-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Genomic Hotspots for Adaptation: The Population Genetics of Müllerian Mimicry in

Wing pattern evolution in Heliconius butterflies provides some of the most striking examples of adaptation by natural selection. The genes controlling pattern variation are classic examples of Mendelian loci of large effect, where allelic variation causes large and discrete phenotypic changes and is responsible for both convergent and highly divergent wing pattern evolution across the genus. We characterize nucleotide variation, genotype-by-phenotype associations, linkage disequilibrium (LD), and candidate gene expression patterns across two unlinked genomic intervals that control yellow and red wing pattern variation among mimetic forms of Heliconius erato. Despite very strong natural selection on color pattern, we see neither a strong reduction in genetic diversity nor evidence for extended LD across either patterning interval. This observation highlights the extent that recombination can erase the signature of selection in natural populations and is consistent with the hypothesis that either the adaptive radiation or the alleles controlling it are quite old. However, across both patterning intervals we identified SNPs clustered in several coding regions that were strongly associated with color pattern phenotype. Interestingly, coding regions with associated SNPs were widely separated, suggesting that color pattern alleles may be composed of multiple functional sites, conforming to previous descriptions of these loci as “supergenes.” Examination of gene expression levels of genes flanking these regions in both H. erato and its co-mimic, H. melpomene, implicate a gene with high sequence similarity to a kinesin as playing a key role in modulating pattern and provides convincing evidence for parallel changes in gene regulation across co-mimetic lineages. The complex genetic architecture at these color pattern loci stands in marked contrast to the single casual mutations often identified in genetic studies of adaptation, but may be more indicative of the type of genetic changes responsible for much of the adaptive variation found in natural populations.

Published in the journal: Genomic Hotspots for Adaptation: The Population Genetics of Müllerian Mimicry in. PLoS Genet 6(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000796

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000796Summary

Wing pattern evolution in Heliconius butterflies provides some of the most striking examples of adaptation by natural selection. The genes controlling pattern variation are classic examples of Mendelian loci of large effect, where allelic variation causes large and discrete phenotypic changes and is responsible for both convergent and highly divergent wing pattern evolution across the genus. We characterize nucleotide variation, genotype-by-phenotype associations, linkage disequilibrium (LD), and candidate gene expression patterns across two unlinked genomic intervals that control yellow and red wing pattern variation among mimetic forms of Heliconius erato. Despite very strong natural selection on color pattern, we see neither a strong reduction in genetic diversity nor evidence for extended LD across either patterning interval. This observation highlights the extent that recombination can erase the signature of selection in natural populations and is consistent with the hypothesis that either the adaptive radiation or the alleles controlling it are quite old. However, across both patterning intervals we identified SNPs clustered in several coding regions that were strongly associated with color pattern phenotype. Interestingly, coding regions with associated SNPs were widely separated, suggesting that color pattern alleles may be composed of multiple functional sites, conforming to previous descriptions of these loci as “supergenes.” Examination of gene expression levels of genes flanking these regions in both H. erato and its co-mimic, H. melpomene, implicate a gene with high sequence similarity to a kinesin as playing a key role in modulating pattern and provides convincing evidence for parallel changes in gene regulation across co-mimetic lineages. The complex genetic architecture at these color pattern loci stands in marked contrast to the single casual mutations often identified in genetic studies of adaptation, but may be more indicative of the type of genetic changes responsible for much of the adaptive variation found in natural populations.

Introduction

Understanding how adaptive phenotypes arise is vital for understanding the origins of biodiversity and for predicting how organisms will respond to novel selective pressures [1]. Nonetheless, there are still only a handful of examples where the molecular elements underlying adaptive variation in nature have been identified [2]–[6]. This situation is changing as new technologies make it possible to leverage nature's diversity and focus research directly on taxa that are both ecologically tractable and possess characteristics (life history switches, behavioral modifications, or phenotypic differences) with a priori evidence of their adaptive role [7]–[10]. The data that will emerge from these studies promise fresh insights into the genetic architecture and origins of functional variation and an exciting new understanding of the interplay between genes, development, and natural selection.

Heliconius butterflies offer exceptional opportunities for genomic level studies designed to understand how adaptive morphological diversity is generated in nature [11]–[13]. The group is renowned as one of the great insect radiations and provides textbook examples of adaptation by natural selection, mimicry, and speciation [14],[15]. The vivid wing patterns of Heliconius are adaptations that warn potential predators of the butterflies' unpalatability and also play a key role in speciation [16]–[18]. Perhaps the greatest strength of Heliconius for understanding the origins of functional variation lies is the wealth of parallel and convergent adaptation in the group - a pattern best exemplified by the parallel mimetic radiations of H. erato and H. melpomene [19]–[23]. The two species are distantly related and never hybridize [24],[25]; yet, they possess nearly identical wing patterns and have undergone nearly perfectly congruent radiations into over 25 distinctively different color pattern races [21]. The convergent and divergent color pattern changes within and between Heliconius species provide “natural” replicates of the evolutionary process where independent lineages have produced similar phenotypes due to natural selection. Indeed, within both the H. erato and H. melpomene radiations, there are multiple disjunct populations that share identical, yet possibly independently evolved, wing patterns [26],[27] (for an alternative, shifting balance view, see [22],[28]). Moreover, recent comparative research has demonstrated that the diversity of color patterns found within H. erato, H. melpomene and in other Heliconius species, is modulated by a small number of apparently homologous genomic intervals [29]–[31], which provides a powerful evolutionary framework for examining the origins of functional variation and allows insights into the repeatability of evolution.

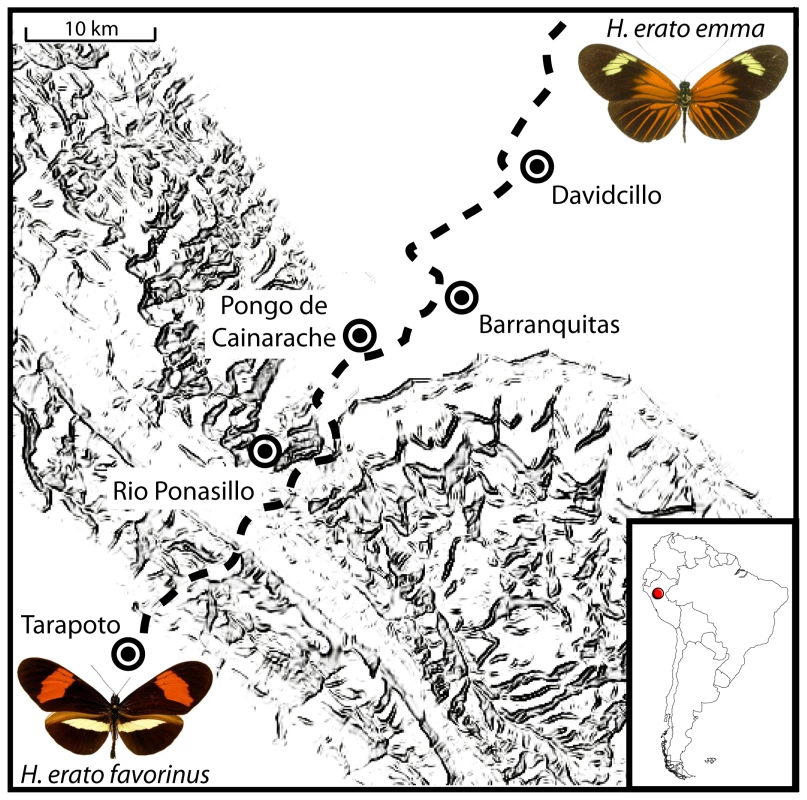

The patchwork of differently patterned races in H. erato and H. melpomene is stitched together by dozens of narrow hybrid zones [20]–[22], allowing detailed analysis of the forces that generate and maintain adaptive variation in this group [32]. Here, and in our companion paper [33], we exploit concordant hybrid zones to explore patterns of nucleotide diversity and linkage disequilibrium (LD) across two of the three interacting genomic regions that control most of the adaptive differences in wing color patterns. The transition between the “postman”, H. e. favorinus and H. m. amaryllis, and “rayed”, H. e. emma and H. m. agalope, races of the two co-mimics in eastern Peru is one of the best described hybrid zones in Heliconius and occurs over a distance of slightly more than 10 km (Figure 1 and [33]). Strong natural selection maintains this sharp phenotypic boundary in both species and per locus selective coefficients on color pattern loci are estimated to be greater than 0.2 both using field release experiments and by fitting the observed cline in allelic frequencies at each of the color pattern loci to a theoretical cline maintained by frequency dependent selection [34],[35]. Despite strong natural selection, there are no strong pre - or post-mating barriers to hybridization between races of either H. erato or H. melpomene and in the center of the hybrid zone there is frequent admixture between divergent color pattern races.

Fig. 1. Sampling sites across the transition between H. e. favorinus and H. e. emma.

Geographic representation of the five locations where H. erato was sampled across the Eastern Peruvian hybrid zone. Dotted line is approximate location of the Tarapoto-Yurimaguas road that transects the hybrid zone and was used for sampling. The D locus affects the presence of the proximal red patch (“dennis”), red hindwing rays and the forewing band color. The Cr locus is responsible for the presence of the hindwing yellow bar and interacts with the Sd locus to affect the shape of the forewing band and hindwing bar. Our study focuses on two H. erato patterning loci, D and Cr. These two loci map to different linkage groups and interact to control major differences in the wing color patterns of H. erato races. The chromosomal regions tightly linked with the D and Cr loci in H. erato were recently identified [36]–[38] and map to homologous regions of the genome that control similar color pattern changes in H. erato's co-mimic, H. melpomene [29],[31]. Variation in D in H. erato and D/B in H. melpomene cause analogous changes in the distribution of red pigments on the fore - and hindwings (see[30],[31],[39]). Similarly, Cr (H. erato) and the Yb-complex (H. melpomene) cause similar shifts in the distribution of melanic scales revealing underlying white and yellow pattern elements (see [29]). This region also contains the H. numata P locus, a close relative of H. melpomene. However, the P locus causes dramatically different pattern changes among sympatric races of H. numata highlighting the extraordinary ‘jack-of-all-trades’ flexibility of these genomic regions [29].

Wing pattern variation across Heliconius hybrid zones serves as a “natural” laboratory for genome level research into processes that generate and maintain adaptive variation. One of the most extensively studied Heliconius hybrid zones is found in Eastern Peru, where Mallet and coworkers estimated the strength of natural selection on the three unlinked color pattern loci that control phenotypic differences between “rayed” and “postman” races of H. erato [34],[35],[40]. We have taken the next step and used this same Peruvian H. erato hybrid zone to make four major advancements: (1) we have identified and sequenced narrow genomic intervals containing two of the three interacting loci that cause major adaptive shifts in wing patterns; (2) we have documented a rapid decay of LD in natural populations across a sharp phenotypic transition both within genes and across these intervals; (3) we have identified several genes strongly associated with the transition in warningly-colored wing patterns; and (4) we have examined expression levels in these and adjacent genes during wing development. These data, in combination with data presented in the companion paper [33], refine our understanding of the molecular nature of color pattern loci and suggest that multiple functional sites underlie adaptive morphological variation in Heliconius.

Results

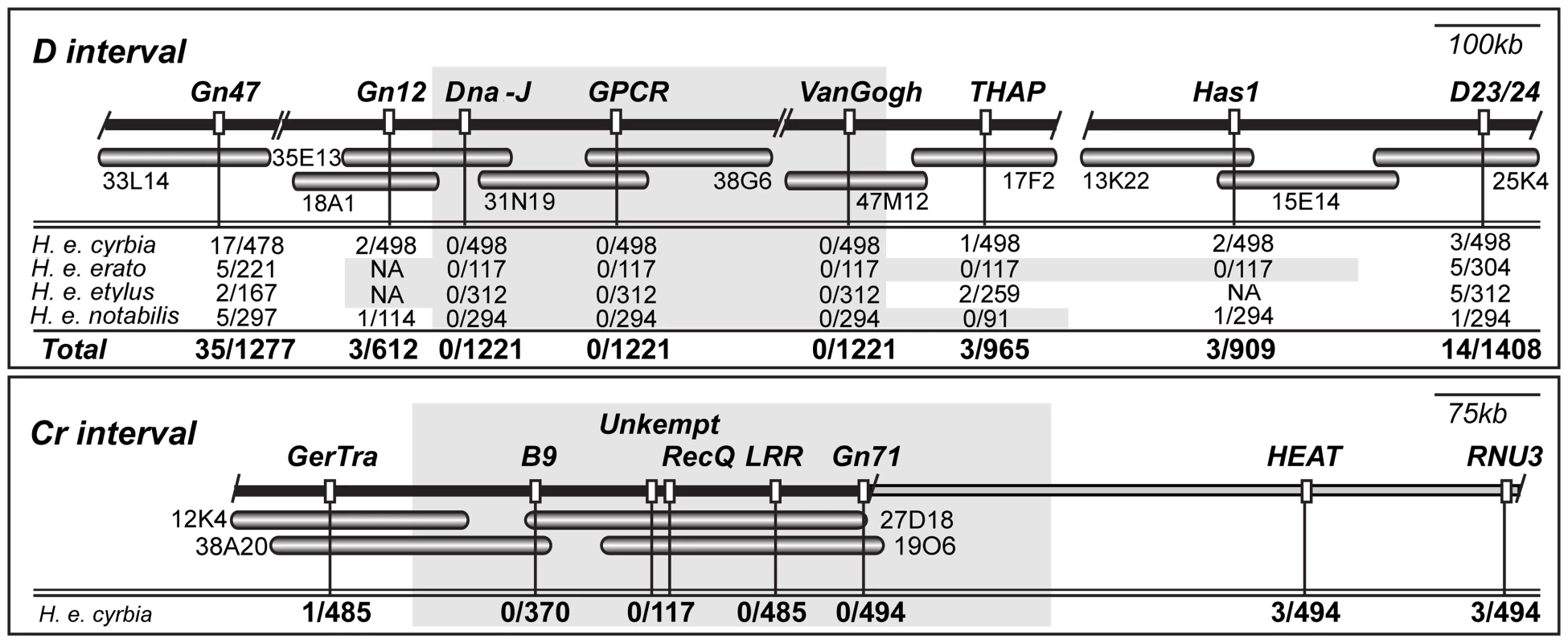

Fine mapping and sequencing of color pattern intervals in H. erato

Building on earlier work, including the initial BAC tile path of H. melpomene D/B locus [31], we sequenced 10 H. erato BACs representing over 1 Mb of genomic sequence around the D locus (Figure 2). Across the D BAC tile path, we surveyed over 1200 individuals from our H. erato x H. himera F2 and backcross mapping families at several molecular markers, and identified an approximately 380 kb interval between the markers Gn12 and THAP that had no recombination events between color pattern phenotype and genotype (shaded region on Figure 2). The lack of recombinants across this zero recombinant window stood in marked contrast to the pattern observed at both the 5′ - and 3′-end of our tile path. At both ends of the region, the number of individuals showing a recombinant event between a genetic marker and color pattern phenotype was similar to the expected 276 kb/cM based on previous mapping work [39], but then dropped off rapidly in the centre of the region. The drop off was particularly marked on the 5′end of the interval, where the number of recombinant events fell from 35 individuals at GN47 to 0 individuals at Dna-J over a span of approximately 200 kb.

Fig. 2. BAC tile paths and fine mapping across the D and Cr color pattern intervals.

Individual BAC clones tiling across the color pattern intervals are represented by horizontal shaded bars, with clone name provided directly below. Black horizontal bar above BAC tile path represents consensus sequence assembled from overlapping BACs. Slashes indicate gaps in the consensus sequence across the interval. There were two small gaps (≈10kb between H. erato clone 33L14 and 18A1 and ≈5kb between 38G06 and 47M12) and one large gap (≈250 kb) in our assembly based on comparisons to Bombyx mori and H. melpomene. For the Cr interval, the grey horizontal bar extending to the right of the black horizontal bar represents a region with no available information on recombination. Vertical white markers denote approximate positions of genetic markers used for brood mapping, with marker names stated directly above. Below each marker is the number of individuals showing a recombination event between the genetic marker and color pattern phenotype over the total number of individuals genotyped. For the D locus, four phenotypically distinct races of H. erato were used for fine mapping in crosses with H. himera [39],[100],and the results for each race are provided separately. Genetic markers designated NA were either not polymorphic or could not be reliably scored in the corresponding crosses. Shaded areas denote approximate locations of ‘zero recombinant intervals’. We also identified the genomic interval containing the Cr locus, although in this case, we do not yet have a BAC tile path across the entire interval. The 5′-end of Cr interval is marked by the locus GerTra, where we identified a single recombinant among nearly 500 H. erato cyrbia x H. himera F2 and backcross individuals. At the 3′-end, we observed 3 Cr recombinants at HEAT, which is about 600 kb from GerTra based on comparisons to the Bombyx mori genome (Figure 2). We sequenced three new BAC clones yielding approximately 420kb of sequence at the 5′-end of the Cr interval. Across our physical sequence of the Cr interval, we found no recombinant individuals at markers 3′ of GerTra (B9, recQ, Invertase, LRR, and GN 71) a span of approximately 340 kb (Figure 2). Thus, as with the D locus interval, there were fewer recombination events than expected based on previous estimates of the relationship between physical and recombination distance.

Genetic diversity and LD across color pattern intervals

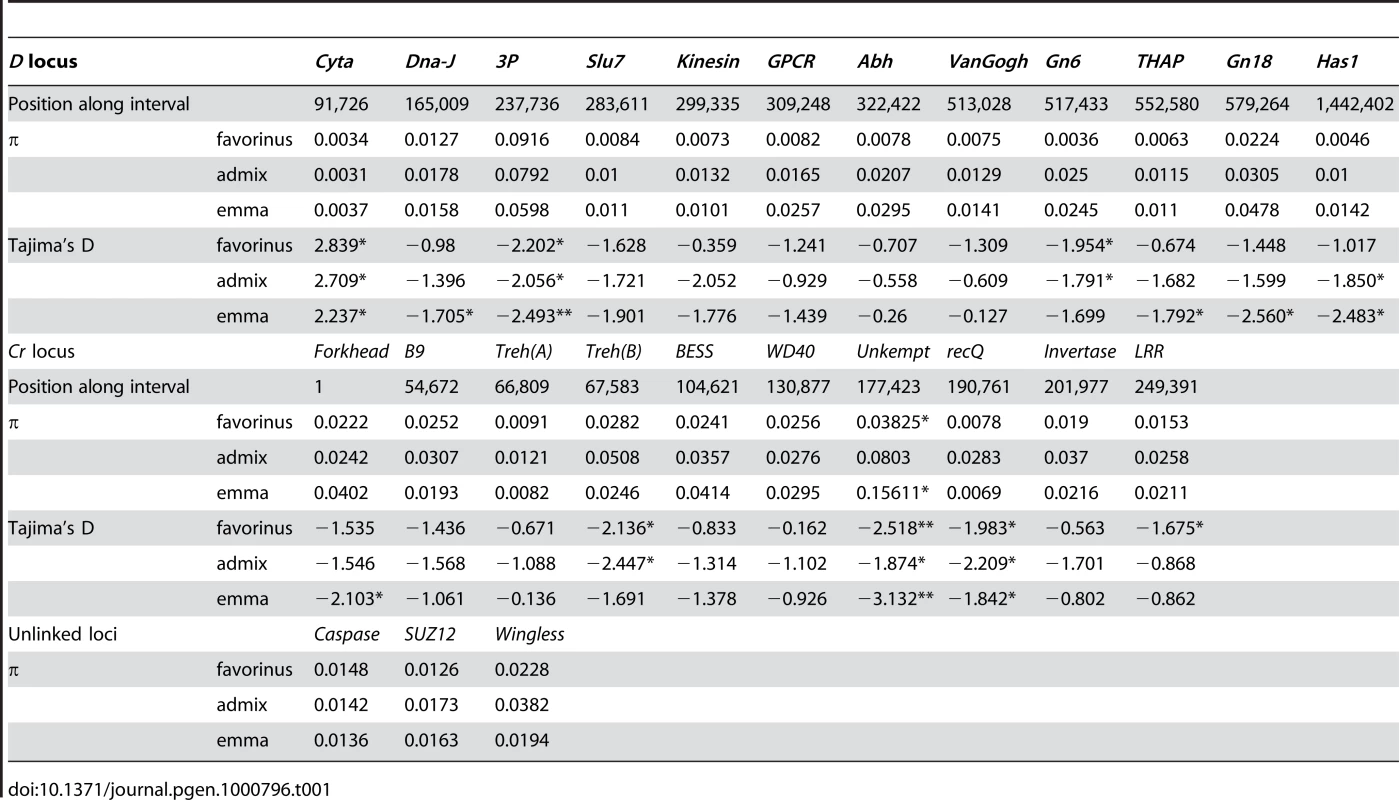

We estimated genetic diversity from 76 individuals collected from five locations along a 30 km transect, representing three distinct populations, phenotypically pure H. e. favorinus (n = 20), admixed individuals (n = 42), and largely pure H. e. emma (n = 14) (Figure 1). In total, we assayed variation across 12,660 bp from 25 coding regions including 13 regions from the D interval, 10 from the Cr interval, and 3 unlinked to each other or any color pattern locus in H. erato (Table S1). There were 1542 polymorphic sites among the sampled individuals. Most of these (1110) positions had minor allele frequencies of less than 5 percent. Of the remaining 432 polymorphic sites, ten had more than two variant bases.

The mean nucleotide diversity (π, average number of pair-wise differences between sequences) among all sampled gene regions in H. erato was 0.022±0.017. In general, there were no strong differences in nucleotide diversity among loci tightly linked to color pattern genes relative to loci unlinked to color pattern (Table 1). Nucleotide diversity was also very similar among the three sampled H. erato populations, except for a few gene regions at the Cr locus in the admixed population that showed slightly elevated estimates of nucleotide diversity (Table 1). Over half the coding regions sampled in this study had patterns of nucleotide diversity not consistent with simulations of neutral evolution, in at least one of the three populations sampled. Near the D locus, many coding regions had negative Tajima's D values that were significantly different from neutral expectation (Table 1). However, there seemed to be little pattern to these departures from neutrality. For example, the coding regions at the D locus most strongly associated with color pattern variation (see below) all showed patterns consistent with the neutral model. In contrast, at the Cr locus, the two coding regions with associated SNPs accounted for about half of the significant deviations from neutrality in genes across this region (Table S1). We also observed significant deviations from neutrality at loci unlinked to color pattern variation. In particular, the Heliconius wingless homologue deviated in all three populations examined (Table S1). Overall nucleotide diversity was generally greater in the H. erato (mean π = 0.022±0.017) than in H. melpomene (mean π = 0.012±0.019, [33]) but the differences were much less than previously reported for nuclear introns [27]. Moreover, in H .melpomene, as in H. erato, there were no striking differences in diversity between loci within and outside of color pattern intervals, nor consistent departures from neutrality within color pattern intervals.

Tab. 1. Estimates of genetic diversity across the <i>H. erato</i> hybrid zone.

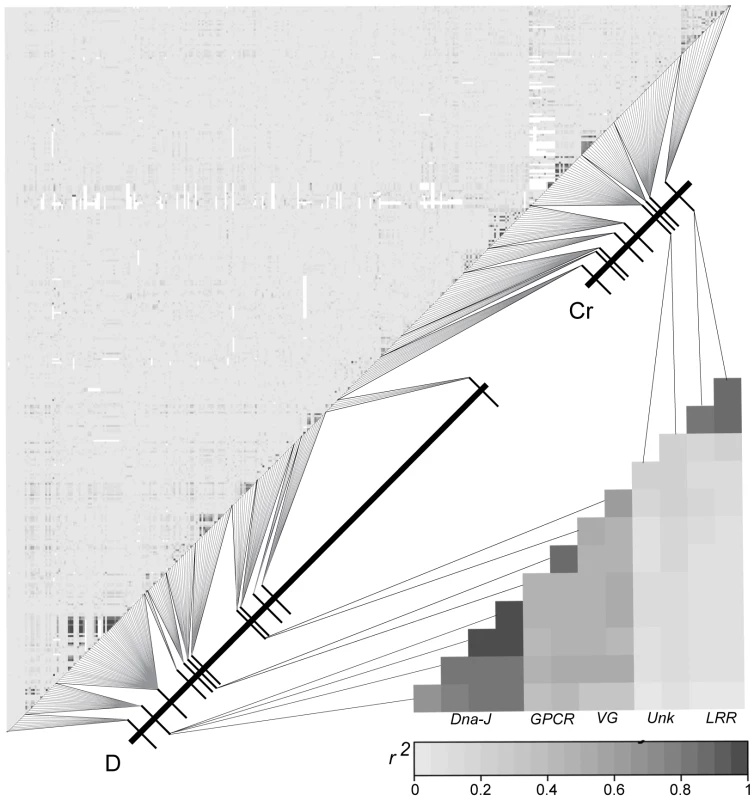

Linkage disequilibrium among SNPs decayed precipitously with physical distance across both the D and Cr intervals (Figure 3 and Figure S2). This observation was true for phenotypically pure populations collected at either side of the sharp phenotypic transition (Figure S1), for “admixed” populations in the center of the transition zone (Figure S1), and even for the population as a whole (Figure 3). The only sites with high estimates of r2 (>0.5) were found within the same coding regions. All other estimates of r2 were near zero (Figure 3), including values between D and Cr interval SNPs (Figure 3). The lack of strong LD in populations across this phenotypic boundary was perhaps best exemplified by the LD patterns within loci - for all loci, including those that fell within our zero recombinant windows, short-range LD decayed to r2 values near zero within 300–500 bp. Although broadly similar, the pattern of LD differed from what was observed in H. melpomene (see [33] Figure S2), where LD generally extended farther and there was some evidence for significant haplotype structure and long-distance LD among sites.

Fig. 3. Lack of LD between SNPs across the D and Cr intervals in the Peruvian hybrid zone.

Correlation matrix of composite LD estimates among SNPs from the 22 coding regions sampled across the D and Cr intervals using all 76 individuals. SNPs are concatenated by their position along the D and Cr intervals. The upper left matrix shows LD between the 401 SNPs sampled across the D and Cr intervals. The lower right matrix only shows SNPs from the D and Cr intervals that are strongly associated with wing color pattern. Genotype-by-phenotype associations

D locus associations

Within the backdrop of the rapid decay of LD, we identified strong genotype-by-phenotype associations at a number of positions across both the D and Cr intervals. Although there were no fixed differences between races, we identified strong associations between SNP variants and the D phenotype in three coding regions, we termed Dna-J, GPCR, and VanGogh (Figure 4). The three coding regions fell within a ∼380 kb interval that correlated perfectly with the zero recombinant window identified in our linkage analysis (see Figure 2). Each of the regions had between 2–5 significantly associated sites as well as SNPs that showed no association interspersed across the coding regions (see Table S2 for complete list of the genotype-by-phenotype associations). The associations at each of these three coding regions was primarily driven by nucleotides that were nearly fixed in individuals homozygous for the H. e. emma D phenotype. The strongest associations were among SNPs at Dna-J, including three synonymous substitutions and two non-synonymous substitutions that resulted in an isoleucine/valine polymorphism at positions 73,699 and 73,753. In both cases, valine was strongly associated with H. e. emma D color pattern. At GPCR there were two synonymous substitutions strongly associated with D phenotype. At VanGogh there was one synonymous substitution and one non-synonymous substitution strongly associated with the D phenotype.

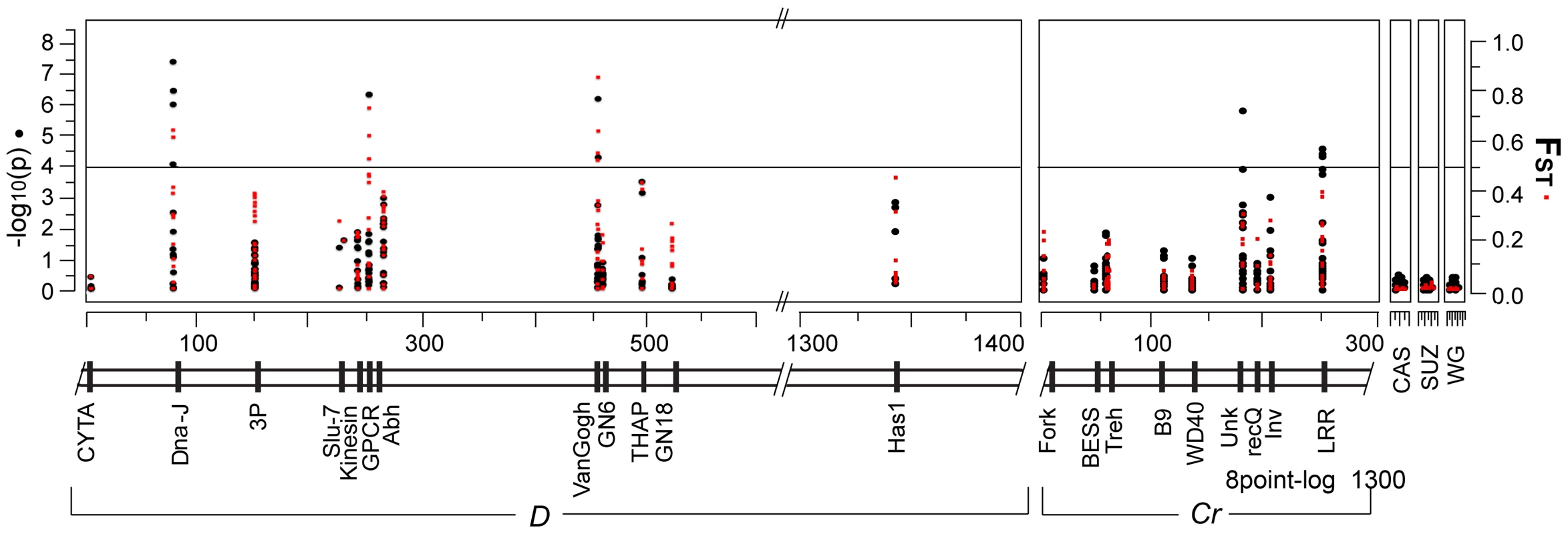

Fig. 4. Several sites in multiple coding regions are associated with the transition in D and Cr color patterns.

Plot of genotype-phenotype associations (black circles) and population differentiation (red squares) across the D, Cr and unlinked intervals. The left axis is the strength of associations (log10 of the probability of a genotype-by-phenotype association) between genotypes and color patterns. The right axis measures degree of population differentiation, measured as FST, between H. e. favorinus and H. e. emma. Distance across the genomic intervals is in kilobases. Points above the horizontal show a significant genotype-by-phenotype association using a bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple tests (α = 0.05, n = 432). In general, estimated levels of differentiation among populations were very similar to the association results - loci that had strongly associated sites also had high FST values. These patterns of genotype-by-phenotype association and population differentiation stand in marked contrast to observations at unlinked loci and loci that fell outside the zero recombinant window. The average FST between the pure H. e. favorinus and pure H. e. emma populations was over 2-fold greater for the coding regions strongly associated with the D phenotype (0.34), relative to the other coding regions within the D zero recombinant window that did not show significant associations (0.16, see Figure 2 and Table S2). Outside the zero recombinant window, levels of population differentiation were lower than inside, but remained higher than levels observed in unlinked loci (Figure 4 and Table S2).

Cr locus associations

The strength of associations and estimates of population differentiation were lower across the Cr interval relative to the D interval. Only two of the 9 genes sampled contained SNPs significantly associated with the Cr phenotype: one gene being a coding region with high sequence similarity to the Drosophila transcription factor Unkempt and the other gene being a coding region with a leucine-rich (LRR) protein motif. These two regions were separated by approximately 80 kb and, similar to the pattern in the D interval, were separated from each other by loci that contained no SNPs associated with color pattern (Figure 4). Also similar to the D locus, associated sites in the same gene were often interspersed by SNPs that showed no association. Three out of the four strongly associated SNPs across the Cr pattern intervals were non-synonymous substitutions. Across the Cr interval the average FST among sampled coding regions between the two phenotypically pure populations was 0.035, or approximately 8 times lower than the average FST across the D interval (Table 2). Even the two loci that contained sites significantly associated with color pattern phenotype showed only a moderate degree of population differentiation (average FST = 0.145 for LRR and average FST = 0.021 for Unkempt) between the phenotypically pure populations sampled in this study (Figure 4, Table S2).

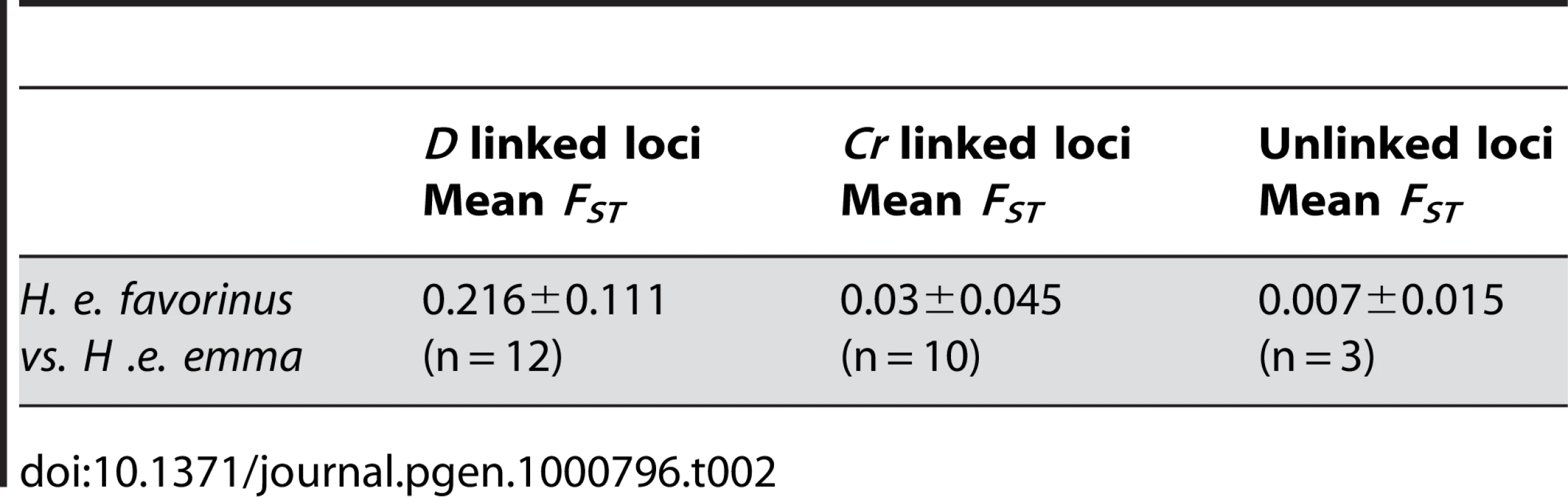

Tab. 2. High genetic differentiation near color pattern loci.

LD between associated SNPs

In general, associated SNPs within each color pattern interval were in higher LD than unassociated sites, but they showed a similar rapid decay with distance (see Figure 3 and Figure S2). Thus, while LD between associated SNPs in the same coding regions could be strong, LD between associated SNPs from different coding regions was considerably lower (Figure 3). There was no LD among associated sites between color pattern intervals. Finer examination revealed a complex haplotype structure, where different sets of individuals had genotypes associated with a color pattern phenotype at each of the associated SNPs, resulting from several recombination events between the different associated sites. As a result, there was no obvious haplotype structure that could explain color pattern phenotype.

Expression analysis of candidate genes

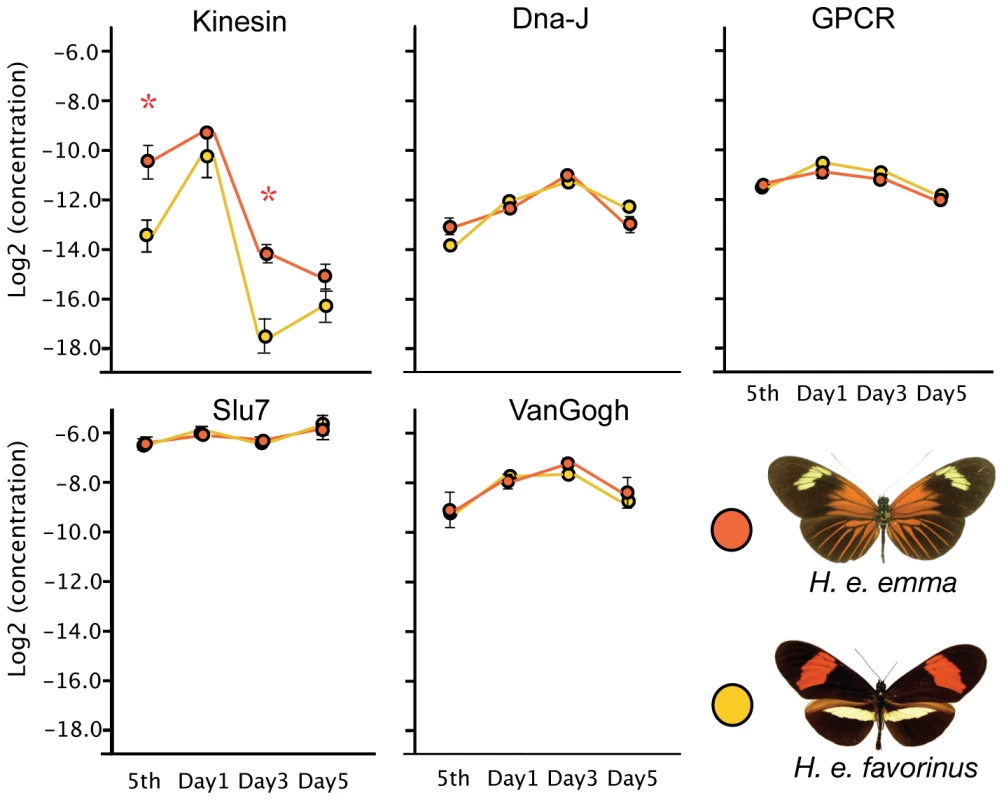

None of the SNPs in this study had a fixed association with color pattern, suggesting that, while the site is strongly associated with color pattern, they are not the functional variants themselves. However, the obvious implication is that they are near the functional site, which could be in cis-regulatory regions that act by causing differences in gene expression. To test this possibility, we compared overall transcription levels between the two races during the early stages of wing development (5th larval instar and 1, 3, and 5 days after pupation), on genes at the D locus that had SNPs strongly associated with wing pattern phenotype either in H. erato or H. melpomene [33]. All genes, with the exception of Slu7, showed significant differences in expression across wing developmental stages (ANOVA: p<0.0001 to 0.0066; Bayesian Model Averaging: Pr(β ≠ 0) = 100 for each gene) (Figure 5). Kinesin, however, was the only candidate gene to show significant differences in expression between H. e. emma and H. e. favorinus (overall race effect p = 0.0001). Expression of this gene was roughly 8× higher in H. e. emma in 5th instar larvae (p = 0.0028, t-test) and three days after pupation (p = 0.0014, t-test), than in H. e. favorinus. As with the ANOVA, statistical testing using Bayesian Model Averaging assigned strong probabilities to racial differences only with Kinesin (Pr(β≠0) >92.5), although a small race effect is predicted for GPCR (Pr(β≠0) >54.7; higher in H. e. favorinus).

Fig. 5. Quantitative PCR of D-interval candidate genes implicates kinesin.

Quantitative PCR data for five candidate genes in the D-interval. Y-axis values are Log2 transformed values of the initial concentration of the gene divided by the EF-1α initial concentration; developmental stage is displayed on the X axis, including 5th instar larvae and pupal developmental days 1, 3, and 5. Bars represent standard error among the biological replicates. Discussion

The genomic regions that underlie pattern variation in Heliconius are “hotspots” of phenotypic evolution [13]. They underlie adaptive variation among races and species with both convergent and highly divergent wing patterns [29]–[31] and play an important role in speciation [16]–[18]. This study, together with the companion study [33], provides the first descriptions of the patterns of nucleotide diversity, LD, and gene expression across these evolutionary important genomic intervals. Our data highlight a complex history of recombination and gene flow across a sharp phenotypic boundary in H. erato that both reshapes our ideas about molecular basis of phenotypic change and focuses future research on a small set of candidate genes that are likely responsible for phenotypic variation in this extraordinary adaptive radiation.

No molecular signature of recent, strong selection on color patterns

The genetic patterns that we observed are inconsistent with the evolution of novel wing patterns in H. erato via a very recent strong selective sweep on a new mutation or recent genetic bottleneck as have been proposed [41]. A selective sweep on a new adaptive variant, which quickly fixes beneficial alleles, is expected to generate a temporary genomic signature marked by a reduction of nucleotide variation and an increase in LD around selected sites as a result of genetic hitchhiking [42]. Empirically, these patterns have been observed around loci important in domestication (e.g. rice [43] and dogs [44],[45]), plant cultivation (sunflowers [46] and maize [47]), drug resistance (Plasmodium, [48]), and the colonization of new environments in the last 10,000 years (sticklebacks, [49]–[51]). In all cases, selection has been strong, directional, and very recent.

The genetic patterns across regions responsible for phenotypic variation in H. erato and H. melpomene serves as a cautionary note and may be more typical of the functional variation found in nature. In H. erato, per locus selection coefficients are high [34],[35]; yet, we see neither a strong reduction in genetic diversity nor extended LD across color pattern intervals. There are loci with nucleotide diversity patterns that deviate significantly from the neutral expectations, but not in a manner consistent with a recent, strong selective sweep acting on a new mutation. In all three loci in the D interval with the strongest association with color pattern, the patterns of nucleotide variation were largely consistent with neutrality (Table 1). Thus, recombination has essentially reduced the signature of selection to very narrow regions tightly linked to the sites controlling the adaptive color pattern variation. This pattern is consistent with the hypothesis that pattern diversification in H. erato is quite ancient, dating perhaps into the Pliocene (see [27]). Interestingly, we see a very similar pattern in H. melpomene, which likely radiated much more recently [27]. Alternatively, the patterns in both H. erato and H. melpomene could also be the result of a recent “soft sweep”, where selection acts on pre-existing variation [52],[53]. Thus, the allelic variants modulating particular color pattern elements are themselves old but the combination of patterning loci that characterize specific wing pattern phenotypes might have evolved much more recently [54],[55]. Under either scenario, however, the observed patterns in both H. erato and H. melpomene highlight the extent with which recombination can erase the signature of strong selection in natural populations [56].

The rapid decay of LD across both H. erato color pattern intervals marks a history of considerable recombination. Narrow hybrid zones between differently adapted populations are common in nature [32]. Hybrid individuals are frequently less fit than parental genotypes and these zones are typically envisioned as “population sinks” that are maintained by the movements of individuals from outside [32],[57],[58]. As a result, hybrid zones tend to show LD even among unlinked loci [59]–[62]. Instead of a population sink, the narrow transition zone between H. e. favorinus and H. e. emma can be more appropriately viewed as a population sieve - where population sizes have remained large, where recombination breaks down associations among alleles even at tightly linked loci, and gene flow allows most of the genome to be freely exchanged between the divergent races. Mallet observed similarly low population differentiation across this cline at 14 unlinked allozyme loci (average FST = 0.038, unpublished data). Indeed, there is very little evidence for extended LD around loci that are responsible for adaptive differences in wing pattern and only slight genetic divergence between H. e. emma and H. e. favorinus at most of 25 coding regions examined within the two color pattern intervals (Figure 4). The only exceptions are regions tightly linked to the sites controlling the color variation, and, even here, LD decays rapidly with physical distance and estimates of FST become moderate, albeit higher than at unlinked loci (see Table 2 and Table S2). The decay in LD in H. erato occurs faster than in H. melpomene, where there is evidence for strong LD (r2>>0.5) extending hundreds of kilobases across the B and Yb color pattern intervals [33]. Nonetheless, in both co-mimics, LD decays much more rapidly than has been reported near adaptive loci in sympatric host races of the pea aphid, Acrythosiphon pisum [63] and sympatric populations of lake whitefish, Coregonus sp. [64]. In the pea aphid study in particular, Via & West [63] showed that strong LD and strong genetic differentiation around the genomic intervals that underlie variation in ecologically important traits extends tens of centimorgans, presumably representing several Mbp at least. This is probably due to lower rates of cross-mating and geneflow, coupled with the largely non-recombinogenic reproduction in the pea aphid throughout most of the year. Our results are more similar to those found between M and S forms of Anopheles gambiae, where a few tens of genes around the centromeres and telomeres are the only regions with strong divergence [65]. Although in this case, the evolutionary or ecological forces driving these differences are largely unknown.

The power of association mapping—localizing candidate regions underlying phenotypic variation

The observation that LD in H. erato populations around ecologically important traits decays at a rate more similar to Drosophila than pea aphids or mammals [63], [66]–[68] has important practical ramifications. Foremost, it means that naturally occurring Heliconius hybrid zones can be used to localize genomic regions responsible for adaptive differences in wing coloration at an extremely fine scale. On average there are informative polymorphic sites (with a minor allele frequency greater than 5%) every 30 bp within coding regions in our data on H. erato. Given this, along with the observed pattern of LD, surveying polymorphism every 200–500 bp should be sufficient to capture haplotype structure across the Peruvian hybrid zone and to finely localize genomic regions responsible for pattern variation in H. erato.

Even with our current coarse sampling, we were able to greatly narrow the candidate D and Cr intervals and focus research on a small set of candidate genes. Across the D interval, there are strong genotype-by-phenotype associations and high levels of genetic differentiation between phenotypically pure populations in three dispersed coding regions: Dna-J, GPCR, and VanGogh. Although several genes near these association peaks have strong sequence similarity to Drosophila genes with known molecular or biological functions that make them candidates for color pattern genes, only one, kinesin, showed strong expression differences between H. e. emma and H. e. favorinus (Figure 5) during early wing development. Kinesin proteins are known to play a role in pattern specification at a cellular level in Drosophila [69] and are involved in vertebrate [70] and invertebrate pigmentation [71]. We expect patterning loci to act as “switches” between different morphological trajectories and for the genes involved to show distinctive spatial/temporal shifts in expression patterns similar to what we observed in kinesin. Although future expression and functional validation is needed, we observed similar expression shifts in the H. melpomene kinesin [33], which further implicates this gene as playing a causal role in pattern variation in Heliconius and provides convincing evidence that parallel changes in gene regulation underlies the independent origins of these co-mimetic lineages.

Across the Cr interval, the two coding regions with the strongest associations, consist of a gene with strong homology to the Drosophila gene Unkempt, and another predicted gene with a leucine-rich repeat (LRR). These loci are approximately 80 kb apart. The H. erato Unkempt codes for the type of protein potentially involved in pattern generation. It contains a zinc-finger binding motif and is potentially a signaling molecule that can regulate the downstream expression of other genes. Indeed, the Drosophila Unkempt is involved in a number of developmental processes including wing and bristle morphogenesis [72]. The role of Unkempt in bristle morphogenesis is particularly intriguing, as the overlapping scales that color a butterfly wing are thought to have evolved from wing bristles [73]. Moreover, the different color scales in Heliconius have unique morphologies and are pigmented at different times during wing development [74], suggesting that pattern variation may be tied directly to scale maturation. If Unkempt is shown by additional research to be modulating pattern variation, it could provide yet another example of a conserved developmental gene co-opted to produce novel variation [75]–[77]. Alternatively, it may turn out that the gene that underlies pattern variation in Heliconius is either Lepidoptera-specific or has diverged significantly in both form and function from other insect lineages. LRR has no strong ortholog in Drosophila, the honeybee (Apis mellifera), or the flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum). It is most similar to the Drosophila gene, Sur-8, which is inferred to have RAS GTPase binding activity. This suggests it may be involved in signal transduction. This gene also showed the highest differentiation among H. melpomene races and between H. melpomene and H. cydno [33], further implicating this gene and the surrounding regions.

Three unlinked genomic intervals, D, Cr and Sd, interact to generate the phenotypic differences between H. e. favorinus and H. e. emma [40]. Yet, the overall effect on phenotype of variation across each of these loci is not identical and the much lower levels of population differentiation in the Cr interval relative to the D interval is likely due a combination of differences in dominance and selection on the two loci. In H. erato, there is a strong dominance hierarchy among the colored scale cells, where red scale cells (containing xanthommatin and dihydro-xanthommatin) are dominant to black (containing melanin) scale cells and both are dominant to yellow (containing 3-hydroxy-L-kynurenine) scale cells. For H. e. emma and H. e. favorinus this means that the D locus is effectively codominant, whereas the Cr allele for the emma lack of hindwing bar is dominant to presence of yellow hindwing bar in favorinus [40]. Additionally, the analysis of cline width, together with the overall percentage of wing surface affected suggests that the selection on the codominant D locus is much higher (s≈0.33) than selection on the dominant Cr locus (s≈0.15) [23],[34]. Thus, the power of natural selection to remove poorly adapted alleles at Cr is reduced, especially on the H. e. emma side of the zone where the recessive yellow bar alleles are rare [34]. In H. melpomene the Yb and B locus are homologous to the H. erato Cr and D loci, respectively, and are under similar selective constraints at this Peruvian hybrid zone. Similarly, a reduction in the power of natural selection on the Cr would likely result in a similar reduction of selection on Yb, which may explain why genetic differentiation between the H. melpomene Peruvian races is, like H. erato, much lower at genes near the Yb relative to the B locus (see [33], Table 1). Given the history of recombination implied by our data, we expect only sites extraordinarily tightly linked to the causative polymorphisms to yield strong associations. Collectively the association results across the D and Cr intervals highlight the power of using these naturally occurring hybrid zones to select candidate loci for future focused studies. Similar and possibly independently derived transitions between “postman” and “rayed” races of H. erato and H. melpomene that occur in Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Suriname, and French Guiana, provide additional replicates to test the repeatability of evolution [19]–[21],[78],[79].

The locus of evolution

The color pattern genes of Heliconius are classical examples of large effect loci where allelic variation causes major phenotypic shifts in the distribution of melanin and ommochrome pigments across large sections of both the fore - and hindwing. We are accustomed to thinking of the generation of phenotypic variation in terms of single causal mutations. This paradigm has shaped our ideas about how variation is produced by DNA sequences, and, although consistent with some of the handful of examples [2],[5],[80], there are reasons to imagine this is not the whole story, or even a dominant trend [75],[77],[81],[82].

In this light, the varying pattern of LD across the D and Cr intervals and the observation that different polymorphic sites are associated with pattern phenotype in different sets of individuals seems inconsistent with a single causal functional site. Our coarse sampling provides only a preliminary snapshot of haplotype structure across these intervals and genetic hitching, drift and ancestry can create complex genotype-by-phenotype signatures [83]–[86]. Nonetheless, given the rapid breakdown of LD observed, we would expect to see a much narrower window of association if variation was explained by a single causal site. However, the pattern we observe is expected if there are multiple functional sites dispersed across these intervals. Although LD was generally higher, a similar pattern was evident in H. melpomene [33]. These emerging genetic signatures are consistent with early ideas that these patterning loci were “supergenes” composed of a cluster of tightly linked loci [21]. For example, in H. erato the D locus was originally described as three unique loci, D, R, and Y [21] and there has been one H. erato individual collected in the Peruvian hybrid zone which had a DR/y recombinant phenotype [40]. In H. melpomene both the B and Yb loci, have roughly equivalent phenotypic effects as the D and Cr loci in H. erato, and have been clearly shown to be parts of tightly linked clusters of loci that control the end wing pattern phenotype. It is possible that these “clusters” are a series of enhancer elements that influence target gene expression and the terminal phenotype in an overall switch-like fashion [87]. Selection to maintain these clusters may explain the reduced recombination rate we observed across color pattern intervals in the pedigree-based linkage mapping of the D and Cr intervals and the large haplotype blocks across the Yb and B intervals in the Peruvian H. melpomene races [33]. However, in H. erato thousands of generations of hybridization in the middle of the hybrid zone may have allowed recombination to break apart functional sites, creating the mosaic of different haplotypes we observed across these intervals. Collectively, these two companion studies serve as natural replicates of how convergence on a similar adaptive trait can be independently derived and provide compelling evidence that similar genetic changes can underlie the evolution of Müllerian mimicry.

Our initial sampling of genetic variation across the color pattern loci provides important insights into the complex haplotype structure that potentially underlies the major phenotypic shifts in wing color patterns. These data suggest that finer genetic dissection of these hybrid zones and other parallel transitions will allow direct tests of the number and type of changes that underlie adaptive color pattern variation in Heliconius. These studies will help pinpoint functionally important polymorphisms and determine if a single functional site or multiple sites underlies adaptive color pattern variation and if these sites are changes in coding regions, in cis-regulatory regions, or both. Ultimately, linking the genetic changes underlying phenotypic variation with the development pathways involved in patterning the wing promises a whole new understanding of how morphological variation is created through development and modified by natural selection within the context of an adaptive radiation.

Methods

We generated several F2 and backcross mapping families by crossing four different geographic races of H. erato to the same stock of H. himera. All crosses were carried out in the Heliconius insectaries at the University of Puerto Rico from stocks originally collected in the wild under permit from the Ministerio del Ambiente in Ecuador. We followed segregating variation at the D locus in the crosses involving H. e. cyrbia, H. e. erato, H. e. etylus and H. e. notabilis. We were also able to follow segregating variation for the Cr locus in crosses between H. himera and H. e. cyrbia. After eclosion, individuals were euthanized, had their wings removed for later morphological analysis, and their bodies were stored in DMSO at −80°C.

Genomic DNA was extracted from 1/3 of preserved thoracic tissue for each individual using Plant DNeasy Tissue kit (Qiagen Inc). Across the D interval, segregating variation was followed for one microsattelite and seven gene-based markers and for seven gene based markers across the Cr interval. The markers D23/24 and GerTra were screened using the methods described in [29],[88]. All other gene-based markers were PCR amplified, the PCR product was purified Using ExoSAP-IT (USB), and sequenced in both directions using Big Dye Terminator v3.1 and run on a 3700 DNA Sequence Analyzer (Applied BioSystems). Due to an indel polymorphism at Gn47 some samples could be sequenced in the forward direction for Gn47. To overcome this, individuals identified as recombinants at Gn47 (see below) were PCR amplified and sequenced twice to confirm individual genotypes. For gene-based markers, primers were designed from available H. erato and/or H. melpomene BAC sequences, Table S1 provides the primer sequences, PCR conditions, and marker types. Sites and/or insertion/deletions that varied between the parents of a mapping family were screened among the offspring of those mapping families. To determine the distance between each marker and a color pattern locus, we looked for evidence of recombination between the genotype at each marker and the wing pattern phenotype. The greater the number of individuals showing a recombination event between a marker genotype and the color pattern phenotype, the further that specific marker was from the functional site(s) controlling the color pattern variation. For the D locus, the markers Gn12, VanGogh and THAP were only screened for a ‘recombinant panel’ of individuals. The recombinant panel consisted of all individuals identified as recombinants at markers Gn47 and D23/24, six individuals from each mapping that were not recombinants at Gn47 and D23/24 and the parents of each mapping family. This method dramatically reduced the number of individuals screened and allowed us to efficiently determine the number of single recombination events between each marker and the D locus.

Targeted BAC sequencing

We screened the H. erato BAC libraries, to identify BAC clones that spanned the D and Cr color pattern intervals. For the Cr locus, probes were designed from the previously published H. erato BAC clone 38A20 (AC193804) and H. melpomene BAC clones 11J7 (CU367882), 7G12, (CT955980) and 41C10 (CR974474) [29],[88]. Across the D locus, probes were designed from the H. erato BAC clone 25K04 (AC216670) and H. melpomene BAC clones 7G5 (CU462858) 27I5 (CU467807), and 28L23 (CU467808) that have been previously shown to be located near the D locus [31]. BAC library probing, fingerprinting of positively identified clones, and the sequencing and assembly of BAC clones that most extended our tiling coverage was done using the methods described in [88]. BAC clone sequences were aligned using SLAGAN [89] to create contiguous H. erato consensus sequences across the D and Cr color pattern loci. SLAGAN was also used to align these H. erato consensus sequences with available H. melpomene BAC sequences and Bombyx mori genome sequence to confirm the order, orientation and locations of gaps among the H. erato sequences. The consensus H. erato sequences were then annotated using Kaikogaas (http://kaikogaas.dna.affrc.go.jp), an automated annotation package that implements several gene prediction methods to identify potential coding regions. Locations of predicted coding regions and conserved domains are shown in Figure S2. Primers for probes were designed from potential coding regions using the methods described above, in Butterfly Crosses and Fine-Mapping. Primer sequences and PCR conditions for probes are available in Table S1.

Population sampling

Individuals used in this study were collected from five locations transecting 32 km across a H. erato hybrid zone in Eastern Peru near Tarapoto. In total we sampled 76 individuals, 20 from phenotypically “pure” populations of H. e. favorinus in Tarapoto and Rio Pansillo, 14 individuals from a primarily phenotypically “pure” population of H. e. emma in Davidcillo, and 42 from admixed populations in Pongo de Cainarache and Barranquitas located near the center of the hybrid zone. Due to dominance and strong epistasis between the three loci, when individuals have a DemmaDemma genotype, the CremmaCremma and CremmaCrfav genotypes are phenotypically indistinguishable. Therefore some individuals were assigned a Cremma- dominant genotype (see [34]), indicating the genotype of the second Cr allele is unknown. Individual's names, sex, race, color pattern genotype and collection location are recorded in Table S4.

Genomic sampling

Nucleotide variation was sampled across two candidate intervals controlling major changes in warning color patterns, as well as three other autosomal genes unlinked to color pattern. We sampled twelve coding regions from D interval, ten from the Cr interval, and three coding regions from genes on unlinked chromosomes (Table S1). Names of coding regions are based on sequence homology to annotated genes in other organisms, or if no sequence homology was found numbered gene names were assigned. On average, 520 bp fragments were sampled every 47 kb across a candidate color pattern interval. Primer design for PCR amplification and sequencing was done using Primer3 [90]. Primers for the three unlinked loci were developed by Pringle et al. [91], and have been shown to map to different linkage groups in H. melpomene. Primer sequences and PCR conditions for each locus can be found in Table S1. Genomic DNA extraction, PCR product purification and sequencing were completed using the same methods as described above. For some individuals, Abhydrolase was cloned from purified PCR product using TOPO cloning kit (Invitrogen) and 4–10 clones were sequenced. Ambiguous bases in the genomic sequences were cleaned and trimmed manually using Sequencher (Gene Codes Corporation). A site was determined to be heterozygous if the lower quality nucleotide had a peak height at least 50% of the higher quality nucleotide. Sequences were initially aligned using Sequencher and the resulting alignments were then manually adjusted.

Genetic diversity analyses

Population genetic estimates of nucleotide diversity, population differentiation and tests of neutrality were conducted using SITES and HKA [92]. Nucleotide diversity was estimated as π (average number of pair-wise differences per base pair) for all samples i) within the H. e. favorinus population ii) within the H. e. emma population and iii) within the admixed population. This was done for each of the 25 sampled coding regions independently and by concatenating all coding regions sampled on the same chromosome (Table S1). Tajima's D [93] was also calculated for all coding regions independently and by concatenating them, to examine for departures from the neutral model of evolution. For each coding region 10,000 coalescent simulations based on locus specific estimates of theta were used to determine if the observed patterns of nucleotide diversity and locus specific estimates of Tajima's D significantly departed from neutral expectations using the program HKA as described in [94]. FST was estimated between the two phenotypically pure populations and the admixed population for each coding region and using SITES (Table 2) and FDIST2 (Table S2) [95].

Linkage disequilibrium

To determine the extent of LD across the candidate color pattern intervals in Heliconius, we computed composite LD estimates for 432 SNPs from the 25 coding regions we sampled. Of the 1542 polymorphic sites identified in this study, 442 sites had a minor allele frequency greater than 0.05 and were considered informative for LD analyses. Multi-allelic sites that had a minor allele with a frequency less than 0.05 were condensed to bi-allelic SNPs by merging the minor allele genotypes. Ten polymorphic sites had 2 or 3 minor alleles with a frequency greater than or equal to 0.05 that were not condensed to bi-allelic SNPs and were not included in the LD analyses. LD between the remaining 432 SNPs was executed using the commonly used composite estimate of LD method described by Weir [96], which does not assume HWE or that haplotypes are known . LD among the 432 SNPs was estimated independently for i) all samples ii) within the H. e. favorinus population iii) within the H. e. emma population and iv) within the admixed population. LD between the 432 SNPs using all sampled individuals was visualized with GOLD [97], by plotting the composite r2 estimates between all pair wise SNP combinations. To visualize the difference in mean r2 between the three populations, a sliding window average of r2 across 50 neighboring SNPs was calculated independently for each population and plotted by distance.

Genotype-by-phenotype association

We determined if any SNP was associated with a color pattern phenotype using chi-squared linear trend test [96]. This test assumes a linear relationship between the phenotype and genotype and applies a chi-square goodness-of-fit test to determine if the genotype at a SNP is significantly associated with a particular wing color pattern. For the association tests we used bi-allelic and multi-allelic SNPs with minor allele frequencies equal to or greater than 0.05. Color pattern phenotypes at the D and Cr loci were scored as 0.0 representing H. e. favorinus phenotypes, 0.5 representing hybrid phenotypes and 1.0 H. e. emma phenotypes. Individuals with H. e. emma D phenotypes and H. e. emma Cr phenotypes were assigned 1.0 for the D phenotype score and 0.5 for the Cr phenotype score, due to the effects of dominance previously mentioned; varying the Cr value for from 0.5 to 1.0 for these individuals had a negligible effect on the association test results (data not shown).

Quantitative examination of gene expression

We used quantitative PCR involving SYBR Green technology to detect transcript levels of kinesin, Slu7, GPCR, Dna-J, and VanGogh in butterfly forewing tissues. Samples of whole forewings were dissected from December, 2008 - February, 2009 from reared H. e. emma and H. e. favorinus stocks founded from multiple individuals collected within 30 km of one another in Peru. We staged individuals indoors at 25°C starting in early 5th larval instar. Chosen larval wings were at mid-5th instar, stage 2.25–2.75 based on the work of Reed and colleagues [98]. Pupal stages were based on the time after the pupal molting event, including Day 1 (24hrs), Day 3 (72hrs), and Day 5 (120hrs). We sampled three individuals of each stage and race, resulting in 2 races × 4 stages × 3 biological replicates = 24 specimens. All specimens were processed randomly from dissection through amplification stages.

We extracted total RNA from the tissues using an electric tissue homogenizer and the RNAqueous Total RNA Isolation Kit (Ambion). This procedure was followed by a TURBO DNA-free (Applied Biosystems) treatment to remove genomic DNA contaminants. Extracted products were run through the Agilent Bioanalyzer to ensure the RNA was of high quality. For cDNA systhesis, 0.4 µg of each sample was added to the standard 20µl reaction procedure outlined in the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Resulting products were diluted with an additional 50µl.

For each gene, we performed quantitative PCR on all 24 samples in triplicate to correct for technical error. We used EF-1α as a standard to normalize the expression of the test genes. Primers for amplification of cDNA were designed using recommended criteria and range from 98 – 175 bp in length (see Table S3). We ran primer sets through an initial qPCR optimization to test for optimal primer concentrations and ran DNA-free controls to test for primer-dimers. qPCR reactions were run using 1µl of 5µM primers (0.5µl for GPCR), 5µl SYBR Green Mix, 1 µl template, and water to 10 µl. Reactions were run in 384-well plates in the Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR machine under standard mode and absolute quantification for 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 60 sec. Each cycle was followed by a dissociation step to measure the dissociation temperature of the sample, which tests for primer-dimer and differences in sequences among samples. A standard curve was generated for each gene using a 10−3 to 10−7 dilution series drawn from a PCR amplified product using the same primers.

To normalize Ct values from the qPCR run, we first calculated the mean of each of the three technical replicates. We then calculated initial concentrations for each sample for each gene given the equation of the standard curve for that gene. These initial concentrations were divided by the inferred concentration of EF-1α for that sample, thus correcting for inconsistencies in initial cDNA sample concentrations. These relative values were then log2 transformed for presentation and analysis. Log2 transformation is necessary to normalize the variances of the samples and represents expression differences in more biologically realistic fold differences. Significance values were obtained from a two-way ANOVA using stage, race, and race*stage as effects. Effects of race within each stage were further dissected for each gene using series of t-tests and an FDR of 0.05 (threshold at p = 0.0028) to correct for multiple testing. In addition to a general ANOVA and to compare our results to the companion paper [33], we used a combination of generalized linear regression models (GLMs) and Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA) on the non-log transformed data to model the effect of race, developmental stage, and their interactions, on gene expression. These statistics were performed using the ‘bic.glm’ function in the ‘BMA’ package [99] implemented in R (R Development Core Team 2008).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. BarrettRDH

SchluterD

2008 Adaptation from standing genetic variation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 23 38 44

2. ColosimoPF

HosemannKE

BalabhadraS

VillarealG

DicksonM

2005 Widespread parallel evolution in sticklebacks by repeated fixation of Ectodyplasin alleles. Science 307 1928 1933

3. WernerJD

BorevitzJO

WarthmannN

TrainerGT

EckerJR

2005 Quantitative trait locus mapping and DNA array hybridization identify an FLM deletion as a cause for natural flowering-time variation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 2460 2465

4. TishkoffSA

ReedFA

RanciaroA

VoightBF

BabbittCC

2007 Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe. Nature Genetics 39–40 31

5. SteinerCC

WeberJN

HoekstraHE

2007 Adaptive variation in beach mice produced by two interacting pigmentation genes. PLoS Biol 5 e219 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050219

6. StorzJF

SabatinoSJ

HoffmannFG

GeringEJ

MoriyamaH

2007 The molecular basis of high-altitude adaptation in deer mice. PLoS Genet 3 e45 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030045

7. FederME

Mitchell-OldsT

2003 Evolutionary and ecological functional genomics. Nature Reviews Genetics 4 649 655

8. JayFS

2005 Using genome scans of DNA polymorphism to infer adaptive population divergence. Molecular Ecology 14 671 688

9. Mitchell-OldsT

SchmittJ

2006 Genetic mechanisms and evolutionary significance of natural variation in Arabidopsis. Nature 441 947

10. StinchcombeJR

HoekstraHE

2007 Combining population genomics and quantitative genetics: finding the genes underlying ecologically important traits. Heredity 100 158 170

11. McMillanWO

MonteiroA

KapanDD

2002 Development and evolution on the wing. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 17 125 133

12. JoronM

JigginsCD

PapanicolaouA

McMillanWO

2006 Heliconius wing patterns: an evo-devo model for understanding phenotypic diversity. Heredity 97 157 167

13. PapaR

MartinA

ReedRD

2008 Genomic hotspots of adaptation in butterfly wing pattern evolution. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development 18 559 564

14. FutuymaDJ

2005 Evolution Sunderland Sinauer Associates, Inc

15. BartonNH

BriggsDEG

EisenJA

GoldsteinDB

PatelNH

2007 Evolution Cold Spring Harbor Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press

16. McMillanWO

JigginsCD

MalletJ

1997 What initiates speciation in passion-vine butterflies? Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America 94 8628 8633

17. JigginsCD

NaisbitRE

CoeRL

MalletJ

2001 Reproductive isolation caused by colour pattern mimicry. Nature 411 302 305

18. KronforstMR

YoungLG

KapanDD

McNeelyC

O'NeillRJ

2006 Linkage of butterfly mate preference and wing color preference cue at the genomic location of wingless. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America 103 6575 6580

19. EmsleyMG

1964 The geographical distribution of the color-pattern components of Heliconius erato and Heliconius melpomene with genetical evidence for the systematic relationship between the two species. Zoologica, NY 245 286

20. TurnerJRG

1975 A tale of two butterflies. Natural History 84 28 37

21. SheppardPM

TurnerJRG

BrownKS

BensonWW

SingerMC

1985 Genetics and the evolution of Müllerian mimicry in Heliconius butterflies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences 308 433 613

22. MalletJ

1993 Speciation, raciation, and colour pattern evolution in Heliconius butterflies: the evidence from hybrid zones.

HarrisonRG

Hybrid Zones and the Evolutionary Process London Oxford University Press 226 260

23. MalletJ

McMillanWO

JigginsCD

1998 Mimicry and warning color at the boundary between microevolution and macroevolution.

HowardD

BerlocherS

Endless Forms: Species and Speciation Oxford Oxford University Press 390 403

24. BeltránM

JigginsCD

BrowerAVZ

BerminghamE

MalletJ

2007 Do pollen feeding, pupal-mating and larval gregariousness have a single origin in Heliconius butterflies? Inferences from multilocus DNA sequence data. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 92 221

25. MalletJ

BeltranM

NeukirchenW

LinaresM

2007 Natural hybridization in heliconiine butterflies: the species boundary as a continuum. BMC Evolutionary Biology 7 28

26. BrowerAVZ

1996 Parallel race formation and the evolution of mimicry in Heliconius butterflies: a phylogenetic hypothesis from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Evolution 50 195 221

27. FlanaganNS

ToblerA

DavisonA

PybusO

PlanasS

2004 Historical demography of Müllerian mimicry in the Neo-tropical Heliconius butterflies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 9704 9709

28. MalletJ

in press Shirft Happens! Evolution of warning colour and mimetic diversity in tropical butterflies. Ecological Entomology

29. JoronM

PapaR

BeltránM

MavárezJ

BerminghamE

2006 A conserved supergene locus controls color pattern convergence and divergence in Heliconius butterflies. PLoS Biol 4 e303 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040303

30. KronforstMR

KapanDD

GilbertLE

2006 Parallel genetic architecture of parallel adaptive radiations in mimetic Heliconius butterflies. Genetics 174 535 539

31. BaxterS

PapaR

ChamberlainN

HumphraySJ

JoronM

2008 Convergent evolution in the genetic basis of Müllerian mimicry in Heliconius butterflies. Genetics 180 1576 1577

32. BartonNH

HewittGM

1989 Adaptation, speciation and hybrid zones. Nature 341 497

33. BaxterSW

NadeauN

MarojaL

WilkinsonP

CountermanBA

2010 Genomic Hotspots for adaptation: populaiton genetics of Mullerian mimicry in the Heliconius melpomene clade. PLoS Genet 6 e794 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000794

34. MalletJ

BartonN

MGL

CJS

MMM

1990 Estimates of selection and gene flow from measures of cline width and linkage disequilibrium in Heliconius hybrid zones. Genetics 124 921 936

35. MalletJ

BartonNH

1989 Strong natural selection in a warning color hybrid zone. Evolution 43 421 431

36. BaxterSW

PapaR

ChamberlainN

HumphraySJ

JoronM

2008 Convergent evolution in the genetic basis of Mullerian mimicry in heliconius butterflies. Genetics 180 1567 1577

37. KapanDD

FlanaganNS

ToblerA

PapaR

ReedRD

2006 Localization of Mullerian mimicry genes on a dense linkage map of Heliconius erato. Genetics genetics.106.057166

38. ToblerA

KapanD

FlanaganNS

GonzalezC

PetersonE

2005 First-generation linkage map of the warningly colored butterfly Heliconius erato. Heredity 94 408 417

39. KapanD

FlanaganN

ToblerA

PapaR

ReedR

2006 Localization of Müllerian mimicry genes on a dense linkage map of Heliconius erato. Genetics 173 735 757

40. MalletJ

1989 The genetics of warning colour in Peruvian hybrid zones of Heliconius erato and H. melpomene. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 236 163 185

41. TurnerJGR

MalletJLB

1997 Did forest islands drive the diversity of warningly coloured butterflies? Biotic drift and the shifting balance. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 351 835 845

42. SmithJM

HaighJ

1974 The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genetical Research 23 23 35

43. CaicedoAL

WilliamsonSH

HernandezRD

BoykoA

Fledel-AlonA

2007 Genome-wide patterns of nucleotide polymorphism in domesticated rice. PLoS Genet 3 e163 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030163

44. CadieuE

NeffMW

QuignonP

WalshK

ChaseK

2009 Coat Variation in the Domestic Dog Is Governed by Variants in Three Genes. Science 326 150 153

45. SutterNB

BustamanteCD

ChaseK

GrayMM

ZhaoK

2007 A single IGF1 allele is a major determinant of small size in dogs. Science 316 112 115

46. ChapmanMA

PashleyCH

WenzlerJ

HvalaJ

TangS

2008 A genomic scan for selection reveals candidates for genes involved in the evolution of cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus). Plant Cell 20 2931 2945

47. PalaisaK

MorganteM

TingeyS

RafalskiA

2004 Long-range patterns of diversity and linkage disequilibrium surrounding the maize Y1 gene are indicative of an asymmetric selective sweep. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 9885 9890

48. MuJ

AwadallaP

DuanJ

McGeeKM

KeeblerJ

2007 Genome-wide variation and identification of vaccine targets in the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Nat Genet 39 126 130

49. CanoJM

MatsubaC

MakinenH

MerilaJ

2006 The utility of QTL-Linked markers to detect selective sweeps in natural populations–a case study of the EDA gene and a linked marker in threespine stickleback. Mol Ecol 15 4613 4621

50. MakinenHS

ShikanoT

CanoJM

MerilaJ

2008 Hitchhiking mapping reveals a candidate genomic region for natural selection in three-spined stickleback chromosome VIII. Genetics 178 453 465

51. MakinenHS

CanoJM

MerilaJ

2008 Identifying footprints of directional and balancing selection in marine and freshwater three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) populations. Molecular Ecology 17 3565 3582

52. BarrettRD

SchluterD

2008 Adaptation from standing genetic variation. Trends Ecol Evol 23 38 44

53. HermissonJ

PenningsPS

2005 Soft sweeps: molecular population genetics of adaptation from standing genetic variation. Genetics 169 2335 2352

54. WittkoppPJ

StewartEE

NeidertAH

HaerumBK

ArnoldLL

2009 Intraspecific polymorphism to interspecific divergence: genetics of pigmentation in Drosophila. Science 540 544

55. GilbertLE

2003 Adaptive novelty through introgression in Heliconius wing patterns: evidence for shared genetic “toolbox” from synthetic hybrid zones and a theory of diversification.

BoggsCL

WattWB

EhrlichPR

Ecology and Evolution Taking Flight: Butterflies as Model Systems Chicago University of Chicago Press 281 318

56. PenningsPS

HermissonJ

2006 Soft sweeps III: the signature of positive selection from recurrent mutation. PLoS Genet 2 e186 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020186

57. BartonNH

2001 The role of hybridization in evolution. Molecular Ecology 10 551 568

58. JigginsCD

MalletJ

2000 Bimodal hybrid zones and speciation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 15 250

59. BartonNH

1982 The structure of the hybrid zone in Uroderma bilobatum (Chiroptera Phyllostomatidae). Evolution 86 863 866

60. GrahameJW

WildingCS

ButlinRK

2006 Adaptation to a steep environmental gradient and an associated barrier to gene exchange in Littorina saxatilis. Evolution 60 268 278

61. TeeterKC

PayseurBA

HarrisLW

BakewellMA

ThibodeauLM

2008 Genome-wide patterns of gene flow across a house mouse hybrid zone. Genome Research 18 67 76

62. SzymuraJM

BartonNH

1991 The genetic structure of the hybrid zone between Bombina bombina and B. variegata: comparisons between transects and between loci. Evolution 45 237 261

63. ViaS

WestJ

2008 The genetic mosaic suggests a new role for hitchhiking in ecological speciation. Mol Ecol 17 4334 4345

64. RogersSM

BernatchezL

2007 The genetic architecture of ecological speciation and the association with signatures of selection in natural lake whitefish (Coregonus sp. Salmonidae)species pairs. Mol Biol Evol 24 1423 1438

65. TurnerTL

HahnMW

NuzhdinSV

2005 Genomic islands of speciation in Anopheles gambiae. PLoS Biol 3 e285 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030285

66. AquadroCF

Bauer DuMontV

ReedFA

2001 Genome-wide variation in the human and fruitfly: a comparison. Curr Opin Genet Dev 11 627 634

67. WallJD

2001 Insights from linked single nucleotide polymorphims: what can we learn from linkage disequlibrium? Current Opinion in Genetics and Development 11

68. ArdlieKG

KruglyakL

SeielstadM

2002 Patterns of linkage disequlibrium in the human genome. Natural Reviews Genetics 3 299 310

69. TekotteH

DavisI

2002 Intracellular mRNA localization: motors move messages. Trends Genet 18 636 642

70. AspengrenS

HedbergD

SkoldHN

WallinM

2009 New insights into melanosome transport in vertebrate pigment cells. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 272 245 302

71. BoyleRT

McNamaraJC

2006 Association of kinesin and myosin with pigment granules in crustacean chromatophores. Pigment Cell Res 19 68 75

72. MohlerJ

WeissN

MurliS

MohammadiS

VaniK

1992 The embryonically active gene, unkempt, of Drosophila encodes a Cys(3)His finger protein. Genetics 131 377 388

73. GalantR

SkeathJB

PaddockS

LewisDL

CarrollSB

1998 Expression pattern of a butterfly acheate-scute homolog reveals the homology of butterfly wing scales and insect sensory bristles. Current Biology 8 807 813

74. GilbertLE

ForrestHS

SchultzTD

HarveyDJ

1988 Correlations of ultrastructural and pigmentation suggest how genes control development of wing scales on Heliconius butterflies. Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 26 141 160

75. CarrollSB

2008 Evo-Devo and an expanding evolutionary synthesis: a genetic theory of morphological evolution. Cell 134 25

76. CarrollSB

GrenierJK

WeatherbeeSD

2001 From DNA to Diversity: Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design Malden Blackwell Scientific 214

77. SternDL

OrgogozoV

2008 The loci of evolution: how predictable is genetic evolution? Evolution 62 2155 2177

78. BrownKS

SheppardPM

TurnerJRG

1974 Quaternary refugia in tropical America: evidence from face formation in Heliconius butterflies. Proceedings of the Royal Society London B: Biological Sciences 187 369 387

79. BrowerAVZ

1994 Rapid morphological radiation and convergence among races of the butterfly Heliconius erato inferred from patterns of mitochondrial DNA evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 91 6491 6495

80. HoekstraHE

HirschmannRJ

BundeyRA

InselPA

CrosslandJP

2006 A aingle amino acid mutation contributes to adaptive beach mouse color pattern. Science 313 101 104

81. SucenaE

DelonI

JonesI

PayreF

SternDL

2003 Regulatory evolution of shavenbaby/ovo underlies multiple cases of morphological parallelism. Nature 424 935

82. WrayGA

2007 The evolutionary significance of cis-regulatory mutations. Nature Reviews Genetics 8 206 216

83. NielsenR

2005 Molecular signatures of natural selection. Annual Review of Genetics 39 197 218

84. NielsenR

WilliamsonS

KimY

HubiszMJ

ClarkAG

2005 Genomic scans for selective sweeps using SNP data. Genome Research 15 1566 1575

85. PrzeworskiM

CoopG

WallJD

2005 The signature of positive selection on standing genetic variation. Evolution 59 2312 2323

86. StajichJE

HahnMW

2005 Disentangling the effects of demography andselection in human history. Moleular Biology and Evolution 22 63 73

87. McGregorAP

OrgogozoV

DelonI

ZanetJ

SrinivasanDG

2007 Morphological evolution through multiple cis-regulatory mutations at a single gene. Nature 448 587 590

88. PapaR

MorrisonC

WaltersJR

CountermanBA

ChenR

2008 Highly conserved gene order and numerous novel repetitive elements in genomic regions linked to wing pattern variation in Heliconius butterflies. BMC Genomics 9 345

89. BrudnoM

MaldeS

PoliakovA

DoCB

CouronneO

2003 Glocal alignment: finding rearrangements during alignment. Bioinformatics 19 Suppl 1 i54 62

90. RozenS

SkaletskyHJ

2000 Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers.

KrawetzNJ

Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols Totowa Humana Pres 365 386

91. PringleB

BaxterSW

WebsterCL

PapanicolaouA

LeeSF

2007 Synteny and chromosome evolution in the Lepidoptera: Evidence from mapping in Heliconius melpomene. Genetics 177 417 426

92. HeyJ

WakeleyJ

1997 A coalescent estimator of the population recombination rate. Genetics 145 833 846

93. TajimaF

1989 Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123 585 595

94. MachadoCA

KlimanRM

MarkertJA

HeyJ

2002 Inferring the history of speciation from multilocus DNA sequence data: the case of Drosophila pseudoobscura and close relatives. Mol Biol Evol 19 472 488

95. BeaumontMA

NicholsRA

1996 Evaluating loci for use in the genetic analysis of population structure. Proceedings of the Royal Socety of London B 1619 1626

96. WeirBS

1996 Genetic data analysis II: methods for discrete population genetic data Sunderland Sinauer Associates

97. AbecasisGR

CooksonWOC

2000 GOLD–graphical overview of linkage disequilibrium. Bioinformatics 16 182 183

98. ReedRD

McMillanWO

NagyLM

2008 Gene expression underlying adaptive variation in Heliconius wing patterns: non-modular regulation of overlapping cinnabar and vermilion prepatterns. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 275 37 45

99. RafteryAEPI

VolinskyCT

n.d. BMA: An R package for Bayesian Model Averaging. R News 2 9

100. ToblerA

KapanD

FlanaganN

JohnsonJS

HeckelD

2005 First generation linkage map of H. erato. Heredity 94 408 417

101. FergusonL

LeeSF

ChamberlainN

NadeauN

JoronM

in press Characterization of a hotspot for mimicry: Assembly of a butterfly wing transcriptome to genomic sequence at the HmYb/Sb locus. Molecular Ecology

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Nuclear Pore Proteins Nup153 and Megator Define Transcriptionally Active Regions in the GenomeČlánek Deletion of the Huntingtin Polyglutamine Stretch Enhances Neuronal Autophagy and Longevity in MiceČlánek Analysis of the Genome and Transcriptome Uncovers Unique Strategies to Cause Legionnaires' DiseaseČlánek Population Genomics of Parallel Adaptation in Threespine Stickleback using Sequenced RAD TagsČlánek Wing Patterns in the Mist

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2010 Číslo 2- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Nuclear Pore Proteins Nup153 and Megator Define Transcriptionally Active Regions in the Genome

- The Scale of Population Structure in

- Allelic Exchange of Pheromones and Their Receptors Reprograms Sexual Identity in

- Genetic and Functional Dissection of and in Age-Related Macular Degeneration

- A Single Nucleotide Polymorphism within the Acetyl-Coenzyme A Carboxylase Beta Gene Is Associated with Proteinuria in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes

- The Genetic Interpretation of Area under the ROC Curve in Genomic Profiling