-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Fis Is Essential for Capsule Production in and Regulates Expression of Other Important Virulence Factors

P.

multocida is the causative agent of a wide range of diseases of animals, including fowl cholera in poultry and wild birds. Fowl cholera isolates of P. multocida generally express a capsular polysaccharide composed of hyaluronic acid. There have been reports of spontaneous capsule loss in P. multocida, but the mechanism by which this occurs has not been determined. In this study, we identified three independent strains that had spontaneously lost the ability to produce capsular polysaccharide. Quantitative RT-PCR showed that these strains had significantly reduced transcription of the capsule biosynthetic genes, but DNA sequence analysis identified no mutations within the capsule biosynthetic locus. However, whole-genome sequencing of paired capsulated and acapsular strains identified a single point mutation within the fis gene in the acapsular strain. Sequencing of fis from two independently derived spontaneous acapsular strains showed that each contained a mutation within fis. Complementation of these strains with an intact copy of fis, predicted to encode a transcriptional regulator, returned capsule expression to all strains. Therefore, expression of a functional Fis protein is essential for capsule expression in P. multocida. DNA microarray analysis of one of the spontaneous fis mutants identified approximately 30 genes as down-regulated in the mutant, including pfhB_2, which encodes a filamentous hemagglutinin, a known P. multocida virulence factor, and plpE, which encodes the cross protective surface antigen PlpE. Therefore these experiments define for the first time a mechanism for spontaneous capsule loss in P. multocida and identify Fis as a critical regulator of capsule expression. Furthermore, Fis is involved in the regulation of a range of other P. multocida genes including important virulence factors.

Published in the journal: Fis Is Essential for Capsule Production in and Regulates Expression of Other Important Virulence Factors. PLoS Pathog 6(2): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000750

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000750Summary

P.

multocida is the causative agent of a wide range of diseases of animals, including fowl cholera in poultry and wild birds. Fowl cholera isolates of P. multocida generally express a capsular polysaccharide composed of hyaluronic acid. There have been reports of spontaneous capsule loss in P. multocida, but the mechanism by which this occurs has not been determined. In this study, we identified three independent strains that had spontaneously lost the ability to produce capsular polysaccharide. Quantitative RT-PCR showed that these strains had significantly reduced transcription of the capsule biosynthetic genes, but DNA sequence analysis identified no mutations within the capsule biosynthetic locus. However, whole-genome sequencing of paired capsulated and acapsular strains identified a single point mutation within the fis gene in the acapsular strain. Sequencing of fis from two independently derived spontaneous acapsular strains showed that each contained a mutation within fis. Complementation of these strains with an intact copy of fis, predicted to encode a transcriptional regulator, returned capsule expression to all strains. Therefore, expression of a functional Fis protein is essential for capsule expression in P. multocida. DNA microarray analysis of one of the spontaneous fis mutants identified approximately 30 genes as down-regulated in the mutant, including pfhB_2, which encodes a filamentous hemagglutinin, a known P. multocida virulence factor, and plpE, which encodes the cross protective surface antigen PlpE. Therefore these experiments define for the first time a mechanism for spontaneous capsule loss in P. multocida and identify Fis as a critical regulator of capsule expression. Furthermore, Fis is involved in the regulation of a range of other P. multocida genes including important virulence factors.Introduction

Pasteurella multocida is an important veterinary pathogen of worldwide economic significance; it is the causative agent of a range of diseases, including fowl cholera in poultry, hemorrhagic septicemia in ungulates and atrophic rhinitis in swine. P. multocida is a heterogeneous species, and is generally classified into five capsular serogroups (A, B, D, E and F) and 16 somatic LPS serotypes (1–16) [1]. Each serogroup produces a distinct capsular polysaccharide, with serogroups A, D and F producing capsules composed of hyaluronic acid (HA) [2], heparin and chondroitin [3], respectively. The structures of the serogroup B and E capsules are not known, although preliminary compositional analysis suggests that these capsules have a more complex structure than those produced by serogroups A, D and F [4]. The genes involved in biosynthesis, export and surface attachment of the capsular polysaccharide have been identified for all capsule types [5]–[7]. For strains which express HA, the capsule biosynthetic locus (cap) consists of 10 genes; phyA and phyB are predicted to encode proteins responsible for lipidation of the polysaccharide, hyaE, hyaD, hyaC and hyaB encode proteins required for polysaccharide biosynthesis and hexD, hexC, hexB and hexA encode proteins responsible for transport of the polysaccharide to the bacterial surface [6].

The P. multocida capsule is a major virulence determinant in both serogroup A and B strains. In the serogroup A strain X-73 (A:1), inactivation of the capsule transport gene hexA resulted in a mutant strain that was highly attenuated in both mice and chickens, and was more sensitive to the bactericidal activity of chicken serum [8]. Similarly, mutation of the hexA orthologue, cexA, in the serogroup B strain M1404 also resulted in significant attenuation; the M1404 cexA mutant was 4–6 times more sensitive than the parent to phagocytosis by murine macrophages [9].

Spontaneous capsule loss during in vitro sub-culture has been described in P. multocida [10],[11]. In one study, acapsular variants were derived from capsulated parent strains by repeated laboratory passage (>30 sub-cultures) [12]. Sequence analysis of the cap locus in one of these acapsular variants identified two nucleotide changes near the putative promoter region, but the authors did not determine whether these changes were responsible for the observed acapsular phenotype. No further work has been published on the genetic mechanisms of regulation of P. multocida capsule production.

Fis is a growth phase-dependent, nucleoid-associated protein which plays a role in the transcriptional regulation of a number of genes in diverse bacterial species (reviewed in [13]). In Escherischia coli, Fis is expressed at high levels in actively growing cells (>50 000 molecules per cell in early exponential growth phase), and expression drops to very low levels during stationary phase [14],[15]. In addition to growth phase regulation, levels of Fis are negatively regulated by the stringent response during nutrient starvation [16]. Fis can act as both a positive or negative regulator of transcription and it has both direct and indirect effects on gene transcription. In E. coli and Salmonella, Fis binds to a degenerate 15-bp consensus sequence GNtYAaWWWtTRaNC, inducing DNA bending, but only a few of the sequences fitting this consensus are high affinity binding sites [17],[18]. Fis is involved in the regulation of genes encoding a wide range of functions, including quorum sensing in Vibrio cholerae [19], and certain virulence factors in Erwinia chrysanthemi [20], pathogenic E. coli [21],[22] and Salmonella [23].

In this study, we have characterized three independently isolated spontaneous acapsular derivatives of the P. multocida A:1 strain VP161. Whole genome sequencing and DNA microarrays were used to show that the global regulator Fis not only controls the expression of capsule biosynthesis genes in P. multocida, but also regulates a number of other genes, including known and putative virulence factors.

Results

Identification of spontaneous acapsular P. multocida strains

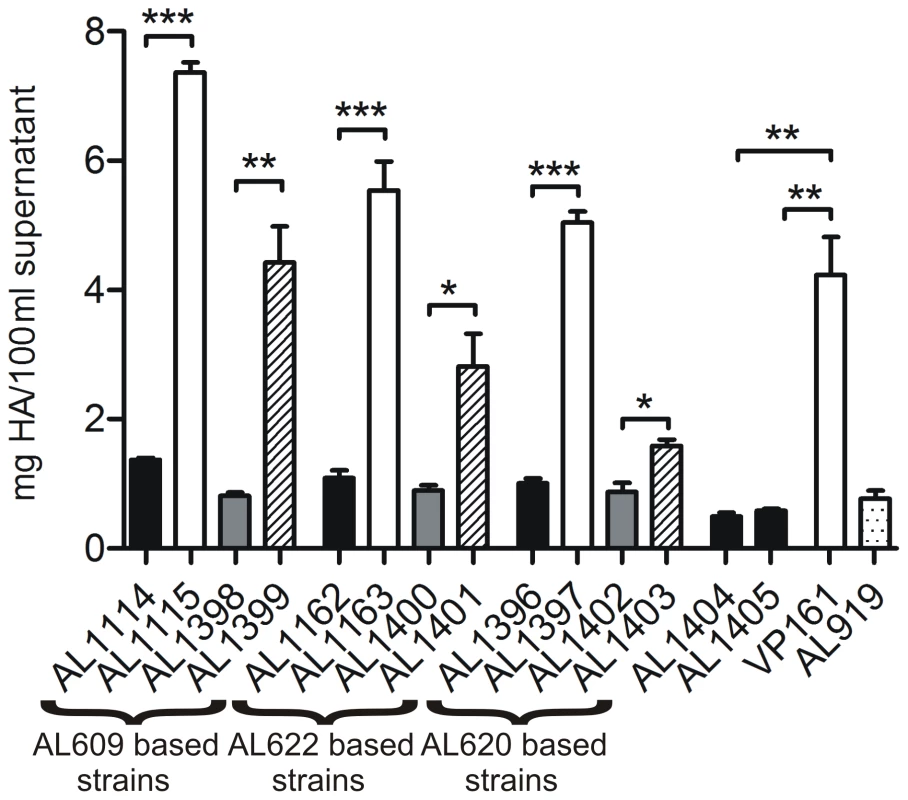

Spontaneous capsule loss has been reported previously in P. multocida, and is generally associated with long term in vitro passage on laboratory media [10]–[12]. During routine strain maintenance of a signature-tagged mutagenesis library, we identified three independent P. multocida strains that presented with both large mucoid and small non-mucoid colonies after recovery from short term (<1 year) −80°C glycerol storage. Re-isolation of either colony type resulted in stable populations with colony morphologies identical to those of their parents, such that AL609, AL622 and AL620 gave rise to the small non-mucoid variants AL1114, AL1162 and AL1396 and to the large mucoid variants AL1115, AL1163 and AL1397, respectively (Table 1). Quantitative HA assays confirmed that all three small, non-mucoid colony variants (AL1114, AL1162 and AL1396) expressed significantly less capsular material than their paired large, mucoid colony variants (AL1115, AL1163 and AL1397) and the parental VP161 strain (Fig. 1). Indeed, the small colony variants expressed similar levels of HA to that expressed by a defined (hyaB) acapsular polysaccharide biosynthesis mutant generated by single crossover allelic exchange (AL919; Table 1) (Fig. 1). As each of the paired strains was derived from transposon mutants with different transposon insertion sites (AL609, AL622 and AL620; Table 1), and the transposon was still present at identical positions in both the paired mucoid and non-mucoid derivatives of each type, we concluded that the acapsular phenotype was independent of the initial transposition event.

Fig. 1. Hyaluronic acid (HA) capsular polysaccharide produced by P. multocida strains.

The amount of capsular material is shown for paired acapsular (AL1114, AL1162 and AL1396) and capsulated (AL1115, AL1163 and AL1397) variants and the same strains complemented with either empty vector (AL1398, AL1400 and AL1402) or an intact copy of fis (AL1399, AL1401 and AL1403). Brackets below the figure indicate strains derived from the same parent strain. Also shown is the amount of HA produced by the TargeTron fis mutants AL1404 and AL1405, the wild-type encapsulated parent strain VP161 and the hyaB capsule mutant AL919. Results for experimentally related strains are shaded similarly with black bars representing fis mutants, white bars representing parent and wild-type strains, hatched bars representing the fis complemented strains, gray bars representing strains transformed with vector only and the dotted bar representing the directed hyaB mutant. Each bar represents triplicate values ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM) *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. Tab. 1. Strains and plasmids used in this study.

Decreased capsule production in the acapsular strains results from decreased transcription of the cap biosynthetic locus

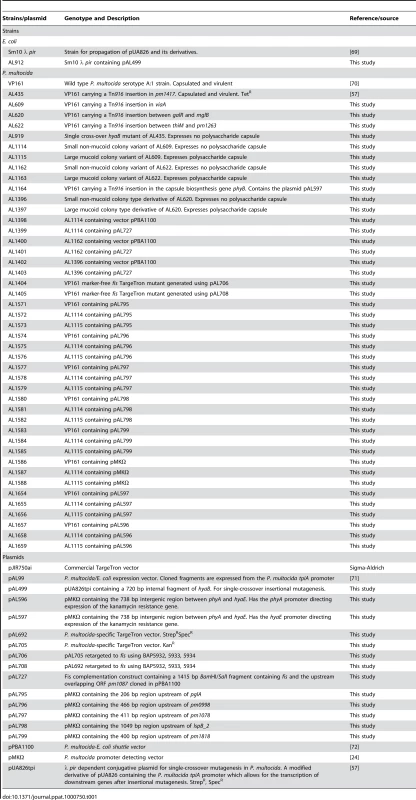

The genes responsible for HA capsule polysaccharide biosynthesis and transport have been identified previously and are located in a single region of the P. multocida chromosome [6] (Fig. 2). In order to investigate whether the loss of capsule production in these spontaneously arising acapsular variants was due to a mutation in the cap biosynthetic locus, the nucleotide sequence of the entire 14,935 bp locus of AL1114 and the wild-type parent VP161 was determined. Comparison of the sequences revealed that they were identical; indicating that the acapsular phenotype observed in AL1114 was not due to mutation within the cap locus.

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of the P. multocida serogroup A capsule biosynthetic locus and identification of the hyaE transcriptional start site.

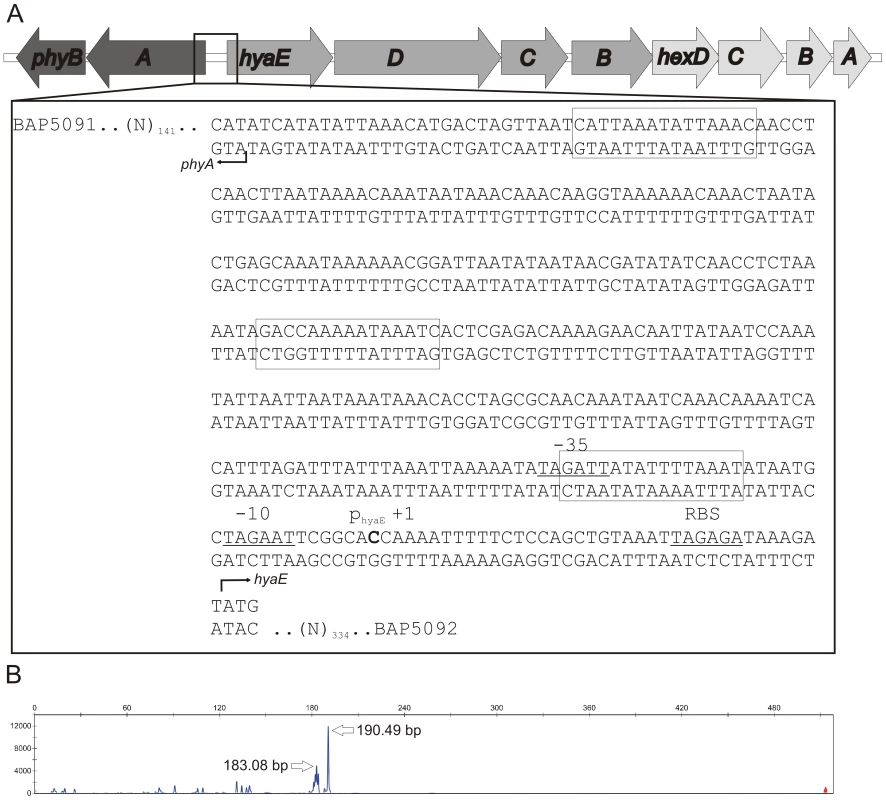

The organization of the genes in the capsule biosynthetic locus is shown in panel A and the nucleotide sequence of the intergenic region between phyA and hyaE is shown in the flyout box. The positions of the HyaE and PhyA translational initiation codons (ATG) are designated by right-angled arrowheads and the identified transcriptional start site for hyaE is shown in bold text and labeled +1. Predicted RBS, −10 and −35 sites are underlined, and labeled above the sequence. Predicted Fis binding sites based on the E. coli position specific weight matrix are boxed [15]. The length (x-axis) and quantity (y-axis) of hyaE-specific primer extension products generated using VP161 total RNA and the primer BAP5476 are shown in panel B. The exact size (in bp) of the major primer extension products are shown beside the peaks. As there were no sequence changes observed between these two strains, we investigated transcription across the cap locus by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). Transcription of the P. multocida capsule biosynthetic genes is predicted to initiate from divergent promoters located in the intergenic region between the divergent phyA and hyaE genes (Fig. 2, [6]). Transcription of phyA and hyaE was significantly reduced in the acapsular variant AL1114 as compared to both the paired capsulated strain AL1115 and the parent strain VP161 (Fig. 3). Furthermore, a directed P. multocida hyaB mutant (AL919, Table 1), showed high levels of transcription across both genes showing that transcription across the locus is not affected by the level of capsular polysaccharide on the cell surface. These data show that the reduced capsule production in the acapsular variant AL1114 was likely a result of reduced transcription across the biosynthetic locus.

Fig. 3. Relative expression of phyA and hyaE in four P. multocida strains.

The expression levels of phyA (panel A) and hyaE (panel B) were determined for the strains VP161 (wild-type), AL1114 (spontaneous acapsular strain), AL1115 (paired capsulated strain) and AL919 (a VP161 hyaB insertional mutant) by qRT-PCR and normalized to the level of gyrB expression. The average relative expression was determined from three biological replicates and the values shown are the mean ±1 SEM. ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. To characterize further the transcriptional regulation of the cap locus, we identified the position of the hyaE transcriptional start site by fluorescent primer extension (Fig. 2). A primer extension product was generated from P. multocida VP161 RNA using the primer BAP5476 (Table 2). A 190 bp extension fragment was detected, (Fig. 2B), which identified the transcript start site for hyaE as 37 bp upstream of the hyaE start codon (Fig. 2). The −10 and −35 regions of the hyaE promoter were predicted based on the identified transcript start site (Fig. 2). Repeated attempts failed to detect a primer extension product corresponding to phyA.

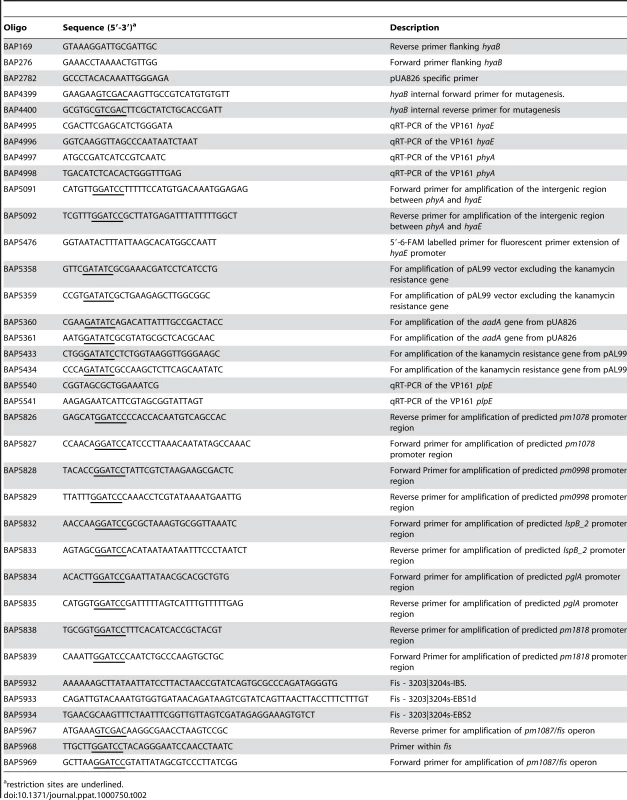

Tab. 2. Oligonucleotides used in this study.

restriction sites are underlined. To determine the activity of the phyA and hyaE promoters in both encapsulated and non-encapsulated strains, the intergenic region between phyA and hyaE (Fig. 2) was cloned in both orientations into the P. multocida promoter-detecting vector pMKΩ (Table 1; [24]) to generate pAL596 and pAL597. In pAL597 the pMKΩ kanamycin resistance gene is under the control of the hyaE promoter while in pAL596 it is under the control of the putative phyA promoter. These plasmids were then tested for their ability to confer kanamycin resistance on the wild-type P. multocida strain VP161, the encapsulated strain AL1115 and the acapsular variant AL1114 (Table 1). Both plasmids conferred higher levels of kanamycin resistance to the wild-type strain VP161 and the encapsulated strain AL1115 than when present in the acapsular strain AL1114 (Fig. 4). In contrast, the acapsular strain AL1114, harboring either pAL596 or pAL597 remained kanamycin sensitive, indicating that the phyA and hyaE promoters are inactive in this strain. These data show that both the phyA and hyaE promoters are active only when present in the encapsulated strains VP161 and AL1115, indicating that the activity of these promoters is regulated by a trans-acting transcriptional regulator which is inactive in the acapsular strain AL1114.

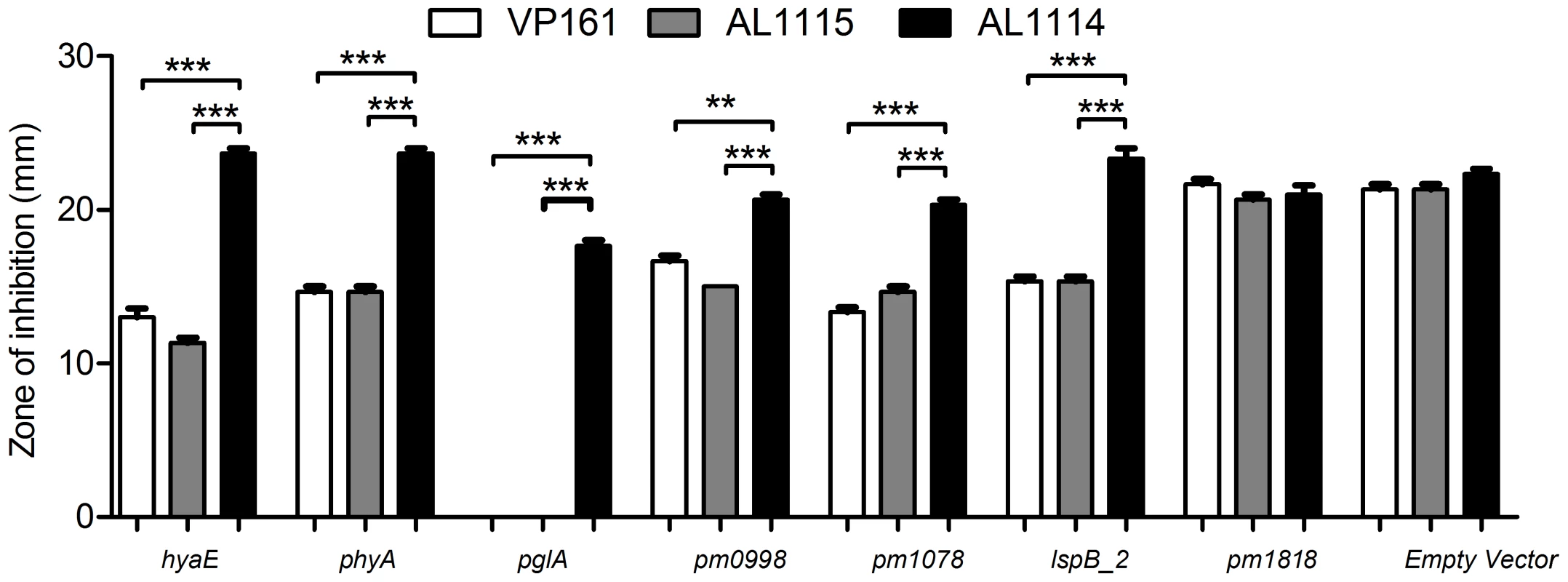

Fig. 4. Sensitivity of P. multocida strains to kanamycin as determined by disc diffusion assays.

The putative promoter-containing regions upstream of hyaE, phyA, pglA, pm0998, pm1078, lspB_2, and pm1818 were cloned into the P. multocida promoter detecting vector pMKΩ, and the ability of the recombinant constructs (pAL597, pAL596, pAL795, pAL796, pAL797, pAL798 and pAL799 respectively) to confer kanamycin resistance to strains AL1114 (spontaneous acapsular strain), AL1115 (paired capsulated strain) and VP161 (capsulated wild-type parent) assessed. Empty pMKΩ vector was used as a negative control. The average relative expression was determined from three biological replicates and the values shown are the mean ±1 SEM. *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01. Identification of the transcriptional regulator of P. multocida capsule expression

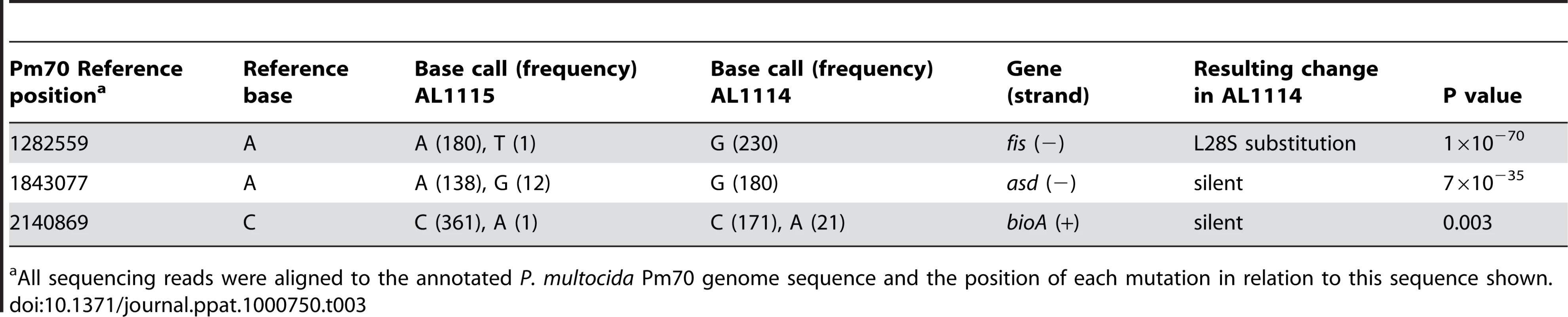

In order to identify the trans-acting transcriptional regulator responsible for the regulation of capsule expression, we sequenced the entire genomes of the acapsular variant AL1114 and its paired capsular strain AL1115, using high-throughput short read sequencing. Reference assemblies were generated for both strains using the fully annotated P. multocida PM70 genome [25] as a scaffold. These assemblies were then used to determine nucleotide differences between AL1114 and AL1115, and thus identify changes unique to AL1114. Three nucleotide changes were identified as unique to AL1114 when compared to AL1115 (Table 3); of these, the mutations within asd and bioA were silent and did not result in amino acid substitutions. However, the observed nucleotide T to C transition within an ORF annotated as encoding Fis, would result in a non-conservative L28S amino acid substitution within the Fis protein. The deduced P. multocida Fis protein is 99 amino acids in length and shares 80% identity with the 98 amino acid E. coli Fis (NCBI GeneID 947697; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=gene&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=Graphics&list_uids=947697) which has been shown to be a nucleoid-associated transcriptional regulator.

Tab. 3. Sequence differences identified by whole-genome Illumina short read sequencing between the acapsular strain AL1114 and the paired capsulated strain AL1115.

All sequencing reads were aligned to the annotated P. multocida Pm70 genome sequence and the position of each mutation in relation to this sequence shown. To confirm that the mutation observed in fis was associated with loss of capsule expression, the nucleotide sequence of fis was determined by Sanger dideoxy sequencing in all three acapsular variants (AL1114, AL1162 and AL1396) and their paired capsulated strains (AL1115, AL1163 and AL1397). Analysis of these sequence data confirmed the L28S mutation in Fis in AL1114 compared to AL1115. In AL1162, a G to T transversion at nucleotide 3 resulted in a change from the methionine start codon to the non-start codon isoleucine (ATT), stopping translation of Fis. In AL1396, a C to T substitution at nucleotide 222 resulted in a nonsense mutation (Q75*) and termination of the Fis protein at amino acid 74. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that mutation of fis was correlated with loss of capsule expression in all three spontaneous acapsular P. multocida strains.

Functional Fis is required for capsule expression

In order to confirm Fis as the transcriptional regulator of capsule expression, we complemented each of the spontaneous acapsular variants with an intact copy of Fis in trans. In E. coli, fis is auto-regulated, and is expressed as part of a two gene operon together with the upstream gene yhdG, predicted to encode a tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase [14],[16],[26]; the same organization is observed in P. multocida. We initially attempted to clone fis by itself but were unable to successfully make this construct. Therefore, we cloned fis, the overlapping upstream gene pm1087 and the predicted native promoter, into the P. multocida shuttle vector pPBA1100, generating the plasmid pAL727 (Table 1). The plasmid pAL727 and the vector only (pPBA1100) were separately introduced into each of the acapsular variants AL1114, AL1162 and AL1396 and quantitative HA assays performed to determine levels of capsule expression. In all cases, HA production was significantly higher in strains harboring pAL727 (AL1399, AL1401 and AL1403) than in control strains harboring empty vector (AL1398, AL1400 and AL1402) (p<0.05), although full complementation to wild type levels was not observed (Fig. 1).

Inactivation of fis results in decreased capsule production

To confirm that Fis is essential for capsule production in P. multocida we constructed two independent, marker free fis mutations in the wild-type P. multocida VP161 strain using the intron-mediated TargeTron system (Sigma). We constructed two P. multocida-specific TargeTron vectors that were retargeted for the insertional inactivation of fis at nucleotide 48 (pAL706 and pAL708; Table 1). P. multocida transformants with intron insertions in fis were identified by PCR and, following curing of the mutagenesis plasmid, correct insertion of the intron in fis was confirmed by direct genomic sequencing (data not shown). A single insertion mutant generated from transformation with either pAL706 or pAL708 was selected for further study, and designated AL1404 and AL1405 respectively. Quantitative HA assays confirmed that insertional inactivation of fis resulted in the loss of capsular polysaccharide production in both AL1404 and AL1405 (Fig. 1; Table 1), showing unequivocally that Fis is essential for the production of capsular polysaccharide in P. multocida strain VP161.

Identification of P. multocida genes regulated by Fis

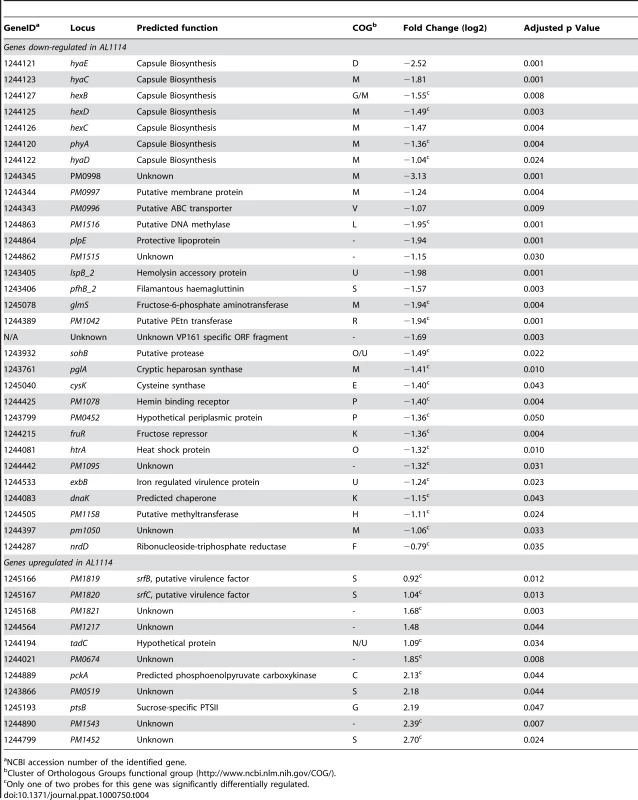

Fis is known to be a global regulator in a number of bacterial species [15],[20],[27]. We therefore used whole genome DNA microarrays to compare the transcriptome of the acapsular variant AL1114 (expressing Fis L28S) with the encapsulated paired strain AL1115 (expressing wild-type Fis). Custom Combimatrix 12k microarrays were designed and used as described in Materials and Methods. Thirty one genes were identified as significantly down-regulated and eleven genes as significantly up-regulated in the acapsular variant AL1114 (Table 4). Seven of the ten capsule biosynthesis genes were identified as down-regulated in AL1114 compared to AL1115, supporting the qRT-PCR data showing reduced transcription of phyA and hyaE. Expression of the known P. multocida virulence gene pfhB_2 and its predicted secretion partner lspB_2 was reduced 3 - to 4-fold in AL1114. In addition, the gene encoding the outer membrane lipoprotein PlpE, which is a surface exposed lipoprotein that can stimulate cross-serotype protective immunity against P. multocida infection [28], was also down-regulated in the acapsular strain AL1114. Other down-regulated genes included pglA, encoding a cryptic heparosan synthase; exbB, an iron-regulated virulence factor; pm1042, encoding a predicted LPS-specific phosphoethanolamine transferase; htrA, encoding a heat shock protein; fruR, encoding the fructose operon repressor; glmS encoding a fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase, and a range of genes encoding proteins of unknown function. Eleven genes were identified as up-regulated in the acapsular strain. These included pm1819 and pm1820, which encode proteins with similarity to the Salmonella SrfB and SrfC proteins, both putative virulence factors also controlled by Fis [23], tadC, a gene predicted to be involved in an outer membrane secretion system, and seven genes encoding proteins of unknown function. Several of the genes identified as differentially expressed were physically linked on the chromosome and given their similar expression patterns we predict that these are expressed as operons (e.g., plpE, pm1516 and pm1515; pm0996, pm0997 and pm0998; pm1819, pm1820 and pm1821; Table 4).

Tab. 4. Genes identified as differentially regulated between the P. multocida wild-type strain and a fis mutant strain as determined by DNA microarray analysis.

NCBI accession number of the identified gene. Confirmation of the microarray data

In order to confirm the differential expression of some of the genes identified by the microarray analyses, two different methods were used. Firstly, the putative promoter regions of each of the down-regulated genes pglA, pm0998, pm1078, lspB_2 and the region upstream of pm1818 containing the putative promoter for the operon containing the up-regulated genes pm1819, pm1820 and pm1821, were cloned into the P. multocida promoter probe vector pMKΩ (Table 1), generating the recombinant plasmids pAL795, pAL796, pAL797, pAL798 and pAL799, respectively (Table 1). The recombinant plasmids were transformed into the acapsular strain AL1114 (expressing Fis L28S), the capsulated paired strain AL1115 (expressing wild-type Fis) and the wild-type parent strain VP161 (Table 1). With the exception of pAL799, each of the recombinant pMKΩ derivatives conferred higher levels of kanamycin resistance to AL1115 and the wild-type VP161 than to the acapsular variant AL1114 (Fig. 4). These data support the microarray results and show that the activity of the promoters for pglA, pm0998, pm1078 and lspB_2 are significantly reduced in the absence of wild-type Fis. Each of the strains harboring pAL799 showed similar levels of kanamycin resistance regardless of the capsule phenotype, suggesting that the cloned fragment in this construct does not contain a Fis regulated promoter, or that the fragment does not contain all the necessary Fis binding sites required for repression of this promoter.

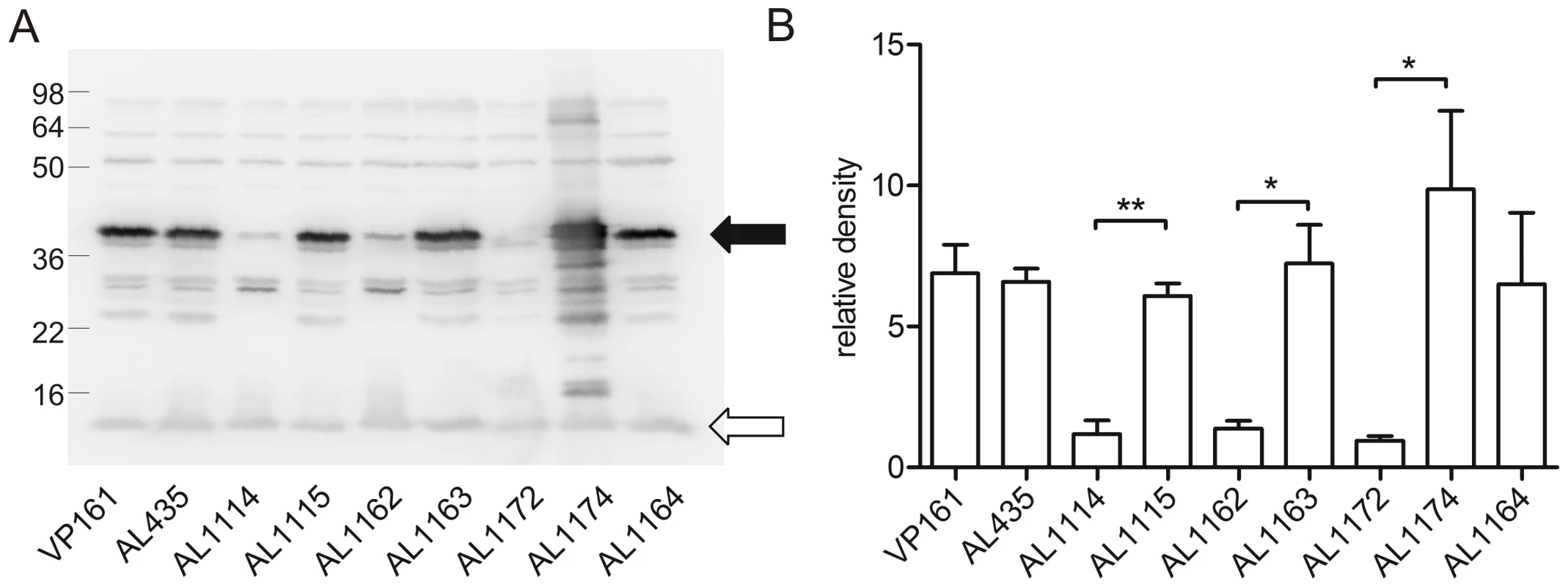

As a second method of confirmation, qRT-PCR and western immunoblot analyses were undertaken to confirm the reduced expression of plpE in AL1114. PlpE is a predicted outer membrane lipoprotein which can stimulate cross-serotype protective immunity against P. multocida [28]. Microarray analysis indicated that the plpE transcription was reduced by approximately 3.8-fold in the spontaneously arising acapsular strain (Table 4). Transcriptional analysis of plpE by qRT-PCR confirmed that the transcription of this gene was significantly reduced (data not shown). Western immunoblots using antiserum generated against recombinant PlpE (Fig. 5) confirmed that PlpE expression was significantly reduced in the spontaneously arising acapsular variants AL1114 and AL1162, as well as a directed plpE mutant AL1172 (Table 1), but not in the directed phyB acapsular strain AL1164. Therefore, PlpE mRNA levels are positively regulated by Fis.

Fig. 5. Western immunoblot and densitometry analysis of P. multocida PlpE expression in acapsular, capsulated and control strains.

Western immunoblot using chicken antiserum against recombinant PlpE (A) and the corresponding quantitive densitometry analysis (B). The levels of PlpE expression were measured in the capsulated parent strains (VP161, AL435), the acapsular fis mutants (AL1114, AL1162) and paired capsulated strains (AL1115, AL1163), a single-crossover plpE mutant (AL1172; Hatfaludi, Al-Hasani and Adler, unpublished data), complemented plpE mutant (AL1174) and the acapsular phyB mutant strain that produces no HA (AL1164). The filled arrow head represents the position of PlpE, whilst the unfilled arrowhead represents the background band used as a loading control for densitometry normalization. Each bar represents the average normalized densitometry readings from triplicate biological replicates ±1 SEM. ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. Discussion

The expression of a polysaccharide capsule is critical for the virulence of P. multocida [8],[9]. While there is evidence that the level of capsule expression in P. multocida responds to certain environmental conditions (such as growth in the presence of antibiotics, low iron or specific iron sources such as hemoglobin [29]–[32], there is no information on the mechanism of capsule regulation. There have been numerous reports of spontaneous loss of capsule expression in P. multocida strains following in vitro passage [10],[11], but the mechanism by which this occurs has not been determined. Previous work with laboratory-derived, spontaneous acapsular strains has indicated that loss of capsule expression was associated with reduced transcription of genes within the capsule biosynthesis locus [12]. In this study, we identified three independent spontaneous acapsular strains and showed that loss of capsule expression in these strains was also due to reduced transcription of the cap locus. Furthermore, we showed that this reduced transcription was due to point mutations within the gene encoding the global transcriptional regulator Fis. Thus, Fis is essential for capsule expression and these experiments define a mechanism by which spontaneous capsule loss can occur and identify for the first time a transcriptional regulator required for capsule expression in P. multocida. Importantly, while Fis has been shown to be involved in the regulation of a large number of genes in a range of bacterial species, to our knowledge this is the first report showing a role for Fis in the regulation of capsule biosynthesis. Furthermore, this is the first report that a functional Fis protein is expressed in P. multocida and that it acts as a regulator of gene expression.

Fis was initially identified as the factor for DNA inversion in the Hin and Gin family of DNA recombinases [33],[34]. Subsequently, diverse roles for Fis have been described, including both positive and negative regulation of gene expression. Fis has also been identified in other members of the Pasteurellaceae, including Haemophilus influenzae Rd. While the H. influenzae Fis shared 81% identity with the E. coli Fis, it did not display identical activity [35]. Interestingly, P. multocida Fis shares 92% identity with the H. influenzae Fis but only 80% identity with E. coli Fis.

Structurally, Fis folds into four α-helices (A–D) and a β-hairpin [36]. Helices A and B provide the contacts between Fis monomers, facilitating dimer formation, whereas the C and D helices form a helix-turn-helix motif that is essential for DNA binding [37]–[39]. We identified three spontaneous acapsular strains with point mutations within fis. The Fis mutation L28S is predicted to result in a highly unstable protein, as a mutation in the equivalent position in the E. coli Fis (L27R) resulted in an unstable protein with no discernible activity [36]. However, as the P. multocida Fis shares only 80% amino acid identity with the E. coli Fis, we can not rule out the possibility that the P. multocida L28S Fis is a partially functional protein that is impaired in only some specific functions of WT Fis. Computational models also suggest a requirement for hydrophobic residues at this position [40] and the substitution of leucine by the hydrophilic residue serine would significantly reduce the hydrophobicity at this position. The second spontaneous acapsular variant, AL1162, contained a mutation within the fis start codon, which would result in complete abrogation of Fis expression. Finally, the fis gene in AL1396 contained a nonsense mutation at nucleotide 222, terminating protein translation at amino acid 74. This mutant Fis protein would lack the last 16 amino acids, including the helix-turn-helix motif that is essential for DNA binding [39].

As Fis is known to regulate a number of genes in other species, we used DNA microarrays to compare the transcriptome of wild-type P. multocida and the Fis L28S mutant (AL1114) during exponential growth. Comparison of the fis mutant strain with wild-type P. multocida identified 31 genes (representing at least 20 predicted operons) as positively regulated by Fis, and 11 genes (representing at least nine operons) as negatively regulated by Fis. In E. coli, two transcriptional studies have been conducted comparing gene expression in wild-type and Fis mutant strains. The first study identified more than 200 genes that were regulated by Fis at various growth phases (>2 fold change, p<0.05) [15]. The second study identified >900 genes (21% of the E. coli genome) that were significantly differentially regulated in the fis mutant (false discovery rate <1%), although only 17 of these were >2 fold differentially regulated [27]. Interestingly, approximately 70% of the 900 genes shown to be differentially regulated in the second study showed no Fis binding as determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with high resolution whole genome-tiling arrays [27]. In P. multocida we identified 42 genes as differentially regulated by Fis during the exponential growth phase. During this growth phase the regulation of P. multocida genes by Fis was skewed towards the up-regulation of genes by Fis (70% of operons), indicating that Fis generally acts as a transcriptional activator, a finding consistent with previous studies [15],[27].

Both P. multocida and E. coli Fis share significant similarity across the C-terminal DNA binding region, suggesting that they may recognise similar sequences. However, using the available E. coli position specific weight matrix [15], we were unable to identify conserved sites upstream of all of the Fis regulated genes identified in the DNA microarray experiments. This is not entirely unexpected, as Fis has been shown to bind a variety of AT-rich sequences more or less non-specifically [13]. Indeed, the ability of Fis to induce DNA bending is probably the most important factor in its ability to control transcription [41]. The relatively low number of P. multocida genes regulated by Fis in the exponential growth phase is somewhat surprising. However, as Fis expression in other bacteria has been shown to be growth phase dependant [15],[42],[43], it is likely that other P. multocida genes will be differentially regulated by Fis during different growth phases. While an equivalent L27R mutation in E. coli Fis results in an unstable protein, we can not rule out the possibility that the L28S mutation in P. multocida Fis results in a protein that retains some, but not all, Fis regulatory functions. Thus, it is possible that more genes might be observed as differentially regulated in a Fis null mutant strain and we are currently investigating this possibility.

Of the 42 differentially expressed genes identified in the P. multocida Fis mutant, a large number (16/42; 38%) encode proteins that are surface expressed or involved in the synthesis of surface exposed structures. Clearly Fis regulates the genes involved in the biosynthesis of, and surface presentation of, capsular polysaccharide, and expression of these genes is critical for virulence. Fis is also involved in the regulation of the surface exposed virulence factor PfhB_2 and its outer membrane secretion partner LspB_2 and the surface expressed lipoprotein PlpE. Both PlpE and PfhB2 can provide protection against P. multocida infection when used as vaccine antigens [28],[44]. Other surface-associated Fis-regulated genes identified by the DNA microarray analyses included: pm1042, encoding a transferase predicted to attach phosphoethanolamine to lipid A of LPS; tadC, a gene located within the tight adherence locus that has been shown in Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans to be responsible for non-specific attachment to surfaces and is required for full expression of the RcpABC outer membrane proteins [45]; pm1078, encoding a putative iron-specific ABC transporter component; and the genes encoding PM0998 [46], PM1050 and PM1819 [47] which have all been experimentally shown to be present in outer membrane sub-fractions of the P. multocida proteome. Fis also regulates the expression of ExbB, an inner membrane protein that interacts with TonB and is critical for iron uptake and virulence in P. multocida [48].

The P. multocida filamentous hemagglutinin PfhB_2 has been previously identified as a virulence factor [49],[50] and recent work has shown that vaccination with recombinant PfhB_2 can induce protective immunity in turkeys [44]. In other species such as Bordetella pertussis the secretion of the filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA) into the extracellular medium is reliant on the outer membrane protein FhaC [51]. In both Haemophilus and Bordetella, expression of the outer membrane secretion component is controlled by the two-component signal transduction systems cpxRA [52] and bvgAS [53] respectively. It is clear from our work that in P. multocida Fis co-ordinately activates the expression of PfhB_2 and its upstream predicted secretion partner LspB_2. However, we can not exclude the possibility that expression of these genes is also dependent on other regulatory mechanisms such as a two component signal transduction system.

Of particular significance is the finding that Fis regulates plpE, which encodes the cross protective antigen PlpE [28]. Interestingly, previous studies on spontaneous acapsular strains have indicated that loss of a 39–40 kDa lipoprotein was correlated with the loss of capsular polysaccharide and it was hypothesized that the lack of expression of this protein on the surface was due to the physical loss of capsule [11], [54]–[56]. We propose that the lipoprotein identified in the above studies is in fact PlpE and its expression is reduced in spontaneous acapsular strains because of the transcriptional down-regulation of the gene due to the absence of Fis.

In summary, we have characterized three independently derived, spontaneous, acapsular variants of P. multocida. In all three strains, loss of capsule production was due to a single nucleotide change in the gene encoding the nucleoid-associated protein Fis, identifying for the first time a mechanism for spontaneous capsule loss and a regulator critical for P. multocida capsule expression. Furthermore, analysis of gene expression in the fis mutant provides convincing evidence for the role of Fis in the regulation of critical P. multocida virulence factors and surface exposed components.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli was grown in 2YT broth and P. multocida in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth or nutrient broth (NB). Solid media were obtained by the addition of 1.5% agar. When required, the media were supplemented with streptomycin (50 µg/ml), spectinomycin (50 µg/ml), kanamycin (50 µg/ml) or tetracycline (2.5 µg/ml).

Molecular techniques

Restriction digests and ligations were performed according to the manufacturers' instructions using enzymes obtained from NEB (Beverly, MA) or Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Mannheim, Germany). Plasmid DNA was prepared using Qiagen DNA miniprep spin columns (Qiagen, GmbH, Germany). P. multocida genomic DNA was isolated using the RBC genomic DNA purification kit (RBC, Taiwan). Amplification of DNA by PCR was performed using Taq DNA polymerase (Roche) and, when required, PCR amplified products were purified using the Qiagen PCR purification Kit (Qiagen, GmbH, Germany). Oligonucleotides used in this study (Table 2) were synthesized by Sigma, Australia. For transformation of plasmid DNA into P. multocida, electro-competent cells were prepared as described previously [8] and electroporated at 1800V, 600Ω, 25µF. DNA sequences obtained by Sanger sequencing were determined on an Applied Biosystems 3730S Genetic Analyser and sequence analysis was performed with Vector NTI Advance version 10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Generation of a single cross-over mutant in hyaB

For inactivation of hyaB in P. multocida strain VP161 we used the previously described single-crossover insertional mutagenesis method which utilizes the λ pir-dependent plasmid pUA826 [57]. A 720 bp internal fragment of hyaB was amplified by PCR using oligonucleotides BAP4399 and BAP4400 (Table 2), and cloned into the SalI site of pUA826tpi, generating pAL499 (Table 1). This plasmid was then mobilized from E. coli SM10 λ pir into P. multocida strain AL435 by conjugation, and insertional mutants selected on BHI agar containing tetracycline, spectinomycin and streptomycin. Single cross-over insertion of the recombinant plasmid into hyaB was confirmed by PCR using either of the genomic flanking primers BAP276 or BAP169 (Table 1) together with BAP2782 located within the plasmid pUA826tpi. One transconjugant with the correct insertion in hyaB was selected for further study, and designated AL919 (Table 1).

Disc diffusion assays

Disc diffusion assays were performed on soft agar overlays. Briefly, 100 µl of each P. multocida overnight culture was mixed with 3 ml of BHI containing 0.8% agar and immediately poured onto a BHI agar (1.5%) base. Kanamycin at a range of concentrations, was absorbed onto sterile Whatman paper discs, placed on the agar overlay containing P. multocida, and incubated for 18 h at 37°C. Inhibition of growth was determined as the diameter of the zone of clearing around the discs.

Quantitative HA assays

Crude capsular material was extracted as described previously [58] with the following modifications. One ml of a P. multocida overnight culture was pelleted by centrifugation at 13 000 g, and washed once with 1 ml of PBS. Washed cells were resuspended in 1 ml of fresh PBS, incubated at 42°C for 1 h, then pelleted, and the supernatant, containing crude capsular polysaccharide, collected. HA content was determined as described previously [8].

Fluorescent primer extension

Fluorescent primer extension was performed as described previously [59], with the following modifications. First strand cDNA synthesis was performed with SuperScript III RT (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A typical reaction contained 10 µg of total RNA, 1mM dNTPs and 6-FAM labeled primer at a final concentration of 100 nM. Fragment length analysis of FAM-labeled cDNAs was performed by the Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF, Melbourne). cDNA fragments were separated on an AB3730 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems), and sizes determined using Genemapper V3.7 software (Applied Biosystems).

High-throughput genome sequencing and analysis

High-throughput sequencing was performed on an Illumina GA2 (Illumina, USA) by the Micromon Sequencing Facility (Monash University, Australia). Two lanes of 36-bp single end data were generated for both AL1114 and AL1115. Raw sequence data from both strains was aligned independently to the P. multocida PM70 genome sequence using SHRiMP [60] (average read depth ∼200), which is able to produce alignments in the presence of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions and deletions (indels). These alignments were then used to compile, for each position in the reference, a contingency table of counts of observed bases in each of the two samples, and the significance of each different base call was determined using Fisher's exact test. The determined significance values were corrected for multiple testing using the Bonferonni adjustment. Raw read data were also assembled de novo using VELVET [61] or CLC genomics workbench (CLC).

Complementation of spontaneous mutants and construction of plasmids for promoter analysis

For complementation of spontaneous acapsular strains, wild-type Fis and the overlapping upstream ORF pm1087, were amplified from P. multocida VP161 genomic DNA using oligonucleotides BAP5967 and BAP5969 (Table 2) containing SalI and BamHI sites respectively. The amplified fragment was digested and cloned into SalI - and BamHI-digested pPBA1100, generating pAL727 (Table 1). This plasmid was then used to transform the acapsular strains AL1114, AL1162 and AL1396, generating AL1399, AL1401 and AL1403. As a control, empty pPBA1100 was also used to transform each of these strains, generating AL1398, AL1400 and AL1402 (Table 1).

For analysis of promoter activity in P. multocida, predicted promoter containing fragments were amplified by PCR and cloned into the P. multocida promoter detecting vector pMKΩ, which contains a promoterless kanamycin resistance gene (Table 1, [24]). The genomic region containing the hyaE promoter and the predicted phyA promoter was amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotides BAP5091 and BAP5092 (Table 2) and cloned in both orientations into pMKΩ to generate pAL596 and pAL597. The predicted promoter containing fragments upstream of the genes pglA, pm0998, pm1078, lspB_2 and pm1818 (the first gene in a putative operon containing pm1819, pm1820 and pm1821) were amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotide pairs BAP5834 and BAP5835 (pglA), BAP5828 and BAP5829 (pm0998), BAP5826 and BAP5827 (pm1078), BAP5832 and BAP5833 (lspB_2) and BAP5838 and BAP5839 (pm1818) (Table 2) and each fragment cloned into pMKΩ to generate pAL795, pAL796, pAL797, pAL798 and pAL799, respectively (Table 1). Each of the recombinant plasmids was then transformed into the wild-type parent strain VP161, the acapsular fis mutant strain AL1114 and its paired capsulated derivative AL1115. Promoter activity from the cloned fragment in pMKΩ was assessed semi-quantitatively by disc diffusion assays where a reduced zone of growth inhibition around kanamycin impregnated discs indicated a higher level of kanamycin resistance and therefore promoter activity from the cloned fragment.

Construction of P. multocida directed fis mutants

The E. coli/P. multocida shuttle vector pAL99 (Table 1) was used to generate two TargeTron vectors, pAL692 and pAL705, for the generation of marker-free fis mutants in P. multocida. The spectinomycin/streptomycin resistant TargeTron vector pAL692 (Table 1) was constructed as follows: pAL99 was amplified by PCR using outward facing primers that flank the aph3 gene (BAP5358 and BAP5359) and digested with EcoRV. This fragment was ligated to an EcoRV-digested PCR fragment containing the aadA gene amplified from pUA826 using the primers BAP5360 and BAP5361. Following ligation the plasmid was digested with HindIII and FspI and ligated to a 4 kb HindIII/FspI-digested fragment of pJIR750ai encoding the TargeTron intron and ltrA gene (Table 1) such that transcription would be driven by the constitutive P. multocida tpiA promoter. For construction of the kanamycin resistant TargeTron vector pAL705 (Table 1), the aph3 gene was amplified from pAL99 using the primers BAP5433 and BAP5434 then cloned into EcoRV-digested pAL692, thereby replacing the aadA gene.

Retargeting of the intron within each vector to nucleotide 48 of fis was performed as per the TargeTron user manual (Sigma) using the oligonucleotides BAP5932-BAP5934 (Table 1). The retargeted mutagenesis plasmids, pAL706 (KanR) and pAL708 (StrepR/SpecR) (Table 1) were used to transform P. multocida VP161 and antibiotic resistant transformants selected on either spectinomycin or kanamycin. Insertion of the intron into the P. multocida genome was detected using the fis-specific oligonucleotides BAP5967 and BAP5968 (Table 1); the presence of the intron resulted in a 0.9 kb increase in the size of the PCR product compared to the PCR product generated from the wild-type fis (data not shown). Mutants confirmed by PCR to have insertions in fis were cured of the replicating TargeTron plasmid by a single overnight growth in NB broth without antibiotic selection, followed by patching of single colonies for either StrepSSpecS or KanS. Strains cured of replicating plasmid were confirmed as fis mutants by additional PCR amplifications to show the presence of the intron and the absence of a copy of wild-type fis (data not shown). Finally, fis mutations were confirmed by direct genomic sequencing using intron-specific primers.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Bacteria were harvested from triplicate BHI cultures at late log phase (∼5×109 CFU/ml) by centrifugation at 13 000 g, and RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Gibco/BRL) as described by the manufacturer. The purified total RNA was treated with DNase (15 U for 10 min at 37°C), and then further purified on RNeasy mini columns (Qiagen). Primers for qRT-PCR were designed using the Primer Express software (ABI) (BAP4995-BAP4998; Table 2). RT reactions were routinely performed in 20 µl volumes, containing 5 µg total RNA, 15 ng random hexamers, 0.5mM dNTPs and 300 U SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) at 42°C for 2.5 h. The synthesized cDNA samples were diluted 50-fold prior to qRT-PCR, which was performed using an Eppendorf realplex4 mastercycler with product accumulation quantified by incorporation of the fluorescent dye SYBR Green. Samples were assayed in triplicate using 2 µl of diluted cDNA with SYBR Green PCR master mix (ABI) and 50 nM concentrations of each gene-specific primer. The concentration of template in each reaction was determined by comparison with a gene-specific standard curve constructed from known concentrations of P. multocida strain VP161 genomic DNA. gyrB was used as the normalizer for all reactions. All RT-PCRs amplified a single product as determined by melting curve analysis.

Microarray analysis

Custom Combimatrix 12k microarrays (Combimatrix, USA) were designed based on the published sequence of P. multocida PM70 [25], with the addition of probes specific for ORFs previously identified as unique to P. multocida strain VP161 [62]. cDNA for microarray hybridizations was prepared as for qRT-PCR, except that RNA contamination was removed from the cDNA by the addition of NaOH followed by column purification (Qiagen minElute, Qiagen). A total of 2 µg of purified cDNA was labeled using KREAtech Cy3-ULS (KREAtech, The Netherlands), and used in hybridizations with the Combimatrix 12k microarrays as per the manufacturer's instructions. Triplicate hybridized arrays were scanned on a Genepix 4000b scanner, and spot intensities determined using Microarray Imager v5.9.3 (Combimatrix, USA). After scanning, each array was immediately stripped and re-scanned as per manufacturers' instructions. Spot intensities of stripped arrays were used as background correction for the quantification of subsequent hybridizations. Spots from duplicate probes were averaged, and the averaged probe intensities analyzed using the LIMMA software package [63] as follows. Background correction was performed using the LIMMA “normexp” method [64], and the Log2 values calculated. Between-array quantile normalization [65] was then applied to the log transformed spot intensities. A moderated t-test on the normalized log intensities was performed to identify differentially expressed genes. Probes were sorted by significance, and the False Discovery Rate (FDR) [66] used to control for multiple testing. Probes showing ≥2-fold intensity change between AL1114 and AL1115, with a FDR of <0.05 were considered differentially expressed (Table 2). Two probes were designed for all genes over 500 bp in length; genes were classed as differentially expressed if one or both probes showed a differential expression of ≥2 - fold. DNA microarray experiments were carried out according to MIAME guidelines and the complete experimental data can be obtained online from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) submission number GSE17686.

SDS-PAGE, western immunoblot and densitometry

SDS-PAGE was performed as described previously [67]. Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore). Western immunoblot analysis was performed using standard techniques [68], with chicken anti-recombinant PlpE as the primary antibody and peroxidase-conjugated anti-chicken immunoglobulin (raised in donkeys) as the secondary antibody. Blots were visualized using CDP-Star (Roche), and imaged on a Fujifilm LAS-3000 chemiluminescent imager (Fujifilm). Densitometry was performed using Multi-gauge software v2.3 (Fujifilm)

Zdroje

1. CarterGR

ChengappaMM

Recommendations for a standard system of designating serotypes of Pasteurella multocida; 1981. 37 42 American Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians

2. CifonelliJA

RebersPA

HeddlestonKL

1970 The isolation and characterisation of hyaluronic acid from Pasteurella multocida. Carbohydr Res 14 272 276

3. DeAngelisPL

GunayNS

ToidaT

MaoWJ

LinhardtRJ

2002 Identification of the capsular polysaccharides of Type D and F Pasteurella multocida as unmodified heparin and chondroitin, respectively. Carbohydr Res 337 1547 1552

4. MuniandyN

EdgarJ

WoolcockJB

MukkurTKS

Virulence, purification, structure, and protective potential of the putative capsular polysaccharide of Pasteurella multocida type 6:B.

PattenBE

SpencerTL

JohnsonRB, DH

LehaneL

Pasteurellosis in production animals; 1992 Bali, Indonesia 47 53

5. BoyceJD

ChungJY

AdlerB

2000 Genetic organisation of the capsule biosynthetic locus of Pasteurella multocida M1404 (B:2). Vet Microbiol 72 121 134

6. ChungJY

ZhangYM

AdlerB

1998 The capsule biosynthetic locus of Pasteurella multocida A-1. FEMS Microbiol Lett 166 289 296

7. TownsendKM

BoyceJD

ChungJY

FrostAJ

AdlerB

2001 Genetic organization of Pasteurella multocida cap loci and development of a multiplex capsular PCR typing system. J Clin Microbiol 39 924 929

8. ChungJY

WilkieI

BoyceJD

TownsendKM

FrostAJ

2001 Role of capsule in the pathogenesis of fowl cholera caused by Pasteurella multocida serogroup A. Infect Immun 69 2487 2492

9. BoyceJD

AdlerB

2000 The capsule is a virulence determinant in the pathogenesis of Pasteurella multocida M1404 (B:2). Infect Immun 68 3463 3468

10. HeddlestonKL

WatkoLP

RebersPA

1964 Dissociation of a fowl cholera strain of Pasteurella multocida. Avian Dis 8 649 657

11. ChamplinFR

PattersonCE

AustinFW

RyalsPE

1999 Derivation of extracellular polysaccharide-deficient variants from a serotype A strain of Pasteurella multocida. Curr Microbiol 38 268 272

12. WattJM

SwiatloE

WadeMM

ChamplinFR

2003 Regulation of capsule biosynthesis in serotype A strains of Pasteurella multocida. FEMS Microbiol Lett 225 9 14

13. GraingerDC

BusbySJ

2008 Global regulators of transcription in Escherichia coli: mechanisms of action and methods for study. Adv Appl Microbiol 65 93 113

14. BallCA

OsunaR

FergusonKC

JohnsonRC

1992 Dramatic changes in Fis levels upon nutrient upshift in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 174 8043 8056

15. BradleyMD

BeachMB

de KoningAP

PrattTS

OsunaR

2007 Effects of Fis on Escherichia coli gene expression during different growth stages. Microbiol 153 2922 2940

16. NinnemannO

KochC

KahmannR

1992 The E. coli fis promoter is subject to stringent control and autoregulation. EMBO J 11 1075 1083

17. PanCQ

FinkelSE

CramtonSE

FengJA

SigmanDS

1996 Variable structures of Fis-DNA complexes determined by flanking DNA-protein contacts. J Mol Biol 264 675 695

18. ShaoY

Feldman-CohenLS

OsunaR

2008 Biochemical identification of base and phosphate contacts between Fis and a high-affinity DNA binding site. J Mol Biol 380 327 339

19. LenzDH

BasslerBL

2007 The small nucleoid protein Fis is involved in Vibrio cholerae quorum sensing. Mol Microbiol 63 859 871

20. LautierT

NasserW

2007 The DNA nucleoid-associated protein Fis co-ordinates the expression of the main virulence genes in the phytopathogenic bacterium Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol Microbiol 66 1474 1490

21. SaldanaZ

Xicohtencati-CortesJ

AvelinoF

PhillipsAD

KaperJB

2009 Synergistic role of curli and cellullose in cell adherance and biofilm formation and attaching and effacing Escherichia coli and identification of Fis as a negative regulator of curli. Environ Micro 11 992 1006

22. GoldbergMD

JohnsonM

HintonJC

WilliamsPH

2001 Role of the nucleoid-associated protein Fis in the regulation of virulence properties of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 41 549 559

23. KellyA

GoldbergMD

CarrollRK

DaninoV

HintonJCD

2004 A global role for Fis in the transcriptional control of metabolism in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microbiol 150 2037 2053

24. HuntML

BoucherDJ

BoyceJD

AdlerB

2001 In vivo-expressed genes of Pasteurella multocida. Infect Immun 69 3004 3012

25. MayBJ

ZhangQ

LiLL

PaustianML

WhittamTS

2001 Complete genomic sequence of Pasteurella multocida, Pm70. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98 3460 3465

26. BishopAC

XuJ

JohnsonRC

SchimmelP

de Crecy-LagardV

2002 Identification of the tRNA-dihydrouridine synthase family. J Biol Chem 277 25090 25095

27. ChoBK

KnightEM

BarrettCL

PalssonBO

2008 Genome-wide analysis of Fis binding in Escherichia coli indicates a causative role for A-/AT-tracts. Genome Res 18 900 910

28. WuJR

ShienJH

ShiehHK

ChenCF

ChangPC

2007 Protective immunity conferred by recombinant Pasteurella multocida lipoprotein E (PlpE). Vaccine 25 4140 4148

29. JacquesM

BelangerM

DiarraMS

DargisM

MalouinF

1994 Modulation of Pasteurella multocida capsular polysaccharide during growth under iron-restricted conditions and in vivo. Microbiol 140 263 270

30. MelnikowE

SchoenfeldC

SpehrV

WarrassR

GunkelN

2007 A compendium of antibiotic-induced transcription profiles reveals broad regulation of Pasteurella multocida virulence genes. Vet Microbiol 131 277 292

31. PaustianML

MayBJ

CaoD

BoleyD

KapurV

2002 Transcriptional response of Pasteurella multocida to defined iron sources. J Bacteriol 184 6714 6720

32. PaustianML

MayBJ

KapurV

2001 Pasteurella multocida gene expression in response to iron limitation. Infect Immun 69 4109 4115

33. JohnsonRC

BruistMF

SimonMI

1986 Host protein requirements for in vitro site-specific DNA inversion. Cell 46 531 539

34. KahmannR

RudtF

KochC

MertensG

1985 G inversion in bacteriophage Mu DNA is stimulated by a site within the invertase gene and a host factor. Cell 41 771 780

35. BeachMB

OsunaR

1998 Identification and characterization of the fis operon in enteric bacteria. J Bacteriol 180 5932 5946

36. SafoMK

YangW-Z

CorselliL

CramptonSE

YuanHS

1997 The transactivation region of the Fis protein that controls site-specific DNA inversion contrains extended mobile β-hairpin arms. EMBO J 16 6860 6873

37. KochC

NinnemannO

FussH

KahmannR

1991 The N-terminal part of the E.coli DNA binding protein FIS is essential for stimulating site-specific DNA inversion but is not required for specific DNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res 19 5915 5922

38. OsunaR

FinkelSE

JohnsonRC

1991 Identification of two functional regions in Fis: the N-terminus is required to promote Hin-mediated DNA inversion but not lambda excision. EMBO J 10 1593 1603

39. YuanHS

FinkelSE

FengJA

Kaczor-GrzeskowiakM

JohnsonRC

1991 The molecular structure of wild-type and mutant Fis protein: Relationship between mutational changes and recombinational enhancer function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88 9558 9562

40. TzouW-S

HwangM-J

1997 A model for Fis N-Terminus and Fis invertase recognition. FEBS Lett 401 1 5

41. TraversA

SchneiderR

MuskhelishviliG

2001 DNA supercoiling and transcription in Escherichia coli: The FIS connection. Biochimie 83 213 217

42. MallikP

PrattTS

BeachMB

BradleyMD

UndamatlaJ

2004 Growth phase-dependent regulation and stringent control of fis are conserved processes in enteric bacteria and involve a single promoter (fis P) in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 186 122 135

43. KraissA

SchlorS

ReidlJ

1998 In vivo transposon mutagenesis in Haemophilus influenzae. Appl Environ Microbiol 64 4697 4702

44. TatumFM

TabatabaiLB

BriggsRE

2009 Protection against fowl cholera conferred by vaccination with recombinant Pasteurella multocida filamentous hemagglutinin peptides. Avian Dis 53 169 174

45. ClockSA

PlanetPJ

PerezBA

FigurskiDH

2008 Outer membrane components of the Tad (Tight Adherence) secretion of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. J Bacteriol 190 980 990

46. BoyceJD

CullenPA

NguyenV

WilkieI

AdlerB

2006 Analysis of the Pasteurella multocida outer membrane sub-proteome and its response to the in vivo environment of the natural host. Proteomics 6 870 880

47. TabatabaiLB

ZehrES

2004 Identification of five outer membrane-associated proteins among cross-protective factor proteins of Pasteurella multocida. Infect Immun 72 1195 1198

48. BoschM

GarridoE

LlagosteraM

de RozasAMP

BadiolaI

2002 Pasteurella multocida exbB, exbD and tonB genes are physically linked but independently transcribed. FEMS Microbiol Lett 210 201 208

49. TatumFM

YersinAG

BriggsRE

2005 Construction and virulence of a Pasteurella multocida fhaB2 mutant in turkeys. Microb Pathog 39 9 17

50. FullerTE

KennedyMJ

LoweryDE

2000 Identification of Pasteurella multocida virulence genes in a septicemic mouse model using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Microb Pathog 29 25 38

51. Jacob-DubuissonF

El-HamelC

SaintN

GuedinS

WilleryE

1999 Channel formation by FhaC, the outer membrane protein involved in the secretion of the Bordetella pertussis filamentous hemagglutinin. J Biol Chem 274 37731 37735

52. Labandeira-ReyM

MockJR

HansenEJ

2009 Regulation of expression of the Haemophilus ducreyi LspB and LspA2 proteins by CpxR. Infect Immun 77 3402 3411

53. ScarlatoV

AricoB

PrugnolaA

RappuoliR

1991 Sequential activation and environmental regulation of virulence genes in Bordetella pertussis. EMBO J 10 3971 3975

54. RyalsPE

NsoforMN

WattJM

ChamplinFR

1998 Relationship between serotype A encapsulation and a 40-kDa lipoprotein in Pasteurella multocida. Curr Microbiol 36 274 277

55. ChamplinFR

ShryockTR

PattersonCE

AustinFW

RyalsPE

2002 Prevalence of a novel capsule-associated lipoprotein among Pasteurellaceae pathogenic in animals. Curr Microbiol 44 297 301

56. BorrathybayE

SawadaT

KataokaY

OkiyamaE

KawamotoE

2003 Capsule thickness and amounts of a 39 kDa capsular protein of avian Pasteurella multocida type A strains correlate with their pathogenicity for chickens. Vet Microbiol 97 215 227

57. HarperM

BoyceJD

CoxAD

St MichaelF

WilkieIW

2007 Pasteurella multocida expresses two lipopolysaccharide glycoforms simultaneously, but only a single form is required for virulence: identification of two acceptor-specific heptosyl I transferases. Infect Immun 75 3885 3893

58. GentryJM

CorstvetRE

PancieraRJ

1982 Extraction of capsular material from Pasteurella haemolytica. Am J Vet Res 43 2070 2073

59. LloydAL

MarshallBJ

MeeBJ

2004 Identifying cloned Helicobacter pylori promoters by primer extension using a FAM-labelled primer and GeneScan® analysis. J Microb Methods 60 291 298

60. RumbleSM

LacrouteP

DalcaAV

FiumeM

SidowA

2009 SHRiMP: accurate mapping of short colour-space reads. PLoS Comput Biol 5 e1000386 doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000386

61. ZerbinoDR

BirneyE

2008 Velvet: Algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 18 821 829

62. HarperM

CoxA

St MichaelF

ParnasH

WilkieI

2007 Decoration of Pasteurella multocida lipopolysaccharide with phosphocholine is important for virulence. J Bacteriol 189 7384 7391

63. SmythGK

2004 Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 3 Article 3

64. RitchieME

SilverJ

OshlackA

HolmesM

DiyagamaD

2007 A comparison of background correction methods for two-colour microarrays. Bioinformatics 23 2700 2707

65. BolstadBM

IrizarryRA

AstrandM

SpeedTP

2003 A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on bias and variance. Bioinformatics 19 185 193

66. BenjaminiY

HochbergY

1995 Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B 57 289 300

67. LaemmliUK

1970 Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227 680 685

68. AusubelFM

BrentR

KingstonRE

MooreDD

SeidmanJG

SmithJA

StruhlK

1995 Current protocols in molecular biology New York John Wiley & Sons, Inc

69. MillerVL

MekalanosJJ

1988 A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J Bacteriol 170 2575 2583

70. WilkieIW

GrimesSE

O'BoyleD

FrostAJ

2000 The virulence and protective efficacy for chickens of Pasteurella multocida administered by different routes. Vet Microbiol 72 57 68

71. HarperM

CoxAD

St MichaelF

WilkieIW

BoyceJD

2004 A heptosyltransferase mutant of Pasteurella multocida produces a truncated lipopolysaccharide structure and is attenuated in virulence. Infect Immun 72 3436 3443

72. HomchampaP

StrugnellRA

AdlerB

1997 Cross protective immunity conferred by a marker-free aroA mutant of Pasteurella multocida. Vaccine 15 203 208

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiológia Infekčné lekárstvo Laboratórium

Článek HIV Controller CD4+ T Cells Respond to Minimal Amounts of Gag Antigen Due to High TCR AvidityČlánek Transit through the Flea Vector Induces a Pretransmission Innate Immunity Resistance Phenotype in

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2010 Číslo 2- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Očkování proti virové hemoragické horečce Ebola experimentální vakcínou rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP

- Koronavirus hýbe světem: Víte jak se chránit a jak postupovat v případě podezření?

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Pathogen Entrapment by Transglutaminase—A Conserved Early Innate Immune Mechanism

- Broadly Protective Monoclonal Antibodies against H3 Influenza Viruses following Sequential Immunization with Different Hemagglutinins

- Neutrophil-Derived CCL3 Is Essential for the Rapid Recruitment of Dendritic Cells to the Site of Inoculation in Resistant Mice

- Differentiation, Distribution and γδ T Cell-Driven Regulation of IL-22-Producing T Cells in Tuberculosis

- IFN-α-Induced Upregulation of CCR5 Leads to Expanded HIV Tropism In Vivo

- An Extensive Circuitry for Cell Wall Regulation in

- TgMORN1 Is a Key Organizer for the Basal Complex of

- Direct Presentation Is Sufficient for an Efficient Anti-Viral CD8 T Cell Response

- Immunoelectron Microscopic Evidence for Tetherin/BST2 as the Physical Bridge between HIV-1 Virions and the Plasma Membrane

- A New Nuclear Function of the Glycolytic Enzyme Enolase: The Metabolic Regulation of Cytosine-5 Methyltransferase 2 (Dnmt2) Activity

- Genome-Wide mRNA Expression Correlates of Viral Control in CD4+ T-Cells from HIV-1-Infected Individuals

- Structural and Biochemical Characterization of SrcA, a Multi-Cargo Type III Secretion Chaperone in Required for Pathogenic Association with a Host

- A Major Role for the ApiAP2 Protein PfSIP2 in Chromosome End Biology

- HIV Controller CD4+ T Cells Respond to Minimal Amounts of Gag Antigen Due to High TCR Avidity

- Fis Is Essential for Capsule Production in and Regulates Expression of Other Important Virulence Factors

- Vaccinia Protein F12 Has Structural Similarity to Kinesin Light Chain and Contains a Motor Binding Motif Required for Virion Export

- A Novel Pseudopodial Component of the Dendritic Cell Anti-Fungal Response: The Fungipod

- Efficacy of the New Neuraminidase Inhibitor CS-8958 against H5N1 Influenza Viruses

- Long-Lived Antibody and B Cell Memory Responses to the Human Malaria Parasites, and

- IPS-1 Is Essential for the Control of West Nile Virus Infection and Immunity

- Transit through the Flea Vector Induces a Pretransmission Innate Immunity Resistance Phenotype in

- Ats-1 Is Imported into Host Cell Mitochondria and Interferes with Apoptosis Induction

- Six RNA Viruses and Forty-One Hosts: Viral Small RNAs and Modulation of Small RNA Repertoires in Vertebrate and Invertebrate Systems

- The Syk Kinase SmTK4 of Is Involved in the Regulation of Spermatogenesis and Oogenesis

- Optineurin Negatively Regulates the Induction of IFNβ in Response to RNA Virus Infection

- On the Diversity of Malaria Parasites in African Apes and the Origin of from Bonobos

- Five Questions about Viruses and MicroRNAs

- A Broad Distribution of the Alternative Oxidase in Microsporidian Parasites

- Caspase-1 Activation via Rho GTPases: A Common Theme in Mucosal Infections?

- Peptides Presented by HLA-E Molecules Are Targets for Human CD8 T-Cells with Cytotoxic as well as Regulatory Activity

- Interaction of Rim101 and Protein Kinase A Regulates Capsule

- Distinct External Signals Trigger Sequential Release of Apical Organelles during Erythrocyte Invasion by Malaria Parasites

- Exacerbated Innate Host Response to SARS-CoV in Aged Non-Human Primates

- Reverse Genetics in Predicts ARF Cycling Is Essential for Drug Resistance and Virulence

- Universal Features of Post-Transcriptional Gene Regulation Are Critical for Zygote Development

- Highly Differentiated, Resting Gn-Specific Memory CD8 T Cells Persist Years after Infection by Andes Hantavirus

- Arterivirus Nsp1 Modulates the Accumulation of Minus-Strand Templates to Control the Relative Abundance of Viral mRNAs

- Lethal Antibody Enhancement of Dengue Disease in Mice Is Prevented by Fc Modification

- Quantitative Comparison of HTLV-1 and HIV-1 Cell-to-Cell Infection with New Replication Dependent Vectors

- The Disulfide Bonds in Glycoprotein E2 of Hepatitis C Virus Reveal the Tertiary Organization of the Molecule

- IL-1β Processing in Host Defense: Beyond the Inflammasomes

- Kaposi's Sarcoma Associated Herpes Virus (KSHV) Induced COX-2: A Key Factor in Latency, Inflammation, Angiogenesis, Cell Survival and Invasion

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Caspase-1 Activation via Rho GTPases: A Common Theme in Mucosal Infections?

- Kaposi's Sarcoma Associated Herpes Virus (KSHV) Induced COX-2: A Key Factor in Latency, Inflammation, Angiogenesis, Cell Survival and Invasion

- IL-1β Processing in Host Defense: Beyond the Inflammasomes

- Reverse Genetics in Predicts ARF Cycling Is Essential for Drug Resistance and Virulence

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy