-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Coordinate Regulation of Mature Dopaminergic Axon Morphology by Macroautophagy and the PTEN Signaling Pathway

Macroautophagy is a conserved mechanism for the bulk degradation of proteins and organelles. Pathological studies have implicated defective macroautophagy in neurodegeneration, but physiological functions of macroautophagy in adult neurons remain unclear. Here we show that Atg7, an essential macroautophagy component, regulates dopaminergic axon terminal morphology. Mature Atg7-deficient midbrain dopamine (DA) neurons harbored selectively enlarged axonal terminals. This contrasted with the phenotype of DA neurons deficient in Pten – a key negative regulator of the mTOR kinase signaling pathway and neuron size – that displayed enlarged soma but unaltered axon terminals. Surprisingly, concomitant deficiency of both Atg7 and Pten led to a dramatic enhancement of axon terminal enlargement relative to Atg7 deletion alone. Similar genetic interactions between Atg7 and Pten were observed in the context of DA turnover and DA-dependent locomotor behaviors. These data suggest a model for morphological regulation of mature dopaminergic axon terminals whereby the impact of mTOR pathway is suppressed by macroautophagy.

Published in the journal: Coordinate Regulation of Mature Dopaminergic Axon Morphology by Macroautophagy and the PTEN Signaling Pathway. PLoS Genet 9(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003845

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003845Summary

Macroautophagy is a conserved mechanism for the bulk degradation of proteins and organelles. Pathological studies have implicated defective macroautophagy in neurodegeneration, but physiological functions of macroautophagy in adult neurons remain unclear. Here we show that Atg7, an essential macroautophagy component, regulates dopaminergic axon terminal morphology. Mature Atg7-deficient midbrain dopamine (DA) neurons harbored selectively enlarged axonal terminals. This contrasted with the phenotype of DA neurons deficient in Pten – a key negative regulator of the mTOR kinase signaling pathway and neuron size – that displayed enlarged soma but unaltered axon terminals. Surprisingly, concomitant deficiency of both Atg7 and Pten led to a dramatic enhancement of axon terminal enlargement relative to Atg7 deletion alone. Similar genetic interactions between Atg7 and Pten were observed in the context of DA turnover and DA-dependent locomotor behaviors. These data suggest a model for morphological regulation of mature dopaminergic axon terminals whereby the impact of mTOR pathway is suppressed by macroautophagy.

Introduction

Macroautophagy is an intracellular protein degradation mechanism that engulfs cytoplasmic constituents and entire organelles within double-membrane vesicles and delivers these to lysosomes [1], [2]. Genetic deletion of the essential macroautophagy components Atg5 or Atg7, during mouse central nervous system (CNS) development, leads to neuronal loss and inclusion formation [3], [4]. Furthermore, Atg7 deficiency confined to cerebellar Purkinje cells leads to dystrophic axons and subsequent cell death within several weeks [5], [6]. In addition to pathological roles, protein degradation pathways may also play important physiological functions in neurons. Several studies have underscored the role of cytoplasmic protein degradation through the ubiquitin-proteosome system (UPS) in the regulation of neuronal morphology and function [7]. However, the role of macroautophagy in this context is unclear.

A key regulator of neuronal morphology and size is PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) [8], [9], an intracellular lipid phosphatase that opposes phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) activity. Deletion of Pten in mouse hippocampus neurons disinhibits the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) signaling pathway, leading to morphological enlargement as well as altered synaptic plasticity and plasticity-related behaviors [10]–[13]. mTOR is a major activator of protein translation as well as a key inhibitor of macroautophagy, but the relative contribution of these different downstream mechanisms on neuronal size remain unclear. Thus, we hypothesized that altered macroautophagy may play a role in the regulation of neuronal morphology and function in the mammalian CNS, either downstream of or in conjunction with the PTEN/PI3K/mTOR pathway.

Cell size regulation in the mammalian CNS appears to be highly dependent on developmental stage, cell type, and subcellular region. The deletion of Pten at embryonic stages leads to a profound enlargement of neurons and glia [10], [11], whereas the deletion at later developmental stages – such as postnatally or in young adult animals – appears to have a lesser impact [12], [13]. Postnatal deletion of Pten in certain neuronal subtypes fails to alter the size of neurite processes [13]–[15], suggesting selective subcellular and developmental regulatory mechanisms. For instance, deletion of Pten in post-mitotic midbrain dopamine (DA) neurons leads to soma hypertrophy, but axonal terminal morphology appears unaltered [14], [15].

Here we investigated the role of Atg7 and macroautophagy in the regulation of mature midbrain DA neuron morphology, and contrasted this with the impact of the PI3K/mTOR pathway. Atg7 deficiency in mature DA neurons led to enlargement of axon terminals, whereas DA neuron soma size was only modestly altered. This phenotype was distinct from that of Pten-deficient mature midbrain DA neurons, which showed robust soma hypertrophy but no significant alteration at axon terminals. Mature midbrain DA neurons deficient in both Pten and Atg7 showed a dramatic enhancement of the axon terminal enlargement phenotype seen with Atg7 deficiency alone. A similar synergistic genetic interaction was similarly observed between Pten and Atg7 in the context of DA metabolism (turnover) in the striatum, and with respect to DA-associated locomotor behaviors. Taken together, these data support a model whereby macroautophagy activity normally limits the impact of the PTEN/PI3K/mTOR pathway, such that mature dopaminergic axon terminals are unaffected by Pten loss. However in the absence of macroautophagy activity, the impact of the PI3K/mTOR pathway is unmasked and leads to a profound further enlargement.

Results

Generation of Atg7 deficient mice specifically within mature midbrain DA neurons

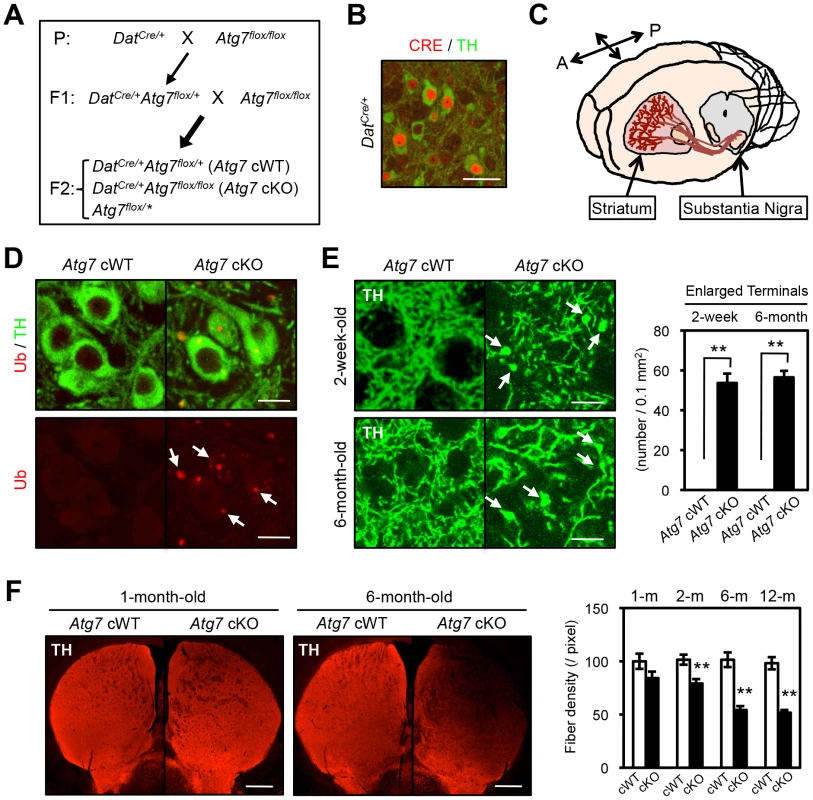

Mice deficient in Atg7 specifically within mature midbrain DA neurons (DatCre/+Atg7flox/flox [Atg7 cKO]) were generated [16] by interbreeding mice that express Cre recombinase (CRE) under the dopamine transporter promoter (DatCre/+, Figure 1B) [17] with mice that harbor Atg7 allele flanked by loxP sites (Atg7flox/flox, Figure 1A) [18]. Mutant animals appeared grossly normal and survival was not significantly altered (data not shown). To confirm alteration in macroautophagy activity, we initially quantified the lipidated conversion of LC3 (LC3-II), a marker for autophagosome formation that is dependent on Atg7, in crude extracts from 2-month-old midbrain tissues including substantia nigra (Figure 1C). LC3 conversion was significantly reduced in Atg7 cKO mouse midbrains (Figure S1A). Reduction in LC3-II was only partial, likely due to ATG7 activity in non-dopaminergic midbrain cells. Atg7 cKO mice displayed a normal number [16] and gross appearance of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-positive DA neurons in the substantia nigra at 1-month of age (Figure 1D). As shown in our prior paper, the number of TH-positive DA neurons, however, declined progressively from 2 month of age, and approximately 50% of TH-positive cells were lost by 1 year of age [16]. Furthermore, ubiquitin (Ub) - and p62-positive inclusions were apparent in Atg7 cKO DA neuron cell bodies and dendrites from 1-month of age (Figure 1D) [16].

Fig. 1. Enlarged axon terminals in TH-positive DA neurons of Atg7 cKO mice.

(A) Schema of mouse mating to obtain Atg7-deficient mice. Atg7 cKO mice and the littermate DatCre/+ (Atg7 cWT) animals were used for the analyses. Animals lacking Cre (Atg7flox/*) were not used in this study. Asterisk indicates ‘+’ or ‘flox’. (B) CRE immunohistochemistry in 4-week-old DatCre/+ midbrain. Nuclear CRE-positive staining (red) was seen in TH-positive (green) DA neurons, but not other cell types in the substantia nigra, not elsewhere in the CNS of cKO mice, and not in control Dat+/+ brain [59]. Bar, 20 µm. (C) TH-positive DA neurons in the midbrain substantia nigra project their axons into the striatum region. A, anterior; P, posterior. (D) Grossly normal appearance of Atg7 cKO midbrain DA neurons at the age of 1-month-old. Numerous Ub- and p62-positive [16] inclusions in Atg7 cKO soma and dendrites. Bar, 10 µm. (E) Enlarged TH-positive axon terminals (green) in the striatum of Atg7 cKO mice (arrows) at ages of 2-weeks and 6-months. Bars, 20 µm. (right) Quantification of the density of enlarged axon terminals. TH-positive axonal terminal enlargement in Atg7 cKO mouse striatum was apparent from 2-week of age, and did not progress with age (6-month). White, Atg7 cWT; Black, Atg7 cKO. n = 6 per group. **, p<0.01. (F) The fiber density of dopaminergic axon terminals in the striatum of Atg7 cKO mice at different ages. Dopaminergic axon terminals were visualized by anti-TH antibody staining (red). Bars, 500 µm. (right) Quantification of the density of TH-positive axonal shafts. The values were normalized by the fiber density of 1-month-old cWT animals. White, Atg7 cWT; Black, Atg7 cKO. n = 5∼6 per group. **, p<0.01. Midbrain DA neurons lacking Atg7 display enlarged axon terminals

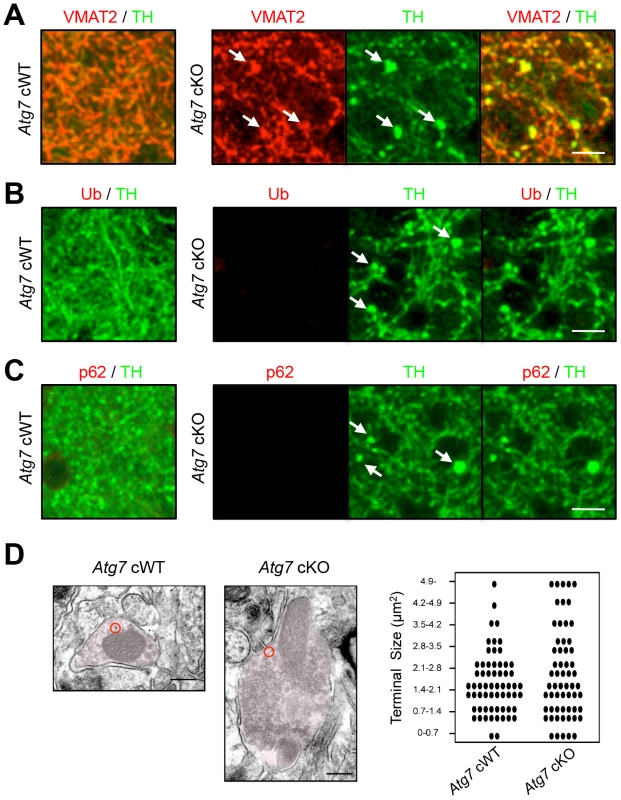

Grossly enlarged TH-positive dopaminergic axon terminal structures were observed at their striatal target in Atg7 cKO mice (Figure 1C, E). The axon terminal enlargement was apparent from 2 weeks of age, thus preceding other phenotypes observed in Atg7 cKO mice, and did not progress with age (Figure 1E). With aging, striatal fiber density of dopaminergic axon terminals declined slowly in Atg7 cKO mice (Figure 1F), which correlated with the slowly progressive loss of midbrain DA neuron as we have previously reported [16]. The enlarged axon terminals within the striatum were stained positively with an antibody to dopaminergic presynaptic component vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) (Figure 2A). In contrast to the soma inclusions (Figure 1D), the enlarged axon terminals were not stained with antibodies to Ub and p62 (Figure 2B, C).

Fig. 2. Characterization of enlarged TH-positive axon terminals of Atg7 cKO mice.

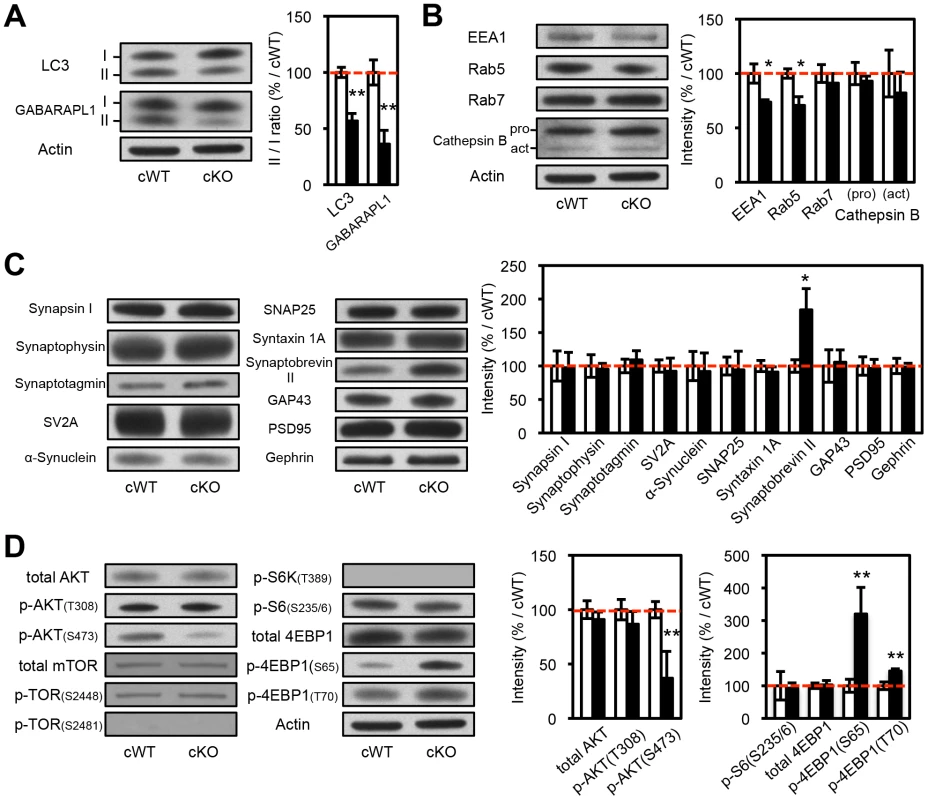

(A) Enlarged axon terminals in the striatum of 2-month-old Atg7 cKO mice were positive for the axon terminal proteins of midbrain DA neurons. Enlarged axon terminals (arrows in green) in Atg7 cKO mice were stained with VMAT2 (arrows in red). Bars, 10 µm. (B, C) Enlarged axon terminals in 2-month-old Atg7 cKO mice are Ub- and p62-negative. Enlarged axon terminals (arrows in green) in the striatum of Atg7 cKO mice were not stained with the markers for protein inclusions such as Ub (red in ‘B’) and p62 (red in ‘C’), suggesting that they are distinct from the inclusions seen in the cell somas of Atg7 cKO mice (Figure 1D). Bars, 10 µm. (D) Ultrastructural analysis of dopaminergic axon terminals in the striatum of 3-month-old Atg7 cWT or Atg7 cKO mice by immunoelectron microscopy with an antibody to TH. Red circles indicate the gold particle-conjugated anti-TH antibody. Bars, 200 nm. (right) Quantification of the size distribution of axon terminals in striatal sections. Each dot (•) represents approximately 1.6% of the total axon terminal number. n = 611 terminals for cWT and 592 terminals for cKO sections. Biochemical analysis of striatal synaptosomal preparations from 2-month-old Atg7 cKO mice and their littermates revealed predominantly unchanged levels of pre - and post-synaptic proteins including Synapsin I, Synaptophysin, Synaptotagmin, Synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A), α-Synuclein, Synaptosomal-associated protein 25 kDa (SNAP25), Syntaxin 1A, Growth associated protein 43 (GAP43), Postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95), and Gephrin (Figure 3C). Levels of early endosomal compartment markers present at presynaptic terminals, including early endosome antigen-1 (EEA1) and Rab5, were reduced, whereas late endosomal/lysosomal markers including Rab7 and Cathepsin B appeared unchanged (Figure 3B). An additional presynaptic marker protein, Synaptobrevin II, appeared increased in accumulation in Atg7 cKO synaptosomal preparations (Figure 3C). Thus, macroautophagy deficiency in midbrain DA neurons leads to axonal terminal enlargement associated with modest alternations in the accumulation of presynaptic regulatory proteins.

Fig. 3. Biochemical analyses of the protein extracts from the striatal synaptosomes of Atg7 cKO mice.

(A) Evidence for reduced macroautophagy activity in axon terminals of Atg7 cKO mice. Conversions of LC3-I and GABARAPL1-I into modified lipidated forms associated with autophagosome formation – termed LC3-II and GABARAPL1-II, respectively – were significantly decreased in striatal synaptosomal preparations from Atg7 cKO mice (relative to cWT mice); the incomplete reduction likely reflects the presence of non-dopaminergic axon terminals. White, Atg7 cWT; Black, Atg7 cKO. n = 5 per group. **, p<0.01. (B) Moderately reduced accumulation of early endosome markers in striatal synaptosomal preparations from Atg7 cKO mice. Both EEA1 and Rab5 are significantly decreased in striatal synaptosomal preparations from Atg7 cKO mice (relative to cWT mice), whereas late endosomal and lysosomal markers, Rab7 and Cathepsin B, unchanged. pro, procathepsin B; act, active mature Cathepsin B. Internal control Actin is same as Figure 3A. White, Atg7 cWT; Black, Atg7 cKO. n = 5 per group. *, p<0.05. (C) Selectively increased accumulation of Synaptobrevin II in striatal synaptosomal preparations from Atg7 cKO mice. Other synaptic markers were not significantly altered. Internal control Actin is same as Figure 3A. White, Atg7 cWT; Black, Atg7 cKO. n = 5 per group. *, p<0.05. (D) Non-canonical alterations of PI3K/mTOR pathway signaling in synaptosomal preparations from Atg7 cKO mice. Phosphorylation of AKT at Ser 473 (S473) was decreased in Atg7 cKO mice, whereas phosphorylation at Thr 308 (T308) unchanged. Phosphorylations of mTOR at Ser 2448 (S2448) or Ser 2481 (S2481) were unchanged in Atg7 cKO mice. Phosphorylations of 4EBP1 at Ser 65 (S65) and Thr 70 (T70) were increased in the striatal synaptosomes of Atg7 cKO mice, whereas phosphorylations of S6 (T389) and S6K (S235/236) were unchanged. Internal control Actin is same as Figure 3A. n = 5 per group. **, p<0.01. Consistent with these findings, immunoelectron microscopy for DA neuron marker, TH, showed significant enlargement of Atg7 deficient dopaminergic axon terminals but otherwise normal appearing morphology, including presynaptic terminals, synaptic vesicles, and mitochondria (Figure 2D). Furthermore, no inclusions or membrane swirls were apparent, in contrast to those described within dystrophic neuronal terminals in Atg7 deficient Purkinje neurons [5]. Thus, the morphology phenotype does not appear to be a consequence of the accumulation of unfolded protein in the context of aberrant degradation, nor represent dystrophic changes as described in other neuronal populations deficient in Atg7 [5].

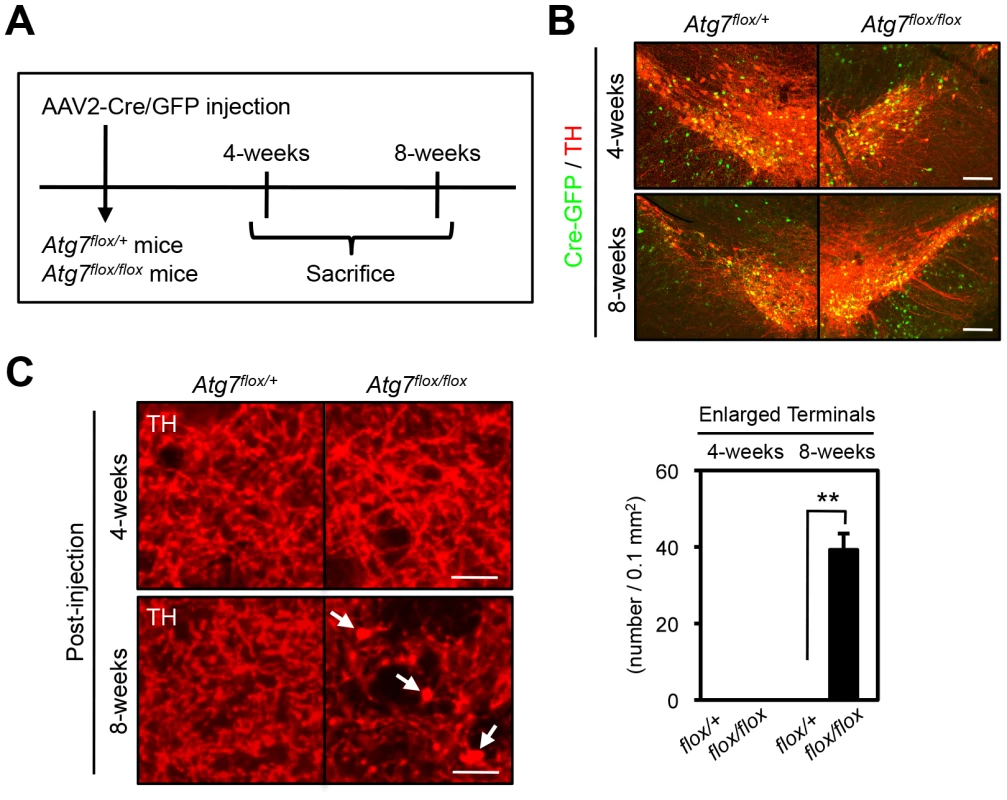

We sought to further address whether the axon terminal morphological change in the context of Atg7 deficiency is a consequence of altered development or altered maintenance of mature axon terminals. Thus, adult 2-month-old Atg7flox/flox mice, which remain intact for Atg7 expression, were stereotaxically injected with adeno-associated virus-2 (AAV2) that harbors Cre/green fluorescence protein (GFP) or GFP control into the ventral midbrain unilaterally (Figure 4A), effectively transducing a large fraction of TH-positive DA neurons (Figure 4B). Analysis of these mice 8 weeks after viral transduction revealed the dramatic enlargement of dopaminergic axon terminals within the striatum only of the AAV2-Cre/GFP virus transduced Atg7flox/flox mice (Figure 4C), consistent with the phenotype in Atg7 cKO mice. Thus, these studies confirm a role for Atg7 in the morphological plasticity of mature dopaminergic axon terminals.

Fig. 4. Atg7 regulates morphological plasticity of mature dopaminergic axon terminals.

(A) Scheme of AAV2-Cre/GFP viral transduction of adult Atg7flox/flox substantia nigra. Eight-week-old Atg7flox/+ and Atg7flox/flox mice were stereotactically injected with AAV2-Cre/GFP viral solution, and sacrificed 4- or 8-weeks later. (B) AAV2-Cre/GFP viral transduction of substantia nigra led to prominent GFP fluorescence (green) in a majority of TH-positive DA neurons (red) at 4- or 8-weeks after the injection; no GFP fluorescence was seen in untransduced animals (data not shown). (C) Transduction of Cre/GFP virus into adult Atg7flox/flox substantia nigra reproduced the enlarged axon terminal phenotype seen in Atg7 cKO mice. At 8-weeks after injection, enlarged TH-positive axon terminals (arrows) were seen in the striatum of Atg7flox/flox mice injected with AAV2-Cre/GFP viral solution. No enlarged axon terminals were seen in the striatum of Atg7flox/+ mice with AAV2-Cre/GFP virus or Atg7flox/flox mice with control AAV2-GFP virus lacking Cre. Bars, 20 µm. (right) Quantification of the density of enlarged axon terminals in mice injected with AAV2-Cre/GFP virus. TH-positive axon terminal enlargement in Atg7flox/flox mouse striatum was seen at 8-weeks after the AAV2-Cre/GFP virus injection. White, Atg7flox/+; Black, Atg7flox/flox. n = 3 per group. **, p<0.01. In addition to the axon terminal enlargement, at time points as early as 1-month of age, morphometric analysis of TH-positive cell soma in Atg7 cKO mice (or Atg7 cWT mice) revealed a significant albeit minor increase in soma size (15% increase, Figure 5A, B). This phenotype appeared similar in older animals (and thus not age-dependent; Figure 5A), and thus was not correlated with the neurodegenerative phenotype seen with aging.

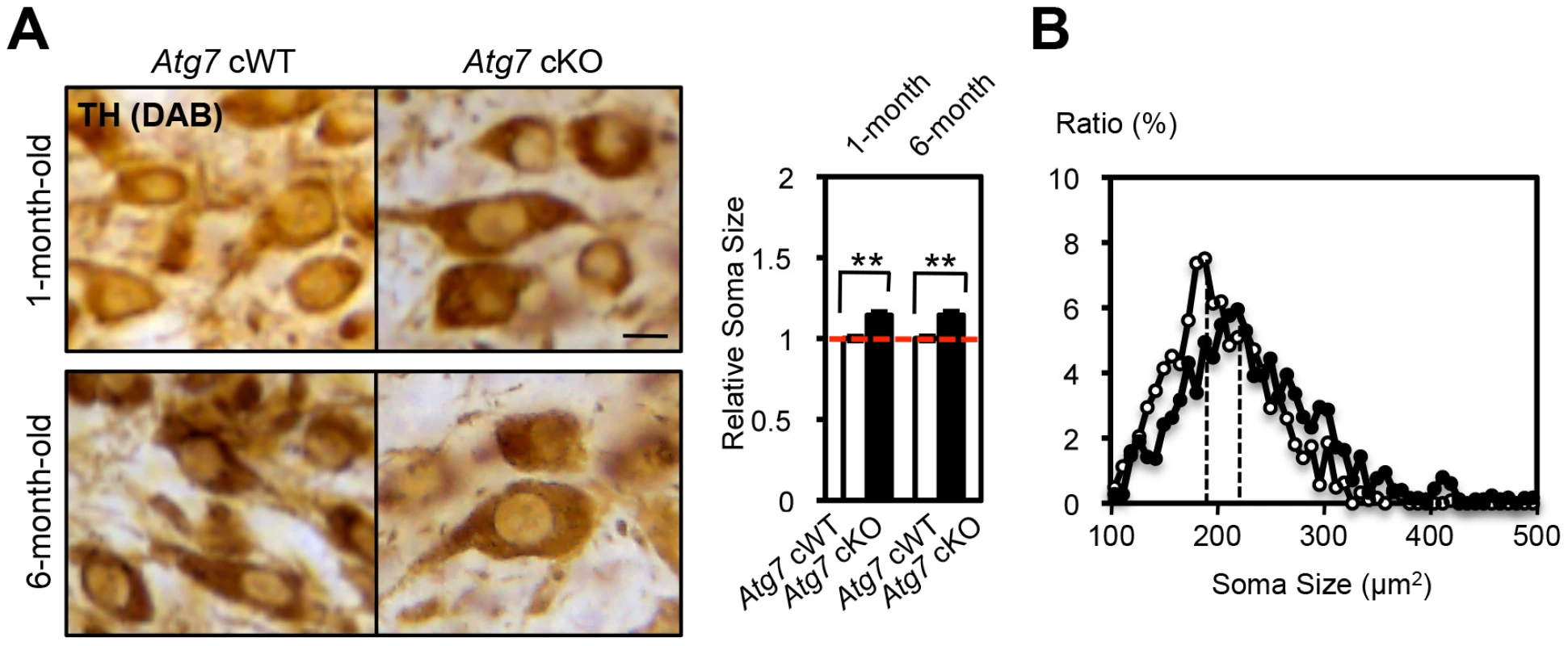

Fig. 5. Enlarged soma size in TH-positive DA neurons of Atg7 cKO mice.

(A) Enlarged cell soma of TH-positive DA neurons in Atg7 cKO mice. The soma area (brown in pictures) of nigral TH-positive DA neurons in Atg7 cKO mice (black in graph) was approximately 15% larger than that in Atg7 cWT mice (white in graph), as quantified using Image-J software (Image J, Bethesda, MD) and presented relative to the area of the Atg7 cWT group. Bars, 10 µm. (Atg7 cWT mice = 1.0); n = 194 to 377 TH-positive DA neurons per group. **, p<0.01. (B) The distribution of cell soma size of TH-positive DA neurons in Atg7 cWT and Atg7 cKO mice. The soma size of TH-positive DA neurons in Atg7 cKO mice (black circle) was on average approximately 15% larger than that in Atg7 cWT mice (white circle). As axon terminal enlargement appeared non-progressive and was not associated with intracellular inclusions or other apparent pathological changes, this was unlikely to be secondary to the late-onset progressive degeneration seen in midbrain DA neurons of Atg7 cKO mice [19], [20]. We note that in vitro studies using primary midbrain cultures prepared from Atg7 cKO or littermate cWT embryos further support this interpretation. TH-positive DA neurons in Atg7 cKO cultures at day 5 in vitro (5th DIV) displayed increased total neurite length (Figure S1B). Importantly, TH-positive DA neuron number and appearance was otherwise not altered in the Atg7 cKO primary cultures (Figure S1B), and thus this early phenotype is not likely to reflect degeneration.

mTOR pathway modification in Atg7 deficient dopaminergic axon terminals

The mTOR kinase signaling pathway is a key regulator of mammalian cell size [8], [9], [21]–[23]. As mTOR is also a major negative regulator of macroautophagy [24], we hypothesized that Atg7 may function in a common pathway with mTOR, or parallel to mTOR, in the context of dopaminergic axon terminal size regulation. To this end, we evaluated mTOR pathway activation within dopaminergic axon terminal projections in the striatum of Atg7 cKO or cWT mice. Crude striatal synaptosomal protein fractions were prepared and analyzed by Western blotting. As expected, Atg7 cKO synaptosomes displayed evidence of reduced macroautophagy, as the lipidation of LC3 (as well as of the related autophagosome marker protein GABARAPL1) was reduced (Figure 3A). However, the pattern of mTOR pathway component modification was not consistent with canonical activation of the PI3K/mTOR pathway. Phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4EBP1), a downstream target and effector of mTOR signaling [25], was significantly increased at Ser 65 and Thr 70 in Atg7 cKO mice (Figure 3D), but phosphorylation of other typical downstream targets of mTOR – ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) (Thr 389) and S6 (Ser 235/236) – appeared unchanged (Figure 3D). Furthermore, canonical PI3K pathway-associated modifications of mTOR kinase – in terms of the accumulation of phospho-mTOR (Ser 2448 and Ser 2481; Figure 3D, 6C) – or of the upstream PI3K pathway component AKT kinase (Ser 473), were not evident in Atg7 cKO striatum (Figure 3D). Taken together, these findings argue against a simple model whereby Atg7 deficiency may modify axonal process morphology through the modification of PI3K/mTOR downstream pathway (Figure S3A). A caveat to the interpretation of mTOR pathway modification using striatal synaptosome extracts is that non - dopaminergic axon terminals are also present; however, Atg7 deletion was restricted to midbrain DA neurons.

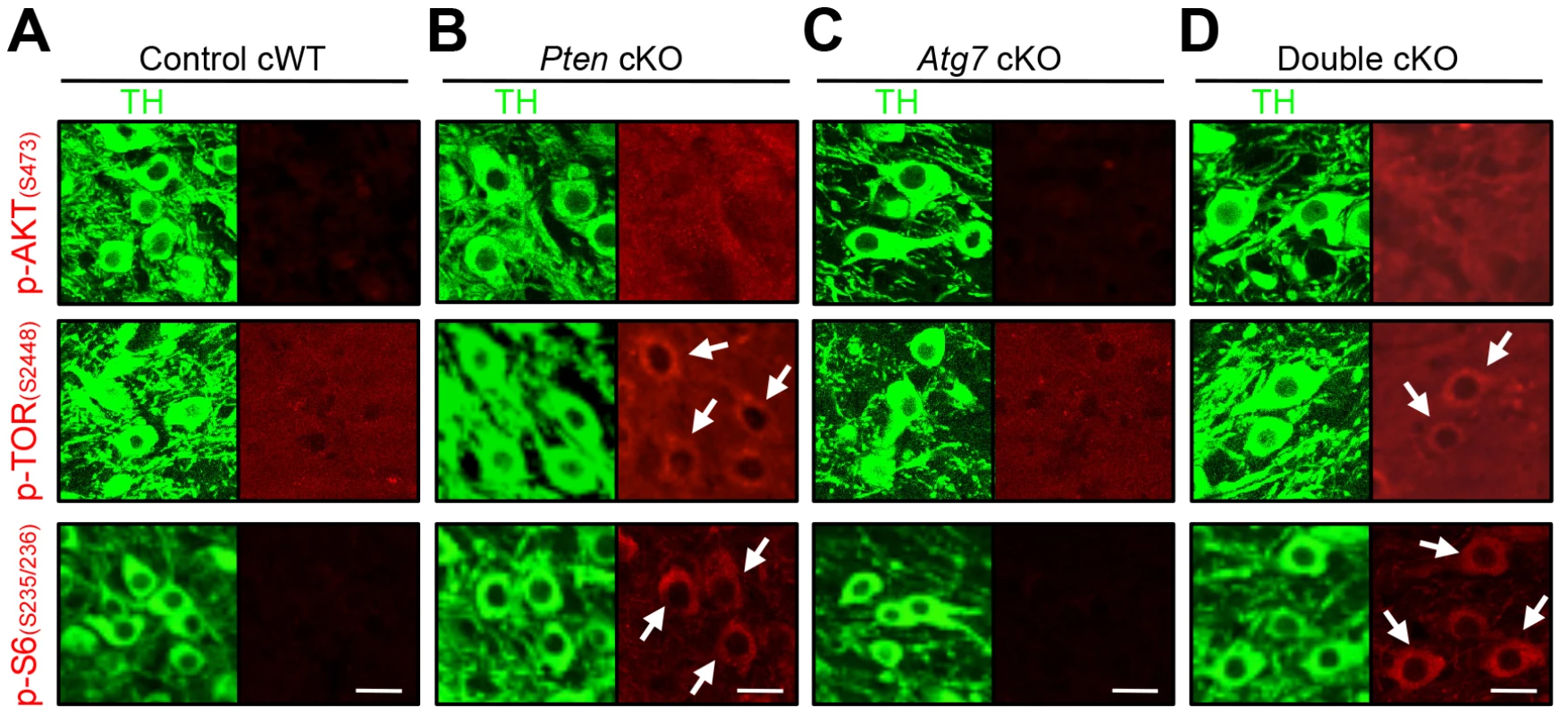

Fig. 6. Characterization of PI3K/mTOR pathways in TH-positive DA neurons of Atg7 and/or Pten cKO mice.

PI3K/mTOR pathway signaling, in terms of accumulation of phospho-AKT (S473), phospho-TOR (S2448), and phospho-S6 (S235/236) as indicated (in red) were unchanged in the TH-positive (green) midbrain DA neurons of Atg7 cKO mice (C), whereas these markers were increased in TH-positive DA neurons of Pten cKO and Atg7/Pten double cKO mice (arrows in B and D). (A) Control cWT mice, (B) Pten cKO mice, (C) Atg7 cKO mice, and (D) Atg7/Pten double cKO mice. Scale bars, 10 µm. Pten deficient midbrain DA neurons display enlarged cell soma but unaltered axon terminals

We next sought to more directly compare the roles of PI3K/mTOR pathway modification and macroautophagy in the context of dopaminergic axon terminal size. To this end, we generated mice deficient in Pten specifically within midbrain DA neurons (DatCre/+Ptenflox/flox [Pten cKO]). As expected, Pten cKO midbrain sections displayed canonical activation of PI3K/mTOR pathway, quantified in terms of accumulation of phospho-AKT at Ser 473, phospho-mTOR at Ser 2448 and phospho-S6 at Ser 235/236 (Figure 6A, B) [14], [15]. In contrast with Atg7 cKO mice, Pten cKO mice displayed no significant alteration in axon terminal size in the striatum (Figure 7C) [14]. Nonetheless, Pten cKO mice displayed robustly increased soma size of DA neurons (30% increase, Figure 7D), consistent with two prior studies of Pten deficiency [14], [15], and which was much more profound than the modest soma alteration in the context of Atg7 deficiency (Figure 7D). Thus, although both Pten deficiency and Atg7 deficiency modify cell morphology, the phenotypes are distinct, and thus the effect of Atg7 deficiency cannot simply reflect altered PI3K/mTOR pathway activation alone.

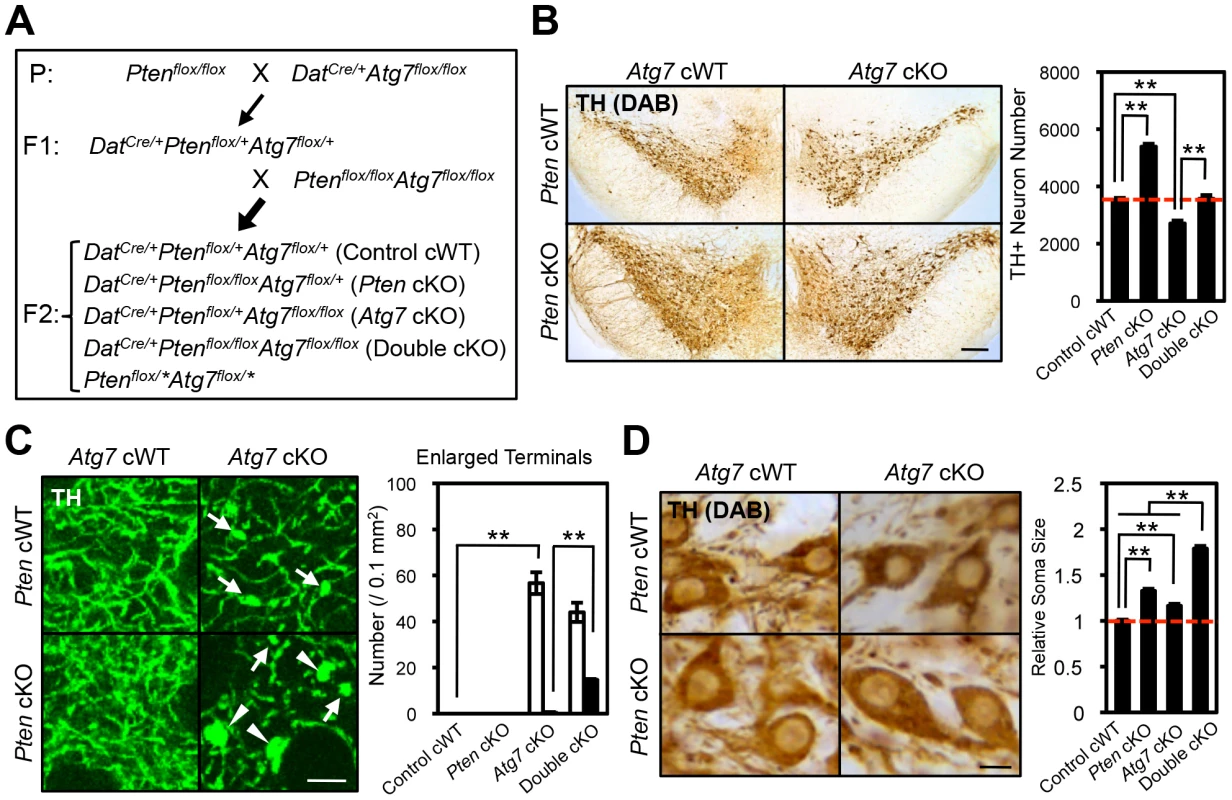

Fig. 7. Atg7 and Pten double deficiency synergistically increases axon terminal size in midbrain DA neurons.

(A) Schema of mouse mating to obtain Atg7 and Pten double deficient mice. DatCre/+ background animals were used for the analyses. Animals lacking Cre (Ptenflox/*Atg7flox/*) were not used in this study. Asterisk indicates ‘+’ or ‘flox’. (B) Neurodegeneration in Atg7 cKO mice was rescued by secondary deletion of Pten. Secondary Pten deletion (Atg7/Pten double cKO) suppressed the loss of TH-positive DA neurons in the substantia nigra of 2-month-old Atg7 cKO mice. Representative TH-stained midbrain sections are presented. Bar, 250 µm. (right) Quantification of TH-positive DA neuron number in the substantia nigra of Atg7/Pten double cKO mice. n = 4 per genotype. **, p<0.01. (C) The enlarged axon terminal phenotype of Atg7 cKO mice was greatly enhanced in Atg7/Pten double cKO mice, whereas Pten deficiency alone (Pten cKO) did not significantly change the axon terminal size. (left) Giant (arrowheads, >9.8 µm2) and moderately enlarged (arrows, 4.4∼9.8 µm2) axon terminals were seen in the striatum of Atg7/Pten double cKO mice, whereas only moderately enlarged axon terminals (arrows) were seen in Atg7 cKO mice and no enlarged axon terminals were seen in Pten cKO mice. Bars, 20 µm. (right) Quantification of enlarged axon terminal distribution. Black bar, giant terminals (>9.8 µm2); white bar, moderately enlarged terminals (4.4∼9.8 µm2). n = 6 per genotype. **, p<0.01. (D) The soma of TH-positive DA neurons in Atg7/Pten double cKO mice were dramatically enlarged (79% increase versus control cWT) relative to Atg7 cKO mice (15% increase versus control cWT) and Pten cKO mice (32% increase versus control cWT). (left) Representative sections stained with anti-TH antibody. Bars, 10 µm. (right) Quantification of the average cell size, presented as a fraction of DA neuron soma size in control cWT mice. n = 290∼417 TH-positive DA neurons per genotype. **, p<0.01. Synergistic enlargement of axon terminal size in Atg7 and Pten double deficient DA neurons

To further consider the genetic relationship of Atg7 and Pten in the context of axon morphology, we generated double mutant mice lacking both Atg7 and Pten specifically in midbrain DA neurons (Atg7/Pten double cKO), and compared these to single cKO mice (either Atg7 cKO or Pten cKO alone) as well as to control cWT mice (Figure 7A). PI3K/mTOR pathway activation was apparent in the Atg7/Pten double cKO mice, as expected, with accumulation of phospho-AKT at Ser 473, phospho-mTOR at Ser 2448, and phsopho-S6 at Ser 235/236 in midbrain DA neurons (Figure 6D) comparable to that observed in the Pten single cKO mice (Figure 6B). Surprisingly, dopaminergic axon terminals were dramatically larger in the double cKO mice than those in Atg7 cKO mice or control animals (Figure 7C, giant axon terminals). These giant axon terminals in Atg7/Pten double cKO mice were positive to VMAT2, but negative to Ub and p62 (data not shown). Atg7/Pten double cKO mice also showed mildly potentiated soma enlargement (79% increase, Figure 7D) relative to either single cKO mice. Thus, PI3K/mTOR pathway activation alone is not sufficient to modify dopaminergic axon terminal size, but its impact is unmasked in the context of Atg7 deficiency (Figure 8E). A further consequence of Pten deficiency in the context of Atg7 loss is that subsequent progressive midbrain DA neuron degeneration, as seen in 2-month-old Atg7 cKO mice and thereafter, is suppressed (Figure 7B). As such ‘rescue’ of neurodegeneration in Atg7/Pten double cKO mice failed to prevent the enlarged axon terminal phenotype (but instead actually enhanced the enlargement; Figure 7C), this further validates the notion that axon terminal enlargement in Atg7 cKO mice is not a consequence of neurodegeneration.

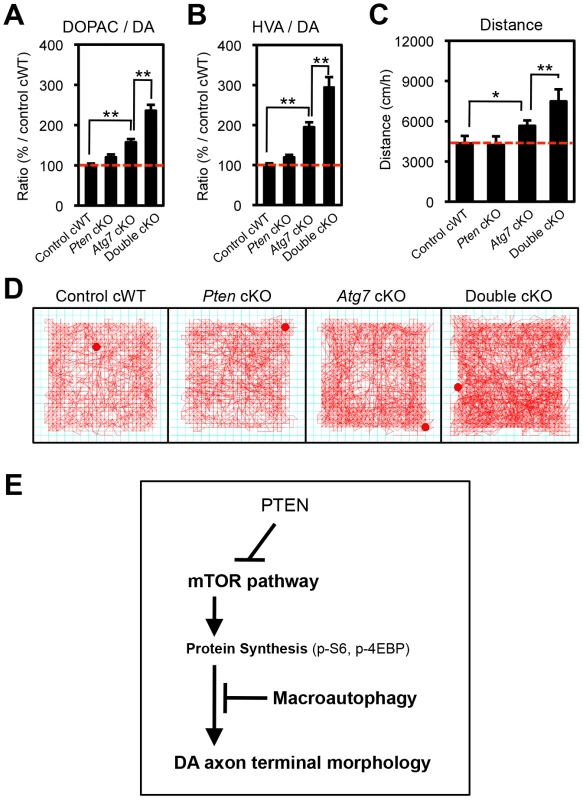

Fig. 8. Atg7 and Pten double deficiency synergistically increases DA turnover and DA-associated behaviors.

(A, B) DA turnover, quantified as the ratio of the DA metabolites DOPAC or HVA to DA (DOPAC/DA [A] or HVA/DA [B]) was synergistically increased in Atg7/Pten double cKO mice. The concentrations of DA, DOPAC, and HVA are shown in Figures S2A–C. n = 10∼12 per genotype. **, p<0.01. (C, D) Basal locomotor activity was synergistically increased in Atg7/Pten double cKO mice. Traces (‘D’) display total distance traveled over a 30-min period in an open field environment. Walking velocity was unchanged (Figure S2D). n = 10∼12 per genotype. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01. (E) In midbrain DA neurons at baseline, Atg7-mediated macroautophagy inhibits the enlargement of dopaminergic axon terminals, in part by masking the impact of the PTEN/PI3K/mTOR pathway. Also see Figure S3. Synergistic impact of Atg7 and Pten deficiency on DA metabolism and DA-associated locomotion

The studies above detail a synergistic role for Atg7 and Pten in the regulation of DA neuron morphology. We sought to expand the synergistic effects to functional changes in Atg7 cKO mice. Striatal DA accumulation and its metabolites, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and homovanillic acid (HVA), were quantified in 3-month-old single and double mutant mice (Figure S2A–C). DA turnover (DOPAC/DA and HVA/DA) in the striatum, which is a reflection of dopaminergic axon terminal activity, was increased in Atg7 cKO mice (relative to control cWT mice; Figure 8A, B). This phenotype was further enhanced in Atg7/Pten double cKO mice, whereas Pten cKO alone appeared normal (Figure 8A, B), mirroring the morphological findings. The absolute level of DA accumulation, in contrast to DA turnover, was significantly reduced in Atg7 cKO mice (Figure S2A), which may reflect cell loss at this age. However, this reduction in DA levels was not ‘rescued’ by PTEN loss (Figure S2A).

Given the altered DA accumulation in Atg7 cKO mice, as well as prior studies demonstrating physiological changes in these animals [26], we sought to identify possible behavioral correlates. To this end, basal locomotor activity was quantified in an open field chamber that was novel to the animals over a 30-min period. Ambulatory distance travelled was increased in Atg7 cKO mice (relative to control cWT mice; Figure 8C, D). This phenotype was further enhanced in Atg7/Pten double cKO mice (Figure 8C, D), whereas Pten single cKO mice behavior did not appear significantly altered (Figure 8C, D) [14]. Other activity parameters, including jump counts and vertical activity, appeared similarly altered in the Atg7 cKO mice and Atg7/Pten double cKO mice (Figure S2E, F). In contrast, velocity of ambulation was not altered (Figure S2D). Thus, Atg7 single cKO and Atg7/Pten double cKO mice displayed alterations in motor behavior that correlated with their cellular changes and alterations in DA turnover.

Discussion

The PTEN/PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway plays a central role in the regulation of neuronal morphology and size in developing vertebrate and invertebrate species [8], [9], [21], [22]. However, a number of studies have provided evidence that in the context of the mature mammalian CNS, as well as within certain subcellular compartments of neurons such as at axonal processes, the impact of the PTEN//PI3K/mTOR pathway on size can be highly regulated. For instance, although deletion of PTEN in post-mitotic DA neurons leads to enlarged soma (Figure 7D) [14], [15], dopaminergic axon terminals are not altered (Figure 7C) [14], [15]. In contrast to these observations, PTEN deletion at earlier developmental stages or in other neuronal types, such as in the progenitors of dentate gyrus granule neurons [10], [11], leads to prominent enlargement of axon terminals as well as soma. Thus, mechanisms that regulate the impact of the PI3K/mTOR pathway on neuronal morphology are of particular interest. Here we show that deletion of the essential macroautophagy component Atg7 unmasks the impact of Pten deletion on dopaminergic axon terminal size. These data implicate macroautophagy as a negative regulator of PTEN/PI3K/mTOR pathway regulation of neuronal morphology (Figure 8E).

Although the precise mechanism by which Pten deletion or PI3K pathway activation leads ultimately to cellular hypertrophy remains unclear, multiple studies in Drosophila [27] and mice [23], [28], [29] have implicated activation of the ribosomal protein S6 by a family of related kinases that include S6K1 and S6K2, leading to increased protein translation [30]. As neither S6 phosphorylation nor activation of S6K appeared modified in the context of Atg7 deficiency (Figure 3D), the axonal process enlargement seen with macroautophagy deficiency is likely to be through a distinct mechanism. Our genetic studies strongly validate this notion, as PI3K/mTOR pathway activation (by means of PTEN deficiency) and Atg7 deficiency act cooperatively and synergistically in modifying axon terminal morphology. We favor an interpretation whereby at the axonal terminus, macroautophagy-mediated protein degradation is typically able to overcome the increased protein production in the context of mTOR pathway activation, and thus macroautophagy typically suppresses the impact of Pten deletion on dopaminergic axon terminal size. However, in the context of defective macroautophagy with Atg7 deficiency, the impact of Pten deletion is unmasked (Figure 8E). In addition to suppressing PTEN/PI3K/mTOR pathway-mediated regulation, macroautophagy likely plays additional roles in determining dopaminergic axon terminal size and function, as the impact of Atg7 deficiency was observed regardless of Pten deficiency (Figure 7C).

Our data argue against an alternative model whereby mTOR pathway activation dictates dopaminergic axon terminal morphology through the downstream inhibition of macroautophagy (rather than through downstream effects on the translation machinery) (Figure S3A), as has been suggested based on the recent in vitro analyses of acutely prepared striatal slice preparations treated with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin [26]. The impact of the PTEN/PI3K/mTOR pathway on mature dopaminergic axon terminal morphology in our present study was apparent in the complete absence of macroautophagy (when comparing Atg7 single mutant mice with Atg7/Pten double mutant mice), and thus the mechanism of action cannot be explained simply by alterations in macroautophagy activity. It remains possible that alterations in macroautophagy activity play some role downstream of mTOR pathway activation in the context of more acute physiological changes at axon terminals [26]. Nonetheless, our findings support a distinct model whereby macroautophagy plays a key role in suppressing the impact of mTOR pathway activation in the context of mature dopaminergic axon terminals (Figure 8E).

Previous studies have reported that midbrain DA neuron-specific Atg7 loss [19], as well as loss of Atg7 in other neuronal classes, leads to enlarged but dystrophic axons [5], [6]. These findings have generally been interpreted as secondary effects of the accumulation of pathological inclusions (‘engorgement’). However, in our analyses of Atg7 deficient midbrain DA neurons, dopaminergic axon terminal enlargement preceded degeneration, appeared non-progressive (Figure 1E), and was not associated with protein aggregates (Figure 2B, C). Furthermore, this phenotype was enhanced – rather than suppressed – in the context of additional Pten deficiency (Atg7/Pten double deficient animals) (Figure 7C), although such additional Pten deficiency effectively suppressed the late-onset degeneration phenotype of the Atg7 deficient midbrain DA neurons (Figure 7B) [16].

Prior studies in invertebrate species have suggested a role for macroautophagy in axon terminal morphology. For instance, at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction (NMJ), macroautophagy has been reported to promote synapse development through selective degradation of the Highwire ubiquitin ligase [31]. Mutations in C. elegans unc-51 –a macroautophagy regulator – lead to developmental axonal defects [32]. There is also precedent of a role for macroautophagy in cell size homeostasis: induction of macroautophagy by Atg1 leads to the reduced Drosophila fat body cell size in TOR signaling-dependent manner [33]. In mammalian models, loss of macroautophagy-associated proteins other than Atg7 has similarly been implicated in axonal morphology, although the mechanism has remained unclear. Mammalian Ulk1/2, orthologues of Unc51, have been reported to regulate axonal outgrowth [34]–[36]. Taken together, we speculate that regulation of axon terminal size by macroautophagy may play an important role in structural plasticity at mature adult axon terminals. Extrinsic cues such as glial derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) impact dopaminergic axon terminal structures and modify signaling through the PI3K pathway [37], [38]; it will be of interest to pursue the role of macroautophagy in such changes, which have been implicated clinically in pathological movements associated with experimental therapeutics for Parkinson's disease [39]–[42].

Future studies will seek to identify specific molecular components that may mediate dopaminergic axon terminal enlargement in the context of defective macroautophagy. Our initial screen of known axon terminal proteins revealed the increased accumulation of Synaptobrevin II in the context of Atg7 deficient dopaminergic axon terminal preparations (Figure 3C). In addition to proteins, macroautophagy also plays a role in cell membrane regulation [43], and this may also impact axon terminal morphology. Finally, it is interesting to note that axon terminal morphology, DA neurons, and the PI3K pathway [44]–[47] have all been implicated in the etiology of autism spectrum disorders (ASD), which are characterized by cognitive difficulties and can be associated with hyperactivity 48,49. Furthermore, recent studies have suggested a role for alterations in the protein degradation machinery in ASD [50]–[52]. We thus speculate a role for macroautophagy regulation of axon terminal morphology in the context of brain disorders.

Materials and Methods

Animal

DatCre/+ mice, Atg7flox/flox mice, and Ptenflox/flox mice were generated previously [17], [18], [53]. All animals were maintained in the animal facility of Columbia University Medical Center. All of the experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. All mice we used were DatCre/+ background, as Dat heterozygous KO mice show some defects in their behavior and physiology [54].

Histology

Mice were perfused in 4% paraformaldehyde and 50 µm coronal sections were made by a vibratome. The antibodies used here were listed in Text S1.

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopic analysis was according to the previous paper [55] and Immunogold incubation protocol for general application (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA).

Cell size determination

After the TH staining of midbrain sections by DAB, pictures were taken at 400× magnification. The size of TH-neuron was measured manually by Image-J (NIH) [56]. More than 200 TH-neurons from 4 mice were analyzed per group.

Western blotting

Preparation of the striatal synaptosomal fractions was according to the previous paper [57]. The antibodies used here were listed in Text S1.

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

The striatal tissues were used for HPLC analysis. Concentrations of DA and its metabolites were measured according to the previous paper [58].

Statistical analysis

All of the comparisons were made with Mann-Whitney U-test (for 2 samples) or non-repeated measures ANOVA (for multiple samples). The values are expressed as the means ± SEM. A p value less than 0.05 is considered significant.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. LevineB, KlionskyDJ (2004) Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell 6 : 463–477.

2. KlionskyDJ (2006) Neurodegeneration: good riddance to bad rubbish. Nature 441 : 819–820.

3. HaraT, NakamuraK, MatsuiM, YamamotoA, NakaharaY, et al. (2006) Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature 441 : 885–889.

4. KomatsuM, WaguriS, ChibaT, MurataS, IwataJ, et al. (2006) Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature 441 : 880–884.

5. KomatsuM, WangQJ, HolsteinGR, FriedrichVLJr, IwataJ, et al. (2007) Essential role for autophagy protein Atg7 in the maintenance of axonal homeostasis and the prevention of axonal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 14489–14494.

6. NishiyamaJ, MiuraE, MizushimaN, WatanabeM, YuzakiM (2007) Aberrant membranes and double-membrane structures accumulate in the axons of Atg5-null Purkinje cells before neuronal death. Autophagy 3 : 591–596.

7. WanHI, DiAntonioA, FetterRD, BergstromK, StraussR, et al. (2000) Highwire regulates synaptic growth in Drosophila. Neuron 26 : 313–329.

8. BackmanSA, StambolicV, SuzukiA, HaightJ, EliaA, et al. (2001) Deletion of Pten in mouse brain causes seizures, ataxia and defects in soma size resembling Lhermitte-Duclos disease. Nat Genet 29 : 396–403.

9. KwonCH, ZhuX, ZhangJ, KnoopLL, TharpR, et al. (2001) Pten regulates neuronal soma size: a mouse model of Lhermitte-Duclos disease. Nat Genet 29 : 404–411.

10. KwonCH, LuikartBW, PowellCM, ZhouJ, MathenySA, et al. (2006) Pten regulates neuronal arborization and social interaction in mice. Neuron 50 : 377–388.

11. ChalhoubN, ZhuG, ZhuX, BakerSJ (2009) Cell type specificity of PI3K signaling in Pdk1 - and Pten-deficient brains. Genes Dev 23 : 1619–1624.

12. LuikartBW, SchnellE, WashburnEK, BensenAL, TovarKR, et al. (2011) Pten knockdown in vivo increases excitatory drive onto dentate granule cells. J Neurosci 31 : 4345–4354.

13. SperowM, BerryRB, BayazitovIT, ZhuG, BakerSJ, et al. (2012) Phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) regulates synaptic plasticity independently of its effect on neuronal morphology and migration. J Physiol 590 : 777–792.

14. Diaz-RuizO, ZapataA, ShanL, ZhangY, TomacAC, et al. (2009) Selective deletion of PTEN in dopamine neurons leads to trophic effects and adaptation of striatal medium spiny projecting neurons. PLoS One 4: e7027.

15. DomanskyiA, GeisslerC, VinnikovIA, AlterH, SchoberA, et al. (2011) Pten ablation in adult dopaminergic neurons is neuroprotective in Parkinson's disease models. FASEB J 25 : 2898–2910.

16. InoueK, RispoliJ, KaphzanH, KlannE, ChenEI, et al. (2012) Macroautophagy deficiency mediates age-dependent neurodegeneration through a phospho-tau pathway. Mol Neurodegener 7 : 48.

17. ZhuangX, MassonJ, GingrichJA, RayportS, HenR (2005) Targeted gene expression in dopamine and serotonin neurons of the mouse brain. J Neurosci Methods 143 : 27–32.

18. KomatsuM, WaguriS, UenoT, IwataJ, MurataS, et al. (2005) Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 169 : 425–434.

19. FriedmanLG, LachenmayerML, WangJ, HeL, PouloseSM, et al. (2012) Disrupted autophagy leads to dopaminergic axon and dendrite degeneration and promotes presynaptic accumulation of alpha-synuclein and LRRK2 in the brain. J Neurosci 32 : 7585–7593.

20. AhmedI, LiangY, SchoolsS, DawsonVL, DawsonTM, et al. (2012) Development and characterization of a new Parkinson's disease model resulting from impaired autophagy. J Neurosci 32 : 16503–16509.

21. LeeCH, InokiK, GuanKL (2007) mTOR pathway as a target in tissue hypertrophy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47 : 443–467.

22. BackmanS, StambolicV, MakT (2002) PTEN function in mammalian cell size regulation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 12 : 516–522.

23. KwonCH, ZhuX, ZhangJ, BakerSJ (2003) mTor is required for hypertrophy of Pten-deficient neuronal soma in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 : 12923–12928.

24. MizushimaN, KomatsuM (2011) Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 147 : 728–741.

25. HayN, SonenbergN (2004) Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev 18 : 1926–1945.

26. HernandezD, TorresCA, SetlikW, CebrianC, MosharovEV, et al. (2012) Regulation of presynaptic neurotransmission by macroautophagy. Neuron 74 : 277–284.

27. MontagneJ, StewartMJ, StockerH, HafenE, KozmaSC, et al. (1999) Drosophila S6 kinase: a regulator of cell size. Science 285 : 2126–2129.

28. NguyenKT, TajmirP, LinCH, LiadisN, ZhuXD, et al. (2006) Essential role of Pten in body size determination and pancreatic beta-cell homeostasis in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 26 : 4511–4518.

29. StilesBL, Kuralwalla-MartinezC, GuoW, GregorianC, WangY, et al. (2006) Selective deletion of Pten in pancreatic beta cells leads to increased islet mass and resistance to STZ-induced diabetes. Mol Cell Biol 26 : 2772–2781.

30. ChalhoubN, KozmaSC, BakerSJ (2006) S6k1 is not required for Pten-deficient neuronal hypertrophy. Brain Res 1100 : 32–41.

31. ShenW, GanetzkyB (2009) Autophagy promotes synapse development in Drosophila. J Cell Biol 187 : 71–79.

32. HedgecockEM, CulottiJG, ThomsonJN, PerkinsLA (1985) Axonal guidance mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans identified by filling sensory neurons with fluorescein dyes. Dev Biol 111 : 158–170.

33. ScottRC, JuhaszG, NeufeldTP (2007) Direct induction of autophagy by Atg1 inhibits cell growth and induces apoptotic cell death. Curr Biol 17 : 1–11.

34. TomodaT, KimJH, ZhanC, HattenME (2004) Role of Unc51.1 and its binding partners in CNS axon outgrowth. Genes Dev 18 : 541–558.

35. TodaH, MochizukiH, FloresR (2008) UNC-51/ATG1 kinase regulates axonal transport by mediating motor-cargo assembly. Genes Dev 22 : 3292–3307.

36. LohSH, FrancescutL, LingorP, BahrM, NicoteraP (2008) Identification of new kinase clusters required for neurite outgrowth and retraction by a loss-of-function RNA interference screen. Cell Death Differ 15 : 283–298.

37. ArevaloJC, WuSH (2006) Neurotrophin signaling: many exciting surprises!. Cell Mol Life Sci 63 : 1523–1537.

38. ReichardtLF (2006) Neurotrophin-regulated signalling pathways. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 361 : 1545–1564.

39. TomacA, LindqvistE, LinLF, OgrenSO, YoungD, et al. (1995) Protection and repair of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system by GDNF in vivo. Nature 373 : 335–339.

40. HudsonJ, GranholmAC, GerhardtGA, HenryMA, HoffmanA, et al. (1995) Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor augments midbrain dopaminergic circuits in vivo. Brain Res Bull 36 : 425–432.

41. RosenbladC, KirikD, BjorklundA (2000) Sequential administration of GDNF into the substantia nigra and striatum promotes dopamine neuron survival and axonal sprouting but not striatal reinnervation or functional recovery in the partial 6-OHDA lesion model. Exp Neurol 161 : 503–516.

42. RangasamySB, SoderstromK, BakayRA, KordowerJH (2010) Neurotrophic factor therapy for Parkinson's disease. Prog Brain Res 184 : 237–264.

43. ZhangM, SchekmanR (2013) Cell biology. Unconventional secretion, unconventional solutions. Science 340 : 559–561.

44. BourgeronT (2009) A synaptic trek to autism. Curr Opin Neurobiol 19 : 231–234.

45. DelormeR, EyE, ToroR, LeboyerM, GillbergC, et al. (2013) Progress toward treatments for synaptic defects in autism. Nat Med 19 : 685–694.

46. NakamuraK, SekineY, OuchiY, TsujiiM, YoshikawaE, et al. (2010) Brain serotonin and dopamine transporter bindings in adults with high-functioning autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67 : 59–68.

47. GadowKD, DevincentCJ, OlvetDM, PisarevskayaV, HatchwellE (2010) Association of DRD4 polymorphism with severity of oppositional defiant disorder, separation anxiety disorder and repetitive behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder. Eur J Neurosci 32 : 1058–1065.

48. TaurinesR, SchwenckC, WesterwaldE, SachseM, SiniatchkinM, et al. (2012) ADHD and autism: differential diagnosis or overlapping traits? A selective review. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 4 : 115–139.

49. RommelseNN, FrankeB, GeurtsHM, HartmanCA, BuitelaarJK (2010) Shared heritability of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 19 : 281–295.

50. GlessnerJT, WangK, CaiG, KorvatskaO, KimCE, et al. (2009) Autism genome-wide copy number variation reveals ubiquitin and neuronal genes. Nature 459 : 569–573.

51. BucanM, AbrahamsBS, WangK, GlessnerJT, HermanEI, et al. (2009) Genome-wide analyses of exonic copy number variants in a family-based study point to novel autism susceptibility genes. PLoS Genet 5: e1000536.

52. ScheuerleA, WilsonK (2011) PARK2 copy number aberrations in two children presenting with autism spectrum disorder: further support of an association and possible evidence for a new microdeletion/microduplication syndrome. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 156B: 413–420.

53. GroszerM, EricksonR, Scripture-AdamsDD, LescheR, TrumppA, et al. (2001) Negative regulation of neural stem/progenitor cell proliferation by the Pten tumor suppressor gene in vivo. Science 294 : 2186–2189.

54. SpielewoyC, BialaG, RoubertC, HamonM, BetancurC, et al. (2001) Hypolocomotor effects of acute and daily d-amphetamine in mice lacking the dopamine transporter. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 159 : 2–9.

55. MengualE, PickelVM (2004) Regional and subcellular compartmentation of the dopamine transporter and tyrosine hydroxylase in the rat ventral pallidum. J Comp Neurol 468 : 395–409.

56. MacLeodD, DowmanJ, HammondR, LeeteT, InoueK, et al. (2006) The familial Parkinsonism gene LRRK2 regulates neurite process morphology. Neuron 52 : 587–593.

57. TengL, CrooksPA, SonsallaPK, DwoskinLP (1997) Lobeline and nicotine evoke [3H]overflow from rat striatal slices preloaded with [3H]dopamine: differential inhibition of synaptosomal and vesicular [3H]dopamine uptake. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 280 : 1432–1444.

58. YangL, CalingasanNY, ChenJ, LeyJJ, BeckerDA, et al. (2005) A novel azulenyl nitrone antioxidant protects against MPTP and 3-nitropropionic acid neurotoxicities. Exp Neurol 191 : 86–93.

59. IwasatoT, NomuraR, AndoR, IkedaT, TanakaM, et al. (2004) Dorsal telencephalon-specific expression of Cre recombinase in PAC transgenic mice. Genesis 38 : 130–138.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Defending Sperm FunctionČlánek How to Choose the Right MateČlánek Conserved Translatome Remodeling in Nematode Species Executing a Shared Developmental TransitionČlánek Genome-Wide and Cell-Specific Epigenetic Analysis Challenges the Role of Polycomb in SpermatogenesisČlánek The Integrator Complex Subunit 6 (Ints6) Confines the Dorsal Organizer in Vertebrate EmbryogenesisČlánek Multiple bHLH Proteins form Heterodimers to Mediate CRY2-Dependent Regulation of Flowering-Time inČlánek Playing the Field: Sox10 Recruits Different Partners to Drive Central and Peripheral MyelinationČlánek A Minimal Nitrogen Fixation Gene Cluster from sp. WLY78 Enables Expression of Active Nitrogenase inČlánek Evolutionary Tuning of Protein Expression Levels of a Positively Autoregulated Two-Component System

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2013 Číslo 10- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Defending Sperm Function

- How to Choose the Right Mate

- A Mutation in the Gene in Labrador Retrievers with Hereditary Nasal Parakeratosis (HNPK) Provides Insights into the Epigenetics of Keratinocyte Differentiation

- Conserved Translatome Remodeling in Nematode Species Executing a Shared Developmental Transition

- A Novel Actin mRNA Splice Variant Regulates ACTG1 Expression

- Tracking Proliferative History in Lymphocyte Development with Cre-Mediated Sister Chromatid Recombination

- Correlated Occurrence and Bypass of Frame-Shifting Insertion-Deletions (InDels) to Give Functional Proteins

- Chimeric Protein Complexes in Hybrid Species Generate Novel Phenotypes

- Loss of miR-10a Activates and Collaborates with Activated Wnt Signaling in Inducing Intestinal Neoplasia in Female Mice

- Both Rare and Copy Number Variants Are Prevalent in Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum but Not in Cerebellar Hypoplasia or Polymicrogyria

- Reverse PCA, a Systematic Approach for Identifying Genes Important for the Physical Interaction between Protein Pairs

- Partial Deletion of Chromosome 8 β-defensin Cluster Confers Sperm Dysfunction and Infertility in Male Mice

- Genome-Wide and Cell-Specific Epigenetic Analysis Challenges the Role of Polycomb in Spermatogenesis

- Coordinate Regulation of Mature Dopaminergic Axon Morphology by Macroautophagy and the PTEN Signaling Pathway

- Cooperation between RUNX1-ETO9a and Novel Transcriptional Partner KLF6 in Upregulation of in Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- Mobility of the Native Conjugative Plasmid pLS20 Is Regulated by Intercellular Signaling

- FliZ Is a Global Regulatory Protein Affecting the Expression of Flagellar and Virulence Genes in Individual Bacterial Cells

- Specific Tandem Repeats Are Sufficient for Paramutation-Induced Trans-Generational Silencing

- Condensin II Subunit dCAP-D3 Restricts Retrotransposon Mobilization in Somatic Cells

- Dominant Mutations in Identify the Mlh1-Pms1 Endonuclease Active Site and an Exonuclease 1-Independent Mismatch Repair Pathway

- The Insulator Homie Promotes Expression and Protects the Adjacent Gene from Repression by Polycomb Spreading

- Human Intellectual Disability Genes Form Conserved Functional Modules in

- Coordination of Cell Proliferation and Cell Fate Determination by CES-1 Snail

- ORFs in Drosophila Are Important to Organismal Fitness and Evolved Rapidly from Previously Non-coding Sequences

- Different Roles of Eukaryotic MutS and MutL Complexes in Repair of Small Insertion and Deletion Loops in Yeast

- The Spore Differentiation Pathway in the Enteric Pathogen

- Acceleration of the Glycolytic Flux by Steroid Receptor Coactivator-2 Is Essential for Endometrial Decidualization

- The Human Nuclear Poly(A)-Binding Protein Promotes RNA Hyperadenylation and Decay

- Genome Wide Analysis Reveals Zic3 Interaction with Distal Regulatory Elements of Stage Specific Developmental Genes in Zebrafish

- Xbp1 Directs Global Repression of Budding Yeast Transcription during the Transition to Quiescence and Is Important for the Longevity and Reversibility of the Quiescent State

- The Integrator Complex Subunit 6 (Ints6) Confines the Dorsal Organizer in Vertebrate Embryogenesis

- Incorporating Motif Analysis into Gene Co-expression Networks Reveals Novel Modular Expression Pattern and New Signaling Pathways

- The Bacterial Response Regulator ArcA Uses a Diverse Binding Site Architecture to Regulate Carbon Oxidation Globally

- Direct Monitoring of the Strand Passage Reaction of DNA Topoisomerase II Triggers Checkpoint Activation

- Multiple bHLH Proteins form Heterodimers to Mediate CRY2-Dependent Regulation of Flowering-Time in

- A Reversible Histone H3 Acetylation Cooperates with Mismatch Repair and Replicative Polymerases in Maintaining Genome Stability

- ALS-Associated Mutations Result in Compromised Alternative Splicing and Autoregulation

- Robust Demographic Inference from Genomic and SNP Data

- Preferential Binding to Elk-1 by SLE-Associated Risk Allele Upregulates Expression

- Rad52 Sumoylation Prevents the Toxicity of Unproductive Rad51 Filaments Independently of the Anti-Recombinase Srs2

- The Serum Resistome of a Globally Disseminated Multidrug Resistant Uropathogenic Clone

- Identification of 526 Conserved Metazoan Genetic Innovations Exposes a New Role for Cofactor E-like in Neuronal Microtubule Homeostasis

- SUMO Localizes to the Central Element of Synaptonemal Complex and Is Required for the Full Synapsis of Meiotic Chromosomes in Budding Yeast

- Integrated Enrichment Analysis of Variants and Pathways in Genome-Wide Association Studies Indicates Central Role for IL-2 Signaling Genes in Type 1 Diabetes, and Cytokine Signaling Genes in Crohn's Disease

- Genome-Wide High-Resolution Mapping of UV-Induced Mitotic Recombination Events in

- Genome-Wide Analysis of Cell Type-Specific Gene Transcription during Spore Formation in

- Playing the Field: Sox10 Recruits Different Partners to Drive Central and Peripheral Myelination

- Two Portable Recombination Enhancers Direct Donor Choice in Fission Yeast Heterochromatin

- Mining the Human Phenome Using Allelic Scores That Index Biological Intermediates

- Yeast Tdh3 (Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase) Is a Sir2-Interacting Factor That Regulates Transcriptional Silencing and rDNA Recombination

- A Minimal Nitrogen Fixation Gene Cluster from sp. WLY78 Enables Expression of Active Nitrogenase in

- A Review of Bacteria-Animal Lateral Gene Transfer May Inform Our Understanding of Diseases like Cancer

- High Throughput Sequencing Reveals Alterations in the Recombination Signatures with Diminishing Spo11 Activity

- Partitioning the Heritability of Tourette Syndrome and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Reveals Differences in Genetic Architecture

- Eleven Candidate Susceptibility Genes for Common Familial Colorectal Cancer

- A GDF5 Point Mutation Strikes Twice - Causing BDA1 and SYNS2

- Systematic Unraveling of the Unsolved Pathway of Nicotine Degradation in

- Natural Genetic Variation of Integrin Alpha L () Modulates Ischemic Brain Injury in Stroke

- Evolutionary Tuning of Protein Expression Levels of a Positively Autoregulated Two-Component System

- Evolutionary Change within a Bipotential Switch Shaped the Sperm/Oocyte Decision in Hermaphroditic Nematodes

- Limiting of the Innate Immune Response by SF3A-Dependent Control of MyD88 Alternative mRNA Splicing

- Multiple Signaling Pathways Coordinate to Induce a Threshold Response in a Chordate Embryo

- Distinct Regulatory Mechanisms Act to Establish and Maintain Pax3 Expression in the Developing Neural Tube

- Genome Wide Analysis of Narcolepsy in China Implicates Novel Immune Loci and Reveals Changes in Association Prior to Versus After the 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic

- Mismatch Repair Genes and Modify CAG Instability in Huntington's Disease Mice: Genome-Wide and Candidate Approaches

- The Histone H3 K27 Methyltransferase KMT6 Regulates Development and Expression of Secondary Metabolite Gene Clusters

- Hsp70-Hsp40 Chaperone Complex Functions in Controlling Polarized Growth by Repressing Hsf1-Driven Heat Stress-Associated Transcription

- Function and Evolution of DNA Methylation in

- Stimulation of mTORC1 with L-leucine Rescues Defects Associated with Roberts Syndrome

- Transcription Termination and Chimeric RNA Formation Controlled by FPA

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Dominant Mutations in Identify the Mlh1-Pms1 Endonuclease Active Site and an Exonuclease 1-Independent Mismatch Repair Pathway

- Eleven Candidate Susceptibility Genes for Common Familial Colorectal Cancer

- The Histone H3 K27 Methyltransferase KMT6 Regulates Development and Expression of Secondary Metabolite Gene Clusters

- A Mutation in the Gene in Labrador Retrievers with Hereditary Nasal Parakeratosis (HNPK) Provides Insights into the Epigenetics of Keratinocyte Differentiation

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy