-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Development of a Transformation System for : Restoration of Glycogen Biosynthesis by Acquisition of a Plasmid Shuttle Vector

Chlamydia trachomatis remains one of the few major human pathogens for which there is no transformation system. C. trachomatis has a unique obligate intracellular developmental cycle. The extracellular infectious elementary body (EB) is an infectious, electron-dense structure that, following host cell infection, differentiates into a non-infectious replicative form known as a reticulate body (RB). Host cells infected by C. trachomatis that are treated with penicillin are not lysed because this antibiotic prevents the maturation of RBs into EBs. Instead the RBs fail to divide although DNA replication continues. We have exploited these observations to develop a transformation protocol based on expression of β-lactamase that utilizes rescue from the penicillin-induced phenotype. We constructed a vector which carries both the chlamydial endogenous plasmid and an E.coli plasmid origin of replication so that it can shuttle between these two bacterial recipients. The vector, when introduced into C. trachomatis L2 under selection conditions, cures the endogenous chlamydial plasmid. We have shown that foreign promoters operate in vivo in C. trachomatis and that active β-lactamase and chloramphenicol acetyl transferase are expressed. To demonstrate the technology we have isolated chlamydial transformants that express the green fluorescent protein (GFP). As proof of principle, we have shown that manipulation of chlamydial biochemistry is possible by transformation of a plasmid-free C. trachomatis recipient strain. The acquisition of the plasmid restores the ability of the plasmid-free C. trachomatis to synthesise and accumulate glycogen within inclusions. These findings pave the way for a comprehensive genetic study on chlamydial gene function that has hitherto not been possible. Application of this technology avoids the use of therapeutic antibiotics and therefore the procedures do not require high level containment and will allow the analysis of genome function by complementation.

Published in the journal: Development of a Transformation System for : Restoration of Glycogen Biosynthesis by Acquisition of a Plasmid Shuttle Vector. PLoS Pathog 7(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002258

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002258Summary

Chlamydia trachomatis remains one of the few major human pathogens for which there is no transformation system. C. trachomatis has a unique obligate intracellular developmental cycle. The extracellular infectious elementary body (EB) is an infectious, electron-dense structure that, following host cell infection, differentiates into a non-infectious replicative form known as a reticulate body (RB). Host cells infected by C. trachomatis that are treated with penicillin are not lysed because this antibiotic prevents the maturation of RBs into EBs. Instead the RBs fail to divide although DNA replication continues. We have exploited these observations to develop a transformation protocol based on expression of β-lactamase that utilizes rescue from the penicillin-induced phenotype. We constructed a vector which carries both the chlamydial endogenous plasmid and an E.coli plasmid origin of replication so that it can shuttle between these two bacterial recipients. The vector, when introduced into C. trachomatis L2 under selection conditions, cures the endogenous chlamydial plasmid. We have shown that foreign promoters operate in vivo in C. trachomatis and that active β-lactamase and chloramphenicol acetyl transferase are expressed. To demonstrate the technology we have isolated chlamydial transformants that express the green fluorescent protein (GFP). As proof of principle, we have shown that manipulation of chlamydial biochemistry is possible by transformation of a plasmid-free C. trachomatis recipient strain. The acquisition of the plasmid restores the ability of the plasmid-free C. trachomatis to synthesise and accumulate glycogen within inclusions. These findings pave the way for a comprehensive genetic study on chlamydial gene function that has hitherto not been possible. Application of this technology avoids the use of therapeutic antibiotics and therefore the procedures do not require high level containment and will allow the analysis of genome function by complementation.

Introduction

C. trachomatis is a major human pathogen with a unique intracellular developmental cycle [1], [2]. This cycle begins when the extracellular, infectious form of the microorganism, the EB, binds to susceptible host cells [3], [4]. EBs are taken up into a phagocytic vesicle which is modified to become a chlamydial inclusion where individual EBs differentiate into the metabolically active, replicative form of the microorganism, the RB [5]. RBs divide by binary fission and, when 8–10 divisions have elapsed, they differentiate back into EBs that are released by cell lysis [6].

C. trachomatis has a small and highly conserved genome of some 1,000 kb [7]. In addition, most C. trachomatis isolates carry a plasmid of 7.5kb [8] which encodes eight genes. All eight genes are transcribed [9] and translated during the developmental cycle [10]. Despite the availability of the plasmid as a potential vector, the development of a simple robust genetic transformation system for the chlamydiae has remained a significant challenge [11]. The demand for such a system is evidenced by the recent development of a means to mutate the C. trachomatis chromosome [12] but to reach its full potential this requires a complementary gene transfer system. An approach using chromosomal integration was used to make recombinants in C. psittaci EBs by allelic exchange using exogenous DNA introduced by electroporation [13]. This was limited to the 16S rDNA region and only allowed integration of a short 1 kb marker at extremely low efficiencies. C. psittaci requires high levels of containment and therefore is not readily available to the wider research community. Electroporation of EBs was used in 1994 in an attempt to transform C. trachomatis with an episomal vector based on the chlamydial plasmid [14]. No stable transformants were isolated although inclusions were present for up to four passages under chloramphenicol selection. There have been reports of plasmid free strains of C. trachomatis but only three viable, naturally occurring plasmid-free isolates of C. trachomatis have been described [15]–[17], thus most C. trachomatis isolates carry the 7.5 kbp plasmid, its biological function is unknown although its presence has for a long time been linked to the ability of C. trachomatis to synthesise glycogen [18]. We tried unsuccessfully to cure a lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) strain of C. trachomatis L2 of its plasmid [19] but recently curing of the plasmid from a genital tract C. trachomatis D has been described [20]. This plasmid-cured strain and the naturally occurring plasmid-free strains do not stain for glycogen [21]; the plasmid does not encode glycogen synthesis genes thus the phenomenon involves complex interaction(s) between the plasmid and the chlamydial genome to elicit the glycogen staining phenotype [22]. However, formal proof associating this property with the plasmid alone is necessary but can only be achieved by re-introducing the plasmid into a plasmid-free strain. This has not been possible because of the absence of a means to genetically manipulate C. trachomatis.

We report here the first successful development of a simple, robust, reproducible plasmid-based genetic transformation system for C. trachomatis using penicillin selection and calcium chloride (CaCl2) treatment of EBs to render them competent. Penicillin causes C. trachomatis to enter a persistent non-infectious state [6], [23]–[25]; therefore our experimental plan was to select genetically stable, penicillin-resistant transformants by recovery of Chlamydiae from penicillin-arrested division. To demonstrate the effectiveness and reproducibility of the procedure, we have engineered a strain of C. trachomatis that is penicillin resistant and that expresses GFP. We have also proven the role of the chlamydial plasmid in glycogen biosynthesis by re-introducing the plasmid into a C. trachomatis strain that is plasmid-free (C. trachomatis L2 (25667R)) [15]. We have demonstrated that as a result of this genetic transformation the previously plasmid-free strain C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) acquired the ability to synthesize and accumulate glycogen within inclusions.

Results/Discussion

Our primary aim was to develop a transformation protocol using a chlamydial plasmid-based shuttle vector. Our scientific aim was to determine whether glycogen biosynthesis, a distinctive characteristic of C. trachomatis which has been linked to the presence of the plasmid, could be restored in a plasmid-free, glycogen-free variant of C. trachomatis, by re-introducing the plasmid DNA.

Plasmid shuttle vector - design and choice of selectable marker(s)

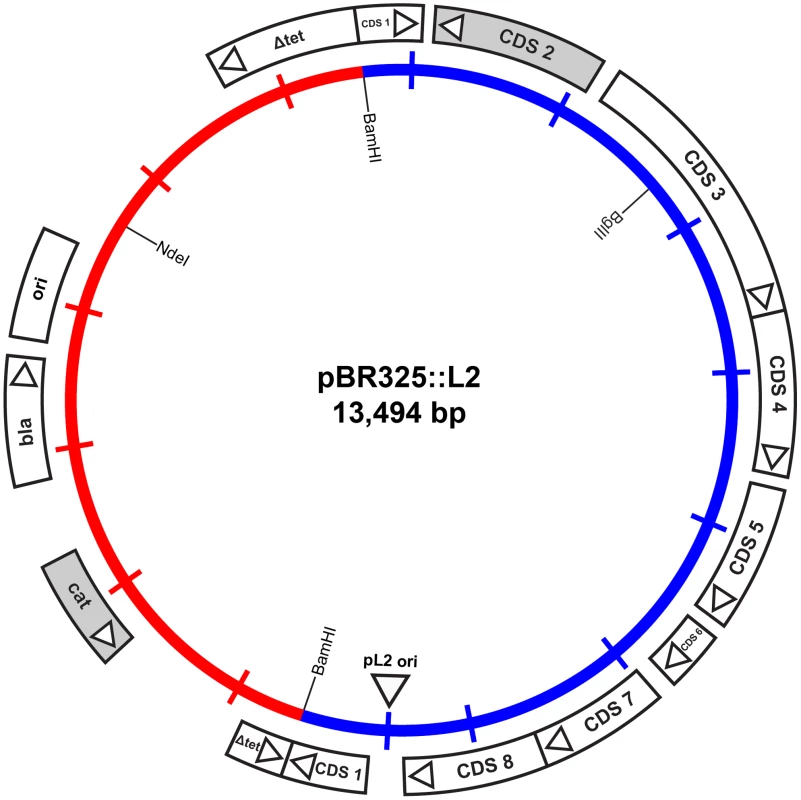

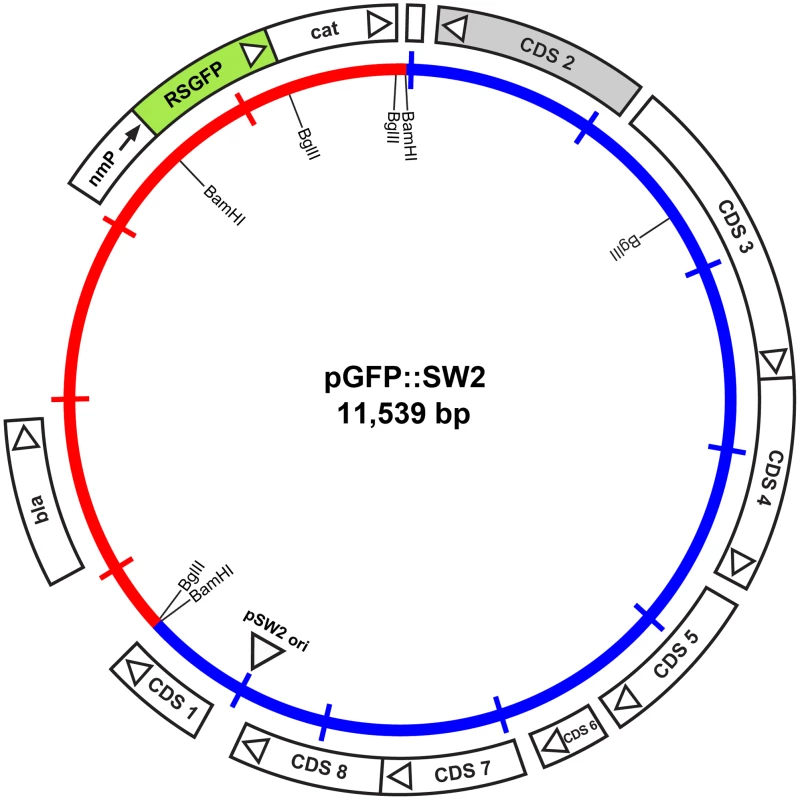

To enable the selection of transformants for plasmid vectors, antibiotic resistance markers offer the most attractive choices. There are a range of single gene antibiotic resistance markers that are safely used worldwide for the routine and stable transformation of bacteria. These markers are popular because it is not possible to generate transformants unless an intact gene is acquired thus eliminating the problem of background resistance through spontaneous mutation. The markers used in routine selection of bacterial transformants include tetracycline resistance, chloramphenicol resistance and β-lactamase (penicillin/ampicillin resistance) [26]. Tetracycline resistance markers have been used in allelic transfer experiments for chlamydiae [27], but tetracycline is a controversial choice because it is used routinely to treat C. trachomatis infections [28]. C. trachomatis is sensitive to chloramphenicol but it is difficult to reproduce a minimal inhibitory assay as this antibiotic causes mitochondrial stress [29] limiting chlamydial growth and is thus not so useful for selection and continuous passaging of transformants. By contrast, the effects of penicillin on C. trachomatis are well studied [6], [25], it is bacteriostatic giving a resistant phenotype and penicillin is not recommended for the treatment of chlamydial infections [30]. Following penicillin treatment, the developmental cycle is slowed and the transition to EBs ceases with the formation of giant, aberrant RBs. The normal developmental cycle resumes upon removal of penicillin (at low concentrations) from the culture media and the resultant normal chlamydial inclusions are easily detectable by phase contrast microscopy [6]. We reasoned that rescue of infectious C. trachomatis from the penicillin-induced aberrant developmental cycle through transformation and β-lactamase expression would present a distinctive phenotype that could be easily selected microscopically and transformants could be recovered under penicillin selection. We tested a range of penicillin concentrations on the growth of normal C. trachomatis L2 and determined that 10 units/ml of penicillin was a suitable concentration for inhibition of C. trachomatis and hence this was the antibiotic concentration chosen for the C. trachomatis transformation work. Penicillin resistance was introduced into a C. trachomatis plasmid (pL2) by ligating a pBR325 plasmid and the pL2 plasmid (pBR325::L2). This was a simple, standard recombinant plasmid from our collection that had an intact β-lactamase gene and the complete chlamydial plasmid. Ligation into the Bam HI site of pBR325 plasmid created an insertional inactivation of the tet gene but still conferred penicillin and chloramphenicol resistance. The Bam HI site in the pL2 plasmid is located in coding sequence 1 (CDS1), a region which is susceptible to mutation/deletion without affecting plasmid stability [8], [19]. The plasmid map is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Map of the shuttle vector pBR325::L2.

The inner circle represents the plasmid pL2 from C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu (blue) and the vector sequences of pBR325 (red). The coding sequences and their direction of transcription are represented by the boxes of the outer circle. The β-lactamase (bla), chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (cat) and inactivated tetracycline resistance gene (Δtet) are as indicated, as are key restriction endonuclease cleavage sites. Strains of C. trachomatis

We chose the well-studied, laboratory-adapted strain C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu (ATCC VR902B) as the recipient strain because we already had a full complement of biological and genetic information for this strain (the complete genome sequence and defined proteome) [31], [32]. The vector with which we started the work contained the cognate pL2 plasmid cloned from C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu genomic DNA [33]. Furthermore, the LGV strains [34] that we used: C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu and (later) the plasmid-free C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) have relatively low particle to infectivity ratios [35] and do not need centrifugation to achieve efficient cell infection, thus these bacteria have a higher viability than standard genital tract isolates and have a faster developmental cycle giving a quicker turn around of experiments [4].

Transformation of C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu

We wanted to investigate whether it was possible to transform EBs using a simple standard protocol and a defined buffer that could be reproduced in any laboratory. Standard bacterial transformations are based on the primary observation that bacteria treated with ice cold solutions of CaCl2 followed by brief heating can be induced to take up foreign DNA [36]. Therefore we initially used such a protocol, developed for E. coli, to attempt transformation of gradient purified C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu EBs and selected transformants with 10 units/ml penicillin. However, we found that heat shock was not necessary and that the whole transformation protocol could be achieved at room temperature (RT) simply by gently mixing EBs, vector DNA and McCoy cells in CaCl2/Tris buffer. This protocol is described in the Materials and Methods and the selection procedure is described in Table S1. For selection our reasoning was to allow recovery of transformants, without penicillin selection in the first round of infection (developmental cycle) and then apply selection with penicillin initially at 10 units/ml (10 units = 6 µg penicillin). After three rounds of selection, all the untransformed penicillin-inhibited C. trachomatis were lost and the culture was overgrown by penicillin-resistant transformants that appeared to grow with similar kinetics and inclusion morphology as the parental strain. It was possible to increase the concentration of penicillin to 20 and 100 units/ml at passages 3 and 4 to speed up the selection process. In each experiment regular observation of the cultures under phase contrast microscopy allows some flexibility in deciding precisely when the next passage is needed, taking into account the size, form and number of inclusion bodies observed at each stage.

The frequency of transformation, defined as the proportion of EBs or trypsinised cells receiving the shuttle vector DNA and still keeping the ability to start chlamydial proliferation, is a parameter that cannot be measured. The efficiency of recovery is dependent on the percentage of the transformed EBs present in the total population of EBs after each stage of selection. Each passage is performed by infecting cell cultures with cell lysates from the previous passage (see Materials and Methods, and Table S1). Following lysis of the McCoy cells, the untransformed Chlamydia, present as non-infectious RBs, fail to passage. Thus only transformed EBs and a diminishing number of carry-over untransformed EBs infect new host cells. The recovery increases with each passage until only transformed Chlamydia remain.

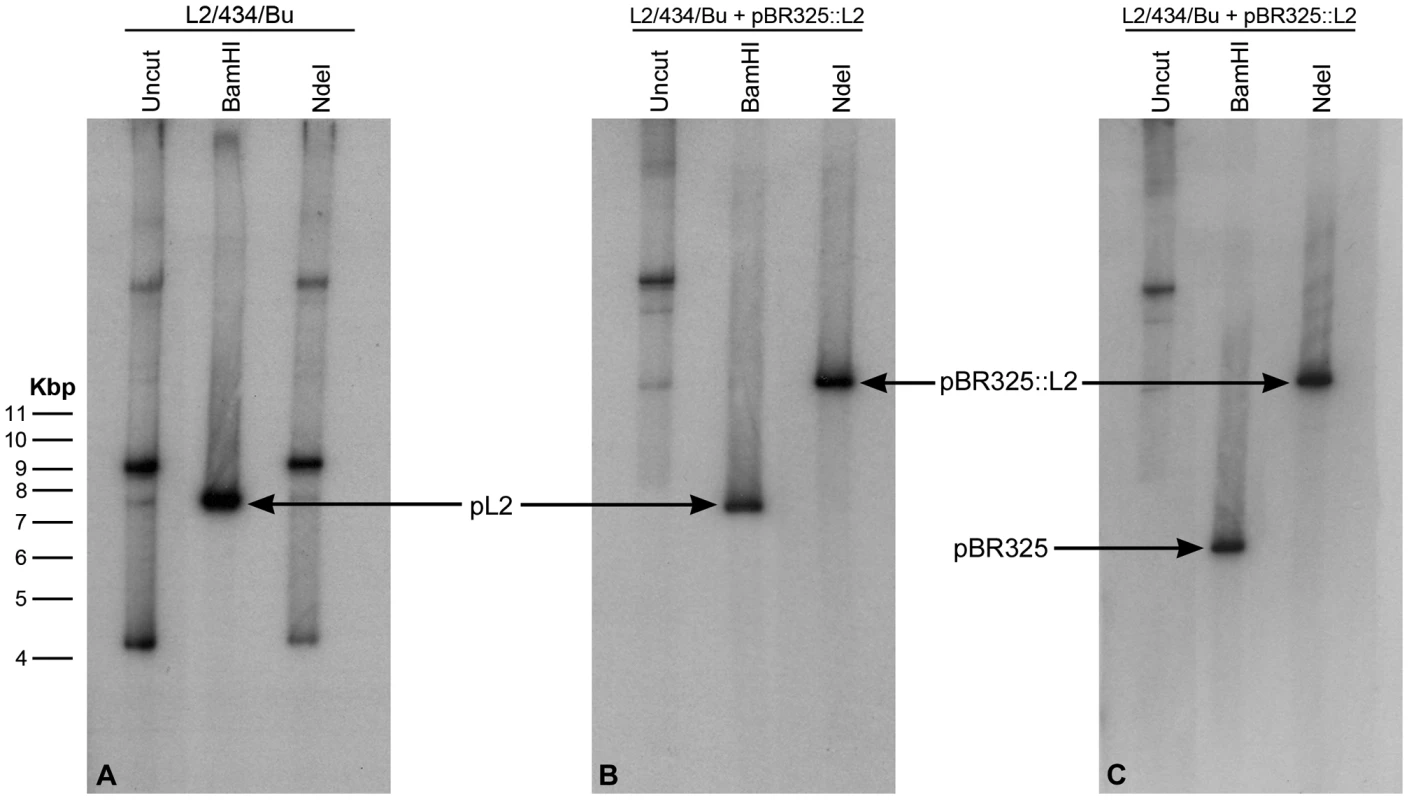

The pBR325::L2 transformed C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu strain was plaque purified (x3), expanded, and EBs and RBs were purified for detailed characterization. Southern blotting of chromosomal DNA purified from EBs with a vector probe (β-lactamase gene) and a chlamydial plasmid probe proved that transformation had occurred and revealed no changes in either the E. coli vector (pBR325) or the L2 plasmid (pL2), although by these passages the endogenous chlamydial plasmid had been eliminated from the transformed strain (Figure 2). There was no evidence for recombination/integration of the transforming plasmid with the recipient C. trachomatis chromosomal DNA.

Fig. 2. Southern blot of C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu transformed by plasmid pBR325::L2.

Equal amounts of C. trachomatis DNA were loaded in each gel track, the DNA is uncut (track 1) or has been digested to completion with Bam HI (track 2) or Nde I (track 3). (A) DNA from wild type (untransformed C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu) was probed with the complete plasmid sequence pL2. (B) DNA from the transformed strain also probed with pL2. (C) DNA from the transformed strain probed with the complete β-lactamase gene sequence (generated by PCR). The wild type pL2 plasmid (7.5 kb) carries a unique Bam HI restriction site (which is used as the cloning site for insertion into the vector pBR325) but no Nde I site. The bands in tracks 1 and 3 in panel A represent various forms of the plasmid pL2. The recombinant plasmid pBR325::L2 is ∼13.5 kb, thus digestion with Bam HI releases the pBR325 vector (6 Kb – hybridizing to the bla probe in (C) and the chlamydial plasmid pL2 (7.5 kb – hybridizing to pL2 probe in panel B). The recombinant plasmid (pBR325::L2) carries a unique Nde I site (located in pBR325) and digestion with this enzyme linearises the vector at 13.5 kb; this band is detected with both hybridization probes (track 3 panels B and C). Properties of pBR325::L2 transformed C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu

The copy number of pBR325::L2 was similar to that of the endogenous pL2 as accurately measured by qPCR (Figure S1).

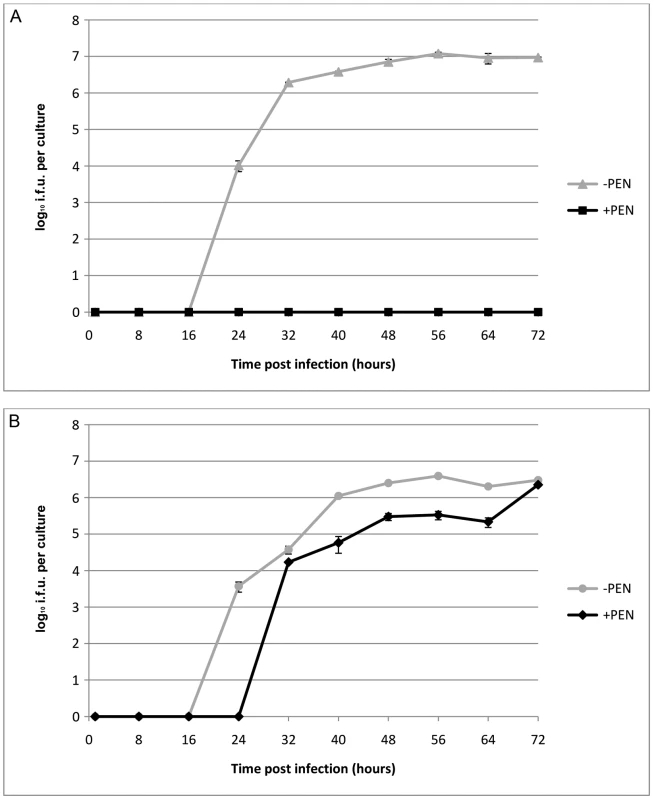

To investigate the effects of transformation by plasmid pBR325::L2 on the strain C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu, we compared the growth characteristics of the parental strain and the transformed strain with or without penicillin selection. These data are summarized in Figure 3 and clearly show that the parental strain (L2) grows well in McCoy cells, as previously demonstrated, and there was no recovery of infectious EBs in the presence of penicillin when it was added at 10 units/ml from the start of the developmental cycle.

Fig. 3. Growth characteristics of C. trachomatis L2 and C. trachomatis L2 transformed by pBR325::L2.

(A) C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu, (B) C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu transformed by shuttle vector pBR325::L2. McCoy cells in a 24 well tissue culture tray grown to confluence were infected with C. trachomatis at MOI = 1 and were cultured without (-PEN) and with (+PEN) penicillin G at 10 units/ml. The yield of C. trachomatis (IFU) per culture or single well is shown on the y – axis and time of sampling post infection is shown on the x –axis. The experiments were repeated in quadruplicate and standard error bars are shown for each sample point. By contrast, the transformed strain grew in both the presence (10 units/ml) and absence of penicillin (up to 8 passages) giving similar recoveries of infectious EBs at the end of developmental cycle. Nevertheless the presence of a large transforming plasmid (pBR325::L2) has a measurable effect and the developmental cycle was lengthened and the yield slightly reduced compared to the untransformed C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu. Transmission electron microscopy of infected cells at late stages of the developmental cycles show no obvious phenotypic differences for transformed or untransformed C. trachomatis in the absence of penicillin but in the presence of penicillin untransformed C. trachomatis produced large aberrant RBs whereas transformed C. trachomatis inclusions appeared normal (Figure S2).

The vector was recovered from pBR325::L2 - transformed C. trachomatis L2 by genomic DNA preparation and analysed by direct sequencing. These data showed no evidence for the presence of the original pL2 and also confirmed that there were no rearrangements or recombination events with pL2 or within the pBR325::L2 vector, although there were a few base changes from the sequences deposited in the database for the original pBR325 vector (Figure S3). These were attributable to errors in the original sequencing and annotation rather than adaptive mutations or subsequent transformation of the DNA in to E. coli. Analysis of multiple colonies carrying the recovered pBR325::L2 from E. coli by mini-plasmid preparation and restriction digestion showed they were all clonal and appeared to be unchanged from the transforming vector. One of these recovered plasmids was also sequenced and was identical to the sequence obtained direct from the transformed C. trachomatis.

Immunoblotting of purified EBs and RBs with commercially available antibodies (Figure S4) showed the presence of both β-lactamase and chloramphenicol acetyl transferase enzymes consistent with the observation that pBR325::L2 - transformed C. trachomatis L2 was, in contrast to the untransformed C. trachomatis L2, resistant to penicillin up to 100 units/ml and able to grow in medium containing chloramphenicol concentrations up to 3 µg/ml (data not shown).

Interestingly, both the processed and mature forms of β-lactamase were detectable by immunoblotting in EBs showing that the signal peptide [37] was functional in C. trachomatis and the pre-protein was cleaved completely in RBs (Figure S4A). Chloramphenicol acetyl transferase levels (as assessed by immunoblot) were the same in both RBs and EBs (Figure S4B).

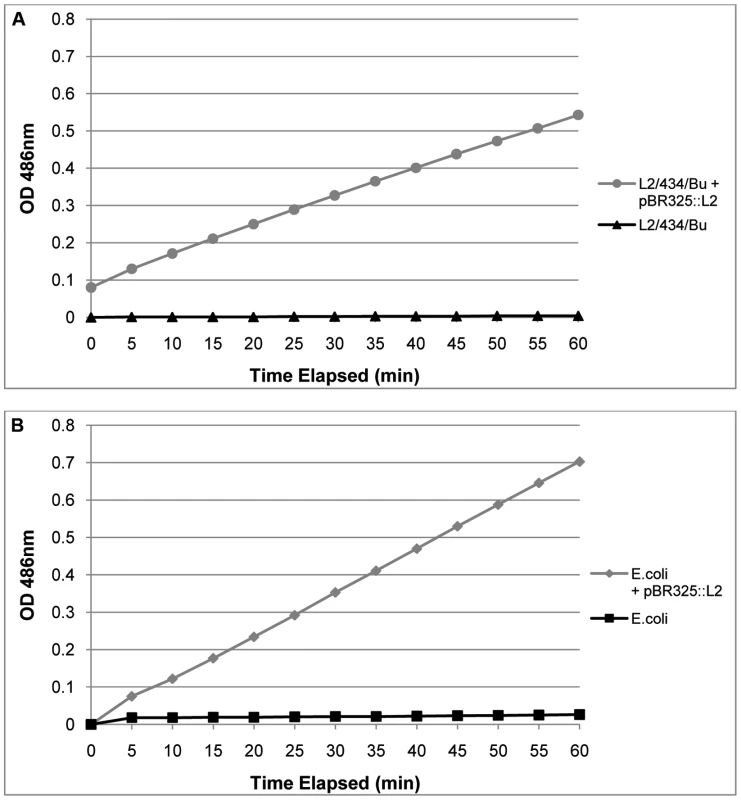

The transformed C. trachomatis L2 grew under penicillin selection and whilst the presence of β-lactamase, as shown by Western blotting, indicated that resistance to penicillin is likely through the mechanism of action of this enzyme, it did not prove that the enzyme is active. Thus to prove formally that the resistance to penicillin was indeed due to acquisition of an active β-lactamase, purified RBs (the actively growing form of C. trachomatis) were assayed for β-lactamase activity. Figure 4 shows that pBR325::L2 - transformed C. trachomatis RBs have β-lactamase activity whereas RBs from the untransformed parental strain do not.

Fig. 4. Purified, transformed RBs have β – lactamase activity.

In Panel A equal amounts of purified RBs (measured by qPCR of the genome) from transformed C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu and the wild–type parental C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu were assayed for β – lactamase activity. In Panel B equal amounts of E. coli and E. coli transformed with pBR325::L2 were used as controls to verify the assay. Hydrolysis of Nitrocefin is measured in pH 7.0 buffer by absorbance at 486 nm over 60 min. Nitrocefin is a chromogenic β – lactamase substrate. These results, taken together, established that pBR325::L2 could be selected from a background of untransformed C. trachomatis and this vector could also replicate in E. coli, therefore providing the basis of a functional shuttle vector. They showed proof of principle that the functions for retaining and replicating the plasmid in C. trachomatis were unaffected in the shuttle vector and we have established that standard E. coli promoters for both β-lactamase and chloramphenicol acetyl transferase operate in C. trachomatis. Further, the β-lactamase is active and the type 1 signal peptidase mechanism from C. trachomatis [38] is able to cleave the β-lactamase precursor to a mature form of the correct molecular weight in RBs, the actively growing form of the micro-organism.

In our experiments deriving a transformation frequency as a percentage of EBs receiving vector DNA is not a relevant measure and we have no means of measuring how many survive selection in the first round of culture. We considered it might be possible to do this if we had a marker such as green fluorescence that we could use to identify live transformed Chlamydia.

Expression of the green fluorescent protein in C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu

To show that the transformants obtained in the first series of experiments were useful for general application and not just the outcome from a serendipitous choice of a single, vector configuration (pBR325::L2) it was essential to repeat the work but with more than one (and different) marker. For this purpose we chose the mutated plasmid from the Swedish new variant which has a characteristic 377 bp deletion in CDS1 and a 44 bp duplication in the 5′ terminus of CDS3 [8]. This plasmid was cloned into an E. coli vector able to express the GFP. The complete plasmid map of the shuttle vector carrying the mutated plasmid from SW2 is shown in Figure 5.

Fig. 5. Map of the plasmid vector pGFP::SW2.

The inner circle represents the plasmid pSW2 from C. trachomatis SW2 (blue) and the vector sequences (red). The coding sequences and their direction of transcription are represented by the boxes of the outer circle. Some key restriction endonuclease cleavage sites used in the construction of this vector are indicated on the inner circle. The cat gene is fused with RSGFP (shaded green) and expressed by a promoter derived from Neisseria meningitidis (nmP); the direction of transcription of this promoter is designated by the arrow. Plasmid pGFP::SW2 contains a β-lactamase gene together with a red-shifted green fluorescent protein gene fused to the chloramphenicol acetyl transferase gene under control of a neisserial promoter. The map of the original plasmid pRSGFPCAT that provided the fused rsgfp-cat cassette including the neisserial promoter is shown in Figure S5.

E. coli cells transformed with pRSGFPCAT are resistant to penicillin and chloramphenicol and fluoresce green under blue illumination (data not shown).

The plasmids and DNA used to make this final shuttle vector (pGFP::SW2) are summarized in Figure S6. The complete sequence and list of features for pGFP::SW2 are summarized in Figure S7.

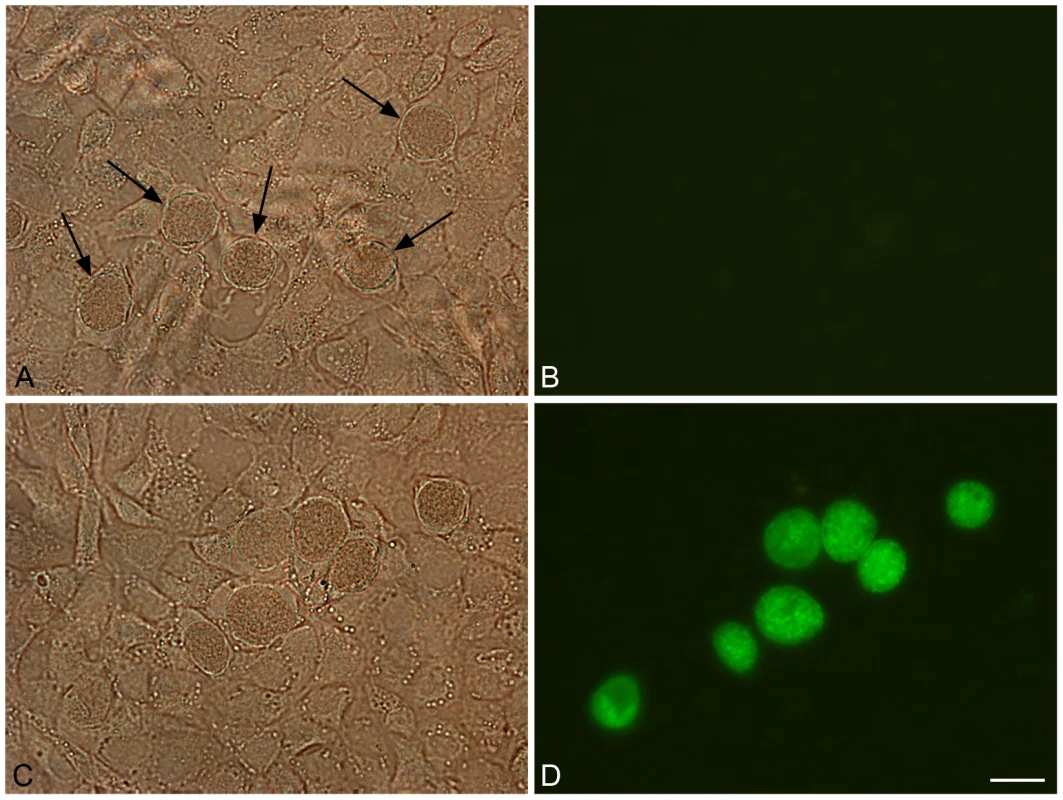

Transformation of C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu with pGFP::SW2 was successfully achieved on six occasions and yielded a penicillin-resistant strain that had green fluorescent inclusions (Figure 6). Green fluorescent inclusions became visible at 24 h post infection, once the transformants had been selected by multiple passages; however, we were unable to observe green fluorescent inclusions in the first developmental cycle post-transformation.

Fig. 6. Green fluorescent inclusions in McCoy cells infected with C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu transformed with pGFP::SW2.

Untransformed C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu (control) and C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu transformed by pGFP::SW2 were grown on coverslips for two days before fixing in 4% formaldehyde (diluted in DPBS). Panel A shows untransformed C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu under white light (arrows indicate inclusions). Panel B is the same image under blue light. Panel C shows C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu transformed with plasmid pGFP::SW2 under white light, and panel D is the same field under blue light. The scale bar represents 20 µm. The green fluorescent protein is expressed as a fusion protein with the chloramphencol acetyl transferase (GFPCAT). To show that the fluorescence observed in inclusions was derived from the GFPCAT fusion protein, transformed Chlamydia were immunoblotted with anti-GFP monoclonal antibodies as shown in Figure S8.

Transformation of plasmid-free C. trachomatis with pGFP::SW2 restores the ability to biosynthesise glycogen

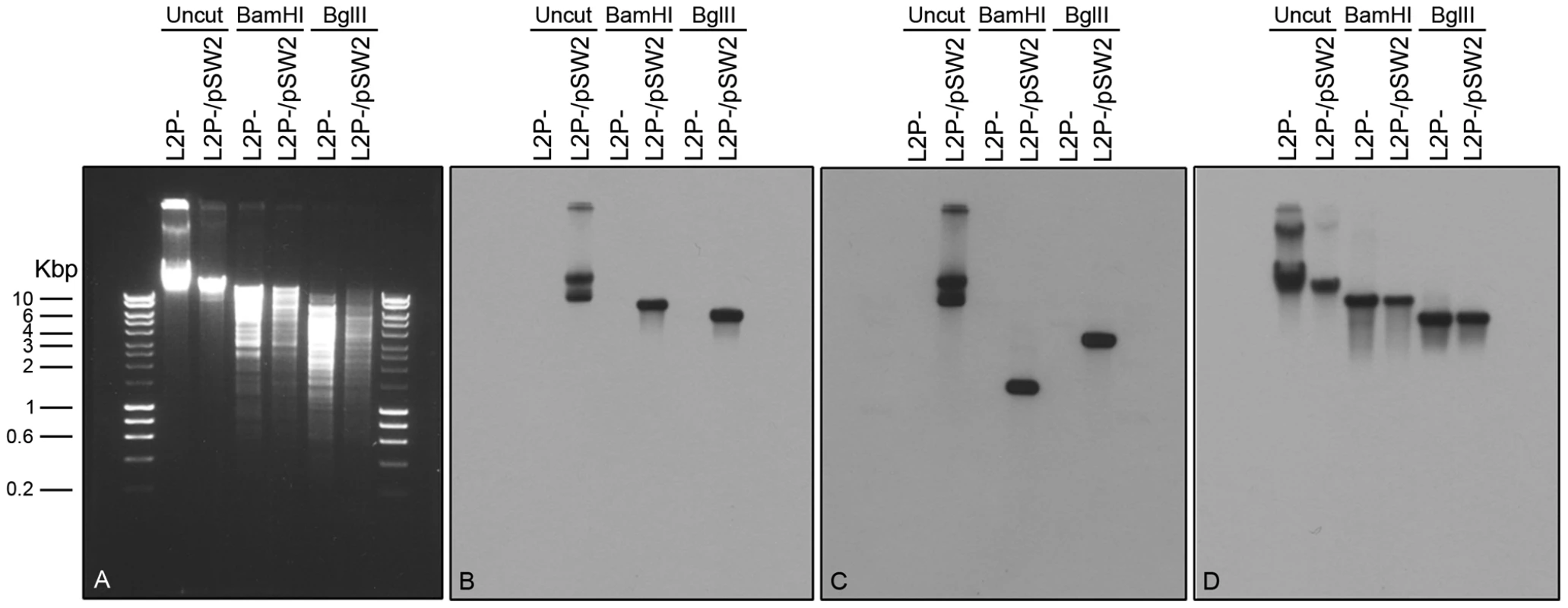

The ability to stain for the presence of glycogen in chlamydial inclusions is a property that has been linked to the presence of the plasmid although it has not been possible to prove formally the association as no system has previously existed for the introduction of plasmids into C. trachomatis [21]. The C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) strain is plasmid-free and not able to accumulate glycogen. We were unsure whether it would be possible to transform this strain as it was plasmid-free and may have lost the ability to retain the plasmid. Nevertheless, we attempted transformation of this C. trachomatis L2 strain with the vector pGFP::SW2 and obtained stable penicillin-resistant transformants that had green fluorescent inclusions. However, transformation of C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) strain with the basic cloning plasmid pSP73 alone did not yield transformants showing that the chlamydial plasmid (pSW2) was necessary to provide the replication functions of the shuttle vector pGFP::SW2 in C. trachomatis [8], [19]. We were able to recover the intact pGFP::SW2 vector from transformed C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) by genomic DNA preparation and re-transform the DNA into E. coli. Southern blotting of DNA extracted from transformed plasmid-free C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) confirmed the presence of pGFP::SW2 (Figure 7) and proved that transformation had occurred.

Fig. 7. Southern blot of C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) transformed by plasmid pGFP::SW2.

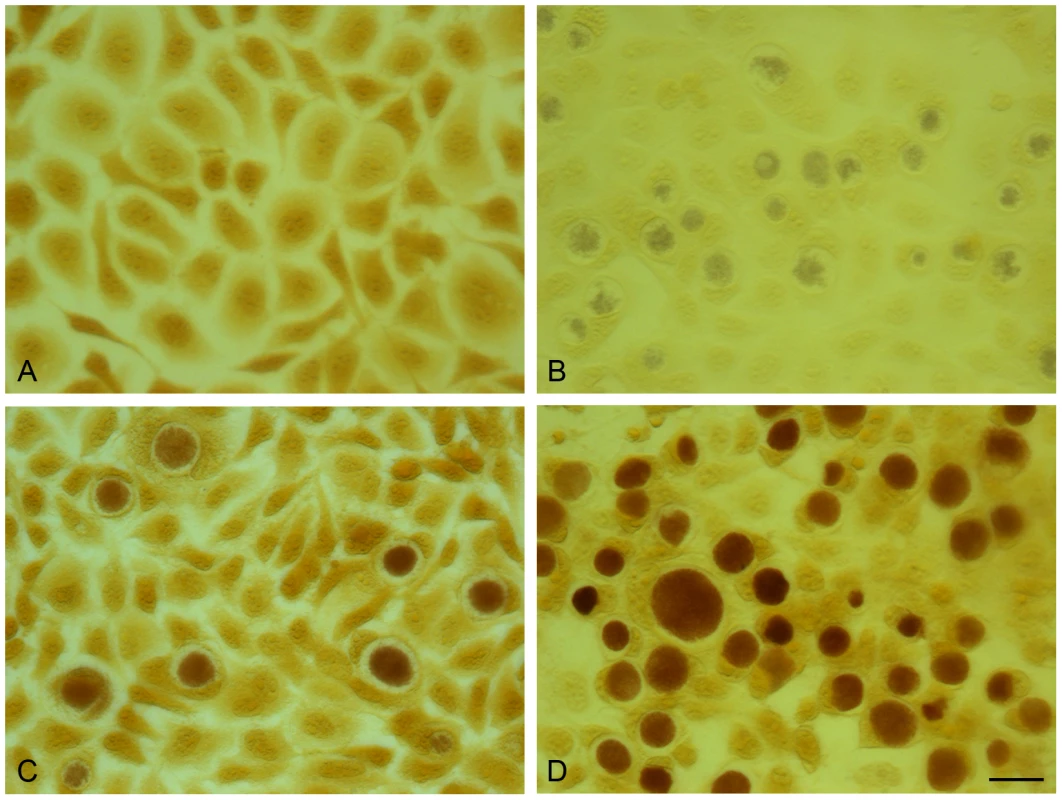

Southern hybridization analyses of plasmid-free C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) (abbreviated as L2P-) and C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) transformed with plasmid pGFP::SW2 (in short L2P-/pSW2). Six chlamydial genomic DNA samples were loaded on the gel in pairs together with HyperLadder I (5 µl) from BIOLINE (Cat No. BIO-33025). The agarose gel image was taken before DNA transfer (A). The DNA blot was first hybridized with the pSW2 probe (B), and then stripped and re-probed with the GFP probe (C) or an ompA probe (D). Bam HI digestion of pGFP::SW2 created 3 fragments: 7169 bp (containing pSW2 probe sequence), 2925 bp and 1445 bp (containing GFP probe sequence). Bgl II digestion of pGFP::SW2 created 4 fragments: 5555 bp (containing the pSW2 probe sequence), 3625 bp (containing the GFP probe sequence), 1693 bp and 666 bp. When the C. trachomatis L2 genomic DNA (similar to L2P-) was digested with Bam HI or Bgl II, the fragment containing ompA sequence was 8837 bp (Bam HI digestion) or 5518 bp (Bgl II digestion). Southern hybridization using the pSW2 probe or the GFP probe showed hybridization signals at expected positions in all L2P-/pGFP::SW2 samples (uncut or digested); whilst no hybridization signal, as expected, was detected in all L2P- samples (uncut or digested) (B) and (C). Southern hybridization using the ompA probe showed that the hybridization signals were similar in L2P- and L2P-/pGFP::SW2 samples (uncut or digested) (D). The pGFP::SW2-transformed C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) had inclusions which stained positive for glycogen (Figure 8). This observation confirms that glycogen biosynthesis is a trait that is dependent on the presence of the chlamydial plasmid. Every inclusion from the pGFP::SW2-transformed C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) stained for glycogen, demonstrating stable transformation at the individual level as well as the population level (as shown by the Southern blots).

Fig. 8. Acquisition of the plasmid pGFP::SW2 restores the ability of plasmid-free C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) to synthesize glycogen.

The presence of glycogen within inclusions was detected by iodine staining of cells on coverslips. (A) McCoy cells control, (B) C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) in McCoy cells, (C) C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu in McCoy cells, (D) pGFP::SW2- transformed C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) in McCoy cells. The scale bar represents 20 µm. Conclusions

-

We have developed a simple and reproducible genetic transformation protocol for C. trachomatis based on calcium chloride treatment of EBs.

-

We have designed a shuttle vector based on the 7.5 kb chlamydial plasmid and the E. coli plasmid pBR325. This vector replicates in both C. trachomatis and E. coli and selection is based on penicillin resistance.

-

C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu transformed by the shuttle vector pBR325::L2 shows similar growth characteristics and inclusion formation as the untransformed strain.

-

We have developed a second smaller shuttle vector pGFP::SW2 that conveys penicillin resistance through beta-lactamase expression and that also expresses the GFP.

-

C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu transformed with pGFP::SW2 produces green fluorescent inclusions.

-

Transformation of a plasmid-free strain of C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) with pGFP::SW2 generates green fluorescent inclusions and also restores the glycogen staining phenotype confirming that this property is a plasmid-dependent property.

-

The development of a simple and reproducible transformation method will open the way to a better understanding of chlamydial genetics and could lead to the development of new approaches to chlamydial vaccines and therapeutic interventions aimed at modulating chlamydial pathogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Microscopy

Cells in culture and cells infected with C. trachomatis L2 were routinely visualized by phase contrast microscopy using a Nikon eclipse TS100 inverted microscope with fluorescence accessories. Fluorescence images were captured using a Leica DMRB microscope to visualize the expression of GFP in McCoy cells infected by pGFP::SW2-transformed C. trachomatis L2. Counting of inclusion forming units (IFU) to quantify chlamydial infectivity was performed on serial dilutions of C. trachomatis L2 in monolayers of McCoy cells grown in 96 well trays. For this assay inclusions were immunostained as previously described for C. abortus [39]. For transmission EM studies McCoy cells infected with C. trachomatis L2 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 were grown in 6 well trays and 48 h post infection were fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1% cacodylate buffer, processed as previously described [40] and photographed using an Hitachi H7000 electron microscope.

E. coli strains, recombinant plasmids and genetic manipulations

E. coli strain DH5α [41], [42] and its derivative strain E. coli ‘Top10’ from Invitrogen were used for the basic cloning and construction of vectors pRSGFPCAT and pGFP::SW2. The vector pBR325::L2 was constructed by ligation of pL2 cleaved by Bam HI from plasmid PDCPB [33] (this vector is equivalent to pBR322::L2) into Bam HI cleaved pBR325 (GenBank: L08855.1), this cloning was performed in E. coli strain HB101. The original preparation of the plasmid pBR325::L2 DNA (used to transform C. trachomatis L2 EBs) was performed in E. coli strain HB101, but all subsequent plasmid manipulations for transformation were performed using E. coli GM 2163. This strain is mutated for Dam, Dcm and Mcr methylation systems and was available from New England Biolabs (Cat. no. #E4105S). Plasmid pGFP::SW2 (Figure 5) was constructed from the C. trachomatis SW2 plasmid pSW2, pSP73 and pRSGFPCAT. The complete cloning strategy is summarised in Figure S6. Plasmid pRSGFPCAT is a small in-house vector based on a pUC origin of replication and carrying the cat gene fused to RSGFP and under the control of a neisserial promoter that is constitutively expressed in E. coli (refer to Figure S5 for sequence details). Briefly, the Bam HI fragment of pSW2 (GenBank: FM865439.1 - obtained by gel extraction from a C. trachomatis SW2 total genomic DNA Bam HI digestion) (Figure S6 panel A) was cloned into the unique Bam HI site of plasmid pSP73 (Figure S6 panel B) to give plasmid pSP73::SW2 (Figure S6 panel C). The Pst I/Sal I fragment of pRSGFPCAT (Figure S6 panel D) was then cloned into Pst I/Sal I backbone of pSP73 allowing selection of ampicillin resistant, chloramphenicol resistant green fluorescent colonies.

Ethics statement

All genetic manipulations and containment work was approved under the UK Health and Safety Executive Genetically Modified Organisms (contained use) regulations 2000 notification no GM57,10.1 entitled ‘Genetic transformation of Chlamydiae’.

Cell culture and propagation of C. trachomatis strains

McCoy cells were used for propagation of C. trachomatis and for the transformation studies. Two strains of C. trachomatis were used as recipient strains for transformation in this study: C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu (ATCC VR-902B) which carries a 7.5 kb plasmid (pL2) and C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) which has no plasmid [15]. Both strains were confirmed as pure, clonal isolates by 3 rounds of plaque purification and, together with the McCoy cells, were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination by fluorescence microscopy using Hoechst no. 33258 staining and by VenorGem Mycoplasma PCR detection (Minerva Biolabs, Berlin, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The McCoy cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagles' medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Cell concentrations were determined by staining with Trypan Blue and counting in a haemocytometer. Cells were infected with C. trachomatis by overlay of the inoculum for 1 h in medium containing cycloheximide (1 µg/ml) and gentamicin (25 µg/ml). On completion of the developmental cycle and immediately prior to host cell lysis, infected monolayers were detached with trypsin/EDTA buffer (from Invitrogen, Cat. # 25300-054) and EBs were harvested in DMEM containing 10% FCS at 3,000 g for 10 min. The C. trachomatis-infected cell pellet was suspended in a solution of 10% PBS in water and homogenized in a Dounce homogenizer to break open the cells and release the EBs. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 250 g for 5 min and the supernatant containing partially purified EBs was mixed with an equal volume of phosphate/sucrose buffer (16 mM Na2HPO4 pH 7.1 and 0.4 M sucrose, abbreviated as 4SP), and was stored at −80°C.

Plaque assay for infectivity assay and for clonal purification of EBs and RBs

The C. trachomatis strains were plaque purified as previously described [31], [43]. Briefly a single plaque was picked, cultured and purified to clonality by two further rounds of plaquing. The plaque-purified Chlamydia were then used to make stock preparations. Large scale cultures were prepared for the production of EBs and RBs which were purified by two cycles of Urografin (Schering Healthcare, UK) density gradient centrifugation as previously described [31].

Genetic transformation of C. trachomatis

A simple protocol was developed where C. trachomatis L2 EBs were first mixed with plasmid DNA and then used to infect freshly trypsinised McCoy cells (MOI = 2.5). The preparation of EBs, vector DNA and cells followed by the transformation protocol is described in detail below.

1. Preparation of EBs for transformation: McCoy cells were grown in 6× T75 flasks, and infected with C. trachomatis L2 in fresh medium (DMEM + 10%FCS) containing 1 µg/ml of cycloheximide, and grown in 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 2 days at an MOI = 2 giving ∼90% cells infected. The cells were bulk harvested using cell scrapers, and then spun at 3500 rpm for 10 min. The cell pellet was saved, resuspended in 1 ml of cold 10% PBS, and transferred into a bijoux tube with glass beads. The cells were then lysed by vortexing for 1 min. The cell debris was removed by spinning at 1000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was saved (∼1 ml) and mixed with 1 ml of 4SP. The inocula were divided into 100 µl aliquots and stored at −80°C.

2. The vector DNA was extracted from overnight E. coli cultures (GM2163 strain) using the PureYield Plasmid Midiprep System (Promega Cat. No. A2492). The quality and the concentration of the DNA were evaluated by agarose gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (from Thermo Scientific). The DNA was used at concentration ∼0.5–1 µg/µl.

3. McCoy cells were prepared for transformation when cells were ∼70% confluent in a T75 flask, the medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with 5 ml Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS) (from Invitrogen, Cat. # 14190-094). Then 2 ml Trypsin/EDTA buffer was added to cover the cells. Trypsinisation was allowed to proceed at RT for 5 min and when the cells were released from the flask, 10 ml of medium was added with a pipette, and the medium was washed up and down with the pipette to release the remaining cells and to break up clumps. The cells were transferred to a plastic universal and spun in a bench top centrifuge (Beckman Coulter Allegra X-15R) at 1000 rpm for 5 min, the medium was removed and the pellet briefly rinsed and then resuspended in 5 ml DPBS and pelleted again at 1000 rpm for 5 min. The DPBS buffer was discarded and cells resuspended in CaCl2 buffer for transformation.

4. Transformation is performed as follows: 10 µl Chlamydia EBs (1×107 IFU) and 10 µl plasmid DNA (6 µg) were mixed in a total volume of 200 µl CaCl2 buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.4 and 50 mM CaCl2) and then incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Freshly trypsinised McCoy cells (4×106), resuspended in 200 µl CaCl2 buffer were then added to the plasmid/EB mix and incubated for a further 20 min at room temperature with occasional mixing. 100 µl of this mixture was then added to a single well in a six well tray together with 2 ml of pre-warmed DMEM + 10% FCS. The cells were allowed to settle and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 days without cycloheximide or penicillin. The infected cells from each well were harvested individually by scraping cells with a 1 ml filter tip and then lysed by vortexing with glass beads. The cell debris was removed by spinning at 1000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was saved (∼2 ml) and mixed with 2 ml of 4SP and stored in −80°C freezer (this was called T0).

5. Passage and selection. The T0 inocula were used to infect McCoy cells in a T75 flask (passage 1). Potential transformants were grown in medium containing cycloheximide (1 µg/ml) and selected with 10 units/ml of penicillin G (Sigma product no. P3032). Under these conditions, most inclusions were large and vacuolar as previously described [6]. Chlamydia were grown for two days before harvesting as ‘T1’ and this was used to infect McCoy cells as passage 2 in a T25 flask and selected with 10 units/ml of penicillin. Passaging was continued for 2–4 times in T25 flasks with 10 units/ml of penicillin until only normal inclusions were recovered. The passage and selection procedures are summarized in Table S1.

Genomic DNA extraction from C. trachomatis strains

The genomic DNA of C. trachomatis L2, C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) and pBR325::L2 - transformed C. trachomatis L2 (or L2, L2P - and L2/pBR325::L2 in short) were extracted from Chlamydia inocula (collected from infected McCoy cells in T75 flasks) using Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Cat. No. A1120). The genomic DNA of pGFP::SW2 - transformed C. trachomatis L2 and transformed C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) (or L2/pGFP::SW2 and L2P-/pGFP::SW2 in short) was extracted from Chlamydia inocula (collected from a well of infected McCoy cells in 6-well tray) using NucleoSpin Tissue (Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. NZ74095250). The genomic DNA extracted from transformed C. trachomatis (L2/pBR325::L2, L2/pGFP::SW2 or L2P-/pGFP::SW2) were used for sequencing and the transformation of E. coli to recover the shuttle plasmids.

Southern blotting

Restriction endonuclease digests of chlamydial genomic DNA were separated on agarose gels and then transferred to membranes using standard techniques [26]. The DNA used as probes in Figure 2 were either a ∼550 bp PCR amplicon for the β-lactamase gene using primer pair AmpF 5′-TTACCAATGCTTAAT-3′ and AmpR 5′-TACTCACCAGACACAG-3′) using pBR325::L2 as template or the whole recombinant chlamydial plasmid (pL2) released from the cloning vector pBR325::L2 by complete digestion with Bam HI (the insert was separated from the cloning vector by gel electrophoresis and the 7.5 kb fragment then eluted). DNA fragments were labeled with [α-32P]deoxy-CTP using a random primer labeling kit (Promega). The labeled products were purified by gel filtration on Sephadex G50. Membranes were pre-hybridized, hybridized overnight and then washed according to the manufacturer's standard conditions at 65°C. Dried membranes were exposed to Kodak XAR-5 film. In Figure 7 blots were probed with nonradioactive, digoxigenin-11-dUTP-labeled probes (Random primed DNA labelling) and chemiluminescence detection with CSPD (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Product No. 11 585 614 910). The gfp probe was a 739 bp Bam HI/Bgl II fragment from pGFP::SW2, which annealed to a 1445 bp fragment of Bam HI digested pGFP::SW2 or a 3625 bp fragment of Bgl II digested pGFP::SW2. The pSW2 probe template was a 2518 bp Eco RI fragment from pGFP::SW2 (between pSW2 CDS4 and CDS7), which annealed to a 7169 bp fragment of Bam HI digested pGFP::SW2 or a 5555 bp fragment of Bgl II digested pGFP::SW2. The ompA probe template was a 1022 bp PCR product from C. trachomatis L2 (25667R) using primers PCTM3 (5′ - TCCTTGCAAGCTCTGCCTGTGGGGAATCCT-3′) and NR1 (5′-CCGCAAGATTTTCTAGATTTC-3′) based on the C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu ompA sequence, this probe annealed to a 8837 bp fragment of Bam HI digested genomic DNA or a 5518 bp fragment of Bgl II digested genomic DNA.

pBR325::L2 copy number determination

McCoy cells grown to confluence in 96 well trays were infected with C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu transformed by pBR325::L2 at MOI = 1.0. EBs were allowed to adsorb to cells for 1 h at 37°C; cells were then washed with PBS to remove any residual unadsorbed EBs. The infected cells (performed in quadruplicate) were overlaid with 100 µl culture medium and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. At 65 h post infection, when the developmental cycle had completed, samples were stored (after snap freezing) at −80°C. For penicillin - treated cultures, medium containing 10 units/ml penicillin G was added at the time of infection. Chromosomal and plasmid DNA was extracted in a microplate format following a well described protocol. The residue was then resuspended in 100 µl nuclease-free water. Samples were diluted 1 in 100 prior to quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis. A quantitative real-time PCR protocol was used to determine the absolute number of chlamydial plasmids and genomes in samples using 5′ - exonuclease (TaqMan) assays with unlabelled primers andcarboxyfluorescein/carboxytetramethylrhodamine (FAM/TAMRA) dual-labeled probes as has been described previously.

Immunoblotting for detection of β-lactamase, chloramphenicol acetyl transferase and green fluorescent protein

Proteins from purified EBs and RBs were run on 10% SDS PAGE gels and the proteins were electroblotted onto a BioRad Immun-Blot PVDF (polyvinylidene difluoride) membrane for 1 h at 15 V. The membrane was incubated in a solution of PBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween-20 (PBS-T) and 5% dried milk for 30 min at room temperature. Commercially available antibodies that recognize the enzymes β-lactamase (AbCam mouse monoclonal Cat. No. ab12251) and chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (Sigma anti-CAT antiserum from rabbit product no. C9336) were used at a concentration of 10 µg/ml, the anti-GFP mouse monoclonal antibodies (Roche Cat no. 11814 460 001) were used at 0.4 µg/ml in a solution of PBS-T supplemented with 1% dried milk, and incubated with the membrane for 1 h at RT. Following extensive washing with PBS-T the membrane was incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat - anti-mouse or goat - anti-rabbit antibody (BioRad cat nos. 172-1011 and 172-1019) at the recommended dilution. After further washing with PBS-T the membrane was incubated in Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Scientific product no. 32106) as described by the manufacturer's instructions and exposed to Kodak BioMax XAR film.

Nitrocefin assays for β-lactamase

Nitrocefin changes from yellow to red in the presence of β-lactamase, therefore it can be used as an indicator of β-lactamase activity. A standard Nitrocefin assay was set up in 1 M Phosphate buffer (K2HPO4.3H20; KH2PO4) pH 7.0 using Nitrocefin (0.5 mg/ml) as described by the manufacturer (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany). Equal amounts of gradient-purified C. trachomatis RBs (as determined by qPCR assay) from pBR325::pL2 - transformed C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu and the wild–type parental C. trachomatis L2/434/Bu, and E. coli and pBR325::pL2 - transformed E. coli were used in this assay and samples were taken at 5 min intervals for OD readings at 486 nm.

Time course of infection

McCoy cells grown to confluence in 24 well trays were infected with C. trachomatis at MOI = 1. EBs were allowed to adsorb to cells for 1 h at 37°C and the infected cells were washed with PBS to remove any non-adsorbed EBs. The cells were then overlaid with culture medium or culture medium containing penicillin G at 10 units/ml and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. The infection was stopped at 8-hourly time points (8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, 64 and 72 h) by scraping up the cells and vortexing with glass beads. The samples were then rapidly frozen and stored at −80°C.

Iodine staining of inclusions

C. trachomatis strains were cultured in McCoy cells on coverslips. Briefly, infected cells bearing C. trachomatis inclusions were washed with PBS and then fixed to coverslips with ice-cold methanol. The coverslips were stained with 5% iodine stain (containing both potassium iodide and iodine in 50% ethanol) for 10 min. The stain was then changed for 2.5% iodine stain for 10 min and mounted in 5% iodine stain in glycerol (1 : 1) for photomicroscopy.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. SchachterJDawsonCR 1990 The epidemiology of trachoma predicts moreblindness in the future. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl 69 55 62

2. GerbaseACRowleyJTMertensTE 1998 Global epidemiology of sexuallytransmitted diseases. Lancet 351 Suppl 3 2 4

3. RockeyDDMatsumotoA 2000 The chlamydial developmental cycle. BrunYVShimketsLJ Prokaryotic Development Washington D.C. ASM Press 403 425

4. WardME 1983 Chlamydial classification, development and structure. Br Med Bull 39 109 115

5. FieldsKAHackstadtT 2002 The Chlamydial Inclusion: Escape from the endocytic pathway. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 18 221 245

6. SkiltonRJCutcliffeLTBarlowDWangYSalimO 2009 Penicillin induced persistence in Chlamydia trachomatis: high quality time lapse video analysis of the developmental cycle. PLoS One 4 e7723

7. StephensRSKalmanSLammelCFanJMaratheR 1998 Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science 282 754 759

8. Seth-SmithHMBHarrisSRPerssonKMarshPBarronA 2009 Co-evolution of genomes and plasmids within Chlamydia trachomatis and the emergence in Sweden of a new variant strain. BMC Genomics 10 239

9. RicciSCeveniniRCoscoEComanducciMRattiG 1993 Transcriptional analysis of the Chlamydia trachomatis plasmid pCT identifies temporally regulated transcripts, anti-sense RNA and σ70 -selected promoters. Mol Gen Genet 237 318 326

10. LiZChenDZhongYWangSZhongG 2008 The chlamydial plasmid-encoded protein pgp3 is secreted into the cytosol of Chlamydia-infected cells. Infect Immun 76 3415 3428

11. ClarkeIN 2010 Chlamydial transformation: facing up to the challenge. SchachterJByrneGICaldwellHDCherneskyMClarkeINMabeyDPaavonenJSaikkuPStarnbachMNStaryAStephensRSTimmsPWyrickPB Proceedings of the Twelfth International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infections, Salzburg, Austria 295 304

12. KariLGoheenMMRandallLBTaylorLDCarlsonJH 2011 Generation of targeted Chlamydia trachomatis null mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 7189 7193

13. BinetRMaurelliAT 2009 Transformation and isolation of allelic exchange mutants of Chlamydia psittaci using recombinant DNA introduced by electroporation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 292 297

14. TamJEDavisCHWyrickPB 1994 Expression of recombinant DNA introduced into Chlamydia trachomatis by electroporation. Can J Microbiol 40 583 591

15. PetersonEMMarkoffBASchachterJde la MazaLM 1990 The 7.5-kb plasmid present in Chlamydia trachomatis is not essential for the growth of this microorganism. Plasmid 23 144 148

16. FarencenaAComanducciMDonatiMRattiGCeveniniR 1997 Characterization of a new isolate of Chlamydia trachomatis which lacks the common plasmid and has properties of Biovar trachoma. Infect Immun 65 2965 2969

17. StothardDRWilliamsJAVan der PolBJonesRB 1998 Identification of a Chlamydia trachomatis serovar E urogenital isolate which lacks the cryptic plasmid. Infect Immun 66 6010 6013

18. MatsumotoAIzutsuHMiyashitaNOhuchiM 1998 Plaque formation by and plaque cloning of Chlamydia trachomatis biovar trachoma. J Clin Microbiol 36 3013 3019

19. PickettMAEversonJSPeadPJClarkeIN 2005 The plasmids of Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydophila pneumoniae (N16): accurate determination of copy number and the paradoxical effect of plasmid-curing agents. Microbiology 151 893 903

20. O'ConnellCMAbdelrahmanYMGreenEDarvilleHKSairaK 2011 Toll-like receptor 2 activation by Chlamydia trachomatis is plasmid dependent, and plasmid-responsive chromosomal loci are coordinately regulated in response to glucose limitation by C. trachomatis but not by C. muridarum. Infect Immun 79 1044 1056

21. O'ConnellCMNicksKM 2006 A plasmid-cured Chlamydia muridarum strain displays altered plaque morphology and reduced infectivity in cell culture. Microbiology 152 1601 1607

22. CarlsonJHWhitmireWMCraneDDWickeLVirtanevaK 2008 The Chlamydia trachomatis plasmid is a transcriptional regulator of chromosomal genes and a virulence factor. Infect Immun 76 2273 2283

23. ArmstrongJA 1967 Fine Structure of Lymphogranuloma Venereum Agent and the Effects of Penicillin and 5′ Fluorouracil. J Gen Microbiol 129 2001 2007

24. KramerMJGordonFB 1971 Ultra structural analysis of the effects of penicillin and chlortetracycline on the development of genital tract Chlamydia. Infect Immun 3 333 341

25. LambdenPRPickettMAClarkeIN 2006 The effect of penicillin on Chlamydia trachomatis DNA replication. Microbiology 152 2573 2578

26. SambrookJFritschEManiatisT 1989 Molecular Cloning A Laboratory Manual. New York Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press

27. SuchlandRJSandozKMJeffreyBMStammWERockeyDD 2009 Horizontal transfer of tetracycline resistance among Chlamydia spp. in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53 4604 4611

28. SandozKMRockeyDD 2010 Antibiotic resistance in Chlamydiae. Future Microbiol 5 1427 1442

29. LiCHChengYWLiaoPLYangYTKangJJ 2010 Chloramphenicol causes mitochondrial stress, decreases ATP biosynthesis, induces matrix metalloproteinase-13 expression, and solid-tumor cell invasion. Toxicol Sci 116 140 150

30. WorkowskiKABermanS 2010 Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 59 1 110

31. SkippPRobinsonJO'ConnorCDClarkeIN 2005 Shotgun proteomic analysis of Chlamydia trachomatis. Proteomics 5 1558 1573

32. ThomsonNRHoldenMTGCarderCLennardNLockeySJ 2008 Chlamydia trachomatis: Genome sequence analysis of lymphogranuloma venereum isolates. Genome Res 18 161 171

33. KahaneSSarovI 1987 Cloning of a Chlamydial Plasmid: Its use as a probe and in vitro Analysis of enclosed Polypeptides. Curr Microbiol 14 225 228

34. SchachterJMeyerKF 1969 Lymphogranuloma venereum: II. Characterisation of some recently isolated strains. J Bacteriol 99 636 638

35. PeelingRWBrunhamRC 1991 Neutralization of Chlamydia trachomatis: Kinetics and Stoichiometry. Infect Immun 59 2624 2630

36. MandelMHigaA 1970 Calcium-dependent bacteriophage DNA infection. J Mol Biol 53 159 162

37. KadonagaJTGautierAEStrausDRCharlesADEdgeMD 1984 The role of the beta-lactamase signal sequence in the secretion of proteins by Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 259 2149 2154

38. EkiciODKarlaAPaetzelMLivelyMOPeiD 2007 Altered -3 substrate specificity of Escherichia coli signal peptidase 1 mutants as revealed by screening a combinatorial peptide library. J Biol Chem 282 417 425

39. SkiltonRJCutcliffeLTPickettMALambdenPRFaneBA 2007 Intracellular parasitism of chlamydiae: specific infectivity of chlamydiaphage Chp2 in Chlamydophila abortus. J Bacteriol 189 4957 4959

40. EversonJSGarnerSAFaneBLiuB-LLambdenPR 2002 Biological Properties and Cell Tropism of Chp2, a Bacteriophage of the Obligate Intracellular Bacterium Chlamydophila abortus. J Bacteriol 184 2748 2754

41. HanahanD 1985 Techniques for Transformation of E.coli. GloverDM DNA cloning Oxford IRL Press 109 135

42. GrantGGNJesseJBloomFRHanahanD 1990 Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs transformed inth Esherichia coli methylation-resistant mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87 4645 4649

43. BanksJEddieBSchachterJMeyerKF 1970 Plaque Formation by Chlamydia in L Cells. Infect Immun 1 259 262

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiológia Infekčné lekárstvo Laboratórium

Článek Hostile Takeover by : Reorganization of Parasite and Host Cell Membranes during Liver Stage EgressČlánek A Trigger Enzyme in : Impact of the Glycerophosphodiesterase GlpQ on Virulence and Gene ExpressionČlánek An EGF-like Protein Forms a Complex with PfRh5 and Is Required for Invasion of Human Erythrocytes byČlánek Th2-polarised PrP-specific Transgenic T-cells Confer Partial Protection against Murine ScrapieČlánek Alterations in the Transcriptome during Infection with West Nile, Dengue and Yellow Fever Viruses

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2011 Číslo 9- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Očkování proti virové hemoragické horečce Ebola experimentální vakcínou rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP

- Koronavirus hýbe světem: Víte jak se chránit a jak postupovat v případě podezření?

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Unconventional Repertoire Profile Is Imprinted during Acute Chikungunya Infection for Natural Killer Cells Polarization toward Cytotoxicity

- Envelope Deglycosylation Enhances Antigenicity of HIV-1 gp41 Epitopes for Both Broad Neutralizing Antibodies and Their Unmutated Ancestor Antibodies

- Co-opts GBF1 and CERT to Acquire Host Sphingomyelin for Distinct Roles during Intracellular Development

- Nrf2, a PPARγ Alternative Pathway to Promote CD36 Expression on Inflammatory Macrophages: Implication for Malaria

- Robust Antigen Specific Th17 T Cell Response to Group A Streptococcus Is Dependent on IL-6 and Intranasal Route of Infection

- Targeting of a Chlamydial Protease Impedes Intracellular Bacterial Growth

- The Protease Cruzain Mediates Immune Evasion

- High-Resolution Phenotypic Profiling Defines Genes Essential for Mycobacterial Growth and Cholesterol Catabolism

- Plague and Climate: Scales Matter

- Exhausted CD8 T Cells Downregulate the IL-18 Receptor and Become Unresponsive to Inflammatory Cytokines and Bacterial Co-infections

- Maturation-Induced Cloaking of Neutralization Epitopes on HIV-1 Particles

- Murine Gamma-herpesvirus Immortalization of Fetal Liver-Derived B Cells Requires both the Viral Cyclin D Homolog and Latency-Associated Nuclear Antigen

- Rapid and Efficient Clearance of Blood-borne Virus by Liver Sinusoidal Endothelium

- Hostile Takeover by : Reorganization of Parasite and Host Cell Membranes during Liver Stage Egress

- A Trigger Enzyme in : Impact of the Glycerophosphodiesterase GlpQ on Virulence and Gene Expression

- Strain Specific Resistance to Murine Scrapie Associated with a Naturally Occurring Human Prion Protein Polymorphism at Residue 171

- Development of a Transformation System for : Restoration of Glycogen Biosynthesis by Acquisition of a Plasmid Shuttle Vector

- Monalysin, a Novel -Pore-Forming Toxin from the Pathogen Contributes to Host Intestinal Damage and Lethality

- Host Phylogeny Determines Viral Persistence and Replication in Novel Hosts

- BC2L-C Is a Super Lectin with Dual Specificity and Proinflammatory Activity

- Expression of the RAE-1 Family of Stimulatory NK-Cell Ligands Requires Activation of the PI3K Pathway during Viral Infection and Transformation

- Structure of the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus N-P Complex

- HSV Infection Induces Production of ROS, which Potentiate Signaling from Pattern Recognition Receptors: Role for S-glutathionylation of TRAF3 and 6

- The Human Papillomavirus E6 Oncogene Represses a Cell Adhesion Pathway and Disrupts Focal Adhesion through Degradation of TAp63β upon Transformation

- Analysis of Behavior and Trafficking of Dendritic Cells within the Brain during Toxoplasmic Encephalitis

- Exposure to the Viral By-Product dsRNA or Coxsackievirus B5 Triggers Pancreatic Beta Cell Apoptosis via a Bim / Mcl-1 Imbalance

- Multidrug Resistant 2009 A/H1N1 Influenza Clinical Isolate with a Neuraminidase I223R Mutation Retains Its Virulence and Transmissibility in Ferrets

- Structure of Herpes Simplex Virus Glycoprotein D Bound to the Human Receptor Nectin-1

- Step-Wise Loss of Bacterial Flagellar Torsion Confers Progressive Phagocytic Evasion

- Complex Recombination Patterns Arising during Geminivirus Coinfections Preserve and Demarcate Biologically Important Intra-Genome Interaction Networks

- An EGF-like Protein Forms a Complex with PfRh5 and Is Required for Invasion of Human Erythrocytes by

- Non-Lytic, Actin-Based Exit of Intracellular Parasites from Intestinal Cells

- The Fecal Viral Flora of Wild Rodents

- The General Transcriptional Repressor Tup1 Is Required for Dimorphism and Virulence in a Fungal Plant Pathogen

- Interferon Regulatory Factor-1 (IRF-1) Shapes Both Innate and CD8 T Cell Immune Responses against West Nile Virus Infection

- A Small Non-Coding RNA Facilitates Bacterial Invasion and Intracellular Replication by Modulating the Expression of Virulence Factors

- Evaluating the Sensitivity of to Biotin Deprivation Using Regulated Gene Expression

- The Motility of a Human Parasite, , Is Regulated by a Novel Lysine Methyltransferase

- Phosphodiesterase-4 Inhibition Alters Gene Expression and Improves Isoniazid – Mediated Clearance of in Rabbit Lungs

- Restoration of IFNγR Subunit Assembly, IFNγ Signaling and Parasite Clearance in Infected Macrophages: Role of Membrane Cholesterol

- Protease ROM1 Is Important for Proper Formation of the Parasitophorous Vacuole

- The Regulated Secretory Pathway in CD4 T cells Contributes to Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type-1 Cell-to-Cell Spread at the Virological Synapse

- Rerouting of Host Lipids by Bacteria: Are You CERTain You Need a Vesicle?

- Transmission Characteristics of the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic: Comparison of 8 Southern Hemisphere Countries

- Th2-polarised PrP-specific Transgenic T-cells Confer Partial Protection against Murine Scrapie

- Sequential Bottlenecks Drive Viral Evolution in Early Acute Hepatitis C Virus Infection

- Genomic Insights into the Origin of Parasitism in the Emerging Plant Pathogen

- Genomic and Proteomic Analyses of the Fungus Provide Insights into Nematode-Trap Formation

- Influenza Virus Ribonucleoprotein Complexes Gain Preferential Access to Cellular Export Machinery through Chromatin Targeting

- Alterations in the Transcriptome during Infection with West Nile, Dengue and Yellow Fever Viruses

- Protease-Sensitive Conformers in Broad Spectrum of Distinct PrP Structures in Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Are Indicator of Progression Rate

- Vaccinia Virus Protein C6 Is a Virulence Factor that Binds TBK-1 Adaptor Proteins and Inhibits Activation of IRF3 and IRF7

- c-di-AMP Is a New Second Messenger in with a Role in Controlling Cell Size and Envelope Stress

- Structural and Functional Studies on the Interaction of GspC and GspD in the Type II Secretion System

- APOBEC3A Is a Specific Inhibitor of the Early Phases of HIV-1 Infection in Myeloid Cells

- Impairment of Immunoproteasome Function by β5i/LMP7 Subunit Deficiency Results in Severe Enterovirus Myocarditis

- HTLV-1 Propels Thymic Human T Cell Development in “Human Immune System” Rag2 gamma c Mice

- Tri6 Is a Global Transcription Regulator in the Phytopathogen

- Exploiting and Subverting Tor Signaling in the Pathogenesis of Fungi, Parasites, and Viruses

- The Next Opportunity in Anti-Malaria Drug Discovery: The Liver Stage

- Significant Effects of Antiretroviral Therapy on Global Gene Expression in Brain Tissues of Patients with HIV-1-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders

- Inhibition of Competence Development, Horizontal Gene Transfer and Virulence in by a Modified Competence Stimulating Peptide

- A Novel Metal Transporter Mediating Manganese Export (MntX) Regulates the Mn to Fe Intracellular Ratio and Virulence

- Rhoptry Kinase ROP16 Activates STAT3 and STAT6 Resulting in Cytokine Inhibition and Arginase-1-Dependent Growth Control

- Hsp90 Governs Dispersion and Drug Resistance of Fungal Biofilms

- Secretion of Genome-Free Hepatitis B Virus – Single Strand Blocking Model for Virion Morphogenesis of Para-retrovirus

- A Viral Ubiquitin Ligase Has Substrate Preferential SUMO Targeted Ubiquitin Ligase Activity that Counteracts Intrinsic Antiviral Defence

- Membrane Remodeling by the Double-Barrel Scaffolding Protein of Poxvirus

- A Diverse Population of Molecular Type VGIII in Southern Californian HIV/AIDS Patients

- Disruption of TLR3 Signaling Due to Cleavage of TRIF by the Hepatitis A Virus Protease-Polymerase Processing Intermediate, 3CD

- Quantitative Analyses Reveal Calcium-dependent Phosphorylation Sites and Identifies a Novel Component of the Invasion Motor Complex

- Discovery of the First Insect Nidovirus, a Missing Evolutionary Link in the Emergence of the Largest RNA Virus Genomes

- Old World Arenaviruses Enter the Host Cell via the Multivesicular Body and Depend on the Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport

- Exploits a Unique Repertoire of Type IV Secretion System Components for Pilus Assembly at the Bacteria-Host Cell Interface

- Recurrent Signature Patterns in HIV-1 B Clade Envelope Glycoproteins Associated with either Early or Chronic Infections

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- HTLV-1 Propels Thymic Human T Cell Development in “Human Immune System” Rag2 gamma c Mice

- Hostile Takeover by : Reorganization of Parasite and Host Cell Membranes during Liver Stage Egress

- Exploiting and Subverting Tor Signaling in the Pathogenesis of Fungi, Parasites, and Viruses

- A Viral Ubiquitin Ligase Has Substrate Preferential SUMO Targeted Ubiquitin Ligase Activity that Counteracts Intrinsic Antiviral Defence

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy