-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Role of Transposon-Derived Small RNAs in the Interplay between Genomes and Parasitic DNA in Rice

RNA silencing is a defense system against “genomic parasites” such as transposable elements (TE), which are potentially harmful to host genomes. In plants, transcripts from TEs induce production of double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) and are processed into small RNAs (small interfering RNAs, siRNAs) that suppress TEs by RNA–directed DNA methylation. Thus, the majority of TEs are epigenetically silenced. On the other hand, most of the eukaryotic genome is composed of TEs and their remnants, suggesting that TEs have evolved countermeasures against host-mediated silencing. Under some circumstances, TEs can become active and increase in copy number. Knowledge is accumulating on the mechanisms of TE silencing by the host; however, the mechanisms by which TEs counteract silencing are poorly understood. Here, we show that a class of TEs in rice produces a microRNA (miRNA) to suppress host silencing. Members of the microRNA820 (miR820) gene family are located within CACTA DNA transposons in rice and target a de novo DNA methyltransferase gene, OsDRM2, one of the components of epigenetic silencing. We confirmed that miR820 negatively regulates the expression of OsDRM2. In addition, we found that expression levels of various TEs are increased quite sensitively in response to decreased OsDRM2 expression and DNA methylation at TE loci. Furthermore, we found that the nucleotide sequence of miR820 and its recognition site within the target gene in some Oryza species have co-evolved to maintain their base-pairing ability. The co-evolution of these sequences provides evidence for the functionality of this regulation. Our results demonstrate how parasitic elements in the genome escape the host's defense machinery. Furthermore, our analysis of the regulation of OsDRM2 by miR820 sheds light on the action of transposon-derived small RNAs, not only as a defense mechanism for host genomes but also as a regulator of interactions between hosts and their parasitic elements.

Published in the journal: Role of Transposon-Derived Small RNAs in the Interplay between Genomes and Parasitic DNA in Rice. PLoS Genet 8(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002953

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002953Summary

RNA silencing is a defense system against “genomic parasites” such as transposable elements (TE), which are potentially harmful to host genomes. In plants, transcripts from TEs induce production of double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) and are processed into small RNAs (small interfering RNAs, siRNAs) that suppress TEs by RNA–directed DNA methylation. Thus, the majority of TEs are epigenetically silenced. On the other hand, most of the eukaryotic genome is composed of TEs and their remnants, suggesting that TEs have evolved countermeasures against host-mediated silencing. Under some circumstances, TEs can become active and increase in copy number. Knowledge is accumulating on the mechanisms of TE silencing by the host; however, the mechanisms by which TEs counteract silencing are poorly understood. Here, we show that a class of TEs in rice produces a microRNA (miRNA) to suppress host silencing. Members of the microRNA820 (miR820) gene family are located within CACTA DNA transposons in rice and target a de novo DNA methyltransferase gene, OsDRM2, one of the components of epigenetic silencing. We confirmed that miR820 negatively regulates the expression of OsDRM2. In addition, we found that expression levels of various TEs are increased quite sensitively in response to decreased OsDRM2 expression and DNA methylation at TE loci. Furthermore, we found that the nucleotide sequence of miR820 and its recognition site within the target gene in some Oryza species have co-evolved to maintain their base-pairing ability. The co-evolution of these sequences provides evidence for the functionality of this regulation. Our results demonstrate how parasitic elements in the genome escape the host's defense machinery. Furthermore, our analysis of the regulation of OsDRM2 by miR820 sheds light on the action of transposon-derived small RNAs, not only as a defense mechanism for host genomes but also as a regulator of interactions between hosts and their parasitic elements.

Introduction

RNA silencing is a mechanism mediated by small RNAs that regulates gene expression in eukaryotes at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. RNA silencing has a wide range of essential functions in cellular processes necessary for development of animals and plants, and it also has a role in defense against “genomic parasites” such as transposable elements (TEs) and viruses [1]–[3]. Silencing of TEs is triggered by small RNAs derived from the TE loci themselves. These small RNAs are usually 24 nt long in plants and are called small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). siRNAs are produced from TE transcripts by an enzyme called Dicer. Dicer acts on double-stranded RNA generated either by the action of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases or by transcription from both DNA strands. The TE-derived siRNAs are loaded onto Argonaute proteins, which degrade TE transcripts or repress translation by means of base-pairing between the transcripts and siRNAs [4]. In plants, TE-derived siRNAs also induce RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM), resulting in epigenetic inactivation of the TEs [5]–[7].

Although the majority of TEs are epigenetically silenced, most of the eukaryotic genome is composed of TEs and their remnants [8], [9]. This suggests that TEs have evolved countermeasures against host silencing [6], but the mechanisms by which TEs counteract silencing are poorly understood. In this paper, we demonstrate that a small RNA derived from certain TE loci suppresses the host silencing machinery. Generally, siRNAs produced from TEs trigger silencing of those same TEs; however, in this case, TEs escape host silencing by producing a class of miRNAs that acts on the host silencing machinery. Our analysis provides evidence for a novel mechanism by which transposons reduce host silencing, and it provides a glimpse of “front line” of host genome–parasitic DNA interactions through the action of small RNAs produced from the transposon.

Results/Discussion

Transposon-derived miR820 targets de novo DNA methyltransferase gene OsDRM2

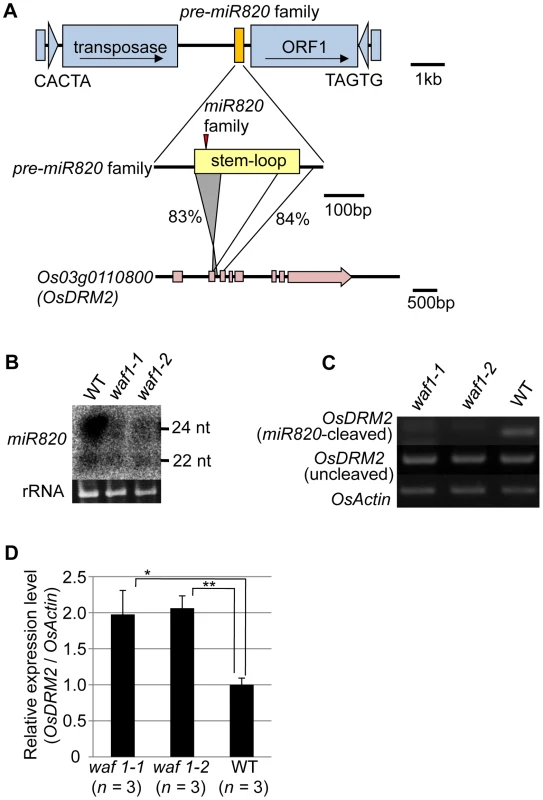

miRNAs are produced from stem structures formed within noncoding transcripts [10] and negatively regulate the expression of a range of plant genes, mainly by mRNA cleavage [11]. miR820 is a small-RNA species with sizes of 22 and 24 nt [12], [13]. miR820 is produced from transcripts originating from a region inside a class of CACTA DNA transposons in rice (Figure 1A). There are five copies of the CACTA transposon containing the miR820 precursor (pre-miR820) in the rice (Oryza sativa L.) Nipponbare genome [14] (Figure S1A, S1B). Three of the pre-miR820s (miR820a, -b, and –c) encode the identical miRNA sequence [15], whereas miR820d and miR820e differ from the other three by one and two nucleotides, respectively (Figure S1C). The nucleotide sequences of the fold-back region of all five pre-miR820 sequences show high sequence similarity to parts of Os03g0110800 and the homologous region extends into the second exon and third intron of Os03g0110800 (Figure 1A; Figures S2, S3). Thus, pre-miR820 possibly originated from Os03g0110800, and the number of pre-miR820 copies increases as the CACTA TEs propagate.

Fig. 1. miR820 family members are located within CACTA transposons and target the DNA methyltransferase gene OsDRM2.

(A) The location of miR820 within the CACTA DNA transposon is shown in the first row. The second and third rows indicate the similarity between the sequences of the miR820 precursor (pre-miR820) and Os03g0110800 (OsDRM2). The numbers beside the lines indicate the nucleotide identities between the regions. The red triangle indicates the location of miR820 within the stem-loop region. (B) Northern blot analysis of miR820 expression in the wild-type (WT) and in waf1 mutants. (C) Detection of miR820-cleaved OsDRM2 mRNA by RNA ligation–mediated 5′ RACE (upper panel). The same cDNA templates were used for PCR to amplify OsDRM2 (middle panel) and OsActin (bottom panel) as controls for OsDRM2 expression and RNA integrity. (D) qRT-PCR analysis measuring the expression level of OsDRM2 in waf1-1, waf1-2, and WT. The expression level of the WT was set as 1. Values are means, with bars showing standard errors. Significance was assessed by a two-tailed Student’s t-test; (**) significant at the 1% level; (*) significant at the 5% level. The n value represents the number of mutant or wild-type individuals. Because of this homology, miR820 is predicted to target Os03g0110800 (OsDRM2), which encodes a de novo DNA methyltransferase orthologous to Arabidopsis DRM1/2 [15]–[19] (Figure S4A). It has been reported that the 24-nt species of miR820 acts as a guide for DNA methylation at its target site, possibly through RdDM [13]. Indeed, we also confirmed the function of the 24-nt miR820 species by detecting a high level of cytosine methylation specific to its presumed target site (Figure S4B). Because pre-miR820 loci simultaneously produce both 22-nt and 24-nt miRNA species (Figure 1B), we investigated whether the 22-nt miR820 species regulates OsDRM2 expression through mRNA degradation by mapping the 22-nt miR820 cleavage site of OsDRM2. We found a cleavage site at the predicted position for miRNA-based target gene cleavage (Figure S4C).

We further confirmed that this cleavage depends on the presence of miR820 by using the waf1 mutant in rice [20] (Figure 1B–1D). In waf1, accumulation of small RNAs is greatly decreased because of a mutation in HEN1, a gene encoding an RNA methyltransferase that is required for the stability of small RNAs [21]–[23]. In waf1, the expression levels of both the 22-nt and 24-nt species of miR820 decreased compared to the wild-type (Figure 1B). To confirm that OsDRM2 mRNA cleavage depends on the presence of miR820, we checked for the cleavage product in waf1 mutants and in the wild-type. In the waf1 mutants, there was no detectable cleavage of OsDRM2 mRNA by miR820 (Figure 1C). We also confirmed that the expression level of OsDRM2 increased in waf1 compared to the wild-type (Figure 1D). It is possible that this increase was not due solely to the loss of miR820 because in waf1, the levels of most other small RNAs are also reduced [20]. However, considering that OsDRM2 gave the highest hit score when miR820 was used in BLAST searches against the entire rice genome (IRGSP Pseudomolecules 1.0) other than miR820 itself, it is very likely that miR820 negatively regulates the expression of OsDRM2 at least in part.

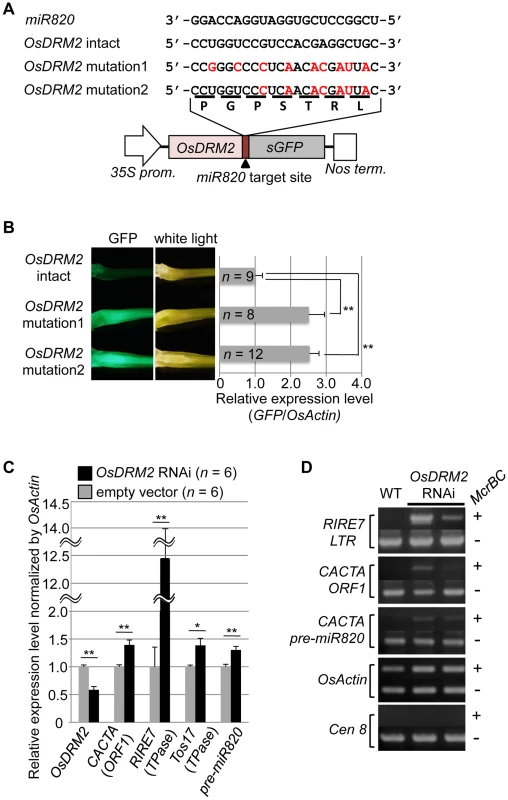

Negative regulation of OsDRM2 by miR820 activates TE expression

To test whether the expression level of OsDRM2 depends on recognition by miR820, we made transgenic rice plants that express a fusion of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene and OsDRM2 with or without synonymous mutations within the miR820 recognition site; we then observed the GFP fluorescence and measured GFP mRNA levels (Figure 2A, 2B). As expected, the expression level of the OsDRM2:GFP fusion gene with an intact miR820 recognition site was much lower than for those with synonymous mutations. In wild-type plants, both miR820 and OsDRM2 were expressed in all the tissues tested, although their expression levels differed between tissues (Figure S4D, S4G).

Fig. 2. OsDRM2 is negatively regulated by miR820.

(A) The general structure of the OsDRM2::GFP fusion constructs is shown at the bottom, and the sequences of miR820a/b/c and the target sites in the 35S:OsDRM2 intact:GFP, 35S:OsDRM2 mutation1:GFP, and 35S:OsDRM2 mutation2:GFP constructs are shown at the top. The changed nucleotides in the mutant genes are shown in red letters. (B) The panels on the left show GFP fluorescence and white-light observations of longitudinal sections of shoots of transgenic plants transformed with the constructs in (A). The graph at the right shows relative expression levels of GFP mRNA in the corresponding transgenic lines as measured by quantitative RT-PCR. The expression level of OsDRM2-intact lines was set as 1. (C) Relative expression levels of OsDRM2 and TEs in OsDRM2 RNAi transgenic callus (black bars) measured by qRT-PCR. The expression level of empty-vector lines was set as 1. (D) McrBC-PCR analysis of genomic DNA from callus of WT and two independent transgenic lines of OsDRM2 RNAi. Two of the six OsDRM2 RNAi transgenic lines analyzed in (C) were used. In (B) and (C), values are means, with bars showing standard errors. Significance was assessed by a two-tailed Student's t-test; (**) significant at the 1% level; (*) significant at the 5% level. The n value represents the number of independent transformants. Next, we tested whether the expression patterns of OsDRM2 and miR820 overlapped. Northern analysis using total RNA extracted from vegetative shoots from two wild-type rice cultivars demonstrated that both genes were expressed within this tissue (Figure S4E). In situ hybridization experiments revealed that OsDRM2 is ubiquitously expressed in vegetative shoots (Figure S4F). This suggests that the expression patterns of miR820 and OsDRM2 overlap at the cellular level, supporting the idea that miR820 regulates OsDRM2. On the other hand, we did not observe a clear inverse relationship between the levels of miR820 and OsDRM2 expression. This might be because the expression levels of miR820 and OsDRM2 differed between tissues, and because miR820 might reduce the amount of OsDRM2 expression but not abolish it completely. Indeed, we found that overexpression of pre-miR820 under the control of a strong constitutive promoter mildly reduced but did not eliminate the expression of OsDRM2 (Figure S5A–S5D).

Because de novo DNA methyltransferase is a component of the host's silencing machinery [16]–[17], we tested whether reduced OsDRM2 expression would affect the transcription of TEs by using transgenic rice plants in which OsDRM2 expression was reduced by RNAi. We found that the expression levels of several TEs were increased in DRM2 RNAi transgenic lines; furthermore, the expression levels of TEs such as RIRE7 and CACTA carrying pre-miR820 were inversely related to the degree of DRM2 suppression (Figure 2C; Figure S6). Next, we observed the DNA methylation status at several TE loci by McrBC-PCR analysis (Figure 2D). In OsDRM2 RNAi lines, DNA methylation within CACTA (including the pre-miR820 region) and RIRE7 is clearly reduced compared to the wild-type. Furthermore, we also observed elevated expression of RIRE7 in the same pre-miR820 overexpression experiment in which OsDRM2 expression was found to be mildly reduced (Figure S5E). These experimental data are consistent with the idea that OsDRM2 is involved in TE silencing through DNA methylation.

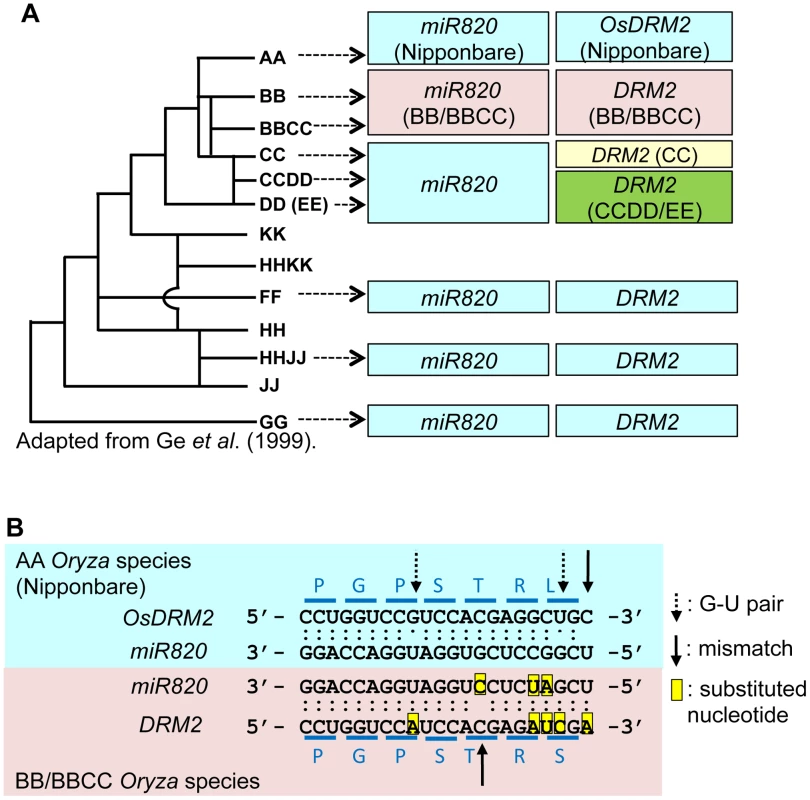

The sequences of miR820 and its target site in OsDRM2 have co-evolved in BB/BBCC Oryza species

We did not find miR820 or its precursor sequence in the Arabidopsis or maize genome, suggesting that miR820 is not widely conserved in plants. We then tested whether regulation by miR820 is conserved among various Oryza species. We successfully amplified and sequenced both miR820 and its recognition site in DRM2 from the genomic DNAs of various accessions of Oryza [24] (Figure S7A, S7B; Table S1), strongly suggesting the conservation of this regulation mechanism among Oryza species. We recovered sequences identical to miR820a/b/c from all the Oryza genomes tested except for the BB and BBCC genomes (Figure S7A; Table S1). In species with BB or BBCC genomes, miR820-related sequences had three nucleotide substitutions compared with miR820a/b/c. Considering the phylogenetic relationships among Oryza species [24], the miR820 sequence recovered from BB/BBCC Oryza species has diverged from miR820a/b/c (Figure 3A).

Fig. 3. Regulation of DRM2 by miR820 is conserved among Oryza species.

(A) The phylogenetic tree shows the evolutionary relationships between Oryza species (left). Boxes indicate the types of miR820 sequences and DRM2 target site sequences identified in each genome (right). Within each column, boxes of the same color indicate identical sequences. The genome origins of the sequences in the boxes are indicated by arrows. (B) Sequence alignments of miR820 and its target site in DRM2 in the AA (Nipponbare; blue box) and BB/BBCC genomes (pink box). Dots between nucleotides indicate the type of nucleotide pair: a double dot indicates an A-U or G-C pair, a single dot indicates a G-U pair, and no dot indicates a mismatch. The positions of G-U pairs and mismatches are shown with broken and solid arrows, respectively. The eight nucleotide substitutions found between AA and BB/BBCC Oryza species are highlighted in yellow. Blue lines above and below the sequence of DRM2 indicate the codons. Letters above and below the lines indicate the amino acids encoded by DRM2 in AA and BB/BBCC Oryza species, respectively. Phylogenetic tree in (A) adapted from Ge et al. (1999) [24]. There are also several nucleotide substitutions in the miR820 recognition site in DRM2 in some Oryza genomes (Figure S7B). Remarkably, in the BB and BBCC genomes, there are five nucleotide substitutions in DRM2. Thus, in the BB and BBCC genomes, there are eight nucleotide substitutions in miR820 and its recognition site in DRM2, compared with the corresponding miR820 and target sequences in Nipponbare. This number of substitutions could greatly affect the capability of miR820 to regulate DRM2 in species with those genomes; however, the degree of base-pairing between miR820 and its target site in DRM2 in the BB and BBCC genomes is conserved (Figure 3B; Table S1). This indicates that, in BB/BBCC Oryza species, the sequences of miR820 and its target site in DRM2 have co-evolved to maintain the ability to form a stable RNA–RNA duplex. The co-evolution of these sequences strongly suggests that the regulation of DRM2 by miR820 is functional and that those nucleotide changes have accumulated as a result of the interplay between the host genome and the parasitic elements in these species.

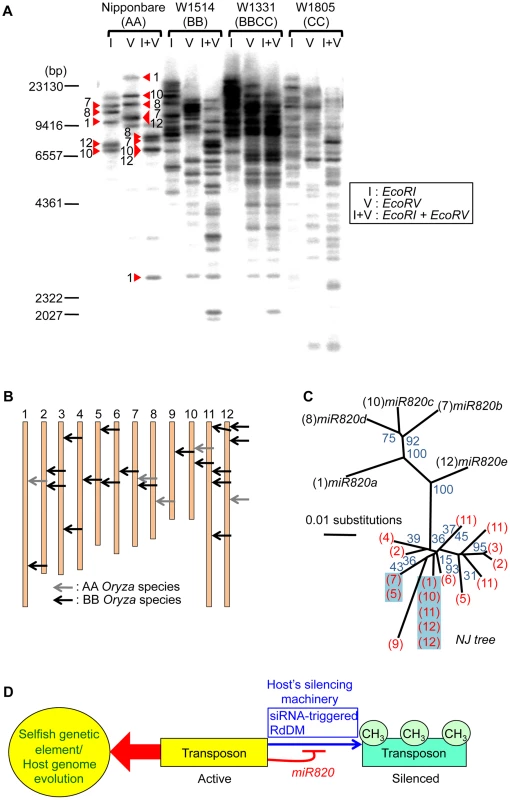

TEs carrying pre-miR820 have proliferated in BB-genome species

To see whether co-evolution of the nucleotide sequences of DRM2 and miR820 affected the behavior of TEs carrying pre-miR820 in the BB genome, we performed Southern blot analysis to detect the copy number of CACTA carrying pre-miR820 (Figure 4A). We found that the copy number of CACTA with pre-miR820 was much higher in the BB/BBCC Oryza species than in the AA species Nipponbare. We also successfully determined the genomic locations of CACTA with pre-miR820 in the BB genome (see Materials and Methods for details) and found that at least 18 copies of CACTA with pre-miR820 are dispersed throughout this genome (Figure 4B). We also sequenced the CACTA with pre-miR820 in BB-genome species and conducted phylogenetic analysis using pre-miR820 sequences from Nipponbare and BB-genome species. This analysis revealed a sudden increase in copy number of CACTA carrying pre-miR820, in which identical sequences around the pre-miR820 region were recovered from multiple loci (Figure 4C). Because the miR820 sequence in the BB species shown in Figure 3B was obtained by direct sequencing of PCR products, it should be representative of the miR820 sequence in BB species. In fact, the majority (11 out of 18 copies) of pre-miR820 found in the BB genome carries the same miR820 sequence as the one recovered by direct sequencing, which is also the sequence that would form the most stable hybrid with the DRM2 sequence found in the BB genome. These results suggest that the CACTA transposon with this miR820 sequence was predominantly proliferated or maintained, and became the predominant miR820 in BB species.

Fig. 4. Increased copy number of CACTA carrying pre-miR820 in the BB/BBCC genome.

(A) Detection of CACTA TEs carrying pre-miR820 by Southern blot analysis. Genomic DNA from AA, BB, BBCC, and CC Oryza species were digested with the enzymes indicated and probed with pre-miR820. Red triangles indicate the bands corresponding to the five copies of pre-miR820 in Nipponbare. The number next to each triangle indicates the chromosome location of that copy. (B) Mapping of CACTA carrying pre-miR820 in the rice genome. The genomic locations of CACTA carrying pre-miR820 in AA and BB Oryza species are shown by gray arrows and black arrows, respectively. (C) Phylogenetic analysis of miR820-CACTA sequences. Bootstrap values (1000 replicates) are given for branch nodes. Black and red numbers in parentheses indicate the chromosome locations of pre-miR820 sequences in the AA and BB genomes, respectively. Multiple copies on one branch, indicating that the identical sequence was found at multiple loci, are highlighted in blue. (D) A model for the regulation of DRM2 by miR820. Active transposons behave as “selfish” genetic elements. This characteristic is counteracted by the host's silencing machinery (blue arrow), which acts to methylate and silence transposon loci. This action can be blocked by miR820 (thin red line), which suppresses the host's silencing machinery and can drive host genome evolution (thick red arrow). We hypothesize the following scenario as a mechanism connecting the co-evolution of miR820 and DRM2 and the rapid increase in the copy number of CACTA carrying pre-miR820. When OsDRM2 expression decreases, possibly because of nucleotide substitutions within miR820 that enable it to form more stable hybrids with OsDRM2 or for other reasons, more miR820 can be produced, possibly because host-mediated silencing is suppressed efficiently. Indeed, RNAi-mediated suppression of OsDRM2 increased pre-miR820 expression (Figure S6C). This is expected to drive the selection of nucleotide substitutions at miR820 or at its target site because drastic reduction of OsDRM2 levels could be lethal. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that we recovered OsDRM2 RNAi transgenic plants with about half the normal expression level of OsDRM2 (Figure 2C). Thus, there should be selection pressure for mutations within the miRNA target site of OsDRM2. In turn, TE would favor changes in the miR820 sequence that correspond to the changes in the target site. This evolutionary “arms race”, in which hosts and parasitic DNA co-evolve, allows nucleotide substitutions to accumulate within both the miRNA and its target sequence, which maintains the ability to form stable hybrids between them. This might account for the fact that, in BB species, the most predominant CACTAs with pre-miR820 were those that could form the most stable hybrid with the target sequence.

A model for the regulation of DRM2 by miR820 sequences is shown in Figure 4D. In general, TE-derived small RNAs act as a trigger for silencing [5]–[7]. However, in this case, transposons that incorporate miRNA genes that target the host's silencing machinery are able to counteract the host's defense system. Similar examples of “arms races” between hosts and parasites are well documented in studies of plant RNA viruses and their hosts [25], in which RNA viruses that encode silencing-suppressor proteins are able to escape silencing by the host. Our model for the regulation of DRM2 by miR820 predicts that this regulation might affect not only CACTA carrying pre-miR820 but also other TEs. Indeed, in DRM2 RNAi lines, we observed upregulation of expression from TEs other than CACTA (Figure 2C). However, considering that BB-containing species have relatively small genomes compared with other Oryza species [26], the downregulation of DRM2 by miR820 would not be expected to affect a large number of TEs in BB-containing species. Rather the effect might be relatively specific to particular TEs or their lineage, as has been observed for the Arabidopsis ddm1 mutation [27].

So far, miR820 has been found only in rice, suggesting a recent origin. The primary and secondary structures of pre-miR820 also support this idea, because pre-miR820 still shows high homology within its stem parts to the intron sequence of OsDRM2. In general, non-conserved miRNA genes evolve very fast and they often appear and disappear from the genome. Considering that miR820 is encoded by parasitic DNA and its primary function seems to be as an anti-host agent, it is possible that miR820 might be lost in the future, as is often the case for non-conserved miRNA genes. However, it is intriguing to speculate that miR820 might function not only as an anti-host mechanism for parasites but also in a way that is beneficial for the host. The co-evolution of miR820 and its recognition site in BB/BBCC species supports this idea. It is possible that, in order to adapt against genomic stresses such as climate or environmental changes, the host maintained or created genome flexibility by keeping or allowing DRM2 under the regulation of miR820 in BB species in the past. Thus, our analysis of the regulation of DRM2 by miR820 sheds light on the action of two types of transposon-derived small RNAs, siRNA and miRNA, in the battles and possibly even the cooperation between plant genomes and their parasites.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

Wild-type Nipponbare and waf1 mutant rice plants were grown in soil or in tissue culture boxes at 29°C under continuous light. DNA, plants, and seeds of Oryza species were kindly provided by the National Institute of Genetics (Mishima, Japan).

Plasmid construction and production of transgenic plants

OsDRM2 cDNA was kindly provided by Dr. S. Iida, Shizuoka Prefectural University (Shizuoka, Japan). The p35S:OsDRM2 intact:GFP, p35S:OsDRM2 mutation1:GFP, and p35S:OsDRM2 mutation2:GFP vectors were constructed by introducing mutations using the GeneTailor Site-Directed Mutagenesis System (Invitrogen). Next, the part of each OsDRM2 cDNA that included the miR820 target site was amplified and cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). The resultant vectors containing the cDNA fragments were introduced into the pGWB5 binary vector [28], which carries a GFP reporter gene driven by the 35S promoter, by using Gateway technology (Invitrogen). For pAct:pre-miR820:Nos construction, a 0.5-kb pre-miR820 fragment was amplified and inserted into the pCRII vector (Invitrogen). A pre-miR820 fragment was then excised with XbaI and SmaI, and cloned into the binary vector carrying the rice Actin gene promoter and Nos terminator. For pAct:OsDRM2 RNAi:Nos construction, a 0.9-kb OsDRM2 cDNA fragment with PstI and XbaI linkers was cloned into the PstI and XbaI sites of the pBS-SK vector containing a partial GUS fragment at its EcoRV site. Similarly, a cDNA fragment with HindIII and SmaI/ApaI linkers was inserted into the HindIII and ApaI sites of the vector. The resultant vector was cloned into the XbaI and SmaI sites of a binary vector carrying the rice Actin gene promoter and Nos terminator. These binary vectors were introduced into Agrobacterium strain EHA101 and used for transformation of rice by the standard method [29]. The primers used for vector construction are listed in Table S2.

RNA analysis

Total RNA was isolated from shoots of waf1 and various tissues of Nipponbare wild-type non-transgenic plants; shoots of p35S:OsDRM2 intact:GFP, p35S:OsDRM2 mutation1:GFP, and p35S:OsDRM2 mutation2:GFP T2 plants; and calli of pAct:pre-miR820 and pAct:OsDRM2 RNAi by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). For analysis of waf1 and wild-type plants and of pAct:pre-miR820:Nos and pAct:OsDRM2 RNAi:Nos callus, 10 µg of each RNA sample was loaded onto an agarose or acrylamide gel (for analysis of OsDRM2 and miR820a/b/c, respectively), separated by electrophoresis, and blotted onto nylon membranes. The membranes were probed with oligo DNA complementary to miR820a/b/c or OsDRM2 cDNA, depending on the experiment.

5′ RACE

Total RNA was purified with the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. 3 µg of purified total RNA was subjected to RNA Oligo ligation with the GeneRacer Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The oligo-ligated RNA was reverse-transcribed using Omniscript Reverse Transcriptase (QIAGEN) with random primers (N9). PCR and nested PCR were performed using Ex Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa). Primers used for 5′ RACE PCR are listed in Table S2. Amplified bands were gel-purified, cloned, and sequenced.

RT–PCR

Relative expression levels were quantified using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and the One Step SYBR PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit II (TaKaRa). The quantitative RT-PCR reactions contained 5 µl 2× One Step SYBR RT-PCR Buffer 4, 0.5 µl DMSO, 0.4 µl PrimeScript 1 step Enzyme Mix 2, 0.2 µl 50× ROX reference dye, 50 ng total RNA, and 400 nM of each primer, and were run in triplicate. The mixtures were first reverse-transcribed at 42°C for 5 min, then amplified via PCR using a two-step cycling program (95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 20 s) for 40 cycles. Quantitative RT-PCR specificity was checked for each run with a dissociation curve, at temperatures ranging from 95°C to 60°C. Data from quantitative RT-PCR were analyzed using the standard-curve method. The housekeeping genes OsActin and OsGAPDH were used to normalize the quantitative RT-PCR output. Primers used for quantitative RT-PCR are listed in Table S2.

McrBC–PCR

Genomic DNAs were isolated from wild-type nontransgenic and pAct:OsDRM2 RNAi:Nos calli. For McrBC-PCR analysis, 500 ng of genomic DNAs were digested with or without 40 units of McrBC restriction enzyme (New England Biolabs) for 12 hr. PCR was performed using Ex Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa). Primers used for PCR are listed in Table S2. OsActin and Centromere 8 are controls for regions with low and high DNA methylation, respectively.

Sequence analysis

Genomic DNA samples from various Oryza species were kindly provided by the National Institute of Genetics (Mishima, Japan). We amplified both miR820 and its target site in DRM2 by PCR using the primers listed in Table S2. The amplified DNA fragments were gel-purified and used as templates for direct sequencing. The miRNA target score was calculated for each miR820:DRM2 duplex based on the method described in [30]. To detect the copy number of CACTA TEs carrying miR820 by Southern blot analysis, genomic DNA samples were extracted from leaves of Nipponbare (AA), W1514 (BB), W1331 (BBCC), and W1805 (CC), treated with RNase A, and digested with restriction enzymes. These samples were loaded onto an agarose gel, separated by electrophoresis, blotted onto a nylon membrane, and probed with the pre-miR820 DNA fragment.

Mapping of CACTA carrying pre-miR820

Our strategy to map miR820-CACTA from BB-genome species was based on the synteny between AA and BB Oryza species [26]. Briefly, by screening the BAC library of a BB-genome species, we identified BAC clones carrying miR820-CACTA from BB. Then, using the BAC end sequences of these clones deposited to database, we identified the corresponding physical position of these clones in the Nipponbare genome. This strategy is advantageous over other methods, such as transposon display, to monitor the varieties of transposon, especially long transposons with specific internal sequences, because transposon display identifies only the ends of transposon sequences. The precise method used for this experiment was as follows: A BAC filter and library of Oryza punctata (genome BB) genomic DNA were purchased from the Arizona Genomics Institute (Tucson, AZ). By screening these libraries using a labeled pre-miR820 DNA fragment, we identified 48 BAC clones carrying miR820-CACTA. We confirmed that these clones carried miR820-CACTA by PCR amplification and sequencing of the region around pre-miR820 in CACTA. Using the BAC end sequence obtained from http://www.omap.org/, we located those BACs on a physical map of the Nipponbare rice genome. Multiple sequence alignment for the phylogenetic analysis was constructed using Clustal X, and an unrooted tree was made by the neighbor-joining method [31] using PAUP 4.0 software (Sinauer Associates).

In situ mRNA hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as previously described by Kouchi and Hata (1993) [32]. For the OsDRM2 probe, the full-length cDNA clone was used as a template for in vitro transcription. Hybridizations were conducted at 55°C overnight; slides were then washed four times at 50°C for 10 min each. An excess amount of sense transcript was used as negative control.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. PlasterkRHA (2002) RNA silencing: The genome's immune system. Science 296 : 1263–1265.

2. AlmediaR, AllshireRC (2005) RNA silencing and genome regulation. Trends Cell Biol 15 : 251–258.

3. AravinAA, HannonGJ, BrenneckeJ (2007) The Piwi-piRNA pathway provides an adaptive defense in the transposon arms race. Science 318 : 761–764.

4. SaitoK, SiomiMC (2010) Small RNA-mediated quiescence of transposable elements in animals. Dev Cell 19 : 687–697.

5. ZilbermanD, HenikoffS (2004) Silencing of transposons in plant genomes: kick them when they're down. Genome Biol 5 : 249.1–249.5.

6. LischD (2009) Epigenetic regulation of transposable elements in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60 : 43–66.

7. MatzkeM, KannoT, DaxingerL, HuettelB, MatzkeAJM (2009) RNA-mediated chromatin-based silencing in plants. Curr Opin Cell Biol 21 : 367–376.

8. FeschotteC, JiangN, WesslerSR (2002) Plant transposable elements: where genetics meets genomics. Nature Rev Genet 3 : 329–341.

9. KidwellMG (2002) Transposable elements and the evolution of genome size in eukaryotes. Genetica 115 : 49–63.

10. MeyersBC, AxtellMJ, BartelB, BartelDP, BaulcombeD, et al. (2008) Criteria for annotation of plant microRNAs. Plant Cell 20 : 3186–3190.

11. VoinnetO (2009) Origin, biogenesis, and activity of plant microRNAs. Cell 136 : 669–687.

12. ChellappanP, XiaJ, ZhouX, GaoS, ZhangX, et al. (2010) siRNAs from miRNA sites mediate DNA methylation of target genes. Nucleic Acids Res 38 : 6883–6894.

13. WuL, ZhouH, ZhangQ, ZhangJ, NiF, et al. (2010) DNA methylation mediated by a microRNA pathway. Mol Cell 38 : 465–475.

14. Rice Annotation Project (2008) The rice annotation project database (RAP-DB): 2008 update. Nucleic Acids Res 36: D1028–D1033.

15. LuoYC, ZhouH, LiY, ChenJY, YangJH, et al. (2006) Rice embryogenic calli express a unique set of microRNAs, suggesting regulatory roles of microRNAs in plant post-embryogenic development. FEBS Lett 580 : 5111–5116.

16. CaoX, SpringerNM, MuszynskiMG, PhillipsRL, KaepplerS, et al. (2000) Conserved plant genes with similarity to mammalian de novo DNA methyltransferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 : 4979–4984.

17. CaoX, JacobsenSE (2002) Role of the Arabidopsis DRM methyltransferases in de novo DNA methylation and gene silencing. Curr Biol 12 : 1138–1144.

18. SharmaR, SinghRKM, MalikG, DeveshwarP, TyagiAK, et al. (2009) Rice cytosine DNA methyltransferases – gene expression profiling during reproductive development and abiotic stress. FEBS J 276 : 6301–6311.

19. HendersonIR, DelerisA, WongW, ZhongX, ChinHG, et al. (2010) The de novo cytosine methyltransferase DRM2 requires intact UBA domains and a catalytically mutated paralog DRM3 during RNA-directed DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet 6: e1001182 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001182.

20. AbeM, YoshikawaT, NosakaM, SakakibaraH, SatoY, et al. (2010) WAVY LEAF 1, an ortholog of Arabidopsis HEN1, regulates shoot development through maintaining microRNA and trans-acting siRNA accumulation in rice. Plant Physiol 154 : 1335–1346.

21. LiJ, YangZ, YuB, LiuJ, ChenX (2005) Methylation protects miRNAs and siRNAs from a 3′-end uridylation activity in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 15 : 1501–1507.

22. YuB, YangZ, LiJ, MinakhinaS, YangM, et al. (2005) Methylation as a crucial step in plant microRNA biogenesis. Science 307 : 932–935.

23. YangZ, EbrightYW, YuB, ChenX (2006) HEN1 recognizes 21–24 nt small RNA duplexes and deposits a methyl group onto the 2′ OH of the 3′ terminal nucleotide. Nucleic Acids Res 34 : 667–675.

24. GeS, SangT, LuBR, HongDY (1999) Phylogeny of rice genomes with emphasis on origins of allotetraploid species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 : 14400–14405.

25. WaterhousePM, WangMB, LoughT (2001) Gene silencing as an adaptive defence against viruses. Nature 411 : 834–842.

26. KimHR, MiguelPS, NelsonW, ColluraK, WissotskiM, et al. (2007) Comparative physical mapping between Oryza sativa (AA genome type) and O. punctata (BB genome type). Genetics 176 : 379–390.

27. TsukaharaS, KobayashiA, KawabeA, MathieuO, MiuraA, et al. (2009) Bursts of retrotransposition reproduced in Arabidopsis. Nature 461 : 423–426.

28. NakagawaT, SuzukiT, MurataS, NakamuraS, HinoT, et al. (2007) Improved gateway binary vectors: High-performance vectors for creation of fusion constructs in transgenic analysis of plants. Biosci Biotech Biochem 71 : 2095–2100.

29. HieiY, OhtaS, KomariT, KumashiroT (1994) Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J 6 : 271–282.

30. AllenE, XieZ, GustafsonAM, CarringtonJC (2005) microRNA-directed phasing during trans-acting siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell 121 : 207–221.

31. SaitouN, NeiM (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4 : 406–425.

32. KouchiH, HataS (1993) Isolation and characterization of novel nodulin cDNAs representing genes expressed at early stages of soybean nodule development. Mol Gen Genet 238 : 106–119.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Genome-Wide Association Study for Serum Complement C3 and C4 Levels in Healthy Chinese SubjectsČlánek Tetraspanin Is Required for Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species by the Dual Oxidase System inČlánek An Essential Role of Variant Histone H3.3 for Ectomesenchyme Potential of the Cranial Neural CrestČlánek A Mimicking-of-DNA-Methylation-Patterns Pipeline for Overcoming the Restriction Barrier of BacteriaČlánek A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Five Loci Influencing Facial Morphology in Europeans

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2012 Číslo 9- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Heterozygous Mutations in DNA Repair Genes and Hereditary Breast Cancer: A Question of Power

- GWAS of Diabetic Nephropathy: Is the GENIE out of the Bottle?

- The Conflict within and the Escalating War between the Sex Chromosomes

- Proteome-Wide Analysis of Disease-Associated SNPs That Show Allele-Specific Transcription Factor Binding

- Exome Sequencing Identifies Rare Deleterious Mutations in DNA Repair Genes and as Potential Breast Cancer Susceptibility Alleles

- A Gene Family Derived from Transposable Elements during Early Angiosperm Evolution Has Reproductive Fitness Benefits in

- Genome-Wide Association Study for Serum Complement C3 and C4 Levels in Healthy Chinese Subjects

- Role of Transposon-Derived Small RNAs in the Interplay between Genomes and Parasitic DNA in Rice

- Co-Evolution of Mitochondrial tRNA Import and Codon Usage Determines Translational Efficiency in the Green Alga

- SIRT6/7 Homolog SIR-2.4 Promotes DAF-16 Relocalization and Function during Stress

- CNV Formation in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells Occurs in the Absence of Xrcc4-Dependent Nonhomologous End Joining

- Tetraspanin Is Required for Generation of Reactive Oxygen Species by the Dual Oxidase System in

- Citrullination of Histone H3 Interferes with HP1-Mediated Transcriptional Repression

- Variation in Genes Related to Cochlear Biology Is Strongly Associated with Adult-Onset Deafness in Border Collies

- The Long Non-Coding RNA Affects Chromatin Conformation and Expression of , but Does Not Regulate Its Imprinting in the Developing Heart

- Rif2 Promotes a Telomere Fold-Back Structure through Rpd3L Recruitment in Budding Yeast

- Is a Metastasis Susceptibility Gene That Suppresses Metastasis by Modifying Tumor Interaction with the Cell-Mediated Immunity

- The p38/MK2-Driven Exchange between Tristetraprolin and HuR Regulates AU–Rich Element–Dependent Translation

- Rare Copy Number Variants Contribute to Congenital Left-Sided Heart Disease

- A Genetic Basis for a Postmeiotic X Versus Y Chromosome Intragenomic Conflict in the Mouse

- An Essential Role of Variant Histone H3.3 for Ectomesenchyme Potential of the Cranial Neural Crest

- Characterization of Inducible Models of Tay-Sachs and Related Disease

- Hominoid-Specific Protein-Coding Genes Originating from Long Non-Coding RNAs

- Transcriptional Repression of Hox Genes by HP1/HPL and H1/HIS-24

- Integrative Genomic Analysis Identifies Isoleucine and CodY as Regulators of Virulence

- Convergence of the Transcriptional Responses to Heat Shock and Singlet Oxygen Stresses

- Genomics of Adaptation during Experimental Evolution of the Opportunistic Pathogen

- Enrichment of HP1a on Drosophila Chromosome 4 Genes Creates an Alternate Chromatin Structure Critical for Regulation in this Heterochromatic Domain

- Vsx2 Controls Eye Organogenesis and Retinal Progenitor Identity Via Homeodomain and Non-Homeodomain Residues Required for High Affinity DNA Binding

- The Long Path from QTL to Gene

- TCF7L2 Modulates Glucose Homeostasis by Regulating CREB- and FoxO1-Dependent Transcriptional Pathway in the Liver

- The Non-Flagellar Type III Secretion System Evolved from the Bacterial Flagellum and Diversified into Host-Cell Adapted Systems

- Complex Chromosomal Rearrangements Mediated by Break-Induced Replication Involve Structure-Selective Endonucleases

- Factors That Promote H3 Chromatin Integrity during Transcription Prevent Promiscuous Deposition of CENP-A in Fission Yeast

- A Mimicking-of-DNA-Methylation-Patterns Pipeline for Overcoming the Restriction Barrier of Bacteria

- Determinants of Human Adipose Tissue Gene Expression: Impact of Diet, Sex, Metabolic Status, and Genetic Regulation

- Genome-Wide Association Studies Identify Heavy Metal ATPase3 as the Primary Determinant of Natural Variation in Leaf Cadmium in

- Tethering of the Conserved piggyBac Transposase Fusion Protein CSB-PGBD3 to Chromosomal AP-1 Proteins Regulates Expression of Nearby Genes in Humans

- A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Five Loci Influencing Facial Morphology in Europeans

- Normal DNA Methylation Dynamics in DICER1-Deficient Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- H4K20me1 Contributes to Downregulation of X-Linked Genes for Dosage Compensation

- The NDR Kinase Scaffold HYM1/MO25 Is Essential for MAK2 MAP Kinase Signaling in

- Coevolution within and between Regulatory Loci Can Preserve Promoter Function Despite Evolutionary Rate Acceleration

- New Susceptibility Loci Associated with Kidney Disease in Type 1 Diabetes

- SWI/SNF-Like Chromatin Remodeling Factor Fun30 Supports Point Centromere Function in

- A Response Regulator Interfaces between the Frz Chemosensory System and the MglA/MglB GTPase/GAP Module to Regulate Polarity in

- Functional Variants in and Involved in Activation of the NF-κB Pathway Are Associated with Rheumatoid Arthritis in Japanese

- Two Distinct Repressive Mechanisms for Histone 3 Lysine 4 Methylation through Promoting 3′-End Antisense Transcription

- Genetic Modifiers of Chromatin Acetylation Antagonize the Reprogramming of Epi-Polymorphisms

- UTX and UTY Demonstrate Histone Demethylase-Independent Function in Mouse Embryonic Development

- A Comparison of Brain Gene Expression Levels in Domesticated and Wild Animals

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Enrichment of HP1a on Drosophila Chromosome 4 Genes Creates an Alternate Chromatin Structure Critical for Regulation in this Heterochromatic Domain

- Normal DNA Methylation Dynamics in DICER1-Deficient Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells

- The NDR Kinase Scaffold HYM1/MO25 Is Essential for MAK2 MAP Kinase Signaling in

- Functional Variants in and Involved in Activation of the NF-κB Pathway Are Associated with Rheumatoid Arthritis in Japanese

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy