-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Evolution of Linked Avirulence Effectors in Is Affected by Genomic Environment and Exposure to Resistance Genes in Host Plants

Brassica napus (canola) cultivars and isolates of the blackleg fungus, Leptosphaeria maculans interact in a ‘gene for gene’ manner whereby plant resistance (R) genes are complementary to pathogen avirulence (Avr) genes. Avirulence genes encode proteins that belong to a class of pathogen molecules known as effectors, which includes small secreted proteins that play a role in disease. In Australia in 2003 canola cultivars with the Rlm1 resistance gene suffered a breakdown of disease resistance, resulting in severe yield losses. This was associated with a large increase in the frequency of virulence alleles of the complementary avirulence gene, AvrLm1, in fungal populations. Surprisingly, the frequency of virulence alleles of AvrLm6 (complementary to Rlm6) also increased dramatically, even though the cultivars did not contain Rlm6. In the L. maculans genome, AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 are linked along with five other genes in a region interspersed with transposable elements that have been degenerated by Repeat-Induced Point (RIP) mutations. Analyses of 295 Australian isolates showed deletions, RIP mutations and/or non-RIP derived amino acid substitutions in the predicted proteins encoded by these seven genes. The degree of RIP mutations within single copy sequences in this region was proportional to their proximity to the degenerated transposable elements. The RIP alleles were monophyletic and were present only in isolates collected after resistance conferred by Rlm1 broke down, whereas deletion alleles belonged to several polyphyletic lineages and were present before and after the resistance breakdown. Thus, genomic environment and exposure to resistance genes in B. napus has affected the evolution of these linked avirulence genes in L. maculans.

Published in the journal: Evolution of Linked Avirulence Effectors in Is Affected by Genomic Environment and Exposure to Resistance Genes in Host Plants. PLoS Pathog 6(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001180

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001180Summary

Brassica napus (canola) cultivars and isolates of the blackleg fungus, Leptosphaeria maculans interact in a ‘gene for gene’ manner whereby plant resistance (R) genes are complementary to pathogen avirulence (Avr) genes. Avirulence genes encode proteins that belong to a class of pathogen molecules known as effectors, which includes small secreted proteins that play a role in disease. In Australia in 2003 canola cultivars with the Rlm1 resistance gene suffered a breakdown of disease resistance, resulting in severe yield losses. This was associated with a large increase in the frequency of virulence alleles of the complementary avirulence gene, AvrLm1, in fungal populations. Surprisingly, the frequency of virulence alleles of AvrLm6 (complementary to Rlm6) also increased dramatically, even though the cultivars did not contain Rlm6. In the L. maculans genome, AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 are linked along with five other genes in a region interspersed with transposable elements that have been degenerated by Repeat-Induced Point (RIP) mutations. Analyses of 295 Australian isolates showed deletions, RIP mutations and/or non-RIP derived amino acid substitutions in the predicted proteins encoded by these seven genes. The degree of RIP mutations within single copy sequences in this region was proportional to their proximity to the degenerated transposable elements. The RIP alleles were monophyletic and were present only in isolates collected after resistance conferred by Rlm1 broke down, whereas deletion alleles belonged to several polyphyletic lineages and were present before and after the resistance breakdown. Thus, genomic environment and exposure to resistance genes in B. napus has affected the evolution of these linked avirulence genes in L. maculans.

Introduction

The fungus Leptosphaeria maculans causes blackleg (phoma stem canker) and is the major disease of Brassica napus (canola) worldwide [1]. The major source of inoculum is wind-borne ascospores, which are released from sexual fruiting bodies on infected stubble (crop residue) of previous crops and can be transmitted several kilometres. This fungus has a ‘gene for gene’ interaction with its host (canola) such that pathogen avirulence alleles render the pathogen unable to attack host genotypes with the corresponding resistance genes [2].

Twelve genes conferring resistance to L. maculans (Rlm1-9, LepR1-3) have been identified from Brassica species [3], [4]. Nine of these genes have been mapped but none have yet been cloned [5], [6]. Of the corresponding avirulence genes in L. maculans, seven have been mapped to two gene clusters, AvrLm1-2-6 and AvrLm3-4-7-9, located on separate L. maculans chromosomes [7]. Three genes, AvrLm1, AvrLm6 and AvrLm4-7, have been cloned and characterised [8], [9], [10]. Avirulence proteins belong to a class of molecules called effectors. Effectors are small molecules or proteins produced by the pathogen that alter host-cell structure and function, facilitate infection (for example, toxins) and/or induce defence responses (for example, avirulence proteins), and are generally essential for disease progression [11]. Many effectors are small, secreted proteins (SSPs), which are cysteine-rich, share no sequence similarity with genes from other species, are often highly polymorphic between isolates of a single species and are expressed highly in planta [12]. The AvrLm1, AvrLm4-7 and AvrLm6 proteins of L. maculans are effector molecules with an avirulence function. AvrLm6 and AvrLm4-7 encode SSPs with six and eight cysteine residues, respectively, whilst the AvrLm1 protein, which is also a SSP, has only one cysteine [8], [9], [10].

Leptosphaeria maculans undergoes sexual recombination prolifically and populations can rapidly adapt to selection pressures imposed by the host such as exposure to resistance conferred by single or major genes. This situation increases the frequency of virulent isolates and can cause resistance to break down, often resulting in severe yield losses [13]. Three examples of this breakdown are discussed below, the most dramatic one occurring in Australia in 2003.

Prior to 2000 the Australian canola industry relied on ‘polygenic’ cultivars with multiple resistance genes. Yield losses were generally low. In 2000, cultivars with major gene resistance, termed ‘sylvestris’ resistance, were released commercially and grown extensively in some areas of Australia. These cultivars were derived from a synthetic B. napus line produced by crossing the two progenitor species, B. oleracea subsp. alboglabra and an accession of B. rapa subsp. sylvestris that had a high level of resistance to L. maculans [14]. For several years these cultivars showed little or no disease but in 2003, resistance failed, resulting in up to 90% yield losses in the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia, costing the industry between $5–10 million AUD [15], [16]. These cultivars contained resistance genes Rlm1 and RlmS, suggesting that both sources of resistance failed simultaneously [17]. After 2004, these cultivars were withdrawn from sale although they were still grown in yield trial sites around Australia. A similar but less dramatic situation occurred in France when resistance conferred by Rlm1 was rendered ineffective within five years of commercial release of Rlm1-containing cultivars [13], [18]. Another breakdown of resistance was observed in field trial experiments in France that had been designed to assess the durability of a resistance gene Rlm6. In these experiments B. napus lines containing Rlm6 were sown into L. maculans-infected stubble of a Rlm6–containing line over a four year period [19]. After three years of this contrived selection, the frequency of virulence in fungal populations towards Rlm6 was so high that this resistance was rendered ineffective and the lines suffered extremely high levels of disease.

The three avirulence genes, AvrLm1, AvrLm6 and AvrLm4-7, cloned from L. maculans are located within AT-rich, gene-poor regions that are riddled with degenerated copies of transposable elements [8], [9], [10]. These transposable elements appear to have been inactivated via repeat-induced point (RIP) mutations [20]. RIP is an ascomycete-specific process that alters the sequence of multicopy DNA. Nucleotide changes CpA to TpA and TpG to TpA are conferred during meiosis, often generating stop codons, thereby inactivating genes [21]. Additionally, RIP mutations have been inferred bioinformatically in various transposable elements throughout the L. maculans genome and in AvrLm6 [22]. AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 are genetically linked and different types of mutations leading to virulence have been reported. The entire AvrLm1 locus was deleted in 285 of 290 (98%) isolates that were virulent towards Rlm1 [20]. Fudal et al. characterised the AvrLm6 locus in a different set of 105 isolates, most of which were cultured from Rlm6–containing lines during the field trial in France described above [22], [23]. Deletions and RIP were responsible for virulence in 45 (66%) and 17 (24%) isolates, respectively, that were virulent towards the Rlm6 gene [22].

In this paper we relate changes in the types and frequencies of mutations in genes including AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 to the selection pressure imposed by extensive regional sowing of B. napus cultivars with sylvestris resistance.

Results

Virulence of Australian isolates of L. maculans and analysis of mutations at AvrLm1 and AvrLm6

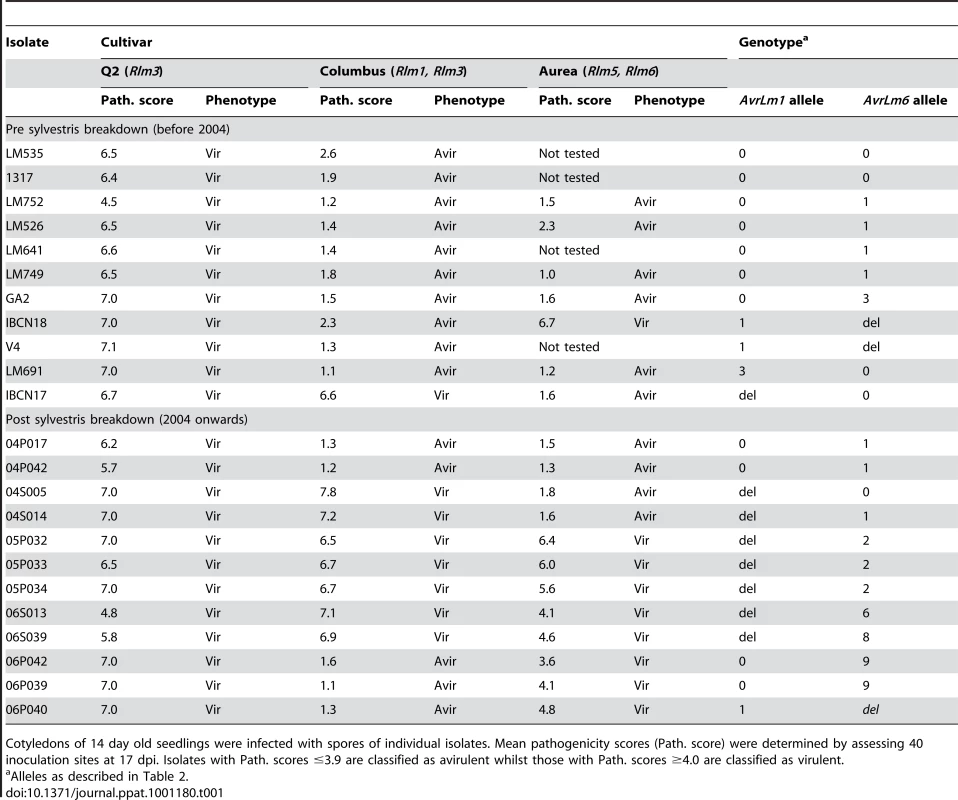

In preliminary experiments to see if the breakdown of ‘sylvestris resistance’ in B. napus seen in the field [15] correlated with changes in frequency of virulence towards Rlm1 in individual L. maculans isolates, 11 isolates collected prior to the breakdown (before 2004) and 12 isolates collected after the breakdown (2004 onwards) were screened for virulence on B. napus cultivars Q2 (with Rlm3) and Columbus (Rlm1, Rlm3). Cotyledons of 14 day old plants were inoculated with individual isolates and symptoms were scored 17 days later. All isolates were virulent on the susceptible control, cv. Q2. Ten of the 11 isolates collected prior to 2004 were avirulent on the Rlm1-containing cultivar, Columbus. However, seven of ten isolates collected from 2004 onwards were virulent towards Rlm1 (Table 1). A subset of these isolates was inoculated onto the B. napus cultivar Aurea (Rlm6). Of seven of the 11 isolates collected prior to 2004, only one was virulent towards Rlm6. However, of 12 isolates collected from 2004 onwards, eight were virulent towards Rlm6 (Table 1). These results suggested that there was a significant change in frequencies of virulent alleles of AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 associated with breakdown of ‘sylvestris resistance’. These isolates were then genotyped at the AvrLm1, AvrLm6 and mating type loci using PCR-based screening [20], [22], [24] and as expected, the virulence phenotypes corresponded with avrLm1 and /or avrLm6 genotypes (Table 1).

Tab. 1. Pathogenicity of Australian isolates of Leptosphaeria maculans on cotyledons of Brassica napus cultivars Q2 and Columbus and B. juncea cv. Aurea.

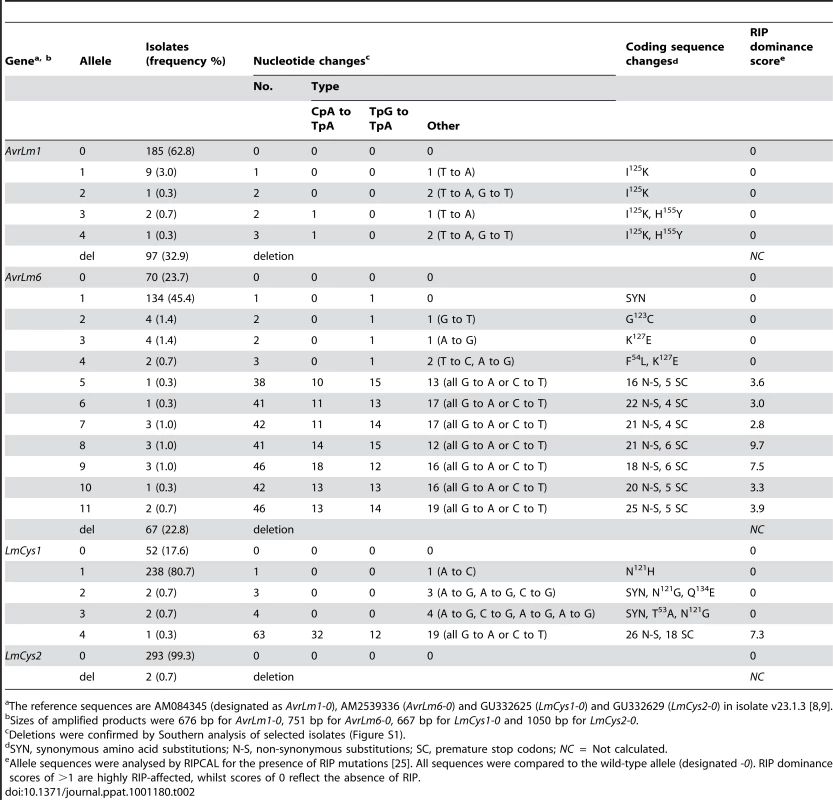

Cotyledons of 14 day old seedlings were infected with spores of individual isolates. Mean pathogenicity scores (Path. score) were determined by assessing 40 inoculation sites at 17 dpi. Isolates with Path. scores ≤3.9 are classified as avirulent whilst those with Path. scores ≥4.0 are classified as virulent. Changes in allele frequencies were then examined in a total of 295 Australian isolates. Of these 137 were collected between 1987 and 2003, prior to the breakdown of sylvestris resistance, whilst the remaining 158 isolates were collected between 2004 and 2008, after the resistance breakdown (Table S1). These isolates were collected from stubble of a range of canola cultivars with different resistance genes. One third of the isolates had a deletion of AvrLm1 (Table 2), whilst 63% had the allele of isolate v23.1.3, whose genome has been sequenced. Alleles of this isolate hereafter are referred to as wild type alleles (e.g. AvrLm1-0). As expected, isolates with AvrLm1-0 were avirulent towards Rlm1 (Tables 1 and 2). The remaining eight isolates comprised four alleles with coding sequence changes conferring non-synonymous substitutions (I125K and/or H155Y). Isolates harbouring these alleles were avirulent on the Rlm1 - containing B. napus line (Table 1). Thirteen alleles of AvrLm6 were detected (Table 2). AvrLm6 was deleted in 20% of isolates, thus conferring virulence towards Rlm6, whilst 24% had the allele of the sequenced isolate and conferred avirulence towards Rlm6 (Tables 1 and 2). Other isolates virulent towards the Rlm6-containing cultivar had alleles with stop codons conferred by base changes reminiscent of RIP mutation. Accordingly, allele sequences were analysed by RIPCAL, a software tool that visualises the physical distribution of RIP mutation and reports a RIP dominance score indicating the degree of RIP in each sequence. Sequences with RIP dominance scores >1 are highly RIP-affected having a high proportion of CpA to TpA, or TpG to TpC RIP mutations [25]. RIPCAL analysis did not detect RIP in any AvrLm1 alleles, but detected RIP in seven AvrLm6 alleles. These RIP mutations resulted in numerous non-synonymous changes as well as premature stop codons (between 4 and 6), which were within all RIP-affected alleles (Table 2). Southern hybridisation results suggest that there is only a single copy of the AvrLm6 locus within isolates harbouring the RIP alleles (Figure S1). The remaining alleles of AvrLm6 (AvrLm6-1, -2,-3 and -4) harboured single or few nucleotide changes leading to synonymous or amino acid substitutions (G123C, K127E, F54L) compared to isolate v23.1.3 (AvrLm6-0). These amino acid substitutions were generated via non-RIP like mutations (henceforth referred to as non-RIP amino acid substitutions). Isolates harbouring AvrLm6-1, AvrLm6-3 or AvrLm6-4 alleles were avirulent towards cv. Aurea, whilst the four isolates harbouring the AvrLm6-2 allele (G123C) were virulent (Table 1).

Tab. 2. Alleles of AvrLm1, AvrLm6, LmCys1 and LmCys2 in 295 Australian isolates of Leptosphaeria maculans.

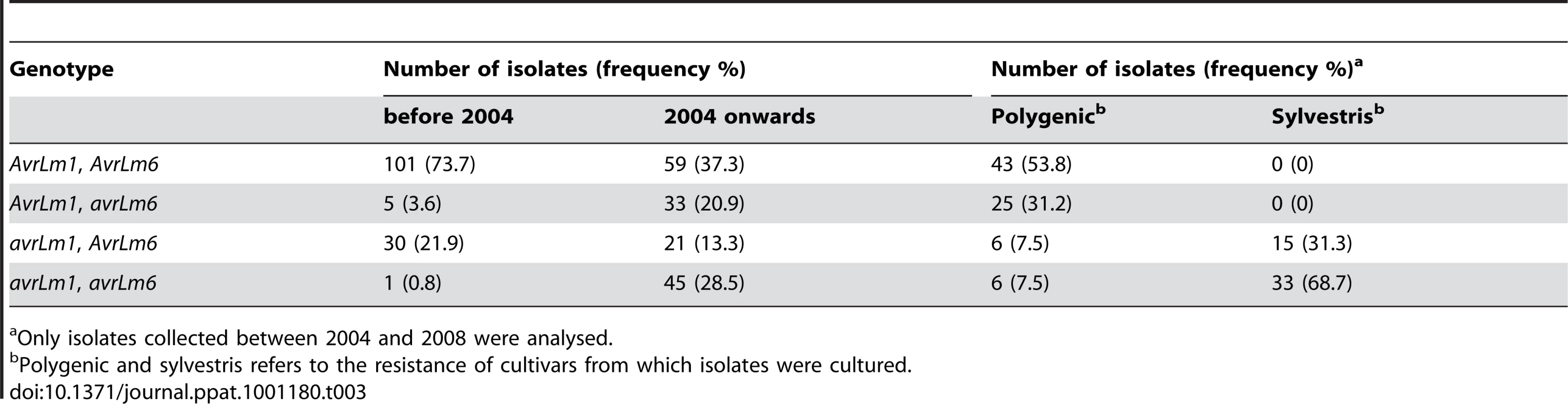

The reference sequences are AM084345 (designated as AvrLm1-0), AM2539336 (AvrLm6-0) and GU332625 (LmCys1-0) and GU332629 (LmCys2-0) in isolate v23.1.3 [8], [9]. No RIP-affected alleles were present in isolates collected prior to the breakdown of sylvestris resistance. However, the 158 isolates collected after the breakdown had seven AvrLm6 RIP alleles (frequency of 8.9%) and there was a very large increase in the frequency of deletion alleles of AvrLm1 (22.6 to 41.8%) and AvrLm6 (4.4 to 38.7). This was a nine-fold increase in frequency of avrLm6 (Table S2). Thirty four (11.5%) isolates had deletions of both AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 and only one of these isolates was collected prior to the breakdown. All 295 isolates were grouped into four genotypic classes (AvrLm1, AvrLm6; AvrLm1, avrLm6; avrLm1, Avrlm6; avrLm1, avrlm6). The frequency of AvrLm1, AvrLm6 isolates was 73.7% prior to the breakdown, but decreased to 37.3% afterwards (Table 3). Conversely, the frequency of avrLm1, avrlm6 isolates was only 0.8% prior to the breakdown, but increased to 28.5% afterwards.

Tab. 3. Changes in the frequency of the profile of alleles of AvrLm1 and Avrlm6 of Leptosphaeria maculans isolates before and after the breakdown of ‘sylvestris resistance’ and in relation to stubble source of isolates.

Only isolates collected between 2004 and 2008 were analysed. Nine of the 14 isolates harbouring RIP alleles (64%) had a deletion allele at the AvrLm1 locus and all these isolates were cultured from stubble of cultivars with sylvestris resistance. Additionally, all four isolates harbouring the virulent AvrLm6-2 allele (G123C) had a deletion allele at AvrLm1 (Table S3). When the isolates cultured from 2004 onwards were categorised in terms of the stubble from which they were derived, all those cultured from ‘sylvestris stubble’ had the avrLm1 allele (Table 3) as expected, due to the presence of Rlm1 in these cultivars [17]. Conversely, only 15% of isolates cultured from stubble of polygenic cultivars, which do not have Rlm1 nor Rlm6, had the avrLm1 allele. The frequency of avrLm6 was 38.7% in isolates cultured from ‘polygenic’ stubble, compared to 68.7% of isolates cultured from ‘sylvestris’ stubble (Table 3). For all comparisons of isolates, there were no significant differences in allele frequencies at the mating type locus. Since the mating-type locus is not under selection pressure, a 1∶1 ratio of each allele suggests that sampling of isolates has been random (data not shown).

Characteristics of the genomic environment of AvrLm1 and AvrLm6

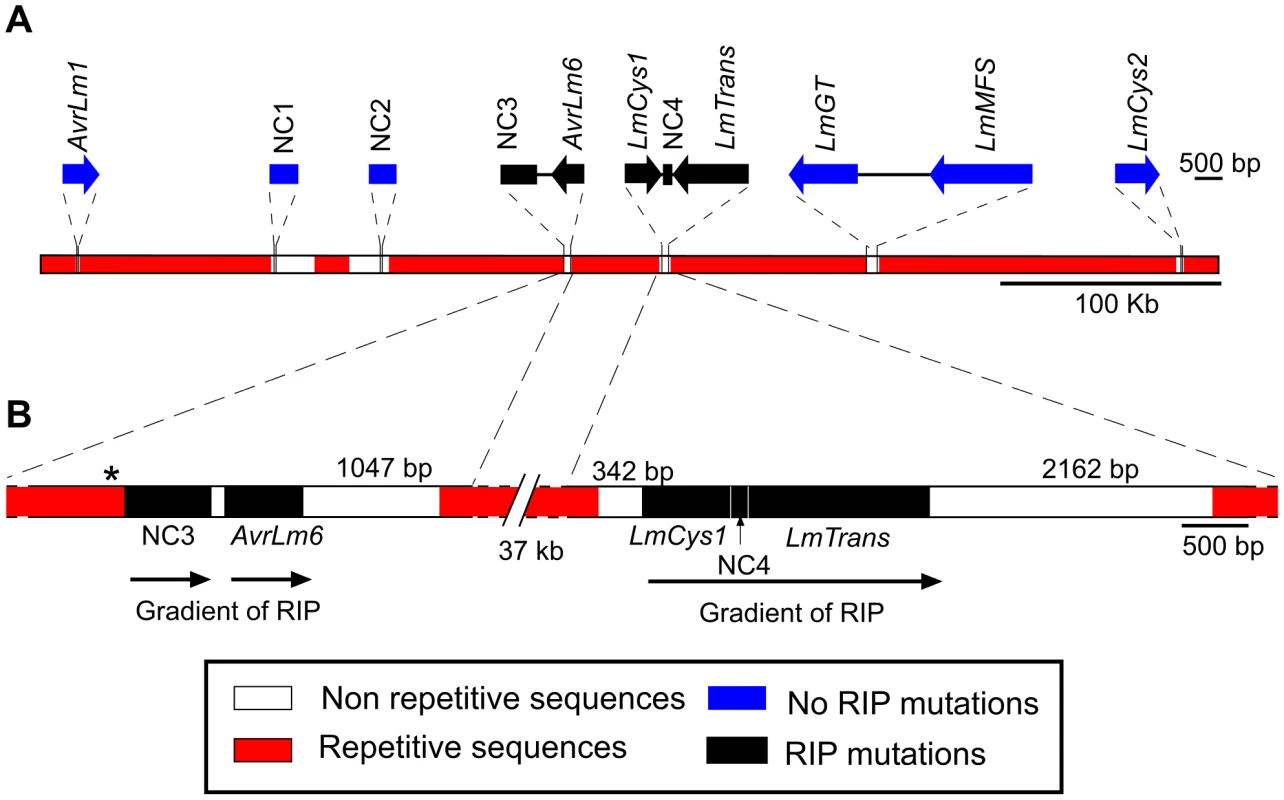

Because of the marked difference in the AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 allele frequencies before and after the breakdown of sylvestris resistance, the region flanking these genes was characterised to identify any features that might have influenced allele frequency. A 520 kb AT-rich genomic region bordered by AvrLm1 and LmCys2 (Figure 1A) was examined. Part of this region has been described previously in isolate v23.1.3 [8] and includes two additional genes encoding SSPs, LmCys1 and LmCys2. Three other genes, LmTrans, LmGT and LmMFS were present; LmCys1, LmTrans, LmGT, LmMFS and LmCys2 have been reported previously [8], [9] but sequence data are only in the form of BAC clones. The features of the proteins are listed below and in Table S4.

Fig. 1. Location of the genes and non-coding, non-repetitive regions analysed from a 520 kb region of the Leptosphaeria maculans genome located on a 2.6 Mb chromosome in isolate v23.1.3.

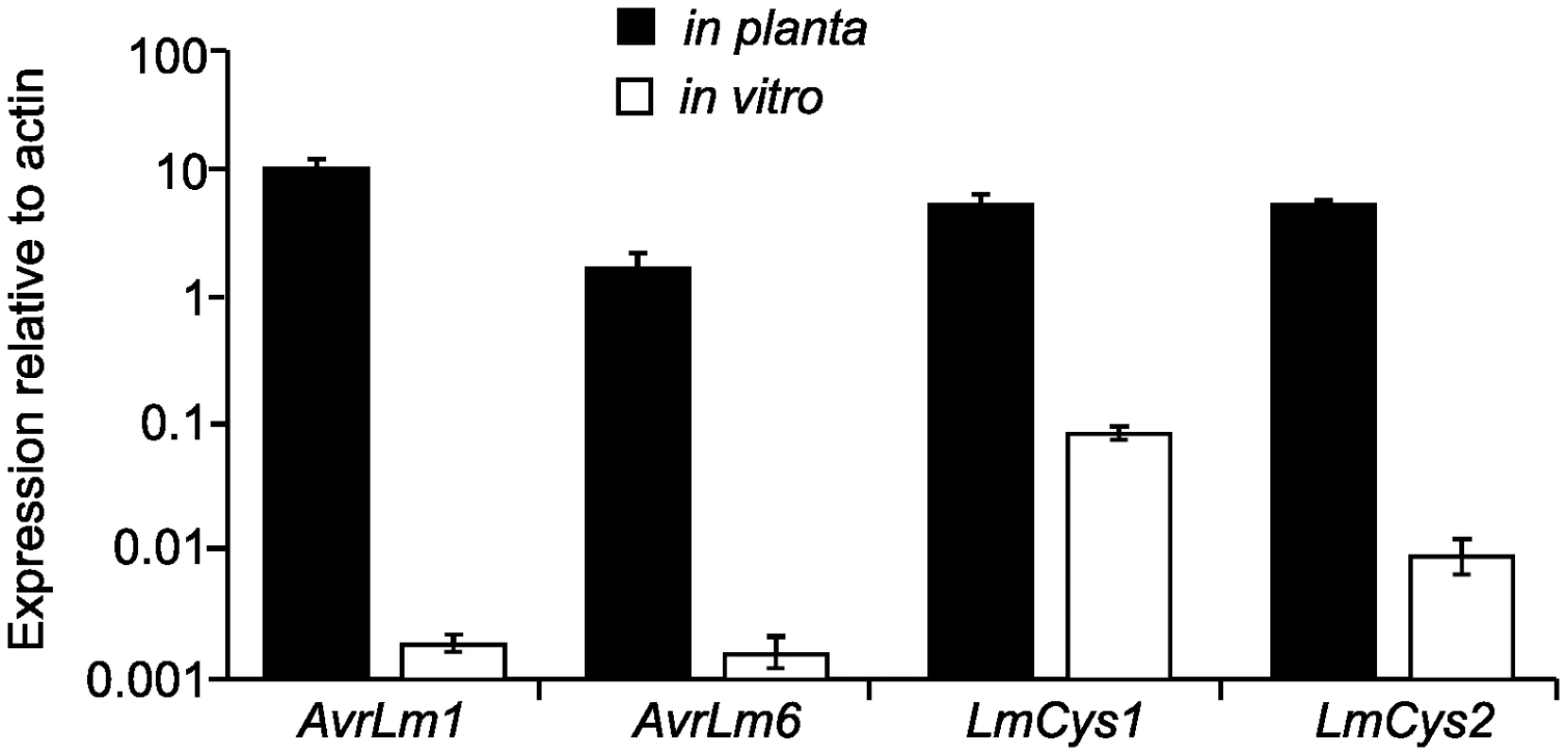

(A) Schematic representation of the AvrLm1-LmCys2 genomic region whereby highly-repetitive sequences with low GC content (red) flank single copy sections with high GC content (white). Four genes encoding small-secreted proteins, AvrLm1, AvrLm6, LmCys1 and LmCys2, were sequenced from 295 Australian isolates, whilst the remaining three genes and four non-coding, non-repetitive regions (NC1-4) were sequenced in 84 of the 295 isolates. Repeat-induced point (RIP) mutations were detected in AvrLm6, LmCys1, LmTrans and two non-coding, non-repetitive regions (NC3 and NC4) (black). (B) Location of single-copy sequences relative to the flanking repetitive regions. Within each of the two single copy regions(black) analysed, the frequency of RIP alleles and distribution of RIP mutations decreased in a 5′ to 3′gradient (arrows). The single copy region (149 bp) between NC3 and AvrLm6 was not analysed and so the gradient arrow is discontinuous. * denotes a repeat region (620 bp) directly upstream of NC3 that is highly RIP-affected. The predicted LmCys1 protein (220 aa) contained eight cysteine residues and its single match was to a ‘secreted in xylem’ Six1 effector (also known as Avr3) of Fusarium oxysporum (26% identity, 40% similarity, accession number CAE55870.1) [26]. The predicted LmCys2 protein (247 aa), also containing eight cysteine residues, had no matches within the NCBI database. Both LmCys1 and LmCys2 were predicted to be secreted with signal peptides of 19 and 18 aa, respectively. To determine whether LmCys1 and LmCys2 were expressed highly in planta, which would be expected of genes encoding effector-like proteins, quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) analyses were performed. Transcript levels of LmCys1 and LmCys2 in planta were six times higher than those of actin at seven days after inoculation of cotyledons of a susceptible B. napus cultivar (Figure 2). LmCys1 and LmCys2 were expressed at 0.1 and 0.01 times, respectively, that of actin in seven day in vitro cultures. Similar results were obtained with a second isolate (data not shown). This extremely high level of expression in planta compared to in vitro is similar to that seen for AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 (Figure 2) [8]. These characteristics (small cysteine-rich secreted proteins with no or few matches in databases and high in planta expression) strongly suggested that LmCys1 and LmCys2, like AvrLm1 and AvrLm6, encode effector-like proteins.

Fig. 2. Quantitative reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR analyses of AvrLm6, AvrLm1, LmCys1 and LmCys2.

At least 100 fold changes in expression were observed for each gene in planta compared to in vitro growth. RNA was prepared from seven day old cultures of isolates with the wild type alleles AvrLm6-0, AvrLm1-0, LmCys1-0 and LmCys2-0, which were growing in 10% V8 juice. Additionally RNA was prepared from cotyledons of B. napus cv. Beacon 7 dpi with the same isolates. Two isolates were used. Transcript levels of each gene were compared to those of L. maculans actin within each sample. Data points are the average expression of each gene relative to actin determined from the two isolates, and three technical replicates for each sample. Expression relative to actin is presented as a log scale (Y-axis). Standard errors are represented. The LmTrans protein (373 aa) contained a DDE superfamily endonuclease domain predicted to be involved in efficient DNA transposition, and its best match was a putative transposase from Stagonospora nodorum (61% identity, 68% similarity, accession number CAD32687.1). The predicted LmGT protein (414 aa) was a putative glycosyltransferase with best matches to hypothetical protein PTRG_04076 of Pyrenophora tritici-repentis (89% identity, 95% similarity, EDU46914.1). The LmMFS protein (591 aa) belonged to the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS). This protein had best matches to putative protein SNOG_04897 from S. nodorum (74% identity, 82% similarity, EAT87288.2).

Since LmCys1 and LmCys2 had effector-like properties and thus putative roles in the plant-fungal interaction, these genes were sequenced in the 295 isolates. Five and two alleles were detected for LmCys1 and LmCys2, respectively (Table 1), including the wild type alleles obtained from published BAC sequences. RIPCAL analysis showed that only one isolate, which was collected after the breakdown of sylvestris resistance had a RIP allele of LmCys1, and there were no deletion alleles, whereas there were no RIP alleles of LmCys2, but two isolates collected before breakdown of sylvestris resistance had a deletion of LmCys2 (Table 1). Overall, the frequencies of individual alleles ranged from 99% for LmCys2-0 to 0.3% for AvrLm1-4. The 295 isolates comprised 34 haplotypes based on alleles of AvrLm1, AvrLm6, LmCys1 and LmCys2 (Table S3).

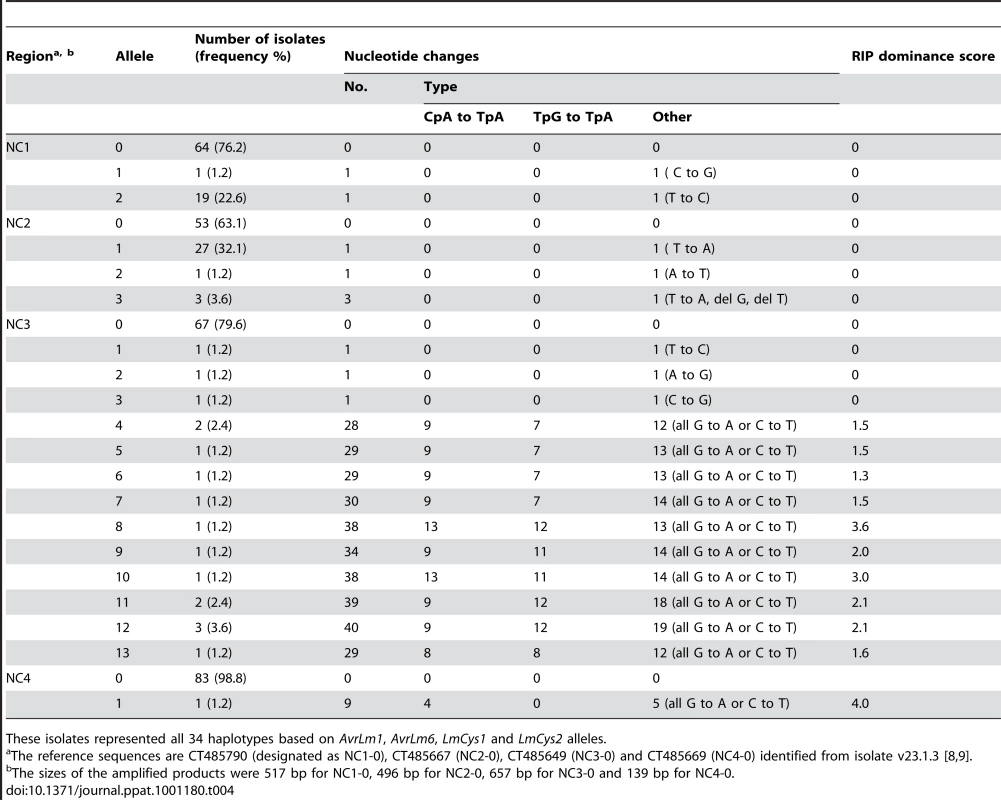

Four non-coding, non-repetitive regions (Figure 1A) ranging in size between 247 and 657 bp were analysed, to see whether single copy non-coding regions, like the single copy genes, were affected by RIP mutation. These regions and the three other genes LmTrans, LmGT and LmMFS in this region (Figure 1A) were sequenced in a subset of 84 of the 295 isolates, which included isolates representing all 34 haplotypes described above (Table S3). Three, four, 14 and two alleles were detected for NC1, NC2, NC3 and NC4, respectively, whilst two, one, and three alleles were detected for LmTrans, LmGT and LmMFS, respectively (Table 4 and Table S5). The mutations giving rise to the alleles of NC1, NC2 and LmMFS were single non-RIP-like nucleotide substitutions (both synonymous and non-synonymous), and single base pair deletions. No polymorphisms were detected in LmGT and no RIP alleles were detected for NC1, NC2, LmMFS or LmGT. A single isolate had RIP alleles for NC4 and LmTrans in addition to NC3, AvrLm6 and LmCys1. The NC3 region had an extremely high frequency of RIP mutation and the ten RIP alleles were all associated with AvrLm6 RIP alleles. Based on all seven genes and four non-coding regions, 51 haplotypes were identified among the 84 isolates (Table S6).

Tab. 4. Nucleotide changes in non-coding, non-repetitive regions within the AvrLm1-LmCys2 genomic region in Australian isolates of Leptosphaeria maculans.

These isolates represented all 34 haplotypes based on AvrLm1, AvrLm6, LmCys1 and LmCys2 alleles. Distribution and extent of RIP mutations

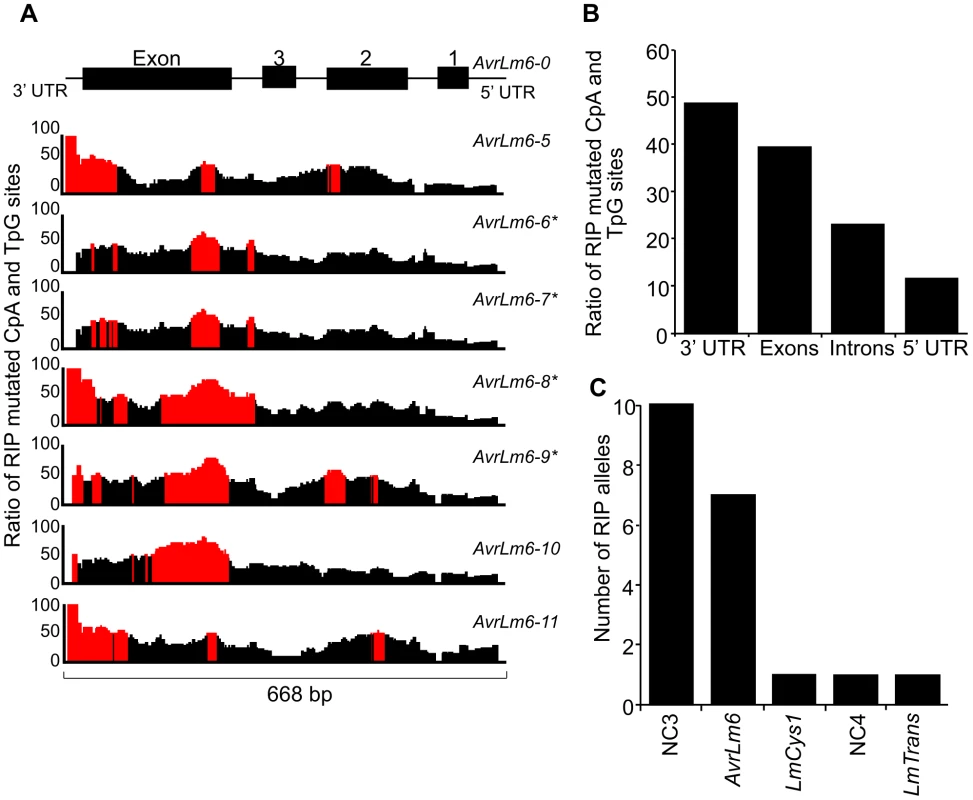

The distribution and degree of RIP mutation across each allele of each gene was determined. This was represented as a ratio of the number of mutated CpA and TpG sites relative to number of potential RIP sites in isolate v23.1.3 in a 100 bp rolling window. The seven RIP alleles of AvrLm6 had the highest frequency of RIP towards the 3′ end (Figure 3A). The frequency of RIP was higher within the 3′ UTR and the exons, than in the introns and 5′ UTR (Figure 3B). The ten RIP alleles of NC3 and single RIP allele of LmCys1 showed the highest frequency of RIP at their 5′ ends, whilst RIP mutations were evenly distributed throughout the single RIP allele of LmTrans (Figure S2), the latter gene being the furthest 3′ characterised single copy sequence affected by RIP mutation within the AvrLm1-LmCys2 genomic region (Figure 3C). The NC3-Avrlm6 and LmCys1-NC4-LmTrans single copy regions in which RIP mutations were detected, were separated by 37 kb of repetitive elements (Figure 1B). Both these single copy regions were closer to upstream repetitive elements (<342 bp) than to downstream repetitive elements (>1 kb) (Figure 1B). The degree of RIP within these single copy regions was proportional to their proximity to repetitive elements, and thus a gradient of RIP mutations was apparent in a 5′ to 3′ direction (Figures 1B and 3B).

Fig. 3. Distribution of RIP mutations across the AvrLm1-LmCys2 genomic region in Leptosphaeria maculans.

(A) The ratio of mutated CpA or TpG sites within the seven AvrLm6 RIP alleles compared to the number of available CpA and TpG nucleotides present in the wild type AvrLm6-0 allele over a 100 bp window. Regions where greater than 50% of potential RIP sites are mutated are highlighted in red. There is a higher proportion of RIP mutations towards the 5′ end of the region (3′ end of the AvrLm6 gene). AvrLm6-0, -1, -2, -3 and -4 alleles do not display RIP mutations. (B) The average ratio of RIP mutations within the untranslated regions (UTRs), exons and introns for the seven RIP alleles of AvrLm6 relative to the number of potential RIP sites in the wild type sequence. The 3′ UTR and exons are undergoing the highest frequency of RIP. (C) The number of RIP alleles for each of the genes and non-coding, non-repetitive (NC) regions analysed across the AvrLm1-LmCys2 genomic region in 84 isolates (see also Figure S2). The number of RIP alleles is highest for NC3 and decreases in the genes and non coding regions downstream, consistent with RIP occurring in a directional manner.* represent RIP alleles of AvrLm6 that are not transcribed and that confer a virulence phenotype on an Rlm6-containing cultivar. The remaining RIP alleles of AvrLm6 were not tested for virulence towards Rlm6. Since amongst these single copy regions the degree of RIP mutations was highest in NC3, a repeat region (620 bp) directly upstream was analysed to see if it was severely RIP-affected and thus might act as a point of ‘leakage’ of RIP into NC3 and AvrLm6 (Figure 1B). BLAST analysis of the genomic sequence of isolate v23.1.3 revealed 293 copies of this repeat. RIPCAL analysis showed that the repeat directly upstream of NC3 was amongst the most highly RIP-affected copy of that repeat in the genome.

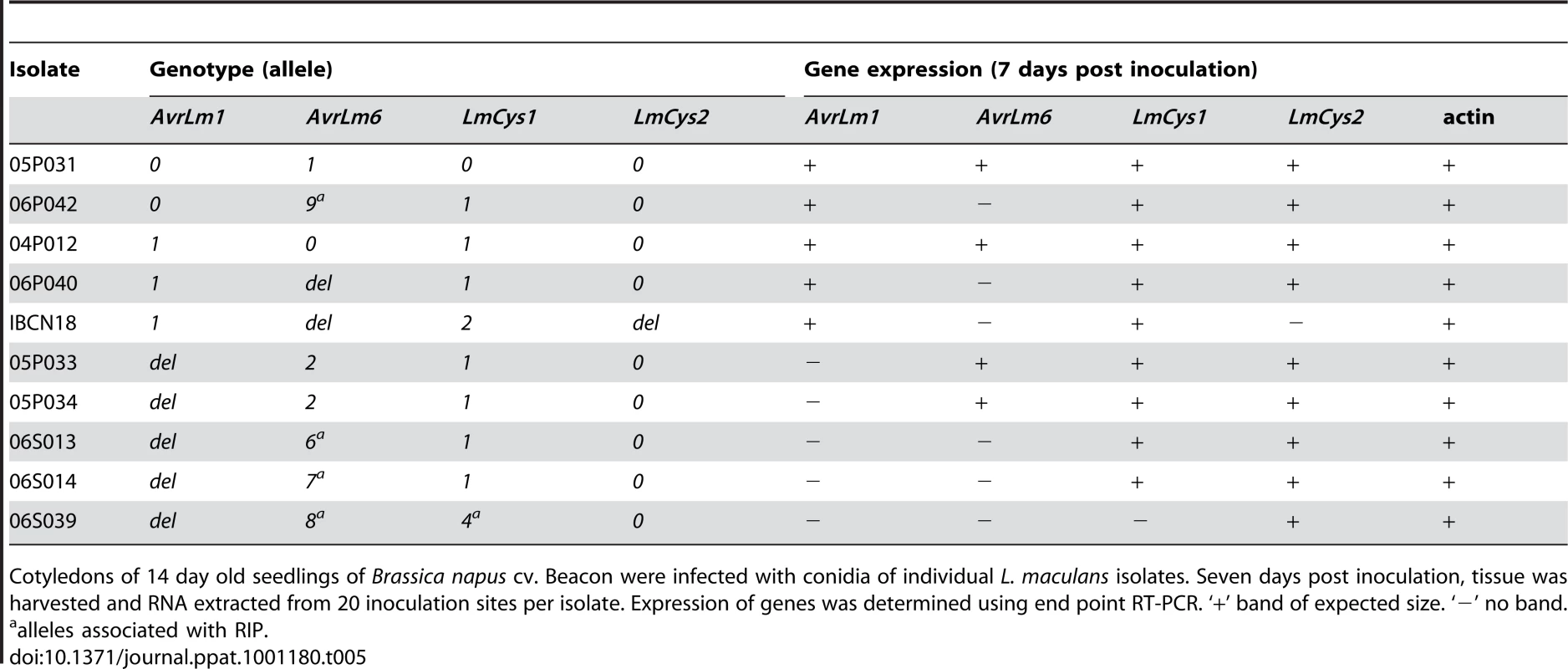

Transcription of AvrLm1, AvrLm6, LmCys1 and LmCys2 alleles

The mutations of AvrLm1, AvrLm6, LmCys1 and LmCys2 (deletions or RIP mutations including stop codons) would be expected to lead to lack of transcription of these alleles. This hypothesis was assessed in a range of isolates seven days after inoculation of cotyledons of B. napus cv. Beacon, which all the isolates could attack. Primers designed to amplify 500–700 bp products within the coding region of these genes were used in end-point RT-PCR (Table 5). Isolates with either AvrLm1-0 or AvrLm1-1 allele had an AvrLm1 transcript of the appropriate size. As expected, isolates with the deletion allele had no transcript. The AvrLm6-0, AvrLm6-1 or AvrLm6-2 alleles were expressed, whilst the RIP alleles, AvrLm6-6, AvrLm6-7, AvrLm6-8 or AvrLm6-9 were not. As expected, no expression of AvrLm6 or of LmCys2 was detected in isolates with the deletion alleles of these genes. Isolates with LmCys1-0, LmCys1-1 or LmCys1-2 alleles had an LmCys1 transcript, whilst the isolate with the RIP allele, LmCys1-4, did not. Actin transcripts were detected in all isolates.

Tab. 5. Expression analysis of AvrLm1, AvrLm6, LmCys1 and LmCys2 alleles in Leptosphaeria maculans isolates in planta.

Cotyledons of 14 day old seedlings of Brassica napus cv. Beacon were infected with conidia of individual L. maculans isolates. Seven days post inoculation, tissue was harvested and RNA extracted from 20 inoculation sites per isolate. Expression of genes was determined using end point RT-PCR. ‘+’ band of expected size. ‘−’ no band. Rate of mutations of genes

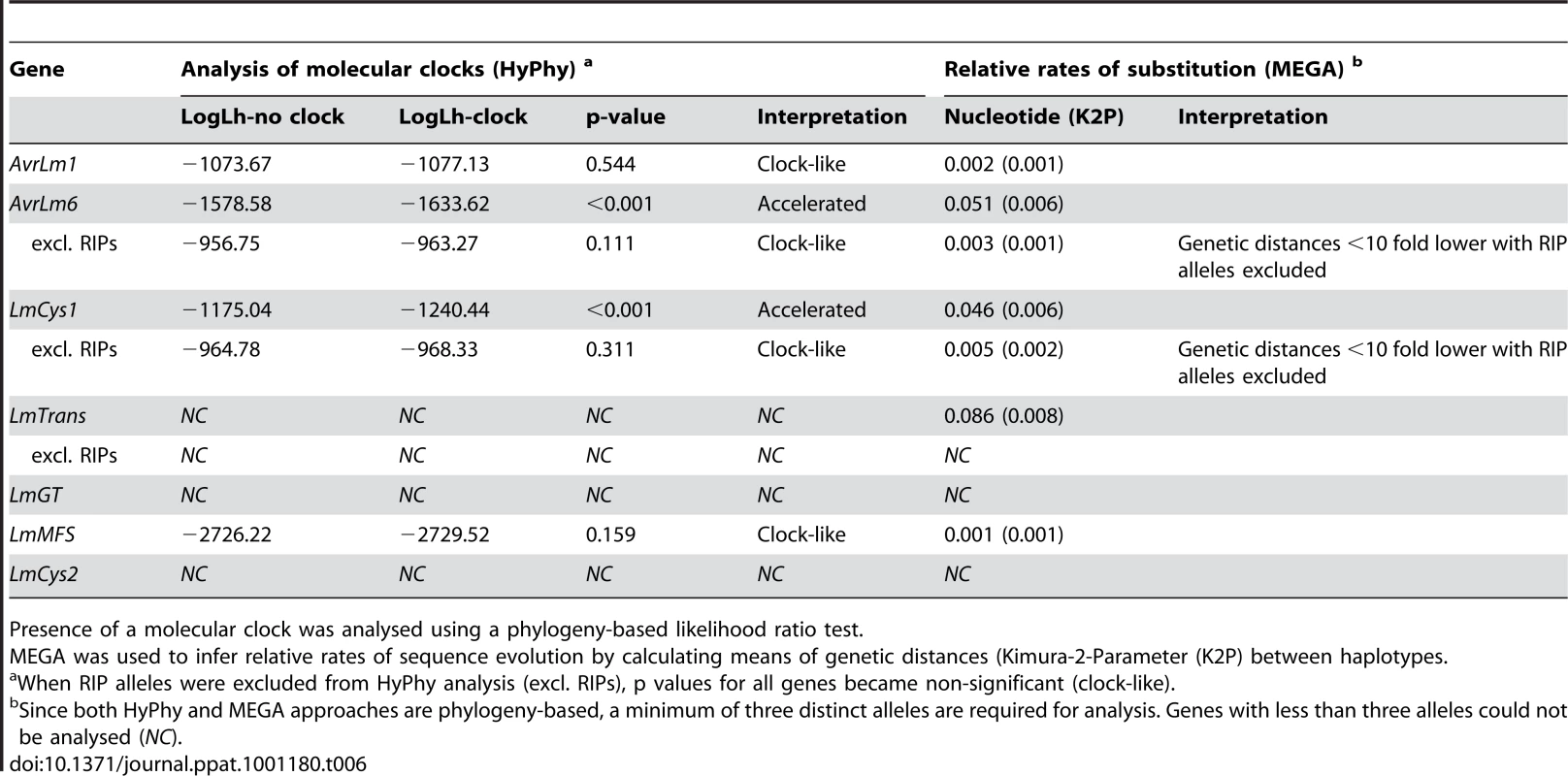

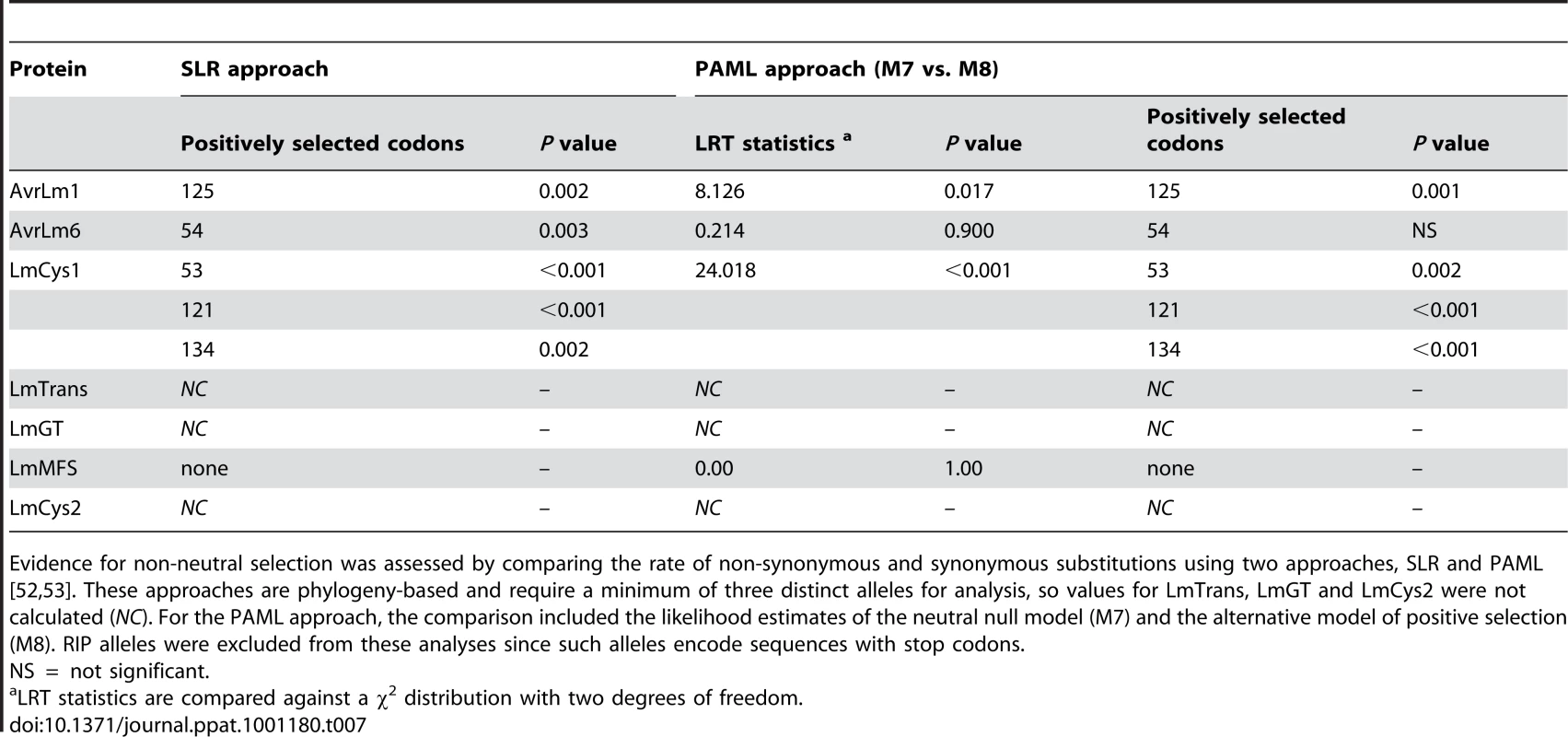

To determine the rates of mutations, genes were analysed by phylogeny-based likelihood ratio tests (LRT) implemented in the program HyPhy [27]. These tests suggested that nucleotides of AvrLm1 and LmMFS mutated at a constant rate, i.e. mutations did not deviate significantly (p = 0.544) from a clock-like rate of evolution. In contrast, an accelerated mutation rate was detected for AvrLm6 and LmCys1 loci (P<0.001) compared to expectations under constant (i.e. clock-like) evolution. However, when RIP alleles were excluded, mutations evolved at a clock-like rate (Table 6). Genetic divergence between haplotypes was calculated using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software [28]. Relative rates of sequence evolution of non-RIP alleles were much lower than those of RIP alleles (Table 6). To determine whether the seven proteins were undergoing positive selection, the rates of non-synonymous and synonymous substitutions were compared. All RIP alleles were excluded from this analysis since they contained multiple stop codons. Evolution of codon changes within AvrLm1 and LmCys1 was best explained by a model of positive selection, as shown by a likelihood ratio test implemented using two complementary approaches, the sitewise likelihood-ratio (SLR) and phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood (PAML) methods (Table 7). This interpretation was supported by the finding of positive selection at a single codon site in AvrLm1 and at three sites in LmCys1 (Table 7). Analysis of the AvrLm6 protein using the SLR approach suggested a single amino acid (codon 54) may be undergoing positive selection; however, this finding was not supported by the PAML analysis. Similar analyses could not be performed on LmCys2, LmGT or LmTrans as these genes had fewer than three alleles.

Tab. 6. Analysis for the presence of a molecular clock, and relative rates of sequence evolution for genes within the AvrLm1-LmCys2 genomic region of Leptosphaeria maculans.

Presence of a molecular clock was analysed using a phylogeny-based likelihood ratio test. Tab. 7. Analysis of positive selection on amino acids of proteins encoded within the AvrLm1-LmCys2 genomic region of Leptosphaeria maculans.

Evidence for non-neutral selection was assessed by comparing the rate of non-synonymous and synonymous substitutions using two approaches, SLR and PAML [52], [53]. These approaches are phylogeny-based and require a minimum of three distinct alleles for analysis, so values for LmTrans, LmGT and LmCys2 were not calculated (NC). For the PAML approach, the comparison included the likelihood estimates of the neutral null model (M7) and the alternative model of positive selection (M8). RIP alleles were excluded from these analyses since such alleles encode sequences with stop codons. Evolution and phylogenetic relationships of RIP and deletion alleles

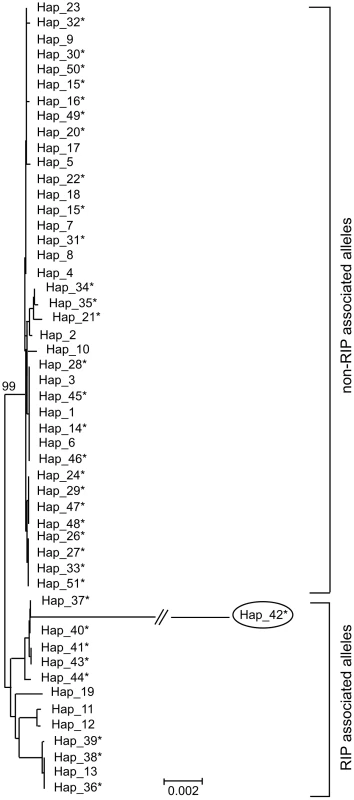

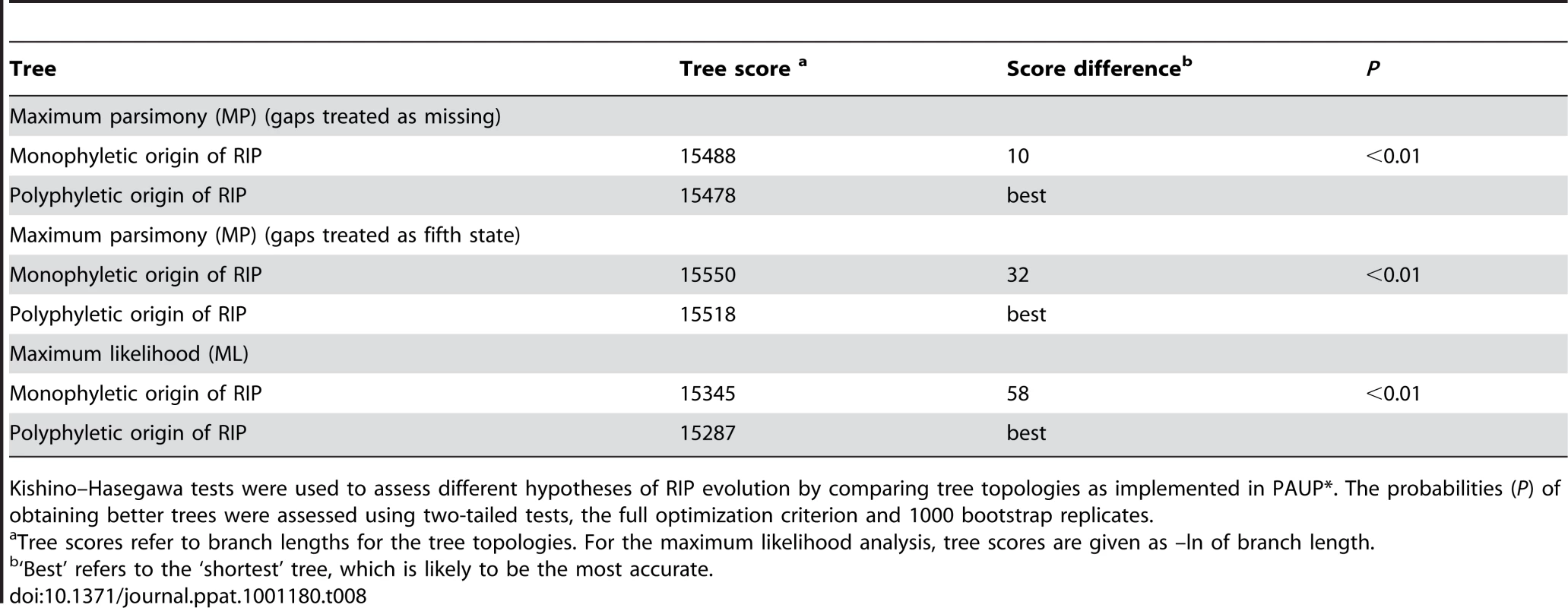

Two hypotheses for the evolution of RIP alleles, monophyly (having a single origin or having evolved only once) and polyphyly (multiple origins or having evolved several times independently) were tested by comparing tree topologies using the Kishino–Hasegawa (KH) test [29]. For both the Maximum Parsimony (MP) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) approach, trees based on the assumption of a monophyletic origin of RIP alleles performed significantly better than those based on polyphyletic origin (Table 8). The phylogenetic relationship of all detected haplotypes is depicted in Figure 4. The RIP and non-RIP associated alleles form two distinct clusters, supporting the hypothesis of a single origin of RIP alleles. In contrast, haplotypes associated with gene deletions are associated with multiple clades of the tree and have probably arisen several times.

Fig. 4. Genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships between haplotypes of Leptosphaeria maculans.

Un-rooted strict consensus of 1000 ML trees (-ln L = 16381.75) constructed from the concatenated DNA sequences of the seven genes and four non-coding, non-repetitive regions of the AvrLm1-LmCys2 genomic region. All CpA to TpA and TpG to TpA nucleotide changes were removed from the data set prior to analysis. Haplotypes (see Table S6) associated with RIP alleles cluster in a distinct clade with high bootstrap support (99%), suggesting a single origin. In contrast, haplotypes related to deletion alleles (*) are associated with multiple clades suggesting multiple origins. Note that RIP associated alleles have much longer branches (i.e. larger genetic distance) due to an accelerated evolution compared to non-RIP alleles (see Table 6). Haplotype 42 (circled) has RIP alleles at five of the loci examined (NC3, AvrLm6, LmCys1, NC4 and LmTrans), resulting in an exceptionally long branch. Tab. 8. Hypothesis-testing of multiple (polyphyletic) vs. single (monophyletic) origin of RIP mutation-associated haplotypes of Leptosphaeria maculans.

Kishino–Hasegawa tests were used to assess different hypotheses of RIP evolution by comparing tree topologies as implemented in PAUP*. The probabilities (P) of obtaining better trees were assessed using two-tailed tests, the full optimization criterion and 1000 bootstrap replicates. Discussion

Selection pressure on frequencies of AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 alleles is imposed by extensive sowing of cultivars with Rlm1 resistance

Breakdown of disease resistance has been observed in other plant fungal pathogen systems where fungal populations evolve rapidly (for review see [30]). In the canola - L. maculans interaction described here, strong selection pressure was exerted on the AvrLm1 locus, due to extensive sowing of sylvestris cultivars with Rlm1, which was consistent with the finding of a rapid increase in the frequency of isolates with virulent (avrLm1) alleles after the breakdown of resistance. Surprisingly the frequency of isolates virulent (with the avrLm6 allele) towards Rlm6 increased, although cultivars with polygenic or with sylvestris resistance have not been shown to contain Rlm6 [17], [31]. The linkage and genomic location of AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 may have led to a selective sweep whereby selection at AvrLm1 affected the frequency of avrLm6 alleles through ‘hitchhiking’. Thus strong selection imposed by wide-spread deployment of a plant resistance gene that favors a complementary effector allele in a pathogen could affect evolution of closely-linked effector genes. It is intriguing that in France recurrent sowing of Rlm6-containing cultivars in localised field trials led to an increase in avrLm6 isolates and a corresponding increase in isolates avirulent at the AvrLm1 locus [19]. This difference may be due to the different targets of selection pressure - Rlm6 in France and Rlm1 in our study.

This situation whereby selection pressure on one gene affected allele frequencies of another may be partly due to the presence of these two effector genes in a repeat-rich region, where there is a low recombination frequency. Effectors in other fungi are present in repeat-rich regions. In the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae, avirulence gene Avr-Pita is located 48 bp from telomere repeats whilst Avr1-CO39 is associated with transposable elements [32], [33]. An avirulence gene (SIX1) of Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. lycopersici is flanked by transposable elements [34] and other effectors are localised on a single, transposon-rich chromosome [35]. Toxin-encoding genes, Tox3 and ToxA, are located next to repetitive elements in Stagonospora nodorum [36], [37], [38] and effectors are in repeat-rich regions of the genome of the oomycete, Phytophthora infestans [39]. In the sequenced isolate of L. maculans, AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 are located amongst multiple copies of long terminal repeat retrotransposons, namely Pholy, Olly, Polly and Rolly, which are generally incomplete. Furthermore the distribution and number of these elements within this genomic location varies considerably between isolates [20], [22]. The presence of effector genes within such regions is suggested to promote their adaptation and diversification when exposed to strong selection pressure [40]. Rep and Kistler have speculated that the presence of highly repetitive regions containing transposons, may promote mutation of resident effector genes [41].

Repeat-induced point mutations may be ‘leaking’ from adjacent inactivated transposable elements into single copy regions

The genes and non-coding regions undergoing RIP within the AvrLm1 - LmCys2 gene region are single copy and therefore are not expected to be targeted by RIP. Two explanations for the presence of RIP mutations in these genes are as follows. Firstly, if these genes are the result of an ancestral duplication, RIP mutation may be acting directly on them. However, Fudal et al showed that no closely related paralogs of AvrLm6 exist in the genome of isolate v23.1.3 suggesting that RIP would not be targeting these sequences due to a duplication event [22]. Alternatively, the AvrLm6 locus may be completely or partially duplicated in isolates where RIP was detected. However, southern hybridisations suggest only a single copy of the Avrlm6 locus in isolates where RIP was detected, which does not support the possibility of RIP being targeted to this locus. A more likely explanation is that RIP mutations ‘leak’ from adjacent repetitive sequences. As RIP mutation is traditionally observed to be restricted to repetitive regions and not single copy regions, leakage of RIP mutation might occur within a relatively short distance of a RIP-affected repeat, as suggested by Fudal et al [22]. Indeed, this has been reported in N. crassa whereby leakage of RIP was detected in single copy sequences at least 930 bp from the boundary of neighbouring duplicated sequences [42]. This is consistent with our finding of a high frequency of RIP mutations in single copy regions of L. maculans with the degree of RIP mutation being proportional to the proximity of flanking repetitive elements. The potential ‘leakage’ of RIP mutations into closely linked effector genes highlights the power of this process to lead to major evolutionary changes to genes such as effectors that play an important role in the lifestyle of an organism.

Deletion alleles of AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 had multiple origins whilst RIP alleles had a single origin

All haplotypes associated with RIP alleles of AvrLm6 and LmCys1 appeared to have a single origin indicating that the event that led to the RIP occurred only once. Furthermore, haplotypes associated with the virulent AvrLm6-2 allele (cysteine substitution) arose as a single clade. These single origins suggest that events leading to both the RIP mutations and non-RIP amino acid substitutions are much rarer than those leading to the deletion mutations. The RIP event occurred after the breakdown of sylvestris resistance, as isolates with RIP mutations were not detected before this time. This rapid appearance of RIP mutations is not unprecedented; such mutations have been shown to occur after one generation in L. maculans. When transformants with several tandemly linked copies of a hygromycin resistance gene were crossed with a wild type strain, none of the progeny were resistant to hygromycin due to the presence of multiple stop codons generated by RIP mutations in the hygromycin resistance gene [43].

Mutations associated with resistance to azole fungicides in Mycosphaerella graminicola also are derived from a single origin. Resistance emerged only once following strong selection due to widespread use of azole fungicides [44]. In both the M. graminicola and L. maculans examples, a similar phylogeny was found despite differences in origin and type of evolutionary pressure. In L.maculans haplotypes associated with deletion alleles conferring virulence towards AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 appeared to have a polyphyletic origin. Isolates with these deletions were detected prior to 2004 when the resistance breakdown occurred, albeit at a much lower frequency than afterwards. Haplotypes associated with deletion of both AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 might have been derived directly from the ancestral wild type rather than via the deletion of one gene followed by that of the second.

Deletions, non-synonymous and RIP mutations can confer virulence

Deletions, RIP mutations and non-RIP amino acid substitutions conferred virulence at the AvrLm6 locus, whilst only deletions were responsible for virulence at the AvrLm1 locus. Similar types of mutations were detected in French populations of L. maculans isolates [22]. The finding of a virulence allele of AvrLm6 arising from a non-synonymous, non-RIP like mutation, of a glycine to cysteine substitution, was intriguing. In other avirulence proteins the loss rather than the gain of cysteine through non-synonymous substitutions confers virulence. For example, in the AVR4 protein of Cladosporum fulvum, loss of cysteine residues renders the isolate virulent towards tomato cultivars with the corresponding Cf-4 resistance gene [45]. The AvrLm6-2 allele of L. maculans gives rise to a protein with seven rather than six cysteine residues in the protein encoded by AvrLm6-0. This latter protein is proposed to have two disulphide bridges between C109 and C130, and C103 and C122 [8] on the basis of the SCRATCH disulphide bond prediction program [46]. The program predicts that the presence of the additional cysteine (C123) in the AvrLm6-2 allele would result in a third disulphide bridge, between C26 and C123.

As well as the mechanisms leading to inactivation of alleles described above, some of the proteins were undergoing non-RIP amino acid substitutions which did not lead to a change in phenotype. Some of these mutations, in AvrLm1 and LmCys1, were the results of positive selection, which favours new mutations that confer a fitness advantage and thus lead to an increase in gene diversity [12], [47]. Positive selection has been detected in pathogen effector genes including the avirulence gene that encodes NIP in Rhynchosporium secalis [47] and in genes encoding host-specific toxins such as S. nodorum ToxA [36], [48]. In contrast to AvrLm1, AvrLm6 and LmCys1, the remaining genes in the 520 kb AT - rich region, including LmCys2 showed very little variation. Despite positive selection driving amino acid substitutions within some of the effector-like proteins, deletion and RIP mutations are by far the major mechanisms leading to virulence at the AvrLm1 and AvrLm6 loci.

Materials and Methods

Brassica cultivars and Leptosphaeria maculans isolates

Stubble of cultivars of B. napus and B. juncea infested with L. maculans was collected each year from 1997 to 2008 from 25 locations across Australia (Table S1). For instance, stubble from a crop sown in 2003 was collected from the field in 2004 and isolates were then cultured from it. Cultivars with ‘polygenic’ resistance (Beacon, Dunkeld, Emblem, Grace, Hyden, Jade, Pinnacle, Skipton, Pinnacle and Tornado TT) had one or more Rlm genes, but none had Rlm1 nor Rlm6. The identity of resistance genes in some of these cultivars has been reported [44]. The category of ‘sylvestris resistance’ refers to cultivars (Surpass 400, Surpass 501TT, Surpass 603CL, 45Y77 and 46Y78) with resistance derived from B. rapa spp. sylvestris [14] have Rlm1 and RlmS [17]. The category of ‘juncea’ resistance refers to cultivars and lines of B. juncea (cv. Dune and lines JC05002, JC05006 and JC05007). Stubble of the latter two categories was not collected prior to 2004. From 2004 onwards although cultivars with sylvestris resistance were withdrawn from sale, these lines were grown in yield trials across Australia, and stubble was collected from them. Isolates (287) were cultured from individual ascospores discharged from stubble collected the previous year as described previously [15]. In addition, eight Australian isolates collected in 1987 and 1988 were analysed. All isolates were maintained on 10% Campbell's V8 juice agar.

Virulence testing

Virulence of a subset of isolates was tested on three B. napus and one B. juncea cultivars. The B. napus cv. Beacon and cv. Q2 are susceptible controls that all isolates could attack. Cultivar Columbus contains Rlm1 and Rlm3 and B. juncea cv. Aurea contains Rlm5 and Rlm6 [3]. No Rlm1-only or Rlm6-only cultivars were available. Cotyledons of 14-day old seedlings were wounded and inoculated with conidia of individual isolates representing different haplotypes for AvrLm1 and AvrLm6. Symptoms were assessed at 10, 14 and 17 days post-inoculation (dpi) and pathogenicity scores determined at 17 dpi by scoring lesions on a scale from 0 (no darkening around wounds) to 9 (large grey-green lesions with profuse sporulation). Mean pathogenicity scores (determined from 40 inoculation sites) ≤3.9 were assigned as an avirulent phenotype whilst scores ≥4.0 were assigned as a virulent phenotype [17].

Gene identification and primer design

Non-coding, non-repetitive regions in the AvrLm1-LmCys2 genomic region and genes 3′ of AvrLm6 (Figure 1) were identified using published information [22] and by BLAST searches. Primers were designed upstream and downstream of start and stop codons to allow analysis of the sequences of entire open reading frames. For transcriptional analyses, primers were designed to amplify a 500–700 bp region of the coding sequence, flanking an intron where possible. All primers were designed using the program Primer3 [49] (Table S7). Primers to amplify the mating type locus and actin have been described previously [8], [24].

The sequence information for all genes has been deposited in GenBank with the following accession numbers; AvrLm1, AM084345 [1], AvrLm6, AM259336 [2], LmCys1, GU332625, LmTrans, GU332626, LmGT, GU332627, LmMFS, GU332628 and LmCys2, GU332629.

Allele genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from mycelia. Conditions for all PCR experiments were 95°C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 59°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 1 min; 72°C for 6 min. PCR products were purified using QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and sequenced using BigDyeTM terminator cycling conditions. Sequences were analysed using Sequencher v 4.0.5. Deletion genotypes were assigned if no band was produced following amplification with the AvrLm1, AvrLm6 or LmCys2-specific primers. Amplification of the mating type locus was a positive control for DNA quality. In a subset of eight isolates, deletion alleles were confirmed by Southern analysis of genomic DNA that had been digested with HindIII and hybridised with the appropriate probe (Figure S1). Additionally, PCR screens were performed on genomic DNA from two (for LmCys2) to 25 (for AvrLm6) isolates using multiple primer sets that amplify specific regions of the AvrLm1, AvrLm6 and LmCys2 gene regions. These amplifications confirmed that the entire locus was deleted in all isolates tested (data not shown).

Allele sequences were analysed by RIPCAL for the presence of RIP mutations [25]. RIPCAL generates a RIP dominance score, which is the frequency of the dominant dinucleotide RIP mutation (in this case CpA→TpA) relative to the sum of the alternative mutations (CpC→TpC, CpG→TpG and CpT→TpT). Sequences with RIP dominance scores >1 are considered to be highly RIP-affected. The ‘model’ sequence used for all RIPCAL analyses was the ‘wild type’ allele (designated with a -0 suffix) from the isolate (v23.1.3) whose genome has been sequenced. The spatial distribution of RIP was assessed for each gene and four non-coding regions by comparing the ratio of mutated CpA or TpG sites detected by RIPCAL, relative to the number of available CpA and TpG nucleotides present within the wild type allele over a 100 bp rolling window.

Expression analysis

Ten infected cotyledons of B. napus cv. Beacon were harvested at 7 dpi. Necrotic tissue surrounding the inoculation wounds of each cotyledon was harvested using a hole punch (diameter 8 mm). Total RNA was purified from this tissue using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) and was treated with DNaseI (Invitrogen) before cDNA was synthesized using a first strand cDNA synthesis kit and an oligo-dT primer. End point RT-PCR was used to assess expression of AvrLm1, AvrLm6, LmCys1, LmCys2 and actin.

Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine levels of expression of AvrLm1, AvrLm6, LmCys1 and LmCys2 in planta and in vitro culture. RNA was prepared from seven day old cultures of isolates with the wild type alleles of these genes, which were growing in 10% V8 juice. Additionally RNA was prepared from cotyledons of B. napus cv. Beacon 7 dpi infected with isolates with the wild type alleles of these genes. Total RNA and cDNA synthesis was performed as described above. Controls lacking reverse transcriptase were included. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using Rotor-Gene 3000 equipment (Corbett Research, Australia) and QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (QIAgen). A standard curve of amplification efficiency of each gene was generated from purified RT-PCR products [50]. Diluted RT product (1 μl) was added to 19 μl of PCR mix and subjected to 40 cycles of PCR (30 s at 94°C, then 60°C and then 72°C). All samples were analysed in triplicate. The amplified product was detected every cycle at the end of the 72°C step. Melt curve analysis after the cycling confirmed the absence of non-specific products in the reaction. The fluorescence threshold (Ct) values were determined for standards and samples using the Rotor-Gene 5 software. Ct values were exported to Microsoft Excel and analysed [51]. Actin was used as a reference gene.

Phylogenetic analyses

Deviation from a constant rate of molecular evolution within the data sets (i.e. a “molecular clock”) was assessed using the phylogeny-based likelihood ratio test (LRT) implemented in the program HyPhy [27]. To estimate the contribution of the RIP alleles, likelihoods were calculated both for the total data sets and for data sets excluding RIP alleles. MEGA was also used to infer relative rates of sequence evolution by calculating means of genetic distances (Kimura-2-Parameter) between haplotypes.

Evidence for non-neutral evolution was assessed using two complementary approaches by comparing the rate of non-synonymous substitutions with the rate of synonymous substitutions (dN/dS = ω). Firstly, the analysis was based on the “sitewise likelihood-ratio” method as implemented in the SLR software package [52]. The test consists of performing a likelihood-ratio test on a site-wise basis, testing the null model (neutrality, ω = 1) against an alternative model ω≠1 (i.e. purifying selection ω<1; positive selection ω>1). Secondly, dN/dS = ω was tested using a phylogenetic analysis based on maximum likelihood as implemented in the PAML software package [53]. Two codon substitution models were compared via likelihood ratio tests (LRT). The comparison included the likelihood estimates of the neutral null model (M7) and the alternative model of positive selection (M8). RIP alleles were excluded from these analyses since such alleles encode sequences with stop codons.

To test different hypotheses of emergence of haplotypes associated with RIP alleles (Table S6), tree topologies using concatenated DNA sequences of all the genes (AvrLm1, AvrLm6, LmCys1, LmTrans, LmGT, LmMFS and LmCys2) and non-coding, non-repetitive regions (NC1-4) were generated and compared using the Kishino–Hasegawa (KH) test [29] as implemented in PAUP* 4.0b 10. Since the RIP mechanism produces the same mutations at specific sites, it is likely that formerly unrelated nucleotide sequences converge, leading to the false impression of similarity due to common descent. To avoid this bias, all CpA to TpA and TpG to TpA nucleotide changes were removed from the data set prior to inferring the phylogenetic relationships of haplotypes. Two alternative hypotheses were then compared; (i) haplotypes containing RIP alleles were monophyletic, i.e. they emerged only once. Trees representing this hypothesis were “constrained” by restricting RIP alleles to cluster only amongst each other (ii) haplotypes containing RIP alleles were polyphyletic, i.e. they emerged several times independently. Trees representing this alternative hypothesis were “unconstrained”, i.e. the pairing of particular alleles in the topology was not restricted. One thousand trees were generated representing each hypothesis, and the probabilities (P) of obtaining better trees were assessed using two-tailed tests, the full optimization criterion and 1000 bootstrap replicates. The KH test was conducted for trees constructed under the maximum likelihood and the maximum parsimony criterion.

The phylogenetic relationship among isolates based on the concatenated DNA sequences of all genes and non-coding, non-repetitive regions was assessed by PAUP* using maximum likelihood. Tree searches were conducted with the “fast-stepwise-addition” option and 1000 bootstrap replicates to assess statistical significance of nodes. The GTR-model with estimated substitution-rate matrix was used to evaluate molecular rate constancy.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. FittBDL

BrunH

BarbettiMJ

RimmerSR

2006 World-wide importance of phoma stem canker (Leptosphaeria maculans and L. biglobosa) on oilseed rape (Brassica napus). Eur J Plant Pathol 114 3 15

2. FlorHH

1955 Host-parasite interactions in flax rust - its genetic and other implications. Phytopathology 45 680 685

3. BalesdentMH

AttardA

KuhnML

RouxelT

2002 New avirulence genes in the phytopathogenic fungus Leptosphaeria maculans. Phytopathology 92 1122 1133

4. YuF

LydiateDJ

RimmerSR

2005 Identification of two novel genes for blackleg resistance in Brassica napus. Theor Appl Genet 110 969 979

5. DelourmeR

ChevreAM

BrunH

RouxelT

BalesdentMH

2006 Major gene and polygenic resistance to Leptosphaeria maculans in oilseed rape (Brassica napus). Eur J Plant Pathol 114 41 52

6. YuF

LydiateDJ

RimmerSR

2008 Identification and mapping of a third blackleg resistance locus in Brassica napus derived from B. rapa subsp. sylvestris. Genome 51 64 72

7. RouxelT

BalesdentMH

2005 The stem canker (blackleg) fungus, Leptosphaeria maculans, enters the genomic era. Mol Plant Pathol 6 225 241

8. FudalI

RossS

GoutL

BlaiseF

KuhnML

2007 Heterochromatin-like regions as ecological niches for avirulence genes in the Leptosphaeria maculans genome: map-based cloning of AvrLm6. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20 459 470

9. GoutL

FudalI

KuhnML

BlaiseF

EckertM

2006 Lost in the middle of nowhere: the AvrLm1 avirulence gene of the Dothideomycete Leptosphaeria maculans. Mol Microbiol 60 67 80

10. ParlangeF

DaverdinG

FudalI

KuhnML

BalesdentMH

2009 Leptosphaeria maculans avirulence gene AvrLm4-7 confers a dual recognition specificity by the Rlm4 and Rlm7 resistance genes of oilseed rape, and circumvents Rlm4-mediated recognition through a single amino acid change. Mol Microbiol 71 851 863

11. HogenhoutSA

Van der HoornRA

TerauchiR

KamounS

2009 Emerging concepts in effector biology of plant-associated organisms. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 22 115 122

12. StukenbrockEH

McDonaldBA

2009 Population genetics of fungal and oomycete effectors involved in gene-for-gene interactions. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 22 371 380

13. SpragueSJ

BalesdentMH

BrunH

HaydenHL

MarcroftSJ

2006 Major gene resistance in Brassica napus (oilseed rape) is overcome by changes in virulence of populations of Leptosphaeria maculans in France and Australia. Eur J Plant Pathol 114 33 44

14. CrouchJH

LewisBG

MithenRF

1994 The effect of A genome substitution on the resistance of Brassica napus to infection by Leptosphaeria maculans. Plant Breeding 112 265 278

15. SpragueSJ

MarcroftSJ

HaydenHL

HowlettBJ

2006 Major gene resistance to blackleg in Brassica napus overcome within three years of commercial production in southeastern Australia. Plant Disease 90 190 198

16. Van de WouwAP

StonardJF

HowlettBJ

WestJS

FittBD

2010 Determining frequencies of avirulent alleles in airborne Leptosphaeria maculans inoculum using quantitative PCR. Plant Pathology 59 809 818

17. Van de WouwAP

MarcroftSJ

BarbettiMJ

HuaL

SalisburyPA

2009 Dual control of avirulence in Leptosphaeria maculans towards a Brassica napus cultivar with ‘sylvestris-derived’ resistance suggests involvement of two resistance genes. Plant Pathology 58 305 313

18. RouxelT

PenaudA

PinochetX

BrunH

GoutL

2003 A 10-year survey of populations of Leptosphaeria maculans in France indicates a rapid adaptation towards the Rlm1 resistance gene of oilseed rape. Eur J Plant Pathol 109 871 881

19. BrunH

ChevreAM

FittBD

PowersS

BesnardAL

2010 Quantitative resistance increases the durability of qualitative resistance to Leptosphaeria maculans in Brassica napus. New Phytol 185 285 299

20. GoutL

KuhnML

VincenotL

Bernard-SamainS

CattolicoL

2007 Genome structure impacts molecular evolution at the AvrLm1 avirulence locus of the plant pathogen Leptosphaeria maculans. Environ Microbiol 9 2978 2992

21. SelkerEU

GarrettPW

1988 DNA sequence duplications trigger gene inactivation in Neurospora crassa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 85 6870 6874

22. FudalI

RossS

BrunH

BesnardAL

ErmelM

2009 Repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) as an alternative mechanism of evolution toward virulence in Leptosphaeria maculans. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 22 932 941

23. BrunH

LevivierS

SomdaI

RuerD

RenardM

2000 A field method for evaluating the potential durability of new resistance sources: application to the Leptosphaeria maculans-Brassica napus pathosystem. Phytopathology 90 961 966

24. CozijnsenAJ

HowlettBJ

2003 Characterisation of the mating-type locus of the plant pathogenic ascomycete Leptosphaeria maculans. Curr Genet 43 351 357

25. HaneJK

OliverRP

2008 RIPCAL: a tool for alignment-based analysis of repeat-induced point mutations in fungal genomic sequences. BMC Bioinformatics 9 478

26. RepM

van der DoesHC

MeijerM

van WijkR

HoutermanPM

2004 A small, cysteine-rich protein secreted by Fusarium oxysporum during colonization of xylem vessels is required for I-3-mediated resistance in tomato. Mol Microbiol 53 1373 1383

27. PondSL

FrostSD

MuseSV

2005 HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics 21 676 679

28. TamuraK

DudleyJ

NeiM

KumarS

2007 MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 24 1596 1599

29. KishinoH

HasegawaM

1989 Evaluation of the maximum likelihood estimate of the evolutionary tree topologies from DNA sequence data, and the branching order in hominoidea. J Mol Evol 29 170 179

30. McDonaldBA

LindeC

2002 Pathogen population genetics, evolutionary potential, and durable resistance. Annu Rev Phytopathol 40 349 379

31. RouxelT

WillnerE

CoudardL

BalesdentMH

2003 Screening and identification of resistance to Leptosphaeria maculans (stem canker) in Brassica napus accessions. Euphytica 133 219 231

32. CouchBC

FudalI

LebrunMH

TharreauD

ValentB

2005 Origins of host-specific populations of the blast pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae in crop domestication with subsequent expansion of pandemic clones on rice and weeds of rice. Genetics 170 613 630

33. FarmanML

EtoY

NakaoT

TosaY

NakayashikiH

2002 Analysis of the structure of the AVR1-CO39 avirulence locus in virulent rice-infecting isolates of Magnaporthe grisea. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 15 6 16

34. RepM

2005 Small proteins of plant-pathogenic fungi secreted during host colonization. FEMS Microbiol Lett 253 19 27

35. MaLJ

van der DoesHC

BorkovichKA

ColemanJJ

DaboussiMJ

2010 Comparative genomics reveals mobile pathogenicity chromosomes in Fusarium. Nature 464 367 373

36. FriesenTL

StukenbrockEH

LiuZ

MeinhardtS

LingH

2006 Emergence of a new disease as a result of interspecific virulence gene transfer. Nat Genet 38 953 956

37. LiuZ

FarisJD

OliverRP

TanKC

SolomonPS

2009 SnTox3 acts in effector triggered susceptibility to induce disease on wheat carrying the Snn3 gene. PLoS Pathog 5 e1000581

38. HaneJK

LoweRG

SolomonPS

TanKC

SchochCL

2007 Dothideomycete plant interactions illuminated by genome sequencing and EST analysis of the wheat pathogen Stagonospora nodorum. Plant Cell 19 3347 3368

39. HaasBJ

KamounS

ZodyMC

JiangRH

HandsakerRE

2009 Genome sequence and analysis of the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Nature 461 393 398

40. FarmanML

2007 Telomeres in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae: the world of the end as we know it. FEMS Microbiol Lett 273 125 132

41. RepM

KistlerHC

2010 The genomic organization of plant pathogenicity in Fusarium species. Curr Opin Plant Biol 13 1 7

42. IrelanJT

HagemannAT

SelkerEU

1994 High frequency repeat-induced point mutation (RIP) is not associated with efficient recombination in Neurospora. Genetics 138 1093 1103

43. IdnurmA

HowlettBJ

2003 Analysis of loss of pathogenicity mutants reveals that repeat-induced point mutations can occur in the Dothideomycete Leptosphaeria maculans. Fungal Genet Biol 39 31 37

44. BrunnerPC

StefanatoFL

McDonaldBA

2008 Evolution of the CYP51 gene in Mycosphaerella graminicola: evidence for intragenic recombination and selective replacement. Mol Plant Pathol 9 305 316

45. van den BurgHA

WesterinkN

FrancoijsKJ

RothR

WoestenenkE

2003 Natural disulfide bond-disrupted mutants of AVR4 of the tomato pathogen Cladosporium fulvum are sensitive to proteolysis, circumvent Cf-4-mediated resistance, but retain their chitin binding ability. J Biol Chem 278 27340 27346

46. ChengJ

RandallAZ

SweredoskiMJ

BaldiP

2005 SCRATCH: a protein structure and structural feature prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res 33 W72 76

47. SchurchS

LindeCC

KnoggeW

JacksonLF

McDonaldBA

2004 Molecular population genetic analysis differentiates two virulence mechanisms of the fungal avirulence gene NIP1. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 17 1114 1125

48. StukenbrockEH

McDonaldBA

2007 Geographical variation and positive diversifying selection in the host-specific toxin SnToxA. Mol Plant Pathol 8 321 332

49. RozenS

SkaletskyH

2000 Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol 132 365 386

50. GardinerDM

CozijnsenAJ

WilsonLM

PedrasMS

HowlettBJ

2004 The sirodesmin biosynthetic gene cluster of the plant pathogenic fungus Leptosphaeria maculans. Mol Microbiol 53 1307 1318

51. MullerPY

JanovjakH

MiserezAR

DobbieZ

2002 Processing of gene expression data generated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Biotechniques 32 1372 1374, 1376, 1378–1379

52. MassinghamT

GoldmanN

2005 Detecting amino acid sites under positive selection and purifying selection. Genetics 169 1753 1762

53. YangZ

2007 PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol 24 1586 1591

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiológia Infekčné lekárstvo Laboratórium

Článek Tick Histamine Release Factor Is Critical for Engorgement and Transmission of the Lyme Disease AgentČlánek TGF-b2 Induction Regulates Invasiveness of -Transformed Leukocytes and Disease SusceptibilityČlánek The Origin of Intraspecific Variation of Virulence in an Eukaryotic Immune Suppressive ParasiteČlánek Glycosylation Focuses Sequence Variation in the Influenza A Virus H1 Hemagglutinin Globular Domain

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2010 Číslo 11- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Očkování proti virové hemoragické horečce Ebola experimentální vakcínou rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP

- Koronavirus hýbe světem: Víte jak se chránit a jak postupovat v případě podezření?

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Patients with Discordant Responses to Antiretroviral Therapy Have Impaired Killing of HIV-Infected T Cells

- A Molecular Mechanism for Eflornithine Resistance in African Trypanosomes

- Tyrosine Sulfation of the Amino Terminus of PSGL-1 Is Critical for Enterovirus 71 Infection

- Autoimmunity as a Predisposition for Infectious Diseases

- The Subtilisin-Like Protease AprV2 Is Required for Virulence and Uses a Novel Disulphide-Tethered Exosite to Bind Substrates

- Structural Analysis of HIV-1 Maturation Using Cryo-Electron Tomography

- Tick Histamine Release Factor Is Critical for Engorgement and Transmission of the Lyme Disease Agent

- Interferon-Inducible CXC Chemokines Directly Contribute to Host Defense against Inhalational Anthrax in a Murine Model of Infection

- TGF-b2 Induction Regulates Invasiveness of -Transformed Leukocytes and Disease Susceptibility

- The Origin of Intraspecific Variation of Virulence in an Eukaryotic Immune Suppressive Parasite

- CO Acts as a Signalling Molecule in Populations of the Fungal Pathogen

- SV2 Mediates Entry of Tetanus Neurotoxin into Central Neurons

- MAP Kinase Phosphatase-2 Plays a Critical Role in Response to Infection by

- Glycosylation Focuses Sequence Variation in the Influenza A Virus H1 Hemagglutinin Globular Domain

- Potentiation of Epithelial Innate Host Responses by Intercellular Communication

- Fcγ Receptor I Alpha Chain (CD64) Expression in Macrophages Is Critical for the Onset of Meningitis by K1

- ANK, a Host Cytoplasmic Receptor for the Cell-to-Cell Movement Protein, Facilitates Intercellular Transport through Plasmodesmata

- Analysis of the Initiating Events in HIV-1 Particle Assembly and Genome Packaging

- Evolution of Linked Avirulence Effectors in Is Affected by Genomic Environment and Exposure to Resistance Genes in Host Plants

- Structural Basis of HIV-1 Neutralization by Affinity Matured Fabs Directed against the Internal Trimeric Coiled-Coil of gp41

- Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Evades NKG2D-Dependent NK Cell Responses through NS5A-Mediated Imbalance of Inflammatory Cytokines

- Host Cell Invasion and Virulence Mediated by Ssa1

- Global Gene Expression in Urine from Women with Urinary Tract Infection

- Should the Human Microbiome Be Considered When Developing Vaccines?

- HapX Positively and Negatively Regulates the Transcriptional Response to Iron Deprivation in

- Enhancing Oral Vaccine Potency by Targeting Intestinal M Cells

- Herpes Simplex Virus Reorganizes the Cellular DNA Repair and Protein Quality Control Machinery

- The Female Lower Genital Tract Is a Privileged Compartment with IL-10 Producing Dendritic Cells and Poor Th1 Immunity following Infection

- Zn Inhibits Coronavirus and Arterivirus RNA Polymerase Activity and Zinc Ionophores Block the Replication of These Viruses in Cell Culture

- Cryo Electron Tomography of Native HIV-1 Budding Sites

- Crystal Structure and Size-Dependent Neutralization Properties of HK20, a Human Monoclonal Antibody Binding to the Highly Conserved Heptad Repeat 1 of gp41

- Modelling the Evolution and Spread of HIV Immune Escape Mutants

- The Arabidopsis Resistance-Like Gene Is Activated by Mutations in and Contributes to Resistance to the Bacterial Effector AvrRps4

- Platelet-Activating Factor Receptor Plays a Role in Lung Injury and Death Caused by Influenza A in Mice

- Genetic and Structural Basis for Selection of a Ubiquitous T Cell Receptor Deployed in Epstein-Barr Virus Infection

- Ubiquitin-Regulated Nuclear-Cytoplasmic Trafficking of the Nipah Virus Matrix Protein Is Important for Viral Budding

- Pneumolysin Activates the NLRP3 Inflammasome and Promotes Proinflammatory Cytokines Independently of TLR4

- Immune Evasion by : Differential Targeting of Dendritic Cell Subpopulations

- Survival in Selective Sand Fly Vector Requires a Specific -Encoded Lipophosphoglycan Galactosylation Pattern

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Zn Inhibits Coronavirus and Arterivirus RNA Polymerase Activity and Zinc Ionophores Block the Replication of These Viruses in Cell Culture

- The Female Lower Genital Tract Is a Privileged Compartment with IL-10 Producing Dendritic Cells and Poor Th1 Immunity following Infection

- Crystal Structure and Size-Dependent Neutralization Properties of HK20, a Human Monoclonal Antibody Binding to the Highly Conserved Heptad Repeat 1 of gp41

- The Arabidopsis Resistance-Like Gene Is Activated by Mutations in and Contributes to Resistance to the Bacterial Effector AvrRps4

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy