-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

The Spore Differentiation Pathway in the Enteric Pathogen

Endosporulation is an ancient bacterial developmental program that culminates with the differentiation of a highly resistant endospore. In the model organism Bacillus subtilis, gene expression in the forespore and in the mother cell, the two cells that participate in endospore development, is governed by cell type-specific RNA polymerase sigma subunits. σF in the forespore, and σE in the mother cell control early stages of development and are replaced, at later stages, by σG and σK, respectively. Starting with σF, the activation of the sigma factors is sequential, requires the preceding factor, and involves cell-cell signaling pathways that operate at key morphological stages. Here, we have studied the function and regulation of the sporulation sigma factors in the intestinal pathogen Clostridium difficile, an obligate anaerobe in which the endospores are central to the infectious cycle. The morphological characterization of mutants for the sporulation sigma factors, in parallel with use of a fluorescence reporter for single cell analysis of gene expression, unraveled important deviations from the B. subtilis paradigm. While the main periods of activity of the sigma factors are conserved, we show that the activity of σE is partially independent of σF, that σG activity is not dependent on σE, and that the activity of σK does not require σG. We also show that σK is not strictly required for heat resistant spore formation. In all, our results indicate reduced temporal segregation between the activities of the early and late sigma factors, and reduced requirement for the σF-to-σE, σE-to-σG, and σG-to-σK cell-cell signaling pathways. Nevertheless, our results support the view that the top level of the endosporulation network is conserved in evolution, with the sigma factors acting as the key regulators of the pathway, established some 2.5 billion years ago upon its emergence at the base of the Firmicutes Phylum.

Published in the journal: The Spore Differentiation Pathway in the Enteric Pathogen. PLoS Genet 9(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003782

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003782Summary

Endosporulation is an ancient bacterial developmental program that culminates with the differentiation of a highly resistant endospore. In the model organism Bacillus subtilis, gene expression in the forespore and in the mother cell, the two cells that participate in endospore development, is governed by cell type-specific RNA polymerase sigma subunits. σF in the forespore, and σE in the mother cell control early stages of development and are replaced, at later stages, by σG and σK, respectively. Starting with σF, the activation of the sigma factors is sequential, requires the preceding factor, and involves cell-cell signaling pathways that operate at key morphological stages. Here, we have studied the function and regulation of the sporulation sigma factors in the intestinal pathogen Clostridium difficile, an obligate anaerobe in which the endospores are central to the infectious cycle. The morphological characterization of mutants for the sporulation sigma factors, in parallel with use of a fluorescence reporter for single cell analysis of gene expression, unraveled important deviations from the B. subtilis paradigm. While the main periods of activity of the sigma factors are conserved, we show that the activity of σE is partially independent of σF, that σG activity is not dependent on σE, and that the activity of σK does not require σG. We also show that σK is not strictly required for heat resistant spore formation. In all, our results indicate reduced temporal segregation between the activities of the early and late sigma factors, and reduced requirement for the σF-to-σE, σE-to-σG, and σG-to-σK cell-cell signaling pathways. Nevertheless, our results support the view that the top level of the endosporulation network is conserved in evolution, with the sigma factors acting as the key regulators of the pathway, established some 2.5 billion years ago upon its emergence at the base of the Firmicutes Phylum.

Introduction

Endosporulation is an ancient bacterial cell differentiation program that culminates with the formation of a highly resistant dormant cell, the endospore. Bacterial endospores (hereinafter designated spores for simplicity), as those formed by species of the well-known Bacillus and Clostridium genera, but also by many other groups within the Firmicutes phylum, resist to extremes of physical and chemical parameters that would rapidly destroy the vegetative cells, and are the most resistant cellular structure known [1], [2]. Their resilience allows them to accumulate in highly diverse environmental settings, often for extremely long periods of time. The range of environments occupied by sporeformers, include niches within metazoan hosts, in particular the gastro-intestinal tract (GIT) (e.g. [3]–[5]). B. subtilis, for example, a non-pathogenic sporeformer, can go through several cycles of growth, sporulation and germination in the GIT [5]. For pathogenic sporeformers, spores are often the infectious vehicle as in the inhalational or gastric forms of anthrax, the potentially lethal disease caused by B. anthracis [6]. Also, it is a protein present at the spore surface that mediates spore internalization by macrophages, and spore dissemination to local lymph nodes, which are central to pathogenesis [6], [7]. Infection by the intestinal human and animal pathogen C. difficile, an obligate anaerobe, and the subject of the present investigation, often also starts with the ingestion of spores [8], [9]. C. difficile is the causative agent of an intestinal disease whose symptoms can range from mild diarrhea to severe, potentially lethal inflammatory lesions such as pseudomembraneous colitis, toxic megacolon or bowel perforation [8], [10]. Ingested spores of this organism germinate in the colon, to establish a population of vegetative cells that will produce two potent cytotoxins and more spores [8], [10]–[12]. Infection develops because C. difficile can colonize the gut if the normal intestinal microbiota is disturbed [8] [9]. Toxinogenesis is responsible for most of the disease symptoms, whereas the spores, which can remain latent in the gut, are both a persistence and transmission factor [8], [10]–[13]. While an asporogeneous mutant of C. difficile can cause intestinal disease, it is unable to persist within and transmit between host organism [13]. The spore thus has a central role in persistence of the organism in the environment, infection, recurrence and transmission of the disease. Recent years have seen the emergence of strains, so called hypervirulent, linked to increased incidence of severe disease, higher relapse rates and mortality, and C. difficile is now both a main nosocomial pathogen associated with antibiotic therapy as well as a major concern in the community [8], [9], [14].

The basic spore plan is conserved [15]–[17]. The genome is deposited in a central compartment delimited by a lipid bilayer with a layer of peptidoglycan (PG) apposed to its external leaflet. This layer of PG, known as the germ cell wall, will serve as the wall of the outgrowing cell that forms when the spore completes germination. The germ cell wall is encased in a thick layer of a modified form of PG, the cortex, essential for the acquisition and maintenance of heat resistance [15], [16]. The cortex is wrapped by a multiprotein coat, which protects it from the action of PG-breaking enzymes produced by host organisms or predators [15], [16]. In some species, including the pathogens B. anthracis, B. cereus and C. difficile, the coat is further enclosed within a structure known as the exosporium. The coat and the exosporium, when present, mediate the immediate interactions of the spore with the environment, including the interaction with small molecules that trigger germination [7], [15], [18]–[20].

The process of spore differentiation has been extensively studied in the model organism B. subtilis [21] [22]. Rod-shaped vegetative cells, growing by binary fission, will switch to an asymmetric (polar) division when facing severe nutritional stress. Polar division yields a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore, the future spore. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore. This process, akin to phagocytosis and a hallmark of endosporulation, isolates the forespore from the surrounding medium, and releases it as a cell, surrounded by a double membrane, within the mother cell cytoplasm [21], [22]. With the exception of the germ cell wall, which is formed from the forespore, the assembly of the main spore protective structures is mostly a function of the mother cell [15], [16]. At the end of the process, and following a period of spore maturation, the mother cell undergoes autolysis, to release the finished spore. For the organisms that have been studied to date, mostly by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), this basic sequence of morphological events appears conserved [15], [21].

The developmental regulatory network of sporulation shows a hierarchical organization and functional logic [17]. A master regulatory protein, Spo0A, activated by phosphorylation, governs entry into sporulation, including the switch to asymmetric division [21], [23]. Gene expression in the forespore and mother cell is controlled by 4 cell type-specific sigma factors, which are sequentially activated, alternating between the two cells. σF and σE control the early stages of development in the forespore and the mother cell, respectively, and are replaced by σG and σK when engulfment of the forespore is completed [21]–[23]. Activation of the sporulation sigma factors coincides with the completion of key morphological intermediates in the process, at which stages cell-cell signaling events further allow the alignment of the forespore and mother cell programs of gene expression. The result is the coordinated deployment of the forespore and mother cell lines of gene expression, in close register with the course of cellular morphogenesis [21]–[23]. Additional regulatory proteins, working with the sigma factors, generate feed forward loops (FFLs) that create waves of gene expression, minimizing transcriptional noise and impelling morphogenesis forward [17]. A large number of genes of B. subtilis, distributed in the four cell type-specific regulons, participate in spore morphogenesis [24]–[27]. The key regulatory factors, Spo0A and the sporulation sigma factors, which define the highest level in the functional and evolutionary hierarchy of the sporulation network, are conserved in sporeformers. The FFLs show an intermediary level of conservation, with the “structural” genes, with the lower level of conservation, at the lowest level in the hierarchy [17], [24]–[27]. The conservation of the sporulation sigma factors has suggested that their role and sequential activation is also maintained across species [17]. However, recent studies have revealed differences in the roles and time of activity of the sigma factors during spore morphogenesis in several Clostridial species [28]–[35]. For instance, σF and σE are active prior to asymmetric division in C. acetobutylicum and C. perfringens [30], [31], [33], [35]. Also, σK, which in B. subtilis controls late stages of morphogenesis in the mother cell, is active in pre-divisional cells of C. perfringens and C. botulinum [29], [34]. Collectively, and relative to the aerobic Bacilli, the Clostridia represent an older group within the Firmicutes phylum, at the base of which endosporulation has emerged some 2.5 billion years ago, before the initial rise in oxygen levels [24]–[28], [36].

Despite the importance of C. difficile for human health and activities, and the central role of sporulation in the infection cycle, a cytological and molecular description of sporulation has been lacking. Here, we have combined cytological and genetics methodologies to define the sequence of sporulation events in C. difficile and the function of the cell type-specific sigma factors. In addition, by using a fluorescent reporter for studies of gene expression at the single cell level, we were able to correlate the expression and activity of the sporulation-specific sigma factors with the course of morphogenesis. A key observation is that during C. difficile sporulation the forespore and mother cell programs of gene expression are less tightly coupled. Our study also provides a platform for additional studies of the regulatory network and for integrating the expression and function of the effector genes, many of which will be species-specific, and possibly related to host colonization and transmission.

Results

Sporulation in sporulation medium (SM)

Earlier studies using TEM have suggested that the main stages of sporulation are conserved amongst Bacillus and Clostridial species [37]. Here, we examined sporulation of C. difficile using phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy with the goal of establishing a platform for both the phenotypic analysis of mutants blocked in the process and for the analysis of developmental gene expression in relation to the course of morphogenesis. This approach requires the individual scoring of a relative large number of cells. However, under culturing conditions widely used for C. difficile sporulation, as in BHI medium, supplemented or not with cysteine and yeast extract (BHIS), the process is highly heterogeneous, or asynchronous [11], [14], [38], [39], reviewed by [40]). High titers of spores have been reported following 48 h incubation of liquid cultures in the Sporulation Medium (or SM) described by Wilson and co-authors [41], but how the spore titer developed over time was not reported. More recently, SM was used, with some modifications to the original formulation, for high yield spore production on agar plates [42]. We determined the spore titer during growth of the wild type strain 630Δerm in liquid SM cultures. As shown in Figure 1A, no heat resistant spores could be detected at the time of inoculation, or during the first 10 hours of growth. Heat resistant spores, 3.7×102 spores/ml, were first detected at hour 12, a titer that increased to 2.4×105 at hour 24 (about 14 hours after entry into the stationary phase of growth), the later number corresponding to a percentage of sporulation of 0.3% (Figure 1A and Table S1). From hour 24 onwards, the spore titer increased slowly, to reach 4.7×106 spores/ml 72 hours following inoculation, corresponding to 43.8% sporulation (Figure 1A). Importantly, the percentage of sporulation in SM medium was higher than in BHI or BHIS for all the time points tested (Figure S1). In particular, the titer of spores in SM was two orders of magnitude higher than in BHIS, when measured 24 hours following inoculation (Figure S1). For our studies of spore morphogenesis and cell type-specific gene expression, SM was adopted.

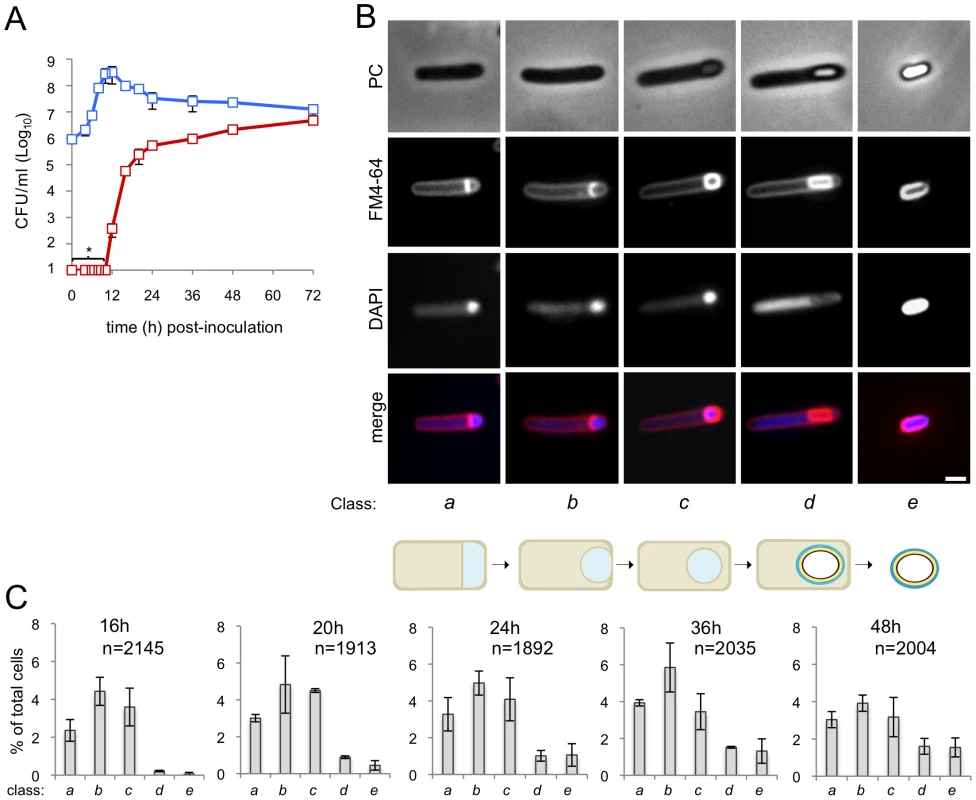

Fig. 1. Sporulation in C. difficile 630Δerm.

(A) The spore (red symbols) and total cell titer (blue symbols) was measured for a culture of strain 630Δerm at the indicated times post-inoculation in SM. The data represent the average ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments. No heat resistant CFUs were detected for an undiluted 100 µl culture sample (CFU/ml: ≤101). (B) Samples of an SM broth culture of strain 630Δerm were collected 24 h after inoculation, stained with DAPI and FM4-64 and examined by phase contrast (PC) and fluorescence microscopy. The panel illustrates the stages in the sporulation pathway, according to the classes defined in the text and represented schematically at the bottom of the panel (see the Results section). Scale bar, 1 µm. (C) Quantification of the percentage of cells in the morphological classes represented in (B) (as defined in the text), relative to the total viable cell population, for strain 630Δerm at the indicated times following inoculation in SM broth. The data represent the average ± SD of three independent experiments. The total number of cells scored (n) is indicated in each panel. Stages of sporulation

We then wanted to monitor progress through the morphological stages of sporulation by phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy. In a first experiment, a sample from cultures of the wild type strain 630Δerm was collected 24 hours after inoculation into SM, for microscopic examination following staining with the lipophilic membrane dye FM4-64 and with the DNA marker DAPI. Cells representative of several distinctive morphological classes are shown on Figure 1B (top). Cells with straight asymmetrically positioned septa (class a) and cells with curved spore membranes (i.e., at intermediate stages in the engulfment sequence; class b), both showing intense staining of the forespore DNA, were readily seen (Figure 1B). Another class comprised cells showing strong uniform FM4-64 staining around the entire contour of the forespore (Figure 1B). The staining pattern suggests that the forespore is entirely surrounded by a double membrane, and therefore that the engulfment sequence was finalized. Those cells in which the forespore shows a continuous, strong FM4-64 signal, but has not yet developed partial or full refractility are considered to have just completed the engulfment process, and define class c. A strong, condensed DAPI signal in the forespore was also seen for this class (Figure 1B). Intense, uniform staining of the forespore by FM4-64 was maintained in cells carrying phase grey (partially refractile) or phase bright spores, defining class d (Figure 1B). DAPI staining of the forespore DNA was variable for both cells with phase grey or phase bright spores in this class (data not shown). Free spores, at least some of which could be stained with DAPI, define a last morphological class (class e) (Figure 1B). The stages of sporulation discerned conform well to the sequence established for B. subtilis (Figure 1B, bottom) [15], [21], [37]. Staining of the developing spore by FM4-64 following engulfment completion contrasts with the situation in B. subtilis, in which the lipophilic dye does not label engulfed forespores [43] (see also Figure S2A). However, in other organisms, FM4-64 stains the engulfed forespore [3] (see also Text S1). Also, FM4-64 does not stain free spores of B. subtilis (which do not have and exosporium) or B. cereus (which are surrounded by an exosporium) (Figure S2B), but stains C. difficile spores (which also possess an exosporium) (Figure S3). Spore staining by FM4-64 may thus be more related to the composition of the surface layers, rather than to the presence of a specific structure. We note that affinity of FM dyes to the spore coats has been reported [3] (see also Text S1).

Under our culturing conditions, cells belonging to each of the five morphological classes considered (a to e) were seen at all the time points examined (Figure 1C). This suggests that sporulation is heterogeneous, or asynchronous, in agreement with other results [43], with cells entering the sporulation pathway throughout the duration of the experiment. Surprisingly, the representation of cells at intermediate stages in development (classes a to c) decreased from hour 36 to hour 48, without a corresponding rise in later morphological classes (class d, phase grey/bright spores and class e, free spores) (Figure 1C). However, Live/Dead staining evidenced cell lysis, including of cells at intermediate stages of sporulation (classes a to c), from hour 36 of growth onwards (data not shown). As assessed by Live/Dead staining and fluorescence microscopy, lysis of sporulating cells was only marginal at hour 24 of growth (data not shown). Therefore, in subsequent experiments, sporulating cells were scored 24 hours following inoculation. At hour 24, the total number of sporulating cells (i.e., the sum of classes a to e in Figure 1C) represents about 15% of the total cell population.

Disruption of the genes for the sporulation sigma factors

The genes for the four cell type-specific RNA polymerase sigma factors known to control gene expression during spore differentiation in B. subtilis are conserved in sporeformers [24]–[27]. Moreover, their operon structure and genomic context is also maintained (Figure S4A). To investigate whether the function of the σF, σE, σG and σK factors is conserved, each of the corresponding genes was disrupted (Figure S4). For this purpose, type II introns were targeted to each of the sig genes, using the ClosTron system [44]. As shown in Figure S4A, re-targeting of the intron resulted in insertion after codon 153 of the sigF gene, codon 151 of sigE, codon 182 of sigG, and codon 34 of the 5′-end of the split sigK gene, interrupted by the skinCd element. Correct insertion of the intron was verified, in all cases, by PCR, and Southern blot analysis showed the presence of a single intron insertion in the genome of the different mutants (Figure S4B through E). The sig mutants, along with the parental 630Δerm strain, were induced to sporulate in SM, and the titer of heat resistant spores assessed after 24, 48, and 72 hours of growth. For the wild type strain 630Δerm, the titer of spores was of 3×105 spores/ml at hour 24, 2×106 spores/ml at hour 48, and of 1×107 spores/ml at hour 72 (Table 1). In contrast, no heat resistant spores were found, at any time point tested, for the sigF (AHCD533), sigE (AHCD532), or sigG (AHCD534) mutants. However, a titer of 103 heat resistant spores/ml of culture was found for the sigK mutant AHCD535 at hour 72 (Table 1). For complementation studies, we generated multicopy alleles of the sig genes, based on replicative plasmid pMTL84121 [45], expressed from their native promoters (the extent of the promoter fragments is shown in Figure S4A). Note that for complementation of the sigK mutation the two halves of the gene, together with a short skinCd element composed only of the putative recombinase gene (spoIVCA, or CD12310) was used (see below for a more detailed description on the complementation of the sigK mutation). When measured at hour 72 of growth in SM, the heat resistant spore titer was of 1.7×106 spores/ml for the wild type strain 630Δerm carrying the empty vector pMTL84121. Derivatives of pMTL84121 carrying the sigF, sigE, sigG or sigK genes (the later plasmid, pFT38, with the short skinCd allele) restored spore formation to the sig mutants, as assessed by microscopy (Figure 2B). The same plasmids largely restored heat resistant spore formation to the sig mutants (1.6×104, 8.3×105, 3.9×105, 4.8×105 spores/ml for the sigF, sigE, sigG, and sigK mutants, respectively, also measured at hour 72 of growth in SM).

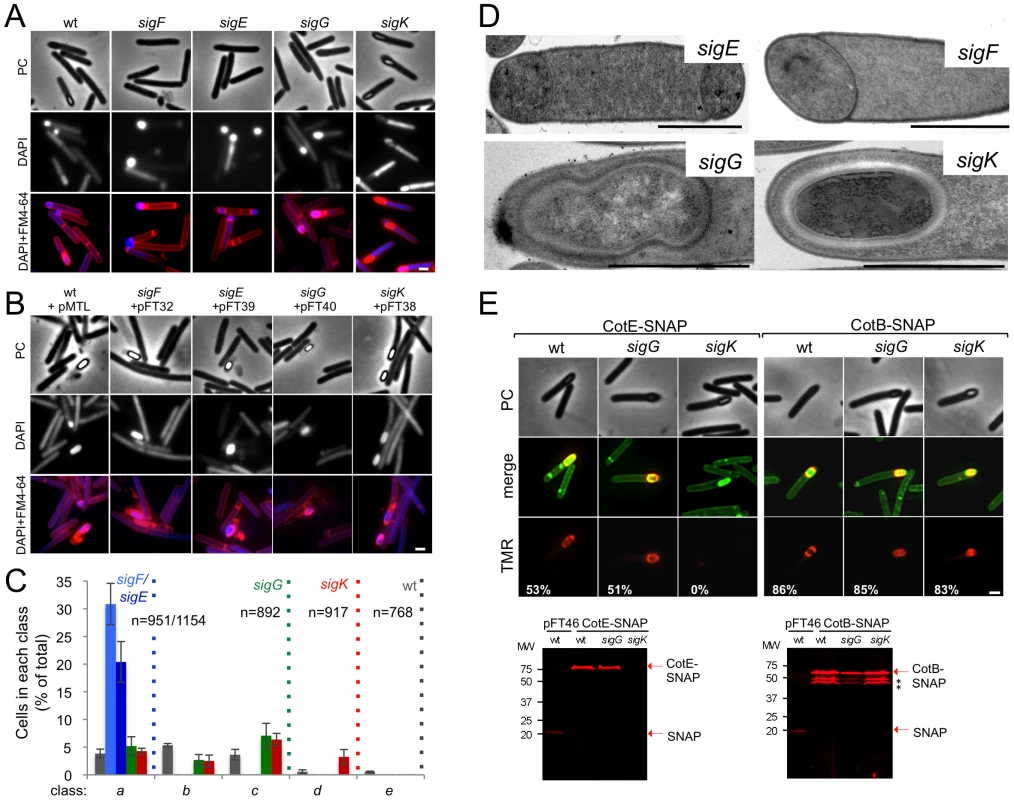

Fig. 2. The sporulation pathway in C. difficile 630Δerm, and the role of sigF, sigE, sigG and sigK.

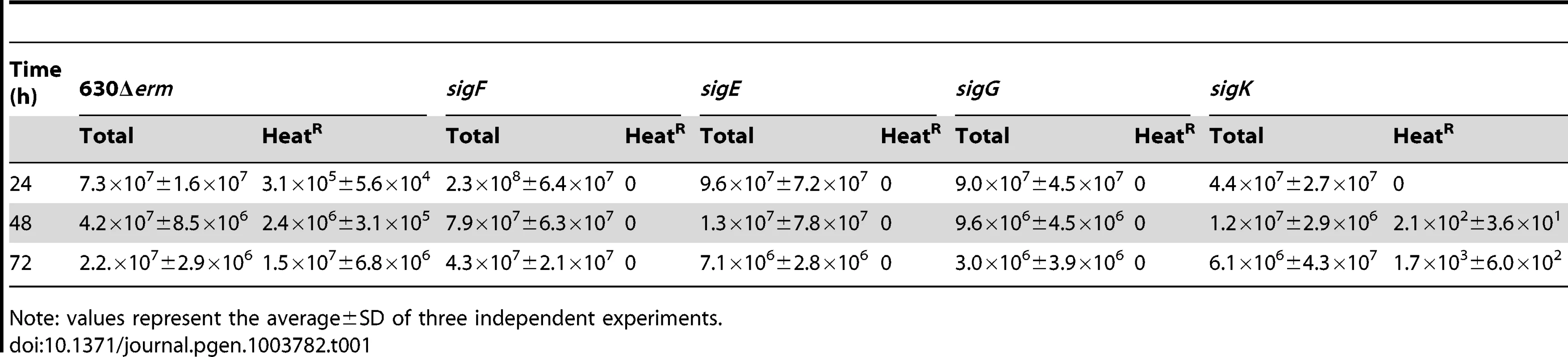

Phase contrast (PC) and fluorescence microscopy analysis of spore morphogenesis in the following strains: (A) 630Δerm (wild type, wt) and the congenic sigF, sigE, sigG and sigK mutants; (B) the sig mutants bearing the indicated plasmids or the wt strain carrying the empty vector pMTL84121. Cells were collected 24 (A) or 48 h (B) after inoculation in SM broth, and stained with DAPI and FM4-64, prior to microscopic examination. (C) Quantification of the cells in each morphological class, as defined in Figure 1, in the experiment documented in panel A, for the wt strain and the sig mutants. The data represent the average ± SD of three independent experiments. The total number of cells analysed (n) is indicated for each strain. (D) TEM images of sigF, sigE, sigG and sigK mutant cells. The Images are representative of the most common morphological phenotype observed for each mutant. (E) Fluorescence microscopy of 630Δerm (wt) and sigG and sigK strains carrying CotE- and CotB-SNAP fusions. Cells were collected 24 h after inoculation in SM medium and labeled with the SNAP substrate TMR-Star (red channel) and the membrane dye MTG (green channel), with which a membrane-staining pattern similar to FM4-64 was obtained. The numbers on the bottom panel represent the percentage of cells which have completed the engulfment process that show localization of the protein fusions around the forespore. Data shown are from one representative experiment in which 80–100 cells were analysed for each strain. Scale bar in panels (A, B, D, E), 1 µm. Total cell extracts were prepared from 24 h SM cultures of derivatives of the 630Δerm, sigG and sigK strains producing the CotE- (left) and CotB-SNAP (right) fusions, immediately after labeling with TMR-Star. Proteins (30 µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and the gel scanned using a fluorimager. Production of the SNAP protein in the background of 630Δerm strain from the Ptet promoter (Ptet-SNAPCd, in pFT46; see Text S1), was used as a control. The position of the SNAP or SNAP fusion proteins is indicated by arrowheads. Asteriks indicate possible degradation products. Tab. 1. Total and heat resistant (HeatR) cell counts (CFU/ml) for the wild type strain (630Δerm) and congenic sigF, sigE, sigG and sigK mutants in SM.

Note: values represent the average±SD of three independent experiments. Morphological characterization of the sigF, sigE, and sigG mutants

To establish the morphological phenotype of the various mutants we used phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy of samples collected from SM cultures at hour 24, labeled with DAPI and FM4-64 (Figure 2). These studies revealed that the sigF and sigE mutants were blocked at the asymmetric division stage (Figure 2A and C). As previously found for B. subtilis [37], [46], [47] both mutants formed abortive disporic forms, and occasionally multiple closely located polar septa (Figure 2A). In addition, for the sigF mutant, small round cells were found, probably resulting from detachment of the forespore (Figure 2A). In both mutants, the DNA stained strongly in the forespore(s) and gave a diffuse signal throughout the mother cell (Figure 2A). TEM analysis confirmed the block at the asymmetric division stage for the two mutants (Figure 2D).

Cells of the sigG mutant completed the engulfment sequence, but did not proceed further in morphogenesis (Figure 2A and C). As for class c in the wild type (Figure 1B, and text above), the forespores in the sigG mutant stained strongly with FM4-64 (Figure 2A). TEM of sporulating cells of the sigG mutant confirmed engulfment completion, but also revealed deposition of electrodense material around the forespore protoplast (Figure 2D). This deposit could represent coat material. By comparison, no accumulation of electrodense coat-like material is seen by TEM around the engulfed forespore of a B. subtilis sigG mutant [48]. In this organism, coat assembly as discernible by TEM, is a late event that requires activation of σK in the mother cell [15], [16], [37]. Importantly, activation of σK is triggered by σG, and coincides with engulfment completion [49], [50]. Therefore, the possible accumulation of coat material in the sigG mutant could imply that in C. difficile, σK is active independently of σG. We therefore wanted to test whether coat material was deposited around the forespore in the C. difficile sigG mutant. In B. subtilis, studies of protein localization have relied mainly on the use of translational fusions to the gfp gene, or its variants (e.g., [51]). However, an obstacle to the use of gfp or its derivatives in the anaerobe C. difficile, is that formation of the GFP fluorophore involves an oxidation reaction [52]. For this reason, we turned to the SNAP-tag reporter, which reacts with fluorescent derivatives of benzyl purine or pyrimidine substrates, and has been used in anaerobic bacteria [53], [54]. We designed a variant of the SNAP26b gene, termed SNAPCd, codon-usage optimized for expression in C. difficile (see Materials and Methods; see also Text S1), and used it to construct C-terminal fusions of the SNAP-tag to spore coat proteins CotE and CotB [55], [56] in plasmid pFT58 (Figure S5B and C). The fusions were introduced, in a replicative plasmid, in strain 630Δerm and the sigG and sigK mutants, and samples from SM cultures at hour 24 were labeled with the cell-permeable fluorescent substrate TMR-Star (see Materials and Methods). Using fluorescence microscopy and fluorimaging of SDS-PAGE-resolved whole cell extracts, no accumulation of CotE-SNAP was detected in cells of a sigK mutant, suggesting that the cotE gene is under the control of σK (Figure 2E; see also below). CotB-SNAP, however, accumulated in cells of a sigK mutant (Figure 2E), but not in cells of a sigE mutant (data not shown), suggesting that expression of cotB is under the control of σE. Both CotE-SNAP and CotB-SNAP localized around the forespore in both wild type and in sigG cells (Figure 2E). SDS-PAGE and fluorimaging suggested instability of CotB-SNAP for which several possible proteolytic fragments were detected, all of which larger that the SNAP domain (Figure 2E). That no release of a labeled SNAP domain was detected for either protein implies that the localized fluorescence signal is largely due to the fusion proteins. Thus, both early (CotB) and late (CotE) coat proteins are assembled around the forespore in cells of a sigG mutant. In all, the results suggest that σK is active independently of σG, and thus, that the later regulatory protein is not a strict requirement for deposition of at least some coat in C. difficile.

Functional analysis of the sigK gene

Phase contrast microscopy revealed the presence of some phase bright or partially phase bright spores in SM cultures of the sigK mutant, although free spores were only rarely seen (Figure 2A). The ellipsoidal spores were often positioned slightly tilted relative to the longitudinal axis of the mother cell (Figure 2 and 3). The appearance of phase bright spores normally correlates with synthesis of the spore cortex PG, and the development of spore heat resistance [37], [57], in line with the finding that the sigK mutant formed heat resistant spores (above). TEM revealed the presence of a cortex layer in cells of the sigK mutant, supporting the inferences drawn on the basis of the phase contrast microscopy and heat resistance assays (Figure 2A to E). The number of phase bright or phase grey spores by phase contrast microscopy, was 3.2% of the total number of cells scored at hour 24 of growth in liquid SM (Figure 2C). This is higher than the percentage of sporulation, 0.03%, measured by heat resistance (Table 1). Because full heat resistance requires synthesis of most of the cortex structure, this observation suggests that a large number of the spores formed have an incomplete or dysfunctional cortex. However, we cannot discard the possibility that spores of the mutant are deficient in germination. In any event, unlike in B. subtilis, where a sigK mutant is unable to form the spore cortex [37], [57], σK is not obligatory for the biogenesis of this structure in C. difficile. In contrast, the TEM analysis did not reveal deposition of coat material around the cortex in cells of the sigK mutant (Figure 2D). Although coat assembly most likely starts early, under the control of σE ([15], [16], [42]; above) the TEM data, together with the data on assembly of CotE (Figure 2E), suggest that the late stages in the assembly of the coats are under σK control. That free spores were only rarely seen for the sigK mutant, prompted us to test whether σK could have a role in mother cell lysis, using a Live/Dead stain and fluorescence microscopy. In the wild type strain 630Δerm, development of refractility coincided with loss of viability of the mother cell (strong staining with propidium iodide) and strong staining of the developing spore with the Syto 9 dye (Figure 3A), [58]. In contrast, the mother cell remained viable in the sigK mutant (strong staining with Syto 9) (Figure 3A and B), and the spores stained only weakly with the Syto 9 dye.

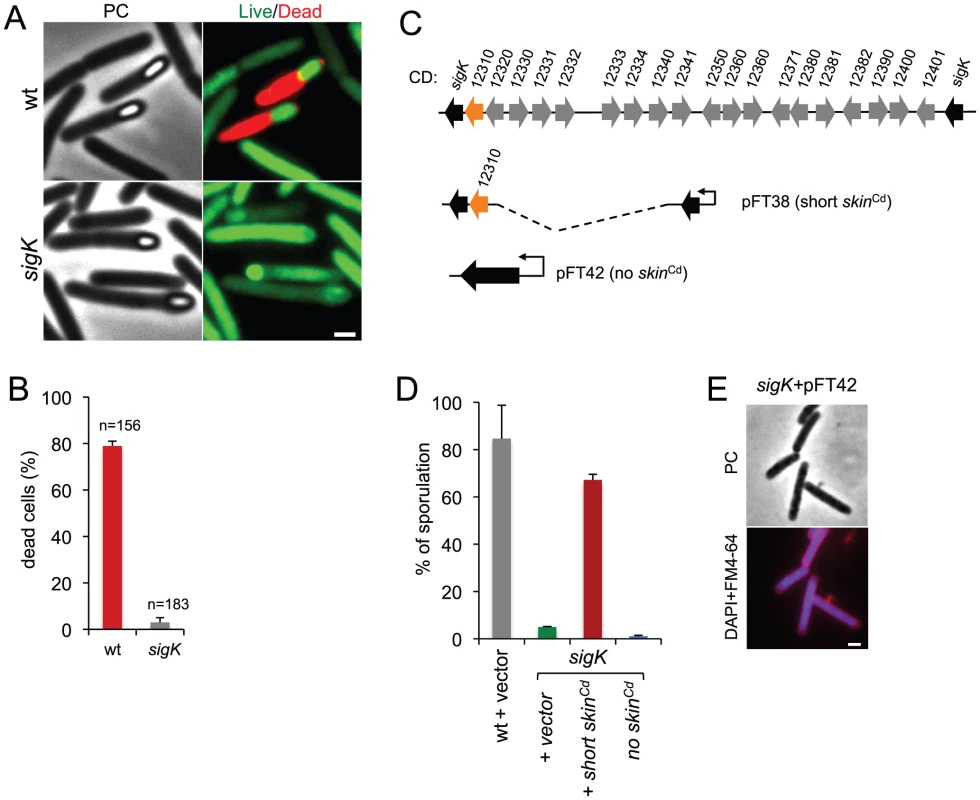

Fig. 3. Functional analysis of the sigK gene.

(A) Live/dead assay for the wild type (630Δerm) and the sigK mutant. Shown are phase contrast and the merge between syto 9- (live cells stain; green) and propidium iodide- (dead cells stain; red) stained cells collected at 24 h of growth in SM broth. In the wild type, but not in the sigK mutant, development of spore refractility is accompanied by loss of mother cell viability. (B) Percentage of the sporulating cells of the wild type and sigK mutant strains (i.e., with visible spores) showing signs of mother cell lysis (red; propidium iodide staining) as scored by direct microscopic observation, 24 hours after inoculation in SM medium. Values are the average ± SD of three independent experiments; “n” represents the total number of cells analyzed. (C) The sigK-skin region of the 630Δerm chromosome and plasmids used to complement sigK mutant strain. Replicative plasmid pFT38 carries sigK interrupted by a shorter version of the skinCd element, which includes the gene (CD12310) for the recombinase (in orange). Replicative plasmid pFT42 carries an uninterrupted sigK gene. The coding sequences are numbered according to the reanotation of the C.difficile genome [91]. (D) Percentage of sporulation for strains 630Δerm (wt), sigK and sigK bearing either pFT38 or pFT42. The indicated percentages are the ratio between the titer of heat resistant spores and the total cell titer, measured 72 h following inoculation in SM medium. Values are the average ± SD of three independent experiments. (E) Fluorescence microscopy showing the phenotype of sigK bearing pFT42. Cells were collected at 72 h of growth in SM broth, stained with DAPI and FM4-64, and viewed by phase contrast (PC) and fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar in (A) and (E), 1 µm. Lastly, our complementation analysis of the sigK mutant provided additional functional insight. While wild type levels of sporulation could be restored to a sigK mutant by a copy of the sigK gene bearing a deletion of all the genes within the skinCd element but the recombinase gene (Figure 3C; see above), an uninterrupted copy of the gene, in plasmid pFT42, did not restore sporulation (Figure 3C and D). An earlier study has suggested that the absence of skinCd correlates with a sporulation defect and that a skinCd- allele of sigK is dominant over the wild type [39]. Our results support the view that generation of an intact sigK gene through SpoIVCA-mediated excision of the skinCd element is essential for sporulation. Moreover, we found that introduction of the multicopy skin-less allele in strain 630Δerm blocked sporulation at an early stage, as no asymmetrically positioned septa could be seen in the transformed strain (Figure 3E). The results suggest that the absence of skinCd allows the production of active σK in pre-divisional cells, and that active σK interferes with the events leading to asymmetric septation in C. difficile.

Localizing the expression of the sporulation-specific sig genes

Having established the main features of sporulation under our culturing conditions, as well as the phenotypes associated with disruption of the sig genes, we next wanted to examine cell type-specific gene expression in relation to the course of morphogenesis. As a first step, we examined the expression of the genes coding for σF, σE, σG, and σK using the SNAPCd cassette as a transcriptional reporter. In control experiments, detailed in Text S1, in which expression of SNAPCd was placed under the control of the anhydrotetracycline-inducible promoter Ptet (Figure S5A) [59], we showed that complete labeling of all the SNAP produced could be achieved; furthermore, no background was detected for non-induced but labeled cells, or for unlabeled cells producing the SNAP reporter, by either fluorescence microscopy or the combination of fluorimaging and immunobloting with an anti-SNAP antibody, of SDS-PAGE resolved whole cell extracts (Figure S6).

The promoter regions of sigF, sigE, sigG, and sigK genes were cloned in the SNAPCd-containing promoter probe vector pFT47 (Figure S5B). The upstream boundaries of the promoter fragments fused to SNAPCd coincide with the 5′-end of the fragments used for the successful complementation of the various sig mutants (Figure 3C and S4A; see above). To monitor the production of SNAP during C. difficile sporulation, samples of cultures expressing each of the promoter fusions were collected at 24 h of growth in SM medium, and the cells doubly labeled with TMR-Star and the membrane dye MTG, to allow identification of the different stages of sporulation. These were defined based on Figure 1B, with the addition of a class of pre-divisional cells (no signs of asymmetric division). Expression of the various Psig-SNAPCd transcriptional fusions could thus be correlated to the stage in spore morphogenesis. Expression of both sigF and sigE was first detected in pre-divisional cells of the wild type strain 630Δerm, but not in cells of a spo0A mutant (Figure 4), consistent with previous reports [60]–[62] (Figure S7A and B). Both genes continued to be expressed following asymmetric division, in the forespore and the mother cell of both the wild type, and the sigF or sigE mutants (Figure 4). In these experiments, complete labeling of the SNAP protein was achieved, as revealed by fluorimaging and immunobloting of SDS-PAGE resolved proteins in whole cell extracts (Figure 5A). Quantification of the fluorescence signal shows that while for sigF the average intensity did not differ much between forespores (1.8±0.5), and mother cells (1.8±0.5), it increased in both the forespore and the mother cell relative to pre-divisional cells (average signal, 1.5±0.4) (p<0.01). Transcription of sigE, in turn, was lower in the forespore (average signal, 0.8±0.3) as compared to pre-divisional cells (1.0±0.3) or the mother cell (1.0±0.3) (p<0.0001) (Figure 5B). Thus, transcription of sigE, seems to occur preferentially in the mother cell. Transcription of both sigF and sigE persisted in both the forespore and the mother cell until a late stage of sporulation, when the forespore becomes phase bright (Figure 4).

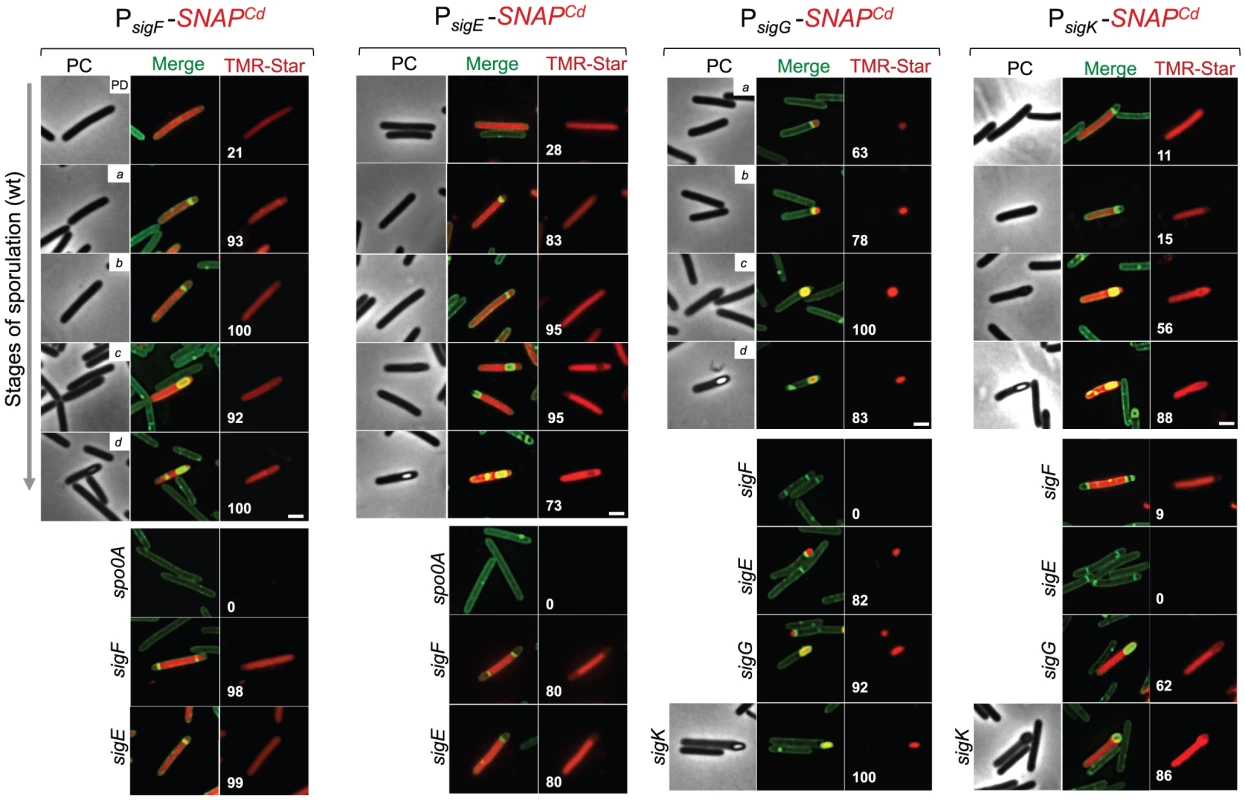

Fig. 4. Temporal and cell type-specific expression of sigF, sigE, sigG and sigK during sporulation.

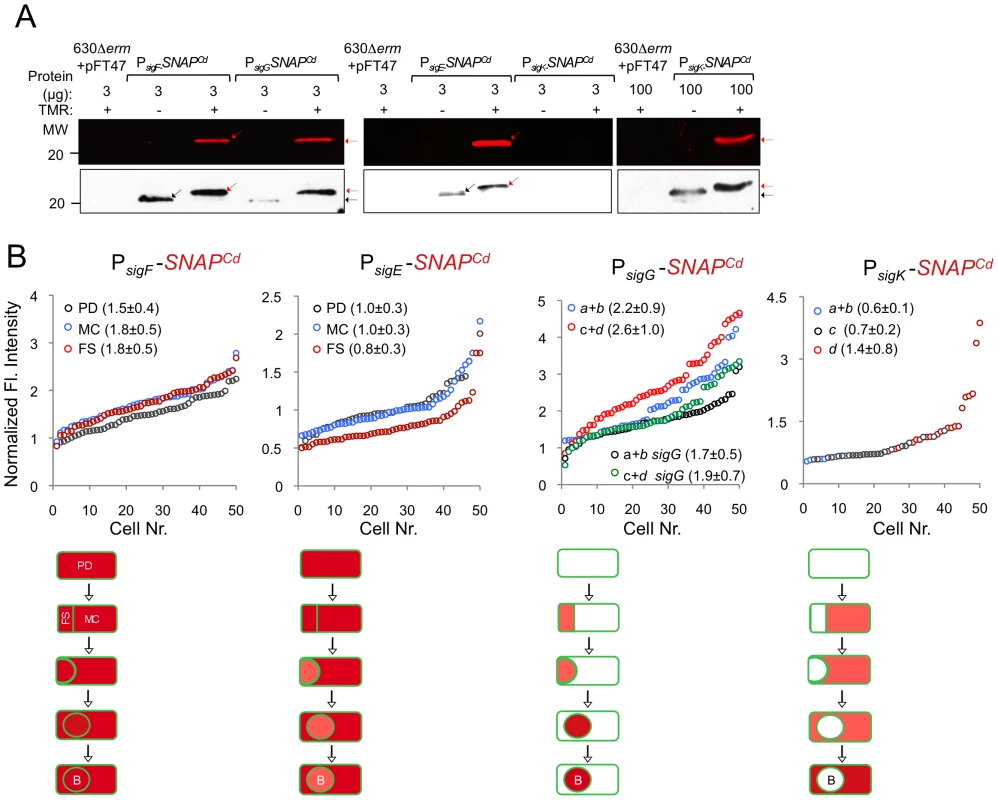

Microscopy analysis of C. difficile cells carrying fusions of the sigF, sigE, sigG and sigK promotors to SNAPCd in strain 630Δerm (wt) and in the indicated mutants. The cells were collected after 24 h of growth in SM liquid medium, stained with TMR-Star and the membrane dye MTG, and examined by phase contrast (PC) and fluorescence microscopy to monitor SNAP production. The merged images shows the overlap between the TMR-Star (red) and MTG (green) channels. The panels are representative of the expression patterns observed for different stages of sporulation, ordered from early to late for the wild type strains according to the morphological classes a-d defined in Figure 1, as indicated. For the sig strains, the morphological stage characteristic of each mutant is indicated. An extra class that accounts for pre-divisional cells (PD) was introduced for the analysis of both sigF and sigE transcription. The numbers refer to the percentage of cells at the represented stage showing SNAP fluorescence. The data shown are from one representative experiment, of three performed independently. The number of cells analysed for each class, n, is as follows: PD, n = 100–150; class a, n = 30–50; class b, n = 50–60; class c, n = 30–40; class d, n = 15–25; for sigF/E mutants, n = 80–120; for sigG and sigK mutants, n = 40–50. Scale bar: 1 µm. Fig. 5. Quantitative analysis of sigF, sigE, sigG and sigK expression during sporulation.

(A) Whole cell extracts were prepared from derivatives of strain 630Δerm bearing the indicated plasmids or fusions, immediately after labeling with TMR-Star, indicated by the “+” sign (the “−” sign indicates control, unlabeled samples). The indicated amount of total protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the gels scanned on a fluorimager (top) or subject to immunoblotting with anti-SNAP antibodies (bottom). Black and red arrows point to unlabeled or TMR-Star-labeled, respectively, SNAP. Strain 630Δerm carrying pFT47 (empty vector) was used as a negative control for SNAP production. The position of molecular weight markers (in kDa) is indicated. (B) Quantitative analysis of the fluorescence (Fl.) intensity in different cell types of the reporter strains for sigF, sigE, sigG and sigK transcription, as indicated. The numbers in the legend represent the average ± SD of fluorescence intensity for the cell class considered (n = 50 cells analysed for each morphological cell class). The data shown are from one experiment, representative of three independent experiments. Schematic representation of the deduced spatial and temporal pattern of transcription (with darker red denoting increased transcription) is shown for each transcriptional fusion. The cell membrane is represented in green. PD, pre-divisional cell; MC, mother cell; FS, forespore; B, phase bright spore; a to d: sporulation classes as defined in Figure 1. In contrast to sigF and sigE, transcription of sigG and sigK was confined to the forespore and to the mother cell, respectively (Figure 4). Transcription of sigG is detected in the forespore just after asymmetric division, consistent with the presence of a σF-type promoter in its regulatory region (Figure S7C). In agreement with this inference, expression of PsigG-SNAPCd was not detected in cells of a sigF mutant (Figure 4). Transcription of sigG was detected until the development of spore refractility (Figure 4). Fluorimaging and immunoblot analysis of whole cell extracts shows that under the conditions used, all of the SNAP protein detected was labeled (Figure 5A). In B. subtilis, σF initiates transcription of sigG in the forespore [48], [63]. However, transcription of sigG also depends on σE, by an unknown mechanism [64]. In contrast, forespore-specific expression of PsigG-SNAPCd was detected in most cells (82%) of a sigE mutant (Figure 4). In B. subtilis, the main period of sigG transcription takes place following engulfment completion, and relies on a positive auto-regulatory loop [65]. We detected transcription of sigG both prior and following engulfment completion in a sigG mutant (Figure 4). However, the quantitative analysis of the SNAP-TMR signal shows an increase in the average fluorescence intensity following engulfment completion (classes c+d, 2.6±1.0 as opposed to 2.2±0.9 for classes a+b) (p<0.01) (Figure 5B). Moreover, the average fluorescence signal for engulfed forespores of a sigG mutant suffered a higher reduction compared to the wild type (classes c+d, 1.9±0.7 for the mutant as compared to 2.6±1.0 for the wild type; p<0.01), than did the signal for pre-engulfment forespores of the mutant (classes a+b, 1.7±0.5 as opposed to 2.2±0.9; p<0.05) (Figure 5B). While evidencing that σG contributes to transcription of its own gene both prior to and following engulfment completion, these results suggest that the auto-regulatory effect is stronger at the later stage.

In C. difficile, transcription of sigK was confined to the mother cell and detected soon after asymmetric division (Figure 4). Moreover, disruption of sigE resulted in undetected expression of PsigK-SNAPCd (Figure 4). Together, the results suggest that the initial transcription of sigK is activated by σE in the mother cell, consistent with the presence of a possible σE-recognized promoter in the sigK regulatory region (Figure S7D). Interestingly, transcription of the sigK gene was also detected in a small percentage (9%) of the sporulating cells of a sigF mutant (Figure 4). This was unexpected because in B. subtilis, activation of σE in the mother cell is dependent on σF [66], [67]. This observation thus raises the possibility that the activation of σE in C. difficile is at least partially independent of σF (see also the following section). Transcription of sigK was also detected following engulfment completion, in cells carrying phase grey and phase bright spores (Figure 4). As shown in Figure 5A, all of the SNAP produced from the PsigK-SNAPCd fusion was, under our experimental conditions, labeled. The average intensity of the fluorescence signal from PsigK-SNAPCd in cells prior (classes a+b, 0.6±0.1) and after engulfment completion (class c, 0.7±0.2) was very close. However, expression was significantly increased for those cells that carried phase bright spores (class d, 1.4±0.8; p<0.001) (Figure 5B). This suggests that the onset of the main period of sigK transcription coincides with the final stages in spore morphogenesis. Lastly, under our experimental conditions, we found no evidence for auto-regulation of sigK transcription, as expression of PsigK-SNAPCd was not curtailed by mutation of sigK at any morphological stage analyzed (Figure 4 and data not shown).

Localizing the activity of σF and σE

To investigate the genetic dependencies for sigma factor activity during sporulation in C. difficile, we used transcriptional SNAPCd fusions to promoters under the control of each cell type-specific sigma factor. These promoters were selected on the basis of qRT-PCR experiments and the presence on their regulatory regions, of sequences conforming well to the consensus for promoter recognition by the sporulation sigma factors of B. subtilis [68] (Figure S8). The gpr gene of B. subtilis codes for a spore-specific protease required for degradation of the DNA-protecting small acid-soluble spore proteins (SASP) during spore germination ([1]; see also below). Even though this gene is under the dual control of σF and σG in B. subtilis, the C. difficille orthologue of gpr (CD2470) was chosen as a reporter for σF activity (Figure S8A). First, qRT-PCR showed that transcription of the C. difficille orthologue (CD2470) was severely reduced in a sigF mutant (Figure 6A). Secondly, expression of a Pgpr-SNAPCd fusion, monitored by fluorescence microscopy, was confined to the forespore and detected soon after asymmetric division in 66% of the cells that were at this stage of sporulation (Figure 6B). Lastly, expression was eliminated by disruption of the sigF gene but detected in 99% of the cells of the sigG mutant (compared for the wild type at the same stage, i.e., 95%) (Figure 6B). This suggests that σG does not contribute significantly to gpr expression. Forespore-specific expression of Pgpr-SNAPCd was also detected following engulfment completion (Figure 6B). Therefore, in spite of expression of the sigF gene in both the forespore and the mother cell, σF is active exclusively in the forespore. In these experiments, all of the SNAP protein produced from Pgpr-SNAPCd was labeled with the TMR-Star substrate (Figure 7A). A quantitative analysis of the fluorescence signal from Pgpr-SNAPCd showed no significant difference between cells before (average signal for classes a+b, 2.0±0.5) or after engulfment completion (classes c+d, 1.9±0.7) (Figure 7B). This suggests that σF is active in the forespore throughout development.

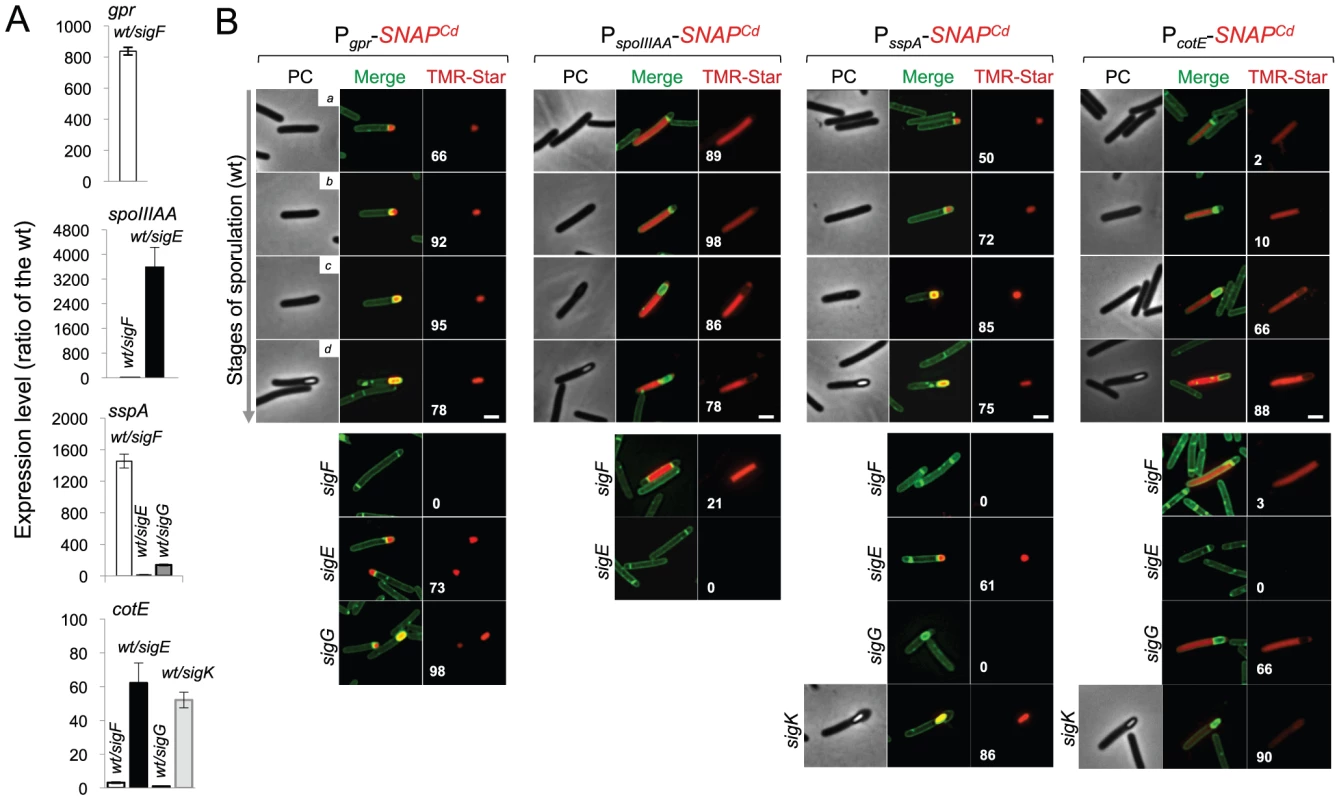

Fig. 6. Dependencies for the activation of the cell type-specific sporulation sigma factors.

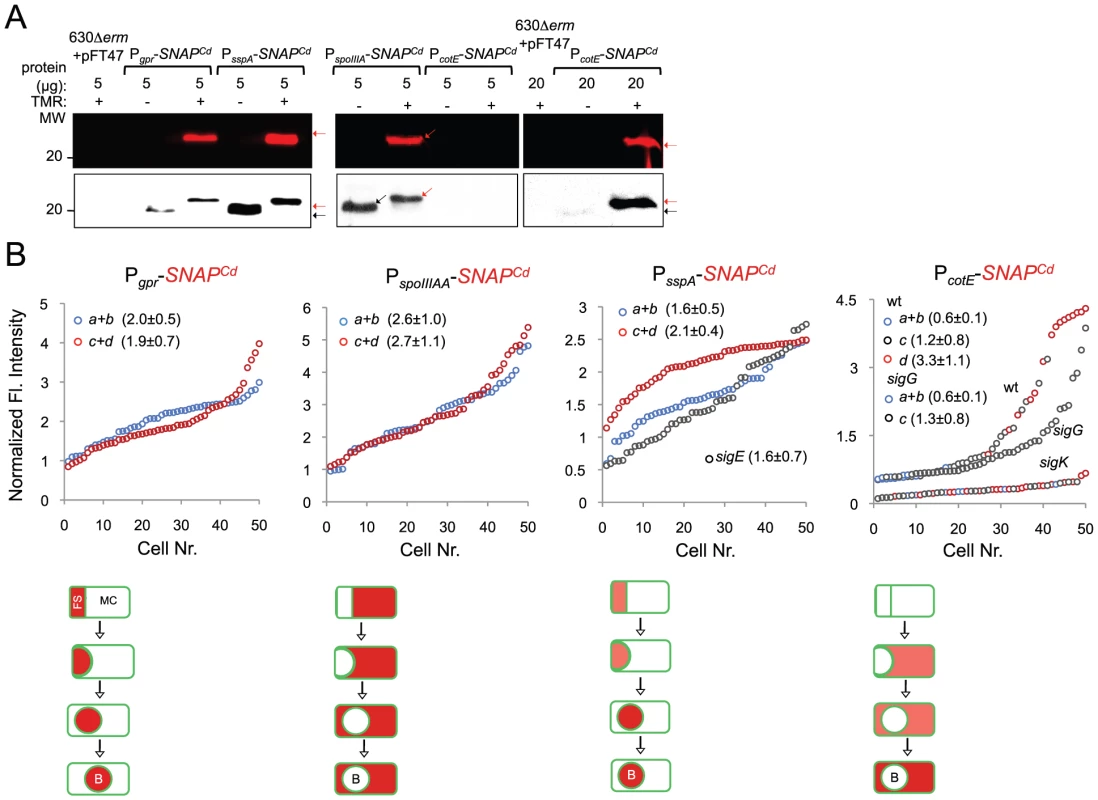

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of gpr, spoIIIAA, sspA and cotE gene transcription in strain 630Δerm (wt), and in congenic sigF, sigE, sigG and sigK mutants. RNA was extracted from cells collected 14 hours (gpr and spoIIIAA), 19 hours (sspA) and 24 hours (cotE) after inoculation in SM liquid medium. Expression is represented as the fold ratio between the wild type (wt) and the indicated mutants. Values are the average ± SD of two independent experiments. (B) Cell type-specific expression of transcriptional fusions of the gpr, spoIIIAA, sspA and cotE promoters to SNAPCd in the wild type and in the indicated congenic mutants. For each of the strains, expressing the indicated fusions, cells were collected from SM cultures 24 h after inocculation and labeled with TMR-Star (red) and with the membrane dye MTG (green). Following labeling, the cells were observed by phase contrast (PC) and fluorescence microscopy. Merge is the overlap between the TMR-Star (red) and MTG (green) channels. The images are ordered, and the morphological classes defined as in the legend for Figure 4. The numbers refer to the percentage of cells at the represented stage showing SNAP fluorescence. The data shown are from one experiment, representative of three independent experiments. The number of cells analysed for each class, n, is as follows: class a, 30–50; class b, n = 50–60; class c, n = 30–40; class d, n = 15–25; for sigF/E mutants, n = 80–120; for sigG and sigK mutants, n = 40–50. Scale bar: 1 µm. Fig. 7. Quantitative analysis of sigF, sigE, sigG and sigK activities during sporulation.

(A) SDS-PAGE gel and Western Blot analysis of extracts from 630Δerm carrying fusions of gpr, spoIIIAA, sspA and cotE to SNAP. Black arrows point to unlabeled SNAPCd protein, while red arrows point to SNAP after TMR-Star labeling (distinguishable in the WB from the unlabeled form by a shift in protein migration). The TMR-Star fluorescent signal from the SDS-PAGE gel was obtained using a fluorimager. TMR-Star incorporation as well as the amount of protein loaded is indicated for each lane. 630Δerm carrying pFT47 empty vector was used as a negative control of SNAP production. (B) Quantitative analysis of the SNAP fluorescence (Fl.) signal in different cell types of the reporter strains for σF, σE, σG and σK activity, as indicated. The numbers in the legend represent the average ± SD of fluorescence intensity for the cell class considered (NB: 50 cells were analysed for each cell type). The average fluorescence intensity (all classes included) from PcotE-SNAPCd is 1.9±1.3 for the wild type, 1.3±0.8 for a sigG mutant and 0.3±0.1 for the sigK mutant. Data shown are from one experiment, representative of three independent experiments. Schematic representation of the deduced spatial and temporal pattern of transcription is shown for the different fusions (with darker red denoting increased transcription). The cell membrane is represented in green. No activity was seen in predivisional cells for any of the σ factors (not represented). PD, pre-divisional cell; MC, mother cell; FS, forespore; B, phase bright spore; a to d: sporulation classes ordered and defined as in the legend for Figure 4. To monitor the activity of σE, we examined expression of the first gene, spoIIIAA, of the spoIIIA operon. This operon is under the control of σE in B. subtilis [69]–[71] and sequences that conform well to the consensus for promoter recognition by B. subtilis σE are found just upstream of the C. difficile spoIIIAA gene (or CD1192) (Figure S8B). The qRT-PCR experiments showed that expression of spoIIIAA was much more severely affected by a mutation in sigE than by disruption of sigF (Figure 6A). While consistent with a direct control of spoIIIAA by σE, this observation adds to the evidence suggesting that unlike in B. subtilis [21], [66], [67], the activity of σE is at least partially independent on the prior activation of σF (as also hinted by the observation that transcription of the sigK gene, abolished by mutation of sigE, was still detected in a fraction of cells of a sigF mutant; above). If so, then expression of a PspoIIIAA-SNAPCd fusion should be confined to the mother cell, dependent on sigE, but partially independent on sigF. PspoIIIAA-SNAPCd-driven SNAP production was indeed confined to the mother cell, detected just after asymmetric division in 89% of the cells scored at this stage of sporulation, eliminated by mutation of sigE, but still detected (in the mother cell) in 21% of sigF cells (Figure 6B). Labeling of the SNAP protein produced from the PspoIIIAA-SNAPCd fusion was quantitative (Figure 7A), and the quantitative analysis of the average fluorescence signal shows no significant difference in expression levels before or after engulfment completion (Figure 7B). PspoIIIAA-SNAPCd expression persisted until late stages in development, and was still detected for cells in which phase bright spores were seen (Figure 7B).

Requirements for the activity of σG and σK

The sspA gene of B. subtilis codes for a small acid-soluble spore protein (SASP) that, together with other SASP family members, binds to and protects the spore DNA [1]. Expression of sspA in B. subtilis is controlled by σG [68], [69], and a σG-type promoter can be recognized upstream of the C. difficile orthologue (CD2688) (Figure S8C). Unexpectedly, a mutation in sigF caused a greater decrease in sspA transcription than disruption of sigE or sigG, in our qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 6A). While not excluding a contribution of σF to the expression of sspA, this result may be affected by the lack of synchronization of sporulation in the liquid SM cultures. Consistent with σG control of sspA in C difficile, PsspA-driven SNAP production was confined to the forespore and eliminated by disruption of sigF or of sigG (but not of sigE or sigK) (Figure 6B). This is in agreement with the requirement for σF for the transcription of sigG (above), and seems to exclude a contribution of σF for sspA transcription as suggested by the qRT-PCR analysis. sspA expression was detected in 50% of the cells that had just completed asymmetric division, but also throughout the engulfment sequence (72% of the cells), following engulfment completion (85% of the cells scored), and in cells (75%) carrying phase bright spores (Figure 6B). Our analysis of sigG transcription suggested that it increased following engulfment completion, with a stronger auto-regulatory component than in pre-engulfed cells (above). In B. subtilis, continued transcription in the forespore when (upon engulfment completion) it becomes isolated from the surrounding medium, requires the activity of σE [72]–[76]. To determine whether the activity of σG increased following engulfment completion in a manner that required σE, we quantified the SNAP-TMR signal in cells expressing PsspA-SNAPCd. Control experiments showed that all the SNAP protein produced from the PsspA-SNAPCd fusion was labeled with the TMR-Star substrate (Figure 7A). The average intensity of the SNAP-TMR signal increased from 1.6±0.5 before engulfment completion (classes a+b) to 2.1±04, following engulfment completion (classes c+d) (p<0.0001) (Figure 7B). This result is consistent with the analysis of sigG transcription (above) and indicates that the activity of σG increases following engulfment completion. Importantly, even though sspA expression was found for 61% of the sigE mutant cells, disruption of sigE reduced the average fluorescence signal in the forespore (1.6±0.7) to the level seen before engulfment completion for the wild type (1.6±0.5). We conclude that disruption of sigE does not prevent activity of σG prior to engulfment completion.

Finally, to monitor the activity of σK, we examined expression of the cotE gene, coding for an abundant spore coat protein in C. difficile [55]. This gene has no counterpart in B. subtilis, but as shown above, production of a CotE-SNAP translational fusion was dependent on σK (Figure 2E) and a sequence that conforms well to the consensus for σK promoters of B. subtilis can be recognized in its promoter region (Figure S8D). qRT-PCR experiments show that disruption of the sigE and sigK genes caused a much stronger reduction in the expression of cotE than mutations in sigF or sigG (Figure 6A). While not excluding a contribution from σE, the qRT-PCR data are in line with the interpretation that the main regulator of cotE expression is σK (with σE driving production of σK). We note that the reduced effect of the sigF mutation on cotE expression is in agreement with the view that σE production is partially independent on σF, as discussed above. We also note that the reduced effect of the sigG mutation on cotE expression is in agreement with the morphological analysis and the data on the assembly of the CotE-SNAP fusion (Figure 2D and E), suggesting σK-dependent deposition of coat material independently of σG. Fluorescence microscopy reveals that expression of PcotE-SNAPCd is confined to the mother cell (Figure 6B). However, expression of PcotE-SNAPCd was found just after asymmetric division in only 2% of the cells, and during engulfment in only 10% of the cells (Figure 6B). Expression increased to 66% of the cells after engulfment completion, and to 88% of the cells that showed phase bright spores (Figure 6B). Expression of PcotE-SNAPCd was eliminated by disruption of sigE, but retained in 3% of the sporulating cells of a sigF mutant (Figure 6B). This is consistent with data presented above, also in line with the inference that the activity of σK is partially independent on sigF (Figure 6A and B). Moreover, 66% of the cells of a sigG mutant that had completed the engulfment process (as illustrated in Figure 6B) showed expression of the reporter fusion, again suggesting σK activity independently of σG. Interestingly, disruption of sigK did not abolish expression of the fusion, which was detected in 90% of the sporulating cells, but at low levels (Figure 6B). This raises the possibility that σE is responsible for the few cells that produce the reporter prior to engulfment completion.

To test these possibilities quantitatively, we first verified that all the SNAP-tag produced from the PcotE-SNAPCd fusion was labeled, under our experimental conditions (Figure 7A). The average intensity of the SNAP-TMR signal was of 0.6±0.1 for cells of the wild type strain prior to engulfment completion (classes a+b), of 1.2±0.8 for those that had just completed engulfment (class c), and of 3.3±1.1 for cells with phase bright spores (class d) (Figure 7B). Inactivation of sigG did not affect the expression level of the fusion prior to engulfment completion (classes a+b for the sigG mutant, average signal, 0.6±0.1), nor did it prevent expression following engulfment completion (class c of the sigG mutant, 1.3±0.8) (Figure 7B). However, the average fluorescence signal for all classes of the sigG mutant (1.3±0.8) is significantly lower than the average for all classes of the wild type (1.9±1.3) (p<0.001) (Figure 7B). Finally, the average fluorescence signal for all cells of the sigK mutant was lower (0.3±0.1) than for pre-engulfment cells of the wild type (classes a+b, 0.6±0.1) (p<0.0001), suggesting that both σE and σK contribute to expression of the reporter fusion in these cells. Together, these data suggest that the main period of σK activity is delayed relative to engulfment completion, and coincides with development of spore refractility.

Discussion

In this work, we analyzed the function of the four cell type-specific sigma factors of sporulation in C. difficile, and we studied gene expression in relation to the course of spore morphogenesis. The morphological characterization of mutants for the sigG genes allowed us to assign functions and to define the main periods of activity for the 4 cell type-specific sporulation sigma factors. In addition, the use of a fluorescence transcriptional reporter for single cell analysis enabled us to establish the time, cell type and dependency of transcription of the sig genes, as well as the time and requirements for activity of the four cell type-specific sigma factors.

Transcription of sigF and sigE, and activity of σF and σE

The cytological and TEM analysis shows that the sigF and sigE mutants are arrested just after asymmetric division. It follows that σF and σE control early stages of development in C. difficile, consistent with the function of these sigma factors in B. subtilis. Disruption of sigE also arrested development just after asymmetric division in C. perfringens [29]. In contrast, disruption of either the sigF or sigE genes in C. acetobutylicum blocks sporulation prior to asymmetric division [31], [33]. In C. difficile, expression of both sigF and sigE commenced in predivisional cells, in line with work showing that expression of the sigF-containing operon (also coding for two other proteins, SpoIIAA and SpoIIAB, that control σF) occurs from a σH and Spo0A-controlled promoter, and with the observation that transcription of sigE is activated from a σA-type promoter to which Spo0A also binds [60], [61]. In B. subtilis, following asymmetric septation, Spo0A becomes a cell-specific transcription factor, active predominantly in the mother cell [77]. This may also be the case in C. difficile, because transcription of sigE increased in the mother cell, relative to the forespore, following asymmetric division (Figure 7B).

In B. subtilis, σF is held in an inactive complex by the anti-sigma factor SpoIIAB [21], [23]. The reaction that releases σF takes place specifically in the forespore, soon after septation, and involves the anti-anti sigma factor SpoIIAA and the SpoIIE phosphatase. SpoIIAB, SpoIIAA and SpoIIE are produced in the C. difficile predivisional cell under Spo0A control [24]–[27], [60], [61]. Because the activity of σF was confined to the forespore, we presume that the pathway leading to the forespore-specific activation of this sigma factor is also conserved. In C. acetobutylicum, this pathway may lead to σF activation in pre-divisional cells, as disruption of sigF or spoIIE blocks sporulation prior to asymmetric division [33], [35].

In B. subtilis, σE is also synthesized in the predivisional but as an inactive pro-protein [21], [23]. Processing of pro-σE in the mother cell requires activation of the SpoIIGA protease by SpoIIR, a σF-controlled signaling protein secreted from the forespore [66], [67]. Hence, the activity of σE requires the prior activation of σF. In C. difficile, the activity of σE was also restricted to the mother cell (Figure 7B). Because σE of C. difficile bears, like its B. subtilis counterpart, a pro sequence, and because the SpoIIGA protease and SpoIIR are conserved [24]–[27], the σE activation pathway also seems conserved. Strikingly however, both the qRT-PCR and the SNAP labeling experiments showed that the activity of σE is at least partially independent on σF (Figure 6). We do not know whether production of SpoIIR is also partially independent on σF. However, in C. acetobutylicum, in which σF is activated (and required) prior to asymmetric septation [33], [35], production of SpoIIR is, at least in part, independent of σF [33].

Production and activity of σG

The cytological and TEM analysis showed that a sigG mutant completes the engulfment sequence, suggesting that σG is mainly required for late stages in development, consistent with its role in B. subtilis. Disruption of sigG also causes a late morphological block in C. acetobutylicum [78]. In B. subtilis, the forespore-specific transcription of sigG is initiated by σF but is delayed, relative to other σF-dependent genes, towards the engulfment sequence [21], [64], [68], [69]. Moreover, the activity of σE, in the mother cell, is required for transcription of sigG [21], [64]. In contrast, transcription of sigG in C. difficile, was detected soon after asymmetric septation, and was not dependent on σE (Figure 4 and 5). Transcription of sigG also appears to be independent of sigE in C. perfringens [29]. The main period of sigG transcription in B. subtilis relies on an auto-regulatory loop activated coincidently with engulfment completion [65]. Therefore, the main period of σG activity coincides with engulfment completion. At least the anti-sigma factor CsfB (σF-controlled) appears important for impeding the σG auto-regulatory loop from functioning prior to engulfment completion, the main period of activity of the preceding forespore sigma factor, σF [21], [23], [72], [79], [80]. CsfB is absent from C. difficile as well as from other Clostridia [24], [25], [27]. In C. difficile, not only is transcription of sigG observed soon after asymmetric division, but the activity of σG, is also detected prior to engulfment completion. Nevertheless, our analysis indicates that σG activity increases following engulfment completion. In addition, our results suggest that σG is auto-regulatory both before, and more markedly, following engulfment completion.

A universal feature of endosporulation is the isolation of the forespore, surrounded by two membranes, from the external medium at the end of the engulfment sequence. In B. subtilis, the 8 mother cell proteins encoded by the spoIIIA operon, which localize to the forespore outer membrane, and the forespore-specific SpoIIQ protein, which localizes to the forespore inner membrane, are involved in the assembly of a specialized secretion system that links the cytoplasm of the two cells [72]–[76]. Recent work has shown that the SpoIIIA-SpoIIQ secretion system functions as a feeding tube required for continued macromolecular synthesis in the engulfed forespore [76]. Mutation of sigE reduced the activity of σG but because the mutant is blocked at an early stage, we do not presently know whether σE is required for σG activity in the engulfed forespore. The SpoIIIAH and SpoIIQ proteins also facilitate forespore engulfment in B. subtilis [81]. The spoIIIA operon is conserved in sporeformers [24], [25], [27], and spoIIIA is under σE control in C. difficile (this work). A gene, CD0125, coding for a LytM-containing protein (as the B. subtilis SpoIIQ protein) may represent a non-orthologous gene replacement of spoIIQ [24]. We do not yet know whether spoIIIA and CD0125 are essential for sporulation in C. difficile and if so, whether they are required for engulfment and/or continued gene expression in the engulfed forespore.

Production and activity of σK

The TEM analysis shows that the sigK mutant of C. difficile lacks a visible coat (Figure 2D). However, as in B. subtilis [15], [16] assembly of the coat begins with σE, as suggested by the forespore localization of CotB-SNAP in cells of the sigK mutant, and supported by recent work on the analysis of coat morphogenetic proteins SpoIVA and SipL [42]. Most likely, σK controls the final stages in the assembly of the spore surface structures, including the coat and exosporium. However, σK is not a strict requirement for the formation of heat resistant spores (Figure 2 and Table 1), and we presume that σE and σG (see above) are largely responsible for synthesis of the spore cortex. Final assembly of the coat together with the role of C. difficile σK in mother cell autolysis, are functions shared with its B. subtilis counterpart.

Transcription and activity of the C. difficile sigK gene was dependent on sigE, and was detected at low levels prior to engulfment completion. However, both transcription and activity increased, following engulfment completion, coincidently with the appearance of phase grey and phase bright spores. Transcription of the sigK and spoIVCA genes of B. subtilis, the latter coding for the recombinase that excises the skin element, is initiated under the control of σE with the assistance of the regulatory protein SpoIIID, and is delayed relative to a first wave of σE-directed genes [21], [23], [69], [70]. SpoIIID is conserved in C. difficile [27] and it may only accumulate to levels sufficient to enhance sigK and spoIVCA transcription at late stages in morphogenesis. Two observations highlight the importance of the skin element in C. difficile. First, with the exception of an asporogenous strain of C. tetani, the skin element is not present in other Clostridial species [17], [39]. Second, not only a skin-less allele of sigK fails to complement a sigK mutation but also acts as a dominant negative mutation [39], blocking entry into sporulation (Figure 3D and E) (while these results seem to imply that σK is auto-regulatory, we did not detect auto-regulation of sigK in our single cell analysis). Absence of the skin element may allow the recruitment of σK for other functions. In C. perfringens and in C. botulinum, σK is produced in pre-divisional cells, and is involved in enterotoxin production in the first, and in cold and osmotic stress tolerance in the second [29], [82].

A key finding of the present study is that contrary to B. subtilis, sigG is not essential for the activity of σK. In B. subtilis a signaling protein, SpoIVB, secreted from the forespore activates the pro-σK processing protease SpoIVFB, which is kept inactive in a complex with BofA and SpoIVFA, embedded in the forespore outer membrane [21], [22]. SpoIVFB, BofA and possibly also SpoIVFA are absent from C. difficile, suggesting that the σG to σK pathway is absent and consistent with the lack of a pro-sequence [24], [27], [36]. However, C. difficile codes for two orthologues of SpoIVB [24], [25], [27]. Mutations that bypass the need for sigG or spoIVB in B. subtilis result in coat deposition, but not cortex formation, phenocopying the sigG mutant of C. difficile [50]. In B. subtilis, SpoIVB is also required for the engulfment-regulated proteolysis of SpoIIQ [83]. The C. difficile SpoIVB orthologues may be involved in cortex formation and/or proteolysis of CD0125 (above).

While the activity of σK did not require σG, our data shows that mutation of sigG reduced the activity of σK at late stages of spore morphogenesis. Because the sigG mutant fails to form phase grey/bright spores, we do not presently know if a forespore-mother cell signaling operates at this stage, or whether the late stages in spore morphogenesis serve as a cue for enhanced activity of σK.

Concluding remarks

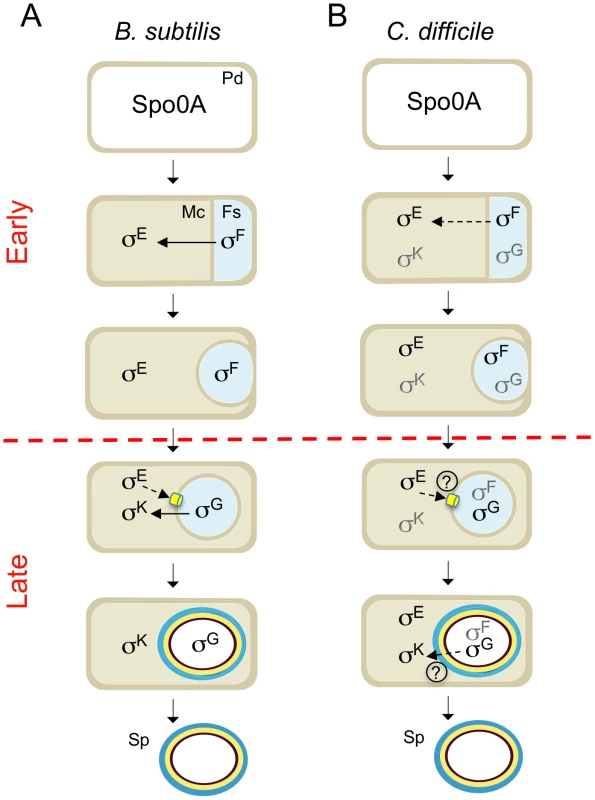

We show that the main periods of activity of the four cell type-specific sigma factors of C. difficile are conserved, relative to the B. subtilis model, with σF and σE controlling early stages of development and σG and σK governing late developmental events (Figure 8A and B). However, the fact that the activity of σE was partially independent of σF, and that σG or σK did not require σE or σG, respectively, seems to imply a weaker connection between the forespore and mother cell lines of gene expression. In spite of the important differences in the roles of the sporulation sigma factors and the regulatory circuits leading to their activation (Figure 8A and B), overall, in what concerns the genetic control of sporulation, C. difficile seems closer to the model organism B. subtilis than the other Clostridial species that have been studied. Differences in the function/period of activity of the sporulation sigma factors in other Clostridial species, may be related to the coordination of solventogenesis, toxin production or other functions with sporulation [28]–[35]. We note however that the relationship between toxinogenesis and spore formation in C. difficile is still unclear [13], [60].

Fig. 8. Stages and cell of σF, σE, σG and σK activity.

The figure compares the main periods of activity of the 4 cell type-specific sigma factors of sporulation in B. subtilis (A) and C. difficile (B). The figure incorporates data on the morphological analysis of sporulation in the sigF, sigE, sigG and sigK mutants (Figure 2, 4 and 6) and on the stage, dependencies and cell where σF, σE , σG and σK are active. Solid or broken arrows represent dependencies or partial dependencies, respectively. The representation of the C. difficile sigma factors indicates activity; black indicates the main period of activity. Possible cell-cell signaling pathways are show by both a broken line and a question mark. The SpoIIIA-SpoIIQ/CD0125 channel is represented in yellow. PD: predivisional cell; MC: mother cell; FS: forespore. The red horizontal broken line distinguishes early (prior to engulfment completion) from late (post-engulfment completion) development. Together with the accompanying work of Saujet and co-authors [62], our study provides the first comprehensive description of spore morphogenesis in relation to cell type-specific gene expression in a Clostridial species that is also an important human pathogen. The two studies establish a platform for analyzing the control of toxin production in relation to C. difficile sporulation, and for the functional characterization of genes predicted to be important for spore functions related to host colonization, spore germination, recurrent sporulation in the host, and spore dissemination.

Materials and Methods

Strains and general techniques

Bacterial strains and their relevant properties are listed in Table S2. The Escherichia coli strain DH5α (Bethesda Research laboratories) was used for molecular cloning. Luria-Bertani medium was routinely used for growth and maintenance of E. coli and B. subtilis. The B. subtilis strains are congenic derivatives of the Spo+ strain MB24 (trpC2 metC3). Sporulation of B. subtilis was induced by growth and exhaustion in Difco sporulation medium (DSM) [84]. When indicated, ampicillin (100 µg/ml) or chloramphenicol (15 µg/ml) was added to the culture medium. The C. difficile strains used in this study are congenic derivatives of the wild type strain 630Δerm [85] and were routinely grown anaerobically (5% H2, 15% CO2, 80% N2) at 37°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Difco), BHIS [BHI medium supplemented with yeast extract (5 mg/ml) and L-cysteine (0.1%), or SM medium (for 1l: 90 g Bacto-tryptone, 5 g Bacto-peptone, 1 g (NH4)2SO4 and 1.5 g Tris base)] [41]. Sporulation assays were performed in SM medium [41]. When necessary, cefoxitin (25 µg/ml), thiamphenicol (15 µg/ml), or erythromycin (5 µg/ml) was added to C. difficile cultures.

Sporulation assays

Overnight cultures grown at 37°C in BHI were used to inoculate SM medium (at a dilution of 1∶200). At specific time points, 1 ml of culture was withdrawn, serially diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Phosphate, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4), and plated before and after heat treatment (30 min at 60°C), to determine the total and heat-resistant colony forming units (CFU). The samples were plated onto BHI plates supplemented with 0.1% taurocholate (Sigma-Aldrich), to promote efficient spore germination [41]. The percentage of sporulation was determined as the ratio between the number of spores/ml and the total number of bacteria/ml times 100.

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative RT-PCR

In a preliminary set of experiments, we defined the time for which the difference in expression of a selected σ target gene between the wild type and the corresponding mutant strain was highest. To study σE - or σF-dependent control, we harvested cells from 630Δerm, sigF and sigE mutants after 14 h of growth in SM medium. Strain 630Δerm and the sigG or the sigK mutants were harvested after 19 h (630Δerm, sigG mutant) and 24 h (630Δerm, sigK mutant) of growth in SM medium. Total RNA was extracted from at least two independent cultures. After centrifugation, the culture pellets were resuspended in RNApro solution (MP Biomedicals) and RNA extracted using the FastRNA Pro Blue Kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA quality was determined using RNA 6000 Nano Reagents (Agilent). For quantitative RT-PCR experiments, 1 µg of total RNA was heated at 70°C for 10 min along with 1 µg of hexamer oligonucleotide primers p(dN)6 (Roche). After slow cooling, cDNAs were synthesized as previously described [61]. The reverse transcriptase was inactivated by incubation at 85°C for 5 min. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed twice in a 20 µl reaction volume containing 20 ng of cDNAs, 10 µl of FastStart SYBR Green Master mix (ROX, Roche) and 200 nM gene-specific primers in a AB7300 real-time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems). The primers used for each marker are listed in Table S3. Amplification and detection were performed as previously described [61]. In each sample, the quantity of cDNAs of a gene was normalized to the quantity of cDNAs of the DNApolIII gene. The relative transcript changes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method as described [61].

Transcriptional and translational SNAPCd fusions

The construction of transcriptional fusions of the promoters for the sigF, sigE, sigG and sigK genes, as well as the construction of translational fusions of cotB and cotE to the SNAP-tag [86] is described in detail in Text S1. In these plasmids, listed in Table S4, we used a synthetic SNAP cassette, codon usage optimized for C. difficile (DNA 2.0, Menlo Park, CA), which we termed SNAPCd (the sequence is available for download at www.itqb.unl.pt/~aoh/SNAPCdDNAseq.docx).

SNAP labeling and analysis

Whole cell extracts were obtained by withdrawing 10 ml samples from C. difficile cultures in brain heart infusion (BHI) for the Ptet-SNAP-bearing strains, or in SM medium for the sporulation experiments, at the desired times. The extracts were prepared immediately following labeling with 250 nM of the TMR-Star substrate (New England Biolabs), for 30 min in the dark. Following labeling, the cells were collected by centrifugation (4000×g, for 5 min at 4°C), the cell sediment was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 1 ml French press buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol, 1 mM PMSF). The cells were lysed using a French pressure cell (18000 lb/in2). Proteins in the extracts were resolved on 15% SDS-PAGE gels. The gels were first scanned in a Fuji TLA-5100 fluorimager, and then subject to immunoblot analysis as described before [65]. The anti-SNAP antibody (New England Biolabs) was used at a 1∶1000 dilution, and a rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma) was used at dilution 1∶10000. The immunoblots were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Microscopy and image analysis

Samples of 1 ml were withdrawn from BHI or SM cultures at the desired times following inoculation, and the cells collected by centrifugation (4000×g for 5 min). The cells were washed with 1 ml of PBS, and ressuspended in 0.1 ml of PBS supplemented with the lipophilic styryl membrane dye N-(3-triethylammoniumprpyl)-4-(p-diethylaminophenyl-hexatrienyl) pyridinium dibromide (FM4-64; 10 µg.ml−1) [43], [87], and the DNA stain DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; 50 µg.ml−1) (both from Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). For the live/dead assay, samples were collected as described above, ressuspended in 0.05 ml of PBS and mixed with an equal volume of 2× LIVE/DEAD BacLight 2× staining reagent mixture (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) containing Propidium iodide (30 µM final concentration) and syto9 (6 µM final concentration).

For SNAP labeling experiments, cells in culture samples were labeled with TMR-Star (as above), collected by centrifugation (4000×g, 3 min, at room temperature), washed four times with 1 ml of PBS, and finally ressuspended in 1 ml of PBS containing the membrane dye Mitotracker Green (0.5 µg.ml−1) (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen).