-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Localization of a Guanylyl Cyclase to Chemosensory Cilia Requires the Novel Ciliary MYND Domain Protein DAF-25

In harsh conditions, Caenorhabditis elegans arrests development to enter a non-aging, resistant diapause state called the dauer larva. Olfactory sensation modulates the TGF-β and insulin signaling pathways to control this developmental decision. Four mutant alleles of daf-25 (abnormal DAuer Formation) were isolated from screens for mutants exhibiting constitutive dauer formation and found to be defective in olfaction. The daf-25 dauer phenotype is suppressed by daf-10/IFT122 mutations (which disrupt ciliogenesis), but not by daf-6/PTCHD3 mutations (which prevent environmental exposure of sensory cilia), implying that DAF-25 functions in the cilia themselves. daf-25 encodes the C. elegans ortholog of mammalian Ankmy2, a MYND domain protein of unknown function. Disruption of DAF-25, which localizes to sensory cilia, produces no apparent cilia structure anomalies, as determined by light and electron microscopy. Hinting at its potential function, the dauer phenotype, epistatic order, and expression profile of daf-25 are similar to daf-11, which encodes a cilium-localized guanylyl cyclase. Indeed, we demonstrate that DAF-25 is required for proper DAF-11 ciliary localization. Furthermore, the functional interaction is evolutionarily conserved, as mouse Ankmy2 interacts with guanylyl cyclase GC1 from ciliary photoreceptors. The interaction may be specific because daf-25 mutants have normally-localized OSM-9/TRPV4, TAX-4/CNGA1, CHE-2/IFT80, CHE-11/IFT140, CHE-13/IFT57, BBS-8, OSM-5/IFT88, and XBX-1/D2LIC in the cilia. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) (required to build cilia) is not defective in daf-25 mutants, although the ciliary localization of DAF-25 itself is influenced in che-11 mutants, which are defective in retrograde IFT. In summary, we have discovered a novel ciliary protein that plays an important role in cGMP signaling by localizing a guanylyl cyclase to the sensory organelle.

Published in the journal: Localization of a Guanylyl Cyclase to Chemosensory Cilia Requires the Novel Ciliary MYND Domain Protein DAF-25. PLoS Genet 6(11): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001199

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001199Summary

In harsh conditions, Caenorhabditis elegans arrests development to enter a non-aging, resistant diapause state called the dauer larva. Olfactory sensation modulates the TGF-β and insulin signaling pathways to control this developmental decision. Four mutant alleles of daf-25 (abnormal DAuer Formation) were isolated from screens for mutants exhibiting constitutive dauer formation and found to be defective in olfaction. The daf-25 dauer phenotype is suppressed by daf-10/IFT122 mutations (which disrupt ciliogenesis), but not by daf-6/PTCHD3 mutations (which prevent environmental exposure of sensory cilia), implying that DAF-25 functions in the cilia themselves. daf-25 encodes the C. elegans ortholog of mammalian Ankmy2, a MYND domain protein of unknown function. Disruption of DAF-25, which localizes to sensory cilia, produces no apparent cilia structure anomalies, as determined by light and electron microscopy. Hinting at its potential function, the dauer phenotype, epistatic order, and expression profile of daf-25 are similar to daf-11, which encodes a cilium-localized guanylyl cyclase. Indeed, we demonstrate that DAF-25 is required for proper DAF-11 ciliary localization. Furthermore, the functional interaction is evolutionarily conserved, as mouse Ankmy2 interacts with guanylyl cyclase GC1 from ciliary photoreceptors. The interaction may be specific because daf-25 mutants have normally-localized OSM-9/TRPV4, TAX-4/CNGA1, CHE-2/IFT80, CHE-11/IFT140, CHE-13/IFT57, BBS-8, OSM-5/IFT88, and XBX-1/D2LIC in the cilia. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) (required to build cilia) is not defective in daf-25 mutants, although the ciliary localization of DAF-25 itself is influenced in che-11 mutants, which are defective in retrograde IFT. In summary, we have discovered a novel ciliary protein that plays an important role in cGMP signaling by localizing a guanylyl cyclase to the sensory organelle.

Introduction

The dauer larva of Caenorhabditis elegans is an alternate third larval stage where a stress resistant, non-aging life plan is adopted in harsh environmental conditions [1]. Dauer larvae disperse and will resume development when conditions improve. The study of dauer formation has elucidated a complex gene network used to control the decision to go into diapause [2]. The dauer pathway includes well-recognized members in the canonical TGF-β (Transforming Growth Factor-Beta) and Insulin/Insulin-like signaling (IIS) pathways, as well as proteins affecting olfactory reception, neuron depolarization and peptide hormone secretion. Many mutants isolated as dauer formation defective (Daf-d) or constitutive (Daf-c) have revealed the key signaling components [2]. Here we identify DAF-25, a novel member of the olfactory signaling pathway that is associated with cGMP signaling—a signal transduction pathway with established links to cilia [3]. We show that the mammalian ortholog, Ankmy2, is expressed in ciliary photoreceptors and interacts with a guanylate cyclase (GC1), as predicted from the C. elegans results.

The olfactory signaling cascade has been well characterized in the two C. elegans amphids, organs consisting of a set of twelve bilaterally symmetric pairs of ciliated sensory neurons [4], [5]. While similar to mammalian olfactory signaling, at least some proteins involved are also homologous to those implicated in mammalian phototransduction [6]. Chemicals are sensed at the afferent, ciliated ends of sensory neurons where they contact the environment through pores in the cuticle. The cilia are required for chemosensation of chemical attractants and repellants, as well as for dauer entry and exit [7]. For many odorants the specific neurons that detect the odor are known [4]. For example, the AWA, AWB and AWC neuron pairs sense volatile odorants such as pyrazine, benzaldehyde, trimethyl thiazole and isoamyl alcohol. The ASH pair of ciliated olfactory neurons can detect changes in osmotic pressure.

The connection between dauer formation, chemosensory behavior and cilia is well known [2], [8]. C. elegans hermaphrodites only possess non-motile (primary) cilia which are found at the dendritic ends of 60 sensory neurons in the head and tail [5], [8]. Intraflagellar transport (IFT) proteins, normally required for building cilia, are well conserved in C. elegans and several have been discovered in this organism through the identification of sensory mutants [9]. Indeed, dauer formation is a sensory behavior dependent on the balanced inputs of dauer pheromone, temperature and food signals [4].

Proteins in the olfactory component of the dauer pathway include SRBC-64 and SRBC-66 (dauer pheromone receptors), DAF-11, a guanylyl cyclase, G-proteins (gpa-2 and gpa-3), the Hsp90 molecular chaperone DAF-21, the IFT protein DAF-10, and the DAF-19 RFX-type transcription factor [10]–[14]. DAF-19 is strictly required for cilium formation as it regulates the expression of many cilia-related genes through a consensus sequence dubbed ‘x-box’ [15]. daf-11, daf-19 and daf-21 are Daf-c, whereas daf-6 and daf-10 are Daf-d [16]. daf-19, daf-6 and daf-10 are all dye-filling defective, indicating that their cilia (if present) are not exposed to the environment [17], [10]. By contrast, daf-11 and daf-21 mutants show wild-type dye filling [18]. All five mentioned daf genes are defective in recovery from the dauer diapause, presumably because they cannot detect the bacterial food stimulus [17]. Dauer recovery defects are present for mutants with broad chemosensory defects caused by abnormal ciliogenesis or signaling, and for many Unc genes, such as unc-31, which encodes a dense core vesicle secretion protein [17], [19], [20]. Our genetic screen for C. elegans Daf mutants has uncovered a novel ciliary protein, DAF-25, which participates in cGMP-associated signaling by modulating the ciliary localization of a guanylyl cyclase, DAF-11. The mammalian ortholog of DAF-25, Ankmy2, interacts with ciliary photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase 1 (GC1), indicating that the role of the MYND domain protein in cilia function is likely to be conserved and potentially relevant to human retinal disease or other ciliopathies.

Results

Genetic Epistasis Analysis Places DAF-25 Function in the Amphid Cilia

To identify genes potentially implicated in sensory transduction, we uncovered four alleles of daf-25 in various screens for new mutants exhibiting a temperature-sensitive Daf-c phenotype. Three alleles (m98, m137, and m362) were isolated from ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) mutagenesis screens and the fourth, m488, was isolated in a screen for Daf-c mutants with transposon insertions [21], [22].

Epistasis tests with the Daf-d mutants daf-12, daf-16, daf-3, daf-6 and daf-10 were used to position daf-25 into the existing genetic pathway. Mutations in the daf-12 nuclear hormone receptor gene suppress most Daf-c mutants [16], [23] including daf-25 (0% dauer larva formation, n>200 for daf-25(m362); daf-12(m20) compared to 97.5%, n = 281 for daf-25(m362) at 25°C). DAF-16/FOXO is the major downstream effector for Insulin/IGF1 signaling [24] as is DAF-3/Co-Smad for the TGF-β pathway [25]. Mutations in daf-16 and daf-3 only partially suppress the Daf-c phenotype of daf-25 (37.6% dauer larvae, n = 407 for daf-25(m362); daf-16(m26) and 60.0%, n = 167 for daf-25(m362); daf-3(mgDf90) at 25°C), indicating that DAF-25 likely functions upstream of both pathways.

Importantly, daf-10, which encodes an IFT protein (DAF-10/IFT122) required for ciliogenesis [11], suppresses daf-25 (0% dauer larvae, n>200 for daf-25(m362); daf-6(e1387) compared to 97.5%, n = 281 for daf-25(m362) at 25°C), suggesting a function for DAF-25 within sensory cilia. daf-6 mutants have closed amphid channels and cannot smell chemoattractants or form dauer larvae even though their cilia are present [5]. Interestingly, daf-6 mutations do not suppress the daf-25 Daf-c phenotype (97.4% dauer larvae, n = 312 for daf-25(m362); daf-6(e1377) at 25°C), indicating that DAF-25 acts downstream of DAF-6, and that environmental (ciliary) input is not required for the Daf-c phenotype. DAF-6/PTCHD3 is expressed in the glial (sheath) cell that forms the amphid sensory channel, allowing contact of the sensory cilia to the environment through pores in the cuticle [26]. 8-bromo-cGMP rescues the dauer phenotype of daf-25 (0% dauer larva formation for daf-25(m362) on 8-bromo-cGMP, n = 72 compared to 32% dauer larva formation on the control, n = 65, both at 20°C), similar to that previously reported for daf-11 [12] indicating that DAF-25 functions upstream of the cGMP pathway in the cilia. Indeed the Daf-c phenotype of daf-25(m362) is very similar to that of daf-11(m84) at all temperatures tested (Table S1). The epistasis results are also similar to those for daf-11, indicating that both genes function at the same point in the genetic pathway—upstream of cilia formation and cGMP signaling in the cilia, and downstream of environmental input.

daf-25 Mutants Exhibit Chemosensory Phenotypes Independent of Ciliary Ultrastructure Defects

daf-25 mutants are temperature-sensitive Daf-c and defective in dauer recovery. They constitutively form virtually 100% dauer larvae at 25°C, which do not recover upon transfer to 15°C. The Daf-c phenotype is rescued by maternally contributed daf-25 as seen in the progeny of daf-25(m362) heterozygous hermaphrodites which form zero percent dauer larvae at 25°C (n>200). Moreover, daf-25 animals exhibit defective responses to various chemosensory stimuli as well as a moderate defect in response to osmotic stress (37 of 45 daf-25(m362) adults crossed the sucrose hyperosmotic boundary compared to 1 of 45 for N2, χ2-p-value = <0.00001, while 0 of 30 daf-25(m362) and N2 adults crossed a glycerol boundary). Adults are also defective in egg laying. Despite the fact that Daf-c genes in the IIS pathway (like daf-2 and age-1) extend adult lifespan [27], daf-25 mutants show no significant difference in lifespan from N2 (Figure S1).

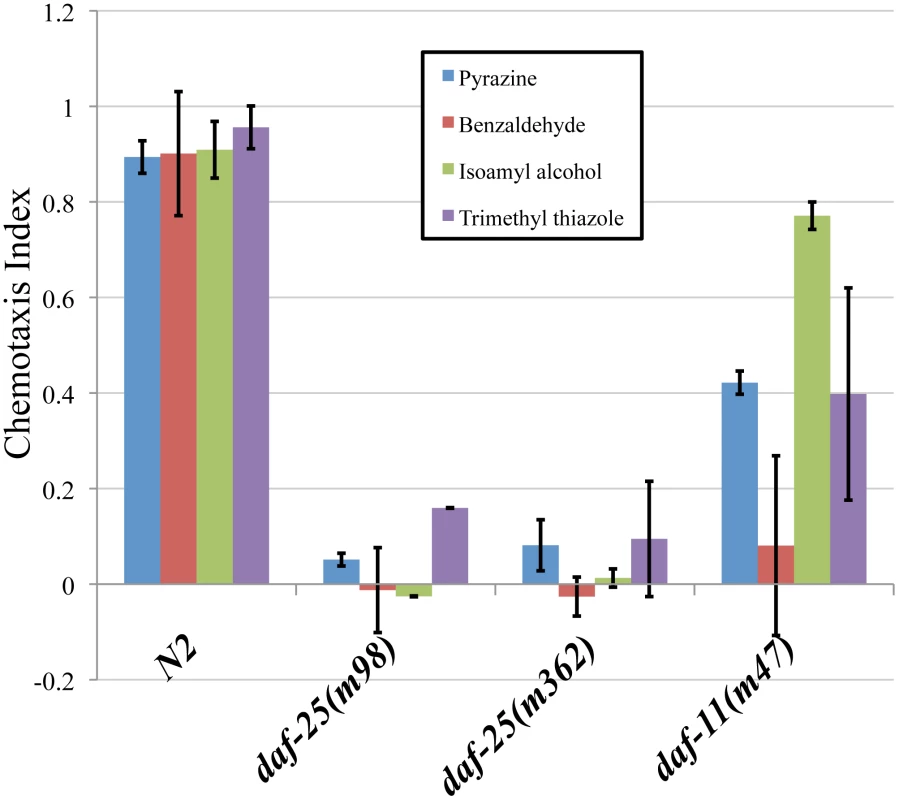

daf-25 mutants are defective in chemotaxis to at least four volatile odorants (Figure 1). Wild-type N2 adults were attracted to the compounds tested, the chemotaxis-defective mutant daf-11 was partially attracted, whereas the two daf-25 mutants tested were nearly unresponsive (Figure 1). DAF-11 and the cGMP pathway are known to regulate responses to the AWC neuron-mediated odors isoamyl alcohol, trimethyl thiazole and benzaldehyde, and our results indicate that DAF-25 is also required in this pathway [28]. The AWA-detected scent, pyrazine, is not reported to be detected by the cGMP pathway, suggesting that DAF-25 participates in another signaling pathway in AWA neurons. Interestingly, alhough it has been shown that the cGMP pathway does not participate in AWA-mediated olfaction, the particular tested allele daf-11(m47) was previously shown to have reduced affinity for pyrazine [28], as we have seen here.

Fig. 1. daf-25 mutants have chemosensory defects.

We assayed the ability of two daf-25 mutants to respond to four attractants. The daf-25 behavior was compared with N2 and with daf-11(m47), which is partially chemotaxis defective. Chemotaxis index scores were calculated as the number of adults at the attractant minus the number at the control, divided by the total number of adults [50]. Neither allele of daf-25 responded to any of the attractants, indicating an olfactory defect in daf-25 mutants that is more severe than that of the daf-11 guanylyl cyclase mutant. Benzaldehyde, trimethyl thiazole and isoamyl alcohol are detected by the AWC neurons, and pyrazine by the AWA neurons. Pyrazine: N2 n = 66, daf-25(m98) n = 78, daf-25(m362) n = 123, daf-11(m47) n = 83. Benzaldehyde: N2 n = 91, daf-25(m98) n = 80, daf-25(m362) n = 115, daf-11(m47) n = 62. Isoamyl alchohol: N2 n = 66, daf-25(m98) n = 78, daf-25(m362) n = 78, daf-11(m47) n = 83. Trimethyl thiazole: N2 n = 91, daf-25(m98) n = 69, daf-25(m362) n = 74, daf-11(m47) n = 93. To establish if the olfactory phenotypes are associated with ciliary defects, mixed-stage populations of daf-25 mutants and N2 were stained with the lipophillic dye, DiI. Mutants with cilia structure anomalies have abrogated dye filling of the olfactory neurons [29], whereas daf-25 mutants take up the dye normally at all ages, suggesting that they have structurally intact cilia (Figure S2). To confirm this possibility, we further examined the integrity of ciliary structures by transmission electron microscopy. Ciliary ultrastructures in two daf-25(m362) L2 larvae—including transition zones, middle segments consisting of doublet microtubules, and distal segments composed of singlet microtubules—was indistinguishable from the two N2 controls (Figure S3). We conclude that daf-25 animals have no obvious defects in ciliogenesis or cilia ultrastructure.

Molecular Identification of daf-25

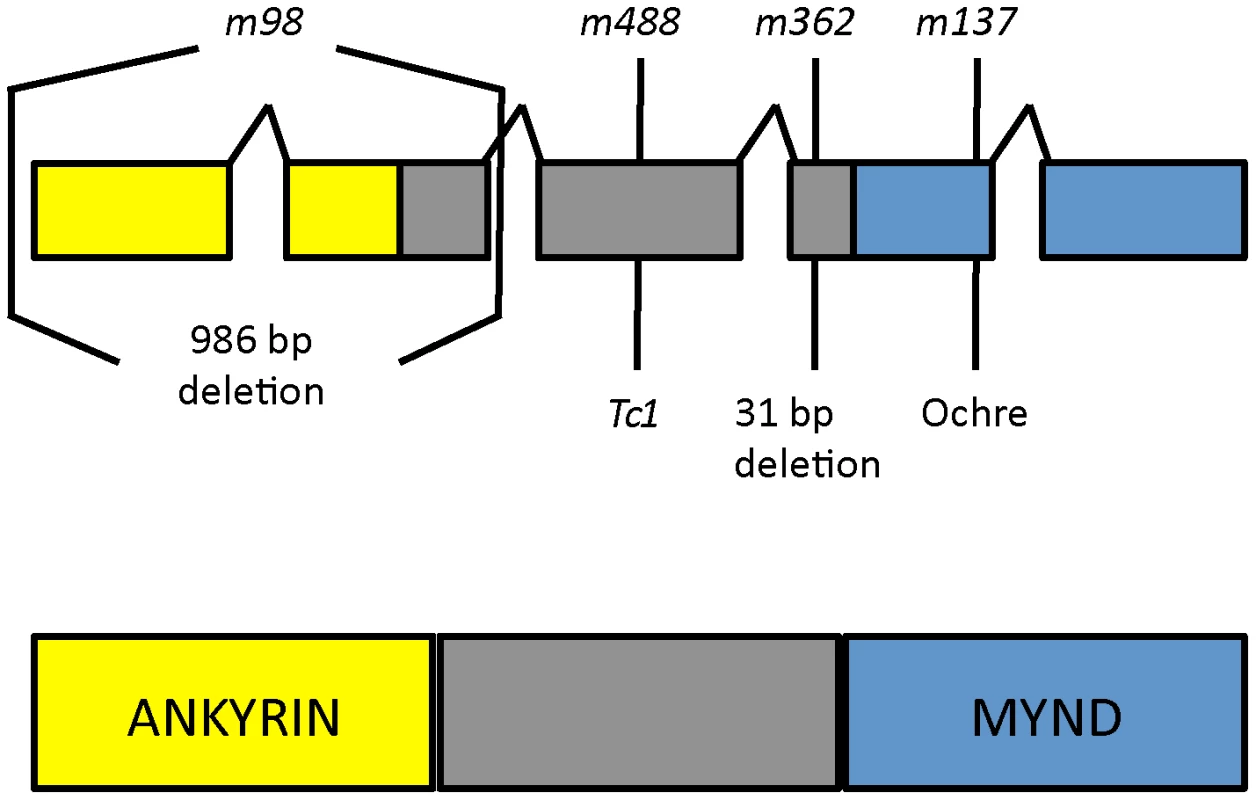

To identify the daf-25 genetic locus, we first used three-factor genetic crosses to map the m362 allele to the left arm of Chromosome I. Then, we employed a modified SNP mapping procedure [30], in which we selected for recombinants in the unc-11-daf-25 interval to map daf-25 to the left-most 1 Mbp of Chromosome I. Finally, we used a custom-made high-density array for the left-most ∼2.5 Mbp for comparative genomic hybridization (CGH). Two molecular lesions in daf-25(m362) were identified in exon 4 of Y48G1A.3 (Figure 2), including a 31 bp deletion and a G>A change 72 bp to the right of the deletion. Subsequent sequencing of PCR products from mutant genomic DNA uncovered the lesions in the remaining alleles. The m98 mutant has a 996 bp deletion that removes the first two exons, m137 has an ochre stop in the fourth exon, and m488 has a Tc1 transposon insertion in the third exon (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. daf-25 alleles encode the ortholog of mammalian Ankmy2.

We identified the daf-25 gene using three-factor genetic crosses and SNP mapping followed by ArrayCGH. The four alleles of daf-25 include two EMS-induced deletions m98 (996 bp deletion at I:332481-333477) and m362 (31 bp deletion at I:335814-335844 which results in a premature stop 14 codons downstream), a transposon (Tc1) insertion at I:330927 (m488) and an EMS-induced ochre nonsense mutation m137 (at I:336013). DAF-25 is well conserved and has been named Ankmy2 in mammals for its three ankyrin repeats and MYND-type zinc finger domain. Y48G1A.3 encodes the C. elegans ortholog of mammalian Ankmy2 (by reciprocal BLAST), a protein with three ankyrin repeats and a MYND-type zinc finger domain. The C. elegans protein shares throughout its length (388 residues) 52% similarity and 32% identity with mouse Ankmy2 (440 residues). The C. elegans ankyrin repeat domain is 40% identical and the MYND domain is 55% identical to the murine ortholog. Ankmy2 is very well conserved among chordates, with identity percentages compared to human Ankmy2 of 99% for macaque, 93% for cow, 88% for mouse, and 76% for zebrafish (Figure S4). Although the protein is highly conserved, there is no reported functional data for this gene from any organism. The MYND domain is thought to function in protein-protein interactions, although only a small number of MYND domain-containing proteins have been characterized, including the AML1/ETO protein, which binds SMRT/N-CoR through its MYND domain [31].

To analyze the transcript(s) generated by the daf-25 gene, we employed a PCR-based approach. Using primers for the SL1 transplice sequence or poly-T in combination with gene-specific primers, we were able to amplify only one isoform (Figure S5). This result is consistent with the RNA-Seq and trans-splice data found on Wormbase, which shows a daf-25 transcript sequence identical to that presented in Figure S5, including the 5′ and 3′ UTRs [32]–[34]. We were unable to amplify an SL2 trans-spliced product using multiple gene specific primers and an SL2 primer under any conditions tested.

DAF-25 Functions in Cilia

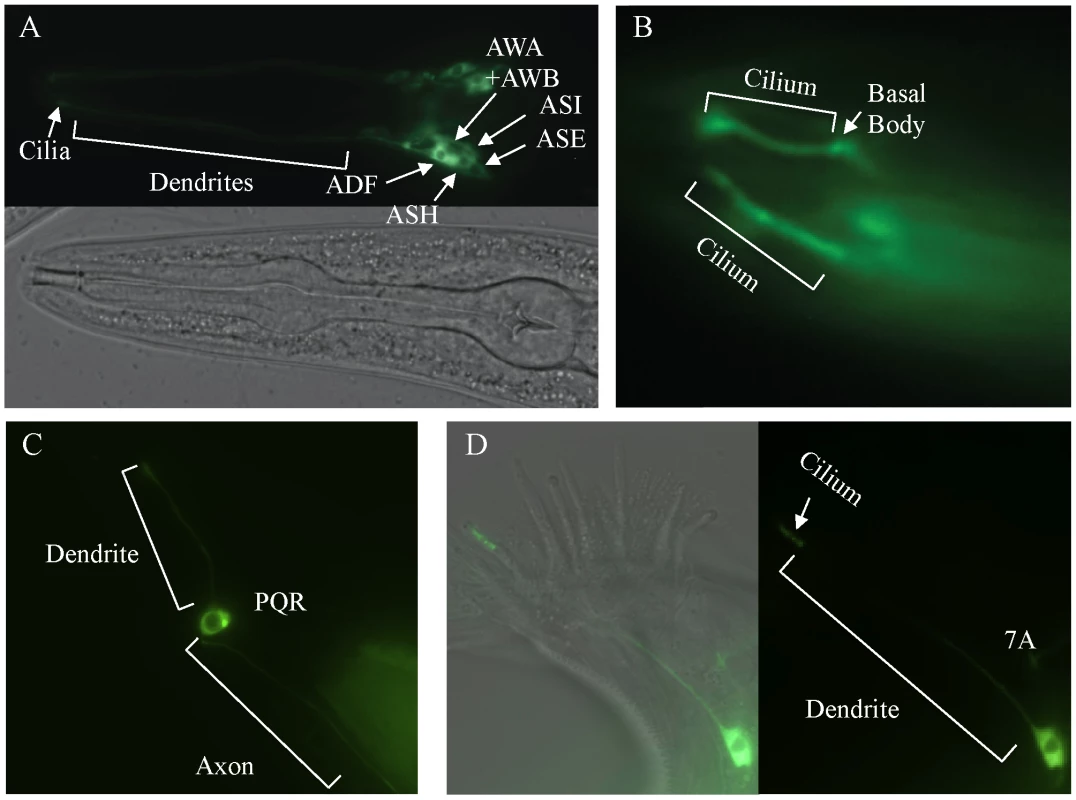

To determine the sub-cellular localization of DAF-25, a GFP-tagged protein was constructed. The daf-25 upstream promoter (approx. 2.0 kb 5′ of the ATG) was fused to the daf-25 cDNA in frame into the pPD95.77 vector (gift from Dr. Andrew Fire) containing GFP (without a nuclear localization signal) and the unc-54 3′UTR. This construct was found to be expressed in many ciliated sensory neurons, including the following pairs of anterior neurons: AFD, ASK, ASI, ASH, ASJ, ASG, ASE, ADF, AWA, AWB, AWC and IL2 (Figure 3). It is also expressed in the PQR ciliated neuron and one ventral interneuron. We also show expression of the DAF-25::GFP construct in the 7A ciliated neuron in the male tail though we did not fully examine male expression due to the limited number examined and the mosaic expression associated with extra-chromosomal arrays. Most importantly, the fluorescence of the GFP-tagged protein was localized to the cilia of all these cells. The GFP-fusion construct was judged to be functional because it fully rescued the Daf-c phenotype of daf-25(m362) at 25°C while non-transgenic siblings arrested as dauers (n>200).

Fig. 3. daf-25 is expressed in many ciliated cells and encodes a novel ciliary protein.

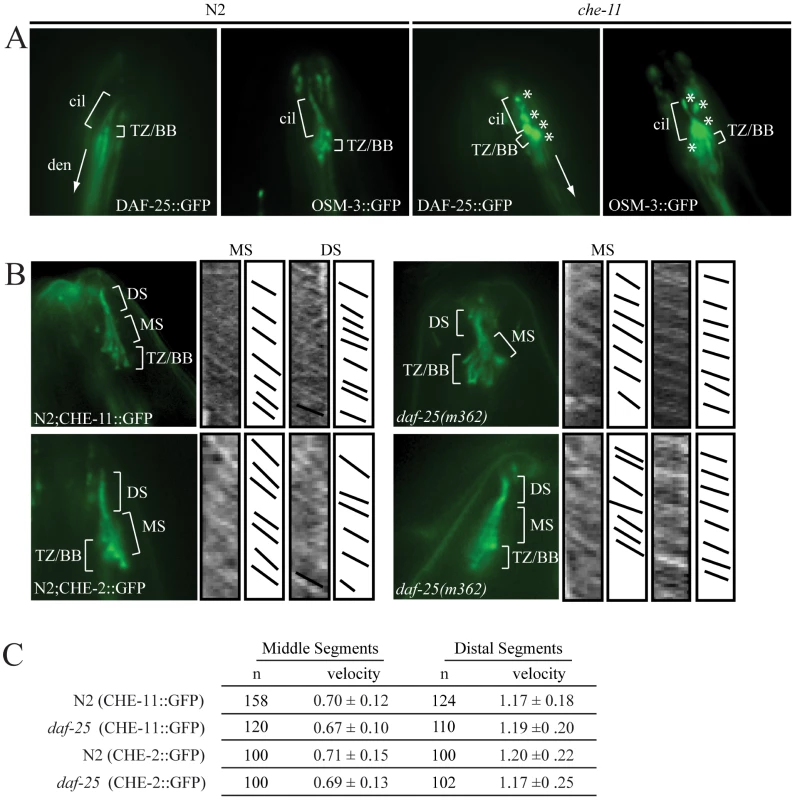

A reporter construct joined the 2.0 kb promoter region 5′ of the AUG for daf-25 to the daf-25 cDNA with the C-terminal GFP coding sequence. Expression is seen in many anterior chemosensory neurons in (A) including AFD, ASK, ASI, ASH, ASJ, ASG, ASE, ADF, AWA, AWB, AWC and IL2. There is a strong DAF-25::GFP signal localized in the sensory cilia (B). Expression of DAF-25::GFP is shown in the PQR neuron (C) and in the male tale neuron 7A (D). To investigate whether the ciliary localization of DAF-25 might depend on the intraflagellar transport (IFT) machinery, the DAF-25::GFP construct was crossed into che-11, which is required for retrograde transport in the cilia. In che-11 mutants, IFT-associated proteins accumulate in the cilia [35]. The DAF-25::GFP translational fusion protein accumulated within the cilia and basal body (base of cilia) despite a reduction in total GFP fluorescence (mean DAF-25::GFP fluorescence in che-11 (8.7E12) compared to N2 (1.4E13), p<0.00001, n = 9 for both), suggesting that the protein is associated with IFT (Figure 4). To test for a possible role for DAF-25 in the core IFT complex, GFP translational fusion constructs of two IFT proteins, CHE-2 and CHE-11 [30], were crossed into the daf-25(m362) mutant background and analyzed by time-lapse microscopy. The velocities of IFT transport of CHE-2 and CHE-11, as determined by kymograph analysis, were unchanged in daf-25 compared to that of wild type animals (Figure 4). Specifically, transport velocities in the middle segment were ∼0.7 µm/s, and in the distal segments ∼1.2 µm/s, exactly as reported for all studied IFT proteins [36]. Collectively, our data show that DAF-25 is not essential for IFT, and is therefore unlikely to be a core component of IFT transport particles—consistent with the findings that the ciliary ultrastructure of the daf-25 mutant is intact (Figure S3). However, its accumulation within cilia in the retrograde IFT mutant does suggest that it is associated with (i.e., transported by) the IFT machinery.

Fig. 4. DAF-25 depends on IFT for proper localization within cilia but is not essential for the IFT process.

The DAF-25::GFP translational fusion was crossed into che-11(e1810) and assayed for protein accumulation. As seen in (A), DAF-25::GFP localized normally to the cilia in the N2 background, but in the che-11 background DAF-25::GFP accumulates in the cilia, indicating that when IFT is disrupted DAF-25 localization is also disrupted. We conclude that DAF-25 requires the IFT complex for proper transport and/or localization within cilia. Translational fusion reporters for CHE-2::GFP and CHE-11::GFP were crossed into daf-25(m362). As reported previously [34] both reporters localize to basal bodies and ciliary axonemes (B), and have normal velocities in both N2 and daf-25 mutants, as measured in the kymographs (C). Slopes in kymographs correlate with IFT complex speeds and were created as described previously [49]. In daf-25(m362) mutants there is no change in localization (B) or velocity (C) for either of the two reporters, indicating that DAF-25 is not required for normal rates of IFT transport, and is probably not a core IFT protein. cil = cilia, den = dendrite, TZ/BB = transition zone/basal body, asterisk indicates DAF-25::GFP accumulation, DS = distal segment, and MS = middle segment. DAF-25 Is Required for DAF-11 Localization to Cilia

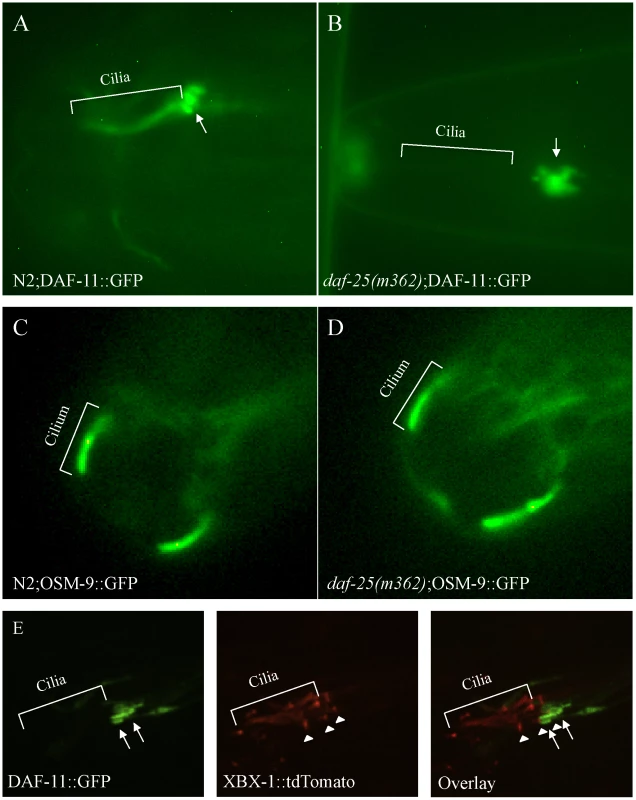

The phenotype of daf-25 is most similar to that of daf-11, and our epistasis results placed daf-25 at the same position in the genetic pathway previously reported for daf-11 [37]. To test for possible functional interactions, a strain harboring DAF-11::GFP (gift from Dr. James Thomas), which is known to localize to cilia [12], was crossed with two daf-25 mutants (m98 and m362). In wild-type animals, the DAF-11::GFP protein localized to the sensory cilia of the olfactory neuron pairs ASI, ASJ, ASK, AWB and AWC (Figure 5A), all of which express DAF-25::GFP (Figure 3). In both daf-25 mutants, the DAF-11::GFP protein was observed only in a region near the base of cilia, rather than along their length (Figure 5B). To assess more precisely where the DAF-11::GFP protein is mislocalized, we introduced into the same strain a ciliary (IFT) marker, namely tdTomato-tagged XBX-1 (a gift from Dr. B. Yoder), which localizes at basal bodies and along the ciliary axoneme [38]. Visualization of the two fluorescently-tagged proteins in the daf-25 mutant revealed that DAF-11::GFP accumulates at the very distal end of dendrites, with little or no localization to the basal body-ciliary structures (Figure 5E). This indicates that DAF-25 is required for the proper localization of DAF-11 to the cilia, providing a likely explanation for the similarities between the daf-11 and daf-25 mutant phenotypes. To test if the DAF-25-DAF-11 functional interaction is specific, GFP-tagged ciliary channel proteins (OSM-9/TRPV4 and TAX-4/CNGA1) and IFT-associated proteins (CHE-2/IFT80, CHE-11/IFT140, CHE-13/IFT57, BBS-8/TTC8, OSM-5/IFT88 and XBX-1/D2LIC) were also crossed into the daf-25(m362) mutant background. All eight reporters showed normal localization to the olfactory cilia in the wild-type N2 and daf-25(m362) strains, indicating the possible specificity of DAF-25 for guanylyl cyclases (OSM-9::GFP localization in the daf-25 mutant shown in Figure 5C and 5D; the remaining constructs are presented in Figure S6). The mislocalization of DAF-11::GFP in daf-25(m362) was not suppressed by daf-12(sa204) (Figure S7). This indicates that it is the abrogation of DAF-25 rather than entry into dauer that controls the ciliary localization of DAF-11.

Fig. 5. DAF-25 is required for the localization of a guanylyl cyclase (DAF-11) to cilia.

The guanylyl cyclase DAF-11::GFP translational fusion protein was expressed in both N2 and daf-25(m362) genetic backgrounds. In wild type (A), DAF-11::GFP was localized to the ASI, ASJ or ASK sensory cilia, but was limited to the distal end of the dendrites (indicated by arrow) and largely excluded from basal body-ciliary structures in daf-25(m362) cilia (B). Normal ciliary localization was seen for the transient receptor potential channel (TRPV4) OSM-9::GFP reporter gene in both wild type (C) and daf-25(m362) (D). Also, no change in localization was seen for TAX-4/CNGA1, CHE-2/IFT80, CHE-11/IFT140, CHE-13/IFT57, BBS-8/TTC8, OSM-5/IFT88 and XBX-1/D2LIC in daf-25 mutants (Figure S6). In (E), DAF-11::GFP and XBX-1::tdTomato are co-expressed in the amphid cilia in daf-25(m362) mutants. XBX-1::tdTomato localizes to the basal body (indicated by arrowhead) and cilia while DAF-11::GFP localizes to the distal end of the dendrite (indicated by arrow). No overlap in protein localization is observed indicating that DAF-11::GFP shows very little, if any localization to the basal body and no expression in the cilia. XBX-1::tdTomato is expressed in all of the amphid cilia while DAF-11::GFP is expressed in a subset. The GFP reporter results suggest a potentially specific function for DAF-25 in cilia. This finding is consistent with the reported regulation of daf-25 by the ciliogenic DAF-19 RFX-type transcription factor [39]. Taken together, DAF-25 appears to be an adaptor protein required for the transport or tethering of the guanylyl cyclase DAF-11 within sensory cilia.

Conservation of Function for DAF-25/Ankmy2

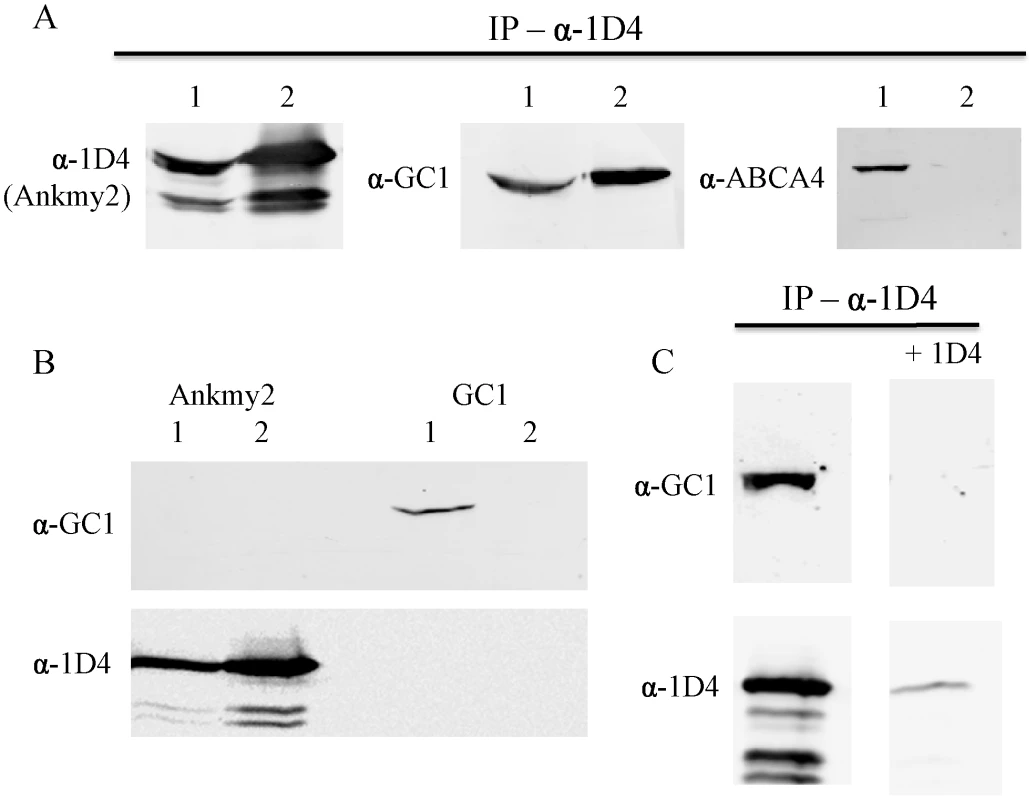

To ascertain if a functional association between DAF-25/Ankmy2 and guanylyl cyclase is evolutionarily conserved, we used a pull-down experiment to test whether mouse Ankmy2 interacts with the retinal-specific guanylyl cyclase GC1, a mammalian homolog of DAF-11 present within ciliary photoreceptors. We amplified Ankmy2 cDNA from a mouse retinal cDNA preparation (gift from Simon Kaja), and constructed a cDNA clone with the rhodopsin 1D4 epitope to use for co-IP experiments with anti-1D4 monoclonal antibody [40]. We co-expressed both in HEK293 cells to test for GC1 co-immunoprecipitation with the 1D4 epitope-tagged Ankmy2 (HEK293 cells do not express rhodopsin). Pull-down of Ankmy2 co-precipitated GC1, but not another control protein (retinal membrane protein ABCA4; Figure 6). This indicates that the functional interaction between DAF-25/Ankmy2 and guanylyl cyclase observed in ciliated sensory cells may be conserved between mouse and worm.

Fig. 6. Ankmy2 and GC1 can be co-precipitated in HEK293 cells.

In (A), detergent-solubilized extracts of HEK293 cells co-expressing Ankmy2-1D4 and either GC1 of ABCA4 were immununoprecipitated on a Rho 1D4-Sepharose matrix and the bound protein was analyzed on Western blots labeled with Rho 1D4 for detection of Ankmy2 and antibodies to GC1 or ABCA4 to detect co-precipitating proteins. Precipitation of 1D4-tagged Ankmy2 with 1D4 antibody also pulls down GC1 (retinal guanylyl cyclase), but not ABCA4 (retinal expressed ATP-binding Cassette, sub-family A, member 4). This indicates that GC1 forms a protein complex with Ankmy2, implying conservation of the functional interaction between DAF-11 and DAF-25. Lane 1 indicates the input proteins (whole cell lysate) and lane 2 indicates elution from immunoaffinity matrix. In (B) detergent-solubilized extracts of HEK293 cells expressing only Ankmy2-1D4 or GC1 were immunoprecipitated on a Rho 1D4 immunoaffinity matrix and analyzed on Western blots labeled with an anti-GC1 antibody or Rho 1D4 antibody. Lane 1: Input; lane 2: bound protein. The presence of Ankmy2-1D4 but not GC1 in the bound fractions indicates that GC1 does not nonspecifically interact with the Rho 1D4 immunoaffinity matrix. In (C), HEK293 cells co-expressing Ankmy2-1D4 and GC1 were co-immunoprecipitated on a Rho 1D4 immunoaffinity matrix in the absence or the presence of excess competing 1D4 peptide. Both Ankmy2-1D4 and GC1 bound in the absence of peptide. In the presence of the 1D4 peptide less than 10% of the Ankmy2 bound. Discussion

In this study, we have identified in a genetic screen for Dauer formation mutants a novel MYND domain-containing ciliary protein, DAF-25, that is required for the proper localization of a guanylyl cyclase (DAF-11) to sensory cilia. Disruption of DAF-25 does not interfere with intraflagellar transport (IFT) or ciliary ultrastructure, but the protein accumulates in a che-11 retrograde IFT mutant. We therefore propose that DAF-25 is associated with IFT not as a ‘core’ protein but instead as an adaptor for transporting ciliary cargo. In our model, abrogation of DAF-25 would thereby not allow transport of DAF-11, which explains the improper localization of DAF-11 in daf-25 mutants at the very base of cilia and the similarity in phenotype between daf-11 and daf-25 mutants.

The amino acid sequence and domain structure similarity between DAF-25 and Ankmy2 suggests an important function for the latter mammalian protein that may be similar to DAF-25 in C. elegans. We attempted to co-immunoprecipitate DAF-25 and DAF-11 in C. elegans but were unable to satisfactorily remove a sufficient amount of background proteins to avoid confounding any identified interaction (data not shown). We also showed that the retinal guanylyl cyclase GC1 binds to Ankmy2, and we propose that the functional relationship between DAF-25 and DAF-11 is conserved between Ankmy2 and GC1 in ciliated photoreceptor cells. Indeed, Ankmy2 may be required for the transport of not only GC1 but perhaps other cilia-targeted guanylyl cyclases as well as other cilia-targeted proteins in mammals. Further studies will be required to experimentally confirm whether Ankmy2 is required for transport of GC1 to the rod outer segment, and to test if Ankmy2 lesions result in retinal disease or a ciliopathy syndrome that includes retinopathies. Mutations in ciliogenesis and cilia related genes cause human disease phenotypes including Bardet-Biedl syndrome, retinopathies, obesity, situs inversus and polycystic kidney disease, among others [41], [42]. Interestingly, GC1 and the nuclear hormone receptor Nr2e3 shown to regulate Ankmy2 expression in mouse retina both harbor mutations in patients with retinal disease [43], [44].

While this research was being conducted we became aware of another group that cloned and characterized chb-3 (Y48G1A.3/daf-25/Ankmy2) as a suppressor of the che-2 body size phenotype [45]. Fujiwara et al., (in press) describe the cloning of chb-3/daf-25 and its essential role in GCY-12 cilia localization. They show that DAF-25 is required in a subset of sensory neurons to rescue the phenotypes they assayed (dauer formation and body size) using a tax-4 promoter. This indicates that DAF-25 function is required in the neurons where cGMP signaling takes place (TAX-4 is a subunit of cGMP-gated calcium channel). They also show expression of DAF-25 in the ASJ neurons (one pair of neurons where DAF-11 is expressed) is required for rescue of the dauer phenotype, also indicating a cell autonomous role for DAF-25. It is interesting that screens for the Daf-c and Chb (che-2 body size suppressor) phenotypes both resulted in the identification of daf-25/chb-3 and separately identified its apparent ciliary cargos daf-11 and gcy-12, guanylyl cyclases that specifically work in dauer formation and body size, respectively. This indicates that DAF-25/CHB-3/Ankmy2 may interact with cilia-targeted guanylyl cyclases in a general manner and that much of the phenotype of daf-25/chb-3 mutants reflects a global defect in cGMP signaling, potentially along with other unidentified cargo proteins.

In conclusion, our findings uncover a novel ciliary protein that plays an important role in modulating the localization/function of cGMP signaling components, which are known to play a critical role in the function of ciliary photoreceptors [46]. DAF-25/Ankmy2 may also play a role in the ciliary targeting of other as of yet identified proteins. As such, Ankmy2 could participate in phototransduction and be associated with retinopathies, and more generally, could be implicated in other ciliary diseases (ciliopathies).

Methods

Mapping, Epistasis, and Phenotyping daf-25

daf-25 mutations were created by treatment of N2 with 0.25 M EMS, or by mut-2 transposon mobility, and selection for constitutive dauer formation as previously described [22]. For 3-factor mapping, fog-1(e2121) unc-11(e47) was crossed with daf-25(m362) and daf-25(m362) unc-35(e259) was crossed with dpy-5(e61). Scoring the genotypes of the F2 progeny required the phenotyping of F3 progeny (due to the maternal effect of the daf-25 dauer phenotype). Pooled SNP mapping was completed as previously described [30] with some changes. In the Po generation, CB4856 males were crossed to daf-25;unc-11 double mutant hermaphrodites. The F1 males were crossed with CB4856 hermaphrodites. F2 hermaphrodites were selected by absence of Unc progeny. F3 hermaphrodites were placed one to a plate and were selected into wild type or mutant pools based on absence or presence of dauers in the F4. Wild type and mutant pools of F3 hermaphrodites were subject to SNP analysis as previously described [30]. ArrayCGH was done as previously described [47] for the leftmost 2.4 Mbp of Chromosome I with 50 base probes spaced every four base pairs.

Epistasis analysis was performed by crossing daf-25(m362) into daf-12(m20), daf-16(m26), daf-3(mgDf90), daf-10(e1387) and daf-6(e1377). Once the double mutants were isolated, the dauer phenotype was assayed to determine if daf-25 was suppressed fully (no constitutive dauer larvae formed at 25°C), partially (fewer dauer larvae than daf-25(m362) control) or no suppression. Treatment with cGMP was performed as previously described [12] with 5 mM 8-bromo-cGMP (Sigma). Neuronal dye-filling was assayed by incubating a mixed-stage population of each genotype in Vibrant DiI (Molecular Probes) 1000-fold diluted in M9 buffer for one hour followed by washing in M9 and one hour destaining on plates. Chemotaxis assays were performed synchronized day-1 adults as previously described with the volatile attractants trimethyl-thiazole, pyrazine, benzaldehye and isoamyl alcohol [48].

The DAF-25::GFP construct was created by inserting the 2.0 kb promoter region 5′ of the AUG followed by daf-25 cDNA the into the pPD95.77 vector (gift from Dr. Andrew Fire). After microinjection into N2 adults [49] with 10 ug/ml of pRF4 (contains rol-6(su1006)), and 90 ug/ml of DAF-25::GFP plasmid (described above), transgenics lines were established based on the roller phenotype. The extra-chromosomal array mEX179(pdaf-25::DAF-25::GFP, rol-6(su1006)) was crossed into daf-25(m362) and rescue of the Daf-c phenotype was detected by normal non-dauer development in the F3 progeny grown at 25°C. GFP fluorescence was visualized on a Zeiss Axioskop with a Qimaging Retiga 2000R camera.

Intraflagellar Transport and Ciliary Protein Localization Analyses

To measure the integrity of IFT within the daf-25(m362) mutant, kymograph analyses were performed using GFP-tagged CHE-11 and CHE-2 IFT markers. Time-lapse movies were obtained for the different strains, including N2, and kymographs were generated from the resulting stacked tiff images using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA). Rates of fluorescent IFT particle motility along middle and distal segments were measured as described previously [35], [50]. To assess how disrupting IFT affects the ciliary localization of DAF-25::GFP, mEX179 was crossed into che-11 mutants and visualized by microscopy essentially as described [35]. Fluorescence intensity was measured by analyzing images in ImageJ by highlighting the entire head region for each animal, then measuring pixel density minus the pixel density for an equal sized adjacent region. The localization of several GFP–tagged proteins in daf-25(m362) animals, namely DAF-11, OSM-9, TAX-4, CHE-2, CHE-11, CHE-13, BBS-8, OSM-5 and XBX-1, were ascertained by crossing the reporter into the mutant, followed by visualization using standard microscopy. Co-localization was carried out by injecting the osm-5p::XBX-1::tdTomato into daf-25(m362);daf-12(sa204) and crossing it into TJ9386 which carries the DAF-11::GFP reporter [12].

Electron Microscopy

Staged N2 and daf-25 L2 larvae were produced by harvesting eggs from gravid adults by alkaline hypochlorite treatment, followed by overnight hatching in M9 buffer, and subsequent incubation of hatched L1 larvae on seeded NGM plates for 26 hours at 16°C. Worms were then washed directly into a primary fixative of 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Sorensen phosphate buffer. To facilitate rapid ingress of fixative, worms were cut in half using a razor blade under a dissecting microscope, transferred to 1.5 ml Ependorf tubes and fixed for one hour at room temperature. Samples were then centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for two minutes, the supernatant removed and the pellet washed for ten minutes in 0.1 M Sorensen phosphate buffer. The worms were then post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M Sorensen phosphate buffer for one hour at room temperature. Following washing in Sorensen phosphate buffer, specimens were processed for electron microscopy by standard methods. Briefly, they were dehydrated in ascending grades of alcohol to 100%, infiltrated with Epon and placed in aluminum planchetes orientated in a longitudinal aspect and polymerized at 60°C for 24 hours.

Using a Leica UC6 ultramicrotome individual worms were sectioned in cross section from anterior tip, at 1 µm until the area of interest was located as judged by examining the sections stained with toluidine blue by light microscopy. Thereafter, serial ultra-thin sections of 80 nm were taken for electron microscopical examination. These were picked up onto 100 mesh copper grids and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Using a Tecnai Twin (FEI) electron microscope, sections were examined to locate, in the first instance, the most distal (anterior) region of the cilia, then to the more proximal regions of the ciliary apparatus. At each strategic point, distal segment, middle segment and transition zone/fiber regions were tilted using the Compustage of the Tecnai to ensure that the axonemal microtubules were imaged in an exact geometrical normalcy to the imaging system. All images were recorded, at an accelerating voltage (120 kV) and objective aperture of 10 µm, using a MegaView 3 digital recording system.

Co-Expression and Co-Immunoprecipitation of Ankmy2 and Guanylate Cyclase 1 (GC1)

Mouse ankmy2 cDNA, amplified from retinal RNA, was engineered to contain a sequence encoding a 9 amino acid 1D4 C-terminal epitope as previously described [40]. Ankmy2-1D4 and either human GC1 or the retinal ABC transporter ABCA4 as a control were co-expressed in HEK 293 cell. HEK 293 cell extracts were solubilized in 18 mM CHAPS in TBS (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM MgCl2 and Complete inhibitor). The solution was stirred at 4°C for 20 minutes and subsequently centrifuged in an Optima TLA100.4 rotor (Beckman) for 10 minutes at 40,000 rpm to remove any residual unsolubilized material. The solubilized extract was applied to an immunoaffinity resin consisting of the Rho 1D4 antibody conjugated to Sepharose 2B [31]. After incubation at 4°C for one hour, the resin was extensively washed with TBS to remove unbound protein, and the bound proteins were eluted with 0.2 mg/ml of the 1D4 competing peptide in TBS for analysis by Western blot labeled with Rho 1D4 antibody for the detection Ankmy2-1D4 and antibodies to GC1 or ABCA4.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. CassadaRC

RussellRL

1975 The dauer larva, a post-embryonic developmental variant of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 46 326 42

2. HuPJ

2007 Dauer. WormBook 1 19 doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.144.1

3. J JohnsonJF

LerouxMR

2010 cAMP and cGMP signaling: sensory systems with prokaryotic roots adopted by eukaryotic cilia. Trends Cell Biol. In press doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2010.05.005

4. BargmannCI

2006 Chemosensation in C. elegans. WormBook 1 29 doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.123.1

5. PerkinsLA

HedgecockEM

ThomsonJN

CulottiJG

1986 Mutant sensory cilia in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 117 456 487

6. WardA

LiuJ

FengZ

XuXZS

2008 Light-sensitive neurons and channels mediate phototaxis in C. elegans. Nat Neurosci 11 916 922 doi:10.1038/nn.2155

7. BargmannCI

HartwiegE

HorvitzHR

1993 Odorant-selective genes and neurons mediate olfaction in C. elegans. Cell 74 515 527

8. InglisPN

OuG

LerouxMR

ScholeyJM

2007 The sensory cilia of Caenorhabditis elegans. WormBook 1 22 doi:10.1895/wormbook.1.126.2

9. SilvermanMA

LerouxMR

2009 Intraflagellar transport and the generation of dynamic, structurally and functionally diverse cilia. Trends Cell Biol 19 306 316 doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2009.04.002

10. SwobodaP

AdlerHT

ThomasJH

2000 The RFX-type transcription factor DAF-19 regulates sensory neuron cilium formation in C. elegans. Mol cell 5 411 21

11. BellLR

StoneS

YochemJ

ShawJE

HermanRK

2006 The molecular identities of the Caenorhabditis elegans intraflagellar transport genes dyf-6, daf-10 and osm-1. Genetics 173 1275 86

12. BirnbyDA

LinkEM

VowelsJJ

TianH

ColacurcioPL

2000 A transmembrane guanylyl cyclase (DAF-11) and Hsp90 (DAF-21) regulate a common set of chemosensory behaviors in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 155 85 104

13. KimK

SatoK

ShibuyaM

ZeigerDM

ButcherRA

2009 Two Chemoreceptors Mediate Developmental Effects of Dauer Pheromone in C. elegans. Science 326 994 998

14. ZwaalRR

MendelJE

SternbergPW

PlasterkR

1997 Two Neuronal G Proteins are Involved in Chemosensation of the Caenorhabditis elegans Dauer-Inducing Pheromone. Genetics 145 715 727

15. EfimenkoE

BubbK

MakHY

HolzmanT

LerouxMR

2005 Analysis of xbx genes in C. elegans. Development 132 1923 1934 doi:10.1242/dev.01775

16. RiddleDL

SwansonMM

AlbertPS

1981 Interacting genes in nematode dauer larva formation. Nature 290 668 671

17. AlbertPS

BrownSJ

RiddleDL

1981 Sensory control of dauer larva formation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Comp Neurol 198 435 451 doi:10.1002/cne.901980305

18. MaloneEA

ThomasJH

1994 A Screen for Nonconditional Dauer-Constitutive Mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 136 879 886

19. AveryL

BargmannCI

HorvitzHR

1993 The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-31 Gene Affects Multiple Nervous System-Controlled Functions. Genetics 134 455 464

20. AilionM

ThomasJH

2003 Isolation and characterization of high-temperature-induced Dauer formation mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 165 127 44

21. BrennerS

1974 The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 71 94

22. KiffJE

MoermanDG

SchrieferLA

WaterstonRH

1988 Transposon-induced deletions in unc-22 of C. elegans associated with almost normal gene activity. Nature 331 631 633 doi:10.1038/331631a0

23. AntebiA

YehWH

TaitD

HedgecockEM

RiddleDL

2000 daf-12 encodes a nuclear receptor that regulates the dauer diapause and developmental age in C. elegans. Genes Dev 14 1512 1527

24. OggS

ParadisS

GottliebS

PattersonGI

LeeL

1997 The Fork head transcription factor DAF-16 transduces insulin-like metabolic and longevity signals in C. elegans. Nature 389 994 999 doi:10.1038/40194

25. PattersonGI

KoweekA

WongA

LiuY

RuvkunG

1997 The DAF-3 Smad protein antagonizes TGF-beta-related receptor signaling in the Caenorhabditis elegans dauer pathway. Genes Dev 11 2679 2690

26. PerensEA

ShahamS

2005 C. elegans daf-6 encodes a patched-related protein required for lumen formation. Dev Cell 8 893 906 doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.009

27. LarsenPL

AlbertPS

RiddleDL

1995 Genes that regulate both development and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 139 1567 83

28. VowelsJJ

ThomasJH

1994 Multiple chemosensory defects in daf-11 and daf-21 mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 138 303 316

29. StarichTA

HermanRK

KariCK

YehWH

SchackwitzWS

1995 Mutations affecting the chemosensory neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 139 171 188

30. WicksSR

YehRT

GishWR

WaterstonRH

PlasterkRH

2001 Rapid gene mapping in Caenorhabditis elegans using a high density polymorphism map. Nat Genet 28 160 164 doi:10.1038/88878

31. LiuY

ChenW

GaudetJ

CheneyMD

RoudaiaL

2007 Structural basis for recognition of SMRT/N-CoR by the MYND domain and its contribution to AML1/ETO's activity. Cancer Cell 11 483 497 doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2007.04.010

32. HillierLW

ReinkeV

GreenP

HirstM

MarraMA

2009 Massively parallel sequencing of the polyadenylated transcriptome of C. elegans. Genome Res 19 657 666 doi:10.1101/gr.088112.108

33. ShinH

HirstM

BainbridgeMN

MagriniV

MardisE

2008 Transcriptome analysis for Caenorhabditis elegans based on novel expressed sequence tags. BMC Biol 6 30 doi:10.1186/1741-7007-6-30

34. RogersA

AntoshechkinI

BieriT

BlasiarD

BastianiC

2008 WormBase 2007. Nucl Acids Res 36 D612 7

35. BlacqueOE

LiC

InglisPN

EsmailMA

OuG

2006 The WD Repeat-containing Protein IFTA-1 Is Required for Retrograde Intraflagellar Transport. Mol. Biol. Cell 17 5053 5062 doi:10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0571

36. OuG

KogaM

BlacqueOE

MurayamaT

OhshimaY

2007 Sensory ciliogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans: assignment of IFT components into distinct modules based on transport and phenotypic profiles. Mol Biol Cell 18 1554 1569 doi:10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0805

37. ThomasJH

BirnbyDA

VowelsJJ

1993 Evidence for parallel processing of sensory information controlling dauer formation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 134 1105 17

38. SchaferJC

HaycraftCJ

ThomasJH

YoderBK

SwobodaP

2003 XBX-1 encodes a dynein light intermediate chain required for retrograde intraflagellar transport and cilia assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell 14 2057 2070 doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0677

39. BlacqueOE

PerensEA

BoroevichKA

InglisPN

LiC

2005 Functional Genomics of the Cilium, a Sensory Organelle. Curr Biol 15 935 941 doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.059

40. WongJP

ReboulE

MoldayRS

KastJ

2009 A Carboxy-Terminal Affinity Tag for the Purification and Mass Spectrometric Characterization of Integral Membrane Proteins. J Proteome Res 8 2388 2396 doi:10.1021/pr801008c

41. SharmaN

BerbariNF

YoderBK

2008 Ciliary dysfunction in developmental abnormalities and diseases. Curr Top Dev Biol 85 371 427 doi:10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00813-2

42. LancasterMA

GleesonJG

2009 The primary cilium as a cellular signaling center: lessons from disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev 19 220 229 doi:10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.008

43. KitiratschkyVBD

WilkeR

RennerAB

KellnerU

VadalàM

2008 Mutation analysis identifies GUCY2D as the major gene responsible for autosomal dominant progressive cone degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49 5015 5023 doi:10.1167/iovs.08-1901

44. HaiderNB

MollemaN

GauleM

YuanY

SachsAJ

2009 Nr2e3-directed transcriptional regulation of genes involved in photoreceptor development and cell-type specific phototransduction. Exp Eye Res 89 365 372

45. FujiwaraM

SenguptaP

McIntireSL

2002 Regulation of Body Size and Behavioral State of C. elegans by Sensory Perception and the EGL-4 cGMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Neuron 36 1091 1102 doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01093-0

46. WenselTG

2008 Signal transducing membrane complexes of photoreceptor outer segments. Vision Res 48 2052 2061 doi:10.1016/j.visres.2008.03.010

47. MaydanJS

OkadaHM

FlibotteS

EdgleyML

MoermanDG

2009 De Novo identification of single nucleotide mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans using array comparative genomic hybridization. Genetics 181 1673 1677 doi:10.1534/genetics.108.100065

48. SaekiS

YamamotoM

IinoY

2001 Plasticity of chemotaxis revealed by paired presentation of a chemoattractant and starvation in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J Exp Biol 204 1757 1764

49. EvansT

2006 Transformation and microinjection. WormBook. doi/10.1895/ wormbook.1.108.1

50. SnowJJ

OuG

GunnarsonAL

WalkerMRS

ZhouHM

2004 Two anterograde intraflagellar transport motors cooperate to build sensory cilia on C. elegans neurons. Nat Cell Biol 6 1109 1113 doi:10.1038/ncb1186

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2010 Číslo 11- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Genome-Wide Association Meta-Analysis of Cortical Bone Mineral Density Unravels Allelic Heterogeneity at the Locus and Potential Pleiotropic Effects on Bone

- Beyond QTL Cloning

- An Evolutionary Framework for Association Testing in Resequencing Studies

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Two Novel Regions at 11p15.5-p13 and 1p31 with Major Impact on Acute-Phase Serum Amyloid A

- The Functional Interplay between Protein Kinase CK2 and CCA1 Transcriptional Activity Is Essential for Clock Temperature Compensation in Arabidopsis

- Endogenous Viral Elements in Animal Genomes

- Analysis of the 10q11 Cancer Risk Locus Implicates and in Human Prostate Tumorigenesis

- DNA Methylation and Normal Chromosome Behavior in Neurospora Depend on Five Components of a Histone Methyltransferase Complex, DCDC

- Sarcomere Formation Occurs by the Assembly of Multiple Latent Protein Complexes

- Genetic Basis of Growth Adaptation of after Deletion of , a Major Metabolic Gene

- Nomadic Enhancers: Tissue-Specific -Regulatory Elements of Have Divergent Genomic Positions among Species

- The Parental Non-Equivalence of Imprinting Control Regions during Mammalian Development and Evolution

- CTCF-Dependent Chromatin Bias Constitutes Transient Epigenetic Memory of the Mother at the Imprinting Control Region in Prospermatogonia

- Systematic Dissection and Trajectory-Scanning Mutagenesis of the Molecular Interface That Ensures Specificity of Two-Component Signaling Pathways

- Nucleolin Is Required for DNA Methylation State and the Expression of rRNA Gene Variants in

- The Complex Genetic Architecture of the Metabolome

- ATM Limits Incorrect End Utilization during Non-Homologous End Joining of Multiple Chromosome Breaks

- Mutation Disrupts Synaptonemal Complex Formation, Recombination, and Chromosome Segregation in Mammalian Meiosis

- Mismatch Repair–Independent Increase in Spontaneous Mutagenesis in Yeast Lacking Non-Essential Subunits of DNA Polymerase ε

- The Kinesin-3 Motor UNC-104/KIF1A Is Degraded upon Loss of Specific Binding to Cargo

- Epigenetic Silencing of Spermatocyte-Specific and Neuronal Genes by SUMO Modification of the Transcription Factor Sp3

- A Coastal Cline in Sodium Accumulation in Is Driven by Natural Variation of the Sodium Transporter AtHKT1;1

- Cyclin B3 Is Required for Multiple Mitotic Processes Including Alleviation of a Spindle Checkpoint–Dependent Block in Anaphase Chromosome Segregation

- Altered DNA Methylation in Leukocytes with Trisomy 21

- Human-Specific Evolution and Adaptation Led to Major Qualitative Differences in the Variable Receptors of Human and Chimpanzee Natural Killer Cells

- Leptotene/Zygotene Chromosome Movement Via the SUN/KASH Protein Bridge in

- RACK-1 Acts with Rac GTPase Signaling and UNC-115/abLIM in Axon Pathfinding and Cell Migration

- Genome-Wide Effects of Long-Term Divergent Selection

- Endless Forms Most Viral

- Conflict between Noise and Plasticity in Yeast

- Essential Functions of the Histone Demethylase Lid

- The Transcriptional Regulator Rok Binds A+T-Rich DNA and Is Involved in Repression of a Mobile Genetic Element in

- The Cellular Robustness by Genetic Redundancy in Budding Yeast

- Localization of a Guanylyl Cyclase to Chemosensory Cilia Requires the Novel Ciliary MYND Domain Protein DAF-25

- A Buoyancy-Based Screen of Drosophila Larvae for Fat-Storage Mutants Reveals a Role for in Coupling Fat Storage to Nutrient Availability

- A Functional Genomics Approach Identifies Candidate Effectors from the Aphid Species (Green Peach Aphid)

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Two Novel Regions at 11p15.5-p13 and 1p31 with Major Impact on Acute-Phase Serum Amyloid A

- Analysis of the 10q11 Cancer Risk Locus Implicates and in Human Prostate Tumorigenesis

- The Parental Non-Equivalence of Imprinting Control Regions during Mammalian Development and Evolution

- Genome-Wide Effects of Long-Term Divergent Selection

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy