-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Type I Interferon Signaling Regulates Ly6C Monocytes and Neutrophils during Acute Viral Pneumonia in Mice

Type I interferon (IFN-I) plays a critical role in the homeostasis of hematopoietic stem cells and influences neutrophil influx to the site of inflammation. IFN-I receptor knockout (Ifnar1−/−) mice develop significant defects in the infiltration of Ly6Chi monocytes in the lung after influenza infection (A/PR/8/34, H1N1). Ly6Chi monocytes of wild-type (WT) mice are the main producers of MCP-1 while the alternatively generated Ly6Cint monocytes of Ifnar1−/− mice mainly produce KC for neutrophil influx. As a consequence, Ifnar1−/− mice recruit more neutrophils after influenza infection than do WT mice. Treatment of IFNAR1 blocking antibody on the WT bone marrow (BM) cells in vitro failed to differentiate into Ly6Chi monocytes. By using BM chimeric mice (WT BM into Ifnar1−/− and vice versa), we confirmed that IFN-I signaling in hematopoietic cells is required for the generation of Ly6Chi monocytes. Of note, WT BM reconstituted Ifnar1−/− chimeric mice with increased numbers of Ly6Chi monocytes survived longer than influenza-infected Ifnar1−/− mice. In contrast, WT mice that received Ifnar1−/− BM cells with alternative Ly6Cint monocytes and increased numbers of neutrophils exhibited higher mortality rates than WT mice given WT BM cells. Collectively, these data suggest that IFN-I contributes to resistance of influenza infection by control of monocytes and neutrophils in the lung.

Published in the journal: Type I Interferon Signaling Regulates Ly6C Monocytes and Neutrophils during Acute Viral Pneumonia in Mice. PLoS Pathog 7(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001304

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001304Summary

Type I interferon (IFN-I) plays a critical role in the homeostasis of hematopoietic stem cells and influences neutrophil influx to the site of inflammation. IFN-I receptor knockout (Ifnar1−/−) mice develop significant defects in the infiltration of Ly6Chi monocytes in the lung after influenza infection (A/PR/8/34, H1N1). Ly6Chi monocytes of wild-type (WT) mice are the main producers of MCP-1 while the alternatively generated Ly6Cint monocytes of Ifnar1−/− mice mainly produce KC for neutrophil influx. As a consequence, Ifnar1−/− mice recruit more neutrophils after influenza infection than do WT mice. Treatment of IFNAR1 blocking antibody on the WT bone marrow (BM) cells in vitro failed to differentiate into Ly6Chi monocytes. By using BM chimeric mice (WT BM into Ifnar1−/− and vice versa), we confirmed that IFN-I signaling in hematopoietic cells is required for the generation of Ly6Chi monocytes. Of note, WT BM reconstituted Ifnar1−/− chimeric mice with increased numbers of Ly6Chi monocytes survived longer than influenza-infected Ifnar1−/− mice. In contrast, WT mice that received Ifnar1−/− BM cells with alternative Ly6Cint monocytes and increased numbers of neutrophils exhibited higher mortality rates than WT mice given WT BM cells. Collectively, these data suggest that IFN-I contributes to resistance of influenza infection by control of monocytes and neutrophils in the lung.

Introduction

Type I interferons (IFN-I) are produced by different cell types including alveolar macrophages (AM), plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and epithelial cells following virus infection in the lung [1], [2]. These IFN-I cytokines engage a unique heterodimeric IFN-α receptor (IFNAR) to induce various antiviral effectors [3]. IFN-I-related antiviral effectors, including protein kinase PKR [4], 2′-5′-oligo A synthetase [5], and Mx-GTPase [6], control influenza virus infection by their own or in cooperation with various other signaling pathways [7], [8]. Even though influenza NS1 protein provides antagonistic properties against IFN-I-inducible antiviral proteins, which help virus to circumvent host barriers [9], increased susceptibility in Ifnar1−/− mice indicates that IFN-I signaling still plays a significant role in protecting the host after influenza infection in vivo [10], [11].

Monocytes emigrate from bone marrow (BM) thorough CCR2 receptor-mediated signaling and then monocyte-derived cells mediate inflammatory responses against influenza infection [12], [13]. Because of the important function of these monocytes, IFN-I signaling-mediated monocyte differentiation should be examined to better understand the regulation of leukocyte differentiation at large. In accordance, one recent study showed that IFN-I signaling triggers hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) proliferation [14]. Similarly, mice lacking IFN regulatory factor-2, a suppressor of IFN-I signaling, fail to maintain quiescent HSC [15]. These studies of the effect of IFN-I on regulation of cell homeostasis may explain different cell constitutions of Ifnar1−/− mice. However, specific cell populations directly affected by IFN-I during hematopoiesis and their contributions toward unique cell composition in peripheral tissues are not yet described. Thus, the role of IFN-I on the regulation of overall monocyte differentiation and infiltration into inflamed tissue needs to be analyzed in depth.

Although neutrophils are universally accepted as important in bacterial infection resistance [16], their role in viral infection remains controversial. Tate and colleagues reported that mice undergo more pronounced disease when neutrophils are absent [17], [18]. However, depletion of neutrophils not only results in increased viral burden but also in decreased lung inflammation, indicating that neutrophils contribute to control virus dissemination but may augment overall pathogenesis [19]. Clinically, excessive neutrophil recruitment, especially after highly pathogenic avian H5N1 or 1918 pandemic influenza infection, seems to play a detrimental role in acute lung injury [20], [21]. Thus, neutrophil infiltration seems to be closely related to tissue damage following infection as well as to inflammation, and the feed-back regulation of neutrophil recruitment to the site of infection needs to be tightly regulated.

In the current study, we adopted the influenza infection model and found that Ifnar1−/− mice undergo more acute and severe inflammation than B6 wild-type (WT) mice. IFN-I was directly involved in Ly6Chi monocyte differentiation from its precursor and these Ly6Chi monocytes exclusively provided MCP-1 in the lung after influenza infection. Further, Ifnar1−/− mice with defects in monocyte maturation produced excess KC chemokine and developed high mortality and severe neutrophilia when compared with WT mice. Our results suggest that IFN-I is required to resist influenza infection by orchestrating the leukocyte population in the lung and chemokines produced by those cells.

Results

Ifnar1−/− mice develop more acute and severe lung inflammation than WT mice

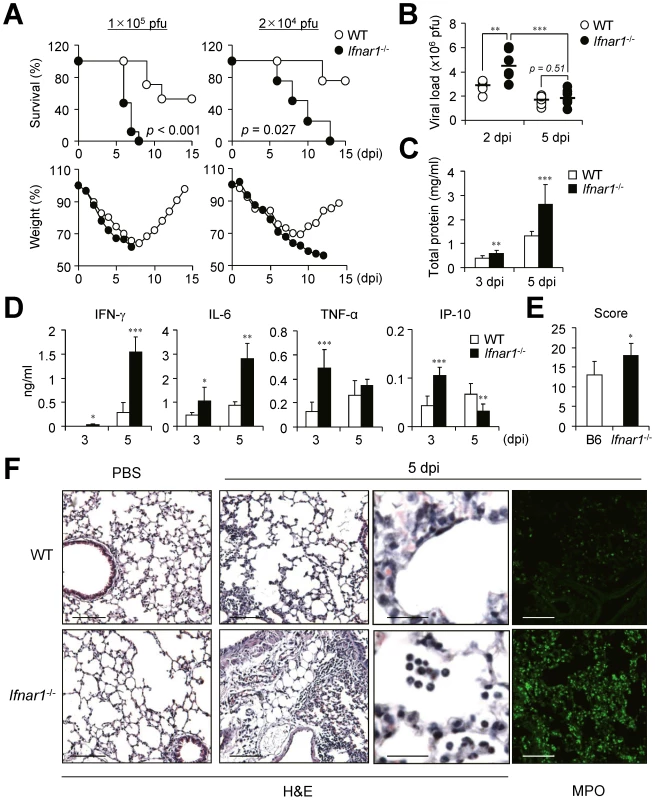

Because many previous studies indicate a crucial role for IFN-I in host defense against influenza infection, we looked for crucial regulatory factors that are mainly regulated by IFN-I after influenza infection using Ifnar1−/− mice of B6 background. First we challenged Ifnar1−/− and WT mice with a lethal dose (1×105 pfu) of PR8 virus. The Ifnar1−/− mice started to die 5 days post infection (dpi) and all were dead within 8 dpi while approximately 50% of WT mice survived (Figure 1A). When we decreased the challenge dose of PR8 virus (2×104 pfu), virus infection killed Ifnar1−/− mice from 5 dpi and no mice survived at 13 dpi while 80% of WT B6 mice survived (Figure 1A). WT mice started to regain body weight 8 or 9 days after infection while Ifnar1−/− mice continued to lose weight until they died (Figure 1A). Since the contribution of IFN-I in viral clearance is controversial [22], [23], we next addressed viral titer in the lung at 2 and 5 dpi with influenza PR8 virus (1×105 pfu). Intriguingly, Ifnar1−/− mice showed higher viral titer in the lung than WT mice at 2 dpi but not at 5 dpi (Figure 1B). However, total protein levels were significantly higher in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of Ifnar1−/− mice at 5 dpi than in WT mice (Figure 1C). Of note, significant levels of IL-6, TNF-α and IP-10 were determined at 3 dpi in the BALF of Ifnar1−/− mice and high levels IFN-γ and IL-6 at 5 dpi when compared with levels in WT mice (Figure 1D). Lung histopathology of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice after H&E staining revealed more edema, alveolar hemorrhage, alveolar wall thickness, and neutrophil infiltration in Ifnar1−/− mice than in WT mice at 5 dpi (Figure 1E and 1F). Staining specifically for myeloperoxidase (MPO), most abundantly present in the granules of neutrophils, confirmed increased numbers of MPO+ neutrophils in the lung of Ifnar1−/− mice after influenza infection (Figure 1F).

Fig. 1. Ifnar1−/− mice are more susceptible to influenza infection than wild-type (WT) mice.

(A) Survival and weight loss of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice after intranasal (i.n.) infection with 1×105 pfu or 2×104 pfu PR8 virus. (B) Viral load was measured by plaque assay in the lung of mice infected with 1×105 pfu PR8 virus at 2 (n = 6) and 5 (n = 11) days post infection (dpi). Total protein (C) and cytokine (D) levels were determined in the BALF of PR8-infected mice at 3 and 5 dpi. (C, D) Values are mean + SD and results are representative of three independent experiments with n>5 for each group. Histopathological scores (E) and representative photos (F) of lungs from WT and Ifnar1−/− mice (3 mice/group) after infection with 1×105 pfu PR8 virus and staining with H&E or MPO. Bars: 100 µm or 25 µm (enlarged pictures). IFN-I signaling is involved in leukocyte infiltration in the lung after influenza infection

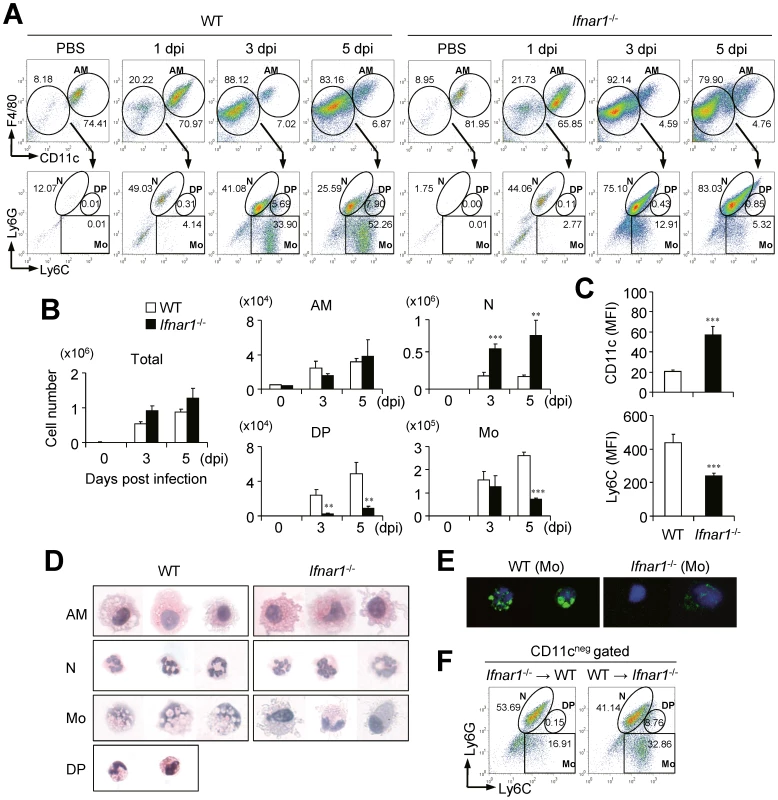

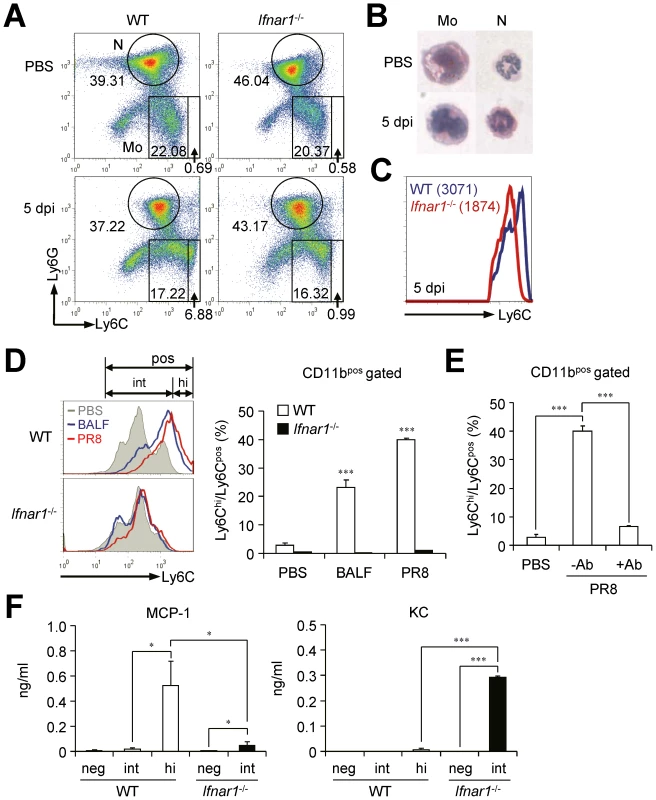

As Ifnar1−/− mice of B6 background exhibited severe pathology in terms of hyper secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and neutrophilia in lung after infection with influenza virus, we examined profiles of infiltrated cell populations in BALF in a time-dependent manner. From 1 dpi with influenza virus, predominant numbers of neutrophils (Ly6CintLy6G+) were infiltrated into the lung of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice (Figure 2A). Of note, the proportion (Figure 2A) and absolute numbers (Figure 2B) of infiltrated neutrophils in BALF were much higher in Ifnar1−/− mice than in WT mice. Furthermore, the numbers of neutrophils in WT mice peaked at 3 dpi and decreased at 5 dpi while neutrophils in Ifnar1−/− mice increased until 5 dpi, when mice began to die (Figure 2B). Meanwhile, monocytes (Ly6C+Ly6G−) were gradually infiltrated into the lung of WT mice in a time-dependent manner after influenza infection (Figure 2A and 2B). However, fewer monocytes were recruited into the lung of Ifnar1−/− mice than in WT mice (Figure 2A and 2B) and they were Ly6Cint rather than Ly6Chi (Figure 2C). Since Ly6Chi monocytes have similar phenotype to myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which expand during cancer, inflammation, and infection [24], we tested their ability to suppress CD4+ T cells. However, we did not find any evidence of CD4+ T cell suppression by Ly6Chi monocytes (Figure S1A). We next examined expression levels of co-stimulatory molecules, such as CD40, CD80, CD86, and MHCII, on surfaces of the respective cell populations, but overall these markers were not significantly different between cells isolated from WT and Ifnar1−/− mice (Figure S1B). We further analyzed surface expression of various markers on monocytes of infected WT and Ifnar1−/− mice (Figure S1C). Monocytes in the lung of infected WT and Ifnar1−/− mice expressed macrophage-related markers and they were negative for markers specific for dendritic cells, lymphocytes, and natural killer cells [25].

Fig. 2. Ifnar1−/− mice develop different cell population profiles in the lung after influenza infection.

Mice were infected i.n. with 1×105 pfu PR8 virus. (A) Cells were obtained from BALF at 1, 3, and 5 days post infection (dpi) and cellular compositions were determined by flow cytometry. AM, alveolar macrophages; N, neutrophils; DP, double-positive cells; Mo, monocytes. Numbers indicate cell population percentages within gates. (B) Absolute cell numbers of each subset in the BALF of mice pre and post infection. (C) CD11c and Ly6C expression levels in the monocytes isolated from the BALF of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice at 5 dpi. MFI; mean fluorescence intensity. Indicated cell subsets were isolated from the lung of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice at 5 dpi and stained with H&E (D) or Nile red (E) after cytospin. Original magnification ×40. (F) Recipient WT and Ifnar1−/− mice were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with bone marrow (BM) cells from Ifnar1−/− and WT mice, respectively. Cell populations in the BALF isolated from recipient WT and Ifnar1−/− mice at 3 dpi were analyzed. Values are mean + SD and results are representative of three independent experiments with n>5 for each group. Because MyD88 signaling cooperates with IFN-I in Ly6Chi monocyte recruitment in a Listeria monocytogenes infection model [26], we tested whether Toll-like receptor (TLR) or RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) signaling is involved in Ly6Chi monocyte regulation in our model. However, mice have defects in TLR (Myd88−/−Trif−/−) or RLR (Ips-1−/−) signaling normally generated Ly6Chi monocytes (Figure S2A). Although IPS-1 is involved in IFN-I expression, deletion of IPS-1 can be compensated by MyD88 signaling after influenza infection [27]. Indeed, Ips-1−/− mice produced IFN-α comparable to Ips-1+/+ mice (Figure S2B). Overall, direct engagement of IFN-I signaling through IFNAR but not TLR or RLR signaling seems to play a crucial role in Ly6Chi monocyte infiltration into the lung for host defense after influenza infection.

Ly6Cpos monocytes from influenza-infected lung of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice have different characteristic features

To assess the innate immune cells of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice in more detail, we next examined their morphologies (Figure 2D). Both AM and neutrophils in the lung seemed identical in WT and Ifnar1−/− mice except that some neutrophils from Ifnar1−/− mice exhibited larger size and had a more diffused nucleus, but monocytes were clearly different in the lung of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice after influenza infection. Interestingly, Ly6Chi monocytes morphologically resemble the foamy macrophages previously found in the lung of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin-infected mice [28]. To confirm this, we stained Ly6Cpos monocytes with Nile red, which mainly stains lipid body, and found that only Ly6Cpos monocytes isolated from the lung of WT mice were positively stained (Figure 2E). Next we generated BM chimeric mice (WT BM into Ifnar1−/− mice and vice versa) to confirm whether the defect in IFN-I signaling in the hematopoietic cell lineage can trigger the alteration of monocyte phenotypes in the lung of influenza-infected mice. As a result, Ly6Chi monocytes were generated in Ifnar1−/− recipient mice reconstituted with WT BM cells but were not detected in WT recipient mice that received Ifnar1−/− BM cells (Figure 2F). These suggest that IFN-I signaling in the hematopoietic cell lineage plays an indispensable role for differentiation of Ly6Chi monocytes against influenza infection.

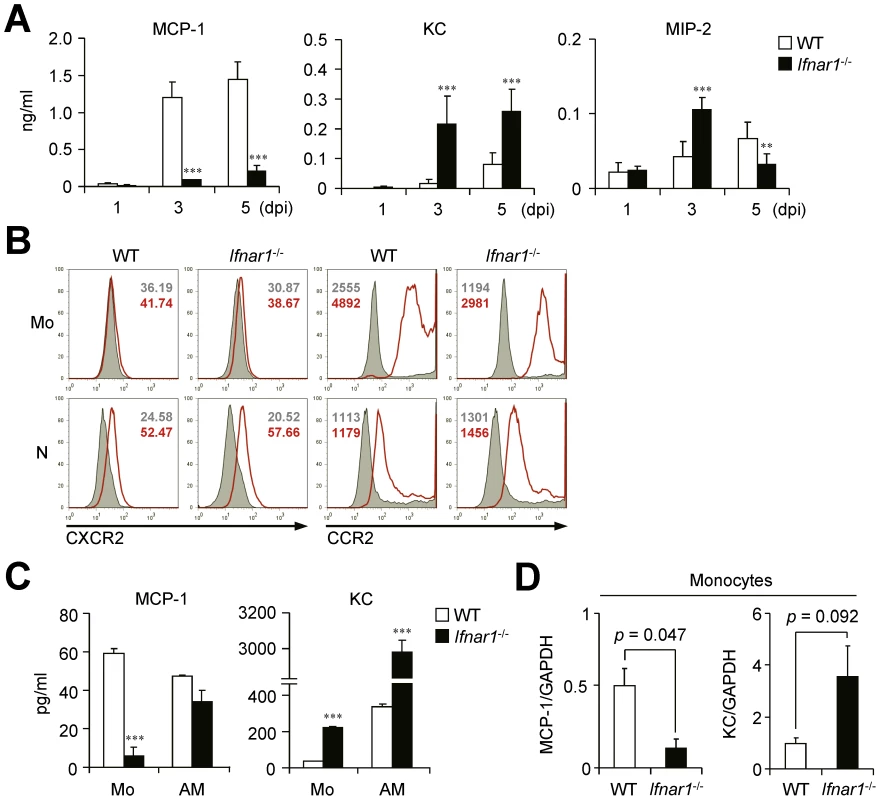

Monocytes from WT mice produce MCP-1 while those from Ifnar1−/− mice produce KC against influenza infection

We next measured the chemokines responsible for leukocyte migration against influenza infection in the BALF at different time points. Of note, expression levels of MCP-1 and KC, the main chemokines for CCR2 - and CXCR2-dependent cell recruitment, respectively [29], [30], were very different in the BALF of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice (Figure 3A). The Ifnar1−/− mice had significantly lower levels of MCP-1 than the WT mice but had predominant levels of KC at 3 and 5 dpi (Figure 3A). In addition, MIP-2, another well-known molecule for neutrophil recruitment [31], was significantly higher in Ifnar1−/− mice at 3 dpi (Figure 3A). Both Ly6Chi and Ly6Cint monocytes obtained from the lung of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice expressed CCR2 but not CXCR2 (Figure 3B), suggesting the critical role of MCP-1 for monocyte recruitment into influenza-infected lung.

Fig. 3. Ifnar1−/− mice produce significantly lower MCP-1 and higher KC than WT mice.

(A) Levels of MCP-1, KC, and MIP-2 were determined in the BALF of PR8 virus (1×105 pfu)-infected WT and Ifnar1−/− mice at 1, 3, and 5 dpi. Values are mean + SD and results are representative of three independent experiments with n>4 for each group. (B) Expression patterns of chemokine receptors, CXCR2 and CCR2, on monocytes (Mo) and neutrophils (N) were analyzed by flow cytometry. Histograms are representative of two independent experiments and numbers indicate MFI. (C) Monocytes (Mo) and alveolar macrophages (AM) were isolated using FACS Aria and plated onto 96-well plates. After culture for 4 h, MCP-1 and KC levels in the supernatants were analyzed. Data are representative of three independent experiments and values are mean + SD of three independently cultured wells. (D) mRNA expression levels of MCP-1 and KC were analyzed by gene chip data using monocytes from WT and Ifnar1−/− mice 5 dpi. The expression levels were normalized by GAPDH expression levels. Data are mean values of two independent experiments. To directly compare chemokine expression by individual cell populations, we sorted Ly6Cpos monocytes from influenza-infected lung of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice and then cultured them in vitro. Although both monocytes and AMs isolated from WT mice produced MCP-1 (Figure 3C), recovered Ly6Chi monocytes were quantitatively overwhelming over AMs (2.6×105 vs. 3.1×104 in BALF per mouse at 5 dpi) (Figure 2B). These findings suggest that Ly6Chi monocytes are the main producer of MCP-1 among leukocytes in WT mice after influenza infection. In contrast, in Ifnar1−/− mice, KC was highly produced by both Ly6Cint monocytes and AMs, but Ly6Cint monocytes secreted significantly less MCP-1 than WT Ly6Chi monocytes (Figure 3C). It is noteworthy that types of chemokines expressed in monocytes from WT and Ifnar1−/− mice were in complete contrast; gene expression profiles analyzed by gene chip experiments support these results (Figure 3D). Collectively, these data suggest that IFN-I is crucial for determining monocyte characteristics that dramatically influence chemokine production.

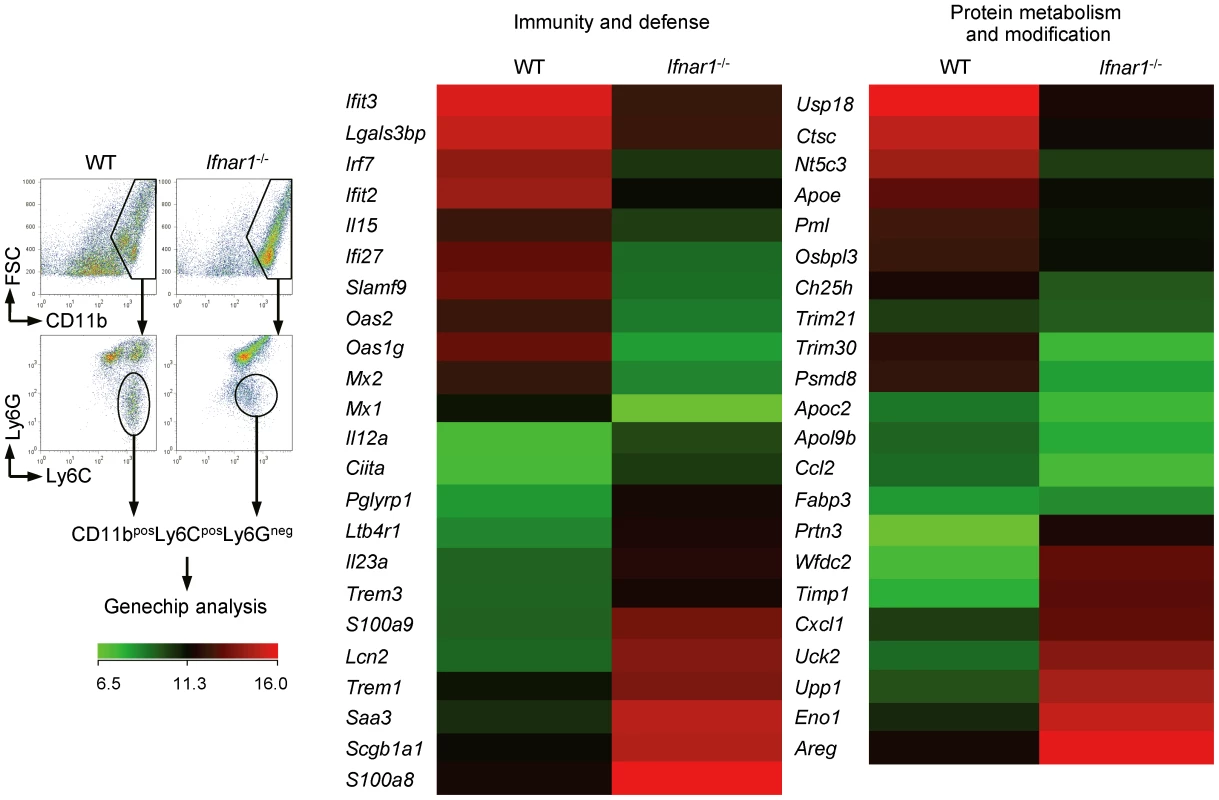

Monocytes from WT and Ifnar1−/− mice show different gene profiles

For macroscopic comparison between monocytes recruited in the lung of influenza-infected WT and Ifnar1−/− mice, we performed gene chip analysis (Figure 4). As expected, IFN-I-regulated genes (e.g., Mx, Oas, Irf, etc.) were significantly decreased in monocytes isolated from Ifnar1−/− mice. Of the genes elevated in Ly6Cint monocytes isolated from Ifnar1−/− mice, S100a8/S100a9 and Trem1 are associated with inflammatory responses in various diseases [32], [33]. In contrast, negative regulators of inflammation, Trim21 and Trim30 [34], [35], were up-regulated in Ly6Chi monocytes isolated from WT mice when compared to Ly6Cint monocytes from Ifnar1−/− mice. These inflammation-biased gene expressions by Ly6Cint monocytes may explain the higher susceptibility of Ifnar1−/− mice to influenza infection. Ly6Chi monocytes from WT mice were also superior in expressing genes involved in lipid metabolism (e.g., Apoe, Apoc2, etc.). Interestingly, the 1918 pandemic influenza virus was found to block lipid metabolism as part of its evasion strategy against antiviral responses [36]. Furthermore, influenza infection causes prominent inflammation in Apoe−/− mice [37], indicating that a defect in lipid metabolism in Ifnar1−/− mice might contribute to worsen inflammation. Collectively, we confirmed that monocytes from WT and Ifnar1−/− mice have significantly different characteristics and that lack of IFN-I signaling changes gene expression bias to augment inflammation.

Fig. 4. Monocytes of Ifnar1−/− mice express different patterns of genes.

WT and Ifnar1−/− mice were infected i.n. with 1×105 pfu PR8 and monocytes were sorted. Total RNA was extracted and gene expression profiles were analyzed on gene chip. Data are representative of two independent experiments. IFN-I signaling is required for Ly6Chi monocyte generation

Since the different gene expression patterns in Ly6Cpos monocytes of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice after influenza infection can be ascribable to altered monocyte differentiation from their precursors, we next analyzed BM where hematopoiesis occurs and provides common monocyte precursors. The proportion of Ly6Chi monocytes was significantly lower (6.9±1.9 vs. 1.0±0.3%) in the BM of Ifnar1−/− mice than in WT mice, while the proportion of Ly6Cint monocytes was comparable to WT mice (17.2±0.6 vs. 16.3±1.5%) at 5 dpi (Figure 5A). However, there were no significant differences in cell morphology between WT and Ifnar1−/− mice (data not shown), and Ly6Cpos monocytes of WT mice did not show lipid bodies unlike Ly6Chi monocytes in the lung post influenza infection (Figure 5B). Because we found higher levels of Ly6C expression in BM monocytes from WT than in Ifnar1−/− mice at 5 dpi (Figure 5C), we further assessed whether IFN-I signaling can directly affect differentiation of naïve BM cells in vitro. When BM cells were stimulated with WT BALF collected at 5 dpi or directly infected with influenza virus, WT BM cells were able to differentiate into Ly6Chi monocytes but Ifnar1−/− BM could not (Figure 5D). To confirm that this maturation defect of Ly6Chi monocytes from Ifnar1−/− BM is due to lack of IFN-I signaling, we co-cultured PR8-infected WT BM cells with or without anti-IFNAR1 blocking antibody. When treated with anti-IFNAR1 antibody, WT BM cells failed to differentiate into Ly6Chi monocytes (Figure 5E). Importantly, these Ly6Chi monocytes derived from WT BM stimulated by influenza virus dominantly produced MCP-1 when compared to Ly6Cint monocytes derived from WT or Ifnar1−/− BM, while Ifnar1−/− Ly6Cint monocytes produced robust KC instead (Figure 5F). From this observation, we suggest that absence of Ly6Chi cells in lung of Ifnar1−/− mice results from failure in differentiation of their precursors due to lack of IFN-I signaling.

Fig. 5. Ifnar1−/− bone marrow (BM) cells are unable to differentiate into MCP-1-producing Ly6Chi monocytes.

(A) BM cells were isolated from WT and Ifnar1−/− mice pre- and post-influenza infection and analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Monocytes (Mo) and neutrophils (N) were isolated, cytospun, and stained by H&E (×40). (C) MFI of Ly6C expression of monocytes in the BM of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice following influenza infection (1×105 pfu). Mean values are in parenthesis. (D) BM cells from naïve WT and Ifnar1−/− mice were prepared and stimulated in vitro with BALF from PR8 virus (1×105 pfu)-infected WT mice or with PR8 virus (0.5 multiplicity of infection) alone. After 5 days of culture, subsets of Ly6Chi and Ly6Cint were counted and the percentage of Ly6Chi among Ly6Cpos was determined. (E) After BM cells were prepared from naïve WT mice, cells were infected with PR8 virus and cultured for 5 days with/without anti-IFNAR1 blocking Ab (100 ng/ml). (F) BM cells infected with PR8 and cultured in vitro for 5 days. Cultured cells were further sorted into Ly6Cneg, Ly6Cint, and Ly6Chi. Each cell subset was cultured in vitro for 4 h and chemokine levels in the supernatant were analyzed. Values are mean + SD and data are representative of at least two independent experiments. IFN-I signaling on hematopoietic cells is required to resist influenza infection

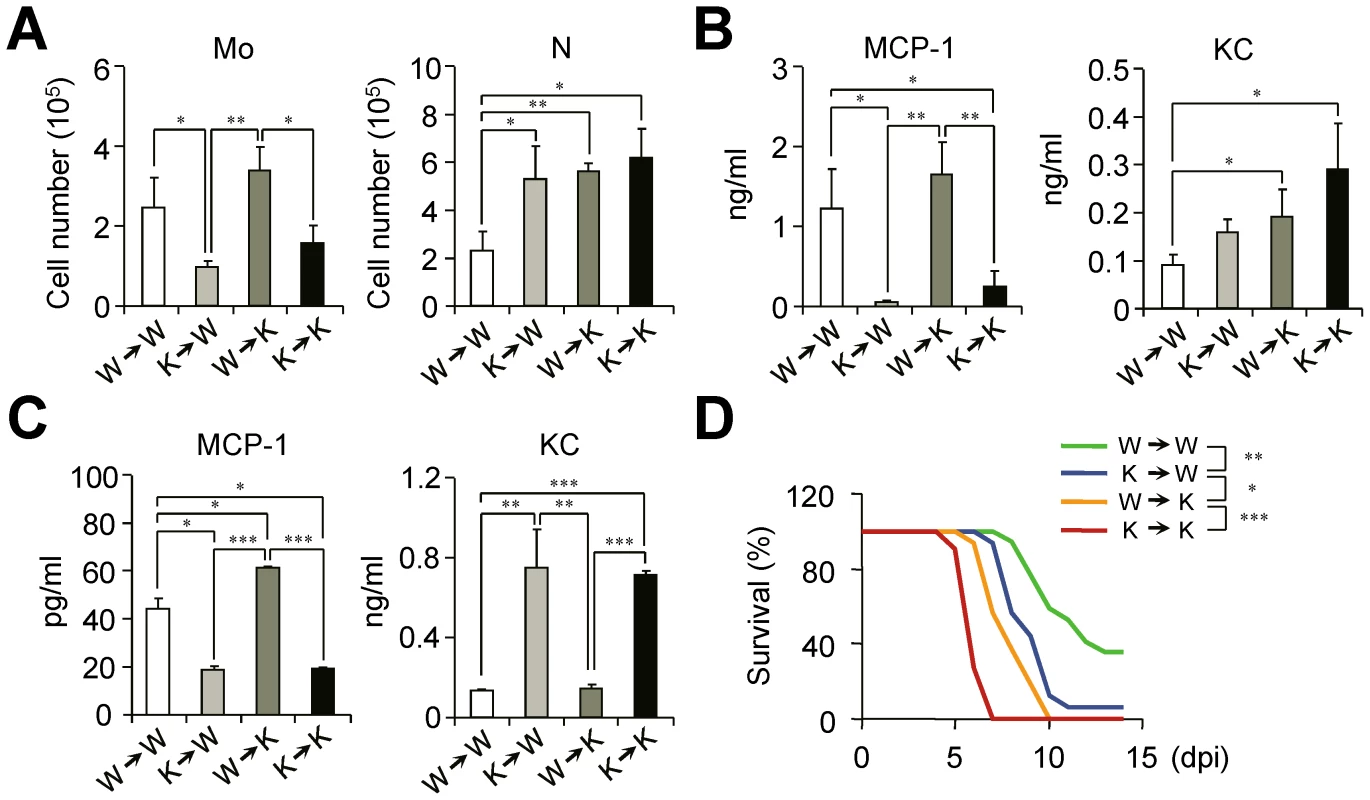

To clarify the origin and roles of monocytes in depth in the absence of IFN-I signaling, we used BM chimeric mice. Ifnar1−/− recipient mice reconstituted with WT BM cells (W→K) have significantly more Ly6Chi monocytes than K→K (Ifnar1−/− donor and Ifnar1−/− recipient) mice (Figure 6A). Concomitantly, the MCP-1 level in the BALF was correlated with Ly6Chi monocytes (i.e., W→W and W→K) after influenza infection (Figure 6B). The fact that K→W mice elicited no higher level of MCP-1 than found in the BALF of K→K mice after influenza infection suggests that radio-resistant WT parenchymal cells do not play a major role in MCP-1 production (Figure 6B). In addition, Ly6Chi monocytes derived from W→W and W→K mice produce MCP-1 efficiently following in vitro culture (Figure 6C), clearly indicating that Ly6Chi monocytes derived from WT BM mice exclusively produce MCP-1 in response to influenza infection. To the contrary, although we saw a distinct correlation between KC production with IFN-I deficiency in monocytes (Figure 6C), W→K chimera mice still had significantly augmented KC in BALF even with high levels of MCP-1 and Ly6Chi monocytes (Figure 6B). Thus it seems likely that the complete regulation of KC also needs the IFN-I-dependent signaling pathway in cells other than monocytes or there may be another regulator for KC in the absence of IFN-I signaling.

Fig. 6. IFN-I signaling on hematopoietic cell lineage helps protect mice from lethal influenza infection.

Bone marrow (BM) cells from naïve WT (W) or Ifnar1−/− (K) mice were grafted to lethally irradiated WT or Ifnar1−/− recipient mice. (A–C) Sets of BM grafted mice were challenged with influenza PR8 virus (1×105 pfu) and analyzed at 3 dpi. (A) Number of monocytes (Mo) and neutrophils (N) were determined. (B) Expression levels of MCP-1 and KC were measured in BALF. (C) Monocytes in the lung were pooled and cultured for 4 h to measure chemokine production in vitro. Values are mean + SD of triplicate experiments with n>4 for each group. (D) Mice were challenged with lethal dose of influenza PR8 (1×105 pfu) and survival was monitored for 2 weeks. W→W (n = 17), K→W (n = 16), W→K (n = 16), and K→K (n = 11). Data were pooled from three independent experiments. Finally, we sought to find the relationships between the defect in Ly6Chi monocyte generation and the susceptibility of chimeric mice against influenza infection. The loss of intrinsic Ly6Chi monocytes in K→W mice resulted in the increased susceptibility of mice against influenza infection as compared with W→W mice (Figure 6D). In addition, the W→K chimera mice showed less susceptibility to influenza infection than did K→K mice with the restoration of Ly6Chi monocytes (Figure 6D). To see whether neutrophils can augment inflammation and tissue damage, we isolated neutrophils from infected Ifnar1−/− mice and transferred them to naïve WT mice (Figure S3A). Then effect of neutrophil transfer on the lung inflammation was observed without additional infection or any treatment. Histologically, recipient WT mice had destruction in epithelial layers and showed inflammatory lesions while PBS-treated mice did not at 2 days after transfer (Figure S3B). Inflammatory cytokines in the BALF were also induced after neutrophil transfer, indicating activated neutrophil itself can cause inflammation (Figure S3C). Thus, we suggest that excess neutrophils can worsen disease even if there are good reasons for recruitment after virus infection. Even though parenchymal cells appear to maintain host defense, our data clearly show the importance of IFN-I signaling in hematopoietic cells in protection against influenza infection.

Discussion

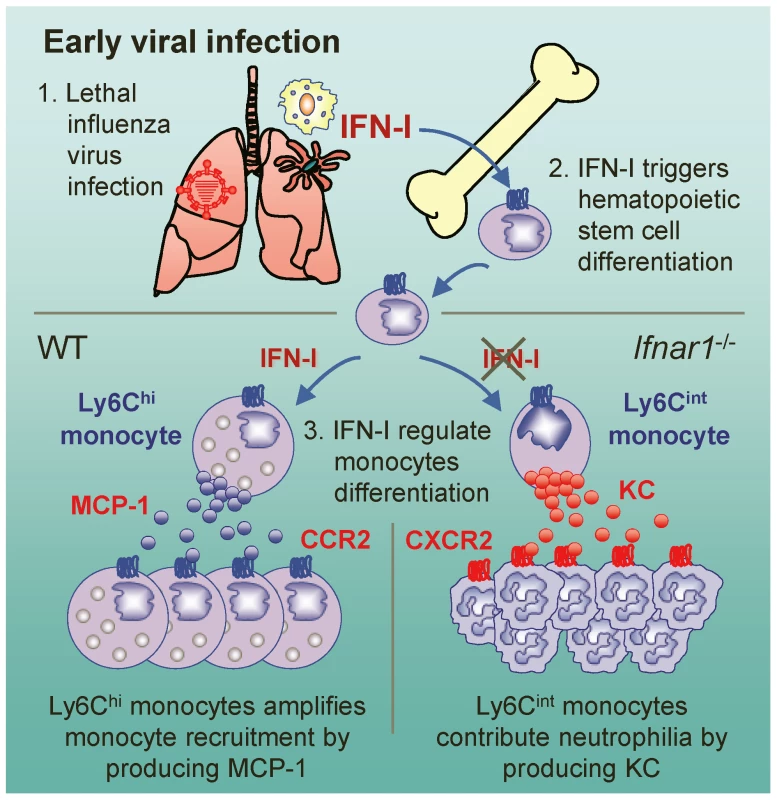

Despite numerous previous studies focused on the direct antiviral nature of IFN-I, the data we present here suggest that IFN-I-dependent generation of Ly6Chi monocytes after influenza infection might be critical for the attenuation of neutrophil infiltration and hence prevent severe tissue damage caused by uncontrolled inflammation (Figure 7). Ly6Chi monocytes in the lung were previously reported as TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells [38] or inflammatory monocytes [12], [39]. In our observations, however, Ly6Chi monocytes were closest in morphology to the highly vacuolated foamy macrophages, which were found in granulomas in the lung of Mycobacterium bovis-infected mice [28].

Fig. 7. Suggested model for the role of IFN-I on monocyte and neutrophil regulation.

After influenza infection, hematopoietic stem cell differentiation might be triggered by IFN-I and then MCP-1-producing Ly6Chi monocytes are recruited to the lung. In the absence of IFN-I signaling, Ly6Cint monocytes are alternatively generated and produce KC, which might in turn aggravates lung pathology by attracting excess neutrophils to lung. Previously, it was proposed that there is no up-regulation of MCP-1 in the absence of IFN-I signaling; as a consequence, without up-regulation there will be fewer Ly6Chi monocytes in various tissues [26], [40], [41]. We show here that only mice reconstituted with WT BM cells (W→W and W→K), but not with Ifnar1−/− BM cells (K→K and K→W), generated Ly6Chi monocytes and produced high amounts of MCP-1 in the BALF against influenza infection. Further, BM cells from Ifnar1−/− mice were unable to differentiate into MCP-1-producing Ly6Chi monocytes by in vitro stimulation, indicating that IFN-I signaling on hematopoietic cells is required for differentiating Ly6Chi monocytes. Our findings are the first to delineate a notion that MCP-1 is mainly produced by Ly6Chi monocytes, which are regulated by IFN-I against influenza infection. Additionally, it seems plausible that AMs and other cells (e.g., pulmonary epithelial cells) contribute to produce MCP-1 for initial monocyte recruitment before Ly6Chi monocytes are heavily recruited after virus infection.

MCP-1 is a chemokine that has great importance in CCR2-mediated monocyte recruitment after lung inflammation [42]. Although other chemokines such as MCP-2, MCP-3, and MCP-4 also contribute to attract CCR2-expressing monocytes after influenza infection, overexpression of MCP-1 results in elevated monocyte recruitment [12]. In this regard, MCP-1-deficient mice show significantly reduced macrophage infiltration [43]. Moreover, MCP-1 is capable of activating AM [44] and of blocking MCP-1-augmented damage on epithelial cells after influenza infection [45]. Thus, Ly6Chi monocytes might play an important role for host defense against influenza infection by mediating MCP-1.

Unlike MCP-1 whose level was dramatically decreased in Ifnar1−/− mice, KC was significantly increased after influenza infection. We observed that W→K and K→W chimeric mice produced intermediate KC when compared to W→W and K→K mice, suggesting that KC can be produced by both radio-sensitive and -resistant cells. AMs, which produced KC in vitro, seemed especially important producers as did radio-resistant cells (e.g., epithelial cells) as proposed by others [46]. Since KC with MCP-1 is reversely correlated in BALF and culture supernatant with monocytes from the lung of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice, further studies are needed to elucidate a putative role of IFN-I-dependent Ly6Chi monocytes on neutrophil regulation as well as possible feedback regulation of KC by MCP-1 production.

Previously it was proposed that Ly6Cint monocytes were converted from Ly6Chi monocytes after migration to the site of inflammation [41]. Those activated forms of Ly6Cint monocytes were characterized by high CX3CR1 but no CCR2 expression [47]. In our study, however, Ly6Cint monocytes generated in influenza-infected Ifnar1−/− mice expressed high levels of CCR2. Thus, it seems likely that Ly6Cint monocytes in Ifnar1−/− mice could be an alternative to Ly6Chi monocytes generated under IFN-I-deficient conditions rather than a different cell subset of Ly6C expressing monocytes.

It has been reported that the spleen also stores monocytes and these cells deploy to inflammatory sites to regulate inflammation [25]. To address this issue, we compared characteristics of monocytes in the spleen before and after influenza infection (Figure S4A). Interestingly, Ly6C expression level in the monocytes was much lower in the spleen of Ifnar1−/− mice than in WT mice in the steady-state condition (Figure S4B). The number of Ly6Chi monocytes stored in the spleen was also decreased in Ifnar1−/− mice compared to WT mice, whereas the number of neutrophils was comparable before influenza infection (Figure S4C). We speculate that the reduced numbers of WT and Ifnar1−/− monocytes after influenza infection in the spleen may indicate the spleen is a reservoir that provides monocytes to the lung.

After finding that IFN-I signaling is involved in Ly6Chi generation, we next sought to clarify the relationships between the defect in Ly6Chi monocytes and susceptibility to influenza infection. Viral titer in lethally infected lung culminated around 2 dpi and continuously decreased. Although Ifnar1−/− mice were intact in viral clearance and showed similar viral burden at 5 dpi compared to WT mice, they developed severe inflammation and consequently higher susceptibility. In previous studies, attenuated inflammation provided resistance to influenza infection even with increased viral burden [12], [48]. These findings indicate that virus-induced inflammation could be more critical than viral burden itself in the course of influenza pathology. Thus, we suggest that severe and acute lung inflammation in Ifnar1−/− mice, especially with uncontrolled accumulation of neutrophils due to massive KC production, contributes to increased susceptibility of those mice to influenza infection.

Accumulation of neutrophils is one of the most important events during acute respiratory distress syndrome [49]. Neutrophils are generally thought to aggravate lung injury after influenza infection [50], especially in severe infections such as those we assessed in our study. To address the contribution of neutrophils to virus-induced airway hyperresponsiveness as proposed by others [51], [52], we used CXCR2 blocking Ab and CXCR2 antagonist SB225002 [29], [53]. These materials partially dampened neutrophil responses when moderate or low doses of influenza were given, but they could not efficiently block massive influxes of neutrophils after lethal influenza infection in Ifnar1−/− mice (data not shown). However, we found that neutrophils can augment inflammation and tissue damage (Figure S3); also loss of Ly6Chi monocytes in K→W mice augmented neutrophil infiltration compared to W→W mice, indicating the balance between neutrophils and Ly6Chi monocytes are reversely correlated. Moreover, when chimeric mice were lethally challenged, susceptibility of these mice was directly proportional to neutrophil numbers. Our data suggest that uncontrolled neutrophils may aggravate the outcome of excess inflammation against virus infection. Even though neutrophils are thought to augment inflammation and make disease worse, we still must consider their protective role. We showed Ifnar1−/− mice had higher peak virus titer but were able to successfully control virus replication. Regarding previous report that neutrophils can limit virus replication [19], it seems plausible that excessively recruited neutrophils may contribute to observed virus elimination in Ifnar1−/− mice. However, several lines of evidence lead us to speculate that destructive trait of neutrophils dominated over their positive role during severe and acute viral pneumonia.

IFN-I is used to treat several diseases, including hepatitis B virus infection [54], chronic hepatitis C virus infection [55], and multiple sclerosis [56]. Since IFN-I, which is produced by virus infection, can migrate and affect BM to switch on the production of functional monocytes [57], therapeutically administrated IFN-I can communicate with BM leukocytes. This possibility suggests that clinical uses of IFN-I should be investigated in terms of modified patient leukocyte profiles, especially in those receiving prolonged IFN-I therapy.

Influenza virus NS1 protein antagonizes IFN-I responses, and influenza virus lacking the NS1 gene replicates inefficiently in tissue culture and normal egg culture conditions and shows attenuated phenotype in WT mice; however, it replicates far more efficiently in IFN-deficient Vero cells and pathogenic in Stat1−/− mice [58]. In the clinical context, it is important to note that the NS1 protein of highly pathogenic viruses, such as H5N1 avian influenza and the 1918 pandemic influenza virus, has stronger suppressive effects on IFN-I [59], [60]. These viruses also are involved in more acute recruitment of neutrophils, severe lung injury, and aggressive inflammatory cytokine production (so-called cytokine storm) as found in Ifnar1−/− mice [20], [61], [62]. Thus our results in Ifnar1−/− mice merit further study to help understand the pathogenesis of highly pathogenic influenza virus.

Our findings show the specific function of IFN-I on Ly6Chi monocyte differentiation and address the impact of this event in the lung after influenza infection. Further studies on regulation of neutrophils and Ly6Chi monocytes by potential pandemic virus may provide insight that will prove useful for development of novel therapeutic targets.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the International Vaccine Institute (Approval No: PN 1003), and all experiments were carried out in strict accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources Commission on Life Sciences National Research Council, USA. All experiments were performed under anesthesia with a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (20 mg/kg), and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Mice and virus infection

C57BL/6 (B6) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Orient Bio Inc., Sungnam, Korea). Ifnar1−/− mice (B6 background) were purchased from B&K Universal Ltd. (Hull, U.K.). To generate chimeric mice, naïve B6 and Ifnar1−/− recipient mice were lethally irradiated with 960 rad and donor BM cells (1×107) were reconstituted by intraperitoneal injection. Chimeric mice were maintained for at least 8 weeks and chimerism was assessed by IFNAR1 expression on Gr-1+ cells in serum. Mice were infected intranasally (20 µl) with influenza A/PR/8/34 (PR8, H1N1) virus after anesthesia.

Sample preparation

To obtain BALF, tracheas were cannulated after exsanguination and lungs were washed with 1 ml of PBS. BALF samples were centrifuged (800×g, 5 min) to isolate cells and supernatants were centrifuged again (13,000×g, 1 min) to completely remove remaining cells. BM cells obtained from femurs and tibias and red blood cells were removed before analysis. In some experiments, cells were cultured in vitro (1×105 cells/well) for 4 h in RPMI (Gibco, Auckland, New Zealand) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) to measure chemokines. Cultured cells were removed from supernatants by centrifugation (2,300×g, 3 min) and supernatants were used for further analysis.

Virus plaque titration

Total lung was removed and homogenized to prepare lung extracts in 1 ml of PBS (pH 7.4). Confluent Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were washed with MEM (Gibco) once and treated with virus for 30 min at room temperature. After a wash with MEM, the plate was overlaid with MEM containing 1% low-melting-point agarose and 10 µg/ml of trypsin and incubated at 37°C for 3 days.

Measurement of total protein in BALF

We measured total protein in BALF samples by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cytokine and chemokine detection

The levels of MCP-1, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ were measured by Mouse Inflammatory Cytometric Bead Array Kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The levels of KC, MIP-2, and IP-10 were measured by DuoSet Mouse ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Histology

Lungs were removed from naïve or infected B6 and Ifnar1−/− mice and washed using PBS before being fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 1 h at 4°C. The tissues were embedded in paraffin and stained with H&E. To detect MPO expression, tissues were dehydrated in sucrose solutions (10, 20, and 30%) after fixation and embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetec, Tokyo, Japan). Cryo sections (5 µm) were fixed in ice-cold acetone and blocked with FcRII/III mAb (2.4G2; BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) in PBS. Then, tissues were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-MPO (2D4; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) for confocal microscopy. Histopathological score was assessed by a pathologist using a blind test. As previously described [63], we used a scoring system of 20 points to evaluate the level of lung tissue destruction, epithelial cell layer damage, polymorphonuclear cell infiltration into the site, and alveolitis.

Flow cytometry

Cells were collected from lung or BM and stained with the following antibodies: CD11c (HL3), CD11b (M1/70), Ly6C (AL-21), Ly6G (1A8), all purchased from BD Pharmingen; F4/80 (BM8) from eBioscience (San Diego, CA); and CXCR2 (242216) from R&D Systems; CCR2 (MC-21) was obtained from Prof. Matthias Mack (University of Regensburg, Germany). The cells were read by FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and data were analyzed by FlowJo 7.2.5 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). In some experiments, cells were sorted using FACSAria (BD Biosciences). Cell populations in the lung were classified using these surface markers: AM (CD11chiF4/80+), DP (Ly6C+Ly6G+), neutrophils (Ly6CintLy6G+), Ly6Chi monocytes (Ly6ChiLy6G−), and Ly6Cint monocytes (Ly6CintLy6G−). For analysis of BM Ly6C/Ly6G-positive cells, CD11b+ cells gated out and further divided depending on their Ly6C and Ly6G expressions.

Cytospin and Nile red staining

To cytospin cells on Cytoslide (Thermo Scientific, Asheville, NC), sorted cells were centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 10 min using CytoSpin 4 Cytocentrifuge (Thermo Scientific). Then cells were fixed and stained with H&E. For Nile red staining, stock solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; 0.1 mg/ml in acetone) was diluted 1∶5,000 in PBS and cells were stained for 30 min at 37°C. Samples were washed twice with Ca2+/Mg2+-free HBSS and cytospun. Then fixed specimens (3.7% formaldehyde) were stained with DAPI and washed twice before mounting.

BM cell in vitro stimulation

Cells were prepared from BM of naïve WT and Ifnar1−/− mice. After being washed twice with RPMI, cells (1×107) were either infected with PR8 (5×106 pfu/3 ml) virus or mock infected for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were washed in RPMI twice and cultured for 5 days in a 1∶1 mixture of PBS and RPMI containing 10% FBS in culture dishes (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). In some groups, we used BALF from infected WT mice for stimulation. To inhibit IFN-I signaling, we used anti-IFNAR1 blocking antibody (100 ng/ml; MAR1-5A3; BioLegend, San Diego, CA).

Microarray analysis

Monocytes were sorted from lung of WT and Ifnar1−/− mice at 5 dpi. RNA from each cell subset was extracted by RNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA microarray analysis was performed using a MouseRef-8 v2 Expression Beadchip Kit (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Statistics

We used a paired two-sample t-test for analysis, except for survival data for which we used Kaplan-Meier analysis. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 were considered significant.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. JewellNA

VaghefiN

MertzSE

AkterP

PeeblesRSJr

2007 Differential type I interferon induction by respiratory syncytial virus and influenza a virus in vivo. J Virol 81 9790 9800

2. KumagaiY

TakeuchiO

KatoH

KumarH

MatsuiK

2007 Alveolar macrophages are the primary interferon-alpha producer in pulmonary infection with RNA viruses. Immunity 27 240 252

3. SadlerAJ

WilliamsBR

2008 Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat Rev Immunol 8 559 568

4. DerSD

LauAS

1995 Involvement of the double-stranded-RNA-dependent kinase PKR in interferon expression and interferon-mediated antiviral activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92 8841 8845

5. MinJY

KrugRM

2006 The primary function of RNA binding by the influenza A virus NS1 protein in infected cells: Inhibiting the 2′-5′ oligo (A) synthetase/RNase L pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 7100 7105

6. DittmannJ

StertzS

GrimmD

SteelJ

Garcia-SastreA

2008 Influenza A virus strains differ in sensitivity to the antiviral action of Mx-GTPase. J Virol 82 3624 3631

7. Garcia-SastreA

2004 Identification and characterization of viral antagonists of type I interferon in negative-strand RNA viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 283 249 280

8. StetsonDB

MedzhitovR

2006 Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity 25 373 381

9. Garcia-SastreA

2006 Antiviral response in pandemic influenza viruses. Emerg Infect Dis 12 44 47

10. KoernerI

KochsG

KalinkeU

WeissS

StaeheliP

2007 Protective role of beta interferon in host defense against influenza A virus. J Virol 81 2025 2030

11. SzretterKJ

GangappaS

BelserJA

ZengH

ChenH

2009 Early control of H5N1 influenza virus replication by the type I interferon response in mice. J Virol 83 5825 5834

12. LinKL

SuzukiY

NakanoH

RamsburgE

GunnMD

2008 CCR2+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells and exudate macrophages produce influenza-induced pulmonary immune pathology and mortality. J Immunol 180 2562 2572

13. SerbinaNV

PamerEG

2006 Monocyte emigration from bone marrow during bacterial infection requires signals mediated by chemokine receptor CCR2. Nat Immunol 7 311 317

14. EssersMA

OffnerS

Blanco-BoseWE

WaiblerZ

KalinkeU

2009 IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature 458 904 908

15. SatoT

OnaiN

YoshiharaH

AraiF

SudaT

2009 Interferon regulatory factor-2 protects quiescent hematopoietic stem cells from type I interferon-dependent exhaustion. Nat Med 15 696 700

16. MumyKL

McCormickBA

2009 The role of neutrophils in the event of intestinal inflammation. Curr Opin Pharmacol 9 697 701

17. TateMD

BrooksAG

ReadingPC

2008 The role of neutrophils in the upper and lower respiratory tract during influenza virus infection of mice. Respir Res 9 57

18. TateMD

DengYM

JonesJE

AndersonGP

BrooksAG

2009 Neutrophils ameliorate lung injury and the development of severe disease during influenza infection. J Immunol 183 7441 7450

19. TumpeyTM

Garcia-SastreA

TaubenbergerJK

PaleseP

SwayneDE

2005 Pathogenicity of influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus: functional roles of alveolar macrophages and neutrophils in limiting virus replication and mortality in mice. J Virol 79 14933 14944

20. PerroneLA

PlowdenJK

Garcia-SastreA

KatzJM

TumpeyTM

2008 H5N1 and 1918 pandemic influenza virus infection results in early and excessive infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils in the lungs of mice. PLoS Pathog 4 e1000115

21. TumpeyTM

BaslerCF

AguilarPV

ZengH

SolorzanoA

2005 Characterization of the reconstructed 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic virus. Science 310 77 80

22. Garcia-SastreA

DurbinRK

ZhengH

PaleseP

GertnerR

1998 The role of interferon in influenza virus tissue tropism. J Virol 72 8550 8558

23. PriceGE

Gaszewska-MastarlarzA

MoskophidisD

2000 The role of alpha/beta and gamma interferons in development of immunity to influenza A virus in mice. J Virol 74 3996 4003

24. GabrilovichDI

NagarajS

2009 Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 9 162 174

25. SwirskiFK

NahrendorfM

EtzrodtM

WildgruberM

Cortez-RetamozoV

2009 Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science 325 612 616

26. JiaT

LeinerI

DorotheeG

BrandlK

PamerEG

2009 MyD88 and Type I interferon receptor-mediated chemokine induction and monocyte recruitment during Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol 183 1271 1278

27. KoyamaS

IshiiKJ

KumarH

TanimotoT

CobanC

2007 Differential role of TLR - and RLR-signaling in the immune responses to influenza A virus infection and vaccination. J Immunol 179 4711 4720

28. D'AvilaH

MeloRC

ParreiraGG

Werneck-BarrosoE

Castro-Faria-NetoHC

2006 Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin induces TLR2-mediated formation of lipid bodies: intracellular domains for eicosanoid synthesis in vivo. J Immunol 176 3087 3097

29. BelperioJA

KeaneMP

BurdickMD

LondheV

XueYY

2002 Critical role for CXCR2 and CXCR2 ligands during the pathogenesis of ventilator-induced lung injury. J Clin Invest 110 1703 1716

30. DawsonTC

BeckMA

KuzielWA

HendersonF

MaedaN

2000 Contrasting effects of CCR5 and CCR2 deficiency in the pulmonary inflammatory response to influenza A virus. Am J Pathol 156 1951 1959

31. SakaiS

KawamataH

MantaniN

KogureT

ShimadaY

2000 Therapeutic effect of anti-macrophage inflammatory protein 2 antibody on influenza virus-induced pneumonia in mice. J Virol 74 2472 2476

32. BouchonA

FacchettiF

WeigandMA

ColonnaM

2001 TREM-1 amplifies inflammation and is a crucial mediator of septic shock. Nature 410 1103 1107

33. FoellD

WittkowskiH

VoglT

RothJ

2007 S100 proteins expressed in phagocytes: a novel group of damage-associated molecular pattern molecules. J Leukoc Biol 81 28 37

34. EspinosaA

DardalhonV

BraunerS

AmbrosiA

HiggsR

2009 Loss of the lupus autoantigen Ro52/Trim21 induces tissue inflammation and systemic autoimmunity by disregulating the IL-23-Th17 pathway. J Exp Med 206 1661 1671

35. ShiM

DengW

BiE

MaoK

JiY

2008 TRIM30 alpha negatively regulates TLR-mediated NF-kappa B activation by targeting TAB2 and TAB3 for degradation. Nat Immunol 9 369 377

36. BillharzR

ZengH

ProllSC

KorthMJ

LedererS

2009 The NS1 protein of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus blocks host interferon and lipid metabolism pathways. J Virol 83 10557 10570

37. NaghaviM

WydeP

LitovskyS

MadjidM

AkhtarA

2003 Influenza infection exerts prominent inflammatory and thrombotic effects on the atherosclerotic plaques of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation 107 762 768

38. AldridgeJRJr

MoseleyCE

BoltzDA

NegovetichNJ

ReynoldsC

2009 TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells are the necessary evil of lethal influenza virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 5306 5311

39. HohlTM

RiveraA

LipumaL

GallegosA

ShiC

2009 Inflammatory monocytes facilitate adaptive CD4 T cell responses during respiratory fungal infection. Cell Host Microbe 6 470 481

40. CraneMJ

Hokeness-AntonelliKL

Salazar-MatherTP

2009 Regulation of inflammatory monocyte/macrophage recruitment from the bone marrow during murine cytomegalovirus infection: role for type I interferons in localized induction of CCR2 ligands. J Immunol 183 2810 2817

41. LeePY

LiY

KumagaiY

XuY

WeinsteinJS

2009 Type I interferon modulates monocyte recruitment and maturation in chronic inflammation. Am J Pathol 175 2023 2033

42. RoseCEJr

SungSS

FuSM

2003 Significant involvement of CCL2 (MCP-1) in inflammatory disorders of the lung. Microcirculation 10 273 288

43. DessingMC

van der SluijsKF

FlorquinS

van der PollT

2007 Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 contributes to an adequate immune response in influenza pneumonia. Clin Immunol 125 328 336

44. KannanS

HuangH

SeegerD

AudetA

ChenY

2009 Alveolar epithelial type II cells activate alveolar macrophages and mitigate P. Aeruginosa infection. PLoS One 4 e4891

45. NarasarajuT

NgHH

PhoonMC

ChowVT

2009 MCP-1 Antibody Treatment Enhances Damage and Impedes Repair of the Alveolar Epithelium in Influenza Pneumonitis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 42 732 743

46. RaoustE

BalloyV

Garcia-VerdugoI

TouquiL

RamphalR

2009 Pseudomonas aeruginosa LPS or flagellin are sufficient to activate TLR-dependent signaling in murine alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells. PLoS One 4 e7259

47. GeissmannF

JungS

LittmanDR

2003 Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity 19 71 82

48. HeroldS

SteinmuellerM

von WulffenW

CakarovaL

PintoR

2008 Lung epithelial apoptosis in influenza virus pneumonia: the role of macrophage-expressed TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. J Exp Med 205 3065 3077

49. WareLB

MatthayMA

2000 The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 342 1334 1349

50. WareingMD

SheaAL

InglisCA

DiasPB

SarawarSR

2007 CXCR2 is required for neutrophil recruitment to the lung during influenza virus infection, but is not essential for viral clearance. Viral Immunol 20 369 378

51. MillerAL

StrieterRM

GruberAD

HoSB

LukacsNW

2003 CXCR2 regulates respiratory syncytial virus-induced airway hyperreactivity and mucus overproduction. J Immunol 170 3348 3356

52. NagarkarDR

WangQ

ShimJ

ZhaoY

TsaiWC

2009 CXCR2 is required for neutrophilic airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in a mouse model of human rhinovirus infection. J Immunol 183 6698 6707

53. BentoAF

LeiteDF

ClaudinoRF

HaraDB

LealPC

2008 The selective nonpeptide CXCR2 antagonist SB225002 ameliorates acute experimental colitis in mice. J Leukoc Biol 84 1213 1221

54. CraxiA

Di BonaD

CammaC

2003 Interferon-alpha for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 39 Suppl 1 S99 105

55. HoofnagleJH

SeeffLB

2006 Peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 355 2444 2451

56. KapposL

FreedmanMS

PolmanCH

EdanG

HartungHP

2007 Effect of early versus delayed interferon beta-1b treatment on disability after a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis: a 3-year follow-up analysis of the BENEFIT study. Lancet 370 389 397

57. HermeshT

MoltedoB

MoranTM

LopezCB

2010 Antiviral instruction of bone marrow leukocytes during respiratory viral infections. Cell Host Microbe 7 343 353

58. Garcia-SastreA

EgorovA

MatassovD

BrandtS

LevyDE

1998 Influenza A virus lacking the NS1 gene replicates in interferon-deficient systems. Virology 252 324 330

59. GeissGK

SalvatoreM

TumpeyTM

CarterVS

WangX

2002 Cellular transcriptional profiling in influenza A virus-infected lung epithelial cells: the role of the nonstructural NS1 protein in the evasion of the host innate defense and its potential contribution to pandemic influenza. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 10736 10741

60. SeoSH

HoffmannE

WebsterRG

2002 Lethal H5N1 influenza viruses escape host anti-viral cytokine responses. Nat Med 8 950 954

61. CillonizC

ShinyaK

PengX

KorthMJ

ProllSC

2009 Lethal influenza virus infection in macaques is associated with early dysregulation of inflammatory related genes. PLoS Pathog 5 e1000604

62. KobasaD

JonesSM

ShinyaK

KashJC

CoppsJ

2007 Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus. Nature 445 319 323

63. ShimDH

ChangSY

ParkSM

JangH

CarbisR

2007 Immunogenicity and protective efficacy offered by a ribosomal-based vaccine from Shigella flexneri 2a. Vaccine 25 4828 4836

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiológia Infekčné lekárstvo Laboratórium

Článek Compensatory Evolution of Mutations Restores the Fitness Cost Imposed by β-Lactam Resistance inČlánek The C-Terminal Domain of the Arabinosyltransferase EmbC Is a Lectin-Like Carbohydrate Binding ModuleČlánek A Viral microRNA Cluster Strongly Potentiates the Transforming Properties of a Human Herpesvirus

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2011 Číslo 2- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Očkování proti virové hemoragické horečce Ebola experimentální vakcínou rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP

- Koronavirus hýbe světem: Víte jak se chránit a jak postupovat v případě podezření?

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- A Fresh Look at the Origin of , the Most Malignant Malaria Agent

- In Situ Photodegradation of Incorporated Polyanion Does Not Alter Prion Infectivity

- Highly Efficient Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification

- Positive Signature-Tagged Mutagenesis in : Tracking Patho-Adaptive Mutations Promoting Airways Chronic Infection

- Charge-Surrounded Pockets and Electrostatic Interactions with Small Ions Modulate the Activity of Retroviral Fusion Proteins

- Whole-Body Analysis of a Viral Infection: Vascular Endothelium is a Primary Target of Infectious Hematopoietic Necrosis Virus in Zebrafish Larvae

- Inhibition of Nox2 Oxidase Activity Ameliorates Influenza A Virus-Induced Lung Inflammation

- STAT2 Mediates Innate Immunity to Dengue Virus in the Absence of STAT1 via the Type I Interferon Receptor

- Uropathogenic P and Type 1 Fimbriae Act in Synergy in a Living Host to Facilitate Renal Colonization Leading to Nephron Obstruction

- Elite Suppressors Harbor Low Levels of Integrated HIV DNA and High Levels of 2-LTR Circular HIV DNA Compared to HIV+ Patients On and Off HAART

- DC-SIGN Mediated Sphingomyelinase-Activation and Ceramide Generation Is Essential for Enhancement of Viral Uptake in Dendritic Cells

- Short-Lived IFN-γ Effector Responses, but Long-Lived IL-10 Memory Responses, to Malaria in an Area of Low Malaria Endemicity

- Induces T-Cell Lymphoma and Systemic Inflammation

- The C-Terminus of RON2 Provides the Crucial Link between AMA1 and the Host-Associated Invasion Complex

- Critical Role of the Virus-Encoded MicroRNA-155 Ortholog in the Induction of Marek's Disease Lymphomas

- Type I Interferon Signaling Regulates Ly6C Monocytes and Neutrophils during Acute Viral Pneumonia in Mice

- Atypical/Nor98 Scrapie Infectivity in Sheep Peripheral Tissues

- Innate Sensing of HIV-Infected Cells

- BosR (BB0647) Controls the RpoN-RpoS Regulatory Pathway and Virulence Expression in by a Novel DNA-Binding Mechanism

- Compensatory Evolution of Mutations Restores the Fitness Cost Imposed by β-Lactam Resistance in

- Expression of Genes Involves Exchange of the Histone Variant H2A.Z at the Promoter

- The RON2-AMA1 Interaction is a Critical Step in Moving Junction-Dependent Invasion by Apicomplexan Parasites

- Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 3C Facilitates G1-S Transition by Stabilizing and Enhancing the Function of Cyclin D1

- Transcription and Translation Products of the Cytolysin Gene on the Mobile Genetic Element SCC Regulate Virulence

- Phosphatidylinositol 3-Monophosphate Is Involved in Apicoplast Biogenesis

- The Rubella Virus Capsid Is an Anti-Apoptotic Protein that Attenuates the Pore-Forming Ability of Bax

- Episomal Viral cDNAs Identify a Reservoir That Fuels Viral Rebound after Treatment Interruption and That Contributes to Treatment Failure

- Genetic Mapping Identifies Novel Highly Protective Antigens for an Apicomplexan Parasite

- Relationship between Functional Profile of HIV-1 Specific CD8 T Cells and Epitope Variability with the Selection of Escape Mutants in Acute HIV-1 Infection

- The Genotype of Early-Transmitting HIV gp120s Promotes αβ –Reactivity, Revealing αβ/CD4 T cells As Key Targets in Mucosal Transmission

- Small Molecule Inhibitors of RnpA Alter Cellular mRNA Turnover, Exhibit Antimicrobial Activity, and Attenuate Pathogenesis

- The bZIP Transcription Factor MoAP1 Mediates the Oxidative Stress Response and Is Critical for Pathogenicity of the Rice Blast Fungus

- Entrapment of Viral Capsids in Nuclear PML Cages Is an Intrinsic Antiviral Host Defense against Varicella-Zoster Virus

- NS2 Protein of Hepatitis C Virus Interacts with Structural and Non-Structural Proteins towards Virus Assembly

- Measles Outbreak in Africa—Is There a Link to the HIV-1 Epidemic?

- New Models of Microsporidiosis: Infections in Zebrafish, , and Honey Bee

- The C-Terminal Domain of the Arabinosyltransferase EmbC Is a Lectin-Like Carbohydrate Binding Module

- A Viral microRNA Cluster Strongly Potentiates the Transforming Properties of a Human Herpesvirus

- Infections in Cells: Transcriptomic Characterization of a Novel Host-Symbiont Interaction

- Secreted Bacterial Effectors That Inhibit Host Protein Synthesis Are Critical for Induction of the Innate Immune Response to Virulent

- Genital Tract Sequestration of SIV following Acute Infection

- Functional Coupling between HIV-1 Integrase and the SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodeling Complex for Efficient Integration into Stable Nucleosomes

- DNA Damage and Reactive Nitrogen Species are Barriers to Colonization of the Infant Mouse Intestine

- The ESCRT-0 Component HRS is Required for HIV-1 Vpu-Mediated BST-2/Tetherin Down-Regulation

- Targeted Disruption of : Invasion of Erythrocytes by Using an Alternative Py235 Erythrocyte Binding Protein

- Trivalent Adenovirus Type 5 HIV Recombinant Vaccine Primes for Modest Cytotoxic Capacity That Is Greatest in Humans with Protective HLA Class I Alleles

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Genetic Mapping Identifies Novel Highly Protective Antigens for an Apicomplexan Parasite

- Type I Interferon Signaling Regulates Ly6C Monocytes and Neutrophils during Acute Viral Pneumonia in Mice

- Infections in Cells: Transcriptomic Characterization of a Novel Host-Symbiont Interaction

- The ESCRT-0 Component HRS is Required for HIV-1 Vpu-Mediated BST-2/Tetherin Down-Regulation

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy