-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Five Questions about Non-Mevalonate Isoprenoid Biosynthesis

article has not abstract

Published in the journal: Five Questions about Non-Mevalonate Isoprenoid Biosynthesis. PLoS Pathog 7(12): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002323

Category: Pearls

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002323Summary

article has not abstract

What Is an Isoprenoid?

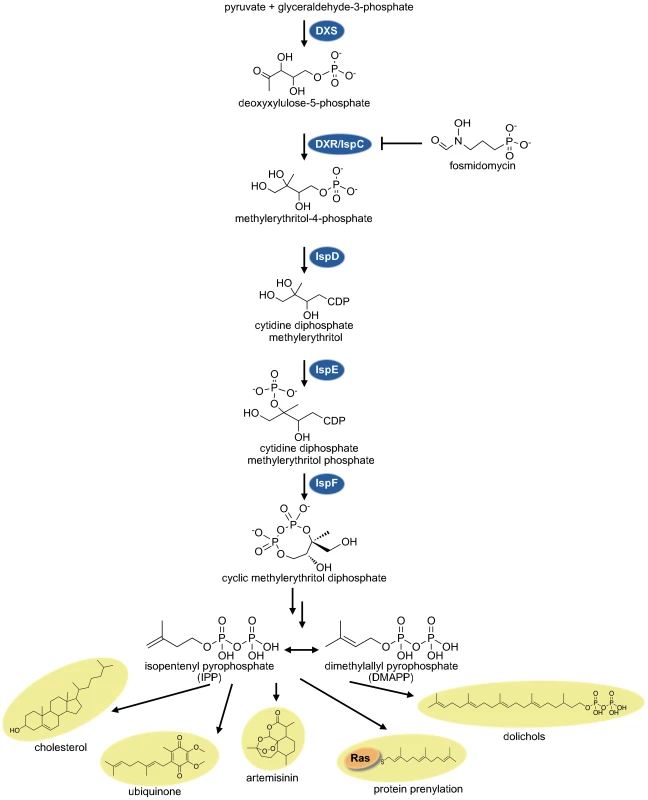

Isoprenoids (also referred to as terpenoids) are the largest group of natural products, comprising over 25,000 known compounds [1]. Each member of this class is assembled from 5-carbon (C5) isoprene units and derived metabolically from the basic building block isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP). Subsequent metabolic reactions (such as cyclization) generate enormous complexity and diversity from these basic starting materials. Isoprenoids are vital to all organismal classes, supporting core cellular functions such as aerobic respiration (ubiquinones) and membrane stability (cholesterol) (Figure 1). Isoprenoids also form the largest group of so-called secondary metabolites, such as the extremely diverse classes of plant defensive terpenoids that are widely exploited as perfumes, food additives, and pharmaceutical agents (e.g., the antimalarial compound artemisinin) [2].

What Is the Non-Mevalonate (MEP) Pathway of Isoprenoid Biosynthesis?

The basic isoprenoid building blocks (IPP and DMAPP) are generated in cells by one of two distinct biosynthetic routes. The classical mevalonate (MVA) pathway was first described in yeast and mammals in the 1950s [3]. IPP is synthesized from acetyl-CoA via the key metabolite mevalonate (MVA). The widely used “statin” class of cholesterol-lowering drugs targets the rate-limiting enzyme of the MVA pathway, HMG-CoA reductase.

By the early 1990s, however, the existence of an alternative route to IPP had become clear through metabolic labeling studies in bacteria and plants [4]. This alternate “non-mevalonate” pathway does not share any enzymes or metabolites with the MVA pathway. It begins by generation of deoxyxyluose 5-phosphate (DOXP) from pyruvate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate. The first dedicated metabolite of this pathway, methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP)—from which the pathway derives its name—is then generated from DOXP by deoxyxylulose phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR, also known as IspC). Subsequent enzymatic steps convert MEP to IPP/DMAPP for synthesis of downstream isoprenoids. Since the MEP pathway is linear, each of the enzymes in this pathway is required for de novo isoprenoid biosynthesis.

Which Microbes Use the MEP Pathway?

The two isoprenoid biosynthetic routes, the mevalonate (MVA) and non-mevalonate (MEP) pathways, have distinct evolutionary origins and are phylogenetically compartmentalized [5], [6]. Archaebacteria and most eukaryotes, including all metazoans and fungi, use the MVA pathway. In contrast, the overwhelming majority of eubacteria use the MEP pathway, including key pathogens such as all Gram-negative bacteria and mycobacteria. Notable exceptions include several clinically important Gram-positive organisms, including staphylococci and streptococci, which have retained the MVA pathway, and several obligate intracellular organisms, including rickettsiae and mycoplasmas, which have lost de novo isoprenoid metabolism altogether.

While most eukaryotes use the MVA pathway, phyla that have acquired a plastid organelle (either a true chloroplast, such as in plants, or a non-photosynthetic relic plastid) possess the eubacteria-like MEP pathway. In microbes, this includes the Apicomplexan protozoan pathogens Toxoplasma gondii (which causes toxoplasmosis) and the malaria-causing Plasmodia species, including the agent of severe malaria, Plasmodium falciparum. While plants contain both the MVA and MEP pathways, the Apicomplexans do not contain the MVA pathway and exclusively generate isoprenoids via the MEP pathway.

Why Are Isoprenoids Essential in Pathogenic Microbes?

Isoprenoids are essential in all eubacteria in which they have been studied [7]–[9]. Genetic or chemical disruption of enzymes in this pathway is only possible with a redundant route for isoprenoid biosynthesis (either media supplementation with isoprenoids or transgenic expression of the MVA pathway). Isoprenoids are key to several core bacterial cellular functions. In eubacteria, there are at least three groups of isoprenoid compounds that appear to be essential—ubiquinones, menaquinones, and dolichols. Ubiquinones and menaquinones are electron carriers and major components of the aerobic and anaerobic respiratory chains, respectively [10]. Dolichols are long-chain, membrane-bound isoprenols, which are required for cell wall peptidoglycan synthesis [11]. Agents that block isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria therefore result in spheroplast formation and cell death [12].

The MEP pathway is also clearly essential in Apicoplexan eukaryotes, including the protozoan malaria parasite P. falciparum [13]–[15]. In contrast to eubacteria, it is not as clear why the malaria parasite needs isoprenoids. The clinical symptoms of malaria infection arise from the developmental cycle of the parasite within human erythrocytes. This privileged niche has resulted in several metabolic peculiarities. While cholesterol is essential to eukaryotic membrane stability, the parasite does not have de novo cholesterol biosynthesis and scavenges membrane cholesterol from host erythrocyte membranes [16]. The malaria parasite depends on glycolysis and does not use mitochondrial respiration for ATP production in the intraerythrocytic cycle [17]. In eukaryotes, dolichols are necessary for protein N-glycosylation, but P. falciparum produces severely truncated N-glycosyl groups that may not be required for protein function [18]. Finally, the malaria parasite makes plant-like signaling molecules (carotenoids), but these also do not have a known biological function [19]. The malaria parasite does have well-characterized protein prenyltransferases, which are expressed during the intraerythrocytic cycle [20], [21]. Protein prenylation is the isoprenyl modification of proteins, such as small GTPases. Either farnesyl (15 carbon) or geranylgeranyl (20 carbon) groups are attached to C-terminal cysteines by one of three prenyltransferases. Multiple classes of prenyltransferase inhibitors kill the malaria parasite, strongly suggesting that at least protein prenylation is an essential function of isoprenoid biosynthesis in malaria [20], [22].

Why Is the MEP Pathway a Good Antimicrobial Drug Target?

The MEP pathway has a number of characteristics that make it a favorable target for antimicrobial drug development. Much like bacterial cell wall biosynthesis, which has been so successfully targeted by antibacterial agents, the MEP pathway is essential for microbial growth, and none of the enzymes of this pathway are present in mammalian cells. Validation of many of the properties of a new isoprenoid-inhibitor class of antibiotic has come from studies of the small phosphonic acid compound fosmidomycin. Fosmidomycin inhibits DXR (the first dedicated step in the MEP pathway) in multiple organisms [9], [15], [23]. It kills E. coli and P. falciparum, can treat malaria in field trials, and has been validated as an inhibitor of isoprenoid biosynthesis in vivo [14], [24]. Due to its highly charged structure, it has suboptimal pharmacokinetic properties, and is also excluded from and non-toxic to several organisms whose DXR enzyme is otherwise inhibited in vitro by fosmidomycin (including T. gondii and Mycobacterium tuberculosis) [9], [15]. Despite these challenges, fosmidomycin is currently in Phase II clinical trials in combination therapy to treat malaria, because of its favorable safety profile. Very high doses of fosmidomycin appear to be clinically safe—the oral mouse LD50 is a remarkable >11,000 mg/kg—presumably since there is no mammalian homolog to be inhibited [25].

Drug resistance has created an urgent need for new antimicrobial agents to combat Gram-negative bacteria, M. tuberculosis, and P. falciparum, which share the MEP pathway. New drugs that inhibit this pathway hold great promise as broad-spectrum agents, with potential appeal for commercially viable pharmaceutical development in the first-world as antibacterial agents (against resistant hospital-acquired infections, for example) and use in developing nations in combination therapies for malaria and tuberculosis.

Fig. 1. The non-mevalonate MEP pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis.

Isoprenoids are derived from the basic 5-carbon isoprenoid building blocks isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP). In the MEP pathway, IPP and DMAPP are generated from pyruvate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate. Enzymes of this pathway are named here according to their E. coli homologs (DXR/IspC, IspD, IspE, and IspF). Fosmidomycin is a phosphonic acid antibiotic (PubChem compound ID 572) that inhibits a rate-limiting enzyme of this pathway (DXR/IspC) and blocks isoprenoid biosynthesis in vivo. Isoprenoids have great diversity in structure and cellular function—from plasma membrane stability (cholesterol), electron transport (ubiquinone), and cell wall biosynthesis (dolichols) to protein modification (as prenyl groups) and secondary metabolites (such as artemisinin).

Zdroje

1. ConnollyJ 1991 Dictionary of terpenoids. Chapman & Hall/CRC 2156

2. GershenzonJDudarevaN 2007 The function of terpene natural products in the natural world. Nat Chem Biol 3 408 414

3. EndoA 1992 The discovery and development of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. J Lipid Res 33 1569 1582

4. Rodriguez-ConcepcionMBoronatA 2002 Elucidation of the methylerythritol phosphate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria and plastids. A metabolic milestone achieved through genomics. Plant Physiol 130 1079 1089

5. LangeBMRujanTMartinWCroteauR 2000 Isoprenoid biosynthesis: the evolution of two ancient and distinct pathways across genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 13172 13177

6. BoucherYDoolittleWF 2000 The role of lateral gene transfer in the evolution of isoprenoid biosynthesis pathways. Mol Microbiol 37 703 716

7. KuzuyamaTTakahashiSSetoH 1999 Construction and characterization of Escherichia coli disruptants defective in the yaeM gene. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 63 776 778

8. CornishRMRothJRPoulterCD 2006 Lethal Mutations in the Isoprenoid Pathway of Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol 188 1444 1450 doi:10.1128/JB.188.4.1444-1450.2006

9. BrownACParishT 2008 Dxr is essential in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and fosmidomycin resistance is due to a lack of uptake. BMC Microbiol 8 78 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-8-78

10. SøballeBPooleRK 1999 Microbial ubiquinones: multiple roles in respiration, gene regulation and oxidative stress management. Microbiology 145 Pt 8 1817 1830

11. AndersonRGHusseyHBaddileyJ 1972 The mechanism of wall synthesis in bacteria. The organization of enzymes and isoprenoid phosphates in the membrane. Biochem J 127 11 25

12. ShigiY 1989 Inhibition of bacterial isoprenoid synthesis by fosmidomycin, a phosphonic acid-containing antibiotic. J Antimicrob Chemother 24 131 145

13. OdomARVan VoorhisWC 2010 Functional genetic analysis of the Plasmodium falciparum deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase gene. Mol Biochem Parasitol 170 108 111 doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.12.001

14. ZhangBWattsKMHodgeDKempLMHunstadDA 2011 A second target of the antimalarial and antibacterial agent fosmidomycin revealed by cellular metabolic profiling. Biochemistry 50 3570 3577 doi:10.1021/bi200113y

15. NairSCBrooksCFGoodmanCDStrurmAMcFaddenGI 2011 Apicoplast isoprenoid precursor synthesis and the molecular basis of fosmidomycin resistance in Toxoplasma gondii. J Exp Med 208 1547 1559 doi:10.1084/jem.20110039

16. LabaiedMJayabalasinghamBBanoNChaSJSandovalJ 2010 Plasmodium salvages cholesterol internalized by LDL and synthesized de novo in the liver. Cell Microbiol 13 569 586 doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01555.x

17. PainterHJMorriseyJMMatherMWVaidyaAB 2007 Specific role of mitochondrial electron transport in blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 446 88 91 doi:10.1038/nature05572

18. Dieckmann-SchuppertABenderSOdenthal-SchnittlerMBauseESchwarzRT 1992 Apparent lack of N-glycosylation in the asexual intraerythrocytic stage of Plasmodium falciparum. Eur J Biochem 205 815 825

19. TonhosoloRD'AlexandriFLde RossoVVGazariniMLMatsumuraMY 2009 Carotenoid biosynthesis in intraerythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem 284 9974 9985

20. ChakrabartiDDa SilvaTBargerJPaquetteSPatelH 2002 Protein farnesyltransferase and protein prenylation in Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem 277 42066 42073 doi:10.1074/jbc.M202860200

21. ChakrabartiDAzamTDelVecchioC 1998 Protein prenyl transferase activities of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol 94 175 184

22. GlennMPChangSYHorneyCRivasKYokoyamaK 2006 Structurally simple, potent, Plasmodium selective farnesyltransferase inhibitors that arrest the growth of malaria parasites. J Med Chem 49 5710 5727

23. JomaaHWiesnerJSanderbrandSAltincicekBWeidemeyerC 1999 Inhibitors of the nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as antimalarial drugs. Science 285 1573 1576

24. BorrmannSLundgrenIOyakhiromeSImpoumaBMatsieguiPB 2006 Fosmidomycin plus Clindamycin for Treatment of Pediatric Patients Aged 1 to 14 Years with Plasmodium falciparum Malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50 2713 2718 doi:10.1128/AAC.00392-06

25. KamiyaTHasimotoMHemmiKTakenoH Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Company, Limited 1978 Hydroxyaminohydrocarbonphosphonic acids. U.S. Patent No 4206156

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiológia Infekčné lekárstvo Laboratórium

Článek Genesis of Mammalian Prions: From Non-infectious Amyloid Fibrils to a Transmissible Prion DiseaseČlánek Role of Permissive Neuraminidase Mutations in Influenza A/Brisbane/59/2007-like (H1N1) VirusesČlánek Allelic Variation on Murine Chromosome 11 Modifies Host Inflammatory Responses and Resistance toČlánek Multifaceted Regulation of Translational Readthrough by RNA Replication Elements in a TombusvirusČlánek Latent KSHV Infection of Endothelial Cells Induces Integrin Beta3 to Activate Angiogenic PhenotypesČlánek Controlling Viral Immuno-Inflammatory Lesions by Modulating Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2011 Číslo 12- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Očkování proti virové hemoragické horečce Ebola experimentální vakcínou rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP

- Koronavirus hýbe světem: Víte jak se chránit a jak postupovat v případě podezření?

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Inhibition of Apoptosis and NF-κB Activation by Vaccinia Protein N1 Occur via Distinct Binding Surfaces and Make Different Contributions to Virulence

- Genesis of Mammalian Prions: From Non-infectious Amyloid Fibrils to a Transmissible Prion Disease

- Kaposi's Sarcoma Herpesvirus microRNAs Target Caspase 3 and Regulate Apoptosis

- Nutritional Immunology: A Multi-Dimensional Approach

- Role of Permissive Neuraminidase Mutations in Influenza A/Brisbane/59/2007-like (H1N1) Viruses

- Vaccinomics and Personalized Vaccinology: Is Science Leading Us Toward a New Path of Directed Vaccine Development and Discovery?

- Symbiont Infections Induce Strong Cytoplasmic Incompatibility in the Tsetse Fly

- Allelic Variation on Murine Chromosome 11 Modifies Host Inflammatory Responses and Resistance to

- Computational and Biochemical Analysis of the Effector AvrBs2 and Its Role in the Modulation of Type Three Effector Delivery

- Granzyme B Inhibits Vaccinia Virus Production through Proteolytic Cleavage of Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 4 Gamma 3

- Association of Activating KIR Copy Number Variation of NK Cells with Containment of SIV Replication in Rhesus Monkeys

- Fungal Virulence and Development Is Regulated by Alternative Pre-mRNA 3′End Processing in

- versus the Host: Remodeling of the Bacterial Outer Membrane Is Required for Survival in the Gastric Mucosa

- Follicular Dendritic Cell-Specific Prion Protein (PrP) Expression Alone Is Sufficient to Sustain Prion Infection in the Spleen

- Autophagy Protein Atg3 is Essential for Maintaining Mitochondrial Integrity and for Normal Intracellular Development of Tachyzoites

- Longevity and Composition of Cellular Immune Responses Following Experimental Malaria Infection in Humans

- Sequential Adaptive Mutations Enhance Efficient Vector Switching by Chikungunya Virus and Its Epidemic Emergence

- Acquisition of Pneumococci Specific Effector and Regulatory Cd4 T Cells Localising within Human Upper Respiratory-Tract Mucosal Lymphoid Tissue

- The Meaning of Death: Evolution and Ecology of Apoptosis in Protozoan Parasites

- Deficiency of a Niemann-Pick, Type C1-related Protein in Is Associated with Multiple Lipidoses and Increased Pathogenicity

- Feeding Cells Induced by Phytoparasitic Nematodes Require γ-Tubulin Ring Complex for Microtubule Reorganization

- Eight RGS and RGS-like Proteins Orchestrate Growth, Differentiation, and Pathogenicity of

- Prion Uptake in the Gut: Identification of the First Uptake and Replication Sites

- Nef Decreases HIV-1 Sensitivity to Neutralizing Antibodies that Target the Membrane-proximal External Region of TMgp41

- Multifaceted Regulation of Translational Readthrough by RNA Replication Elements in a Tombusvirus

- A Temporal Role Of Type I Interferon Signaling in CD8 T Cell Maturation during Acute West Nile Virus Infection

- The Membrane Fusion Step of Vaccinia Virus Entry Is Cooperatively Mediated by Multiple Viral Proteins and Host Cell Components

- HIV-1 Capsid-Cyclophilin Interactions Determine Nuclear Import Pathway, Integration Targeting and Replication Efficiency

- Neonatal CD8 T-cell Hierarchy Is Distinct from Adults and Is Influenced by Intrinsic T cell Properties in Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infected Mice

- Two Novel Transcriptional Regulators Are Essential for Infection-related Morphogenesis and Pathogenicity of the Rice Blast Fungus

- Five Questions about Non-Mevalonate Isoprenoid Biosynthesis

- The Human Cytomegalovirus UL11 Protein Interacts with the Receptor Tyrosine Phosphatase CD45, Resulting in Functional Paralysis of T Cells

- Wall Teichoic Acids of Limit Recognition by the Drosophila Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein-SA to Promote Pathogenicity

- A Novel Role for the NLRC4 Inflammasome in Mucosal Defenses against the Fungal Pathogen

- Inflammasome-dependent Pyroptosis and IL-18 Protect against Lung Infection while IL-1β Is Deleterious

- CNS Recruitment of CD8+ T Lymphocytes Specific for a Peripheral Virus Infection Triggers Neuropathogenesis during Polymicrobial Challenge

- Latent KSHV Infection of Endothelial Cells Induces Integrin Beta3 to Activate Angiogenic Phenotypes

- A Receptor-based Switch that Regulates Anthrax Toxin Pore Formation

- Targeting of Heparin-Binding Hemagglutinin to Mitochondria in Macrophages

- Chikungunya Virus Neutralization Antigens and Direct Cell-to-Cell Transmission Are Revealed by Human Antibody-Escape Mutants

- Ce-Duox1/BLI-3 Generated Reactive Oxygen Species Trigger Protective SKN-1 Activity via p38 MAPK Signaling during Infection in

- Structural Elucidation and Functional Characterization of the Effector Protein ATR13

- Controlling Viral Immuno-Inflammatory Lesions by Modulating Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling

- SAMHD1-Deficient CD14+ Cells from Individuals with Aicardi-Goutières Syndrome Are Highly Susceptible to HIV-1 Infection

- Acid Stability of the Hemagglutinin Protein Regulates H5N1 Influenza Virus Pathogenicity

- Cryo Electron Tomography of Herpes Simplex Virus during Axonal Transport and Secondary Envelopment in Primary Neurons

- A Novel Human Cytomegalovirus Locus Modulates Cell Type-Specific Outcomes of Infection

- Juxtamembrane Shedding of AMA1 Is Sequence Independent and Essential, and Helps Evade Invasion-Inhibitory Antibodies

- Pathogenesis and Host Response in Syrian Hamsters following Intranasal Infection with Andes Virus

- IRGM Is a Common Target of RNA Viruses that Subvert the Autophagy Network

- Epstein-Barr Virus Evades CD4 T Cell Responses in Lytic Cycle through BZLF1-mediated Downregulation of CD74 and the Cooperation of vBcl-2

- Quantitative Multicolor Super-Resolution Microscopy Reveals Tetherin HIV-1 Interaction

- Late Repression of NF-κB Activity by Invasive but Not Non-Invasive Meningococcal Isolates Is Required to Display Apoptosis of Epithelial Cells

- Polar Flagellar Biosynthesis and a Regulator of Flagellar Number Influence Spatial Parameters of Cell Division in

- Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 3C Stabilizes Gemin3 to Block p53-mediated Apoptosis

- The Enteropathogenic (EPEC) Tir Effector Inhibits NF-κB Activity by Targeting TNFα Receptor-Associated Factors

- Toward an Integrated Model of Capsule Regulation in

- A Systematic Screen to Discover and Analyze Apicoplast Proteins Identifies a Conserved and Essential Protein Import Factor

- A Host Small GTP-binding Protein ARL8 Plays Crucial Roles in Tobamovirus RNA Replication

- Comparative Pathobiology of Fungal Pathogens of Plants and Animals

- Synergistic Roles of Eukaryotic Translation Elongation Factors 1Bγ and 1A in Stimulation of Tombusvirus Minus-Strand Synthesis

- Engineered Immunity to Infection

- Inflammatory Monocytes and Neutrophils Are Licensed to Kill during Memory Responses

- Sialidases Affect the Host Cell Adherence and Epsilon Toxin-Induced Cytotoxicity of Type D Strain CN3718

- Eurasian-Origin Gene Segments Contribute to the Transmissibility, Aerosol Release, and Morphology of the 2009 Pandemic H1N1 Influenza Virus

- SARS Coronavirus nsp1 Protein Induces Template-Dependent Endonucleolytic Cleavage of mRNAs: Viral mRNAs Are Resistant to nsp1-Induced RNA Cleavage

- Identification and Characterization of a Novel Non-Structural Protein of Bluetongue Virus

- Functional Analysis of the Kinome of the Wheat Scab Fungus

- Norovirus Regulation of the Innate Immune Response and Apoptosis Occurs via the Product of the Alternative Open Reading Frame 4

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Controlling Viral Immuno-Inflammatory Lesions by Modulating Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling

- Fungal Virulence and Development Is Regulated by Alternative Pre-mRNA 3′End Processing in

- Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 3C Stabilizes Gemin3 to Block p53-mediated Apoptosis

- Engineered Immunity to Infection

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy