-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Centromere-Like Regions in the Budding Yeast Genome

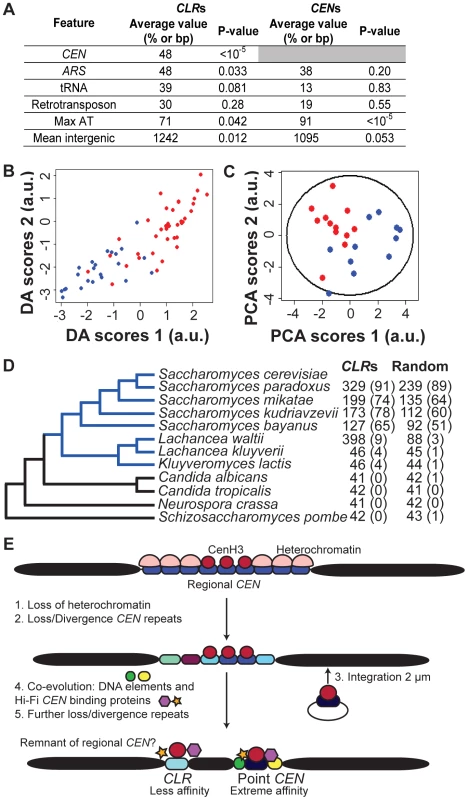

Accurate chromosome segregation requires centromeres (CENs), the DNA sequences where kinetochores form, to attach chromosomes to microtubules. In contrast to most eukaryotes, which have broad centromeres, Saccharomyces cerevisiae possesses sequence-defined point CENs. Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP–Seq) reveals colocalization of four kinetochore proteins at novel, discrete, non-centromeric regions, especially when levels of the centromeric histone H3 variant, Cse4 (a.k.a. CENP-A or CenH3), are elevated. These regions of overlapping protein binding enhance the segregation of plasmids and chromosomes and have thus been termed Centromere-Like Regions (CLRs). CLRs form in close proximity to S. cerevisiae CENs and share characteristics typical of both point and regional CENs. CLR sequences are conserved among related budding yeasts. Many genomic features characteristic of CLRs are also associated with these conserved homologous sequences from closely related budding yeasts. These studies provide general and important insights into the origin and evolution of centromeres.

Published in the journal: Centromere-Like Regions in the Budding Yeast Genome. PLoS Genet 9(1): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003209

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003209Summary

Accurate chromosome segregation requires centromeres (CENs), the DNA sequences where kinetochores form, to attach chromosomes to microtubules. In contrast to most eukaryotes, which have broad centromeres, Saccharomyces cerevisiae possesses sequence-defined point CENs. Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP–Seq) reveals colocalization of four kinetochore proteins at novel, discrete, non-centromeric regions, especially when levels of the centromeric histone H3 variant, Cse4 (a.k.a. CENP-A or CenH3), are elevated. These regions of overlapping protein binding enhance the segregation of plasmids and chromosomes and have thus been termed Centromere-Like Regions (CLRs). CLRs form in close proximity to S. cerevisiae CENs and share characteristics typical of both point and regional CENs. CLR sequences are conserved among related budding yeasts. Many genomic features characteristic of CLRs are also associated with these conserved homologous sequences from closely related budding yeasts. These studies provide general and important insights into the origin and evolution of centromeres.

Introduction

The kinetochore is a conserved proteinaceous structure that assembles on centromeric DNA and is responsible for connecting chromosomes to the spindle, thus ensuring accurate chromosome segregation. The length of centromeric DNA differs among eukaryotes, from less than one kilobase pair (kb) to several megabase pairs (Mb) [1]. This variation is most striking in fungi: whereas most fungi have large, regional centromeres spanning several kbs, the Saccharomyces lineage has small, punctate CENs encompassing only 125 base pairs (bp) [2]. A hallmark of centromeric chromatin is the presence of the histone H3 variant CENP-A, or CenH3 [1], known as Cse4 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [3]. Overproduction of human CENP-A promotes its incorporation onto non-centromeric loci and has been linked to colorectal cancer and aneuploidy [4]. In S. cerevisiae, Cse4 is commonly found outside centromeres using chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled to high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-Seq) [5]. Whereas overproduction of Cse4 does not appear to be severely deleterious or lead to a decrease in cell viability in yeast [6], it can become lethal in the absence of its specific E3 ubiquitin ligase Psh1 due to massive and stable Cse4 euchromatin incorporation [7], [8].

If Cse4 accumulation at non-centromeric sites is functional, i.e. imparts centromere-like activity, then additional kinetochore proteins should also be present. To investigate this possibility, we generated genome-wide binding profiles using ChIP-Seq to characterize four epitope-tagged kinetochore proteins, comparing a wild-type strain with normal levels of Cse4 (WT) to a strain overproducing Cse4 (Cse4 OP). Our ChIP-Seq data indicate recruitment of all tested kinetochore proteins to discrete sites outside CENs, termed Centromere-Like Regions (CLRs). We showed that cloned CLRs can help the segregation of a CEN-less episomal plasmid and that endogenous CLRs can promote accurate segregation of a chromosome bearing an inactivated centromere. We found that most CLRs are found in larger than average intergenic regions and lie in close proximity to S. cerevisiae centromeres. Other genomic features associated with CLRs include a weak association to autonomously-replicating sequences (ARS; yeast origins of DNA replication) and an increased level of “AT” nucleotides over a short stretch of DNA. We observed sequence conservation of CLRs with members of the Saccharomyces sensu stricto and other budding yeasts carrying point CENs, but not with other yeasts and fungi bearing larger, regional CENs. Our results have implications for the origin and evolution of centromeres since CLRs might constitute evolutionary remnants from regional CENs.

Results/Discussion

Identification of CLRs using ChIP–Seq

ChIP-Seq data were generated for four epitope-tagged kinetochore proteins: Cse4 (CenH3), the outer kinetochore protein Ndc80 (Hec1), and the inner kinetochore components Mif2 (CENP-C) and Ndc10 (Cbf2). We compared a wild-type strain with normal levels of Cse4 (WT) to a strain overproducing Cse4 from the Gal1–10 promoter (Cse4 OP), with at least a 3-fold increase in Cse4 protein levels in Cse4 OP as measured by Western blots (Figure S1; Cse4 with 3HA epitope as an internal tag). All proteins were tagged at their native locus and were the only copies present in the haploid cell. At least two biological replicates were examined per tagged strain, and these were compared to a matched control representing an immunoprecipitate from an untagged strain [9]. Regions of significant binding were identified with the PeakSeq algorithm using a stringent q-value threshold of 10−5 [10], [11] and further filtered to remove regions of poor enrichment.

Consistent with the presence of sequence-defined point centromeres in S. cerevisiae [2], Cse4, Mif2, Ndc10 and Ndc80 bind very strongly to CENs in WT and Cse4 OP strains (Figure 1A and Figure S2). Overproduction of Cse4 generates a broader ChIP-Seq signal for kinetochore proteins at some centromeres, which is particularly apparent in aggregated signal plots around CEN2, CEN5 and CEN10 (Figure 2A and Figure S2; P = 0.03; paired t-test) and is consistent with ChIP-qPCR data from S. cerevisiae [12]. A similar pattern has been observed in the pathogenic budding yeast Candida albicans, where Cse4 overproduction is associated with the presence of extra kinetochore proteins and microtubules at CENs [13].

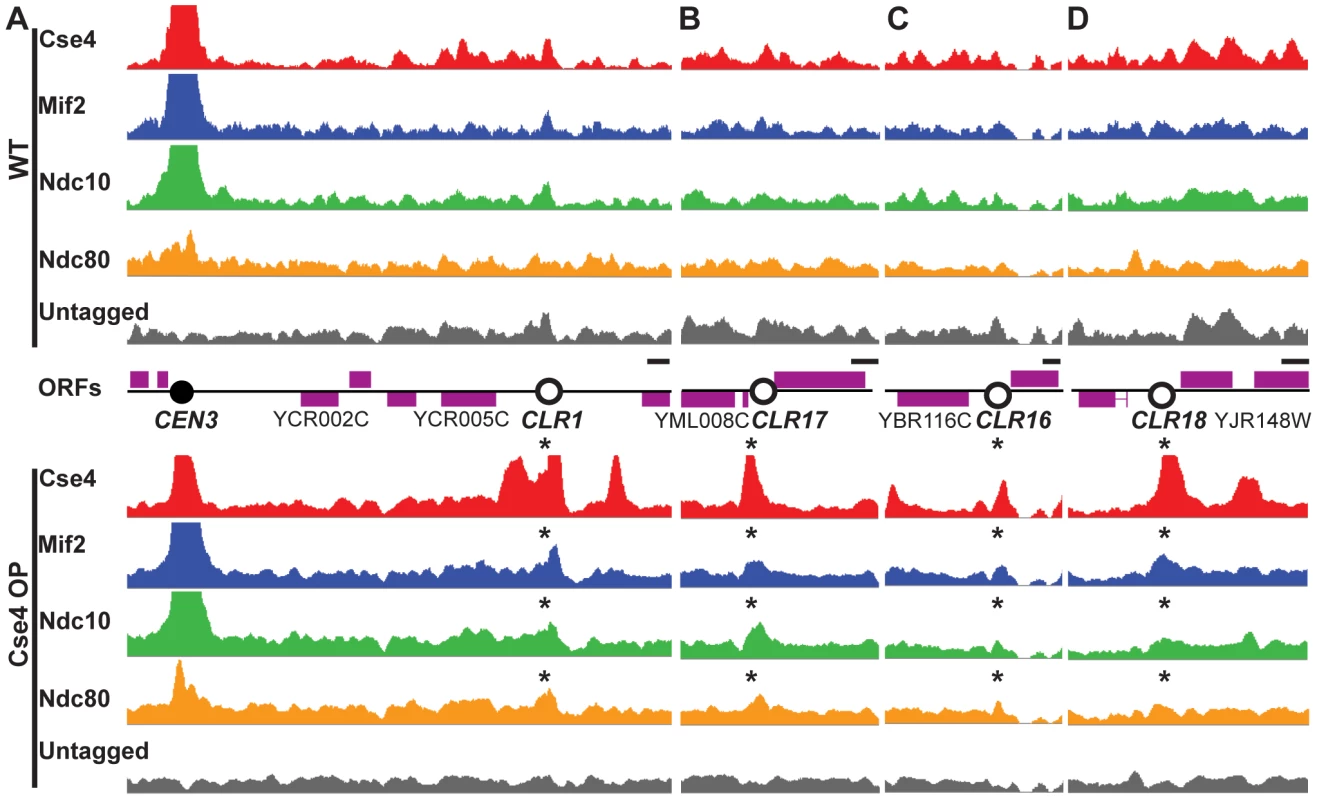

Fig. 1. Formation of Centromere-Like Regions revealed by ChIP–Seq.

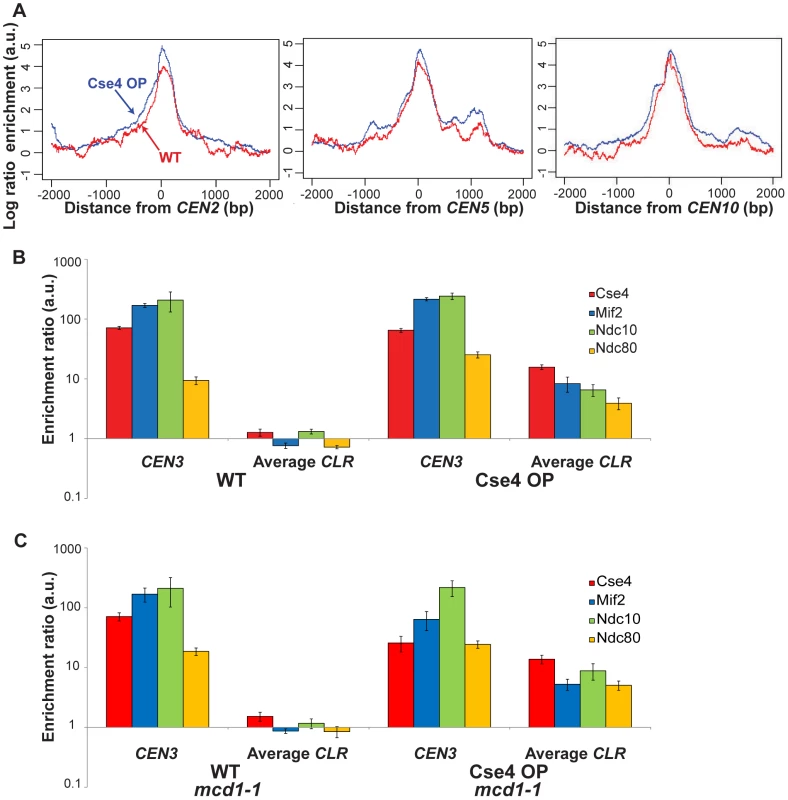

Cse4 (red), Mif2 (blue), Ndc10 (green) and Ndc80 (orange) bind to the same discrete regions outside centromeres in Cse4 OP (bottom panels), but not in WT (top). (A–B) Highest-confidence sites are CEN-proximal; examples include CLRs 9 kb away from CEN3 (A), and 15 kb from CEN13 (B). Asterisks above signal tracks denote location of CLRs. (C–D) A few sites are far from CENs; examples include CLRs 239 kb away from CEN2 (C) and 267 kb from CEN10 (D). Signal tracks are scaled relative to the number of uniquely-mapping reads. Control samples (immunoprecipitates from untagged strains) are shown in grey. Open reading frames (ORFs) are depicted by purple boxes. Horizontal scale bars represent 0.5 kb. Fig. 2. Quantitation of protein binding in Cse4 OP strains.

(A) Kinetochore proteins show a broader distribution at centromeres when Cse4 is overproduced. Shown is ChIP-Seq signal for kinetochore proteins in Cse4 OP (blue) compared to WT (red) at CEN2 (left), CEN5 (middle) and CEN10 (right). Aggregated signal plots depict the log ratio of read enrichment for four kinetochore components, centered at the CEN, on log 2 scales. (B) ChIP-qPCR confirms the presence of kinetochore proteins at CLRs in Cse4 OP, not in WT. Individual protein enrichments for 6 CLRs were averaged and compared to CEN3 binding levels. Normalized enrichment ratios (means in arbitrary units (a.u.)+/−SEM) were plotted on a log 10 scale. A normalized enrichment of 1 indicates no enrichment over a negative control region not enriched for kinetochore proteins. (C) ChIP-qPCR in a cohesin-deficient mcd1-1 background highlights CLR formation in Cse4 OP despite the abrogation of the pericentric intramolecular C loop. Individual protein enrichments for 6 CLRs were averaged and compared to CEN3 binding levels. Normalized enrichment ratios (means in arbitrary units (a.u.)+/−SEM) were plotted on a log 10 scale. In WT, only centromeric regions exhibit significant overlapping binding among all four tested kinetochore components (Figure 1, top). However, in Cse4 OP, several non-centromeric locations display overlapping binding, albeit to a lesser extent than native CENs (Figure 1 bottom). We termed these 23 non-centromeric loci Centromere-Like Regions, or CLRs (Table 1). There is a strong bias towards formation of CLRs in close proximity to centromeres; about half lie within 25 kb of a CEN (P<10−5; randomization test), especially among those displaying high levels of protein binding (Figure 1A–1B). Most chromosomes have at least one centromere-proximal CLR. A few CLRs are located far from the actual CEN (>100 kb distal), and, compared to CEN-proximal CLRs, these centromere-distal CLRs are generally associated with reduced, yet significant, occupancy of the outer kinetochore protein Ndc80 (Figure 1C–1D).

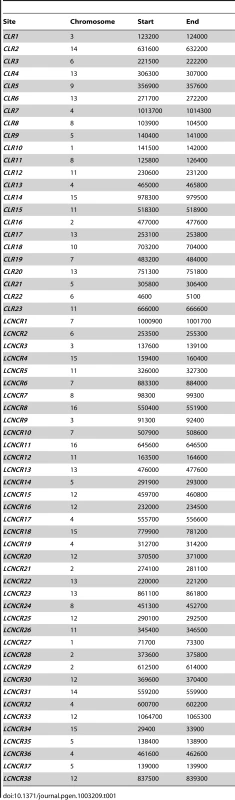

Tab. 1. Chromosomal coordinates of Centromere-Like Regions (<i>CLR</i>s) and of sites that did not pass statistical filters (low-confidence, negative control regions (<i>LCNCR</i>s)).

Protein binding was validated at six different CLRs and at CEN3 by ChIP-qPCR. In WT, no individual CLR showed significant binding (normalized enrichment ratio >2) for all four proteins (Figure 2B and Figure S3A). However, in Cse4 OP strains, binding of four kinetochore components was significant at each of six CLRs tested (Figure 2B and Figure S3B). Protein occupancy at CLRs is about an order of magnitude less than levels seen at CEN3 (Figure 2B), confirming that bona fide CENs remain the primary sites where kinetochore proteins reside in budding yeast with elevated Cse4 abundance.

Pericentric chromatin is arranged in an intramolecular C loop that extends >25 kb but <50 kb around CENs [14], generating the mitotic centromere spring that balances tension at the metaphase plate from the spindle microtubules [15], [16]. This loop arrangement requires cohesin, as loss of cohesion using the mcd1-1 allele at the restrictive temperature abrogates the pericentric loop [14]. In this C loop configuration, centromeres and sequences from proximal regions might be in close spatial proximity; a possible consequence might be that kinetochore proteins are deposited onto CEN-proximal CLRs due to crosslinking and spatial proximity. To rule out this possibility, and also to determine the dependence of CLR formation on the pericentric loop, we repeated ChIP-qPCR analyses but in a cohesin-deficient mcd1-1 background. In strains with normal Cse4 levels (WT) in mcd1-1, results remained unchanged; no individual CLR showed significant binding for all four proteins (Figure 2C and Figure S4A). In strains with elevated Cse4 levels (Cse4 OP) in mcd1-1, binding of four kinetochore components was significant at each of six CLRs tested (CEN-proximal and CEN-distal CLRs) and did not differ greatly from strains with functional Mcd1 (Figure 2C and Figure S4B). These results suggest that formation of CEN-proximal CLRs is not a biological artefact from simply crosslinking higher-order interactions, and that an intact cohesin-dependent pericentric loop was dispensable for CLR formation or, at the very least, for maintenance of kinetochore components at CLRs.

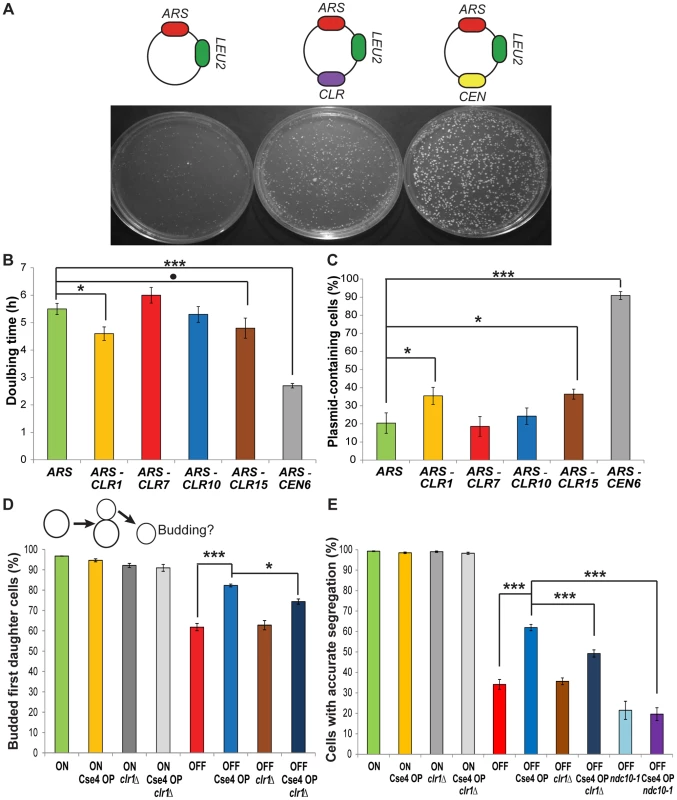

CLRs exhibit centromeric activity on plasmids and chromosomes

To determine whether CLRs act like centromeres, four different CLR sequences were tested in plasmid and chromosome segregation assays [17]. First, we asked if a CLR can function as a centromere on a plasmid containing an ARS. An ARS-only plasmid can replicate, but it is unstable and lost at high frequency [18], [19]. Addition of a CEN to an ARS plasmid renders it stable and efficiently transmitted to daughter cells [2]. CLR sequences were cloned into an ARS plasmid, and ARS-CLR plasmids (CLR plasmids) were compared to ARS-only (ARS plasmid) and ARS-CEN plasmids (CEN plasmid) (Figure 3A). After transformation of a Cse4 OP strain, two of the four CLR sequences tested (CLR1 and CLR15) produced colonies of intermediate size; these were larger than those obtained from ARS plasmids, but smaller than those from CEN plasmids (Figure 3A). Other CLR plasmids (CLR7 and CLR10) behaved like ARS plasmids. Consistent with the requirement for Cse4 recruitment to extrachromosomal plasmids for their segregation [20]–[23], the two apparently functional CLRs, CLR1 and CLR15, had higher enrichment values for Cse4 than CLR7 and CLR10 (mean PeakSeq ratios 5.05+/−0.78 vs. 2.41+/−0.17, similar trends with ChIP-qPCR). As another test of segregation proficiency, doubling times in selective medium (SC Raffinose/Galactose – LEU) were measured. CLR1 and CLR15 decreased doubling time compared to an ARS plasmid, but to a lesser extent than CEN plasmids (Figure 3B; MCMC simulation). To ask whether CLR plasmids are more stably maintained than ARS plasmids, we measured the fraction of cells that retained the plasmid after growth in non-selective medium (YPAU+Raffinose/Galactose) for ∼4 generations [17]. CLR plasmids were maintained in a significantly greater fraction of cells (35% for CLR1; 36% for CLR15) than ARS plasmids (20%) (Figure 3C; P = 0.036 for CLR1; P = 0.018 for CLR15; MCMC simulation). The CEN plasmid was maintained in 91% of cells (Figure 3C). Differences in colony sizes were observed upon plating on selective medium, similar to Figure 3A (Figure S5). To ensure that these observed differences in ARS and CLR plasmid stability did not result from a size-dependent increase in plasmid stability [24] when comparing ARS-CLR and ARS-only plasmids due to the additional insert, we repeated plasmid segregation assays (doubling times and plasmid retention) with ARS plasmids bearing random inserts of similar sizes to CLR inserts, respectively 1 kb for ARS-R1 and 0.8 kb for ARS-R2 (Figure S6). Statistical significance for ARS-CLR plasmids was re-assessed then in comparison to ARS-R1 or ARS-R2 and found to follow similar trends than those obtained with ARS-only plasmid as a control (Figure 3B–3C and Figure S6). Taken together, these results indicate that CLR sequences can enhance plasmid segregation.

Fig. 3. CLRs confer centromere function on plasmids and chromosomes.

(A) Top: Representation of ARS, CLR and CEN plasmids. Bottom: Transformation plates from strains carrying different plasmids. (B) Doubling times in selective medium of strains carrying different plasmids (Means+/−SEM). (C) Fraction of plasmid-containing cells after growth in non-selective media for strains bearing various plasmids (Means+/−SEM). P-values were computed using MCMC simulations (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001,. p = 0.07) (B–C). (D) Top: Depiction of pedigree assay. Unbudded mother cells contain a conditional CEN3 (ON raffinose; OFF galactose) or not (ON raffinose or galactose). Bottom: Fraction of budded daughter cells 12 h after transfer of mother cells to plates containing galactose (Means+/−SEM). ON and OFF indicate the presence of conditional CEN3. For the four left-most bars, similar values were obtained for strains with conditional CEN3 grown in raffinose (ON). A time course is shown in Figure S4. (E) Fraction of cells that segregated properly their GFP-labelled chromosome 3, as visualized by the presence of a GFP dot in each cell (Means+/−SEM). P-values have been calculated using Fisher's Exact Test (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001) (D–E). Second, we asked if a CLR can function in its natural context, on a chromosome, to promote proper segregation. Galactose-driven transcription towards a native CEN inactivates the kinetochore, thus creating a conditional centromere that can be switched off when cells are grown in galactose [25]. Two chromosome segregation assays were used to assess the stability of chromosome 3, carrying a conditional CEN3 and CLR1, the only naturally-occurring CLR on chromosome 3. First, segregation was monitored by pedigree analysis; bud emergence in a daughter cell was assayed after CEN inactivation in an unbudded mother cell (Figure 3D) [19]. Budding of a daughter cell indicates accurate segregation of the CEN-inactivated chromosome 3 in the previous mitosis [26]. When CEN3 is active, 95% of daughter cells are budded, in WT and Cse4 OP strains (Figure 3D and Figure S7). In contrast, when CEN3 is inactivated, significantly more daughters of Cse4 OP cells bud compared to WT (82% vs. 62%; P<10−5; Fisher's Exact Test (FET)). In a second assay, we followed segregation of a GFP-labeled chromosome 3 after a single nuclear division [17]. Normal equational chromosome segregation results in a single GFP dot in both cells, whereas improper segregation results in two GFP dots in the same cell. Accurate chromosome segregation dominates in both genotypes when CEN3 is active (Figure 3E). Cse4 OP partially rescues the missegregation of a CEN3-inactivated chromosome (Figure 3E; P<10−10; FET). This improvement in faithful chromosome segregation is weaker than that provided by a natural centromere or by a physically-tethered synthetic kinetochore [17]. Our results indicate that Cse4 OP enhances proper segregation of a chromosome with an inactive CEN. In C. albicans, Cse4 overproduction improves segregation in mutants defective in kinetochore proteins Dam1 and Dad2 [13]. While highly unlikely given the level of rescue observed, there is still a possibility that complete CEN3 inactivation might be hindered at a higher degree in Cse4 OP due to excess Cse4 molecules per se.

When CEN3 is inactive, Cse4 OP significantly improves the segregation of chromosome 3. To test whether this improvement is due to CLR activity, we deleted CLR1 by gene replacement and then monitored chromosome segregation by pedigree analysis and GFP imaging. In both assays, deletion of CLR1 decreased the Cse4 overproduction-dependent rescue of chromosome segregation, by 46% in the case of the budding assay and by 39% for the GFP dots assay (Figure 3D–3E; P = 0.03 and P<10−5, respectively; FET). To ensure that the observed decreased was caused by the loss of CLR1 and not by impacted kinetochore assembly at CEN3 arising from the experimental manipulation (gene replacement at CLR1), we verified binding of Cse4, Mif2, Ndc10 and Ndc80 at CEN3 in clr1 strains for WT and Cse4 OP. We found that binding levels of kinetochore components at CEN3 in clr1 strains were similar to those in CLR1+ strains, confirming that CEN3 integrity is intact in clr1 strains (Figure S8). This result would lend support to the conclusion that the reduction in the rescue observed in clr1 strains is not caused by changes at CEN3, but likely reflect the effect of CLR1 deletion. Taken together, these results suggest that overproduction of Cse4 can promote accurate segregation of CEN-inactive chromosomes, at least partly through CLR formation. The selective pressure caused by CEN inactivation might enhance the centromeric activity of CEN-proximal CLRs. The increased presence of kinetochore proteins around CENs upon Cse4 OP may also contribute to the rescue phenotype [13].

Ndc10 is a budding yeast-specific essential kinetochore component required for the centromeric localization of many proteins, including Cse4 [27], [28]. We asked whether the rescue in segregation of CEN-inactive chromosome 3 observed in Cse4 OP strains is dependent on Ndc10. The GFP dots assay on a single nuclear division was repeated in WT and Cse4 OP strains when CEN3 is inactivated, but now including the temperature-sensitive, conditionally-lethal ndc10-1 allele, well known to abolish centromere function and cause chromosome missegregation [29]. The rescue in accurate chromosome segregation of CEN-inactivated chromosome 3 previously observed in Cse4 OP compared to WT disappeared (Figure 3E), as levels of accurate chromosome segregation in these strains became indistinguishable in the presence of ndc10-1. Combining this result highlighting the dependence on Ndc10 for the rescue observed in Cse4 OP with the previous results suggesting that this rescue is at least in part dependent on CLR1 function (clr1 strains), the assembly of functional CLRs might share some similarities to that of native S. cerevisiae centromeres, such as the functional requirement on Ndc10. This is also supported by the significant binding of Ndc10 at CLRs determined by ChIP experiments.

CLRs share characteristics of both point and regional centromeres

How do CLRs compare to native S. cerevisiae CENs with regard to DNA sequence? Searching across all 23 identified CLRs for sequences similar to the centromeric CDEI or CDEIII consensus motifs did not yield clear results, nor did we find any motifs enriched amongst CLR sequences. CLR sequences tend to encompass a significantly AT-enriched, 90-bp stretch of DNA (Figure 4A; P = 0.042; MCMC simulation), reminiscent of the highly AT-rich CDEII element [30]. CDEII is the site where Cse4 binds [3], and it shares similarities to the alpha-satellite DNA repeats in the regional CENs of higher eukaryotes [30]. Cse4 is essential for segregation of the multicopy 2 µm plasmid endogenous to yeast; this plasmid lacks a centromere and instead relies on Cse4 association with an AT-rich partitioning locus known as STB [31]. A chromosomally-integrated STB can also recruit Cse4 [31].

Fig. 4. Genomic features of CLRs.

(A) Comparison of CLRs and CENs. Average value refers to the fraction of CLRs or CENs located within 25 kb of a CEN or within 5 kb of an ARS, tRNA or retrotransposon. Mean intergenic indicates the average length of intergenic regions. Max AT represents the mean AT content of the most AT-rich 90-bp stretch of DNA. (B) CLRs can be separated from other genomic regions, using Discriminant Analysis (DA). Scores of CLRs (blue) and negative control regions (red) are plotted according to their discriminant function scores (Table 2). (C) Centromere proximity is a major contributor to variability among CLRs, as revealed by Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Scores of CEN-proximal (<25 kb, blue) and CEN-distal (>25 kb, red) CLRs are plotted relative to the first and second principal components (Table 3), along with a 95% confidence ellipse. (D) Conservation of CLR sequences among organisms with point CENs (blue), but not with fungi bearing regional CENs (black). Nucleotide blast (Blastn) was performed for 23 CLRs and 160 random intergenic regions. Mean BLAST scores are reported, with the percent of hits with a score over 45 (E<0.05) in parentheses. (E) Given our data and the confinement of CLR sequences to budding yeast bearing point centromeres, we proposed a modified version of the current model of centromere evolution (originally postulated in [1]), from regional to point CENs, to account for CLRs. CLRs would represent evolutionary remnants from regional CENs. Some AT-rich CEN repeats would have diverged but still retained the ability to bind Cse4 and other kinetochore proteins weakly, giving rise to the low-affinity CLRs observed in this study. Which genomic characteristics best describe CLRs? In addition to their proximity to CENs (Figure 4A; P<10−5; randomization tests), CLRs are often associated with ARSs, but not with tRNAs or retrotransposons (Figure 4A; randomization tests). They are also found in larger than average intergenic regions (Figure 4A; P = 0.012; randomization tests). These genomic features parallel those common at regional centromeres and neocentromeres of other yeasts. In particular, neoCENs in C. albicans (activated by deletion of a native CEN) form mostly in large intergenic regions, and they are closely associated with replication origins [32], [33]. Gene ontology analysis of genes closest to CLRs did not reveal any enrichment for genes involved in particular cellular process (P<0.01).

Non-centromeric Cse4 binding marks a subset of open chromatin sites

In Cse4 OP cells, fewer than 2% of non-centromeric Cse4 sites are also bound by all of the other three kinetochore proteins. To characterize non-centromeric Cse4 regions (both CLR and non-CLR regions), we compared Cse4 binding profiles to the genome-wide distribution of RNA polymerase II and Sono-Seq regions. Sono-Seq regions correspond to sites of highly-accessible chromatin [34]. Cse4 is incorporated mostly at intergenic and promoter regions (95% of Cse4 sites), in particular open chromatin (Figure S9). Cse4 binding is also correlated with overlapping or adjacent RNA polymerase II occupancy (Figure S9; Spearman's ρ = 0.32; P<10−8). Cse4 has been shown to undergo proteolysis to ensure physiological levels and protect from extensive stable euchromatinization with deleterious effects [35]. Comparing strains overproducing the more stable Cse4 allele Cse4K16R, subject to reduced degradation [35], to strains overproducing normal Cse4, we asked whether non-degradable Cse4 binds preferentially at CLRs. From ChIP-qPCR analyses, Cse4K16R shows increased localization to the previously-tested CLRs (Figure 2B and Figure S3B) and to a set of non-CLR Cse4 binding sites located in gene promoters, but this enrichment occurs at similar levels in both CLRs and non-CLR Cse4 binding regions (Figure S10). Consistent with our finding that only a minority of Cse4 binding sites in Cse4 OP form CLRs, these results suggest that increased Cse4 retention alone does not appear to be the only determining factor in CLR formation.

Scm3 (HJURP) is a CEN-associated chaperone essential for cell viability [36]. Deletion of SCM3 is suppressed by Cse4 OP [12]. By comparing Cse4 ChIP-Seq profiles in the presence or absence of SCM3, we found that Cse4 binding sites in both genotypes were highly concordant (Figure S11; Spearman's ρ = 0.85; P<10−15), suggesting that non-centromeric localization of Cse4 does not require Scm3. This finding is supported by the fact that transient incorporation of Cse4 on non-centromeric sites occurs at regions of high histone turnover, linking this phenomenon with nucleosome incorporation and ejection dynamics [37]. Cse4-containing nucleosome physical structure might also provide some potential reasons for the Scm3-independent Cse4 incorporation at non-centromeric loci. From in vitro reconstitution of Cse4-containing nucleosomes, two distinct populations of Cse4 nucleosomes have been reconstituted: one resembling canonical octameric nucleosomes and another found primarily at t AT-rich DNA characteristic of CENs, atypical in its inclusion of Scm3 [38]. The former might predominate throughout the genome, while the latter would be highly specific for centromeres [39].

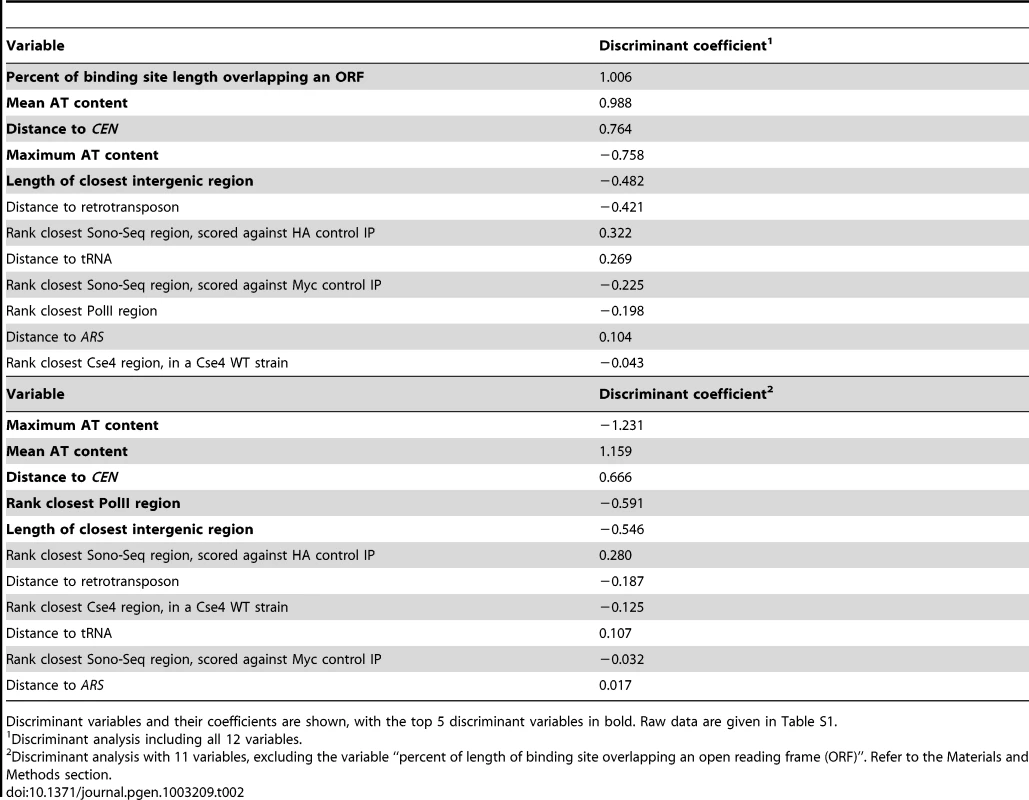

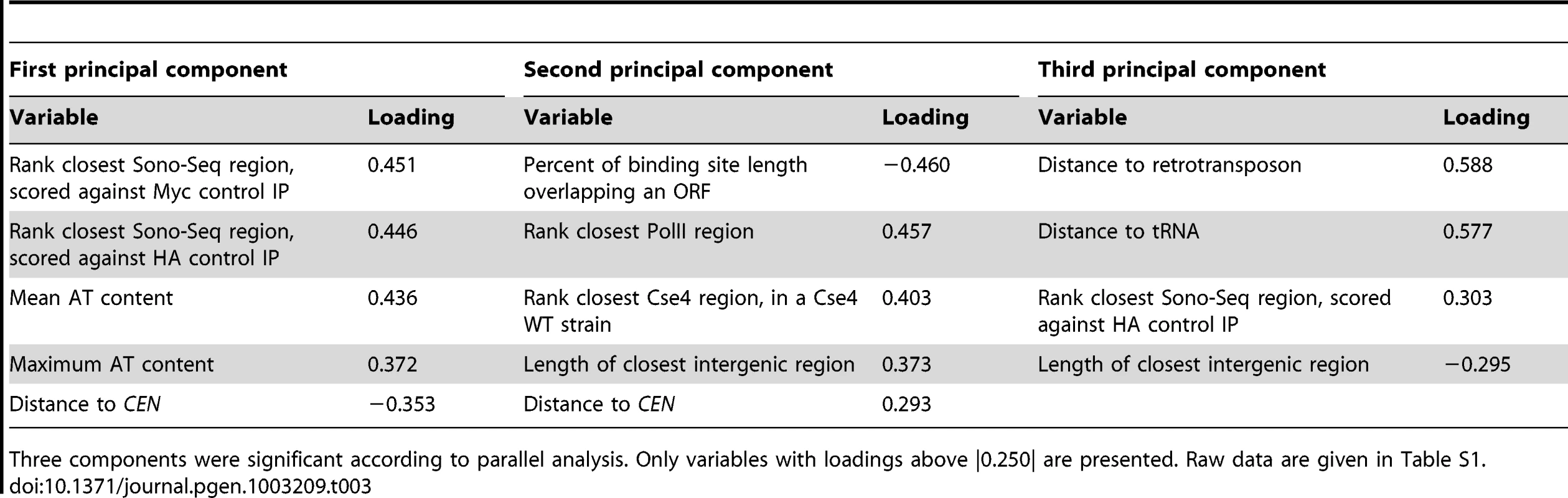

Genomic context influences CLR formation

Twelve different variables (Table S1) were examined in an effort to find factors that distinguish CLRs from a control group consisting of regions that did not pass statistical filters set during ChIP-Seq analysis (Table 1); these control regions are referred to as LCNCRs (low-confidence, negative control regions). CLRs differed from the control group globally and across three individual variables: distance from CENs, overlap with an intergenic region, and nearby RNA polymerase II occupancy (P<0.05; MANOVA; ANOVA). Group membership of individual sites could be predicted quite accurately using discriminant analysis or k-means clustering (78% and 83% success, respectively; Figure 4B and Table 2). As determined by discriminant analysis, we found that CLRs are closer to CENs, have a more AT-enriched 90-bp stretch of DNA, and are located in larger than average intergenic regions, with lower transcription at nearby genes, in comparison to the control group (Figure 4B and Table 2). This difference between CLRs and LCNCRs is quite apparent from the discriminant function plot, with low mixing between groups (Figure 4B). There is, however, some variation among CLRs with respect to distance from CENs, AT content and the presence of nearby open chromatin, as revealed by principal component analysis (Figure 4C and Table 3). CEN-distal and CEN-proximal CLRs form somewhat separated groups on the principal component score plot, and sites within each group tend to cluster together, as is particularly evident for CEN-distal CLRs (Figure 4C). In addition, when performing a discriminant analysis among the CLRs themselves according to their position in the ranked target list (Table 1; group 1 (CLR1–12) vs. group 2 (CLR13–23)), we observed that the strongest discriminant was the distance to CENs, with CLRs in the top tier usually closer to CENs. This is consistent with our previous observations from the ChIP-Seq data. The proximity of CLRs to centromeres suggests that pericentric chromatin creates a preferred environment for establishment of CLRs [14]. Alternatively, centromere-distal CLRs may be disfavored due to a greater risk for instability, in the same way that increased distance between CENs in dicentric chromosomes increases instability [40]. These results strongly suggest that chromatin structure and chromosomal context play roles in CLR formation.

Tab. 2. Results from linear discriminant analysis of 23 CLRs and 38 negative control regions (LCNCRs).

Discriminant variables and their coefficients are shown, with the top 5 discriminant variables in bold. Raw data are given in Table S1. Tab. 3. Results from principal component analysis of 23 CLRs.

Three components were significant according to parallel analysis. Only variables with loadings above |0.250| are presented. Raw data are given in Table S1. Conservation of CLR sequences and chromosomal context elements

CLR-containing regions are conserved among the Saccharomyces lineage and other closely-related budding yeasts with point CENs [41], but not with more divergent fungi (Figure 4D; blastn). In general, CLR sequences are more conserved than a randomly-selected set of intergenic regions (Figure 4D; P<0.05 across Saccharomyces sensu stricto; MCMC simulation of blastn scores). Although the role of CLRs in wild populations of yeasts remains unknown, sequence conservation with other budding yeasts suggests that CLRs possess a conserved function.

With the development of the new Saccharomyces sensu stricto database [42], it is possible to analyse some of the genomic characteristics and chromosomal context features, including the association to CENs, the association to tRNAs, the mean length of intergenic regions, and the mean AT content in the most AT-enriched 90-bp stretch of DNA, in closely-related budding yeast. Trends similar to those observed for S. cerevisiae CLRs were observed for sequences similar to CLRs present in S. mikatae, S. kudriavzevii and S. bayanus (Figure S12). Proximity to CENs was even more striking in those three fungi than in S. cerevisiae (Figure S12A). In the three non-S. cerevisiae fungi analyzed, CLR-related sequences were also present in larger than average intergenic regions and encompassed a significantly AT-enriched, 90-bp stretch of DNA (Figure S12). The only difference concerned association with tRNAs: while CLR association to tRNAs was only marginally significant in S. cerevisiae and S. bayanus, it was significant in S. mikatae and S. kudriavzevii, although very close to P<0.05 significance threshold. In addition to primary sequence conservation, these results highlight the conservation of genomic features and chromosomal context elements associated with CLRs in closely-related budding yeasts.

Overall, CLRs share many features with both regional and point centromeres. Like regional CENs, CLRs are not entirely sequence-defined; rather, they are defined largely by features pertaining to chromosomal context. Like point CENs, they are rather small (<1 kb) and contain a short CDEII-like, AT-rich stretch of DNA. According to previous models of centromere evolution, an epigenetic regional centromere evolved to point centromeres in a few steps [1]. First, heterochromatin would be loss. Then, CEN repeats would diverge and/or disappear. Third, a segregation locus from a self-propagating genetic element (such as the STB locus in the yeast 2 µm plasmid) would integrate on the chromosome, with the potential to successfully hijack the segregation machinery. Once this is accomplished, it is likely that CEN repeats would diverge or disappear even more. Finally, acquisition of specific DNA modules and evolution of segregation proteins that bind this newly-integrated locus would create point centromeres with high specificity. If this model is correct, then CLRs may be remnants of regional CENs that were lost or diverged during evolution (Figure 4E). CLRs might resemble divergent AT-rich CEN repeats, able to bind Cse4 and function as a strong centromere unit in the past, that still retained some ability to recruit Cse4, and other kinetochore proteins weakly. This is the model most supported by parsimony and by our evolutionary analyses. Indeed, using a bioinformatics approach, we identified CLR sequences only in budding yeast bearing point CENs, not in those carrying regional CENs. In general, centromeric building blocks with weak activity, such as an individual CEN repeat, a plasmid element or a short sequence similar to a CLR, might have been rendered more efficient through their massive multimerization (regional CENs) or, as in the S. cerevisiae lineage, through the acquisition of specific DNA modules (point CENs and STB) to form stable, strong centromeres with high segregation fidelity.

CLR formation affects chromosome segregation differently, depending on whether the chromosome has an active centromere or not. Recent data from an assay measuring the transmission fidelity of an artificial chromosome indicated a significant, although modest, increase in chromosome loss (about 2 fold) when Cse4 is overproduced and the normal centromere is functional [43]. In Cse4 OP, when the CEN is active, the observed increase in chromosome instability is likely due to the formation of functional CLRs in a subset of the cell population. The modest effect is concordant with the lower levels of protein binding at CLRs vs. CENs, and with the higher incidence of CEN-proximal CLRs. Based on studies of dicentric chromosomes, CEN-proximal CLRs have potentially less deleterious effects than CEN-distal CLRs [40]. In contrast, when the normal CEN is inactive, CLR formation promotes, at least partially, accurate chromosome segregation of the CEN-inactivated chromosome, which might be beneficial to yeast cells under this condition.

New CENs have been created artificially through two mechanisms: tethering of outer kinetochore components onto DNA [17], and increased production of kinetochore proteins [44]. At the DNA level, strategies to generate centromere activity have ranged from deletion of a native CEN in C. albicans [33] to induction of chromosome rearrangements by radiation in flies and plants [45]. Interestingly, studies in Drosophila and barley have revealed a predisposition for neoCENs to form in pericentric chromatin [45]. More recently, studies conducted on in vitro chromatin templates [46] and in cultured Drosophila cells [47] have reiterated the essential role of Cse4 and proven its sufficiency in the formation of kinetochores. Targeting Cse4 [46], [47] or Cse4-associated factors [48] directly onto chromosomes or plasmids can generate heritable centromeric activity. However, despite the deposition of Cse4 at a specific location, not all cells recruited kinetochore components and established a kinetochore, presumably due to chromatin effects [48]. Similarly, in the present study, we observed CLR formation only at a subset of all non-centromeric Cse4 binding sites.

New CENs also occur naturally. In humans, acentric chromosomes resulting from chromosome rearrangements can be stabilized through the establishment of neocentromeres at sites devoid of α-satellite repeats and containing little or no heterochromatin [49]. The aneuploidy so often observed in cancer cells may arise from ectopic kinetochore formation and/or destabilization of native CENs. Many liposarcomas carry a supernumerary chromosome containing oncogenes and a neoCEN [45]. Colorectal cancer cells exhibit overproduction of Cse4, which is mistargeted to non-centromeric loci [4]. Moreover, comparative genomics has identified latent CENs that have been recurrently used throughout primate evolution [50]. CLRs, evolutionarily-new centromeres, ectopic neocentromeres and bacterial centromere-like regions are likely to provide additional insights into the origin, evolution, establishment and maintenance of native centromeres.

Materials and Methods

Strains and plasmids

Yeast strains are isogenic with W303 (Table S2). Cse4 is tagged internally with a 3HA epitope; this tagged version can act as the sole Cse4 copy in a haploid cell without deleterious effect [5]. All other proteins are tagged at their C-termini. The ARS plasmid (pPL26) was generated by cloning a 0.9 kb fragment containing ARS1 into pRS305 [18]. CLR and CEN6 sequences were integrated into pPL26. ARS-CEN6 plasmid pRS315 was also used in this study.

Chromatin immunoprecipation–sequencing (ChIP–Seq)

ChIP-Seq experiments were performed at least in independent biological duplicates, as described previously [9]. Yeast strains were grown in 500 mL YP media supplemented with adenine and uracil, in presence of glucose or galactose/raffinose, to mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.5–0.7). Proteins were crosslinked to DNA by treating cells with formaldehyde (1% final concentration) for 15 minutes, then quenched with glycine. Cells were collected by filtration after two washes. After cell lysis using a FastPrep machine (MP Biomedical), chromatin was sheared by sonication using a Branson Digital 450 sonifier (Branson). Clarified, sonicated lysates were taken at this step for Sono-Seq, prior to immunopreciptation [34], [51]. Immunoprecipitations of Myc-tagged and HA-tagged strains, as well as those of the respective control untagged strains, were carried out overnight with EZ-View anti-Myc or anti-HA affinity gels (Sigma). For native RNA Polymerase II ChIP, cell lysates were incubated with Pol II 8WG16 mouse monoclonal antibody (Covance) and pulled down using Protein G agarose beads (Millipore). After several washes and reversal of protein-DNA crosslinks, ChIP DNA was purified through a Qiagen MinElute PCR purification column (Qiagen). Illumina sequencing libraries were generated using adapters for multiplexing [9]. Four barcoded libraries were mixed in equimolar ratios and processed on an Illumina Genome Analyzer II. Each sequence read consisted of a 4-bp index and at least 26 bp from the sample. An average of 2.1 million uniquely mapping sequence reads per biological replicate was obtained, corresponding to an overall mapping of 56.2% to the S288c reference genome (SGD/UCSC sacCer2 version, June 2008). We have also used previously published Cse4 ChIP-Seq data deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under GSE13322 [5], [52]. Data generated from this study have been deposited in GEO under accession number GSE31466.

To collect ChIP samples of mcd1-1 background, cultures were grown overnight at the permissive temperature (25°C) to OD600 = 0.3–0.4 and then shifted to the restrictive temperature (37°C) for ∼2.5 h prior to crosslinking, similarly to other protocols for the abrogation of the pericentric intramolecular C loop [14]. After ∼2.5 h, most cells (>95%) were large-budded.

To collect ChIP samples for the non-degradable Cse4 experiment [35], Myc-Cse4 and Myc-Cse4K16R strains were grown in SC Raffinose/Galactose – URA overnight to OD600 = 0.3, overproducing normal and non-degradable Cse4 respectively. Cells were then transferred in rich media (YPAU+Raffinose/Galactose) and grown for ∼4 h to OD600 = 0.8–1.0, for easier comparison with our previous ChIP-qPCR data.

Identification of CLRs

Raw sequencing data were first processed by Illumina's analysis pipeline. Reads were then parsed according to the index. Remaining bases were aligned against S. cerevisiae S288c reference genome version 2 (SGD/UCSC sacCer2) by the ELAND algorithm (Illumina). The peak scoring algorithm PeakSeq [10] was used to identify statistically significant binding sites. ChIP-Seq data from epitope-tagged strains were scored against ChIP-Seq data from their matching untagged strains. Scoring reference sets were created by pooling uniquely-mapping reads from biological replicates of untagged control strains. As a reference sample marking open chromatin [34], two lists of Sono-Seq regions were generated, scored against either anti-Myc or anti-HA control sets.

To uncover CLRs, we took a conservative, stringent approach to minimize false positives lacking functional significance or failing qPCR validation. For each biological replicate, only putative regions with q-value <10−5 were considered [11]. Binding sites from Cse4, Mif2, Ndc10 and Ndc80 ChIP-Seq data were overlapped (maxgap = 150). To identify a binding region as a CLR, 1) all four kinetochore proteins must be present given the q-value threshold; and 2) for proteins in direct contact with DNA, mean PeakSeq ratios between duplicates should be above 2.0 for open chromatin marker Cse4 and 1.5 for direct DNA binders Mif2 and Ndc10 [5], [53]. Several other filters were used to distinguish between low and high confidence regions for subsequent functional analyses, including comparison of PeakSeq experimental and background reads between CLRs and CENs, inspection of normalized signal tracks (high tagged/untagged ratio and low background in untagged controls desired), binding over a highly PolII-occupied ORF, and presence in HOT regions [54]. 23 putative loci, termed CLRs, met these criteria in Cse4 OP and none in WT (Table 1). Included in the same Table are other sites (LCNCRs) that did not pass the aforementioned filters, used during computational analyses. For WT, only one low-confidence negative region, the rDNA array, was found after unmasking for repeated regions. GO analysis for this control group showed a significant enrichment for metabolic genes.

Significant binding regions for RNA Polymerase II and Sono-Seq were determined using q<10−5 and PeakSeq ratio ≥2.00.

Real-time quantitative PCR validation of CLRs

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed to validate the presence of kinetochore components Cse4, Mif2, Ndc10 and Ndc80 at six CLRs. These six CLRs were randomly selected and spanned multiple confidence levels of our final ranked target list (one at the top, two in the middle, and three at the bottom) [55], [56]. As a positive control for ChIP experiments, we monitored binding of these four proteins at a native centromere. Two negative primer pairs were used for accurate determination of enrichment values. Primers were designed using Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/) and primer sequences are given in the Table S3. qPCR reactions were set up in triplicates with SYBR green dye and run on a Roche LightCycler480 according to the manufacturer's recommendations, using the same amplification program as previously described [5]. Each primer pair was tested on a dilution series of yeast genomic DNA to determine its efficiency. For every primer pair, a single PCR product was amplified, given the presence of a single peak in melting curve analyses. The “Second derivative maximum” analytical tool in the Roche LightCycler480 was used to obtain Crossing point values (Cp). Enrichments were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCp method [57]. First, for any given primer pair, a raw ratio between experimental samples (Myc - or HA-tagged strains) and control samples (untagged strains of similar genotype immunopreciptated with anti-Myc or anti-HA antibodies) was obtained. Then this raw ratio for a positive primer pair was divided by the raw ratio found for a control, negative primer pair, resulting in a normalized enrichment value. Enrichment values were averaged for all biological replicates, with the appropriate standard errors of the mean.

Signal tracks

Signal track files were visualized in the Integrated Genome Browser, with y-axes scaled according to the number of uniquely-mapped reads and with annotations from the Saccharomyces Genome Database.

Target list annotation, target list agreement, and Gene Ontology analysis

Target lists from different biological replicates were merged and annotated to find overlapping and/or nearest genomic features using various R and Bioconductor packages, mostly ChIPpeakAnno [58], and also biomaRt, coda, lattice, MASS, rjags, seqinr and stats packages.

Target lists were first sorted by q-value and then by the difference between PeakSeq experimental and background reads. Pairwise comparisons of lists were done using ChIPpeakAnno with parameters maxgap = 0 and multiple = T. Spearman's rank correlation coefficients and associated p-values for overlapping peaks were computed.

GO Biological Process Ontology analyses (p-value <0.01) were performed on SGD's website. We compared GO results from CLRs and LCNCRs. GO analysis for CLRs did not give any significant term. GO analysis for LCNCRs showed a significant enrichment for metabolic genes (data not shown).

Western blotting

Whole-cell protein extracts were obtained using the post-alcaline yeast protein extraction method [59], for 4 biological replicates. Briefly, for WT and Cse4 OP strains, 2 mL of yeast culture at OD600 = 0.8 were isolated, medium was removed and cells were frozen at −80°C. Cells were resuspended in water, an equal volume of 0.2 M NaOH was added and samples were incubated at room temperature for 5 min., after which NaOH was removed thoroughly. Samples were then boiled in 1× sample buffer containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol for 4 min. and the supernatant was kept. Samples were run for protein gel electrophoresis on a 4–12% Novex NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) in MOPS buffer. Proteins were then transferred a PDVF membrane on a semi-dry Trans-Blot SD apparatus (BioRad). Membranes were blocked with TBS+0.1% Tween with 5% dry milk. Primary antibodies were added for an overnight incubation: mouse anti-HA 12CA5 and mouse anti-β-actin (Abcam). After washes in 1× TBS+0.1% Tween, a HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody was added in 1× TBS+0.1% Tween with 5% dry milk for 1.5 h. Following washes in 1× TBS/T, the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo) was added to the blot and detection was done on a STORM imager (GE Healthcare). Western blot images were processed and analyzed using the ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare). Cse4-3HA protein levels were normalized by the abundance of β-actin in each replicate.

Plasmid stability assays

Plasmid assays to test CLR sequences inserted into an ARS plasmid were conducted according to standard procedures [2], [18]. For all plasmid analyses, at least six different transformants were grown. Given that we observed some variability in plasmid assays, we used fluctuation analyses for each data point, taking the median value of 3–5 technical replicates from a single transformant as one data point [60].

For doubling time analyses, cells were grown overnight in synthetic complete (SC) media lacking leucine (SC-Leu), with raffinose and galactose as carbon source. Cultures were diluted around 5×106 cells in the same media. Optical densities were measured every 2–4 hours. Doubling times were calculated in R. Statistical significance was tested by a Bayesian analysis with Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), using R package rjags (JAGS, http://www-ice.iarc.fr/~martyn/software/jags/). MCMC simulations let the data and its variability generate sampling distributions of the maximum likelihood estimator without strong prior or test assumptions; p-values were calculated from 100,000 comparisons of this estimator between 2 groups.

For plasmid retention and colony formation analyses, cells were grown for ∼4 generations in rich medium, with raffinose and galactose as carbon sources. Cultures were diluted 10-fold or 100-fold and plated on SC-Ade-Leu and SC-Ade plates. Photos were taken after 4 days of growth. Pictures of transformation plates on SC-Ade-Leu with galactose/raffinose also represent 4 days of growth after transformation.

Chromosome segregation assays

Chromosome segregation analysis of GFP dots present on chromosome 3 was performed in biological triplicates as described [17], without major modifications. Briefly, cells were grown overnight to early log phase in rich medium containing raffinose, and alpha factor was then added to a final concentration of 10 µg/mL. Following a 2 h incubation at 25°C, cultures were resuspended in YPAU with raffinose/galactose or raffinose only, still in presence of alpha factor, and then placed at 37°C for 1 h. Next, cells were washed 4 times in the same media, pre-warmed at 37°C and devoid of alpha-factor, and released at 37°C for about 5 h to accumulate populations in which most cells were in telophase due to the cdc15-2 allele. Experiments including the additional temperature-sensitive allele ndc10-1 were performed similarly. About 98% of cells were large-budded. GFP dots were visualized in live cells and classified into two categories: 1) one GFP dot in each cell, or 2) two GFP dots in the same cell. A minimum of 200 cells were counted per replicate. Statistical significance was assessed using Fisher's exact test. In addition, for each sample, an aliquot was quick-fixed with ethanol and DAPI was added. >90% of cells had segregated DNA between their buds, as revealed by DAPI staining. Experiments plotted in Figure 3E were from cultures resuspended in raffinose/galactose, containing a conditional CEN3 (OFF) or not (ON). Strains comprising conditional CEN3 were also resuspended in raffinose-only media (ON) and gave similar high percentages of cells with accurate segregation. Overnight growth of cells in raffinose-only media, with an active conditional CEN3 (ON), yielded >99% of cells with accurate segregation.

Single-cell pedigree analysis was performed on strains containing a conditional centromere [19], [25]. Cells were grown to early log phase in YPAU+raffinose. Galactose was added to the liquid medium for ∼30 min. (final concentration 1%), prior to plating on a YPAU+galactose/raffinose plate. Unbudded cells were isolated, and plates were incubated for 2–3 hours. Daughter cells were separated from their mothers and monitored for bud formation as a function of time. Statistical significance was assessed using Fisher's exact test. To ensure proper timing of cell divisions in Figure 3D and in Figure S7, cells containing a conditional CEN3 (OFF) or not (ON) were plated on galactose/raffinose plates. Strains comprising conditional CEN3 were also plated on YPAU+dextrose plates (ON) and gave end-point results comparable to those of Figure 3D, with >90% of budded daughter cells.

Statistical significance of CLR association

We determined the number of CLRs located within 5 kb of tRNAs, ARSes or retrotransposons. 23 sites were randomly chosen on chromosomes containing a putative CLR. The number of chosen sites on a chromosome paralleled the chromosomal distribution of CLRs. The number of random sites falling within 5 kb of a feature was determined for 100,000 iterations. The p-value is given by the fraction of iterations with greater or equal feature association than found across CLRs. For these discrete genomic features, we adjusted p-values using a Bonferroni correction.

For centromere proximity, a similar procedure was followed. A site is centromere-proximal if located within 25 kb of the centromere.

For association tests performed in other fungi than S. cerevisiae, the number of random sites chosen followed the number of CLR sequences deemed conserved by blastn in each species (Figure 4A): 17 in S. mikatae, 18 in S. kudriavzevii and 15 in S. bayanus. Sequence annotation data were obtained from the Saccharomyces sensu stricto database [42].

Statistical significance of the presence of CLRs in larger than average intergenic regions

We considered the region comprised between two ORFs as the intergenic region. The mean length of intergenic regions encompassing a CLR was determined, excluding two CLRs that partly overlapped putative ORFs. 21 intergenic regions were randomly selected 100,000 times. For any iteration, the mean length was computed and compared to the actual value. P-values correspond to the fraction of iterations with a greater or equal mean length.

In other fungi than S. cerevisiae, the number of random intergenic regions chosen followed the number of CLR sequences found in intergenic regions and deemed conserved by blastn in each species (Figure 4A): 17 in S. mikatae, 18 in S. kudriavzevii and 15 in S. bayanus. Sequence annotation data were obtained from the Saccharomyces sensu stricto database [42].

Signal aggregation plots around centromeres

For each protein and for untagged controls, we determined the number of uniquely mapped reads, per million mapped reads, at every nucleotide position in a 4-kb region centered in the middle of the centromere. Values for each protein were averaged to generate a mean kinetochore protein signal. Log ratios between this signal and the control signal were plotted. Aggregation plots around CEN2 and CEN5 for individual proteins are given in Figures S13 and S14 respectively.

To test the significance of the increased broadness of kinetochore signal seen at centromeres, we calculated the peak width at each centromere. Width was determined as the length of centromeric signal where the ratio between the mean kinetochore protein signal and the control signal was ≥2. A paired t-test, comparing each CEN between WT and Cse4 OP, was performed.

Maximum AT content

For 23 CLRs and 38 LCNCRs, a 90-bp window was slid to determine the maximum AT content in a 500-bp region, centered at the genomic location of the average kinetochore protein signal maximum, keeping the percentage of A and T in the most AT-rich, 90-bp stretch. Maximal values from CLRs and LCNCRs were compared for statistically-significant differences by MCMC simulations. A similar procedure was used for other fungi than S. cerevisiae, with sequence data obtained from the Saccharomyces sensu stricto database [42].

CLR sequence comparison across fungal genomes

For each CLR, a 400-bp sequence, centered at the genomic location of the average kinetochore protein signal maximum, was considered for evolutionary analyses. Inspection of the selected regions was carried out to ensure that the sequences did not contain repetitive and/or highly conserved features, such as a Ty element or a well-characterized ORF, if possible. Nucleotide BLAST (Blastn) was performed on genomes deposited at NCBI (NCBI's Fungal Genomes BLAST page, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sutils/genom_table.cgi?organism=fungi) with the following parameters: expect value (E) <1, and other values as default [61].

A phylogenetic tree indicates, for each species, the fraction of CLRs with at least one significant hit (score of 45 or higher, E<0.05) and the average hit score across all CLRs.

We compared CLR values with 160 randomly-selected intergenic regions of same length to determine whether sequence conservation is greater in CLRs. Blastn was carried out as described above for this random set. Statistical significance of average blastn scores was tested by MCMC simulations.

Principal component and discriminant analyses

For 23 CLRs and 38 LCNCRs, data from 12 variables were obtained (Table S1). Individual variables were either 1) left untransformed, 2) log-transformed, or 3) square root-transformed to normality or near-normality as visualized by quantile-quantile normal plots. Data from all 61 sites, or from each group, followed a multivariate normal distribution (Figure S15). On multivariate χ2 plots, all data points lie within the 95% confidence intervals of multivariate normality (Figure S15).

Principal component analysis was performed for the 23 high-confidence CLRs only, with data standardized by the correlation matrix, in R. Principal component analysis gives the direction of most variability to spread out data points and determine variables and sites that behave similarly. The number of significant principal components was determined by parallel analysis. Principal component score plots were generated using the first (x-axis) and second (y-axis) principal components. A 95% confidence ellipsis was added to the score plots.

Linear discriminant analyses between CLRs and LCNCRs were performed on standardized, scaled data in R, to identify variables that would distinguish these two well-defined groups. When all 12 variables were present, the percentage of a binding site overlapping an ORF was a very strong discriminator but could be perceived as arbitrary, depending on the length of the binding site. Therefore discriminant analysis was also performed with all variables except that one. Discriminant score plot was generated using the discriminant function with all variables (x-axis) and the discriminant function with all variables except percent overlap with an ORF (y-axis). We used stepwise discriminant analysis to determine the variables that discriminate best between groups, in SAS, and also obtained similar results. Overall discriminative power was tested using cross-validation (leave-one-out classification). As a comparison, k-nearest neighbors classification was performed on the same scaled, standardized dataset, using k = 3.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. MalikHS, HenikoffS (2009) Major evolutionary transitions in centromere complexity. Cell 138 : 1067–1082.

2. ClarkeL, CarbonJ (1980) Isolation of a yeast centromere and construction of functional small circular chromosomes. Nature 287 : 504–509.

3. MeluhPB, YangP, GlowczewskiL, KoshlandD, SmithMM (1998) Cse4p is a component of the core centromere of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 94 : 607–613.

4. TomonagaT, MatsushitaK, YamaguchiS, OohashiT, ShimadaH, et al. (2003) Overexpression and mistargeting of centromere protein-A in human primary colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 63 : 3511–3516.

5. LefrancoisP, EuskirchenGM, AuerbachRK, RozowskyJ, GibsonT, et al. (2009) Efficient yeast ChIP-Seq using multiplex short-read DNA sequencing. BMC Genomics 10 : 37.

6. CrottiLB, BasraiMA (2004) Functional roles for evolutionarily conserved Spt4p at centromeres and heterochromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Embo J 23 : 1804–1814.

7. HewawasamG, ShivarajuM, MattinglyM, VenkateshS, Martin-BrownS, et al. (2010) Psh1 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the centromeric histone variant Cse4. Mol Cell 40 : 444–454.

8. RanjitkarP, PressMO, YiX, BakerR, MacCossMJ, et al. (2010) An E3 ubiquitin ligase prevents ectopic localization of the centromeric histone H3 variant via the centromere targeting domain. Mol Cell 40 : 455–464.

9. LefrancoisP, ZhengW, SnyderM (2010) ChIP-Seq using high-throughput DNA sequencing for genome-wide identification of transcription factor binding sites. Methods Enzymol 470 : 77–104.

10. RozowskyJ, EuskirchenG, AuerbachRK, ZhangZD, GibsonT, et al. (2009) PeakSeq enables systematic scoring of ChIP-seq experiments relative to controls. Nat Biotechnol 27 : 66–75.

11. ZhengW, ZhaoH, ManceraE, SteinmetzLM, SnyderM (2010) Genetic analysis of variation in transcription factor binding in yeast. Nature 464 : 1187–1191.

12. CamahortR, ShivarajuM, MattinglyM, LiB, NakanishiS, et al. (2009) Cse4 is part of an octameric nucleosome in budding yeast. Mol Cell 35 : 794–805.

13. BurrackLS, ApplenSE, BermanJ (2011) The Requirement for the Dam1 Complex Is Dependent upon the Number of Kinetochore Proteins and Microtubules. Curr Biol 21 : 889–896.

14. YehE, HaaseJ, PaliulisLV, JoglekarA, BondL, et al. (2008) Pericentric chromatin is organized into an intramolecular loop in mitosis. Curr Biol 18 : 81–90.

15. StephensAD, HaaseJ, VicciL, TaylorRM2nd, BloomK (2011) Cohesin, condensin, and the intramolecular centromere loop together generate the mitotic chromatin spring. J Cell Biol 193 : 1167–1180.

16. AndersonM, HaaseJ, YehE, BloomK (2009) Function and assembly of DNA looping, clustering, and microtubule attachment complexes within a eukaryotic kinetochore. Mol Biol Cell 20 : 4131–4139.

17. LacefieldS, LauDT, MurrayAW (2009) Recruiting a microtubule-binding complex to DNA directs chromosome segregation in budding yeast. Nat Cell Biol 11 : 1116–1120.

18. SikorskiRS, HieterP (1989) A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122 : 19–27.

19. MurrayAW, SzostakJW (1983) Pedigree analysis of plasmid segregation in yeast. Cell 34 : 961–970.

20. HajraS, GhoshSK, JayaramM (2006) The centromere-specific histone variant Cse4p (CENP-A) is essential for functional chromatin architecture at the yeast 2-microm circle partitioning locus and promotes equal plasmid segregation. J Cell Biol 174 : 779–790.

21. IvanovD, NasmythK (2005) A topological interaction between cohesin rings and a circular minichromosome. Cell 122 : 849–860.

22. KeithKC, BakerRE, ChenY, HarrisK, StolerS, et al. (1999) Analysis of primary structural determinants that distinguish the centromere-specific function of histone variant Cse4p from histone H3. Mol Cell Biol 19 : 6130–6139.

23. AkiyoshiB, NelsonCR, RanishJA, BigginsS (2009) Quantitative proteomic analysis of purified yeast kinetochores identifies a PP1 regulatory subunit. Genes Dev 23 : 2887–2899.

24. HieterP, MannC, SnyderM, DavisRW (1985) Mitotic stability of yeast chromosomes: a colony color assay that measures nondisjunction and chromosome loss. Cell 40 : 381–392.

25. HillA, BloomK (1987) Genetic manipulation of centromere function. Mol Cell Biol 7 : 2397–2405.

26. WellsWA, MurrayAW (1996) Aberrantly segregating centromeres activate the spindle assembly checkpoint in budding yeast. J Cell Biol 133 : 75–84.

27. OrtizJ, StemmannO, RankS, LechnerJ (1999) A putative protein complex consisting of Ctf19, Mcm21, and Okp1 represents a missing link in the budding yeast kinetochore. Genes Dev 13 : 1140–1155.

28. PearsonCG, MaddoxPS, ZarzarTR, SalmonED, BloomK (2003) Yeast kinetochores do not stabilize Stu2p-dependent spindle microtubule dynamics. Mol Biol Cell 14 : 4181–4195.

29. GohPY, KilmartinJV (1993) NDC10: a gene involved in chromosome segregation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 121 : 503–512.

30. BakerRE, RogersK (2005) Genetic and genomic analysis of the AT-rich centromere DNA element II of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 171 : 1463–1475.

31. HuangCC, HajraS, GhoshSK, JayaramM (2011) Cse4 (CenH3) association with the Saccharomyces cerevisiae plasmid partitioning locus in its native and chromosomally integrated states: implications in centromere evolution. Mol Cell Biol 31 : 1030–1040.

32. KetelC, WangHS, McClellanM, BouchonvilleK, SelmeckiA, et al. (2009) Neocentromeres form efficiently at multiple possible loci in Candida albicans. PLoS Genet 5: e1000400 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000400.

33. KorenA, TsaiHJ, TiroshI, BurrackLS, BarkaiN, et al. (2010) Epigenetically-inherited centromere and neocentromere DNA replicates earliest in S-phase. PLoS Genet 6: e1001068 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001068.

34. AuerbachRK, EuskirchenG, RozowskyJ, Lamarre-VincentN, MoqtaderiZ, et al. (2009) Mapping accessible chromatin regions using Sono-Seq. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 : 14926–14931.

35. CollinsK, FuruyamaS, BigginsS (2004) Proteolysis contributes to the exclusive centromere localization of the yeast Cse4/CENP-A histone H3 variant. Curr Biol 14 : 1968–1972.

36. StolerS, RogersK, WeitzeS, MoreyL, Fitzgerald-HayesM, et al. (2007) Scm3, an essential Saccharomyces cerevisiae centromere protein required for G2/M progression and Cse4 localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 10571–10576.

37. da RosaJL, HolikJ, GreenEM, RandoOJ, KaufmanPD (2011) Overlapping regulation of CenH3 localization and histone H3 turnover by CAF-1 and HIR proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 187 : 9–19.

38. XiaoH, MizuguchiG, WisniewskiJ, HuangY, WeiD, et al. (2011) Nonhistone Scm3 binds to AT-rich DNA to organize atypical centromeric nucleosome of budding yeast. Mol Cell 43 : 369–380.

39. KrassovskyK, HenikoffJG, HenikoffS (2012) Tripartite organization of centromeric chromatin in budding yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 : 243–248.

40. KoshlandD, RutledgeL, Fitzgerald-HayesM, HartwellLH (1987) A genetic analysis of dicentric minichromosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 48 : 801–812.

41. MeraldiP, McAinshAD, RheinbayE, SorgerPK (2006) Phylogenetic and structural analysis of centromeric DNA and kinetochore proteins. Genome Biol 7: R23.

42. ScannellDR, ZillOA, RokasA, PayenC, DunhamMJ, et al. (2011) The Awesome Power of Yeast Evolutionary Genetics: New Genome Sequences and Strain Resources for the Saccharomyces sensu stricto Genus. G3 (Bethesda) 1 : 11–25.

43. MishraPK, AuWC, ChoyJS, KuichPH, BakerRE, et al. (2011) Misregulation of Scm3p/HJURP causes chromosome instability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and human cells. PLoS Genet 7: e1002303 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002303.

44. HeunP, ErhardtS, BlowerMD, WeissS, SkoraAD, et al. (2006) Mislocalization of the Drosophila centromere-specific histone CID promotes formation of functional ectopic kinetochores. Dev Cell 10 : 303–315.

45. MarshallOJ, ChuehAC, WongLH, ChooKH (2008) Neocentromeres: new insights into centromere structure, disease development, and karyotype evolution. Am J Hum Genet 82 : 261–282.

46. GuseA, CarrollCW, MoreeB, FullerCJ, StraightAF (2011) In vitro centromere and kinetochore assembly on defined chromatin templates. Nature 477 : 354–358.

47. MendiburoMJ, PadekenJ, FulopS, SchepersA, HeunP (2011) Drosophila CENH3 is sufficient for centromere formation. Science 334 : 686–690.

48. BarnhartMC, KuichPH, StellfoxME, WardJA, BassettEA, et al. (2011) HJURP is a CENP-A chromatin assembly factor sufficient to form a functional de novo kinetochore. J Cell Biol 194 : 229–243.

49. AlonsoA, HassonD, CheungF, WarburtonPE (2010) A paucity of heterochromatin at functional human neocentromeres. Epigenetics Chromatin 3 : 6.

50. VenturaM, WeiglS, CarboneL, CardoneMF, MisceoD, et al. (2004) Recurrent sites for new centromere seeding. Genome Res 14 : 1696–1703.

51. TeytelmanL, OzaydinB, ZillO, LefrancoisP, SnyderM, et al. (2009) Impact of chromatin structures on DNA processing for genomic analyses. PLoS ONE 4: e6700 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006700.

52. EdgarR, DomrachevM, LashA (2002) Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res 30 : 207–210.

53. EuskirchenGM, AuerbachRK, DavidovE, GianoulisTA, ZhongG, et al. (2011) Diverse roles and interactions of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex revealed using global approaches. PLoS Genet 7: e1002008 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002008.

54. GersteinMB, LuZJ, Van NostrandEL, ChengC, ArshinoffBI, et al. (2010) Integrative analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome by the modENCODE project. Science 330 : 1775–1787.

55. EuskirchenG, RozowskyJ, WeiC, LeeW, ZhangZ, et al. (2007) Mapping of transcription factor binding regions in mammalian cells by ChIP: comparison of array - and sequencing-based technologies. Genome Res 17 : 898–909.

56. ConsortiumEP (2011) A user's guide to the encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE). PLoS Biol 9: e1001046 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001046.

57. PfafflM (2001) A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29: e45.

58. ZhuLJ, GazinC, LawsonND, PagesH, LinSM, et al. (2010) ChIPpeakAnno: a Bioconductor package to annotate ChIP-seq and ChIP-chip data. BMC Bioinformatics 11 : 237.

59. KushnirovVV (2000) Rapid and reliable protein extraction from yeast. Yeast 16 : 857–860.

60. LeaDEC, C.A. (1949) The distribution of the numbers of mutants in bacterial populations. J Genetics 49 : 264–285.

61. CummingsL, RileyL, BlackL, SouvorovA, ResenchukS, et al. (2002) Genomic BLAST: custom-defined virtual databases for complete and unfinished genomes. FEMS Microbiol Lett 216 : 133–138.

62. Van HooserAA, OuspenskiII, GregsonHC, StarrDA, YenTJ, et al. (2001) Specification of kinetochore-forming chromatin by the histone H3 variant CENP-A. J Cell Sci 114 : 3529–3542.

63. DionMF, KaplanT, KimM, BuratowskiS, FriedmanN, et al. (2007) Dynamics of replication-independent histone turnover in budding yeast. Science 315 : 1405–1408.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Comparative Genome Structure, Secondary Metabolite, and Effector Coding Capacity across PathogensČlánek TATES: Efficient Multivariate Genotype-Phenotype Analysis for Genome-Wide Association StudiesČlánek Secondary Metabolism and Development Is Mediated by LlmF Control of VeA Subcellular Localization inČlánek Human Disease-Associated Genetic Variation Impacts Large Intergenic Non-Coding RNA ExpressionČlánek The Roles of Whole-Genome and Small-Scale Duplications in the Functional Specialization of GenesČlánek The Role of Autophagy in Genome Stability through Suppression of Abnormal Mitosis under Starvation

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2013 Číslo 1- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- A Model of High Sugar Diet-Induced Cardiomyopathy

- Comparative Genome Structure, Secondary Metabolite, and Effector Coding Capacity across Pathogens

- Emerging Function of Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated Protein (Fto)

- Positional Cloning Reveals Strain-Dependent Expression of to Alter Susceptibility to Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis in Mice

- Genetics of Ribosomal Proteins: “Curiouser and Curiouser”

- Transposable Elements Re-Wire and Fine-Tune the Transcriptome

- Function and Regulation of , a Gene Implicated in Autism and Human Evolution

- MAML1 Enhances the Transcriptional Activity of Runx2 and Plays a Role in Bone Development

- Predicting Mendelian Disease-Causing Non-Synonymous Single Nucleotide Variants in Exome Sequencing Studies

- A Systematic Mapping Approach of 16q12.2/ and BMI in More Than 20,000 African Americans Narrows in on the Underlying Functional Variation: Results from the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Study

- Transcription of the Major microRNA–Like Small RNAs Relies on RNA Polymerase III

- Histone H3K56 Acetylation, Rad52, and Non-DNA Repair Factors Control Double-Strand Break Repair Choice with the Sister Chromatid

- Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies a Novel Susceptibility Locus at 12q23.1 for Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Han Chinese

- Genetic Disruption of the Copulatory Plug in Mice Leads to Severely Reduced Fertility

- The [] Prion Exists as a Dynamic Cloud of Variants

- Adult Onset Global Loss of the Gene Alters Body Composition and Metabolism in the Mouse

- Fis Protein Insulates the Gene from Uncontrolled Transcription

- The Meiotic Nuclear Lamina Regulates Chromosome Dynamics and Promotes Efficient Homologous Recombination in the Mouse

- Genome-Wide Haplotype Analysis of Expression Quantitative Trait Loci in Monocytes

- TATES: Efficient Multivariate Genotype-Phenotype Analysis for Genome-Wide Association Studies

- Structural Basis of a Histone H3 Lysine 4 Demethylase Required for Stem Elongation in Rice

- The Ecm11-Gmc2 Complex Promotes Synaptonemal Complex Formation through Assembly of Transverse Filaments in Budding Yeast

- MCM8 Is Required for a Pathway of Meiotic Double-Strand Break Repair Independent of DMC1 in

- Comparative Genomic Analysis of the Endosymbionts of Herbivorous Insects Reveals Eco-Environmental Adaptations: Biotechnology Applications

- Integration of Nodal and BMP Signals in the Heart Requires FoxH1 to Create Left–Right Differences in Cell Migration Rates That Direct Cardiac Asymmetry

- Pharmacodynamics, Population Dynamics, and the Evolution of Persistence in

- A Hybrid Likelihood Model for Sequence-Based Disease Association Studies

- Aberration in DNA Methylation in B-Cell Lymphomas Has a Complex Origin and Increases with Disease Severity

- Multiple Opposing Constraints Govern Chromosome Interactions during Meiosis

- Transcriptional Dynamics Elicited by a Short Pulse of Notch Activation Involves Feed-Forward Regulation by Genes

- Dynamic Large-Scale Chromosomal Rearrangements Fuel Rapid Adaptation in Yeast Populations

- Heterologous Gln/Asn-Rich Proteins Impede the Propagation of Yeast Prions by Altering Chaperone Availability

- Gene Copy-Number Polymorphism Caused by Retrotransposition in Humans

- An Incompatibility between a Mitochondrial tRNA and Its Nuclear-Encoded tRNA Synthetase Compromises Development and Fitness in

- Secondary Metabolism and Development Is Mediated by LlmF Control of VeA Subcellular Localization in

- Single-Stranded Annealing Induced by Re-Initiation of Replication Origins Provides a Novel and Efficient Mechanism for Generating Copy Number Expansion via Non-Allelic Homologous Recombination

- Tbx2 Controls Lung Growth by Direct Repression of the Cell Cycle Inhibitor Genes and

- Suv4-20h Histone Methyltransferases Promote Neuroectodermal Differentiation by Silencing the Pluripotency-Associated Oct-25 Gene

- A Conserved Helicase Processivity Factor Is Needed for Conjugation and Replication of an Integrative and Conjugative Element

- Telomerase-Null Survivor Screening Identifies Novel Telomere Recombination Regulators

- Genome-Wide Analysis Reveals Selection for Important Traits in Domestic Horse Breeds

- Coordinated Degradation of Replisome Components Ensures Genome Stability upon Replication Stress in the Absence of the Replication Fork Protection Complex

- Nkx6.1 Controls a Gene Regulatory Network Required for Establishing and Maintaining Pancreatic Beta Cell Identity

- HIF- and Non-HIF-Regulated Hypoxic Responses Require the Estrogen-Related Receptor in

- Delineating a Conserved Genetic Cassette Promoting Outgrowth of Body Appendages

- The Telomere Capping Complex CST Has an Unusual Stoichiometry, Makes Multipartite Interaction with G-Tails, and Unfolds Higher-Order G-Tail Structures

- Comprehensive Methylome Characterization of and at Single-Base Resolution

- Loci Associated with -Glycosylation of Human Immunoglobulin G Show Pleiotropy with Autoimmune Diseases and Haematological Cancers

- Switchgrass Genomic Diversity, Ploidy, and Evolution: Novel Insights from a Network-Based SNP Discovery Protocol

- Centromere-Like Regions in the Budding Yeast Genome

- Sequencing of Loci from the Elephant Shark Reveals a Family of Genes in Vertebrate Genomes, Forged by Ancient Duplications and Divergences

- Mendelian and Non-Mendelian Regulation of Gene Expression in Maize

- Mutational Spectrum Drives the Rise of Mutator Bacteria

- Human Disease-Associated Genetic Variation Impacts Large Intergenic Non-Coding RNA Expression

- The Roles of Whole-Genome and Small-Scale Duplications in the Functional Specialization of Genes

- Sex-Specific Signaling in the Blood–Brain Barrier Is Required for Male Courtship in

- A Newly Uncovered Group of Distantly Related Lysine Methyltransferases Preferentially Interact with Molecular Chaperones to Regulate Their Activity

- Is Required for Leptin-Mediated Depolarization of POMC Neurons in the Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus in Mice

- Unlocking the Bottleneck in Forward Genetics Using Whole-Genome Sequencing and Identity by Descent to Isolate Causative Mutations

- The Role of Autophagy in Genome Stability through Suppression of Abnormal Mitosis under Starvation

- MTERF3 Regulates Mitochondrial Ribosome Biogenesis in Invertebrates and Mammals

- Downregulation and Altered Splicing by in a Mouse Model of Facioscapulohumeral Muscular Dystrophy (FSHD)

- NBR1-Mediated Selective Autophagy Targets Insoluble Ubiquitinated Protein Aggregates in Plant Stress Responses

- Retroactive Maintains Cuticle Integrity by Promoting the Trafficking of Knickkopf into the Procuticle of

- Phenome-Wide Association Study (PheWAS) for Detection of Pleiotropy within the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Network

- Genetic and Functional Modularity of Activities in the Specification of Limb-Innervating Motor Neurons

- A Population Genetic Model for the Maintenance of R2 Retrotransposons in rRNA Gene Loci

- A Quartet of PIF bHLH Factors Provides a Transcriptionally Centered Signaling Hub That Regulates Seedling Morphogenesis through Differential Expression-Patterning of Shared Target Genes in

- A Genome-Wide Integrative Genomic Study Localizes Genetic Factors Influencing Antibodies against Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 1 (EBNA-1)

- Mutation of the Diamond-Blackfan Anemia Gene in Mouse Results in Morphological and Neuroanatomical Phenotypes

- Life, the Universe, and Everything: An Interview with David Haussler

- Alternative Oxidase Expression in the Mouse Enables Bypassing Cytochrome Oxidase Blockade and Limits Mitochondrial ROS Overproduction

- An Evolutionarily Conserved Synthetic Lethal Interaction Network Identifies FEN1 as a Broad-Spectrum Target for Anticancer Therapeutic Development

- The Flowering Repressor Underlies a Novel QTL Interacting with the Genetic Background

- Telomerase Is Required for Zebrafish Lifespan

- and Diversified Expression of the Gene Family Bolster the Floral Stem Cell Network

- Susceptibility Loci Associated with Specific and Shared Subtypes of Lymphoid Malignancies

- An Insertion in 5′ Flanking Region of Causes Blue Eggshell in the Chicken

- Increased Maternal Genome Dosage Bypasses the Requirement of the FIS Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 in Arabidopsis Seed Development

- WNK1/HSN2 Mutation in Human Peripheral Neuropathy Deregulates Expression and Posterior Lateral Line Development in Zebrafish ()