-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

A Novel Role for the NLRC4 Inflammasome in Mucosal Defenses against the Fungal Pathogen

Candida sp.

are opportunistic fungal pathogens that colonize the skin and oral cavity and, when overgrown under permissive conditions, cause inflammation and disease. Previously, we identified a central role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in regulating IL-1β production and resistance to dissemination from oral infection with Candida albicans. Here we show that mucosal expression of NLRP3 and NLRC4 is induced by Candida infection, and up-regulation of these molecules is impaired in NLRP3 and NLRC4 deficient mice. Additionally, we reveal a role for the NLRC4 inflammasome in anti-fungal defenses. NLRC4 is important for control of mucosal Candida infection and impacts inflammatory cell recruitment to infected tissues, as well as protects against systemic dissemination of infection. Deficiency in either NLRC4 or NLRP3 results in severely attenuated pro-inflammatory and antimicrobial peptide responses in the oral cavity. Using bone marrow chimeric mouse models, we show that, in contrast to NLRP3 which limits the severity of infection when present in either the hematopoietic or stromal compartments, NLRC4 plays an important role in limiting mucosal candidiasis when functioning at the level of the mucosal stroma. Collectively, these studies reveal the tissue specific roles of the NLRP3 and NLRC4 inflammasome in innate immune responses against mucosal Candida infection.

Published in the journal: A Novel Role for the NLRC4 Inflammasome in Mucosal Defenses against the Fungal Pathogen. PLoS Pathog 7(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002379

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002379Summary

Candida sp.

are opportunistic fungal pathogens that colonize the skin and oral cavity and, when overgrown under permissive conditions, cause inflammation and disease. Previously, we identified a central role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in regulating IL-1β production and resistance to dissemination from oral infection with Candida albicans. Here we show that mucosal expression of NLRP3 and NLRC4 is induced by Candida infection, and up-regulation of these molecules is impaired in NLRP3 and NLRC4 deficient mice. Additionally, we reveal a role for the NLRC4 inflammasome in anti-fungal defenses. NLRC4 is important for control of mucosal Candida infection and impacts inflammatory cell recruitment to infected tissues, as well as protects against systemic dissemination of infection. Deficiency in either NLRC4 or NLRP3 results in severely attenuated pro-inflammatory and antimicrobial peptide responses in the oral cavity. Using bone marrow chimeric mouse models, we show that, in contrast to NLRP3 which limits the severity of infection when present in either the hematopoietic or stromal compartments, NLRC4 plays an important role in limiting mucosal candidiasis when functioning at the level of the mucosal stroma. Collectively, these studies reveal the tissue specific roles of the NLRP3 and NLRC4 inflammasome in innate immune responses against mucosal Candida infection.Introduction

Candida sp. are dimorphic fungi that commonly colonize the oral cavity of adult humans, with overgrowth prevented by competing commensal bacteria as well as local host immune responses. Perturbations of the normal oral flora through antibiotic treatment, for example, or immunocompromised states can lead to mucosal Candida overgrowth resulting in the development of oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC, also known as thrush). Candida albicans has now been identified as the leading cause of fatal fungal infections, with mortality rates as high as 50%, and ranks 4th among all pathogens isolated from bloodstream and nosocomial infections [1]–[3]. Host recognition of Candida requires engagement of surface receptors on innate immune cells, including TLR2 and Dectin-1 [4]–[7]. A major consequence of receptor activation is the induction of pro-inflammatory gene expression including interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), a zymogen which requires proteolytic processing by caspase-1 to become biologically active [8]–[11]. Activation of caspase-1 requires signaling through recently described protein complexes termed inflammasomes, consisting of either NOD-like receptor (NLR) molecules or the PYHIN protein, Absent in melanoma-2 (AIM2) [12]–[16]. NLRs are characterized by the presence of a Leucine Rich Repeat domain, a central NACHT domain involved in oligomerization and protein-protein interactions, and a CARD or PYRIN domain [17]. Conformational changes in NLR proteins, resulting from the introduction of activating stimuli, cause oligomerization of NLR proteins together with ASC adapters, permitting autocatalytic cleavage of pro-caspase-1 to an active state capable of cleaving pro-IL-1β. Although intracellular danger signals and crystalline compounds such as uric acid crystals, cholesterol crystals, amyloid and asbestos have been shown to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome [18]–[22], the precise mechanism(s) underlying inflammasome activation are not defined. Currently, several theories have been proposed for the molecular mechanisms underlying activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome including mitochondrial ROS production [23], phagosomal or endosomal rupture and cell membrane disturbances [24]–[27]. The NLRP3 inflammasome has been linked to IL-1β responses to pathogen-derived molecules including bacterial muramyl dipeptide [28] and toxins [20], [28], as well as in response to a range of bacterial, viral and fungal pathogens, including Candida albicans [6], [29]. Another NLR molecule, NLRC4, also forms an inflammasome capable of activating caspase-1 and IL-1β cleavage. During some bacterial infections, such as with Shigella, Salmonella, Pseudomonas or Legionella, NLRC4 detects inadvertently translocated flagellin or PrgJ rod protein, a component of the type III secretion system [30]–[35]. Although limited in vitro studies using NLRC4 deficient macrophages or dendritic cells challenged with Candida albicans revealed no defects in caspase-1-dependent IL-1β responses [29], [36], [37], the role of NLRC4 in live fungal infection models has not been thoroughly defined.

In this study, we sought to examine the role of other inflammasome in anti-fungal defenses in vivo. We show that infection with Candida albicans leads to up-regulation of NLRP3 and NLRC4 expression in the oral mucosa and this induction is impaired in both NLRP3 and NLRC4 deficient mice. Additionally, we reveal a role for the NLRC4 inflammasome in regulating resistance to mucosal infection with Candida as well as preventing systemic dissemination. We show that inflammasome driven IL-1β responses via both the NLRC4 and NLRP3 inflammasome are essential for epithelial antimicrobial peptide production, and other inflammatory responses including IL-18 and IL-17 in response to Candida infection. Inflammatory cell recruitment to Candida infected oral mucosa is significantly impaired in NLRC4 deficient mice compared to wild-type mice. Using bone marrow chimera mice, we reveal that the activity of NLRC4 is mediated at the level of the mucosal stroma, in contrast to that observed with NLRP3 which is active in both hematopoietic and stromal compartments. Collectively our studies show that, in addition to the NLRP3 inflammasome, there is a tissue specific role for the NLRC4 inflammasome in host sensing and immune defense to non-bacterial pathogens such as Candida albicans.

Results

Regulation of inflammasome expression in oral mucosal tissues following infection with Candida albicans

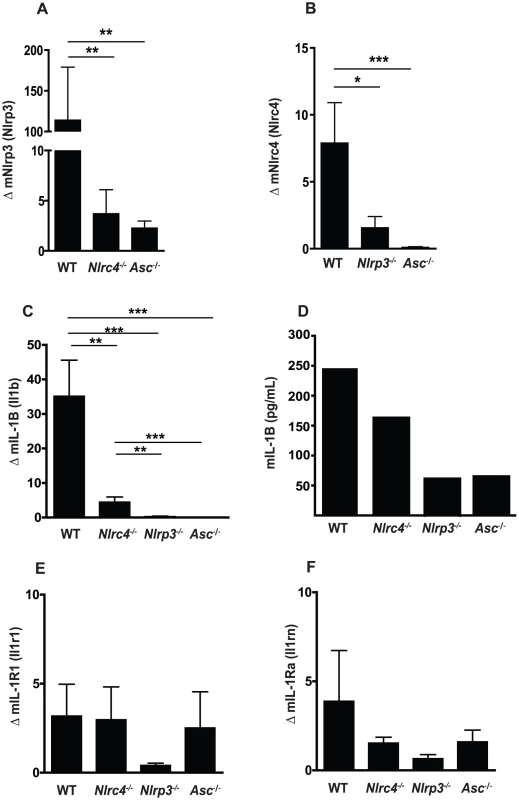

During Candida infection, the oral mucosa acts as a physical barrier to infection as well as the initial tissue to respond to fungal growth and invasion. To assess the impact of Candida treatment on the oral mucosa, we monitored gene expression levels in oral mucosa by quantitative real-time PCR. We first examined the level of NLR expression in buccal tissues of Candida infected mice and observed a strong induction of NLRP3 in wild-type mice following oral challenge with Candida albicans. Induction of NLRP3 was significantly reduced in both Nlrc4−/− and Asc−/− mice (Figure 1A). Similarly, NLRC4 was induced in WT mice and negligible in Nlrp3−/− and Asc−/− mice (Figure 1B). As expected, ASC was not induced in any of the strains after Candida infection. These data indicate that genetic knockdown of a single NLR may have profound effects on the expression profile of other NLR proteins and is, to our knowledge, the first evidence of cross-regulation of NLRP3 and NLRC4.

Fig. 1. Regulation of Nlrp3 and Nlrc4 expression in mucosal candidiasis.

Induction of inflammatory genes in buccal mucosal tissues from WT, Nlrc4 −/−, Nlrp3 −/−, and Asc −/− mice after 72 h of infection with Candida albicans. (A) NLRP3, (B) NLRC4, (C) mIL-1β, (E) mIL-1R1, and (F) mIL-1Ra. All genes normalized to GAPDH. (D) Circulating IL-1β levels were determined by ELISA on serum samples pooled from N≥3 animals. (*** P≤0.001; ** P≤0.01; * P≤0.05) Candida induced IL-1β in the oral mucosa is dependent on both NLRP3 and NLRC4

We next assessed the impact of the NLRP3 and NLRC4 inflammasomes on expression levels of members of the IL-1 family. There was a significant difference in the induction of IL-1β between the WT and Nlrc4−/−, Nlrp3−/−, and Asc−/− mice (Figure 1C). This defect in IL-1β production was confirmed in the serum of infected mice at 3 days of infection (Figure 1D). Levels of IL-1R1 expression were similar between WT and Nlrc4−/− or Asc−/− mice with reduced induction observed in Nlrp3−/− mice, although this was not significant (Figure 1E). Induction of IL-1R antagonist (IL-1Rn) was not significantly different between any of the inflammasome knockout mice and WT mice (Figure 1F). Overall, the induction of IL-1R1 and IL-1Rn was minimal compared to IL-1β in all the infected mice.

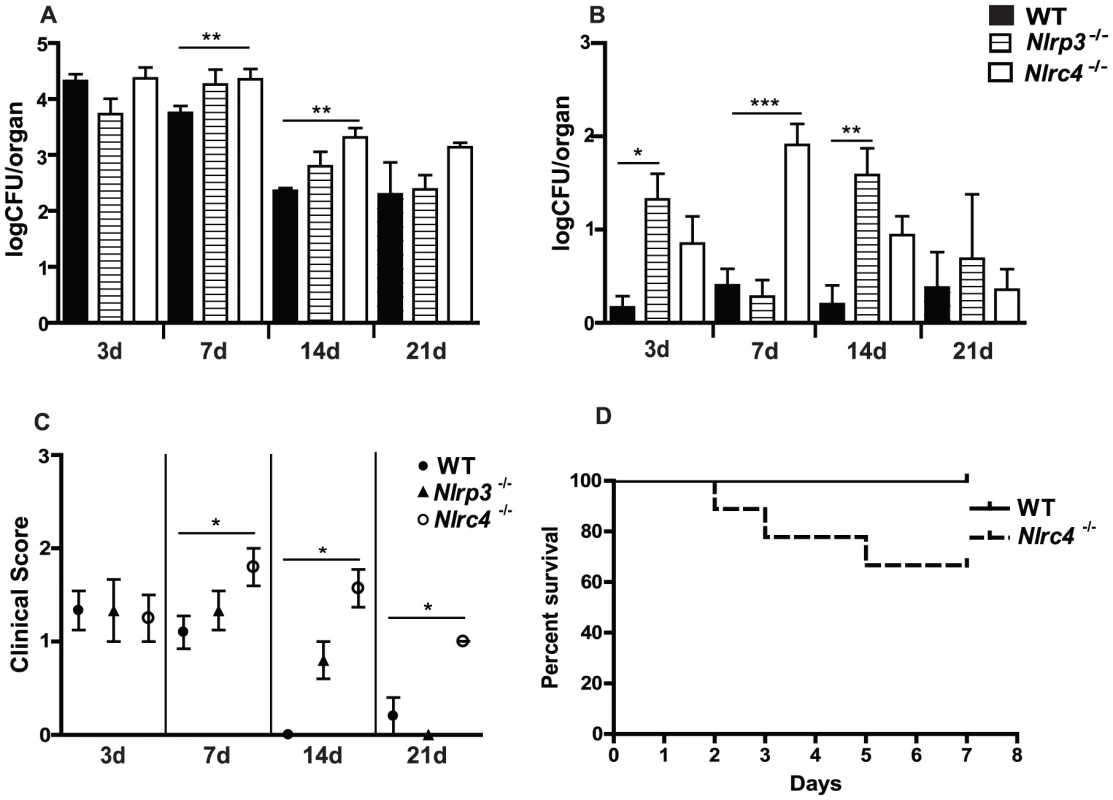

NLRC4 protects against mucosal fungal infection and early dissemination of infection in a murine model of oropharyngeal candidiasis

Our previous studies demonstrated that NLRP3 signaling is critical for the prevention of fungal growth as well as dissemination in a murine model of oropharyngeal candidiasis [6]. A role for the NLRC4 inflammasome in response to oral fungal challenge has yet to be characterized. In order to ascertain the impact of loss of NLRC4 function on disease progression, we infected wild-type (WT) and Nlrc4−/− mice with Candida albicans as previously described [6]. Oral fungal burdens were elevated in Nlrc4−/− mice compared to WT mice by day 7, and persistently higher fungal burdens were observed to day 21 (Figure 2A). In our model of persistent, low virulence oral candidiasis, WT mice rarely show blood borne dissemination of infection, as measured by quantitative fungal burdens in the kidneys (Figure 2B). In contrast, Nlrc4−/− mice show a significantly increased susceptibility to dissemination of infection, peaking at day 7 but returning to WT levels by day 21. In agreement with these findings, Nlrc4−/− mice also had elevated gross clinical scores, a qualitative measure of oral infection severity, at all time points (Figure 2C). Survival in the Nlrc4−/− mice was reduced when compared to WT mice when infected with a virulent strain of Candida albicans (Figure 2D). Elevated quantitative fungal colonization was observed in tissues of the gastrointestinal tract including esophagus, stomach, and small intestine in Nlrc4−/− mice compared to WT (Figure S1).

Fig. 2. NLRC4 inflammasome protects against mucosal overgrowth and prevents systemic dissemination of infection with Candida albicans.

(A) Quantitative fungal burden of tongues, and (B) kidneys of Nlrp3−/−, Nlrc4 −/−, and WT mice after oral infection with C. albicans; (C) Mean clinical severity score of Nlrp3−/−, Nlrc4 −/−, and WT mice after 3, 7, 14 or 21d of infection. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of WT and Nlrc4−/− mice infected with virulent C. albicans. (*** P≤0.001; ** P≤0.01; * P≤0.05) These data contrast with studies in Nlrp3−/− mice, in which it was determined that oral fungal colonization was similar at day 3, becoming slightly elevated at day 7 and 14, and returning to WT levels by day 21 (Figure 2A). These mice exhibited elevated levels of systemic dissemination throughout the 21 day timecourse (Figure 2B). By day 21, the gross clinical score of both Nlrp3−/− and WT mice were between 0 and 1, indicating minimal signs of infection, which contrasts the sustained elevated clinical score seen in Nlrc4−/− mice (Figure 2C). Taken together, our studies imply that NLRC4 and NLRP3 are differentially functioning in the innate response to Candida infection, with NLRC4 playing a more prominent role in the clearance of oral infection.

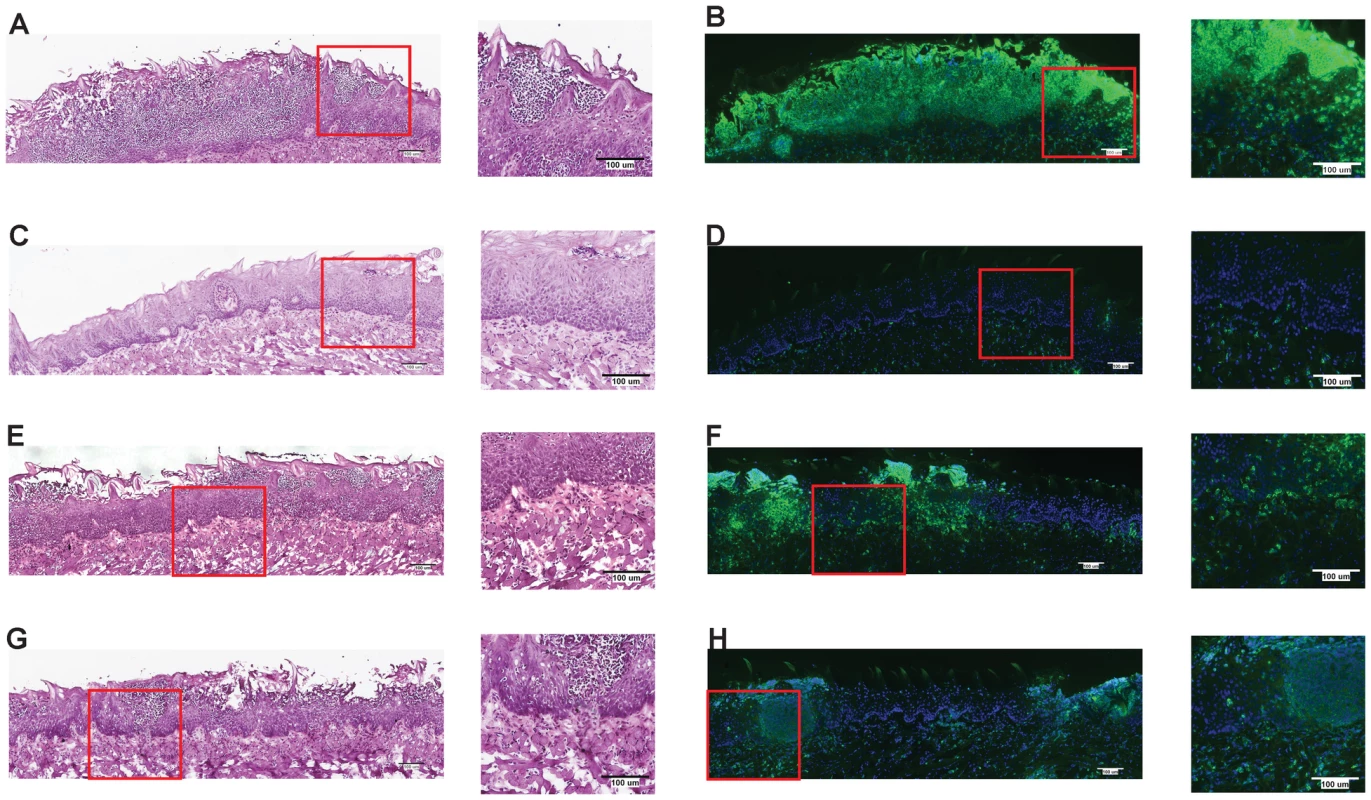

NLRC4 is required for neutrophil recruitment following Candida challenge

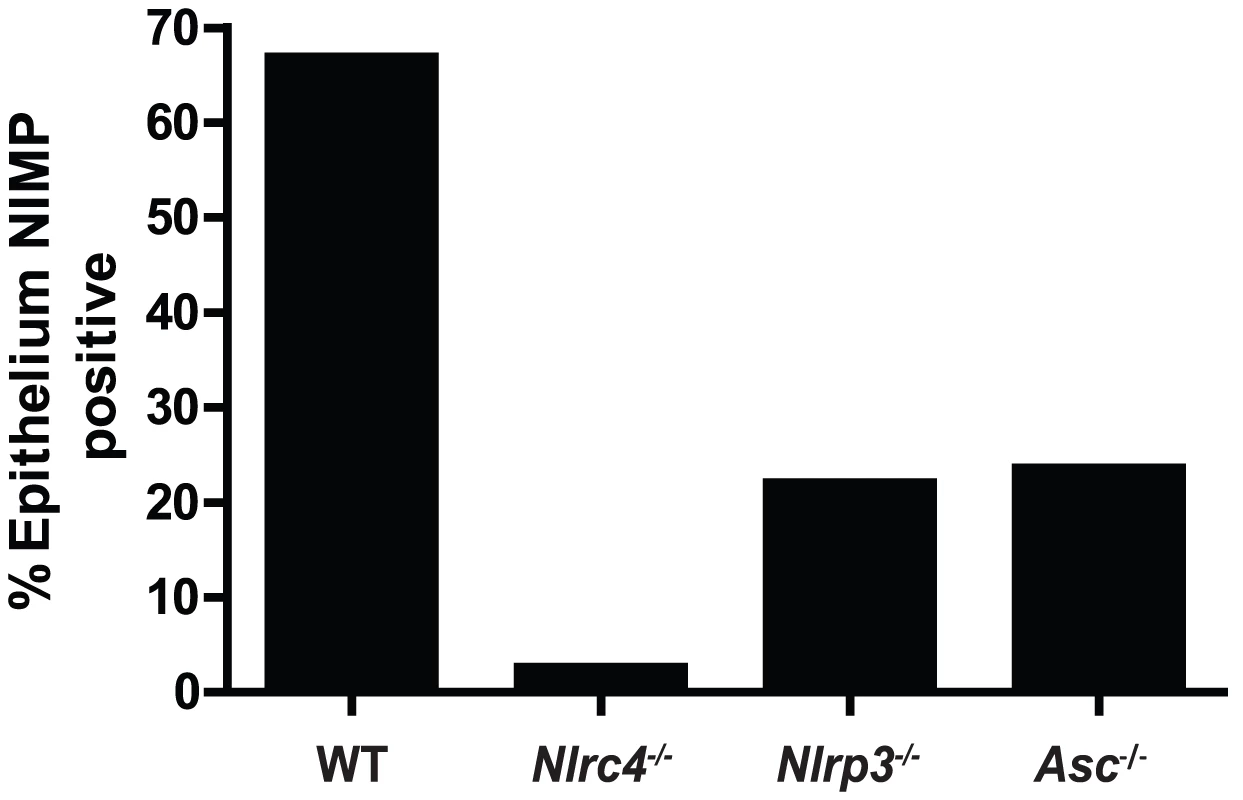

One of the earliest inflammatory cells that migrate to the site of microbial infection are neutrophils, and this chemotaxis is necessary for proper inflammatory responses and anti-microbial defenses. Given the known capacity for IL-1β to mediate leukocyte infiltration into infected tissues, we used histology to examine the impact of inflammasome deficiency on cellular infiltration to the mucosa of the tongue. By day 2, a robust cellular infiltration was observed in the dorsal epithelium of a WT tongue, particularly in areas showing the presence of fungal hyphae and epithelial erosion (Figure 3A). These cells morphologically appear to have multi-lobulated nuclei, consistent with neutrophils. In contrast, minimal cellular infiltration was observed in a tongue from Nlrc4−/− mouse, despite the presence of erosive lesions and fungal hyphae (Figure 3C). Nlrp3−/− and Asc−/− tongues exhibited cellular infiltration, although not to the extent of WT; and these areas of concentrated cellular infiltrates also correlated with the presence of fungal hyphae and tissue erosion (Figure 3E, G). Neutrophils have been implicated in the control of a range of microbial infections, including Candida [38]–[40]. Given the presence of significant cellular infiltration at 2d post infection, we sought to specifically characterize the extent of neutrophil infiltration in these tissues. Using a monoclonal antibody shown to specifically stain neutrophils, we observed significant neutrophil staining in the outer epithelium of the WT tongue. This immunofluorescent staining localized to the regions of increased cellularity observed in the epithelium with PAS/H staining (Figure 3B). Neutrophils were also observed throughout the sub-mucosal tissue. In agreement with our finding with PAS/H staining, neutrophil influx into the Nlrc4−/− was drastically reduced (Figure 3D). As expected, a significant influx of neutrophils was observed in both Nlrp3−/− and Asc−/− tongues (Figure 3F, H). Intriguingly, it was observed that not only was there a reduction in neutrophil infiltration in the Nlrc4−/− tongue but the neutrophils present failed to infiltrate the epithelium where the presence of hyphae was detected. This is evidenced by a ∼25 fold reduction in the percent of dorsal epithelium that stains positive for neutrophils in Nlrc4−/− mice when compared to WT (Figure 4). Nlrp3−/− and Asc−/− mice showed a ∼3 fold decrease in positive staining (Figure 4). These findings indicate that the activation of Nlrc4−/− is required for neutrophil recruitment into infected tissues and proper trafficking to the site of active fungal infection.

Fig. 3. NLRC4 inflammasome mediates neutrophil influx response to mucosal Candida infection.

PASH stains of GDH2346 infected tongues from (A) WT, (C) Nlrc4−/−, (E) Nlrp3−/−, and (G) Asc−/−. Tongue sections were stained with the neutrophil-specific NIMP antibody and DAPI for (B) WT, (D) Nlrc4−/−, (F) Nlrp3−/−, and (H) Asc−/−. Magnified 40x images of sections are included. Fig. 4. Quantified neutrophil responses in Candida infected epithelium.

Neutrophil influx into dorsal epithelium of WT, Nlrc4−/−, Nlrp3−/−, and Asc−/− mice was digitally quantified using MetaMorph software. Shown are percent ratios of fluorescent pixels (representing neutrophil staining) over total pixels within a region containing the dorsal epithelium and submucosa of infected tongues. Mucosal IL-17 responses to Candida are dependent on both NLRP3 and NLRC4

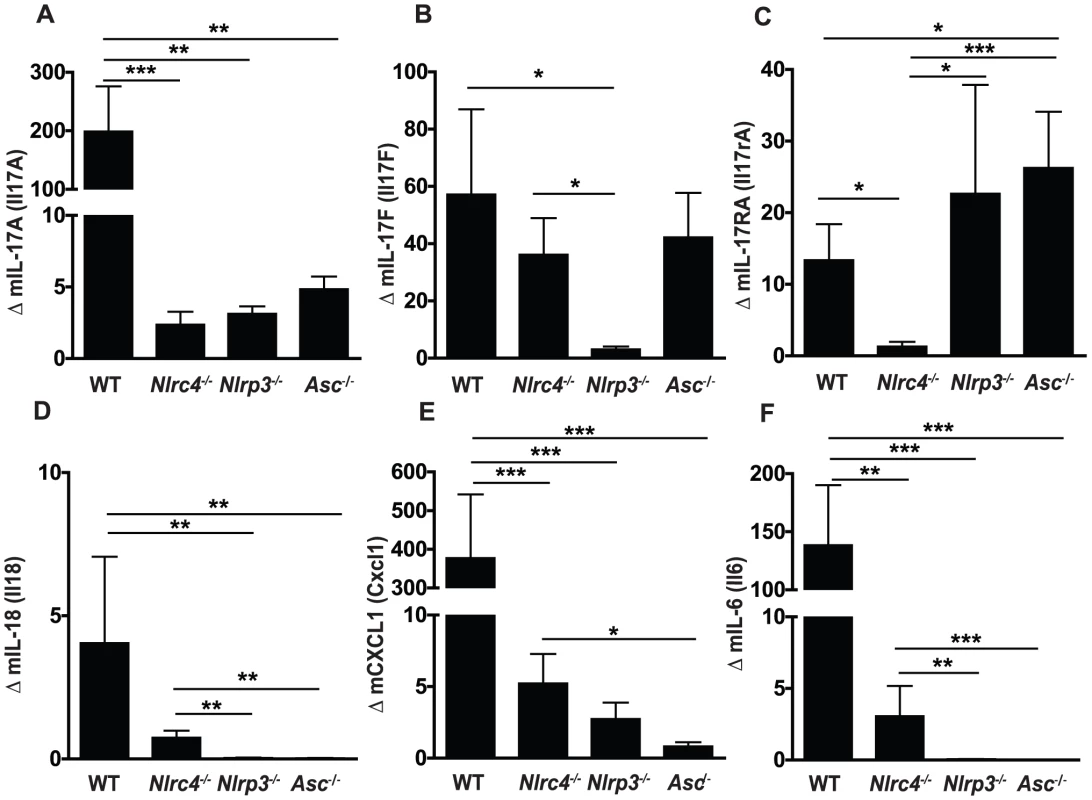

Recent reports have implicated the IL-17 family as a critical mediator of protective host responses to a range of extracellular pathogens, including Candida [41]–[45]. To assess the impact of inflammasome activation on IL-17 in our model of oral candidiasis, we measured expression levels of IL-17 family members in oral mucosal tissues after infection. A robust increase in IL-17A and IL-17F gene expression was detected in the oral mucosal tissue of WT animals, which was significantly reduced in Nlrc4−/−, Nlrp3−/−, and Asc−/− mice (Figure 5A, B). In contrast, the induction of IL-17F was dependent on NLRP3, but not NLRC4 or ASC (Figure 5B). A robust induction of interleukin 17A receptor (IL-17RA) expression was detected in WT, Nlrp3−/−, and Asc−/− mice while this response was abrogated in Nlrc4−/− mice (Figure 5C). As many downstream inflammatory responses are dependent on IL-17, the failure to upregulate the IL-17A receptor may have implications for local anti-Candida inflammation and chemotaxis of inflammatory cells.

Fig. 5. Inflammasome dependence of inflammatory cytokine responses in the oral mucosa following Candida infection.

Induction of inflammatory genes in buccal mucosal tissues from WT, Nlrc4 −/−, Nlrp3 −/−, and Asc −/− mice after 72 h of infection with Candida albicans. (A) mIL-17A, (B) mIL-17F, (C) mIL-17RA, (D) mIL-18, (E) mKC/CXCL1 and (F) mIL-6. All genes normalized to GAPDH. (*** P≤0.001; ** P≤0.01; * P≤0.05). Inflammasome dependence of other inflammatory cytokine responses in the oral mucosa following Candida infection

We next examined expression of other inflammatory cytokines in the oral mucosa of mice infected with Candida albicans. We observed significantly lower induction of IL-18, another cytokine requiring inflammasome mediated cleavage, in Nlrp3−/− and Asc−/− mice, while Nlrc4−/− mice showed a slight reduction compared to WT which was not statistically different (Figure 5D). As shown in Figure 5E, murine CXCL1, a homolog of human IL-8, was dramatically induced in WT mice following Candida infection and levels were significantly reduced in all strains of inflammasome deficient mice. Induction of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 was also significantly reduced in Nlrc4−/−, Nlrp3−/−, and Asc−/− mice compared to WT (Figure 5F).

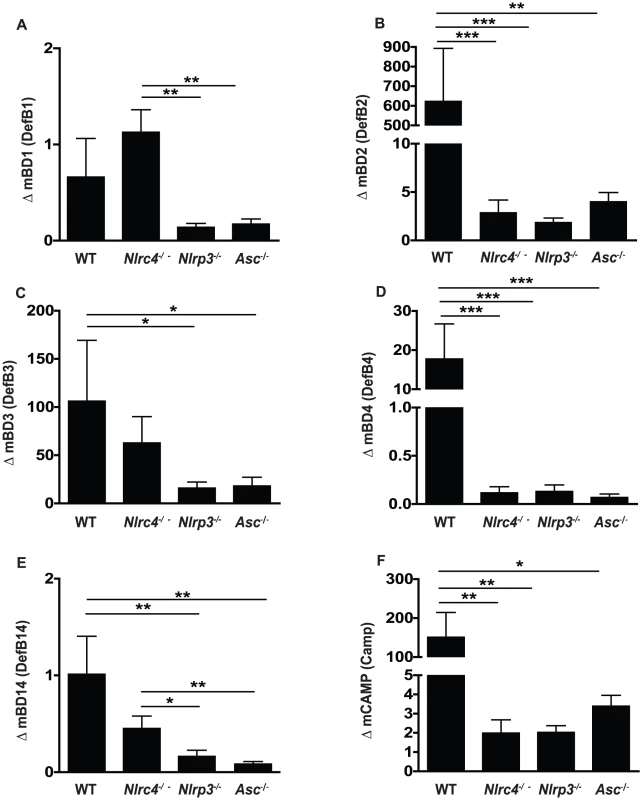

Mucosal antimicrobial peptide responses to Candida albicans infection

In addition to inflammatory cytokines responses following pathogenic encounter, immune cells in the oral mucosa, including epithelial cells, release small antimicrobial peptides designed to disrupt microbial function as well as act as strong chemoattractant signals for the migration of inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and macrophages [46]–[48]. To better define the inflammasome dependence of antimicrobial peptide responses in our murine model of OPC, we quantified several murine beta-defensins as well as cathelicidin responses in the oral mucosa following fungal infection. In contrast to murine beta-defensin 1 (mBD1), which was not induced following infection in any of the mice (Figure 6A), mBD2, -3, -and 4 all showed elevated expression in oral tissues following Candida infection in WT mice (Figure 6B, C, D). Reduced or negligible up-regulation in mBD2 and mBD4 gene expression was observed in all of the inflammasome deficient mice (Figure 6B, D). In contrast, mBD3 induction was similar between WT and Nlrc4−/− mice but significantly reduced in Nlrp3−/− and Asc−/− mice (Figure 6C). No appreciable induction of mBD14, a murine homolog of human beta-defensin 3, was observed in any of the mice (Figure 6E). Another antimicrobial peptide, cathelicidin or CAMP, has also been implicated as an activator of the P2X7 receptor and a potential inducer of IL-1β release from cells [49]. Expression levels of CAMP were dramatically elevated in WT buccal tissue following Candida infection, and this induction was dependent on NLRC4, NLRP3 and ASC (Figure 6F).

Fig. 6. Antimicrobial peptide up-regulation in response to oral infection with Candida albicans is impaired in NLRP3, ASC and NLRC4 - deficient mice.

Expression of the antimicrobial peptides (A) murine β-defensin 1, (B) murine β-defensin 2, (C) murine β-defensin 3, (D) murine β-defensin 4, (E) murine β-defensin 14, and (F) CAMP in buccal mucosal tissues from WT, Nlrc4 −/−, Nlrp3 −/−, and Asc −/− mice after 72 h of infection with Candida albicans. (*** P≤0.001; ** P≤0.01; * P≤0.05). NLRC4 functioning in the mucosa, compared to NLRP3 in inflammatory cells, is critical for host defense against mucosal colonization

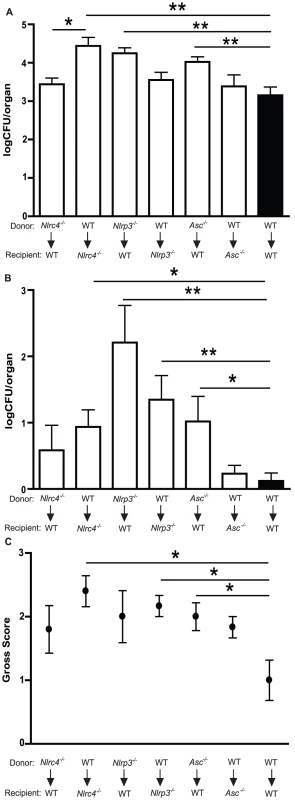

NLRC4 does not appear to be involved in inflammasome activation in innate immune cells exposed to Candida in vitro [29], [36], [37]. Yet in our in vivo model on mucosal candidiasis, NLRC4 is required for protection from mucosal colonization, prevention of early dissemination of infection, and neutrophil infiltration. Therefore, we hypothesized that the impact of NLRC4 activation during fungal infection was manifested in mucosal and/or stromal tissues versus hematopoietic cells. The innate immune system is comprised of cells of embryonic origin, including epithelial cells, as well as infiltrating leukocytes derived from the bone marrow. To assess the contribution of different inflammasome molecules in these compartments, we generated bone marrow chimera mice and infected them orally with C. albicans. Lethally irradiated recipient mice were reconstituted with bone marrow progenitor cells and allowed to fully reconstitute prior to infection. WT mice that were reconstituted with WT bone marrow exhibited no increase in oral infection or systemic dissemination of infection at 7 days when compared to non-chimeric WT mice, indicating that the chimera procedure does not predispose the mice to higher levels of fungal infection (Figure S2). WT mice reconstituted with Nlrc4−/− bone - marrow showed no significant difference in oral fungal colonization compared to WT/WT chimera mice (Figure 7A). In contrast, Nlrc4−/− mice reconstituted with WT bone marrow showed enhanced oral colonization with C. albicans (Figure 7A), to a degree that is similar to native Nlrc4−/− mice (Figure 2A). The Nlrc4−/− mice reconstituted with WT bone marrow also exhibited increased disease severity when compared to WT/WT chimera mice (Figure 7C). These results demonstrate that intact NLRC4 function in the stromal or epithelial compartment is associated with protection from mucosal infection with Candida albicans.

Fig. 7. NLRC4 activity in somatic tissues, in contrast to NLRP3 in both hematopoietic and stromal compartments, controls oral infection with Candida albicans.

Quantitative fungal burden of (A) tongues and (B) kidneys of WT, Nlrc4 −/−, Nlrp3 −/−, Asc −/− bone marrow chimera mice after oral infection with C. albicans; (C) Mean clinical severity score of WT, Nlrc4 −/−, Nlrp3 −/−, Asc −/− bone marrow chimera mice after 7d of infection. (*** P≤0.001; ** P≤0.01; * P≤0.05). To evaluate the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the stromal versus hematopoietic compartments, bone marrow chimeras were generated using Nlrp3−/− as well as Asc−/− mice. Nlrp3−/− mice receiving WT bone marrow showed difference in oral fungal burdens relative to WT/WT chimera controls (Figure 7A). However, WT mice reconstituted with Nlrp3−/− bone marrow exhibited significantly elevated oral infection when compared to WT/WT chimera mice (Figure 7A), although both sets of NLRP3 chimera mice showed elevated clinical scores compared to WT/WT chimera mice (Figure 7C). A similar pattern was seen with ASC chimeric mice (Figure 7A), where higher oral fungal colonization was observed in the WT mice receiving ASC deficient bone marrow compared to Asc−/− mice receiving WT cells or WT/WT chimera mice. These observations indicate that the function of the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome complex in infiltrating inflammatory cells is critical for control of oral mucosal infection.

NLRP3 inflammasome expression in both hematopoietic and stromal cell lineages is required for protection against dissemination of mucosal infection with C. albicans

We next assessed the role of NLRC4 and NLRP3 in protection from systemic dissemination of infection. As a marker of dissemination, we quantified the fungal burdens of the kidneys in bone marrow chimera mice infected with C. albicans for 7 days. As shown in Figure 7B, neither Nlrc4−/− donor nor recipient chimera mice showed dissemination to the degree seen in native Nlrc4−/− mice (Figure 2B), although a trend towards increased dissemination was observed compared to WT/WT chimera mice. In contrast, both Nlrp3−/− donor and recipient chimera mice showed higher systemic dissemination when compared to WT/WT chimera mice (Figure 7B). WT mice receiving Asc−/− bone marrow showed enhanced dissemination of infection, whereas Asc−/− mice receiving WT bone marrow showed similar kidney fungal burdens to WT/WT chimera mice (Figure 7B). These results demonstrate that the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome plays a dominant role in protection against disseminated fungal infection compared to the NLRC4 inflammasome which plays a role in protection of the host from mucosal infection.

Discussion

Disseminated fungal infections present a significant health risk to both immune-competent and -compromised individuals, making studies into early host immune responses involved in the prevention of dissemination critical for the development of new therapeutic approaches. The release of inflammatory mediators from resident cells at the site of infection is critical for antimicrobial responses including the recruitment of inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and macrophages. IL-1β has been implicated in protective host immune responses to a range of infectious pathogens including viruses, bacteria, and fungi [11]. We and others have previously shown that the NLRP3 inflammasome is important for control of Candida infection in both mucosal and disseminated models [6], [29], [36], [37]. Here we present the first experimental evidence implicating the NLRC4 inflammasome in the induction of protective host responses to challenge by a fungal pathogen. Our studies reveal that the NLRC4 inflammasome is important for the control of Candida albicans infection in vivo, particularly in the oral cavity, with increased oral fungal colonization and disease severity observed in Nlrc4−/− mice. Lack of NLRC4 also increased susceptibility to disseminated fungal infection, particularly early in infection. Our model of OPC using a clinical isolate recapitulates human oral infections in which mortality is rarely observed. We carried out OPC infection studies using a highly virulent strain of C. albicans (ATCC 90234) and observed similar increases in oral colonization and dissemination at 7d to that observed using the oral isolate GDH2346 (Figure S1). However, the virulent strain resulted in significant mortality in Nlrc4−/− mice when compared to WT (Figure 2E). When we examined cellular infiltrations in infected tongues, we observed a substantial impact in both cellular infiltration, and specifically neutrophil-influx in the absence of NLRC4, compared to a robust neutrophil infiltration into the infected epithelium of WT mice. Interestingly, the neutrophils that were present in the Nlcr4−/− tongue remained in the sub-mucosa. This defect in neutrophil infiltration into the epithelium of the tongue may explain the extended defect in oral clearance observed in Nlrc4−/− mice throughout the course of our OPC infection studies. The importance of neutrophils in anti-fungal defenses is well known. Recent studies have shown that the innate inflammatory mileu is critical for effective neutrophil activity against fungal pathogens including IL-6, GM-CSF, and IL-17 responses [38], [41], [42], [50], [51].

In order to better define the molecular basis for protection from mucosal infection, we evaluated a panel of innate inflammatory responses in the oral mucosa from Candida infected mice. Previous studies have demonstrated that NLRP3 expression is inducible following infection and implicate this as the rate limiting step in inflammasome activation [52], [53] but little is known about the regulation of NLRC4 expression. IL-1β has been shown to increase the expression level of other pro-inflammatory cytokines following IL-1 receptor engagement [54]-[56], and IL-1 receptor activation may result in the increased expression of inflammasome proteins in the responding cells, priming them for quick activation. We show that Candida infection up-regulates NLRP3 and NLRC4 expression in mucosal tissues compared to mock infected mice. Additionally, we demonstrate that this induction is impaired in Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/− and Nlrp4−/− mice. As expected, ASC expression was found to be constitutive and not induced by Candida infection (data not shown). Our data provides novel insight into transcriptional changes induced by activation of inflammasome complex by an infectious pathogen. The impairment of mucosal NLRP3 induction in NLRC4 deficient mice may enhance the impact of the lack of this receptor on susceptibility to mucosal infection.

As expected, we found that IL-1β was up-regulated in wild-type mice in response to fungal infection. However, these responses were partially abrogated in NLRC4 deficient mice and absent in NLRP3 and ASC deficient mice. Similarly, the IL-1 receptor 1 (IL1R1) and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL1Rn) were poorly induced by Candida infection in WT and inflammasome deficient mice. Consistent with published studies, we did not observe a role for the NLRC4 inflammasome in IL-1β induction or processing in inflammatory cells stimulated in vitro with Candida albicans [29], [36], [37].

IL-18 is another member of the IL-1 family which requires proteolytic enzyme cleavage for activation [57], [58]. Although caspase-1 mediated cleavage of pro-IL-18 into the bioactive form is the accepted paradigm, alternative mechanisms for cleavage have been proposed including PR3, granzyme B and mast cell chymase [59], [60]. In our studies, in vivo IL-18 induction by Candida infection showed a similar pattern in mucosal tissues as IL-1β. Next, we investigated the regulation of the cytokine IL-17, which has been shown to play a role in anti-fungal immunity in humans and in animal models [41], [42], [44], [45]. In response to infection with Candida albicans, IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-17RA were up-regulated in mucosal tissues. Interesting patterns of induction of the IL-17 family by Candida infection were observed; IL-17A was dependent on NLRC4, NLRP3 and ASC whereas IL-17F was only dependent on NLRP3 with comparable induction seen in WT, NLRC4 and ASC deficient mice. The induction of IL-17RA was only dependent on NLRC4. The inflammasome dependence of IL-17 family responses during microbial infection is not well understood, and the regulation of these genes is likely multi-factorial, including dependence on IL-1β as well as other inflammatory mediators. The cytokine IL-6 was induced in wild-type mice in response to Candida infection but was significantly reduced in NLRC4 deficient mice and completely abrogated in NLRP3 and ASC deficient mice. The chemokine KC (CXCL1), a murine homolog of human IL-8, was also found to be highly dependent on IL-1β as NLRC4, NLRP3, and ASC deficient mice exhibited significant decreases in gene expression following fungal challenge. Although IL-6 and KC/IL-8 are not known to be major mediators of anti-fungal immunity, they play an important role in the cytokine network of innate cellular communication. IL-6 has been shown to be directly up-regulated in macrophages by Candida cell wall components [61] but can also be induced by secondary effect of other inflammatory responses. IL-6 signaling has also been shown to be important in the recruitment of neutrophils in response to Candida [38], [62]. IL-6 production is regulated by a complex network of signaling pathways that include NF-κB as well as a newly described pathway mediated by the protein tyrosine phosphatase, Src homology domain 2-containing tyrosine phosphatase-1 (SHP-1) leading to activation of Erk1/2–C/EBPβ [63]. This is particularly relevant to mucosal anti-fungal immunity as SHP-1, also known as PTPN6 and PTP1C, has been shown to negatively regulate the effects of epidermal growth factor [64], an important regulator of epithelial homeostasis, as well as affect tight junction formation in epithelium [65]. We propose, based on our histological analysis, that the defect in the induction of inflammatory mediators observed in mice deficient in the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome is most likely due to defective functioning of inflammatory leukocytes in the absence of these proteins. In contrast, the partial defect in inflammatory responses observed in mucosal tissues from infected NLRC4−/− mice is likely due to impaired infiltration of immune cells into infected tissue.

Another key innate immune response during infection is the release of antimicrobial peptides designed to limit pathogen growth and survival. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) consist of a diverse group of small cationic peptides including the defensins, cationic and amphipathic peptides which have broad antimicrobial and chemotactic properties. Beta-defensins are primarily secreted by epithelial cells and play an important role in the microbial homeostasis of the skin, oral cavity, lung and gut. Human β-defensin (hBD)-1 is primarily expressed in the urinary and respiratory tracts [66], [67] and although constitutively expressed, may be up-regulated by infection or inflammation. A defect in hBD-1 activity in the lung has been associated with cystic fibrosis [68], [69]. Polymorphisms in the defensin-1 gene, defB1, have been associated with low oral colonization with Candida albicans (Jurevic 2003), protection from HIV [70]–[72], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [73] and Crohn's disease [74]. The murine homolog of hBD-1, murine β-defensin (mBD)-1, is also expressed by epithelial surfaces, lung and kidney and has salt sensitive antimicrobial activity [75], although its role in antifungal defense is unclear. Both hBD-2 and hBD-3 have known anti-Candida [46], [76]–[78] as well as anti-HIV activity [79], [80]. The role of mBD-2, the murine homolog of hBD-2, in oral mucosal health is unclear although its expression in the lung is highly inducible by LPS [81]. The murine ortholog of hBD-3, mBD-14, has inducible expression in the respiratory and intestinal tracts as well as in dendritic cells and shows anti-bacterial and chemotactic activity [82]. To better define the role of AMPs in anti-fungal defense, we examined AMP responses in oral mucosa after infection with Candida albicans. We show that mBD-1 appeared to be constitutively expressed in WT mice; however, gene expression was inhibited in NLRP3 and ASC deficient mice. We discovered that mBD-2, -4 and -14 were highly dependent on inflammasome activation as both NLRC4 and NLRP3 as well as ASC deficient mice exhibited dramatically reduced expression levels compared to WT. Interestingly, mBD-3 responses were found to have little dependence on NLRC4 but were dependent on NLRP3 and ASC. Another class of AMPs, the cathelicidins, consisting of human LL-37 and murine CAMP (also known as CRAMP), are known to have anti-Candida as well as chemotactic activity [83]–[87]. We observed that CAMP was highly up-regulated in WT mucosa in infected mice, but not in NLRC4, NLRP3 or ASC deficient mice. A recent report found that IL-17A augmented vitamin D3-mediated CAMP production in keratinocytes during psoriasis [88]. In concurrence with these findings, we observed abrogated CAMP expression in NLRC4 and NLRP3 deficient mice, which also lacked IL-17A gene expression, following Candida challenge. In addition to its direct antimicrobial effects, CAMP has been identified as a modulator of the P2X7R which has a known role in ATP-induced IL-1β release [49], [89], [90]. From our studies, it can be inferred that initial production of IL-1β may induce IL-17A and CAMP production which can in turn positively regulate further production of IL-1β to create an inflammatory environment which limits fungal infection. This mechanism may serve to explain the strong in vivo phenotype observed in our model for NLRC4 and NLRP3 deficient mice, perhaps via a failure to engage this positive feedback loop resulting in an immune state that is prone to persistent infection. In addition to driving IL-1β and IL-18 responses, the NLRC4 inflammasome has been shown to induce a specialized form of programmed cell death, termed pyroptosis or pyronecrosis, characterized by the release of cytoplasmic contents, which include inflammatory mediators such as ATP and arachidonic acid metabolites, to the extracellular matrix. A defect in pyroptosis may partially account for the critical role for NLRC4 activation in our model of candidiasis and provides an opportunity for future research.

Interestingly, our data shows that activation of the NLRC4 inflammasome is important in the stromal compartment, where its role is critical for in vivo anti-fungal host defense, but not in the hematopoietic compartment. Using bone marrow chimera mice we differentiated between inflammasome activity in hematopoietic derived cells such as infiltrating macrophages and neutrophils, and embryonic derived mucosal tissues in our model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. This approach demonstrated that NLRP3 and ASC activity in both hematopoietic and stromal compartments are important for protection against oral infection and dissemination. This is in agreement with our previously published findings that the NLRP3 inflammasome was the primary mediator of IL-1β cleavage in murine macrophages stimulated with Candida in vitro [6]. In contrast, in vivo infection of bone marrow chimera mice showed higher mucosal colonization in NLRC4 deficient recipient mice reconstituted with WT inflammatory cells than WT recipients reconstituted with Nlrc4-/- cells, which had similar levels of oral mucosal infection as WT controls. Overall, these studies utilizing chimera mice in our murine model of mucosal fungal infection implicate a novel, tissue-specific role for the NLRC4 inflammasome.

Many key questions are raised by the findings in this paper. Known microbial activators of the NLRC4 inflammasome include Salmonella typhimurium [91], Shigella flexneri [92], [93], Legionella pneumophila [94] and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [34]. Previous reports implicated the activation of NLRC4 by the release of flagellin through the Type-III secretion apparatus and by components of the basal rod proteins of the Type III secretion system itself [93], [95], [96]. Despite these findings, it still remains unclear the mechanism by which NLRC4 senses these activators. Given the homology between the known bacterial activators of NLRC4, it is possible that these proteins may function as a direct receptor recognizing a conserved sequence or structural feature. Current models of NLRP3 activation indicate it does not act as a traditional receptor but rather as a nexus for different pathways invoked following cellular injury and/or infection, which may also be true for the NLRC4 inflammasome. Future studies will seek to elucidate the mechanism of NLRC4 recognition of its activators and also identify the molecule(s) in Candida that induce NLRC4 activation. We hypothesize that mucosal NLRC4 activation may occur as an early event in fungal infection, perhaps as a result of cellular damage or direct effect of infection, leading to the induction of innate responses such as anti-microbial peptides and cytokines that recruit inflammatory cells including neutrophils and macrophages that infiltrate the sites of infection. Candida induced activation of the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome then provides a critical amplification of the innate response leading to protection of the host from overwhelming mucosal and disseminated candidiasis.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The animals described in this study were housed in the AAALAC accredited facilities of the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. All animal use protocols have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Case Western Reserve University and adhere to national guidelines published in Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th Ed., National Academies Press, 2001.

Fungal preparations

Candida albicans strains GDH2346 (NCYC 1467), a clinical strain originally isolated from a patient with denture stomatitis, or ATCC 90234 were utilized for in vitro and in vivo studies. Master plates were maintained on Sabouraud Dextrose (SD) agar. For OPC infection, yeast were grown for 12–16 h in SD broth, pelleted at 3000 rpm for 5 min and washed 2x with sterile 1X PBS. Yeast cells were manually counted using a hemocytometer and diluted to 5×107 cells/mL for live infection.

Murine model of oral Candida albicans infection

Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Nlrp3−/−, Nlrc4−/− and Asc−/− mice were generated by Millenium Pharmaceuticals. Animals were housed in filter-covered micro-isolator cages in ventilated racks. Infection and organ harvesting was performed as described previously [6]. Briefly, after pre-treatment with antibiotic containing water, the mice were anesthetized and light scratches made on the dorsum of the tongue following by the introduction of 5×106 C. albicans yeast. The scratches are superficial, limited to the outermost stratum corneum, and do not cause trauma or bleeding. After infection of 3 to 21 d, the mice were euthanized, organs harvested and homogenized and fungal burdens assessed by growth on SD agar. For gross clinical score assessment, visual inspection of fungal burdens on the tongues was performed under a dissection microscope. A score of 0 indicates the appearance of a normal tongue, with intact light reflection and no visible Candida, a score of 1 denotes isolated patches of fungus, a score of 2 when confluent patches of fungus are observed throughout the oral cavity, and a score of 3 indicates the presence of wide-spread fungal plaques and erosive mucosal lesions.

RNA extraction

For assessment of inflammatory gene induction, buccal tissue was isolated from infected mice and immediately placed into a RNA stabilization reagent (RNAlater, Qiagen). After homogenization in lysis buffer for 1.5 min using a bead-beater homogenizer (Retsch), total RNA was isolated using PrepEase RNA Spin Kit (USB/Affymetrix) followed by conversion to cDNA using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). Whole blood was collected via retro-orbital bleeding into EDTA pre-coated tubes, followed by centrifugation and removal of serum. Serum was stored at −80°C until used.

Quantitative real-time PCR and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Quantitative real-time PCR was done as described [6]. Specific primer sequences are listed in Table S1. Cytokines were measured in serum by ELISA (R&D). NCBI gene accession numbers are as follows: Nlrc4:NM_001033367.3; Nlrp3: NM_145827.3; Asc: NM_023258.4; Il1b: NM_008361.3; Il1r1: NM_008362.2; Il1rn: NM_031167.5; Il17a: NM_010552.3; Il17f: NM_145856.2; Il17ra: NM_008359.2; Il18: NM_008360.1; Cxcl1: NM_008176.3; Il6: NM_031168.1; Defb1: NM_007843.3; Defb2:NM_010030.1; Defb3: NM_013756.2; Defb4: NM_019728.4; Defb14: NM_183026.2; Camp: NM_009921.2.

Histology

Intact tongues are removed at necropsy, immediately immersed in Tissue Freezing Medium (EMS) and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. After cryo-sectioning, 5 µm sections were fixed with10% formalin for 2 min then stained with Periodic Acid Schiff and Hematoxylin (PAS/H). For immunofluorescent staining, the sections were blocked with 5% normal goat serum/PBS, stained with rat monoclonal anti-neutrophil primary antibody (NIMP-R14; specific for Ly-6G and Ly-6C) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rat secondary antibody (Invitrogen) and mounted in Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories). For quantitative analysis, images were taken using a Leica DMI 6000B inverted microscope, and the number of neutrophils in each section was digitally quantified using the imaging program MetaMorph (Molecular Devices). Briefly, the number of pixels in a region containing the dorsal epithelial portion of the tongue was counted. A threshold value was then assigned which corresponds to a minimum fluorescent value of a neutrophil. The number of pixels at or above this threshold was determined and a percentage of fluorescent pixels determined by dividing by total overall number of pixels.

Generation of chimera mice

Lethally irradiated mice (exposed to a Cesium-139 γ-radiation source for a total full body dose of 900 rads) received 5×106 bone marrow cells from pooled donor mice via tail vein injection and allowed to recover for 4 weeks.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using commercial software (GraphPad) and Student's two-sample independent t tests or Mann Whitney U tests were used for comparative statistical analysis of qPCR, ELISA, and quantitative fungal load data. Comparison of survival curves was done using a mean Logrank test. P values are presented when statistical significance was observed (significance set at P≤0.05 at a confidence interval of 95%).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. WisplinghoffHBischoffTTallentSMSeifertHWenzelRP 2004 Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis 39 309 317

2. JarvisKGDonnenbergMSKaperJBJarvisWR 1995 Predominant pathogens in hospital infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92 1664 1668

3. FraserVJJonesMDunkelJStorferSMedoffG 1992 Candidemia in a tertiary care hospital: epidemiology, risk factors, and predictors of mortality. Clin Infect Dis 15 414 421

4. GantnerBNSimmonsRMUnderhillDM 2005 Dectin-1 mediates macrophage recognition of Candida albicans yeast but not filaments. Embo J 24 1277 1286

5. BrownGDTaylorPRReidDMWillmentJAWilliamsDL 2002 Dectin-1 is a major beta-glucan receptor on macrophages. J Exp Med 196 407 412

6. HiseAGTomalkaJGanesanSPatelKHallBA 2009 An essential role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in host defense against the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe 5 487 497

7. GowNANeteaMGMunroCAFerwerdaGBatesS 2007 Immune recognition of Candida albicans beta-glucan by dectin-1. J Infect Dis 196 1565 1571

8. MariathasanSMonackDM 2007 Inflammasome adaptors and sensors: intracellular regulators of infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 7 31 40

9. QuYFranchiLNunezGDubyakGR 2007 Nonclassical IL-1 beta secretion stimulated by P2X7 receptors is dependent on inflammasome activation and correlated with exosome release in murine macrophages. J Immunol 179 1913 1925

10. TschoppJMartinonFBurnsK 2003 NALPs: a novel protein family involved in inflammation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4 95 104

11. DinarelloCA 1996 Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood 87 2095 2147

12. MartinonFBurnsKTschoppJ 2002 The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell 10 417 426

13. BurckstummerTBaumannCBlumlSDixitEDurnbergerG 2009 An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome. Nat Immunol 10 266 272

14. Fernandes-AlnemriTYuJWDattaPWuJAlnemriES 2009 AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature 458 509 513

15. HornungVAblasserACharrel-DennisMBauernfeindFHorvathG 2009 AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature 458 514 518

16. RobertsTLIdrisADunnJAKellyGMBurntonCM 2009 HIN-200 proteins regulate caspase activation in response to foreign cytoplasmic DNA. Science 323 1057 1060

17. MeylanETschoppJKarinM 2006 Intracellular pattern recognition receptors in the host response. Nature 442 39 44

18. HalleAHornungVPetzoldGCStewartCRMonksBG 2008 The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat Immunol 9 857 865

19. DuewellPKonoHRaynerKJSiroisCMVladimerG 2010 NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 464 1357 1361

20. MariathasanSWeissDSNewtonKMcBrideJO'RourkeK 2006 Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature 440 228 232

21. MartinonFPetrilliVMayorATardivelATschoppJ 2006 Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 440 237 241

22. DostertCPetrilliVVan BruggenRSteeleCMossmanBT 2008 Innate immune activation through Nalp3 inflammasome sensing of asbestos and silica. Science 320 674 677

23. ZhouRYazdiASMenuPTschoppJ 2010 A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 469 221 225

24. HornungVBauernfeindFHalleASamstadEOKonoH 2008 Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol 9 847 856

25. MorishigeTYoshiokaYInakuraHTanabeAYaoX 2010 The effect of surface modification of amorphous silica particles on NLRP3 inflammasome mediated IL-1beta production, ROS production and endosomal rupture. Biomaterials 31 6833 6842

26. MartinonF 2010 Signaling by ROS drives inflammasome activation. Eur J Immunol 40 616 619

27. SchroderKZhouRTschoppJ 2010 The NLRP3 inflammasome: a sensor for metabolic danger? Science 327 296 300

28. MartinonFAgostiniLMeylanETschoppJ 2004 Identification of bacterial muramyl dipeptide as activator of the NALP3/cryopyrin inflammasome. Curr Biol 14 1929 1934

29. GrossOPoeckHBscheiderMDostertCHannesschlagerN 2009 Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature 459 433 436

30. VinzingMEitelJLippmannJHockeACZahltenJ 2008 NAIP and Ipaf control Legionella pneumophila replication in human cells. J Immunol 180 6808 6815

31. AkhterAGavrilinMAFrantzLWashingtonSDittyC 2009 Caspase-7 activation by the Nlrc4/Ipaf inflammasome restricts Legionella pneumophila infection. PLoS Pathog 5 e1000361

32. MariathasanSNewtonKMonackDMVucicDFrenchDM 2004 Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature 430 213 218

33. MiaoEAMaoDPYudkovskyNBonneauRLorangCG 2010 Innate immune detection of the type III secretion apparatus through the NLRC4 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 3076 3080

34. SutterwalaFSMijaresLALiLOguraYKazmierczakBI 2007 Immune recognition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mediated by the IPAF/NLRC4 inflammasome. J Exp Med 204 3235 3245

35. FranchiLAmerABody-MalapelMKannegantiTDOzorenN 2006 Cytosolic flagellin requires Ipaf for activation of caspase-1 and interleukin 1beta in salmonella-infected macrophages. Nat Immunol 7 576 582

36. KumarHKumagaiYTsuchidaTKoenigPASatohT 2009 Involvement of the NLRP3 inflammasome in innate and humoral adaptive immune responses to fungal beta-glucan. J Immunol 183 8061 8067

37. JolySMaNSadlerJJSollDRCasselSL 2009 Cutting edge: Candida albicans hyphae formation triggers activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome. J Immunol 183 3578 3581

38. BasuSQuiliciCZhangHHGrailDDunnAR 2008 Mice lacking both G-CSF and IL-6 are more susceptible to Candida albicans infection: critical role of neutrophils in defense against Candida albicans. Growth Factors 26 23 34

39. GreenblattMBAliprantisAHuBGlimcherLH 2010 Calcineurin regulates innate antifungal immunity in neutrophils. J Exp Med 207 923 931

40. HopeWWDrusanoGLMooreCBSharpALouieA 2007 Effect of neutropenia and treatment delay on the response to antifungal agents in experimental disseminated candidiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51 285 295

41. HuangWNaLFidelPLSchwarzenbergerP 2004 Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J Infect Dis 190 624 631

42. ContiHRShenFNayyarNStocumESunJN 2009 Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med 206 299 311

43. van de VeerdonkFLMarijnissenRJKullbergBJKoenenHJChengSC 2009 The macrophage mannose receptor induces IL-17 in response to Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe 5 329 340

44. ZelanteTDe LucaABonifaziPMontagnoliCBozzaS 2007 IL-23 and the Th17 pathway promote inflammation and impair antifungal immune resistance. Eur J Immunol 37 2695 2706

45. LeibundGut-LandmannSGrossORobinsonMJOsorioFSlackEC 2007 Syk - and CARD9-dependent coupling of innate immunity to the induction of T helper cells that produce interleukin 17. Nat Immunol 8 630 638

46. FengZJiangBChandraJGhannoumMNelsonS 2005 Human beta-defensins: differential activity against candidal species and regulation by Candida albicans. J Dent Res 84 445 450

47. BalsR 2000 Epithelial antimicrobial peptides in host defense against infection. Respiratory Research 1 141 150

48. DossMWhiteMRTecleTHartshornKL 2010 Human defensins and LL-37 in mucosal immunity. J Leukoc Biol 87 79 92

49. ElssnerADuncanMGavrilinMWewersMD 2004 A novel P2X7 receptor activator, the human cathelicidin-derived peptide LL37, induces IL-1 beta processing and release. J Immunol 172 4987 4994

50. YamamotoYKleinTWFriedmanHKimuraSYamaguchiH 1993 Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor potentiates anti-Candida albicans growth inhibitory activity of polymorphonuclear cells. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 7 15 22

51. SaunusJMWagnerSAMatiasMAHuYZainiZM 2010 Early activation of the interleukin-23-17 axis in a murine model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Mol Oral Microbiol 25 343 356

52. DryginDKooSPereraRBaroneSBennettCF 2005 Induction of toll-like receptors and NALP/PAN/PYPAF family members by modified oligonucleotides in lung epithelial carcinoma cells. Oligonucleotides 15 105 118

53. McCallSHSahraeiMYoungABWorleyCSDuncanJA 2008 Osteoblasts express NLRP3, a nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat region containing receptor implicated in bacterially induced cell death. J Bone Miner Res 23 30 40

54. DinarelloCA 1992 The biology of interleukin-1. Chem Immunol 51 1 32

55. DinarelloCA 1997 Proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines as mediators in the pathogenesis of septic shock. Chest 112 321S 329S

56. GlaccumMBStockingKLCharrierKSmithJLWillisCR 1997 Phenotypic and functional characterization of mice that lack the type I receptor for IL-1. J Immunol 159 3364 3371

57. DinarelloCA 2000 Interleukin-18, a proinflammatory cytokine. Eur Cytokine Netw 11 483 486

58. FantuzziGDinarelloCA 1999 Interleukin-18 and interleukin-1 beta: two cytokine substrates for ICE (caspase-1). J Clin Immunol 19 1 11

59. OmotoYYamanakaKTokimeKKitanoSKakedaM 2010 Granzyme B is a novel interleukin-18 converting enzyme. J Dermatol Sci 59 129 135

60. OmotoYTokimeKYamanakaKHabeKMoriokaT 2006 Human mast cell chymase cleaves pro-IL-18 and generates a novel and biologically active IL-18 fragment. J Immunol 177 8315 8319

61. GhoshSHoweNVolkKTatiSNickersonKW 2010 Candida albicans cell wall components and farnesol stimulate the expression of both inflammatory and regulatory cytokines in the murine RAW264.7 macrophage cell line. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 60 63 73

62. KullbergBJNeteaMGVonkAGvan der MeerJW 1999 Modulation of neutrophil function in host defense against disseminated Candida albicans infection in mice. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 26 299 307

63. RegoDKumarANilchiLWrightKHuangS 2011 IL-6 Production Is Positively Regulated by Two Distinct Src Homology Domain 2-Containing Tyrosine Phosphatase-1 (SHP-1)-Dependent CCAAT/Enhancer-Binding Protein {beta} and NF-{kappa}B Pathways and an SHP-1-Independent NF-{kappa}B Pathway in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages. J Immunol 186 5443 5456

64. SuLZhaoZBouchardPBanvilleDFischerEH 1996 Positive effect of overexpressed protein-tyrosine phosphatase PTP1C on mitogen-activated signaling in 293 cells. J Biol Chem 271 10385 10390

65. AtkinsonKJRaoRK 2001 Role of protein tyrosine phosphorylation in acetaldehyde-induced disruption of epithelial tight junctions. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 280 G1280 1288

66. ValoreEVParkCHQuayleAJWilesKRMcCrayPBJr 1998 Human beta-defensin-1: an antimicrobial peptide of urogenital tissues. J Clin Invest 101 1633 1642

67. McCrayPBJrBentleyL 1997 Human airway epithelia express a beta-defensin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 16 343 349

68. GoldmanMJAndersonGMStolzenbergEDKariUPZasloffM 1997 Human beta-defensin-1 is a salt-sensitive antibiotic in lung that is inactivated in cystic fibrosis. Cell 88 553 560

69. SmithJJTravisSMGreenbergEPWelshMJ 1996 Cystic fibrosis airway epithelia fail to kill bacteria because of abnormal airway surface fluid. Cell 85 229 236

70. BraidaLBoniottoMPontilloATovoPAAmorosoA 2004 A single-nucleotide polymorphism in the human beta-defensin 1 gene is associated with HIV-1 infection in Italian children. Aids 18 1598 1600

71. MilaneseMSegatLPontilloAArraesLCde Lima FilhoJL 2006 DEFB1 gene polymorphisms and increased risk of HIV-1 infection in Brazilian children. Aids 20 1673 1675

72. SegatLMilaneseMBoniottoMCrovellaSBernardonM 2006 DEFB-1 genetic polymorphism screening in HIV-1 positive pregnant women and their children. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 19 13 16

73. HuRCXuYJZhangZXNiWChenSX 2004 Correlation of HDEFB1 polymorphism and susceptibility to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Chinese Han population. Chin Med J (Engl) 117 1637 1641

74. KocsisAKLakatosPLSomogyvariFFuszekPPappJ 2008 Association of beta-defensin 1 single nucleotide polymorphisms with Crohn's disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 43 299 307

75. BalsRGoldmanMJWilsonJM 1998 Mouse beta-defensin 1 is a salt-sensitive antimicrobial peptide present in epithelia of the lung and urogenital tract. Infect Immun 66 1225 1232

76. SchroderJMHarderJ 1999 Human beta-defensin-2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 31 645 651

77. JolySMazeCMcCrayPBJrGuthmillerJM 2004 Human beta-defensins 2 and 3 demonstrate strain-selective activity against oral microorganisms. J Clin Microbiol 42 1024 1029

78. SinghPKJiaHPWilesKHesselberthJLiuL 1998 Production of beta-defensins by human airway epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 14961 14966

79. Quinones-MateuMELedermanMMFengZChakrabortyBWeberJ 2003 Human epithelial beta-defensins 2 and 3 inhibit HIV-1 replication. Aids 17 F39 48

80. WeinbergAQuinones-MateuMELedermanMM 2006 Role of human beta-defensins in HIV infection. Adv Dent Res 19 42 48

81. MorrisonGMDavidsonDJDorinJR 1999 A novel mouse beta defensin, Defb2, which is upregulated in the airways by lipopolysaccharide. FEBS Lett 442 112 116

82. RohrlJYangDOppenheimJJHehlgansT 2008 Identification and Biological Characterization of Mouse beta-defensin 14, the orthologue of human beta-defensin 3. J Biol Chem 283 5414 5419

83. den HertogALvan MarleJvan VeenHAVan't HofWBolscherJG 2005 Candidacidal effects of two antimicrobial peptides: histatin 5 causes small membrane defects, but LL-37 causes massive disruption of the cell membrane. Biochem J 388 689 695

84. den HertogALvan MarleJVeermanECValentijn-BenzMNazmiK 2006 The human cathelicidin peptide LL-37 and truncated variants induce segregation of lipids and proteins in the plasma membrane of Candida albicans. Biol Chem 387 1495 1502

85. TurnerJChoYDinhNNWaringAJLehrerRI 1998 Activities of LL-37, a cathelin-associated antimicrobial peptide of human neutrophils. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42 2206 2214

86. AnderssonERydengardVSonessonAMorgelinMBjorckL 2004 Antimicrobial activities of heparin-binding peptides. Eur J Biochem 271 1219 1226

87. Lopez-GarciaBLeePHYamasakiKGalloRL 2005 Anti-fungal activity of cathelicidins and their potential role in Candida albicans skin infection. J Invest Dermatol 125 108 115

88. KandaNIshikawaTKamataMTadaYWatanabeS 2010 Increased serum leucine, leucine-37 levels in psoriasis: positive and negative feedback loops of leucine, leucine-37 and pro - or anti-inflammatory cytokines. Hum Immunol 71 1161 1171

89. NagaokaITamuraHHirataM 2006 An antimicrobial cathelicidin peptide, human CAP18/LL-37, suppresses neutrophil apoptosis via the activation of formyl-peptide receptor-like 1 and P2X7. J Immunol 176 3044 3052

90. TomasinsigLPizziraniCSkerlavajBPellegattiPGulinelliS 2008 The human cathelicidin LL-37 modulates the activities of the P2X7 receptor in a structure-dependent manner. J Biol Chem 283 30471 30481

91. BrozPNewtonKLamkanfiMMariathasanSDixitVM 2010 Redundant roles for inflammasome receptors NLRP3 and NLRC4 in host defense against Salmonella. J Exp Med 207 1745 1755

92. SchroederGNJannNJHilbiH 2007 Intracellular type III secretion by cytoplasmic Shigella flexneri promotes caspase-1-dependent macrophage cell death. Microbiology 153 2862 2876

93. SuzukiTFranchiLTomaCAshidaHOgawaM 2007 Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis, and autophagy via Ipaf and ASC in Shigella-infected macrophages. PLoS Pathog 3 e111

94. AmerAFranchiLKannegantiTDBody-MalapelMOzorenN 2006 Regulation of Legionella phagosome maturation and infection through flagellin and host Ipaf. J Biol Chem 281 35217 35223

95. MiaoEAAlpuche-ArandaCMDorsMClarkAEBaderMW 2006 Cytoplasmic flagellin activates caspase-1 and secretion of interleukin 1beta via Ipaf. Nat Immunol 7 569 575

96. FranchiLStoolmanJKannegantiTDVermaARamphalR 2007 Critical role for Ipaf in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced caspase-1 activation. Eur J Immunol 37 3030 3039

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiológia Infekčné lekárstvo Laboratórium

Článek Genesis of Mammalian Prions: From Non-infectious Amyloid Fibrils to a Transmissible Prion DiseaseČlánek Role of Permissive Neuraminidase Mutations in Influenza A/Brisbane/59/2007-like (H1N1) VirusesČlánek Allelic Variation on Murine Chromosome 11 Modifies Host Inflammatory Responses and Resistance toČlánek Multifaceted Regulation of Translational Readthrough by RNA Replication Elements in a TombusvirusČlánek Latent KSHV Infection of Endothelial Cells Induces Integrin Beta3 to Activate Angiogenic PhenotypesČlánek Controlling Viral Immuno-Inflammatory Lesions by Modulating Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2011 Číslo 12- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Očkování proti virové hemoragické horečce Ebola experimentální vakcínou rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP

- Koronavirus hýbe světem: Víte jak se chránit a jak postupovat v případě podezření?

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Inhibition of Apoptosis and NF-κB Activation by Vaccinia Protein N1 Occur via Distinct Binding Surfaces and Make Different Contributions to Virulence

- Genesis of Mammalian Prions: From Non-infectious Amyloid Fibrils to a Transmissible Prion Disease

- Kaposi's Sarcoma Herpesvirus microRNAs Target Caspase 3 and Regulate Apoptosis

- Nutritional Immunology: A Multi-Dimensional Approach

- Role of Permissive Neuraminidase Mutations in Influenza A/Brisbane/59/2007-like (H1N1) Viruses

- Vaccinomics and Personalized Vaccinology: Is Science Leading Us Toward a New Path of Directed Vaccine Development and Discovery?

- Symbiont Infections Induce Strong Cytoplasmic Incompatibility in the Tsetse Fly

- Allelic Variation on Murine Chromosome 11 Modifies Host Inflammatory Responses and Resistance to

- Computational and Biochemical Analysis of the Effector AvrBs2 and Its Role in the Modulation of Type Three Effector Delivery

- Granzyme B Inhibits Vaccinia Virus Production through Proteolytic Cleavage of Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 4 Gamma 3

- Association of Activating KIR Copy Number Variation of NK Cells with Containment of SIV Replication in Rhesus Monkeys

- Fungal Virulence and Development Is Regulated by Alternative Pre-mRNA 3′End Processing in

- versus the Host: Remodeling of the Bacterial Outer Membrane Is Required for Survival in the Gastric Mucosa

- Follicular Dendritic Cell-Specific Prion Protein (PrP) Expression Alone Is Sufficient to Sustain Prion Infection in the Spleen

- Autophagy Protein Atg3 is Essential for Maintaining Mitochondrial Integrity and for Normal Intracellular Development of Tachyzoites

- Longevity and Composition of Cellular Immune Responses Following Experimental Malaria Infection in Humans

- Sequential Adaptive Mutations Enhance Efficient Vector Switching by Chikungunya Virus and Its Epidemic Emergence

- Acquisition of Pneumococci Specific Effector and Regulatory Cd4 T Cells Localising within Human Upper Respiratory-Tract Mucosal Lymphoid Tissue

- The Meaning of Death: Evolution and Ecology of Apoptosis in Protozoan Parasites

- Deficiency of a Niemann-Pick, Type C1-related Protein in Is Associated with Multiple Lipidoses and Increased Pathogenicity

- Feeding Cells Induced by Phytoparasitic Nematodes Require γ-Tubulin Ring Complex for Microtubule Reorganization

- Eight RGS and RGS-like Proteins Orchestrate Growth, Differentiation, and Pathogenicity of

- Prion Uptake in the Gut: Identification of the First Uptake and Replication Sites

- Nef Decreases HIV-1 Sensitivity to Neutralizing Antibodies that Target the Membrane-proximal External Region of TMgp41

- Multifaceted Regulation of Translational Readthrough by RNA Replication Elements in a Tombusvirus

- A Temporal Role Of Type I Interferon Signaling in CD8 T Cell Maturation during Acute West Nile Virus Infection

- The Membrane Fusion Step of Vaccinia Virus Entry Is Cooperatively Mediated by Multiple Viral Proteins and Host Cell Components

- HIV-1 Capsid-Cyclophilin Interactions Determine Nuclear Import Pathway, Integration Targeting and Replication Efficiency

- Neonatal CD8 T-cell Hierarchy Is Distinct from Adults and Is Influenced by Intrinsic T cell Properties in Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infected Mice

- Two Novel Transcriptional Regulators Are Essential for Infection-related Morphogenesis and Pathogenicity of the Rice Blast Fungus

- Five Questions about Non-Mevalonate Isoprenoid Biosynthesis

- The Human Cytomegalovirus UL11 Protein Interacts with the Receptor Tyrosine Phosphatase CD45, Resulting in Functional Paralysis of T Cells

- Wall Teichoic Acids of Limit Recognition by the Drosophila Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein-SA to Promote Pathogenicity

- A Novel Role for the NLRC4 Inflammasome in Mucosal Defenses against the Fungal Pathogen

- Inflammasome-dependent Pyroptosis and IL-18 Protect against Lung Infection while IL-1β Is Deleterious

- CNS Recruitment of CD8+ T Lymphocytes Specific for a Peripheral Virus Infection Triggers Neuropathogenesis during Polymicrobial Challenge

- Latent KSHV Infection of Endothelial Cells Induces Integrin Beta3 to Activate Angiogenic Phenotypes

- A Receptor-based Switch that Regulates Anthrax Toxin Pore Formation

- Targeting of Heparin-Binding Hemagglutinin to Mitochondria in Macrophages

- Chikungunya Virus Neutralization Antigens and Direct Cell-to-Cell Transmission Are Revealed by Human Antibody-Escape Mutants

- Ce-Duox1/BLI-3 Generated Reactive Oxygen Species Trigger Protective SKN-1 Activity via p38 MAPK Signaling during Infection in

- Structural Elucidation and Functional Characterization of the Effector Protein ATR13

- Controlling Viral Immuno-Inflammatory Lesions by Modulating Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling

- SAMHD1-Deficient CD14+ Cells from Individuals with Aicardi-Goutières Syndrome Are Highly Susceptible to HIV-1 Infection

- Acid Stability of the Hemagglutinin Protein Regulates H5N1 Influenza Virus Pathogenicity

- Cryo Electron Tomography of Herpes Simplex Virus during Axonal Transport and Secondary Envelopment in Primary Neurons

- A Novel Human Cytomegalovirus Locus Modulates Cell Type-Specific Outcomes of Infection

- Juxtamembrane Shedding of AMA1 Is Sequence Independent and Essential, and Helps Evade Invasion-Inhibitory Antibodies

- Pathogenesis and Host Response in Syrian Hamsters following Intranasal Infection with Andes Virus

- IRGM Is a Common Target of RNA Viruses that Subvert the Autophagy Network

- Epstein-Barr Virus Evades CD4 T Cell Responses in Lytic Cycle through BZLF1-mediated Downregulation of CD74 and the Cooperation of vBcl-2

- Quantitative Multicolor Super-Resolution Microscopy Reveals Tetherin HIV-1 Interaction

- Late Repression of NF-κB Activity by Invasive but Not Non-Invasive Meningococcal Isolates Is Required to Display Apoptosis of Epithelial Cells

- Polar Flagellar Biosynthesis and a Regulator of Flagellar Number Influence Spatial Parameters of Cell Division in

- Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 3C Stabilizes Gemin3 to Block p53-mediated Apoptosis

- The Enteropathogenic (EPEC) Tir Effector Inhibits NF-κB Activity by Targeting TNFα Receptor-Associated Factors

- Toward an Integrated Model of Capsule Regulation in

- A Systematic Screen to Discover and Analyze Apicoplast Proteins Identifies a Conserved and Essential Protein Import Factor

- A Host Small GTP-binding Protein ARL8 Plays Crucial Roles in Tobamovirus RNA Replication

- Comparative Pathobiology of Fungal Pathogens of Plants and Animals

- Synergistic Roles of Eukaryotic Translation Elongation Factors 1Bγ and 1A in Stimulation of Tombusvirus Minus-Strand Synthesis

- Engineered Immunity to Infection

- Inflammatory Monocytes and Neutrophils Are Licensed to Kill during Memory Responses

- Sialidases Affect the Host Cell Adherence and Epsilon Toxin-Induced Cytotoxicity of Type D Strain CN3718

- Eurasian-Origin Gene Segments Contribute to the Transmissibility, Aerosol Release, and Morphology of the 2009 Pandemic H1N1 Influenza Virus

- SARS Coronavirus nsp1 Protein Induces Template-Dependent Endonucleolytic Cleavage of mRNAs: Viral mRNAs Are Resistant to nsp1-Induced RNA Cleavage

- Identification and Characterization of a Novel Non-Structural Protein of Bluetongue Virus

- Functional Analysis of the Kinome of the Wheat Scab Fungus

- Norovirus Regulation of the Innate Immune Response and Apoptosis Occurs via the Product of the Alternative Open Reading Frame 4

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Controlling Viral Immuno-Inflammatory Lesions by Modulating Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling

- Fungal Virulence and Development Is Regulated by Alternative Pre-mRNA 3′End Processing in

- Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 3C Stabilizes Gemin3 to Block p53-mediated Apoptosis

- Engineered Immunity to Infection

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy