-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

A Genome-Wide Association Study of Nephrolithiasis in the Japanese Population Identifies Novel Susceptible Loci at 5q35.3, 7p14.3, and 13q14.1

Nephrolithiasis is a common nephrologic disorder with complex etiology. To identify the genetic factor(s) for nephrolithiasis, we conducted a three-stage genome-wide association study (GWAS) using a total of 5,892 nephrolithiasis cases and 17,809 controls of Japanese origin. Here we found three novel loci for nephrolithiasis: RGS14-SLC34A1-PFN3-F12 on 5q35.3 (rs11746443; P = 8.51×10−12, odds ratio (OR) = 1.19), INMT-FAM188B-AQP1 on 7p14.3 (rs1000597; P = 2.16×10−14, OR = 1.22), and DGKH on 13q14.1 (rs4142110; P = 4.62×10−9, OR = 1.14). Subsequent analyses in 21,842 Japanese subjects revealed the association of SNP rs11746443 with the reduction of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (P = 6.54×10−8), suggesting a crucial role for this variation in renal function. Our findings elucidated the significance of genetic variations for the pathogenesis of nephrolithiasis.

Published in the journal: A Genome-Wide Association Study of Nephrolithiasis in the Japanese Population Identifies Novel Susceptible Loci at 5q35.3, 7p14.3, and 13q14.1. PLoS Genet 8(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002541

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002541Summary

Nephrolithiasis is a common nephrologic disorder with complex etiology. To identify the genetic factor(s) for nephrolithiasis, we conducted a three-stage genome-wide association study (GWAS) using a total of 5,892 nephrolithiasis cases and 17,809 controls of Japanese origin. Here we found three novel loci for nephrolithiasis: RGS14-SLC34A1-PFN3-F12 on 5q35.3 (rs11746443; P = 8.51×10−12, odds ratio (OR) = 1.19), INMT-FAM188B-AQP1 on 7p14.3 (rs1000597; P = 2.16×10−14, OR = 1.22), and DGKH on 13q14.1 (rs4142110; P = 4.62×10−9, OR = 1.14). Subsequent analyses in 21,842 Japanese subjects revealed the association of SNP rs11746443 with the reduction of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (P = 6.54×10−8), suggesting a crucial role for this variation in renal function. Our findings elucidated the significance of genetic variations for the pathogenesis of nephrolithiasis.

Introduction

Nephrolithiasis, also called kidney stone, is a common disorder which causes severe acute back pain and sometimes leads to severe complications such as pyelonephritis or acute renal failure. Lifetime prevalence of nephrolithiasis is estimated to be 4–9% in Japan [1], and nearly 60% of patients reveal recurrence within 10 years after their initial treatment [2]. Most of kidney stones are composed of calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate crystals [3]. Hypercalciuria, urinary tract infection, and alkaline urine are considered to cause urinary supersaturation and subsequently induce the formation of calcium stone. Westernized diet, obesity, and dehydration were also indicated their association with nephrolithiasis [4], [5]. In addition, a family history was reported to increase the disease risk (2.57 times higher) in males [6], and the concordance rate of the disease in monozygotic twins was significantly higher than that in dizygotic twins (32.4% vs. 17.3%) [7], indicating a pivotal role of genetic factors in its etiology. In 2009, a genome wide association study (GWAS) in Caucasian revealed a significant association of the CLDN14 gene with nephrolithiasis and bone mineral density [8]. To investigate the genetic factors that are associated with the risk of nephrolithiasis in Japanese population, we conducted three-stage GWAS (Figure S1 and Table S1).

Results/Discussion

In GWAS, we genotyped 1,000 Japanese patients with nephrolithiasis and 7,936 non-nephrolithiasis controls using Human Omni Express BeadChip. Patients with struvite, cystine, ammonium acid urate, and uric acid stone, or secondary nephrolithiasis caused by drugs, hyperparathyroidism, or kidney deformity were excluded from our analysis, since their underlying pathology is different from that of calcium nephrolithiasis. After standard quality-control filtering (call rate ≥0.99 in cases and controls, Hardy-Weinberg P≥1×10−6 in controls), we conducted principal component analysis and found that all subjects were of Asian ancestry (Figure S2). We evaluated the association of SNPs with nephrolithiasis by Cochran-Armitage trend test. As a result, the genomic inflation factor was calculated to be 1.123 (Figure S3). To adjust population stratification, we used two methods, logistic regression analysis using top principle components as covariate and the association analysis using 904 cases and 7,471 controls belonging to the Hondo cluster, the major cluster of Japanese population [9]. As a result, the genomic inflation factors for these analyses were improved to be 1.054 (adjustment by PC1 and PC2) and 1.042 (Hondo cluster), respectively (Figure S4a, S4b). Finally, we decide to use only Hondo cluster samples in GWAS to minimize likelihood of false positive associations. Although no SNP achieved the GWAS significance threshold (P<5×10−8), we selected top 100 SNPs (P≤7.85×10−5) showing the smallest P-value for further association analysis (Figure S4c and Table S2).

We selected 64 SNPs by linkage disequilibrium analysis with the criteria of pairwise r2 of ≥0.8 from the top 100 SNPs in 37 genomic regions and analyzed them using 2,783 Japanese nephrolithiasis cases and 5,251 controls. Fifty nine SNPs among 64 SNPs passed the same quality-control filtering as GWAS and were subjected to association analysis with nephrolithiasis by Cochran-Armitage trend test. We found 11 SNPs in five loci to be significantly associated with nephrolithiasis after Bonferroni correction (P<0.05/59 = 8.47×10−4, Table S3). A meta-analysis of GWAS and stage 2 revealed that seven SNPs cleared the genome wide significant threshold (P<5×10−8) (Table S4). Therefore, we considered stage 3 as a replication analysis for these seven SNPs.

Subsequently, we genotyped 11 SNPs in the additional cohort consisting of 2,109 nephrolithiasis cases and 4,622 controls. We excluded SNP rs10866504 from further analysis due to departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in control samples. Five SNPs among ten cleared the significant threshold (P<0.005) in stage 3 (Table S5a). A meta-analysis with a fixed-effects model revealed all five SNPs indicated the significant association (P<5×10−8) without heterogeneity between three studies (Table 1). SNP rs3765623 also exhibited trend of association in stage 3 with p-value of 0.0371, however this SNP did not clear the genome wide significant threshold in the meta-analysis (P = 1.28×10−7) (Table S5b). Although SNP rs7981733 and rs1170155 also cleared the significant threshold in the meta-analysis (P = 1.43×10−8 and 3.89×10−9, respectively), these two SNPs did not indicate significant association in stage 3 (P = 0.0705 and 0.132, respectively) and exhibited heterogeneity between three studies (Table S5b). Therefore, further analysis is necessary to elucidate the role of these SNPs in the pathogenesis of nephrolithiasis. After all, we found three novel loci for nephrolithiasis: RGS14-SLC34A1-PFN3-F12 on 5q35.3 (rs11746443; P = 8.51×10−12, odds ratio (OR) = 1.19), INMT-FAM188B-AQP1 on 7p14.3 (rs1000597; P = 2.16×10−14, OR = 1.22), and DGKH on 13q14.1 (rs4142110; P = 4.62×10−9, OR = 1.14).

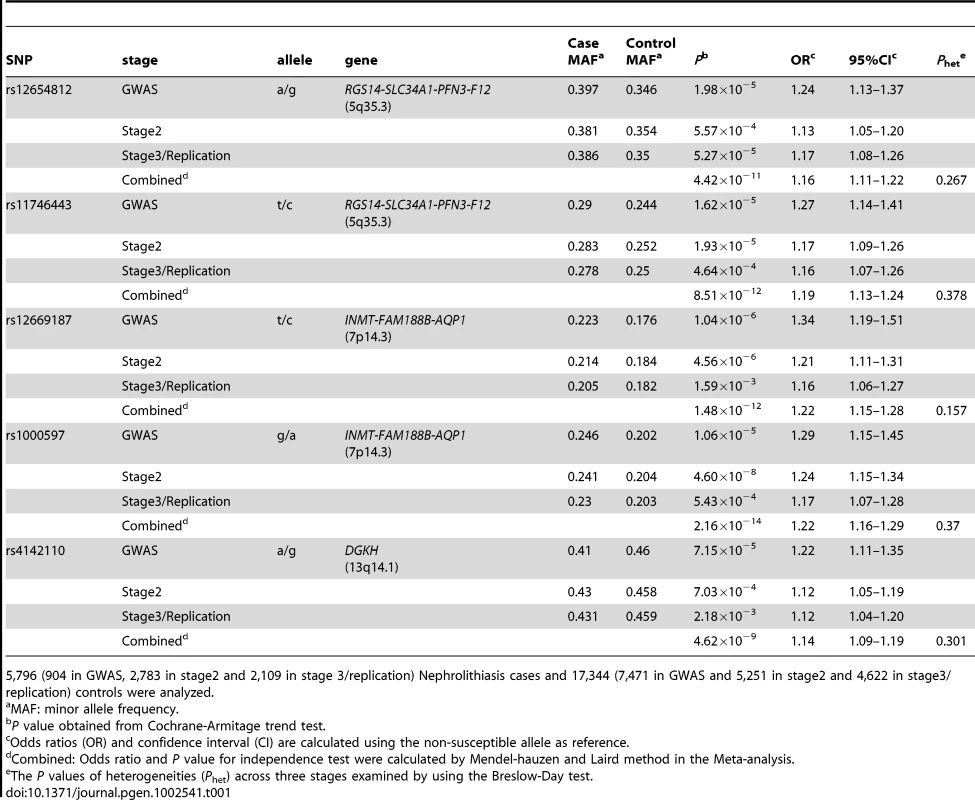

Tab. 1. Summary of GWAS and replication analyses.

5,796 (904 in GWAS, 2,783 in stage2 and 2,109 in stage 3/replication) Nephrolithiasis cases and 17,344 (7,471 in GWAS and 5,251 in stage2 and 4,622 in stage3/replication) controls were analyzed. Multiple SNPs in 5q35 and 7p14 regions indicated the significant association with nephrolithiasis. SNP rs11746443 in 5q35 was in strong linkage disequilibrium with rs12654812 (D' = 0.992 and r2 = 0.600), while SNP rs1000597 in 7q14 was also in high linkage disequilibrium with rs12669187 (D' = 0.87 and r2 = 0.64). To further evaluate the effects of these variations, we conducted the conditional analyses. As a result, all four SNPs remained to be significantly associated with nephrolithiasis (P<0.05, Table S6). These findings suggested that haplotypes carrying these SNPs would be associated with the risk of nephrolithiasis.

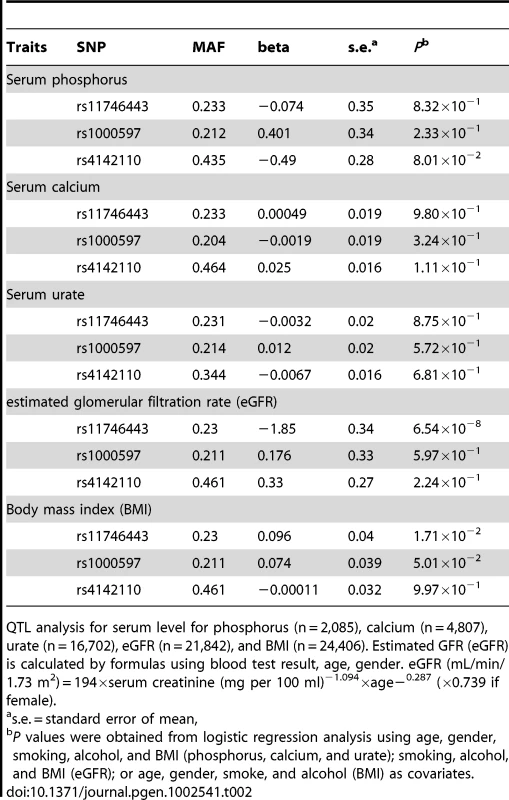

Then we selected the most significant SNPs from each of the three genomic region and examined the association of these SNPs with several clinical parameters [10], [11] which were shown to increase the risk of nephrolithiasis using up to a total of 27,323 independent Japanese samples [12]. We found no significant association of these SNPs with serum calcium, phosphorous, urate, and body mass index (BMI), but the risk allele of rs11746443 was significantly associated with the reduction of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (P = 6.54×10−8, Table 2). We also conducted subgroup analyses stratified by gender, age, and BMI status, and found that SNP rs11746443 exhibited stronger effect among individuals with higher BMI (>24, OR of 1.27) than those with lower BMI (<24, OR of 1.14). However this difference (P = 0.04) was not statistically significant after the multiple testing correction (Figure S5).

Tab. 2. QTL analysis for serum phosphorus, serum calcium, serum urate, eGFR, and BMI.

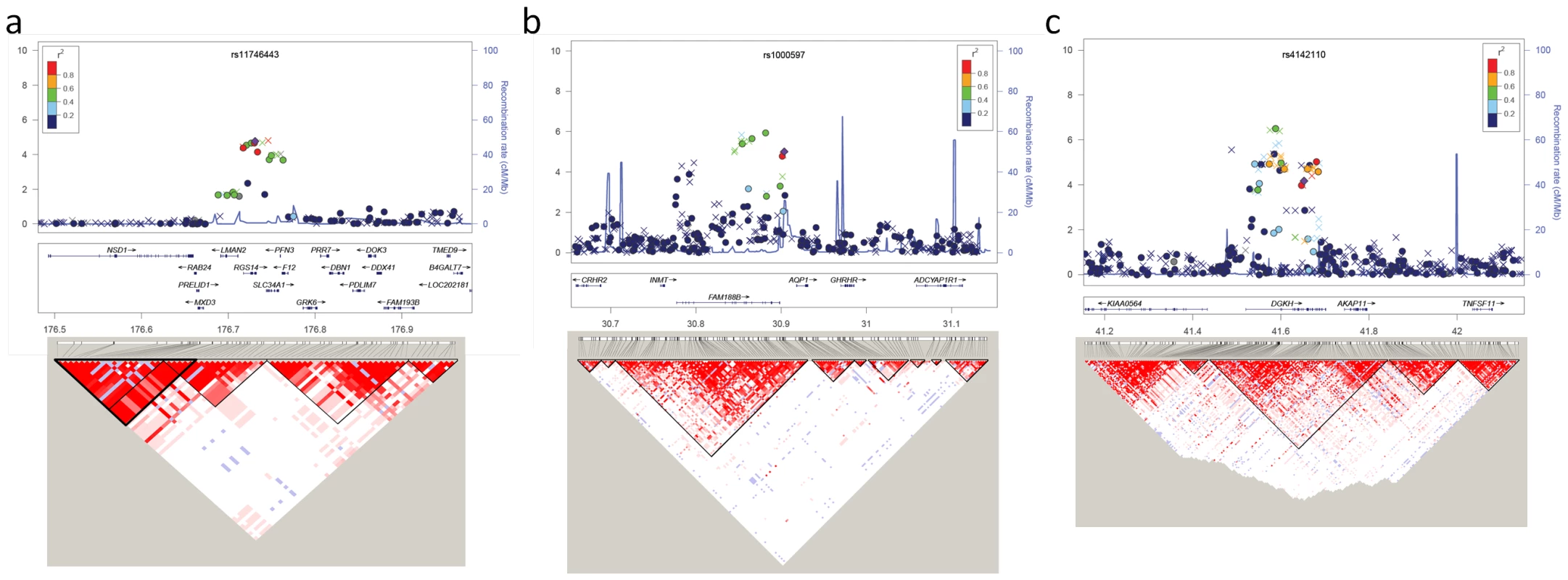

QTL analysis for serum level for phosphorus (n = 2,085), calcium (n = 4,807), urate (n = 16,702), eGFR (n = 21,842), and BMI (n = 24,406). Estimated GFR (eGFR) is calculated by formulas using blood test result, age, gender. eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) = 194×serum creatinine (mg per 100 ml)−1.094×age−0.287 (×0.739 if female). To further characterize these loci, we conducted imputation analyses of each genomic region in the GWAS samples (904 cases and 7,471 controls) using data from HAPMAP phase II (JPT). The regional association plots revealed that all modestly-associated SNPs are confined within an RGS14-SLC34A1-PFN3-F12 region on chromosome 5q35.3, an INMT-FAM188B-AQP1 region on 7p14.3, and a DGKH region on 13q14.1, respectively (Figure 1a, 1b, 1c and Figure S6a, S6b, S6c). The result of imputation analysis revealed that a SNP rs3812036 in intron 4 of SLC34A1 showed the strongest association with P-value of 1.48×10−5 among SNPs within the RGS14-SLC34A1-PFN3-F12 region (Figure S6a and Table S7). SLC34A1 encodes NPT2, a member of the type II sodium-phosphate co-transporter family which was highly expressed in kidney (Figure S7a). Mutations of SLC34A1 were known to cause hypophosphatemic nephrolithiasis and osteoporosis in human [13] and severe renal phosphate wasting and hypercalciuria in mice [14]. In addition, a GWAS reported previously revealed the association of variations on SLC34A1 locus with kidney function [15] and serum phosphorus concentration [16]. Although we did not find a significant association with serum phosphorus in Japanese population, the risk allele of SNP rs11746443 was associated with the reduction of eGFR, a marker of renal function, suggesting that variations in this region could regulate renal function and subsequently affect the risk of nephrolithiasis.

Fig. 1. Regional association plots at rs11746443, rs1000597, and rs4142110 loci.

(a–c) Upper panel; P-values of genotyped SNPs (circle) and imputed SNPs (cross) are plotted (as −log10 P-value) against their physical position on chromosome 5 (a), 7 (b), and 13(c) (NCBI Build 36). SNPs rs11746443 on 5q35 (a), rs1000597 on 7p14 (b), and rs4142110 on 13q14 (c) are represented by purple diamonds. The genetic recombination rates estimated from 1000 Genomes samples (JPT+CHB) are shown with a blue line. SNP's color indicates LD with rs11746443 (a), rs1000597 (b), and rs4142110 (c) according to a scale from r2 = 0 to r2 = 1 based on pair-wise r2 values from HapMap JPT. Middle Panel; Gene annotations from the University of California Santa Cruz genome browser. Lower Panel; We drew the LD map based on D' values using the genotype data of the cases and controls in the GWAS samples. The most significantly-associated SNP rs1000597 on chromosome 7p14.3 is located at 5.2 kb downstream of the FAM188B gene and at 14.2 kb upstream of the AQP1 gene which encodes aquaporin-1 (Figure S8a). The result of imputation analysis revealed that more than ten strongly associated SNPs were clustered around FAM188B region (Table S8a), however the role of FAM188B in the pathogenesis of nephrolithiasis was not reported so far. Aquaporin-1 was abundantly expressed in kidney (Figure S7b) and function as a water channel [17]. Moreover, Aqp1 null mice exhibited reduced osmotic water permeability in membrane of kidney proximal tube and became severely dehydrated after water deprivation, indicating the important role for aquaporin-1 in the urinary concentrating mechanism [17]. Interestingly, rs1000597 is also located within intron 6 of ENST00000434909, which is predicted to encode a 329-amino-acid protein consisting of the carboxy-terminal portion of FAM188B (residue 655–742) and the carboxy-terminal portion of aquaporin-1 (residue 29–269) (Figure S8b). Although the physiological roles of ENST00000434909 have not been characterized yet, quantitative real-time PCR analysis revealed that this gene was preferentially expressed in kidney (Figure S8c). Taken together, SNP rs1000597 is likely to be associated with regulation of AQP1 and/or ENST00000434909 expression, and subsequently affect the urine-concentration process and increase the risk of nephrolithiasis.

SNP rs4142110 on DGKH was also indicated strong association by the meta-analysis of three studies. DGKH was expressed in brain (Figure S7c) and possibly elated to psychiatric disorders such as bipolar and major depressive disease [18], [19], but its involvement in renal function or calcium homeostasis has not been reported. Although several SNPs on chromosome 13p14.1 including rs7981733 showed stronger association with nephrolithiasis than rs4142110 in GWAS and imputation analysis (Table S8b), none of these associated SNPs alter amino acid sequence. Therefore, further association and functional analyses would be essential to elucidate the role of this variation in the etiology of nephrolithiasis.

The CLDN14 gene was shown to be associated with nephrolithiasis in the previous GWAS in Caucasian [8], but SNPs rs219778 and rs219781 did not exhibit significant association (P = 0.937 and 0.630, respectively), while SNP rs219780 was not polymorphic in Japanese. However SNP rs2835349 which is located at 19 kb upstream of the CLDN14 gene was included in the top 100 SNPs in our GWAS (P = 6.33×10−5 with OR of 1.22, Figure S9). SNP rs2835349 did not achieve the threshold of the first replication analysis (P<8.47×10−4) but revealed some trend of the association with P-value of 3.29×10−3 and OR of 1.10 (Table S9). To further investigate the association of this variation with nephrolithiasis, we genotyped rs2835349 using stage 3 cohort. Although rs2835349 failed to show the replication of association with P-value of 0.624 and OR of 0.98 (95% C.I. of 0.94–1.10), metanalysis of three studied indicated the suggestive association (P = 5.72×10−4 and OR of 1.10). Taken together, CLDN14 would be a common genetic locus for nephrolithiasis in both Caucasian and Japanese populations.

Then we conducted the multiple logistic regression analysis of three significant variations (rs11746443, rs1000597, and rs4142110) including age, gender, and BMI as covariates. As a result, these variations remained as factors that were strongly associated with nephrolithiasis with OR of 1.18 (95% confidence interval (C.I.) of 1.12–1.25), 1.21 (95% C.I. of 1.14–1.27), and 1.14 (95% C.I. of 1.09–1.19), respectively (Table S10), indicating these SNPs as an independent risk factors. Therefore, we examined cumulative effect of these variations using weighted genetic risk score (wGRS) as describe previously [20]. We defined 4 categories by using the mean and SD of control samples (Group 1: less than −1S.D. (<0.127), Group 2: between −1S.D. and mean (0.127–0.309), Group 3 between mean and +1S.D. (0.309–0.490), Group 4: more than +1S.D. (0.490<)). As a result, we found that individuals in Group 4 have 1.95-fold higher risk of nephrolithiasis than those in Group 1 (Table S11a, S11b). These results indicated the cumulative effect of these variations.

Through the GWAS and two sets of replication studies using a total of 5,892 cases and 17,809 controls, we identified three significantly-associated loci for nephrolithiasis. Although the molecular mechanisms how these variations could increase the risk of nephrolithiasis should be further investigated, our results elucidated crucial roles of genetic factors related with renal function as well as pathogenesis of nephrolithiasis. Nephrolithiasis is considered as one of lifestyle-related diseases; low fluid intake, low dietary calcium, and high dietary salt have been shown to increase the disease risk. However the results of dietary intervention studies to reduce the recurrence incidence of nephrolithiasis has been unsuccessful [21]. We think that our findings would contribute to the better understanding of pathogenesis of nephrolithiasis and lead to the development of new innovative therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All subjects provided written informed consent. This project was approved by the ethical committees at the Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo, and Center for Genomic Medicine, Institutes of Physical and Chemical Research (RIKEN).

Samples

Characteristics of each cohort are shown in Table S1. In this study, we conducted GWAS and two subsequent replication analyses using a total of 5,892 nephrolithiasis cases and 17,809 control subjects. All case samples and 16786 of non-nephrolithiasis case-mix control subjects were obtained from BioBank Japan project, “the Leading Project for Personalized Medicine” in the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology [22]. We excluded patients with struvite, cystine, ammonium acid urate, and uric acid stone. Patients with secondary nephrolithiasis caused by drugs, hyperparathyroidism, or congenital anomalies of urinary tract were also excluded. We excluded the subjects with a history of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia from controls, because these diseases were shown to be a risk factor for nephrolithiasis [23]. We also obtained 1023 Japanese control DNAs from healthy volunteers from the Osaka-Midosuji Rotary Club, Osaka, Japan. A total of 27,323 Japanese samples from Biobank Japan were used for the QTL analyses of serums calcium, phosphorus, urate, BMI and eGFR.

SNP genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using a standard method. In the GWAS, a total of 1000 cases and 7,936 non-nephrolithiasis controls (cerebral aneurysm, primary sclerosing cholangitis, esophageal cancer, uterine body cancer chronic obstructive pulmonary, glaucoma, and healthy volunteers) were genotyped at 712,726 SNPs using Human Omni Express (Figure S1). We performed a standard quality control procedure to exclude SNPs with low call rate (<99%), P-value of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test of <1.0×10−6 in controls, and minor allele frequency (MAF) of <0.01 in each stage. Finally, we analyzed 556,249 SNPs in GWAS. In stage2, we genotyped 2,783 cases and 5,251 non-nephrolithiasis controls (epilepsy, atopic dermatitis, and Grave's disease) by using multiplex PCR-based Invader assay (Third Wave Technologies) or Human Omni Express, respectively. In replication/stage 3, we genotyped 2,109 cases and 4,622 non-nephrolithiasis controls (chronic hepatitis C, liver cancer, and colon cancer) using multiplex PCR-based Invader assay (Third Wave Technologies). For the QTL analyses, we genotyped 27,323 samples using Illumina HumanHap610-Quad Genotyping BeadChip as described previously [24].

Statistical analysis

The association of SNPs with nephrolithiasis in each stage was tested by a 1-degree-of-freedom Cochran-Armitage trend test using PLINK [25]. The genomic inflation factor λ was calculated using all the tested SNPs in the GWAS. The quantile-quantile plot was drawn using R program. The Odds ratios were calculated using the non-susceptible allele as reference, unless it was stated otherwise elsewhere. The combined analysis of GWAS and the replication stages was performed utilizing the Mantel-Haenszel method. In this study, we set genome wide significance threshold of 5×10−8 in meta-analysis of all stages [26], [27]. We also assumed a significant level of 7.85×10−5 (TOP 100 SNPs) in GWAS, 8.47×10−4 (0.05/59) in stage2, and 5.00×10−3 (0.05/10) in stage 3, respectively. We selected SNPs which satisfied all these four criteria. Heterogeneity across three stages was examined by using the Breslow-Day test [28]. The statistical power is 31.6% in GWAS (P = 7.85×10−5), 96.38% in stage2 (P = 0.05/59), 95.54% in stage3 (P = 0.05/10), and 99.37% in all stage (P = 5.00×10−8) at minor allele frequency of 0.3 and Odd ratio of 1.2. For multiple logistic regression analysis at rs11746443, rs1000597 and rs4142110, we considered age at recruitment, gender, and BMI as covariates using the R program.

Imputation analysis

We used a Hidden Markov model programmed in MACH [29] and haplotype information from HapMap JPT samples to infer the genotypes of untyped SNPs in the GWAS. We applied the same SNP quality criteria as in GWAS for selecting SNPs for the analysis. The association was tested by 1-degree-of-freedom Cochran-Armitage trend test.

Serum calcium, phosphorus, urate, BMI, and a kidney functional index of eGFR analysis

We assessed the effect of genetic variations on serum calcium, phosphorus, urate, BMI, and eGFR, as described previously [30]. In brief, we used the genotyping result from 27,323 Japanese individuals with various diseases those were genotyped by using the Illumina Human610-Quad BeadChip. Since three significant SNPs (rs11746443, rs1000597, and rs4142110) were not included in Illumina Human610-Quad BeadChip, genotype data of these SNPs were determined by imputation using the MACH software. We compared the data from imputation analysis and that form direct sequencing for SNPs rs11746443, rs1000597 and rs4142110 using 94 samples. The concordance rates were 100% for rs1000597 and rs4142110 and 97.7% for rs11746443. All the samples were obtained from Biobank Japan. For serum calcium, phosphorus and urate, a linear regression model was used to analyze the associations of quantitative traits with SNP genotypes by incorporating age, gender, alcohol, smoking status, and BMI as covariates. For BMI, a linear regression model was used to analyze the associations of quantitative traits with SNP genotypes by incorporating age, gender, alcohol, smoking status as covariates. GFR was estimated using the following formula [31]: eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) = 194×serum creatinine (mg per 100 ml)−1.094×age−0.287 (×0.739 if female). For eGFR, a linear regression model was used to analyze the associations of quantitative traits with SNP genotypes by incorporating alcohol, smoking status, as covariates.

Quantitative real-time PCR

mRNA or total RNA from normal tissues were purchased from Calbiochem and BioChain. cDNAs were synthesized with the SuperScript Preamplification System (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted using the SYBR Green I Master on a LightCycler 480 (Roche). The primer sequences are indicated in Table S12. ENST00000434909 cDNA was amplified with a primer pair encompassing the region containing from exon 5 to exon7. Gene structure of ENST00000434909 was confirmed by direct sequencing of PCR product.

The weighted Genetic Risk Score (wGRS)

The wGRS was calculated by multiplying the number of risk alleles for each SNP by weight for that SNP (the natural log of the odds ratio for each allele) (Table S11a), and then taking the sum across the 3 SNPs according to the following formula:Where i is the SNP, wi is the weight for SNPi, and Xi is the number of risk alleles (0, 1 or 2).

Software

For general statistical analysis, we employed R statistical environment version 2.9.1 (cran.r-project.org) or plink-1.06 (pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/∼purcell/plink/). The Haploview software version 4.2 [32] was used to calculate LD and to draw Manhattan plot. Primer3 -web v0.3.0 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu) web tool was used to design primers. We employed LocusZoom (http://csg.sph.umich.edu/locuszoom/) for plotting regional association plots. We used SNP Functional Prediction [33] web tool for functional annotation of SNPs (http://snpinfo.niehs.nih.gov/snpfunc.htm). We used MACTH [34] web tool for searching potential binding sites for transcription factors (http://www.gene-regulation.com/index.htm).

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. YoshidaOTeraiAOhkawaTOkadaY 1999 National trend of the incidence of urolithiasis in Japan from 1965 to 1995. Kidney Int 56 1899 1904

2. StrohmaierWL 2000 Course of calcium stone disease without treatment. What can we expect? Eur Urol 37 339 344

3. CoeFLEvanAWorcesterE 2005 Kidney stone disease. J Clin Invest 115 2598 2608

4. ZilbermanDEYongDAlbalaDM The impact of societal changes on patterns of urolithiasis. Curr Opin Urol 20 148 153

5. TaylorENStampferMJCurhanGC 2005 Obesity, weight gain, and the risk of kidney stones. JAMA 293 455 462

6. CurhanGCWillettWCRimmEBStampferMJ 1997 Family history and risk of kidney stones. J Am Soc Nephrol 8 1568 1573

7. GoldfarbDSFischerMEKeichYGoldbergJ 2005 A twin study of genetic and dietary influences on nephrolithiasis: a report from the Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry. Kidney Int 67 1053 1061

8. ThorleifssonGHolmHEdvardssonVWaltersGBStyrkarsdottirU 2009 Sequence variants in the CLDN14 gene associate with kidney stones and bone mineral density. Nat Genet 41 926 930

9. Yamaguchi-KabataYNakazonoKTakahashiASaitoSHosonoN 2008 Japanese population structure, based on SNP genotypes from 7003 individuals compared to other ethnic groups: effects on population-based association studies. Am J Hum Genet 83 445 456

10. TeraiAOkadaYOhkawaTOgawaOYoshidaO 2000 Changes in the incidence of lower urinary tract stones in japan from 1965 to 1995. Int J Urol 7 452 456

11. ChouYHSuCMLiCCLiuCCLiuME 2011 Difference in urinary stone components between obese and non-obese patients. Urol Res 39 283 287

12. KamataniYMatsudaKOkadaYKuboMHosonoN 2010 Genome-wide association study of hematological and biochemical traits in a Japanese population. Nature Genetics 42 210 U225

13. PriéDHuartVBakouhNPlanellesGDellisO 2002 Nephrolithiasis and osteoporosis associated with hypophosphatemia caused by mutations in the type 2a sodium-phosphate cotransporter. N Engl J Med 347 983 991

14. BeckLKaraplisACAmizukaNHewsonASOzawaH 1998 Targeted inactivation of Npt2 in mice leads to severe renal phosphate wasting, hypercalciuria, and skeletal abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 5372 5377

15. KöttgenAPattaroCBögerCAFuchsbergerCOldenM 2010 New loci associated with kidney function and chronic kidney disease. Nat Genet 42 376 384

16. KestenbaumBGlazerNLKöttgenAFelixJFHwangSJ 2010 Common genetic variants associate with serum phosphorus concentration. J Am Soc Nephrol 21 1223 1232

17. MaTYangBGillespieACarlsonEJEpsteinCJ 1998 Severely impaired urinary concentrating ability in transgenic mice lacking aquaporin-1 water channels. J Biol Chem 273 4296 4299

18. BerridgeMJ 1989 The Albert Lasker Medical Awards. Inositol trisphosphate, calcium, lithium, and cell signaling. JAMA 262 1834 1841

19. BarnettJHSmollerJW 2009 The genetics of bipolar disorder. Neuroscience 164 331 343

20. De JagerPLChibnikLBCuiJReischlJLehrS 2009 Integration of genetic risk factors into a clinical algorithm for multiple sclerosis susceptibility: a weighted genetic risk score. Lancet Neurol 8 1111 1119

21. FinkHAAkornorJWGarimellaPSMacDonaldRCuttingA 2009 Diet, fluid, or supplements for secondary prevention of nephrolithiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur Urol 56 72 80

22. NakamuraY 2007 The BioBank Japan Project. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 5 696 697

23. SakhaeeK 2008 Nephrolithiasis as a systemic disorder. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 17 304 309

24. OkadaYHirotaTKamataniYTakahashiAOhmiyaH 2011 Identification of nine novel loci associated with white blood cell subtypes in a Japanese population. PLoS Genet 7 e1002067 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002067

25. PurcellSNealeBTodd-BrownKThomasLFerreiraM 2007 PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 81 559 575

26. McCarthyMIAbecasisGRCardonLRGoldsteinDBLittleJ 2008 Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nature reviews Genetics 9 356 369

27. Pe'erIYelenskyRAltshulerDDalyMJ 2008 Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genetic epidemiology 32 381 385

28. BreslowNEDayNE 1987 Statistical methods in cancer research. Volume II–The design and analysis of cohort studies. IARC Sci Publ 1 406

29. ScottLJMohlkeKLBonnycastleLLWillerCJLiY 2007 A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science 316 1341 1345

30. KamataniYMatsudaKOkadaYKuboMHosonoN 2010 Genome-wide association study of hematological and biochemical traits in a Japanese population. Nat Genet 42 210 215

31. MatsuoSImaiEHorioMYasudaYTomitaK 2009 Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis 53 982 992

32. BarrettJFryBMallerJDalyM 2005 Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21 263 265

33. XuZTaylorJA 2009 SNPinfo: integrating GWAS and candidate gene information into functional SNP selection for genetic association studies. Nucleic Acids Res 37 W600 605

34. KelAEGösslingEReuterICheremushkinEKel-MargoulisOV 2003 MATCH: A tool for searching transcription factor binding sites in DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 31 3576 3579

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Physiological Notch Signaling Maintains Bone Homeostasis via RBPjk and Hey Upstream of NFATc1Článek Intronic -Regulatory Modules Mediate Tissue-Specific and Microbial Control of / TranscriptionČlánek Probing the Informational and Regulatory Plasticity of a Transcription Factor DNA–Binding DomainČlánek Repression of Germline RNAi Pathways in Somatic Cells by Retinoblastoma Pathway Chromatin ComplexesČlánek An Alu Element–Associated Hypermethylation Variant of the Gene Is Associated with Childhood ObesityČlánek Three Essential Ribonucleases—RNase Y, J1, and III—Control the Abundance of a Majority of mRNAsČlánek Genomic Tools for Evolution and Conservation in the Chimpanzee: Is a Genetically Distinct Population

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2012 Číslo 3- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Comprehensive Research Synopsis and Systematic Meta-Analyses in Parkinson's Disease Genetics: The PDGene Database

- Genomic Analysis of the Hydrocarbon-Producing, Cellulolytic, Endophytic Fungus

- Networks of Neuronal Genes Affected by Common and Rare Variants in Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Akirin Links Twist-Regulated Transcription with the Brahma Chromatin Remodeling Complex during Embryogenesis

- Too Much Cleavage of Cyclin E Promotes Breast Tumorigenesis

- Imprinted Genes … and the Number Is?

- Genetic Architecture of Highly Complex Chemical Resistance Traits across Four Yeast Strains

- Exploring the Complexity of the HIV-1 Fitness Landscape

- MNS1 Is Essential for Spermiogenesis and Motile Ciliary Functions in Mice

- A Fundamental Regulatory Mechanism Operating through OmpR and DNA Topology Controls Expression of Pathogenicity Islands SPI-1 and SPI-2

- Evidence for Positive Selection on a Number of MicroRNA Regulatory Interactions during Recent Human Evolution

- Variation in Modifies Risk of Neonatal Intestinal Obstruction in Cystic Fibrosis

- PIF4–Mediated Activation of Expression Integrates Temperature into the Auxin Pathway in Regulating Hypocotyl Growth

- Critical Evaluation of Imprinted Gene Expression by RNA–Seq: A New Perspective

- A Meta-Analysis and Genome-Wide Association Study of Platelet Count and Mean Platelet Volume in African Americans

- Mouse Genetics Suggests Cell-Context Dependency for Myc-Regulated Metabolic Enzymes during Tumorigenesis

- Transcriptional Control in Cardiac Progenitors: Tbx1 Interacts with the BAF Chromatin Remodeling Complex and Regulates

- Synthetic Lethality of Cohesins with PARPs and Replication Fork Mediators

- APOBEC3G-Induced Hypermutation of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type-1 Is Typically a Discrete “All or Nothing” Phenomenon

- Interpreting Meta-Analyses of Genome-Wide Association Studies

- Error-Prone ZW Pairing and No Evidence for Meiotic Sex Chromosome Inactivation in the Chicken Germ Line

- -Dependent Chemosensory Functions Contribute to Courtship Behavior in

- Diverse Forms of Splicing Are Part of an Evolving Autoregulatory Circuit

- Phenotypic Plasticity of the Drosophila Transcriptome

- Physiological Notch Signaling Maintains Bone Homeostasis via RBPjk and Hey Upstream of NFATc1

- Precocious Metamorphosis in the Juvenile Hormone–Deficient Mutant of the Silkworm,

- Igf1r Signaling Is Indispensable for Preimplantation Development and Is Activated via a Novel Function of E-cadherin

- Accurate Prediction of Inducible Transcription Factor Binding Intensities In Vivo

- Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Alters a Pathway in Strongly Resembling That of Bile Acid Biosynthesis and Secretion in Vertebrates

- Mammalian Neurogenesis Requires Treacle-Plk1 for Precise Control of Spindle Orientation, Mitotic Progression, and Maintenance of Neural Progenitor Cells

- Tcf7 Is an Important Regulator of the Switch of Self-Renewal and Differentiation in a Multipotential Hematopoietic Cell Line

- REST–Mediated Recruitment of Polycomb Repressor Complexes in Mammalian Cells

- Intronic -Regulatory Modules Mediate Tissue-Specific and Microbial Control of / Transcription

- Age-Dependent Brain Gene Expression and Copy Number Anomalies in Autism Suggest Distinct Pathological Processes at Young Versus Mature Ages

- A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Variants Underlying the Shade Avoidance Response

- -by- Regulatory Divergence Causes the Asymmetric Lethal Effects of an Ancestral Hybrid Incompatibility Gene

- Genome-Wide Association and Functional Follow-Up Reveals New Loci for Kidney Function

- A Natural System of Chromosome Transfer in

- Cell Size and the Initiation of DNA Replication in Bacteria

- Probing the Informational and Regulatory Plasticity of a Transcription Factor DNA–Binding Domain

- Repression of Germline RNAi Pathways in Somatic Cells by Retinoblastoma Pathway Chromatin Complexes

- Temporal Transcriptional Profiling of Somatic and Germ Cells Reveals Biased Lineage Priming of Sexual Fate in the Fetal Mouse Gonad

- Rapid Analysis of Genome Rearrangements by Multiplex Ligation–Dependent Probe Amplification

- Metabolic Profiling of a Mapping Population Exposes New Insights in the Regulation of Seed Metabolism and Seed, Fruit, and Plant Relations

- The Atypical Calpains: Evolutionary Analyses and Roles in Cellular Degeneration

- The Silkworm Coming of Age—Early

- Development of a Panel of Genome-Wide Ancestry Informative Markers to Study Admixture Throughout the Americas

- Balanced Codon Usage Optimizes Eukaryotic Translational Efficiency

- The Min System and Nucleoid Occlusion Are Not Required for Identifying the Division Site in but Ensure Its Efficient Utilization

- Neurobeachin, a Regulator of Synaptic Protein Targeting, Is Associated with Body Fat Mass and Feeding Behavior in Mice and Body-Mass Index in Humans

- Statistical Analysis of Readthrough Levels for Nonsense Mutations in Mammalian Cells Reveals a Major Determinant of Response to Gentamicin

- Gene Reactivation by 5-Aza-2′-Deoxycytidine–Induced Demethylation Requires SRCAP–Mediated H2A.Z Insertion to Establish Nucleosome Depleted Regions

- The miR-35-41 Family of MicroRNAs Regulates RNAi Sensitivity in

- Genetic Basis of Hidden Phenotypic Variation Revealed by Increased Translational Readthrough in Yeast

- An Alu Element–Associated Hypermethylation Variant of the Gene Is Associated with Childhood Obesity

- Modelling Human Regulatory Variation in Mouse: Finding the Function in Genome-Wide Association Studies and Whole-Genome Sequencing

- Novel Loci for Adiponectin Levels and Their Influence on Type 2 Diabetes and Metabolic Traits: A Multi-Ethnic Meta-Analysis of 45,891 Individuals

- Polycomb-Like 3 Promotes Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Binding to CpG Islands and Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal

- Insulin/IGF-1 and Hypoxia Signaling Act in Concert to Regulate Iron Homeostasis in

- EMF1 and PRC2 Cooperate to Repress Key Regulators of Arabidopsis Development

- Three Essential Ribonucleases—RNase Y, J1, and III—Control the Abundance of a Majority of mRNAs

- Contrasted Patterns of Molecular Evolution in Dominant and Recessive Self-Incompatibility Haplotypes in

- A Machine Learning Approach for Identifying Novel Cell Type–Specific Transcriptional Regulators of Myogenesis

- Genomic Tools for Evolution and Conservation in the Chimpanzee: Is a Genetically Distinct Population

- Nos2 Inactivation Promotes the Development of Medulloblastoma in Mice by Deregulation of Gap43–Dependent Granule Cell Precursor Migration

- Intracranial Aneurysm Risk Locus 5q23.2 Is Associated with Elevated Systolic Blood Pressure

- Heritability and Genetic Correlations Explained by Common SNPs for Metabolic Syndrome Traits

- A Genome-Wide Association Study of Nephrolithiasis in the Japanese Population Identifies Novel Susceptible Loci at 5q35.3, 7p14.3, and 13q14.1

- DNA Damage in Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome Cells Leads to PARP Hyperactivation and Increased Oxidative Stress

- DNA Resection at Chromosome Breaks Promotes Genome Stability by Constraining Non-Allelic Homologous Recombination

- Genetic Analysis of Floral Symmetry in Van Gogh's Sunflowers Reveals Independent Recruitment of Genes in the Asteraceae

- A Splice Site Variant in the Bovine Gene Compromises Growth and Regulation of the Inflammatory Response

- Promoter Nucleosome Organization Shapes the Evolution of Gene Expression

- The Nucleoside Diphosphate Kinase Gene Acts as Quantitative Trait Locus Promoting Non-Mendelian Inheritance

- The Ciliogenic Transcription Factor RFX3 Regulates Early Midline Distribution of Guidepost Neurons Required for Corpus Callosum Development

- Phosphorylation of the RNA–Binding Protein HOW by MAPK/ERK Enhances Its Dimerization and Activity

- A Genome-Wide Scan of Ashkenazi Jewish Crohn's Disease Suggests Novel Susceptibility Loci

- Parkinson's Disease–Associated Kinase PINK1 Regulates Miro Protein Level and Axonal Transport of Mitochondria

- LMW-E/CDK2 Deregulates Acinar Morphogenesis, Induces Tumorigenesis, and Associates with the Activated b-Raf-ERK1/2-mTOR Pathway in Breast Cancer Patients

- Mapping the Hsp90 Genetic Interaction Network in Reveals Environmental Contingency and Rewired Circuitry

- Autoregulation of the Noncoding RNA Gene

- The Human Pancreatic Islet Transcriptome: Expression of Candidate Genes for Type 1 Diabetes and the Impact of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines

- Spo0A∼P Imposes a Temporal Gate for the Bimodal Expression of Competence in

- Antagonistic Regulation of Apoptosis and Differentiation by the Cut Transcription Factor Represents a Tumor-Suppressing Mechanism in

- A Downstream CpG Island Controls Transcript Initiation and Elongation and the Methylation State of the Imprinted Macro ncRNA Promoter

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- PIF4–Mediated Activation of Expression Integrates Temperature into the Auxin Pathway in Regulating Hypocotyl Growth

- Metabolic Profiling of a Mapping Population Exposes New Insights in the Regulation of Seed Metabolism and Seed, Fruit, and Plant Relations

- A Splice Site Variant in the Bovine Gene Compromises Growth and Regulation of the Inflammatory Response

- Comprehensive Research Synopsis and Systematic Meta-Analyses in Parkinson's Disease Genetics: The PDGene Database

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy