-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Conjugative DNA Transfer Induces the Bacterial SOS Response and Promotes Antibiotic Resistance Development through Integron Activation

Conjugation is one mechanism for intra - and inter-species horizontal gene transfer among bacteria. Conjugative elements have been instrumental in many bacterial species to face the threat of antibiotics, by allowing them to evolve and adapt to these hostile conditions. Conjugative plasmids are transferred to plasmidless recipient cells as single-stranded DNA. We used lacZ and gfp fusions to address whether conjugation induces the SOS response and the integron integrase. The SOS response controls a series of genes responsible for DNA damage repair, which can lead to recombination and mutagenesis. In this manuscript, we show that conjugative transfer of ssDNA induces the bacterial SOS stress response, unless an anti-SOS factor is present to alleviate this response. We also show that integron integrases are up-regulated during this process, resulting in increased cassette rearrangements. Moreover, the data we obtained using broad and narrow host range plasmids strongly suggests that plasmid transfer, even abortive, can trigger chromosomal gene rearrangements and transcriptional switches in the recipient cell. Our results highlight the importance of environments concentrating disparate bacterial communities as reactors for extensive genetic adaptation of bacteria.

Published in the journal: Conjugative DNA Transfer Induces the Bacterial SOS Response and Promotes Antibiotic Resistance Development through Integron Activation. PLoS Genet 6(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001165

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001165Summary

Conjugation is one mechanism for intra - and inter-species horizontal gene transfer among bacteria. Conjugative elements have been instrumental in many bacterial species to face the threat of antibiotics, by allowing them to evolve and adapt to these hostile conditions. Conjugative plasmids are transferred to plasmidless recipient cells as single-stranded DNA. We used lacZ and gfp fusions to address whether conjugation induces the SOS response and the integron integrase. The SOS response controls a series of genes responsible for DNA damage repair, which can lead to recombination and mutagenesis. In this manuscript, we show that conjugative transfer of ssDNA induces the bacterial SOS stress response, unless an anti-SOS factor is present to alleviate this response. We also show that integron integrases are up-regulated during this process, resulting in increased cassette rearrangements. Moreover, the data we obtained using broad and narrow host range plasmids strongly suggests that plasmid transfer, even abortive, can trigger chromosomal gene rearrangements and transcriptional switches in the recipient cell. Our results highlight the importance of environments concentrating disparate bacterial communities as reactors for extensive genetic adaptation of bacteria.

Introduction

Free-living bacteria commonly face changing environments and must cope with varying conditions. These adaptive strategies involve temporary physiological responses through various groups of genes gathered in regulons that are induced or repressed according to the surrounding conditions. This is the case for the quorum sensing regulon [1], [2], the stringent response and catabolite repression systems, which allow adjustment of gene expression according to the growth conditions [3]–[5]. In other instances, the only adaptive solution requires a genetic change, and bacteria have developed mechanisms that favour genome modifications either by transiently increasing their mutation rates, inducing re-arrangements, or lateral (horizontal) gene transfer (HGT). One of the better known responses of this kind is the trigger of the SOS regulon, which controls DNA repair and recombination genes [6].

SOS is a bacterial stress response induced when an abnormal rate of single stranded DNA (ssDNA) is present in the cell. ssDNA is the substrate for RecA polymerization. The formation of a ssDNA/RecA nucleofilament stimulates auto-proteolysis of the LexA repressor, leading to de-repression of genes composing the SOS regulon. The SOS response is triggered by the accumulation of ssDNA, for example when cells try to replicate damaged DNA, after UV irradiation or treatment with antibiotics (fluoroquinolones, β-lactams) or mitomycin C (MMC), a DNA cross-linking agent. In addition to these endogenous sources, ssDNA is also produced by several mechanisms of exogenous DNA uptake involved in lateral gene transfer, namely by conjugation, transformation and occasionally transduction.

Conjugation is indeed one mechanism of lateral transfer that leads to the transient occurrence of ssDNA in the recipient cell [7], [8]. The presence of anti-SOS factors in some conjugative plasmids, such as the psiB gene of R64drd and R100-1 [9], suggests that conjugative DNA transfer can induce SOS. In plasmid R100-1, psiB (plasmidic SOS inhibition) was shown to be transiently expressed during the first 20 to 40 minutes of conjugation [10], [11] from a ssDNA promoter [12], and inhibited the bacterial SOS response [13], [14]. Plasmids carrying psiB do not all express it at levels sufficient to alleviate SOS, as seems to be the case in F plasmids for instance [9], [10], [13], [15], [16].

Conjugation is a widespread mechanism in the intestinal tract of host animals where there is a high concentration of bacterial populations [17]–[22]). Lateral gene transfer plays a large role in the evolution of genomes and emergence of new functions, such as antibiotic resistance, virulence and metabolic activities in bacterial species [23].

Bacteria can also possess other internal adaptive genetic resources. Vibrio cholerae carries a superintegron (SI), that can be used as a reservoir of silent genes that can be mobilized when needed. Integrons are natural gene expression systems allowing the integration of an ORF by site-specific recombination, transforming it into a functional gene [24]. Multi-resistant integrons (RI) have been isolated on mobile elements responsible for the assembly and rapid propagation of multiple antibiotic resistances in Gram-negative bacteria through association with conjugative plasmids [25], [26]. An integron is characterized by an intI gene, coding a site specific recombinase from the tyrosine recombinase family, and an adjacent primary recombination site attI [27]. The IntI integrase allows the integration of a circular promoterless gene cassette carrying a recombination site, attC, by driving recombination between attI and attC [28]. The integrated gene cassettes are expressed from the Pc promoter located upstream of the attI site in the integron platform [29]. The discovery of integrons in the chromosome of environmental strains of bacteria, and among these the superintegrons (SI) mentioned above, has led to the extension of their role from the “simple” acquisition of resistance genes to a wider role in the adaptation of bacteria to different environments [30].

The dynamics of cassette recombination and the regulation of integrase expression are poorly understood. Recently, it was shown that intI is regulated by the bacterial SOS response [31]. Since SOS is now known to induce both the RI and V.cholerae integrase expression, an important issue is to understand when and where cassette recombination takes place and how the integrase inducing SOS response is activated.

Our objective was to determine if conjugative ssDNA transfer can trigger the SOS response, and to which extent this affects intI expression and cassette recombination. SOS induction in promiscuous environments can prepare bacteria to face the many threats they can encounter there. In order to understand regulatory networks existing between conjugation and its effect on integron content and cassette expression, we first addressed if conjugation induces SOS using reporter fusions in V. cholerae and E. coli. After quantifying expression from the V. cholerae intIA promoter using GFP fusions, we adopted a genetic approach to test integrase-dependent site-specific recombination in vivo.

We show that conjugative plasmid transfer generally induces the SOS response and up-regulates integrase expression, triggering cassette recombination. However, this is not the case when an anti-SOS factor (psiB) is expressed, as seen for some narrow host range conjugative plasmids isolated from Enterobacteria. We further show that this anti-SOS function prevents up-regulation of the SOS regulon in a host-specific manner after conjugation. We demonstrate that conjugative transfer is sufficient to trigger integron cassette recombination in recipient cells. This study outlines the connections between conjugative lateral DNA transfer, bacterial stress response and recombination of gene cassettes in integrons, and provides new insights into the development of the antibiotic resistance within a population.

Results

Conjugative transfer of plasmids R388, R6Kdrd, and RP4 induces the SOS response in E. coli and V. cholerae

During conjugation, plasmid DNA enters the host cell in a single stranded fashion [7], [8]. In order to test whether conjugation induces the SOS response in the recipient cell, we used reporter E. coli and V. cholerae strains carrying sfiA::lacZ (7651) and recN::lacZ (7453) β-galactosidase fusions, respectively. sfiA (cell division in E.coli) and recN (recombinational repair) genes belong to the SOS regulon of E.coli. We also identified a LexA binding box upstream of recN in V. cholerae. We confirmed that induction of SOS in these strains results in expression of the β-galactosidase (β-gal) enzyme (not shown). Table 1 summarizes the conjugative plasmids belonging to several incompatibility groups we used in this study [32]. The donor (DH5α) strain was recA- and ΔlacZ.

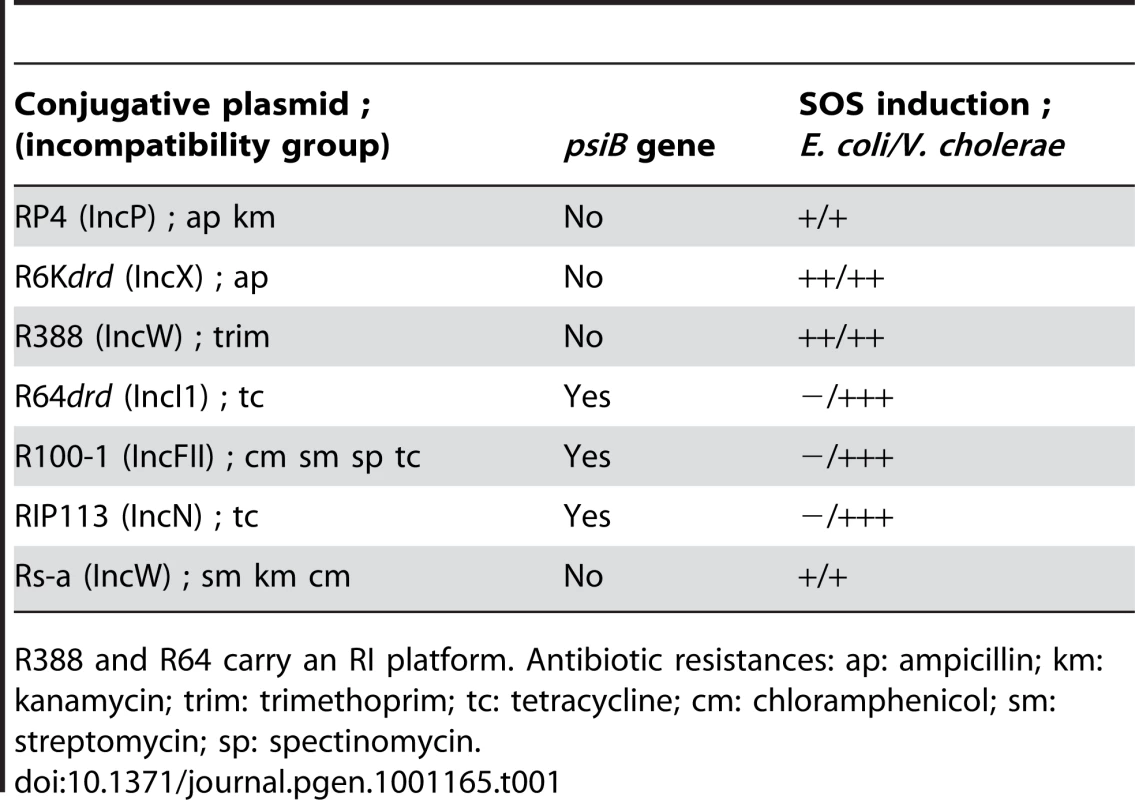

Tab. 1. Conjugative plasmids used in this study.

R388 and R64 carry an RI platform. Antibiotic resistances: ap: ampicillin; km: kanamycin; trim: trimethoprim; tc: tetracycline; cm: chloramphenicol; sm: streptomycin; sp: spectinomycin. The conjugation rates of these plasmids were first measured at various time points after donor and recipient cells were mixed (Figure 1A). In E. coli, all plasmids conjugate approximately at the same rate so that nearly all recipients have received a plasmid after 60 min of conjugation. In V. cholerae transfer rates vary considerably, only 1 in 105 cells have received a plasmid after 4h of mating with R6Kdrd and R388, while RP4 has a transfer rate similar to that of E. coli (10−1 to 1). Neither R64drd nor R100-1 replicate in V. cholerae. In order to address whether R100-1 actually transfers from E. coli into V. cholerae, we used pSU19-oriTF plasmids containing the oriTF (72 bp) of plasmid F. Plasmid F does not replicate in V. cholerae and oriTF is 98% identical to oriTR100. The high oriTF transfer rate observed at 1h of mating confirms that plasmids F and R100-1 (and presumably R64drd) can indeed transfer into V. cholerae and that the lack of R100/R64 transconjugants is due to their inability to establish themselves in this bacterium.

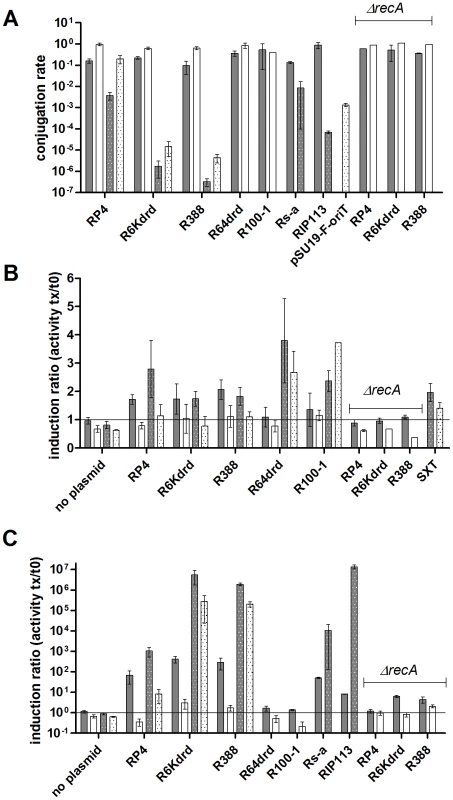

Fig. 1. Conjugation induces SOS in E. coli and V. cholerae.

Shaded bars: E. coli. Dotted bars: V. cholerae. Grey: values at peak of induction t40-t60min (for SXT, the peak is shown at t210); White: values at t240. A: conjugation rates in E. coli recA+ and recA (strains 7651 and 7713) and V. cholerae (7453); B: SOS induction in total population of recipient E. coli and V. cholerae measured by β-gal tests; C: SOS induction ratio in conjugants only, for E. coli and V. cholerae. Induction was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Induction ratios are units at time tx/units at time t0. SOS induction linked to conjugation was measured in the total recipient population by counting the actual number of recipient cells plated on selective medium instead of using OD units (Materials and Methods), to obtained an induction value per potential recipient cell. Mating was interrupted at various time points (t0, t40, t60, t120, t180, t240) and β-gal activity was measured in both E. coli and V. cholerae recipients (Figure 1B). The results are represented on the graph as the induction ratios at times t0, t60 and t240 over the induction at t0. When the recipient strain was mixed with empty donor, no SOS induction was observed. A peak of SOS induction in E .coli was detected after 40 min to 60 min of mating with a conjugation proficient donor, 1.7 fold induction for RP4 and R6Kdrd and 2.3 fold for R388. The induction peak was also observed in V. cholerae (2.3 fold for R6Kdrd, 2.7 fold for RP4 and 3.4 fold for R388). To verify that the β-gal activity was due to the SOS induction, we deleted the recA gene in the recipient E. coli strain. No induction of β-gal activity was observed in the ΔrecA strain after conjugation with RP4, R6Kdrd and R388. This confirms that the β-gal induction observed in recA+ strain indeed reflects the SOS induction by RP4, R6Kdrd and R388.

As described above, β-gal induction peaks between t40 and t60 minute of mating. The induction then decreases to reach the level shown at t240, forming bell shaped curves (data not shown). This induction pattern reflects the SOS induction in an asynchronous population of bacteria. It can be explained by the fact that plasmids RP4, R6Kdrd and R388 replicate in recipient cell. Once mating has started and as time goes by, there tends to be less plasmidless recipient cells. Indeed, entry of the plasmid DNA induces SOS, the incoming plasmidic ssDNA then replicates in the conjugant cell and the entry exclusion systems prevents entry of another plasmid [33], [34]. However, cells continue to divide so that the population of kanamycin resistant (kanR) host cells increases. Accordingly, even when the transfer rate remains constant (especially for low rated plasmids), the increase in the number of kanR cells can explain the drop of activity per recipient in the curve. The SOS response is expected to return to normal once all the cells have acquired the plasmid.

Since all cells in the recipient population have not received a conjugating DNA at the time of the β-gal assay, we calculated the SOS induction per conjugant, i.e. per recipient cell that has actually undergone DNA uptake (Materials and Methods). The results are represented as ratios over t0 in Figure 1C. As expected, the induction signal is amplified when one takes into account the conjugation rate for each plasmid. This amplification of several orders of magnitude is likely to be an effect of unsuccessful conjugation: SOS is induced by incoming DNA, that is not always converted into a replicating plasmid. The induction profiles, however, are compatible with Figure 1B: R388 and R6Kdrd strongly induce SOS, RP4 also shows a high induction, however it is lower than the former two plasmids. Once again, no (or very little) induction was observed in E .coli ΔrecA strain, confirming that conjugation induces RecA-dependent SOS response.

SOS induction by RP4 is weaker in both E. coli and V. cholerae, compared to induction during conjugation with R388 or R6Kdrd. We did not find any particular feature in the DNA sequence, or gene order of RP4 that could explain this observation. However, one can imagine that the higher transfer rate during RP4 conjugation is coupled with an early expression of entry exclusion systems, resulting in a quick decrease of ssDNA levels and repression of the SOS response.

To check if lower SOS induction was specific of RP4, we decided to test 2 other plasmids (Rs-a and RIP113) belonging to different incompatibility groups, at t60 - the peak for SOS induction observed for the plasmids mentioned earlier. Rs-a (IncW) induced SOS in E. coli and V. cholerae (Figure 1C and data not shown), confirming that SOS induction can be triggered by this plasmid. Interestingly, Rs-a conjugates at a rate of 10−1 and yields an intermediate induction level (like RP4). Even though we have a small sample of plasmids, SOS induction during mating seems to inversely correlate with conjugation rate (at 1h of mating) or replication of plasmids, except for R6Kdrd. Further study is needed to verify this observation. On the other hand, RIP113 (IncN) induced SOS in V. cholerae only (Figure S2).

An increasing number of non-replicative conjugative elements, generally named ICE, have been described in bacteria. One of the best studied is the SXT element discovered in V. cholerae [35]–[37]. We addressed if conjugative transfer of an SXT element integrated in the chromosome of E. coli [38] to V. cholerae also induces the SOS response. We observed a similar induction profile as for the conjugative plasmids with a peak of induction measured at t210 (Figure 1B). The delay can likely be explained by the very low transfer rate (10−6 after 6 six hours of mating).

Our results show that plasmids lacking the psiB gene (here RP4, R388, R6Kdrd and Rs-a) induce SOS upon conjugation into the recipient cell. On the other hand, RIP113 (IncN) induced SOS in V. cholerae only (Figure S2), thus behaving like R64drd and R100-1 plasmids.

PsiB strongly alleviates the SOS response in E. coli but only very weakly in V. cholerae: conjugation with plasmids R64drd and R100-1 induces SOS in V. cholerae

R64drd and R100-1 plasmids do not induce (or very poorly) the SOS response in E. coli (Figure 1B and 1C). This was expected as these plasmids carry a psiB anti-SOS gene. Plasmid RIP113 behaves like R64drd and R100-1 in terms of SOS induction in E. coli. We thus suspected RIP113 to carry a psiB gene as R64drd and R100 plasmids. This was confirmed by PCR amplification with psiB-specific primers (data not shown). This finding is supported by another IncN plasmid which has been sequenced: the R64 plasmid carries a gene named stbA (locus R46_027), presenting 42% DNA sequence identity with psiBF.

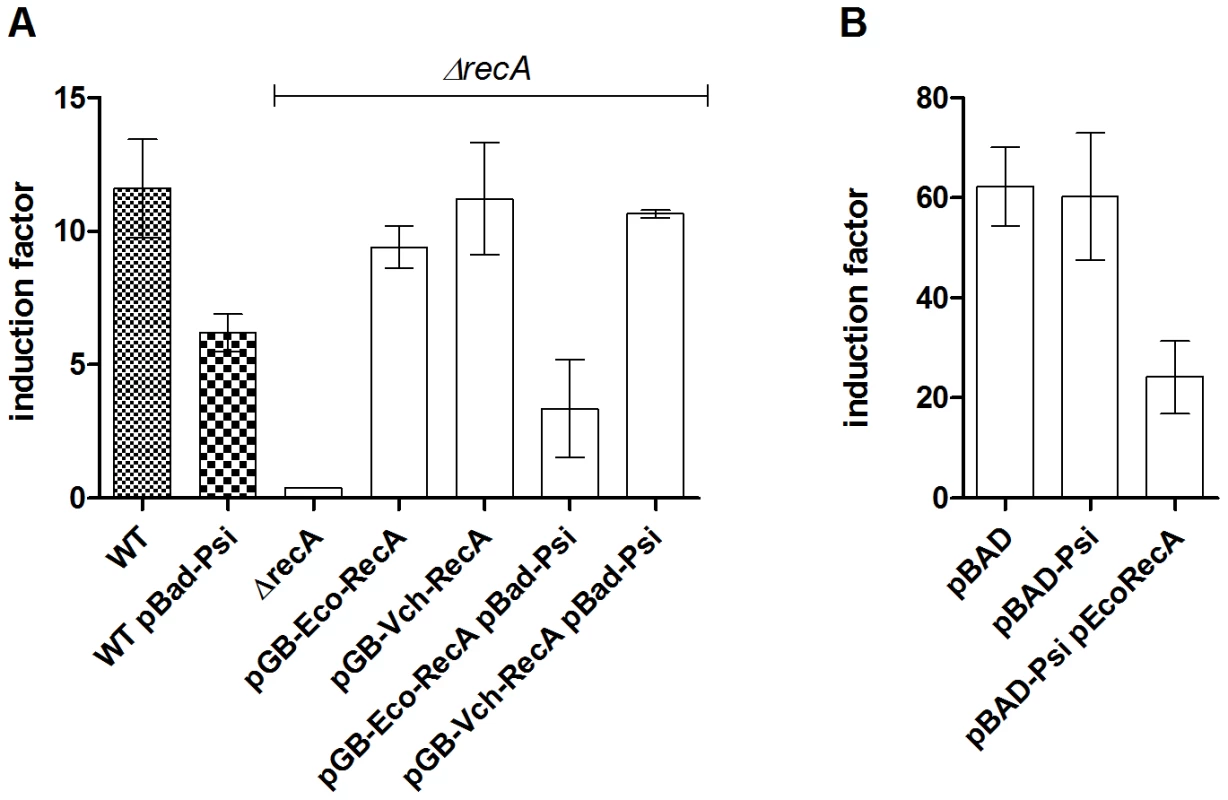

We observed a strong induction of SOS by the same 3 plasmids in V. cholerae (Figure 1C), suggesting that the psiB gene is either not expressed in V. cholerae or that its product is not active in this species (R64drd and R100-1 do not replicate in V. cholerae, thus no activity per conjugant could be calculated). Moreover, SOS induction is continuously high for R64drd and R100-1 plasmids after ∼60 min, whereas SOS induction declined after 60 min for RP4, R6Kdrd and R388, as mentioned above. We were unable to delete psiB from R64drd and thus could not check if in its absence SOS induction would be restored in E. coli. The reason for the unsuccessful cloning attempts could be the presence of several genes (such as ssb coding the single strand binding protein, anti-restriction gene ardA, or flm/hok) in the same region where ORFs and regulatory regions overlap [9], [11], [39]–[41], such that deletion of psiB could have unpredicted consequences on plasmid transfer and replication. Instead, psiB from R64drd was cloned and over-expressed from a pBAD plasmid, under the control of the arabinose inducible promoter. SOS induction after mitomycin C (MMC) treatment was measured in E. coli sfiA::lacZ and V. cholerae recN::lacZ containing either empty pBAD or pBAD-PsiB+ plasmids. As previously published [31], MMC treatment induced SOS in E. coli and V. cholerae (Figure 2). SOS induction was strongly reduced in E. coli when PsiB was expressed from pBAD (6 fold induction instead of 11.6 fold, Figure 2A) whereas SOS induction was insensitive to PsiB expression in V. cholerae (∼60 fold induction with and without PsiB over-expression, Figure 2B). These results show that the psiBR64drd (and presumably the psiBR100-1 which presents 85% identity to psiBR64) is expressed during conjugation in E. coli and inhibits the SOS response, whereas in V. cholerae, psiBR64drd/R100-1 has no or very little anti-SOS activity, allowing R64drd and R100-1 transfer to induce SOS. The fact that R64 and R100-1 are narrow host range enterobacterial plasmids [40], [42] and do not replicate in V. cholerae, can explain the continuous induction we observe. Entering plasmid DNA is not replicated and new rounds of conjugation can carry on, resulting in continuous re-induction of SOS.

Fig. 2. PsiB alleviates SOS induction in E. coli but not in V. cholerae because of impaired interaction with RecAVch.

β-gal tests showing SOS induction following MMC treatment. A: E. coli MG1655 sfiA::lacZ. B: V. cholerae recN::lacZ. Overnight cultures of E. coli 7651 and V. cholerae 7453 were diluted 100× in LB containing 0.2% arabinose and grown until OD∼0.5. SOS was induced for 1h with 0.2µg/ml MMC and β-gal tests were performed as described [61]. No MMC was added to control cultures. PsiB from narrow host range plasmids functions in a species-specific manner

The psiB anti-SOS function is found in several narrow host range plasmids belonging to the IncFI, IncFII, IncI1, IncK and IncN incompatibility groups [9] (and results obtained by blasting PsiB on GenBank plasmid sequences). These plasmids replicate in bacteria from the genera Enterobacter, Escherichia, Salmonella and Klebsiella. Bagdasarian and colleagues have suggested that PsiB could interact with RecA to inhibit its ability to induce SOS [16]. It was recently shown that PsiB binds to RecA in solution [43]. PsiB would then inhibit SOS by preventing RecA nucleofilament formation on ssDNA. Since PsiB from R64, R100-1 and RIP113 plasmids does not inhibit the SOS response in V. cholerae when over-expressed, we hypothesized that PsiB would be deficient in interacting with RecAVch. Our β-gal tests show that when expressed in V. cholerae together with RecAEco, PsiB reduces the SOS response from 60 fold to 24 fold induction (Figure 2B). Consistently, when co-expressed with RecAVch in an E. coli ΔrecA strain, PsiB does not alleviate SOS (Figure 2A, note that RecAVch is active in E. coli). Finally, expression of RecAEco in the E. coli ΔrecA strain complements SOS induction alleviation by PsiB. Altogether, these data suggest that PsiB is functional only in bacterial species where its carrier plasmids normally reside (here E. coli), thus antagonising RecA in a species-specific manner.

On the other hand, we showed that the RIP113 plasmid isolated from Salmonella, an enterobacterium, also carries the psiB gene and behaves like R64drd and R100-1 in inhibiting SOS in E. coli but not in V. cholerae. Unlike these two plasmids, RIP113 replicates in V. cholerae but since it was isolated in Salmonella, and to our knowledge IncN plasmids have not been described in V. cholerae so far, we considered that V. cholerae is not one of its usual hosts. To our knowledge PsiB is present only in narrow host range plasmids. We conclude that PsiB functions in a species-specific manner.

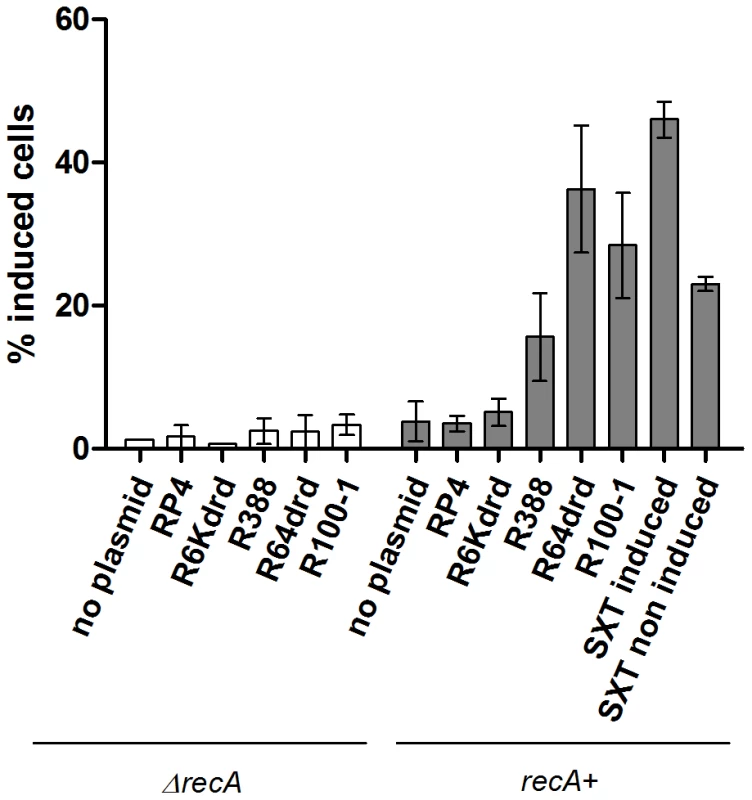

Conjugation induces the integron integrase

It was recently shown that the integron integrase is regulated by the SOS response [31]. We showed above that conjugational DNA transfer induces SOS. We then addressed whether conjugation affects V. cholerae IntIA SI integrase expression levels. To do this, we constructed a V. cholerae reporter strain containing a translational fusion between intIA and gfp (7093::p4640), and used flow cytometry to determine the fraction of cells where the integrase-GFP fusion was induced. As expected, no induction was observed in the ΔrecA control strain (Figure 3). In the recA+ strain we observe no induction after conjugation with RP4 and R6Kdrd (Figure 3). Alternatively, the integrase expression increased 2.8 fold when the strain is conjugated with R388, and 5.3 and 6.2 fold with R64drd and R100-1, respectively. In β-gal SOS induction tests shown earlier, RP4 and R6Kdrd also yielded a lower induction in total population graphs (Figure 1B). Note that β-gal induction reflects the recN promoter, which is more strongly expressed than the intI promoter. Our results imply that the SOS induction during RP4/R6Kdrd conjugation may not reach sufficiently high levels to induce the integrase reporter used in flow cytometry experiments.

Fig. 3. Conjugation induces V. cholerae integron integrase intIA expression.

Donor and recipient (7093::p4640 recA+ and ΔrecA) strains were grown until OD 0.2, mixed at a 1∶1 ratio and incubated overnight on filter. % of GFP-induced cells was measured by flow cytometry. Finally we tested mating of E. coli carrying an SXT element with V. cholerae. SXT transfer is induced through induction of SOS when the donor is treated with MMC [37]. Transfer of the SXT element into V. cholerae increased intIA promoter activity 12 fold compared to a plasmidless control and was 2 fold higher than uninduced cells (i.e. without MMC treatment of donor).

Conjugation triggers IntI1 integrase-dependent recombination

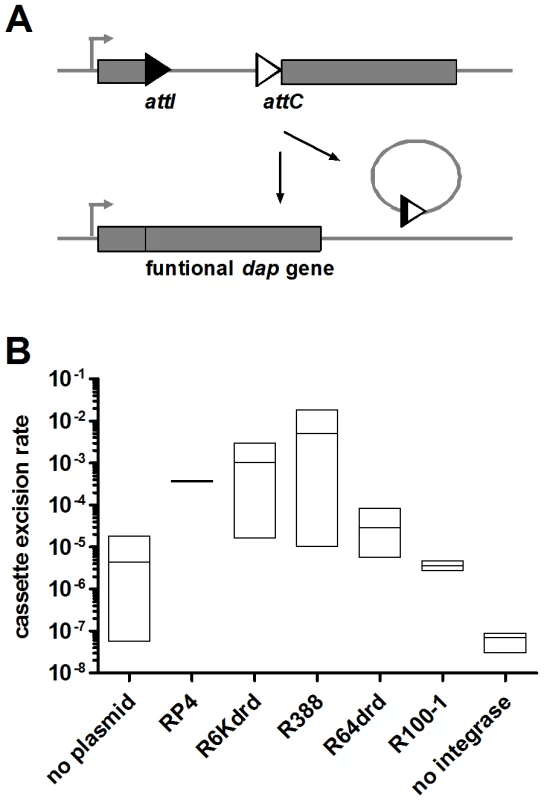

We have shown that conjugation induces SOS in the recipient bacteria and flow cytometry analysis clearly shows that the integron integrase is induced during conjugation in V. cholerae. In a first set of experiments, we wanted to test if the SOS induction leads to a higher activity of the integrase promoter in E. coli, using the class 1 integrase IntI1. We developed an experimental strategy in an E. coli strain that contains an insertion in the dapA gene (7949). This strain is unable to synthesize DAP (2,6-diaminopimelic acid), and as a result is not viable without DAP supplemented in the medium. The insertion in dapA is flanked by two specific recombination sites, attI and attC. Integrase expression causes site-specific recombination and excision of the synthetic cassette, restoring a functional dapA gene and allowing the strain to grow on DAP-free medium (Figure 4A). We transformed in this dapA - strain a multi-copy plasmid (p7755) carrying the intI1 gene under the control of its natural SOS regulated promoter. The recombination rate due to integrase expression is calculated as the ratio of the number of cells growing in the absence of DAP over the total number of cells. Figure 4B shows the cassette excision rate in E. coli 7949 p7755 after conjugation with different conjugative plasmids. In the absence of a conjugative plasmid in the donor cell, the spontaneous excision rate is about 10−5, which reflects the stringency of the intI promoter. Conjugation with R6Kdrd and R388 increases excision rate to 10−3 and 10−2 respectively, whereas conjugation with R64drd does not increase significantly beyond the basal recombination level. RP4 yields an intermediate level of DAP+ cells, which is compatible with its intermediate SOS induction level in E. coli. These results are consistent with SOS induction results in E. coli, and as expected, there is a correlation between SOS induction and integrase induced cassette recombination. To confirm that cassette recombination is due to integrase expression, we performed the same experiment in strain 7949 lacking the integrase carrying plasmid p7755, and no cassette excision was observed (<10−8). We conclude that conjugation with psiB deficient plasmids in E. coli induces the expression of the integrase from the intI1 promoter, and thus triggers cassette recombination.

Fig. 4. Conjugation increases IntI1-dependent cassette excision rate in E. coli.

A: experimental setup. 7949 strain contains plasmid p7755 carrying intI1 under the control of its natural LexA-regulated promoter. B: cassette excision rate was calculated by counting recombined cfu (Dap+) over total cfu. “No plasmid” means that recipient 7949 p7755 was mixed with empty donor. “No integrase” means that recipient 7949 without p7755 was conjugated with donor containing a conjugative plasmid. Conjugation triggers IntIA–mediated cassette recombination in the V. cholerae superintegron

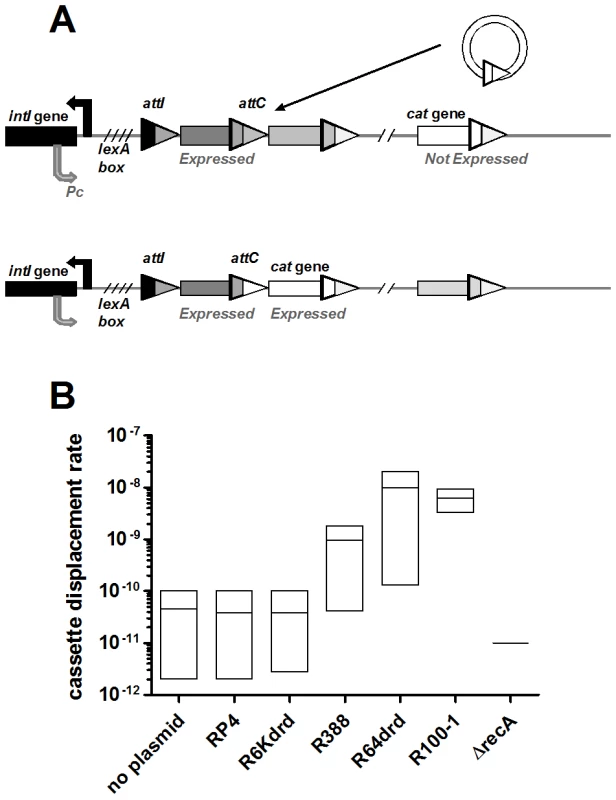

In the cassette excision experiment described above, we used a multicopy plasmid expressing the intI1 integrase in E. coli. Since conjugation induces the SOS response and in turn expression of the integron integrase in V. cholerae, we addressed in a second set of experiments whether conjugation in wild type V. cholerae can trigger recombination events in the superintegron. The V. cholerae SI carries a promoterless catB cassette that is not expressed in V. cholerae laboratory strain N16961 because it is located 7 cassettes (approximately 5000 bp) downstream of the Pc promoter [44]. When expressed, the catB gene confers resistance to chloramphenicol (Cm). We tested if conjugation can spontaneously yield Cm-resistant (Cm-R) V. cholerae cells, i.e. if IntIA is induced and recombines the catB cassette to a location allowing its expression (Figure 5A).

Fig. 5. Conjugation triggers IntIA-dependent cassette recombination in V.cholerae superintegron.

A: model: the catB cassette moved to 2nd position on the SI. B: cassette displacement rate, i.e Cm-R cfu over total cfu. “No plasmid” means that recipient was mixed with empty donor. Our results show that when the donor strain does not carry any conjugative plasmid, the rate of CmR cells is about 7.10−11 (Figure 5B). Consistent with the intIA induction results, conjugation with RP4 and R6Kdrd did not increase this frequency (6.10−11). Conjugation with R388, R64drd and R100-1 increased the CmR cfu appearance rate 28 fold, 280 fold and 140 fold, respectively. To verify that this increase was dependent on SOS, we deleted recA in the recipient strain and found that the conjugative plasmids yielded a rate of CmR lower than 10−11 for all plasmids (no colony observed).

To determine if these events corresponded to IntIA mediated cassette rearrangement, we performed a PCR analysis with primers in the Pc promoter and at the beginning of the catB cassette. In the wild type strain, this PCR amplifies a band of about 5000 bp. In the CmR colonies, the PCR amplified a band of 1432 bp (Figure S2A). Sequencing confirmed that the catB cassette had been relocated closer to the Pc promoter. catB was now present in second position, after the first cassette, compatible with an excision and integration in the first attC site downstream of attI. We know that IntIA can promote recombination between two attC sites [45]. The first cassette coding for a hypothetical protein downstream of attI may be important for viability under laboratory conditions. Alternatively, there may be a strong promoter in this first cassette, allowing a better expression of the catB cassette that could be insufficiently expressed from any other location under our selective conditions (involving high Cm concentrations).

In order to determine if cassettes between the Pc promoter and catB gene were deleted after rearrangement – i.e. if catB moved because cassettes were deleted or because it was re-integrated – we performed PCR analysis with several oligonucleotides amplifying cassettes located between attI and catB in V. cholerae N16961. We found that these cassettes were still present in the genome of the Cm-resistant clones (data not shown), showing that they were not deleted, and indicating that catB was relocated by recombination events.

To further address if other cassette rearrangements had occurred in those cells after conjugation, we isolated the genomic DNA (gDNA) from three CmR colonies obtained after conjugation. We digested gDNA with AccI, which has 35 restriction sites evenly distributed within the SI. We then hybridized with a mix of 10 probes complementary to 17 cassettes in the SI. The southern blot (Figure S2B) clearly shows that 2 of the 3 colonies have different hybridization profiles compared to the original N16961 gDNA, confirming that several cassettes (other than catB) have moved within the SI after conjugation induced SOS.

We conclude that conjugation with strong SOS inducing plasmids, R388, R64drd and R100-1, increases IntIA expression levels and promotes cassette rearrangements at a 100 fold to 1000 fold higher rate than under non stressful conditions. Although conjugation of R6Kdrd strongly induced the SOS response, it did not have any effect on intIA expression and cassette recombination in our experimental setup. Even though it is possible that R6Kdrd encodes an uncharacterized function able to specifically prevent the IntI expression during the SOS induction, we think this observation is most likely due to an insufficient sensitivity of our setup.

Discussion

We showed that conjugation of RP4, R6Kdrd, R388 and Rs-a plasmids, that do not carry any anti-SOS function, induces the SOS response in recipient E. coli and V. cholerae cells. Alternatively, plasmids R64drd, R100-1 and RIP113 that do carry the anti-SOS psiB gene do not induce SOS when the recipient cell is E. coli, while the SOS response is induced in V. cholerae. Finally, the SXT element (here integrated in the E. coli chromosome) is also able to induce SOS when it transfers to recipient V.cholerae.

Induction of SOS during conjugation

It has been shown that during inter-species Hfr conjugation, SOS is induced in the host cell [46], [47]. It was proposed that the low level of homology prevents rapid recombination of incoming DNA into the chromosome and thus dramatically enhances the SOS induction. This suggests that SOS induction levels may reflect the ability of RecA to find homologous DNA and initiate strand exchange [48]. In the case of plasmid conjugation, there is no homology with the bacterial chromosome, explaining the very high SOS induction levels we observe. Moreover, SOS induction proceeds as a wave. At the early stages of SOS induction, the concentration of LexA decreases as it is self-cleaved, then LexA synthesis is induced at later stages, and if ssDNA does not persist, the SOS induction level gradually decreases. This is what happens when RP4, R388 and R6Kdrd conjugate into E. coli cells (and RP4 in V.cholerae), and explains the bell-shaped induction curves we obtained. After 1h, nearly all the recipient cells are conjugants and no new conjugation is initiated because of plasmidic entry exclusion systems [49]. As conjugation or establishment rates are very low for R388 and R6Kdrd in V. cholerae, plasmidless host cells are always present in the total population so we observe a plateau reflecting new rounds of conjugation during the course of the experiment. The fact that R64drd and R100-1 are the strongest inducers in V. cholerae could thus be due to the inability of these plasmids to synthesize the complementary DNA strand and establish themselves in V. cholerae, increasing the prevalence of ssDNA accessible to RecA binding. Moreover, this strongly suggests that abortive conjugation induces SOS, which explains the fact that we are able to detect SOS induction in the total population despite the lack of transconjugants in V. cholerae. This is consistent with data showing very high induction values when we calculate the SOS induction in conjugants only. The plateau of induction in the whole population points to a “permanent conjugation state” where ssDNA enters the host cell, induces SOS, but does not replicated, and a new round of conjugation begins.

Another interesting observation is that SOS induction does not seem to prevent conjugation. Indeed, the conjugation rate for all plasmids (in E. coli for instance) is approximately the same after 2h of mating even though they induce SOS differently at the beginning of mating. To test this point, we used recipient cells already induced for SOS by pre-incubation with MMC, and these cells yielded the same conjugation rates in E. coli for a given plasmid regardless of the SOS induction level (Figure S1).

Narrow host range plasmids inhibit the SOS response in their natural host

SOS induction is due to RecA binding to ssDNA. We have shown above that plasmids R64drd, R100-1 and RIP113 that carry the anti-SOS psiB gene do not induce SOS when the recipient cell is E. coli. PsiB has been shown to interact with RecAEco in vitro [43] and in vivo (Figure 2), preventing it from binding to ssDNA and inducing the SOS response. Even though RecAVch and RecAEco show 79% protein identity, our data suggests that PsiB is impaired in its interaction with RecAVch in vivo (Figure 2), explaining why PsiB does not strongly reduce the SOS induction in V. cholerae as it does in E.coli. The presence of the psiB anti-SOS function in narrow host range plasmids such as R64 and R100 suggests that the dissemination strategies of narrow and broad host range plasmids could be distinct. Induction of the SOS response can be potentially detrimental to the host cell because of the induction of mutagenic polymerases or cell division arrest (like E.coli sfiA) [50]. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that narrow host range plasmids use their anti-SOS gene as a furtive strategy to hide from their customary host and thus prevent the host cell from being stressed and change its own or the incoming plasmid DNA. Note that by narrow host range plasmids, we mean plasmids that only replicate in a restricted number of bacteria (such as R64) but also plasmids that are found only in a few kinds of hosts in nature, even though they are able to replicate in others, such as the RIP113 originally in Salmonella.

SOS induction during conjugation leads to chromosome rearrangements

One consequence of SOS induction during conjugative DNA transfer is the triggering of integron cassette recombination. Conjugation with strong SOS inducer plasmids R388 and R6Kdrd in E. coli increases expression of IntI1 from its SOS regulated natural promoter leading to an increased RecA-dependent cassette excision rate, whereas plasmids R64drd and R100-1 that do not induce SOS in E. coli do not trigger cassette recombination in our E. coli cassette recombination assay. These results highlight the existence of a link between conjugation and site-specific recombination, leading to genome evolution. We also showed that conjugation triggers cassette recombination in the natural context of the SI carried in wild type V. cholerae. Plasmids R388, R64drd and R100-1 strongly induce SOS (and intIA) in V. cholerae and significantly increases the cassette recombination rate.

Our results highlight the link between conjugative HGT and genome evolvability in V. cholerae. Since conjugation induces integrase activity, one can consider conjugative plasmids as both vehicles for cassette dissemination and cassette shuffling for those already present in the SI. Indeed, some plasmids such as R388 [51] and R64 [52] carry an RI platform that can acquire new cassettes and transmit them to a new host by conjugation. It was shown that R388 can incorporate the catB cassette from the V. cholerae SI and transfer it to other bacteria [44]. Here we observed the displacement of a cat cassette catalyzed by the V. cholerae IntIA in its natural context. Conjugation can thus bring new cassettes but also favour their integration into the host chromosomal integron by inducing SOS.

Conjugation, SOS, and genome evolution

Cassette recombination upon conjugation could be a widespread mechanism, since conjugation is a naturally occurring phenomenon in highly concentrated bacterial environments, such as the host intestinal tract (see for example [17]–[19], [21]), biofilms [53]–[55] forming in the aquatic environment where V. cholerae grows, or even on medical equipment in hospitals [56]. Moreover, no mutation has been found in the bacterial chromosome that can prevent the uptake of conjugative DNA, meaning that bacteria cannot avoid being used as recipient cells [57]. By inducing the SOS response, incoming DNA triggers its own recombination not only through integrase induction but also homologous recombination, promoting genomic rearrangements.

Another important effect of SOS induction is the derepression of genes implicated in the transfer of integrating conjugative elements (ICEs), such as SXT from V.cholerae, which is a ∼100 kb ICE that transfers and integrates into the recipient bacterial genome, conferring resistance to several antibiotics [37]. Moreover, different ICEs are able to combine and create their own diversity in a RecA-dependent manner via homologous recombination [35], [36], and also, as observed here for SXT transfer in V. cholerae, by inducing SOS following transfer. Thus, SOS induction leads to genetic diversification of these mobile elements and to their transfer to surrounding bacteria, spreading antibiotic resistance genes, among others.

Conjugation induced SOS is thus one of the mechanisms allowing bacteria to evolve in their natural niches, creating the diversity that allows them to adapt to new environments and survive. Under conditions where SOS is prevented (by bacterial means such as the PsiB system or exogenously), cassette recombination is decreased to experimentally undetectable levels, showing that SOS induction plays an important role in adaptation, and can be used by broad host range plasmids to adapt to a new host. Consistently, narrow host range plasmids that do not need to adapt to a new host, express an SOS inhibitor to maintain the integrity of the plasmid DNA and host genome. This connection between host range and SOS induction needs to be expanded to a larger range of plasmids to determine its general character. A significant association between laterally transferred genes and gene rearrangements was already suggested in [58], which is consistent with our data, when we consider that SOS induction plays a major role in gene rearrangements. Remarkably, induction of SOS considerably enhances genome duplications and mutagenesis [59]. Further work is needed to test whether other HGT mechanisms, such as transformation, also induces SOS; considering that many bacterial species, like V. cholerae for instance, are naturally competent [60]. It would be interesting to investigate if SOS is induced in the gut of the host animal. If this were the case, inhibiting the bacterial SOS response would become an ideal target to prevent the acquisition of antibiotic resistance genes, and could be used in combination with antibiotics for the treatment of infections.

Materials and Methods

For strain and plasmid constructions, and oligonucleotide list, see Text S1 and Tables S1 and S2.

Conjugation and β-galactosidase tests

Overnight cultures of donor and recipient cells were diluted 100× in LB and grown until OD∼0.5. Donor and recipient cells were then mixed in 1∶1 ratio on 0.045µm conjugation filters on LB plates preheated at 37°C. At each time point, a filter was resuspended in 5ml LB and dilutions were plated on selective plates to count (i) conjugants and (ii) total number of recipients. For details, see Text S1.

β-gal tests were performed on these cultures as described ([61] and Text S1). According to the Miller formula:and we calculated:andwhere is the basal expression per cell when SOS is not induced. For details, see Text S1.

SOS induction tests using MMC were performed as published [31].

Flow cytometry

The same conjugation assay was performed overnight for the flow cytometry experiments. For each experiment, 100000 events were counted on the FACS-Calibur device. For details, see Text S1 and Figure S3.

Cassette excision measurements

Described in the Results section. For details, see Text S1.

Cassette displacement measurements

The recipient strain was V. cholerae N16961 (Cm sensitive 5µg/ml Cm). The donor strain was DH5α or a dap- derivative (Π1) for counter selection of Cm-R plasmids. Conjugations were performed as described for 4h. Filters were resuspended, centrifuged and the pellet was plated on LB medium containing 25µg/ml Cm. PCR screenings were performed using oligonucleotides cat2/i4 and the GoTaq polymerase. Oligonucleotides 896 to 905 were used to verify the presence of other cassettes.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. HammerBK

BasslerBL

2003

Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae.

Mol Microbiol

50

101

104

2. ZhuJ

MillerMB

VanceRE

DziejmanM

BasslerBL

2002

Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

99

3129

3134

3. SilvaAJ

BenitezJA

2004

Transcriptional regulation of Vibrio cholerae hemagglutinin/protease by the cyclic AMP receptor protein and RpoS.

J Bacteriol

186

6374

6382

4. BarkerMM

GaalT

GourseRL

2001

Mechanism of regulation of transcription initiation by ppGpp. II. Models for positive control based on properties of RNAP mutants and competition for RNAP.

J Mol Biol

305

689

702

5. BarkerMM

GaalT

JosaitisCA

GourseRL

2001

Mechanism of regulation of transcription initiation by ppGpp. I. Effects of ppGpp on transcription initiation in vivo and in vitro.

J Mol Biol

305

673

688

6. WalkerGC

1996

The SOS Response of Escherichia coli. Escherichia coli and Salmonella.

Neidhardt, FC Washington DC American Society of Microbiology

1

1400

1416

7. VielmetterW

BonhoefferF

SchutteA

1968

Genetic evidence for transfer of a single DNA strand during bacterial conjugation.

J Mol Biol

37

81

86

8. Bialkowska-HobrzanskaH

Kunicki-GoldfingerJH

1977

Mechanism of conjugation and recombination in bacteria XVI: single-stranded regions in recipient deoxyribonucleic acid during conjugation in Escherichia coli K-12.

Mol Gen Genet

151

319

326

9. GolubE

BailoneA

DevoretR

1988

A gene encoding an SOS inhibitor is present in different conjugative plasmids.

J Bacteriol

170

4392

4394

10. JonesAL

BarthPT

WilkinsBM

1992

Zygotic induction of plasmid ssb and psiB genes following conjugative transfer of Incl1 plasmid Collb-P9.

Mol Microbiol

6

605

613

11. AlthorpeNJ

ChilleyPM

ThomasAT

BrammarWJ

WilkinsBM

1999

Transient transcriptional activation of the Incl1 plasmid anti-restriction gene (ardA) and SOS inhibition gene (psiB) early in conjugating recipient bacteria.

Mol Microbiol

31

133

142

12. MasaiH

AraiK

1997

Frpo: a novel single-stranded DNA promoter for transcription and for primer RNA synthesis of DNA replication.

Cell

89

897

907

13. BagdasarianM

D'AriR

FilipowiczW

GeorgeJ

1980

Suppression of induction of SOS functions in an Escherichia coli tif-1 mutant by plasmid R100.1.

J Bacteriol

141

464

469

14. BagdasarianM

BailoneA

BagdasarianMM

ManningPA

LurzR

1986

An inhibitor of SOS induction, specified by a plasmid locus in Escherichia coli.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

83

5723

5726

15. DutreixM

BackmanA

CelerierJ

BagdasarianMM

SommerS

1988

Identification of psiB genes of plasmids F and R6-5. Molecular basis for psiB enhanced expression in plasmid R6-5.

Nucleic Acids Res

16

10669

10679

16. BagdasarianM

BailoneA

AnguloJF

ScholzP

BagdasarianM

1992

PsiB, and anti-SOS protein, is transiently expressed by the F sex factor during its transmission to an Escherichia coli K-12 recipient.

Mol Microbiol

6

885

893

17. LesterCH

Frimodt-MollerN

HammerumAM

2004

Conjugal transfer of aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance between Enterococcus faecium isolates in the intestine of streptomycin-treated mice.

FEMS Microbiol Lett

235

385

391

18. KurokawaK

ItohT

KuwaharaT

OshimaK

TohH

2007

Comparative metagenomics revealed commonly enriched gene sets in human gut microbiomes.

DNA Res

14

169

181

19. Garcia-QuintanillaM

Ramos-MoralesF

CasadesusJ

2008

Conjugal transfer of the Salmonella enterica virulence plasmid in the mouse intestine.

J Bacteriol

190

1922

1927

20. FeldL

SchjorringS

HammerK

LichtTR

DanielsenM

2008

Selective pressure affects transfer and establishment of a Lactobacillus plantarum resistance plasmid in the gastrointestinal environment.

J Antimicrob Chemother

61

845

852

21. TrobosM

LesterCH

OlsenJE

Frimodt-MollerN

HammerumAM

2009

Natural transfer of sulphonamide and ampicillin resistance between Escherichia coli residing in the human intestine.

J Antimicrob Chemother

63

80

86

22. NogueiraT

RankinDJ

TouchonM

TaddeiF

BrownSP

2009

Horizontal gene transfer of the secretome drives the evolution of bacterial cooperation and virulence.

Curr Biol

19

1683

1691

23. de la CruzF

DaviesJ

2000

Horizontal gene transfer and the origin of species: lessons from bacteria.

Trends Microbiol

8

128

133

24. MazelD

2006

Integrons: agents of bacterial evolution.

Nat Rev Microbiol

4

608

620

25. Rowe-MagnusDA

MazelD

1999

Resistance gene capture.

Curr Opin Microbiol

2

483

488

26. Martinez-FreijoP

FluitAC

SchmitzFJ

GrekVS

VerhoefJ

1998

Class I integrons in Gram-negative isolates from different European hospitals and association with decreased susceptibility to multiple antibiotic compounds.

J Antimicrob Chemother

42

689

696

27. CollisCM

KimMJ

StokesHW

HallRM

1998

Binding of the purified integron DNA integrase Intl1 to integron - and cassette-associated recombination sites.

Mol Microbiol

29

477

490

28. BouvierM

DemarreG

MazelD

2005

Integron cassette insertion: a recombination process involving a folded single strand substrate.

Embo J

24

4356

4367

29. JoveT

Da ReS

DenisF

MazelD

PloyMC

2010

Inverse correlation between promoter strength and excision activity in class 1 integrons.

PLoS Genet

6

e1000793

doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000793

30. Rowe-MagnusDA

MazelD

2002

The role of integrons in antibiotic resistance gene capture.

Int J Med Microbiol

292

115

125

31. GuerinE

CambrayG

Sanchez-AlberolaN

CampoyS

ErillI

2009

The SOS response controls integron recombination.

Science

324

1034

32. CouturierM

BexF

BergquistPL

MaasWK

1988

Identification and classification of bacterial plasmids.

Microbiol Rev

52

375

395

33. EckersonHW

ReynardAM

1977

Effect of entry exclusion on mating aggregates and transconjugants.

J Bacteriol

129

131

137

34. Garcillan-BarciaMP

de la CruzF

2008

Why is entry exclusion an essential feature of conjugative plasmids?

Plasmid

60

1

18

35. GarrissG

WaldorMK

BurrusV

2009

Mobile antibiotic resistance encoding elements promote their own diversity.

PLoS Genet

5

e1000775

doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000775

36. WozniakRA

FoutsDE

SpagnolettiM

ColomboMM

CeccarelliD

2009

Comparative ICE genomics: insights into the evolution of the SXT/R391 family of ICEs.

PLoS Genet

5

e1000786

doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000786

37. BeaberJW

HochhutB

WaldorMK

2004

SOS response promotes horizontal dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes.

Nature

427

72

74

38. BurrusV

WaldorMK

2003

Control of SXT integration and excision.

J Bacteriol

185

5045

5054

39. HowlandCJ

ReesCE

BarthPT

WilkinsBM

1989

The ssb gene of plasmid ColIb-P9.

J Bacteriol

171

2466

2473

40. DelverEP

BelogurovAA

1997

Organization of the leading region of IncN plasmid pKM101 (R46): a regulation controlled by CUP sequence elements.

J Mol Biol

271

13

30

41. KomanoT

YoshidaT

NaraharaK

FuruyaN

2000

The transfer region of IncI1 plasmid R64: similarities between R64 tra and legionella icm/dot genes.

Mol Microbiol

35

1348

1359

42. ChilleyPM

WilkinsBM

1995

Distribution of the ardA family of antirestriction genes on conjugative plasmids.

Microbiology

141

Pt 9

2157

2164

43. PetrovaV

Chitteni-PattuS

DreesJC

InmanRB

CoxMM

2009

An SOS Inhibitor that Binds to Free RecA Protein: The PsiB Protein.

Mol Cell

36

121

130

44. Rowe-MagnusDA

GueroutAM

MazelD

2002

Bacterial resistance evolution by recruitment of super-integron gene cassettes.

Mol Microbiol

43

1657

1669

45. BiskriL

BouvierM

GueroutAM

BoisnardS

MazelD

2005

Comparative study of class 1 integron and Vibrio cholerae superintegron integrase activities.

J Bacteriol

187

1740

1750

46. MaticI

RayssiguierC

RadmanM

1995

Interspecies gene exchange in bacteria: the role of SOS and mismatch repair systems in evolution of species.

Cell

80

507

515

47. MaticI

TaddeiF

RadmanM

2000

No genetic barriers between Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and Escherichia coli in SOS-induced mismatch repair-deficient cells.

J Bacteriol

182

5922

5924

48. DelmasS

MaticI

2005

Cellular response to horizontally transferred DNA in Escherichia coli is tuned by DNA repair systems.

DNA Repair (Amst)

4

221

229

49. FuruyaN

KomanoT

1994

Surface exclusion gene of IncI1 plasmid R64: nucleotide sequence and analysis of deletion mutants.

Plasmid

32

80

84

50. KelleyWL

2006

Lex marks the spot: the virulent side of SOS and a closer look at the LexA regulon.

Mol Microbiol

62

1228

1238

51. RevillaC

Garcillan-BarciaMP

Fernandez-LopezR

ThomsonNR

SandersM

2008

Different pathways to acquiring resistance genes illustrated by the recent evolution of IncW plasmids.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother

52

1472

1480

52. KomanoT

1999

Shufflons: multiple inversion systems and integrons.

Annu Rev Genet

33

171

191

53. MolinS

Tolker-NielsenT

2003

Gene transfer occurs with enhanced efficiency in biofilms and induces enhanced stabilisation of the biofilm structure.

Curr Opin Biotechnol

14

255

261

54. WuertzS

OkabeS

HausnerM

2004

Microbial communities and their interactions in biofilm systems: an overview.

Water Sci Technol

49

327

336

55. SorensenSJ

BaileyM

HansenLH

KroerN

WuertzS

2005

Studying plasmid horizontal transfer in situ: a critical review.

Nat Rev Microbiol

3

700

710

56. HuqA

WhitehouseCA

GrimCJ

AlamM

ColwellRR

2008

Biofilms in water, its role and impact in human disease transmission.

Curr Opin Biotechnol

19

244

247

57. Perez-MendozaD

de la CruzF

2009

Escherichia coli genes affecting recipient ability in plasmid conjugation: are there any?

BMC Genomics

10

71

58. HaoW

GoldingGB

2009

Does gene translocation accelerate the evolution of laterally transferred genes?

Genetics

182

1365

1375

59. DimpflJ

EcholsH

1989

Duplication mutation as an SOS response in Escherichia coli: enhanced duplication formation by a constitutively activated RecA.

Genetics

123

255

260

60. MeibomKL

BlokeschM

DolganovNA

WuCY

SchoolnikGK

2005

Chitin induces natural competence in Vibrio cholerae.

Science

310

1824

1827

61. Miller

1992

A short course in bacterial genetics

Cold Spring Harbor, NY

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2010 Číslo 10- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Common Genetic Variants and Modification of Penetrance of -Associated Breast Cancer

- FSHD: A Repeat Contraction Disease Finally Ready to Expand (Our Understanding of Its Pathogenesis)

- Genome-Wide Identification of Targets and Function of Individual MicroRNAs in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Allele-Specific Down-Regulation of Expression Induced by Retinoids Contributes to Climate Adaptations

- The Meiotic Recombination Checkpoint Suppresses NHK-1 Kinase to Prevent Reorganisation of the Oocyte Nucleus in

- Actin Depolymerizing Factors Cofilin1 and Destrin Are Required for Ureteric Bud Branching Morphogenesis

- DSIF and RNA Polymerase II CTD Phosphorylation Coordinate the Recruitment of Rpd3S to Actively Transcribed Genes

- Continuous Requirement for the Clr4 Complex But Not RNAi for Centromeric Heterochromatin Assembly in Fission Yeast Harboring a Disrupted RITS Complex

- Genome-Wide Association Study of Blood Pressure Extremes Identifies Variant near Associated with Hypertension

- The Cytosine Methyltransferase DRM2 Requires Intact UBA Domains and a Catalytically Mutated Paralog DRM3 during RNA–Directed DNA Methylation in

- β-Actin and γ-Actin Are Each Dispensable for Auditory Hair Cell Development But Required for Stereocilia Maintenance

- Genetic Association Study Identifies as a Risk Gene for Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy

- Evidence for a Xer/ System for Chromosome Resolution in Archaea

- Four Novel Loci (19q13, 6q24, 12q24, and 5q14) Influence the Microcirculation

- Lifespan Extension by Preserving Proliferative Homeostasis in

- Ancient and Recent Adaptive Evolution of Primate Non-Homologous End Joining Genes

- Loss of the p53/p63 Regulated Desmosomal Protein Perp Promotes Tumorigenesis

- Altering a Histone H3K4 Methylation Pathway in Glomerular Podocytes Promotes a Chronic Disease Phenotype

- Characterization of LINE-1 Ribonucleoprotein Particles

- Conserved Genes Act as Modifiers of Invertebrate SMN Loss of Function Defects

- Alternative Splicing at a NAGNAG Acceptor Site as a Novel Phenotype Modifier

- Tight Regulation of the Gene of the KplE1 Prophage: A New Paradigm for Integrase Gene Regulation

- Conjugative DNA Transfer Induces the Bacterial SOS Response and Promotes Antibiotic Resistance Development through Integron Activation

- Nasty Viruses, Costly Plasmids, Population Dynamics, and the Conditions for Establishing and Maintaining CRISPR-Mediated Adaptive Immunity in Bacteria

- Stress-Induced Activation of Heterochromatic Transcription

- H3K27me3 Profiling of the Endosperm Implies Exclusion of Polycomb Group Protein Targeting by DNA Methylation

- Simultaneous Disruption of Two DNA Polymerases, Polη and Polζ, in Avian DT40 Cells Unmasks the Role of Polη in Cellular Response to Various DNA Lesions

- Characterising and Predicting Haploinsufficiency in the Human Genome

- Dual Functions of ASCIZ in the DNA Base Damage Response and Pulmonary Organogenesis

- Pervasive Cryptic Epistasis in Molecular Evolution

- Transition from Positive to Neutral in Mutation Fixation along with Continuing Rising Fitness in Thermal Adaptive Evolution

- Comprehensive Analysis Reveals Dynamic and Evolutionary Plasticity of Rab GTPases and Membrane Traffic in

- Regulates Tissue-Specific Mitochondrial DNA Segregation

- Role for the Mammalian Swi5-Sfr1 Complex in DNA Strand Break Repair through Homologous Recombination

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Genome-Wide Identification of Targets and Function of Individual MicroRNAs in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- Common Genetic Variants and Modification of Penetrance of -Associated Breast Cancer

- Allele-Specific Down-Regulation of Expression Induced by Retinoids Contributes to Climate Adaptations

- Simultaneous Disruption of Two DNA Polymerases, Polη and Polζ, in Avian DT40 Cells Unmasks the Role of Polη in Cellular Response to Various DNA Lesions

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy