-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

AAA-ATPase FIDGETIN-LIKE 1 and Helicase FANCM Antagonize Meiotic Crossovers by Distinct Mechanisms

Sexually reproducing species produce offspring that are genetically unique from one another, despite having the same parents. This uniqueness is created by meiosis, which is a specialized cell division. After meiosis each parent transmits half of their DNA, but each time this occurs, the 'half portion' of DNA transmitted to offspring is different from the previous. The differences are due to resorting the parental chromosomes, but also recombining them. Here we describe a gene—FIDGETIN-LIKE 1—which limits the amount of recombination that occurs during meiosis. Previously we identified a gene with a similar function, FANCM. FIGL1 and FANCM operate through distinct mechanisms. This discovery will be useful to understand more, from an evolutionary perspective, why recombination is naturally limited. Also this has potentially significant applications for plant breeding which is largely about sampling many 'recombinants' to find individuals that have heritable advantages compared to their parents.

Published in the journal: AAA-ATPase FIDGETIN-LIKE 1 and Helicase FANCM Antagonize Meiotic Crossovers by Distinct Mechanisms. PLoS Genet 11(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005369

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1005369Summary

Sexually reproducing species produce offspring that are genetically unique from one another, despite having the same parents. This uniqueness is created by meiosis, which is a specialized cell division. After meiosis each parent transmits half of their DNA, but each time this occurs, the 'half portion' of DNA transmitted to offspring is different from the previous. The differences are due to resorting the parental chromosomes, but also recombining them. Here we describe a gene—FIDGETIN-LIKE 1—which limits the amount of recombination that occurs during meiosis. Previously we identified a gene with a similar function, FANCM. FIGL1 and FANCM operate through distinct mechanisms. This discovery will be useful to understand more, from an evolutionary perspective, why recombination is naturally limited. Also this has potentially significant applications for plant breeding which is largely about sampling many 'recombinants' to find individuals that have heritable advantages compared to their parents.

Introduction

Meiotic crossovers (COs) shuffle parental alleles in the offspring, introducing genetic variety on which selection can act. COs are produced by homologous recombination (HR) that is used to repair the numerous programmed DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) that form in early prophase I. DSBs can be repaired using a homologous template giving rise to COs or non-crossovers (NCOs), or using the sister chromatid leading to inter-sister chromatid exchanges (IS-NCOs or IS-COs). [1]. However, only COs between homologous chromosomes provide the basis for a physical link, forming a structure called a bivalent, and thus COs are required for proper chromosome segregation in most species [2].

DSB formation is catalyzed by the conserved protein, SPO11 [3]. Resection of both sides of the break produces two 3′ single strand overhangs. One of these overhangs can invade a homologous template, either the homologous chromosome or the sister chromatid, producing a joint DNA molecule, the displacement loop (D-loop) [4]. Two strand-exchange enzymes catalyze this template invasion step: RAD51 and the meiosis-specific DMC1 polymerize on the single-strand DNA and promote invasion of the intact homologous template [5,6]. The choice of the template for repair is crucial to form COs during meiosis, and the respective roles of DMC1, RAD51 and their co-factors in ensuring inter-homologue bias and avoiding inter-sister repair remains to be fully understood [6–10]. Studies in several organisms have demonstrated that multiple co-operative factors influence meiotic template choice [11]. In budding yeast it has been shown that while both DMC1 and RAD51 are recruited at DSB sites, RAD51 strand-exchange activity is not required for strand invasion at meiosis, and that RAD51 is relegated to a role as a DMC1 co-factor [6]. The same is likely true in Arabidopsis [10]. In plants, an additional player, the cyclin SDS, is essential for DMC1 focus formation, DMC1-mediated bias toward inter-homolog DSB repair and CO formation [12,13].

Following D-loop formation, the invading strand then primes DNA synthesis, using the complementary strand of the invaded duplex as a template. The mode of repair of this joint molecule determines the outcome as a CO or an NCO. First, the extended invading strand can be unwound and can re-anneal with the second end of the DSB, a mechanism called SDSA (synthesis-dependent strand annealing), leading to the repair of the breaks exclusively as NCOs [14]. Alternatively two pathways that produce COs co-exist in many species including Arabidopsis [15,16]: the first depends on a group of proteins collectively referred to as the ZMM proteins [17] and the MLH1-MLH3 proteins (class I CO), which promotes the formation of double Holliday junctions and their resolution as COs [18]. The second CO pathway, that can produce both COs and NCOs, depends on structure-specific endonucleases including MUS81 (class II COs) [18]. Class I COs are sensitive to interference: they tend to be distributed further apart—from one another—along the same chromosome than expected by chance. In contrast, class II COs are distributed independently from each other [19], but not completely independently from class I COs as recently shown in tomato [20]. In Arabidopsis, the ZMM pathway accounts for the formation of about 85% of COs, the class II pathway being minor [21,22].

Despite an excess of recombination precursors, most species only form close to the one, obligatory, CO per chromosome [23]. Mechanisms underlying this limitation are currently being unraveled, but still very few anti-CO proteins are known [24–30]. The helicase FANCM, with its two co-factors MHF1 and MHF2, defined the first known anti-CO pathway in plants and limit class II COs [24,31].

In this study, continuing the genetic screen that identified FANCM and MHF1-MHF2, we identify FIDGETIN-Like-1 (FIGL1) as a new gene limiting meiotic CO formation. Human FIGL1 was previously shown to interact directly with RAD51 and to be required for efficient HR-mediated DNA repair in human U2OS cells [32]. Here we show that FIGL1 limits class II COs at meiosis and that FANCM and FIGL1 act through distinct mechanisms to limit meiotic crossovers. While FANCM likely unwinds post-invasion intermediates to produce NCOs [24,26], we provide evidence that FIGL1 limits meiotic CO formation by regulating the invasion step of meiotic homologous recombination.

Results

A genetic screen for suppression of the lack of chiasmata in zmm mutants identified FIGL1

CO-deficient mutants (e.g. zmm mutants) of Arabidopsis display reduced fertility, noticeable by their reduction in fruit length, due to homologous chromosomes not segregating correctly at meiosis I and the ensuing formation of aneuploid gametes. We designed a genetic screen to identify anti-CO factors in Arabidopsis, as described previously [24]. Using fruit length as a proxy for the level of CO formation, we screened for suppressors of CO-deficient mutants (the zmm mutants; zip4, shoc1, hei10, msh4 and msh5, S1 Table), based on the idea that mutation of ‘anti-CO’ genes would restore the level of CO formation and therefore correct chromosome segregation and fertility of the plants. It should be noted that this screen would be unable to recover mutants with elevated class I COs only, but could recover mutants in which class II COs or both CO classes are increased.

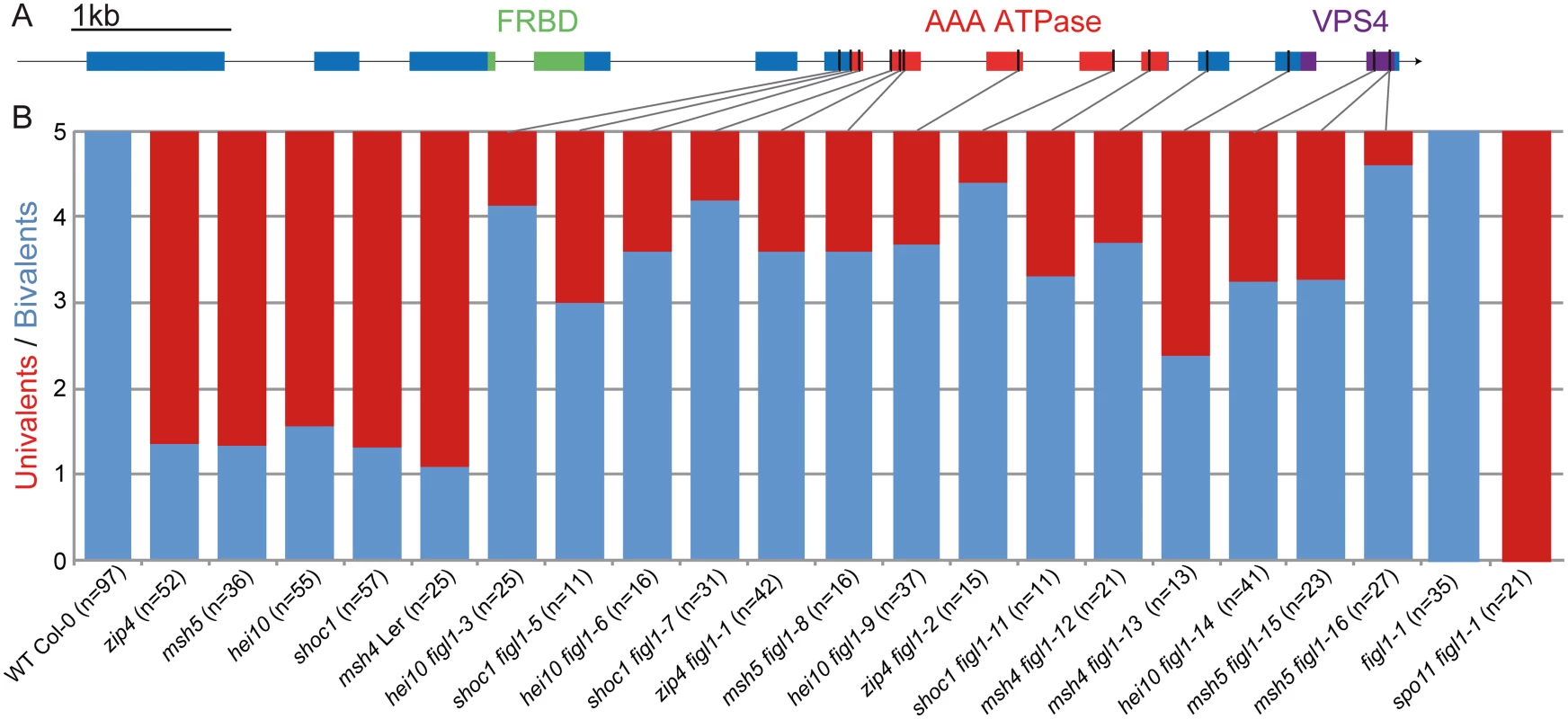

The zip4 suppressor screen led to the isolation of three complementation groups. The study of the first two revealed FANCM and MHF1-MHF2 as anti-CO proteins that act in the same pathway [24,31]. Here we focus on the third complementation group that has two allelic suppressors, zip4(s)4 and zip4(s)5 (S1 Table). Using mapping and whole genome sequencing, we identified a putative causal mutation in zip4(s)5, a deletion of one base pair in the gene At3g27120. The allelic suppressor zip4(s)4 contained also a mutation in this gene, showing that the At3g27120 mutation is responsible for the fertility restoration. This was further consolidated by the identification of 12 other allelic mutations in the other zmm screens (Fig 1 and S1 Table). In wild-type Arabidopsis meiosis, the five pairs of homologs always form five bivalents at metaphase I, whereas zmm mutants have few bivalents (~1.3 bivalent per meiosis, Fig 1B). All figl1 alleles largely, but never entirely, restored bivalent formation in all zmm backgrounds tested (Fig 1B). No growth or development defects were observed in these mutants.

Fig. 1. Mutations in FIGL1 restores bivalent formation in zmm mutants.

A: Gene model of the FIDGETIN-Like-1 gene, exons appear as blue boxes, the conserved domains are indicated in green, red and purple. Black lines represent the position of the point mutations. B: Univalent pairs (red) and bivalents (blue) count of metaphase I male meiocytes in wild type, zmm mutants (zip4, msh4, msh5, hei10 and shoc1) and in zmm figl1 double mutants, as well as figl1 single mutants and figl1-1 spo11 double mutants. All genotypes are in a Columbia-0 background, except for msh4 figl1-12 and msh4 figl1-13 which are in a Landsberg erecta background (Ler). Sequencing of the cDNA revealed a mis-annotation as the two in silico predicted genes AT3G27120 and AT3G27130 correspond to one mRNA in vivo (Genbank accession KM055500; S1A Fig). Reciprocal BLAST analysis showed that the protein encoded by this gene is the single representative of the AAA-ATPase FIDGETIN family in Arabidopsis (S1B Fig). The FIDGETIN protein family comprises three proteins in mammals (FIDGETIN, FIDGETIN-Like-1 and FIDGETIN-Like-2). Phylogenetic analysis showed that only FIDGETIN-Like-1 (FIGL1) is conserved in other branches of eukaryotes, including Arabidopsis (S1B and S1C Fig). FIGL1 is present in most eukaryotic clades; however, we could not detect any representative of the FIDGETIN family in fungi, with the exception of the early divergent Microsporidia genera that possesses a FIGL1, suggesting that this gene was lost early after the fungi lineage divergence. Mouse FIGL1 is highly expressed in meiocytes [33], and human FIGL1 has been reported to be essential for efficient HR-mediated DNA repair in somatic cells, through a direct interaction with RAD51 [32]. FIGL1 also interacts with KIAA0146/SPIDR which is involved in HR and that in turns interacts with RAD51 and BLM, the latter is a helicase involved in DSB repair known to antagonize crossover formation [34]. All these findings point towards a conserved role for FIGL1 in homologous recombination.

Attempts to localize the FIGL1 protein in planta, and notably in meiocytes, were unsuccessful. However, using over-expression of the protein in Tobacco leaves, we were able to detect a strong signal in the nucleus (S1D Fig), suggesting that FIGL1 is targeted to the nucleus, at least when over-expressed in somatic cells.

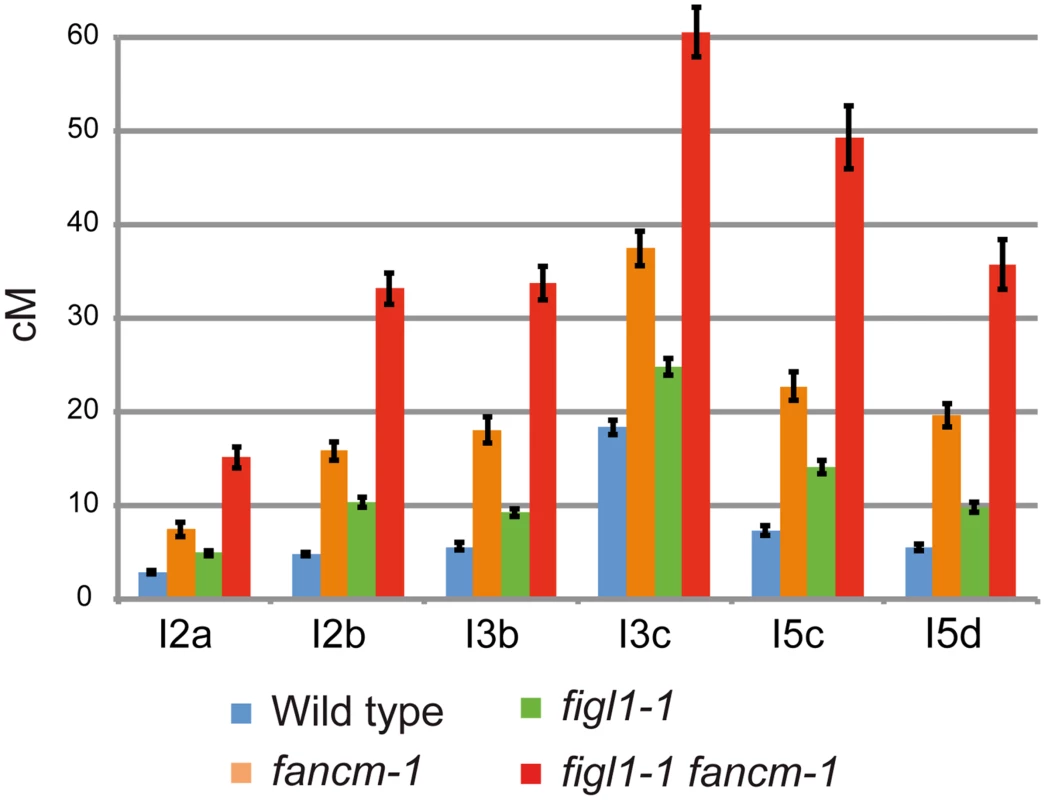

figl1 increases meiotic recombination in a multiplicative manner with fancm

To directly test the effect of FIGL1 mutation on CO frequency, we performed tetrad analysis to measure recombination in a series of intervals defined by markers conferring fluorescence in pollen grains (Fluorescent-Tagged Lines—FTLs) [35] (Fig 2 and S2 Fig). These data showed that: (i) the figl1-1 mutation restores recombination of the zip4 mutant, in accordance with the restoration of bivalent formation (S2A Fig); (ii) in the single figl1-1 mutant, CO frequency is increased in each of the six intervals tested (Z-test, p<10−6), on average by 72% compared to wild type, demonstrating that FIGL1 is a barrier to CO formation also in wild type (Fig 2); (iii) while single fancm-1 mutants display a three-fold increase in genetic distances on average (p<10−6 and [24]), a six-fold increase is observed in the figl1-1 fancm-1 double mutant compared to wild type (p<10−6) on average on the six intervals tested, which is higher than either single mutant (p<10−6), showing that the effects of these mutations are multiplicative (Fig 2). This result shows that FIGL1 and FANCM act by two distinct mechanisms to limit crossover formation at meiosis. The net effect being multiplicative rather than additive further suggests that FIGL1 and FANCM act sequentially or synergistically at the same step to limit the flux of recombination intermediates toward CO formation.

Fig. 2. FIGL1 limits meiotic CO independently of FANCM.

Genetic distances (in cM) measured from tetrad analysis in a series of intervals across Arabidopsis genome: I2a and I2b are adjacent intervals on chromosome 2 and so on for the other couples of intervals. Error bars: SD. On all intervals all genotypes are significantly different from each other (Z-test, p<0.01). The figl1-1 fancm-1 plants are indistinguishable from wild type in terms of growth and fertility (57.5±6 seeds per fruit in figl1-1 fancm-1 (n = 13) and 55.2±6 in wild type (n = 24; T-Test p = 0.42)). Meiosis proceeds normally in this double mutant leading to the conclusion that a large increase in CO frequency does not cause any dramatic defects in chromosome segregation.

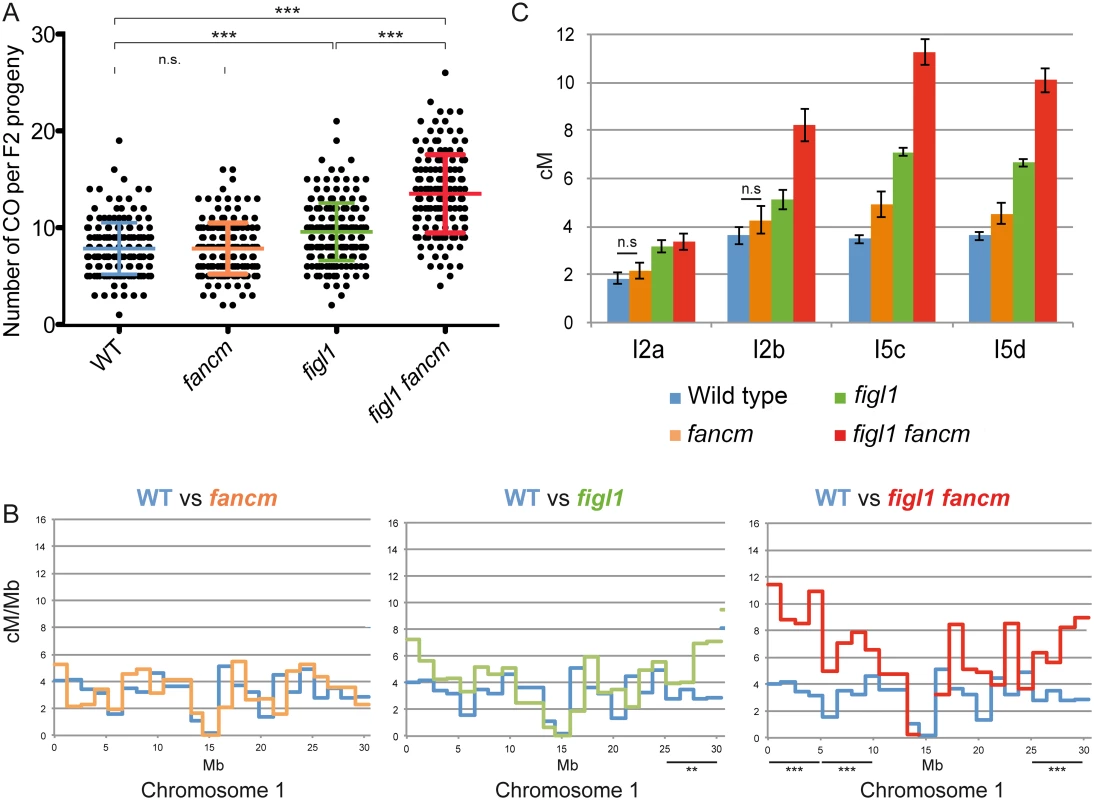

Genetic maps of figl1 reveal a marked increase in CO formation in distal regions of chromosomes

We analyzed the genome wide frequency and CO distribution using segregation of polymorphisms between different strains. While all alleles described above were identified in the Columbia-0 (Col-0) strain, we obtained mutant alleles in another genetic background by performing a suppressor screen of msh4 in another strain, Landsberg erecta (Ler) (S1 Table). The Ler figl1-12 allele displayed the same ability to restore bivalents of zmm mutants as its Col-0 counterparts (Fig 1). Genetic maps were obtained through segregation analysis of 91 markers (S2 Table) on F2 plants obtained by self-fertilization of figl1 (figl1-1/figl-12) and wild-type Col-0/Ler F1s. This showed a global increase of COs genome wide, with a 25% increase of observed crossover number per F2 plant in figl1 compared to wild type (Fig 3A; T-Test p<0,001). The increase is variable along chromosomes, with a more marked increase in the distal regions than close to centromeres: all ~5Mb intervals that individually show a significant increase compared to wild type are sub-telomeric (Fig 3B and S3 Fig). Conversely, the intervals spanning the centromeres, which have a low recombination frequency in wild type, remain similarly low in figl1.

Fig. 3. The effect of figl1 and fancm on recombination in hybrids.

A: CO count in each F2 progeny obtained from parent plants from Columbia-0/Landsberg (Col/Ler) F1 hybrids. Means and SD are indicated. n.s.: not significant; *** indicates significant difference, T-Test p<0,001. B: Recombination frequency (in cM/Mb) along chromosome I compared to wild type for each genotype. Difference in recombination frequency was tested along the genome on ~5Mb intervals (see methods). See also S5A Fig. C: Genetic distances (in cM) measured from tetrad analysis in a series of intervals, in Col/Ler F1 hybrids. All genotypes on all intervals are significantly different from wild type (Z-test, p<0.03), except when noted (n.s.: not significant). In addition, tetrad analyses were performed on F1 Col-0/Ler hybrid plants using FTLs. In the hybrid figl1 mutant, we observed a 79% average increase in CO frequency, on the four intervals tested, compared to the sister wild type controls (Fig 3C). This increase is similar to the one observed in the inbred Col-0 background on the same intervals, and to the observed increase with marker segregation analysis on the same region (S3 Fig). These increases are higher than the average increase genome wide (25%), likely because the FTL intervals used are positioned rather distally on the chromosomes. These genetic data confirm that FIGL1 is a barrier to CO formation in wild-type inbreds and hybrids.

FANCM mutation increases crossovers efficiently in inbreds but minimally in hybrids

The msh4 screen in a Ler background also led to the identification of several fancm mutants with a large increase in bivalent formation, including fancm-10 (S1 Table). Bivalent frequency in fancm-10 msh4 (Ler) was as high as in fancm-1 msh4 (Col-0) (S4A Fig), confirming that fancm is a bona fide suppressor of zmm in both Columbia and Landsberg backgrounds. As described above for figl1, we performed marker segregation analysis using the same set of 91 markers in F2 populations derived by self-pollination of fancm F1 hybrids. In contrast to the fancm inbred, the observed number of COs in fancm hybrids Col-0/Ler was the same as in the hybrid wild type (7.8 COs per cell; Fig 3A). The observation of CO distribution (Fig 3B and S3 Fig) did not reveal differences between fancm and wild type. Tetrad analysis recapitulated this observation with an average 200% increase when fancm is compared to wild type in Col-0 (this study and [24]) but only an average 22% increase in the Col-0/Ler F1s on the four intervals tested (ranging from no detected increase to a significant 42% increase p<10−8, Fig 3C). This suggests the anti-CO activity of FANCM, which is large in inbreds, is strongly diminished in hybrids.

Further lines of evidence support this conclusion. First, marker segregation analysis in a pure Col-0 background confirmed a strong effect of fancm in increasing COs (S4B Fig). Second, while fancm very efficiently restores bivalent formation of zmm mutants in Col-0, Ler, or Wassilewskija (Ws) inbred strains, it is not the case in both Col-0/Ler and Col-0/Ws F1 hybrids (S4A Fig). Finally, an independent study [36] showed that the effect of fancm-1 on increasing CO is also abolished in an F2 Col-0/Catania hybrid: when the tested interval was heterozygous Col-0/Cat, fancm-1 had no effect on CO frequencies in this experiment. These data confirm that the effect of fancm on increasing COs is strongly diminished in hybrid contexts.

figl1 and fancm have multiplicative effects on CO in hybrids

Tetrad analysis showed that the mutation of both FIGL1 and FANCM in a Col-0/Ler F1 led to an increase of CO frequency compared to wild type on the four intervals tested (Fig 3C), with a 2.5-fold increase on average. This is higher than either single mutant (1.8 and 1.2, respectively), showing that figl1 and fancm have multiplicative effects also in Col/Ler F1s. However, this increase is lower than what was observed when comparing figl1 fancm and wild type in inbred Col-0 strains (6 fold). This is likely due to fancm having a lesser increase in CO frequency in hybrids than in inbreds. Indeed there is the same effect of mutating figl1 in a fancm mutant either in hybrid or inbred (figl1 fancm vs. fancm: 1.96 and 2.03 average ratio, in Col-0/Ler and Col-0 respectively) whereas mutating fancm in figl1 mutant is much less effective in the hybrid than in the Col-0 inbred (figl1 fancm vs. figl1: 1.42 and 3.45 average ratio, in Col-0/Ler and Col-0 respectively). In the genome wide analysis, the observed number of COs per plant (Fig 3A) increased from 7.8 in WT to 13.5 in figl1 fancm (T-Test, p<10−4), which is higher than both single mutants (7.8 in fancm and 9.6 in figl1, T-Test, p<10−4). While we detected no effect of fancm on the number of COs genome-wide in the wild-type background, fancm had a significant effect in the figl1 background (13.5 vs. 9.6 COs, p<10−4). The increase in COs in figl1 fancm is significant in the distal regions, and not detectable close to centromeres (Fig 3B and S3 Fig). Increased COs close to centromeres have been reported to be associated with chromosome mis-segregation in budding yeast and humans [37–39]. We did not observe segregation defects in figl1 fancm, suggesting that only proximal extra-COs are detrimental for correct chromosome segregation. Altogether, these data showed that (i) FANCM is a more important anti-CO protein in Col-0 than in the hybrid, contrary to (ii) FIGL1 which is equally efficient in both contexts; (iii) FIGL1 and FANCM have multiplicative effects on limiting COs in F1 hybrids, as in inbreds.

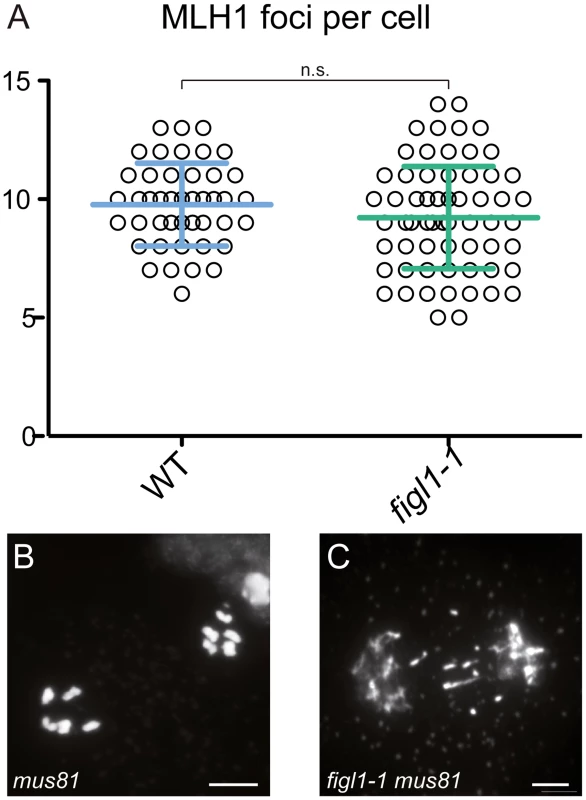

FIGL1 antagonizes MUS81-dependent crossover formation

We then investigated the origin of the figl1 extra-COs. Mutating SPO11-1 in figl1-1 abolished bivalent formation (Fig 1), showing that CO formation in figl1-1 arises from SPO11-dependent DSBs. Two classes of COs coexist in Arabidopsis: one dependent on ZMM proteins, marked by the MLH1 protein and subject to interference; and one involving the endonuclease MUS81 and insensitive to interference [22,40,41]. Immuno-labeling of MLH1, which specifically marks designated sites of class I COs, did not reveal any differences between figl1-1 and wild type (Fig 4) suggesting that the extra-COs observed in figl1-1 are not class I crossovers. Corroborating this, the strength of interference measured genetically was weaker in figl1-1 compared to WT on all intervals tested (S2D Fig), suggesting that extra-COs in figl1 are not sensitive to interference. Moreover, in the figl1-1 mus81 double mutant, entangled meiotic chromosomes and sterility were observed (Fig 4). This is not observed in either single mutant, showing that MUS81 becomes essential for the proper repair of recombination intermediates in figl1-1. We thus propose that FIGL1, similar to FANCM [24], prevents the formation or the persistence of intermediates that require MUS81 for repair, and whose resolution leads to extra-CO formation (without affecting the number of class I COs). Contrary to fancm however, no growth or developmental defect was observed when FIGL1 was mutated in a mus81 background, indicating that the role of FIGL1 in antagonizing the MUS81 pathway may be specific to meiosis. The additional meiotic COs produced in the absence of FIGL1 are likely dependent on MUS81, but we cannot exclude that other—unidentified—activities contribute to the formation of these COs.

Fig. 4. FIGL1 limits MUS81-dependent CO formation.

A: MLH1 foci number is unchanged in figl1-1 compared to wild type. B-C: Anaphase I in mus81 (B) and figl1-1 mus81 double mutant (C), the latter displays chromosome fragments indicative of unrepaired recombination intermediates. Scale bar = 5μm. Synaptonemal complex length is not affected in fancm or figl1

Synapsis, the intimate association of homologous chromosomes along their entire length observed at pachytene, was not different in figl1-1, fancm and wild type, as observed by immuno-localization of the axial element and transverse filament of the synaptonemal complex (SC), ASY1 and ZYP1 respectively (Figs 5 and 6 and S5 Fig). ZYP1-marked SC length in both mutants was not different from wild type (figl1 113.4 μm [n = 4] and fancm 125.6 μm [n = 32], vs. 125.5 μm [n = 33] in wild type). This shows that largely increasing the frequency of non-interfering COs does not affect the SC length. SC length has been shown to be longer in male than in female Arabidopsis meiosis, and the male genetic map length is also greater in male than in female [42,43]. Such correlated variations in SC length and CO number were also reported between male and female in various species, among individuals in the same species, and among meiocytes in a single organism (discussed in [42]). If CO number and SC length are linked, one attractive hypothesis would be that these fluctuations may only depend upon the ZMM COs, while increasing class II COs would have no effect.

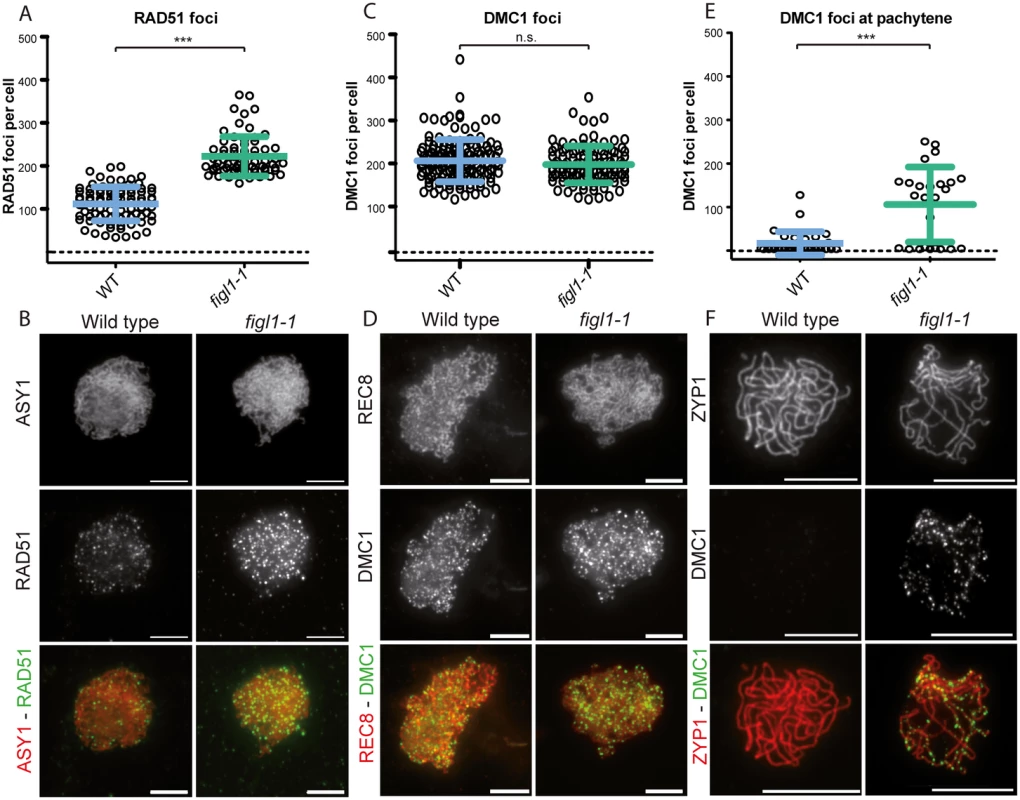

Fig. 5. The dynamics of DMC1 and RAD51 are modified in figl1.

A and C: Number of RAD51 and DMC1 (respectively) foci count per positive cell throughout prophase in both wild type and figl1-1 mutant. n.s.: not significant; *** T-test p<0,001. B: Illustration of RAD51immuno-localization at leptotene in wild type and figl1-1 mutant, with the axis protein ASY1used as a counterstain. D: Illustration of DMC1immuno-localization at leptotene in wild type and figl1-1 mutant, with the REC8 cohesin used as a counterstain. The same exposure and treatment parameters have been applied to all images of both wild type and figl1-1. E: DMC1 foci count in pachytene cells (*** T-test p<0,001). ZYP1 staining was used as a marker for full synapsis, indicative of the pachytene stage. F: Illustration of DMC1 immuno-localization at pachytene, with ZYP1 as a counterstain. Fig. 6. FIGL1 genetically interacts with SDS.

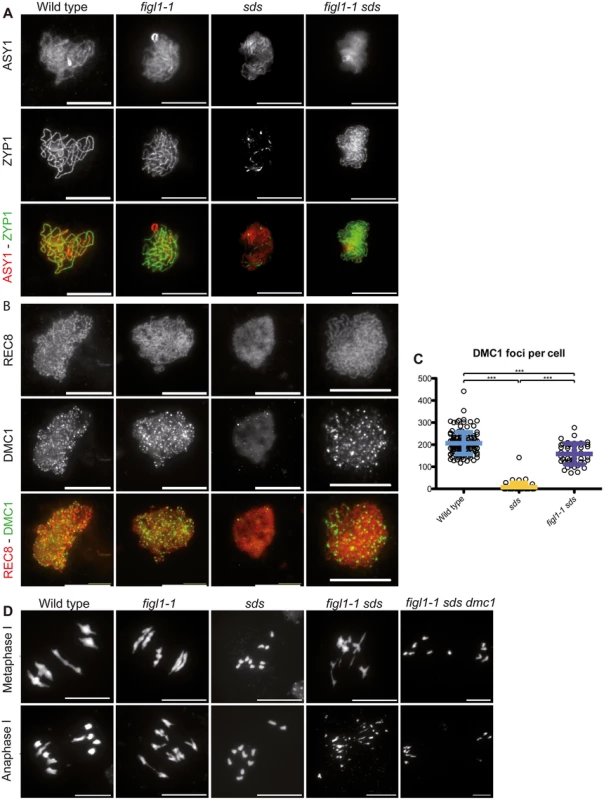

A: ZYP1 immuno-localization as a marker of synapsis, with the chromosome axis protein ASY1 used as a counterstain, showing that synapsis is restored in figl1-1 sds double mutant compared to sds single mutant. B: DMC1 immuno-localization with the REC8 cohesin used as a counterstain showing that DMC1 foci formation is restored in figl1-1 sds compared to sds. C: Quantification. D: DAPI staining of meiotic chromosome spreads at metaphase I (top) and anaphase I (bottom). While sds mutant meiosis displays 10 univalents, figl1-1 sds meiosis presents bivalent like structures at metaphase I and chromosome fragments at anaphase I, indicative of unrepaired recombination intermediates. Bivalent and fragmentation are not observed in figl1-1 sds dmc1. FIGL1 regulates RAD51 and DMC1 foci dynamics

We performed co-immuno-localization experiments of the axis proteins ASY1 and RAD51, as well as the REC8 cohesin and DMC1, in both wild type and figl1 (Fig 5). In wild-type leptotene/zygotene cells we observed a mean number of 206 DMC1 foci and 111 RAD51 foci (Fig 5). In figl1 sister plants, a sharp two-fold increase of the number of RAD51 foci was observed (p<10−3), while the number of DMC1 foci was unchanged (p = 0.14). This shows that FIGL1 limits the number of RAD51 foci, but not of DMC1 foci in wild type. The increase of RAD51 foci number could suggest that the number of DSBs is increased in figl1 compared to wild type, but the absence of increase of DMC1 foci number argues against this interpretation. We thus favor the interpretation that the dynamics of RAD51 foci are modified, either being associated with a higher proportion of DSBs or/and persisting longer on chromosomes. We then performed double immuno-localization of RAD51 and DMC1 in wild type and figl1 (S6 Fig). In wild type, all DMC1 positive cells were also positive for RAD51 foci (n = 17), while only 36% RAD51-positive cells were also positive for DMC1 foci (n = 59). This suggests that, in wild type, DMC1 is present as foci on chromosomes in a shorter period than RAD51. In figl1, like in wild type, all DMC1 positive cells were positive for RAD51 foci (n = 40), however 95% of RAD51-positive cells were also showing DMC1 foci (n = 63). In addition, co-immuno-localization of ZYP1 and DMC1 showed that DMC1 foci persisted at pachytene cells in figl1 but not in wild type (Fig 5E and 5F). Thus, the dynamics of DMC1 foci with respect to RAD51 and synapsis appears to be modified in figl1 with a longer window of presence.

The plant-specific cyclin SDS is required for DMC1 focus formation/stabilization [12,13]. While DMC1 focus formation is virtually abolished in sds, in figl1-1 sds the formation of DMC1 foci was restored to ~70% of wild-type level (Fig 6A and 6B). This shows that FIGL limits DMC1 foci formation in sds or accelerates turnover of DMC1 complexes in sds, and that SDS promotes DMC1 foci formation in both wild type and figl1. Thus SDS and FIGL1 have antagonistic, direct or indirect, roles toward DMC1 foci formation.

Synapsis is strictly dependent on DSB formation and inter-homolog strand invasion in Arabidopsis [16,44]. Accordingly, no synapsis is observed in the absence of either of the strand exchange promoting proteins DMC1 or RAD51. Similarly, no synapsis is observed in sds suggesting that inter-homolog strand invasion is also abolished in this mutant [12,13,45–47]. In contrast, synapsis was restored in figl1 sds (Fig 6C and S7 Fig), showing that FIGL1 prevents synapsis, and thus presumably inter-homolog strand-invasion, in sds. No synapsis was observed in figl1 dmc1, figl1 rad51, figl1 sds dmc1, or figl1 sds rad51 (S7 Fig). DMC1 and RAD51 are thus essential for synapsis in all contexts. This suggests that FIGL1 limits RAD51/DMC1 mediated inter-homolog strand invasion, which is antagonistic to the function of SDS. Mutation of FANCM did not restore synapsis or bivalent formation in sds (S7 Fig), confirming that FIGL1 and FANCM act through distinct mechanisms.

In rad51, massive chromosome fragmentation occurs at metaphase/anaphase I, indicative of failed DSB repair. In contrast DSB repair is efficient in dmc1 and sds, presumably using the sister chromatid as a template. This repair is RAD51 dependent, as fragmentation occurs in dmc1 rad51 and sds rad51 [12,13,45,46]. In figl1 sds, the restoration of synapsis is followed by chromosome fragmentation. Both synapsis and fragmentation were absent in the figl1 sds dmc1 triple mutant (Fig 6D). Thus, DMC1 produces intermediates that promote synapsis and these intermediates in the absence of both FIGL1 and SDS, fail to be repaired. This suggests that DMC1/RAD51 promotes inter-homolog interactions, SDS being a helper in both invasion and repair on the homolog (but not on the sister), while FIGL1 antagonizes inter-homolog interactions. The restoration of DSB repair in figl1 sds dmc1 compared to figl1 sds, and the restoration of DMC1 foci in fidg sds compared to sds, suggest the possibility that FIGL1 promotes DMC1 turnover, this turnover being required for efficient repair under certain circumstances (e.g. in sds). Persistence of DMC1 was also shown to induce DSB repair deficiency in certain contexts in both yeast and Arabidopsis [7,9,48].

Discussion

FIGL1 and FANCM limit class II COs by distinct mechanisms

Mechanisms that limit COs at meiosis are only starting to be deciphered. Here we identify FIGL1 as a meiotic anti-CO factor. In figl1, extra COs have class II CO characteristics. Indeed, they do not display interference and are not marked by MLH1. Moreover, MUS81, which is involved in class II CO formation, becomes essential for DSB repair in figl1. Thus, FIGL1 limits class II CO formation, without affecting class I COs, similar to the anti-CO helicase FANCM [24]. However, FIGL1 and FANCM mutations have multiplicative effects on CO formation suggesting that FIGL1 and FANCM mutations fuel the class II CO pathway by two distinct, sequential, mechanisms (see below).

The effect of mutating fancm on elevating CO frequency is quite pronounced in inbred lines, but negligible in hybrids. In contrast, increases in CO frequency in figl1 are similar in inbreds and hybrids. In both inbreds and hybrids, the strongest effect is always observed in the double mutant. Thus, the manipulation of both FIGL1 and FANCM is a promising tool to increase CO formation in plant breeding programs, as COs are one of the principal driving forces in generating new plant varieties but occur at low rates naturally [49–51]. The shrinkage of the anti-CO effect of FANCM in hybrids could be caused by the sequence divergence between the parental strains. Ziolkowski et al. [36] independently observed a similar result of heterozygosity drastically reducing the fancm-1 effect in a Col-0/Catania-1 hybrid. They further showed that the large increase in CO frequency in fancm-1 depends on the homozygous/heterozygous status of the tested interval, independently of the status of the rest of the chromosome, suggesting the heterozygosity acts in cis and not in trans to prevent COs that arise in fancm-1. Ziolkowski and colleagues also draw from their experiments the conclusion that non-interfering (class II) repair is inefficient in heterozygous regions. However, the increase in class II COs in the figl1 mutant is not affected by the hybrid status. It would therefore indicate that class II COs can occur efficiently in heterozygous regions of the genome, at least in absence of FIGL1. The reason for fancm loss of effect in heterozygous regions could arise from mismatches due to heterozygosity that may lead to the production of fewer, or less stable, DNA recombination intermediates [52] on which the FANCM helicase could act [53]. However, the average polymorphism between Col-0 and Ler or Ct-1 is only 1 SNP every ~200pb [54,55] while the gene conversion tracks associated with CO and NCO are estimated to ~400 and less than 50 base pairs, respectively [56,57]. It appears unlikely that so few mismatches, and in many cases none, per recombination intermediate could have such a drastic effect. There may therefore be additional sequence - or non sequence-based mechanisms that impair the anti-CO activity of FANCM in hybrids. The observation that the figl1 mutation effect on recombination is similar in hybrids than in inbred lines supports the conclusion that FANCM and FIGL1 acts through distinct mechanisms to limit meiotic CO formation.

A model for the CO-limiting mechanism of FIGL1

Our data show that FIGL1 regulates the invasion step of meiotic homologous recombination: (i) Mutation of FIGL1 increases the number of RAD51 foci, (ii) modifies the dynamics of DMC1 and (iii) restores DMC1 foci formation and DMC1-mediated homologous interactions (synapsis) in sds. In contrast to figl1, fancm does not restore homologous interactions in sds, supporting the conclusion that FIGL1 and FANCM regulate HR by different mechanisms. One possibility is that FIGL1 regulates the choice between the homologous and the sister chromatid as repair template. In such a model, the frequency of inter-homologous invasions would be increased at the expense of inter-sister invasions in the figl1 mutant, leading to more COs. However, several arguments disfavor this simple hypothesis. First, the number of DMC1 and RAD51 foci in wild-type Arabidopsis suggests a high number of DSBs, therefore the number of inter-homologue invasions—that cannot be directly estimated currently—probably already outnumbers COs in wild type, making it hard to believe that a further excess would increase CO frequency. Moreover, MUS81 is essential for completion of repair in the figl1 background but not in wild type. This suggests that the recombination intermediates produced in the figl1 mutant differ from those in wild type not simply in their number but in their nature. We therefore propose that FIGL1 prevents the formation of aberrant joint molecules through the regulation of strand invasion intermediates, whose resolution by MUS81 (and possibly other factors) leads to extra-CO formation. FIGL1 could limit the over-extension of the D-loop, and/or prevent the formation of multi-joint molecules by preventing that both ends of the resected DSB interact with different templates and/or by limiting multiple rounds of invasions [58–60].

The multiplicative effect on CO frequency of mutating both FIGL1 and FANCM suggests that they act sequentially. We thus further propose that FIGL1 limits the formation of joints molecules by regulating DMC1-dependant strand invasion and that these joint molecules when formed can then be disrupted by the FANCM helicase. The absence of both FIGL1 and FANCM would lead to a synergistic accumulation of substrates for MUS81, and possibly other factors, accounting for the multiplicative effect on CO frequency.

Alternatively, human FIGL1 was shown to interact with both RAD51 and the KIAA0146/SPIDR protein [32], the latter in turn interacting directly with the BLM helicase [61]. Another, not exclusive, functional hypothesis for the FIGL1 meiotic anti-CO function is that FIGL1 could facilitate the recruitment of the BLM homologues, RECQ4A and RECQ4B, which have been recently shown to also limit meiotic CO in Arabidopsis [62]. It will therefore be interesting to explore the functional relationship between FIGL1 and RECQ4s at meiosis.

FIGL1 is an AAA-ATPase (ATPases Associated with diverse cellular Activities) [63,64], a family of unfoldase proteins [65] involved in the disruption of protein complexes as different as microtubules or chromosome axis components [66,67]. FIGL1 is the only member of the FIDGETIN sub-family to be widely conserved (S1C Fig), contrary to FIDGETIN and FIGL2 that are present only in vertebrates. Arguing for a conserved role of FIGL1 at meiosis, the mouse FIGL1 is highly expressed in spermatocytes at meiotic prophase I [33]. Human and C. elegans FIGL1 orthologs have been shown to form a hexameric ring oligomer, which is the classical conformation for AAA-ATPases [65,67,68]. Several missense mutations identified in our screen fall into the two conserved domains, the AAA-ATPase domain and the VPS4 domain (S1B Fig) [65,69,70] indicating that ATPase activity and oligomerization of FIGL1 are important for its anti-CO activity. Here we show that RAD51 and DMC1 focus formation and/or dynamics are regulated by FIGL1. Of interest, the human FIGL1 ortholog has been shown to directly interact with RAD51 in somatic cells [32]. The FRBD domain (the FIGNL1 RAD51 Binding Domain) is necessary for this interaction, and this domain is conserved in Arabidopsis FIGL1 (Fig 1 and S1B Fig). An attractive model would be that FIGL1 could directly promote disassembly of the RAD51 and/or DMC1 filaments, preventing unregulated (multi-) strand invasion, and/or the accumulation of DMC1/RAD51 trapped intermediates [71]. However, it is also possible that FIGL1 unfolds another target to regulate CO formation. Such alternative targets could be chromosome axis proteins, e.g. ASY1 or ASY3, which direct recombination towards the homologue [72,73]. This would be reminiscent of the role of another AAA-ATPase that regulates recombination in S. cerevisiae, Pch2 that targets the ASY1 homologue Hop1 [67].

Materials and Methods

Genetic resources

The lines used in this study were: spo11-1-3 (N646172) [74], dmc1-3 (N871769)[75], sds-2 (N806294) [13], rad51-1 [47], zip4-1 (EJD21)[76], zip4-2 (N568052) [76], shoc1-1 (N557589)[77], msh5-2 (N526553) [78], mus81-2 (N607515) [22], fancm-1 [24], hei10-2 (N514624) [79]. Tetrad analysis lines were: I2ab (FTL1506/FTL1524/FTL965/qrt1-2), I3bc (FTL1500/FTL3115/FTL1371/ qrt1-2) and I5cd (FTL1143U/FTL1963U/FTL2450L/ qrt1-2) from G. Copenhaver [35]. Atzip4(s)5 (figl1-1) was sequenced using Illumina technology (The Genome Analysis Center, Norwich UK). Mutations were identified through the MutDetect pipeline [31].

Cytological techniques

Meiotic chromosome spreads have been performed as described previously [80]. Immuno-localizations of MLH1 were performed as described in [40], RAD51, DMC1, ASY1 and ZYP1 as in [81,82]. Observations were made using a ZEISS AxioObserver microscope.

Cloning and transient FIGL1 expression in N. benthamiana

The FIGL1 open reading frame was amplified on Col-0 cDNAs with DNA primers (GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTGTAAAGGAATGTGTGGGTCG and GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGAGGCTTAAACTACCAAACTG) and subsequently cloned using the Gateway technology (Invitrogen) into destination vectors pGWB5 and pGWB6 [83] where FIGL1 sequence is in fusion with a GFP protein,. Infiltrations of Nicotiana benthamiana leafs with Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58C1(pMP90) bearing the construction were performed as in [84]

Fluorescent-Tagged Lines (FTL) tetrad analysis

Tetrad slides were prepared as in [35] and counting was performed through an automated detection of tetrads using a pipeline developed on the Metafer Slide Scanning Platform (http://www.metasystems-international.com/metafer). For each tetrad, classification (A to L) was double checked manually. Genetic sizes of each interval was calculated using the Perkins equation [85]: D = 100 x (Tetratype frequency + 6 x Non-Parental-Ditype frequency)/2 in cM. (see http://www.molbio.uoregon.edu/~fstahl for details)

The Interference Ratio (IR) was calculated as in [35,86]. For two adjacent intervals I1 and I2, two populations of tetrads are considered: those with at least one CO in I2 and those without any CO in I2. The genetic size of I1 is then calculated for these two populations using the Perkins equation (above), namely D1 (I1 with CO in I2) and D2 (I1 without a CO in I2). The IR is thus defined as IR = D1/D2. If the genetic size of I1 is lowered by the presence of a CO in I2, IR<1 and interference is detected. If not, IR is close to 1 and no interference is detected. A Chi-square tests the null hypothesis (H0: D1 = D2.) (S3D Fig).

The coefficient of interference (CoC) was calculated as in [87]. The CoC compares the observed frequency of double CO compared to the expected frequency of double CO without interference. The observed frequency is defined by fo(2CO) = frequency of tetrads having at least one CO in I1 and at least one CO in I2 (classes D, E, F, G, J, K, L). The expected frequency is obtained by the product of fe(COI1) and fe(COI2); where fe(COI1) is defined as the frequency of tetrads having at least one CO in I1 (classes C, D E, F, G, I, J, K, L), and fe(COI2) as the frequency of tetrads having at least one CO in I2 (classes B, D E, F, G, H, J, K, L). The CoC is thus defined as CoC = fo(2CO) / [fe(COI1) x fe(COI2)]. If the observed frequency of double CO is lower than the expected frequency, CoC<1 and interference is detected. If not, CoC is close to 1 and no interference is detected. A Chi-square tests the null hypothesis (H0: fo(2CO) = fe(COI1) x fe(COI2)) (S3D Fig).

Marker segregation and tetrad analysis in hybrids

Hybrid lines were obtained through the crossing of fancm-1 figl1-1 double mutant in the Columbia-0 background (bearing the tetrad analysis markers, see above, and the qrt1-2 mutation) with a fancm-10 figl1-12 double heterozygous mutant in the Landsberg background bearing the qrt1-1 mutation [88]. The F1 plants were heterozygous for the tetrad analysis markers and were used to obtain results of Fig 3C. Seeds from the self-pollination of double heterozygote (non-mutant control), figl1, fancm and figl1 fancm plants were sown. DNA extractions were made as in [43] on 21-day-old rosettes.

96 KASPar markers were designed according to their genomic position with an average distance between two markers of 1.5Mb (S2 Table). Genotyping was performed using the KASPAR technology at Plateforme Gentyane, Clermont-Ferrand, France. Genotyping data were analyzed with Fluidigm software (http://www.fluidigm.com). 91 markers gave robust genotyping results and were further kept for analysis on a total of 174 wild type, 223 figl1, 174 fancm and 166 figl1 fancm plants. Results were exported to MapDisto [89]. Genetic maps were computed with Kosambi parameters [90] for each chromosome (in cM, Fig 3B and S3 Fig).

The number of CO per F2 plant was retrieved from the genotyping data. These numbers were then compared between genotypes by a bilateral T-Test (p values are indicated in the main text). To compare recombination along chromosomes, the number of recombinant chromatids was retrieved for each interval (of about 1.5Mb). Super-intervals were obtained by merging adjacent intervals to reach the critical size of ~5Mb. Recombination data from single intervals were then pooled for each super-interval. Chi-square tests were realized to compare wildtype and mutant data. Multiple chi-square test correction was realised using the Benjamini—Hochberg procedure [91]: ** indicates a significant chi-square test with a probability of 5% of false discovery rate, *** indicates a significant chi-square test with a probability of 1% of false discovery rate.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. Goldfarb T, Lichten M (2010) Frequent and efficient use of the sister chromatid for DNA double-strand break repair during budding yeast meiosis. PLoS Biol 8: e1000520. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000520 20976044

2. Zickler D, Kleckner NE (1999) Meiotic chromosomes: integrating structure and function. Annu Rev Genet 33 : 603–754. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.603 10690419

3. De Massy B (2013) Initiation of meiotic recombination: how and where? Conservation and specificities among eukaryotes. Annu Rev Genet 47 : 563–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155423 24050176

4. Whitby MC (2005) Making crossovers during meiosis. Biochem Soc Trans 33 : 1451–1455. 16246144

5. Lao JP, Hunter N (2010) Trying to avoid your sister. PLoS Biol 8: e1000519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000519 20976046

6. Cloud V, Chan Y-L, Grubb J, Budke B, Bishop DK (2012) Rad51 Is an accessory factor for Dmc1-Mediated joint molecule formation during meiosis. Science 337 : 1222–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.1219379 22955832

7. Hong S, Sung Y, Yu M, Lee M, Kleckner N, et al. (2013) The logic and mechanism of homologous recombination partner choice. Mol Cell 51 : 440–453. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.008 23973374

8. Kurzbauer M-T, Uanschou C, Chen D, Schlögelhofer P (2012) The recombinases DMC1 and RAD51 are functionally and spatially separated during meiosis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24 : 2058–2070. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.098459 22589466

9. Uanschou C, Ronceret A, Von Harder M, De Muyt A, Vezon D, et al. (2013) Sufficient amounts of functional HOP2/MND1 complex promote interhomolog DNA repair but are dispensable for intersister DNA repair during meiosis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25 : 4924–4940. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.118521 24363313

10. Da Ines O, Degroote F, Goubely C, Amiard S, Gallego ME, et al. (2013) Meiotic recombination in Arabidopsis Is catalysed by DMC1, with RAD51 playing a supporting role. PLoS Genet 9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003787

11. Humphryes N, Hochwagen A (2014) A non-sister act: Recombination template choice during meiosis. Exp Cell Res. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.08.024

12. Azumi Y, Liu D, Zhao D, Li W, Wang G, et al. (2002) Homolog interaction during meiotic prophase I in Arabidopsis requires the SOLO DANCERS gene encoding a novel cyclin-like protein. EMBO J 21 : 3081–3095. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf285 12065421

13. De Muyt A, Pereira L, Vezon D, Chelysheva L, Gendrot G, et al. (2009) A high throughput genetic screen identifies new early meiotic recombination functions in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet 5: e1000654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000654 19763177

14. Allers T, Lichten M (2001) Differential timing and control of noncrossover and crossover recombination during meiosis. Cell 106 : 47–57. 11461701

15. Hollingsworth NM, Brill SJ (2004) The Mus81 solution to resolution: generating meiotic crossovers without Holliday junctions. Genes Dev 18 : 117–125. doi: 10.1101/gad.1165904 14752007

16. Osman K, Higgins JD, Sanchez-Moran E, Armstrong SJ, Franklin FCH (2011) Pathways to meiotic recombination in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 190 : 523–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03665.x 21366595

17. Lynn A, Soucek R, Börner GV (2007) ZMM proteins during meiosis: crossover artists at work. Chromosome Res 15 : 591–605. doi: 10.1007/s10577-007-1150-1 17674148

18. Zakharyevich K, Tang S, Ma Y, Hunter N (2012) Delineation of joint molecule resolution pathways in meiosis identifies a crossover-specific resolvase. Cell 149 : 334–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.023 22500800

19. Berchowitz LE, Copenhaver GP (2010) Genetic interference: don’t stand so close to me. Curr Genomics 11 : 91–102. doi: 10.2174/138920210790886835 20885817

20. Anderson LK, Lohmiller LD, Tang X, Hammond DB, Javernick L, et al. (2014) Combined fluorescent and electron microscopic imaging unveils the specific properties of two classes of meiotic crossovers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406846111

21. Higgins JD, Buckling EF, Franklin FCH, Jones GH (2008) Expression and functional analysis of AtMUS81 in Arabidopsis meiosis reveals a role in the second pathway of crossing-over. Plant J 54 : 152–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03403.x 18182028

22. Berchowitz LE, Francis KE, Bey AL, Copenhaver GP (2007) The role of AtMUS81 in interference-insensitive crossovers in A. thaliana. PLoS Genet 3: e132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030132 17696612

23. Mercier R, Mézard C, Jenczewski E, Macaisne N, Grelon M (2014) The molecular biology of meiosis in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 66 : 1–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-035923 25423078

24. Crismani W, Girard C, Froger N, Pradillo M, Santos JL, et al. (2012) FANCM limits meiotic crossovers. Science 336 : 1588–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.1220381 22723424

25. Youds JL, Mets DG, McIlwraith MJ, Martin JS, Ward JD, et al. (2010) RTEL-1 enforces meiotic crossover interference and homeostasis. Science 327 : 1254–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.1183112 20203049

26. Lorenz A, Osman F, Sun W, Nandi S, Steinacher R, et al. (2012) The fission yeast FANCM ortholog directs non-crossover recombination during meiosis. Science 336 : 1585–1588. doi: 10.1126/science.1220111 22723423

27. De Muyt A, Jessop L, Kolar E, Sourirajan A, Chen J, et al. (2012) BLM helicase ortholog Sgs1 Is a central regulator of meiotic recombination intermediate metabolism. Mol Cell 46 : 43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.02.020 22500736

28. Rockmill B, Fung JC, Branda SS, Roeder GS (2003) The Sgs1 helicase regulates chromosome synapsis and meiotic crossing over. Curr Biol 13 : 1954–1962. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.059 14614820

29. Tang S, Wu MKY, Zhang R, Hunter N (2015) Pervasive and essential roles of the Top3-Rmi1 decatenase orchestrate recombination and facilitate chromosome segregation in meiosis. Mol Cell 57 : 607–621. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.021 25699709

30. Kaur H, De Muyt A, Lichten M (2015) Top3-Rmi1 DNA single-strand decatenase is integral to the formation and resolution of meiotic recombination intermediates. Mol Cell 57 : 583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.020 25699707

31. Girard C, Crismani W, Froger N, Mazel J, Lemhemdi A, et al. (2014) FANCM-associated proteins MHF1 and MHF2, but not the other Fanconi anemia factors, limit meiotic crossovers. Nucleic Acids Res 42 : 9087–9095. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku614 25038251

32. Yuan J, Chen J (2013) FIGNL1-containing protein complex is required for efficient homologous recombination repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220662110

33. L′Hôte D, Vatin M, Auer J, Castille J, Passet B, et al. (2011) Fidgetin-like1 is a strong candidate for a dynamic impairment of male meiosis leading to reduced testis weight in mice. PLoS One 6: e27582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027582 22110678

34. Wu L, Hickson ID (2003) The Bloom’s syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature 426 : 870–874. doi: 10.1038/nature02253 14685245

35. Berchowitz LE, Copenhaver GP (2008) Fluorescent Arabidopsis tetrads: a visual assay for quickly developing large crossover and crossover interference data sets. Nat Protoc 3 : 41–50. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.491 18193020

36. Ziolkowski PA, Berchowitz LE, Lambing C, Yelina NE, Zhao X, et al. (2015) Juxtaposition of heterozygosity and homozygosity during meiosis causes reciprocal crossover remodeling via interference. eLife 4. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03708

37. Rockmill B, Voelkel-Meiman K, Roeder GS (2006) Centromere-proximal crossovers are associated with precocious separation of sister chromatids during meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 174 : 1745–1754. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.058933 17028345

38. Ghosh S, Feingold E, Dey SK (2009) Etiology of Down syndrome: Evidence for consistent association among altered meiotic recombination, nondisjunction, and maternal age across populations. Am J Med Genet A 149A: 1415–1420. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32932 19533770

39. Oliver TR, Feingold E, Yu K, Cheung V, Tinker S, et al. (2008) New insights into human nondisjunction of chromosome 21 in oocytes. PLoS Genet 4: e1000033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000033 18369452

40. Chelysheva L, Grandont L, Vrielynck N, le Guin S, Mercier R, et al. (2010) An easy protocol for studying chromatin and recombination protein dynamics during Arabidopsis thaliana meiosis: immunodetection of cohesins, histones and MLH1. Cytogenet Genome Res 129 : 143–153. doi: 10.1159/000314096 20628250

41. Mercier R, Jolivet S, Vezon D, Huppe E, Chelysheva L, et al. (2005) Two meiotic crossover classes cohabit in Arabidopsis: one is dependent on MER3,whereas the other one is not. Curr Biol 15 : 692–701. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.056 15854901

42. Drouaud J, Mercier R, Chelysheva L, Bérard A, Falque M, et al. (2007) Sex-specific crossover distributions and variations in interference level along Arabidopsis thaliana chromosome 4. PLoS Genet 3: e106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030106 17604455

43. Giraut L, Falque M, Drouaud J, Pereira L, Martin OC, et al. (2011) Genome-wide crossover distribution in Arabidopsis thaliana meiosis reveals sex-specific patterns along chromosomes. PLoS Genet 7: e1002354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002354 22072983

44. Mercier R, Grelon M (2008) Meiosis in plants: ten years of gene discovery. Cytogenet Genome Res 120 : 281–290. doi: 10.1159/000121077 18504357

45. Couteau F, Belzile F, Horlow C, Grandjean O, Vezon D, et al. (1999) Random chromosome segregation without meiotic arrest in both male and female meiocytes of a dmc1 mutant of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 11 : 1623–1634. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.9.1623 10488231

46. Vignard J, Siwiec T, Chelysheva L, Vrielynck N, Gonord F, et al. (2007) The interplay of RecA-related proteins and the MND1-HOP2 complex during meiosis in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet 3 : 1894–1906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030176 17937504

47. Li W, Chen C, Markmann-Mulisch U, Timofejeva L, Schmelzer E, et al. (2004) The Arabidopsis AtRAD51 gene is dispensable for vegetative development but required for meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 10596–10601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404110101 15249667

48. Lao JP, Cloud V, Huang CC, Grubb J, Thacker D, et al. (2013) Meiotic crossover control by concerted action of Rad51-Dmc1 in homolog template bias and robust homeostatic regulation. PLoS Genet 9: e1003978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003978 24367271

49. Crismani W, Girard C, Mercier R (2013) Tinkering with meiosis. J Exp Bot 64 : 55–65. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers314 23136169

50. Henderson IR (2012) Control of meiotic recombination frequency in plant genomes. Curr Opin Plant Biol 15 : 556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.09.002 23017241

51. Wijnker E, de Jong H (2008) Managing meiotic recombination in plant breeding. Trends Plant Sci 13 : 640–646. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.09.004 18948054

52. Evans E, Alani EE (2000) Roles for mismatch repair factors in regulating genetic recombination. Mol Cell Biol 20 : 7839–7844. 11027255

53. Whitby MC (2010) The FANCM family of DNA helicases/translocases. DNA Repair 9 : 224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.12.012 20117061

54. Nordborg M, Hu TT, Ishino Y, Jhaveri J, Toomajian C, et al. (2005) The pattern of polymorphism in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Biol 3: e196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030196 15907155

55. Gan X, Stegle O, Behr J, Steffen JG, Drewe P, et al. (2011) Multiple reference genomes and transcriptomes for Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 477 : 419–423. doi: 10.1038/nature10414 21874022

56. Wijnker E, Velikkakam James G, Ding J, Becker F, Klasen JR, et al. (2013) The genomic landscape of meiotic crossovers and gene conversions in Arabidopsis thaliana. Elife 2: e01426. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01426 24347547

57. Drouaud J, Khademian H, Giraut L, Zanni V, Bellalou S, et al. (2013) Contrasted patterns of crossover and non-crossover at Arabidopsis thaliana meiotic recombination hotspots. PLoS Genet 9: e1003922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003922 24244190

58. Oh SD, Lao JP, Taylor AF, Smith GR, Hunter N (2008) RecQ helicase, Sgs1, and XPF family endonuclease, Mus81-Mms4, resolve aberrant joint molecules during meiotic recombination. Mol Cell 31 : 324–336. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.006 18691965

59. Jessop L, Lichten M (2008) Mus81/Mms4 endonuclease and Sgs1 helicase collaborate to ensure proper recombination intermediate metabolism during meiosis. Mol Cell 31 : 313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.021 18691964

60. Oh SD, Lao JP, Hwang PY-H, Taylor AF, Smith GR, et al. (2007) BLM ortholog, Sgs1, prevents aberrant crossing-over by suppressing formation of multichromatid joint molecules. Cell 130 : 259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.035 17662941

61. Wan L, Han J, Liu T, Dong S, Xie F, et al. (2013) Scaffolding protein SPIDR/KIAA0146 connects the Bloom syndrome helicase with homologous recombination repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 : 10646–10651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220921110 23509288

62. Séguéla-Arnaud M, Crismani W, Larchevêque C, Mazel J, Froger N, et al. (2015) Multiple mechanisms limit meiotic crossovers: TOP3α and two BLM homologs antagonize crossovers in parallel to FANCM. Proc Natl Acad Sci: 201423107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423107112

63. Beyer a (1997) Sequence analysis of the AAA protein family. Protein Sci 6 : 2043–2058. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061001 9336829

64. Frickey T, Lupas A (2004) Phylogenetic analysis of AAA proteins. J Struct Biol 146 : 2–10. 15037233

65. Vale RD (2000) AAA proteins. Lords of the ring. J Cell Biol 150: F13–F19. 10893253

66. McNally FJ, Vale RD (1993) Identification of katanin, an ATPase that severs and disassembles stable microtubules. Cell 75 : 419–429. 8221885

67. Chen C, Jomaa A, Ortega J, Alani EE (2014) Pch2 is a hexameric ring ATPase that remodels the chromosome axis protein Hop1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: E44–E53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310755111 24367111

68. Peng W, Lin Z, Li W, Lu J, Shen Y, et al. (2013) Structural insights into the unusually strong ATPase activity of the AAA domain of the Caenorhabditis elegans fidgetin-like 1 (FIGL-1) protein. J Biol Chem 288 : 29305–29312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.502559 23979136

69. Vajjhala PR, Wong JS, To H-Y, Munn AL (2006) The beta domain is required for Vps4p oligomerization into a functionally active ATPase. FEBS J 273 : 2357–2373. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05238.x 16704411

70. Lupas AN, Martin J (2002) AAA proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 12 : 746–753. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(02)00388-3 12504679

71. Solinger J a, Kiianitsa K, Heyer WD (2002) Rad54, a Swi2/Snf2-like recombinational repair protein, disassembles Rad51:dsDNA filaments. Mol Cell 10 : 1175–1188. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00743-8 12453424

72. Ferdous M, Higgins JD, Osman K, Lambing C, Roitinger E, et al. (2012) Inter-homolog crossing-over and synapsis in Arabidopsis meiosis are dependent on the chromosome axis protein AtASY3. PLoS Genet 8: e1002507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002507 22319460

73. Sanchez-Moran E, Santos JL, Jones GH, Franklin FCH (2007) ASY1 mediates AtDMC1-dependent interhomolog recombination during meiosis in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 21 : 2220–2233. doi: 10.1101/gad.439007 17785529

74. Stacey NJ, Kuromori T, Azumi Y, Roberts G, Breuer C, et al. (2006) Arabidopsis SPO11-2 functions with SPO11-1 in meiotic recombination. Plant J 48 : 206–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02867.x 17018031

75. Pradillo M, Lõpez E, Linacero R, Romero C, Cuñado N, et al. (2012) Together yes, but not coupled: New insights into the roles of RAD51 and DMC1 in plant meiotic recombination. Plant J 69 : 921–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04845.x 22066484

76. Chelysheva L, Gendrot G, Vezon D, Doutriaux M - P, Mercier R, et al. (2007) ZIP4/SPO22 is required for class I CO formation but not for synapsis completion in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet 3: e83. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030083 17530928

77. Macaisne N, Novatchkova M, Peirera L, Vezon D, Jolivet S, et al. (2008) SHOC1, an XPF endonuclease-related protein, is essential for the formation of class I meiotic crossovers. Curr Biol 18 : 1432–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.041 18812090

78. Higgins JD, Vignard J, Mercier R, Pugh AG, Franklin FCH, et al. (2008) AtMSH5 partners AtMSH4 in the class I meiotic crossover pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana, but is not required for synapsis. Plant J 55 : 28–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03470.x 18318687

79. Chelysheva L, Vezon D, Chambon A, Gendrot G, Pereira L, et al. (2012) The Arabidopsis HEI10 is a new ZMM protein related to Zip3. PLoS Genet 8: e1002799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002799 22844245

80. Ross KJ, Fransz P, Jones GH (1996) A light microscopic atlas of meiosis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Chromosom Res 4 : 507–516.

81. Armstrong SJ, Caryl APP, Jones GH, Franklin FCH (2002) Asy1, a protein required for meiotic chromosome synapsis, localizes to axis-associated chromatin in Arabidopsis and Brassica. J Cell Sci 115 : 3645–3655. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00048 12186950

82. Higgins JD, Sanchez-Moran E, Armstrong SJ, Jones GH, Franklin FCH (2005) The Arabidopsis synaptonemal complex protein ZYP1 is required for chromosome synapsis and normal fidelity of crossing over. Genes Dev 19 : 2488–2500. doi: 10.1101/gad.354705 16230536

83. Nakagawa T, Kurose T, Hino T, Tanaka K, Kawamukai M, et al. (2007) Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J Biosci Bioeng 104 : 34–41. doi: 10.1263/jbb.104.34 17697981

84. Azimzadeh J, Nacry P, Christodoulidou A, Drevensek S, Camilleri C, et al. (2008) Arabidopsis TONNEAU1 proteins are essential for preprophase band formation and interact with centrin. Plant Cell 20 : 2146–2159. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056812 18757558

85. Perkins DD (1949) Biochemical mutants in the smut fungus Ustilago Maydis. Genetics 34 : 607–626. 17247336

86. Malkova A, Swanson J, German M, McCusker JH, Housworth E a, et al. (2004) Gene conversion and crossing over along the 405-kb left arm of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome VII. Genetics 168 : 49–63. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027961 15454526

87. Shinohara M, Sakai K, Shinohara A, Bishop DK (2003) Crossover interference in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires a TID1/RDH54 - and DMC1-dependent pathway. Genetics 163 : 1273–1286. 12702674

88. Preuss D, Rhee SY, Davis RW (1994) Tetrad analysis possible in Arabidopsis with mutation of the QUARTET (QRT) genes. Science 264 : 1458–1460. 8197459

89. Lorieux M (2012) MapDisto: fast and efficient computation of genetic linkage maps. Mol Breed 30 : 1231–1235. doi: 10.1007/s11032-012-9706-y

90. Kosambi D (1943) The estimation of map distances from recombination values. Ann Eugen 12 : 172–175.

91. Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I (2001) Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res 125 : 279–284. 11682119

92. Zhang D, Rogers GC, Buster DW, Sharp DJ (2007) Three microtubule severing enzymes contribute to the “Pacman-flux” machinery that moves chromosomes. J Cell Biol 177 : 231–242. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612011 17452528

93. Mukherjee S, Diaz Valencia JD, Stewman S, Metz J, Monnier S, et al. (2012) Human fidgetin is a microtubule severing enzyme and minus-end depolymerase that regulates mitosis. Cell Cycle 11 : 2359–2366. doi: 10.4161/cc.20849 22672901

94. Cox G a, Mahaffey CL, Nystuen A, Letts V a, Frankel WN (2000) The mouse fidgetin gene defines a new role for AAA family proteins in mammalian development. Nat Genet 26 : 198–202. doi: 10.1038/79923 11017077

95. Yang Y, Mahaffey CL, Bérubé N, Nystuen A, Frankel WN (2005) Functional characterization of fidgetin, an AAA-family protein mutated in fidget mice. Exp Cell Res 304 : 50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.11.014 15707573

96. Yakushiji Y, Yamanaka K, Ogura T (2004) Identification of a cysteine residue important for the ATPase activity of C. elegans fidgetin homologue. FEBS Lett 578 : 191–197. 15581640

97. Casanova M, Crobu L, Blaineau C, Bourgeois N, Bastien P, et al. (2009) Microtubule-severing proteins are involved in flagellar length control and mitosis in Trypanosomatids. Mol Microbiol 71 : 1353–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06594.x 19183280

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Discovery and Fine-Mapping of Glycaemic and Obesity-Related Trait Loci Using High-Density ImputationČlánek A Conserved Pattern of Primer-Dependent Transcription Initiation in and Revealed by 5′ RNA-seqČlánek TopBP1 Governs Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells Survival in Zebrafish Definitive HematopoiesisČlánek Redundant Roles of Rpn10 and Rpn13 in Recognition of Ubiquitinated Proteins and Cellular Homeostasis

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2015 Číslo 7- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- LINE-1 Retroelements Get ZAPped!

- /p23: A Small Protein Heating Up Lifespan Regulation

- Hairless Streaks in Cattle Implicate TSR2 in Early Hair Follicle Formation

- Ribosomal Protein Mutations Result in Constitutive p53 Protein Degradation through Impairment of the AKT Pathway

- Molecular Clock of Neutral Mutations in a Fitness-Increasing Evolutionary Process

- Modeling Implicates in Nephropathy: Evidence for Dominant Negative Effects and Epistasis under Anemic Stress

- The Alternative Sigma Factor SigX Controls Bacteriocin Synthesis and Competence, the Two Quorum Sensing Regulated Traits in

- BMP Inhibition in Seminomas Initiates Acquisition of Pluripotency via NODAL Signaling Resulting in Reprogramming to an Embryonal Carcinoma

- Comparative Study of Regulatory Circuits in Two Sea Urchin Species Reveals Tight Control of Timing and High Conservation of Expression Dynamics

- EIN3 and ORE1 Accelerate Degreening during Ethylene-Mediated Leaf Senescence by Directly Activating Chlorophyll Catabolic Genes in

- Genome Wide Binding Site Analysis Reveals Transcriptional Coactivation of Cytokinin-Responsive Genes by DELLA Proteins

- Sensory Neurons Arouse . Locomotion via Both Glutamate and Neuropeptide Release

- A Year of Infection in the Intensive Care Unit: Prospective Whole Genome Sequencing of Bacterial Clinical Isolates Reveals Cryptic Transmissions and Novel Microbiota

- Inference of Low and High-Grade Glioma Gene Regulatory Networks Delineates the Role of Rnd3 in Establishing Multiple Hallmarks of Cancer

- Novel Role for p110β PI 3-Kinase in Male Fertility through Regulation of Androgen Receptor Activity in Sertoli Cells

- A Novel Locus Harbouring a Functional Nonsense Mutation Identified in a Large Danish Family with Nonsyndromic Hearing Impairment

- Checkpoint Activation of an Unconventional DNA Replication Program in

- A Genetic Incompatibility Accelerates Adaptation in Yeast

- The SMC Loader Scc2 Promotes ncRNA Biogenesis and Translational Fidelity

- Blimp1/Prdm1 Functions in Opposition to Irf1 to Maintain Neonatal Tolerance during Postnatal Intestinal Maturation

- Discovery and Fine-Mapping of Glycaemic and Obesity-Related Trait Loci Using High-Density Imputation

- JAK/STAT and Hox Dynamic Interactions in an Organogenetic Gene Cascade

- Emergence, Retention and Selection: A Trilogy of Origination for Functional Proteins from Ancestral LncRNAs in Primates

- MoSET1 (Histone H3K4 Methyltransferase in ) Regulates Global Gene Expression during Infection-Related Morphogenesis

- Arabidopsis PCH2 Mediates Meiotic Chromosome Remodeling and Maturation of Crossovers

- AAA-ATPase FIDGETIN-LIKE 1 and Helicase FANCM Antagonize Meiotic Crossovers by Distinct Mechanisms

- A Conserved Pattern of Primer-Dependent Transcription Initiation in and Revealed by 5′ RNA-seq

- Tempo and Mode of Transposable Element Activity in Drosophila

- The Shelterin TIN2 Subunit Mediates Recruitment of Telomerase to Telomeres

- SAMHD1 Inhibits LINE-1 Retrotransposition by Promoting Stress Granule Formation

- A Genome Scan for Genes Underlying Microgeographic-Scale Local Adaptation in a Wild Species

- TopBP1 Governs Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells Survival in Zebrafish Definitive Hematopoiesis

- Analysis of the Relationships between DNA Double-Strand Breaks, Synaptonemal Complex and Crossovers Using the Mutant

- Assessing Mitochondrial DNA Variation and Copy Number in Lymphocytes of ~2,000 Sardinians Using Tailored Sequencing Analysis Tools

- Allelic Spectra of Risk SNPs Are Different for Environment/Lifestyle Dependent versus Independent Diseases

- CSB-PGBD3 Mutations Cause Premature Ovarian Failure

- Irrepressible: An Interview with Mark Ptashne

- Genetic Evidence for Function of the bHLH-PAS Protein Gce/Met As a Juvenile Hormone Receptor

- Inactivation of Retinoblastoma Protein (Rb1) in the Oocyte: Evidence That Dysregulated Follicle Growth Drives Ovarian Teratoma Formation in Mice

- Redundant Roles of Rpn10 and Rpn13 in Recognition of Ubiquitinated Proteins and Cellular Homeostasis

- Pyrimidine Pool Disequilibrium Induced by a Cytidine Deaminase Deficiency Inhibits PARP-1 Activity, Leading to the Under Replication of DNA

- Molecular Framework of a Regulatory Circuit Initiating Two-Dimensional Spatial Patterning of Stomatal Lineage

- RFX2 Is a Major Transcriptional Regulator of Spermiogenesis

- A Role for Macro-ER-Phagy in ER Quality Control

- Corp Regulates P53 in via a Negative Feedback Loop

- Common Cell Shape Evolution of Two Nasopharyngeal Pathogens

- Contact- and Protein Transfer-Dependent Stimulation of Assembly of the Gliding Motility Machinery in

- Endothelial Snail Regulates Capillary Branching Morphogenesis via Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 3 Expression

- Functional Constraint Profiling of a Viral Protein Reveals Discordance of Evolutionary Conservation and Functionality

- Temporal Coordination of Carbohydrate Metabolism during Mosquito Reproduction

- mTOR Directs Breast Morphogenesis through the PKC-alpha-Rac1 Signaling Axis

- Reversible Oxidation of a Conserved Methionine in the Nuclear Export Sequence Determines Subcellular Distribution and Activity of the Fungal Nitrate Regulator NirA

- Nutritional Control of DNA Replication Initiation through the Proteolysis and Regulated Translation of DnaA

- Cooperation between Paxillin-like Protein Pxl1 and Glucan Synthase Bgs1 Is Essential for Actomyosin Ring Stability and Septum Formation in Fission Yeast

- Encodes a Highly Conserved Protein Important to Neurological Function in Mice and Flies

- Identification of a Novel Regulatory Mechanism of Nutrient Transport Controlled by TORC1-Npr1-Amu1/Par32

- Aurora-A-Dependent Control of TACC3 Influences the Rate of Mitotic Spindle Assembly

- Large-Scale Phenomics Identifies Primary and Fine-Tuning Roles for CRKs in Responses Related to Oxidative Stress

- TFIIS-Dependent Non-coding Transcription Regulates Developmental Genome Rearrangements

- Genome-Wide Reprogramming of Transcript Architecture by Temperature Specifies the Developmental States of the Human Pathogen

- Identification of Chemical Inhibitors of β-Catenin-Driven Liver Tumorigenesis in Zebrafish

- The Catalytic and Non-catalytic Functions of the Chromatin-Remodeling Protein Collaborate to Fine-Tune Circadian Transcription in

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Functional Constraint Profiling of a Viral Protein Reveals Discordance of Evolutionary Conservation and Functionality

- Reversible Oxidation of a Conserved Methionine in the Nuclear Export Sequence Determines Subcellular Distribution and Activity of the Fungal Nitrate Regulator NirA

- Modeling Implicates in Nephropathy: Evidence for Dominant Negative Effects and Epistasis under Anemic Stress

- Nutritional Control of DNA Replication Initiation through the Proteolysis and Regulated Translation of DnaA

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy