-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Sequestration and Tissue Accumulation of Human Malaria Parasites: Can We Learn Anything from Rodent Models of Malaria?

The sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum–infected red blood cells (irbcs) in the microvasculature of organs is associated with severe disease; correspondingly, the molecular basis of irbc adherence is an active area of study. In contrast to P. falciparum, much less is known about sequestration in other Plasmodium parasites, including those species that are used as models to study severe malaria. Here, we review the cytoadherence properties of irbcs of the rodent parasite Plasmodium berghei ANKA, where schizonts demonstrate a clear sequestration phenotype. Real-time in vivo imaging of transgenic P. berghei parasites in rodents has revealed a CD36-dependent sequestration in lungs and adipose tissue. In the absence of direct orthologs of the P. falciparum proteins that mediate binding to human CD36, the P. berghei proteins and/or mechanisms of rodent CD36 binding are as yet unknown. In addition to CD36-dependent schizont sequestration, irbcs accumulate during severe disease in different tissues, including the brain. The role of sequestration is discussed in the context of disease as are the general (dis)similarities of P. berghei and P. falciparum sequestration.

Published in the journal: Sequestration and Tissue Accumulation of Human Malaria Parasites: Can We Learn Anything from Rodent Models of Malaria?. PLoS Pathog 6(9): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001032

Category: Review

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001032Summary

The sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum–infected red blood cells (irbcs) in the microvasculature of organs is associated with severe disease; correspondingly, the molecular basis of irbc adherence is an active area of study. In contrast to P. falciparum, much less is known about sequestration in other Plasmodium parasites, including those species that are used as models to study severe malaria. Here, we review the cytoadherence properties of irbcs of the rodent parasite Plasmodium berghei ANKA, where schizonts demonstrate a clear sequestration phenotype. Real-time in vivo imaging of transgenic P. berghei parasites in rodents has revealed a CD36-dependent sequestration in lungs and adipose tissue. In the absence of direct orthologs of the P. falciparum proteins that mediate binding to human CD36, the P. berghei proteins and/or mechanisms of rodent CD36 binding are as yet unknown. In addition to CD36-dependent schizont sequestration, irbcs accumulate during severe disease in different tissues, including the brain. The role of sequestration is discussed in the context of disease as are the general (dis)similarities of P. berghei and P. falciparum sequestration.

Introduction

Erythrocytes infected with the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum are known to cytoadhere to endothelial cells lining blood vessels, and this feature is associated with a number of features of severe malaria pathology such as cerebral malaria (CM) and pregnancy-associated malaria (PAM). This adherence of infected red blood cells (irbcs) to host tissue, also known as sequestration, occurs in small capillaries and post-capillary venules of specific organs such as the brain and lungs. Sequestration has been correlated with mechanical obstruction of blood flow in small blood vessels and vascular endothelial cell activation, which may lead to pathology [1]–[11]. As sequestration appears to be a signature of severe disease, the factors that mediate irbc adherence to endothelial cells have been the focus of numerous studies. This has resulted in the identification of parasite proteins (ligands) and host endothelium proteins (receptors, adhesins) that are directly involved in sequestration [12]–[15]. It is anticipated that increased knowledge on important features of sequestration, such as polymorphisms of receptors and ligands and their interactions, tissue distribution, affinity/avidity of binding, etc., will aid in the development of novel strategies that either reduce disease or lead to complete protection, for example through the development of vaccines or small molecule inhibitors that inhibit sequestration [8], [15]–[17].

The rodent parasite Plasmodium berghei is one of the most well-employed models in malaria research, and this includes analyses on the severe pathology associated with malaria infections. In particular, P. berghei infections can induce a number of disease states in rodents such as cerebral complications in several strains of mice [18]–[23], pregnancy-associated pathology [24]–[26], and acute lung injury [27], [28]. To what extent these different pathologies observed in laboratory animals are representative for human pathology is a matter of debate and has been discussed in a number of review papers [8], [9], [19], [21], [25], [26], [29]–[33]. Based on a number of differences in clinical features of human cerebral malaria (HCM) caused by P. falciparum and the cerebral pathology of P. berghei infections in mice, the relevance of P. berghei for understanding HCM has been brought into question. However, it is evident that studies on so-called experimental cerebral malaria (ECM) induced by P. berghei have provided insights into the critical role that a variety of host immune factors play in inducing cerebral pathology in mice. It has been argued that this knowledge may indeed be relevant for understanding, at least in part, the pathology associated with HCM, as the human condition itself is likely to represent a spectrum of pathologies. Interestingly, in contrast to the large number of studies on the role that various immune factors play in producing or mitigating P. berghei ECM, the role of P. berghei irbc sequestration in inducing these different pathologies is less well understood. In some studies it has been reported that P. berghei ECM is not correlated with extensive schizont accumulation in small blood vessels of the brain; cerebral complications in most ECM-susceptible mouse strains is more often associated with an accumulation of immune cells in the brain such as monocytes/macrophages, T cells, and neutrophils, and sequestration of platelets [21], [34]–[39]. In contrast, other studies have reported that P. berghei ECM and PAM pathology is associated with irbc accumulation in tissues such as the brain and placenta [24], [40]–[43]. In this paper, we review the available knowledge and properties of P. berghei irbc sequestration and show how recent advances in in vivo imaging technologies, which permit the visualization of parasite distribution and load in different organs of live mice, are being used to address issues of sequestration and disease. An understanding of P. berghei sequestration may help define and refine the relevance of rodent infections in understanding the different features of sequestration and pathology associated with human malaria (see Box 1 for the terminology of P. berghei sequestration).

Box 1. Plasmodium berghei Sequestration Terminology

Cytoadherence of irbcs: The specific attachment of irbcs to endothelial cells of blood capillaries and post-capillary venules, mediated by host receptor(s) and parasite ligand(s).

Sequestration of irbcs: An accumulation of irbcs in organs as a result of specific interactions between parasite ligands and host receptors expressed on the endothelium of blood capillaries and post-capillary venules.

Parasite ligands: parasite factors expressed on the surface of irbcs that mediate adherence to endothelial cells of blood capillaries and post-capillary venules.

Host cell receptors (adhesions): molecules located on the surface of endothelial cells of blood capillaries and post-capillary venules that mediate sequestration of irbcs.

P. berghei CD36-mediated sequestration: Accumulation of schizonts in organs as a result of specific interactions between the host receptor CD36 and, as yet, unknown putative parasite ligand(s).

P. berghei tissue accumulation/sequestration: Accumulation of irbcs in organs as a result of interactions between yet unknown parasite ligands and unknown host receptors during malaria pathology (acute lung injury, ECM, and PAM).

P. berghei ANKA Schizont-Infected Erythrocytes Sequester

In P. falciparum, the absence of mature trophozoites, schizonts, and developing gametocytes from the peripheral blood circulation of humans is clear evidence for the sequestration of these stages (Table 1). For various reasons, the detection of P. berghei sequestration in mice by analyzing peripheral blood or tissue histology is more complicated. Infections in mice with P. berghei usually result in asynchronous parasite development, which in the circulation of the host manifests itself as the simultaneous presence of different parasite life cycle stages. Characterizing parasites in peripheral blood is additionally confounded as several stages are difficult to distinguish from each other, for example young gametocytes and asexual trophozoites [44], [45]. The asynchronous course of infection in combination with the P. berghei schizont stage of development being relatively short (i.e., only the last 4 hours of the 22-hour erythrocytic cycle) may also hinder the detection of schizonts in excised organ tissue by histology. P. berghei has a strong preference for young red blood cells, reticulocytes, and these become heavily invaded both early in an infection (when the parasite tends only to infect reticulocytes) and also late in an infection (when in response to malaria anemia the host produces more reticulocytes). This often results in the presence of multiply infected reticulocytes containing up to six to eight ring forms of the parasites [46], and these cells can easily be confused with schizonts, as the irbc now also has multiple nuclei. Moreover, in P. berghei infections with higher parasite loads (parasitemias greater than 5%), an increased number of schizonts are found in the blood circulation. It is unknown whether the presence of circulating schizonts at high parasite densities is due to the inability of schizonts to adhere to host endothelium or is caused by factors that are related to the high parasite loads. The particular characteristics of a P. berghei infection, and the fact that cerebral complications are not associated with extensive schizont accumulation in the brain, has led to the common misconception that cytoadherence of P. berghei schizonts to host microvasculature is not as pronounced as it is in P. falciparum.

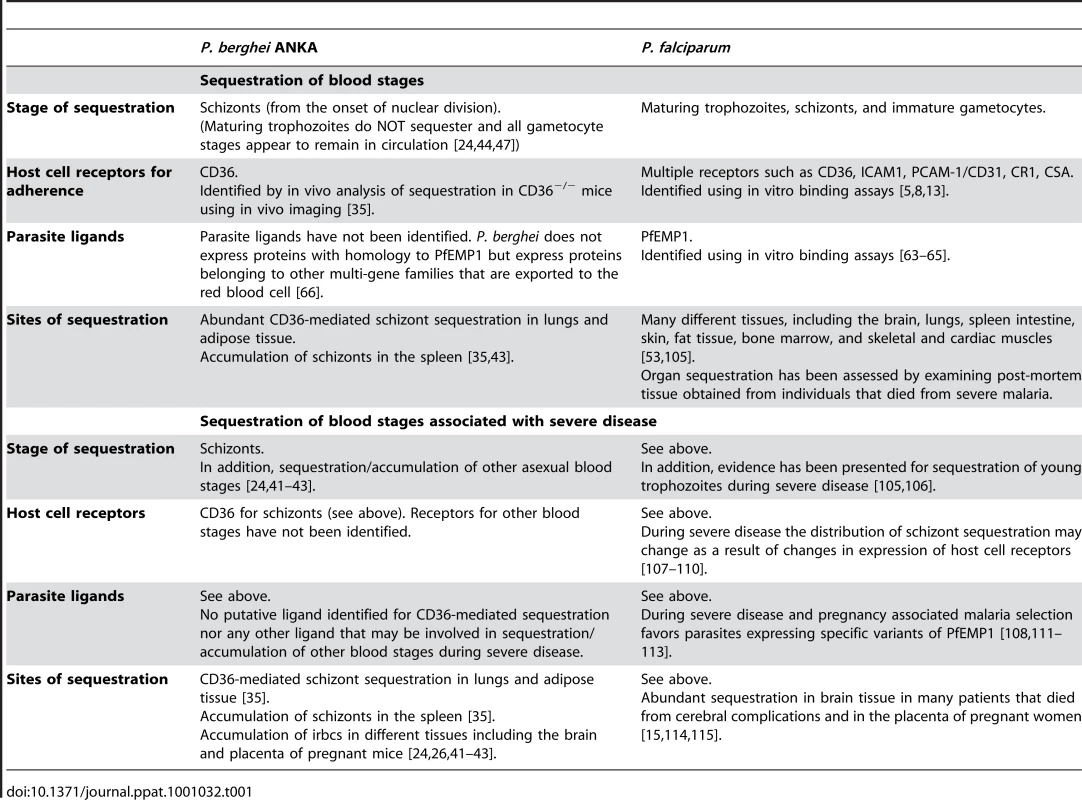

Tab. 1. Sequestration Properties of Blood Stages of <i>P. falciparum</i> in Humans and <i>P. berghei</i> ANKA in Rodents.

Analysis of peripheral blood of experimentally synchronized infections (see Box 2) has, however, clearly demonstrated that schizonts of the P. berghei ANKA strain have a distinct sequestration phenotype [35], [44], [47], resulting in the disappearance of all schizogonic stages from the peripheral blood circulation. Synchronized P. berghei infections in mice can be established by intravenous injection of purified, fully mature schizonts [44], [47]. In contrast to most other Plasmodium species, viable and fully mature P. berghei ANKA schizonts can easily be collected and purified from in vitro cultures ([48]; Figure 1A). Injection of these schizonts into naïve mice results in a rapid release of merozoites and an almost simultaneous re-invasion of erythrocytes. In this way, synchronized infections can be established with a stable parasitemia of 0.5%–3% at 4 hours after schizont injection with the newly invaded ring forms developing into mature trophozoites within 16–18 hours. These mature trophozoites then rapidly and reproducibly disappear from the blood circulation where >90% of the parasites that demonstrate nuclear division are absent from the peripheral blood, resulting in a clear drop in parasitemia between 18 and 22 hours after schizont injection (Figure 1A). At approximately 22 hours after inoculation, the first newly invaded merozoites re-appear in the blood circulation, and subsequent invasion of merozoites gives rise to a second cycle of synchronized development [35], [44]. Quantitative analysis of the different blood stages in synchronized infections has shown that ring stages and trophozoites (up to 16–18 hours old), as well as immature and mature gametocytes, all remain in circulation [44]. These observations conclusively demonstrate that P. berghei ANKA schizonts are being retained in deep tissue and, moreover, that this process is very tightly regulated, as sequestration of all parasites starts with the onset of nuclear division. This absence of schizonts in peripheral blood is not only observed in experimentally induced, synchronized P. berghei ANKA infections but also in asynchronous infections in mice, rats, and in the natural host Grammomys surdaster [35]. Thus the sequestration of P. berghei schizonts (i.e., their absence of the peripheral circulation) is comparable to P. falciparum schizont sequestration. However, in P. falciparum, in addition to schizonts, maturing trophozoites and immature gametocytes are absent from peripheral blood, whereas there is no evidence that these stages sequester in P. berghei infections (Table 1). Further, in P. berghei infections, schizonts are more often detected in peripheral blood at higher densities, whereas in P. falciparum infections in humans this is rarely observed.

Box 2. P. berghei ANKA Infections in Rodents

Synchronized infections: Experimentally induced infections by intravenous injection of mature schizonts resulting in the synchronized development of asexual blood stage parasites for up to two developmental cycles.

Asynchronous infections: Infections, usually established by an intra-peritoneal injection of 104–105 irbcs that exhibit all parasite developmental stages in the blood simultaneously. These infections result in ECM pathology in ECM-susceptible mice, usually on day 6–8 after infection.

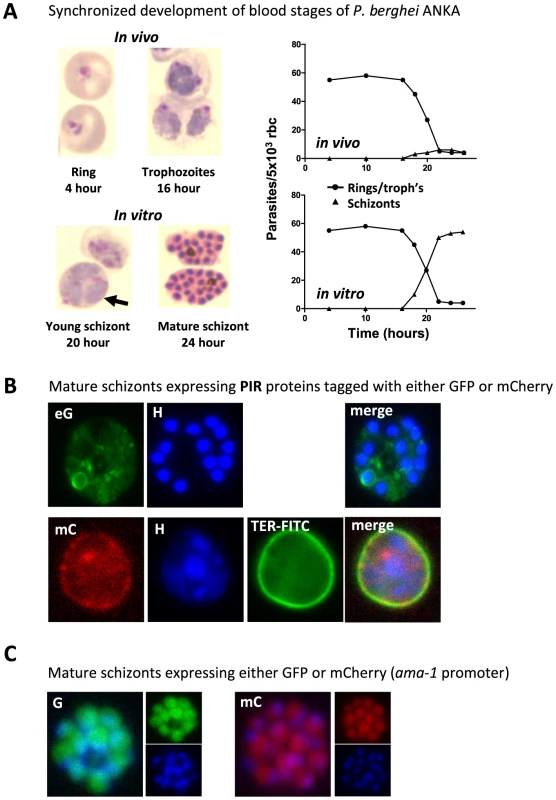

Fig. 1. P. berghei ANKA asexual blood stage development and expression of proteins in mature schizonts.

(A) In vivo and in vitro development of rings, trophozoites, and schizonts during one cycle of synchronized development. In mice, rings and trophozoites do not sequester but schizonts disappear from the peripheral circulation (upper graph). In vitro schizogony takes place between 18 and 24 hours after invasion of the red blood cell (lower graph). The arrow indicates a multiply infected red blood cell containing three trophozoite-stage parasites; above this cell is a 20-hour schizont (graphs adapted from [44] and [35]. (B) Live mature schizonts of two transgenic lines expressing two different fluorescently tagged PIR proteins either tagged with GFP (eG; PB200064.00.0) or mCherry (mC; PB200026.00.0). These proteins are exported into the cytoplasm of the erythrocyte nucleus stained with Hoechst (H; blue), red blood cell membrane surface protein stained in mC parasites (TER-FITC; green) (J. Braks and B. Franke-Fayard, unpublished data). (C) Live mature schizonts that express GFP and mCherry in the cytoplasm of the merozoites (J. Braks and B. Franke-Fayard, unpublished data). P. berghei ANKA Schizonts Accumulate in Lungs, Adipose Tissue, and Spleen

A number of histological studies of animals infected with P. berghei have failed to detect clear sequestration of irbcs, specifically schizonts, in the brain microvasculature during ECM, raising the question, if schizonts do not sequester in the brain, where are they retained? In more recent studies in which schizonts were visualized by real time imaging in live mice, it was revealed that the lungs, adipose tissue, and the spleen are the major organs in which schizonts specifically accumulate [35], [43], [49]. Infections with transgenic P. berghei ANKA parasites, expressing the bioluminescent reporter-protein luciferase in conjunction with real time imaging, have shown that schizonts can be clearly discerned in these organs (see Box 3 for different transgenic parasite lines used for in vivo imaging). By introducing the luciferase gene into the genome under the control of a schizont-specific promoter (i.e., the ama-1 promoter), only the schizont stage is made visible when detecting bioluminescence signals, and this stage of the parasite is specifically localized in lungs, adipose tissue, and the spleen (Figure 2). No significant level of schizont accumulation could be detected in other organs such as the brain, liver, and kidneys. This pattern of schizont accumulation is not restricted to experimentally induced, short-term synchronous infections; highly similar patterns of schizont accumulation have been found during asynchronous infections in both laboratory rodents and in G. surdaster [35]. In P. falciparum, sequestration in organs has mainly been assessed by examining post-mortem tissue obtained from individuals that died from malaria. These studies have revealed that P. falciparum schizonts sequester in differing amounts in tissues of a variety of organs (Table 1). The lung and the spleen are recognized sites for accumulation of P. falciparum schizonts, but adipose tissue sequestration is less reported on. However, in several studies this tissue has been identified as a site of P. falciparum schizont sequestration [50]–[52], [53]. What is less clear is whether the spleen in P. berghei–infected mice is a site of sequestration or if schizonts are trapped in the spleen as a result of selective clearance of irbcs from the blood [54]. For Plasmodium vivax it has been proposed that schizonts specifically adhere to barrier cells in the human spleen allowing the parasite to escape spleen-clearance while simultaneously facilitating the rapid invasion of reticulocytes [55], [56].

Box 3. Different Luciferase-Expressing P. berghei ANKA Parasites That Are Used for Real Time Imaging of Parasite Distribution in Live Mice

-

P. berghei ANKA: Luciferase expression controlled by the schizont-specific ama1-promoter, RMgm-30 and 32*

Analysis of sequestration of schizonts in synchronized infections. Bioluminescence of sequestered schizonts (also newly invaded ring forms show luminescence resulting from carry over of luciferase from the mature schizont stage).

-

P. berghei ANKA: Luciferase expression controlled by the constitutive “all stages” eef1a-promoter, RMgm-28 and 29*

Analysis of tissue distribution of irbcs. All stages are bioluminescent. These lines produce gametocytes that can complicate tissue distribution analyses as a result of high luminescence signals derived from circulating female gametocytes.

-

P. berghei ANKA: Luciferase expression controlled by the constitutive “all stages” eef1a-promoter, RMgm-333*

Analysis of tissue distribution of asexual blood stages. All stages are bioluminescent. This line does not produce gametocytes.

-

P. berghei K173: Luciferase expression controlled by the schizont-specific ama1-promoter, RMgm-375*

Bioluminescence of schizonts (also newly invaded ring forms show luminescence resulting from carry over of luciferase from the mature schizont stage). Schizonts of this line do not sequester and this line does not produce gametocytes.

-

P. berghei K173: Luciferase expression controlled by the schizont-specific ama1-promoter, RMgm-380*

All stages are bioluminescent. Schizonts of this line do not sequester and this line does not produce gametocytes.

*These lines have been described in the RMgm-database (http://www.pberghei.eu/) of P. berghei mutants.

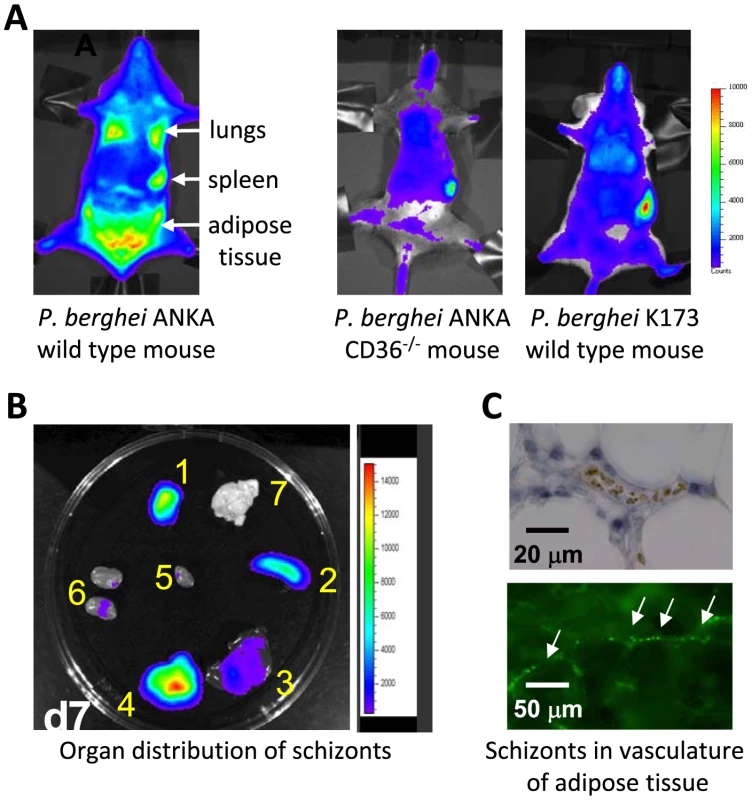

Fig. 2. Imaging of transgenic P. berghei ANKA parasites in vivo and ex vivo.

CD36-mediated sequestration of schizonts in adipose tissue and lungs (adapted from PNAS, 2005 [35]). (A, B) Distribution of transgenic P. berghei ANKA parasites, expressing GFP::luciferase fusion protein (ama-1 promoter, see Box 3). Parasites are visible in lungs, spleen, and adipose tissue in wild-type mice, and principally in the blood circulation and accumulated in the spleen in CD36 knock-out mice. In wild-type mice infected with a non-sequestering K173 line, schizonts are also mainly found in the peripheral blood circulation and accumulated in the spleen (1: adipose tissue; 2: spleen; 3 liver; 4: lungs; 5: heart; 6: kidney; 7: brain). (C) Sequestration of transgenic P. berghei ANKA parasites in microvasculature of adipose tissue (upper panel with under phase contrast and lower panel with GFP-positive schizonts indicated by arrows). CD36 Is a Major Receptor for P. berghei ANKA Schizont Sequestration in Lungs and Adipose Tissue

Through the use of in vitro binding assays, a number of host molecules that are expressed on the surface of endothelial cells have been identified as playing a role in P. falciparum irbc adherence, such as CD36, ICAM-1, PCAM-1/CD31, CR1, and chondroitin sulphate A (CSA) (for review see [5], [8], [13]). Infected erythrocytes from different P. falciparum isolates have quite different binding affinities and preferences with respect to these host receptors [8], [57], [58]. Most P. falciparum isolates, however, demonstrate a capacity to bind to CD36 [58], and CD36 and CSA are the only two receptors that maintain a stable stationary adherence to irbcs.

The application of in vivo imaging techniques in laboratory animals that either express or lack CD36 revealed that CD36 also has a major role in P. berghei schizont sequestration, specifically in adipose tissue and lungs (Figure 1; [35]). In animals deficient in expressing CD36, the sequestration of schizonts in both the lungs and adipose tissue was strongly reduced. This was the first report, in any Plasmodium species, that analyzed irbc sequestration to host cell receptors in a living animal, and in real time through the course of an infection. In mice there is very little or no CD36 expression on endothelium of brain capillaries and post-capillary venules [59], [60], but there are high levels of CD36 expression on endothelium of lungs and adipose tissue [60], [61]. This sequestration is clearly consistent with schizont sequestration in the lungs and adipose tissue and absence of sequestration in the brain. Compared to the lungs or adipose tissue, P. berghei schizont accumulation in the spleen does not decrease in the absence of CD36 (Figure 1; [35]), and therefore accumulation in this organ results either from “nonspecific trapping” of schizonts or from interactions of schizonts to alternative host receptors. The role of CD36 as a major receptor for the adherence of P. falciparum irbcs to endothelial cells is well established and this receptor is known to be abundantly expressed on the surface of capillary endothelial cells in human adipose tissue [60], [61]. Surprisingly, however, no detailed studies have been conducted in human malaria on the extent and importance of adipose tissue. The observations of CD36-mediated sequestration of P. berghei and binding of irbcs of Plasmodium chabaudi to CD36 [62] suggest that binding to CD36 is an “ancient” feature of the Plasmodium genus. It would also indicate that rodent parasites modulate the surface of irbcs through the active export of proteins that contain as yet unidentified and potentially conserved receptor-binding domains (see below).

Parasite Ligands Involved in CD36-Mediated Sequestration of P. berghei ANKA Schizonts Are Still Unknown

The variant protein PfEMP1 plays a major role in adherence of P. falciparum irbcs to different endothelial host receptors. This protein is encoded by a family of approximately 60 (var) genes within each parasite genome, and the expression of these proteins is mutually exclusive with only one PfEMP1 expressed on the surface of the irbc at any one time (for reviews see [63]). The extracellular region of this protein contains multiple adhesion domains, such as DBL domains, named for their homology to the EBL domains involved in red blood cell invasion, and one to two cysteine-rich interdomain regions (CIDRs). The binding domains for several host receptors have been mapped to the various DBL and CIDR domains with the CIDR1α domain mediating binding to CD36 [64], [65]. The P. berghei genome does not contain genes with homology to the var genes [66] and, as yet, no other P. berghei proteins have been identified that may bind to CD36. Hidden Markov Model (HMM) building using P. falciparum CIDR and DBL domains, followed by searches of all predicted P. berghei proteins available in PlasmoDB (release 6.3), have not provided evidence for the presence of proteins containing these domains (J. Fonager, unpublished data). Indeed, the only proteins in rodent malaria parasites that have been identified as being either expressed close to or on the irbc surface are members of the variant multigene family “Plasmodium interspersed repeats” (PIRs) [67]. These genes are shared between human, rodent, and monkey malaria species [68]–[71]. It is, however, questionable whether these proteins mediate adherence of schizonts to CD36. PIR proteins are also expressed in the human parasite P. vivax [56], [72], and although it has been suggested that sequestration of P. vivax irbcs might occur in the spleen and in other organs such as the lung during severe disease [55], [73], [74], there is no evidence for adherence of the schizonts stage to CD36 since in most infections schizonts can be found in the peripheral circulation. In addition, it is also not clear yet whether the putative extracellular domains of these proteins are indeed exposed on the outer erythrocyte membrane [56]. Analysis of the localization of two GFP - and mCherry-tagged P. berghei members of this family (PB200064.00.0; PB200026.00.0) showed that these proteins are exported into the host erythrocyte, but we have been unable to demonstrate an exposed surface location of these proteins ([75]; B.F. and J. Fonager, unpublished data; Figure 1B). Various other multigene families exist in P. berghei that have features of proteins exported into the host erythrocyte and which may modify the surface membrane of the irbc. For example, P. berghei orthologs to genes encoding proteins of the PYST-A and PYST-B gene families contain either predicted signal peptides only (PYST-A) or predicted signal peptide and the Plasmodium export (PEXEL) motif (PYST-B) [69], [76] that target proteins out of the parasite into the red blood cell, and we have indeed found that PYST-A proteins are exported into the cytoplasm of the erythrocyte (J. Braks, unpublished data). It is, however, possible that CD36-mediated schizont sequestration in P. berghei does not depend on the incorporation of parasite molecules onto the irbc surface but is the result of changes in the red blood cell membrane itself. For instance, the intracellular parasite may cause a disruption in the asymmetric distribution of molecules in the irbc membrane bilayer, for example, phosphatidylserine (PS). This molecule, PS, is localized on the inner leaflet of the lipid bilayer and can become “flipped” on to the outer surface of the erythrocyte under some physiological conditions. It is known that PS is able to interact directly with CD36 [77]–[79], and evidence has been found that adherence of P. falciparum irbcs to CD36 is in part mediated by surface-exposed PS on irbcs. Similarly, it has been proposed that P. falciparum is able to modify the red blood cell protein band 3, and such modifications permit irbc adherence to CD36 [13]; the parasite proteins responsible for this alteration of band 3 remain to be characterized. Clearly, further research is required to unravel the mechanisms and proteins involved that mediate CD36-sequestration of P. berghei schizonts. Leaving aside issues relating to cerebral complications, a greater understanding of the cellular and tissue distribution of CD36 in the host as well as the mechanisms by which this receptor is recognized by P. berghei parasites is likely to shed light on what are likely to be very similar processes in CD36-mediated sequestration of P. falciparum irbcs.

Is CD36-Mediated Sequestration of Schizonts Associated with Cerebral Complications in Mice?

Several studies report evidence indicating that CD36-mediated sequestration of P. berghei is not directly associated with cerebral pathology. Firstly, infections in CD36-deficient mice exhibit no sequestration in lungs and adipose tissue but still develop ECM [27], [35]. In addition, a P. berghei ANKA mutant, generated by a single gene deletion, is found not to induce cerebral complications but shows a completely normal distribution of CD36-mediated schizont sequestration [43]. Lastly, ECM-susceptible mice infected with a laboratory line of the K173 strain of P. berghei parasites that lack schizont sequestration do develop ECM (Figure 2; [80], [81]). The absence of schizont sequestration can most likely be explained by the laboratory history of this line; it has been kept for more than 20 years in mice by mechanical blood passage and has completely lost gametocyte production and schizont sequestration, and its chromosomes are reduced in size as a result of the loss of subtelomeric genes and repeat elements ([82], [83]; J. Fonager, unpublished data). This line has frequently been used to study P. berghei ECM [80], [81], supporting the other published observations that schizont sequestration is not a prerequisite for P. berghei ECM. Interestingly, parasites of another laboratory line of the K173 strain have been shown not to induce cerebral complications [84], [85]. The sequestration pattern of the schizonts of this line is unknown, but these observations show that the capacity to induce ECM is not a stable feature of P. berghei strains. This has also been shown by analyzing clones of the ANKA strain that showed differences in their abilities to induce ECM [23].

The significance of studies examining P. berghei ECM for understanding human pathology has been brought into question, mainly because a number of differences exist in cerebral pathology between mice and humans, and also because of the observation that there appears to be a close association between the level of sequestration in the brain and HCM [33]. Therefore, the lack of an association between CD36-mediated schizonts sequestration and cerebral complications in P. berghei–infected mice appears to challenge the relevance of P. berghei as a model of HCM [33]. However, the contribution of P. falciparum CD36-mediated irbc adherence to human pathology is also not resolved. For example, in human infections, variation in irbc binding to CD36 has been correlated with either no effect, an increase, or a decrease in disease severity [86]–[91]. As expression of CD36 on endothelium in the brain is virtually absent, direct adherence of irbcs to endothelial CD36 is unlikely to account for significant cerebral sequestration. On the other hand, CD36 is highly expressed on monocytes, macrophages, and platelets, and it has been proposed that irbc sequestration in the brain may be mediated via irbc attachment to CD36 of sequestered platelets that act as a bridge between endothelial cells and irbcs [92], [93]. Severity of disease has also been attributed to platelet-mediated clumping of P. falciparum irbcs [90]. It has been argued that CD36 may also have a beneficial role in that the innate immune response may be modulated by irbc binding to CD36 on macrophages, resulting in non-opsonic phagocytosis [59], [94], [95]. A beneficial effect of CD36 expression on macrophages and dendritic cells resulting in reduced virulence has also been observed in P. berghei infections [96]. Moreover, adherence to CD36 expressed in microvascular endothelium of the skin and adipose tissue may reduce pathology, as it directs irbcs away from more vital and potentially life threatening sites such as the cerebral microvasculature. Although a clear association between sequestered irbcs and HCM exists in P. falciparum, additional investigations are required to unravel the role that CD36-dependent cytoadherence has for either pathogenesis or protection from disease in P. falciparum infections.

Evidence for CD36-Independent Sequestration of P. berghei ANKA

The distribution of P. berghei schizonts in the organs in mice has principally been analyzed by the imaging of schizonts in short-term synchronous infections in living animals. Such patterns are not likely to identify alterations in sequestration due to changes in expression of other putative endothelial receptors, something that is likely to occur after the initial stage of an infection. For example, it has been shown that inflammatory markers and adhesins such as ICAM-1 become up-regulated on endothelium of the brain and lung microvasculature during P. berghei ECM [27], [97], [98]. When the distribution of P. berghei schizonts was imaged in live mice during prolonged infections, no major changes in the organ distribution of schizont sequestration were observed [35]. This would suggest that CD36 remains the major binding receptor for schizonts and that there is no obvious switch in schizont adherence phenotype during an infection. Several recent studies have shown, however, that severe disease complications such as ECM and PAM are associated with a distinct increase of irbcs accumulating in different tissues, including the brain and placenta [24], [41]–[43], indicating that additional factors play a role in irbc sequestration after the initial phase of a P. berghei infection. It has been shown by in vivo imaging that the timing of this irbc accumulation in the brain coincides with the development of cerebral complications, and mice protected from cerebral complications do not show a similar increase of irbc sequestration in the brain (Figure 3). In these studies the parasites used for in vivo imaging of sequestered irbcs expressed luciferase under the control of the constitutive P. berghei eef1a promoter (Box 3), and therefore it is not possible to discriminate between sequestered schizonts and other blood stage parasites such as rings and trophozoites. Whether this tissue accumulation of irbcs during severe disease is mediated by specific interactions between parasite ligands and endothelial receptors brain capillaries and post-capillary venules or is the result of other mechanisms (see above) of irbc trapping in small blood capillaries is unknown. For example, P. berghei irbcs have been observed to attach to the surface of endothelium-adherent monocytes/macrophages [21]. Evidence has also been found for irbc accumulation in capillaries as a result of adherence to sequestered platelets [37]. As increased mononuclear cell [34] and platelet sequestration [37], [39] is observed in the brain vessels of mice during ECM, monocyte/platelet-trapped irbcs may account, at least in part, for parasites present in the brain vasculature. On the other hand, P. berghei irbcs have been observed in close contact with the microvascular endothelium [40], indicating that irbcs may directly adhere to endothelial cells. Further analysis is required to provide an insight into both the amounts of parasites (i.e., load) that accumulate in the brain and the stage of the parasite that is found in tissue during severe disease. The generation of transgenic P. berghei parasites expressing different fluorescent reporter proteins (e.g., GFP and mCherry; see Figure 1C) now offers the possibility of directly visualizing interactions between host cells and irbcs in the brain of living mice by, for example, using multiphoton microscopy to perform intravital imaging [99]–[102]. An understanding of the mechanisms of CD36-independent sequestration may help to define the contribution of other host receptors to irbc adherence and the relationship with induction of pathology.

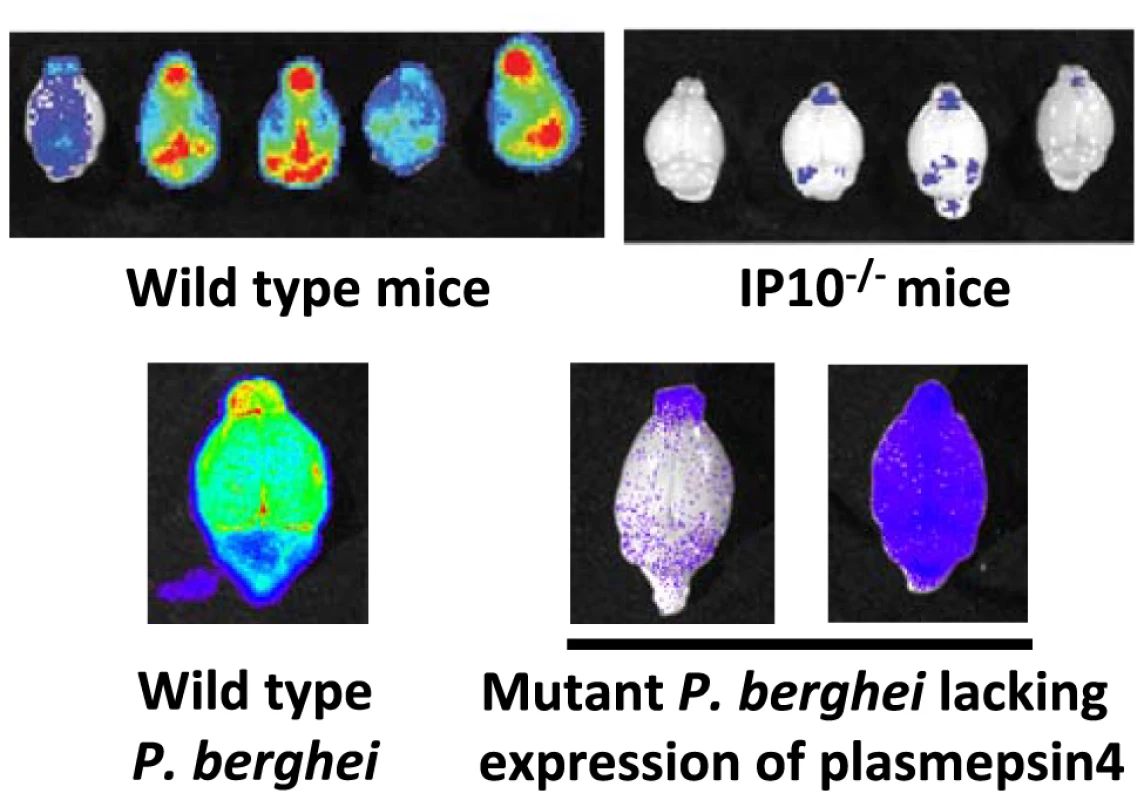

Fig. 3. Imaging of transgenic P. berghei ANKA parasites in brains of mice ex vivo.

Matched sets of experiments with P. berghei ANKA infections in ECM-sensitive mice (i.e., wild-type mice) or knock-out mice (i.e., IP10−/−). Knock-out mice do not develop cerebral pathology and this corresponds to a strong reduction in irbc accumulation as compared to infections in wild-type mice (adapted from [41]). Similar examples of a lack of irbc accumulation can be observed in the brains of mice treated with antibodies against host molecules (e.g., anti-LTβ mAB and anti-CD25 mAB; see [42], [104]). Parasites express GFP::luciferase fusion protein under the control of the eef1a promoter, see Box 3). Also, mice infected with a P. berghei ANKA mutant that has had the gene encoding plasmepsin 4 removed do not develop cerebral complications, and again there is a strong reduction of irbc accumulation in the brain of these infected animals (adapted from [43]). In addition to CD36-mediated schizont sequestration and irbc sequestration during ECM, evidence has also been found for adherence of P. berghei irbcs to CSA present on the surface of syncytiotrophoblasts in the placenta of pregnant mice. Specifically, irbcs in pregnancy-induced recrudescent infections showed an enhancement of in vitro adherence to placenta tissue with a marked specificity for CSA [26]. As with CD36 sequestration, the P. berghei ligands mediating adherence to CSA are also unknown.

Conclusion

Revealing where and when P. berghei sequesters in a living host, by real time imaging of transgenic parasites, has opened up exciting possibilities into research looking at sequestration and the contribution this has to different aspects of malarial disease. Schizonts of P. berghei sequester in the body of living animals in distinct locations, and this appears to be related to the expression of host CD36 with abundant sequestration in adipose tissue and lungs. CD36-mediated schizont sequestration is not observed in the brain, but evidence has been presented for a CD36-independent accumulation of irbcs in different tissues during severe disease, including the brain. The characterization and the genetic modification of P. berghei ligands involved in binding to the different host receptors might offer novel possibilities in the development of small-animal models for analysis of sequestration properties of P. falciparum ligands that have hitherto only been examined in vitro. This could be performed by, for example, substituting P. berghei ligands with P. falciparum PfEMP-1 proteins or domains. Using in vivo imaging in conjunction with such “falciparumized” P. berghei parasites in mice expressing human receptors (e.g., human ICAM-1; [103]) may create an in vivo screening system for testing inhibitors that block P. falciparum sequestration. Despite clear differences between the rodent model and human infections, we believe enough similarities remain that justify further studies on P. berghei sequestration for obtaining more insight into how the malaria parasite uses sequestration to survive inside the host, how this may provoke disease, and how interventions may work.

Zdroje

1. RogersonSJ

HviidL

DuffyPE

LekeRF

TaylorDW

2007 Malaria in pregnancy: pathogenesis and immunity. Lancet Infect Dis 7 105 117

2. DesaiM

ter KuileFO

NostenF

McGreadyR

AsamoaK

2007 Epidemiology and burden of malaria in pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis 7 93 104

3. BeesonJG

DuffyPE

2005 The immunology and pathogenesis of malaria during pregnancy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 297 187 227

4. MackintoshCL

BeesonJG

MarshK

2004 Clinical features and pathogenesis of severe malaria. Trends Parasitol 20 597 603

5. RastiN

WahlgrenM

ChenQ

2004 Molecular aspects of malaria pathogenesis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 41 9 26

6. ClarkIA

AllevaLM

MillsAC

CowdenWB

2004 Pathogenesis of malaria and clinically similar conditions. Clin Microbiol Rev 17 509 39, table

7. van der HeydeHC

NolanJ

CombesV

GramagliaI

GrauGE

2006 A unified hypothesis for the genesis of cerebral malaria: sequestration, inflammation and hemostasis leading to microcirculatory dysfunction. Trends Parasitol 22 503 508

8. MillerLH

BaruchDI

MarshK

DoumboOK

2002 The pathogenic basis of malaria. Nature 415 673 679

9. IdroR

JenkinsNE

NewtonCR

2005 Pathogenesis, clinical features, and neurological outcome of cerebral malaria. Lancet Neurol 4 827 840

10. SchofieldL

GrauGE

2005 Immunological processes in malaria pathogenesis. Nat Rev Immunol 5 722 735

11. MishraSK

NewtonCR

2009 Diagnosis and management of the neurological complications of falciparum malaria. Nat Rev Neurol 5 189 198

12. KraemerSM

SmithJD

2006 A family affair: var genes, PfEMP1 binding, and malaria disease. Curr Opin Microbiol 9 374 380

13. ShermanIW

EdaS

WinogradE

2003 Cytoadherence and sequestration in Plasmodium falciparum: defining the ties that bind. Microbes Infect 5 897 909

14. DeitschKW

HviidL

2004 Variant surface antigens, virulence genes and the pathogenesis of malaria. Trends Parasitol 20 562 566

15. GamainB

SmithJD

ViebigNK

GysinJ

ScherfA

2007 Pregnancy-associated malaria: parasite binding, natural immunity and vaccine development. Int J Parasitol 37 273 283

16. RoweJA

ClaessensA

CorriganRA

ArmanM

2009 Adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to human cells: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev Mol Med 11 e16

17. HviidL

2010 The role of Plasmodium falciparum variant surface antigens in protective immunity and vaccine development. Hum Vaccin 6 84 89

18. LambTJ

BrownDE

PotocnikAJ

LanghorneJ

2006 Insights into the immunopathogenesis of malaria using mouse models. Expert Rev Mol Med 8 1 22

19. EngwerdaC

BelnoueE

GrunerAC

ReniaL

2005 Experimental models of cerebral malaria. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 297 103 143

20. de SouzaJB

RileyEM

2002 Cerebral malaria: the contribution of studies in animal models to our understanding of immunopathogenesis. Microbes Infect 4 291 300

21. MartinsYC

SmithMJ

Pelajo-MachadoM

WerneckGL

LenziHL

2009 Characterization of cerebral malaria in the outbred Swiss Webster mouse infected by Plasmodium berghei ANKA. Int J Exp Pathol 90 119 130

22. RandallLM

AmanteFH

McSweeneyKA

ZhouY

StanleyAC

2008 Common strategies to prevent and modulate experimental cerebral malaria in mouse strains with different susceptibilities. Infect Immun 76 3312 3320

23. AmaniV

BoubouMI

PiedS

MarussigM

WallikerD

1998 Cloned lines of Plasmodium berghei ANKA differ in their abilities to induce experimental cerebral malaria. Infect Immun 66 4093 4099

24. NeresR

MarinhoCR

GoncalvesLA

CatarinoMB

Penha-GoncalvesC

2008 Pregnancy outcome and placenta pathology in Plasmodium berghei ANKA infected mice reproduce the pathogenesis of severe malaria in pregnant women. PLoS ONE 3 e1608 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001608

25. MegnekouR

HviidL

StaalsoeT

2009 Variant-specific immunity to Plasmodium berghei in pregnant mice. Infect Immun 77 1827 1834

26. MarinhoCR

NeresR

EpiphanioS

GoncalvesLA

CatarinoMB

2009 Recrudescent Plasmodium berghei from pregnant mice displays enhanced binding to the placenta and induces protection in multigravida. PLoS ONE 4 e5630 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005630

27. LovegroveFE

GharibSA

Pena-CastilloL

PatelSN

RuzinskiJT

2008 Parasite burden and CD36-mediated sequestration are determinants of acute lung injury in an experimental malaria model. PLoS Pathog 4 e1000068 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000068

28. Van den SteenPE

GeurtsN

DeroostK

VanAI

VerhenneS

2010 Immunopathology and dexamethasone therapy in a new model for malaria-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181 957 968

29. HuntNH

GrauGE

2003 Cytokines: accelerators and brakes in the pathogenesis of cerebral malaria. Trends Immunol 24 491 499

30. PoovasseryJS

SarrD

SmithG

NagyT

MooreJM

2009 Malaria-induced murine pregnancy failure: distinct roles for IFN-gamma and TNF. J Immunol 183 5342 5349

31. deSBJ

HafallaJC

RileyEM

CouperKN

2009 Cerebral malaria: why experimental murine models are required to understand the pathogenesis of disease. Parasitology 1 18

32. DavisonBB

CogswellFB

BaskinGB

FalkensteinKP

HensonEW

2000 Placental changes associated with fetal outcome in the Plasmodium coatneyi/rhesus monkey model of malaria in pregnancy. Am J Trop Med Hyg 63 158 173

33. WhiteNJ

TurnerGD

MedanaIM

DondorpAM

DayNP

2009 The murine cerebral malaria phenomenon. Trends Parasitol 26 11 15

34. ReniaL

PotterSM

MauduitM

RosaDS

KayibandaM

DescheminJC

SnounouG

GrunerAC

2006 Pathogenic T cells in cerebral malaria. Int J Parasitol 36 547 554

35. Franke-FayardB

JanseCJ

Cunha-RodriguesM

RamesarJ

BuscherP

2005 Murine malaria parasite sequestration: CD36 is the major receptor, but cerebral pathology is unlinked to sequestration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 11468 11473

36. LouJ

LucasR

GrauGE

2001 Pathogenesis of cerebral malaria: recent experimental data and possible applications for humans. Clin Microbiol Rev 14 810 20, table

37. CombesV

ColtelN

FailleD

WassmerSC

GrauGE

2006 Cerebral malaria: role of microparticles and platelets in alterations of the blood-brain barrier. Int J Parasitol 36 541 546

38. GrauGE

BielerG

PointaireP

DeKS

Tacchini-CotierF

1990 Significance of cytokine production and adhesion molecules in malarial immunopathology. Immunol Lett 25 189 194

39. SunG

ChangWL

LiJ

BerneySM

KimpelD

2003 Inhibition of platelet adherence to brain microvasculature protects against severe Plasmodium berghei malaria. Infect Immun 71 6553 6561

40. HearnJ

RaymentN

LandonDN

KatzDR

de SouzaJB

2000 Immunopathology of cerebral malaria: morphological evidence of parasite sequestration in murine brain microvasculature. Infect Immun 68 5364 5376

41. NieCQ

BernardNJ

NormanMU

AmanteFH

LundieRJ

2009 IP-10-mediated T cell homing promotes cerebral inflammation over splenic immunity to malaria infection. PLoS Pathog 5 e1000369 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000369

42. AmanteFH

StanleyAC

RandallLM

ZhouY

HaqueA

2007 A role for natural regulatory T cells in the pathogenesis of experimental cerebral malaria. Am J Pathol 171 548 559

43. SpaccapeloR

JanseCJ

CaterbiS

Franke-FayardB

BonillaJA

2010 Plasmepsin 4-deficient Plasmodium berghei are virulence attenuated and induce protective immunity against experimental malaria. Am J Pathol 176 205 217

44. MonsB

JanseCJ

BoorsmaEG

Van der KaayHJ

1985 Synchronized erythrocytic schizogony and gametocytogenesis of Plasmodium berghei in vivo and in vitro. Parasitology 91 Pt 3 423 430

45. JanseCJ

WatersAP

2004 Sexual development of malaria parasites.

WatersAP

JanseCJ

Malaria parasites: genomes and molecular biology Norwich Caister Academic Press 445 475

46. LandauI

BoulardY

1978 Rodent malaria.

Killick-KendrickR

PetersW

London Academic Press 53 84

47. JanseCJ

WatersAP

1995 Plasmodium berghei: the application of cultivation and purification techniques to molecular studies of malaria parasites. Parasitol Today 11 138 143

48. JanseCJ

RamesarJ

WatersAP

2006 High-efficiency transfection and drug selection of genetically transformed blood stages of the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei. Nat Protoc 1 346 356

49. Franke-FayardB

WatersAP

JanseCJ

2006 Real-time in vivo imaging of transgenic bioluminescent blood stages of rodent malaria parasites in mice. Nat Protoc 1 476 485

50. MillerLH

1969 Distribution of mature trophozoites and schizonts of Plasmodium falciparum in the organs of Aotus trivirgatus, the night monkey. Am J Trop Med Hyg 18 860 865

51. MillerLH

FremountHN

LuseSA

1971 Deep vascular schizogony of Plasmodium knowlesi in Macaca mulatta. Distribution in organs and ultrastructure of parasitized red cells. Am J Trop Med Hyg 20 816 824

52. WilairatanaP

RigantiM

PuchadapiromP

PunpoowongB

VannaphanS

2000 Prognostic significance of skin and subcutaneous fat sequestration of parasites in severe falciparum malaria. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 31 203 212

53. HaldarK

MurphySC

MilnerDA

TaylorTE

2007 Malaria: mechanisms of erythrocytic infection and pathological correlates of severe disease. Annu Rev Pathol 2 217 249

54. EngwerdaCR

BeattieL

AmanteFH

2005 The importance of the spleen in malaria. Trends Parasitol 21 75 80

55. del PortilloHA

LanzerM

Rodriguez-MalagaS

ZavalaF

Fernandez-BecerraC

2004 Variant genes and the spleen in Plasmodium vivax malaria. Int J Parasitol 34 1547 1554

56. Fernandez-BecerraC

YamamotoMM

VencioRZ

LacerdaM

Rosanas-UrgellA

2009 Plasmodium vivax and the importance of the subtelomeric multigene vir superfamily. Trends Parasitol 25 44 51

57. BeesonJG

BrownGV

MolyneuxME

MhangoC

DzinjalamalaF

1999 Plasmodium falciparum isolates from infected pregnant women and children are associated with distinct adhesive and antigenic properties. J Infect Dis 180 464 472

58. NewboldC

WarnP

BlackG

BerendtA

CraigA

1997 Receptor-specific adhesion and clinical disease in Plasmodium falciparum. Am J Trop Med Hyg 57 389 398

59. PatelSN

SerghidesL

SmithTG

FebbraioM

SilversteinRL

2004 CD36 mediates the phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes by rodent macrophages. J Infect Dis 189 204 213

60. GreenwaltDE

ScheckSH

Rhinehart-JonesT

1995 Heart CD36 expression is increased in murine models of diabetes and in mice fed a high fat diet. J Clin Invest 96 1382 1388

61. FebbraioM

HajjarDP

SilversteinRL

2001 CD36: a class B scavenger receptor involved in angiogenesis, atherosclerosis, inflammation, and lipid metabolism. J Clin Invest 108 785 791

62. MotaMM

JarraW

HirstE

PatnaikPK

HolderAA

2000 Plasmodium chabaudi-infected erythrocytes adhere to CD36 and bind to microvascular endothelial cells in an organ-specific way. Infect Immun 68 4135 4144

63. ScherfA

PouvelleB

BuffetPA

GysinJ

2001 Molecular mechanisms of Plasmodium falciparum placental adhesion. Cell Microbiol 3 125 131

64. SmithJD

KyesS

CraigAG

FaganT

Hudson-TaylorD

1998 Analysis of adhesive domains from the A4VAR Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein-1 identifies a CD36 binding domain. Mol Biochem Parasitol 97 133 148

65. KleinMM

GittisAG

SuHP

MakobongoMO

MooreJM

2008 The cysteine-rich interdomain region from the highly variable plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein-1 exhibits a conserved structure. PLoS Pathog 4 e1000147 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000147

66. HallN

KarrasM

RaineJD

CarltonJM

KooijTW

2005 A comprehensive survey of the Plasmodium life cycle by genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses. Science 307 82 86

67. CunninghamDA

JarraW

KoernigS

FonagerJ

Fernandez-ReyesD

2005 Host immunity modulates transcriptional changes in a multigene family (yir) of rodent malaria. Mol Microbiol 58 636 647

68. del PortilloHA

Fernandez-BecerraC

BowmanS

OliverK

PreussMS

2001 A superfamily of variant genes encoded in the subtelomeric region of Plasmodium vivax. Nature 410 839 842

69. CarltonJM

AngiuoliSV

SuhBB

KooijTW

PerteaM

2002 Genome sequence and comparative analysis of the model rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium yoelii yoelii. Nature 419 512 519

70. JanssenCS

BarrettMP

TurnerCM

PhillipsRS

2002 A large gene family for putative variant antigens shared by human and rodent malaria parasites. Proc Biol Sci 269 431 436

71. JanssenCS

PhillipsRS

TurnerCM

BarrettMP

2004 Plasmodium interspersed repeats: the major multigene superfamily of malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res 32 5712 5720

72. Fernandez-BecerraC

PeinO

de OliveiraTR

YamamotoMM

CassolaAC

2005 Variant proteins of Plasmodium vivax are not clonally expressed in natural infections. Mol Microbiol 58 648 658

73. AnsteyNM

HandojoT

PainMC

KenangalemE

TjitraE

2007 Lung injury in vivax malaria: pathophysiological evidence for pulmonary vascular sequestration and posttreatment alveolar-capillary inflammation. J Infect Dis 195 589 596

74. AnsteyNM

RussellB

YeoTW

PriceRN

2009 The pathophysiology of vivax malaria. Trends Parasitol 25 220 227

75. DiGF

RaggiC

BiragoC

PizziE

LalleM

2008 Plasmodium lipid rafts contain proteins implicated in vesicular trafficking and signalling as well as members of the PIR superfamily, potentially implicated in host immune system interactions. Proteomics 8 2500 2513

76. SargeantTJ

MartiM

CalerE

CarltonJM

SimpsonK

2006 Lineage-specific expansion of proteins exported to erythrocytes in malaria parasites. Genome Biol 7 R12

77. GreenbergME

SunM

ZhangR

FebbraioM

SilversteinR

2006 Oxidized phosphatidylserine-CD36 interactions play an essential role in macrophage-dependent phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. J Exp Med 203 2613 2625

78. EdaS

ShermanIW

2002 Cytoadherence of malaria-infected red blood cells involves exposure of phosphatidylserine. Cell Physiol Biochem 12 373 384

79. ManodoriAB

BarabinoGA

LubinBH

KuypersFA

2000 Adherence of phosphatidylserine-exposing erythrocytes to endothelial matrix thrombospondin. Blood 95 1293 1300

80. CurfsJH

van der MeerJW

SauerweinRW

ElingWM

1990 Low dosages of interleukin 1 protect mice against lethal cerebral malaria. J Exp Med 172 1287 1291

81. HermsenCC

MommersE

van deWT

SauerweinRW

ElingWM

1998 Convulsions due to increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier in experimental cerebral malaria can be prevented by splenectomy or anti-T cell treatment. J Infect Dis 178 1225 1227

82. JanseCJ

BoorsmaEG

RamesarJ

GrobbeeMJ

MonsB

1989 Host cell specificity and schizogony of Plasmodium berghei under different in vitro conditions. Int J Parasitol 19 509 514

83. JanseCJ

BoorsmaEG

RamesarJ

vanVP

van derMR

1989 Plasmodium berghei: gametocyte production, DNA content, and chromosome-size polymorphisms during asexual multiplication in vivo. Exp Parasitol 68 274 282

84. SanniLA

RaeC

MaitlandA

StockerR

HuntNH

2001 Is ischemia involved in the pathogenesis of murine cerebral malaria? Am J Pathol 159 1105 1112

85. MitchellAJ

HansenAM

HeeL

BallHJ

PotterSM

2005 Early cytokine production is associated with protection from murine cerebral malaria. Infect Immun 73 5645 5653

86. RogersonSJ

TembenuR

DobanoC

PlittS

TaylorTE

1999 Cytoadherence characteristics of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes from Malawian children with severe and uncomplicated malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 61 467 472

87. TraoreB

MuanzaK

LooareesuwanS

SupavejS

KhusmithS

2000 Cytoadherence characteristics of Plasmodium falciparum isolates in Thailand using an in vitro human lung endothelial cells model. Am J Trop Med Hyg 62 38 44

88. CortesA

MellomboM

MgoneCS

BeckHP

ReederJC

2005 Adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells to CD36 under flow is enhanced by the cerebral malaria-protective trait South-East Asian ovalocytosis. Mol Biochem Parasitol 142 252 257

89. AitmanTJ

CooperLD

NorsworthyPJ

WahidFN

GrayJK

2000 Malaria susceptibility and CD36 mutation. Nature 405 1015 1016

90. RobertsDJ

PainA

KaiO

KortokM

MarshK

2000 Autoagglutination of malaria-infected red blood cells and malaria severity. Lancet 355 1427 1428

91. CholeraR

BrittainNJ

GillrieMR

Lopera-MesaTM

DiakiteSA

2008 Impaired cytoadherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes containing sickle hemoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 991 996

92. WassmerSC

LepolardC

TraoreB

PouvelleB

GysinJ

2004 Platelets reorient Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocyte cytoadhesion to activated endothelial cells. J Infect Dis 189 180 189

93. GrauGE

MackenzieCD

CarrRA

RedardM

PizzolatoG

2003 Platelet accumulation in brain microvessels in fatal pediatric cerebral malaria. J Infect Dis 187 461 466

94. McGilvrayID

SerghidesL

KapusA

RotsteinOD

KainKC

2000 Nonopsonic monocyte/macrophage phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum-parasitized erythrocytes: a role for CD36 in malarial clearance. Blood 96 3231 3240

95. SerghidesL

KainKC

2001 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-retinoid X receptor agonists increase CD36-dependent phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum-parasitized erythrocytes and decrease malaria-induced TNF-alpha secretion by monocytes/macrophages. J Immunol 166 6742 6748

96. Cunha-RodriguesM

PortugalS

FebbraioM

MotaMM

2007 Bone marrow chimeric mice reveal a dual role for CD36 in Plasmodium berghei ANKA infection. Malar J 6 32

97. BauerPR

van der HeydeHC

SunG

SpecianRD

GrangerDN

2002 Regulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression in an experimental model of cerebral malaria. Microcirculation 9 463 470

98. LiJ

ChangWL

SunG

ChenHL

SpecianRD

2003 Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 is important for the development of severe experimental malaria but is not required for leukocyte adhesion in the brain. J Investig Med 51 128 140

99. GraeweS

RetzlaffS

StruckN

JanseCJ

HeusslerVT

2009 Going live: a comparative analysis of the suitability of the RFP derivatives RedStar, mCherry and tdTomato for intravital and in vitro live imaging of Plasmodium parasites. Biotechnol J 4 895 902

100. ZarbockA

LeyK

2009 New insights into leukocyte recruitment by intravital microscopy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 334 129 152

101. SvobodaK

YasudaR

2006 Principles of two-photon excitation microscopy and its applications to neuroscience. Neuron 50 823 839

102. DiasproA

ChiricoG

ColliniM

2005 Two-photon fluorescence excitation and related techniques in biological microscopy. Q Rev Biophys 38 97 166

103. DufresneAT

GromeierM

2004 A nonpolio enterovirus with respiratory tropism causes poliomyelitis in intercellular adhesion molecule 1 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 13636 13641

104. RandallLM

AmanteFH

ZhouY

StanleyAC

HaqueA

2008 Cutting edge: selective blockade of LIGHT-lymphotoxin beta receptor signaling protects mice from experimental cerebral malaria caused by Plasmodium berghei ANKA. J Immunol 181 7458 7462

105. SeydelKB

MilnerDAJr

KamizaSB

MolyneuxME

TaylorTE

2006 The distribution and intensity of parasite sequestration in comatose Malawian children. J Infect Dis 194 208 5

106. SilamutK

PhuNH

WhittyC

TurnerGD

LouwrierK

1999 A quantitative analysis of the microvascular sequestration of malaria parasites in the human brain. Am J Pathol 155 395 410

107. ChakravortySJ

HughesKR

CraigAG

2008 Host response to cytoadherence in Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem Soc Trans 36 221 228

108. ScherfA

Lopez-RubioJJ

RiviereL

2008 Antigenic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. Annu Rev Microbiol 62 445 470

109. DondorpAM

DesakornV

PongtavornpinyoW

SahassanandaD

SilamutK

2005 Estimation of the total parasite biomass in acute falciparum malaria from plasma PfHRP2. PLoS Med 2 e204 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020204

110. PongponratnE

TurnerGD

DayNP

PhuNH

SimpsonJA

2003 An ultrastructural study of the brain in fatal Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg 69 345 359

111. PasternakND

DzikowskiR

2009 PfEMP1: an antigen that plays a key role in the pathogenicity and immune evasion of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41 1463 1466

112. WarimweGM

KeaneTM

FeganG

MusyokiJN

NewtonCR

2009 Plasmodium falciparum var gene expression is modified by host immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 21801 21806

113. SalantiA

DahlbackM

TurnerL

NielsenMA

BarfodL

2004 Evidence for the involvement of VAR2CSA in pregnancy-associated malaria. J Exp Med 200 1197 1203

114. TaylorTE

FuWJ

CarrRA

WhittenRO

MuellerJS

2004 Differentiating the pathologies of cerebral malaria by postmortem parasite counts. Nat Med 10 143 145

115. FriedM

DuffyPE

1996 Adherence of Plasmodium falciparum to chondroitin sulfate A in the human placenta. Science 272 1502 1504

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiológia Infekčné lekárstvo Laboratórium

Článek SRFR1 Negatively Regulates Plant NB-LRR Resistance Protein Accumulation to Prevent AutoimmunityČlánek Inhibition of TIR Domain Signaling by TcpC: MyD88-Dependent and Independent Effects on VirulenceČlánek Phylogenetic Approach Reveals That Virus Genotype Largely Determines HIV Set-Point Viral LoadČlánek A Family of Plasmodesmal Proteins with Receptor-Like Properties for Plant Viral Movement Proteins

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2010 Číslo 9- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Očkování proti virové hemoragické horečce Ebola experimentální vakcínou rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP

- Koronavirus hýbe světem: Víte jak se chránit a jak postupovat v případě podezření?

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Azole Drugs Are Imported By Facilitated Diffusion in and Other Pathogenic Fungi

- Two Genes on A/J Chromosome 18 Are Associated with Susceptibility to Infection by Combined Microarray and QTL Analyses

- Impact of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Infection on Chimpanzee Population Dynamics

- Breaking the Stereotype: Virulence Factor–Mediated Protection of Host Cells in Bacterial Pathogenesis

- The Canine Papillomavirus and Gamma HPV E7 Proteins Use an Alternative Domain to Bind and Destabilize the Retinoblastoma Protein

- Rescue of HIV-1 Release by Targeting Widely Divergent NEDD4-Type Ubiquitin Ligases and Isolated Catalytic HECT Domains to Gag

- Steric Shielding of Surface Epitopes and Impaired Immune Recognition Induced by the Ebola Virus Glycoprotein

- Dynamics of the Multiplicity of Cellular Infection in a Plant Virus

- HLA Class I Binding of HBZ Determines Outcome in HTLV-1 Infection

- Pathogenic Bacteria Target NEDD8-Conjugated Cullins to Hijack Host-Cell Signaling Pathways

- The HA and NS Genes of Human H5N1 Influenza A Virus Contribute to High Virulence in Ferrets

- SRFR1 Negatively Regulates Plant NB-LRR Resistance Protein Accumulation to Prevent Autoimmunity

- Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Activity Controls the Onset of the HCMV Lytic Cycle

- The N-Terminal Domain of the Arenavirus L Protein Is an RNA Endonuclease Essential in mRNA Transcription

- Generation of Neutralizing Antibodies and Divergence of SIVmac239 in Cynomolgus Macaques Following Short-Term Early Antiretroviral Therapy

- Inhibition of TIR Domain Signaling by TcpC: MyD88-Dependent and Independent Effects on Virulence

- Intracellular Proton Conductance of the Hepatitis C Virus p7 Protein and Its Contribution to Infectious Virus Production

- The Transcriptome of the Human Pathogen at Single-Nucleotide Resolution

- The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Promotes Uptake of Influenza A Viruses (IAV) into Host Cells

- Surface Co-Expression of Two Different PfEMP1 Antigens on Single -Infected Erythrocytes Facilitates Binding to ICAM1 and PECAM1

- Sequestration and Tissue Accumulation of Human Malaria Parasites: Can We Learn Anything from Rodent Models of Malaria?

- Phylogenomics of Ligand-Gated Ion Channels Predicts Monepantel Effect

- Generation of Covalently Closed Circular DNA of Hepatitis B Viruses via Intracellular Recycling Is Regulated in a Virus Specific Manner

- CpG-Methylation Regulates a Class of Epstein-Barr Virus Promoters

- Molecular and Evolutionary Bases of Within-Patient Genotypic and Phenotypic Diversity in Extraintestinal Infections

- A Bistable Switch and Anatomical Site Control Virulence Gene Expression in the Intestine

- Are Members of the Fungal Genus (a) Commensals; (b) Opportunists; (c) Pathogens; or (d) All of the Above?

- Structures of Receptor Complexes of a North American H7N2 Influenza Hemagglutinin with a Loop Deletion in the Receptor Binding Site

- Phylogenetic Approach Reveals That Virus Genotype Largely Determines HIV Set-Point Viral Load

- The Coevolution of Virulence: Tolerance in Perspective

- Involvement of the Cytokine MIF in the Snail Host Immune Response to the Parasite

- Structure of the Extracellular Portion of CD46 Provides Insights into Its Interactions with Complement Proteins and Pathogens

- A Family of Plasmodesmal Proteins with Receptor-Like Properties for Plant Viral Movement Proteins

- High Content Phenotypic Cell-Based Visual Screen Identifies Acyltrehalose-Containing Glycolipids Involved in Phagosome Remodeling

- A Novel Small Molecule Inhibitor of Hepatitis C Virus Entry

- The Microbiota Mediates Pathogen Clearance from the Gut Lumen after Non-Typhoidal Diarrhea

- RNA Polymerases (L-Protein) Have an N-Terminal, Influenza-Like Endonuclease Domain, Essential for Viral Cap-Dependent Transcription

- Pathogen Specific, IRF3-Dependent Signaling and Innate Resistance to Human Kidney Infection

- Cellular Entry of Ebola Virus Involves Uptake by a Macropinocytosis-Like Mechanism and Subsequent Trafficking through Early and Late Endosomes

- The Length of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Particles Dictates a Need for Actin Assembly during Clathrin-Dependent Endocytosis

- Formation of Mobile Chromatin-Associated Nuclear Foci Containing HIV-1 Vpr and VPRBP Is Critical for the Induction of G2 Cell Cycle Arrest

- Association of Tat with Promoters of PTEN and PP2A Subunits Is Key to Transcriptional Activation of Apoptotic Pathways in HIV-Infected CD4+ T Cells

- Metal Hyperaccumulation Armors Plants against Disease

- Cyclin-Dependent Kinase-Like Function Is Shared by the Beta- and Gamma- Subset of the Conserved Herpesvirus Protein Kinases

- Role of Acetyl-Phosphate in Activation of the Rrp2-RpoN-RpoS Pathway in

- Ebolavirus Is Internalized into Host Cells Macropinocytosis in a Viral Glycoprotein-Dependent Manner

- A Novel Family of IMC Proteins Displays a Hierarchical Organization and Functions in Coordinating Parasite Division

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Structure of the Extracellular Portion of CD46 Provides Insights into Its Interactions with Complement Proteins and Pathogens

- The Length of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Particles Dictates a Need for Actin Assembly during Clathrin-Dependent Endocytosis

- Inhibition of TIR Domain Signaling by TcpC: MyD88-Dependent and Independent Effects on Virulence

- The Coevolution of Virulence: Tolerance in Perspective

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy