-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Genetic Determinants of Serum Testosterone Concentrations in Men

Testosterone concentrations in men are associated with cardiovascular morbidity, osteoporosis, and mortality and are affected by age, smoking, and obesity. Because of serum testosterone's high heritability, we performed a meta-analysis of genome-wide association data in 8,938 men from seven cohorts and followed up the genome-wide significant findings in one in silico (n = 871) and two de novo replication cohorts (n = 4,620) to identify genetic loci significantly associated with serum testosterone concentration in men. All these loci were also associated with low serum testosterone concentration defined as <300 ng/dl. Two single-nucleotide polymorphisms at the sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) locus (17p13-p12) were identified as independently associated with serum testosterone concentration (rs12150660, p = 1.2×10−41 and rs6258, p = 2.3×10−22). Subjects with ≥3 risk alleles of these variants had 6.5-fold higher risk of having low serum testosterone than subjects with no risk allele. The rs5934505 polymorphism near FAM9B on the X chromosome was also associated with testosterone concentrations (p = 5.6×10−16). The rs6258 polymorphism in exon 4 of SHBG affected SHBG's affinity for binding testosterone and the measured free testosterone fraction (p<0.01). Genetic variants in the SHBG locus and on the X chromosome are associated with a substantial variation in testosterone concentrations and increased risk of low testosterone. rs6258 is the first reported SHBG polymorphism, which affects testosterone binding to SHBG and the free testosterone fraction and could therefore influence the calculation of free testosterone using law-of-mass-action equation.

Published in the journal: Genetic Determinants of Serum Testosterone Concentrations in Men. PLoS Genet 7(10): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002313

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002313Summary

Testosterone concentrations in men are associated with cardiovascular morbidity, osteoporosis, and mortality and are affected by age, smoking, and obesity. Because of serum testosterone's high heritability, we performed a meta-analysis of genome-wide association data in 8,938 men from seven cohorts and followed up the genome-wide significant findings in one in silico (n = 871) and two de novo replication cohorts (n = 4,620) to identify genetic loci significantly associated with serum testosterone concentration in men. All these loci were also associated with low serum testosterone concentration defined as <300 ng/dl. Two single-nucleotide polymorphisms at the sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) locus (17p13-p12) were identified as independently associated with serum testosterone concentration (rs12150660, p = 1.2×10−41 and rs6258, p = 2.3×10−22). Subjects with ≥3 risk alleles of these variants had 6.5-fold higher risk of having low serum testosterone than subjects with no risk allele. The rs5934505 polymorphism near FAM9B on the X chromosome was also associated with testosterone concentrations (p = 5.6×10−16). The rs6258 polymorphism in exon 4 of SHBG affected SHBG's affinity for binding testosterone and the measured free testosterone fraction (p<0.01). Genetic variants in the SHBG locus and on the X chromosome are associated with a substantial variation in testosterone concentrations and increased risk of low testosterone. rs6258 is the first reported SHBG polymorphism, which affects testosterone binding to SHBG and the free testosterone fraction and could therefore influence the calculation of free testosterone using law-of-mass-action equation.

Introduction

Testosterone, the most important testicular androgen in men, is largely bound to two plasma proteins. Most of the circulating testosterone (∼50–60%) is bound with high affinity to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), while a smaller fraction (40–50%) is bound loosely to albumin, and 1–3% is unbound and termed free testosterone [1]. In prospective cohort studies, low serum testosterone concentrations are associated with cardiovascular morbidity, metabolic syndrome [2], [3], dyslipidemia [4], hypertension [5], type 2 diabetes mellitus [6], stroke [7], atherosclerosis [8]–[10], osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and increased mortality risk [11]–[13]. Thus, there is growing evidence that serum testosterone is a valuable biomarker of men's overall health status. Since age, body mass index (BMI), and smoking are known to affect serum testosterone concentrations [14], we used these parameters as common set of covariates in all association models. Studies in male twins indicate that there is a strong heritability of serum testosterone, with genetic factors accounting for 65% of the variation in serum testosterone [15]. However, the genetic determinants of serum testosterone and the genetic risk factors for low concentrations are poorly understood. Given the current gap in knowledge of the genetic factors that contribute to the inter-individual variability in serum testosterone concentration in men we conducted a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies (GWAS). This two-stage meta-analysis included data from 14,429 Caucasian men from 10 independent cohorts within the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium. In stage one, the discovery stage, genome-wide association data from seven cohorts were meta-analyzed (n = 8,938) and all genome-wide significant findings that fulfilled the criteria described in the methods section were followed up in the three replication cohorts: one in silico replication cohort (n = 871) and two replication cohorts with de novo genotyping (n = 4,620). All association analyses of the discovery stage were conducted both with and without additional adjustment for serum SHBG concentrations. Our primary aim was to identify genetic variants reproducibly associated with serum testosterone concentrations in men, evaluated as a continuous trait. We also assessed whether the lead single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from the continuous trait analyses had a significant influence on the risk of having low serum testosterone, defined as <300 ng/dl [16]. This level is slightly lower than that suggested recently by Wu et al. [11 nmol/l = 317 ng/dl] as one of the clinical criteria for late onset hypogonadism [17].

Results

Meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies for autosomal SNPs

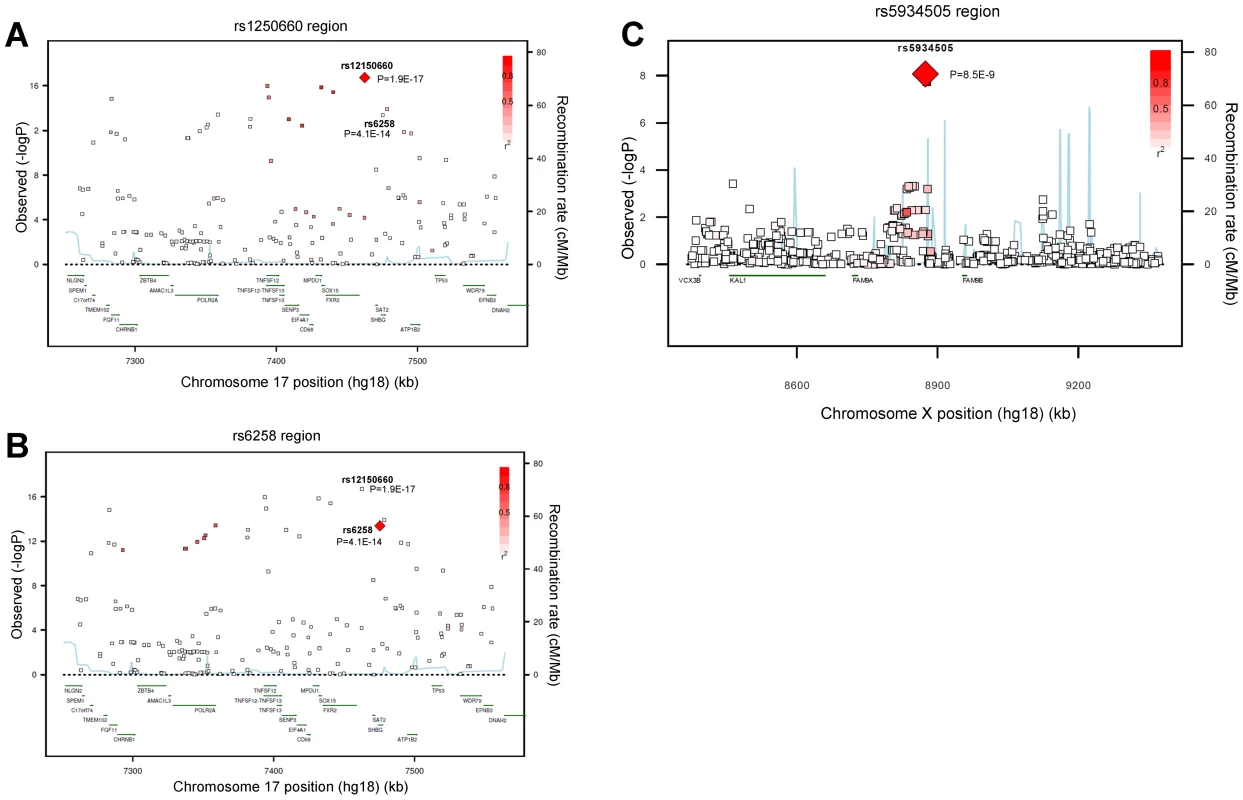

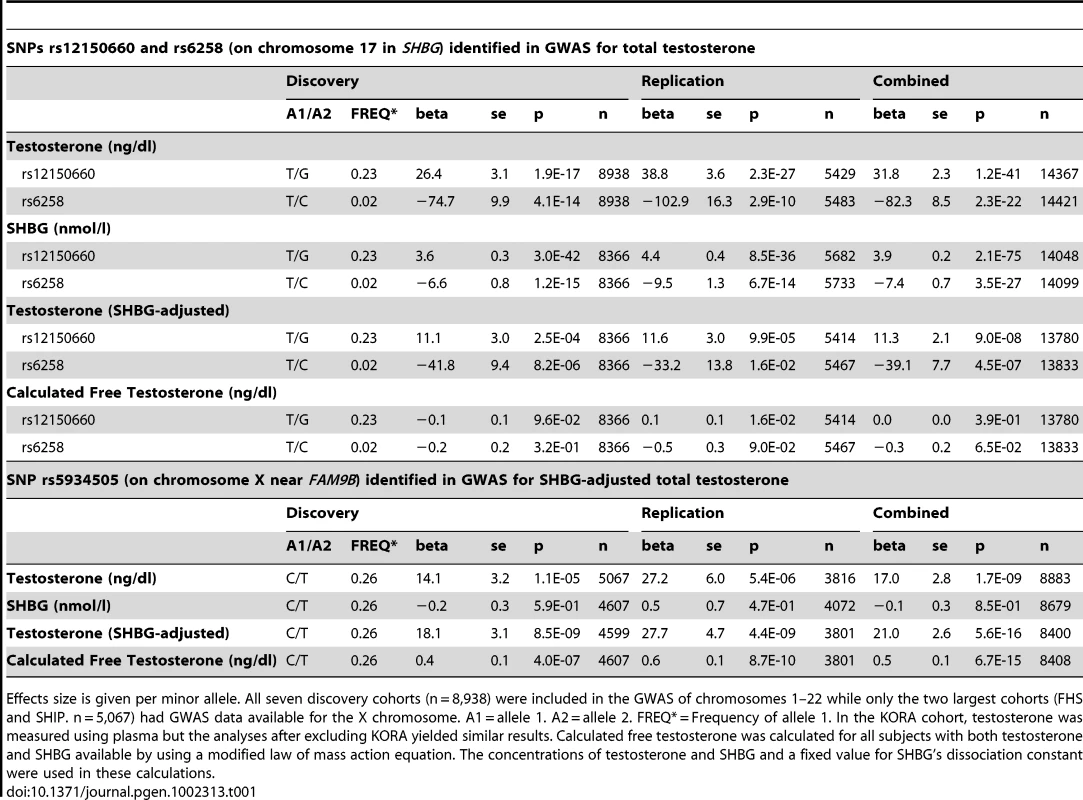

We performed a GWAS of serum testosterone concentrations, investigating ∼2.5 million SNPs in 8,938 men of Caucasian ancestry, 18 to 98 years, from seven cohorts. Genome-wide significant SNPs were found in the discovery analysis at one locus on chromosome 17 (17p13-p12) using the criteria described in the methods. The strongest association was found for rs12150660 (p = 1.9×10−17), located 11.5 kb upstream of the major transcription start site of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of 23% (Table 1 [SNPs rs12150660 and rs6258], Figure 1A and Figures S1A, S2 and S3). Tests for independently associated SNPs with serum testosterone in this region revealed a second SNP, rs6258 (p = 4.1×10−14), which represents a missense (P→L) polymorphism located in exon 4 of SHBG (Table 1 [SNPs rs12150660 and rs6258], Figure 1B) and which had a MAF of 2%. Based on HapMap release 22 (CEU), the r2 between rs12150660 and rs6258 was 0.004. To validate the independence of these two SNPs, conditional meta-analysis of the discovery cohorts including both rs12150660 and rs6258 in an additive genetic linear model adjusted for covariates was calculated. Because the associations remained significant and mostly unchanged (rs12150660, p = 7.0×10−14; rs6258, p = 1.6×10−13), both SNPs were independently associated with serum testosterone concentrations. No additional autosomal locus fulfilled the criteria for genome-wide significance.

Fig. 1. Regional association plots for single-nucleotide polymorphisms rs12150660, rs6258, and rs5934505.

Regional association plot of the two independent signals on chromosome 17 with either (A) rs12150660 or (B) rs6258 indicated by red diamond to evaluate linkage with other single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the region. In addition, the association plot of the (C) rs5934505 signal on chromosome X is given. The r2 is based on the CEU HapMap II samples. The blue line and right hand Y axis represent CEU HapMap II based recombination rates. (A) and (B) show the top SNPs of the inverse-variance weighted discovery stage meta-analysis of untransformed serum testosterone and (C) show the top SNP of the SHBG-adjusted serum testosterone using an imputation quality filter (observed/expected variance ratio) >0.4 at the individual cohort level during meta-analysis. Tab. 1. Meta-analyses of discovery and replication cohorts.

Effects size is given per minor allele. All seven discovery cohorts (n = 8,938) were included in the GWAS of chromosomes 1–22 while only the two largest cohorts (FHS and SHIP. n = 5,067) had GWAS data available for the X chromosome. A1 = allele 1. A2 = allele 2. FREQ* = Frequency of allele 1. In the KORA cohort, testosterone was measured using plasma but the analyses after excluding KORA yielded similar results. Calculated free testosterone was calculated for all subjects with both testosterone and SHBG available by using a modified law of mass action equation. The concentrations of testosterone and SHBG and a fixed value for SHBG's dissociation constant were used in these calculations. Replication of autosomal hits

The associations of rs12150660 and rs6258 were confirmed in the three replication cohorts (in silico replication in YFS and de novo replication in MrOS Sweden and EMAS), demonstrating a combined p-value in the discovery and the replication cohorts of 1.2×10−41 and 2.3×10−22, respectively (Table 1 [SNPs rs12150660 and rs6258]). Both SNPs showed considerable heterogeneity of results across the studies as measured by the I2 statistic [18]. The I2 values for the discovery meta-analysis using the untransformed total testosterone values were 76.7% and 81.6% for rs12150660 and rs6258, respectively. The heterogeneity was reduced to 39.3% and 75.5% for rs12150660 and rs6258, respectively, by meta-analysing the z-score based untransformed total testosterone values and to 30.9% and 78.0%, respectively, by meta-analysing the inverse-normal transformed testosterone values. For rs12150660, a substantial amount of heterogeneity could be explained by phenotypic variation among the cohorts, whereas for rs6258 one cohort (InCHIANTI) showed consistent opposite effect directions in all models used. To take into account this heterogeneity, we additionally calculated a random effects model for untransformed total testosterone values. The association for rs12150660 remained genome-wide significant in the combined discovery and replication stage meta-analysis, the association for rs6258 reached genome-wide significance after excluding the InCHIANTI cohort (Table S3).

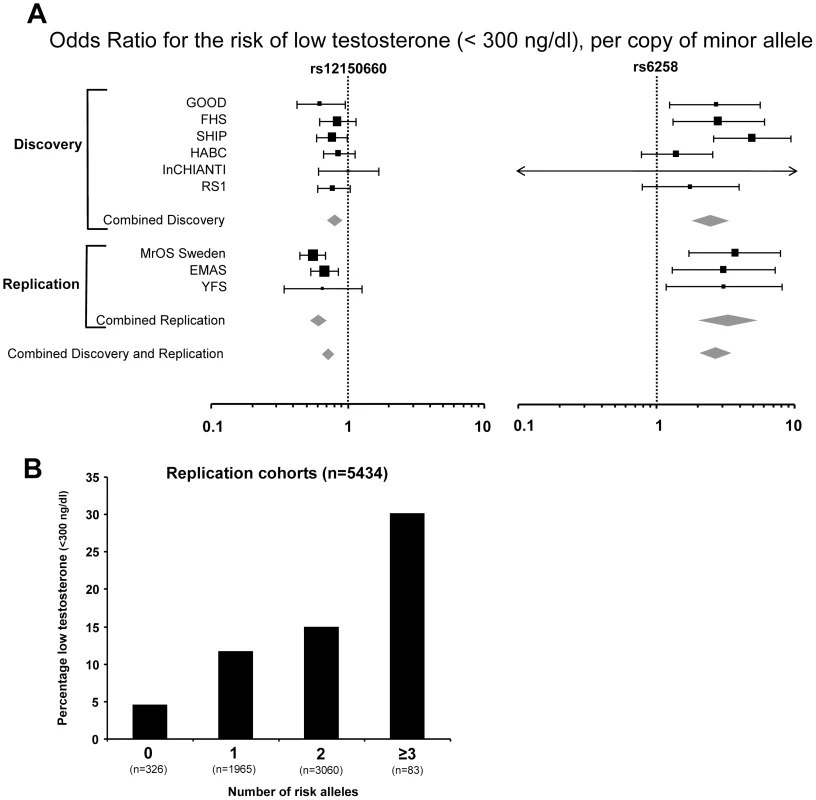

The genetic influence on low serum testosterone concentrations

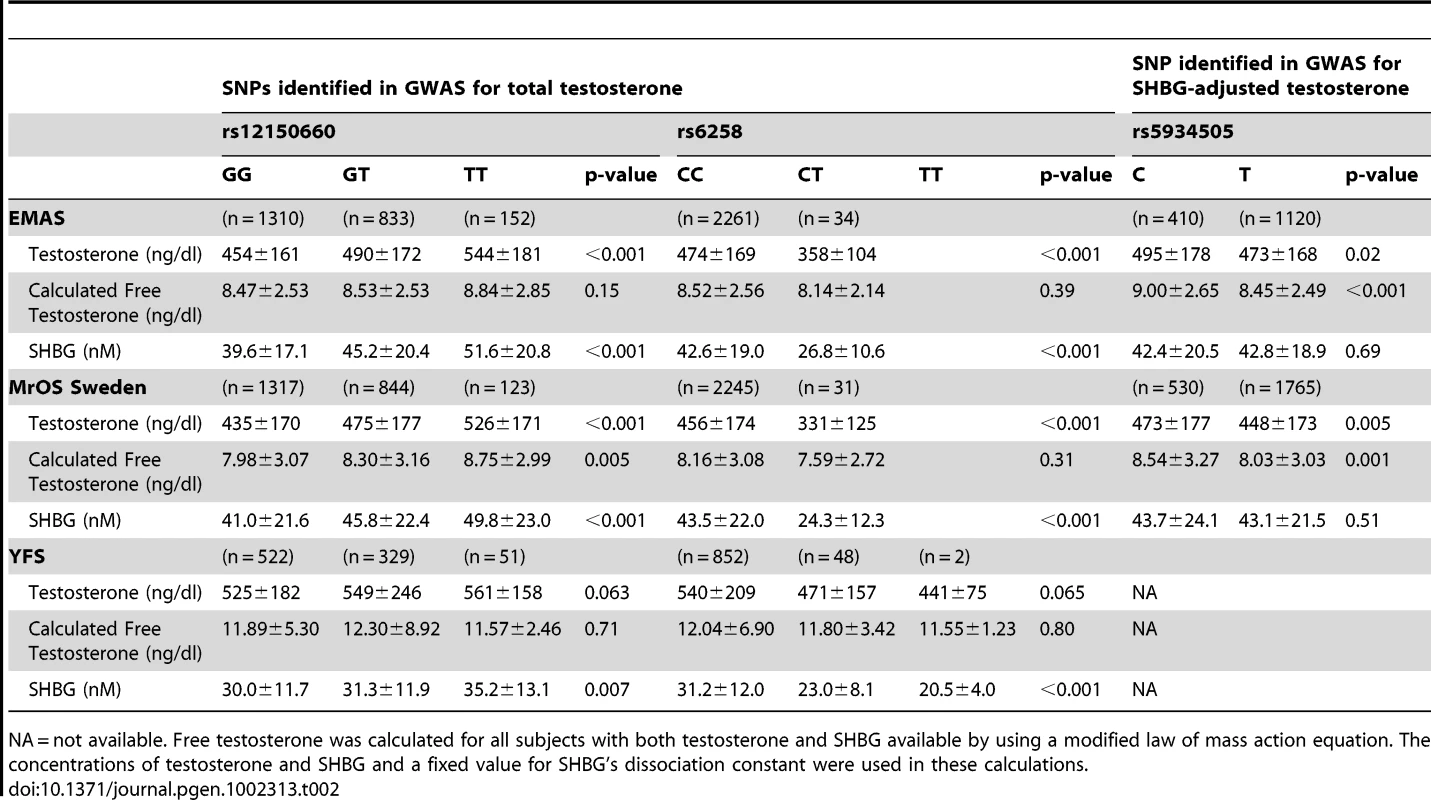

In Table 2, the serum testosterone concentrations according to genotype are given for the three replication cohorts. As expected, mean serum testosterone concentrations were found to be lower in men with GG than in those with TT genotype for rs12150660. Similarly, men with the CT genotype for rs6258 had lower serum testosterone concentrations than those with CC genotype. The TT genotype of rs6258 was extremely rare and only found in two subjects in the replication cohorts. The two autosomal SNPs identified by GWAS had a significant influence on the risk of having low serum testosterone (serum testosterone <300 ng/dl) in both the discovery and the replication cohorts with a combined odds ratio (OR) per minor allele of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.65 – 0.79) and 2.7 (95% CI, 2.1 – 3.5) for rs12150660 and rs6258, respectively (Figure 2A). We analyzed the combined effect of the two SNPs on the risk of having low serum testosterone concentrations according to the number of combined risk alleles for rs12150660 (G) and rs6258 (T) in the three replication cohorts (MrOS Sweden, EMAS, and YFS). The risk of having low serum testosterone concentrations increased by the number of risk alleles with an OR of 1.62 (95% CI, 1.41 – 1.86) for each risk allele (Figure S4). Low serum testosterone concentrations were 6.5-times more prevalent in men with ≥3 risk alleles (30.1% prevalence of low serum testosterone) compared to men without any risk allele (4.6% prevalence of low serum testosterone; Figure 2B).

Fig. 2. The genetic influence on low serum testosterone concentrations.

(A) Odds ratio (OR) for risk of low serum testosterone concentrations (serum testosterone <300 ng/dl), per copy of minor allele. Summary estimates of the OR and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) are given. The size of the data markers is proportional to the weight (inverse of the variance) of each study. Combined discovery (n = 8,030, low serum testosterone 13%; KORA was not included as testosterone was analyzed in plasma rather than in serum, combined replication (n = 5,504, low serum testosterone 13%), and combined discovery and replication (n = 13,534, low serum testosterone 13%). (B) Percentage of men with low serum testosterone concentrations (serum testosterone <300 ng/dl), according to the number of combined risk alleles for rs12150660 (G) and rs6258 (T) in the three replication cohorts (MrOS Sweden, EMAS, and YFS). Only two individuals in the three replication cohorts had four risk alleles and therefore individuals with three and four risk alleles were pooled into one group with ≥3 risk alleles. Tab. 2. Serum sex steroids in the three replication cohorts according to rs12150660, rs6258, and rs5934505 genotype.

NA = not available. Free testosterone was calculated for all subjects with both testosterone and SHBG available by using a modified law of mass action equation. The concentrations of testosterone and SHBG and a fixed value for SHBG's dissociation constant were used in these calculations. The role of SHBG in the observed associations

As SNP rs12150660 is located 11.5 kb upstream of SHBG and SNP rs6258 is non-synonymous and located in exon 4 of SHBG, we evaluated the influence of these polymorphisms on SHBG concentrations. Both of these polymorphisms demonstrated a significant association with SHBG concentrations in both the discovery and replication cohorts (Table 1 [SNPs rs12150660 and rs6258]). However, even after adjusting for SHBG concentrations, the associations between these two SNPs and serum testosterone concentrations were still significant (p = 9.0×10−8 for rs12150660 and p = 4.5×10−7 for rs6258). Free testosterone calculated using law-of-mass-action equation was not associated with either of the two polymorphisms (Table 1 [SNPs rs12150660 and rs6258]). As serum testosterone and SHBG are highly correlated (e.g., in MrOS Sweden rs = 0.53), variations in SHBG concentration might have influenced the observed associations of serum testosterone with other non-SHBG-related loci. Therefore, we performed an additional SHBG-adjusted genome-wide meta-analysis among the discovery cohorts, wherein none of the non-SHBG-related autosomal SNPs reached genome-wide significance (Figure S1B).

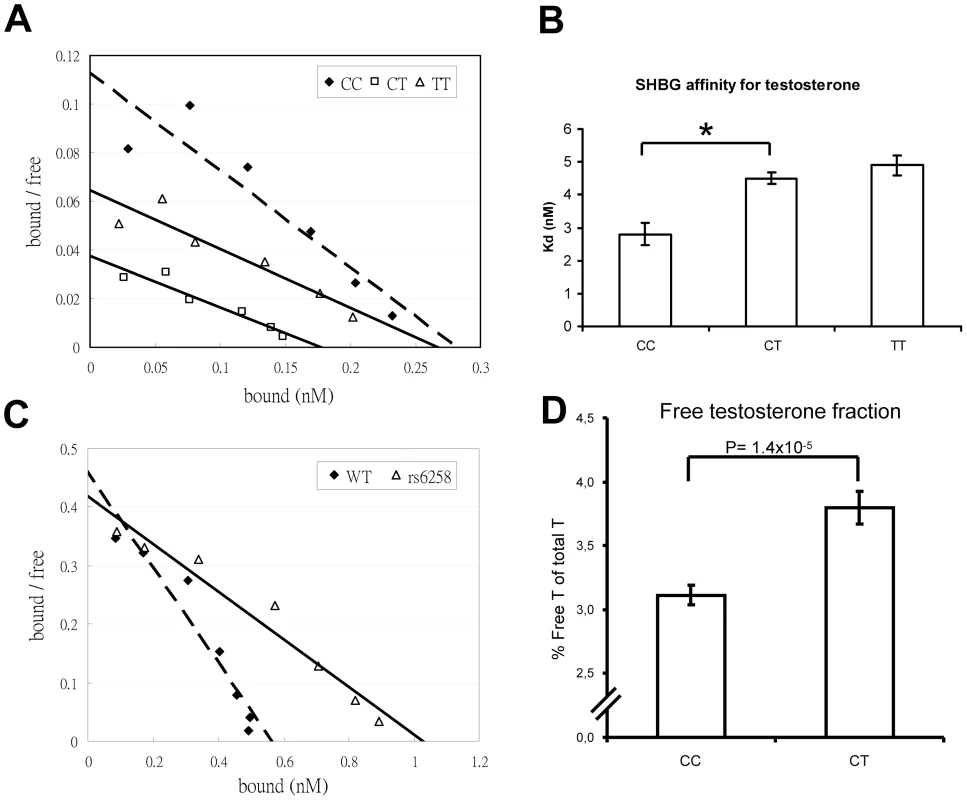

The rs6258 polymorphism affects SHBG binding affinity for testosterone and the measured free testosterone fraction

As rs6258 is non-synonymous (P156L) and located in exon 4 of SHBG, we evaluated the serum SHBG steroid-binding capacity of the different rs6258 genotypes. As shown in Figure S5, serum SHBG from CT but not CC subjects had a lower steroid-binding capacity than expected from values obtained by an SHBG immunoassay (p = 0.003). Therefore, we analyzed the SHBG affinity for testosterone using Scatchard plots of SHBG in serum of men with the rs6258 genotype (Figure 3A), and revealed (Figure 3B) a higher mean dissociation constant (Kd) indicative of a lower affinity in CT (Kd = 4.5 nM) and TT (Kd = 4.9 nM) individuals than in CC individuals (Kd = 2.8 nM). Recombinant SHBG corresponding to the T genotype demonstrated a higher dissociation constant (lower affinity) compared with recombinant SHBG corresponding to the C genotype (T genotype Kd 2.5 nM; C genotype Kd 1.2 nM, Figure 3C). In addition, the free testosterone fraction measured by an equilibrium dialysis method was 22% higher (p = 1.4×10−5) in serum from CT subjects than in serum from CC subjects (Figure 3D).

Fig. 3. SHBG affinity for testosterone.

(A and B) Scatchard plots of SHBG binding affinity for testosterone in serum samples according to rs6258 genotype. (A) Representative Scatchard plots of serum SHBG binding to [3H]testosterone. Serum from individuals homozygous for the wild-type SHBG allele (CC dashed line) or the rs6258 SNP (TT, solid line), or heterozygous for these alleles (CT, solid line). (B) Dissociation constant (Kd) of serum SHBG according to rs6258 genotype (CC, n = 4 subjects; CT, n = 4 subjects; TT [rare variant] n = 1 and the variation for the TT subject is derived from three separate analyses). (*) p = 0.001. Values are means ± SEM. (C) Representative Scatchard plots of recombinant SHBG binding to [3H]testosterone. Recombinant wild type ( = WT, C genotype; dashed line) or rs6258 (T genotype; solid line) SHBG expressed by CHO cells was diluted 1∶10 and subjected to Scatchard analysis, as in panel A. (D) Free testosterone fraction in serum measured by an equilibrium dialysis method according to rs6258 genotype (CC, n = 87 subjects; CT, n = 32 subjects). Values are means ± SEM. X chromosome analyses

Imputed values for X chromosome-located SNPs were available for the two larger discovery cohorts (SHIP and FHS; n = 5,067). We performed meta-analyses of imputed X chromosome SNPs for serum testosterone concentrations both with and without SHBG adjustment, revealing one genome-wide significant association for SNP rs5934505 (p = 8.5×10−9) in the SHBG-adjusted model (Table 1 [SNP rs5934505] and Figures S1B and S3). This SNP was confirmed in the two replication cohorts with de novo genotyping (MrOS Sweden p = 3.6×10−3; EMAS p = 1.5×10−7). Meta-analysis of discovery and replication cohorts resulted in a combined p-value of 5.6×10−16. The rs5934505 SNP is located in a CNV-insertion area (Xp22), 145 kb upstream of the family with sequence similarity 9, member A (FAM9A) and 79 kb downstream of the family with sequence similarity 9, member B (FAM9B) (Figure 1C). In addition, rs5934505 is located 214 kb upstream of Kallmann syndrome 1 sequence (KAL1). SNP rs5934505 was associated with serum testosterone without SHBG-adjustment (combined p-value of 1.7×10−9) and with free testosterone (combined p-value of 6.7×10−15), but not with SHBG (Table 1 [SNP rs5934505]). The mean serum testosterone and calculated free testosterone but not SHBG concentrations were lower in men with T genotype than in those with C genotype for rs5934505 (Table 2).

Discussion

This GWAS revealed novel genetic variants that significantly affect circulating testosterone concentrations in men. The presence of three or more risk alleles for the two polymorphisms in the SHBG loci resulted in markedly decreased testosterone concentrations compared to men with two or less risk alleles. Importantly, one of the identified genetic variations was associated with an alteration in SHBG's binding affinity for testosterone and the measured free testosterone fraction. In addition, we identified a locus on the X chromosome influencing serum testosterone concentrations. The genetic contribution of the polymorphisms to testosterone concentrations reported here is substantial; as a reference for comparison, the effect of these polymorphisms on testosterone concentrations in men is similar or greater than that for known risk factors such as age, smoking, and BMI [19], [20].

These findings improve our understanding of the genetic factors that affect serum testosterone concentrations and contribute to the variation in testosterone concentrations in men. These polymorphisms may assist in the identification of men at risk of low serum testosterone, although the clinical usefulness of these findings remains to be established. As rs12150660 and rs6258 were strongly associated with SHBG concentrations, both SNPs may at least partly affect total testosterone concentrations by modulating SHBG concentrations. Our findings that rs6258 substantially affects SHBG binding affinity and the measured free testosterone fraction raise questions about the use of a single consensus value for SHBG's dissociation constant in the law of mass action equations used to calculate free testosterone concentrations. As emphasized by the Endocrine Society's expert panel on androgen deficiency syndromes, low testosterone concentrations alone should not necessarily be viewed as evidence of androgen deficiency [16]. Whether rs593405 near the FAM9B and KAL1 genes on Xp22 renders men susceptible to the increased risk of androgen deficiency remains to be determined. Further studies are required to determine the impact of these genetic variations on sex steroid-related disorders, including osteoporosis, cardiovascular diseases, prostate cancer, and male infertility [21].

Our studies add to the evidence that genetic variations within the SHBG gene may explain some of the inter-individual differences in SHBG concentrations. Our finding that SNP rs6258 results in the production of an SHBG variant with reduced affinity for testosterone provides an explanation for the association between rs6258 and low serum testosterone concentrations. This is the first described genetic variant associated with altered SHBG binding for testosterone. As rs6258 is non-synonymous (P156L), located in exon 4 of SHBG and associated with altered SHBG binding for testosterone and free testosterone fraction, rs6258 is likely a functional polymorphism with impact on testosterone binding to SHBG as well as testosterone bioavailability and action at target tissue level.

The SNP rs12150660 that is strongly associated with testosterone concentrations is located 11.5 kb upstream of the coding sequence for SHBG mRNA production in the liver. However, it still resides within the human SHBG locus because several other alternative exon 1 sequences are located up to ∼13 kb upstream of the exon 1 sequence that encodes the secretion signal polypeptide of the SHBG precursor in the liver [22]. There are no obvious nuclear protein binding sites within the sequences spanning SNP rs12150660, and it remains to be determined whether this SNP disrupts a cis-element that directly influences SHBG transcription. We have found that rs12150660 is in strong LD (r2 = 0.89) with another common SNP (rs1799941) in the SHBG proximal promoter that was shown to be associated with serum SHBG concentrations [23]–[25]. Thus, it is highly likely that only one of these polymorphisms is actually functional and therefore both SNPs represent the same signal. It should also be noted that rs1799941 is linked to the number of TAAAA repeats within an Alu sequence upstream of SHBG promoter [26] and that the rs1799941 (A allele) is linked with the presence of six TAAAA repeats in this location which has been reported to be associated with higher SHBG concentrations [27]. In addition, while there does not appear to be any putative transcriptional factor binding sites with the sequence comprising rs12150660, it remains to be determined whether rs12150660 or these other associated SNPs in the SHBG gene are functionally important or simply represent proxies of SHBG and testosterone concentrations in men.

Our meta-analyses of imputed X chromosome SNPs revealed one genome-wide significant association for SNP rs5934505, located in a CNV-insertion area (Xp22), 145 kb upstream of family with sequence similarity 9, member A (FAM9A) and 79 kb downstream of family with sequence similarity 9, member B (FAM9B). Both genes, FAM9A and FAM9B, are expressed exclusively in the testis [28] and described here for the first time to be associated with total as well as free testosterone concentrations. rs5934505 is located 214 kb upstream of Kallmann syndrome 1 sequence (KAL1). Although the Kallmann syndrome, a type of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism associated with anosmia and other congenital anomalies, has been linked to mutations in the KAL1 gene on the X chromosome, only 11–14% of Caucasian patients with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism have detectable KAL1 mutations [29], reflecting the considerable genetic heterogeneity of this syndrome.

The strengths of our study include a discovery sample size of 8,938 men, which allowed us at the threshold α = 5×10−8,a 90% power to detect SNPs accounting for 0.5% of the total variance in serum testosterone concentrations, and 99% power to detect SNPs accounting for 1% of the total variance. The SNPs rs12150660, rs6258, and rs5934505 explained 2.3%, 0.9%, and 0.6%, respectively, of the variance in serum testosterone concentrations when evaluated in the MrOS Sweden replication cohort. Future meta-analyses including larger samples will probably reveal additional loci associated with serum testosterone. Further research into the functional significance of these variants will be needed to enable the translation of these findings into the mechanisms of sex steroid-related diseases and strategies for risk assessment. As the causal or etiological role of these polymorphisms in the genesis of low testosterone has not been established, the reported polymorphisms associated with low serum testosterone concentration may be viewed currently as risk markers rather than causal risk factors.

In conclusion, genetic variants in the SHBG locus and on the X chromosome are associated with a substantial variation in testosterone concentrations and increased risk of low testosterone in men. Further studies are needed to determine the impact of these genetic variations on sex hormone-related disorders. rs6258 is the first reported SHBG polymorphism, which affects testosterone binding to SHBG and the free testosterone fraction and could therefore influence the calculation of free testosterone using law-of-mass-action equation.

Methods

Study samples and genotyping

The discovery stage of the GWAS included 8,938 Caucasian men of European descent drawn from seven epidemiological cohorts: the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP), the Gothenburg Osteoporosis and Obesity Determinants (GOOD) study, the Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg (KORA) study, the Health, Aging and Body Composition (HEALTH ABC) study, the Rotterdam Study (RS1), and the Invecchiare in Chianti (InCHIANTI) (Table S1). The replication stage consisted of 4,620 men from two epidemiological cohorts (the European Male Ageing Study [EMAS] and the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men [MrOS] Sweden study) for de novo genotyping of the top SNPs and one additional cohort (the Young Finns Study, [YFS, n = 871]) with genome-wide association data available and joining the study after stage one was finished for in silico replication (Table S2).

Exclusion criteria included chemical or surgical castration and/or medications affecting sex hormones such as steroid 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, and sex hormone antagonists. All studies were approved by local ethics committees and all participants provided written informed consent. Characteristics of the study samples and detailed descriptions of the participating cohorts, genotyping methods, quality control, and imputation procedures are provided in Text S1.

Genotyping and statistical analyses

Altogether, ∼2.5 million SNPs, imputed using the HapMapII CEU population, were tested for association with serum testosterone in the discovery stage. Genome-wide association analyses using an additive genetic linear regression model adjusted for age, BMI, and current smoking were conducted twice within each of the discovery cohorts using serum testosterone expressed as ng/dl, as well as inverse-normal transformed serum testosterone as outcomes.

To examine the robustness of the discovery results and to reduce the risk of spurious associations due to possible testosterone measurement heterogeneity between the individual cohorts, three different types of meta-analyses were performed in the discovery stage: 1) an inverse-variance weighted fixed effect model; 2) a z-score based analysis of the untransformed serum testosterone concentrations; and 3) a z-score based meta-analysis of the inverse-normal transformed values. Model 1) was used as main analysis since it allowed the computation of effect estimates, whereas the other two analysis models were used for verification and quality control checks of the main findings. All meta-analyses were performed using METAL (www.sph.umich.edu/csg/abecasis/metal/). The random effects model of the two SHBG locus SNPs was calculated using the R-package metafor (www.r-project.org). Imputed genotypes were analyzed in all cohorts taking the genotype uncertainties into account. Genomic control was applied to each individual cohort's results and to the discovery stage meta-analysis to correct p-values for potential effects of mild population stratification. The estimated genomic control lambda was low for both the individual cohorts (range of λGC: 1.00–1.07) and the meta-analyses (range of λGC: 1.01–1.02), suggesting little residual confounding due to population stratification (Figure S2).

To reduce the variance on serum testosterone induced by SHBG concentration, the GWAS included a genome-wide test for association of untransformed serum testosterone concentrations adjusted for age, BMI, current smoking, SHBG and SHBG2 concentrations, again using both an inverse-variance weighted fixed effect as main analysis and a z-score based meta-analysis for quality control purposes.

A threshold of p<5×10−8 was established a priori as the level for genome-wide significance in the discovery analyses [30]. SNPs that reached genome-wide significance in the inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis of untransformed serum testosterone concentrations with or without adjustment for SHBG and which had association results in at least five of the seven cohorts (for chr X: two cohorts with data available) were selected for further analyses. Notably, all autosomal SNPs that fulfilled these criteria also reached genome-wide significance in the other two types of meta-analyses. From these SNPs, all independent SNPs were taken to the replication stage.

We also assessed whether the lead SNPs from the continuous trait analyses were associated with low serum testosterone concentration (defined as <300 ng/dl [16]; this level is slightly lower than that suggested recently by Wu et al [11 nmol/l = 317 ng/dl] [17]) by binary logistic regression including the same covariates in the model used for the main analysis and meta-analyzing the within-cohort results using inverse-variance weighted fixed-effect model. The KORA cohort was not included in the meta-analyses of low serum testosterone as testosterone was measured using plasma in this cohort.

We determined the number of low serum testosterone concentration risk alleles (0 to 4) for the two lead SNPs of the SHBG locus in each individual and assessed the risk of low serum testosterone concentrations in the three replication cohorts (MrOS Sweden, EMAS, and YFS) using a trend test. Since only two subjects in the replication cohorts had four risk alleles, individuals having three and four risk alleles were grouped into one category to obtain more reliable effect estimates during the subsequent analyses. Details of test for independence, SHBG related analysis of the top SNPs and quality control steps performed can be found in Text S1.

Sex hormone measurements

Methods for the measurement of serum testosterone and SHBG are given in Text S1. Calculated free testosterone was for all subjects with both testosterone and SHBG available (n = 13833; Table 1 and Table 2) calculated by using a modified law of mass action equation, as described by Mazer [31]. The concentrations of testosterone and SHBG and a fixed value for SHBG's dissociation constant were used in these calculations.

Free testosterone fraction

Free testosterone fraction was measured by an equilibrium dialysis method in 87 subjects with the CC genotype and 32 subjects with the CT genotype of rs6258 (Figure 3D) [32]. Detailed description of the free testosterone fraction measurements is provided in Text S1.

Sex hormone-binding globulin assays

In experiments evaluating SHBG binding capacity, serum SHBG concentrations were determined by two-site immunofluorometric assay (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Turku, Finland) [33], or by a steroid-binding capacity assay [34]. For steroid-binding assays, serum samples were pre-incubated with dextran-coated charcoal (DCC) to remove endogenous steroids, prior to incubation with either [3H]5α-dihydrotestosterone ([3H]DHT; specific activity 50 Ci/mmol) or [3H]testosterone (specific activity 40 Ci/mmol), bound from free [3H]steroid were separated using DCC as the separation reagent [34]. The steroid-binding properties of SHBG in diluted serum samples or tissue culture medium were determined by Scatchard analysis [34]. For the expression of SHBG protein, wild type (corresponding to the C genotype of rs6258) and rs6258 (corresponding to the T genotype of rs6258) SHBG cDNAs in the pRC/CMV expression vector were transfected into CHO cells, and G418 was used for selection of stably transfected cells. At near confluence, cells were washed with PBS and cultured in serum-free SFM4CHO medium (Thermo Scientific HyClone, Logan, UT) for four days before the SHBG-containing medium was harvested.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. KaufmanJMVermeulenA 2005 The decline of androgen levels in elderly men and its clinical and therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev 26 833 876

2. HaringRVolzkeHFelixSBSchipfSDorrM 2009 Prediction of metabolic syndrome by low serum testosterone levels in men: results from the study of health in Pomerania. Diabetes 58 2027 2031

3. KupelianVPageSTAraujoABTravisonTGBremnerWJ 2006 Low sex hormone-binding globulin, total testosterone, and symptomatic androgen deficiency are associated with development of the metabolic syndrome in nonobese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91 843 850

4. HaringRBaumeisterSEVölzkeHDorrMFelixSB 2011 Prospective Association of Low Total Testosterone Concentrations with an Adverse Lipid Profile and Increased Incident Dyslipidemia. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 18 86 96

5. TorklerSWallaschofskiHBaumeisterSEVölzkeHDörrM 2011 Inverse Association Between Total Testosterone Concentrations, Incident Hypertension, and Blood Pressure. Aging Male 14 176 182

6. VikanTSchirmerHNjolstadISvartbergJ 2010 Low testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin levels and high estradiol levels are independent predictors of type 2 diabetes in men. Eur J Endocrinol 162 747 754

7. YeapBBHydeZAlmeidaOPNormanPEChubbSA 2009 Lower testosterone levels predict incident stroke and transient ischemic attack in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94 2353 2359

8. SvartbergJvon MuhlenDMathiesenEJoakimsenOBonaaKH 2006 Low testosterone levels are associated with carotid atherosclerosis in men. J Intern Med 259 576 582

9. VikanTJohnsenSHSchirmerHNjolstadISvartbergJ 2009 Endogenous testosterone and the prospective association with carotid atherosclerosis in men: the Tromso study. Eur J Epidemiol 24 289 295

10. TivestenAMellstromDJutbergerHFagerbergBLernfeltB 2007 Low serum testosterone and high serum estradiol associate with lower extremity peripheral arterial disease in elderly men. The MrOS Study in Sweden. J Am Coll Cardiol 50 1070 1076

11. HaringRVolzkeHStevelingAKrebsAFelixSB 2010 Low serum testosterone levels are associated with increased risk of mortality in a population-based cohort of men aged 20-79. Eur Heart J 31 1494 1501

12. LaughlinGABarrett-ConnorEBergstromJ 2008 Low serum testosterone and mortality in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93 68 75

13. TivestenAVandenputLLabrieFKarlssonMKLjunggrenO 2009 Low serum testosterone and estradiol predict mortality in elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94 2482 2488

14. WuFCTajarAPyeSRSilmanAJFinnJD 2008 Hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis disruptions in older men are differentially linked to age and modifiable risk factors: the European Male Aging Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93 2737 2745

15. BogaertVTaesYKoningsPVan SteenKDe BacquerD 2008 Heritability of blood concentrations of sex-steroids in relation to body composition in young adult male siblings. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 69 129 135

16. BhasinSCunninghamGRHayesFJMatsumotoAMSnyderPJ 2010 Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95 2536 2559

17. WuFCTajarABeynonJMPyeSRSilmanAJ 2010 Identification of late-onset hypogonadism in middle-aged and elderly men. N Engl J Med 363 123 135

18. HigginsJPThompsonSGDeeksJJAltmanDG 2003 Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj 327 557 560

19. HaringRIttermannTVolzkeHKrebsAZygmuntM 2010 Prevalence, incidence and risk factors of testosterone deficiency in a population-based cohort of men: results from the study of health in Pomerania. Aging Male 13 247 257

20. TravisonTGAraujoABKupelianVO'DonnellABMcKinlayJB 2007 The relative contributions of aging, health, and lifestyle factors to serum testosterone decline in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92 549 555

21. BasariaSCovielloADTravisonTGStorerTWFarwellWR 2010 Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N Engl J Med 363 109 122

22. PinosTBarbosa-DesonglesAHurtadoASantamaria-MartinezAde TorresI 2009 Identification, characterization and expression of novel Sex Hormone Binding Globulin alternative first exons in the human prostate. BMC Mol Biol 10 59

23. AhnJSchumacherFRBerndtSIPfeifferRAlbanesD 2009 Quantitative trait loci predicting circulating sex steroid hormones in men from the NCI-Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (BPC3). Hum Mol Genet 18 3749 3757

24. ErikssonALLorentzonMMellstromDVandenputLSwansonC 2006 SHBG gene promoter polymorphisms in men are associated with serum sex hormone-binding globulin, androgen and androgen metabolite levels, and hip bone mineral density. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91 5029 5037

25. Perry JR, Weedon MN, Langenberg C, Jackson AU, Lyssenko V, et al. Genetic evidence that raised sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) levels reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes. Hum Mol Genet 19 535 544

26. HogeveenKNTalikkaMHammondGL 2001 Human sex hormone-binding globulin promoter activity is influenced by a (TAAAA)n repeat element within an Alu sequence. J Biol Chem 276 36383 36390

27. XitaNTsatsoulisAChatzikyriakidouAGeorgiouI 2003 Association of the (TAAAA)n repeat polymorphism in the sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) gene with polycystic ovary syndrome and relation to SHBG serum levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88 5976 5980

28. Martinez-GarayIJablonkaSSutajovaMSteuernagelPGalA 2002 A new gene family (FAM9) of low-copy repeats in Xp22.3 expressed exclusively in testis: implications for recombinations in this region. Genomics 80 259 267

29. OliveiraLMSeminaraSBBeranovaMHayesFJValkenburghSB 2001 The importance of autosomal genes in Kallmann syndrome: genotype-phenotype correlations and neuroendocrine characteristics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86 1532 1538

30. Pe'erIYelenskyRAltshulerDDalyMJ 2008 Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet Epidemiol 32 381 385

31. MazerNA 2009 A novel spreadsheet method for calculating the free serum concentrations of testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, estradiol, estrone and cortisol: with illustrative examples from male and female populations. Steroids 74 512 519

32. Sinha-HikimIArverSBeallGShenRGuerreroM 1998 The use of a sensitive equilibrium dialysis method for the measurement of free testosterone levels in healthy, cycling women and in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83 1312 1318

33. NiemiSMaentaustaOBoltonNJHammondGL 1988 Time-resolved immunofluorometric assay of sex-hormone binding globulin. Clin Chem 34 63 66

34. HammondGLLahteenmakiPL 1983 A versatile method for the determination of serum cortisol binding globulin and sex hormone binding globulin binding capacities. Clin Chim Acta 132 101 110

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Macroautophagy Is Regulated by the UPR–Mediator CHOP and Accentuates the Phenotype of SBMA MiceČlánek Dynamic Replacement of Histone H3 Variants Reprograms Epigenetic Marks in Early Mouse EmbryosČlánek Mutations in a Guanylate Cyclase GCY-35/GCY-36 Modify Bardet-Biedl Syndrome–Associated Phenotypes in

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2011 Číslo 10- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Transcriptional Robustness Complements Nonsense-Mediated Decay in Humans

- Identification, Replication, and Fine-Mapping of Loci Associated with Adult Height in Individuals of African Ancestry

- Genetic Determinants of Serum Testosterone Concentrations in Men

- A One Base Pair Deletion in the Canine Gene Causes Exon Skipping and Late-Onset Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis in the Tibetan Terrier

- Three Structure-Selective Endonucleases Are Essential in the Absence of BLM Helicase in

- Identification of Widespread Ultra-Edited Human RNAs

- Multiple Wnts Redundantly Control Polarity Orientation in Epithelial Stem Cells

- The Bicoid Stability Factor Controls Polyadenylation and Expression of Specific Mitochondrial mRNAs in

- Transcriptome-Wide Binding Sites for Components of the Non-Poly(A) Termination Pathway: Nrd1, Nab3, and Sen1

- Macroautophagy Is Regulated by the UPR–Mediator CHOP and Accentuates the Phenotype of SBMA Mice

- Genetic Rearrangements Can Modify Chromatin Features at Epialleles

- Novel Function of as a Gap Gene during Spider Segmentation

- A Genome-Wide Screen for Interactions Reveals a New Locus on 4p15 Modifying the Effect of Waist-to-Hip Ratio on Total Cholesterol

- Comparative Genomic Analysis of Human Fungal Pathogens Causing Paracoccidioidomycosis

- Genetic Diversity in Cytokines Associated with Immune Variation and Resistance to Multiple Pathogens in a Natural Rodent Population

- Mutator Suppression and Escape from Replication Error–Induced Extinction in Yeast

- Dynamic Replacement of Histone H3 Variants Reprograms Epigenetic Marks in Early Mouse Embryos

- A Barcode Screen for Epigenetic Regulators Reveals a Role for the NuB4/HAT-B Histone Acetyltransferase Complex in Histone Turnover

- HIF–VEGF Pathways Are Critical for Chronic Otitis Media in and Mouse Mutants

- A Conserved Developmental Patterning Network Produces Quantitatively Different Output in Multiple Species of Drosophila

- Role of Exonic Variation in Chemokine Receptor Genes on AIDS: Association with Pneumocystis Pneumonia

- Whole-Exome Sequencing Identifies Homozygous Mutations in a Spastic Ataxia-Neuropathy Syndrome Linked to Mitochondrial -AAA Proteases

- Von Hippel-Lindau () Inactivation in Sporadic Clear Cell Renal Cancer: Associations with Germline Polymorphisms and Etiologic Risk Factors

- A Systems Biology Approach Reveals the Role of a Novel Methyltransferase in Response to Chemical Stress and Lipid Homeostasis

- Identification of Genomic Regions Associated with Phenotypic Variation between Dog Breeds using Selection Mapping

- Global Mapping of Cell Type–Specific Open Chromatin by FAIRE-seq Reveals the Regulatory Role of the NFI Family in Adipocyte Differentiation

- Natural Selection Affects Multiple Aspects of Genetic Variation at Putatively Neutral Sites across the Human Genome

- MicroRNA Expression and Regulation in Human, Chimpanzee, and Macaque Brains

- An Adaptive Allelic Series Featuring Complex Gene Rearrangements

- Feed-Forward Microprocessing and Splicing Activities at a MicroRNA–Containing Intron

- Developmental Stability: A Major Role for in

- A Phenomics-Based Strategy Identifies Loci on , , and Associated with Metabolic Syndrome Phenotype Domains

- Association of , , , , and with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Small RNAs Prevent Transcription-Coupled Loss of Histone H3 Lysine 9 Methylation in

- Successive Increases in the Resistance of to Viral Infection through a Transposon Insertion Followed by a Duplication

- Mutations in a Guanylate Cyclase GCY-35/GCY-36 Modify Bardet-Biedl Syndrome–Associated Phenotypes in

- The Glycobiome Reveals Mechanisms of Pentose and Hexose Co-Utilization in Bacteria

- Insights into Hox Protein Function from a Large Scale Combinatorial Analysis of Protein Domains

- Mutations Cause Seckel and Jawad Syndromes

- Zelda Binding in the Early Embryo Marks Regions Subsequently Activated at the Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition

- Temporal Coordination of Gene Networks by Zelda in the Early Embryo

- Genetic Interaction between MTMR2 and FIG4 Phospholipid Phosphatases Involved in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathies

- Oxr1 Is Essential for Protection against Oxidative Stress-Induced Neurodegeneration

- Transforming Growth Factor β Receptor Type 1 Is Essential for Female Reproductive Tract Integrity and Function

- Positional Cloning of a Type 2 Diabetes Quantitative Trait Locus; , a Negative Regulator of Insulin Secretion

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- The Glycobiome Reveals Mechanisms of Pentose and Hexose Co-Utilization in Bacteria

- Global Mapping of Cell Type–Specific Open Chromatin by FAIRE-seq Reveals the Regulatory Role of the NFI Family in Adipocyte Differentiation

- Genetic Determinants of Serum Testosterone Concentrations in Men

- MicroRNA Expression and Regulation in Human, Chimpanzee, and Macaque Brains

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy