-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

An Essential Function for the ATR-Activation-Domain (AAD) of TopBP1 in Mouse Development and Cellular Senescence

ATR activation is dependent on temporal and spatial interactions with partner proteins. In the budding yeast model, three proteins – Dpb11TopBP1, Ddc1Rad9 and Dna2 - all interact with and activate Mec1ATR. Each contains an ATR activation domain (ADD) that interacts directly with the Mec1ATR:Ddc2ATRIP complex. Any of the Dpb11TopBP1, Ddc1Rad9 or Dna2 ADDs is sufficient to activate Mec1ATR in vitro. All three can also independently activate Mec1ATR in vivo: the checkpoint is lost only when all three AADs are absent. In metazoans, only TopBP1 has been identified as a direct ATR activator. Depletion-replacement approaches suggest the TopBP1-AAD is both sufficient and necessary for ATR activation. The physiological function of the TopBP1 AAD is, however, unknown. We created a knock-in point mutation (W1147R) that ablates mouse TopBP1-AAD function. TopBP1-W1147R is early embryonic lethal. To analyse TopBP1-W1147R cellular function in vivo, we silenced the wild type TopBP1 allele in heterozygous MEFs. AAD inactivation impaired cell proliferation, promoted premature senescence and compromised Chk1 signalling following UV irradiation. We also show enforced TopBP1 dimerization promotes ATR-dependent Chk1 phosphorylation. Our data suggest that, unlike the yeast models, the TopBP1-AAD is the major activator of ATR, sustaining cell proliferation and embryonic development.

Published in the journal: An Essential Function for the ATR-Activation-Domain (AAD) of TopBP1 in Mouse Development and Cellular Senescence. PLoS Genet 9(8): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003702

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003702Summary

ATR activation is dependent on temporal and spatial interactions with partner proteins. In the budding yeast model, three proteins – Dpb11TopBP1, Ddc1Rad9 and Dna2 - all interact with and activate Mec1ATR. Each contains an ATR activation domain (ADD) that interacts directly with the Mec1ATR:Ddc2ATRIP complex. Any of the Dpb11TopBP1, Ddc1Rad9 or Dna2 ADDs is sufficient to activate Mec1ATR in vitro. All three can also independently activate Mec1ATR in vivo: the checkpoint is lost only when all three AADs are absent. In metazoans, only TopBP1 has been identified as a direct ATR activator. Depletion-replacement approaches suggest the TopBP1-AAD is both sufficient and necessary for ATR activation. The physiological function of the TopBP1 AAD is, however, unknown. We created a knock-in point mutation (W1147R) that ablates mouse TopBP1-AAD function. TopBP1-W1147R is early embryonic lethal. To analyse TopBP1-W1147R cellular function in vivo, we silenced the wild type TopBP1 allele in heterozygous MEFs. AAD inactivation impaired cell proliferation, promoted premature senescence and compromised Chk1 signalling following UV irradiation. We also show enforced TopBP1 dimerization promotes ATR-dependent Chk1 phosphorylation. Our data suggest that, unlike the yeast models, the TopBP1-AAD is the major activator of ATR, sustaining cell proliferation and embryonic development.

Introduction

In response to endogenous and exogenous stress, cells have evolved a range DNA damage response (DDR) pathways to maintain genomic stability [1], [2], [3], [4]. In all eukaryotes, two evolutionarily conserved PI3-kinase-like protein kinases, ATM (Ataxia telangiectasia mutated) and ATR (ATM - and Rad3-related) respond directly to DNA damage to control cell-cycle progression and regulate other DNA damage responses such as DNA repair and apoptosis. ATM activation is triggered by double-strand breaks (DSBs), whereas ATR activation is induced by single stranded DNA (ssDNA) occurring due to replication stress, resected-DSBs or other single strand lesions [5], [6], [7], [8].

In all eukaryotic organisms, ATR is found associated with ATRIP (ATR-interacting protein) which is necessary to recruit ATR to RPA-coated ssDNA [9], [10], [11], [12]. In metazoans, but not in yeasts, this correlates with ATR autophosphorylation at T1989 [13], [14]. Pre-requisite for ATR activation is the independent recruitment of the Rad17-RFC checkpoint clamp loader to the junction of RPA-coated ssDNA and double stranded DNA (dsDNA), where it facilitates the loading of the Rad9-Hus1-Rad1 (9-1-1) sliding clamp [15]. The co-recruitment of ATR and the 9-1-1 clamp establishes a platform for activation of the ATR pathway [13], [16], [17]. The C-terminus of the Rad9 subunit of the 9-1-1 clamp is responsible for recruiting TopBP1 [18], [19], [20], a conserved multi-BRCT-domain scaffolding protein [21]. In yeast model systems, the Rad9 C-terminus must be phosphorylated by ATR to provide a docking site for phospho-protein binding domains within TopBP1 [18], [20]. In metazoans, Rad9 is constitutively phosphorylated by CK2 and thus TopBP1 recruitment does not require ATR-dependent Rad9 phosphorylation.

Metazoan TopBP1 contains nine BRCA1 C-terminal (BRCT) domains while the yeast homologs contain only four BRCT domains. The TopBP1 BRCT domains define phospho-binding motifs [22], [23] that allow TopBP1 to scaffold distinct proteins and protein complexes in response to the phosphorylation status of its clients. In all eukaryotes, TopBP1 plays an essential role in the initiation of DNA replication [21]. In yeast models, this function reacts to cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of two client proteins, Sld2 and Sld3, allowing TopBP1 to bridge an interaction between two replication factors in order to promote Cdc45 and GINS loading to activate the replicative helicase [24]. A similar role is evident in metazoans, where TopBP1 association with the Sld2 homolog, Treslin, is essential for replication initiation [25], [26], [27].

In response to ssDNA during DNA replication stress or DNA repair, yeast TopBP1 performs an equivalent scaffolding role, bridging between the 9-1-1 checkpoint clamp and the checkpoint mediator proteins (the 53BP1 homologs) which present checkpoint effector kinases (Chk's) to ATR [28], [29], [30]. This scaffolding role is essential for a functional ATR-Chk response. In addition, yeast TopBP1 contains a conserved ATR activation domain (AAD) which, when over-expressed, can directly induce ATR activation in the absence of DNA damage 11,31,32. The yeast TopBP1 AAD participates in, but is not necessary for, ATR activation: AAD-deficient separation of function mutants display only sensitivity to genotoxins and partial, cell cycle-specific checkpoint defects [32], [33]. As observed in the yeast models, metazoan TopBP1 is similarly required for activation of the ATR-Chk1 axis and is recruited to the site of DNA damage by binding to the C-terminus of the 9-1-1 complex [16], [31], [34]. However, at this point, significant differences emerge between the yeast and metazoan systems: in addition to the constitutive formation of a 9-1-1 TopBP1 interaction in metazoans (see above), replacing Xenopus TopBP1 with a recombinant protein containing a mutation in the AAD (W1138) completely blocks ATR activation in response to replication inhibition in extracts [31]. While extracts may not fully recapitulate all aspects of the cellular environment, this suggests a more important role for the metazoan TopBP1 AAD in ATR activation when compared to yeast.

The differences between ATR activation in the yeast and the metazoan systems are intriguing. In the yeast models, ATR provides the bulk of the checkpoint signalling following all forms of DNA damage, including DSBs. In metazoans, ATM provides the majority of checkpoint signalling in response to DSBs, with ATR playing a minor role. This distinction between yeasts and metazoans can be explained, at least in part, by different repair priorities: yeasts generally rapidly resect DSBs for repair by homologous recombination, with non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) - which occurs without significant resection - playing a minor role. Conversely, metazoan cells rely largely on NHEJ and thus detect DSBs through the ATM pathway. Experimentally limiting resection in yeast models uncovers an ATM-dependent checkpoint [35], [36], demonstrating the underlying machinery is conserved. The distinct repair priorities between yeast and metazoan systems are likely to underpin changes in the architecture of ATR activation mechanisms during evolution. For example, it is notable that distinct pairs of BRCT-domains mediate the 9-1-1 interaction in yeasts and metazoans: 9-1-1 interacts with BRCT 3+4, in yeasts (homologous to metazoan BRCT 4+5) but with the conserved BRCT1+2 pair in metazoans [21]. Furthermore, BRCT domains 7/8 in metazoans (which is not conserved in yeasts) binds autophosphorylated ATR-T1989 to promote a tight complex and strengthen ATR signalling [13], [14].

Complete deletion of TopBP1 in untransformed mouse or human primary cells induces cellular apoptosis and TopBP1 deficiency results in an early embryonic lethality [37], [38], [39], [40], [41]. Tissue specific deletion of TopBP1 in the central nervous system (CNS) similarly leads to an accumulation of DNA breaks in neuronal progenitors and subsequent disruption of neurogenesis [42]. These data are consistent with the essential role for TopBP1 in the initiation of DNA replication. To specifically establish the physiological function of the TopBP1 AAD, and to investigate if it is dispensable for ATR activation in metazoans as it is in yeasts, we generated a mouse model with a specific knock-in AAD mutation. We show that the TopBP1 AAD is essential for the embryonic development, phenocopies the lethal phenotype of ATR and is necessary for ATR signalling after UV damage. These data strongly suggest that, unlike in the yeast models, ATR activation of by the TopBP1 AAD is the major, if not only, route to activating the ATR-Chk1 axis and is essential for cell proliferation and survival.

Results

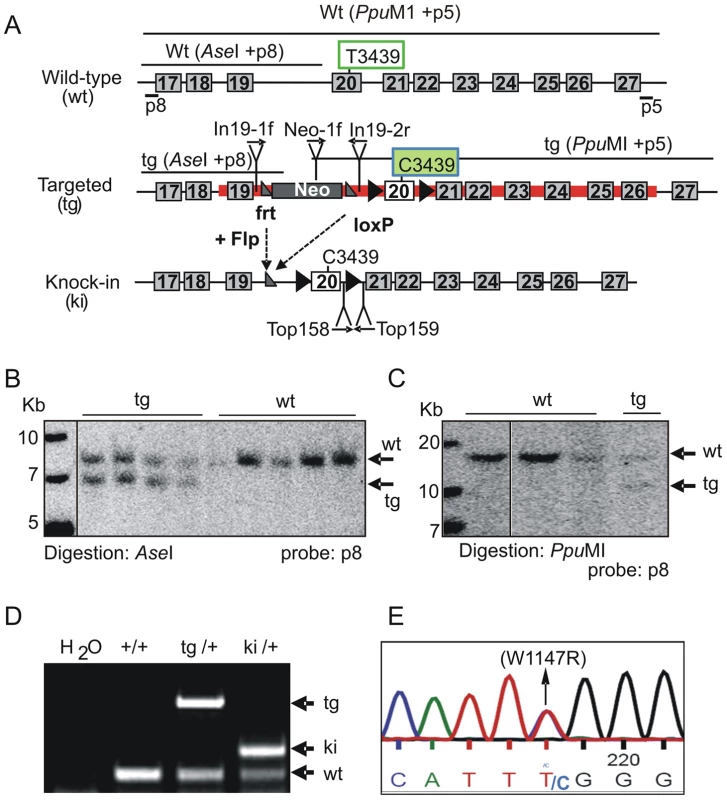

To explore the function of the TopBP1 AAD, we generated a specific knock-in allele of TopBP1 by gene targeting in mouse ES cells. The AAD domain spans exons 19 and 20 (Fig. S1), with the core indispensable aromatic residue, W1147 [31] encoded within exon 20. To change W1147 to arginine (W1147R), T3439 was mutated to C3439 in a targeting vector (Fig. 1A). A neomycin resistance cassette (Neo) flanked by Frt sequences, was also inserted into intron 19. Following electroporation into ES cells, 9/200 neomycin-resistant clones contained the targeted allele (Fig. 1B,C). A correctly targeted ES clone was used to derive germline chimeric mice (designated as TopBP1tg/+). Crossing TopBP1tg/+ mice with Flp transgenic mice (Jackson laboratory strain 003946) led to generation of the desired TopBP1 AAD knock-in allele, designated TopBP1ki/+ (Fig. 1A,D). The point mutation was confirmed by sequencing mouse genomic TopBP1ki/+ DNA (Fig. 1E) and verified in cDNA from TopBP1ki/+ MEFs (Fig. S2A). As expected, TopBP1 protein levels were similar between TopBP1+/+ and TopBP1ki/+ MEFs (Fig. S2B). We also confirmed that the AAD mutation did not compromise the protein expression of TopBP1 when transfected into Cos7 cells (Fig. S2C).

Fig. 1. Generation of TopBP1 AAD mutant transgenic mice.

(A) Schematic of the C-terminus of the TopBP1 locus: wild type (wt), targeted (tg) and knock-in (ki) alleles. The red line marks the targeting vector. Exons are numbered in the boxes, Southern blot probes (p8 and p5), sizes of DNA fragments after indicated enzyme digestion and the location of primers for PCR genotyping are shown. The targeting vector contained a neomycin resistance gene (Neo) flanked by two frt sites (grey triangles). Exon 20 is flanked by two loxP sites (black triangle). Tryptophan 1147 (W1147) was mutated into arginine in AAD by replacing T3439 with C in exon 20. (B–C) Southern blot analyses of gene targeted ES cell clones: Homologous integration was verified by digestion with AseI and hybridization with a 5′ external probe (p8) and by PpuMI digestion and hybridization with a 3′ external probe (p5). (D) PCR genotyping analysis of the wild type, targeted and the knock-in allele following Neo excission. (E). Sequencing of genomic DNA from TopBP1ki/+ heterozygous MEFs confirms the mutation of TTT (tryptophan) to TTC (Arginine) (W1147R). Inactivation of TopBP1 AAD results in early embryonic lethality

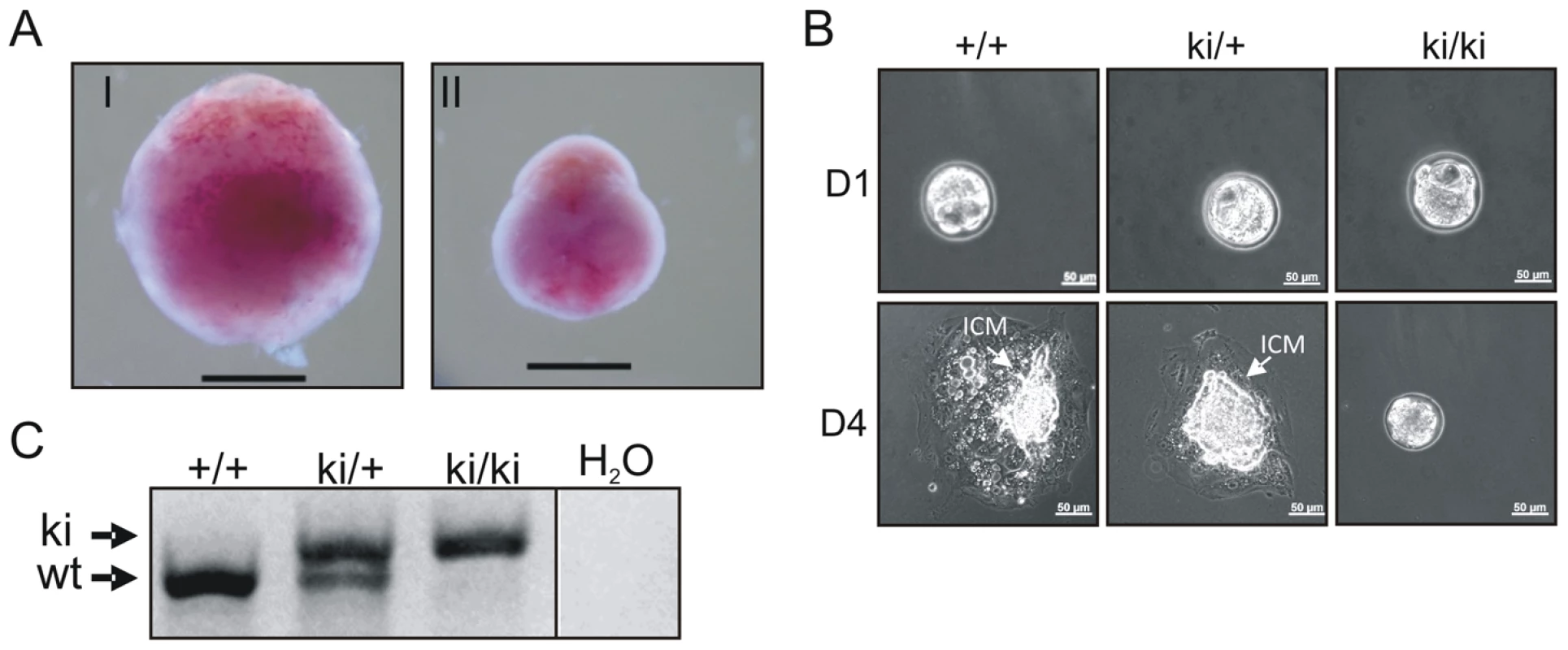

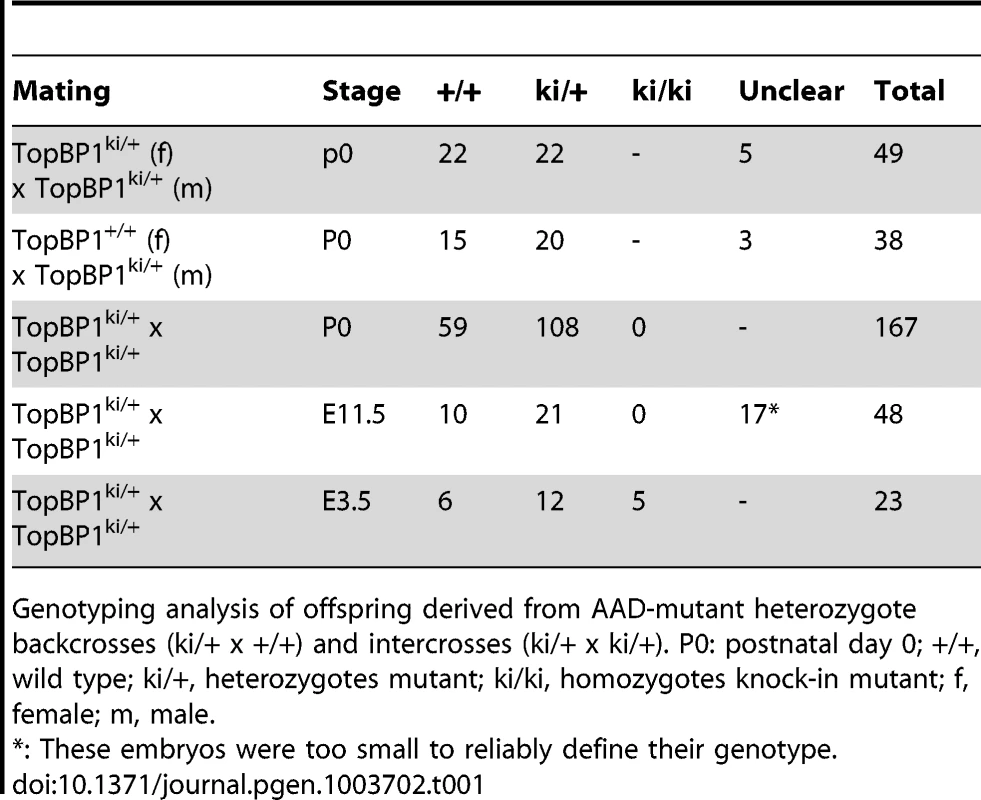

Heterozygous TopBP1ki/+ mice are viable and phenotypically normal during a 2 year-observation period (data not shown). However, no homozygous TopBP1ki/ki offspring were obtained from TopBP1ki/+ intercrosses (167 live births genotyped, Table 1). Backcrossing TopBP1ki/+ with TopBP1+/+ gave the expected ratio of TopBP1ki/+ and TopBP1+/+ offspring, indicating that there were no fertility defects in either the male or female TopBP1ki/+ animals (Table 1). We thus analyzed deciduas and embryos derived from TopBP1ki/+ intercrosses: genotyping at E11.5 revealed no homozygous mutants (Table 1), although 17/48 deciduas were small, precluding reliable PCR due to the presence of mother-derived tissues (Fig. 2A). We next isolated blastocysts (E3.5) from TopBP1ki/+ intercrosses for PCR genotyping: 21.7%, close to the expected Mendelian ratio, of embryos were TopBP1ki/ki homozygotes (Table 1). Although morphology was normal at isolation, all TopBP1ki/ki blastocysts failed to outgrow in vitro cultures (Fig. 2B, C). These data indicate that the TopBP1 AAD function is required for embryo development beyond the blastocyst stage.

Fig. 2. Inactivation of the AAD results in early embryonic developmental defects.

(A) Decidua at E11.5 from intercrossing of TopBP1ki/+mice. Decidua in (I) was genotype ki/+. Decidua in (II) was empty, thus with unclear genotype. Bar = 1 mm. (B) Cultures of E3.5 blastocysts from TopBP1ki/+ intercrosses. D1: 1 day after culture, D4: 4 days after culture. Arrows indicate inner cell mass (ICM). Bar = 50 micrometers. Genotypes are indicated on the top of respective images. (C) Example of PCR genotyping from ICM of blastocyst outgrowth. Expected product size for alleles labeled. ki = knock-in; wt = wild type. Tab. 1. Genotype distribution of offspring from TopBP1ki/+ breeding.

Genotyping analysis of offspring derived from AAD-mutant heterozygote backcrosses (ki/+ x +/+) and intercrosses (ki/+ x ki/+). P0: postnatal day 0; +/+, wild type; ki/+, heterozygotes mutant; ki/ki, homozygotes knock-in mutant; f, female; m, male. TopBP1 AAD is required for cell survival and proliferation

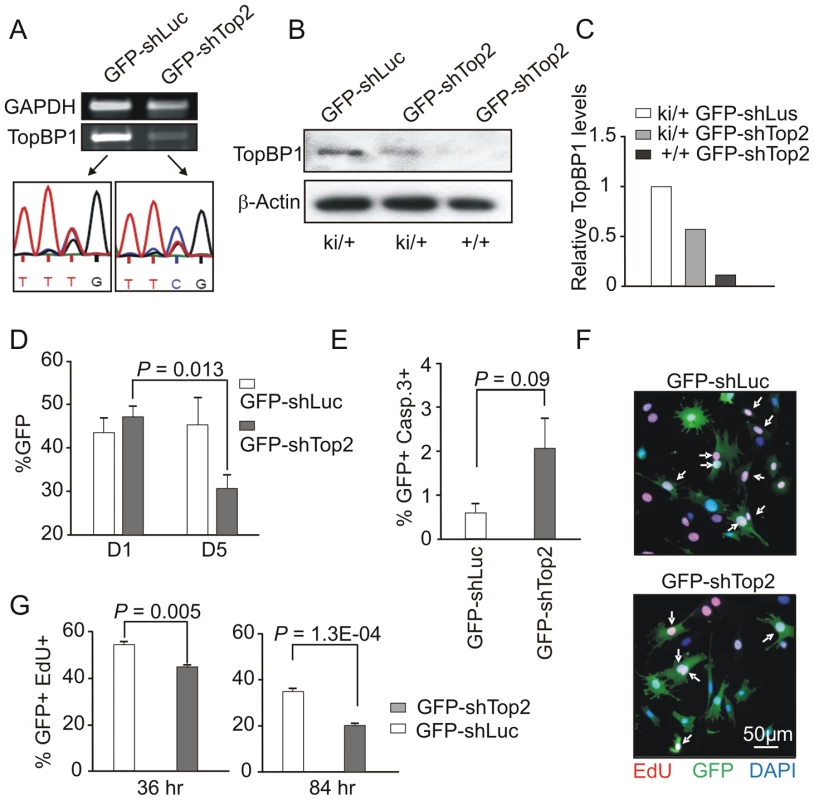

The lethal phenotype of TopBP1-W1147R precluded the use of TopBP1ki/ki MEFs for direct cellular assays. However, the presence of the base change associated with the knock-in mutation (T3439C) plus a second nucleotide polymorphism (Fig. S2A) derived from the targeting construct (T3477C, a silent mutation) offered the opportunity to specifically silence the TopBP1+ allele in TopBP1ki/+ MEFs. We designed two independent shRNA expression vectors targeted against the wild type sequence, but predicted to leave the knock-in allele resistant to RNA interference. Using co-transfection with corresponding chimeric GFP-encoding reporters, these were tested individually in COS7 cells for their ability to specifically target transcripts with the wild type (GFP-wtAAD), but not the knock-in (GFP-mutAAD) TopBP1 sequences (Fig. S3). The shRNA construct targeting the T3477C point mutation, designated shTop2, efficiently targeted GFP-wtAAD but not GFP-mutAAD. We thus transferred the shRNA construct into a vector expressing GFP to create GFP-shTop2. The co-expression of GFP from the shRNA vector will allow selection for transfected cells.

GFP-shTop2, or a GFP-shLuciferase (GFP-shLuc) control, was transfected into TopBP1ki/+ MEFs previously immortalized by a 3T3 protocol. GFP-positive cells were sorted by FACS 36 hours after transfection (Fig. S3D). Semi-quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) indicated that, in comparison to GFP-shLuc control transfected cells, TopBP1 mRNA levels were reduced upon GFP-shTop2 transfection. Sequencing revealed that the remaining TopBP1 mRNA was predominantly the AAD mutant form (Fig. 3A). Western blot analysis revealed a reduction of ∼50% for the TopBP1 protein following GFP-shTop2 transfection of TopBP1ki/+ cells when compared to GFP-shLuc control transfected cells (Fig. 3B,C). Corroboration of the specificity of GFP-shTop2 to the wild type TopBP1 transcript comes from the observation that GFP-shTop2 efficiently knocked down TopBP1 levels in TopBP1+/+ MEF cells (Fig. 3B,C). In the following experiments, we designated GFP-shTop2-transfected TopBP1ki/+ cells as GFP-TopBP1ki/− and GFP-shLuc transfected TopBP1ki/+ cells as GFP-TopBP1ki/+.

Fig. 3. AAD mutation compromises cell proliferation and promotes cellular senescence.

(A) RT-PCR and sequencing analysis of TopBP1 mRNA in sorted GFP-positive TopBP1ki/+ cells after transfection with indicated vectors. (B) Immunoblot analysis of protein extracts from GFP-positive TopBP1ki/+ or TopBP1+/+ cells 36 hr after transfection with GFP-shLuciferase (GFP-shLuc) or GFP-shTop2. (C) Quantification of TopBP1 in B. Average of two independent experiments. (D) Percentage of GFP+ cells in the TopBP1ki/+ cell population at day 1 (D1) and days 5 (D5) following shRNA transfection. Results represent 3 independent experiments for each time point. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. (E) Quantification of cleaved caspase 3-positive cells by immunostaining 84 hr after shRNA transfection. The data represent the mean ± SD of at least 1000 cells and two independent experiments. P value: Student's t-test. (F) Representative image of TopBP1ki/+ cells plus-labeled with EdU (red) 36 hr after transfection with GFP-shLuc or GFP-shTop2 vectors. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Arrows point to EdU and GFP double positive cells (EdU+GFP+) cells. (G) Quantification of the percentage of Edu+GFP+ in the total GFP+ population at 36 hr and 84 hr after shRNA transfection. The data represent the mean ± SD of at least 1000 cells for each group and three independent experiments. P value: Student's t-test. To identify the consequences of specific loss of TopBP1 AAD function in cell survival and proliferation we followed the proportion of the GFP positive cells after GFP-shTop2 or GFP-shLuc transfection. 24 hours after transfection, the GFP+ population was similar for GFP-TopBP1ki/− (GFP-shTop2 transfected) and control GFP-TopBP1ki/+ cells (GFP-shLuc transfected). However, 5 days after transfection the proportion of GFP-TopBP1ki/− cells was significantly reduced when compared to GFP-TopBP1ki/+ cells (Fig. 3D). Immunostaining against cleaved Caspase 3 revealed a mild (but not statistically significant) increase of apoptosis in GFP-TopBP1ki/− when compared to control GFP-TopBP1ki/+ cells 4 days after of transfection (Fig. 3E). This suggests that delayed proliferation as opposed to apoptosis is the major cause of the reduced number of GFP-TopBP1ki/− cells. To further characterise the effect of the AAD mutation on cell proliferation, cells were pulse-labeled with EdU for 2 hours either 36 or 84 hours following transfection. Consistent with reduced proliferation, the percentage of GFP+ cells that were also positive for EdU in GFP-TopBP1ki/− cultures was reduced when compared to GFP-TopBP1ki/+ controls (Fig. 3F, G). Nonetheless, a significant proportion of GFP-TopBP1ki/− cells were also EdU+, consistent with the AAD mutation being dispensable for DNA replication.

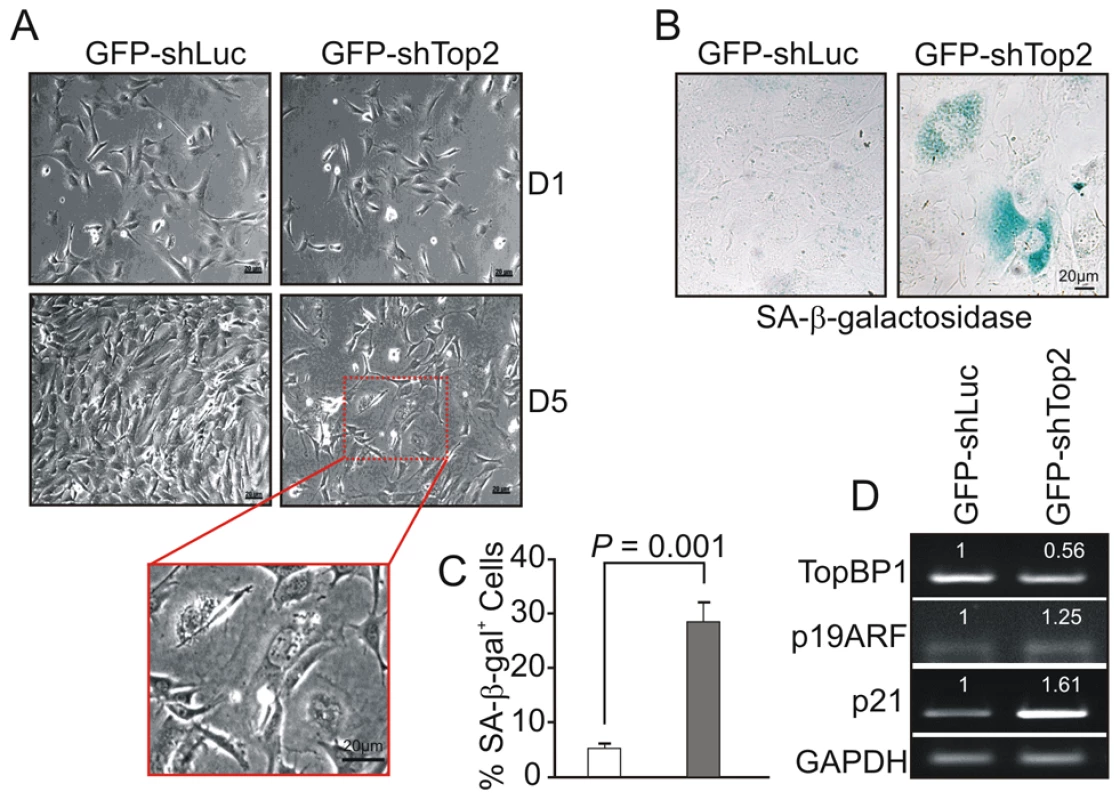

Following transfection with GFP-shLuc, control (GFP-TopBP1ki/+) cells became confluent after 5 days in culture. However, the density of GFP-TopBP1ki/− cells following transfection with GFP-shTop2 did not significantly increase over the same period (Fig. 4A). GFP-TopBP1ki/− cells became giant and flat after 4 days in culture (Fig. 4A) and this was often associated with β-galactosidase positive staining, indicative of cellular senescence (Fig. 4B,C). Consistent with this, RT-PCR analysis revealed up-regulated expression of p19ARF and p21, known senescence markers, in senescent GFP-TopBP1ki/− cells (Fig. 4D). We conclude that loss of TopBP1 AAD function results in proliferation defects and promotes entry into senescence.

Fig. 4. AAD mutation induces premature cellular senescence.

(A) GFP+ TopBP1ki/+ cells were sorted 24 hr after transfection and cultured. Images show the cell density and morphology at D1 and D5. Enlargement shows a representative area of TopBP1ki/− cells from D5. (B) SA-β-galactosidase staining of cells 6 days after shRNA transfection shown in blue. (C) Quantification of SA-β-galactosidase positive cells from B. The data represent the mean ± SD of at least 500 cells from 2 independent experiments. P value: Student's t-test. (D) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from D5 cultures from A. The expression level (indicated on top of each sample) was estimated by quantification normalized to the level of GAPDH and then correlated with GFP-shLuc transfected cells. Two independent experiments were performed which showed equivalent results. Activation of the ATR-Chk1 pathway in AAD-mutant cells

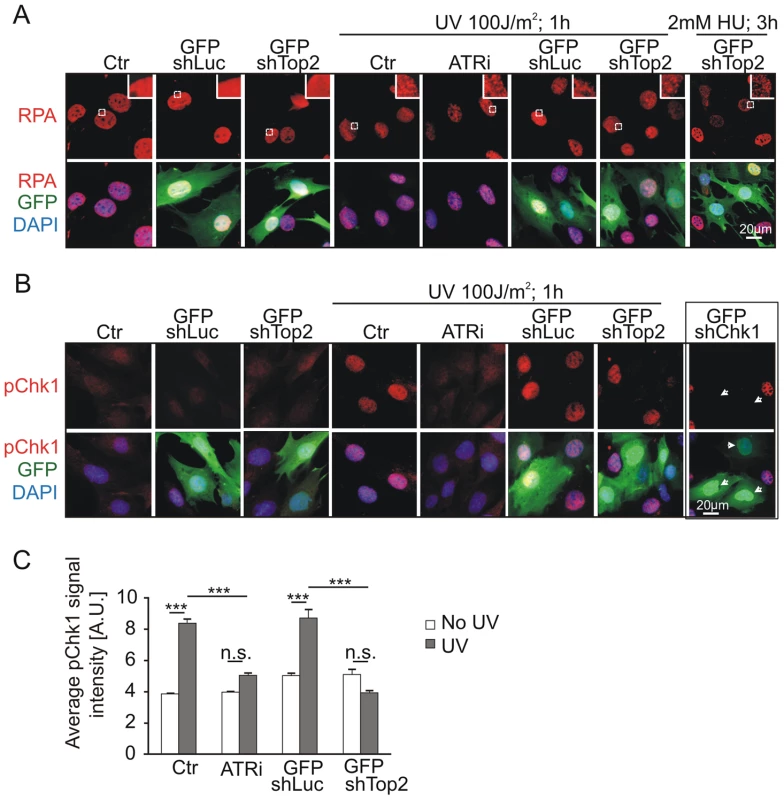

To test if the TopBP1 AAD mutation affected activation of the ATR pathway following DNA damage treatment we analyzed Chk1 phosphorylation following UV irradiation. First we established that, in our assay, UV irradiation resulted in RPA foci formation - an event occurring upstream from, and independent of, ATR activation. As expected, UV treatment resulted in similar patterns of RPA foci in GFP-TopBP1ki/−, GFP-TopBP1ki/+ and non-transfected control cells. Inhibition of ATR activity using the chemical inhibitor (ATRi; ETP-46464 [43]) similarly did not affect RPA localization after UV (Fig. 5A). Conversely, Immunostaining for phosphorylated Chk1 (p-Chk1-S317) to detect substrates downstream of ATR activation showed a dramatic increase of pChk1 in untransfected and GFP-TopBP1ki/+ (shLuc transfected) cells, whereas GFP-TopBP1ki/− (shTop2 transfected) and ATRi-treated TopBP1ki/+ cells showed attenuated p-Chk1-S317 staining to similar levels (Fig. 5B,C). Verifying the specificity of the assay, UV-induced p-Chk1-S317 staining was fully abrogated in TopBP1ki/+ cells following GFP-shChk1 transfection (Fig. 5B) [44]. These data are consistent with an expectation that TopBP1 AAD function is necessary to activate ATR in response to UV treatment.

Fig. 5. Mutation of AAD impairs ATR-Chk1 pathway in vivo.

(A) Immunostaining of RPA (red and upper panel) in TopBP1ki/+ cells 36 hr after transfection with GFP-shLuc or GFP-shTop2 without or with the indicated treatment. ATRi, ATR inhibitor. GFP-shLuc or GFP-shTop2 transfection is visualized by GFP (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Inset shows the enlargement of selected areas. (B) Immunostaining of phosphorylation of Chk1-S317 (pChk1, red, upper panel) in TopBP1ki/+ cells 36 hr after transfection with GFP-shLuc or GFP-shTop2 without or with the indicated treatment. ATRi, ATR inhibitor. GFP-shLuc or GFP-shTop2 transfection is visualized by GFP (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). GFP-shChk1 transfection (right panel, arrows) served as a negative control for pChk1 staining. (C) Quantification of fluorescent density of phosphor Chk1-S317 staining (pChk1) of indicated samples from B. The data represent the mean ± SD of at least 200 cells (or GFP positive cells) and were repeated three times. One-way ANOVA pair-test was performed for the statistical analysis. ***P<0.001; n.s., not significant. ATR activation induced by dimerization of TopBP1 is AAD dependent

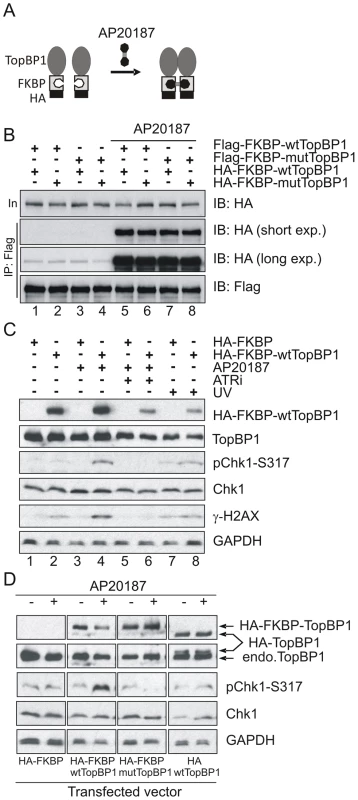

It has previously been established that phosphorylation of human TopBP1 within the AAD at S1159 (analogous to mouse S1161) by Akt/PKB facilitates TopBP1 oligomerisation [45], [46]. To establish if our AAD mutation compromises ATR activation by preventing TopBP1 oligomerisation, we adopted an experimental approach that exploits inducible dimerization: TopBP1 was fused to FKBP-F36V (Fig. 6A), a mutant form of FKBP12 that forms a dimer upon binding to the synthetic ligand AP20187 [47]. Flag - and HA-tagged wild type TopBP1 (wtTopBP1) or TopBP1-W1147R (mutTopBP1), each fused with FKBP, were co-expressed in all combinations. Cells were then treated with AP20187 and extracts assayed for expression and co-precipitation of HA-tagged protein by the Flag-tagged protein. As expected, interactions mediated by AP2187 ligand were observed for all combinations (Fig. 6B) consistent with the expectation that a point mutation in the AAD does not disrupt FKBP-induced dimer formation.

Fig. 6. Inducible dimerization of TopBP1 activates ATR-Chk1.

(A) Schematic showing the inducible dimerization. Addition of AP20187 induces dimerization (interaction) of FKBP-containing proteins. (B) Immunoprecipitation (IP) coupled immunoblot (IB) analysis of HEK293T cells that were transfected with the indicated vectors (Flag-tagged and HA-tagged). Cells were treated with 100 nm of AP20187 for 1 hr and analyzed by IP-IB using indicated antibodies. (C) IP-IB analysis of HEK293T cells after transfection with empty vector (HA-FKBP) or wild type TopBP1 (HA-FKBP-wtTopBP1). Cells at 40 hr after transfection were incubated with 100 nm of AP20187 for 1 hr without or with 1.6 mM of ATR inhibitor (ATRi) or were treated with 100 J/m-2 UV. Immunoblot analysis was performed 1 hr after respective treatment. (D) IP-IB analysis of HEK293T cells after transfection with empty vector (HA-FKBP), or FKBP-fused wild type TopBP1 (HA-FKBP-wtTopBP1), or FKBP-fused AAD mutant TopBP1 (HA-FKBP-mtTopBP1), or wild type TopBP1 without FKBP (HA-wtTopBP1). Cells were treated with 100 nm of AP20187 for 1 hour then analysed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. Interestingly, when we transfected HA-FKBP-wtTopBP1 into cells we observed that the dimerization of TopBP1 induced by AP20187 promoted ATR-dependent Chk1 phosphorylation (ATRi treatment abolished phosphorylation; see lane 6). Unexpectedly, this was independent of DNA damage treatment (Fig. 6C: compare lanes 2 with 4). We next exploited this dimerisation-induced Chk1 phosphorylation to establish if the requirement for the TopBP1 AAD in ATR activation could be bypassed by forced dimerisation. HA-FKBP-wtTopBP1, HA-FKBP-mutTopBP1 and the controls HA-FKBP and HA-wtTopBP1 were each transfected into cells and AP20187 ligand-dependent Chk1 phosphorylation monitored. Neither FKBP alone or TopBP1 alone resulted in Chk1 phosphorylation in response to AP210187 ligand. As expected, HA-FKBP-wtTopBP1 expression resulted in Chk1 phosphorylation upon ligand addition (Fig. 6D). Conversely, HA-FKBP-mutTopBP1experssion did not induce Chk1 phosphorylation in response to ligand. Suggestive of a dominant negative effect, Chk1 phosphorylation in these cells was impaired below background upon AP20187-induced interaction (Fig. 6B, D). These results indicate that induced oligomerisation of TopBP1 is sufficient to induce ATR activation and subsequent Chk1 phosphorylation and that this requires the TopBP1 AAD function.

Discussion

In both metazoans and in the yeast models, TopBP1 is required both for the initiation of DNA replication and for signalling through the ATR pathway [21]. Using the yeast models, the main function of TopBP1 in replication has been elucidated: TopBP1 acts as a scaffold, read the phosphorylation status of client proteins to promote the formation of the replicative helicase [24], [25], [26], [27]. A similar phosphorylation-dependent bridging function for TopBP1 was identified during the transmission of the ATR checkpoint [20]. An additional function for TopBP1, which was first identified in metazoans [31] and later shown to be conserved in the yeasts [11], [32], [33], is its ability to directly activate ATR through an interaction between the TopBP1 AAD domain and the ATR-ATRIP complex.

Depleting wild type TopBP1 from Xenopus and replacing this with recombinant protein in which a single aromatic residue is disrupted within the AAD abolished ATR activation in response to replication inhibitors. This suggested a key role for the AAD in activating the ATR checkpoint. However, in both the S. cerevisiae and the S. pombe model organisms, while the AAD domain of the TopBP1 homologs was similarly sufficient to activate ATR, either in vitro or in vivo, it plays a relatively minor role in ATR checkpoint signalling in response to DNA damage or replication stress. Recent data from S. cerevisiae identified two further ATR activating domains which play partially redundant roles in checkpoint activation: one is contained within the C-terminus of Ddc1Rad9, a 9-1-1 clamp subunit [48], while the other is found in the Dna2 replication protein [49]. Interestingly, compromising the function of all three AAD domains (Dpb11TopBP1, Ddc1Rad9 and Dna2) in the same cells largely abolished activation of the ATR pathway in S. cerevisiae. These data show that, in the yeasts, multiple ATR activation domains promote ATR activation above basal levels and that checkpoint function is dependent on ATR activation by one or more AAD domains [50].

The TopBP1 AAD is required for embryo development

In the present study, we investigated the biological significance of the TopBP1 AAD in a mouse model. We created a single point mutation (W1147R) within the AAD of TopBP1 that removes a key aromatic residue necessary for the activation of ATR. This is predicted to separate the AAD function from other essential functions such as the scaffolding role during replication initiation and from any roles in scaffolding checkpoint complexes. Unexpectedly, this point mutation resulted in early embryonic lethality and developmental arrest at the blastocyst stage. This early lethal phenotype is equivalent to that reported for the complete knockout of TopBP1 in mice [51] and is reminiscent of the consequence of ATR deletion [52], [53]. Due to the early lethality we could not directly eliminate the possibility that the homozygous AAD knock-in (TopBP1ki/ki) mutation had, in fact, generated a null mutation. However, both the mRNA and TopBP1 protein levels were produced at the expected levels by the AAD knock-in allele which was visualized by specific shRNA knock-down of the wild type TopBP1 mRNA in heterozygous MEFs (TopBP1ki/+) (see Fig. 3B and Fig. S3B). Based on these data we propose that the TopBP1-W1147R (AAD mutant) protein is stable and the phenotypes observed are a direct consequence of the mutation introduced. Our results thus suggest that one essential function for TopBP1 in embryonic development is realized by a TopBP1 AAD-mediated ATR activation function and that this cannot be substituted for by other potential AAD domains. In addition, the scaffolding functions of TopBP1 in replication initiation and checkpoint activation cannot sustain embryonic development and are insufficient for ATR activation.

The TopBP1 AAD plays a key role in cellular checkpoint signalling

By establishing an shRNA knock-down assay which specifically targeted the wild type, but not the TopBP1-W1147R (AAD mutant) mRNA, we were able to examine the effect of the AAD mutation in MEFs. Our first observation is that MEFs containing only mutated TopBP1-W1147R (GFP-TopBP1ki/−) were not able to proliferate and entered senescence. This is consistent with the early embryonic lethality and strongly suggests an essential cellular role for the TopBP1 AAD, presumably by activating ATR. Our preferred explanation is that specific lesions are generated in mammalian cells during DNA replication and that, in response to these, only the TopBP1 AAD is capable of activating ATR. Such an explanation does not preclude the existence of additional ATR activating domains in other proteins (as is observed in the yeasts) but would suggest that, if these exist, they respond to alternative DNA structures or to structures formed at different points in the cell cycle, for example only in G1.

Induced DNA damage, such as that caused by UV irradiation, arrests cell proliferation via cell cycle checkpoint activation. We examined the response of cells to UV irradiation and observed that, in the absence of the wild type protein (via shRNA knock-down), cells expressing the TopBP1-W1147R (AAD mutant) protein were unable to mount a significant ATR response. The parsimonious explanation for this is that, in mammalian cells, the TopBP1 AAD is either the main or the sole mechanism for activating ATR. Given the additional complexity evident in the yeasts, this is surprising to us: evolution is prone to elaborate mechanistic pathways as organisms become multicellular and more complex. Nonetheless, our data suggest that the TopBP1 AAD is responsible for the majority of ATR signaling and that additional ATR activating domains play little or no role in metazoan checkpoint responses.

The inhibition of TopBP1 expression by antisense oligomers or by siRNA induces apoptosis in cancer cell lines or MEF cells [37], [38], [39], [40], [41]. In contrast, we did not observe a statistically significant increase in apoptosis when cells grew in the presence of the TopBP1 AAD defective protein (GFP-TopBP1ki/−). Instead, we observed increased cellular senescence that was associated with elevated expression of p19 and p21. Full loss of TopBP1 function would be expected to disrupt replication initiation, whereas the specific loss of the AAD function may allow replication but lead to an accumulation of spontaneous damage that subsequently signals through the ATM pathway. Consistent with this, we did observe some incorporation of EdU in GFP-TopBP1ki/− cells and we thus suggest that the reduced proliferation and increased cellular senescence observed in GFP-TopBP1ki/− cells stems from impaired G1/S transition likely resulting from ATM activation. MEF cells deleted for ATR similarly show an increase in cellular senescence, a reduction of proliferation and only a small increasing of in apoptosis [54]. This is also consistent with our expectation that the TopBP1 AAD mutation specifically affects the ATR-Chk1 cascade without preventing replication initiation.

Forced TopBP1 oligomerisation results in ATR activation

While establishing that the AAD mutation in TopBP1 was not preventing ATR activation due to a dimerization defect, we found that forced dimerization of TopBP1 strongly stimulated ATR activation in the absence of induced DNA damage, as judged by a significant increase in Chk1phosphorylation. While oligomerisation can lead to increased protein stability and improvements to enzymatic activity [55], we did no observe any increase of the TopBP1 protein level following induced oligomerisation. Several alternative possibilities could account for ATR activation by oligomerised TopBP1: oligomerisation may enhance the affinity of TopBP1 for its interaction partners. In this regard, it is interesting to note that phosphorylation of Ser1131 (ortholog of human TopBP1 Ser1140) in the AAD of Xenopus TopBP1 enhances binding of to the Xenopus ATR-ATRIP complex, and thereby increases the capacity of TopBP1 to activate the ATR [56]. Alternatively, oligomerisation of TopBP1 may enhances its chromatin binding ability. In this regard it is interesting to note that tethering TopBP1 [57] or the S. pombe homolog (Rad4TopBP1) to chromatin [32] activates the ATR and Chk1-dependent checkpoint. As expected, despite the forced oligomerisation of the AAD mutant of TopBP1, it failed to stimulates ATR activity, strongly suggesting that TopBP1 oligomerisation is necessary but not sufficient for ATR activation and that an intact AAD is required.

Materials and Methods

Vector construction for gene targeting, over-expression and shRNA knockdown

Gene targeting vector was constructed with Red/ET recombineering technology (Gene Bridges). Briefly, a LoxP-Neo-LoxP cassette was inserted into bacmid (bMQ-304N19, Geneservice) encompassing the genomic region of TopBP1, using the Red/ET Quick and Easy BAC Modification Kit. The Neo cassette was subsequently excised by expression Cre recombinase in host bacterial cells, resulting in a one LoxP site in intron 20. Next, a second Flp-Neo-Flp cassette was inserted into intron 19. Mutation of Tryptophan to Arginine at 1147 was achieved by in vivo substitution of T3439 by C3439 (Counter-Selection BAC Modification Kit, Gene Bridges). The engineered genomic region of TopBP1 in bacmid was then subcloned into high-copy plasmid vector (ColE1) by homologous recombination, resulted in the targeting construct of TopBP1-W1147R.

Flag-tagged full length wild type or W1147R mutant TopBP1 were amplified by PCR with 5′-primer TopFL-5 (TACGGATCCCTCGGGCTCCACCTAGTTCA) and 3′ - primer TopFL-3 (CCGCTCGAGGCCGTTTGACTACATTC) and constructed into pCMV-tag 2C (Stratagene), pcDNAHA, or pcDNAHA2FKBP vector, respectively [47]. GFP-tagged wild type or W1147R mutant AAD of TopBP1 were amplified by PCR with 5′-primer micTop54-2 (GAAGATCTTGACCCAGGCCTTGGAGATGAGAG) and 3′-primer micTop34-2 (ACGCGTCGACTGCCCTGGGGCTTGAGTAACACA) and constructed into pEGFP C2 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). The construction of shRNA expression vectors was performed as previously described [58]. Briefly, oligonucleotides targeting the coding sequences and their complementary sequences were inserted into the vector under the control of the human U6 promoter with or without CMV-driven EGFP. All the oligonucleotides contained the following hairpin loop sequence: TTCAAGAGA. The targeting sequences used were: Luciferase: GGCTTGCCAGCAACTTACA, shTop1: TGAGCAGATCATTTGGGACG, and shTop2: TGGCTTGCCAGCAACTTACA. All the constructions were confirmed by sequencing. shRNA expression vector to target Chk1 was reported as previously [44].

Gene targeting of TopBP1 AAD mutant allele, genotyping of ES cells and mice by Southern blot, PCR and sequencing

The gene targeting vector was linearized by Cla I digestion and electroporated into the E14.1 ES cells. After selection with G418, correctly targeted TopBP1W1147R knock-in (ki) ES clones were identified by Southern blot analysis and used to generate germline chimeric mice. To analyze the 5′-arm integration of the targeting vector into the TopBP1 locus, ES cell DNA was digested with AseI and probed with an intron-16 probe (p8) located externally to the upstream of targeting area. 3′-arm integration of the targeting vector was analyzed by digestion the DNA with PpuM 1 and hybridization with an intron-27 probe (p5) located externally to the downstream of targeting area (see Fig. 1A).

For the PCR genotyping, the following primers were used: Top158: CTTCTCACTGTGCTGCTTCCTATAGC; Top159: GCTATTAATTGAGTTTTGTGAATCCC; In19-1f: GCAAGCCATGCAAGTCAATA; In19-2r: GCTTCCCCTGCTGTGATA; neo-1f: ATCTCCTGTCATCTCACCTTGC. The primer pair Top158 and Top159 was used to detect the wild type allele (wt) and targeted allele (tg) or knock-in targeted allele (ki). Combination of In19-1f, neo-1f and In19-2r detects the remove of neo-cassette in targeted allele. For sequencing genotyping of the TopBP1W1147R ki allele, genomic DNAs were isolation and sequenced with primer In19-1f.

mRNA isolation and semi-quantitative PCR

The total RNA was isolated by using Tri Reagent (T9424, Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany). 1 µg of RNA was used for synthesis of first-strand cDNA by Affinity Script Multiple Temperature cDNA Synthesis Kit (200436, Stratagene) according to the manual. Semi-quantitative PCR was performed with the following primers. For TopBP1: micTop54-2 and micTop34-2 (see 4.1); for GAPDH: forward primer mGAPDH15 (GCACAGTCAAGGCCGAGAAT) and reverse primer mGAPDH13(GCCTTCTCCATGGTGGTGAA); For p19ARF: forward primer p19f (CCCACTCCAAGAGAGGGTTT) and reverse primer p19r (TCTGCACCGTAGTTGAGCAG); For p21: forward primer p21f(GTCAGGCTGGTCTGCCTCCG) and reverse primer p21r (CGGTCCCGTGGACAGTGAGCAG).

Primary MEF isolation and cell culture, transfection, sorting and stability analysis

Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from E13.5 embryos derived from the mating between TopBP1ki/+ mice and immortalized with a standard 3T3 protocol [59]. For transfection, 3T3 MEFs were transfected using Amaxa Nucleofector Kit R (VCA-1001, LONZA, Cologne, Germany). Briefly, MEFs were trypsinized and 1×106 cells were centrifuged at 200× g for 10 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in 100 µl Nucleofector Solution mixture plus 5 g of plasmid-DNA. The cell suspension was electroporated using Nucleofector I Device (Lonza). The electroporated MEFs were cultured under normal conditions for 24 hr before FACsorting based on GFP expression. The sorted cells were either used for protein extraction, mRNA isolation or further cultured in the presence of 400 ug/ml of G418 (Invitrogen). For EdU labeling, cells were incubated with 1 µg/ml of EdU (A10044, Invitrogen) for 2 hr at 36 or 84 hr after transfection. UV exposure and HU treatment were performed at 36 hr after transfection and cells were fixed with 4% PFA for immunofluorescence staining. For ATR inhibitor treatment, 1.6 µm ATR inhibitor (ATRi) was added 1 hr before exposure to 100 J/m2 of UV. Cos7 or HEK293T cells were transfected with lipofectamine2000 (11668-019, Invitrogen) according the manufacturer's instruction

Immunostaining, EdU reaction and β-galactosidase staining

Immunostaining was performed on as described previously [44]. Briefly, PFA-fixed cells were incubated with blocking buffer (1% BSA, 5% goat serum and 0.4% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 hr at room temperature then with a primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight followed by secondary antibodies for 2 hr at room temperature. After washing, the slides were mounted with DAPI-containing mounting medium (Invitrogen). The primary antibodies and respective dilutions are: rabbit anti-pChk1-S317 antibody (1∶100, A300-163A-3, Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA); rabbit anti-Cleaved Caspase-3 (Asp175) (1∶300, 9662, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers MA, USA) and rat anti-RPA antibody (1∶300, 2208, Cell Signaling Technology). EdU detection was carried out using a Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 647 Imaging Kit (953624, Invitrogen) after fixation according to the manufacturer's instruction. β-galactosidase staining was performed with a Senescence β-galactosidase staining kit (9860, Cell Signaling Technology) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Cells images were acquired using a virtual microscope (BX61VS, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or a confocal microscope (LSM510, Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The density of fluorescent signal was quantified by a high-content analysis microscopy (Cellomics Arrayscan VTI, Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Western blotting analysis

The proteins were extracted with RIPA buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 20% glycerol, 0.5M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 5 mg/ml leupeptin, 2 mg/ml aprotinin, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4 and 10 mM NaF) from cells. After separation in SDS-PAGE, the membranes were blotted with the flowing antibodies. The primary antibodies used in this study were rabbit anti-TopBP1 antibody (1∶1000, AB3245, Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany), rabbit anti-phospho-S317-Chk1 (1∶1000, A300-163A, Bethyl Laboratories), Rabbit anti-HA (1∶10000,A190-208A, Bethyl Laboratories); mouse anti-β-Action (1∶20000, C2206, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti-Flag (1∶10000, F4042, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti - γH2AX (1∶1000, 05-636, Millipore); sheep anti-Chk1 antibody (1∶1000, ab16130, Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

Chemically induced dimerization of TopBP1

The inducible dimerization assay was performed as previous described [47]. Briefly, HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with pcDNAHA2-TopBP1 or pcDNAHA2FKBP-TopBP1 (or its AAD mutant counterpart). Forty hours later, transfectants were either mock-treated with 0.1% ethanol or treated with a 100 nM of the bivalent ligand AP20187 (635060, Clontech) and/or combined with 1.6 µm ATR inhibitor (ATRi) for 1 hr. Immunoprecipitation was carried out as previous described [47].

Ethics statement

Animal experiments conducted in this report were approved and conducted according to the German or British animal welfare legislation and in pathogen-free conditions.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. AguileraA, Gomez-GonzalezB (2008) Genome instability: a mechanistic view of its causes and consequences. Nature reviews Genetics 9 : 204–217.

2. CicciaA, ElledgeSJ (2010) The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Molecular cell 40 : 179–204.

3. JacksonSP, BartekJ (2009) The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature 461 : 1071–1078.

4. BranzeiD, FoianiM (2010) Maintaining genome stability at the replication fork. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 11 : 208–219.

5. BitonS, DarI, MittelmanL, PeregY, BarzilaiA, et al. (2006) Nuclear ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) mediates the cellular response to DNA double strand breaks in human neuron-like cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 281 : 17482–17491.

6. CimprichKA, CortezD (2008) ATR: an essential regulator of genome integrity. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 9 : 616–627.

7. MavrouA, TsangarisGT, RomaE, KolialexiA (2008) The ATM gene and ataxia telangiectasia. Anticancer research 28 : 401–405.

8. YouZ, ShiLZ, ZhuQ, WuP, ZhangYW, et al. (2009) CtIP links DNA double-strand break sensing to resection. Molecular cell 36 : 954–969.

9. BallHL, MyersJS, CortezD (2005) ATRIP binding to replication protein A-single-stranded DNA promotes ATR-ATRIP localization but is dispensable for Chk1 phosphorylation. Molecular biology of the cell 16 : 2372–2381.

10. CortezD, GuntukuS, QinJ, ElledgeSJ (2001) ATR and ATRIP: partners in checkpoint signaling. Science 294 : 1713–1716.

11. MordesDA, NamEA, CortezD (2008) Dpb11 activates the Mec1-Ddc2 complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 : 18730–18734.

12. EdwardsRJ, BentleyNJ, CarrAM (1999) A Rad3-Rad26 complex responds to DNA damage independently of other checkpoint proteins. Nature cell biology 1 : 393–398.

13. LiuS, ShiotaniB, LahiriM, MarechalA, TseA, et al. (2011) ATR autophosphorylation as a molecular switch for checkpoint activation. Molecular cell 43 : 192–202.

14. NamEA, ZhaoR, GlickGG, BansbachCE, FriedmanDB, et al. (2011) Thr-1989 phosphorylation is a marker of active ataxia telangiectasia-mutated and Rad3-related (ATR) kinase. The Journal of biological chemistry 286 : 28707–28714.

15. ZouL, LiuD, ElledgeSJ (2003) Replication protein A-mediated recruitment and activation of Rad17 complexes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100 : 13827–13832.

16. LeeJ, KumagaiA, DunphyWG (2007) The Rad9-Hus1-Rad1 checkpoint clamp regulates interaction of TopBP1 with ATR. The Journal of biological chemistry 282 : 28036–28044.

17. Cotta-RamusinoC, McDonaldER3rd, HurovK, SowaME, HarperJW, et al. (2011) A DNA damage response screen identifies RHINO, a 9-1-1 and TopBP1 interacting protein required for ATR signaling. Science 332 : 1313–1317.

18. WangH, ElledgeSJ (2002) Genetic and physical interactions between DPB11 and DDC1 in the yeast DNA damage response pathway. Genetics 160 : 1295–1304.

19. DelacroixS, WagnerJM, KobayashiM, YamamotoK, KarnitzLM (2007) The Rad9-Hus1-Rad1 (9-1-1) clamp activates checkpoint signaling via TopBP1. Genes & development 21 : 1472–1477.

20. FuruyaK, PoiteleaM, GuoL, CaspariT, CarrAM (2004) Chk1 activation requires Rad9 S/TQ-site phosphorylation to promote association with C-terminal BRCT domains of Rad4TOPBP1. Genes & development 18 : 1154–1164.

21. GarciaV, FuruyaK, CarrAM (2005) Identification and functional analysis of TopBP1 and its homologs. DNA repair 4 : 1227–1239.

22. BorkP, HofmannK, BucherP, NeuwaldAF, AltschulSF, et al. (1997) A superfamily of conserved domains in DNA damage-responsive cell cycle checkpoint proteins. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 11 : 68–76.

23. YuX, ChiniCC, HeM, MerG, ChenJ (2003) The BRCT domain is a phospho-protein binding domain. Science 302 : 639–642.

24. ZegermanP, DiffleyJF (2007) Phosphorylation of Sld2 and Sld3 by cyclin-dependent kinases promotes DNA replication in budding yeast. Nature 445 : 281–285.

25. BoosD, Sanchez-PulidoL, RappasM, PearlLH, OliverAW, et al. (2011) Regulation of DNA replication through Sld3-Dpb11 interaction is conserved from yeast to humans. Current biology : CB 21 : 1152–1157.

26. BalestriniA, CosentinoC, ErricoA, GarnerE, CostanzoV (2010) GEMC1 is a TopBP1-interacting protein required for chromosomal DNA replication. Nature cell biology 12 : 484–491.

27. KumagaiA, ShevchenkoA, DunphyWG (2010) Treslin collaborates with TopBP1 in triggering the initiation of DNA replication. Cell 140 : 349–359.

28. SweeneyFD, YangF, ChiA, ShabanowitzJ, HuntDF, et al. (2005) Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad9 acts as a Mec1 adaptor to allow Rad53 activation. Current biology : CB 15 : 1364–1375.

29. MochidaS, EsashiF, AonoN, TamaiK, O'ConnellMJ, et al. (2004) Regulation of checkpoint kinases through dynamic interaction with Crb2. The EMBO journal 23 : 418–428.

30. QuM, YangB, TaoL, YatesJR3rd, RussellP, et al. (2012) Phosphorylation-dependent interactions between Crb2 and Chk1 are essential for DNA damage checkpoint. PLoS genetics 8: e1002817.

31. KumagaiA, LeeJ, YooHY, DunphyWG (2006) TopBP1 activates the ATR-ATRIP complex. Cell 124 : 943–955.

32. LinSJ, WardlawCP, MorishitaT, MiyabeI, ChahwanC, et al. (2012) The Rad4(TopBP1) ATR-activation domain functions in G1/S phase in a chromatin-dependent manner. PLoS genetics 8: e1002801.

33. Navadgi-PatilVM, BurgersPM (2008) Yeast DNA replication protein Dpb11 activates the Mec1/ATR checkpoint kinase. The Journal of biological chemistry 283 : 35853–35859.

34. MordesDA, GlickGG, ZhaoR, CortezD (2008) TopBP1 activates ATR through ATRIP and a PIKK regulatory domain. Genes & development 22 : 1478–1489.

35. LimboO, Porter-GoffME, RhindN, RussellP (2011) Mre11 nuclease activity and Ctp1 regulate Chk1 activation by Rad3ATR and Tel1ATM checkpoint kinases at double-strand breaks. Molecular and cellular biology 31 : 573–583.

36. UsuiT, OgawaH, PetriniJH (2001) A DNA damage response pathway controlled by Tel1 and the Mre11 complex. Molecular cell 7 : 1255–1266.

37. JeonY, LeeKY, KoMJ, LeeYS, KangS, et al. (2007) Human TopBP1 participates in cyclin E/CDK2 activation and preinitiation complex assembly during G1/S transition. The Journal of biological chemistry 282 : 14882–14890.

38. KimJE, McAvoySA, SmithDI, ChenJ (2005) Human TopBP1 ensures genome integrity during normal S phase. Molecular and cellular biology 25 : 10907–10915.

39. LiuK, LuoY, LinFT, LinWC (2004) TopBP1 recruits Brg1/Brm to repress E2F1-induced apoptosis, a novel pRb-independent and E2F1-specific control for cell survival. Genes & development 18 : 673–686.

40. LiuK, BellamN, LinHY, WangB, StockardCR, et al. (2009) Regulation of p53 by TopBP1: a potential mechanism for p53 inactivation in cancer. Molecular and cellular biology 29 : 2673–2693.

41. YamaneK, WuX, ChenJ (2002) A DNA damage-regulated BRCT-containing protein, TopBP1, is required for cell survival. Molecular and cellular biology 22 : 555–566.

42. LeeY, KatyalS, DowningSM, ZhaoJ, RussellHR, et al. (2012) Neurogenesis requires TopBP1 to prevent catastrophic replicative DNA damage in early progenitors. Nature neuroscience 15 : 819–826.

43. ToledoLI, MurgaM, ZurR, SoriaR, RodriguezA, et al. (2011) A cell-based screen identifies ATR inhibitors with synthetic lethal properties for cancer-associated mutations. Nature structural & molecular biology 18 : 721–727.

44. GruberR, ZhouZ, SukchevM, JoerssT, FrappartPO, et al. (2011) MCPH1 regulates the neuroprogenitor division mode by coupling the centrosomal cycle with mitotic entry through the Chk1-Cdc25 pathway. Nature cell biology 13 : 1325–1334.

45. LiuK, LinFT, RuppertJM, LinWC (2003) Regulation of E2F1 by BRCT domain-containing protein TopBP1. Molecular and cellular biology 23 : 3287–3304.

46. LiuK, PaikJC, WangB, LinFT, LinWC (2006) Regulation of TopBP1 oligomerization by Akt/PKB for cell survival. The EMBO journal 25 : 4795–4807.

47. XuX, TsvetkovLM, SternDF (2002) Chk2 activation and phosphorylation-dependent oligomerization. Molecular and cellular biology 22 : 4419–4432.

48. Navadgi-PatilVM, BurgersPM (2009) The unstructured C-terminal tail of the 9-1-1 clamp subunit Ddc1 activates Mec1/ATR via two distinct mechanisms. Molecular cell 36 : 743–753.

49. KumarS, BurgersPM (2013) Lagging strand maturation factor Dna2 is a component of the replication checkpoint initiation machinery. Genes & development 27 : 313–321.

50. ZouL (2013) Four pillars of the S-phase checkpoint. Genes & development 27 : 227–233.

51. JeonY, KoE, LeeKY, KoMJ, ParkSY, et al. (2011) TopBP1 deficiency causes an early embryonic lethality and induces cellular senescence in primary cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 286 : 5414–5422.

52. BrownEJ, BaltimoreD (2000) ATR disruption leads to chromosomal fragmentation and early embryonic lethality. Genes & development 14 : 397–402.

53. de KleinA, MuijtjensM, van OsR, VerhoevenY, SmitB, et al. (2000) Targeted disruption of the cell-cycle checkpoint gene ATR leads to early embryonic lethality in mice. Current biology : CB 10 : 479–482.

54. BrownEJ, BaltimoreD (2003) Essential and dispensable roles of ATR in cell cycle arrest and genome maintenance. Genes & development 17 : 615–628.

55. WoolfPJ, LindermanJJ (2003) Self organization of membrane proteins via dimerization. Biophysical chemistry 104 : 217–227.

56. YooHY, KumagaiA, ShevchenkoA, DunphyWG (2007) Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM)-dependent activation of ATR occurs through phosphorylation of TopBP1 by ATM. The Journal of biological chemistry 282 : 17501–17506.

57. Lindsey-BoltzLA, SancarA (2011) Tethering DNA damage checkpoint mediator proteins topoisomerase IIbeta-binding protein 1 (TopBP1) and Claspin to DNA activates ataxia-telangiectasia mutated and RAD3-related (ATR) phosphorylation of checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1). The Journal of biological chemistry 286 : 19229–19236.

58. ZhouZ, SunX, ZouZ, SunL, ZhangT, et al. (2010) PRMT5 regulates Golgi apparatus structure through methylation of the golgin GM130. Cell research 20 : 1023–1033.

59. WangZQ, AuerB, StinglL, BerghammerH, HaidacherD, et al. (1995) Mice lacking ADPRT and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation develop normally but are susceptible to skin disease. Genes & development 9 : 509–520.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Re-Ranking Sequencing Variants in the Post-GWAS Era for Accurate Causal Variant IdentificationČlánek Bypass of 8-oxodGČlánek Integrated Model of and Inherited Genetic Variants Yields Greater Power to Identify Risk GenesČlánek Comparative Genomic and Functional Analysis of 100 Strains and Their Comparison with Strain GGČlánek A Nuclear Calcium-Sensing Pathway Is Critical for Gene Regulation and Salt Stress Tolerance inČlánek Computational Identification of Diverse Mechanisms Underlying Transcription Factor-DNA OccupancyČlánek Reversible and Rapid Transfer-RNA Deactivation as a Mechanism of Translational Repression in StressČlánek Genome-Wide Association of Body Fat Distribution in African Ancestry Populations Suggests New Loci

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2013 Číslo 8- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Reveals Persistent Hypomethylation of Interferon Genes and Compositional Changes to CD4+ T-cell Populations

- Re-Ranking Sequencing Variants in the Post-GWAS Era for Accurate Causal Variant Identification

- Histone Variant HTZ1 Shows Extensive Epistasis with, but Does Not Increase Robustness to, New Mutations

- Past Visits Present: TCF/LEFs Partner with ATFs for β-Catenin–Independent Activity

- Functional Characterisation of Alpha-Galactosidase A Mutations as a Basis for a New Classification System in Fabry Disease

- A Flexible Approach for the Analysis of Rare Variants Allowing for a Mixture of Effects on Binary or Quantitative Traits

- Masculinization of Gene Expression Is Associated with Exaggeration of Male Sexual Dimorphism

- Genic Intolerance to Functional Variation and the Interpretation of Personal Genomes

- Endogenous Stress Caused by Faulty Oxidation Reactions Fosters Evolution of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene-Degrading Bacteria

- Transposon Domestication versus Mutualism in Ciliate Genome Rearrangements

- Comparative Anatomy of Chromosomal Domains with Imprinted and Non-Imprinted Allele-Specific DNA Methylation

- An Essential Function for the ATR-Activation-Domain (AAD) of TopBP1 in Mouse Development and Cellular Senescence

- Depletion of Retinoic Acid Receptors Initiates a Novel Positive Feedback Mechanism that Promotes Teratogenic Increases in Retinoic Acid

- Bypass of 8-oxodG

- Calpain-6 Deficiency Promotes Skeletal Muscle Development and Regeneration

- ATM Release at Resected Double-Strand Breaks Provides Heterochromatin Reconstitution to Facilitate Homologous Recombination

- Generation of Tandem Direct Duplications by Reversed-Ends Transposition of Maize Elements

- Loss of a Conserved tRNA Anticodon Modification Perturbs Cellular Signaling

- Integrated Model of and Inherited Genetic Variants Yields Greater Power to Identify Risk Genes

- High-Throughput Genetic and Gene Expression Analysis of the RNAPII-CTD Reveals Unexpected Connections to SRB10/CDK8

- Dynamic Rewiring of the Retinal Determination Network Switches Its Function from Selector to Differentiation

- β-Catenin-Independent Activation of TCF1/LEF1 in Human Hematopoietic Tumor Cells through Interaction with ATF2 Transcription Factors

- Genetic Mapping of Specific Interactions between Mosquitoes and Dengue Viruses

- A Highly Redundant Gene Network Controls Assembly of the Outer Spore Wall in

- Origin and Functional Diversification of an Amphibian Defense Peptide Arsenal

- Myc-Driven Overgrowth Requires Unfolded Protein Response-Mediated Induction of Autophagy and Antioxidant Responses in

- Integrative Modeling of eQTLs and Cis-Regulatory Elements Suggests Mechanisms Underlying Cell Type Specificity of eQTLs

- Species and Population Level Molecular Profiling Reveals Cryptic Recombination and Emergent Asymmetry in the Dimorphic Mating Locus of

- Ras-Induced Changes in H3K27me3 Occur after Those in Transcriptional Activity

- Characterization of the p53 Cistrome – DNA Binding Cooperativity Dissects p53's Tumor Suppressor Functions

- Global Analysis of Fission Yeast Mating Genes Reveals New Autophagy Factors

- Deficiency Suppresses Intestinal Tumorigenesis

- Introns Regulate Gene Expression in in a Pab2p Dependent Pathway

- Meiotic Recombination Initiation in and around Retrotransposable Elements in

- Comparative Oncogenomic Analysis of Copy Number Alterations in Human and Zebrafish Tumors Enables Cancer Driver Discovery

- Comparative Genomic and Functional Analysis of 100 Strains and Their Comparison with Strain GG

- A Model-Based Analysis of GC-Biased Gene Conversion in the Human and Chimpanzee Genomes

- Masculinization of the X Chromosome in the Pea Aphid

- The Architecture of a Prototypical Bacterial Signaling Circuit Enables a Single Point Mutation to Confer Novel Network Properties

- Distinct SUMO Ligases Cooperate with Esc2 and Slx5 to Suppress Duplication-Mediated Genome Rearrangements

- The Yeast Environmental Stress Response Regulates Mutagenesis Induced by Proteotoxic Stress

- Mediator Directs Co-transcriptional Heterochromatin Assembly by RNA Interference-Dependent and -Independent Pathways

- The Genome of and the Basis of Host-Microsporidian Interactions

- Regulation of Sister Chromosome Cohesion by the Replication Fork Tracking Protein SeqA

- Neuronal Reprograming of Protein Homeostasis by Calcium-Dependent Regulation of the Heat Shock Response

- A Nuclear Calcium-Sensing Pathway Is Critical for Gene Regulation and Salt Stress Tolerance in

- Cross-Species Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization Identifies Novel Oncogenic Events in Zebrafish and Human Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma

- : A Mouse Strain with an Ift140 Mutation That Results in a Skeletal Ciliopathy Modelling Jeune Syndrome

- The Relative Contribution of Proximal 5′ Flanking Sequence and Microsatellite Variation on Brain Vasopressin 1a Receptor () Gene Expression and Behavior

- Combining Quantitative Genetic Footprinting and Trait Enrichment Analysis to Identify Fitness Determinants of a Bacterial Pathogen

- The Innocence Project at Twenty: An Interview with Barry Scheck

- Computational Identification of Diverse Mechanisms Underlying Transcription Factor-DNA Occupancy

- GUESS-ing Polygenic Associations with Multiple Phenotypes Using a GPU-Based Evolutionary Stochastic Search Algorithm

- H2A.Z Acidic Patch Couples Chromatin Dynamics to Regulation of Gene Expression Programs during ESC Differentiation

- Identification of DSB-1, a Protein Required for Initiation of Meiotic Recombination in , Illuminates a Crossover Assurance Checkpoint

- Binding of TFIIIC to SINE Elements Controls the Relocation of Activity-Dependent Neuronal Genes to Transcription Factories

- Global Analysis of the Sporulation Pathway of

- Genetic Circuits that Govern Bisexual and Unisexual Reproduction in

- Deletion of microRNA-80 Activates Dietary Restriction to Extend Healthspan and Lifespan

- Fifty Years On: GWAS Confirms the Role of a Rare Variant in Lung Disease

- The Enhancer Landscape during Early Neocortical Development Reveals Patterns of Dense Regulation and Co-option

- Gene Expression Regulation by Upstream Open Reading Frames and Human Disease

- Sociogenomics of Cooperation and Conflict during Colony Founding in the Fire Ant

- The Intronic Long Noncoding RNA Recruits PRC2 to the Promoter, Reducing the Expression of and Increasing Cell Proliferation

- The , p.E318G Variant Increases the Risk of Alzheimer's Disease in -ε4 Carriers

- The Wilms Tumor Gene, , Is Critical for Mouse Spermatogenesis via Regulation of Sertoli Cell Polarity and Is Associated with Non-Obstructive Azoospermia in Humans

- Reversible and Rapid Transfer-RNA Deactivation as a Mechanism of Translational Repression in Stress

- QTL Analysis of High Thermotolerance with Superior and Downgraded Parental Yeast Strains Reveals New Minor QTLs and Converges on Novel Causative Alleles Involved in RNA Processing

- Genome Wide Association Identifies Novel Loci Involved in Fungal Communication

- Chromatin Sampling—An Emerging Perspective on Targeting Polycomb Repressor Proteins

- A Recessive Founder Mutation in Regulator of Telomere Elongation Helicase 1, , Underlies Severe Immunodeficiency and Features of Hoyeraal Hreidarsson Syndrome

- Genome-Wide Association of Body Fat Distribution in African Ancestry Populations Suggests New Loci

- Causal and Synthetic Associations of Variants in the Gene Cluster with Alpha1-antitrypsin Serum Levels

- Hard Selective Sweep and Ectopic Gene Conversion in a Gene Cluster Affording Environmental Adaptation

- Brittle Culm1, a COBRA-Like Protein, Functions in Cellulose Assembly through Binding Cellulose Microfibrils

- Chromosomal Copy Number Variation, Selection and Uneven Rates of Recombination Reveal Cryptic Genome Diversity Linked to Pathogenicity

- The Ribosomal Protein Rpl22 Controls Ribosome Composition by Directly Repressing Expression of Its Own Paralog, Rpl22l1

- Ras1 Acts through Duplicated Cdc42 and Rac Proteins to Regulate Morphogenesis and Pathogenesis in the Human Fungal Pathogen

- The DSB-2 Protein Reveals a Regulatory Network that Controls Competence for Meiotic DSB Formation and Promotes Crossover Assurance

- Recurrent Modification of a Conserved -Regulatory Element Underlies Fruit Fly Pigmentation Diversity

- Associations of Mitochondrial Haplogroups B4 and E with Biliary Atresia and Differential Susceptibility to Hydrophobic Bile Acid

- The Conditional Nature of Genetic Interactions: The Consequences of Wild-Type Backgrounds on Mutational Interactions in a Genome-Wide Modifier Screen

- A Critical Function of Mad2l2 in Primordial Germ Cell Development of Mice

- A Role for CF1A 3′ End Processing Complex in Promoter-Associated Transcription

- Vitellogenin Underwent Subfunctionalization to Acquire Caste and Behavioral Specific Expression in the Harvester Ant

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Chromosomal Copy Number Variation, Selection and Uneven Rates of Recombination Reveal Cryptic Genome Diversity Linked to Pathogenicity

- Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Reveals Persistent Hypomethylation of Interferon Genes and Compositional Changes to CD4+ T-cell Populations

- Associations of Mitochondrial Haplogroups B4 and E with Biliary Atresia and Differential Susceptibility to Hydrophobic Bile Acid

- A Role for CF1A 3′ End Processing Complex in Promoter-Associated Transcription

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy