-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Comparative Anatomy of Chromosomal Domains with Imprinted and Non-Imprinted Allele-Specific DNA Methylation

Allele-specific DNA methylation (ASM) is well studied in imprinted domains, but this type of epigenetic asymmetry is actually found more commonly at non-imprinted loci, where the ASM is dictated not by parent-of-origin but instead by the local haplotype. We identified loci with strong ASM in human tissues from methylation-sensitive SNP array data. Two index regions (bisulfite PCR amplicons), one between the C3orf27 and RPN1 genes in chromosome band 3q21 and the other near the VTRNA2-1 vault RNA in band 5q31, proved to be new examples of imprinted DMRs (maternal alleles methylated) while a third, between STEAP3 and C2orf76 in chromosome band 2q14, showed non-imprinted haplotype-dependent ASM. Using long-read bisulfite sequencing (bis-seq) in 8 human tissues we found that in all 3 domains the ASM is restricted to single differentially methylated regions (DMRs), each less than 2kb. The ASM in the C3orf27-RPN1 intergenic region was placenta-specific and associated with allele-specific expression of a long non-coding RNA. Strikingly, the discrete DMRs in all 3 regions overlap with binding sites for the insulator protein CTCF, which we found selectively bound to the unmethylated allele of the STEAP3-C2orf76 DMR. Methylation mapping in two additional genes with non-imprinted haplotype-dependent ASM, ELK3 and CYP2A7, showed that the CYP2A7 DMR also overlaps a CTCF site. Thus, two features of imprinted domains, highly localized DMRs and allele-specific insulator occupancy by CTCF, can also be found in chromosomal domains with non-imprinted ASM. Arguing for biological importance, our analysis of published whole genome bis-seq data from hES cells revealed multiple genome-wide association study (GWAS) peaks near CTCF binding sites with ASM.

Published in the journal: Comparative Anatomy of Chromosomal Domains with Imprinted and Non-Imprinted Allele-Specific DNA Methylation. PLoS Genet 9(8): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003622

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003622Summary

Allele-specific DNA methylation (ASM) is well studied in imprinted domains, but this type of epigenetic asymmetry is actually found more commonly at non-imprinted loci, where the ASM is dictated not by parent-of-origin but instead by the local haplotype. We identified loci with strong ASM in human tissues from methylation-sensitive SNP array data. Two index regions (bisulfite PCR amplicons), one between the C3orf27 and RPN1 genes in chromosome band 3q21 and the other near the VTRNA2-1 vault RNA in band 5q31, proved to be new examples of imprinted DMRs (maternal alleles methylated) while a third, between STEAP3 and C2orf76 in chromosome band 2q14, showed non-imprinted haplotype-dependent ASM. Using long-read bisulfite sequencing (bis-seq) in 8 human tissues we found that in all 3 domains the ASM is restricted to single differentially methylated regions (DMRs), each less than 2kb. The ASM in the C3orf27-RPN1 intergenic region was placenta-specific and associated with allele-specific expression of a long non-coding RNA. Strikingly, the discrete DMRs in all 3 regions overlap with binding sites for the insulator protein CTCF, which we found selectively bound to the unmethylated allele of the STEAP3-C2orf76 DMR. Methylation mapping in two additional genes with non-imprinted haplotype-dependent ASM, ELK3 and CYP2A7, showed that the CYP2A7 DMR also overlaps a CTCF site. Thus, two features of imprinted domains, highly localized DMRs and allele-specific insulator occupancy by CTCF, can also be found in chromosomal domains with non-imprinted ASM. Arguing for biological importance, our analysis of published whole genome bis-seq data from hES cells revealed multiple genome-wide association study (GWAS) peaks near CTCF binding sites with ASM.

Introduction

Evidence from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and cross-species comparisons suggests that many inter-individual phenotypic differences result from genetic variants in non-coding DNA sequences. Thus a major challenge in the post-genomic era is to define the mechanisms by which non-coding sequence polymorphisms and haplotypes result in differences in biological phenotypes. One hypothesis comes from recent work that has revealed strong cis-acting influences of simple nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and the haplotypes in which these SNPs are embedded, on epigenetic marks, leading to allele-specific DNA methylation (ASM) and allele-specific chromatin structure [1]. Historically, ASM has been most intensively studied in the context of genomic imprinting - a parent-of-origin dependent phenomenon that affects about 80 human genes. Mechanistic principles that have emerged from studying imprinted domains include the presence of discrete small (one to several kb) DNA intervals, called differentially methylated regions (DMRs), which show strong parent-of-origin dependent asymmetry in CpG methylation between the two alleles and which control the allele-specific expression (ASE) of one or more nearby genes in cis, in some cases via methylation-sensitive binding of the insulator protein CTCF [2]–[6].

While genomic imprinting is a potent mode of gene regulation, it affects fewer loci than the more recently recognized phenomenon of non-imprinted haplotype-dependent ASM. Mapping haplotype-dependent ASM, and related phenomena such as ASE, will be useful for interpreting the biological meaning of statistical peaks from GWAS (and non-coding variants from post-GWAS exome sequencing studies), as bona fide regulatory sequence variants can reveal their presence by conferring a measurable epigenetic asymmetry between the two alleles. However as yet there have not been many insights to the molecular mechanisms underlying non-imprinted ASM. This situation raises an interesting question – could any principles from studies of genomic imprinting also be relevant for understanding haplotype-dependent, non-imprinted, ASM? To begin to address this issue, and to identify and characterize new examples of loci with imprinted and non-imprinted ASM, we have searched for “index regions” in the human genome showing strong and highly recurrent ASM and used these locations as starting points for intensive local mapping of DNA methylation patterns in multiple human tissues. Here we describe these data for new examples of loci with imprinted and non-imprinted ASM, which reveal epigenomic features that are shared between these two allele-specific phenomena.

Results

Index regions with ASM identified by MSNP

The MSNP procedure, an adaptation of SNP arrays for detecting ASM, was described in our initial report of haplotype-dependent ASM in human tissues [7]. As a starting point for comparing the structures of chromosomal domains with imprinted (parent-of-origin dependent) versus non-imprinted (haplotype dependent) ASM we applied higher resolution MSNP to several human tissue types from multiple individuals and identified 4 additional SNP-tagged StyI or NspI restriction fragments with CpG dinucleotides in HpaII sites that showed strongly asymmetrical methylation between the two alleles in multiple heterozygous samples (examples in Figure S1). These index fragments are tagged by SNPs rs1530562 between the STEAP3 and C2orf76 genes (chromosome band 2q14), rs2346019 near the VTRNA2-1 vault family small RNA gene (5q31.1), rs2811488 between the C3orf27 and RPN1 genes (3q21), and rs2302902 in the ELK3 gene (12q23.1). We used Sanger bisulfite sequencing (bis-seq) of amplicons containing these SNPs and multiple (non-polymorphic) adjacent CpG dinucleotides to confirm ASM in heterozygous individuals in a panel of primary tissues chosen for relevance to complex diseases and representation of multiple cell lineages: peripheral blood (PBL), whole fetal and adult lung and adult bronchial epithelial cells, adult liver, adult brain (cerebral cortical grey matter), placenta (chorionic villi taken from near the fetal surface), human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC), and sperm. These analyses showed that the ASM was reproducible for all 4 index fragments, with the allelic asymmetry in methylation affecting multiple (non-polymorphic) CpGs around and including the index HpaII sites (Fig. 1 and Figs. S2, S3, S4). Among these 4 regions, moderate ASM was observed in the ELK3 gene, while the other index regions showed stronger allelic asymmetries. ASM was seen in two or more tissues for each of the index regions except the C3orf27-RPN1 region, for which the index amplicon revealed highly tissue-specific ASM, which was very strong in the large majority of human placentas examined (33/34 cases; all tested using tissue from the fetal side of the organ, consisting of the free chorionic villi without maternal decidua; Table 1), but absent in the other tissues tested (Fig. 1, Table 1 and Figure S3).

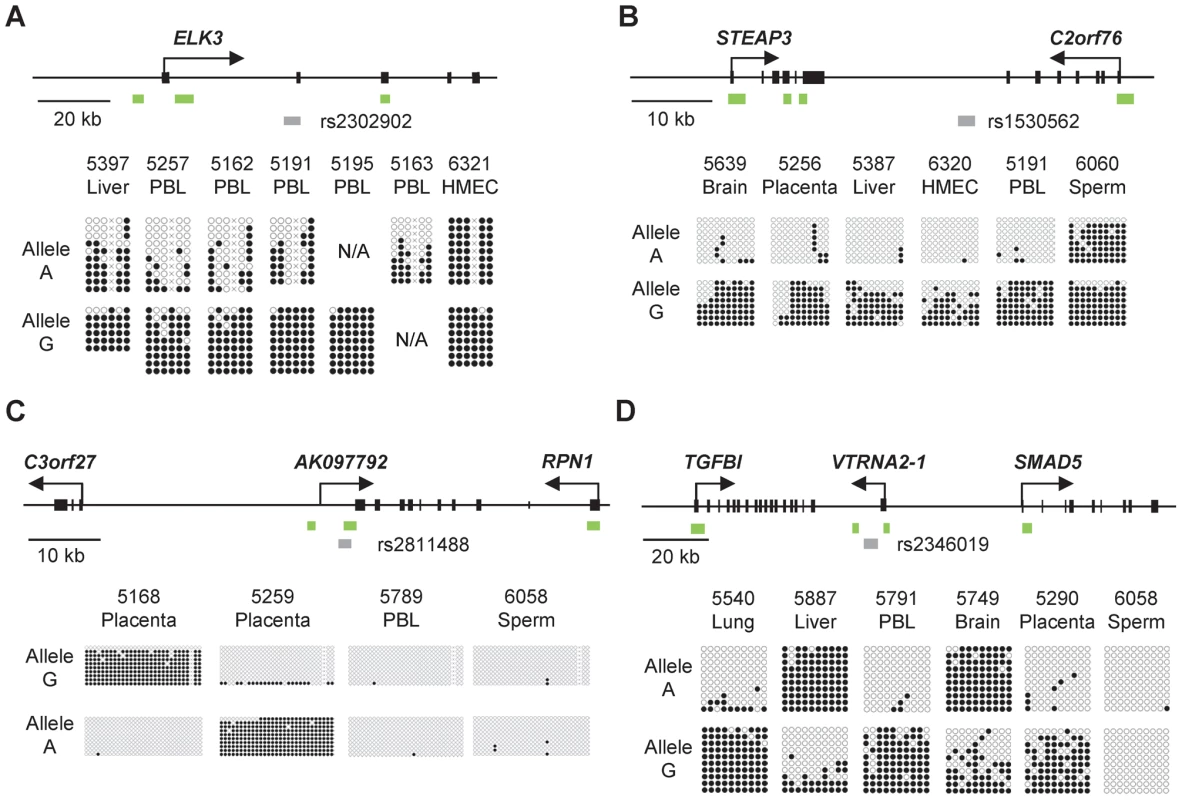

Fig. 1. Bis-seq showing strong ASM in the ELK3, STEAP3-C2orf76, C3orf27-RPN1, and VTRNA2-1 index regions.

A, Gene map and bis-seq of the index amplicon containing SNP rs2302902 in the first intron of the ELK3 gene. The strong asymmetry in CpG methylation, with the G allele consistently hypermethylated in the PBL samples, indicates haplotype-dependent non-imprinted ASM (additional data in Table 1; haplotype map in Figure S5). There is some tissue-specificity, with biallelic hypermethylation in the HMEC sample. The grey (lower) bars indicate the index amplicons for initial bis-seq, each tagged by the index SNP that showed recurrent ASM in the MSNP data. The green bars indicate CGIs and the black rectangles are exons. The X's indicate polymorphic CpG sites. B, Gene map and bis-seq of the index amplicon containing SNP rs1530562, between the STEAP3 and C2orf76 genes in chromosome band 2q14, showing strong ASM with the G allele consistently hypermethylated in multiple tissues consistent with haplotype-dependent non-imprinted ASM, but with biallelic hypermethylation in sperm DNA (additional data in Table 1). C, Gene map and bis-seq of the index amplicon containing SNP rs2811488 located downstream of the last exon of the RPN1 gene in chromosome band 3q21, showing strong ASM in placenta, with the G allele or A allele hypermethylated, depending on parent-of-origin, as proven in Figure 2. For this imprinted DMR the ASM is highly tissue-specific, being seen in placenta but not in PBL, liver, lung, brain, HMEC or sperm (additional data in Table 1 and Figure S2). D, Gene map and bilsufite sequencing of the index amplicon containing SNP rs2346019 downstream of the VTRNA2-1 vault-family RNA, located in chromosome band 5q31. Strong ASM is observed in multiple tissues with the A allele or G allele methylated, consistent with imprinting, which is proven by the data in Figure 2. Tab. 1. Summary of the 5 DMRs characterized in this report.

Total number of samples with ASM/number of heterozygous samples tested, including Sanger and 454 long read bis-seq and HpaII pre-digestion/PCR/RFLP assays. ASM in the STEAP3-C2orf76 and ELK3 regions is non-imprinted and haplotype dependent

We next asked whether the ASM in each of these 4 regions was due to parental imprinting or, alternatively, to cis-acting effects of the local DNA sequence or haplotype. Sanger and bis-seq in a total of 198 and 129 individuals with all 3 possible genotypes, plus HpaII-pre-digestion/PCR/RFLP assays [7] in 76 and 30 heterozygotes, respectively, showed unequivocally that ASM both in the STEAP3-C2orf76 intergenic region and in the ELK3 intragenic region is haplotype-dependent: the simple genotypes at nearby SNPs consistently predicted the methylation status of 10 and 6 clustered CpGs, respectively, in these two index amplicons (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The ASM at both loci showed some tissue-specificity: for the STEAP3-C2orf76 intergenic amplicon we found strong ASM in multiple tissues including brain, placenta, liver, HMEC, and PBL; with sperm DNA showing biallelic hypermethylation, while for the ELK3 intergenic amplicon we found strong ASM in PBL and weak ASM in liver, with HMEC DNA showing biallelic hypermethylation (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

ASM in the VTRNA2-1 and C3orf27-RPN1 regions is due to parental imprinting

In contrast to the results for the STEAP3-C2orf76 and ELK3 index regions, Sanger and bis-seq in 192 and 325 individuals with all 3 possible genotypes and restriction pre-digestion/PCR/RFLP assays in 70 and 75 heterozygotes for the C3orf27-RPN1 and VTRNA2 index regions respectively showed that either allele could be relatively hypermethylated with the genotype of the index SNP having no predictive value - a situation suggestive of imprinting, in which methylation is dictated by parent-of-origin, not by haplotype (Table 1). To test for bona fide parental imprinting at these two loci we analyzed trios of maternal and paternal PBL and placenta DNA. In each of 13 trios informative for the C3orf27-RPN1 index SNP and in each of 10 trios informative for the VTRNA2-1 index SNP we found relative hypermethylation of the maternal allele in the placental DNA (p = 0.000311 for parental imprinting of the C3orf27-RPN1 locus and p = 0.001565 for the VTRNA2 locus, Chi-Square test; Fig. 2). While this manuscript was in preparation Treppendahl et al. reported ASM at VTRNA2-1 in human hematopoietic cells [8] but imprinting was not tested in that study. Imprinting has not been previously reported in the C3orf27-RPN1 region. As noted above, in the RPN1 downstream DMR the ASM was restricted to placenta DNA samples, and in both loci sperm DNA showed biallelic hypomethylation, suggesting that the methylation imprint is acquired in the oocyte or early post-zygotically. The parent-of-origin dependence of the ASM in this region indicates that at least the initial “signal” for the imprint must be gametic, not somatic. However, we do not yet know the pattern of methylation in oocytes, so whether the densely methylated pattern of the maternal allele is established in the oocyte, or acquired early post-zygotically, remains to be determined.

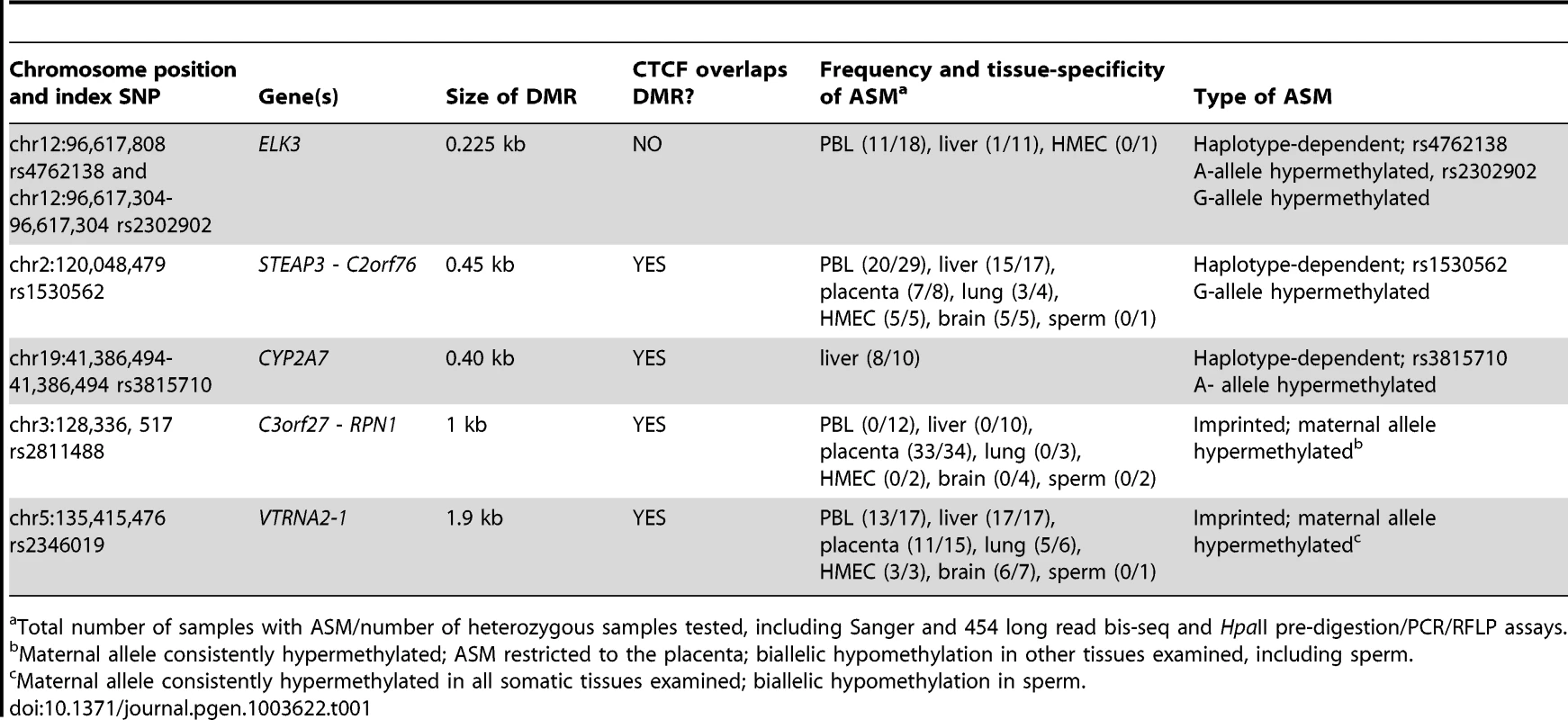

Fig. 2. ASM downstream of the RPN1 gene and in the VTRNA2-1 gene is due to genomic imprinting with hypermethylation of the maternal allele.

Trios consisting of matched parents (PBL) and offspring (placental chorionic villi from the fetal surface) were analyzed for ASM to determine the parental origin of the hypermethylated and hypomethylated alleles in the C3orf27-RPN1 and VTRNA2-1 index regions. A, HpaII-predigestion/PCR/RFLP assay for ASM at non-polymorphic HpaII sites in an amplicon including SNP rs12487604 (located immediately downstream of RPN1) which creates a BtsI restriction site. Undigested genomic DNA and genomic DNA pre-digested with the methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme HpaII were amplified by PCR and then digested with BtsI. In the samples pre-digested with HpaII (+) one allele drops out, indicating hypomethylation. A homozygous case for each allele is shown, as well as four heterozygotes; two cases show T-allele hypermethylation and two show A-allele hypermethylation. B, Trios analyzed by this assay showing parental imprinting of the index region downstream of RPN1. A total of 13 informative trios (two shown) were analyzed and each showed hypermethylation of the maternally-derived allele in the placenta (p<0.00311). C, Examples of bis-seq of trios for the index amplicon including SNP rs2346019 in the VTRNA2-1 locus. The hypermethylated allele was found to be maternally derived in each of 10 informative trios (p<0.001565). By analogy with other imprinted genes [9], [10], the placenta-specific methylation imprinting of the RPN1 3′ region could be relevant to placental and fetal growth, so for planning future studies it is relevant to ask whether imprinting of this region also occurs in mice. The mouse genome shows conservation of synteny with regard to the linkage and order of the Rab7-Rpn1-Gata2 genes, but an orthologue of human C3orf27 (which is located between the human RPN1 and GATA2 genes) is not present in this region of the mouse genome. Moreover, the full-fledged CGI at the 3′ end of the RPN1 gene in humans is not present in this position of the mouse Rpn1 gene. Despite this lack of conservation of the CGI, and indeed the lack of conservation of the DNA sequence in this region, we tested for ASM in a CG-rich sequence located immediately downstream of Rpn1 in the mouse, in a position analogous to the human DMR. Using extraembryonic tissues (yolk sac and placenta) from reciprocal inter-strain mouse crosses we found that CpG methylation in the orthologous region is somewhat allele-specific, but with much less allelic asymmetry than the human locus (Figure S5A). The methylation patterns in the mouse yolk sac and placenta are most simply explained by weak parental imprinting superimposed on a cis-acting haplotype effect. After accounting for the cis-effect (CAST allele more methylated than B6 allele), the direction of the weak imprinting matches that in humans, with the maternal allele relatively hypermethylated (Figure S5B). The main finding from this analysis - that the parental imprint is much weaker in mice - suggests that non-conserved, human-specific, sequences are important for establishing or stabilizing the methylation imprint in this chromosomal region.

A well-studied group of growth-regulating genes in fact show conserved imprinting in the placentas of humans and mice [10], [11], but the poor conservation of imprinting of the RPN1 downstream region is not surprising, as gene regulation in the placenta is known to be rapidly and continually evolving in mammals along with changes in placental anatomy [12], [13]. Given that genomic imprinting appears to have evolved in mammals with placentation, a prediction is that the C3orf27-RPN1 intergenic DMR, and its associated RNA transcripts, may play a “human-specific” role in placental growth and development that is not conserved in mice. Overall, these data add two new loci to the current list of approximately 80 human genes with robust methylation imprinting characterized to date.

Discrete DMRs are found both in imprinted domains and in chromosomal regions with non-imprinted haplotype-dependent ASM

To compare the structures of chromosomal domains with imprinted versus non-imprinted ASM we used high throughput bisulfite PCR (Fluidigm AccessArray) with sample bar-coding, followed long-read 454 Pyrosequencing of amplicons bracketing 3 of the index regions; two with imprinted ASM (VTRNA2-1 and C3orf27-RPN1) and one with non-imprinted/haplotype dependent ASM (STEAP3-C2orf76). To maximize the information from this approach we designed the amplicons to contain SNPs with heterozygosities ≥0.2 and to span DNA segments containing ≥4 CpG dinucleotides. For VTRNA2-1 region, 6 additional amplicons covering 3 CpGs were included. The long-read sequencing platform was optimal for analyzing ASM as it allowed us to capture the CpG methylation pattern and SNP genotype in each read, with no ambiguity as to phase, while the primer bar-coding strategy facilitated the analysis of a large series of individuals, with DNA samples from various tissue types including placenta, PBL, lung, liver, brain, heart, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN).

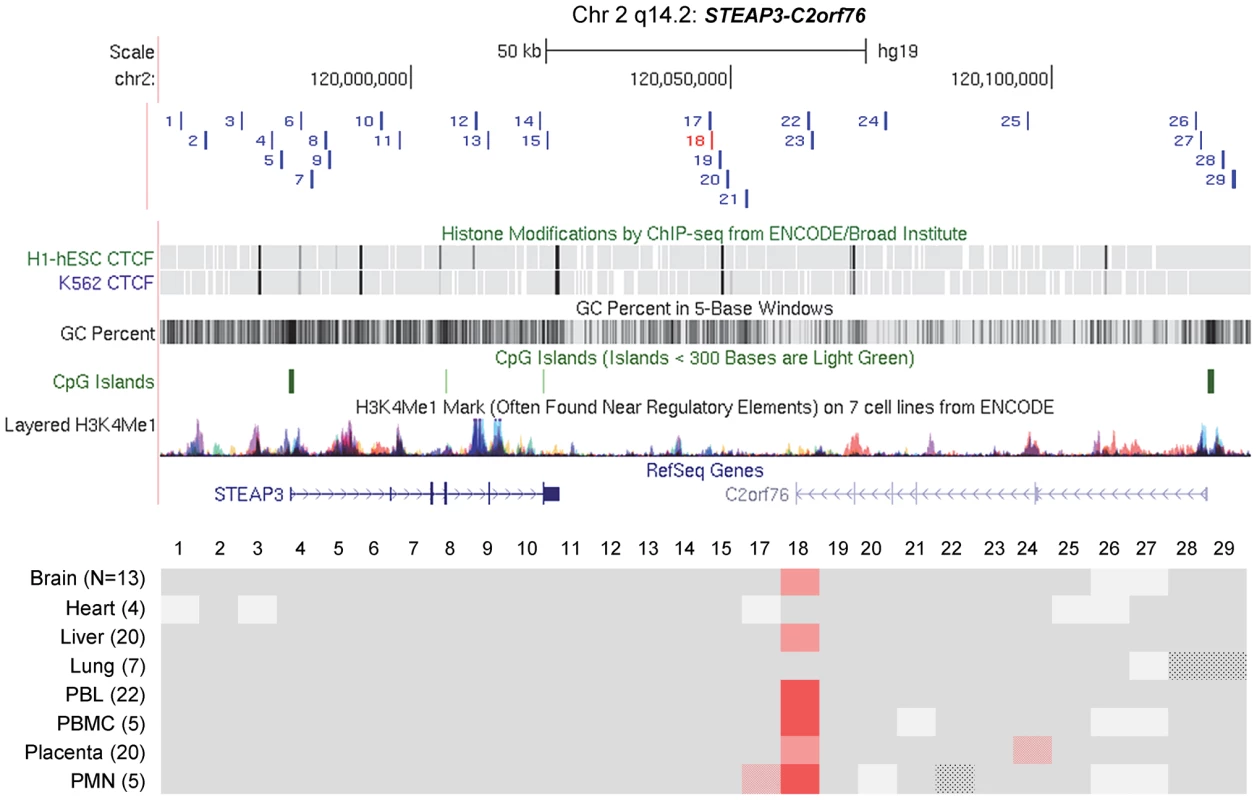

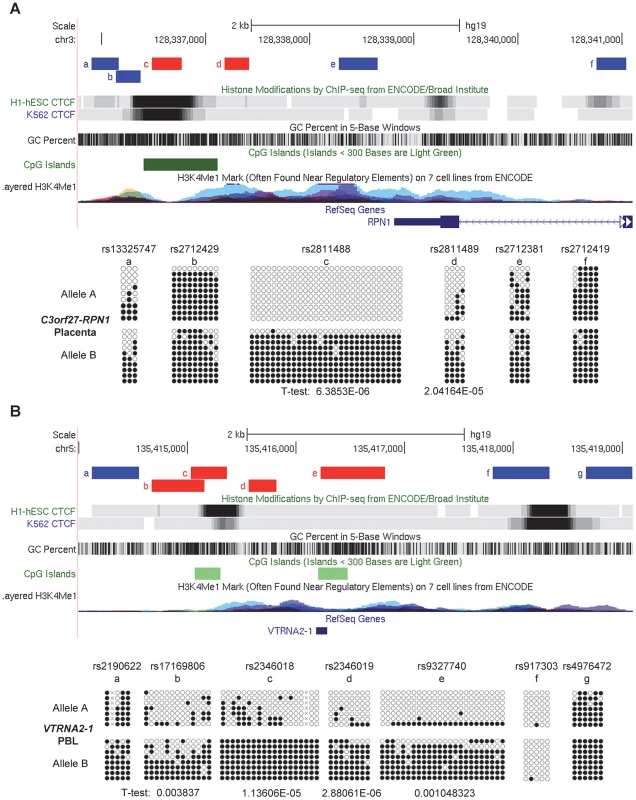

The resulting dataset for the 3 chromosomal regions consisted of 104 amplicons analyzed in 96 biological samples, totaling 354 Mb of bis-seq, with a mean depth of 90 sequences per sample per amplicon and with a mean read length of 304 bp. Also included are data from >3500 full-length Sanger bis-seq reads of from 300 to 500 bp, which we carried out on multiple amplicons and tissue samples to supplement and verify the 454 data. Our strategy allowed us to score net and allele-specific methylation for each informative amplicon over multiple CpGs with complete genetic phase information in each read. The data are summarized by color-coding for ASM (difference in percent methylation of allele A versus allele B averaged for heterozygous samples by tissue) in Figure 3 and Figure 4. These “ASM heat maps” illustrate the amplicons for each chromosomal region, aligned to UCSC genome browser tracks [14], showing CpG islands (CGIs), histone modifications and CTCF binding sites.

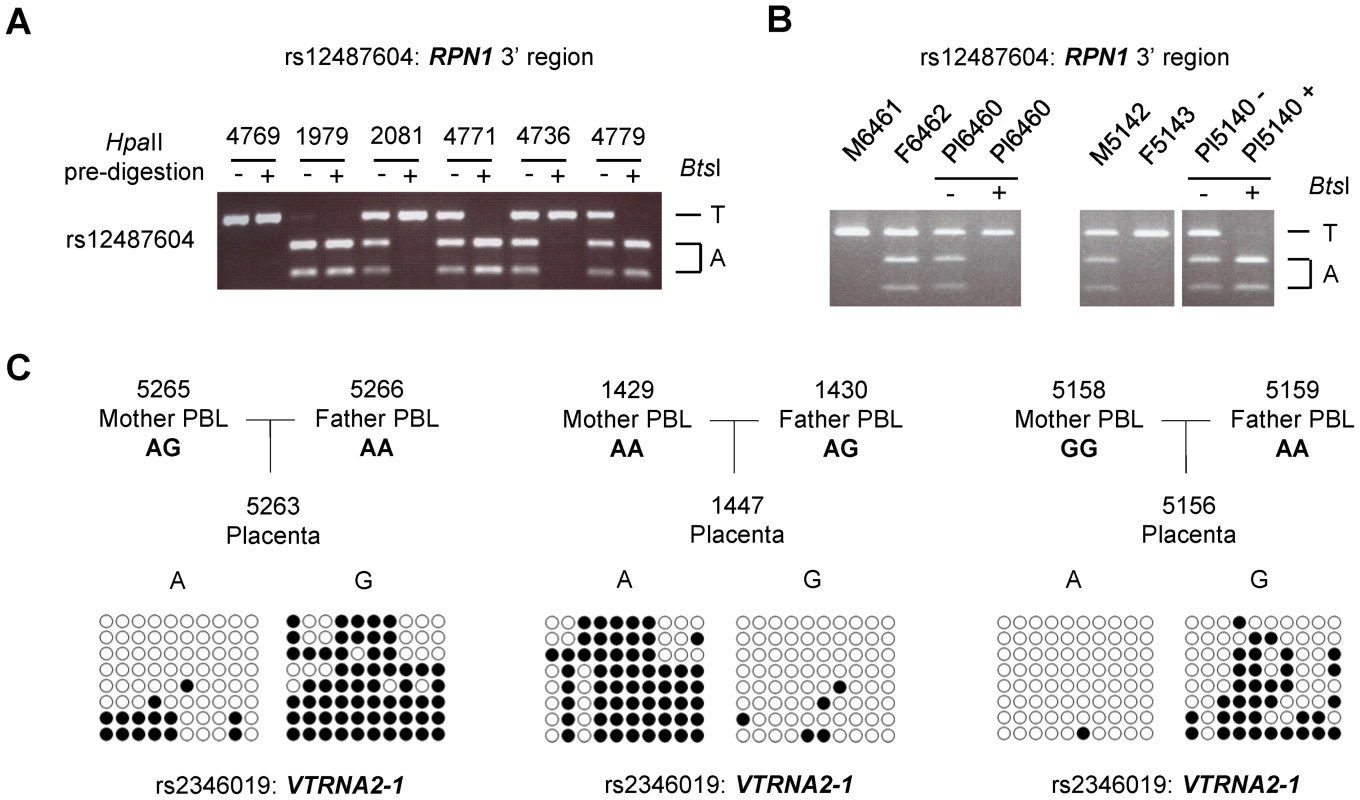

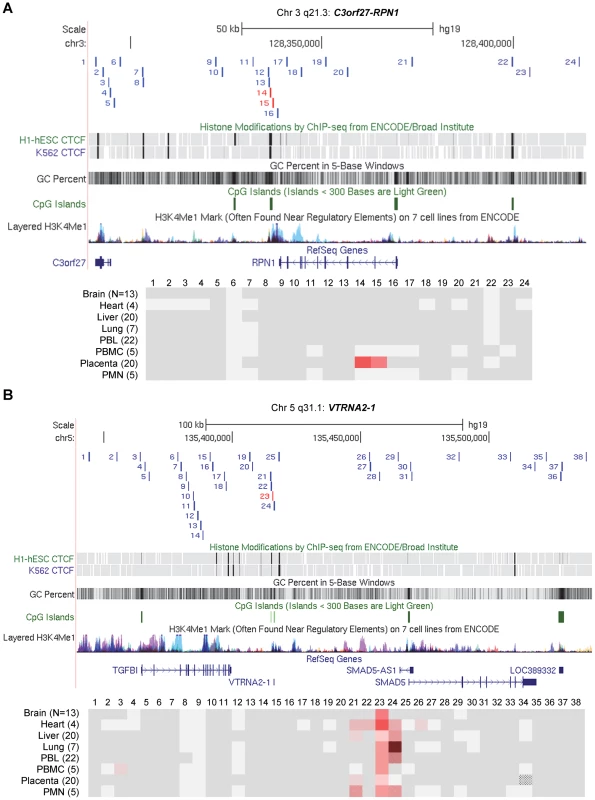

Fig. 3. Long-range methylation mapping of the two imprinted regions, C3orf27-RPN1 and VTRNA2-1, in 8 types of human tissues, shows small discrete DMRs.

Maps from the UCSC genome browser (top) and ASM heat maps (bottom) derived from long read bis-seq in the gene regions. In the genome browser map, the index amplicons that provided the starting points for the mapping are in red, and CTCF binding sites, GC percentage, CGIs and H3K4me1 activating mark intensities are shown. In the heat maps, light grey shading indicates homozygosity in all samples, and dark grey indicates heterozygosity in one or more sample with no evidence of ASM. Shades of red indicate ASM, with the intensity scale indicating the absolute value of the difference in fractional methylation of the two alleles from 0.30 to 1. These data are averaged over all heterozygous samples for a given tissue. The red stippled cells indicate tissues with a greater than 0.30 average difference in fractional methylation of the two alleles but with only one heterozygous sample or with less than half of the samples showing significant ASM (p≤0.05, using the t-test). The grey stippled cell indicates an amplicon with insufficient read depth (<10). The number of samples subjected to bis-seq for each tissue is indicated in the parentheses. A, The C3orf27-RPN1 region shows a single discrete epicenter of ASM (DMR) which overlaps with the initial index fragment discovered using MSNP data. ASM in this domain is only present in placenta. B, The VTRNA2-1 region shows a single discrete epicenter of ASM (DMR) which overlaps with the initial index fragment discovered using MSNP data. ASM in this domain is present in all 8 tissues. However, ASM with less robust evidence and less consistency between samples (stippled red cells) was found in several immediate flanking amplicons (amplicons 21, 22, 24, 26). Fig. 4. Long-range methylation mapping of the non-imprinted STEAP3-C2orf76 region in 8 types of human tissues shows that small discrete DMRs can be present in loci with non-imprinted ASM.

A map from the UCSC genome browser and an ASM heat map derived from long read bis-seq in the STEAP3-C2orf76 region. In the genome browser map, the index amplicon that provided the starting point for the mapping is in red, and CTCF binding sites, GC percentage, CGIs and H3K4me1 activating mark intensities are shown. The presence and strength of ASM is color-coded as in Figure 3. This region shows a single discrete epicenter of ASM (DMR) which overlaps with the initial index fragment discovered using MSNP data. ASM in this domain is present in 6 tissues. The red stippled cells indicate tissues with a greater than 0.30 average difference in fractional methylation of the two alleles but with only one heterozygous sample or with less than half of the samples showing significant ASM (p≤0.05, using the t-test). The grey stippled cells indicate amplicons with insufficient read depth (<10). The most striking finding from this long-range analysis, and from additional intensive short-range mapping by Sanger bis-seq (Figs. 5 and 6A), is the discrete nature of all three DMRs; for all three regions, two with imprinted ASM and one with non-imprinted haplotype-dependent ASM, the allelic asymmetry in DNA methylation is restricted to one or two adjacent amplicons, with all three DMRs being less than 2 kb in length (Figs. 5 and 6 and Table 1). Within each of the regions examined, the flanking DNA outside of the DMRs showed varying levels of net CpG methylation, without asymmetry between the two alleles. Our mapping does not rule out additional DMRs farther away, but for the STEAP3-C2orf76 region, which shows haplotype-dependent ASM, any DMRs farther away would be in separate haplotype blocks and therefore be independently regulated domains. We additionally carried out short-range mapping of ASM around the ELK3 intragenic index fragment, which showed that it too is discrete and <2 kb in size (Figure S6).

Fig. 5. Local mapping of the imprinted C3orf27-RPN1 and VTRNA2-1 DMRs shows precise overlap with CTCF binding sites.

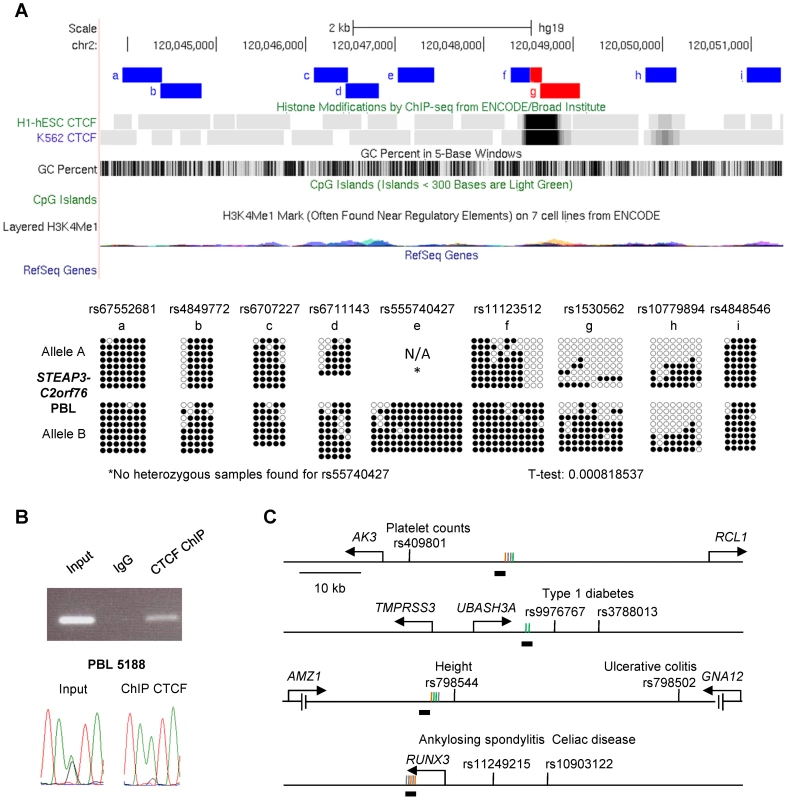

A, Bis-seq of heterozygous placenta samples for amplicons immediately downstream of the RPN1 gene shows ASM localized to a discrete region of about 1 kb in length (chr3: 128,336,485–128,337,414) spanning a strong CTCF binding site and a CGI. Amplicons with ASM are colored red. B, Bis-seq of heterozygous PBL samples for amplicons surrounding the VTRNA2-1 vault RNA gene shows ASM localized to a 1.9 kb region (chr5: 135,414,670–135,416,821) spanning one CTCF binding site, two small CGIs, and the VTRNA2-1 RNA gene, while another CTCF binding site upstream is hypomethylated. ASM for both genes was evaluated visually and by T-tests on the percent methylation of individual clones, comparing the sets of clones for the two alleles. Fig. 6. The STEAP3-C2orf76 DMR with non-imprinted ASM overlaps a CTCF site, with CTCF preferentially bound to the unmethylated allele, and cross-indexing of ASM-associated CTCF sites with GWAS peaks provides evidence for regulatory haplotypes.

A, Bis-seq of the STEAP3 - C2orf76 intergenic DMR in heterozygous PBL samples shows localization of ASM to a discrete region about 450 bp in length (chr2: 120,048,634–120,049,081) spanning the strong CTCF binding site. *No heterozygous samples were found for rs55740427. B, PCR of the STEAP3 - C2orf76 intergenic DMR performed on non-immunoprecipitated input DNA, negative control IgG IP DNA and CTCF ChIP DNA. As expected, the non-immunoprecipitated input sample results in a strong amplification while the negative control IgG IP sample shows no amplification. The observed amplification in the CTCF immunoprecipitated sample demonstrates CTCF binding at this region. Direct sequencing of end-point PCR products shows that the non-immunoprecipitated input DNA is heterozygous at the index SNP rs1530562 while the CTCF ChIP sample shows a strong enrichment for the A-allele indicating that CTCF is bound selectively to this (hypomethylated) allele. C, Maps of 4 representative haplotype blocks containing both a CTCF binding site with at least two ASM CpG sites (as defined by Chen et al. [15]) within a 1 kb window and SNPs associated with important human traits or disease susceptibility from GWAS (supra-threshold or strong sub-threshold peaks, all p<10−6; http://www.genome.gov/gwastudies). The relevant traits or diseases are indicated next to each SNP. The CpG sites that were analyzed for ASM (vertical lines) and located near the CTCF binding sites (horizontal black bars below the lines) are color-coded as orange for ASM sites that do not overlap with a CpG SNP, green for CpG SNP ASM sites, gray for non ASM sites. See also Table S4. Both imprinted and non-imprinted DMRs can overlap precisely with CTCF binding sites

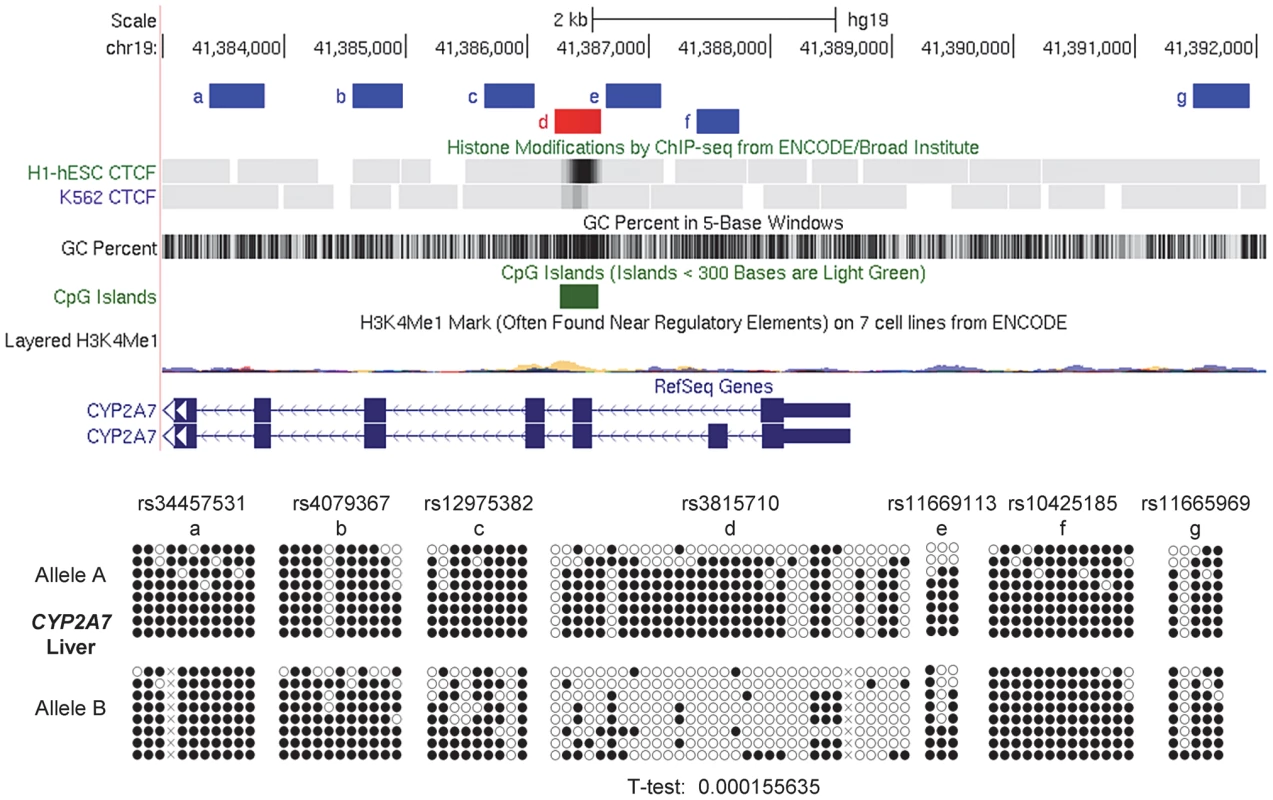

Alignment of our methylation sequencing data with ChIP-Seq data from ENCODE and related projects, as displayed on the UCSC genome browser [14], showed that for both of the 2 imprinted domains, and for the non-imprinted STEAP3-C2orf76 intergenic region, though not for the ELK3 intragenic DMR, the DMRs with ASM overlapped precisely with empirically determined CTCF binding sites (Figs. 5, 6A and Figure S6). To ask whether there are additional examples of small discrete DMRs with strong and recurrent haplotype-dependent ASM that overlap with CTCF binding sites, we returned to an interesting locus with haplotype-dependent ASM and ASE that we had characterized in our initial report on this phenomenon [7], namely, the CYP2* gene cluster in chromosome band 19q13.2. As shown in Figure 7, the intragenic DMR in CYP2A7, tagged by SNP rs3815710, in fact shows discrete borders and precise co-localization with a CTCF binding site. Another DMR in this large gene cluster, tagged by SNP rs3844442 and located between 2 CYP2* pseudogenes [7], overlaps with a weaker CTCF binding site. Maps of each of these regions with haplotype-dependent ASM are shown aligned to haplotype blocks in Figure S7.

Fig. 7. Local mapping of ASM in the CYP2A7 gene shows a discrete DMR that precisely overlaps a CTCF binding site.

Bis-seq of heterozygous liver samples for multiple CYP2A7 amplicons shows ASM localized to a roughly 400 bp region (chr19: 41,386,227–41,386,613) spanning a CGI and a CTCF binding site in exon 2. ASM was evaluated visually and by a T-test on the percent methylation of individual clones, comparing the sets of clones for the two alleles. Methylation-dependent binding of CTCF to the STEAP3-C2orf76 DMR

To test directly for allele specific binding of CTCF to the STEAP3-C2orf76 DMR, we carried out CTCF ChiP on a freshly obtained blood sample from a heterozygous individual that had shown strong sequence dependent ASM by previous bis-seq. By comparison with the IgG control IP, end-point PCR amplification of a region of the STEAP3-C2orf76 DMR covering the index SNP rs1530562 confirmed CTCF binding to this region, and Sanger sequencing of the PCR product confirmed that only the hypomethylated allele was present in the CTCF enriched product, while both alleles were observed in the PCR product from the input non-immunoprecipitated DNA (Fig. 6B). Thus, CTCF binds specifically to the hypomethylated allele of the STEAP3-C2orf76 intergenic DMR.

Analysis of whole genome bis-seq data shows a non-random association of ASM sites with CTCF site locations and overlap with GWAS peaks

To test for a possible genome-wide non-random association of ASM with CTCF sites, we used previously published ASM site lists [15] from whole genome bis-seq of a single cell line, namely H1 hES cells [16]. Chen et al. [15] found 83,000 CpG sites with ASM, representing 14% of the total CpGs tested (a high percentage that partly reflects incomplete filtering-out of CpG SNPs in their analysis.) Based on their analysis, we first asked whether the ASM regions that we have described here were also detectable in H1 hES cells. The multi-tissue ASM we identified in the STEAP3-C2orf76 and VTRNA2-1 index regions was also present in the H1 hES cells, while the tissue-specific ASM found in C3orf27-RPN1 was not present. In addition, the ASM we found in the CYP2A7 region was not mirrored in H1 hES cells, consistent with tissue-specificity for liver.

We then looked for CTCF binding peaks in 500 bp windows centered on each of the CpGs tested by Chen et al. for ASM, using ChIP-seq data generated in H1 hES cells by the Broad/MGH, Hudson and UT-Austin ENCODE groups. We found 13,485 CTCF binding sites in the vicinity of the informative CpG sites. Most of these CTCF binding sites were in intragenic or intergenic regions (47%); fewer were in gene promoter regions (5%) or next to CGIs (7%). Overall, CTCF sites were far more frequently associated with unmethylated CpGs than with fully methylated, partially methylated or ASM CpGs (Figure S8). However, when considering only CpG sites in gene promoter regions (within 1 kb upstream and downstream of transcription starting sites), we find a 1.7-fold increase in the percent of ASM CpGs located near CTCF binding sites (that is, in a 500 bp window centered on the CpGs), compared to fully methylated CpG sites, but not unmethylated CpGs or partially methylated CpGs. When considering only the 99 ASM CpGs located in CGI-associated gene promoter regions (promoter CGIs) 40.4% were near CTCF sites, while less than 30% of fully methylated and partially methylated and only 23% of completely unmethylated CpGs in promoter CGIs were near CTCF sites (Figure S8A). Conversely, the distribution of the different classes of CpG sites (ASM, fully methylated, partially methylated, fully unmethylated) with the presence of CTCF binding sites in a 500 bp window centered on the CpG sites compared to their distribution without CTCF binding sites in such windows, reflected this association between ASM and CTCF binding sites in promoter regions and CGIs, with an increased proportion of ASM in these regions (Figure S8B).

Next, to more confidently enumerate the CTCF sites overlapping or very close to regions of ASM, we looked specifically for CTCF binding sites with ≥2 ASM CpGs (as defined by Chen et al. [15]) in a 1 kb window centered on the CTCF peak. A total of 158 CTCF sites met this criterion; among them, 142 were gene associated, with at least one named gene within 100 kb of the CTCF sites. Of these genes, we were able to cross-tabulate 75 to the current GWAS catalog (http://www.genome.gov/gwastudies). Interestingly, 61 of them were associated with a major human trait or disease susceptibility signal, and for 25 genes the CTCF binding sites, ASM and the GWAS peak SNP were all located in the same haplotype block - suggesting that these GWAS signals reflect a bona fide (functionally active) regulatory haplotype (Table S4, including our annotations for CpG SNPs, and examples in Fig. 6C). Thus, while CTCF sites are not enriched overall near regions of ASM, ASM-associated CTCF sites have a somewhat different distribution than other CTCF sites and, more importantly, are often associated with GWAS peaks for human traits and diseases.

Allele-specific expression of some but not all genes near the imprinted and non-imprinted DMRs

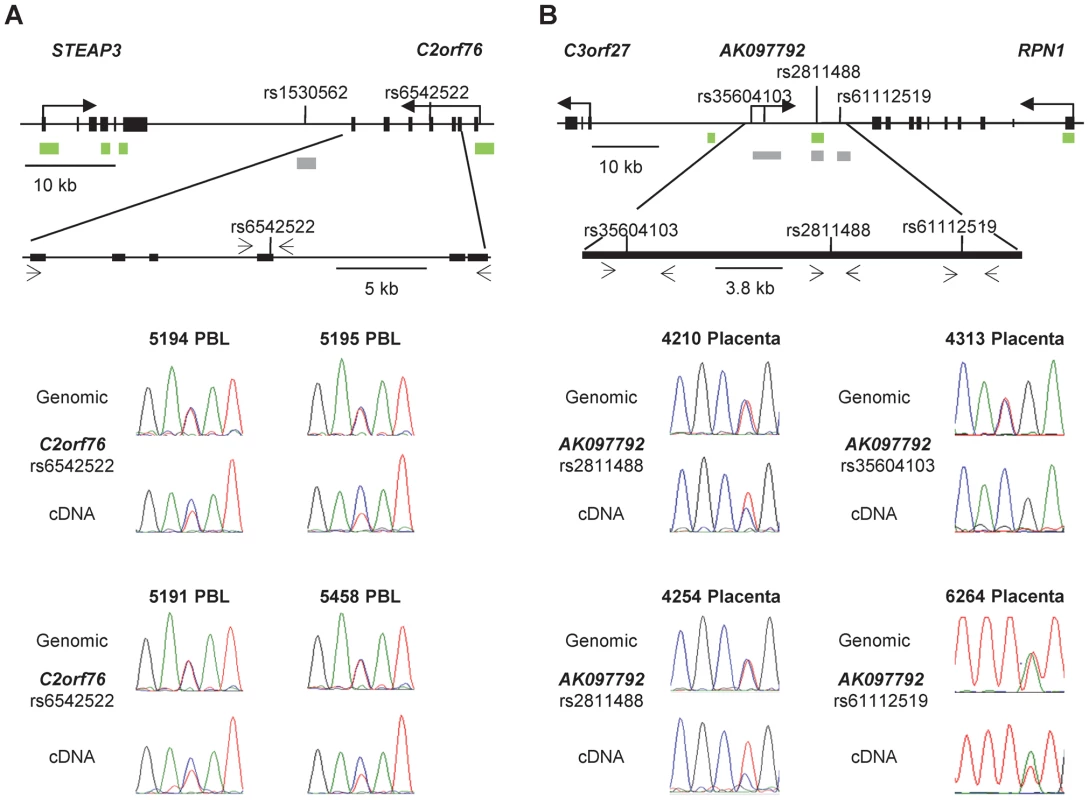

One of the biologically important consequences of ASM is allele-specific RNA expression (ASE). We previously demonstrated strong haplotype-dependent ASE of the CYP2A7 gene [7], and we were interested to ask whether ASE could be detected in the other chromosomal regions with ASM analyzed in this report. Assays comparing the representation of SNPs in genomic versus cDNA PCR products showed a definite and recurrent bias in allele-specific mRNA expression of the C2orf76 gene, associated with the STEAP3-C2orf76 DMR (Fig. 8). The untranslated AK097792 RNA transcript, associated with RPN1-C3orf27 DMR also showed a recurrent bias in ASE: from 13 tested individuals informative for ASE, 6 showed a definite but not complete allele-specific bias, four had complete ASE and three were biallelically expressed (Fig. 8 and Fig. S3). In each of 6 informative samples with definite or complete ASE, and data for ASM, the relatively hypermethylated allele was the repressed one, suggesting a functional link between ASE and ASM at this locus. Interestingly, current ENCODE data support our findings from RT-PCR of a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) traversing the DMR, and also suggest that a micro-RNA, as yet unnamed, arises from very close to this DMR (Figure S3).

Fig. 8. Non-imprinted ASM in the STEAP3-C2orf76 region and imprinted ASM in the RPN1-C3orf27 regions are both associated with ASE.

A, ASE of the C2orf76 gene, associated with the C2orf76-STEAP3 DMR, is shown in duplicate for four PBL samples (rs6542522). In each case the C allele is preferentially expressed in the cDNA when compared to the genomic DNA, consistent with the sequence dependent nature of ASM in this locus. Overall, 12 informative PBL samples were analyzed in duplicate for ASE and 7 PBL samples showed preferential expression of the C allele. Likewise, preferential expression of the C allele was identified in 7 out of the 22 informative liver samples (data not shown). B, ASE of the lncRNA corresponding to the AK097792 EST, overlapping the index SNP rs2811488 in the RPN1-C3orf27 intergenic DMR are shown on the left and those overlapping two additional informative SNPs, i.e. rs35604103 and rs61112519, are shown on the right for four placenta samples. Overall, the assays were performed in duplicates for 13 informative placenta samples. Ten of them showed a definite or complete ASE. In each of 6 informative samples assayed for both ASE and ASM, the hypermethylated maternal allele was the relatively repressed one. The absence of transcribed SNPs prevented ASE assays for VTRNA2-1, but as was found by Treppendahl et al. [8] using a different cell line, our assays for activation of this gene by the demethylating drug 5aza-dC provided evidence for methylation-dependent expression of VTRNA2-1 in HL60, ML3, and Jurkat leukemia cells (Figure S9). Additional analyses showed that the STEAP3 gene is biallelically expressed in PBL and liver, while TGFBI and SMAD5, flanking VTRNA2-1, exhibit only a slight allelic expression bias in PBL, as do RPN1 and C3orf27 in placental samples (data not shown).

Discussion

ASM is a well-studied hallmark of genomic imprinting. However, in the past several years this same type of allelic asymmetry has been found in and around many non-imprinted genes, both in normal human tissues and in F1 progeny of inter-strain mouse crosses [1], [17]. In contrast to imprinted ASM, in which the methylation status is dictated by the parent of origin of the allele, when ASM occurs at non-imprinted loci it is usually haplotype-dependent. Thus non-imprinted ASM is controlled by genetic polymorphisms, such as SNPs, indels and copy number variants (CNVs), which act in cis to set up the allelic asymmetries. The mechanism(s) by which this occurs are not yet understood. Research on this topic is important because haplotype-dependent ASM, with its functional correlate of genotype-specific gene expression manifesting as ASE and expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), is a major route by which inter-individual genetic differences in non-coding sequences can lead to differences in phenotypes, including disease susceptibility.

Here we have described new examples of genes and regulatory sequences with imprinted and non-imprinted ASM, which have revealed epigenomic features that are shared between these two epigenetic phenomena. Genes that are regulated by parental imprinting frequently have important roles in cell proliferation and tissue growth, so it is interesting that the VTRNA2-1 gene may have a suppressor role in human acute myeloid leukemias and other cancers [8], [18], and that vault RNAs are strongly upregulated during ES cell differentiation [19]. Similarly, given the clear importance of multiple imprinted genes in placental and fetal growth [10], [11], and the accumulating data for rare but recurrent alterations of maternal imprints in offspring conceived by assisted reproductive technologies, the imprinted C3orf27-RPN1 chromosomal domain, including the lncRNA corresponding to the AK097792 EST, as well as other RNAs, such as the as yet unnamed micro-RNA precisely localized to this region by data from the ENCODE/CSH project (Figure S3) will be interesting for future studies of placental growth and function. The loci with non-imprinted ASM that we have described here are also potentially relevant to human traits. CYP2A7 is located immediately adjacent to and is highly homologous to the CYP2A6 gene, and both genes are predicted to encode cytochrome P450 proteins responsible for coumarin and nicotine metabolism and smoking behavior [20]. The C2orf76 gene encodes a protein with unknown function, but a non-synonymous SNP in this gene was tentatively implicated in HIV susceptibility in African-Americans by GWAS at a nominal p-value of 0.0001 [21]. As we have previously pointed out [1], a major utility of mapping non-imprinted, haplotype-dependent ASM is to reveal bona fide regulatory haplotypes underlying human complex disease susceptibility. In this regard, our current analysis of prior whole genome bis-seq data has already yielded an interesting set of additional loci in which GWAS signals for important human traits and disease susceptibility coincide with both ASM and CTCF sites.

Lastly, our data lay an essential groundwork for testing mechanisms of haplotype-dependent ASM. One feasible application will be in determining the minimal sequence requirements that allow local haplotypes to dictate methylation patterns in cis: based on our mapping data it should be possible to design allelic series of large bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) containing the chromosomal regions described here, which can be subjected to targeted site-directed mutagenesis, including the CTCF sites as well as haplotype-specific sequences outside of these sites, and then analyzed for cis-effects on CpG methylation patterns in vivo in BAC-transgenic mice.

Materials and Methods

MSNP analysis

Tissues from human organs were obtained, without patient identifiers, from the Molecular Pathology Shared Resource of the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center and blood samples from volunteers were obtained with informed consent under protocols approved by the internal review board of Columbia University Medical Center. MSNP assays were performed as previously described [7]. Affymetrix 250K StyI and 6.0 SNP arrays were used, with initial complete digestions of the genomic DNA samples with StyI (250K arrays) or NspI (6.0 arrays), with the methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme HpaII or with its methylation-insensitive isoschizomer MspI, followed by probe synthesis and labeling as recommended by Affymetrix. The MSNP data were processed numerically as described [7], followed by visualization of the allele-specific hybridization data in dChip [22] to identify SNP-tagged StyI or NspI restriction fragments where call conversions were made from AB with no HpaII to AA or BB with HpaII pre-digestion. Based on recurrent call conversions in two or more samples and consistency of hybridization across multiple probes on visualization of the intensity data, we selected loci for validation of ASM by bis-seq of amplicons spanning the original index SNPs.

Local methylation mapping by Sanger bis-seq

We used Sanger bis-seq of multiple clones for intensive short-range mapping of ASM in each of the 5 chromosomal regions, as well as for filling gaps in the long-read 454 bis-seq. Genomic DNA (0.5 µg) was bisulfite converted using the EpiTect Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's protocol. Primers were designed in MethPrimer [23] to encompass >5 contiguous CpGs and one or more SNP, and the converted DNA was amplified for regions of interest using optimized PCR conditions (Table S1). PCR reactions were performed in duplicate then pooled and purified using the Wizard SV System (Promega), followed by cloning using the TOPO TA Kit (Invitrogen). Multiple clones were sequenced.

Extended methylation mapping by Fluidigm bisulfite PCR and 454 long-read sequencing

Primer sets spanning 50–100 kb on each side of each of the three index fragments for long-range mapping were designed as described in [24] and in part empirically, using both strands of an in silico bisulfite-converted SNP-masked genome. Primer sequences were not allowed to overlap with any SNPs having >1 percent heterozygote frequency in dbSNP130. Amplicons were allowed to range between 200–650 bp in size, with most between 200–450 bp. CpG content was allowed to range between 0–1 CpGs per primer with zero CpGs preferred. Tm was allowed to range from 56–60°C, primer GC content is allowed to range between 35–65%, and self-complementarity, primer-primer complementarity, and hairpin formation is restricted for stable structures with melting temperatures above 46°C. Primers generating off target amplicons of size 50–2000 bp (with two mismatches allowed) were filtered out by scanning against a bisulfite converted genome with NCBI reverse e-PCR. From these primer sets, 41 amplicons for the VTRNA2-1 region, 27 amplicons for the STEAP3-C2orf76 region and 25 amplicons for the C3orf27-RPN1 region were picked based on minimum cut-offs for the number of CpG sites encompassed in each amplicon (≥4), and heterozygosity frequencies of annotated SNPs between the primers (≥.2). For VTRNA2-1 region, 6 additional amplicons covering 3 CpGs were included. Primer sequences are in Table S2. Bisulfite modification was performed for 96 samples using 2 ug of genomic DNA and the Epitect 96 Kit (Qiagen), following the recommended protocol. The bisulfite modified DNA was re-precipitated and concentrated using Pellet Paint (EMD Chemicals). To amplify the DNA from the 96 samples, the Fluidigm 48×48 Access Array was used, with JumpStart Taq Polymerase (Sigma) and a 60°C touchdown for ten cycles followed by 51°C for 29 cycles of amplification. Of the resulting PCR products, one microliter of a 1∶50 dilution was used in a second barcoding PCR reaction. Fluidigm barcodes designed with 454 adapters were added to samples 1–48 and 49–96 during this PCR step. Both the 454 FLX instrument and 454Junior instrument and their emPCR and Sequencing kits (Roche) were used. The barcoded PCR products were pooled and purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads and a titration was performed (described in 454 provided protocol) in order to find the best bead∶DNA ratio required to remove DNA fragments smaller than 300 bp. The purified PCR products were then prepared for sequencing following the 454 emulsion PCR protocol (Roche). A titration of bead∶DNA ratios was also performed during this step to ensure an ideal ratio was achieved in order to obtain the best sequencing results. The amplified PCR products were then sequenced using the sequencing kits designed for each instrument. The filter settings were adjusted on the 454 sequence analysis software to a vfTrimBack Scale Factor of .5. The sequences were then mapped, scored for each previously identified SNP, and each allele was analyzed for percent methylation, both at individual CpGs and averaged over all CpGs in the amplicon. Of the original 99 primer pairs, 91 gave a sufficient number of reads to allow genotyping (minimum ten reads with at least 20% of reads representing the minor allele), and net methylation analysis in most samples, and in at least 3 samples per tissue (minimum 7 reads), as well as scoring ASM in multiple heterozygous samples. Also included were data from >3500 full-length Sanger bis-seq reads of from 300 to 500 bp performed on several amplicons and tissues. T-tests were performed to determine significant ASM, p<0.05, for samples with at least 5 reads per allele.

Q-PCR and analysis of allele specific mRNA expression (ASE)

Tissue and blood cell RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA was then reverse transcribed to cDNA using RT Kit (AmbionRETROscript) with random hexamer primers. PCR primers were designed for genomic DNA and cDNA to cover a SNP in the exon of the gene of interest using Primer3 software, with the cDNA primers spanning an intron of the gene, or in the case of the AK097792 non-translated RNA, not spanning an intron but verified as amplifying only cDNA in the samples tested, by lack of PCR product in the minus-RT control reaction (Table S3). Genomic DNA and cDNA were amplified by PCR and the PCR products were Sanger sequenced from duplicate reactions. The sequence chromatograms were analyzed by comparing peak heights of the two alleles in heterozygous individuals in the genomic DNA versus cDNA. For measuring expression of the VTRNA2-1 small RNA we used a custom TaqMan assay (Applied Biosystems) according to the recommended protocol.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from whole blood following the manufacturer's instructions for FicollPaque Plus reagent (GE). Chromatin Immunoprecipitation was performed on the PBMCs using the Magna-ChIP G Kit from Millipore following the suggested protocol with some slight modifications. Cell fixation was performed for six minutes. Sonication was performed using a Fisher Sonic Dismembrator at a power setting of 3.2 for 2 minutes total sonication time with 2 seconds sonication followed by 8 seconds recovery. Four micrograms of anti-CTCF antibody (Millipore) was used in an overnight incubation at 4°C with sheared chromatin and protein G Magna ChIP beads. PCR for the STEAP3-C2orf76 DMR was then performed using primers: Forward, GACAGACTCTGCTGCCACCT and Reverse, AGCAGCTTCTTCTCGGTATG. Two microliters of purified input, negative control IgG and CTCF immunoprecipitated samples were used for PCR with a touchdown from 60°C to 51°C for 38 cycles.

Analysis of genome-wide association of ASM with CTCF binding sites

Previously published ASM site lists from the whole genome bis-seq of H1 hESC cells were downloaded [15], [16]. The dataset included 514,181 CpG sites tested for ASM by Chen et al. [15]. Of these, 79,365 were CpG sites classified as ASM. For this analysis, in addition to ASM sites, we grouped CpG sites without evidence of ASM into 3 categories: full methylation (200,318 CpG sites with >90% of reads with methylation at the CpG site), partial methylation (232,724 CpG sites with 10% to 90% of reads with methylation at the CpG site) or complete lack of methylation (1,774 CpG sites with <10% of reads with methylation at the CpG site). To assess the presence of CTCF binding peaks in a 500 base window centered on each CG tested for ASM, we used ChIP-seq data generated in H1 hESC cells by the Broad/MGH (UCSC accession number: wgEncodeEH000085), Hudson alpha (UCSC accession number: wgEncodeEH001649) and UT-Austin (UCSC accession number: wgEncodeEH000560) ENCODE groups. We searched for CTCF binding sites present in at least one of these datasets and found 13,485 CTCF binding sites in the vicinity of the CpG sites included into this analysis. We performed sub-analyses in order to look specifically at CpG sites in intergenic regions or intragenic region, as well as in gene promoter regions (1 kb upstream and downstream of transcription starting sites of genes) and/or close to CGIs (within 250 bp), using data available from the UCSC genome browser. All p-values for these analyses were calculated using one-sided Fischer exact tests.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. TyckoB (2010) Allele-specific DNA methylation: beyond imprinting. Human Molecular Genetics 19: R210–220.

2. HarkAT, SchoenherrCJ, KatzDJ, IngramRS, LevorseJM, et al. (2000) CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature 405 : 486–489.

3. BellAC, FelsenfeldG (2000) Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature 405 : 482–485.

4. ShinJY, FitzpatrickGV, HigginsMJ (2008) Two distinct mechanisms of silencing by the KvDMR1 imprinting control region. Embo J 27 : 168–178.

5. FitzpatrickGV, PugachevaEM, ShinJY, AbdullaevZ, YangY, et al. (2007) Allele-specific binding of CTCF to the multipartite imprinting control region KvDMR1. Mol Cell Biol 27 : 2636–2647.

6. TakadaS, PaulsenM, TevendaleM, TsaiCE, KelseyG, et al. (2002) Epigenetic analysis of the Dlk1-Gtl2 imprinted domain on mouse chromosome 12: implications for imprinting control from comparison with Igf2-H19. Human molecular genetics 11 : 77–86.

7. KerkelK, SpadolaA, YuanE, KosekJ, JiangL, et al. (2008) Genomic surveys by methylation-sensitive SNP analysis identify sequence-dependent allele-specific DNA methylation. Nat Genet 40 : 904–908.

8. TreppendahlMB, QiuX, SogaardA, YangX, Nandrup-BusC, et al. (2012) Allelic methylation levels of the noncoding VTRNA2-1 located on chromosome 5q31.1 predict outcome in AML. Blood 119 : 206–216.

9. FrankD, FortinoW, ClarkL, MusaloR, WangW, et al. (2002) Placental overgrowth in mice lacking the imprinted gene Ipl. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99 : 7490–7495.

10. TyckoB (2006) Imprinted genes in placental growth and obstetric disorders. Cytogenet Genome Res 113 : 271–278.

11. CoanPM, BurtonGJ, Ferguson-SmithAC (2005) Imprinted genes in the placenta–a review. Placenta 26 Suppl A: S10–20.

12. WildmanDE (2011) Review: Toward an integrated evolutionary understanding of the mammalian placenta. Placenta 32 Suppl 2: S142–145.

13. GeorgiadesP, Ferguson-SmithAC, BurtonGJ (2002) Comparative developmental anatomy of the murine and human definitive placentae. Placenta 23 : 3–19.

14. RosenbloomKR, DreszerTR, LongJC, MalladiVS, SloanCA, et al. (2012) ENCODE whole-genome data in the UCSC Genome Browser: update 2012. Nucleic Acids Res 40: D912–917.

15. ChenPY, FengS, JooJW, JacobsenSE, PellegriniM (2011) A comparative analysis of DNA methylation across human embryonic stem cell lines. Genome Biol 12: R62.

16. ListerR, PelizzolaM, DowenRH, HawkinsRD, HonG, et al. (2009) Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature 462 : 315–322.

17. SchillingE, El ChartouniC, RehliM (2009) Allele-specific DNA methylation in mouse strains is mainly determined by cis-acting sequences. Genome Res 19 : 2028–2035.

18. LeeK, KunkeawN, JeonSH, LeeI, JohnsonBH, et al. (2011) Precursor miR-886, a novel noncoding RNA repressed in cancer, associates with PKR and modulates its activity. RNA 17 : 1076–1089.

19. SkrekaK, SchaffererS, NatIR, ZywickiM, SaltiA, et al. (2012) Identification of differentially expressed non-coding RNAs in embryonic stem cell neural differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res [epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1093/nar/gks311

20. RaunioH, Rahnasto-RillaM (2012) CYP2A6: genetics, structure, regulation, and function. Drug metabolism and drug interactions 27 : 73–88.

21. PelakK, GoldsteinDB, WalleyNM, FellayJ, GeD, et al. (2010) Host determinants of HIV-1 control in African Americans. The Journal of infectious diseases 201 : 1141–1149.

22. LinM, WeiLJ, SellersWR, LieberfarbM, WongWH, et al. (2004) dChipSNP: significance curve and clustering of SNP-array-based loss-of-heterozygosity data. Bioinformatics 20 : 1233–1240.

23. LiLC, DahiyaR (2002) MethPrimer: designing primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics 18 : 1427–1431.

24. KomoriHK, LaMereSA, TorkamaniA, HartGT, KotsopoulosS, et al. (2011) Application of microdroplet PCR for large-scale targeted bis-seq. Genome Res 21 : 1738–1745.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Re-Ranking Sequencing Variants in the Post-GWAS Era for Accurate Causal Variant IdentificationČlánek Bypass of 8-oxodGČlánek Integrated Model of and Inherited Genetic Variants Yields Greater Power to Identify Risk GenesČlánek Comparative Genomic and Functional Analysis of 100 Strains and Their Comparison with Strain GGČlánek A Nuclear Calcium-Sensing Pathway Is Critical for Gene Regulation and Salt Stress Tolerance inČlánek Computational Identification of Diverse Mechanisms Underlying Transcription Factor-DNA OccupancyČlánek Reversible and Rapid Transfer-RNA Deactivation as a Mechanism of Translational Repression in StressČlánek Genome-Wide Association of Body Fat Distribution in African Ancestry Populations Suggests New Loci

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2013 Číslo 8- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Reveals Persistent Hypomethylation of Interferon Genes and Compositional Changes to CD4+ T-cell Populations

- Re-Ranking Sequencing Variants in the Post-GWAS Era for Accurate Causal Variant Identification

- Histone Variant HTZ1 Shows Extensive Epistasis with, but Does Not Increase Robustness to, New Mutations

- Past Visits Present: TCF/LEFs Partner with ATFs for β-Catenin–Independent Activity

- Functional Characterisation of Alpha-Galactosidase A Mutations as a Basis for a New Classification System in Fabry Disease

- A Flexible Approach for the Analysis of Rare Variants Allowing for a Mixture of Effects on Binary or Quantitative Traits

- Masculinization of Gene Expression Is Associated with Exaggeration of Male Sexual Dimorphism

- Genic Intolerance to Functional Variation and the Interpretation of Personal Genomes

- Endogenous Stress Caused by Faulty Oxidation Reactions Fosters Evolution of 2,4-Dinitrotoluene-Degrading Bacteria

- Transposon Domestication versus Mutualism in Ciliate Genome Rearrangements

- Comparative Anatomy of Chromosomal Domains with Imprinted and Non-Imprinted Allele-Specific DNA Methylation

- An Essential Function for the ATR-Activation-Domain (AAD) of TopBP1 in Mouse Development and Cellular Senescence

- Depletion of Retinoic Acid Receptors Initiates a Novel Positive Feedback Mechanism that Promotes Teratogenic Increases in Retinoic Acid

- Bypass of 8-oxodG

- Calpain-6 Deficiency Promotes Skeletal Muscle Development and Regeneration

- ATM Release at Resected Double-Strand Breaks Provides Heterochromatin Reconstitution to Facilitate Homologous Recombination

- Generation of Tandem Direct Duplications by Reversed-Ends Transposition of Maize Elements

- Loss of a Conserved tRNA Anticodon Modification Perturbs Cellular Signaling

- Integrated Model of and Inherited Genetic Variants Yields Greater Power to Identify Risk Genes

- High-Throughput Genetic and Gene Expression Analysis of the RNAPII-CTD Reveals Unexpected Connections to SRB10/CDK8

- Dynamic Rewiring of the Retinal Determination Network Switches Its Function from Selector to Differentiation

- β-Catenin-Independent Activation of TCF1/LEF1 in Human Hematopoietic Tumor Cells through Interaction with ATF2 Transcription Factors

- Genetic Mapping of Specific Interactions between Mosquitoes and Dengue Viruses

- A Highly Redundant Gene Network Controls Assembly of the Outer Spore Wall in

- Origin and Functional Diversification of an Amphibian Defense Peptide Arsenal

- Myc-Driven Overgrowth Requires Unfolded Protein Response-Mediated Induction of Autophagy and Antioxidant Responses in

- Integrative Modeling of eQTLs and Cis-Regulatory Elements Suggests Mechanisms Underlying Cell Type Specificity of eQTLs

- Species and Population Level Molecular Profiling Reveals Cryptic Recombination and Emergent Asymmetry in the Dimorphic Mating Locus of

- Ras-Induced Changes in H3K27me3 Occur after Those in Transcriptional Activity

- Characterization of the p53 Cistrome – DNA Binding Cooperativity Dissects p53's Tumor Suppressor Functions

- Global Analysis of Fission Yeast Mating Genes Reveals New Autophagy Factors

- Deficiency Suppresses Intestinal Tumorigenesis

- Introns Regulate Gene Expression in in a Pab2p Dependent Pathway

- Meiotic Recombination Initiation in and around Retrotransposable Elements in

- Comparative Oncogenomic Analysis of Copy Number Alterations in Human and Zebrafish Tumors Enables Cancer Driver Discovery

- Comparative Genomic and Functional Analysis of 100 Strains and Their Comparison with Strain GG

- A Model-Based Analysis of GC-Biased Gene Conversion in the Human and Chimpanzee Genomes

- Masculinization of the X Chromosome in the Pea Aphid

- The Architecture of a Prototypical Bacterial Signaling Circuit Enables a Single Point Mutation to Confer Novel Network Properties

- Distinct SUMO Ligases Cooperate with Esc2 and Slx5 to Suppress Duplication-Mediated Genome Rearrangements

- The Yeast Environmental Stress Response Regulates Mutagenesis Induced by Proteotoxic Stress

- Mediator Directs Co-transcriptional Heterochromatin Assembly by RNA Interference-Dependent and -Independent Pathways

- The Genome of and the Basis of Host-Microsporidian Interactions

- Regulation of Sister Chromosome Cohesion by the Replication Fork Tracking Protein SeqA

- Neuronal Reprograming of Protein Homeostasis by Calcium-Dependent Regulation of the Heat Shock Response

- A Nuclear Calcium-Sensing Pathway Is Critical for Gene Regulation and Salt Stress Tolerance in

- Cross-Species Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization Identifies Novel Oncogenic Events in Zebrafish and Human Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma

- : A Mouse Strain with an Ift140 Mutation That Results in a Skeletal Ciliopathy Modelling Jeune Syndrome

- The Relative Contribution of Proximal 5′ Flanking Sequence and Microsatellite Variation on Brain Vasopressin 1a Receptor () Gene Expression and Behavior

- Combining Quantitative Genetic Footprinting and Trait Enrichment Analysis to Identify Fitness Determinants of a Bacterial Pathogen

- The Innocence Project at Twenty: An Interview with Barry Scheck

- Computational Identification of Diverse Mechanisms Underlying Transcription Factor-DNA Occupancy

- GUESS-ing Polygenic Associations with Multiple Phenotypes Using a GPU-Based Evolutionary Stochastic Search Algorithm

- H2A.Z Acidic Patch Couples Chromatin Dynamics to Regulation of Gene Expression Programs during ESC Differentiation

- Identification of DSB-1, a Protein Required for Initiation of Meiotic Recombination in , Illuminates a Crossover Assurance Checkpoint

- Binding of TFIIIC to SINE Elements Controls the Relocation of Activity-Dependent Neuronal Genes to Transcription Factories

- Global Analysis of the Sporulation Pathway of

- Genetic Circuits that Govern Bisexual and Unisexual Reproduction in

- Deletion of microRNA-80 Activates Dietary Restriction to Extend Healthspan and Lifespan

- Fifty Years On: GWAS Confirms the Role of a Rare Variant in Lung Disease

- The Enhancer Landscape during Early Neocortical Development Reveals Patterns of Dense Regulation and Co-option

- Gene Expression Regulation by Upstream Open Reading Frames and Human Disease

- Sociogenomics of Cooperation and Conflict during Colony Founding in the Fire Ant

- The Intronic Long Noncoding RNA Recruits PRC2 to the Promoter, Reducing the Expression of and Increasing Cell Proliferation

- The , p.E318G Variant Increases the Risk of Alzheimer's Disease in -ε4 Carriers

- The Wilms Tumor Gene, , Is Critical for Mouse Spermatogenesis via Regulation of Sertoli Cell Polarity and Is Associated with Non-Obstructive Azoospermia in Humans

- Reversible and Rapid Transfer-RNA Deactivation as a Mechanism of Translational Repression in Stress

- QTL Analysis of High Thermotolerance with Superior and Downgraded Parental Yeast Strains Reveals New Minor QTLs and Converges on Novel Causative Alleles Involved in RNA Processing

- Genome Wide Association Identifies Novel Loci Involved in Fungal Communication

- Chromatin Sampling—An Emerging Perspective on Targeting Polycomb Repressor Proteins

- A Recessive Founder Mutation in Regulator of Telomere Elongation Helicase 1, , Underlies Severe Immunodeficiency and Features of Hoyeraal Hreidarsson Syndrome

- Genome-Wide Association of Body Fat Distribution in African Ancestry Populations Suggests New Loci

- Causal and Synthetic Associations of Variants in the Gene Cluster with Alpha1-antitrypsin Serum Levels

- Hard Selective Sweep and Ectopic Gene Conversion in a Gene Cluster Affording Environmental Adaptation

- Brittle Culm1, a COBRA-Like Protein, Functions in Cellulose Assembly through Binding Cellulose Microfibrils

- Chromosomal Copy Number Variation, Selection and Uneven Rates of Recombination Reveal Cryptic Genome Diversity Linked to Pathogenicity

- The Ribosomal Protein Rpl22 Controls Ribosome Composition by Directly Repressing Expression of Its Own Paralog, Rpl22l1

- Ras1 Acts through Duplicated Cdc42 and Rac Proteins to Regulate Morphogenesis and Pathogenesis in the Human Fungal Pathogen

- The DSB-2 Protein Reveals a Regulatory Network that Controls Competence for Meiotic DSB Formation and Promotes Crossover Assurance

- Recurrent Modification of a Conserved -Regulatory Element Underlies Fruit Fly Pigmentation Diversity

- Associations of Mitochondrial Haplogroups B4 and E with Biliary Atresia and Differential Susceptibility to Hydrophobic Bile Acid

- The Conditional Nature of Genetic Interactions: The Consequences of Wild-Type Backgrounds on Mutational Interactions in a Genome-Wide Modifier Screen

- A Critical Function of Mad2l2 in Primordial Germ Cell Development of Mice

- A Role for CF1A 3′ End Processing Complex in Promoter-Associated Transcription

- Vitellogenin Underwent Subfunctionalization to Acquire Caste and Behavioral Specific Expression in the Harvester Ant

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Chromosomal Copy Number Variation, Selection and Uneven Rates of Recombination Reveal Cryptic Genome Diversity Linked to Pathogenicity

- Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Reveals Persistent Hypomethylation of Interferon Genes and Compositional Changes to CD4+ T-cell Populations

- Associations of Mitochondrial Haplogroups B4 and E with Biliary Atresia and Differential Susceptibility to Hydrophobic Bile Acid

- A Role for CF1A 3′ End Processing Complex in Promoter-Associated Transcription

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy