-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Ethanol Stimulates WspR-Controlled Biofilm Formation as Part of a Cyclic Relationship Involving Phenazines

In many human infections, several species of microbes are often present. This is typically the case with the disease cystic fibrosis, characterized by thick mucus in the lungs that is colonized by bacteria and fungi. Here, we show evidence that interactions between the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the fungus Candida albicans result in attributes of infection that are worse for the human host. We found that ethanol, such as that produced by C. albicans, causes increased levels of a signaling molecule in P. aeruginosa that promotes biofilm formation. Biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa is associated with infections that are more difficult to treat. Ethanol stimulated P. aeruginosa colonization of plastic surfaces and airway cells, and we identified components of this mechanism. Fungally-produced ethanol also changes the spectrum of phenazine toxins produced by P. aeruginosa, and phenazines are associated with worse lung function in people with cystic fibrosis. In light of the fact that phenazines interact with C. albicans to promote ethanol production, we propose a positive feedback loop between C. albicans and P. aeruginosa that contributes to worse disease. Our findings could have implications for the study and treatment of multi-species infections.

Published in the journal: Ethanol Stimulates WspR-Controlled Biofilm Formation as Part of a Cyclic Relationship Involving Phenazines. PLoS Pathog 10(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004480

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004480Summary

In many human infections, several species of microbes are often present. This is typically the case with the disease cystic fibrosis, characterized by thick mucus in the lungs that is colonized by bacteria and fungi. Here, we show evidence that interactions between the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the fungus Candida albicans result in attributes of infection that are worse for the human host. We found that ethanol, such as that produced by C. albicans, causes increased levels of a signaling molecule in P. aeruginosa that promotes biofilm formation. Biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa is associated with infections that are more difficult to treat. Ethanol stimulated P. aeruginosa colonization of plastic surfaces and airway cells, and we identified components of this mechanism. Fungally-produced ethanol also changes the spectrum of phenazine toxins produced by P. aeruginosa, and phenazines are associated with worse lung function in people with cystic fibrosis. In light of the fact that phenazines interact with C. albicans to promote ethanol production, we propose a positive feedback loop between C. albicans and P. aeruginosa that contributes to worse disease. Our findings could have implications for the study and treatment of multi-species infections.

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen capable of causing severe nosocomial infections and infections in immunocompromised patients. P. aeruginosa is a common pathogen of individuals with cystic fibrosis (CF), a genetic disease that is caused by a mutation in the gene coding for the CFTR ion transporter and strongly associated with chronic, recalcitrant lung infections. Altered CFTR function leads to a fluid imbalance that results in thick, sticky mucus in the lungs that is difficult to clear, thus creating a hospitable environment for microbial growth, biofilm formation, and persistence. While P. aeruginosa is a common microbe in the CF lung, it is rarely the only microbe present [1]–[5]. Co-infections of P. aeruginosa with other bacterial and fungal species are common, and there is a need to understand how these complex multi-species infections impact disease course and treatability. For example, the presence of the fungus Candida albicans correlates with more frequent exacerbations and a more rapid loss of lung function in CF patients [6], [7]. Additional studies are needed to determine if the presence of the fungus contributes to more severe disease.

Published reports strongly suggest that in the CF lung, P. aeruginosa forms biofilms [8], described as hearty aggregations of cells in a sessile group lifestyle that includes extracellular matrix comprised of proteins, membrane vesicles, DNA, and exopolysaccharides. A biofilm existence provides many advantages to P. aeruginosa including increased antibiotic tolerance [9], [10]. As with many Gram-negative species, P. aeruginosa biofilm formation is positively regulated by the secondary signaling molecule cyclic-di-GMP (c-di-GMP) [11]. C-di-GMP is formed from two molecules of GTP by diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) and its levels inversely correlate to motility. High levels of c-di-GMP promote biofilm formation in a number of ways including via increased matrix production and decreased flagellar motility [12]–[14].

P. aeruginosa also produces a class of redox-active virulence factors called phenazines. In CF sputum, the phenazines pyocyanin (PYO) and phenazine-1-carboxylate (PCA) are found in micromolar (5–80 µM) concentrations, and their levels are inversely correlated with lung function [15]. Phenazines play a role in the relationships between P. aeruginosa and eukaryotic cells. Several studies have shown how phenazines can negatively affect mammalian physiology [16], [17]. In addition, phenazines impact different fungi, including C. albicans. At high concentrations, phenazines are toxic to C. albicans, and lower concentrations of phenazines reduce fungal respiration and impair growth as hyphae [18]. Phenazines figure prominently in shaping the chemical ecology within mixed-species communities. For example, when exposed to low concentrations of phenazines, C. albicans increases the production of fermentation products such as ethanol by 3 to 5 fold [18]. Furthermore, P. aeruginosa-C. albicans co-cultures form red derivatives of 5-methyl-phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (5MPCA) that accumulate within fungal cells [19].

In the present study, we show that ethanol produced by C. albicans stimulated P. aeruginosa biofilm formation and altered phenazine production. Ethanol caused a decrease in surface motility in both strains PA14 and PAO1 concomitant with a stimulation in levels of c-di-GMP, a second messenger nucleotide that promotes biofilm formation. Through a genetic screen, we found that the diguanylate cyclase WspR, a response regulator of the Wsp chemosensory system, was required for this response. Elements upstream and downstream of WspR signaling were required for the ethanol response. Ethanol no longer stimulated biofilm formation in a mutant lacking WspA, the membrane-localized sensor methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein (MCP) that is involved in the activation of WspR [20]. In addition, an intact Pel exopolysaccharide biosynthesis pathway, known to be stimulated by c-di-GMP derived from the Wsp pathway [21], [22], was also required for ethanol stimulation of biofilm formation. The effects were observed on both abiotic surfaces and a cell culture model for P. aeruginosa and P. aeruginosa-C. albicans airway colonization. We found that both exogenous and fungally-produced ethanol enhanced the production of two phenazine derivatives known for their antifungal activity [19], [23], 5MPCA and phenazine-1-carboxamide (PCN), through a Wsp-independent pathway and independent of ethanol catabolism. Because phenazines stimulate fungal ethanol production [18], we present evidence for a signaling cycle that helps drive this polymicrobial interaction.

Results

Ethanol stimulates biofilm formation and suppresses swarming in P. aeruginosa strain PA14

Our previously reported findings show that P. aeruginosa produces higher levels of two phenazines, PYO and 5MPCA [24], [25], when cultured with C. albicans and that phenazines stimulate C. albicans ethanol production [18]. Thus, we sought to determine how fungally-derived ethanol affects P. aeruginosa. A concentration of 1% ethanol (v/v) was chosen for these studies based on the detection of comparable levels of ethanol in C. albicans supernatants from cultures grown with phenazines [18]. The presence of 1% ethanol in the culture medium did not affect P. aeruginosa growth in minimal M63 medium with glucose (Fig. S1) or LB (doubling time of 36±2 min in LB versus 39±2 min in LB with ethanol), or on solid LB medium (Fig. S1 inset) except that the final culture yield in M63 was slightly higher in cultures amended with ethanol (Fig. S1).

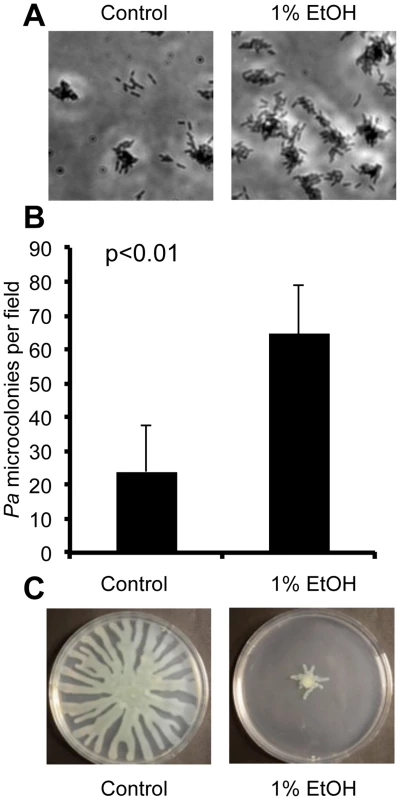

When we performed a microscopic analysis of the effects of ethanol on P. aeruginosa strain PAO1, we observed a significant increase in attachment of cells to the bottom of a titer dish well within 1 h (15±5 cells per field in vehicle treated compared to 31±6 cells per field in cultures with ethanol, p<0.01) and development of microcolonies was strongly enhanced (Fig. 1A). Ethanol also promoted an increase in the number of attached cells and microcolonies in cultures of another P. aeruginosa strain, PA14 (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Ethanol represses swarming and stimulates biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa.

A. P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 attachment to the bottom of a polystyrene plastic well after 6 hours in medium with and without 1% ethanol (EtOH). B. P. aeruginosa strain PA14 attachment to plastic as assessed by quantification of microcolonies per field in wells containing medium with or without ethanol for 7 h. Error bars represent the standard deviation (p<0.01 as determined by a student's t-test, N = 12). C. P. aeruginosa strain PA14 swarming in the absence and presence of 1% ethanol. Images are representative of results in more than ten independent experiments. Using two assays that assess biofilm-related phenotypes (swarming motility and twitching motility), we sought to gain additional insight into how ethanol impacted biofilm formation. Our initial studies focused on strain PA14. We found that ethanol repressed swarming motility, a behavior that is inversely correlated with biofilm formation (Fig. 1C). Ethanol did not affect type IV-pili-dependent twitching motility, a form of movement that is required for microcolony formation in biofilms on plastic (Fig. S2B) [26].

Ethanol catabolism is not necessary for the inhibition of swarming

Because P. aeruginosa can catabolize ethanol [27], we sought to determine if ethanol consumption contributed to the repression of swarming motility. P. aeruginosa first oxidizes ethanol to acetaldehyde by an ethanol dehydrogenase, ExaA, which requires the cofactor PQQ (pyrroloquinoline quinone) [27]. Acetaldehyde is further oxidized to acetate by an NAD+ dependent acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ExaC), and the acetate is subsequently oxidized to acetyl-CoA by AcsA [28]. We retrieved the exaA::TnM, pqqB::TnM, and acsA::TnM mutants predicted to be defective in ethanol catabolism from the P. aeruginosa strain PA14 NR transposon library [29] and confirmed the transposon insertion sites by PCR (see Materials and Methods for more detail). As predicted, none of these mutants grew with ethanol as the sole carbon source, and growth on glucose was unaffected (Fig. S3A).

When we used these mutants in the swarm assay, we found no difference in the effects of ethanol on these three ethanol catabolism mutants in comparison to the wild-type parental strain (Fig. S3B) indicating that ethanol catabolism was not required for the ethanol response. Furthermore, other carbon sources such as glycerol, another fungal fermentation product, or choline, another two-carbon alcohol degraded by a PQQ-dependent enzyme, did not inhibit swarming motility (Fig. S4).

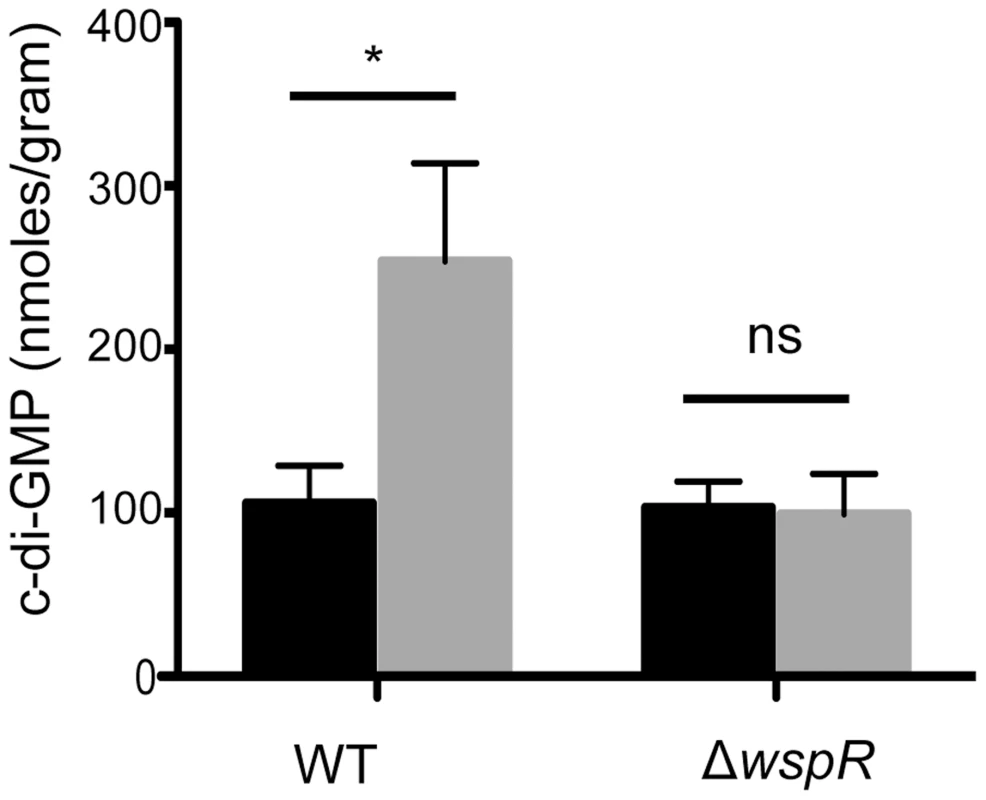

Ethanol increases c-di-GMP levels through WspR

Ethanol stimulated attachment and biofilm formation on plastic and inhibited swarming motility (Fig. 1). These two phenotypes are positively and negatively regulated by levels of the second messenger molecule c-di-GMP [30]. Thus, we measured intracellular levels of this dinucleotide in P. aeruginosa strain PA14 cells grown on swarm plates with or without 1% ethanol for 16.5 h as described previously. We found a 2.4-fold increase in c-di-GMP levels in cells exposed to ethanol (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Ethanol increases c-di-GMP levels in P. aeruginosa strain PA14 WT but not in a ΔwspR mutant.

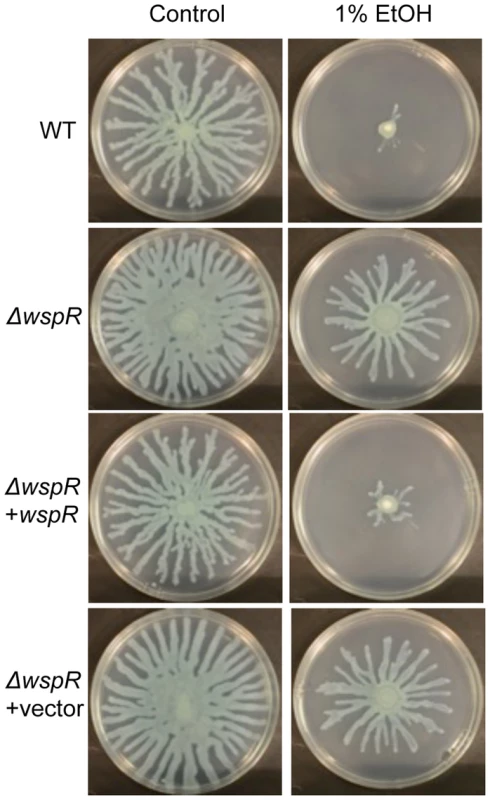

c-di-GMP levels from cultures grown on swarm plates without (black) or with 1% ethanol (grey) were measured by LC-MS. Error bars represent one standard deviation (*,p<0.05, N = 5); ns, not significant). To identify the enzyme(s) responsible for this increase, we screened a collection of 31 P. aeruginosa strain PA14 mutants [31] defective in different genes predicted to encode proteins that may modulate c-di-GMP levels based on the detection of a DGC and/or an EAL domain [22], [31]. We found that one mutant, ΔwspR, was strikingly resistant to the repression of swarming by ethanol (Fig. 3). As expected, this mutant also had a slight hyperswarming phenotype when compared to the wild type in control conditions [31], and both phenotypes were complemented by the wild-type wspR allele on an arabinose-inducible plasmid when grown in the presence of 0.02% arabinose (Fig. 3). The empty vector (EV) control exhibited a swarming pattern comparable to that of the ΔwspR mutant.

Fig. 3. P. aeruginosa ΔwspR shows loss of swarm repression in the presence of ethanol.

P. aeruginosa strain PA14 WT, ΔwspR, and ΔwspR strains containing either plasmid-borne wspR or the empty vector were analyzed on swarm medium with and without 1% ethanol (EtOH) and with 0.02% arabinose (to induce wspR expression in the complemented strain). Images are representative of at least 5 experiments for each strain. WspR is a response regulator with a GGDEF domain [32], which is associated with diguanylate cyclase activity [20]. Consistent with the observation that ΔwspR continued to swarm on medium with ethanol, c-di-GMP levels were not different between cultures with and without ethanol in the ΔwspR background (Fig. 2). These data suggest that WspR activity, and thus c-di-GMP levels, are enhanced by ethanol.

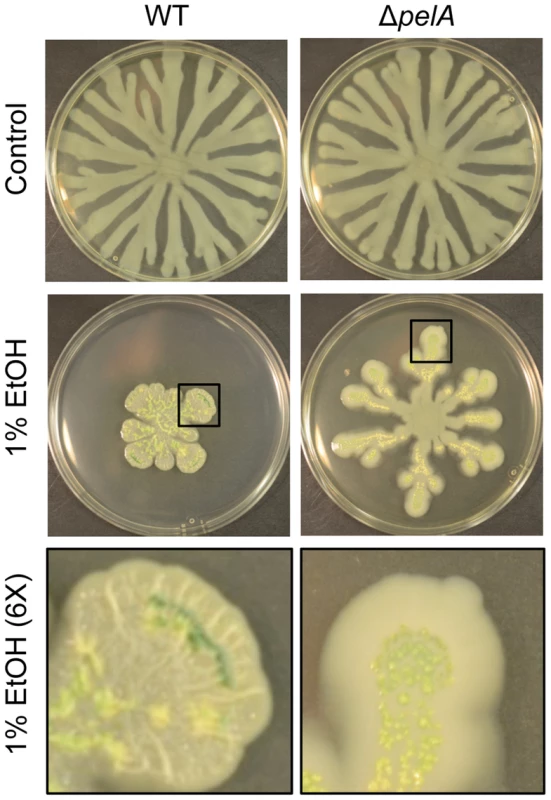

WspR is known to regulate the production of the Pel polysaccharide [21], [22], and production of Pel is associated with colony wrinkling and biofilm formation [33]. After 72 hours on swarm plates, we also observed that ethanol strongly promoted colony wrinkling while the addition of equivalent amounts of other carbon sources, such as glycerol or choline, did not have this effect. Furthermore, the colony wrinkling induced by ethanol was less apparent in a ΔwspR strain (not shown) and completely absent in a strain lacking pelA, an enzyme required for Pel biosynthesis (Fig. 4). The ΔpelA mutant, like the ΔwspR mutant, continued to swarm in the presence of ethanol (Fig. 4) suggesting that the repression of swarming in the presence of ethanol was, at least in part, due to increased Pel production.

Fig. 4. Pel production in response to ethanol.

P. aeruginosa strain PA14 WT and ΔpelA swarm colonies on medium with and without 1% ethanol (EtOH) after 72 h. The bottom panels show an enlarged view (6×) of swarm tendrils of the colonies grown with ethanol (indicated by a black box). Enlarged images demonstrate the yellow/green PCN crystals in both strains and colony wrinkles in the WT that form upon growth on ethanol. Ethanol induces c-di-GMP signaling in P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 through WspA and WspR

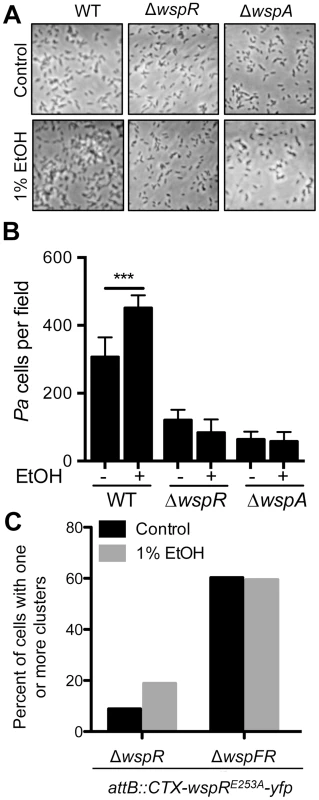

As we found that ethanol stimulated biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa wild-type strains PA14 and PAO1 (Fig. 1) and that WspR mediated the ethanol effect in strain PA14, we also examined the role of WspR in the ethanol response in strain PAO1. As shown above, PAO1 wild-type cells had increased early attachment and subsequent microcolony formation on plastic when ethanol was added to the medium (Fig. 5). Consistent with our model that ethanol is acting through WspR, ethanol did not stimulate surface colonization in the PAO1 ΔwspR mutant (Fig. 5). We also examined the ethanol-responsive phenotype for P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 ΔwspA, which lacks the membrane bound receptor that is the most upstream element described in the Wsp system [20]. Like ΔwspR, ΔwspA did not show increased attachment to plastic upon the addition of ethanol (Fig. 5) suggesting that both the MCP sensor and the WspR response regulator were required for the response to ethanol. Ethanol also promoted colony wrinkling in strain PAO1, as was observed in strain PA14, consistent with the prediction that increased WspR activity would lead to increased matrix production. Enhanced wrinkling with ethanol was shown most clearly for both strains in non-motile (flgK) mutants which formed colonies of similar size regardless of the presence of ethanol (Fig. S5). Because strain PAO1 WT does not swarm robustly in control conditions, the effects of ethanol on swarming in strain PAO1 were not quantified.

Fig. 5. Ethanol acts through the Wsp system.

A. Attachment of P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 WT, ΔwspR and ΔwspA mutants to the bottom of a polystyrene dish during growth in M63 medium with glucose and casamino acids, and with vehicle (Control) or with 1% ethanol for 6 hours. B. The number of cells per field for each condition was enumerated. Images and data are representative of results from more than three separate experiments. Significance determination was based on an ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons test for each intrastrain comparison; ***, P<0.001. C. ΔwspR and ΔwspFR strains expressing WspR-E253A-YFP were grown without and with 1% EtOH, and the number of cells with fluorescent clusters were counted out of a total of approximately 100 cells examined per condition across two experiments. Ethanol promotes WspR clustering and a functional Wsp system is required for this effect

Previous studies have shown that the fluorescently-tagged WspR protein forms intracellular clusters when in its active phosphorylated form upon incubation of cells on an agar surface, and cluster formation is positively correlated with WspR activity [20]. To complement the mutant analyses, we determined if ethanol also promoted WspR-YFP clustering, and if known components of the WspR activation system were required for WspR stimulation by ethanol. To facilitate these analyses, we used the WspR variant WspRE253A-YFP, which forms larger clusters that are more easily visualized [34]. In these studies, we observed a two fold increase in WspR clustering in the presence of ethanol (Fig. 5C). To determine if WspF, a methylesterase that negatively regulates WspR activity [21], was involved in the regulation of WspR in response to ethanol, we also assessed WspR clustering in a ΔwspF background where WspR is constitutively active. In ΔwspF, WspR clustering was higher than in the wspF+ reference strain, and WspR clustering was not further stimulated by ethanol, lending support for the model that ethanol was acting through the Wsp system and not through an independent pathway for WspR activation.

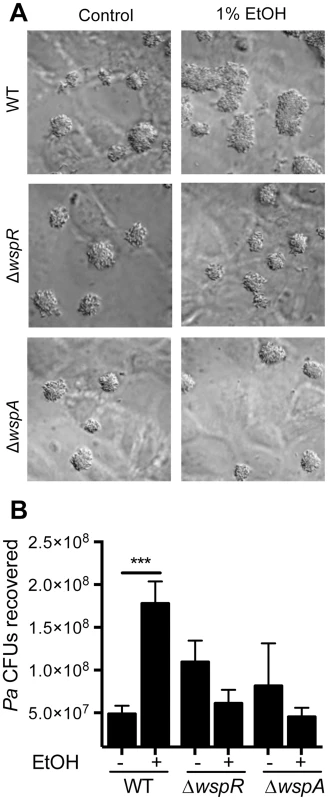

C. albicans and ethanol promote airway epithelial cell monolayer colonization

To understand the effects of ethanol on P. aeruginosa in a well-established CF-relevant disease model, we studied the effects of ethanol on P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 in the context of bronchial epithelial cells with the most common CF genotype (homozygous CFTRΔF508) [35], [36]. We cultured P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 with the epithelial cells in medium without and with 1% ethanol, and observed an obvious enhancement in the size of biofilm microcolonies (Fig. 6A) and a 2.2-fold increase in colony forming units (CFUs) on the airway cells with ethanol (Fig. 6B). When the same experiment was performed with the ΔwspR or ΔwspA mutants, no stimulation by ethanol was observed. Ethanol alone did not impact epithelial cell viability as measured by an LDH release assay (9.44%±0.98 LDH release for control and 10.47%±1.2 LDH release with ethanol, N = 3) and other studies have also found these concentrations of ethanol to be well below those that cause overt toxicity to epithelial cells or disruption of epithelial barrier integrity [37], [38].

Fig. 6. Ethanol significantly increases P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 WT biofilm formation on airway cells.

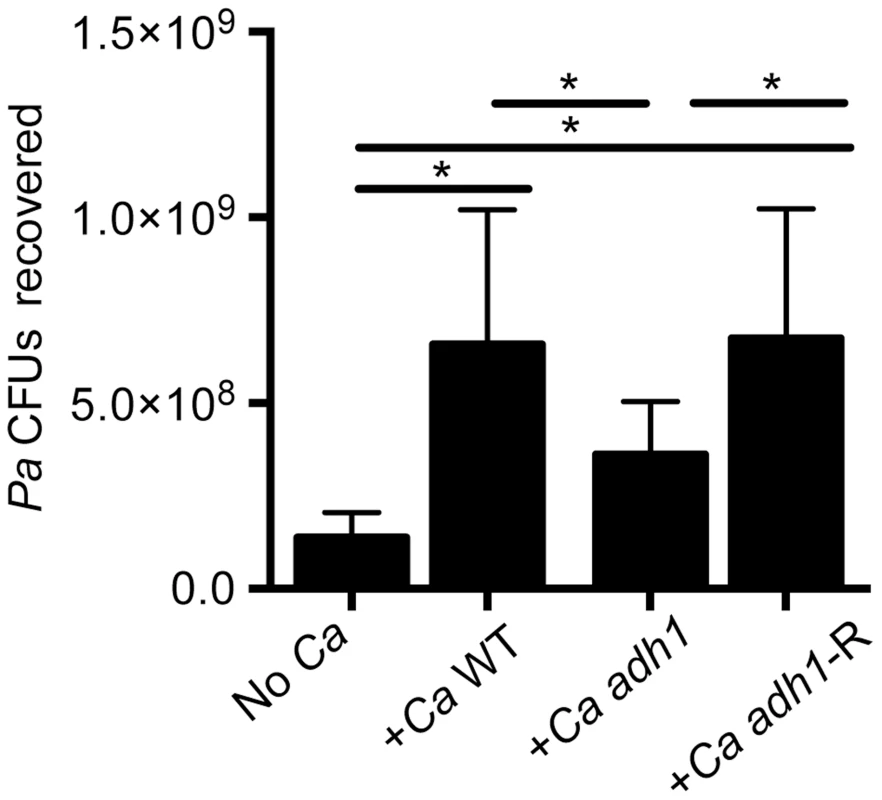

A. PAO1 WT, ΔwspR or ΔwspA were co-cultured with a monolayer of ΔF508 CFTR-CFBE cells at an MOI of 30∶1 in medium with or without 1% ethanol and imaged after 6 h. Pictures are representative of at least 3 separate experiments with similar results. B. The number of CFUs from cultures determined as described above. Significance determination was based on an ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons test for each intrastrain comparison; ***, P<0.001. Error bars represent one standard deviation. When P. aeruginosa PAO1 and C. albicans were co-inoculated into epithelial cell co-cultures, 4.7-fold more P. aeruginosa CFUs were found to be associated with the monolayer after 6 h (Fig. 7). To determine if C. albicans-derived ethanol contributed to the enhanced colonization by P. aeruginosa in the presence of C. albicans, we used a C. albicans adh1/adh1 mutant that produced lower levels of ethanol. We constructed the adh1 null strain and its complemented derivative, and confirmed that the absence of ADH1 caused a reduction in ethanol by HPLC analysis of culture supernatants, a finding consistent with previously published work [39]. When P. aeruginosa was co-cultured with the C. albicans adh1/adh1 strain, there was a significant decrease in P. aeruginosa CFUs recovered, and this defect was corrected upon complementation with the ADH1 gene in trans. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the stimulation of colonization by wild-type or adh1/adh1 mutant C. albicans in the ΔwspR or ΔwspA backgrounds (Fig. S6). Together, these data strongly suggest that C. albicans-produced ethanol promotes P. aeruginosa colonization of both abiotic and biotic surfaces through activation of the Wsp system, which likely exerts these effects through promoting Pel production.

Fig. 7. C. albicans promotes P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 WT biofilm formation on airway epithelial cells in part through ethanol production.

P. aeruginosa PAO1 WT was cultured with a monolayer of ΔF508 CFTR-CFBE cells alone or with C. albicans CAF2 (reference strain), the C. albicans adh1/adh1 mutant (adh1), and its complemented derivative, adh1/adh1+ADH1 (adh1-R). Data are combined from three independent experiments with 3–5 technical replicates per experiment, (* represents a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) between indicated strains). Error bars represent one standard deviation. Exogenous and C. albicans-produced ethanol alters P. aeruginosa phenazine production through a WspR-independent pathway

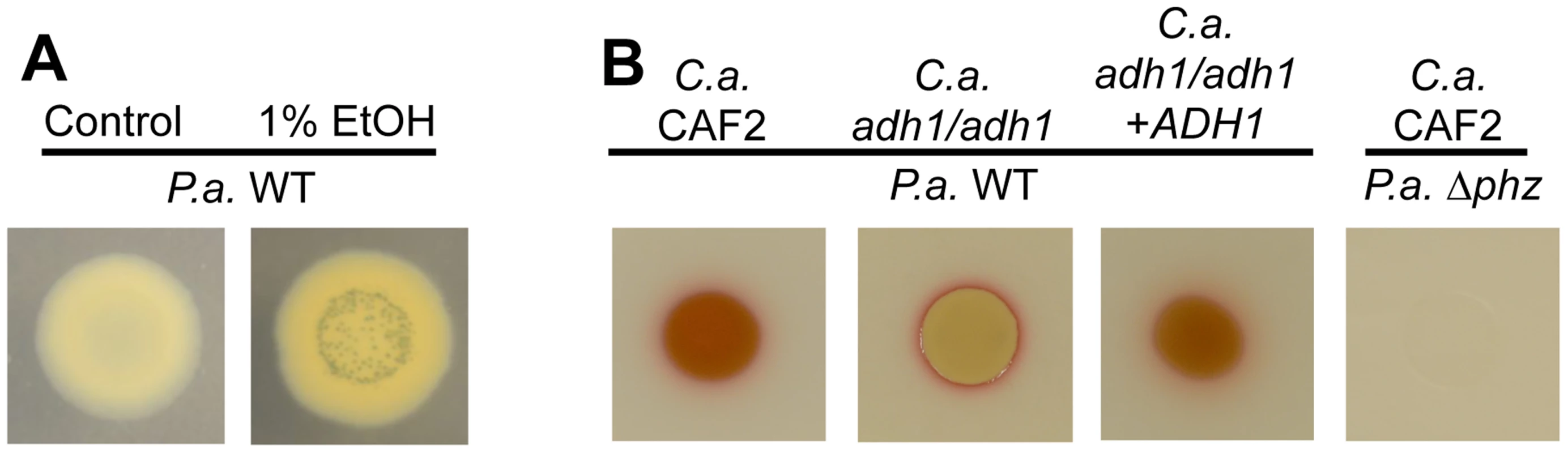

In part, these studies were instigated by the finding that P. aeruginosa phenazines strongly stimulate C. albicans ethanol production [18]. Thus, we were intrigued by the observation that colonies on ethanol-containing swarm plates, but not control plates, contained abundant emerald green crystals, similar to those formed by reduced phenazine-1-carboxamide (PCN) [40] (Fig. 8A, Fig. 4 and Fig. S7A), which could indicate a reciprocal relationship between ethanol and phenazines. Phenazine concentrations were measured using HPLC in either extracts from P. aeruginosa strain PA14 colonies or extracts from the underlying agar. In extracts from wild type colonies, PCN and PCA concentrations were 24.2 - and 5.8-fold higher, respectively, when ethanol was in the medium (Fig. S7B); much smaller differences in PCN and PCA concentrations were found in extracts of the underlying agar (Fig. S7C). Because PCA is the precursor for all other phenazine derivatives, including PCN (Fig. S7A), we further explored the effect of ethanol on PCA production. For this, we measured levels of PCA in a strain lacking all of the PCA modifying enzymes (PhzH, PhzM, and PhzS; see Fig. S7A for pathways) [41]. We found that ΔphzHMS colonies contained 1.7-fold more PCA (Fig. S7D) and released 1.3-fold more PCA into the agar (Fig. S7E) when grown in the presence of ethanol compared to control conditions. These data suggest that ethanol may cause a minor increase in PCA, and that it has greater effects on which species of phenazines are formed. The differences in phenazine levels or profiles did not appear to be responsible for ethanol effects on swarming as the Δphz mutant [42], which lacks phzA1-G1 and phzA2-G2, was like the wild type in that its swarming was repressed in the presence of ethanol, but it swarmed robustly in its absence (Fig. S7F).

Fig. 8. Ethanol leads to higher levels of PCN crystal formation and 5MPCA derivatives.

A. P. aeruginosa strain PA14 wild type (WT) was grown on medium without and with 1% ethanol. With ethanol, PCN crystals form and the colony has a yellowish color likely attributed to reduced PCN. B. P. aeruginosa strain PA14 WT was cultured on lawns of C. albicans CAF2 (WT reference strain), the C. albicans adh1/adh1 mutant, and its complemented derivative (adh1/adh1+ADH1); the PA14 Δphz mutant defective in phenazine production was plated on the C. albicans CAF2 for comparison. To determine if there was a connection between ethanol effects on Wsp signaling and ethanol stimulation of PCN levels, we assessed PCN accumulation in mutants lacking wspR or pelA. We found that both strains responded like the wild type in terms of PCN crystal formation upon growth with ethanol (Fig. S8A and Fig. 4). Similarly, ethanol catabolic mutants still showed enhanced levels of PCN crystals upon ethanol exposure (Fig. S8A).

Having observed alterations in the phenazine profile induced by ethanol, we examined the impact of ethanol in the production of a fourth phenazine derivative, 5MPCA, which we have previously shown to be released by P. aeruginosa when in the presence of C. albicans [19], [24]. Because P. aeruginosa-produced 5MPCA is converted into a red pigment within C. albicans cells, 5MPCA accumulation can be followed by observing the formation of a red color where P. aeruginosa and C. albicans are cultured together [19], [24]. To examine the effects of ethanol production on the accumulation of red 5MCPA derivatives, we again used the C. albicans adh1/adh1 mutant and its complemented derivative. Strikingly, when P. aeruginosa was cultured on lawns of the C. albicans adh1/adh1 strain, a strong decrease in red pigmentation was observed (Fig. 8B). When ADH1 was provided in trans to the adh1/adh1 mutant, accumulation of the red pigment was restored (Fig. 8B). Neither ethanol catabolism nor WspR activity was required for the stimulation of levels of 5MPCA derivatives by P. aeruginosa on fungal lawns (Fig. S8B).

Together, our data suggest that ethanol only slightly increases total phenazine production (Fig. S7D and E) but more strongly affects the derivatization of phenazines in P. aeruginosa colonies (Fig. S7B and C). Furthermore, C. albicans-produced ethanol stimulated P. aeruginosa 5MPCA production, and in turn, phenazines, including 5MPCA analogs, promote ethanol production [18]. Thus, it appears that P. aeruginosa-C. albicans interactions include a positive feedback loop that promotes fungal ethanol production and P. aeruginosa Wsp-dependent biofilm formation when the two species are cultured together.

Discussion

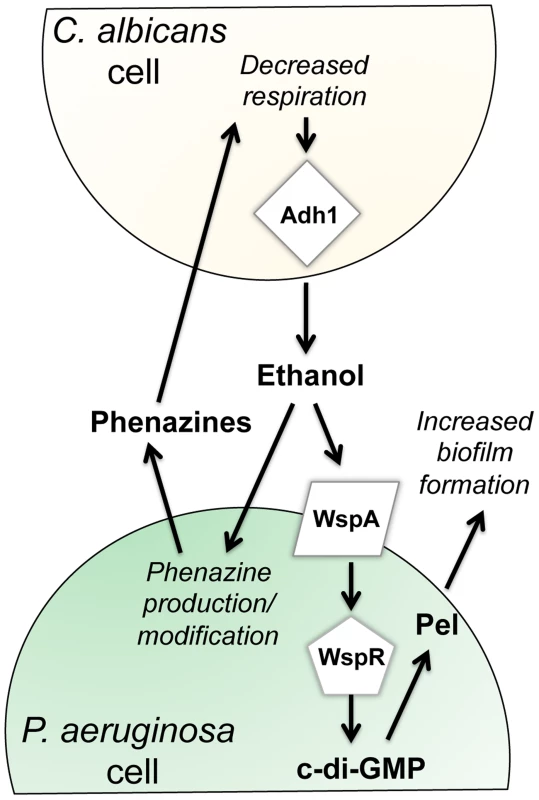

This paper reports new effects of ethanol on P. aeruginosa virulence-related traits, and illustrates that these effects occur through multiple pathways (Fig. 9). We found that ethanol: i) promoted attachment to and colonization of plastic and airway epithelial cells, ii) decreased swarming, but not twitching motility, iii) increased Pel-dependent colony wrinkling, and iv) increased c-di-GMP levels. All of these responses to ethanol required the diguanylate cyclase WspR. WspR is part of the Wsp chemosensory system, which is a member of the “alternative cellular function” (ACF) chemotaxis family [20], [21], [43]. The Wsp chemosensory system is different from the chemotaxis systems in P. aeruginosa in terms of its localization and response to environmental signals [44]. The membrane-bound receptor WspA and the CheA homologue WspE are necessary for the Wsp system to function, and WspE activates WspR via phosphorylation [44]. Consistent with our hypothesis that the entire Wsp system is required for the response to ethanol, we found that a wspA mutant was also insensitive to the effects of ethanol on biofilm formation (Fig. 5). The activation of WspR was independent of ethanol catabolism and independent of phenazine production. Ethanol and other alcohols can increase the rigidity of cell membranes by promoting an altered composition of fatty acids [45], and future studies will determine if the Wsp system, particularly the membrane localized WspA, can be activated by changes in the lipid composition or changes in the physical properties of P. aeruginosa membranes. Because the Wsp system is also activated upon contact with a surface [20], it is intriguing to consider how these stimuli might be similar. Ethanol had mild, if any, effects, on biofilm formation at the air-liquid interface in a commonly used 96-well microtiter dish assay in either strain (Fig. S9) suggesting that in this environment, different Wsp activating cues were not additive.

Fig. 9. Our proposed model for the impacts of fungally-produced ethanol on P. aeruginosa behaviors.

Our previous work has shown that P. aeruginosa phenazines increase fungal ethanol production. Here, we show that ethanol stimulates the Wsp system, leading to a WspR-dependent increase in c-di-GMP levels and a concomitant increase in Pel production and biofilm formation on plastic and on airway epithelial cells. In addition, ethanol altered phenazine production by promoting 5MPCA release and the accumulation of PCN. C. albicans and other Candida spp. are commonly detected in the sputum of CF patients, and clinical studies suggest that the presence of both P. aeruginosa and C. albicans results in a worse prognosis for CF patients [6], [46]. In vivo ethanol production by other fungi has been documented [47], [48], but a link between Candida spp. and ethanol production in the lung has not yet been made. It is important to note, however, that ethanol was one of two metabolites in exhaled breath condensate that differentiated CF from non-CF individuals [49]. Thus, regardless of the source of ethanol, be it fungal or bacterial, the effect of ethanol on pathogens such as P. aeruginosa is likely of biological and clinical relevance. We tested this interaction in the context of CF, but this polymicrobial interaction likely occurs in other contexts as well.

As shown above, ethanol promoted biofilm formation and likely concomitant increases in drug tolerance. In the airway epithelial cell system, P. aeruginosa CFU recovery was increased 3-fold by addition of ethanol (Fig. 6B) and 4.7-fold by co-culture with C. albicans (Fig. 7). A two-fold difference is comparable to the differences in colonization between wild-type P. aeruginosa strains and mutants lacking genes known to play a role in virulence in animal models. For example, a ΔplcHR mutant lacking hemolytic phospholipase C or a Δanr strain defective in a global regulator have 1.3 - to 2.6-fold fewer CFUs recovered from airway cells compared to wild type, and notable differences in animal models [50], [51]. Hence the presence of ethanol may result in increased virulence of P. aeruginosa in the host. Ethanol has also been shown to promote P. aeruginosa conversion to a mucoid state [52], in which the exopolysaccharide alginate is overproduced; mucoidy is common in CF isolates and is correlated with a decline in lung function [53], [54]. Ethanol has been shown to enhance virulence and biofilm formation by other lung pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus [55] and Acinetobacter baumanii [56]–[59] via mechanisms that have not yet been described. Like in P. aeruginosa (Fig. S1A), ethanol caused a slight stimulation of growth in A. baumanii [58].

In addition to the effects of ethanol on P. aeruginosa, ethanol is an immunosuppressant that negatively influences the lung immune response [60]–[64]. In a mouse model, ethanol inhibits lung clearance of P. aeruginosa by inhibiting macrophage recruitment [65]. Together, these observations suggest that in mixed infections, P. aeruginosa may promote the production of ethanol by fungi, and that fungally-produced ethanol may in turn enhance the virulence and persistence of co-existing pathogens, and thus may directly impact the host.

It is not yet known how ethanol influences the spectrum of P. aeruginosa phenazines produced. In a previous study, we found evidence for increased production and release of 5MPCA when P. aeruginosa is grown in co-culture with C. albicans, and that live C. albicans is required for this effect [19]. More recent studies show that C. albicans ethanol production increased in the presence of even very low concentrations of the 5MPCA analog phenazine methosulfate [18], that the 5MPCA-like compounds were even more effective inhibitors of fungi than PCA and PYO, the two phenazines normally produced when P. aeruginosa is grown in mono-culture. Here, our findings suggest a feedback loop in which C. albicans-produced ethanol promoted the release of phenazines (Fig. 7) that may promote further ethanol production [18]. It is also important to consider that some studies have reported that 5MPCA and PCN have enhanced antifungal activity when compared to PCA and PYO [19], [23], [24]. The ethanol-induced changes in PCA were not as dramatic when compared to the ethanol-induced changes in PCN and 5MPCA, suggesting that ethanol mainly affected the biosynthetic steps after the formation of PCA leading to its conversion to PCN, 5MPCA and PYO. In different settings, such as liquid cultures or in clinical isolates lacking activity of LasR, a transcriptional regulator for quorum sensing that controls phenazine production, the presence of C. albicans enhanced the production of 5MPCA and PYO [24], [25]. Taken together, all these observations indicate that fungally-produced ethanol may enhance the conversion of PCA to end products such as PCN, 5MPCA and PYO.

These studies indicate how microbial species can alter the behavior of one another and suggest that the nature of these dynamic interactions can change depending on the context. In the rhizosphere, where pseudomonad antagonism of fungi includes the colonization of fungal hyphae and phenazine production, the enhancement of fungally-produced ethanol by phenazines and stimulation of biofilm formation and phenazine production by ethanol may create a cycle that is relevant to biocontrol [23], [66], [67]. In chronic infections where these two species are found together, such as in chronic CF-associated lung disease, this molecular interplay may be synergistic and promote long-term colonization of both species in the host. These findings indicate that the treatment of colonizing fungi may be beneficial due to their effects on other pathogens even if the fungi themselves are not acting as overt agents of host damage.

Materials and Methods

Strains, media, and growth conditions

Bacterial and fungal strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1. Bacteria and fungi were maintained on LB [68] and YPD (2% peptone, 1% yeast extract, and 2% glucose) media, respectively. When stated, ethanol (200-proof), choline chloride or glycerol was added to the medium (liquid or molten agar) to a final concentration of 1%. Control cultures received an equivalent volume of water. When ethanol was supplied as a sole carbon source, glucose and amino acids were omitted. Mutants from the PA14 Non-Redundant (NR) Library were grown on LB with 30 µg/mL gentamicin [29]. When strains for the NR library were used, the location of the transposon insertion was confirmed using sets of site-specific primers followed by sequencing of the amplicon. The primers are listed in Table S2.

Growth curve analysis of P. aeruginosa in the presence of ethanol

For growth curves, overnight cultures were diluted into 5 ml fresh medium (LB or M63 with 0.2% glucose [69] with or without ethanol) to an OD600 nm of ∼0.05 and incubated at 37°C on a roller drum. Culture densities below 1.5 were measured directly in the culture tubes using a Spectronic 20 spectrophotometer. At higher cell densities, diluted culture aliquots were measured using a Genesys 6 spectrophotometer.

Quantification of P. aeruginosa attachment to plastic and airway epithelial cells

To measure the attachment of cells to the plastic surface in 6-well or 12-well untreated polystyrene plates, wells were inoculated with a suspension of cells at an initial OD600 nm of 0.002 from overnight cultures. Every 90 minutes, the culture medium was removed and fresh medium was supplied. Pictures were taken using an inverted Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope with a long distance 63× DIC objective at specified intervals. To quantify the number of cells or microcolonies in control cultures compared to cultures with ethanol, images were captured, randomized, and analyzed by a researcher who was blind to the identity of the sample at the time of analysis. In each experiment, more than 10 fields were counted for each strain. Microcolonies were defined as clusters of more than 5 cells in physical contact with one another. Biofilm formation on plastic microtiter dishes were performed and analyzed using the crystal violet assay as described in [55] and biofilm values were measured by quantification of dye as measured absorbance at 650 nm.

The analysis of P. aeruginosa colonization of airway epithelial cells was performed using CFBE human bronchial epithelial cells (CFBE410−) with the CFTRΔF508/ΔF508 genotype [70] as described previously [35], [36]. For imaging, cells were grown in 6-well glass bottom dishes (MatTek). For quantification of attached cells, CFBEs were grown in 6 or 12 well plates. P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 cells were added at an MOI of 30∶1, and the medium was exchanged every 1.5 hours. For experiments with C. albicans, PAO1 cells and C.albicans were added together to CFBE monolayers, where C.albicans was at an MOI of 10∶1 with respect to the epithelial cells. Pictures were taken using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope with a 63× DIC objective at specified intervals. We performed multiple experiments with technical replicates (between three and six) on different days and analyzed the data with a one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc t-test using Graph Pad Prism 6. We observed that cells from different passages had differences in the mean attachment across all samples from that day. Thus, we normalized values to the mean across all samples from each experiment. LDH release was measured after six hours using the Promega CytoTox96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity kit as described in the manufacturer's instructions.

Analysis of P. aeruginosa swarming and twitching motility

Swarming motility was tested by inoculating 2.5 µL of overnight cultures on fresh M8 (M8 salts without trace elements supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 0.5% casamino acids, and 1 µM MgSO4) containing 0.5% agar as described previously [71]. Plates were incubated face up at 37°C with 70–80% humidity in stacks of no more than 4 for 16.5 hrs. To quantify the degree of swarming, percent coverage of the plate was measured using ImageJ software [72]. Twitching motility was analyzed as described previously [26].

Cyclic-di-GMP measurements

Cells were collected from swarm plates after incubation at 37°C for 16.5 h and placed in pre-weighed 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. Tubes were centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 4 minutes. The pellets were then resuspended in 250 µL of extraction buffer by vigorous vortexing (extraction buffer: MeOH/acetonitrile/dH2O 40∶40∶20+0.1 N formic acid stored at −20°C). The extractions were incubated at −20°C for 30 minutes in an upright position. The tubes were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C. 200 µL of the extraction were recovered into new Eppendorf tubes and neutralized with 4 µL of 15% NH4HCO3 per 100 µL of sample. The tubes with cell debris were left to dry and reweighed for normalization of cell numbers from swarm plates. 150 µL of samples were sent to the RTSF Mass Spectrometry and Metabolomics Core at Michigan State University for LC-MS analysis.

Microscopic analysis of WspR

Sample preparation and microscopy were performed as previously described [20], [34]. To analyze liquid-grown cells, cultures were grown at 37°C while shaking to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3 in M9 medium (1× M9 salts pH 7.4, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.2% glycerol, 0.2% casamino acids and 10 µg/ml thiamine HCl). 1% arabinose was included for induction of wspR, and 1% ethanol was added when comparing its effect on WspR clustering. From each culture, 3 µl were spotted onto a 0.8% agarose PBS pad on a microscope slide and then covered with a coverslip.

More than 100 cells were counted for each condition.

P. aeruginosa-C. albicans co-cultures

Preformed lawns of C. albicans CAF2 and adh1/adh1 were prepared by spreading 700 µL of a YPD-grown overnight culture onto a YPD 1.5% agar plate followed by incubation at 30°C for 48 hr. Exponential phase P. aeruginosa liquid cultures were spotted (5–10 µL) onto the C. albicans lawns, then incubated at 30°C for an additional 24 to 72 hours.

Analysis of phenazines

Overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa PA14 wild-type and ΔphzHΔphzMΔphzS strains were grown in LB at 37°C (shaken at 250 rpm). Ten microliters of each culture were spotted onto a track-etched membrane (Whatman 110606; pore size 0.2 µm; diameter 2.5 cm) that was placed on a 1.5% agar M8 medium supplemented with either vehicle (water) or 1% v/v ethanol. Plates contained 3 ml of medium in a 35×10 mm agar plate (Falcon). The colonies were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours and then at room temperature for 72 hours, after which phenazines were extracted from the colonies and agar separately. Each track-etched membrane with a colony was lifted off the agar plates and nutated in 5 mL of 100% methanol overnight at room temperature. Similarly, the agar was nutated overnight in 5 mL of 100% methanol. Colony and agar extracts were filtered (0.2 µm pore) and phenazines in the extraction volume (5 mL) were quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography as previously described [41] at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min.

Statistical analyses

All data were analyzed using Graph Pad Prism 6. The data represent the mean standard deviation of at least three independent experiments with multiple replicates unless stated otherwise. For normally distributed data, comparisons were tested with Student's t-test.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. FilkinsLM, HamptonTH, GiffordAH, GrossMJ, HoganDA, et al. (2012) Prevalence of streptococci and increased polymicrobial diversity associated with cystic fibrosis patient stability. J Bacteriol 194 : 4709–4717.

2. ZhaoJ, SchlossPD, KalikinLM, CarmodyLA, FosterBK, et al. (2012) Decade-long bacterial community dynamics in cystic fibrosis airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 : 5809–5814.

3. FodorAA, KlemER, GilpinDF, ElbornJS, BoucherRC, et al. (2012) The adult cystic fibrosis airway microbiota is stable over time and infection type, and highly resilient to antibiotic treatment of exacerbations. PLoS One 7: e45001.

4. DelhaesL, MonchyS, FrealleE, HubansC, SalleronJ, et al. (2012) The airway microbiota in cystic fibrosis: a complex fungal and bacterial community–implications for therapeutic management. PLoS One 7: e36313.

5. LeclairLW, HoganDA (2010) Mixed bacterial-fungal infections in the CF respiratory tract. Med Mycol 48: S125–S132.

6. ChotirmallSH, O'DonoghueE, BennettK, GunaratnamC, O'NeillSJ, et al. (2010) Sputum Candida albicans presages FEV1 decline and hospitalized exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. Chest 138 : 1186–1195.

7. NavarroJ, RainisioM, HarmsHK, HodsonME, KochC, et al. (2001) Factors associated with poor pulmonary function: cross-sectional analysis of data from the ERCF. European Epidemiologic Registry of Cystic Fibrosis. Eur Respir J 18 : 298–305.

8. ParsekMR, SinghPK (2003) Bacterial biofilms: an emerging link to disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Microbiol 57 : 677–701.

9. DaveyME, O'TooleGA (2000) Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 64 : 847–867.

10. MahTF, O'TooleGA (2001) Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol 9 : 34–39.

11. RomlingU, GalperinMY, GomelskyM (2013) Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77 : 1–52.

12. BaraquetC, HarwoodCS (2013) Cyclic diguanosine monophosphate represses bacterial flagella synthesis by interacting with the Walker A motif of the enhancer-binding protein FleQ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 : 18478–18483.

13. IrieY, BorleeBR, O'ConnorJR, HillPJ, HarwoodCS, et al. (2012) Self-produced exopolysaccharide is a signal that stimulates biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 : 20632–20636.

14. KuchmaSL, GriffinEF, O'TooleGA (2012) Minor pilins of the type IV pilus system participate in the negative regulation of swarming motility. J Bacteriol 194 : 5388–5403.

15. HunterRC, Klepac-CerajV, LorenziMM, GrotzingerH, MartinTR, et al. (2012) Phenazine content in the cystic fibrosis respiratory tract negatively correlates with lung function and microbial complexity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 47 : 738–745.

16. RadaB, LetoTL (2013) Pyocyanin effects on respiratory epithelium: relevance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway infections. Trends Microbiol 21 : 73–81.

17. DenningGM, IyerSS, ReszkaKJ, O'MalleyY, RasmussenGT, et al. (2003) Phenazine-1-carboxylic acid, a secondary metabolite of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, alters expression of immunomodulatory proteins by human airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 285: L584–592.

18. MoralesDK, GrahlN, OkegbeC, DietrichLE, JacobsNJ, et al. (2013) Control of Candida albicans metabolism and biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa phenazines. MBio 4: e00526-00512.

19. MoralesDK, JacobsNJ, RajamaniS, KrishnamurthyM, Cubillos-RuizJR, et al. (2010) Antifungal mechanisms by which a novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa phenazine toxin kills Candida albicans in biofilms. Mol Microbiol 78 : 1379–1392.

20. GuvenerZT, HarwoodCS (2007) Subcellular location characteristics of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa GGDEF protein, WspR, indicate that it produces cyclic-di-GMP in response to growth on surfaces. Mol Microbiol 66 : 1459–1473.

21. HickmanJW, TifreaDF, HarwoodCS (2005) A chemosensory system that regulates biofilm formation through modulation of cyclic diguanylate levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 : 14422–14427.

22. KulasakaraH, LeeV, BrencicA, LiberatiN, UrbachJ, et al. (2006) Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases reveals a role for bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic-GMP in virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 : 2839–2844.

23. ChinAWTF, Thomas-OatesJE, LugtenbergBJ, BloembergGV (2001) Introduction of the phzH gene of Pseudomonas chlororaphis PCL1391 extends the range of biocontrol ability of phenazine-1-carboxylic acid-producing Pseudomonas spp. strains. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14 : 1006–1015.

24. GibsonJ, SoodA, HoganDA (2009) Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Candida albicans interactions: localization and fungal toxicity of a phenazine derivative. Appl Environ Microbiol 75 : 504–513.

25. CuginiC, MoralesDK, HoganDA (2010) Candida albicans-produced farnesol stimulates Pseudomonas quinolone signal production in LasR-defective Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Microbiology 156 : 3096–3107.

26. O'TooleGA, KolterR (1998) Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol Microbiol 30 : 295–304.

27. MernDS, HaSW, KhodaverdiV, GlieseN, GorischH (2010) A complex regulatory network controls aerobic ethanol oxidation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: indication of four levels of sensor kinases and response regulators. Microbiology 156 : 1505–1516.

28. KretzschmarU, SchobertM, GorischH (2001) The Pseudomonas aeruginosa acsA gene, encoding an acetyl-CoA synthetase, is essential for growth on ethanol. Microbiology 147 : 2671–2677.

29. LiberatiNT, UrbachJM, MiyataS, LeeDG, DrenkardE, et al. (2006) An ordered, nonredundant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 transposon insertion mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103 : 2833–2838.

30. TamayoR, PrattJT, CamilliA (2007) Roles of cyclic diguanylate in the regulation of bacterial pathogenesis. Annu Rev Microbiol 61 : 131–148.

31. HaDG, RichmanME, O'TooleGA (2014) Deletion mutant library for investigation of functional outputs of cyclic diguanylate metabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. Appl Environ Microbiol 80 : 3384–3393.

32. D'ArgenioDA, CalfeeMW, RaineyPB, PesciEC (2002) Autolysis and autoaggregation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa colony morphology mutants. J Bacteriol 184 : 6481–6489.

33. FriedmanL, KolterR (2004) Genes involved in matrix formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 biofilms. Mol Microbiol 51 : 675–690.

34. HuangyutithamV, GuvenerZT, HarwoodCS (2013) Subcellular clustering of the phosphorylated WspR response regulator protein stimulates its diguanylate cyclase activity. MBio 4: e00242-00213.

35. AndersonGG, Moreau-MarquisS, StantonBA, O'TooleGA (2008) In vitro analysis of tobramycin-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms on cystic fibrosis-derived airway epithelial cells. Infect Immun 76 : 1423–1433.

36. Moreau-MarquisS, BombergerJM, AndersonGG, Swiatecka-UrbanA, YeS, et al. (2008) The DeltaF508-CFTR mutation results in increased biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa by increasing iron availability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L25–37.

37. ElaminE, JonkersD, Juuti-UusitaloK, van IjzendoornS, TroostF, et al. (2012) Effects of ethanol and acetaldehyde on tight junction integrity: in vitro study in a three dimensional intestinal epithelial cell culture model. PLoS One 7: e35008.

38. MaTY, NguyenD, BuiV, NguyenH, HoaN (1999) Ethanol modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Am J Physiol 276: G965–974.

39. MukherjeePK, MohamedS, ChandraJ, KuhnD, LiuS, et al. (2006) Alcohol dehydrogenase restricts the ability of the pathogen Candida albicans to form a biofilm on catheter surfaces through an ethanol-based mechanism. Infect Immun 74 : 3804–3816.

40. KannerD, GerberNN, BarthaR (1978) Pattern of phenazine pigment production by a strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 134 : 690–692.

41. RecinosDA, SekedatMD, HernandezA, CohenTS, SakhtahH, et al. (2012) Redundant phenazine operons in Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibit environment-dependent expression and differential roles in pathogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 : 19420–19425.

42. DietrichLE, Price-WhelanA, PetersenA, WhiteleyM, NewmanDK (2006) The phenazine pyocyanin is a terminal signalling factor in the quorum sensing network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 61 : 1308–1321.

43. WuichetK, AlexanderRP, ZhulinIB (2007) Comparative genomic and protein sequence analyses of a complex system controlling bacterial chemotaxis. Methods Enzymol 422 : 1–31.

44. O'ConnorJR, KuwadaNJ, HuangyutithamV, WigginsPA, HarwoodCS (2012) Surface sensing and lateral subcellular localization of WspA, the receptor in a chemosensory-like system leading to c-di-GMP production. Mol Microbiol 86 : 720–729.

45. IngramLO, ButtkeTM (1984) Effects of alcohols on microorganisms. Adv Microb Physiol 25 : 253–300.

46. AzoulayE, TimsitJF, TaffletM, de LassenceA, DarmonM, et al. (2006) Candida colonization of the respiratory tract and subsequent pseudomonas ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 129 : 110–117.

47. HimmelreichU, AllenC, DowdS, MalikR, ShehanBP, et al. (2003) Identification of metabolites of importance in the pathogenesis of pulmonary cryptococcoma using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Microbes Infect 5 : 285–290.

48. GrahlN, PuttikamonkulS, MacdonaldJM, GamcsikMP, NgoLY, et al. (2011) In vivo hypoxia and a fungal alcohol dehydrogenase influence the pathogenesis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002145.

49. MontuschiP, ParisD, MelckD, LucidiV, CiabattoniG, et al. (2012) NMR spectroscopy metabolomic profiling of exhaled breath condensate in patients with stable and unstable cystic fibrosis. Thorax 67 : 222–228.

50. JacksonAA, GrossMJ, DanielsEF, HamptonTH, HammondJH, et al. (2013) Anr and its activation by PlcH activity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa host colonization and virulence. J Bacteriol 195 : 3093–3104.

51. WargoMJ, GrossMJ, RajamaniS, AllardJL, LundbladLK, et al. (2011) Hemolytic phospholipase C inhibition protects lung function during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184 : 345–354.

52. DeVaultJD, KimbaraK, ChakrabartyAM (1990) Pulmonary dehydration and infection in cystic fibrosis: evidence that ethanol activates alginate gene expression and induction of mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 4 : 737–745.

53. DereticV, GovanJR, KonyecsniWM, MartinDW (1990) Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: mutations in the muc loci affect transcription of the algR and algD genes in response to environmental stimuli. Mol Microbiol 4 : 189–196.

54. BoucherJC, YuH, MuddMH, DereticV (1997) Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: characterization of muc mutations in clinical isolates and analysis of clearance in a mouse model of respiratory infection. Infect Immun 65 : 3838–3846.

55. KoremM, GovY, RosenbergM (2010) Global gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus following exposure to alcohol. Microb Pathog 48 : 74–84.

56. NwugoCC, ArivettBA, ZimblerDL, GaddyJA, RichardsAM, et al. (2012) Effect of ethanol on differential protein production and expression of potential virulence functions in the opportunistic pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS One 7: e51936.

57. CamarenaL, BrunoV, EuskirchenG, PoggioS, SnyderM (2010) Molecular mechanisms of ethanol-induced pathogenesis revealed by RNA-sequencing. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000834.

58. SmithMG, Des EtagesSG, SnyderM (2004) Microbial synergy via an ethanol-triggered pathway. Mol Cell Biol 24 : 3874–3884.

59. SmithMG, GianoulisTA, PukatzkiS, MekalanosJJ, OrnstonLN, et al. (2007) New insights into Acinetobacter baumannii pathogenesis revealed by high-density pyrosequencing and transposon mutagenesis. Genes Dev 21 : 601–614.

60. GoralJ, KaravitisJ, KovacsEJ (2008) Exposure-dependent effects of ethanol on the innate immune system. Alcohol 42 : 237–247.

61. SzaboG, MandrekarP (2009) A recent perspective on alcohol, immunity, and host defense. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33 : 220–232.

62. KaravitisJ, KovacsEJ (2011) Macrophage phagocytosis: effects of environmental pollutants, alcohol, cigarette smoke, and other external factors. J Leukoc Biol 90 : 1065–1078.

63. HappelKI, NelsonS (2005) Alcohol, immunosuppression, and the lung. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2 : 428–432.

64. GuidotDM, HartCM (2005) Alcohol abuse and acute lung injury: epidemiology and pathophysiology of a recently recognized association. J Investig Med 53 : 235–245.

65. GreenbergSS, ZhaoX, HuaL, WangJF, NelsonS, et al. (1999) Ethanol inhibits lung clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by a neutrophil and nitric oxide-dependent mechanism, in vivo. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23 : 735–744.

66. ChinAWTF, BloembergGV, MuldersIH, DekkersLC, LugtenbergBJ (2000) Root colonization by phenazine-1-carboxamide-producing bacterium Pseudomonas chlororaphis PCL1391 is essential for biocontrol of tomato foot and root rot. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 13 : 1340–1345.

67. BolwerkA, LagopodiAL, WijfjesAH, LamersGE, ChinAWTF, et al. (2003) Interactions in the tomato rhizosphere of two Pseudomonas biocontrol strains with the phytopathogenic fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 16 : 983–993.

68. BertaniG (1951) Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 62 : 293–300.

69. NeidhardtFC, BlochPL, SmithDF (1974) Culture medium for enterobacteria. J Bacteriol 119 : 736–747.

70. CozensAL, YezziMJ, ChinL, SimonEM, FinkbeinerWE, et al. (1992) Characterization of immortal cystic fibrosis tracheobronchial gland epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89 : 5171–5175.

71. KohlerT, CurtyLK, BarjaF, van DeldenC, PechereJC (2000) Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on cell-to-cell signaling and requires flagella and pili. J Bacteriol 182 : 5990–5996.

72. AbramoffMD, MagelhaesPJ, RamSJ (2004) Image Processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics International 11 : 36–42.

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiológia Infekčné lekárstvo Laboratórium

Článek Identification of the Microsporidian as a New Target of the IFNγ-Inducible IRG Resistance SystemČlánek Human Cytomegalovirus Drives Epigenetic Imprinting of the Locus in NKG2C Natural Killer CellsČlánek APOBEC3D and APOBEC3F Potently Promote HIV-1 Diversification and Evolution in Humanized Mouse ModelČlánek Role of Non-conventional T Lymphocytes in Respiratory Infections: The Case of the Pneumococcus

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2014 Číslo 10- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Očkování proti virové hemoragické horečce Ebola experimentální vakcínou rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP

- Koronavirus hýbe světem: Víte jak se chránit a jak postupovat v případě podezření?

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Theory and Empiricism in Virulence Evolution

- -Related Fungi and Reptiles: A Fatal Attraction

- Adaptive Prediction As a Strategy in Microbial Infections

- Antimicrobials, Stress and Mutagenesis

- A Novel Function of Human Pumilio Proteins in Cytoplasmic Sensing of Viral Infection

- Social Motility of African Trypanosomes Is a Property of a Distinct Life-Cycle Stage That Occurs Early in Tsetse Fly Transmission

- Autophagy Controls BCG-Induced Trained Immunity and the Response to Intravesical BCG Therapy for Bladder Cancer

- Identification of the Microsporidian as a New Target of the IFNγ-Inducible IRG Resistance System

- mRNA Structural Constraints on EBNA1 Synthesis Impact on Antigen Presentation and Early Priming of CD8 T Cells

- Infection Causes Distinct Epigenetic DNA Methylation Changes in Host Macrophages

- Neutrophil Crawling in Capillaries; A Novel Immune Response to

- Live Attenuated Vaccine Protects against Pulmonary Challenge in Rats and Non-human Primates

- The ESAT-6 Protein of Interacts with Beta-2-Microglobulin (β2M) Affecting Antigen Presentation Function of Macrophage

- Characterization of Uncultivable Bat Influenza Virus Using a Replicative Synthetic Virus

- HIV Acquisition Is Associated with Increased Antimicrobial Peptides and Reduced HIV Neutralizing IgA in the Foreskin Prepuce of Uncircumcised Men

- Uses a Unique Ligand-Binding Mode for Trapping Opines and Acquiring A Competitive Advantage in the Niche Construction on Plant Host

- Involvement of a 1-Cys Peroxiredoxin in Bacterial Virulence

- Ethanol Stimulates WspR-Controlled Biofilm Formation as Part of a Cyclic Relationship Involving Phenazines

- Densovirus Is a Mutualistic Symbiont of a Global Crop Pest () and Protects against a Baculovirus and Bt Biopesticide

- Insights into Intestinal Colonization from Monitoring Fluorescently Labeled Bacteria

- Mycobacterial Antigen Driven Activation of CD14CD16 Monocytes Is a Predictor of Tuberculosis-Associated Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome

- Lipoprotein LprG Binds Lipoarabinomannan and Determines Its Cell Envelope Localization to Control Phagolysosomal Fusion

- Dampens the DNA Damage Response

- MicroRNAs Suppress NB Domain Genes in Tomato That Confer Resistance to

- Novel Cyclic di-GMP Effectors of the YajQ Protein Family Control Bacterial Virulence

- Vaginal Challenge with an SIV-Based Dual Reporter System Reveals That Infection Can Occur throughout the Upper and Lower Female Reproductive Tract

- Detecting Differential Transmissibilities That Affect the Size of Self-Limited Outbreaks

- One Small Step for a Yeast - Microevolution within Macrophages Renders Hypervirulent Due to a Single Point Mutation

- Expression Profiling during Arabidopsis/Downy Mildew Interaction Reveals a Highly-Expressed Effector That Attenuates Responses to Salicylic Acid

- Human Cytomegalovirus Drives Epigenetic Imprinting of the Locus in NKG2C Natural Killer Cells

- Interaction with Tsg101 Is Necessary for the Efficient Transport and Release of Nucleocapsids in Marburg Virus-Infected Cells

- The N-Terminus of Murine Leukaemia Virus p12 Protein Is Required for Mature Core Stability

- Sterol Biosynthesis Is Required for Heat Resistance but Not Extracellular Survival in

- Allele-Specific Induction of IL-1β Expression by C/EBPβ and PU.1 Contributes to Increased Tuberculosis Susceptibility

- Host Cofactors and Pharmacologic Ligands Share an Essential Interface in HIV-1 Capsid That Is Lost upon Disassembly

- APOBEC3D and APOBEC3F Potently Promote HIV-1 Diversification and Evolution in Humanized Mouse Model

- Structural Basis for the Recognition of Human Cytomegalovirus Glycoprotein B by a Neutralizing Human Antibody

- Systematic Analysis of ZnCys Transcription Factors Required for Development and Pathogenicity by High-Throughput Gene Knockout in the Rice Blast Fungus

- Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 3A Promotes Cellular Proliferation by Repression of the Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1

- The Host Protein Calprotectin Modulates the Type IV Secretion System via Zinc Sequestration

- Cyclophilin A Associates with Enterovirus-71 Virus Capsid and Plays an Essential Role in Viral Infection as an Uncoating Regulator

- A Novel Alpha Kinase EhAK1 Phosphorylates Actin and Regulates Phagocytosis in

- The pH-Responsive PacC Transcription Factor of Governs Epithelial Entry and Tissue Invasion during Pulmonary Aspergillosis

- Sensing of Immature Particles Produced by Dengue Virus Infected Cells Induces an Antiviral Response by Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells

- Co-opted Oxysterol-Binding ORP and VAP Proteins Channel Sterols to RNA Virus Replication Sites via Membrane Contact Sites

- Characteristics of Memory B Cells Elicited by a Highly Efficacious HPV Vaccine in Subjects with No Pre-existing Immunity

- HPV16-E7 Expression in Squamous Epithelium Creates a Local Immune Suppressive Environment via CCL2- and CCL5- Mediated Recruitment of Mast Cells

- Dengue Viruses Are Enhanced by Distinct Populations of Serotype Cross-Reactive Antibodies in Human Immune Sera

- CD4 Depletion in SIV-Infected Macaques Results in Macrophage and Microglia Infection with Rapid Turnover of Infected Cells

- A Sialic Acid Binding Site in a Human Picornavirus

- Contact Heterogeneity, Rather Than Transmission Efficiency, Limits the Emergence and Spread of Canine Influenza Virus

- Myosins VIII and XI Play Distinct Roles in Reproduction and Transport of

- HTLV-1 Tax Stabilizes MCL-1 via TRAF6-Dependent K63-Linked Polyubiquitination to Promote Cell Survival and Transformation

- Species Complex: Ecology, Phylogeny, Sexual Reproduction, and Virulence

- A Critical Role for IL-17RB Signaling in HTLV-1 Tax-Induced NF-κB Activation and T-Cell Transformation

- Exosomes from Hepatitis C Infected Patients Transmit HCV Infection and Contain Replication Competent Viral RNA in Complex with Ago2-miR122-HSP90

- Role of Non-conventional T Lymphocytes in Respiratory Infections: The Case of the Pneumococcus

- Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Induces Nrf2 during Infection of Endothelial Cells to Create a Microenvironment Conducive to Infection

- A Relay Network of Extracellular Heme-Binding Proteins Drives Iron Acquisition from Hemoglobin

- Glutamate Secretion and Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 1 Expression during Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Infection Promotes Cell Proliferation

- Reduces Malaria and Dengue Infection in Vector Mosquitoes and Has Entomopathogenic and Anti-pathogen Activities

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Novel Cyclic di-GMP Effectors of the YajQ Protein Family Control Bacterial Virulence

- MicroRNAs Suppress NB Domain Genes in Tomato That Confer Resistance to

- The ESAT-6 Protein of Interacts with Beta-2-Microglobulin (β2M) Affecting Antigen Presentation Function of Macrophage

- Characterization of Uncultivable Bat Influenza Virus Using a Replicative Synthetic Virus

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy