-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Lipopolysaccharide Is Synthesized via a Novel Pathway with an Evolutionary Connection to Protein -Glycosylation

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a major component on the surface of Gram negative bacteria and is composed of lipid A-core and the O antigen polysaccharide. O polysaccharides of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori contain Lewis antigens, mimicking glycan structures produced by human cells. The interaction of Lewis antigens with human dendritic cells induces a modulation of the immune response, contributing to the H. pylori virulence. The amount and position of Lewis antigens in the LPS varies among H. pylori isolates, indicating an adaptation to the host. In contrast to most bacteria, the genes for H. pylori O antigen biosynthesis are spread throughout the chromosome, which likely contributed to the fact that the LPS assembly pathway remained uncharacterized. In this study, two enzymes typically involved in LPS biosynthesis were found encoded in the H. pylori genome; the initiating glycosyltransferase WecA, and the O antigen ligase WaaL. Fluorescence microscopy and analysis of LPS from H. pylori mutants revealed that WecA and WaaL are involved in LPS production. Activity of WecA was additionally demonstrated with complementation experiments in Escherichia coli. WaaL ligase activity was shown in vitro. Analysis of the H. pylori genome failed to detect a flippase typically involved in O antigen synthesis. Instead, we identified a homolog of a flippase involved in protein N-glycosylation in other bacteria, although this pathway is not present in H. pylori. This flippase named Wzk was essential for O antigen display in H. pylori and was able to transport various glycans in E. coli. Whereas the O antigen mutants showed normal swimming motility and injection of the toxin CagA into host cells, the uptake of DNA seemed to be affected. We conclude that H. pylori uses a novel LPS biosynthetic pathway, evolutionarily connected to bacterial protein N-glycosylation.

Published in the journal: Lipopolysaccharide Is Synthesized via a Novel Pathway with an Evolutionary Connection to Protein -Glycosylation. PLoS Pathog 6(3): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000819

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000819Summary

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a major component on the surface of Gram negative bacteria and is composed of lipid A-core and the O antigen polysaccharide. O polysaccharides of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori contain Lewis antigens, mimicking glycan structures produced by human cells. The interaction of Lewis antigens with human dendritic cells induces a modulation of the immune response, contributing to the H. pylori virulence. The amount and position of Lewis antigens in the LPS varies among H. pylori isolates, indicating an adaptation to the host. In contrast to most bacteria, the genes for H. pylori O antigen biosynthesis are spread throughout the chromosome, which likely contributed to the fact that the LPS assembly pathway remained uncharacterized. In this study, two enzymes typically involved in LPS biosynthesis were found encoded in the H. pylori genome; the initiating glycosyltransferase WecA, and the O antigen ligase WaaL. Fluorescence microscopy and analysis of LPS from H. pylori mutants revealed that WecA and WaaL are involved in LPS production. Activity of WecA was additionally demonstrated with complementation experiments in Escherichia coli. WaaL ligase activity was shown in vitro. Analysis of the H. pylori genome failed to detect a flippase typically involved in O antigen synthesis. Instead, we identified a homolog of a flippase involved in protein N-glycosylation in other bacteria, although this pathway is not present in H. pylori. This flippase named Wzk was essential for O antigen display in H. pylori and was able to transport various glycans in E. coli. Whereas the O antigen mutants showed normal swimming motility and injection of the toxin CagA into host cells, the uptake of DNA seemed to be affected. We conclude that H. pylori uses a novel LPS biosynthetic pathway, evolutionarily connected to bacterial protein N-glycosylation.

Introduction

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a prevalent macromolecule in the outer membrane of Gram negative bacteria and represents an important virulence factor. LPS is composed of three parts: lipid A which is embedded in the outer membrane, the core oligosaccharide, and the O antigen [1]. Lipid A is also known as endotoxin, which refers to the induction of fatal reactions of the human immune system at very low LPS concentrations. Bound to lipid A is the core oligosaccharide, which is relatively well conserved among closely related bacteria. The O antigen represents the outermost region of the LPS.

The O antigen of Helicobacter pylori contributes in several respects to the virulence of this human gastric pathogen, which is recognized by the World Health Organization as a Type 1 carcinogen [2]. H. pylori mimics carbohydrate structures present on human epithelial cells, blood cells, and in secretions, by incorporating Lewis antigens on its O chains [3]. In most strains, both, Lewis x (Lex) and Lewis y (Ley), can be found in certain regions of the O antigen. Some strains also display Lewis a (Lea) and b (Leb) antigens or can have alternative O antigen structures [4]. H. pylori profits from this molecular mimicry, as Lex and Ley interact with the C-type lectin DC-SIGN on dendritic cells, which signals the immune system to down-regulate an inflammatory response [5]. The amounts of Lewis antigens and their location on the H. pylori O polysaccharide are variable, differing between strains and also between cells from the same isolate [3],[6]. This is due to the phase variable expression of the H. pylori fucosyltransferases, enzymes required for the synthesis of Lewis antigens [7]. Evidence suggests that the O antigen structures of H. pylori strains are adapted to the individual human host, enabling the establishment of a chronic infection [8],[9].

Unlike most bacteria, the genes involved in LPS biosynthesis in H. pylori are not arranged in a single cluster, but rather found in various locations distributed throughout the chromosome. Nevertheless, many enzymes required for H. pylori LPS biosynthesis have been identified and characterized. These include glycosyltransferases responsible for the addition of the monosaccharide building blocks in the assembly of the O polysaccharide [4], as well as several proteins involved in the synthesis and modification of the lipid A-core [10]. The pathway used for the assembly and translocation of the O antigen in H. pylori remained uncharacterized.

In all characterized LPS biosynthetic pathways, the O polysaccharide is assembled onto the undecaprenyl phosphate (UndP) lipid carrier by specific glycosyltransferases located in the cytoplasmic compartment of the bacteria [1]. Several initiating enzymes have been characterized that transfer a sugar phosphate from a nucleotide activated donor to UndP, forming a pyrophosphate linkage. One of the common initiating enzymes is WecA, a UDP-GlcNAc:undecaprenyl-phosphate GlcNAc-1-phosphate transferase [11],[12]. Other glycosyltransferases sequentially add monosaccharides at the non-reducing end of the growing glycan chain. The lipid-linked glycan is subsequently translocated to the periplasm where the O polysaccharide is transferred from undecaprenyl pyrophosphate (UndPP) onto the lipid A-core. This last step is catalyzed by the O antigen ligase WaaL.

Three LPS biosynthesis pathways are known to date [1]. They are distinguished by three different mechanisms for O antigen polymerization and translocation. In the polymerase-dependent pathway, only short O antigen subunits are assembled in the cytoplasm. These subunits are translocated to the periplasm by the flippase Wzx, where they are polymerized by Wzy with assistance of the chain length regulator Wzz, before the complete O antigen is transferred to the lipid A-core. In the two remaining pathways, the ABC transporter-dependent and the synthase-dependent pathway, the entire O polysaccharide is synthesized at the cytoplasmic side of the inner membrane. The flippase in the ABC transporter-dependent pathway consists of two different polypeptides, Wzm and Wzt. Wzm forms a channel in the inner membrane for the passage of the lipid-linked O antigen, and Wzt provides energy through its ATPase activity. The C-terminal domain of Wzt is required for substrate recognition, and often displays specificity towards the structure of the endogenous O chain [13]. In the third pathway, the key enzyme is the synthase WbbF, which has glycosyltransferase activity and is also required for the translocation of the UndP-linked O antigen to the periplasm [1]. Some exopolysaccharides and capsules are synthesized via pathways that resemble one of these three LPS biosynthesis pathways [14].

In some Gram negative bacteria, including Campylobacter jejuni which is closely related to H. pylori, the cell surface is covered with lipooligosaccharides (LOS) instead of LPS [1]. LOS and LPS are equivalent macromolecules; however, LOS lacks the O polysaccharide and is limited to a short oligosaccharide bound to the lipid A-core [1]. Generally, the oligosaccharide moiety is directly assembled onto the lipid A in the cytoplasm and UndP is not required for LOS biosynthesis.

The goal of this investigation was to determine the pathway used by H. pylori for the assembly of the Lewis antigens onto the lipid A-core. We found that these polysaccharides are assembled as typical O antigens onto the UndP carrier. Surprisingly, for the membrane translocation of the lipid-linked glycan, H. pylori employs an enzyme which has not been previously found to be involved in LPS synthesis, but instead is used by other bacteria in the biosynthesis of N-glycoproteins. This translocase, named Wzk, has no strict structural requirement for its substrates, a characteristic that enables H. pylori to produce O antigens of various structures and lengths according to the phenotype of the infected host.

Results

The H. pylori genome encodes common LPS biosynthesis enzymes: WecA and WaaL

In order to identify genes possibly involved in H. pylori LPS biosynthesis, a genome search was performed using the sequences of enzymes known to participate in LPS biosynthetic pathways. The search resulted in the identification of homologs of the E. coli wecA and waaL genes. The proteins encoded in the H. pylori genes JHP1488 in strain J99 and HPG27_1518 in strain G27 are 22% identical to E. coli WecA and 94% identical to each other. The genes JHP0385 and HPG27_389 encode polypeptides which are 19% identical to the O antigen ligase WaaL and 95% identical to each other. The overall homology between WecA and WaaL sequences from different organisms is low. Nevertheless these proteins, including the H. pylori homologs identified, share similar membrane topologies and a few conserved key residues. Alignments of the protein sequences are shown in Figure S1 and S2. Intriguingly, the H. pylori genome seemed to lack homologs of wzx, wzt, wzm or wbbF, which encode the flippase proteins involved in O antigen translocation in the known pathways. Furthermore, sequences encoding an O antigen polymerase Wzy, or a chain length regulator Wzz could not be found. Thus, the canonical LPS pathways are incomplete in H. pylori.

To address whether the identified genes were indeed involved in H. pylori LPS biosynthesis, mutants in both H. pylori strains, J99 and G27, were constructed by inserting a chloramphenicol-resistance cassette into the putative wecA and waaL open reading frames. For the generation of complemented strains, each gene was re-introduced into the recA gene on the chromosome of the corresponding mutant strain. This location in the genome was selected to prevent further recombinations, a procedure expected to stabilize the mutations. We took advantage of the H. pylori natural competence for the construction of the mutant strains. Interestingly, this procedure was not successful for the generation of complemented strains, as no colonies were recovered on the selective plates after transformation. However, complemented cells were efficiently obtained by electroporation.

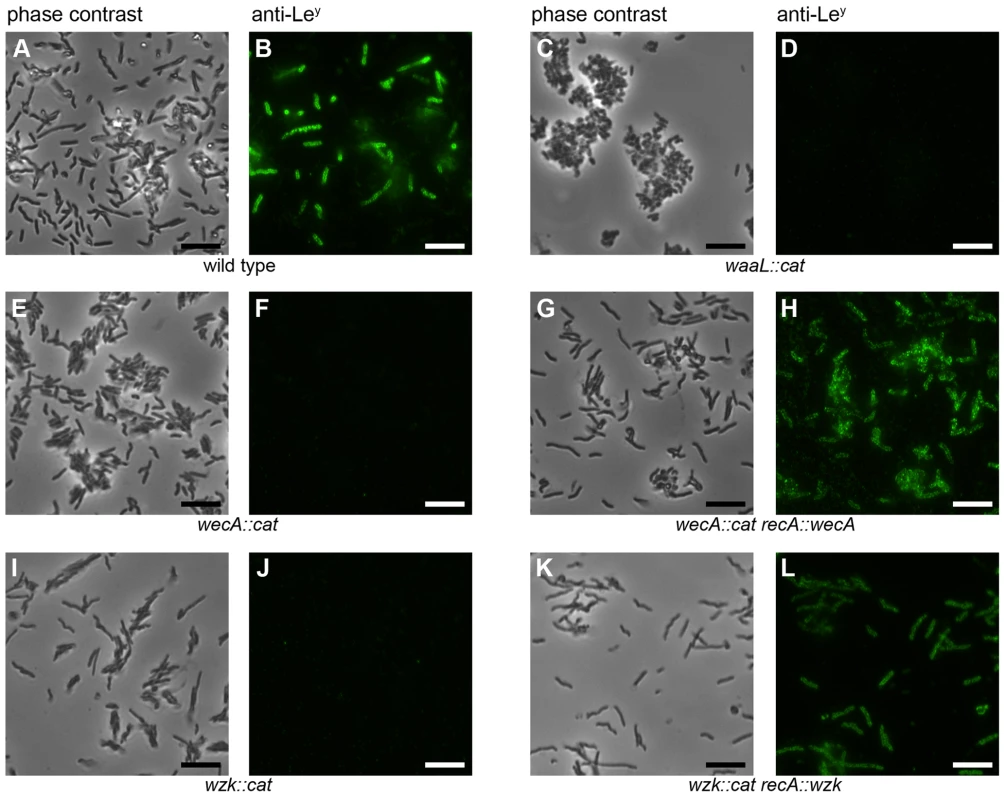

Monoclonal antibodies reacting with Lewis antigens were used to visualize the presence or absence of O antigens on the cell surfaces by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 1). Not all wild type cells reacted with the antibody (Figure 1B). This is due to the high frequency of phase variation in the fucosyltransferase genes (0.2–0.5%) reported by Appelmelk et al. [15]. Lewis antigens could also be detected on flagella (Figure S3), confirming the presence of LPS in the membranous sheaths covering these organelles [16]. This was shown previously by electron microscopy [17] but, to our knowledge, not by fluorescence microscopy. Importantly, all the mutant cells were devoid of Lewis antigens (Figure 1D, F), suggesting the participation of the putative WecA and WaaL in H. pylori LPS biosynthesis.

Fig. 1. H. pylori wecA, waaL and wzk mutant cells display no Lewis antigens.

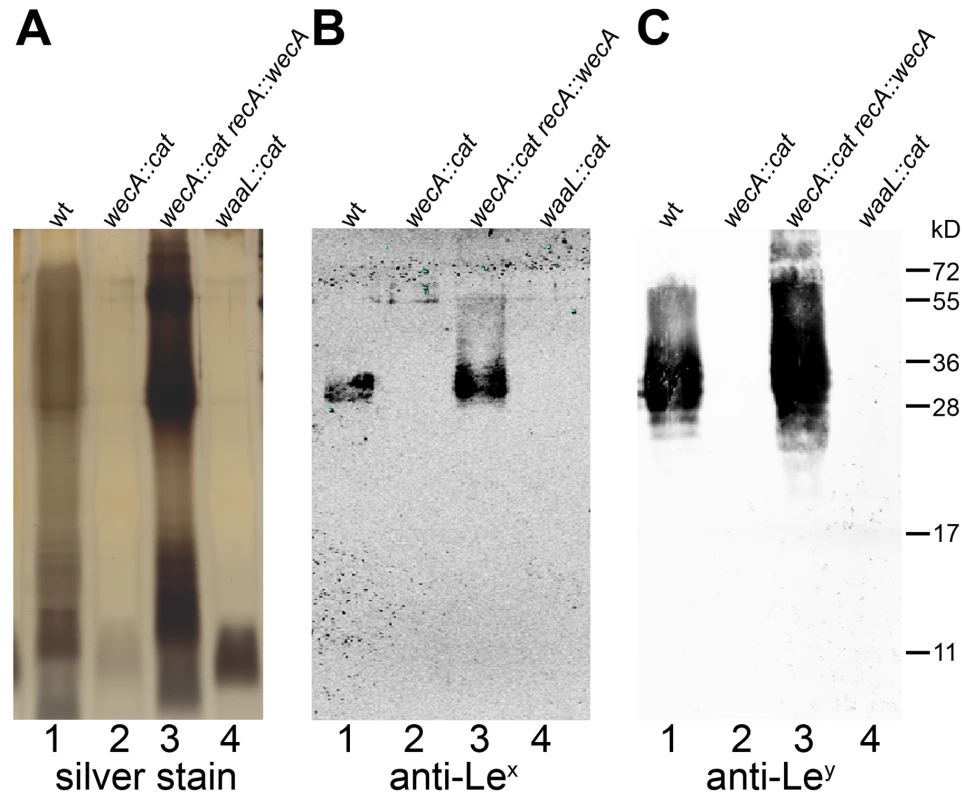

Fluorescence microscopy of H. pylori G27 was performed using monoclonal antibodies against Lewis antigens. Panels A, C, E, G, I and K show phase contrast images, whereas panels B, D, F, H, J and L show bacteria displaying Ley based on reaction with the anti-Ley antibody. Equivalent results were obtained with the anti-Lex antibody (not shown). Lewis antigens are not present on all wild type H. pylori cells due to phase variable fucosyltransferases. The bars in the lower right corners of the pictures indicate 10 µm. The images are representative for the results obtained from three independent experiments. To obtain further evidence for the involvement of the putative WecA and WaaL in H. pylori LPS biosynthesis, the LPS of all strains was purified, separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining (Figure 2A) and Western blotting, using monoclonal anti-Lex (Figure 2B) and anti-Ley antibodies (Figure 2C). Only rough LPS without O chains and Lewis antigens was produced by the mutant strains (Figure 2, lanes 2, 4), demonstrating that both targeted genes are essential for O antigen display. However, whereas the complementation of the putative wecA mutants was successful, the production of smooth LPS was restored only at minimal levels after reintroduction of the putative waaL gene into the chromosome of the waaL mutant strain (Figure S4).

Fig. 2. LPS of H. pylori wecA and waaL mutant strains contains no O antigens.

Purified LPS of (1) H. pylori G27 wild type, (2) wecA mutant, (3) wecA complemented and (4) waaL mutant strains were analyzed by (A) silver staining, and Western blotting using (B) monoclonal anti-Lex and (C) monoclonal anti-Ley antibodies. Protein marker standards were included for reference. Unlike the smooth LPS of the wild type and complemented strains, mutants expressed lipid A-core without O antigens. Comparable results were obtained with purified LPS from H. pylori J99 strains (not shown). Based on the evidence presented we annotated JHP1488 and HPG27_1518 as wecAHP. Similarly, JHP0385, as well as HPG27_389 were named waaLHP.

WecAHP is active in E. coli

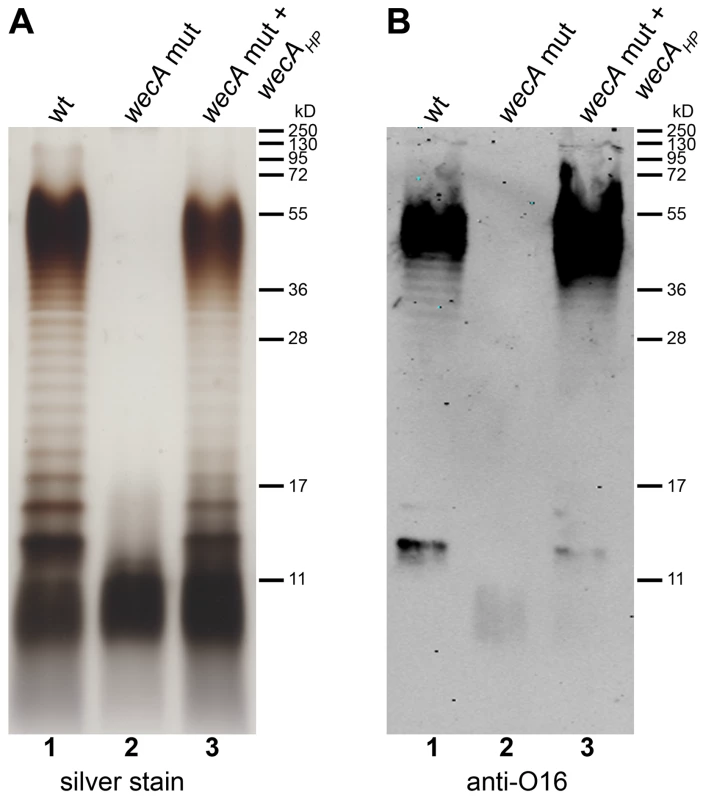

The availability of E. coli strains with specific mutations in LPS biosynthesis genes allowed us to test for activity of WecAHP and WaaLHP by recombinant expression in these mutant strains. E. coli strains carrying either a mutation in wecA or waaL were transformed with plasmids carrying the corresponding H. pylori homolog gene (pIH22 and pIH52, respectively). As shown in Figure 3, wecAHP complemented O antigen synthesis in the E. coli wecA mutant, which confirms its role as a UDP-GlcNAc: undecaprenyl-phosphate GlcNAc-1-phosphate transferase.

Fig. 3. Demonstration of WecAHP activity in E. coli.

Purified LPS from (1) E. coli parental strain W3110 transformed with pMF19, encoding a functional rhamnosyltransferase, (2) E. coli wecA mutant strain CLM37 transformed with pMF19 and empty vector pEXT20 and (3) CLM37 transformed with pMF19 and pIH22 containing wecAHP, were analyzed by (A) silver staining and (B) Western blotting using an antibody recognizing the E. coli O16 antigen. Protein marker standards were included for reference. On the contrary, although WaaLHP could be expressed in E. coli, it was unable to restore smooth LPS production in an E. coli waaL mutant (data not shown). The transfer of O antigens onto the lipid A-core generally requires a strain specific core structure, and heterologous expression of O antigen ligases is therefore often not functional [1],[18],[19]. E. coli and H. pylori core regions are structurally different [20], which could explain the lack of activity of WaaLHP in E. coli.

H. pylori WaaL is active in vitro

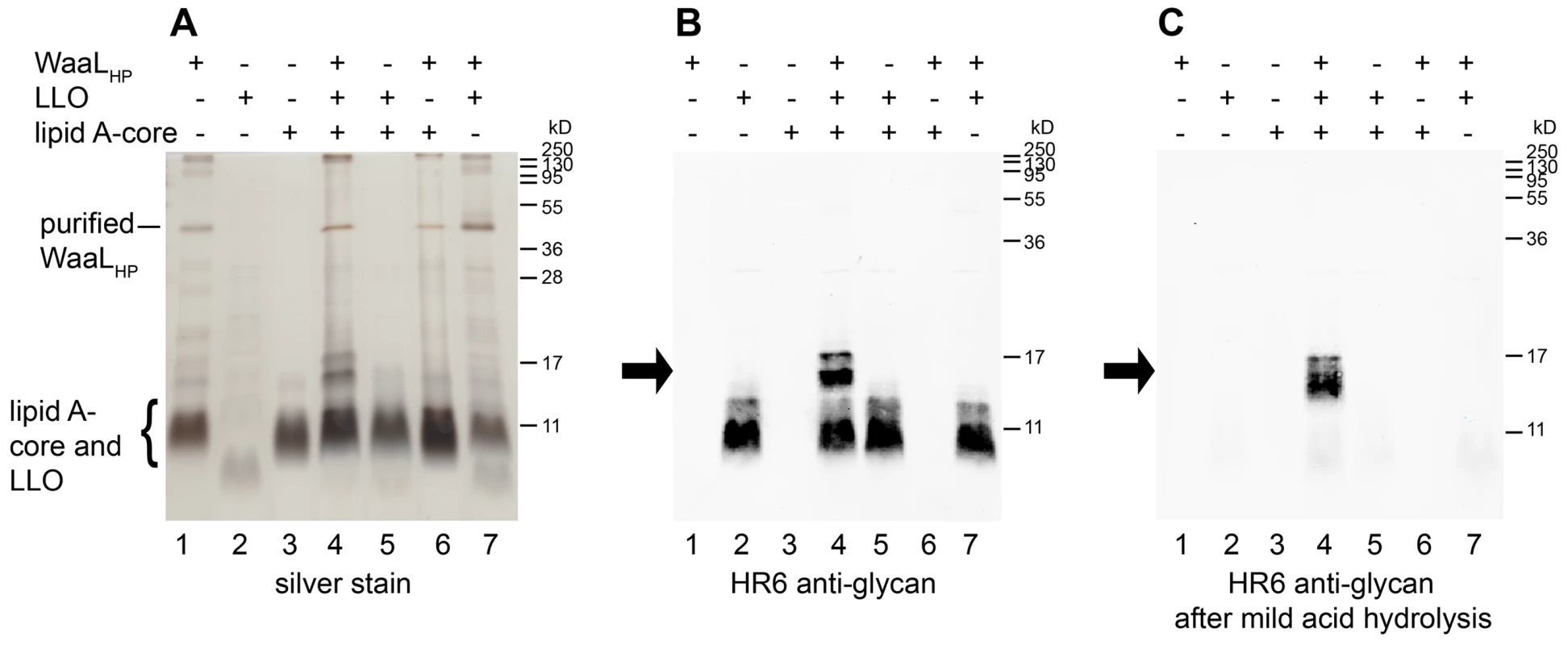

As full complementation of the H. pylori waaLHP mutant strain could not be achieved and the enzyme was not functional with the E. coli lipid A-core as an acceptor, we tested O antigen ligation activity by performing an in vitro assay. WaaLHP containing a C-terminal deca-His tag (encoded in pIH52) was expressed in the E. coli waaL mutant strain CLM24 [21]. Expression in this strain was selected to prevent possible contamination with the E. coli O antigen ligase. Membranes containing the enzyme were solubilized with detergents and WaaLHP was purified by nickel affinity chromatography as described in Material and Methods (Figure S5). As the band corresponding to purified protein had an apparent molecular weight of about 36 kD instead of the expected 50 kD, the identity of the polypeptide was confirmed by mass spectrometry. As seen with silver staining (Figure 4A, lane 1), lipid A-core from E. coli co-purified with the H. pylori ligase. Lipid A-core from the H. pylori waaLHP mutant strain was purified and used as an acceptor structure. O antigen ligases typically show relaxed specificity towards the structure of the O polysaccharide [1], a property that allows the use of diverse UndPP-linked glycans as substrates for the in vitro assay. Due to the presence of multiple bands, LPS containing a polymerized O antigen is often indistinguishable from the corresponding UndPP-bound O antigen in SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. We reasoned that the use of a short oligosaccharide of defined length would facilitate the interpretation of results. Therefore, the UndPP-linked heptasaccharide derived from the C. jejuni N-linked protein glycosylation pathway was selected as substrate. This lipid-linked glycan can be synthesized in E. coli cells carrying the plasmid pACYCpglBmut [22], which contains all the enzymes required for the assembly of the heptasaccharide, and has been successfully shown to be a suitable substrate for in vitro glycosylation [23],[24].

Fig. 4. Demonstration of WaaLHP activity in vitro.

Mixtures with purified WaaLHP, H. pylori lipid A-core (acceptor) and C. jejuni UndPP-linked heptasaccharide (LLO; substrate) were incubated overnight. (1) WaaLHP only, (2) substrate only, (3) acceptor only, (4) all components, (5) no WaaLHP, (6) no substrate, (7) no acceptor. Reaction products were detected by (A) silver staining and (B) Western blotting using an antibody reactive against the C. jejuni heptasaccharide (HR6). (C) Western blotting after removal of the substrate by mild acid hydrolysis confirmed the presence of heptasaccharide attached to lipid A-core, as this reaction product is not affected by the acid treatment. Arrows indicate the reaction product. Contaminating E. coli lipid A-core co-purified with WaaLHP (A, lane 1, 4, 6, 7). Note that the E. coli and H. pylori lipid A-cores as well as the C. jejuni LLO present similar electrophoretic mobilities. Protein marker standards were included for reference. All reactants were mixed and incubated at 37°C overnight. Reaction products appeared as bands of higher molecular weight in SDS-PAGE (Figure 4A, lane 4) and positively reacted with the HR6 antibody, which recognizes the C. jejuni heptasaccharide (Figure 4B, lane 4). The reaction mixtures were subjected to mild acid hydrolysis. In such conditions, the reaction product is stable, whereas the substrate is hydrolyzed (Figure S6). After acid hydrolysis, the HR6-reacting bands corresponding to LPS were still present (Figure 4C, lane 4), whereas the bands corresponding to the UndPP-linked heptasaccharide substrate were no longer observed (Figure 4C, lanes 2, 4, 5, 7). These results demonstrated the successful transfer of the C. jejuni heptasaccharide onto the H. pylori lipid A-core acceptor, thereby confirming the O antigen ligase activity of WaaLHP. The E. coli lipid A-core present in the fraction containing the recombinant H. pylori ligase was not an appropriate WaaLHP acceptor, as activity was dependent on the presence of H. pylori lipid A-core (Figure 4, lanes 4, 7).

It is notable that unlike the O antigen ligase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa [19], WaaLHP did not require ATP as an energy source. The presence or absence of ATP in the in vitro reaction did not noticeably affect ligation efficiency (Figure S7).

H. pylori encodes an O antigen translocase usually involved in protein N-glycosylation

From the previous experiments we concluded that the H. pylori Lewis antigens are synthesized onto the UndPP carrier via a pathway initiated by WecAHP and involving WaaLHP for the transfer of the glycans onto the lipid A-core. It was puzzling that no gene encoding one of the common O antigen translocases could be found in the H. pylori genome. Therefore, we searched for the presence of alternative flippases belonging to other biosynthetic pathways.

A gene homolog to pglK (formerly named wlaB) which encodes a flippase involved in the translocation of the UndPP-linked heptasaccharide during protein N-glycosylation in C. jejuni [25] was found in the H. pylori genome. The genes annotated as JHP1129 in strain J99 and HPG27_1153 in strain G27 encode polypeptide sequences which are 97% identical to each other and share 37% identity with C. jejuni PglK (see alignments in Figure S8). No evidence for the presence of N-glycoproteins has been found in H. pylori, and therefore, the homolog of C. jejuni PglK was our principal candidate as the H. pylori O antigen translocase.

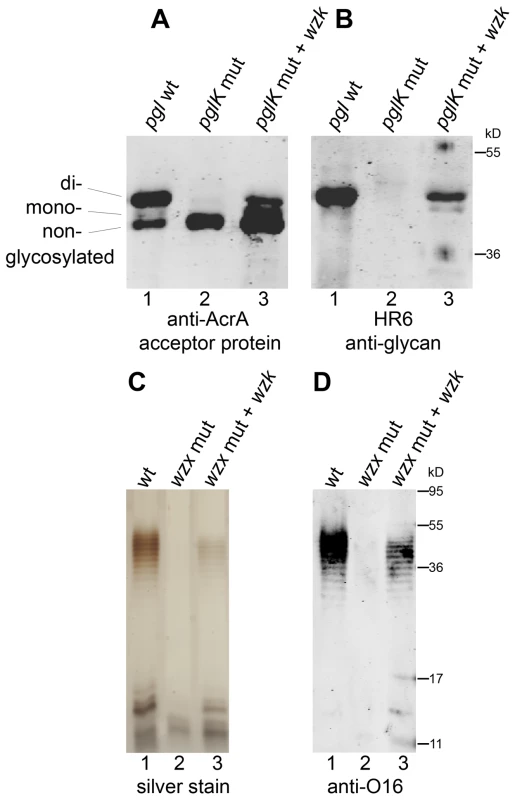

We investigated the flippase activity of the putative H. pylori translocase through complementation experiments in E. coli described by Alaimo et al. [25]. A gene cluster encoding the complete C. jejuni N-linked protein glycosylation machinery, which includes the PglK flippase, was introduced into an E. coli mutant strain devoid of known glycan flippases. These cells were also transformed with plasmid pIH18 expressing AcrA, a C. jejuni acceptor protein that carries two N-glycosylation sites. Glycosylation of AcrA in E. coli was detected through the appearance of two extra bands of higher molecular weight in Western blots, immunoreactive to the AcrA and the C. jejuni glycan-specific HR6 antibodies (Figure 5A, B). Glycosylation of AcrA was abolished when the translocase PglK was absent (Figure 5A, B, lane 2), but was restored in the presence of the putative H. pylori translocase encoded in pIH23 (Figure 5A, B, lane 3), indicating that the activities of PglK and its H. pylori homolog (named Wzk, according to the current official nomenclature of LPS genes [26]) are interchangeable. Further evidence of the Wzk translocase activity was obtained by demonstrating its capability to restore the flipping of O antigen in an E. coli wzx mutant strain (Figure 5C, D, lane 3). Taken together, these results indicate that Wzk is a translocase for UndPP-linked glycans, equivalent to PglK. Structurally different glycans were translocated by Wzk (Figure S9), indicating a relaxed substrate specificity of this enzyme.

Fig. 5. H. pylori has a flippase able to translocate diverse UndPP-linked glycans.

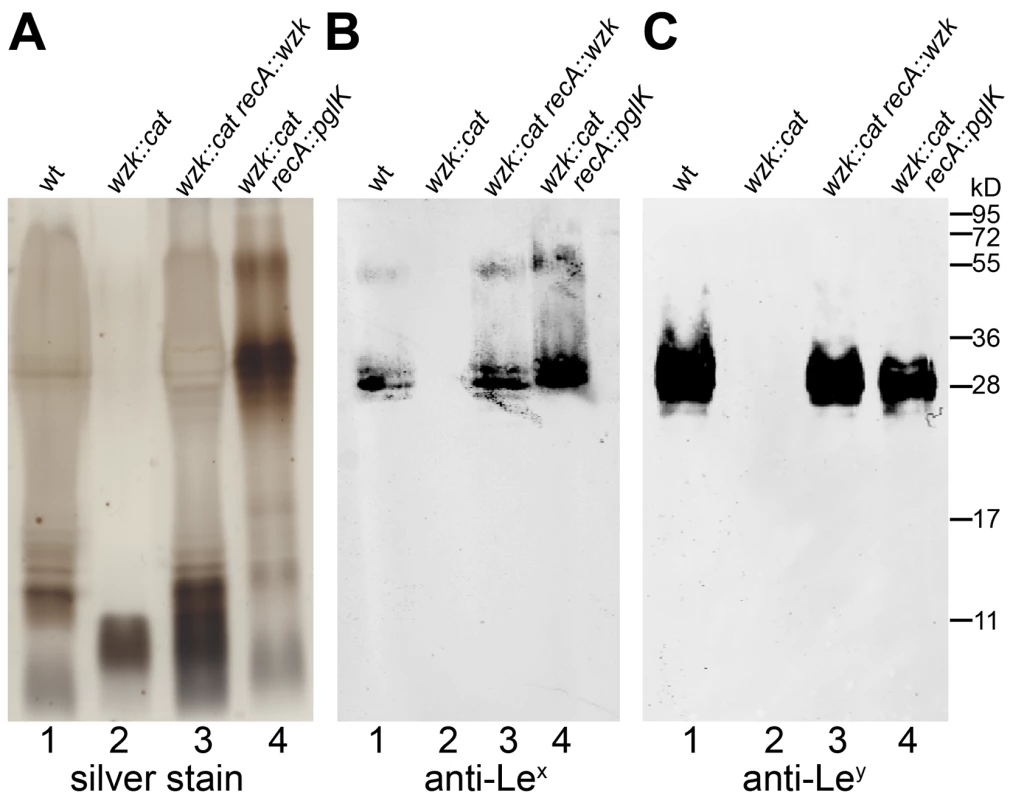

Activity of the H. pylori translocase was examined with complementation assays in flippase deficient E. coli. (A, B) Glycosylation of the acceptor protein AcrA in the N-glycosylation pathway of C. jejuni was analyzed by Western blotting with (A) anti-AcrA antibody and (B) an antibody (HR6) recognizing the C. jejuni glycan. C. jejuni pglK was (1) functional, (2) mutated, or (3) mutated and complemented by H. pylori wzk. (C, D) Purified LPS of E. coli strains containing (1) a functional flippase Wzx, (2) a wzx mutation or (3) a wzx mutation complemented by wzk, was visualized by silver staining and Western blotting using an antibody recognizing the E. coli O16 antigen. Protein marker standards were included for reference. To demonstrate the involvement of Wzk in H. pylori LPS biosynthesis, the wzk gene was mutated as described previously for wecAHP and waaLHP. Fluorescence microscopy showed that Lewis antigens were not present on the surface of H. pylori wzk mutant cells (Figure 1J). The absence of Lex and Ley antigens on purified LPS from the mutant strain was shown by Western blot analysis (Figure 6B, C, lane 2). SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining showed that the LPS of the wzk mutant did not contain O antigens (Figure 6A, lane 2). Upon complementation with either wzk or its homolog pglK, the synthesis of smooth LPS was restored (Figure 6, lanes 3, 4). Taken together, these results demonstrated that Wzk is an essential component in the LPS biosynthesis pathway in H. pylori, responsible for the translocation of the O antigen. Although in their native hosts PglK and Wzk participate in different pathways, both enzymes can be functionally exchanged, being able to translocate glycans of diverse structures and lengths.

Fig. 6. Wzk is the H. pylori O antigen flippase and can be replaced by C. jejuni PglK.

Purified H. pylori LPS was analyzed by (A) silver staining and Western blotting using (B) anti-Lex and (C) anti-Ley monoclonal antibodies. Lane 1 shows smooth LPS extracted from wild type H. pylori G27 cells; lane 2 LPS from the G27 wzk mutant strain not containing O antigens; smooth LPS production is restored in the wzk complemented strain shown in lane 3. Shown in lane 4: the C. jejuni flippase PglK can functionally complement the H. pylori Wzk, and restore a smooth LPS phenotype in the H. pylori G27 wzk mutant. Protein marker standards were included for reference. O antigen is not required for H. pylori motility

Our fluorescence microscopy experiments allowed us to confirm the presence of LPS on the membranous sheaths covering H. pylori flagella, raising the possibility of a connection between LPS integrity and motility. We tested this hypothesis by comparing the swimming activity of the O antigen deficient strains relative to the wild type strains. After growth on soft agar plates, no significant difference between the diameters of colony expansion was detected (results not shown). It was concluded that the absence of O antigens in the H. pylori LPS has no adverse effect on flagellar function in vitro.

H. pylori O antigen mutation may adversely affect selected type IV secretion systems

As mentioned above, the protocol for natural DNA uptake was not successful in the construction of the complemented strains. One possible reason is a reduced natural competence of the H. pylori O antigen mutants. The natural competence of H. pylori depends on the ComB type IV secretion system [27]. As H. pylori possesses additional type IV secretion systems, we examined if the presence of O antigens on the bacterial surface might be required for the function of these machineries. One additional H. pylori type IV secretion system is encoded in the cag pathogenicity island [28]. The presence of this gene cluster in H. pylori correlates with enhanced virulence, as the Cag type IV secretion system builds a needle-like device for the injection of a single known effector protein, CagA, directly into the host cells. Within the host, CagA is tyrosine phosphorylated and interferes with cell signaling pathways [28].

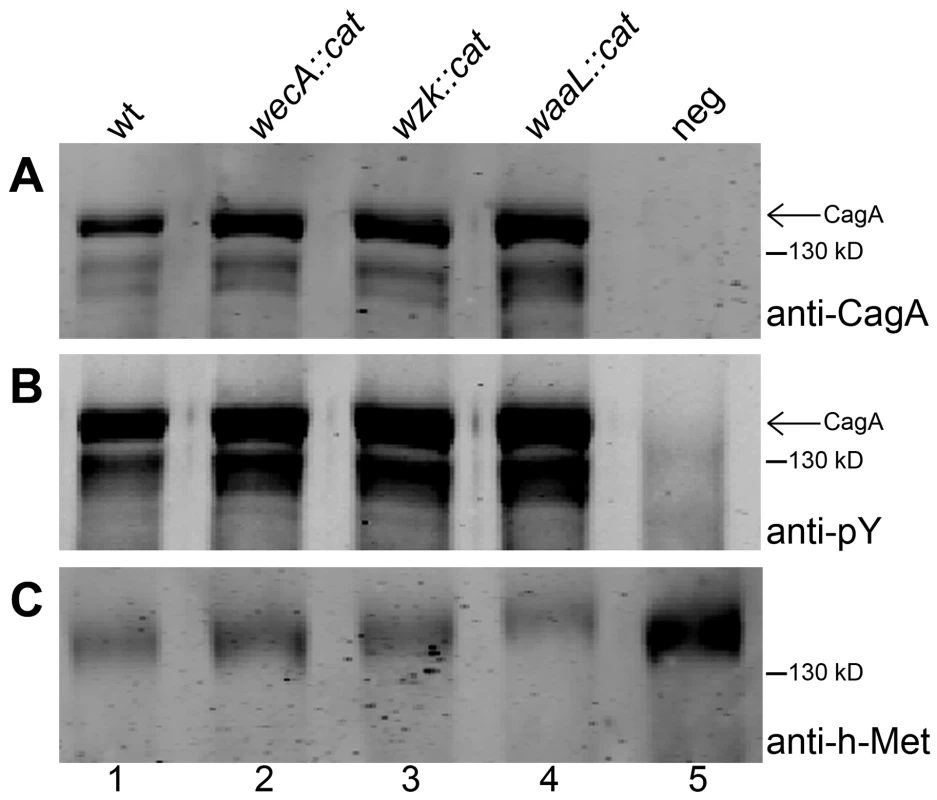

We compared the efficiency of CagA injection into human gastric epithelial cells between wild type and O antigen mutant H. pylori strains. AGS gastric epithelial cells were infected with H. pylori cells from an overnight grown liquid culture. Cells were harvested four hours after infection, when many epithelial cells displayed an elongated morphology, a typical effect following CagA translocation [28]. AGS cell membrane fractions were collected and analyzed by Western blotting, using anti-CagA (Figure 7A) and anti-phosphotyrosine (Figure 7B) antibodies. All H. pylori strains injected similar amounts of CagA. We concluded that mutations interfering with the synthesis of smooth LPS in H. pylori may reduce natural competence, but do not affect type IV secretion systems in general.

Fig. 7. CagA translocation is functional in O antigen negative H. pylori strains.

Human gastric epithelial AGS cells were infected with H. pylori G27 (1) wild type, (2) wecA mutant, (3) wzk mutant, or (4) waaL mutant strains. (5) Non-infected AGS cells served as negative control. AGS membranes were examined for translocation and tyrosine phosphorylation of CagA by Western blotting using (A) anti-CagA antibody and (B) anti-phosphotyrosine (pY) antibody. (C) The host membrane marker h-Met was detected with an anti-h-Met antibody for a loading control. Arrows indicate full length phosphorylated CagA. A protein marker standard was included for reference. Discussion

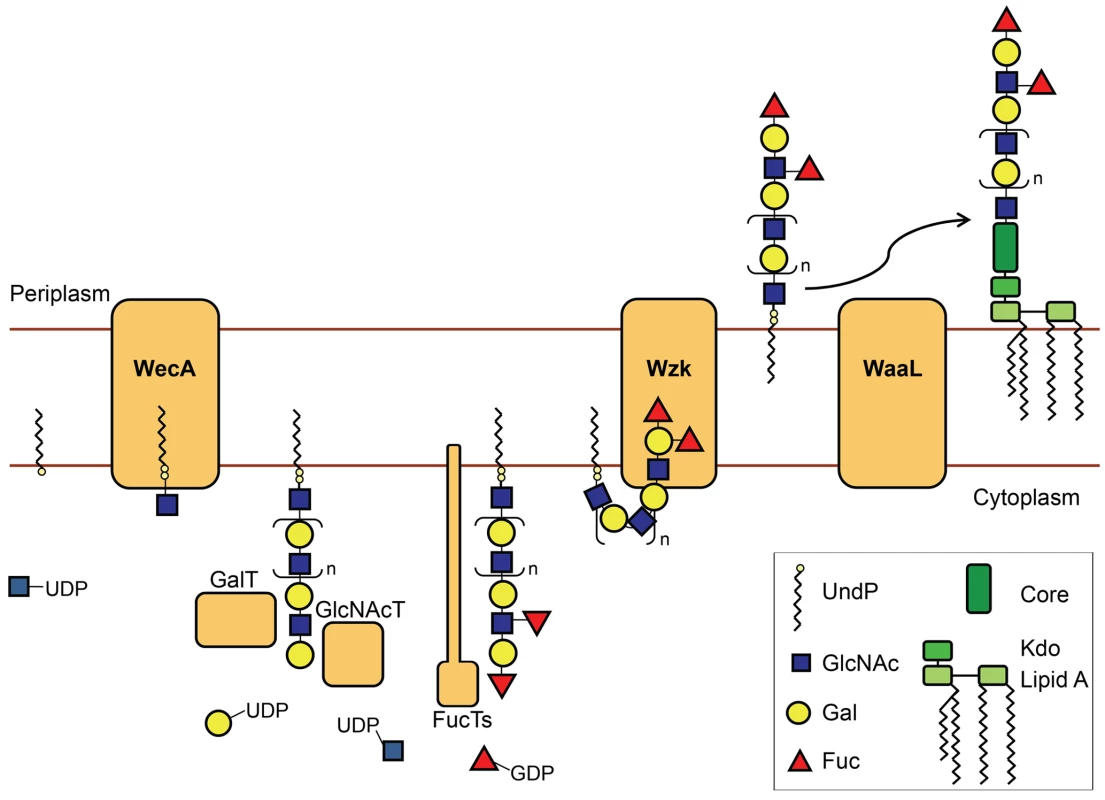

With the display of Lewis antigens on the O chains, the LPS plays a unique role in H. pylori colonization. The fact that the genes involved in LPS biosynthesis are not grouped in a single locus in the H. pylori chromosome is probably one of the reasons why the pathway for the biosynthesis of this key macromolecule remained to be determined. The objective of this investigation was to elucidate the LPS biosynthetic pathway in H. pylori. Genomic analysis revealed that none of the previously characterized pathways for LPS biosynthesis is complete in H. pylori, suggesting that this bacterium uses an alternative strategy. One possibility was that the synthesis of LPS took place directly on the lipid A-core as it occurs with the LOS biosynthesis in C. jejuni and Neisseria spp. [1]. However, using a combination of genetic, biochemical and microscopy techniques, we showed that the O antigen is assembled onto a polyisoprenoid lipid carrier. Figure 8 illustrates our model of H. pylori LPS biosynthesis. WecAHP initiates this pathway by transferring a GlcNAc-phosphate from UDP-GlcNAc to UndP. The resulting molecule, UndPP-GlcNAc, serves as an acceptor for the assembly of the O chain backbone, composed of alternating GlcNAc and Gal residues. Some of these linear polysaccharides are decorated at selected locations through the activity of various fucosyltransferases, producing the Lewis antigens [4]. After translocation to the periplasm by Wzk, the O chain is attached onto the lipid A-core acceptor by the action of the O antigen ligase WaaLHP.

Fig. 8. Novel LPS biosynthesis pathway in H. pylori.

The figure shows a simplified illustration of the H. pylori LPS biosynthesis pathway. The H. pylori O chains are assembled in the cytoplasm onto a polyisoprenoid membrane anchor. The O antigen synthesis is initiated by the UDP-GlcNAc: undecaprenyl-phosphate GlcNAc-1-phosphate transferase WecA. Processive glycosyltransferases alternately add Gal and GlcNAc residues, producing the linear O chain backbone. Fucosyltransferases then attach Fucose residues on selected locations of the O antigen backbone, generating Lewis antigens. The flippase Wzk transfers the O polysaccharide to the periplasm, where it is attached onto the lipid A-core by the action of the O antigen ligase WaaL. The LPS molecule can then be transported to the outer leaflet of the H. pylori outer membrane. H. pylori LPS biosynthesis follows a novel pathway, differing from all the established LPS pathways in the translocation of the O chain. We found that this step is accomplished by Wzk, which is not related to any described translocase involved in O antigen synthesis. Instead, Wzk is homolog to C. jejuni PglK, responsible for UndPP-heptasaccharide flipping during protein N-glycosylation. Wzk and PglK are related to the lipid A-core flippase MsbA, with the closest sequence similarity among known ATP transporters. ATPase activity of PglK has been reported by Alaimo et al. [25]. As the C-terminal Walker domains are well conserved between PglK and Wzk, Wzk most likely also possesses ATPase activity. All ABC transporter-dependent LPS pathways described to date require two polypeptides, Wzm and Wzt, for the translocation of the O chains [1]. The only homology of these proteins to Wzk is found in the ATP binding domains of Wzt. Wzm possesses several transmembrane domains and is proposed to form a channel in the inner membrane. Wzt provides the energy for the flipping mechanism through its ATPase activity. In H. pylori, the flippase Wzk is the only polypeptide required and sufficient for translocation of UndPP-linked glycans. The ability of Wzk to translocate Lewis antigens, the C. jejuni heptasaccharide, as well as the E. coli O16 antigen, demonstrates that Wzk activity is independent of the length or the composition of the translocated UndPP-linked sugars.

In most bacteria, the genes involved in O antigen biosynthesis are clustered in a single locus, which facilitates horizontal gene exchange and regulation of O antigen synthesis [1]. In contrast, the three genes investigated in this work, as well as the other genes involved in O antigen biosynthesis in H. pylori, are located in separate loci dispersed along the chromosome. H. pylori exhibits a high rate of DNA uptake and genetic variability [29]. An independent location of the genes requires individual gene regulation, which could be beneficial for H. pylori by allowing more diversity and flexibility in the LPS structure. It is particularly intriguing that the position of the H. pylori wzk gene is located in close proximity to tRNA genes, which are known to be hot-spots for the insertion of mobile genetic elements [30]. On the contrary in C. jejuni, PglK is encoded as part of the pgl-cluster, responsible for N-linked protein glycosylation [22]. Interestingly, the oligosaccharyltransferase PglB, also encoded in the pgl-locus, has homologs in eukaryotes and archaea but not in H. pylori, which does not possess this general glycosylation machinery [31]. Different scenarios can be advanced to describe the origin of the Wzk-like translocases. H. pylori may have discarded its pgl-cluster, yet retained wzk to act on the synthesis of LPS. Alternatively, the wzk gene could have been adopted by other epsilon - or delta proteobacteria to produce N-glycoproteins. Subsequently, some of these organisms, like C. jejuni, may have lost their LPS cluster, producing LOS instead. In either case, bacteria appear to favor the dedication of their lipid-linked glycans exclusively to one biosynthetic pathway, either protein glycosylation or LPS biosynthesis.

We encountered difficulties with natural transformation of O antigen mutant H. pylori cells and electroporation was required for the construction of strains for complementation experiments. One possible explanation is a loss of natural competence for DNA uptake. A similar observation has been reported for a C. jejuni LOS mutant strain [32]. However, in another study C. jejuni LOS and capsule mutants displayed increased DNA uptake ability [33]. Although the exact role of O chains in H. pylori natural competence remains unclear, we demonstrated that the presence of O antigens does not have a general inhibitory effect on H. pylori type IV secretion systems, because the type IV secretion apparatus encoded in the cag pathogenicity island was functional in O chain deficient H. pylori mutants. Alternatively, the lack of O antigens may induce a stress response, resulting in the induction of DNA restriction enzymes, which could digest the foreign DNA before or after uptake into the cells.

Due to the presence of LPS on the H. pylori flagella, we investigated the possible role of O antigens in motility. H. pylori mutant strains were not defective in in vitro swimming motility compared to wild type strains. However, the presence of LPS on the flagellar surface may still play a role in vivo. The O antigens may have a protective function by shielding the flagella against components of the host immune defense, and by actively down-regulating flagellin-specific activation of the innate immune system via the interaction between Lewis antigens and DC-SIGN.

A central role of the Lewis antigens in H. pylori pathogenicity is their interaction with DC-SIGN, which results in modulation of the host immune defense [5]. As Lewis antigen expression is phase variable due to the reversible switching off of the fucosyltransferases, H. pylori maintains a balance between activation and repression of the host immune system [9]. In addition, the fucosylated locations along the O chain backbone are finely adapted to the host phenotype [8]. With this mechanism, a permanent infection can be established, which in rare cases results in gastric cancer. The O antigen translocase Wzk, which we show here is essential for the cell surface expression of Lewis antigens, could be an attractive target for the design of antibiotics effective against H. pylori and possibly C. jejuni infections.

Interestingly, Wzk is the first protein common to both, LPS biosynthesis and protein N-glycosylation, supporting an evolutionary connection between these pathways.

Materials and Methods

Genome analysis

NCBI BLASTP (default settings) was used for the search of putative WecA, WaaL and lipid-linked glycan translocase polypeptide sequences encoded in the H. pylori genome. Global sequence identities were calculated with LALIGN (default settings, global) (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/LALIGN_form.html).

PCR and plasmid construction

Oligonucleotides used for DNA amplification are listed in Table S1.

Plasmids containing wecAHP

For the construction of pIH22, wecAHP was amplified by PCR, using the primers WecAHPEcoRIfw and WecAHPH6XbaIrv and genomic DNA from H. pylori J99 as template. The wecAHP PCR product was cloned into pEXT20 [34], using the restriction enzymes EcoRI and XbaI (all restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs unless indicated otherwise). pIH22 was used for the expression of WecAHP in E. coli.

The primers WecA_forward and WecA_reverse were used to amplify wecAHP from H. pylori J99, which was cloned into pGEM-T (Promega), generating pGEM-HPwecA. The obtained plasmid was digested with SgfI (Promega), which is cutting the open reading frame of wecAHP. Blunt ends were generated with a Klenow fragment (New England Biolabs). Insertion of a chloramphenicol-resistance cassette (CAT), derived from plasmid DT3072 [35] after digestion with HincII, resulted in pGEM-HPwecA-CAT, which was used in the construction of H. pylori wecA::cat.

The J99 wecAHP gene was amplified with the primers NdeIHPJ99wecAfw and HPJ99wecAH6BamHIrev. The PCR product was ligated into vector pGEM-T easy (Promega), resulting in plasmid pIH27, which was subsequently digested with NdeI and BamHI and cloned into vector pSK+recxorf8-flag [36] to obtain pIH42. pIH42 was used in the construction of H. pylori wecA::cat recA::wecA.

Plasmids containing waaLHP

Genomic DNA from H. pylori J99 was used as template for the PCR amplification of waaLHP using Ligase_forward and Ligase_reverse primers. The amplified DNA sequence was cloned into pGEM-T, generating pGEM-HPwaaL. The waaLHP gene was subsequently cut with NheI (Invitrogen) and blunt ends were generated using a polymerase Klenow fragment. The CAT cassette was excised from DT3072 using HincII restriction enzyme and inserted into the waaLHP gene of pGEM-HPwaaL, generating pGEM-HPwaaL-CAT, which was used for the construction of H. pylori waaL::cat.

For the construction of pIH53, waaLHP from H. pylori G27 was amplified with primers NdeIG27waaLfw and G27waaLH10BamHIrv. The PCR product and pSK+recxorf8-flag were digested with NdeI and BamHI and ligated. The resulting plasmid pIH53 was used for the construction of H. pylori waaL::cat recA::waaL.

Plasmid pIH53 was digested with NdeI, whereas pEXT20 was digested with EcoRI. Blunt ends were generated with a Klenow fragment and the resulting DNA fragments were further digested with BamHI. Subsequent ligation of the DNA fragments resulted in pIH52, which was used for the expression of WaaLHP in E. coli.

Plasmids containing wzk

The gene encoding the flippase Wzk was amplified from genomic H. pylori J99 DNA using the primers KpnIHPpglKfw and HPpglKH6XbaIrev. The PCR product and pEXT20 were digested with KpnI and XbaI. Ligation of the DNA fragments resulted in pIH23, which was used for the expression of Wzk in E. coli.

The gene wzk in pIH23 was cut with PsiI, and the CAT cassette from HincII-digested DT3072 was inserted by ligation. The resulting plasmid pIH40 was used for the construction of H. pylori wzk::cat.

The wzk gene was excised from pIH23 through digestion with KpnI and PstI restriction enzymes. Plasmid pSK+recxorf8-flag was digested with BamHI and NdeI. After treatment with a Klenow fragment the restriction products were ligated to generate pIH43, which was used for the construction of H. pylori wzk::cat recA::wzk.

Plasmids containing C. jejuni genes

Oligonucleotides NdeICj81116pglKfw and Cj81116pglKXbaIrv were used for the PCR amplification of C. jejuni pglK, with the plasmid pACYCpgl [22] serving as template. The PCR product was digested with NdeI and XbaI and ligated into the vector pSK+recxorf8-flag, treated with the same restriction enzymes, leading to plasmid pIH54, used for the construction of H. pylori wzk::cat recA::pglK.

The gene acrA encoding the glycosylation acceptor protein AcrA from C. jejuni was excised from plasmid pWA2 [21] with SfoI and ZraI for ligation into vector pEXT21 [34], which was digested with SmaI. The resulting plasmid was named pIH18, and used for the expression of AcrA in E. coli.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

H. pylori strains J99 [37] and G27 [38] served as parental strains for the construction of O antigen mutants. H. pylori mutant strains were generated through natural transformation with the plasmids pGEM-HPwecA-CAT for wecA mutants, pGEM-HPwaaL-CAT for waaL mutants and pIH40 for wzk mutants, respectively, resulting in the disruption of the targeted genes through insertion of a chloramphenicol resistance cassette by homologous recombination. Mutant strains were recovered as single colonies after growth on selective plates containing chloramphenicol. Complementation was achieved through electroporation of the mutant strains for the uptake of the plasmids pIH42 for wecA complementation, pIH53 for waaL complementation and pIH43 for wzk complementation, respectively. Following homologous recombination, the complemented genes were inserted into the chromosome of the H. pylori mutant strains, disrupting the recA gene. Complemented colonies were selected on plates containing chloramphenicol and kanamycin. All strains were verified with PCR analysis.

H. pylori strains were grown on brucella broth agar plates, supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, or on brain heart infusion agar with 10% horse serum. The antibiotics vancomycin (5 µg/ml), cycloheximide (100 µg/ml), trimethoprim (10 µg/ml) and amphotericin B (8 µg/ml) were added and cells were incubated at 37°C under micro-aerobic conditions, obtained by adding a CampyGen gas pack (Oxoid) to an anaerobic jar. O antigen mutant strains were selected with chloramphenicol (25 µg/ml). Kanamycin (20 µg/ml) was added for the selection of complemented strains. Liquid cultures were grown overnight in brucella broth supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum and the appropriate antibiotics at 37°C with 160 rpm rotation. E. coli strains were grown overnight in LB broth at 37°C with rotation at 200 rpm.

Fluorescence microscopy

Microscope cover glasses were prepared for the attachment of cells using (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (Sigma) according to Strähle and coworkers [39]. Overnight H. pylori cultures were adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm wave length (OD600) of 1.0 per ml. Cells were washed with PBS and an equivalent of 0.4 OD600 was applied to each cover glass. After 30 min of incubation on ice, the cell suspension was removed and cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Staining and microscopy procedures were conducted as described by Couturier and Stein [40], whereby a monoclonal anti-Ley antibody (1/200) (Calbiochem) and a secondary Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse antibody (1/500) (Molecular Probes) were used for staining.

LPS analysis (immunoblotting/silver staining)

Small scale LPS extraction using hot phenol was performed following the procedure described by Marolda et al. [41], with the exception that ethyl ether was replaced by ethanol for the washing of the LPS pellet. The LPS was run on a 15% SDS-PAGE and visualized by the silver staining method described by Tsai and Frasch [42], or by Western blotting, using monoclonal mouse anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies (Calbiochem), or rabbit anti-O16 antigen antiserum (Statens Institute, Denmark). After incubation with a secondary goat anti-mouse IgM IRDye-800 antibody or a goat anti-rabbit IRDye-800 antibody, respectively (LI-COR Biosciences), the blots were scanned with an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences).

Activity tests in E. coli

E. coli serogroup O16 laboratory strains produce rough LPS without O antigen due to a mutation inactivating the rhamnosyltransferase responsible for the addition of the second sugar residue in the O chain assembly. Smooth LPS production can be restored with the addition of a plasmid pMF19 containing the rhamnosyltransferase gene [43]. E. coli W3110 transformed with pMF19 served as a positive control, producing long chain O16 LPS. E. coli strain CLM37 has a mutation in wecAEC, and therefore is unable to assemble O chains [44]. CLM37 was transformed with pMF19 and empty vector pEXT20 to serve as negative control in the experiment testing for WecAHP activity. WecAHP activity was examined in CLM37 transformed with pMF19 and pIH22.

The E. coli O antigen ligase mutant strain CLM24 was transformed with pMF19 and either pIH52 or pEXT20 for the analysis of WaaLHP activity or for the corresponding negative control, respectively.

To test the ability of H. pylori Wzk to flip UndPP-linked glycans in an N-glycosylation pathway, E. coli strain SCM7 [25] containing mutations in oligosaccharide translocases was transformed with pIH23 (containing wzk), pIH18 (encoding the acceptor protein AcrA) and pACYCpglKmut (encoding the C. jejuni glycosylation machinery with a mutation in the translocase gene pglK [44]). In the negative control strain the empty vector pEXT20 was transformed instead of pIH23. The positive control strain was transformed with pACYCpgl (containing the intact C. jejuni glycosylation machinery) instead of pACYCpglKmut. To further examine if Wzk has O antigen translocase activity, the E. coli flippase mutant strain CLM17 [45] was transformed with pMF19 and pIH23, or the vector control pEXT20.

LPS profiles were analyzed by silver staining as described above. Western blotting was used to determine the glycosylation status in the Wzk activity tests. As primary antibodies, either an anti-AcrA antibody [22], recognizing the acceptor protein, or the antiserum HR6 (S. Amber and M. Aebi, manuscript in preparation), reacting with the C. jejuni glycan, were applied. After incubation with a secondary goat anti-rabbit IRDye680 antibody (LI-COR Biosciences), bands were visualized with an Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences).

Mass spectrometry

The protein band corresponding to the putative WaaLHP was excised from a coomassie stained gel (Figure S5). The protein was in-gel digested using trypsin (Promega) according to Shevchenko et al. [46]. Peptide fragments were eluted from the gel piece, desalted using zip-tipC18 (Millipore) according to the supplier protocol and dissolved in 0.1% formic acid. Peptides were separated with a LC/MSD Trap XCT (Agilent Technologies) and the resulting mass spectrum was used for the identification of the protein by the Mascot search engine (www.matrixscience.com) using the NCBInr database.

WaaL in vitro assay

The E. coli O antigen ligase mutant CLM24 was transformed with pIH52 which encodes waaLHP with a C-terminal deca-histidine tag. Cells were grown overnight at 37°C with 0.2 mM IPTG for the production of the O antigen ligase. The protocol described by Faridmoayer et al. [24] for the purification of an oligosaccharyltransferase was used for the purification of WaaLHP. Briefly, membrane fractions were solubilized with 2% elugent (Calbiochem) in phosphate buffer, pH 7.2. Elugent concentration was diluted to 1% and the membrane fraction loaded unto a nickel agarose column (Qiagen) with 20 mM imidazole. The washing solution contained 50 mM imidazole and 0.5% DDM (Anatrace). Ligase was eluted with 250 mM imidazole in the presence of 0.5% DDM. The lipid A-core from waaLHP mutant cells was obtained as described above and utilized as acceptor in the in vitro assay. UndPP-linked glycans serving as substrates were produced by E. coli CLM24 cells transformed with pACYCpglBmut [22]. A crude UndPP-glycan extraction was performed according to Ielpi et al. [47]. Purified WaaLHP (4–5 µg), purified LPS (1.2 µg, estimated using the method described by Osborn [48]), and an extract containing the UndPP-glycan (20% v/v) were incubated overnight at 37°. The volume was adjusted to 50 µl with reaction buffer as previously described for in vitro glycosylation [24] (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM sucrose and 1 mM MnCl2), with or without ATP (2 mM). Reaction products were visualized by silver staining or Western blotting using the glycan specific antibody HR6. In addition, mild acid hydrolysis was performed similar to the method described by Ielpi et al. [47], by incubation in 1% acetic acid at 80°C for 30 min to destroy the pyrophosphate linkage of the substrate.

Motility assay

H. pylori wild type and O antigen mutant cells from overnight cultures, grown either on plates or in liquid media, were spotted on soft brucella broth agar plates (0.3% agar) and incubated at 37°C under micro-aerobic conditions. Swimming motility was analyzed after 3–6 days by comparison of the colony growth diameters.

CagA translocation assay

The procedure for the CagA translocation assay was previously described by Cendron et al. [49]. Briefly, AGS cells were grown overnight in 10 cm culture dish plates and later infected with H. pylori cells with a multiplicity of infection of 100∶1 for four hours. After incubation, AGS cells were washed, harvested and fractionated. Membrane fractions were analyzed by Western blotting, using anti-CagA (1∶2000, kindly provided by Antonello Covacci), and anti-phosphotyrosine (1∶2000, anti-PY99, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies. Analysis with an anti-h-Met antibody (1∶1000, C-28, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) showing the general host membrane protein h-Met served as loading control.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. RaetzCR

WhitfieldC

2002 Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem 71 635 700

2. LoganRP

1994 Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Lancet 344 1078 1079

3. Simoons-SmitIM

AppelmelkBJ

VerboomT

NegriniR

PennerJL

1996 Typing of Helicobacter pylori with monoclonal antibodies against Lewis antigens in lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Microbiol 34 2196 2200

4. MoranAP

2008 Relevance of fucosylation and Lewis antigen expression in the bacterial gastroduodenal pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Carbohydr Res 343 1952 1965

5. BergmanMP

EngeringA

SmitsHH

van VlietSJ

van BodegravenAA

2004 Helicobacter pylori modulates the T helper cell 1/T helper cell 2 balance through phase-variable interaction between lipopolysaccharide and DC-SIGN. J Exp Med 200 979 990

6. NilssonC

SkoglundA

MoranAP

AnnukH

EngstrandL

2006 An enzymatic ruler modulates Lewis antigen glycosylation of Helicobacter pylori LPS during persistent infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 2863 2868

7. AppelmelkBJ

MartinSL

MonteiroMA

ClaytonCA

McColmAA

1999 Phase variation in Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide due to changes in the lengths of poly(C) tracts in alpha3-fucosyltransferase genes. Infect Immun 67 5361 5366

8. SkoglundA

BackhedHK

NilssonC

BjorkholmB

NormarkS

2009 A changing gastric environment leads to adaptation of lipopolysaccharide variants in Helicobacter pylori populations during colonization. PLoS ONE 4 e5885 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005885

9. BergmanM

Del PreteG

van KooykY

AppelmelkB

2006 Helicobacter pylori phase variation, immune modulation and gastric autoimmunity. Nat Rev Microbiol 4 151 159

10. RaetzCR

ReynoldsCM

TrentMS

BishopRE

2007 Lipid A modification systems in gram-negative bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem 76 295 329

11. Meier-DieterU

BarrK

StarmanR

HatchL

RickPD

1992 Nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli rfe gene involved in the synthesis of enterobacterial common antigen. Molecular cloning of the rfe-rff gene cluster. J Biol Chem 267 746 753

12. LehrerJ

VigeantKA

TatarLD

ValvanoMA

2007 Functional characterization and membrane topology of Escherichia coli WecA, a sugar-phosphate transferase initiating the biosynthesis of enterobacterial common antigen and O-antigen lipopolysaccharide. J Bacteriol 189 2618 2628

13. CuthbertsonL

PowersJ

WhitfieldC

2005 The C-terminal domain of the nucleotide-binding domain protein Wzt determines substrate specificity in the ATP-binding cassette transporter for the lipopolysaccharide O-antigens in Escherichia coli serotypes O8 and O9a. J Biol Chem 280 30310 30319

14. WhitfieldC

2006 Biosynthesis and assembly of capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Biochem 75 39 68

15. AppelmelkBJ

ShiberuB

TrinksC

TapsiN

ZhengPY

1998 Phase variation in Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun 66 70 76

16. GeisG

SuerbaumS

ForsthoffB

LeyingH

OpferkuchW

1993 Ultrastructure and biochemical studies of the flagellar sheath of Helicobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol 38 371 377

17. SherburneR

TaylorDE

1995 Helicobacter pylori expresses a complex surface carbohydrate, Lewis X. Infect Immun 63 4564 4568

18. KaniukNA

VinogradovE

WhitfieldC

2004 Investigation of the structural requirements in the lipopolysaccharide core acceptor for ligation of O antigens in the genus Salmonella: WaaL “ligase” is not the sole determinant of acceptor specificity. J Biol Chem 279 36470 36480

19. AbeyrathnePD

LamJS

2007 WaaL of Pseudomonas aeruginosa utilizes ATP in in vitro ligation of O antigen onto lipid A-core. Mol Microbiol 65 1345 1359

20. MoranAP

2007 Lipopolysaccharide in bacterial chronic infection: insights from Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide and lipid A. Int J Med Microbiol 297 307 319

21. FeldmanMF

WackerM

HernandezM

HitchenPG

MaroldaCL

2005 Engineering N-linked protein glycosylation with diverse O antigen lipopolysaccharide structures in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 3016 3021

22. WackerM

LintonD

HitchenPG

Nita-LazarM

HaslamSM

2002 N-linked glycosylation in Campylobacter jejuni and its functional transfer into E. coli. Science 298 1790 1793

23. KowarikM

NumaoS

FeldmanMF

SchulzBL

CallewaertN

2006 N-linked glycosylation of folded proteins by the bacterial oligosaccharyltransferase. Science 314 1148 1150

24. FaridmoayerA

FentabilMA

HauratMF

YiW

WoodwardR

2008 Extreme substrate promiscuity of the Neisseria oligosaccharyl transferase involved in protein O-glycosylation. J Biol Chem 283 34596 34604

25. AlaimoC

CatreinI

MorfL

MaroldaCL

CallewaertN

2006 Two distinct but interchangeable mechanisms for flipping of lipid-linked oligosaccharides. Embo J 25 967 976

26. ReevesPR

HobbsM

ValvanoMA

SkurnikM

WhitfieldC

1996 Bacterial polysaccharide synthesis and gene nomenclature. Trends Microbiol 4 495 503

27. HofreuterD

OdenbreitS

HaasR

2001 Natural transformation competence in Helicobacter pylori is mediated by the basic components of a type IV secretion system. Mol Microbiol 41 379 391

28. BackertS

SelbachM

2008 Role of type IV secretion in Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol 10 1573 1581

29. SuerbaumS

JosenhansC

2007 Helicobacter pylori evolution and phenotypic diversification in a changing host. Nat Rev Microbiol 5 441 452

30. JuhasM

van der MeerJR

GaillardM

HardingRM

HoodDW

2009 Genomic islands: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and evolution. FEMS Microbiol Rev 33 376 393

31. SzymanskiCM

WrenBW

2005 Protein glycosylation in bacterial mucosal pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol 3 225 237

32. MarsdenGL

LiJ

EverestPH

LawsonAJ

KetleyJM

2009 Creation of a large deletion mutant of Campylobacter jejuni reveals that the lipooligosaccharide gene cluster is not required for viability. J Bacteriol 191 2392 2399

33. JeonB

MuraokaW

ScuphamA

ZhangQ

2009 Roles of lipooligosaccharide and capsular polysaccharide in antimicrobial resistance and natural transformation of Campylobacter jejuni. J Antimicrob Chemother 63 462 468

34. DykxhoornDM

St PierreR

LinnT

1996 A set of compatible tac promoter expression vectors. Gene 177 133 136

35. WangY

TaylorDE

1990 Chloramphenicol resistance in Campylobacter coli: nucleotide sequence, expression, and cloning vector construction. Gene 94 23 28

36. CouturierMR

TascaE

MontecuccoC

SteinM

2006 Interaction with CagF is required for translocation of CagA into the host via the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system. Infect Immun 74 273 281

37. AlmRA

LingLS

MoirDT

KingBL

BrownED

1999 Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 397 176 180

38. CovacciA

CensiniS

BugnoliM

PetraccaR

BurroniD

1993 Molecular characterization of the 128-kDa immunodominant antigen of Helicobacter pylori associated with cytotoxicity and duodenal ulcer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90 5791 5795

39. StrahleU

BladerP

AdamJ

InghamPW

1994 A simple and efficient procedure for non-isotopic in situ hybridization to sectioned material. Trends Genet 10 75 76

40. CouturierMR

SteinM

2008 Helicobacter pylori produces unique filaments upon host contact in vitro. Can J Microbiol 54 537 548

41. MaroldaCL

LahiryP

VinesE

SaldiasS

ValvanoMA

2006 Micromethods for the characterization of lipid A-core and O-antigen lipopolysaccharide. Methods Mol Biol 347 237 252

42. TsaiCM

FraschCE

1982 A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem 119 115 119

43. FeldmanMF

MaroldaCL

MonteiroMA

PerryMB

ParodiAJ

1999 The activity of a putative polyisoprenol-linked sugar translocase (Wzx) involved in Escherichia coli O antigen assembly is independent of the chemical structure of the O repeat. J Biol Chem 274 35129 35138

44. LintonD

DorrellN

HitchenPG

AmberS

KarlyshevAV

2005 Functional analysis of the Campylobacter jejuni N-linked protein glycosylation pathway. Mol Microbiol 55 1695 1703

45. MaroldaCL

VicarioliJ

ValvanoMA

2004 Wzx proteins involved in biosynthesis of O antigen function in association with the first sugar of the O-specific lipopolysaccharide subunit. Microbiology 150 4095 4105

46. ShevchenkoA

WilmM

VormO

MannM

1996 Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal Chem 68 850 858

47. IelpiL

CousoR

DankertM

1981 Lipid-linked intermediates in the biosynthesis of xanthan gum. FEBS Lett 130 253 256

48. OsbornMJ

1963 Studies on the Gram-Negative Cell Wall. I. Evidence for the role of 2-keto - 3-deoxyoctonate in the lipopolysaccharide of Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 50 499 506

49. CendronL

CouturierM

AngeliniA

BarisonN

SteinM

2009 The Helicobacter pylori CagD (HP0545, Cag24) protein is essential for CagA translocation and maximal induction of interleukin-8 secretion. J Mol Biol 386 204 217

Štítky

Hygiena a epidemiológia Infekčné lekárstvo Laboratórium

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Pathogens

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2010 Číslo 3- Parazitičtí červi v terapii Crohnovy choroby a dalších zánětlivých autoimunitních onemocnění

- Očkování proti virové hemoragické horečce Ebola experimentální vakcínou rVSVDG-ZEBOV-GP

- Koronavirus hýbe světem: Víte jak se chránit a jak postupovat v případě podezření?

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- All Mold Is Not Alike: The Importance of Intraspecific Diversity in Necrotrophic Plant Pathogens

- Tsetse EP Protein Protects the Fly Midgut from Trypanosome Establishment

- Perforin and IL-2 Upregulation Define Qualitative Differences among Highly Functional Virus-Specific Human CD8 T Cells

- N-Acetylglucosamine Induces White to Opaque Switching, a Mating Prerequisite in

- Origin and Evolution of Sulfadoxine Resistant

- Rapid Evolution of Pandemic Noroviruses of the GII.4 Lineage

- Natural Strain Variation and Antibody Neutralization of Dengue Serotype 3 Viruses

- Fine-Tuning Translation Kinetics Selection as the Driving Force of Codon Usage Bias in the Hepatitis A Virus Capsid

- Structural Basis of Cell Wall Cleavage by a Staphylococcal Autolysin

- Direct Visualization by Cryo-EM of the Mycobacterial Capsular Layer: A Labile Structure Containing ESX-1-Secreted Proteins

- Lipopolysaccharide Is Synthesized via a Novel Pathway with an Evolutionary Connection to Protein -Glycosylation

- MicroRNA Antagonism of the Picornaviral Life Cycle: Alternative Mechanisms of Interference

- Limited Trafficking of a Neurotropic Virus Through Inefficient Retrograde Axonal Transport and the Type I Interferon Response

- Direct Restriction of Virus Release and Incorporation of the Interferon-Induced Protein BST-2 into HIV-1 Particles

- RNAIII Binds to Two Distant Regions of mRNA to Arrest Translation and Promote mRNA Degradation

- Direct TLR2 Signaling Is Critical for NK Cell Activation and Function in Response to Vaccinia Viral Infection

- The Essentials of Protein Import in the Degenerate Mitochondrion of

- Dynamic Imaging of Experimental Induced Hepatic Granulomas Detects Kupffer Cell-Restricted Antigen Presentation to Antigen-Specific CD8 T Cells

- An Accessory to the ‘Trinity’: SR-As Are Essential Pathogen Sensors of Extracellular dsRNA, Mediating Entry and Leading to Subsequent Type I IFN Responses

- Innate Killing of by Macrophages of the Splenic Marginal Zone Requires IRF-7

- Exoerythrocytic Parasites Secrete a Cysteine Protease Inhibitor Involved in Sporozoite Invasion and Capable of Blocking Cell Death of Host Hepatocytes

- Inhibition of Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Ameliorates Ocular -Induced Keratitis

- Membrane Damage Elicits an Immunomodulatory Program in

- Fatal Transmissible Amyloid Encephalopathy: A New Type of Prion Disease Associated with Lack of Prion Protein Membrane Anchoring

- Nucleophosmin Phosphorylation by v-Cyclin-CDK6 Controls KSHV Latency

- A Combination of Independent Transcriptional Regulators Shapes Bacterial Virulence Gene Expression during Infection

- Inhibition of Host Vacuolar H-ATPase Activity by a Effector

- Human Cytomegalovirus Protein pUL117 Targets the Mini-Chromosome Maintenance Complex and Suppresses Cellular DNA Synthesis

- Dispersion as an Important Step in the Biofilm Developmental Cycle

- Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus ORF57 Protein Binds and Protects a Nuclear Noncoding RNA from Cellular RNA Decay Pathways

- Differential Regulation of Effector- and Central-Memory Responses to Infection by IL-12 Revealed by Tracking of Tgd057-Specific CD8+ T Cells

- The Human Polyoma JC Virus Agnoprotein Acts as a Viroporin

- Expansion, Maintenance, and Memory in NK and T Cells during Viral Infections: Responding to Pressures for Defense and Regulation

- T Cell-Dependence of Lassa Fever Pathogenesis

- HIV and Mature Dendritic Cells: Trojan Exosomes Riding the Trojan Horse?

- Endocytosis of the Anthrax Toxin Is Mediated by Clathrin, Actin and Unconventional Adaptors

- A Capsid-Encoded PPxY-Motif Facilitates Adenovirus Entry

- Homeostatic Interplay between Bacterial Cell-Cell Signaling and Iron in Virulence

- Serological Profiling of a Protein Microarray Reveals Permanent Host-Pathogen Interplay and Stage-Specific Responses during Candidemia

- YfiBNR Mediates Cyclic di-GMP Dependent Small Colony Variant Formation and Persistence in

- PLOS Pathogens

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus ORF57 Protein Binds and Protects a Nuclear Noncoding RNA from Cellular RNA Decay Pathways

- Endocytosis of the Anthrax Toxin Is Mediated by Clathrin, Actin and Unconventional Adaptors

- Perforin and IL-2 Upregulation Define Qualitative Differences among Highly Functional Virus-Specific Human CD8 T Cells

- Inhibition of Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Ameliorates Ocular -Induced Keratitis

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy