 : 136. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-136 20497536

27. Delves MJ, Ruecker A, Straschil U, Lelièvre J, Marques S, López-Barragán MJ, et al. Male and female Plasmodium falciparum mature gametocytes show different responses to antimalarial drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(7):3268–74. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00325-13 23629698

28. Kolk MVANDER, Vlas SJDE, Saul A. Evaluation of the standard membrane feeding assay (SMFA) for the determination of malaria transmission-reducing activity using empirical data. Parasitology. 2005;130 : 13–22. 15700753

29. Churcher TS, Blagborough AM, Delves M, Ramakrishnan C, Kapulu MC, Williams AR, et al. Measuring the blockade of malaria transmission—An analysis of the Standard Membrane Feeding Assay. Int J Parasitol. 2012;42(11):1037–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.09.002 23023048

30. Bruderer S, Hurst N, de Kanter R, Miraval T, Pfeifer T, Donazzolo Y, et al. First-in-Humans Study of the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of ACT-451840, a New Chemical Entity with Antimalarial Activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(2):935–42. http://aac.asm.org/lookup/doi/10.1128/AAC.04125-14 doi: 10.1128/AAC.04125-14 25421475

31. Rottmann M, McNamara C, Yeung BKS, Lee MCS, Zou B, Russell B, et al. Spiroindolones, a potent compound class for the treatment of malaria. Science. 2010;329 (September):1175–80.

32. Meister S, Plouffe DM, Kuhen KL, Bonamy GMC, Wu T, Barnes SW, et al. Imaging of Plasmodium Liver Stages to Drive Next-Generation Antimalarial Drug Discovery. Science. 2011;334 : 1372–7.

33. Phillips MA, Lotharius J, Marsh K, White J, Dayan A, White KL, et al. A long-duration dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor (DSM265) for prevention and treatment of malaria. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(296):296ra111. http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/7/296/296ra111 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa6645 26180101

34. Krause A, Dingemanse J, Mathis A, Marquart L, Möhrle JJ, McCarthy JS. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modelling of the antimalarial effect of Actelion-451840 in an induced blood stage malaria study in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/bcp.12962

35. Lakshminarayana SB, Freymond C, Fischli C, Yu J, Weber S, Goh A, et al. Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Analysis of Spiroindolone Analogs and KAE609 in a Murine Malaria Model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(2):1200–10. http://aac.asm.org/lookup/doi/10.1128/AAC.03274-14 doi: 10.1128/AAC.03274-14 25487807

36. Kuhen KL, Chatterjee AK, Rottmann M, Gagaring K, Borboa R, Buenviaje J, et al. KAF156 is an antimalarial clinical candidate with potential for use in prophylaxis, treatment, and prevention of disease transmission. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(9):5060–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02727-13 24913172

37. Medhi B, Patyar S, Rao RS, Byrav Ds P, Prakash A. Pharmacokinetic and toxicological profile of artemisinin compounds: An update. Pharmacology. 2009;84(6):323–32. doi: 10.1159/000252658 19851082

38. Moehrle JJ, Duparc S, Siethoff C, van Giersbergen PLM, Craft JC, Arbe-Barnes S, et al. First-in-man safety and pharmacokinetics of synthetic ozonide OZ439 demonstrates an improved exposure profile relative to other peroxide antimalarials. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(2):535–48.

39. Price R, Van Vugt M, Nosten F, Luxemburger C, Brockman A, Phaipun L, et al. Artesunate versus artemether for the treatment of recrudescent multidrug-resistant falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59(6):883–8. 9886194

40. Price R, Luxemburger C, van Vugt M, Nosten F, Kham a, Simpson J, et al. Artesunate and mefloquine in the treatment of uncomplicated multidrug - resistant hyperparasitaemic falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92 : 207–11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/htbin-post/Entrez/query?db=m&form=6&dopt=r&uid=0009764335 9764335

41. White N. Antimalarial drug resistance and combination chemotherapy. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;354(1384):739–49. 10365399

42. Van Vugt M, Wilairatana P, Gemperli B, Gathmann I, Phaipun L, Brockman a., et al. Efficacy of six doses of artemether-lumefantrine (benflumetol) in multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60(6):936–42. 10403324

43. Lefèvre G, Looareesuwan S, Treeprasertsuk S, Krudsood S, Silachamroon U, Gathmann I, et al. A clinical and pharmacokinetic trial of six doses of artemether-lumefantrine for multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64(5):247–56.

44. Djimdé A, Lefèvre G. Understanding the pharmacokinetics of Coartem. Malar J. 2009;8 Suppl 1:S4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-S1-S4 19818171

45. McCarthy JS, Sekuloski S, Griffin PM, Elliott S, Douglas N, Peatey C, et al. A pilot randomised trial of induced blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum infections in healthy volunteers for testing efficacy of new antimalarial drugs. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):6–13.

Štítky

Interné lekárstvo

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Medicine

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2016 Číslo 10- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Intermitentní hladovění v prevenci a léčbě chorob

- Statinová intolerance

- Co dělat při intoleranci statinů?

- Monoklonální protilátky v léčbě hyperlipidemií

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Sailing in Uncharted Waters: Carefully Navigating the Polio Endgame

- Core Outcome Set–STAndards for Reporting: The COS-STAR Statement

- Improving the Science of Measles Prevention—Will It Make for a Better Immunization Program?

- Burden of Six Healthcare-Associated Infections on European Population Health: Estimating Incidence-Based Disability-Adjusted Life Years through a Population Prevalence-Based Modelling Study

- Population Immunity against Serotype-2 Poliomyelitis Leading up to the Global Withdrawal of the Oral Poliovirus Vaccine: Spatio-temporal Modelling of Surveillance Data

- Conveying Equipoise during Recruitment for Clinical Trials: Qualitative Synthesis of Clinicians’ Practices across Six Randomised Controlled Trials

- How Relevant Is Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus?

- A Holistic, Person-Centred Care Model for Victims of Sexual Violence in Democratic Republic of Congo: The Panzi Hospital One-Stop Centre Model of Care

- Impact on Epidemic Measles of Vaccination Campaigns Triggered by Disease Outbreaks or Serosurveys: A Modeling Study

- The Global Burden of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: A Re-estimation Using Mathematical Modelling

- Circulating Apolipoprotein E Concentration and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Meta-analysis of Results from Three Studies

- Towards Equity in Service Provision for Gay Men and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men in Repressive Contexts

- Obstetric Facility Quality and Newborn Mortality in Malawi: A Cross-Sectional Study

- Prophylactic Oral Dextrose Gel for Newborn Babies at Risk of Neonatal Hypoglycaemia: A Randomised Controlled Dose-Finding Trial (the Pre-hPOD Study)

- Characterization of Novel Antimalarial Compound ACT-451840: Preclinical Assessment of Activity and Dose–Efficacy Modeling

- Regulatory T Cell Responses in Participants with Type 1 Diabetes after a Single Dose of Interleukin-2: A Non-Randomised, Open Label, Adaptive Dose-Finding Trial

- Orthostatic Hypotension and the Long-Term Risk of Dementia: A Population-Based Study

- Tradeoffs in Introduction Policies for the Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Bedaquiline: A Model-Based Analysis

- Whole Genome Sequence Analysis of a Large Isoniazid-Resistant Tuberculosis Outbreak in London: A Retrospective Observational Study

- Texas and Its Measles Epidemics

- Impacts on Breastfeeding Practices of At-Scale Strategies That Combine Intensive Interpersonal Counseling, Mass Media, and Community Mobilization: Results of Cluster-Randomized Program Evaluations in Bangladesh and Viet Nam

- The Tuberculosis Cascade of Care in India’s Public Sector: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- PLOS Medicine

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Prophylactic Oral Dextrose Gel for Newborn Babies at Risk of Neonatal Hypoglycaemia: A Randomised Controlled Dose-Finding Trial (the Pre-hPOD Study)

- Regulatory T Cell Responses in Participants with Type 1 Diabetes after a Single Dose of Interleukin-2: A Non-Randomised, Open Label, Adaptive Dose-Finding Trial

- Orthostatic Hypotension and the Long-Term Risk of Dementia: A Population-Based Study

- Improving the Science of Measles Prevention—Will It Make for a Better Immunization Program?

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy