-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Regulatory T Cell Suppressive Potency Dictates the Balance between Bacterial Proliferation and Clearance during Persistent Infection

The pathogenesis of persistent infection is dictated by the balance between opposing immune activation and suppression signals. Herein, virulent Salmonella was used to explore the role and potential importance of Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells in dictating the natural progression of persistent bacterial infection. Two distinct phases of persistent Salmonella infection are identified. In the first 3–4 weeks after infection, progressively increasing bacterial burden was associated with delayed effector T cell activation. Reciprocally, at later time points after infection, reductions in bacterial burden were associated with robust effector T cell activation. Using Foxp3GFP reporter mice for ex vivo isolation of regulatory T cells, we demonstrate that the dichotomy in infection tempo between early and late time points is directly paralleled by drastic changes in Foxp3+ Treg suppressive potency. In complementary experiments using Foxp3DTR mice, the significance of these shifts in Treg suppressive potency on infection outcome was verified by enumerating the relative impacts of regulatory T cell ablation on bacterial burden and effector T cell activation at early and late time points during persistent Salmonella infection. Moreover, Treg expression of CTLA-4 directly paralleled changes in suppressive potency, and the relative effects of Treg ablation could be largely recapitulated by CTLA-4 in vivo blockade. Together, these results demonstrate that dynamic regulation of Treg suppressive potency dictates the course of persistent bacterial infection.

Published in the journal: Regulatory T Cell Suppressive Potency Dictates the Balance between Bacterial Proliferation and Clearance during Persistent Infection. PLoS Pathog 6(8): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001043

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001043Summary

The pathogenesis of persistent infection is dictated by the balance between opposing immune activation and suppression signals. Herein, virulent Salmonella was used to explore the role and potential importance of Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells in dictating the natural progression of persistent bacterial infection. Two distinct phases of persistent Salmonella infection are identified. In the first 3–4 weeks after infection, progressively increasing bacterial burden was associated with delayed effector T cell activation. Reciprocally, at later time points after infection, reductions in bacterial burden were associated with robust effector T cell activation. Using Foxp3GFP reporter mice for ex vivo isolation of regulatory T cells, we demonstrate that the dichotomy in infection tempo between early and late time points is directly paralleled by drastic changes in Foxp3+ Treg suppressive potency. In complementary experiments using Foxp3DTR mice, the significance of these shifts in Treg suppressive potency on infection outcome was verified by enumerating the relative impacts of regulatory T cell ablation on bacterial burden and effector T cell activation at early and late time points during persistent Salmonella infection. Moreover, Treg expression of CTLA-4 directly paralleled changes in suppressive potency, and the relative effects of Treg ablation could be largely recapitulated by CTLA-4 in vivo blockade. Together, these results demonstrate that dynamic regulation of Treg suppressive potency dictates the course of persistent bacterial infection.

Introduction

Typhoid fever is a systemic, persistent infection caused by highly adapted host-specific strains of Salmonella [1], [2], [3]. Human typhoid is caused predominantly by S. enterica serotype Typhi [4], while mice develop a typhoid-like disease following S. enterica serotype Typhimurium infection. Interestingly, the early stages of this infection, in both mice and humans, are usually asymptomatic or associated with only mild, non-specific “flu-like” symptoms [4], [5]. This represents a stark contrast to other Gram-negative bacterial pathogens (e.g. Escherichia coli, Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenza) that primarily cause acute infection and immediately trigger robust systemic symptoms after tissue invasion. Thus, the inflammatory response is blunted early after infection with Salmonella strains that cause persistent infection, and this feature likely facilitates long-term pathogen survival [3]. On the other hand, the blunted inflammatory response to systemic Salmonella infection also minimizes immune-mediated damage to host tissues that may outweigh the immediate risk posed by the pathogen itself [6]. Thus, dampening the immune response provides potential advantages to pathogen and host during persistent Salmonella infection.

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) were initially identified as a CD25-expressing subset of CD4+ T cells required for maintaining peripheral immune tolerance to self-antigen. However more recent studies clearly demonstrate their importance extends to controlling the immune response during infection [7], [8], [9], [10]. In this regard, the functional importance of Tregs has been best characterized for pathogens that cause persistent infection. For example, depletion of CD25+CD4+ Tregs is associated with enhanced effector T cell activation and reduced pathogen burden during Leishmania major infection [11]. Similarly, reconstituting T cell-deficient mice with CD25+CD4+ Tregs abrogates enhanced pathogen clearance that occurs after reconstitution with CD25-depleted CD4+ T cells [11], [12]. These complementary experimental approaches initially used to identify the role of CD25+ Tregs in host defense during L. major infection have since been reproduced after infection with numerous other bacterial, viral, and parasitic pathogens [8], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Interestingly, Treg-mediated immune suppression can also play “protective” roles for infections where host injury caused by the immune response outweighs the damage caused by the pathogen itself [13], [16], or when pathogen persistence is required for maintaining protection against secondary infection [11], [19]. Together, these findings suggest Treg-mediated immune suppression can provide both detrimental and protective roles in host defense against infection.

Despite these observations, identifying the functional importance of Tregs during in vivo infection has been limited, in part, by the lack of unique markers that allow their discrimination from other CD4+ T cell subsets. In this regard, the majority of infection studies have experimentally manipulated Tregs based on surrogate markers such as CD25 expression on CD4+ T cells. However, since CD25 expression is also a marker for activated T cells with no suppressive function, identifying Tregs based on CD25 expression does not allow discrimination between these functionally distinct T cell subsets. These limitations have been recently overcome by the identification of Foxp3 as the master regulator for Treg differentiation, and the generation of transgenic mice that allow precise identification or targeted manipulation of Tregs based on Foxp3 expression [20], [21], [22]. These include Foxp3GFP reporter mice that allow ex vivo Foxp3+ Treg isolation by sorting for GFP-expressing cells, and Foxp3DTR transgenic mice that co-express a high affinity diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) with Foxp3 [23], [24]. Intriguingly, the first infection study using Foxp3DTR mice for Treg ablation revealed somewhat paradoxical roles for Foxp3+ Tregs in host defense. Within the first fours days after intravaginal herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) infection, reduced inflammatory cell infiltrate and increased viral burden were found at the site of infection in Treg-ablated compared with Treg-sufficient mice [25]. These effects were not limited to HSV-2, nor were they restricted to the mucosal route of infection as increased pathogen burden associated with Foxp3+ Treg ablation also occurred after parenteral infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) and West Nile virus [25], [26]. Whether these Treg-mediated reductions in pathogen burden are limited to these specific viral pathogens, or represent re-defined roles for Tregs based on their manipulation using Foxp3-specific reagents are currently undefined. Therefore, additional studies using representative mouse models of other human infections and Foxp3-specific reagents for Treg manipulation are required. In this study, the role of Foxp3+ Tregs in controlling immune cell activation and the balance between pathogen proliferation and clearance during the natural progression of persistent bacterial infection was examined after infection with virulent Salmonella.

Results

Persistent Salmonella infection in F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 mice

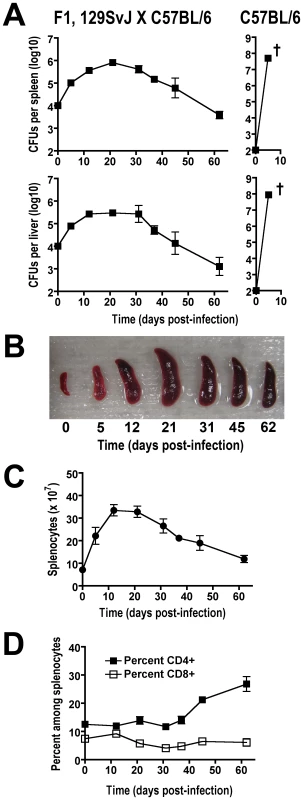

Commonly used inbred mouse strains have discordant levels of innate resistance to virulent S. enterica serotype Typhimurium based primarily on whether a functional allele of Nramp1 is expressed [27], [28]. For example, C57BL/6 mice express a functionally defective, naturally occurring variant of Nramp1 and thus, are inherently susceptible to infection with virulent Salmonella dying within the first few days from uncontrolled bacterial replication. By contrast, 129SvJ mice, which express wild-type Nramp1 (Nramp1-sufficient), are inherently more resistant developing a persistent infection instead [29], [30]. Since transgenic mouse tools for Treg manipulation based on Foxp3-expression are available primarily on the susceptible, Nramp1-defective C57BL/6 background, we sought to exploit the autosomal dominant resistance to Salmonella conferred by wild-type Nramp1, and the X-linked inheritance of Foxp3 transgenic mice by examining infection in resistant F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 mice [30]. Similar to results after infection with virulent Salmonella in 129SvJ mice, progressively increasing bacterial burdens are found throughout the first 3–4 weeks after infection in F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 mice (Figure 1A). By contrast, Nramp1-defective C57BL/6 mice died within the first week after infection from overwhelming bacterial replication despite a 100-fold reduction in Salmonella inocula (Figure 1A). The progressively increasing bacterial burden within the first 3–4 weeks after Salmonella infection in F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 mice parallels dramatic changes in both spleen size and absolute number of splenocytes (Figure 1B and C). Each of these parameters increased within the first three weeks after infection and declined subsequently at later time points that directly coincide with changes in Salmonella bacterial burden (Figure 1A–C). These findings demonstrate an interesting dichotomy in infection tempo between early (first 3–4 weeks) and later time points during persistent Salmonella infection in resistant F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 mice.

Fig. 1. Tempo of persistent Salmonella infection in F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 mice.

A. Recoverable CFUs at the indicated time points after infection from the spleen (top) and liver (bottom) after infection with 104 S. enterica serotype Typhimurium (strain SL1344) in F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 (left) or 102 in C57BL/6 (right) mice. †, all mice died or were moribund. B. Spleen size in F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 mice at the indicated time points after infection. Absolute number of splenocyte cells (C) and percent CD4+ and CD8+ cells (D) in F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 mice at the indicated time points after infection. These data reflect eight to ten mice per time point representative of three independent experiments. Bar, standard error. Delayed T cell activation early after Salmonella infection

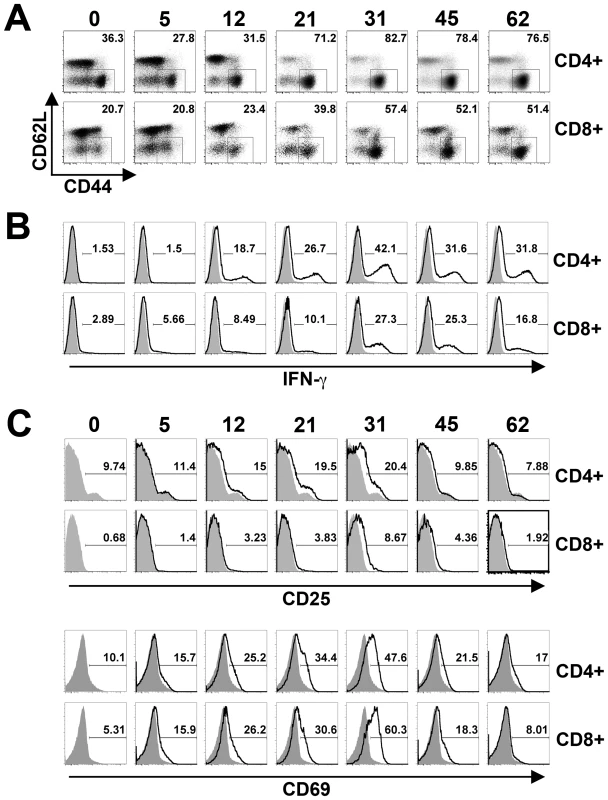

Given the importance of T cells in host defense against Salmonella [31], [32], [33], the expansion and activation kinetics for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells during this persistent infection were each enumerated. Although the absolute numbers of both cell types increased in parallel with the absolute numbers of splenocytes, a progressive and steady increase in percent CD4+ T cells became readily apparent beginning week three post-infection (Figure 1D). By contrast, the percent CD8+ T cells remained essentially unchanged throughout these same time points. Additional phenotypic characterization revealed that the percent activated (CD44hiCD62Llo) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells both increased sharply beginning week 3, and were sustained at high levels through week 7 after infection (Figure 2A). Furthermore, the kinetics of T cell activation based on CD44 and CD62L expression directly paralleled the kinetics whereby CD4+ and CD8+ T cells each became primed for IFN-γ production (Figure 2B). Thus, the kinetics of CD44 and CD62L expression and IFN-γ production each reveal delayed T cell activation early after infection, not peaking until weeks 3 to 4, that is followed by more sustained T cell activation thereafter.

Fig. 2. T cell activation kinetics during persistent Salmonella infection.

A. Percent CD44hiCD62Llo cells among CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at the indicated time points after infection with 104 S. enterica serotype Typhimurium in F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 mice. B. Percent IFN-γ producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells after Salmonella infection and ex vivo stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 antibody (black histogram) or no stimulation control (shaded histogram) at the indicated time points after infection. C. Expression levels of CD25 (top) and CD69 (bottom) by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at the indicated time points post-infection (black histograms) compared to naïve F1 control mice (shaded histograms). These data reflect eight to ten mice per time point representative of three independent experiments. Given the durability whereby T cells maintain changes in CD44 and CD62L expression, and IFN-γ production after activation, the expression of more transient T cell activation markers such as CD25 and CD69 were also quantified throughout persistent Salmonella infection. CD25 and CD69 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells each peaked between weeks 3 and 4 post-infection (Figure 2C). However consistent with the transient nature of their expression, CD25 and CD69 expression each declined to baseline levels over the next 2 to 3 weeks. Thus, the sharp increase in T cell activation that occurs between weeks 3 and 4 after Salmonella infection is confirmed using both transient (CD25, CD69) and more stable (CD44, CD62L, IFN-γ) markers of T cell activation. Interestingly, the overall kinetics for T cell activation beginning week 3 after infection directly parallels when reductions in bacterial burden begins to occur, and suggests dampened T cell activation early after infection allows progressively increasing bacterial burden, while enhanced T cell activation later facilitates bacterial clearance.

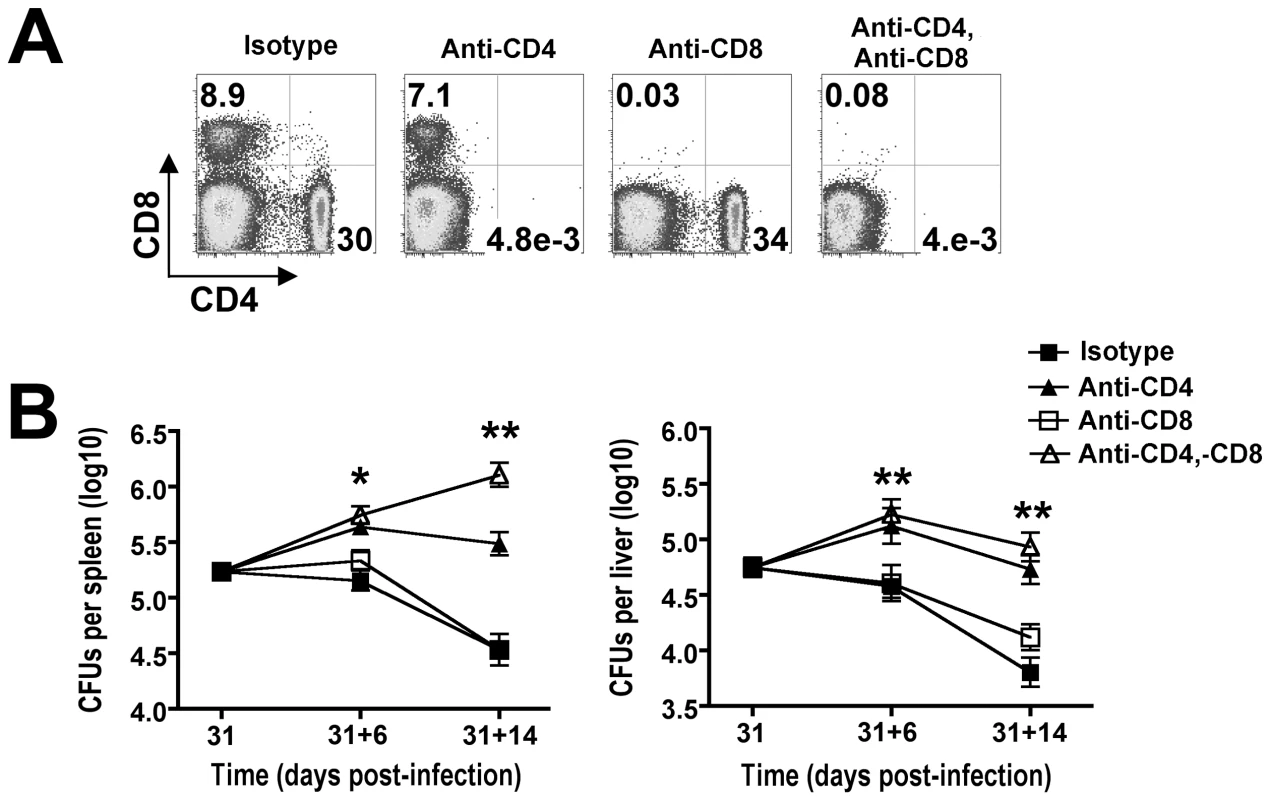

CD4+ T cell-mediated Salmonella clearance during persistent infection

To determine the overall importance and individual contribution provided by each T cell subset in bacterial clearance during the natural course of persistent Salmonella infection, the impacts of CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cell depletion were determined. Anti-mouse CD4 and anti-mouse CD8 depleting antibodies were administered beginning day 31 post-infection. In initial studies, we found that 750 µg of each could deplete the respective T cell subset with ≥99% efficiency even in Salmonella-infected mice that contain expanded T cell numbers (Figure 3A). With sustained CD4+ T cell depletion, significantly increased numbers of recoverable Salmonella CFUs were found day 6 (day 31+6) after the administration of anti-mouse CD4 compared with isotype control antibody (Figure 3B). Moreover, the magnitude of this difference became even more pronounced by day 14 (day 31+14) after antibody treatment. By contrast, CD8+ T cell depletion alone or together with CD4+ T cell depletion did not cause significant changes in Salmonella bacterial burden except in the spleen day 14 after antibody treatment where combined depletion of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells resulted in increased numbers of recoverable Salmonella CFUs compared to CD4+ T cell depletion alone (Figure 3B). Together, these results demonstrate an essential role for CD4+ T cells in the clearance of persistent Salmonella infection, and these findings are consistent with the previously reported requirement for this T cell subset in controlling the replication of attenuated Salmonella in susceptible Nramp1-defective mice [31]. Moreover, an essential role for CD4+ T cells in host defense during persistent infection in resistant mice is further supported by the sharp increase in overall percentage and activation of these cells which coincides with reductions in Salmonella bacterial burden beginning week 3 post-infection (Figure 1 and 2).

Fig. 3. CD4+ T cells are required for reductions in Salmonella pathogen burden during persistent infection.

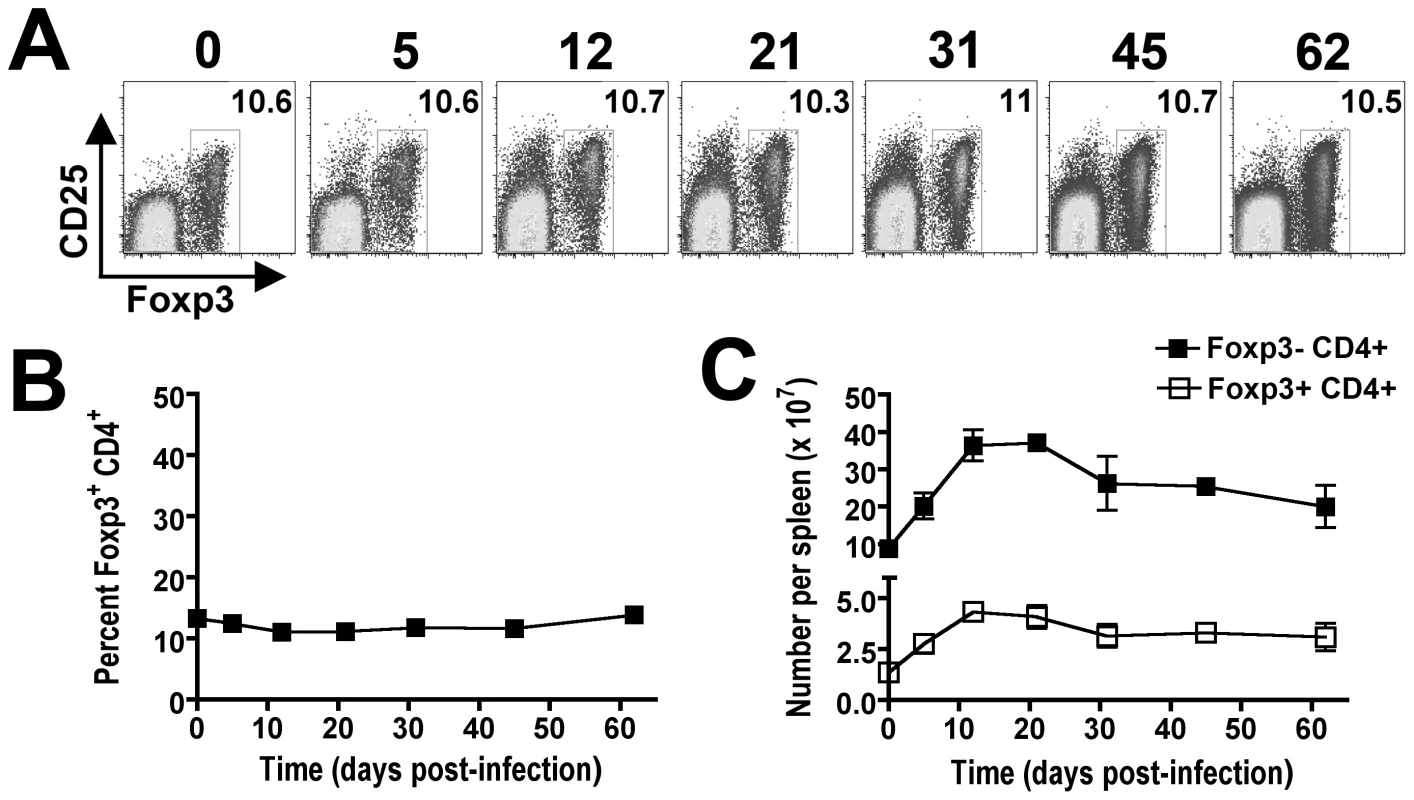

A. Percent CD4+ and CD8+ T cells 14 days after treatment with each indicated antibody in mice beginning day 31 after Salmonella infection. B. Recoverable Salmonella CFUs in the spleen (left) and liver (right) for mice treated with each antibody for six days (31+6) or 14 days (31+14). These data reflect six to twelve mice per time point representative of three independent experiments each with similar results. Bar, standard error. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.001. Parallel expansion of Foxp3+ Tregs and non-Treg CD4+ cells during persistent infection

The requirement for CD4+ T cells in bacterial clearance during persistent Salmonella infection may reflect contributions from either Foxp3-negative effector or Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs). To characterize the relative contributions of each CD4+ T cell subset during persistent infection, our initial studies enumerated the percent Foxp3+ cells among CD4+ T cells and the expansion kinetics of Foxp3+ and Foxp3-negative CD4+ T cells during persistent infection. Interestingly despite dramatic shifts in the percent and absolute number of CD4+ T cells among splenocytes, the percent Foxp3+ Tregs among CD4+ T cells remains remarkably stable and essentially unchanged at approximately 10% throughout the infection (Figure 4A and B). By extension, the absolute numbers of Foxp3+ Tregs and Foxp3-negative effector CD4+ T cells were also found to expand in parallel (Figure 4C). These findings suggest variations in the ratio of Foxp3+ Tregs among non-Treg effector CD4+ T cells alone does not account for the shift in relative T cell activation and change in infection tempo at early compared to late time points during persistent Salmonella infection.

Fig. 4. Parallel expansion of Foxp3+ and Foxp3-negative CD4+ T cells during persistent Salmonella infection.

Representative FACS plots (A) and composite data (B) indicating percent Foxp3+ cells among CD4+ T cells at the indicated time points after infection with 104 Salmonella in F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 mice. C. Total numbers of Foxp3+CD4+ Tregs and Foxp3-negative non-Treg CD4+ T cells among splenocytes during persistent infection. These data reflect six to eight mice per time point representative of three independent experiments each with similar results. Bar, standard error. Dynamic shifts in Foxp3+ Treg suppressive potency

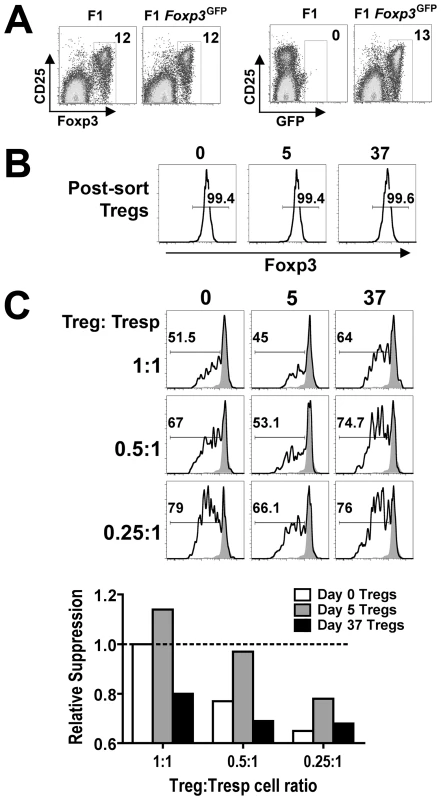

Since defined inflammatory cytokines and pathogen associated molecular patterns have each been shown to control Treg suppressive potency after stimulation in vitro [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], we explored the possibility that intact pathogens and the ensuing immune response would also dictate shifts in Treg suppressive potency after infection in vivo. By extension, these shifts in relative Treg suppressive potency may impact the activation of non-Treg effector cells and overall tempo of persistent infection. Accordingly, we compared the suppressive potency for Foxp3+ Tregs isolated at early (day 5) and late (day 37) time points during persistent Salmonella infection. These specific time points where chosen because they reflect highly pronounced contrasts in T cell activation and directional changes in Salmonella bacterial burden, yet have comparable bacterial burdens (Figure 1 and 2). Nramp1-sufficient F1 Foxp3GFP reporter hemizygous male mice derived by intercrossing 129SvJ males with Foxp3GFP/GFP females (on the C57BL/6 background) that simultaneously allow persistent Salmonella infection and for all Tregs to be isolated based on cell sorting for GFP+(Foxp3+) cells were used in these experiments [23] (Figure 5A). By first enriching for CD4+ cells using negative selection, GFP+(Foxp3+) Tregs could be routinely isolated from naïve and Salmonella-infected F1 Foxp3GFP reporter mice each with ≥99% purity (Figure 5B). Potential differences in suppressive potency for GFP+(Foxp3+) Tregs isolated at each time point after infection were quantified by measuring their ability to inhibit the proliferation of responder CD4+ T cells isolated from naïve CD45.1 congenic mice after non-specific stimulation in vitro using previously defined methods [40], [41], [42].

Fig. 5. Dynamic regulation of Treg suppressive potency during persistent Salmonella infection.

A. Percent Foxp3+ (left) and GFP+ (right) cells among CD4+ T cells from F1 and F1 Foxp3GFP/− mice. B. Expression of Foxp3+ after cell sorting for GFP+CD4+ cells from F1 Foxp3GFP/− mice at the indicated time points after infection. C. Percent CFSElo cells among CD45.1+CD4+ responder T cells (Tresp) after co-culture with the indicated ratio of GFP+(Foxp3+) Tregs isolated from mice at each time point after infection and stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 (line histogram) or no stimulation (shaded histogram) (top). Relative suppression of CFSE dilution in CD45.1+CD4+ responder T cells by GFP+(Foxp3+) Tregs isolated at each time point after infection normalized to the suppression conferred by Tregs from naïve mice co-cultured with responder T cells at a 1∶1 ratio (dotted line) (bottom). These data are representative of three independent experiments each with similar results. Compared with Tregs isolated from F1 Foxp3GFP reporter mice prior to infection, the suppressive potency of Tregs isolated from mice day 5 after Salmonella infection was enhanced (Figure 5C). At the same Treg to responder T cell ratio, Foxp3+ Tregs from mice day 5 after infection consistently inhibited responder CD45.1+ T cell proliferation (CFSE dilution) more efficiently. These differences in suppression were eliminated when a 2-fold reduction in Treg to responder cell ratio from mice day 5 post-infection compared with undiluted Tregs from naïve mice were co-cultured with a fixed number of naïve responder cells (Figure 5C). In sharp contrast to increased suppression that occurs at this early post-infection time point, the suppressive potency for Tregs isolated from mice day 37 after infection was significantly reduced. Compared with Tregs isolated from mice 5 days after infection, the efficiency whereby Tregs isolated day 37 post-infection inhibited the proliferation of responder CD45.1+ T cells was reduced approximately 4-fold; and compared with Tregs isolated from naïve mice, their suppressive potency was reduced approximately 2-fold (Figure 5C). In other words, a 50% reduction in Treg to responder cell ratio for Tregs isolated from naïve mice, and a 75% reduction in ratio for Tregs from mice day 5 after infection each suppressed responder cell proliferation to the same extent as undiluted GFP+(Foxp3+) Tregs isolated from mice day 37 after infection. These results demonstrate that although the ratio of Foxp3+ Tregs and non-Treg effector CD4+ T cells remains unchanged, shifts in Treg suppressive potency that directly parallel the kinetics of T cell activation and infection tempo occur during the progression of persistent Salmonella infection.

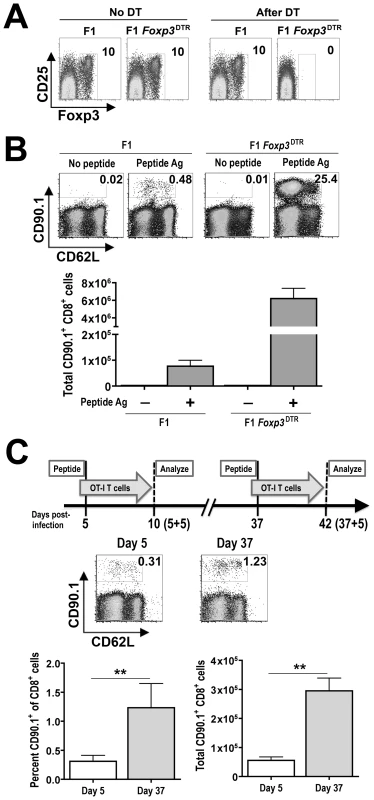

In complementary experiments, the relative suppressive environment dictated by Foxp3+ Tregs during Salmonella infection was further characterized. Specifically the expansion of adoptively transferred antigen-specific T cells after stimulation with cognate peptide at defined time points during persistent infection was enumerated. This approach exploits the use of F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 mice as recipients for adoptively transferred T cells from TCR transgenic mice on the C57BL/6 background [43]. As a control to identify the overall contribution of Tregs in suppressing the expansion of adoptively transferred T cells in vivo, F1 Foxp3DTR hemizygous male mice derived from intercrossing 129SvJ males with Foxp3DTR/DTR female mice (on the C57BL/6 background), which allows targeted ablation of Foxp3+ Tregs by administering low-dose diphtheria toxin (DT) were used initially [24]. We found 1.0 µg (50 µg/kg) DT given on two consecutive days was sufficient for ≥99% ablation of Foxp3+ Tregs, and continued DT dosing (0.2 µg every other day) was able to maintain this level of Treg ablation in Foxp3DTR mice on the F1 background (Figure 6A). These results are consistent with the reported efficiency whereby Foxp3+ Tregs are selectively ablated in Foxp3DTR mice on the C57BL/6 background [24]. Although in vivo injection of cognate OVA257–264 peptide could stimulate only modest levels of expansion for adoptively transferred T cells from OT-1 TCR transgenic mice in Treg-sufficient mice, the expansion magnitude was increased >50-fold in Treg-ablated F1 Foxp3DTR mice (Figure 6B). Importantly, the expansion of these adoptively transferred T cells was antigen-dependent because very few cells could be recovered from either Treg-ablated or Treg-sufficient recipient mice without peptide stimulation. Thus, Tregs actively suppress the expansion of peptide stimulated antigen-specific T cells in vivo, and the relative expansion of these exogenous cells is a reflection of Treg suppressive potency.

Fig. 6. Shifts in Treg-mediated in vivo suppression during persistent Salmonella infection.

A. Representative FACS plots demonstrating the efficiency whereby Foxp3+ Tregs are ablated with DT treatment in F1 Foxp3DTR compared with F1 Foxp3WT (F1) control mice. The numbers indicate the percent Foxp3-expressing among CD4+ T cells after DT treatment. B. Representative FACS plots demonstrating percent (top) CD90.1+ OT-1 T cells among CD8+ splenocytes and total number (bottom) of CD90.1+CD8+ splenocytes in Treg-sufficient (F1) or Treg-ablated (F1 Foxp3DTR) mice day 5 after injection of OVA257–264 peptide or no peptide controls. C. Representative FACS plots (top) demonstrating percent CD90.1+ OT-I T cells among CD8+ splenocytes and composite data (bottom) depicting percent and total number CD90.1+CD8+ splenocytes after adoptive transfer into mice at the indicated time points after Salmonella infection and peptide stimulation. These data represent six to ten mice per group combined from three independent experiments each with similar results. Bar, standard error. **, p<0.01. Using this approach, the relative expansion of exogenous T cells from OT-1 TCR transgenic mice after adoptive transfer into Salmonella infected F1 129SvJ X C57BL/6 and stimulation with cognate OVA257–264 peptide was enumerated. The percent and total numbers of OT-1 T cells was increased 4-fold and 5-fold, respectively, after adoptive transfer into mice at late (day 37) compared with early (day 5) time points during persistent infection (Figure 6C). Thus, the in vivo environment at later compared with early time points during persistent Salmonella infection is significantly more permissive for peptide-stimulated T cell expansion. These results, together with the reductions in suppressive potency for GFP+(Foxp3+) cells isolated ex vivo from mice at early compared with late time points (Figure 5C), and the critical role for Foxp3+ Tregs in controlling exogenous T cell expansion in response to cognate peptide (Figure 6A and B) clearly illustrate reductions in Treg suppressive potency occur from early to late points during persistent Salmonella infection. Furthermore, given the sharp dichotomy in infection tempo at these specific time points, these results suggest enhanced Treg suppression early after infection restrains effector T cell activation that allows progressively increasing Salmonella bacterial burden, while diminished Treg suppression at later time points allows enhanced T cell activation that more efficiently controls the infection.

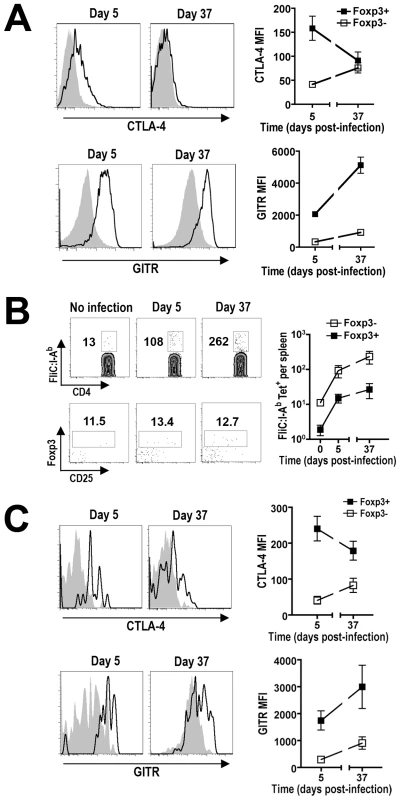

Dynamic regulation of Treg-associated molecules that control suppression

Multiple Treg-associated cell surface and secreted molecules have been implicated to mediate immune suppression by these cells. For example, increased expression of CTLA-4, IL-10, Tgf-β, Granzyme B, ICOS, PD-1, and CD39 each have been shown independently to coincide with enhanced Treg suppressive potency [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], while expression of other Treg cell-intrinsic molecules (e.g. GITR, OX40) each parallel reductions in suppressive potency [54], [55], [56]. Although the relative importance of each defined molecule varies significantly depending upon the experimental model used, the relative expression of Treg cell-intrinsic signals that either stimulate or inhibit suppression likely dictates the overall suppressive potency of Tregs. Therefore, we quantified the relative expression of each molecule on Foxp3+ Tregs to explore how the observed shifts in suppression potency from early to late time points during persistent Salmonella infection correlate with changes in their expression (Figure 7A and Figure S1). Consistent with the drastic reduction in suppressive potency, significant shifts in expression for some Treg-associated molecules between day 5 and day 37 post-infection were identified. For example, molecules that have independently been associated with diminished Treg suppression potency such as reduced CTLA-4 and increased GITR expression were found for Foxp3+ Tregs from mice day 5 compared with day 37 after infection [46], [54], [55] (Figure 7A). By contrast, more modest or minimal changes were found for other Treg-associated molecules implicated to mediate suppression (e.g. CD39, IL-10, Granzyme B, PD-1, and Tgf-β) [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [56] (Figure S1). Thus, reduction in Treg suppressive potency during the progression of persistent Salmonella infection directly parallels reduced CTLA-4 and increased GITR expression that each independently correlates with this shift in suppression.

Fig. 7. Expression of Treg-associated effector molecules during persistent Salmonella infection.

A. The relative expression of CTLA-4 and GITR on Foxp3+ Tregs (line histogram) or Foxp3-negative CD4+ T cells (shaded histogram) at the indicated time points during persistent infection. B. Expansion of Salmonella FliC431–439-specific CD4+ T cells, and Foxp3-expression among these cells after staining with FliC:I-Ab tetramer and magnetic bead enrichment. The numbers in each plot represent the average cell number and percent Foxp3+ cells from 12 mice per time point combined from four independent experiments. C. Expression of CTLA-4 or GITR on FliC431–439-specific Foxp3+ Tregs (line histogram) and Foxp3-negative CD4+ T cells (shaded histogram) at early (day 5) and late (day 37) time points during persistent Salmonella infection. These data reflect six mice per time point representative of two independent experiments each with similar results. Bar, standard error. Salmonella FliC-specific CD4+ T cells expand during persistent infection

Given the importance of pathogen-specific Tregs in controlling pathogen-specific effector cells in other models of persistent infection [57], [58], [59], the expansion kinetics and relative expression of Treg-associated effector molecules were also characterized for Salmonella-specific Tregs. The best characterized Salmonella-specific, I-Ab-restricted MHC class II antigen is the flagellin FliC431–439 peptide [60]. Using tetramers with specificity for this antigen and magnetic bead enrichment, naïve C57BL/6 mice have been estimated to contain ∼20 FliC431–439-specific CD4+ T cells [61]. Using these same techniques, we find similar numbers of FliC431–439-specific CD4+ T cells in naïve F1 mice prior to Salmonella infection (Figure 7B). As predicted after Salmonella infection, the numbers of these FliC431–439-specific CD4+ T cells expand reaching ∼10-fold and 20-fold increased cell numbers day 5 and 37 post-infection, respectively (Figure 7B). Interestingly, for FliC431–439-specific CD4+ cells identified in this manner, ∼10% were Foxp3+ in F1 mice prior to and at each time point after infection (Figure 7B). Thus, FliC431–439-specific Tregs and effector T cells expand in parallel during this persistent infection, and these results are consistent with the stable percentage of Foxp3+ Tregs among bulk CD4+ T cells (Figure 4). Although the relatively small number (∼1–2 cells per mouse) of FliC431–439-specific Foxp3+ Tregs in naïve mice precluded further analysis beyond these absolute cell numbers, the expansion of FliC431–439-specific Tregs and non-Treg effector CD4+ T cells at early and late time points after infection allowed the relative expression of likely determinants of Treg suppression to be characterized. FliC431–439-specific Tregs were found to down-regulate CTLA-4 and up-regulate GITR expression, as infection progressed from early to late time points to a similar extent in FliC431–439-specific compared with bulk Tregs at these same time points after infection (Figure 7A and C). Thus, the relative expression of Treg-intrinsic molecules known to stimulate or impede immune suppression occurs for both pathogen-specific and bulk Foxp3+ Treg cells, and these changes directly coincide with reductions in their suppressive potency that occurs from early to late time points during persistent infection.

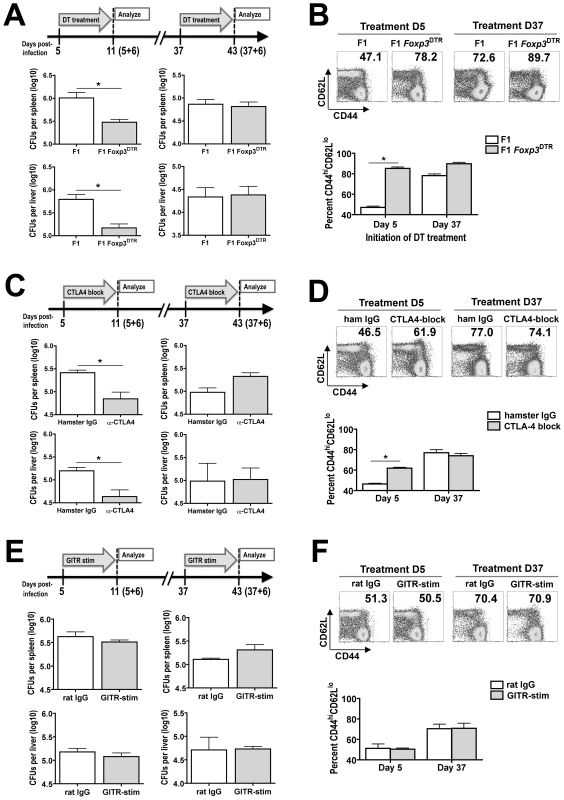

Reduced impact of Treg-ablation from early to late time points during persistent infection

To more definitively identify the relative importance of Treg-mediated immune suppression on the progression of persistent Salmonella infection, the impacts of Treg ablation on infection tempo and T cell activation were enumerated at early and late time points after infection. Given the striking contrasts in suppressive potency for Foxp3+ Tregs, directional changes in bacterial burden, and effector T cell activation between mice day 5 versus day 37 post-infection, the relative impact caused by Treg ablation using F1 Foxp3DTR mice (Figure 6A) on infection tempo beginning at these time points were enumerated. In agreement with their essential role in maintaining and sustaining peripheral tolerance [24], Treg-ablated mice began to appear lethargic and dehydrated beginning day 8 after the initiation of DT treatment in Salmonella-infected mice. Thus, the impacts of Treg ablation on infection tempo and T cell activation were limited to discrete 7-day windows during persistent Salmonella infection. For mice that received DT beginning day 5 post-infection, significantly reduced numbers of recoverable Salmonella CFUs were found for Treg-ablated F1 Foxp3DTR compared with Treg-sufficient F1 Foxp3WT control mice 6 days after the initiation of DT treatment (day 5+6) (Figure 8A). These reductions in bacterial burden with Treg ablation early after infection were paralleled by significantly increased T cell activation (percent CD44hiCD62lo T cells) (Figure 8B). Importantly, the reductions in Salmonella bacterial burden in Treg-ablated mice cannot be attributed to non-specific effects related to DT treatment because both Treg-ablated F1 Foxp3DTR and Treg-sufficient F1 Foxp3WT control mice each received identical doses of this reagent, nor could they be attributed to cell death-induced inflammation triggered by dying Tregs because no significant reductions in recoverable CFUs were found for F1 Foxp3DTR/WT heterozygous female mice where ∼50% Tregs express the high affinity DT receptor and are eliminated following DT treatment (Figure S2). By contrast, Treg ablation beginning later after infection (day 37) when T cells are already highly activated caused no significant change in Salmonella bacterial burden and only a modest incremental increase in T cell activation between Treg-ablated F1 Foxp3DTR compared with Treg-sufficient F1 Foxp3WT control mice (Figure 8A and B). Thus, the relative impact of Treg ablation at early and late time points on infection outcome directly parallel the differences in their suppressive potency. Together, these results demonstrate enhanced Treg suppressive potency at early infection time points restrains effector T cell activation and allows progressively increasing bacterial burden. By extension, Treg ablation at these early time points markedly increases T cell activation and significantly reduces the bacterial burden (Figure 8A and B). Reciprocally, at later time points after infection when Treg suppressive potency is diminished, the relative contribution of Foxp3+ Tregs on T cell activation and bacterial clearance is reduced (Figure 8A and B). Thus, dynamic regulation of Treg suppression dictates the balance between pathogen proliferation and clearance during the course of persistent Salmonella infection.

Fig. 8. Relative impacts after Treg ablation on the tempo of persistent Salmonella infection.

A. Number of recoverable Salmonella CFUs from spleen (top) and liver (bottom) in Treg-ablated F1 Foxp3DTR compared with Treg-sufficient F1 control mice when DT treatment was initiated at either early (day 5) or late (day 37) time points during persistent infection. B. Percent CD44hiCD62Llo among CD4+ T cells in Treg-ablated F1 Foxp3DTR compared with Treg-sufficient F1 control mice when DT treatment was initiated on either day 5 or day 37 during persistent infection. C. Number of recoverable Salmonella CFUs from spleen (top) and liver (bottom) following CTLA-4 blockade beginning at either early (day 5) or late (day 37) time points post-infection in F1 mice. D. Percent CD44hiCD62Llo among CD4+ T cells when CTLA-4 blockade was initiated at either early (day 5) or late (day 37) time points post-infection. E. Number of recoverable Salmonella CFUs from spleen (top) and liver (bottom) following treatment with GITR-stimulating antibody beginning at either early (day 5) or late (day 37) time points post-infection in F1 mice. F. Percent CD44hiCD62Llo among CD4+ T cells when GITR stimulation was initiated at either early (day 5) or late (day 37) time points post-infection. These data reflect six to ten mice per group combined from two to three independent experiments each with similar results. Bar, standard error. *, p<0.05. Given the drastic shifts in Treg-associated expression of CTLA-4 and GITR that each correlates with the reduced suppressive potency of these cells from early to late time points during persistent Salmonella infection, additional experiments sought to identify the relative importance of these molecules in dictating infection tempo using well characterized CTLA-4 blocking (clone UC10-4F10) or GITR-stimulating (clone DTA-1) monoclonal antibodies [54], [62], [63], [64]. Consistent with the essential role for CTLA-4 in Treg suppression during non-infection conditions in vivo [46], significant reductions in Salmonella recoverable CFUs and accelerated T cell activation were found with CTLA-4 blockade initiated beginning day 5 after Salmonella infection, and the magnitude of these changes paralleled those following DT-induced Treg ablation in F1 Foxp3DTR mice (Figure 8C and D). Since Foxp3-negative cells also express CTLA-4, albeit at significantly reduced levels compared with Foxp3+ Tregs (Figure 7), we further explored the relative contribution of CTLA-4 blockade in the absence of Foxp3+ Tregs. Consistent with the reduced levels of CTLA-4 expression on Foxp3-negative CD4+ T cells, the effects of CTLA-4 blockade were eliminated with Foxp3+ Treg ablation (Figure S3). By extension, at later time points after infection (day 37) when CTLA-4 expression is down-regulated on Foxp3+ Tregs, no significant change in Salmonella bacterial burden or T cell activation occurred with CTLA-4 blockade (Figure 8C and D). By contrast to these results with CTLA-4 blockade that directly recapitulates the effects of Treg ablation at early and late time points during persistent infection, treatment with a monoclonal antibody that stimulates cells through GITR caused no significant changes in Salmonella bacterial burden or T cell activation when initiated at either early or late time points during persistent infection (Figure 8E and F). Together, these results suggest the dynamic regulation of Treg suppressive potency during Salmonella infection is predominantly mediated by shifts in CTLA-4 expression, and reduced CTLA-4 expression by Tregs during the progression of this persistent infection dictates reduced suppression with enhanced effector T cell activation and bacterial clearance.

Discussion

The balance between immune activation required for host defense, and immune suppression that limits immune-mediated host injury is stringently regulated during persistent infection [6], [7]. Although Tregs have been widely implicated to control the activation of immune host defense components during infection, their role in dictating the natural progression of persistent infection remains undefined. In this study, we report two distinct phases of effector T cell activation with opposing directional changes in pathogen burden in a mouse model of persistent Salmonella infection. Delayed T cell activation associated with increasing bacterial burden occurs early, while enhanced T cell activation that parallels reductions in pathogen burden occurs later during infection. Remarkably, significant reductions in Treg suppressive potency between early and late infection time points directly coincide with these differences in infection tempo. In complementary experiments, the significance of these shifts in Treg suppressive potency were verified by directly enumerating the relative impact of Treg ablation on infection tempo at early and late infection time points. Together, these results demonstrate dynamic changes in Foxp3+ Treg suppressive potency dictate the natural course and progression of this persistent infection.

Along with two recent studies characterizing infection outcome with Foxp3+ Treg ablation after mucosal HSV-2, systemic LCMV, and footpad West Nile virus infections [25], [26], these are the first studies to characterize the importance of Tregs during infection using Foxp3DTR transgenic mice. These results comparing infection outcome after Treg manipulation based on their lineage-defining marker, Foxp3, allow the importance of Tregs to be more precisely characterized compared with other methods that identify and manipulate Tregs using surrogate markers (e.g. CD25 expression) that are not expressed exclusively by these cells. Interestingly, while Treg ablation caused increased pathogen burden, delayed arrival of acute inflammatory cells, and accelerated mortality after HSV-2, LCMV, or West Nile virus infections [25], [26], we find contrasting reductions in pathogen burden and increased T cell activation with Treg ablation at early, but not late time points during persistent Salmonella infection. However, the reductions in Salmonella pathogen burden with early Treg ablation are consistent with reduced Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogen burden after partial Treg depletion using bone marrow chimera mice reconstituted with mixed cells containing congenically-marked Foxp3+ Tregs and Foxp3-deficient cells [65]. Together, these studies comparing infection outcome after Treg ablation using Foxp3-specific reagents highlight interesting and divergent functional roles for Foxp3+ Tregs during specific infections. The reasons that account for these differences – whether they are related to differences between bacterial versus viral pathogens or between pathogens that primarily cause acute versus persistent infection, are important areas for additional investigation, and require the characterization of infection outcomes after Treg manipulation using Foxp3-specific reagents with other pathogens.

The dynamic regulation of Treg suppressive potency during Salmonella infection we demonstrate here is consistent with the ability of inflammatory cytokines and purified Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands to each control Treg suppression after stimulation in vitro [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]. However, since these stimulation signals in isolation trigger opposing directional changes in suppressive potency, the specific contribution for each on changes in Treg suppression during infection is unclear. Therefore, the cumulative impact of multiple TLR ligands expressed by intact pathogens and the ensuing immune response on changes in Treg suppression is best characterized for Tregs isolated directly ex vivo after infection. The increased suppressive potency for Foxp3+ Treg at early time points after Salmonella infection we demonstrate here is consistent with the increased suppressive potency for CD25+CD4+ cells isolated day 5 after Plasmodium yoelii and day 10 after HSV-1 infection, as well as CD25+CD4+ cells isolated in the acute (day 12) and chronic phase (day 28) after Heligmosomoides polygyrus infection [14], [66], [67]. However, our results build upon and extend the significance of these findings in three important respects. First, by isolating Tregs based on Foxp3 rather than CD25 expression, the limitations imposed by contaminating non-Treg CD25+ effector T cells in subsequent ex vivo functional analysis is bypassed.

Secondly, although an increase in CD25+CD4+ T cell suppression early after infection when pathogen proliferation occurs, potential shifts in Treg suppression at later time points during the natural progression of persistent infections has not been previously demonstrated. In this regard, the relatively short time interval that separates pathogen proliferation and clearance during persistent Salmonella infection is ideally suited for comparing differences in relative importance and suppressive potency for Tregs during these contrasting stages of infection. Using this model, we demonstrate significant reductions in Treg suppressive potency between early and late time points after infection that enables robust immune cell activation required for pathogen clearance. Despite these changes in suppressive potency, the percentage of Tregs among bulk and Salmonella FliC-specific CD4+ T cells each remained relatively constant throughout infection. These findings are consistent with the stable ratio of Tregs to effector CD4+ T cells during other models of persistent infection, and represent a striking contrast to the selective priming and expansion of pathogen-specific Foxp3-negative CD4+ T cells that occurs after acute Listeria monocytogenes infection [58], [65], [68], [69]. Thus, the priming and expansion of pathogen-specific Tregs may be an important distinguishing feature between pathogens that cause acute rather than persistent infection.

The development and refinement of methods for MHC class II tetramer staining and magnetic bead enrichment has allowed the precise identification of very small numbers of T cells with defined specificity from naïve mice [61]. Using these techniques, we find in this and a recent study [69] that Foxp3+ Tregs comprise approximately 10% of CD4+ T cells with specificity to both the FliC431–439 and 2W1S52–68 peptide antigens, respectively. Together, these results suggest previously under-appreciated overlap in the repertoire of antigens recognized by Foxp3+ Tregs compared with non-Treg CD4+ effectors in naïve mice [70], [71], [72]. However, more considerable overlap in the specificity of these two cell types is consistent with the TCR repertoires of human peripheral Tregs and non-Tregs based on genomic analysis of TCR sequences [73], [74]. Thus, additional studies that examine the percent Tregs among CD4+ T cells with other defined antigen-specificities using recently developed tetramer-based enrichment techniques are warranted.

Lastly, by enumerating the relative expression of defined Treg-associated molecules that have been implicated to directly mediate or inhibit suppression, the complexity whereby Tregs maintain the balance between immune activation and suppression becomes more clearly defined. For example, shifts in suppressive potency for Tregs isolated from early compared to late time points during persistent infection are paralleled by significant changes in the expression of numerous Treg cell-intrinsic molecules that have been demonstrated in other experimental models to control and/or mediate suppression [44], [45] (Figure 7 and Figure S1). In particular, the drastic reductions in suppressive potency that occurs for Tregs isolated from mice day 5 compared with day 37 after infection is associated with significant reductions in CTLA-4 expression and increased expression of GITR on both bulk Foxp3+ Tregs and Salmonella FliC431–439-specific Foxp3+ Tregs (Figure 7). Based on these results, the relative contributions of CTLA-4 and GITR in controlling suppression by Foxp3+ Tregs during persistent infection were investigated using antibody reagents that block CTLA-4 or stimulate cells through GITR. We find that CTLA-4 blockade alone is sufficient to recapitulate the effects of Treg ablation on Salmonella infection tempo, while GITR stimulation had no significant effect (Figure 8). These results are consistent with the recent demonstration that CTLA-4 expression on Foxp3+ Tregs is essential for maintaining peripheral tolerance [46], [75]. Our results expand upon these findings by demonstrating the importance of dynamic CTLA-4 expression on Tregs during persistent infection that controls the kinetics of effector T cell activation and overall infection tempo.

The increase in Treg suppressive potency at early time points after Salmonella infection is consistent and may provide the mechanistic basis that explains the relative immune suppression previously observed during this infection [76], [77], [78], [79], [80]. Interestingly, increased Treg suppressive potency early after infection has also been described after viral and parasitic pathogens [14], [66], [67]. Is enhanced Treg suppression early after infection advantageous for the host, the pathogen, or both? Our ongoing studies are aimed at identifying the signals activated during Salmonella infection that trigger these changes, and Treg-intrinsic molecules that sense and dictate this augmentation in suppressive potency. Perhaps more intriguing are the molecular signals during natural infection that trigger reductions in Treg suppression that transform blunted immune effectors early after infection into more potent mediators of pathogen clearance. Given the multiple known pathogen-associated molecular patterns expressed by Salmonella (e.g. LPS, flagellin, porins, and CpG DNA) that each stimulate immune cells through defined Toll-like and other pattern recognition receptors [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], together with the enormous potential for cell intrinsic TLR-stimulation on Tregs to alter their suppressive potency [34], [35], [36], [38], [87], it is tempting to hypothesize that shifts in the expression of individual, multiple, or cumulative TLR ligands during persistent infection controls the relative expression of Treg-associated molecules that mediate suppression. In this regard, our ongoing studies are also aimed at identifying the Salmonella-specific ligands and their corresponding host receptors that dictate these reductions in Treg suppression during the progression of this persistent infection. We believe these represent important prerequisites for developing new therapeutic intervention strategies aimed at accelerating the transition to pathogen clearance and further unraveling the pathogenesis of typhoid fever caused by Salmonella infection.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

These experiments were conducted under University of Minnesota IACUC approved protocols (0705A08702 and 1004A80134) entitled “Regulatory T cells dictate immunity during persistent Salmonella infection”. The guidelines followed for use of vertebrate animals were also created by the University of Minnesota IACUC.

Mice

129SvJ males and C57BL/6 females were purchased from the National Cancer Institute. F1 mice were generated by intercrossing 129SvJ males with C57BL/6 females. F1 Foxp3GFP/− and F1 Foxp3DTR/− hemizygous males and F1 Foxp3DTR/WT heterozygous females were derived by intercrossing 129SvJ males with Foxp3GFP/GFP or Foxp3DTR/DTR females, respectively [23], [24]. Both Foxp3GFP/GFP and Foxp3DTR/DTR females have been backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice for over 15 generations. OT-1 TCR transgenic mice that contain T cells specific for the OVA257–264 peptide were maintained on a RAG-deficient CD90.1+ background. All mice were used between 6–8 weeks of age and maintained within specific pathogen-free facilities.

Bacteria

The virulent Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium strain SL1344 has been described [29], [88]. For infections, SL1344 was grown to log phase in brain heart infusion media at 37°C, washed and diluted with saline to a final concentration of 1×104 CFUs (for infection in F1 mice) or 1×102 CFUs (for infection in C57BL/6 mice) per 200 µL, and injected intravenously through the lateral tail vein. At the indicated time points after infection, mice were euthanized and the number of recoverable Salmonella CFUs enumerated by plating serial dilutions of the spleen and liver organ homogenate onto agar plates.

Reagents

Antibodies and other reagents for cell surface, intracellular, or intranuclear staining were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) or eBioscience (San Diego, CA), and used according to the manufacturers' recommendations. For measuring cytokine production by T cells, splenocytes were stimulated ex vivo with anti-mouse CD3 and anti-mouse CD28 (each at 5 µg/mL) in the presence of brefeldin A for 5 hours prior to intracellular cytokine staining. Antibodies used for depletion, blocking or stimulation experiments were purchased from BioXcell (West Lebanon, NH). For T cell depletions, purified anti-mouse CD4 (clone GK1.5) and anti-mouse CD8 (clone 2.43) antibodies were diluted to a final concentration of 750 µg per 1 mL in sterile saline and injected intraperitoneally on days 31 and 34 post-infection. Additional injections were given on days 38 and 41 post-infection in experiments where depletion was maintained up to 14 days. For CTLA-4 blockade and GITR stimulation, anti-mouse CTLA4 (clone UC10-4F10), anti-mouse GITR (clone DTA-1), or isotype control antibodies (hamster IgG or rat IgG, respectively) were diluted to a final concentration of 500 µg per 1 mL in sterile saline and injected intraperitoneally beginning either day 5 or day 37 post-infection followed by an additional injection of 250 µg of the same antibody three days later [54], [62], [63], [64]. For Foxp3+ Treg ablation, purified diphtheria toxin (DT; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in saline and administered intraperitoneally to F1 Foxp3WT control, F1 Foxp3DTR/−, or F1 Foxp3DTR/WT mice at 50 µg/kg body weight for two consecutive days beginning at indicated time point after infection, and then maintained on a reduced dose of DT thereafter (10 µg/kg body weight every other day).

In vitro and in vivo suppression assays

For enumerating relative Treg suppression in vitro, Foxp3+GFP+ Tregs were isolated from F1 Foxp3GFP/− mice by enriching CD4+ splenocytes first with negative selection using magnetic bead cell isolation kits (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). GFP+(Foxp3+) Tregs were further purified by staining and sorting for CD4+GFP+ cells using a FACSAria cell sorter. The purity of CD4+Foxp3+ cells post-sort was verified to be >99%. Responder CD4+ T cells were isolated from naïve CD45.1+ mice, CFSE-labeled under standard conditions (5 µM for 10 min), and co-cultured in 96-well round bottom plates (2×104 cells/100 µL) at the indicated ratio of purified GFP+(Foxp3+) Tregs and responder CD45.1+CD4+ T cells. The relative suppressive potency for Tregs was enumerated by comparing the proliferation (CFSE dilution) in responder cells after co-culture and stimulation with anti-mouse CD3 and anti-mouse CD28 antibodies (1 µg/mL each) for 4 days. For enumerating relative Treg suppression in vivo, 2×104 T cells from OT-1 TCR transgenic mice on a RAG CD90.1+ background were diluted in 200 µL sterile saline and injected intravenously at the indicated time points relative to Treg ablation or Salmonella infection followed by intravenous injection of purified OVA257–264 peptide (400 µg) the following day. For each experiment, the degree of OT-1 T cell expansion was enumerated five days later.

MHC tetramer staining and enrichment

MHC class II tetramer staining and enrichment were performed as described [61], [69]. Briefly, splenocytes were harvested at the indicated time points after infection and incubated with 5–25 nM PE or APC-conjugated FliC431–439-specific tetramer in Fc block for 1 hour at room temperature. These cells were then incubated with anti-PE or anti-APC magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) for 30 minutes on ice and column purified according to the manufacturer's instructions. The bound and unbound fractions were stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies for cell surface and intracellular staining. The absence of I-Ab FliC431–439 tetramer staining on CD8+ T cells, and among CD4+ T cells in the unbound fraction of cells after bead enrichment were used as independent markers to verify the specificity of tetramer staining using methods described (data not shown) [61].

Statistics

The differences in number of recoverable bacterial CFUs, and the number and percent T cells among from different groups of mice were evaluated using the Student's t test (GraphPad, Prism Software) with p<0.05 taken as statistical significance.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. HornickRB

GreismanSE

WoodwardTE

DuPontHL

DawkinsAT

1970 Typhoid fever: pathogenesis and immunologic control. N Engl J Med 283 686 691

2. HornickRB

GreismanSE

WoodwardTE

DuPontHL

DawkinsAT

1970 Typhoid fever: pathogenesis and immunologic control. 2. N Engl J Med 283 739 746

3. MerrellDS

FalkowS

2004 Frontal and stealth attack strategies in microbial pathogenesis. Nature 430 250 256

4. ParryCM

HienTT

DouganG

WhiteNJ

FarrarJJ

2002 Typhoid fever. N Engl J Med 347 1770 1782

5. BhanMK

BahlR

BhatnagarS

2005 Typhoid and paratyphoid fever. Lancet 366 749 762

6. MonackDM

MuellerA

FalkowS

2004 Persistent bacterial infections: the interface of the pathogen and the host immune system. Nat Rev Microbiol 2 747 765

7. BelkaidY

2007 Regulatory T cells and infection: a dangerous necessity. Nat Rev Immunol 7 875 888

8. BelkaidY

TarbellK

2009 Regulatory T cells in the control of host-microorganism interactions (*). Annu Rev Immunol 27 551 589

9. SuvasS

RouseBT

2006 Treg control of antimicrobial T cell responses. Curr Opin Immunol 18 344 348

10. PetersN

SacksD

2006 Immune privilege in sites of chronic infection: Leishmania and regulatory T cells. Immunol Rev 213 159 179

11. MendezS

RecklingSK

PiccirilloCA

SacksD

BelkaidY

2004 Role for CD4(+) CD25(+) regulatory T cells in reactivation of persistent leishmaniasis and control of concomitant immunity. J Exp Med 200 201 210

12. BelkaidY

PiccirilloCA

MendezS

ShevachEM

SacksDL

2002 CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control Leishmania major persistence and immunity. Nature 420 502 507

13. SuvasS

AzkurAK

KimBS

KumaraguruU

RouseBT

2004 CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells control the severity of viral immunoinflammatory lesions. J Immunol 172 4123 4132

14. SuvasS

KumaraguruU

PackCD

LeeS

RouseBT

2003 CD4+CD25+ T cells regulate virus-specific primary and memory CD8+ T cell responses. J Exp Med 198 889 901

15. KursarM

KochM

MittruckerHW

NouaillesG

BonhagenK

2007 Cutting Edge: Regulatory T cells prevent efficient clearance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol 178 2661 2665

16. HesseM

PiccirilloCA

BelkaidY

PruferJ

Mentink-KaneM

2004 The pathogenesis of schistosomiasis is controlled by cooperating IL-10-producing innate effector and regulatory T cells. J Immunol 172 3157 3166

17. LongTT

NakazawaS

OnizukaS

HuamanMC

KanbaraH

2003 Influence of CD4+CD25+ T cells on Plasmodium berghei NK65 infection in BALB/c mice. Int J Parasitol 33 175 183

18. HisaedaH

MaekawaY

IwakawaD

OkadaH

HimenoK

2004 Escape of malaria parasites from host immunity requires CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Med 10 29 30

19. UzonnaJE

WeiG

YurkowskiD

BretscherP

2001 Immune elimination of Leishmania major in mice: implications for immune memory, vaccination, and reactivation disease. J Immunol 167 6967 6974

20. HoriS

TakahashiT

SakaguchiS

2003 Control of autoimmunity by naturally arising regulatory CD4+ T cells. Adv Immunol 81 331 371

21. KhattriR

CoxT

YasaykoSA

RamsdellF

2003 An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat Immunol 4 337 342

22. FontenotJD

GavinMA

RudenskyAY

2003 Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 4 330 336

23. FontenotJD

RasmussenJP

WilliamsLM

DooleyJL

FarrAG

2005 Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity 22 329 341

24. KimJM

RasmussenJP

RudenskyAY

2007 Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat Immunol 8 191 197

25. LundJM

HsingL

PhamTT

RudenskyAY

2008 Coordination of early protective immunity to viral infection by regulatory T cells. Science 320 1220 1224

26. LanteriMC

O'BrienKM

PurthaWE

CameronMJ

LundJM

2009 Tregs control the development of symptomatic West Nile virus infection in humans and mice. J Clin Invest 119 3266 3277

27. GruenheidS

GrosP

2000 Genetic susceptibility to intracellular infections: Nramp1, macrophage function and divalent cations transport. Curr Opin Microbiol 3 43 48

28. MaloD

VoganK

VidalS

HuJ

CellierM

1994 Haplotype mapping and sequence analysis of the mouse Nramp gene predict susceptibility to infection with intracellular parasites. Genomics 23 51 61

29. MonackDM

BouleyDM

FalkowS

2004 Salmonella typhimurium persists within macrophages in the mesenteric lymph nodes of chronically infected Nramp1+/+ mice and can be reactivated by IFNgamma neutralization. J Exp Med 199 231 241

30. MittruckerHW

KohlerA

KaufmannSH

2002 Characterization of the murine T-lymphocyte response to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection. Infect Immun 70 199 203

31. NaucielC

1990 Role of CD4+ T cells and T-independent mechanisms in acquired resistance to Salmonella typhimurium infection. J Immunol 145 1265 1269

32. NaucielC

RoncoE

GuenetJL

PlaM

1988 Role of H-2 and non-H-2 genes in control of bacterial clearance from the spleen in Salmonella typhimurium-infected mice. Infect Immun 56 2407 2411

33. MittruckerHW

KaufmannSH

2000 Immune response to infection with Salmonella typhimurium in mice. J Leukoc Biol 67 457 463

34. CaramalhoI

Lopes-CarvalhoT

OstlerD

ZelenayS

HauryM

2003 Regulatory T cells selectively express toll-like receptors and are activated by lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med 197 403 411

35. LiuH

Komai-KomaM

XuD

LiewFY

2006 Toll-like receptor 2 signaling modulates the functions of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 7048 7053

36. CrellinNK

GarciaRV

HadisfarO

AllanSE

SteinerTS

2005 Human CD4+ T cells express TLR5 and its ligand flagellin enhances the suppressive capacity and expression of FOXP3 in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol 175 8051 8059

37. PengG

GuoZ

KiniwaY

VooKS

PengW

2005 Toll-like receptor 8-mediated reversal of CD4+ regulatory T cell function. Science 309 1380 1384

38. SutmullerRP

den BrokMH

KramerM

BenninkEJ

ToonenLW

2006 Toll-like receptor 2 controls expansion and function of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest 116 485 494

39. PasareC

MedzhitovR

2003 Toll pathway-dependent blockade of CD4+CD25+ T cell-mediated suppression by dendritic cells. Science 299 1033 1036

40. ThorntonAM

ShevachEM

1998 CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells suppress polyclonal T cell activation in vitro by inhibiting interleukin 2 production. J Exp Med 188 287 296

41. TakahashiT

KuniyasuY

TodaM

SakaguchiN

ItohM

1998 Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25+CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells: induction of autoimmune disease by breaking their anergic/suppressive state. Int Immunol 10 1969 1980

42. PiccirilloCA

ShevachEM

2001 Cutting edge: control of CD8+ T cell activation by CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory cells. J Immunol 167 1137 1140

43. LuuRA

GurnaniK

DudaniR

KammaraR

van FaassenH

2006 Delayed expansion and contraction of CD8+ T cell response during infection with virulent Salmonella typhimurium. J Immunol 177 1516 1525

44. MiyaraM

SakaguchiS

2007 Natural regulatory T cells: mechanisms of suppression. Trends Mol Med 13 108 116

45. VignaliDA

CollisonLW

WorkmanCJ

2008 How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol 8 523 532

46. WingK

OnishiY

Prieto-MartinP

YamaguchiT

MiyaraM

2008 CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science 322 271 275

47. AssemanC

MauzeS

LeachMW

CoffmanRL

PowrieF

1999 An essential role for interleukin 10 in the function of regulatory T cells that inhibit intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med 190 995 1004

48. MarieJC

LetterioJJ

GavinM

RudenskyAY

2005 TGF-beta1 maintains suppressor function and Foxp3 expression in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med 201 1061 1067

49. NakamuraK

KitaniA

StroberW

2001 Cell contact-dependent immunosuppression by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells is mediated by cell surface-bound transforming growth factor beta. J Exp Med 194 629 644

50. CaoX

CaiSF

FehnigerTA

SongJ

CollinsLI

2007 Granzyme B and perforin are important for regulatory T cell-mediated suppression of tumor clearance. Immunity 27 635 646

51. GotsmanI

GrabieN

GuptaR

DacostaR

MacConmaraM

2006 Impaired regulatory T-cell response and enhanced atherosclerosis in the absence of inducible costimulatory molecule. Circulation 114 2047 2055

52. KitazawaY

FujinoM

WangQ

KimuraH

AzumaM

2007 Involvement of the programmed death-1/programmed death-1 ligand pathway in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell activity to suppress alloimmune responses. Transplantation 83 774 782

53. DeaglioS

DwyerKM

GaoW

FriedmanD

UshevaA

2007 Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. J Exp Med 204 1257 1265

54. ShimizuJ

YamazakiS

TakahashiT

IshidaY

SakaguchiS

2002 Stimulation of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat Immunol 3 135 142

55. JiHB

LiaoG

FaubionWA

Abadia-MolinaAC

CozzoC

2004 Cutting edge: the natural ligand for glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor-related protein abrogates regulatory T cell suppression. J Immunol 172 5823 5827

56. ValzasinaB

GuiducciC

DislichH

KilleenN

WeinbergAD

2005 Triggering of OX40 (CD134) on CD4(+)CD25+ T cells blocks their inhibitory activity: a novel regulatory role for OX40 and its comparison with GITR. Blood 105 2845 2851

57. SuffiaIJ

RecklingSK

PiccirilloCA

GoldszmidRS

BelkaidY

2006 Infected site-restricted Foxp3+ natural regulatory T cells are specific for microbial antigens. J Exp Med 203 777 788

58. TaylorJJ

MohrsM

PearceEJ

2006 Regulatory T cell responses develop in parallel to Th responses and control the magnitude and phenotype of the Th effector population. J Immunol 176 5839 5847

59. McKeeAS

PearceEJ

2004 CD25+CD4+ cells contribute to Th2 polarization during helminth infection by suppressing Th1 response development. J Immunol 173 1224 1231

60. McSorleySJ

CooksonBT

JenkinsMK

2000 Characterization of CD4+ T cell responses during natural infection with Salmonella typhimurium. J Immunol 164 986 993

61. MoonJJ

ChuHH

PepperM

McSorleySJ

JamesonSC

2007 Naive CD4(+) T cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity 27 203 213

62. McCoyK

CamberisM

GrosGL

1997 Protective immunity to nematode infection is induced by CTLA-4 blockade. J Exp Med 186 183 187

63. RoweJH

JohannsTM

ErteltJM

LaiJC

WaySS

2009 Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 blockade augments the T-cell response primed by attenuated Listeria monocytogenes resulting in more rapid clearance of virulent bacterial challenge. Immunology 128 e471 478

64. FurzeRC

CulleyFJ

SelkirkME

2006 Differential roles of the co-stimulatory molecules GITR and CTLA-4 in the immune response to Trichinella spiralis. Microbes Infect 8 2803 2810

65. Scott-BrowneJP

ShafianiS

Tucker-HeardG

Ishida-TsubotaK

FontenotJD

2007 Expansion and function of Foxp3-expressing T regulatory cells during tuberculosis. J Exp Med 204 2159 2169

66. HisaedaH

TetsutaniK

ImaiT

MoriyaC

TuL

2008 Malaria parasites require TLR9 signaling for immune evasion by activating regulatory T cells. J Immunol 180 2496 2503

67. RauschS

HuehnJ

KirchhoffD

RzepeckaJ

SchnoellerC

2008 Functional analysis of effector and regulatory T cells in a parasitic nematode infection. Infect Immun 76 1908 1919

68. BaumgartM

TompkinsF

LengJ

HesseM

2006 Naturally occurring CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are an essential, IL-10-independent part of the immunoregulatory network in Schistosoma mansoni egg-induced inflammation. J Immunol 176 5374 5387

69. ErteltJM

RoweJH

JohannsTM

LaiJC

McLachlanJB

2009 Selective priming and expansion of antigen-specific Foxp3 − CD4+ T cells during Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol 182 3032 3038

70. HsiehCS

ZhengY

LiangY

FontenotJD

RudenskyAY

2006 An intersection between the self-reactive regulatory and nonregulatory T cell receptor repertoires. Nat Immunol 7 401 410

71. HsiehCS

LiangY

TyznikAJ

SelfSG

LiggittD

2004 Recognition of the peripheral self by naturally arising CD25+ CD4+ T cell receptors. Immunity 21 267 277

72. CozzoC

LermanMA

BoesteanuA

LarkinJ3rd

JordanMS

2005 Selection of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by self-peptides. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 293 3 23

73. KasowKA

ChenX

KnowlesJ

WichlanD

HandgretingerR

2004 Human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells share equally complex and comparable repertoires with CD4+CD25 − counterparts. J Immunol 172 6123 6128

74. FazilleauN

BachelezH

GougeonML

ViguierM

2007 Cutting edge: size and diversity of CD4+CD25high Foxp3+ regulatory T cell repertoire in humans: evidence for similarities and partial overlapping with CD4+CD25 − T cells. J Immunol 179 3412 3416

75. SakaguchiS

WingK

OnishiY

Prieto-MartinP

YamaguchiT

2009 Regulatory T cells: how do they suppress immune responses? Int Immunol 21 1105 1111

76. al-RamadiBK

ChenYW

MeisslerJJJr

EisensteinTK

1991 Immunosuppression induced by attenuated Salmonella. Reversal by IL-4. J Immunol 147 1954 1961

77. HoerttBE

OuJ

KopeckoDJ

BaronLS

WarrenRL

1989 Novel virulence properties of the Salmonella typhimurium virulence-associated plasmid: immune suppression and stimulation of splenomegaly. Plasmid 21 48 58

78. MacFarlaneAS

SchwachaMG

EisensteinTK

1999 In vivo blockage of nitric oxide with aminoguanidine inhibits immunosuppression induced by an attenuated strain of Salmonella typhimurium, potentiates Salmonella infection, and inhibits macrophage and polymorphonuclear leukocyte influx into the spleen. Infect Immun 67 891 898

79. MatsuiK

AraiT

1998 Salmonella infection-induced non-responsiveness of murine splenic T-lymphocytes to interleukin-2 (IL-2) involves inhibition of IL-2 receptor gamma chain expression. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 20 175 180

80. SrinivasanA

McSorleySJ

2007 Pivotal advance: exposure to LPS suppresses CD4+ T cell cytokine production in Salmonella-infected mice and exacerbates murine typhoid. J Leukoc Biol 81 403 411

81. FreudenbergMA

KumazawaY

MedingS

LanghorneJ

GalanosC

1991 Gamma interferon production in endotoxin-responder and -nonresponder mice during infection. Infect Immun 59 3484 3491

82. WeissDS

RaupachB

TakedaK

AkiraS

ZychlinskyA

2004 Toll-like receptors are temporally involved in host defense. J Immunol 172 4463 4469

83. Cervantes-BarraganL

Gil-CruzC

Pastelin-PalaciosR

LangKS

IsibasiA

2009 TLR2 and TLR4 signaling shapes specific antibody responses to Salmonella typhi antigens. Eur J Immunol 39 126 135

84. UematsuS

JangMH

ChevrierN

GuoZ

KumagaiY

2006 Detection of pathogenic intestinal bacteria by Toll-like receptor 5 on intestinal CD11c+ lamina propria cells. Nat Immunol 7 868 874

85. FeuilletV

MedjaneS

MondorI

DemariaO

PagniPP

2006 Involvement of Toll-like receptor 5 in the recognition of flagellated bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 12487 12492

86. MagnussonM

TobesR

SanchoJ

ParejaE

2007 Cutting edge: natural DNA repetitive extragenic sequences from gram-negative pathogens strongly stimulate TLR9. J Immunol 179 31 35

87. ForwardNA

FurlongSJ

YangY

LinTJ

HoskinDW

Signaling through TLR7 enhances the immunosuppressive activity of murine CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. J Leukoc Biol 87 117 125

88. JohannsTM

ErteltJM

LaiJC

RoweJH

AvantRA

2010 Naturally occurring altered peptide ligands control Salmonella-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation, IFN-gamma production, and protective potency. J Immunol 184 869 876

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiológia Infekčné lekárstvo Laboratórium

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2010 Číslo 8- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Očkování proti virové hemoragické horečce Ebola experimentální vakcínou rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP

- Koronavirus hýbe světem: Víte jak se chránit a jak postupovat v případě podezření?

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Dissecting the Genetic Architecture of Host–Pathogen Specificity

- The Battle for Iron between Bacterial Pathogens and Their Vertebrate Hosts

- Global Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in

- Burkholderia Type VI Secretion Systems Have Distinct Roles in Eukaryotic and Bacterial Cell Interactions

- Chitin Synthases from Are Involved in Tip Growth and Represent a Potential Target for Anti-Oomycete Drugs

- Distinct Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Molecular Features in Tumour and Non Tumour Specimens from Patients with Merkel Cell Carcinoma

- Biological and Structural Characterization of a Host-Adapting Amino Acid in Influenza Virus

- Functional Characterisation and Drug Target Validation of a Mitotic Kinesin-13 in

- CTCF Prevents the Epigenetic Drift of EBV Latency Promoter Qp

- The Human Fungal Pathogen Escapes Macrophages by a Phagosome Emptying Mechanism That Is Inhibited by Arp2/3 Complex-Mediated Actin Polymerisation

- Bim Nuclear Translocation and Inactivation by Viral Interferon Regulatory Factor

- Cyst Wall Protein 1 Is a Lectin That Binds to Curled Fibrils of the GalNAc Homopolymer

- Reciprocal Analysis of Infections of a Model Reveal Host-Pathogen Conflicts Mediated by Reactive Oxygen and imd-Regulated Innate Immune Response

- A Subset of Replication Proteins Enhances Origin Recognition and Lytic Replication by the Epstein-Barr Virus ZEBRA Protein

- Damaged Intestinal Epithelial Integrity Linked to Microbial Translocation in Pathogenic Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Infections

- Kaposin-B Enhances the PROX1 mRNA Stability during Lymphatic Reprogramming of Vascular Endothelial Cells by Kaposi's Sarcoma Herpes Virus

- Direct Interaction between Two Viral Proteins, the Nonstructural Protein 2C and the Capsid Protein VP3, Is Required for Enterovirus Morphogenesis

- A Novel CCR5 Mutation Common in Sooty Mangabeys Reveals SIVsmm Infection of CCR5-Null Natural Hosts and Efficient Alternative Coreceptor Use

- Micro RNAs of Epstein-Barr Virus Promote Cell Cycle Progression and Prevent Apoptosis of Primary Human B Cells

- Enterohemorrhagic Requires N-WASP for Efficient Type III Translocation but Not for EspF-Mediated Actin Pedestal Formation

- Host Imprints on Bacterial Genomes—Rapid, Divergent Evolution in Individual Patients

- UNC93B1 Mediates Host Resistance to Infection with

- The Transcription Factor Rbf1 Is the Master Regulator for -Mating Type Controlled Pathogenic Development in

- Protective Efficacy of Cross-Reactive CD8 T Cells Recognising Mutant Viral Epitopes Depends on Peptide-MHC-I Structural Interactions and T Cell Activation Threshold

- Bacteriophage Lysin Mediates the Binding of to Human Platelets through Interaction with Fibrinogen

- Insecticide Control of Vector-Borne Diseases: When Is Insecticide Resistance a Problem?

- Immune Modulation with Sulfasalazine Attenuates Immunopathogenesis but Enhances Macrophage-Mediated Fungal Clearance during Pneumonia

- PKC Signaling Regulates Drug Resistance of the Fungal Pathogen via Circuitry Comprised of Mkc1, Calcineurin, and Hsp90

- A Multi-Step Process of Viral Adaptation to a Mutagenic Nucleoside Analogue by Modulation of Transition Types Leads to Extinction-Escape

- “Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Sex (but Were Afraid to Ask)” in after Two Decades of Laboratory and Field Analyses