Severe (complicated) hepatitis A in Cotonou (Benin) concerning an incompletely vaccinated Spanish expatriate

Těžký (komplikovaný) průběh virové hepatitidy A v Cotonou (Benin) u nedostatečně očkovaného pacienta španělského původu

Virová hepatitida A je hlavní příčinou akutní hepatitidy na světě. Její průběh může být fulminantní, hlavně u dospělých. Tato choroba většinou nepředstavuje zásadní zdravotní problém u lidí žijících v endemických oblastech, ale může mít těžký průběh u neočkovaných subjektů ze západních zemí, kteří do takových oblastí cestují. Popisujeme těžký průběh virové hepatitidy A u pacientky španělského původu, která byla nedostatečně očkována proti hepatitidě A a nedávno se přistěhovala do Beninu. Dva měsíce před hospitalizací měla elektivní cholecystektomii pro symptomatickou cholecystolitiázu.

Klíčová slova:

žloutenka – hepatitida A – přistěhování – neúplné (částěčné) očkování

Autoři deklarují, že v souvislosti s předmětem studie nemají žádné komerční zájmy.

Redakční rada potvrzuje, že rukopis práce splnil ICMJE kritéria pro publikace zasílané do biomedicínských časopisů.

Doručeno:

14. 3. 2016

Přijato:

24. 5. 2016

Authors:

A. R. Kpossou 1; K. A. Agbodandé 2; V. Zoundjiekpon 3,4; N. Kodjoh 1

Authors‘ workplace:

Clinique Universitaire d’Hépato-gastroentérologie, Centre National Hospitalier Universitaire Hubert K. Maga, Cotonou, Benin, West Africa

1; Clinique Universitaire de Médecine Interne, Centre National Hospitalier Universitaire Hubert K. Maga, Cotonou, Benin, West Africa

2; Clinique Les Archanges, Davatin/ Porto-Novo, Benin, West Africa

3; Digestive Disease Center, Vitkovice Hospital, Ostrava, Czech Republic

4

Published in:

Gastroent Hepatol 2016; 70(3): 241-243

Category:

Hepatology: Case Report

doi:

https://doi.org/10.14735/amgh2016241

Overview

Viral hepatitis A is a major cause of acute hepatitis in the world. Its progression can be fulminant. Generally, it does not usually pose a major health problem among people living in endemic areas, but can be an important source of morbidity for unvaccinated subjects from western countries travelling in highly endemic areas. We report a severe case of viral hepatitis A concerning a patient of Spanish origin, incompletely vaccinated and recently immigrated in Benin. Two months before hospitalisation, she had an elective cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholecystolithiasis.

Key words:

jaundice – hepatitis A – expatriate – incomplete vaccination

Introduction

Viral hepatitis A (HAV) is a major cause of acute hepatitis in the world [1]. Each year, there are more than 1.5 million new infections with hepatitis A worldwide [2]. The virus is transmitted via the faecal-oral route, usually through inter-human contact or from ingestion of food or contaminated water. The HAV is almost always asymptomatic in children under three years, but usually symptomatic in adults and may be severe (complicated). Very rarely, the HAV may have a fulminant course which may lead to liver failure and death. In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the HAV is endemic with more than half of all children (under five years) contaminated [3]. In endemic areas, the risk of contracting HAV is 90%, usually in childhood. Subjects who once have contracted HAV are immune for life. This is why the World Health Organization recommends no systematic vaccination in people living in areas of high endemicity such as Africa [2,4]. However, subjects travel-ling from Western countries to SSA have a high risk of contracting the disease in the absence of vaccine protection. We report a severe case of HAV in a Spanish-born patient who was incompletely vaccinated and recently immigrated in Benin.

Observation

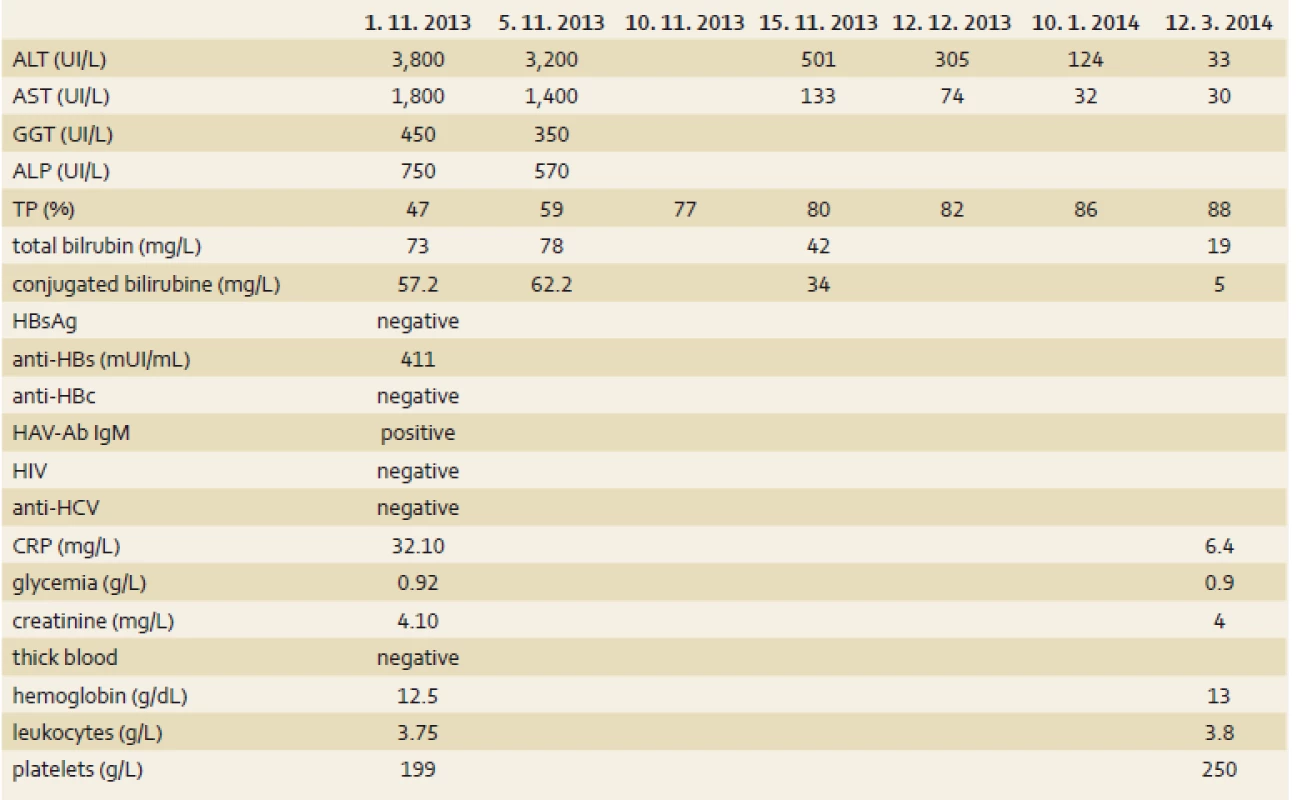

S. E., a 54-year-old woman was admitted in October 1st, 2013 to a hospital in Cotonou for abdominal pain, vomiting, fatigue and low-grade fever lasting for one week. Her history indicated there had been a laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Madrid in September 2013 for symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. She had no history of liver disease or metabolic disease. She didn’t take any drug regularly. The Spanish-born woman who had been living in Benin for 10 months did not have a significant alcohol consumption. She had been vaccinated against hepatitis A(single dose) three years previously on an earlier trip to South America and had also been immunised against hepatitis B. She lost the international vaccination card and didn’t remember the name of the vaccine she took. The symptoms had motivated an antimalarial treatment with the combination of artesunate 200 mg, sulfamethoxazole 500 mg and pyrimethamine 25 mg – normal dose (one tablet per day for three days), without success. During the admission in hospital, the patient was afebrile (after paracetamol), the general condition had altered (because of severe asthenia), her body mass index was 22.9 (weight 64 kg), umbilical perimeter was 81 cm, blood pressure 123/75 mm Hg and heart rate 88/min. It was noted a conjunctival jaundice and tenderness of the epigastrium. The remainder of the examination was normal, there was no sign of hepatic encephalopathy. Laboratory tests (tab. 1) showed a negative thick blood, normal blood count as well as renal function tests, blood electrolytes and creatinine. We noted cytolysis (alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 95N (N – times the upper limit of normal), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 45N), cholestatic jaundice (total bilirubin 7.5N, conjugated bilirubin to 23N, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 7N, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) 10N). The rate of prothrombin was low at 47% and the C-reactive protein amounted to 32 mg/L. Seeing this picture of cholestatic jaundice in a patient shortly after cholecystectomy for stones, the first diagnostic hypothesis raised was residual stones in the bile ducts (cholelithiasis/choledocholithiasis). The second etiological hypothesis was acute viral hepatitis. Abdominal ultrasound showed a homogeneous hepatomegaly without bile duct dilatation of intra - and extrahepatic, and prothrombin time (TP) did not go back after the administration of vitamin K1. Thus, the diagnosis was moving more towards acute viral hepatitis. Serology for hepatitis B immunisation showed anti-HBs antibodies to 411 mIU/mL, the serology for hepatitis C (HCV antibodies) was negative, immunoglobulin M type of anti-HAV antibodies (IgM) was positive. The control in another laboratory confirmed acute HAV. The diagnosis of acute HAV with severe hepatic impairment was retained. The symptomatic treatment was favourable with slow normalisation of hepatic tests and TP. TP was normal after 10 days and bilirubin after three weeks. The normalisation of transaminases was slow (the control after three months showed normal AST but ALT to 3N, after five months transaminases were completely normalised), (tab. 1).

Discussion

This clinical case is interesting for several reasons:

- The background – the patient had undergone a recent cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstones; and therefore seeing the picture of febrile jaundice and abdominal pain, the hypothesis of residual stones in the common bile duct was primary evocated. But this assumption was quickly ruled out in the absence of bile duct dilatation from the abdominal ultrasound, despite not performing any additional radiological examination such as magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. The positivity of IgM HAV led to the diagnosis of acute HAV.

- The subject affected – an incompletely HAV-vaccinated immigrant. Although the HAV does not pose a health problem for people in endemic areas [4], it can be a source of morbidity in travellers from low-prevalence countries [5]. Vaccination is recommended for these subjects. The doses and vac-cination schema depend of the type of used vaccines and traveller’s age. For the isolated vaccines againt HAV (for example Havrix®), it is recommended the first dose of vaccination at least 15 days before departure to the endemic area with a booster 6 – 12 months later [4,6]. Better is two full dose vaccination for adults before traveling to endemic area. The scheme for this vaccination is a 1,440 IU dose in adults (720 IU in children) at months 0 and 6 to 12 [4]. The vaccine is effective against HAV and protection is durable (12 – 25 years) [6]. This vaccination scheme differs in case of combined vaccines (for example boosters 2 months (M2) and 6–12 months (M6–M12) after the first dose in case of vaccines against HAV + HBV and another schema in case of vaccine against HAV + typhoid fever) [4,6]. Our patient had received only one dose of unknown vaccine during a previous trip, so anyway was incompletely protected. In the literature, cases have been reported in incompletely HAV-vaccinated patients [7] and also in fully vaccinated patients reflecting the possible failures of the vaccine [6]. It seems that the vaccine efficacy decreases with age. Wolters et al. had found that vaccination against HAV was only 65% effective in subjects over 40 years of age [8]. They advocated, therefore, to verify vaccine protection in patients over 40 years of age before contact with the virus.

- The last interesting point of this case is its clinical severity, shown by the presence of hepatocellular insufficiency. Indeed, HAV is usually a benign affection with 0.3 – 1.5% mortality [6]. The adult patients usually present with symptomatic forms. Morbidity and mortality increase with age [9]. In subjects aged 40 and over, mortality exceeds 2% [10]. The liver failure and mortality risk factors are age, co-infection with hepatitis B or C and sex (women being at a higher risk) [6]. Our patient had two of these factors (female sex and age) as well as being an incompletely vaccinated immigrant. Fortunately, evolution was spontaneously favourable.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates the importance and the necessity of full immunisation against HAV in patients from Western countries who are travel-ing to highly endemic areas. It would be useful to check the effectiveness of vaccination in subjects over 40 years of age before contact with the virus.

The authors declare they have no potential conflicts of interest concerning drugs, products, or services used in the study.

The Editorial Board declares that the manuscript met the ICMJE „uniform requirements“ for biomedical papers.

Submitted: 14. 3. 2016

Accepted: 24. 5. 2016

Vincent Zoundjiekpon, MD

Digestive Disease Center

Vitkovice Hospital

Zaluzanskeho 1192/ 15

703 84 Ostrava

Czech Republic

vincent.zoundjiekpon@vtn.agel.cz

Sources

1. Traoré KA, Rouamba H, Nébié Y et al. Seroprevalence of fecal-oral transmitted hepatitis A and E virus antibodies in Burkina Faso. Plos One 2012; 7(10): e48125. doi: 10.1371/ journal.pone.0048125.

2. Ehrmann J, Hůlek P, Husa P et al. Hepatologie, virová hepatitida A. 2. vyd. Praha: Garda Publishing 2014 : 245 – 247.

3. Jacobsen KH. Hepatitis A virus in West Africa: is an epidemiological transition beginning? Niger Med J 2014; 55(4): 279 – 284. doi: 10.4103/ 0300-1652.137185.

4. Dupeyron C. Le vaccin contre l’hépatite A: pourquoi il n’a pas sa place en Afrique. Développement et Santé 2012; 200 : 51 – 53.

5. Ciccozzi M, Cella E, Giovanetti M et al. Hepatitis A virus in a medical setting in Madagascar: a lesson for public health. New Microbiol 2015; 38(1): 119 – 120.

6. Oltmann A, Kämper S, Staeck O et al. Fatal outcome of hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection in a traveler with incomplete HAV vaccination and evidence of rift valley fever virus infection. J Clin Microbiol 2008; 46(11): 3850 – 3852. doi: 10.1128/ JCM.01102-08.

7. MacDonald E, Steens A, Stene-Johansen K et al. Increase in hepatitis A in tourists from Denmark, England, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden returning from Egypt, November 2012 to March 2013. Euro Surveill 2013; 18(17): 1 – 6.

8. Wolters B, Junge U, Dziuba S et al. Immunogenicity of combined hepatitis A and B vaccine in elderly persons. Vaccine 2003; 21(25 – 26): 3623 – 3628.

9. World Health Organization. Hepatitis A. Fact sheet N°328. [online]. Available from: http:/ / www.who.int/ mediacentre/ factsheets/ fs328/ en/ .

10. Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP. Prevention of hepatitis A though active or passive immunization. Recommendations of the advisory committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2006; 55(RR07): 1 – 30. [online]. Available from: http:/ / www.cdc.gov/ mmwr/ preview/ mmwrhtml/ rr5507a1.htm.

Labels

Paediatric gastroenterology Gastroenterology and hepatology SurgeryArticle was published in

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

2016 Issue 3

- Possibilities of Using Metamizole in the Treatment of Acute Primary Headaches

- Metamizole at a Glance and in Practice – Effective Non-Opioid Analgesic for All Ages

- Metamizole vs. Tramadol in Postoperative Analgesia

- Spasmolytic Effect of Metamizole

- The Importance of Limosilactobacillus reuteri in Administration to Diabetics with Gingivitis

-

All articles in this issue

- Digestive endoscopy and endotherapy

- Renaissance of cholangiopancreatoscopy and new ways of intraductal endoscopic therapy

- Therapeutic endosonography – current position

- Endoscopic management of sigmoid volvulus

- Neuroendocrine neoplasms in gastroenterologist practice

- First submucosal endoscopic tunnelling resection of a subepithelial tumour (GIST) in the Czech Republic

- Lymphoma mimicking GIST

- Colon stenosis of unexplained etiology

- Utility of a panel of gene mutations and amplifications for estimation of prognosis in patients with gastric cancer

- Recommendation of surgical treatment in patientswith inflammatory bowel diseases – part 3: ulcerative colitis, indications for surgery

- The 38th Czech and Slovak Endoscopic Days

- 15th Czech-Slovak IBD symposium and IBD work ing days, Hořovice 2016

- The selection from international journals

- The Mutaflor® – Escherichia coli (Nissle 1917), serotype O6:K5:H1 – the best researched probiotic available

- Severe (complicated) hepatitis A in Cotonou (Benin) concerning an incompletely vaccinated Spanish expatriate

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Journal archive

- Current issue

- About the journal

Most read in this issue

- Colon stenosis of unexplained etiology

- The Mutaflor® – Escherichia coli (Nissle 1917), serotype O6:K5:H1 – the best researched probiotic available

- Endoscopic management of sigmoid volvulus

- Neuroendocrine neoplasms in gastroenterologist practice