-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Human-Specific Evolution and Adaptation Led to Major Qualitative Differences in the Variable Receptors of Human and Chimpanzee Natural Killer Cells

Natural killer (NK) cells serve essential functions in immunity and reproduction. Diversifying these functions within individuals and populations are rapidly-evolving interactions between highly polymorphic major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I ligands and variable NK cell receptors. Specific to simian primates is the family of Killer cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptors (KIR), which recognize MHC class I and associate with a range of human diseases. Because KIR have considerable species-specificity and are lacking from common animal models, we performed extensive comparison of the systems of KIR and MHC class I interaction in humans and chimpanzees. Although of similar complexity, they differ in genomic organization, gene content, and diversification mechanisms, mainly because of human-specific specialization in the KIR that recognizes the C1 and C2 epitopes of MHC-B and -C. Humans uniquely focused KIR recognition on MHC-C, while losing C1-bearing MHC-B. Reversing this trend, C1-bearing HLA-B46 was recently driven to unprecedented high frequency in Southeast Asia. Chimpanzees have a variety of ancient, avid, and predominantly inhibitory receptors, whereas human receptors are fewer, recently evolved, and combine avid inhibitory receptors with attenuated activating receptors. These differences accompany human-specific evolution of the A and B haplotypes that are under balancing selection and differentially function in defense and reproduction. Our study shows how the qualitative differences that distinguish the human and chimpanzee systems of KIR and MHC class I predominantly derive from adaptations on the human line in response to selective pressures placed on human NK cells by the competing needs of defense and reproduction.

Published in the journal: Human-Specific Evolution and Adaptation Led to Major Qualitative Differences in the Variable Receptors of Human and Chimpanzee Natural Killer Cells. PLoS Genet 6(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001192

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001192Summary

Natural killer (NK) cells serve essential functions in immunity and reproduction. Diversifying these functions within individuals and populations are rapidly-evolving interactions between highly polymorphic major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I ligands and variable NK cell receptors. Specific to simian primates is the family of Killer cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptors (KIR), which recognize MHC class I and associate with a range of human diseases. Because KIR have considerable species-specificity and are lacking from common animal models, we performed extensive comparison of the systems of KIR and MHC class I interaction in humans and chimpanzees. Although of similar complexity, they differ in genomic organization, gene content, and diversification mechanisms, mainly because of human-specific specialization in the KIR that recognizes the C1 and C2 epitopes of MHC-B and -C. Humans uniquely focused KIR recognition on MHC-C, while losing C1-bearing MHC-B. Reversing this trend, C1-bearing HLA-B46 was recently driven to unprecedented high frequency in Southeast Asia. Chimpanzees have a variety of ancient, avid, and predominantly inhibitory receptors, whereas human receptors are fewer, recently evolved, and combine avid inhibitory receptors with attenuated activating receptors. These differences accompany human-specific evolution of the A and B haplotypes that are under balancing selection and differentially function in defense and reproduction. Our study shows how the qualitative differences that distinguish the human and chimpanzee systems of KIR and MHC class I predominantly derive from adaptations on the human line in response to selective pressures placed on human NK cells by the competing needs of defense and reproduction.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells are lymphocytes that contribute to both the immune and reproductive systems. NK cells provide first-line, innate immune defense against infection [1] and cancer [2], and through interaction with dendritic cells [3] help initiate the second-line, adaptive immune response [4]. During embryo implantation and placentation, NK cells control the trophoblast-mediated widening of maternal blood vessels necessary to nourish the fetus throughout pregnancy [5]. Controlling both NK cell development and effector function is a variety of interactions between NK cell receptors and their ligands [6], the class I molecules of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC): called the HLA complex in humans. Some interactions are conserved, such as that between human HLA-E and the CD94:NKG2A receptor [7], whereas others are highly variable, notably those between HLA-A, B, C and killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) [8]. Pointing to the clinical importance of these interactions, various combinations of HLA and KIR factors associate with the outcome of viral infection, susceptibility to autoimmune disease, relapse of leukemia following therapeutic transplantation, and reproductive success [9]–[11].

The human KIR locus combines gene content variability with allelic polymorphism [8], [12]. This diverse family of NK cell receptor genes is restricted to simian primates, having expanded from a single copy KIR3DL gene during the last ∼40–58 million years [13]. In rodents, where KIR genes are expressed in the brain, but not by NK cells [14], the Ly49 gene family independently evolved as a variable family of NK cell receptors for MHC class I [15]. Prosimians have a single, non-functional KIR3DL gene, but a diversified system of CD94 and NKG2 genes [13]. Also having a single KIR3DL gene, cattle expanded and diversified the distantly related KIR3DX gene [16], which in humans is non-functional. This strong element of species-specific evolution likely reflects the variety and inconstancy of selection imposed on NK cells by immune defense and reproduction; the former being essential for individuals to survive, the latter being necessary for the survival of populations and species [17]. In this context of rapidly evolving NK cell receptors, the study of chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, becomes an imperative, not only for clinical studies in which the chimpanzee is the preferred animal model, for example hepatitis C virus infection [18], but also for defining those aspects of NK cell function that are unique to the human species [19].

HLA-A, B, C and G serve as ligands for human KIR [8]. HLA-G expression is restricted to trophoblast and thus dedicated to functions associated with pregnancy [20]. Of the highly polymorphic genes, only HLA-C is present on trophoblast and able to interact with the KIR of uterine NK cells [21]. HLA-A, B and C are expressed by almost all cells of the body and can thus contribute in general to NK cell responses against infection and cancer. Although the chimpanzee has well-defined orthologs of all the human HLA class I genes [22], exploratory studies of chimpanzee KIR cDNA and one KIR haplotype [23], [24], raised intriguing possibilities: first that only a small minority of KIR genes is shared by humans and chimpanzees; and second, that the organization of KIR genes into haplotypes is qualitatively different in the two species. To test these hypotheses we performed extensive analysis of chimpanzee KIR haplotype structure and variation, permitting definitive genetic and functional comparison with the human KIR system.

Results

Chimpanzee KIR haplotypes do not divide into functional groups like human A and B haplotypes

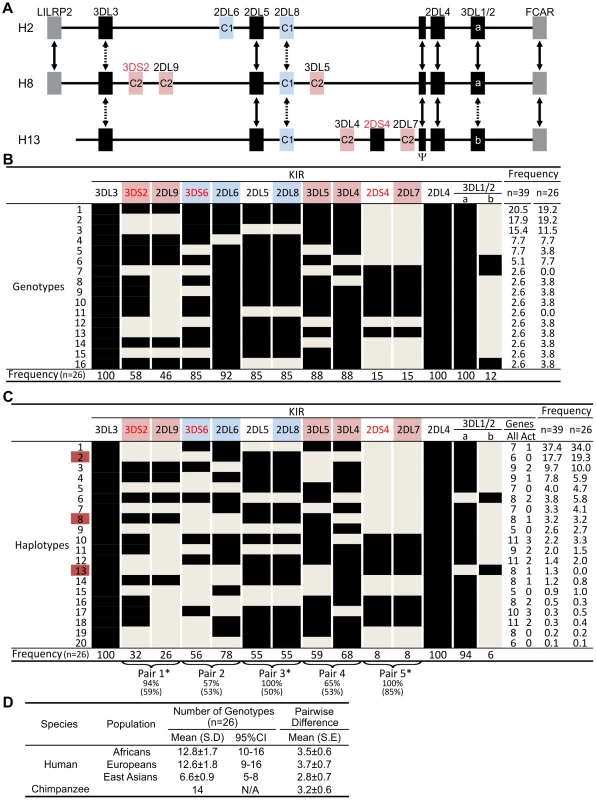

From sequence analysis of cDNA [23] and three KIR haplotypes (Figure 1A), we defined 13 chimpanzee KIR genes. Typing a panel of 39 individuals identified 16 genotypes (Figure 1B), for which the component KIR haplotypes were deduced (Figure 1C). Both in number and gene content difference, chimpanzee KIR genotypes are within the human range (Figure 1D). Common to the human and chimpanzee KIR loci are three conserved, framework regions separated by centromeric and telomeric intervals of variable gene content [25]. Whereas the human variable KIR genes are evenly distributed between the two intervals, their chimpanzee counterparts are restricted to the centromeric interval, leaving the telomeric interval both short and empty (Figure 2A).

Fig. 1. Chimpanzee and human KIR genotypes are comparably diverse.

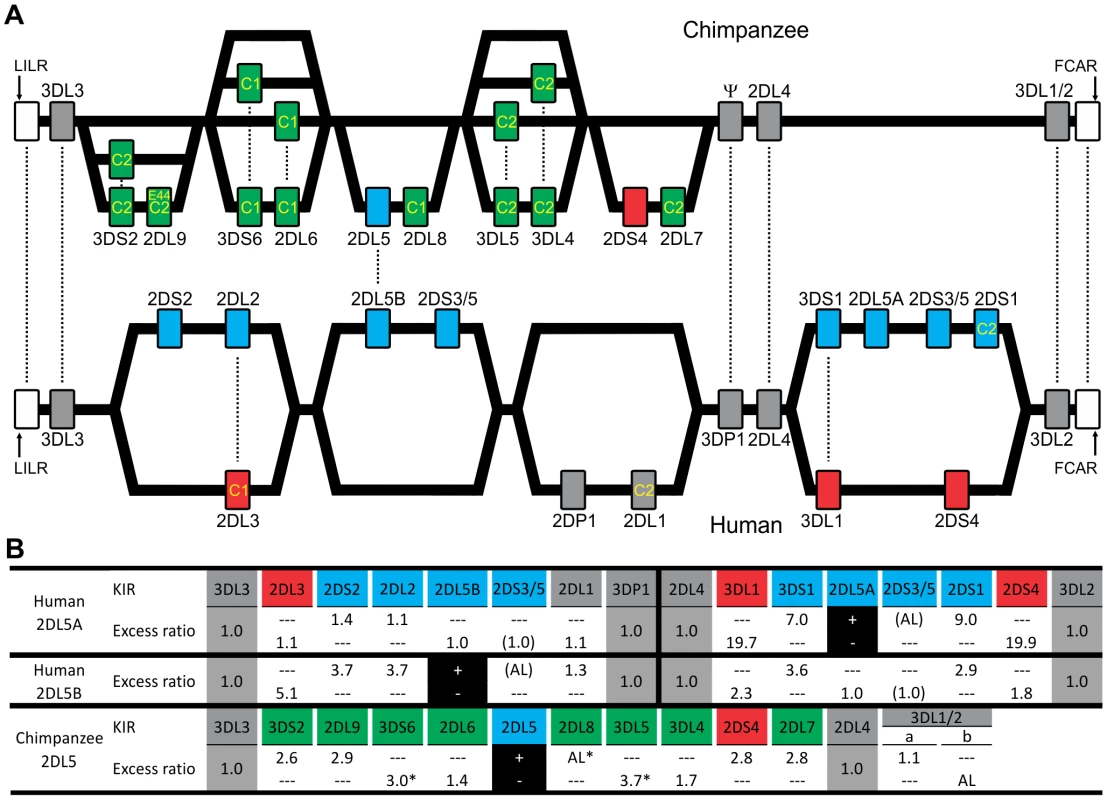

(A) Shows KIR gene content of three chimpanzee haplotypes. Arrows indicate equivalent genes; dotted arrows, divergent alleles. Lineage III KIR are colored blue (MHC-C1 specific) or pink (MHC-C2 specific); names of activating KIR are red. Ψ, KIR pseudogene. Haplotype names are from panel (C). The flanking non-KIR genes are colored gray. (B) KIR gene content was assessed in 39 chimpanzees. The 16 distinct genotypes characterized and their frequencies are given here. Thirteen KIR loci defined by analysis of cDNA [23] and of the three haplotype sequences of panel A were investigated. KIR phenotype and genotype frequencies are also given for the subgroup of 26 unrelated individuals. (C) Component KIR haplotypes were deduced from the genotype data presented in panel B, and presented here with their estimated frequencies. KIR gene and haplotype frequencies are also given for the subgroup of 26 unrelated individuals. ‘Genes’ gives the number of KIR per haplotype (‘All’), and the number of activating receptor genes (‘Act’). Chimpanzee KIR haplotype diversity stems from recombination involving five pairs of variable KIR: for each pair the top percentage indicates the observed ‘pairing frequency’ (genes both present or both absent) and the bottom percentage is the expected ‘pairing frequency’ under random distribution. *, significant linkage disequilibrium (p<0.001). Red boxes denote the sequenced haplotypes. (D) Both in number and gene content difference, chimpanzee KIR genotypes are within the human range (see Materials and Methods for details). CI, confidence interval. Fig. 2. Human and chimpanzee KIR haplotypes differ in their organization and generation of diversity.

(A) Diversity in chimpanzee arises from the variable recombination of seven units in the centromeric region, whereas a similar number of human gene-content motifs is divided between the centromeric and telomeric regions. C1 or C2 specificity for each lineage III KIR is shown. Dotted lines indicate orthologs (between species) or alleles (within species). Ψ, KIR pseudogene. (A–B) KIR associated with A haplotypes are red; KIR associated with B haplotypes are blue. Chimpanzee KIR having no human strict ortholog are colored green. (B) Linkage to KIR2DL5 in human and chimpanzee. For each KIR an association ratio with 2DL5+/− haplotypes is given (for example KIR3DS1 is seven times more common on 2DL5A+ haplotypes than on 2DL5A− haplotypes); 2DS3/5 ratios are given in parenthesis to reflect an assumption (see Materials and Methods for details). Black boxes, reference gene for the linkage analysis (+, presence; −, absence). Ratios for framework KIR are shaded in gray. AL, absolute linkage. Linkage disequilibrium was assessed in chimpanzee and (*) indicates significance (p<0.001). Although human and chimpanzee each have ten variable KIR genes, only 2DL5 and 2DS4 are held in common. These two genes distinguish the human group A and B KIR haplotypes, a difference correlating with a wide range of clinical effects [10]. KIR2DL5 is the only inhibitory KIR restricted to B haplotypes, 2DS4 the only activating KIR of A haplotypes (Figure 2A and 2B). Whereas human 2DS4 is restricted to the telomeric region and present on ∼50% of KIR haplotypes, chimpanzee 2DS4 is restricted to the centromeric region (Figure 2B) and present on only 8% of haplotypes (Figure 1C). Also varying between species are the location of 2DL5 and its linkage disequilibrium (LD). Restricted to the centromeric region, chimpanzee 2DL5 has absolute LD with inhibitory KIR2DL8, whereas human 2DL5 has absolute LD with activating KIR2DS3/S5 and is alternatively found in the centromeric region, the telomeric region, or both (Figure 2A and 2B). Thus human-specific evolution of the KIR locus involved ‘colonization’ of the telomeric region of the KIR locus, with assembly of A and B haplotype gene-content motifs around the 2DS4 and 2DL5 genes, respectively. Consequently, human KIR haplotypes all have 2DS4 and/or 2DL5, while almost half the chimpanzee haplotypes (44%; arithmetic sum of the individual frequencies of haplotypes 1, 6, 9 and 15) lack both of them.

Chimpanzee lineage III KIR are more numerous and functional MHC-C receptors than their human counterparts

The ten variable chimpanzee KIR form five pairs within the centromeric region (Figure 1C and Figure 2A). As shown in Figure 1B, Pairs 2, 3 and 4 at high phenotype frequency are flanked on the centromeric side by Pair 1 of intermediate frequency and on the telomeric side by Pair 5 of low frequency. Because Pairs 1, 3, and 5 have absolute or very high LD (Figure 1C), gene-content diversity of chimpanzee KIR haplotypes derives from asymmetric recombination between seven units, these three high LD pairs and the individual genes of Pairs 2 and 4. In humans, a similar number of units is divided between the centromeric and telomeric regions and separated by a unique and repetitive sequence that facilitates symmetric recombination [26] (Figure 2A). Thus recombination of centromeric and telomeric gene-content motifs, a major component of human KIR haplotype diversification, is not a significant feature of the chimpanzee system.

Eight variable chimpanzee lineage III KIR have no human equivalents and represent lineage III KIR encoding high-avidity receptors for the C1 and C2 epitopes of MHC-C. Two inhibitory and one activating KIR are C1-specific, four inhibitory and one activating KIR are C2-specific [27], [28]. Contrasting with this battery of potent MHC-C receptors is the set of six variable human lineage III KIR without chimpanzee equivalents. These comprise high-avidity inhibitory receptors for C1 (2DL2/3) and C2 (2DL1), a C2 receptor with lower avidity (2DS1) and three KIR with no detectable binding to HLA class I (2DS2, 2DS3, and 2DS5) [29]. The lineage III KIR expansion associated with hominid evolution and ‘first’ detected in the orangutan [30] was further elaborated in chimpanzee and human, but in distinctive ways. Whereas the chimpanzee retains a diversity of strong inhibitory and activating MHC-C receptors, the human system is characterized by a reduced number of inhibitory receptors and a variety of activating receptors with loss of function [29].

Recombination of ligand-binding and signaling domains diversifies chimpanzee KIR function

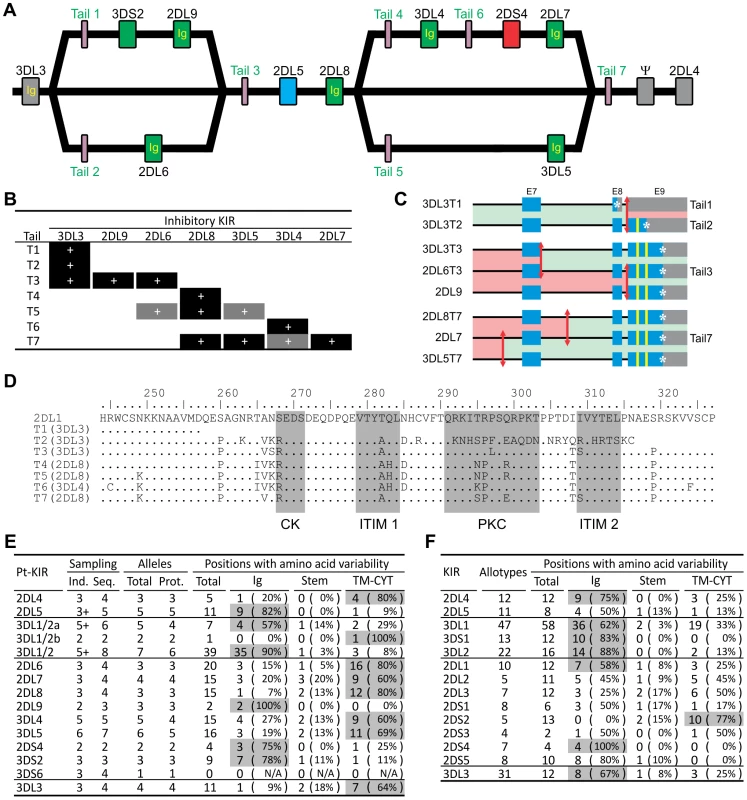

The 3DL3 and 2DL8 genes are represented on each of the sequenced KIR haplotypes by alleles that encode the same extracellular domains but different cytoplasmic tails (Figure 3A). In reciprocal manner, the same cytoplasmic tail can be associated with different extracellular domains. Thus, the T3 tail is alternatively associated with the extracellular domains of 3DL3, 2DL9 and 2DL6, as is the T7 tail with the 2DL8, 3DL5 and 2DL7 extracellular domains (Figure 3A and 3B). These chimeric forms are the products of intergenic recombination that brought together the extracellular domains of one KIR with the signaling domain of another. The effect of this mechanism is to generate receptors with altered inhibitory signaling function (Figure 3C and 3D). For example, of the three tails associated with 3DL3, T1 has no immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM), T2 has one, and T3 has two. The extent this occurred among the three haplotypes sequenced, points to the prevalence of the phenomenon and its significant contribution to the functional diversity of inhibitory chimpanzee KIR. Consistent with this thesis, sequence variability in the chimpanzee lineage III inhibitory KIR concentrates in the signaling domain (Figure 3E). However, that is not the case for human lineage III KIR, for which tail-swapping has principally served to convert inhibitory to activating receptors [31], and allotypic variability more evenly distributes between ligand-binding and signaling domains (Figure 3F). Consequently, chimpanzee 3DL3 and inhibitory lineage III KIR display more allelic variability than their human counterparts (Figure 3E and 3F). Particularly striking is 3DL3, for which four chimpanzee allotypes have 11 variable positions, compared to 12 in 31 human allotypes [32].

Fig. 3. Reassorting inhibitory signaling and ligand-binding functions contributes to chimpanzee but not human KIR allelic diversity.

(A) Structural relationships between the three chimpanzee haplotypes. ‘Ig’ and ‘Tail’ refer to the exons encoding the immunoglobulin-like domains and the cytoplasmic tail, respectively. Colors for the genes are as in Figure 2. (B) Chimpanzee inhibitory KIR associate with different cytoplasmic tails on different haplotypes. Black boxes, combinations seen in genomic sequences; gray boxes, additional combinations seen in cDNA sequences (see Figure S13). (C) Mapping of the recombination points for the KIR genes with tails 1–3 and 7. Red arrows represent recombination breakpoints. Regions colored in green are equivalent (allelic) in the two genes. Blue denotes coding regions, gray the 3′UTR region, and yellow the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs (ITIM). *, stop codon. (D) Sequence diversity of the seven groups of chimpanzee cytoplasmic tails. One sequence for each group is displayed. Human 2DL1 is used as the reference. Highlighted in gray are the two ITIM, the protein kinase C motif (PKC) and the casein kinase motif (CK) [38]. (E–F) Chimpanzee (E) and human (F) KIR polymorphism. Domains contributing >50% of the variability are shaded in gray. Ind., estimate of the number of individuals sampled (‘+’, minimum number). Seq., number of nucleotide sequences. Prot., number of amino acid sequences. Chimpanzee sequences are given in Figure S14. Human KIR polymorphism was obtained from the IPD-KIR database [32]. Divergent sublineages of lineage III KIR encode human and chimpanzee MHC-C receptors

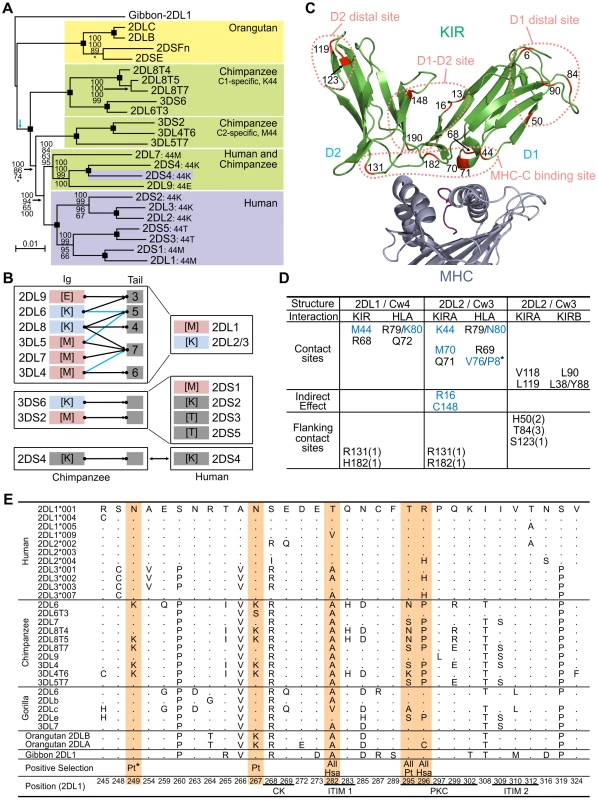

The genomic regions containing the lineage I, II, and V KIR genes are shared by human and chimpanzee KIR haplotypes (Figure 2A, Figure S1, and Figure S2). In contrast, the regions containing the lineage III KIR genes have diverged to form four sublineages (Figure 4A). Of these, two are chimpanzee-specific, one is human-specific and one is shared. The two chimpanzee-specific sublineages correspond precisely to C1 - and C2-specific KIR. Functionally, these sublineages were lost during human evolution (a non-functional remnant is KIR3DP1), being replaced by the human-specific sublineage that includes both C1 - and C2-specific receptors. The shared sublineage includes additional chimpanzee inhibitory C2 receptors and 2DS4. The differences in the MHC-C system of receptors in human and chimpanzee are seen to be mainly the result of human-specific evolution. These differences alter basic functional characteristics such as the number and avidity of receptors (Figure 4B), suggesting that natural selection played distinctive roles in the evolution of human and chimpanzee lineage III KIR.

Fig. 4. Natural selection differentially diversified human and chimpanzee lineage III KIR.

(A) Phylogenetic analysis of lineage III KIR genomic sequences. The Bayesian tree topology is displayed and rooted with the gibbon sequence (blue arrow: midpoint root). Support is indicated for each node: Bayesian, maximum-likelihood, parsimony and neighbor-joining (top to bottom). Black squares: support is 100 with the four methods. *, support<50. (B) Lineage III KIR content in human and chimpanzee. Chimpanzee KIR are represented as a combination of Ig and tails with MHC specificity-determining residue 44 in the D1 domain in brackets. KIR are colored blue (MHC-C1 specific) or pink (MHC-C2 specific). Arrows indicates genomic (black) or cDNA (blue) Ig-Tail combinations (Figure 3B). (C) D1 and D2 positively selected positions (M8 p>0.95, Figure 5) are marked in red in the KIR2DL2-HLA-Cw3 three-dimensional structure (PDB file 1EFX [34] represented). (D) KIR-MHC and KIR-KIR interactions for the selected residues: KIR2DL1-HLA-Cw4 [33] (left); KIR2DL2-HLA-Cw3 [34] (center), and KIRA-KIRB (right). Mutations at residues colored blue can disrupt KIR-HLA interaction [8], [46]. In parenthesis is the number of residues to the nearest contact site. *, P8 is the eighth residue in the peptide bound by HLA-C. (E) Diversity in the cytoplasmic tails of inhibitory lineage III KIR. Positions with amino acid variation are represented (reference sequence is KIR2DL1). Orange highlight denotes positively selected position (M8 p>0.95) in one or more of three datasets comprising hominoid (‘All’), chimpanzee (‘Pt’) or human (‘Hsa’) sequences. Positions underlined correspond to the functional sites described in Figure 3D. *, only detected in the complete dataset (Figure 5). Ligand-binding, KIR-KIR interaction, and signaling function were all subject to natural selection

Evidence of positive diversifying selection was obtained for 16 positions in the ligand-binding domains of hominoid lineage III KIR (Figure 4C and Figure 5A). These positions cluster at four sites on the molecular surface: the MHC-C binding site, a site near the hinge where D1 and D2 interact (D1–D2 site), a site on D1 away from the interactions with D2 and MHC-C (D1 distal site), and a similarly distal site on D2 (D2 distal site).

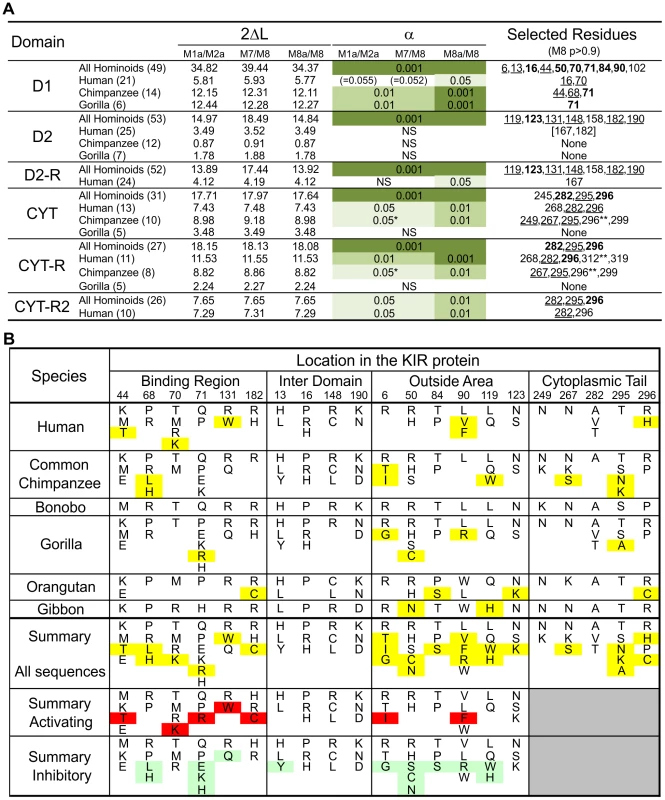

Fig. 5. Analysis of positive selection in the lineage III KIR.

(A) Likelihood ratio tests and detection of the D1, D2 and cytoplasmic tail (CYT) positions positively selected. Analysis was performed for all the hominoid sequences together and with just the human or chimpanzee or gorilla sequences; the number of sequences in each analysis is indicated in parentheses. For the cytoplasmic tail analyses all the sequences with an early termination (short tail KIR) were excluded. In addition, because of the risk of recombination between exon 7 and exon 8 (see Figure 3C) a reduced dataset was also created (CYT-R) where the nine amino acids encoded by exon 7 were discarded and the Pt-KIR2DL9 amino acids encoded by exon 8 were masked. Similarly, because the cytoplasmic tail of KIR2DL3*007 and the D2 domain of KIR2DL1*004 showed evidence of gene conversion, additional analyses were performed where these sequences were discarded: datasets CYT-R2 and D2-R, respectively. 2ΔL, two times the difference in likelihood between the models allowing for positive selection (M2a and M8) and the models that do not (null models: M1a, M7 and M8a). The significance level (α) is indicated when the null models were significantly rejected. NS, not significant. *: α∼0.01. When significant evidence of positive diversifying selection was obtained, the residues detected with model M8 were listed (underlined residues: p>0.95; boldened residues: p>0.99; **: p∼0.90). (B) Residues observed at the positively selected positions in the D1, D2 and CYT domains. Amino acids unique to one species are highlighted in yellow. In the summary section, amino acids only found on activating KIR are highlighted in red while those only found on inhibitory KIR are highlighted in green. Crystallography defined the MHC-C binding site [33], [34], and mutagenesis identified D1–D2 sites that modulate avidity for MHC-C (Figure 4D). In both sites there was species-specific selection. Residues 44, 68 and 71 were subject to selection in chimpanzee, compared to residues 16 and 70 in humans. At positions 44, 68, and 71, chimpanzee inhibitory receptors have residues absent from their human counterparts, while the human evolution of low-avidity activating KIR introduced unique human-specific residues at positions 44, 70 and 131 (Figure 5B). Thus the independent evolution of human and chimpanzee lineage III KIR involved fixation, under natural selection, of species-specific residues at sites affecting binding of MHC class I ligands.

Five of the 16 selected positions in D1 and D2 are implicated in the intermolecular KIR-KIR interaction observed in the KIR2DL2-HLA-Cw3 structure [34]: positions 119 and 90 are direct contact sites and residues 50, 84 and 123 are only 1–3 residues away from a contact site (Figure 4D). This distribution points to such KIR-KIR interactions being physiologically relevant, possibly contributing to the aggregation of receptors and ligands observed in the synapse between an NK cell and its target cell [35].

In the cytoplasmic tail, positive diversifying selection targeted three positions (282, 295, and 296) (Figure 4E and Figure 5A). Position 282 is in the first ITIM that initiates inhibitory KIR signals by recruiting the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 [36]. Favoring such recruitment is alanine 282 [37], fixed in chimpanzee but present in a minority of human lineage III KIR. Residues 295 and 296 are part of the protein kinase C (PKC) site, comprising residues 291–303. Phosphorylation of serine 298 attenuates inhibitory function [38] and is favored by arginine or lysine residues within the PKC site [39], [40]. In chimpanzee, but not human KIR, positions 295, 296 and 299 (also selected in chimpanzee KIR: p>0.9, Figure 5A) have residue combinations that variably involve arginine and lysine, indicating a modulation of affinity for PKC.

Recurrent loss and gain of MHC-B carrying the C1 epitope recognized by lineage III KIR

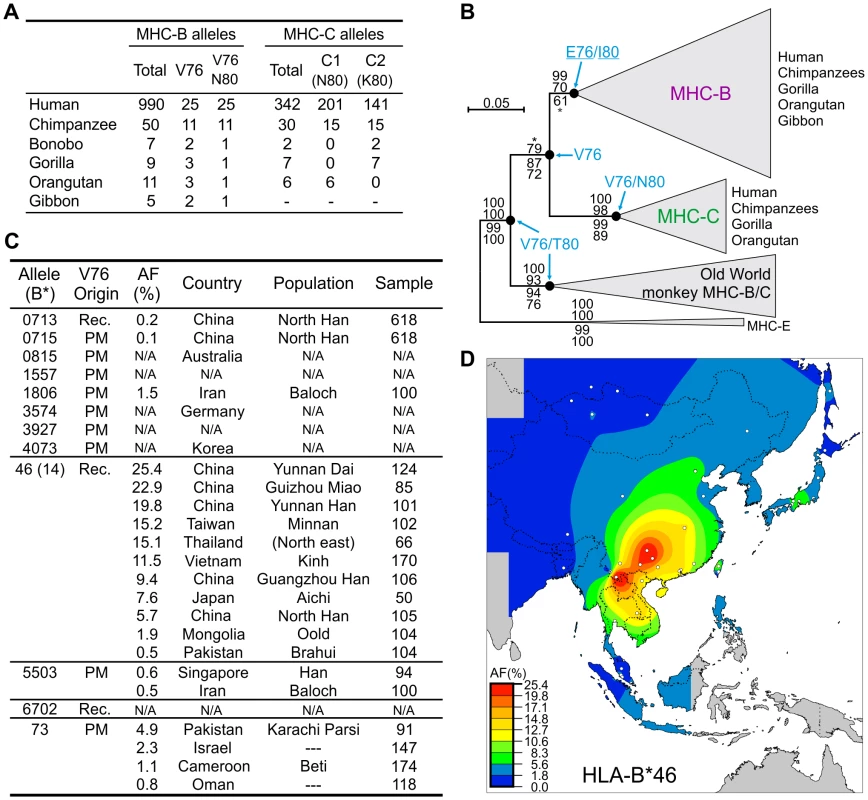

Lineage III KIR recognize the C1 and C2 epitopes of MHC class I. C2 depends upon valine 76 (V76) and lysine 80 (K80), a motif restricted to a subset of MHC-C allotypes. C1 depends upon V76 and asparagine 80 (N80), a motif present in subsets of MHC-C and -B allotypes; 22% of chimpanzee MHC-B allotypes have C1, compared to only 2.5% for HLA-B (Figure 6A). Ancestral sequence reconstruction indicates that the last common ancestor of MHC-B and -C had V76, which remained fixed during MHC-C evolution, but was replaced by glutamic acid (E76) during MHC-B evolution (Figure 6B). The V76 observed in modern MHC-B allotypes arose de novo, by reversion from E76, with at least fifteen such events having occurred in hominoids (Figure S3).

Fig. 6. Emergence of MHC-C affected the functional interactions between MHC-B and lineage III KIR.

(A) Distribution of the hominoid MHC-B and -C residues that affect interaction with lineage III KIR. (B) Phylogenetic analysis of the MHC-B and -C sequences (α1–α3 domains). The maximum-likelihood tree topology was used for the display with PAML M0 branch lengths. The tree was rooted with MHC-E and support is given at nodes: Bayesian, maximum-likelihood, neighbor-joining and parsimony (top to bottom). *, support <95 (Bayesian) or <50 (parsimony). Ancestral residues were reconstructed for positions 76 and 80 and are given for five nodes where model M0 p>0.95 (residues underlined were obtained with model M2a; see Materials and Methods). Groups of sequences were collapsed to simplify display; Old World monkey MHC-B/C have similarities to both hominoid MHC-B and -C. (C) HLA-B allotypes with V76. AF, allele frequency. Populations with HLA-B*73 AF≥0.8% are listed; for HLA-B*46, populations were selected to represent the range of AF. Rec., recombination with HLA-C. PM, point mutation. N/A, not available. (D) Distribution of HLA-B*46 AF in Southeast Asia. White dots represent sample points. Of 12 distinct V76-containing HLA-B (Figure 6C), 11 emerged in modern human populations, either by point substitution (N = 8) or recombination (N = 3). Exceptional is the highly divergent HLA-B73, which combines features of both MHC-C and chimpanzee and gorilla MHC-B [41]. Eight point mutations independently introduced V76 and the C1 epitope into a range of HLA-B allotypes having N80. In contrast, V76 is never present in HLA-B allotypes having either isoleucine or threonine 80 (33% of the total), a distribution unlikely to occur by chance (α = 0.05). Likewise all 11 chimpanzee MHC-B allotypes with V76 have N80 (Figure 6A). Thus selection has favored MHC-B variants having C1 (V76-N80) and eliminated variants having V76-I80 or V76-T80. A possible mechanism for the latter effect is that HLA-B allotypes having I80 and T80 carry the Bw4 epitope recognized by KIR3DL1 [42], [43], and that V76 perturbs this interaction while failing to introduce either C1 or C2.

HLA-B46, a potent KIR ligand, has undergone a selective sweep in Southeast Asia

Recombination events with HLA-C introduced V76 into three N80 HLA-B allotypes (Figure 6C). Of these HLA-B*46 rose to high frequency in Southeast Asia (Figure 6C), where it originated (Figure 6D) [44] following the arrival of modern humans ∼55–65,000 years ago [45]. During this selective sweep B*46 further diversified by point mutation to give 14 low-frequency subtypes (Figure 6C). The B*46 frequencies of 25.4% and 22.9% in the Yunnan Dai and Guizhou Miao, respectively, are the highest for any HLA-B allele in populations exceeding one million individuals, being of a magnitude typical for small, isolated or bottlenecked populations (Figure S4).

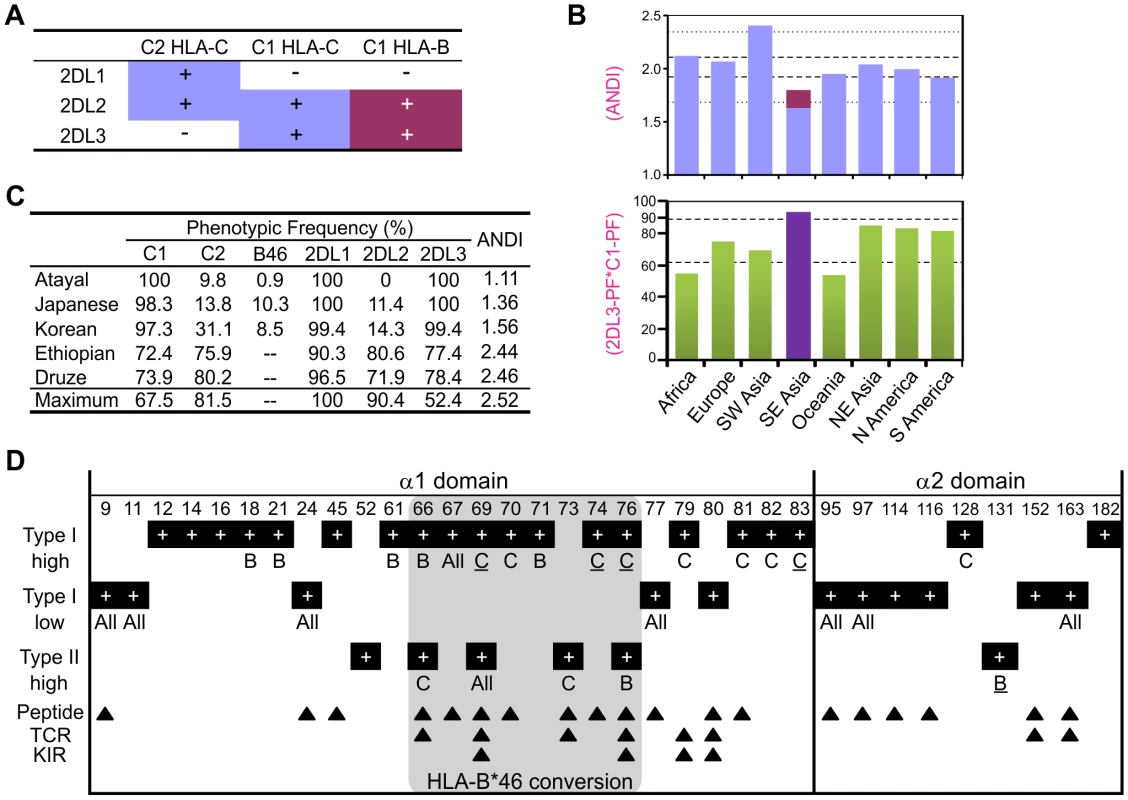

HLA-B*46 is a good ligand for KIR2DL2/3 [44], [46], [47] and a good educator of KIR2DL3-expressing NK cells [48]. It also gives individuals the flexibility to express up to four HLA class I isoforms bearing C1-C2 combinations (Figure 7A). From HLA and KIR frequencies, we determined the average number per individual of distinct interactions (ANDI) between KIR2DL receptors and HLA ligands. In all population groups ANDI ranged from 1.7–2.4, with a median of 2.0 (Figure 7B and Figure S5). Because of their low C2 and KIR2DL2 frequencies, Southeast Asians have the lowest ANDI worldwide, despite the significant contribution of B*46 (shown in red in Figure 7B and in Figure S5). When B*46 is excluded from the analysis, Southeast Asian ANDI values fall out of the normal range. Thus the rise of B*46 in these populations has compensated for their reduced frequency of functional ligand-receptor pairs (Figure 7C, Figure S5, and Figure S6).

Fig. 7. MHC-B allotypes that acquire lineage III KIR-binding increase NK cell effector capacity.

(A) Summary of the KIR2DL/HLA-B (magenta) and KIR2DL/HLA-C (blue) interactions. (B) Average number of distinct KIR2DL-HLA interactions (ANDI) (top) and 2DL3PF*C1PF quantity (bottom; PF, phenotype frequency) in eight human population groups (see Materials and Methods; individual populations are in Figure S5). Area between the gapped lines is the 25–75 percentile range; area between the dotted lines (top part) is the non-outlier range (Whisker plot with 1.5 coefficient). Colors in the top part are as defined in (A). Population group in purple (bottom part) contains populations with HLA-B*46 phenotype frequency of 8.7–27.5%. (C) KIR-HLA phenotypic frequencies for five individual populations. Maximum: maximum ANDI assuming Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. (D) Type I and type II functional divergence between MHC-B and -C α1–α2 domains. Positions characterized in this analysis are listed at the top of the panel, and black boxes indicate in which analysis these positions were characterized. ‘high’ refers to functional-divergence analyses while ‘low’ refers to an analysis to detect low functional divergence. MHC-B specific sites (indicated by a ‘B’) are defined as divergent in the MHC-B vs. MHC-C and MHC-B vs. Old World monkey-B/C comparisons but not in the MHC-C vs. Old World monkey-B/C comparison. The same approach was used for the MHC-C specific positions (indicated by a ‘C’). ‘All’, functionally-divergent in all pairwise comparisons. Underlined residues have better support (Figure S7). The gray box indicates residues that are in the recombinant region of HLA-B*46. Arrows indicate Peptide [73], TCR [74] and KIR [33], [34] contact sites. The evolution of MHC-B and -C was marked by extensive type I functional divergence (site-specific rate shift; α = 9.9E-22) as well as more limited type II functional divergence (shift of cluster-specific amino acid property; α = 0.048) (Figure S7A). Of eighteen locus-specific sites detected, sixteen are in the α1 domain, nine of them (including three of the four with strongest support) within residues 66–76 of the α1 helix (Figure 7D) [49], the segment recombined in forming B*46 [50]. Type I functional divergence was greater in MHC-C (nine positions, including the four with the strongest confidence) than MHC-B (five positions). The nine C-specific positions are fixed in MHC-C but variable in MHC-B and Old World monkey MHC-B/C. Thus during evolution of MHC-C to become the major ligand for lineage III KIR, functionally favorable residues were fixed at positions throughout the α1 helix (Figure 7D). Conversely, eleven positions exhibiting low type I divergence distribute evenly between the α1 and α2 domains, all but one being highly variable peptide-binding residues.

Type II functional divergence was more limited and equally distributed between MHC-B and -C (two positions each). Notably, however, this divergence included the valine to glutamate change at position 76 in the α1 domain of MHC-B (Figure 6B and Figure 7D). Overall, functional divergence of MHC-B and -C focused on the α1 helix, while maintaining similarity in the peptide-binding site. Consequently, the localized recombination that introduced residues 66–76 from HLA-C, conferred several C-like functions and selective advantage to the recombinant B*46 allotype [44], [51].

Discussion

Since their ancestors separated 6.5–10 million years ago, human and chimpanzee acquired major differences in KIR haplotype structure and gene content. These differences arose from specializations evolved on the human line. For chimpanzee KIR haplotypes, variable gene content is confined to the centromeric region, where ten KIR genes are variably found, leaving the telomeric region empty. During human evolution the telomeric region was ‘colonized’ to create a second region of gene content variability. As a consequence of this reorganization, symmetrical recombination between the centromeric and telomeric regions has evolved to be a major mechanism for diversifying KIR haplotypes in humans [26] but not in chimpanzees.

A second major human-specific specialization has been to fix mutations reducing the avidity of activating KIR for HLA class I, while retaining high-avidity inhibitory KIR. This process is most striking for the lineage III KIR that comprise receptors for MHC-C, the form of MHC class I molecule that became the major source of KIR ligands (the C1 and C2 epitopes) in the course of hominid evolution. Chimpanzees have eight lineage III KIR with no human equivalents, all of which encode high-avidity activating or inhibitory receptors for C1 or C2 [27], [28]. In contrast the six human lineage III KIR with no chimpanzee counterparts encode high-avidity inhibitory receptors for C1 and C2 and four activating receptors, which acquired mutations that caused three to lose avidity for HLA-C completely and one to have it reduced [29].

The major consequence of these two specializations is that humans evolved two distinctive KIR haplotype groups, A and B, that are under balancing selection, present in all populations, and differently associated with disease [17]. In contrast, chimpanzee KIR haplotypes are variations on a theme emphasizing multiple and variable high-avidity C1 and C2 receptors. The character of the A haplotypes is closer to that of the chimpanzee KIR haplotypes: they have genes encoding high-avidity inhibitory C1, C2 and Bw4 receptors and lack their attenuated activating counterparts. In contrast, B haplotypes carry genes for the attenuated activating receptors and distinctive variants of the inhibitory receptors. Disease associations suggest a basis for the balancing selection, in that A haplotypes favor successful anti-viral defense, whereas maternal B haplotypes favor successful reproduction [10]. Consistent with the evolutionary plasticity of viruses and other pathogens, the A haplotype KIR genes are more polymorphic than their B haplotype counterparts [52], as is also seen for chimpanzee KIR haplotypes. In this context, human-specific evolution of group B KIR haplotypes can be seen as an adaptation to life-threatening complications of pregnancy, such as pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, which have not affected the chimpanzee. For example, these hypertensive conditions could have arisen from imbalance between the supply and increased demands on maternal blood caused by selection to increase the size of the neonatal human brain, to double that of the chimpanzee [53].

A third human-specific specialization has been the decreasing use of MHC-B allotypes as ligands for lineage III KIR. C1 originated in a molecule resembling MHC-B, which with duplication and differentiation led to the modern MHC-B and -C [54]. Whereas 22% of chimpanzee MHC-B allotypes retain C1, only one rare HLA-B allotype, B*73, has retained C1 and the capacity to bind KIR2DL2/3 [46]. Thus the trend for much of human evolution has been for HLA-C to become the exclusive source of ligands for lineage III KIR, potentially reducing competition between NK-cell KIR and T-cell receptors, which have overlapping binding sites on HLA class I [33], [34]. In this scenario, HLA-C became more specialized in controlling NK cell functions leaving HLA-A and -B to dominate T cell responses. A remarkable reversal of this trend occurred in Southeast Asia during the last ∼55–65,000 years [45], where HLA-B*46, a recombinant allele that carries C1 and functions well as a ligand for KIR2DL2/3 [46], underwent a selective sweep to become the most frequent HLA-B allele. Resolution of human hepatitis C virus infection was associated with homozygosity for KIR2DL3 and its C1 ligand [55]. The potential benefit of HLA-B*46 is that it allows individuals to express three or four C1-bearing HLA-B and C allotypes. Thus the selective sweep of B*46 could have been driven by epidemic infection caused by a pathogen like the hepatitis C virus that is preferentially resisted by individuals having enhanced representation of C1 and its cognate inhibitory KIR. Interestingly, several reports describe B*46 as a risk factor for various current infectious diseases (Figure S8), illustrating the dynamic nature of these polymorphic genetic factors and the variable pressures placed on them by functions in both immune defense and reproduction.

Materials and Methods

Chimpanzee panel

A panel of 39 individuals was studied; 35 western chimpanzees, two eastern chimpanzees, one central chimpanzee, and one individual of unknown geographical origin. This study was approved by the Stanford University administrative panels on human subjects in medical research and laboratory animal care.

Chimpanzee KIR haplotypes

Haplotypes H13 and H2 originate from the RPCI-43 BAC library (individual: Donald) while H8 belongs to the CHORI-251 BAC library (individual: Clint). The final sequence of the H13 haplotype (clone RP43-84K19) has ‘finished sequencing’ quality (see Text S1 for details). H8 is a previously undescribed haplotype (Genbank accession number: AC155174) sequenced by the Washington University Genome Sequencing Center as part of the chimpanzee genome project. H2 was reported previously [24].

KIR nomenclature and lineages

KIR genes and alleles were named by the KIR Nomenclature Committee [56]. A curated database is available at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/kir/ [32].

KIR gene names reflect the structure of the molecules they encode: following ‘KIR’, the first two characters give the number of Ig-like domains in the molecule (KIR3D have three Ig-like domains for example), and the third character is either a ‘L’, ‘S’ or ‘P’ to indicate ‘Long’ (inhibitory) or ‘Short’ (activating) cytoplasmic tails, or a pseudogene, respectively. To simplify the text in this manuscript, the acronym KIR is sometimes omitted.

Based on phylogenetics, the Ig-like domains form three groups: D0 (most membrane distal of KIR3D), D1, and D2 (most membrane proximal). Based on domain structure and phylogenetic comparison, human KIR are seen to form four distinct lineages: KIR of the lineages III (3DL1-2) and V (3DL3) have three Ig-like domains, while KIR of the lineages I (2DL4-5) and III (2DL1-3, 2DS1-5) have two, with D0-D2 and D1-D2 configuration, respectively.

KIR expression study and MHC-specificity

Assessment of the expression and domain structure of the KIR encoded by genes present on the three chimpanzee KIR haplotypes sequenced was performed using peripheral blood mononuclear cells from the two individuals whose genomic DNA was used to construct the BAC libraries RPCI-43 and CHORI-251 (results are summarized in Figure S9; see for details). Data on the MHC specificity of chimpanzee lineage III KIR are from references [27] and [28]. Changes to the nomenclature of chimpanzee KIR sequences are described in Text S1 and in Figure S10.

KIR genomic analyses

Complete gene sequences were aligned and divided into 14 segments, as previously described [30]. Each segment was analyzed with four methods: Bayesian, maximum-likelihood, neighbor-joining and parsimony. For the lineage III KIR genes, a full gene analysis was performed on all fourteen segments. Additional details are in Text S1.

KIR content and haplotype structures in chimpanzee

For five of the 14 KIR (2DL4, 2DL5, 3DL1/2a and b, and 3DL5), KIR content was determined as previously described [23], and for the other nine KIR a new typing system was developed. KIR haplotype structures were predicted from genotype data using the HAPLO-IHP program [57], which was originally designed to reconstruct such haplotypes. Additional details are in Text S1.

KIR genotype diversity and linkage disequilibrium analysis in human and chimpanzee

To compare genotype diversity in human and chimpanzee, data from human populations from Africa [58], Europe [59], and Japan [60] were used. Because the chimpanzee panel has 26 unrelated individuals, human population data were resampled to give population sizes of n = 26. The mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence interval for the number of genotypes in human populations were obtained from 5,000 such resamplings. Mean and standard error for the pairwise difference between genotypes were estimated using a bootstrap approach, as implemented in MEGA4 [61]. Presence/absence of each of the 14 chimpanzee KIR of Figure 1B was considered a single-nucleotide polymorphism and the bootstrap procedure was used to shuffle the column content (10,000 bootstrap replicates) before pairwise comparisons were performed. Data from the chimpanzee panel were then compared to data obtained from human populations using the same approach [62].

For chimpanzee KIR, linkage disequilibrium (LD) was investigated from the haplotype data of Figure 1C using DNASP [63]; significance was assessed using a 2-tailed Fisher's exact test. For human and chimpanzee, we also investigated KIR haplotype structures using KIR2DL5 as a reference. In these analyses, gene linkage to 2DL5+/− was estimated for each KIR as a ratio: for example KIR3DS1 is seven times more common on 2DL5A+ haplotypes than on 2DL5A− haplotypes. All ratios were normalized to account for the difference in frequency between 2DL5+ and 2DL5− haplotypes. In the human locus, KIR2DS3/5 can occupy two different genomic locations [64], [65] and linkage between 2DL5 (A or B) and 2DS3/5 was assumed to be absolute, as supported by currently available haplotype sequences. Gene linkage to 2DL5 in human was assessed from Caucasian individuals [66].

Selection analysis

dN/dS (ω) ratios were estimated by maximum-likelihood using PAML4 [67]. Three sets of likelihood ratio tests were conducted to compare null models that do not allow ω>1 with models that do. Significance was assessed by comparing twice the difference in likelihood between the models (2ΔL) to a χ2 distribution with one or two degrees of freedom. Codons with ω>1 were identified using the Bayes Empirical Bayes approach; see Text S1 for details.

MHC-B and -C phylogenetic analysis

A representative set of MHC-B and -C sequences was gathered and phylogenetic analyses conducted using the approach described for the KIR genomic analysis (see Text S1). Ancestral sequence were reconstructed with CODEML of the PAML4 software package [67], using the marginal reconstruction approach (see Text S1 for details).

Frequency and distribution of MHC-B/C allotypes

Data for the distribution of the MHC-B and -C residues affecting interaction with lineage III KIR in hominoids were compiled using IMGT-HLA and IPD-MHC sequences [32], [68]. In addition, a gorilla MHC-B allotype bearing C1 was identified from analysis of the gorilla shotgun sequences available at the NCBI Trace Archive website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/home/), and generated by the Sanger Center as part of the gorilla genome project.

Allele frequencies for C1-bearing HLA-B allotypes are from the Allele Frequency Net Database [69]; when no population data were available, the country listed in the IMGT-HLA database [68] is given.

The B46 distribution map was generated using the GMT software package [70] and a previously developed script [71]; for this distribution, only anthropology studies were used, and data from recent migrant populations were discarded when the geographical location of the pre-migration population could not be precisely ascertained.

Divergence analysis

Type I (site-specific shift of evolutionary rate) and type II (site-specific shift of amino acid property) functional divergence analyses were performed with DIVERGE2 [72]. For the type I functional divergence analysis a likelihood ratio test was used to test the null hypothesis that the coefficient of functional divergence equals zero: twice the difference in likelihood was compared to a χ2 distribution with one degree of freedom. For the type II functional divergence analysis significance was assessed by a two-tailed Z-test. Functional divergence-related residues were identified through the use of cutoffs (see Figure S7 for additional details).

Average number of distinct interactions (ANDI)

Using KIR and HLA phenotypic frequencies (PF) in 33 human populations (see Figure S11 for details) we determined the average number of distinct interactions between HLA-C1/C2 and KIR2DL1-3 (sum of KIR and HLA receptor-ligand pairings) with the following formula: (2DL1PF*C2PF)+(2DL2PF*C2PF)+(2DL2PF*C1PF)+(2DL3PF*C1PF). For East Asian populations we also added the interaction between HLA-B*46 and KIR2DL2-3: (2DL2PF*B46PF)+(2DL3PF*B46PF). An alternative model where the interaction between KIR2DL2 and HLA-C2 was not taken into account was also considered but the results were similar (see Figure S12).

Statistical testing

In addition to the statistical tests described in individual sections, a binomial distribution was used to assess the probability that the substitutions that recurrently created V76 in HLA-B allotypes always occurred on allotypes with N80 by chance, and the Pearson product-moment was used to study the correlation between KIR and HLA frequencies in human populations.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. LanierLL

2008 Evolutionary struggles between NK cells and viruses. Nat Rev Immunol 8 259 268

2. DiefenbachA

RauletDH

2002 The innate immune response to tumors and its role in the induction of T-cell immunity. Immunol Rev 188 9 21

3. MorettaL

FerlazzoG

BottinoC

VitaleM

PendeD

2006 Effector and regulatory events during natural killer-dendritic cell interactions. Immunol Rev 214 219 228

4. VivierE

TomaselloE

BaratinM

WalzerT

UgoliniS

2008 Functions of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol 9 503 510

5. Moffett-KingA

2002 Natural killer cells and pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol 2 656 663

6. LanierLL

2008 Up on the tightrope: natural killer cell activation and inhibition. Nat Immunol 9 495 502

7. ShumBP

FlodinLR

MuirDG

RajalingamR

KhakooSI

2002 Conservation and variation in human and common chimpanzee CD94 and NKG2 genes. J Immunol 168 240 252

8. VilchesC

ParhamP

2002 KIR: Diverse, Rapidly Evolving Receptors of Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 20 217 251

9. KulkarniS

MartinMP

CarringtonM

2008 The Yin and Yang of HLA and KIR in human disease. Semin Immunol 20 343 352

10. ParhamP

2005 MHC class I molecules and KIRs in human history, health and survival. Nat Rev Immunol 5 201 214

11. RajagopalanS

LongEO

2005 Understanding how combinations of HLA and KIR genes influence disease. J Exp Med 201 1025 1029

12. BashirovaAA

MartinMP

McVicarDW

CarringtonM

2006 The killer immunoglobulin-like receptor gene cluster: tuning the genome for defense. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 7 277 300

13. AverdamA

PetersenB

RosnerC

NeffJ

RoosC

2009 A novel system of polymorphic and diverse NK cell receptors in primates. PLoS Genet 5 e1000688 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000688

14. WelchAY

KasaharaM

SpainLM

2003 Identification of the mouse killer immunoglobulin-like receptor-like (Kirl) gene family mapping to chromosome X. Immunogenetics 54 782 790

15. BartenR

TorkarM

HaudeA

TrowsdaleJ

WilsonMJ

2001 Divergent and convergent evolution of NK-cell receptors. Trends Immunol 22 52 57

16. GuethleinLA

Abi-RachedL

HammondJA

ParhamP

2007 The expanded cattle KIR genes are orthologous to the conserved single-copy KIR3DX1 gene of primates. Immunogenetics 59 517 522

17. GendzekhadzeK

NormanPJ

Abi-RachedL

GraefT

MoestaAK

2009 Co-evolution of KIR2DL3 with HLA-C in a human population retaining minimal essential diversity of KIR and HLA class I ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 18692 18697

18. BettauerRH

2010 Chimpanzees in hepatitis C virus research: 1998-2007. J Med Primatol 39 9 23

19. OlsonMV

VarkiA

2003 Sequencing the chimpanzee genome: insights into human evolution and disease. Nat Rev Genet 4 20 28

20. AppsR

MurphySP

FernandoR

GardnerL

AhadT

2009 Human leucocyte antigen (HLA) expression of primary trophoblast cells and placental cell lines, determined using single antigen beads to characterize allotype specificities of anti-HLA antibodies. Immunology 127 26 39

21. TrowsdaleJ

MoffettA

2008 NK receptor interactions with MHC class I molecules in pregnancy. Semin Immunol 20 317 320

22. AdamsEJ

CooperS

ThomsonG

ParhamP

2000 Common chimpanzees have greater diversity than humans at two of the three highly polymorphic MHC class I genes. Immunogenetics 51 410 424

23. KhakooSI

RajalingamR

ShumBP

WeidenbachK

FlodinL

2000 Rapid evolution of NK cell receptor systems demonstrated by comparison of chimpanzees and humans. Immunity 12 687 698

24. SambrookJG

BashirovaA

PalmerS

SimsS

TrowsdaleJ

2005 Single haplotype analysis demonstrates rapid evolution of the killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) loci in primates. Genome Res 15 25 35

25. WilsonMJ

TorkarM

HaudeA

MilneS

JonesT

2000 Plasticity in the organization and sequences of human KIR/ILT gene families. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 4778 4783

26. YawataM

YawataN

Abi-RachedL

ParhamP

2002 Variation within the human killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) gene family. Crit Rev Immunol 22 463 482

27. MoestaAK

Abi-RachedL

NormanPJ

ParhamP

2009 Chimpanzees use more varied receptors and ligands than humans for inhibitory killer cell Ig-like receptor recognition of the MHC-C1 and MHC-C2 epitopes. J Immunol 182 3628 3637

28. MoestaAK

GraefT

Abi-RachedL

Older AguilarAM

GuetheinLA

2010 Humans differ from other hominids in lacking an activating NK cell receptor that recognizes the C1 epitope of MHC class I. J Immunol 185 4233 4237

29. BiassoniR

2009 Human natural killer receptors, co-receptors, and their ligands. Curr Protoc Immunol Chapter 14 Unit 14 10

30. GuethleinLA

Older AguilarAM

Abi-RachedL

ParhamP

2007 Evolution of killer cell Ig-like receptor (KIR) genes: definition of an orangutan KIR haplotype reveals expansion of lineage III KIR associated with the emergence of MHC-C. J Immunol 179 491 504

31. Abi-RachedL

ParhamP

2005 Natural selection drives recurrent formation of activating killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor and Ly49 from inhibitory homologues. J Exp Med 201 1319 1332

32. RobinsonJ

WallerMJ

StoehrP

MarshSG

2005 IPD—the Immuno Polymorphism Database. Nucleic Acids Res 33 D523 526

33. FanQR

LongEO

WileyDC

2001 Crystal structure of the human natural killer cell inhibitory receptor KIR2DL1-HLA-Cw4 complex. Nat Immunol 2 452 460

34. BoyingtonJC

MotykaSA

SchuckP

BrooksAG

SunPD

2000 Crystal structure of an NK cell immunoglobulin-like receptor in complex with its class I MHC ligand. Nature 405 537 543

35. DavisDM

ChiuI

FassettM

CohenGB

MandelboimO

1999 The human natural killer cell immune synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 15062 15067

36. YusaS

CampbellKS

2003 Src homology region 2-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2 (SHP-2) can play a direct role in the inhibitory function of killer cell Ig-like receptors in human NK cells. J Immunol 170 4539 4547

37. SweeneyMC

WavreilleAS

ParkJ

ButcharJP

TridandapaniS

2005 Decoding protein-protein interactions through combinatorial chemistry: sequence specificity of SHP-1, SHP-2, and SHIP SH2 domains. Biochemistry 44 14932 14947

38. Alvarez-AriasDA

CampbellKS

2007 Protein kinase C regulates expression and function of inhibitory killer cell Ig-like receptors in NK cells. J Immunol 179 5281 5290

39. FujiiK

ZhuG

LiuY

HallamJ

ChenL

2004 Kinase peptide specificity: improved determination and relevance to protein phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 13744 13749

40. NishikawaK

TokerA

JohannesFJ

SongyangZ

CantleyLC

1997 Determination of the specific substrate sequence motifs of protein kinase C isozymes. J Biol Chem 272 952 960

41. ParhamP

ArnettKL

AdamsEJ

BarberLD

DomenaJD

1994 The HLA-B73 antigen has a most unusual structure that defines a second lineage of HLA-B alleles. Tissue Antigens 43 302 313

42. CellaM

LongoA

FerraraGB

StromingerJL

ColonnaM

1994 NK3-specific natural killer cells are selectively inhibited by Bw4-positive HLA alleles with isoleucine 80. J Exp Med 180 1235 1242

43. GumperzJE

LitwinV

PhillipsJH

LanierLL

ParhamP

1995 The Bw4 public epitope of HLA-B molecules confers reactivity with natural killer cell clones that express NKB1, a putative HLA receptor. J Exp Med 181 1133 1144

44. BarberLD

PercivalL

ValianteNM

ChenL

LeeC

1996 The inter-locus recombinant HLA-B*4601 has high selectivity in peptide binding and functions characteristic of HLA-C. J Exp Med 184 735 740

45. MellarsP

2006 Going east: new genetic and archaeological perspectives on the modern human colonization of Eurasia. Science 313 796 800

46. MoestaAK

NormanPJ

YawataM

YawataN

GleimerM

2008 Synergistic polymorphism at two positions distal to the ligand-binding site makes KIR2DL2 a stronger receptor for HLA-C than KIR2DL3. J Immunol 180 3969 3979

47. BiassoniR

FalcoM

CambiaggiA

CostaP

VerdianiS

1995 Amino acid substitutions can influence the natural killer (NK)-mediated recognition of HLA-C molecules. Role of serine-77 and lysine-80 in the target cell protection from lysis mediated by “group 2” or “group 1” NK clones. J Exp Med 182 605 609

48. YawataM

YawataN

DraghiM

PartheniouF

LittleAM

2008 MHC class I-specific inhibitory receptors and their ligands structure diverse human NK-cell repertoires toward a balance of missing self-response. Blood 112 2369 2380

49. ZemmourJ

ParhamP

1992 Distinctive polymorphism at the HLA-C locus: implications for the expression of HLA-C. J Exp Med 176 937 950

50. ParhamP

LawlorDA

LomenCE

EnnisPD

1989 Diversity and diversification of HLA-A,B,C alleles. J Immunol 142 3937 3950

51. SibilioL

MartayanA

SetiniA

Lo MonacoE

TremanteE

2008 A single bottleneck in HLA-C assembly. J Biol Chem 283 1267 1274

52. ShillingHG

GuethleinLA

ChengNW

GardinerCM

RodriguezR

2002 Allelic polymorphism synergizes with variable gene content to individualize human KIR genotype. J Immunol 168 2307 2315

53. DeSilvaJM

LesnikJJ

2008 Brain size at birth throughout human evolution: a new method for estimating neonatal brain size in hominins. J Hum Evol 55 1064 1074

54. Fukami-KobayashiK

ShiinaT

AnzaiT

SanoK

YamazakiM

2005 Genomic evolution of MHC class I region in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 9230 9234

55. KhakooSI

ThioCL

MartinMP

BrooksCR

GaoX

2004 HLA and NK cell inhibitory receptor genes in resolving hepatitis C virus infection. Science 305 872 874

56. MarshSG

ParhamP

DupontB

GeraghtyDE

TrowsdaleJ

2003 Killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) nomenclature report, 2002. Immunogenetics 55 220 226

57. YooYJ

TangJ

KaslowRA

ZhangK

2007 Haplotype inference for present-absent genotype data using previously identified haplotypes and haplotype patterns. Bioinformatics 23 2399 2406

58. NormanPJ

CarringtonCV

ByngM

MaxwellLD

CurranMD

2002 Natural killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) locus profiles in African and South Asian populations. Genes Immun 3 86 95

59. UhrbergM

ParhamP

WernetP

2002 Definition of gene content for nine common group B haplotypes of the Caucasoid population: KIR haplotypes contain between seven and eleven KIR genes. Immunogenetics 54 221 229

60. YawataM

YawataN

McQueenKL

ChengNW

GuethleinLA

2002 Predominance of group A KIR haplotypes in Japanese associated with diverse NK cell repertoires of KIR expression. Immunogenetics 54 543 550

61. KumarS

TamuraK

NeiM

2004 MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform 5 150 163

62. GendzekhadzeK

NormanPJ

Abi-RachedL

LayrisseZ

ParhamP

2006 High KIR diversity in Amerindians is maintained using few gene-content haplotypes. Immunogenetics 58 474 480

63. LibradoP

RozasJ

2009 DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25 1451 1452

64. DuZ

SharmaSK

SpellmanS

ReedEF

RajalingamR

2008 KIR2DL5 alleles mark certain combination of activating KIR genes. Genes Immun 9 470 480

65. OrdonezD

MeenaghA

Gomez-LozanoN

CastanoJ

MiddletonD

2008 Duplication, mutation and recombination of the human orphan gene KIR2DS3 contribute to the diversity of KIR haplotypes. Genes Immun 9 431 437

66. NormanPJ

CookMA

CareyBS

CarringtonCV

VerityDH

2004 SNP haplotypes and allele frequencies show evidence for disruptive and balancing selection in the human leukocyte receptor complex. Immunogenetics 56 225 237

67. YangZ

1997 PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci 13 555 556

68. RobinsonJ

WallerMJ

ParhamP

de GrootN

BontropR

2003 IMGT/HLA and IMGT/MHC: sequence databases for the study of the major histocompatibility complex. Nucleic Acids Res 31 311 314

69. MiddletonD

MenchacaL

RoodH

KomerofskyR

2003 61 403 407 New allele frequency database: http://www.allelefrequencies.net. Tissue Antigens

70. WesselP

SmithWHF

1998 New, improved version of generic mapping tools released. Eos, Transactions, American Geophysical Union 79 579

71. SolbergOD

MackSJ

LancasterAK

SingleRM

TsaiY

2008 Balancing selection and heterogeneity across the classical human leukocyte antigen loci: a meta-analytic review of 497 population studies. Hum Immunol 69 443 464

72. GuX

Vander VeldenK

2002 DIVERGE: phylogeny-based analysis for functional-structural divergence of a protein family. Bioinformatics 18 500 501

73. ChelvanayagamG

1996 A roadmap for HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C peptide binding specificities. Immunogenetics 45 15 26

74. MarrackP

Scott-BrowneJP

DaiS

GapinL

KapplerJW

2008 Evolutionarily conserved amino acids that control TCR-MHC interaction. Annu Rev Immunol 26 171 203

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2010 Číslo 11- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Genome-Wide Association Meta-Analysis of Cortical Bone Mineral Density Unravels Allelic Heterogeneity at the Locus and Potential Pleiotropic Effects on Bone

- Beyond QTL Cloning

- An Evolutionary Framework for Association Testing in Resequencing Studies

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Two Novel Regions at 11p15.5-p13 and 1p31 with Major Impact on Acute-Phase Serum Amyloid A

- The Functional Interplay between Protein Kinase CK2 and CCA1 Transcriptional Activity Is Essential for Clock Temperature Compensation in Arabidopsis

- Endogenous Viral Elements in Animal Genomes

- Analysis of the 10q11 Cancer Risk Locus Implicates and in Human Prostate Tumorigenesis

- DNA Methylation and Normal Chromosome Behavior in Neurospora Depend on Five Components of a Histone Methyltransferase Complex, DCDC

- Sarcomere Formation Occurs by the Assembly of Multiple Latent Protein Complexes

- Genetic Basis of Growth Adaptation of after Deletion of , a Major Metabolic Gene

- Nomadic Enhancers: Tissue-Specific -Regulatory Elements of Have Divergent Genomic Positions among Species

- The Parental Non-Equivalence of Imprinting Control Regions during Mammalian Development and Evolution

- CTCF-Dependent Chromatin Bias Constitutes Transient Epigenetic Memory of the Mother at the Imprinting Control Region in Prospermatogonia

- Systematic Dissection and Trajectory-Scanning Mutagenesis of the Molecular Interface That Ensures Specificity of Two-Component Signaling Pathways

- Nucleolin Is Required for DNA Methylation State and the Expression of rRNA Gene Variants in

- The Complex Genetic Architecture of the Metabolome

- ATM Limits Incorrect End Utilization during Non-Homologous End Joining of Multiple Chromosome Breaks

- Mutation Disrupts Synaptonemal Complex Formation, Recombination, and Chromosome Segregation in Mammalian Meiosis

- Mismatch Repair–Independent Increase in Spontaneous Mutagenesis in Yeast Lacking Non-Essential Subunits of DNA Polymerase ε

- The Kinesin-3 Motor UNC-104/KIF1A Is Degraded upon Loss of Specific Binding to Cargo

- Epigenetic Silencing of Spermatocyte-Specific and Neuronal Genes by SUMO Modification of the Transcription Factor Sp3

- A Coastal Cline in Sodium Accumulation in Is Driven by Natural Variation of the Sodium Transporter AtHKT1;1

- Cyclin B3 Is Required for Multiple Mitotic Processes Including Alleviation of a Spindle Checkpoint–Dependent Block in Anaphase Chromosome Segregation

- Altered DNA Methylation in Leukocytes with Trisomy 21

- Human-Specific Evolution and Adaptation Led to Major Qualitative Differences in the Variable Receptors of Human and Chimpanzee Natural Killer Cells

- Leptotene/Zygotene Chromosome Movement Via the SUN/KASH Protein Bridge in

- RACK-1 Acts with Rac GTPase Signaling and UNC-115/abLIM in Axon Pathfinding and Cell Migration

- Genome-Wide Effects of Long-Term Divergent Selection

- Endless Forms Most Viral

- Conflict between Noise and Plasticity in Yeast

- Essential Functions of the Histone Demethylase Lid

- The Transcriptional Regulator Rok Binds A+T-Rich DNA and Is Involved in Repression of a Mobile Genetic Element in

- The Cellular Robustness by Genetic Redundancy in Budding Yeast

- Localization of a Guanylyl Cyclase to Chemosensory Cilia Requires the Novel Ciliary MYND Domain Protein DAF-25

- A Buoyancy-Based Screen of Drosophila Larvae for Fat-Storage Mutants Reveals a Role for in Coupling Fat Storage to Nutrient Availability

- A Functional Genomics Approach Identifies Candidate Effectors from the Aphid Species (Green Peach Aphid)

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Two Novel Regions at 11p15.5-p13 and 1p31 with Major Impact on Acute-Phase Serum Amyloid A

- Analysis of the 10q11 Cancer Risk Locus Implicates and in Human Prostate Tumorigenesis

- The Parental Non-Equivalence of Imprinting Control Regions during Mammalian Development and Evolution

- Genome-Wide Effects of Long-Term Divergent Selection

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy