-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

The Two Cis-Acting Sites, and , Contribute to the Longitudinal Organisation of Chromosome I

The segregation of bacterial chromosomes follows a precise choreography of spatial organisation. It is initiated by the bipolar migration of the sister copies of the replication origin (ori). Most bacterial chromosomes contain a partition system (Par) with parS sites in close proximity to ori that contribute to the active mobilisation of the ori region towards the old pole. This is thought to result in a longitudinal chromosomal arrangement within the cell. In this study, we followed the duplication frequency and the cellular position of 19 Vibrio cholerae genome loci as a function of cell length. The genome of V. cholerae is divided between two chromosomes, chromosome I and II, which both contain a Par system. The ori region of chromosome I (oriI) is tethered to the old pole, whereas the ori region of chromosome II is found at midcell. Nevertheless, we found that both chromosomes adopted a longitudinal organisation. Chromosome I extended over the entire cell while chromosome II extended over the younger cell half. We further demonstrate that displacing parS sites away from the oriI region rotates the bulk of chromosome I. The only exception was the region where replication terminates, which still localised to the septum. However, the longitudinal arrangement of chromosome I persisted in Par mutants and, as was reported earlier, the ori region still localised towards the old pole. Finally, we show that the Par-independent longitudinal organisation and oriI polarity were perturbed by the introduction of a second origin. Taken together, these results suggest that the Par system is the major contributor to the longitudinal organisation of chromosome I but that the replication program also influences the arrangement of bacterial chromosomes.

Published in the journal: The Two Cis-Acting Sites, and , Contribute to the Longitudinal Organisation of Chromosome I. PLoS Genet 10(7): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004448

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004448Summary

The segregation of bacterial chromosomes follows a precise choreography of spatial organisation. It is initiated by the bipolar migration of the sister copies of the replication origin (ori). Most bacterial chromosomes contain a partition system (Par) with parS sites in close proximity to ori that contribute to the active mobilisation of the ori region towards the old pole. This is thought to result in a longitudinal chromosomal arrangement within the cell. In this study, we followed the duplication frequency and the cellular position of 19 Vibrio cholerae genome loci as a function of cell length. The genome of V. cholerae is divided between two chromosomes, chromosome I and II, which both contain a Par system. The ori region of chromosome I (oriI) is tethered to the old pole, whereas the ori region of chromosome II is found at midcell. Nevertheless, we found that both chromosomes adopted a longitudinal organisation. Chromosome I extended over the entire cell while chromosome II extended over the younger cell half. We further demonstrate that displacing parS sites away from the oriI region rotates the bulk of chromosome I. The only exception was the region where replication terminates, which still localised to the septum. However, the longitudinal arrangement of chromosome I persisted in Par mutants and, as was reported earlier, the ori region still localised towards the old pole. Finally, we show that the Par-independent longitudinal organisation and oriI polarity were perturbed by the introduction of a second origin. Taken together, these results suggest that the Par system is the major contributor to the longitudinal organisation of chromosome I but that the replication program also influences the arrangement of bacterial chromosomes.

Author summary

Proper chromosome organisation within the cell is crucial for cellular proliferation. However, the mechanisms driving bacterial chromosome segregation are still strongly debated, partly due to their redundancy. Two patterns of chromosomal organisation can be distinguished in bacteria: a transversal chromosomal arrangement, such as in E. coli, where the origin of replication (ori) is positioned at midcell and flanked by the two halves of the chromosome (replichores), and a longitudinal arrangement, such as in C. crescentus, where ori is recruited to the pole and the replichores extend side by side along the long axis of the cell. Here, we present the first detailed characterization of the arrangement of the genetic material in a multipartite genome bacterium. To this end, we visualised the position of 19 loci scattered along the two V. cholerae chromosomes. We demonstrate that the two chromosomes, which both harbour a Par system, are longitudinally organised. However, the smaller one only extended over the younger cell half. In addition, we found that disruption of the Par system of chromosome I released its origin from the pole but preserved its longitudinal arrangement. Finally, we show that the addition of an ectopic ori perturbed this arrangement, suggesting that the replication program contributes to chromosomal organisation.

Introduction

Bacterial chromosome replication is initiated from a unique origin (oriC) and progresses bidirectionally. The replication of circular chromosomes terminates opposite the oriC in a region termed the terminus (Ter). Within the Ter region is a site-specific recombination site, termed dif, dedicated to the resolution of chromosome dimers [1]. These factors define two replication arms, Left and Right, mirrored by the <oriC-dif> axis. Detailed investigations of the choreography of chromosomal movements during the cell cycle of several monochromosomic bacteria suggest that segregation is concurrent with replication and starts with the precise positioning of newly replicated sister copies of the oriC region into opposite cell halves [2], [3], [4], [5]. Segregation of other sister chromosomal loci to their positions in daughter cells follows shortly after their replication with sister copies of Ter being segregated last [2], [3], [4], [5]. Less is known about the choreography of chromosome segregation in bacteria with multipartite genomes. However, the analysis of a single locus in the oriC region and a single locus in the putative Ter region of the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes suggests a model of replication and segregation that is consistent with monochromosomic bacteria [6], [7], [8]. Taken together, these observations suggest that the active positioning of the oriC region sets the pace for chromosome segregation, raising questions regarding the underlying mechanism.

Similar to most other bacteria, a specific partition system is encoded on each of the Vibrio cholerae chromosomes [9]. Bacterial chromosome partition machineries are related to the Type I partitioning systems of plasmids. They consist of two genes, parA, which codes for an ATPase, and parB, which codes for a sequence-specific DNA binding protein that is able to spread around its binding site, parS [10]. Several parS sites are usually found proximal to and in some cases encompassing the oriC region of bacterial chromosomes [9]. The role of Par systems in DNA segregation is well established for low-copy number plasmids [11], [12], [13]. However, their role in bacterial chromosome segregation remains controversial, notably because the disruption of Par systems in different bacterial species produces different phenotypes. The Par systems of Caulobacter crescentus, Myxococcus xanthus and V. cholerae chromosome II are essential for chromosome segregation [4], [14], [15]. The impairment of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Par system caused the formation of ∼20% anucleate cells [16]. However, the disruption of the Par machinery affects few cells (<2%) in Bacillus subtilis [17] and yields no segregation defect for V. cholerae chromosome I [18]. Moreover, several bacterial species, notably Escherichia coli and Streptococcus pneumonia, lack a functional Par system. Partition systems have also been implicated in other cellular processes including replication initiation [19], [20], cell cycle coordination [4], [14] and chromosome compaction [21], [22], [23]. Finally, ParB-binding to oriC-proximal parS sites recruits SMC proteins to the origin region in B. subtilis and S. pneumoniae, contributing to chromosome segregation even in the absence of ParA [21], [22], [23]. Nevertheless, Par systems are directly involved in the polar positioning and the active bipolar migration of the oriC region of the C. crescentus chromosome and V. cholerae chromosome I [8], [24], [25], [26], [27]. The polar anchoring mechanisms have been described for these two systems [27], [28].

The characterization of chromosomal organisation in different bacterial species suggests a common mechanism of longitudinal organisation in which the oriC region is positioned towards the old pole, Ter is positioned towards the new pole, and the two chromosome replichores extend over the long axis of the cell [3], [4], [29], [30]. The polar localisation of the oriC regions of V. cholerae chromosome I and of the multiple chromosomes of S. meliloti and A. tumefaciens suggests a similar longitudinal organisation [31], [32]. In contrast, the E. coli chromosome, which seems devoid of a Par system, adopts a transversal organisation where the oriC region is positioned at midcell and the left and right chromosomal arms extended toward the opposite cell halves [33], [34]. Taken together, these observations suggest that it is the active positioning of the oriC region towards the old cell pole by Par systems that is responsible for the longitudinal chromosomal organisation observed in most bacterial species.

However, two characteristics of V. cholerae make it an ideal bacterial model to test this hypothesis. Firstly, the Par system of V. cholerae chromosome II positions the origin region (oriC2) at midcell rather than at the cell pole, which would be expected to drive a transversal arrangement if the hypothesis was correct. Secondly, disruption of the Par system of V. cholerae chromosome I does not affect any step of the cell cycle, allowing for the direct investigation of its contribution to chromosomal organisation. In this current study, the analysis of the intracellular location of 12 chromosome I loci and 7 chromosome II loci in exponentially growing cells indicated that both V. cholerae chromosomes adopted a longitudinal organisation. Chromosome I extends from the old pole to the new pole and chromosome II extends from midcell to the new pole, i.e. in the younger cell half. By displacing parS1 sites away from oriC the Par system was shown to contribute to the longitudinal organisation of chromosome I. However, the parS1-deleted chromosome I remained longitudinal, with the oriC locus remaining located close to the old pole. The insertion of an ectopic origin of replication was sufficient to disrupt the longitudinal organisation of parS1 deleted chromosome I. Interestingly, the ectopic origin of replication was often positioned closer to the old pole than the original oriCI. Taken together, these observations suggest that the replication program contributes to the longitudinal organisation of V. cholerae chromosome I.

Results

Fluorescent labelling systems and analysis of chromosome choreographies

Chromosome choreography involves successive steps of chromosome organisation as a function of cell cycle progression. To avoid any complications linked to multiple concurrent rounds of replication, cells were cultivated at 37°C in slow growing conditions (M9 Fructose supplemented with thiamine) characterised by a 55 min generation time divided into three successive periods: a period of 11 min before replication initiation (B period), a 32 min-long replication period (C period) and a 12 min period after replication and before division (D period) [35]. Snapshot images of cells in steady state exponential growth were acquired. By correlating the length of cells with their progression through the cell cycle we studied chromosomal organisation as a function of cell elongation. Cells were classified according to their length in 0.1 µm intervals. A sliding window of 0.3 µm was used to determine the median position and frequency of duplication of any specific chromosomal locus. In our growth conditions the majority of cells had a length between 1.9 µm and 4.3 µm. We will refer to the cells of the first point plotted, corresponding to the 2 µm interval, as newborn cells and the cells of the last interval plotted, corresponding to the 4.2 µm interval, as dividing cells.

The spatial organisation of chromosome I and of chromosome II was deduced from the positioning of 12 and 7 loci respectively. They were broadly distributed over the entire genome, particularly the regions of special interest, such as the origin of replication and the chromosomal dimer resolution site of each of the two chromosomes (oriI, oriII, terI and terII). Five loci were tagged on the right (R1I to R5I) and left (L1I to L5I) replichores of chromosome I. On chromosome II, three loci were tagged on the right replichore (R1II to R3II) and two on the left (L1II and L2II). The loci were visualised in pairwise combinations using two compatible fluorescent labelling systems, a lacO array was inserted at one of the loci and a parSpMT1 site at the other locus. LacI-mCherry and yGFP-Δ30ParBpMT1 [34] protein fusions were produced from an operon in place of the V. cholerae lacZ gene. In some cases, a third locus was tagged with a tetO array and visualized by the production of a TetR-Cerulean fusion from a plasmid. We observed the same pattern of localisation of the L3I or terI loci during the cell cycle whether they were tagged with a lacO or tetO array or with a parSpMT1 site, suggesting that these three systems did not affect the positioning of the chromosomal loci under our experimental conditions.

Dual labelling has three advantages. Firstly, the precise orientation of the long axis of the cell from the new pole to the old pole could be determined. The new pole is defined as the pole resulting from the previous cell division event. Assuming no gross rearrangements of chromosomal DNA after cell division, a locus closer to the septum than to the poles in dividing cells was defined as being closer to the new pole than to the old pole in newborn cells. Time-lapse microscopy observations validated this method (Figure S1). Secondly, dual labelling allowed for the collection of data in two different strains even if they presented slightly different cell size distributions (Figure S2). The cell size distribution of the two strains was re-aligned using the frequency of duplication of a common locus as a reference. In the rest of the manuscript we will refer primarily to compiled figures. However, each of our conclusions could be drawn based on individual strain data. The data of each individual strain are presented in Figures S3 to S39. Thirdly, dual labelling allowed for the comparison of the timing of duplication of the two tagged loci of each strain as a function of cell elongation and the direct measure of the distance separating these loci as a function of cell elongation. These comparisons could be made independently of any orientation procedure or cell size re-alignment.

Sequential order of duplication of chromosomal DNA in V. cholerae

The tagged loci were always observed as a single focus in newborn cells (Figure 1B and 2B). This is consistent with our growth conditions in which newborn cells contain a unique non-replicating copy of each of the two chromosomes. In dividing cells, two separate foci were observed for most of the analysed loci (Figures 1B and 2B). The only exceptions were L5I, R5I and terI, whose foci were duplicated in about 50%, 40% and 10% of the dividing cells, respectively (Figure 1B). This is consistent with a previous report where sister copies of a locus situated at 40 kbp from dif1 remained colocalised until the very end of septation [6].

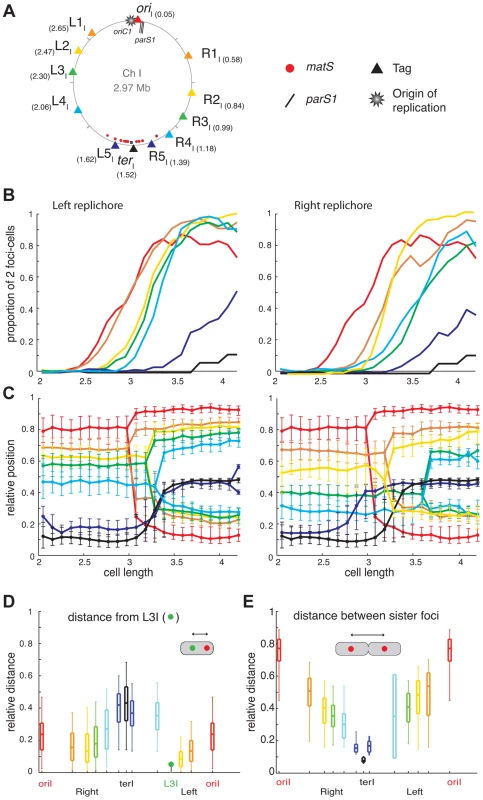

Fig. 1. Longitudinal organisation of V. cholerae chromosome I: Sequential duplication and segregation.

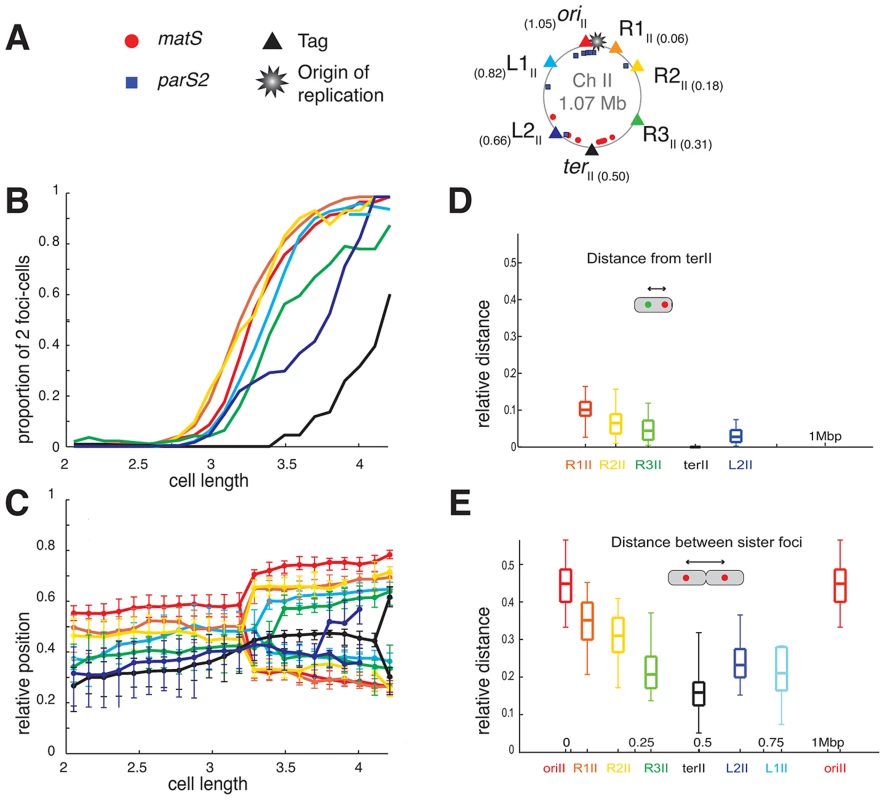

(A) Circular V. cholerae chromosome I and II maps indicating the position of the different tags with respect to oriC1, parS1 and matS sites and their corresponding colour code. (B) Proportion of 2 foci cells according to the realigned cell length (cell size intervals of 0.1 µm) for the different loci of the chromosome I. For each locus, a minimum number of 800 cells were analysed. Left panel: left replichore; Right panel: right replichore. The first cell size interval where ≥50% of cells contained two L3I foci served to align the cell length distributions of ADV20, ADV21, ADV22, ADV23, ADV25, ADV33, ADV42, ADV50 and ADV51 strains, using ADV24 L3I as reference. The strain EPV213 was aligned against ADV42 using the timing of recruitment of terI to midcell. (C) Reconstitution of the segregation choreographies of the 12 chromosome I loci. Left panel: left replichore; Right panel: right replichore. The median, the 25th and the 75th percentiles of the relative cell position of each locus are plotted for each cell size interval. The cells falling into the first interval were named newborn cells and the ones falling into the last interval were named dividing cells. 0: new pole; 1: old pole. (D) The relative distance between different chromosome I loci to the L3I locus was measured as a function of the relative cell length in the cells containing only one focus of each locus. The median (horizontal bar), the 25th and the 75th percentiles (open box) and the 5th and the 95th percentiles (error bars) of the distance of a given locus to L3I were indicated at this locus position along a chromosome I linear genetic map. (E) Relative distance between any of the chromosome sister loci, measured in cells with a length >3.4 µm. Fig. 2. Longitudinal organisation of V. cholerae chromosome II: Sequential duplication and segregation.

(A) Circular V. cholerae chromosome II map indicating the position of the different tags with respect to oriC2, parS2 and matS sites and their corresponding colour code. (B) Proportion of 2 foci cells according to the realigned cell length (cell size intervals of 0.1 µm) for the different loci of chromosome II. For each locus, a minimum number of 800 cells were analysed. The first cell size interval where ≥50% of cells contained duplicated L3I was used to realigned ADV26 to the ADV24 reference strain. CP708, ADV131, ADV30 and ADV131 cell size distributions were aligned with the GDV552 cell sizes based on the cell size interval where ≥25% of cells contained two terII loci. GDV552 was aligned to ADV42 using the cell size interval where terI is recruited to midcell. ADV123 was aligned with ADV24 using the first cell size interval where ≥50% of cells contained two oriI. (C) Reconstitution of the segregation choreographies of the 7 chromosome II loci, as in Figure 1C. (D) Relative distance between any of the chromosome II loci to the terII locus, measured in the cells containing only one focus of each locus. (E) Relative distance between any of the chromosome sister loci, as in Figure 1E. The order of duplication of sister copies of each locus as a function of cell elongation followed the genetic map from ori to ter along the two arms of chromosome I and of chromosome II (Figures 1B and 2B). In addition, with the exception of the dif1 proximal loci, the rate of focus duplication of any given locus was similar. The proportion of cells with two foci increased abruptly from 10% to above 80% within ≤0.6 µm of cell elongation. However, the difference in the timing of duplication of two consecutive loci was not strictly proportional to the genetic distance that separated them. For instance, sister L1I separation immediately followed sister oriI separation and occurred much earlier than sister L2I separation, despite L1I being closer to L2I than to oriI. This observation is consistent with a previous finding in E. coli suggesting that the time sister loci remain together after replication is variable [36]. In addition, it was sometimes not possible with the resolution of our experiments to differentiate the timing of duplication of loci that were too close on the genetic map, such as oriII, R1II and R2II or R3I and R4I.

Finally, using a strain with tagged oriII and L3I, it was observed that the separation of sister L3I occurred at smaller cell length than for sister oriII (Figure S9, ADV26). These results suggest that the separation of sister copies of the loci most proximal to the origin of replication on chromosome II occurred later than sister oriI separation (Figures 1B and 2B). This observation is in agreement with the delayed firing of the origin of replication of chromosome II compared to chromosome I replication [35].

Longitudinal organisation of Chromosome I and II

For most loci and cell length categories, we observed cells with either two separated foci or a single focus. The proportion between these two types of cells varied as a function of cell elongation (Figures 1B and 2B). To simplify the representation of the data, we plotted the position of the foci that correspond to the dominant cell type in each cell length interval (Figures 1C and 2C). In addition, we plotted the median positions of the observed foci (filled circles), along with the 25th–75th percentiles (error bars).

In newborn cells, the relative cell position of oriI and terI was approximately 0.8 and 0.1 respectively, reflecting that oriI is positioned near the old pole and terI close to the new pole. In agreement with previous reports the position of oriI in the overall cell population, i.e. irrespective of cell length, was closer to 0.9 [8], [20]. The distance between the position of oriI and the position of any locus on chromosome I correlated with the genetic distance, suggesting a longitudinal arrangement of the replichores within the cell (Figure 1C). To confirm this longitudinal arrangement we directly calculated the distance between L3I, which is located approximately in the middle of the left replichore, to additional chromosome I loci in cells that displayed a single focus for each of these two loci (Figure 1D). Consistent with a longitudinal arrangement L3I was observed as being closer to the right replichore loci than to oriI and terI (Figure 1D). Furthermore, we directly calculated the distance between separated sister loci in individual cells (Figure 1E). The distance between sister copies of each locus linearly decreased from oriI to terI, further confirming the longitudinal organisation of chromosome I (Figure 1E).

Two modes of segregation could be distinguished among chromosome I loci. The first mode of segregation was observed for loci located from oriI to L4I or R4I. In this mode, loci remained close to the position they occupied at cell birth until their duplication. As duplication occurred the greater the genetic distance between a locus and oriI, the longer it remained static at its home position. After duplication sister foci segregated to their new home positions in the next cell length interval, suggesting that segregation might be a transient event within the cell cycle. The distances travelled by two sister foci were not identical. The most unbalanced situation was observed for oriI where one copy remained nearly immobile whilst the second copy crossed the whole cell length. In contrast, the two L3I sister loci exhibited a symmetrical separation on either side of the midcell/future new pole. The second mode of segregation was characterized by the mobilization of the loci towards midcell before duplication. This mode of segregation applied to loci located in the terminus region of chromosome I, i.e. R5I, L5I and terI. These loci migrated towards midcell (within 4 intervals) earlier than the duplication of loci located several hundreds of kb upstream (Figure 1B).

The oriII of chromosome II positioned near midcell (with a relative position of 0.55) and dif2 near to the new pole (with a relative position of 0.28) in newborn cells. This is consistent with previous reports [6], [8]. The positioning and mobilisation of the oriII region depends on a partition system like oriI [15]. The positions of R1II, R2II, R3II and L1II, L2II were intermediate between those of oriII and terII, suggesting that chromosome II occupied only the younger half of the cell. Despite the short distance separating oriII proximal loci (Figure 2B), the sequential oriII to terII positioning of the seven chromosome II loci was observed, suggesting a longitudinal organisation (Figure 2C). Direct measurement of the distance between terII and R1I, R2I, R3I and L2II (Figure 2D) and of the distance between sister copies of all of the chromosomal loci (Figure 2E) confirmed the longitudinal organisation of chromosome II. Furthermore, the duplication of most loci occurred close to midcell (Figure 2C). This suggests that un-replicated chromosome II loci are pulled towards midcell by replication, which in turn pushes sister copies of replicated loci away from midcell and each other.

Impact of parS1 displacement on chromosome I organisation

We speculated that the displacement of parS1 away from oriCI would modify the longitudinal arrangement of chromosome I. To test this hypothesis, tandem parS1 sites were introduced at 300 kb, 490 kb and 650 kb on the left arm of chromosome I in cells devoid of their three natural parS1 sites. Displacing the location of the Par-mediated anchoring zone on chromosome I did not affect the fitness or the morphology of the cells. The functionality of the displaced parS1 sites was not affected as judged by the visualisation of at least one polar focus of Ypet-ParB1 in the majority of different cell populations (Figure S40).

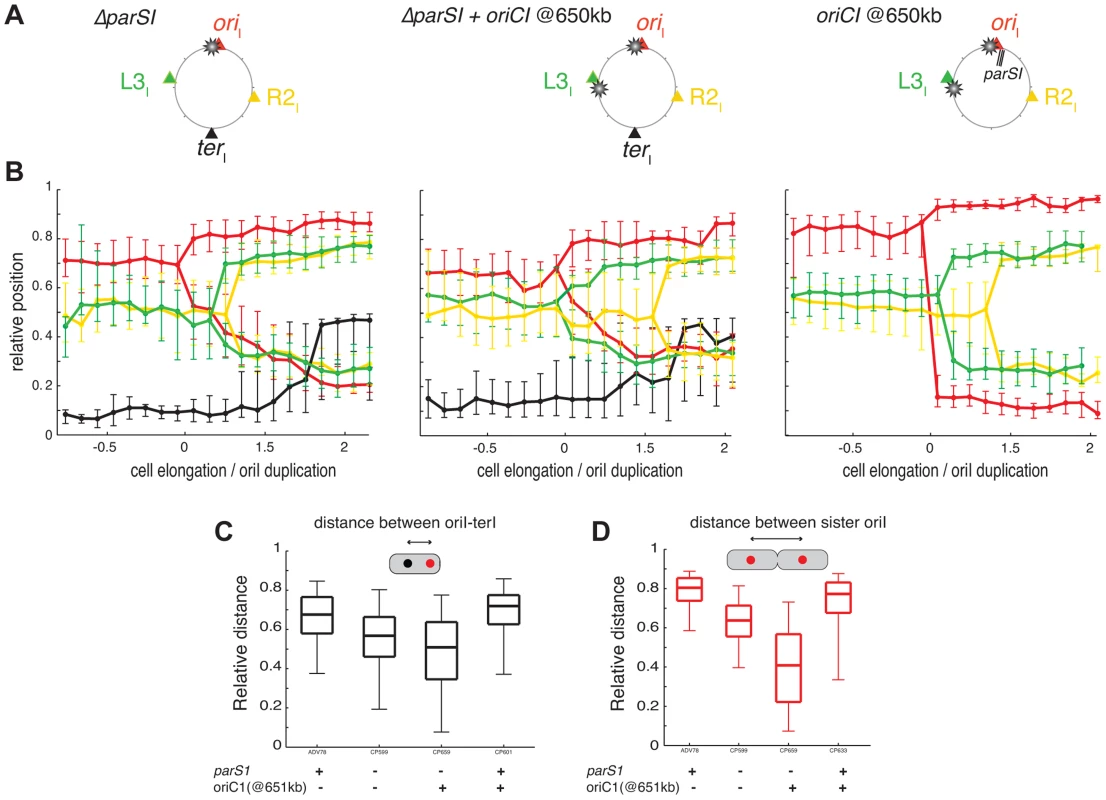

To assess the effect of parS1 displacements on the global organization of chromosome I, the cellular positions of oriI, R2I, L3I and terI were visualized. Displacing parS1 sites on chromosome I had a dramatic effect on the positioning and segregation of oriI, L3I and R2I (Figure 3B). In contrast, the positioning and segregation of terI was not significantly affected (Figure 3B). However, the displacement of parS1 to the L3I location affected the polar positioning of terI prior to its final recruitment to midcell.

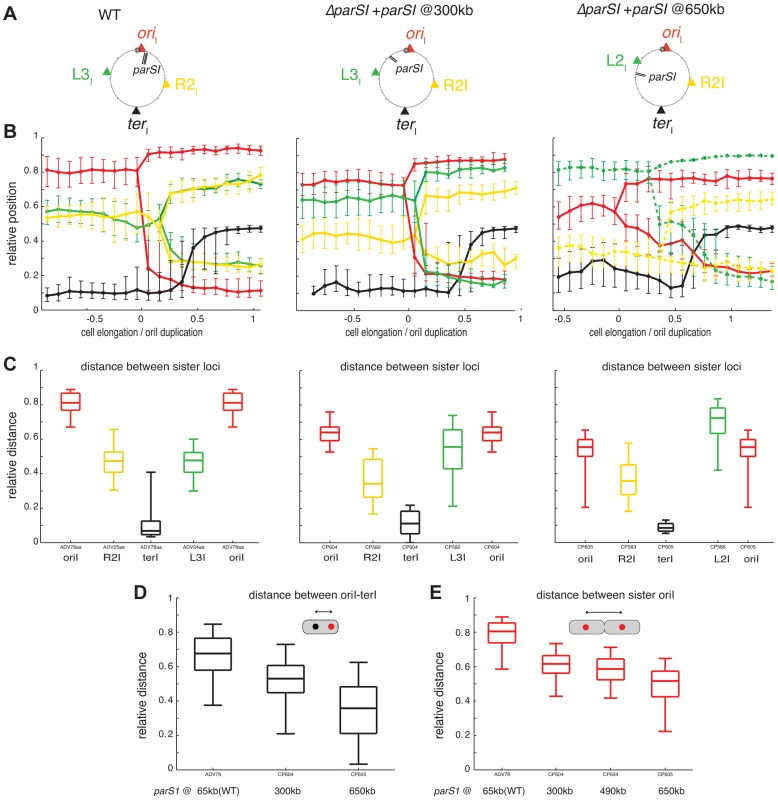

Fig. 3. Reorganisation of chromosome I upon parS1 displacement.

(A) Circular map indicating the position of the different loci analysed in different genetic background (WT, parS1300 kb and parS1650 kb from left to right, respectively) and the colour code of the analysed loci. (B) Reconstitution of the segregation choreographies, as in Figure 1C. 2 µm of cell elongation were shown centred on the cell interval where at least 50% of the cells had duplicated oriI. For the WT choreography, ADV114 and ADV78 cell size distributions were aligned with the ADV24 cell sizes using the first cell size interval where 50% or more of cells contained duplicated oriI. For the parS1300 kb choreography, CP604 and CP582 cell size distributions were aligned with the CP591 cell sizes using the first cell size interval where ≥50% of cells contained 2 foci of oriI and L3I, respectively. For the parS1650 kb choreography, the cell sizes correspond to strain CP605 (oriI and terI). CP583 and CP586 cell size distributions could not be realigned. The corresponding data was plotted with dashed lines (L2I and R2I). (C) Relative distances between any of the sister loci, as in Figure 1E. (D) Relative distance between any loci to terI locus, as in Figure 1D. (E) Relative distance between oriI sister loci, in with displaced parS1 sites, as in Figure 1E. The displacement of parS1 sites to a location equidistant to oriI and L3I, caused the single oriI focus of small cells to shift towards midcell and the oriI sisters to be positioned closer to the quarter positions in long cells (Figure 3B, parS1@300kbp). This was confirmed by a decrease in the distance between oriI and terI before oriI duplication (Figure 3D) and a decrease in the distance between oriI sisters after their separation (Figure 3C and 3E). The single L3I focus of small cells was shifted towards the old pole and L3I sisters were positioned further away from quarter positions in long cells (Figure 3B, parS1@300kbp). This was confirmed by the direct measurement of the distance between L3I sisters after their separation (Figure 3C). In addition, R2I positioning was shifted toward the new pole, as observed by a reduced distance between sister R2I loci (Figure 3C). As a consequence, L3I and R2I no longer co-localised (Figure 3B).

When the parS1 sites were displaced to the L3I locus, the home position of oriI and L2I were switched. The oriI locus, which was now situated 700 kb away from the parS1 sites, adopted the positioning of L3I locus in the wild-type context (Figure 3B, parS1@650kbp). This was confirmed by a decrease in the distance between oriI and terI before oriI duplication (Figure 3D) and a decrease in the distance between oriI sisters after their separation (Figures 3C and 3E). Reciprocally, L2I, which was now located 170 kb from the parS1 sites, exhibited a positioning similar to oriI in the wild-type cell (Figure 3B, parS1@650kbp). The distance between sister L2I also became larger than the oriI sister distance (Figure 3C). Finally, the shift of R2I positioning toward the new pole was exacerbated (Figure 3B and 3C).

To further demonstrate the extent of the chromosomal reorganisations, we took advantage of our double labelling systems to directly monitor the respective positions of oriI and L3I within long cells once they were duplicated and had reached their new home position. We determined the proportion of cells in which oriI was more polar than L3I when the parS1 sites were at their normal position (parS165 kb, wild-type) or had been displaced by 300 kb (parS1300 kb) or 490 kb (parS1490 kb). This method allowed for chromosome rearrangements to be monitored at the single cell level. oriI was more polar than L3I in almost 100% of the cells in the wild type context (Figure 4A, parS165 kb). The proportion of cells in which oriI was more polar than L3I decreased to 60% when parS1 sites were equidistant between oriI and L3I (Figure 4A, parS1300 kb) and down to 30% when parS1 sites were closer to L3I than to oriI (Figure 4A, parS1490 kb). The median distances between separated oriI sisters were very similar when parS1 sites had been displaced to 300 kb or 490 kb (Figure 3E).

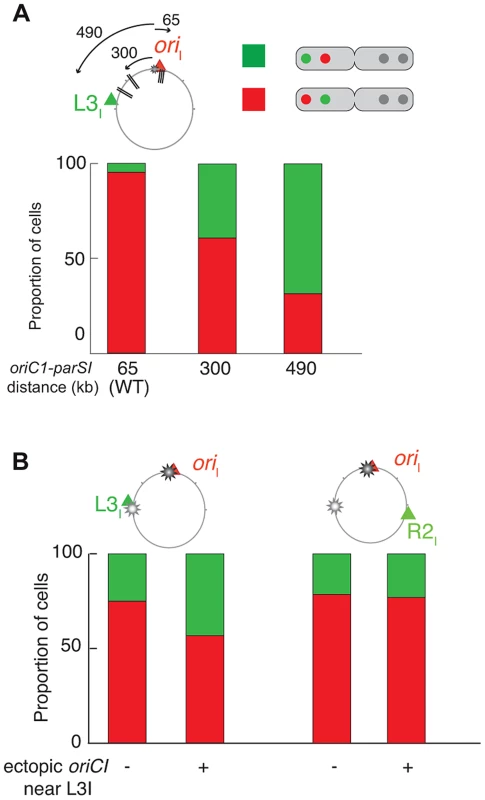

Fig. 4. Increase of L3I polarity over oriI upon parS1 or oriC1 proximity to L3I locus.

For each pole of dividing cells, the most polar locus between oriI and L3I was determined (A) in WT (ADV24), parS1300 kb (CP591) and parS1490 kb (CP634) and (B) in ΔparS1 (CP568), ΔparS1 + oriC1651 kb (CP626), parS165 kb + oriC1651 kb (CP633). This corresponds to approximately 100 cells. The red part of the stacked histogram represents the proportion of case with oriI more polar than L3I, whereas the green part represents the opposite. In conclusion, the displacement of parS1 sites along the left arm of chromosome I led to the global rearrangement of chromosome I within the cell. These results suggest that the Par system of chromosome I not only mobilises and anchors the parS1 sites at the poles but also directly contributes to the arrangement of the entire DNA molecule. Only the positioning of the terminus region escaped the influence of the Par system.

Impact of parS1 deletion on chromosome I organisation

Previous studies indicated that deletion of parA1 resulted in the release of the parS1 sites from the old pole with the relative position of ParB1 changing from 0.023 in a wild-type context to 0.2 [6], [8]. Despite this dramatic change, no effects on cell fitness or cell cycle parameters were reported, suggesting that chromosome I segregation was not affected by the disruption of its Par system. However, we speculated that the organisation and segregation choreography of chromosome I would be globally modified when Par-mediated mobilization and anchoring of oriI were lost. To this end, we followed the localisation of oriI, R2I, L3I and terI loci in ΔparS1 cells. The longitudinal arrangement of chromosome I was maintained during the whole cell cycle. oriI remained the closest loci to the old pole with a relative position of 0.7 in small cells and a relative oriI - terI distance of 0.68 (Figures 5B and 5C). R2I and L3I loci remained co-localised during the whole cell cycle and were positioned around midcell until their duplication (Figure 5B). After duplication, oriI sisters remained more polar than L3I and R2I sisters, which still co-localised (Figure 5B). However, the relative distance between separated oriI sisters was smaller than in wild-type cells (Figure 5D). In addition, the increase in the 25th–75th percentiles (error bars, Figure 5B) and the increase in the variability of the oriI - terI distance (Figure 5C) suggest that the home positions of oriI, L3I and R2I before and after duplication were less stringently controlled. Time-lapse experiments confirmed the global behaviour of these three loci (data not shown). In contrast, the choreography and late duplication of terI was not affected by the absence of the parS1 sites. The positioning of oriII, R2II and terII loci suggest that the chromosome II behaviour was not dramatically modified in ΔparS1 cells (Figure S41). In conclusion, the impairment of the Par system of chromosome I slightly disorganized the positioning and the segregation of the bulk of chromosome I. However, chromosome I remained longitudinally organised and oriI remained more polar than the rest of chromosome I, suggesting the existence of additional chromosome I organizing and positioning mechanisms.

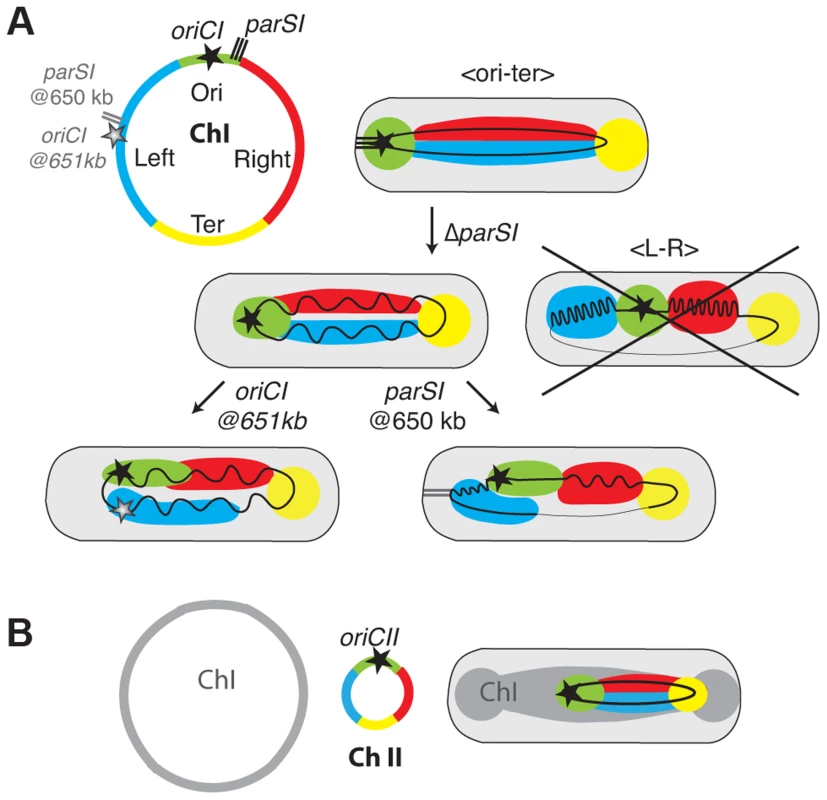

Fig. 5. Disorganisation of chromosome I upon the ectopic oriC1651 kb addition.

(A) Circular maps indicating the position of the different loci analysed in different genetic background from left to right, respectively : ΔparS1, ΔparS1 + oriC1651 kb, parS165 kb + oriC1651 kb. (B) Reconstitution of the segregation choreographies of the loci tagged in the different genetic background, as in Figure 1C. For the ΔparS1 choreography, the CP639 cell size distribution was aligned with the CP655 cell sizes using the cell size interval where ≥50% of cells contained two R2I foci; For the ΔparS1 + oriC1651 kb choreography, the cell sizes of CP626 and CP656 were aligned to the cell sizes of CP659 using the cell size interval where ≥50% of cells contained two oriI foci; For parS165 kb + oriC1651 kb choreography, the cell sizes of ADV115 were realigned to the cell sizes of CP633 using the cell size interval where ≥50% of cells contained two oriI foci. (C) Relative distance between oriI and terI loci, as in Figure 1D. (D) Relative distance between the oriI sister loci, as in Figure 1E. Impact of an extra oriC1 at 651 kb on chromosome I organisation

We hypothesised that the replication program might be, at least in part, responsible for the maintenance of the longitudinal arrangement of chromosome I in the absence of parS1 sites. To test this hypothesis, we introduced an extra origin of replication 651 kb from its normal position on the left replichore of chromosome I in cells lacking parS1 sites. The fitness of cells harbouring the two origins was not affected. Replication profiling demonstrated that the ectopic origin was as efficient as the wild-type origin and that the two origins were used at each cell cycle (Figure S42). Correspondingly, the separation of oriI and L3I sisters became synchronous (Figure S42). The perturbation of the replication program further decreased the polarity of the oriI region in small cells (Figure 5B), which decreased the distance between single oriI and terI foci (Figure 5C). The effect was more evident in long cells (Figure 5B) where the relative distance between separated oriI sisters decreased to half the distance of wild-type cells with a high level of variability (Figure 5D). The segregation of oriI sisters also became asymmetric with one of the two copies remaining relatively polar while the other adopted a more central position (Figure 5D). Finally, the L3I locus became slightly more polar and no longer co-localised with R2I (Figure 5B). In contrast, earlier replication of the terI locus (Figure S42) did not modify its home position (Figure 5C). The position of the R2I locus was not significantly affected by the ectopic origin (Figure 5C). Then, we decided to directly monitor in each cells which of the two competing locus, oriI and L3I, was closer to the old pole. If the polar location of a given locus was only dictated by its proximity to the initiation of replication the proportion of cells in which L3I was closer to the old pole than oriI would reach 50%. Correspondingly, the polarity of oriI compared to L3I decreased from 80% in the parental cells (ΔparS1) to 55% in the cells harbouring an ectopic origin on the Left arm at 651 kb from oriI (Figure 4B). The polar location of oriI compared to R2I was unchanged by the addition of the ectopic origin, suggesting that the phenotype was not linked to a global disorganisation of the DNA within the cell (Figure 4B). Thus, the replication program itself contributes to the polar positioning of loci that are close to the origin of replication. However, this contribution is masked by the presence of a Par system (Figure 5B). The contribution of the replication program may be more evident in cells containing a unique but displaced oriC1 site. However, the presence of an oriC1 site within the origin region is essential for cell viability (Figure S43).

Discussion

In this manuscript the use of fluorescent microscopy to follow the position of 19 loci within the genome of V. cholerae provides the first detailed characterization of the organization and dynamics of a multipartite bacterial genome.

The two V. cholerae chromosomes are longitudinally arranged

After division, the two replichores of chromosome I were arranged side by side from the old pole to the new pole (Figures 1 and 6A, WT). This longitudinal organization, with the origin positioned near the old pole and the terminus near the new pole in newborn cells, was expected for chromosome I due to the similarities in the positioning and dynamics of the origin and terminus regions with C. crescentus [30]. Previous reports suggested that the origin region of V. cholerae chromosome II was positioned at midcell in newborn cells and that, after replication, sister copies of it migrated to ¼ and ¾ positions [8]. This is similar to the positioning and dynamics of the E. coli chromosome, which suggested a transversal mode of organization for chromosome II. However, we demonstrate that the two replichores of chromosome II were arranged side by side with chromosome II only occupying the new half of the younger cells and the two sister chromatids the central part of the older cells (Figures 2 and 6B, WT). Thus, both V. cholerae chromosomes are longitudinally organized within the cell.

Fig. 6. Models of chromosome I and II organisation and reorganisations by parS1 and oriC1 actions.

(A) Chromosome I was divided in 4 regions Ori in green corresponding to the region proximal of the replication origin , Left in blue, Right in Red corresponding to the left and right replichores and Ter in Yellow corresponding to the matS sites containing region (circular map). In the WT context, the Ori and the Ter are confined to the old pole and new pole, respectively. The Left and Right are laying in between. In the ΔparS1 context, the longitudinal organisation is maintained but the Ori is detached from the pole. The loss of parS1 sites do not convert the organisation of chromosome I to a transversal type as in E. coli (crossed drawing). In the parS1650 kb context, the Left becomes more polar than the Ori region. The Right is restricted toward the new pole where the Ter remains positioned. In the oriC1651 kb context, the Left becomes as polar as the Ori but the chromosome is globally less organised. (B) The chromosome II was divided in 4 regions as for chromosome I. In the WT context, the Ori was confined to midcell. The Left and Right are extended from midcell to the new pole. The TerII is not closely tethered to the new pole as terI. Positioning and segregation dynamics of the terminus region

The terminus region of chromosome I behaved differently from the bulk of the chromosome and was recruited to midcell long before the time of sister foci duplication (Figure 1). In addition, terminus sister copies remained together until the very end of the cell cycle (Figure 1). Finally, whereas displacing parS sites led to the rotation of the whole chromosome in C. crescentus [30], the position of the terminus region of chromosome I was not affected by parS1 displacements (Figure 3). These observations are likely due to the presence of a MatP/matS system in V. cholerae that is absent from C. crescentus [37], [38]. Our results also suggest that sister copies of the terminus region of chromosome II separated earlier than sister copies of the terminus region of chromosome I even though both regions harbour matS sites (Figure 2). The differential contribution of the MatP/matS macrodomain organization system to the segregation of the terminus regions of chromosome I and II is the subject of a another study [39].

Longitudinal organisation is not entirely driven by partition systems

As for all other studied bacterial chromosomes with a longitudinal organization the position of the origin of replication region of each of the two V. cholerae chromosomes was driven by a ParABS partition system [40]. We speculate that the longitudinal organization of each chromosome is linked to the action of their partition machineries. Consistent with this, the displacement of parS1 sites rearranged the bulk of chromosome I within the cell with the locus most proximal to the displaced parS1 sites now occupying the polar edge of the chromosome (Figures 3, 4A and 6A, parS1@650kb). This is similar to the impact of parS sites on chromosome organisation in C. crescentus [30]. However, chromosome I remained longitudinally arranged in the absence of parS1 sites suggesting the existence of additional factors involved in chromosomal organisation (Figures 5 and 6A, ΔparS1).

Replication contributes to chromosome segregation in V. cholerae

In C. crescentus sister loci segregate independently of their timing of replication in an order roughly corresponding to their distance from parS sites [29], [41]. The results of this current study suggest that the segregation of chromosome I loci was no longer correlated to their genetic distance from parS1 sites when these sites had been displaced (Figures 3 and S44), but instead followed the replication program. The efficient segregation of V. cholerae chromosome I lacking parS1 sites suggests that parS1-polar mobilisation is not essential for the segregation process. The influence of the replication program on the organization and segregation of chromosome I was further assessed by inserting an ectopic origin of replication in the left replichore. The segregation and the organisation of the bulk of chromosome I was not altered if the partition machinery remained intact (Figure 5). However, when combined with the deletion of the parS1 sites, the addition of an ectopic origin of replication affected the positioning of loci proximal to the two functional origins (Figures 5 and 4B). Taken together, these results suggest that the longitudinal organization of chromosome I was preserved by the replication program when its partition system was disrupted (Figures 5 and 6A, ΔparS1).

In E. coli and B. subtilis, modification of the replication program by the addition or the displacement of the replication origin does not influence the organisation of the bacterial chromosome [40], [42]. In particular, replication initiation from an origin located in the middle of the right replichore did not disrupt the transversal organisation of the E. coli chromosome [40]. However, it increased the proportion of cells in which the origin sisters were displaced to the outer edges of the nucleoid, i.e. towards the cell poles, suggesting that replication program could contribute to polar mobilisation in E. coli. Moreover, the E. coli chromosome lost its transversal organisation and adopted a longitudinal organisation in mukB mutant cells [43], [44]. Preliminary studies suggest that deletion of the mukBEF genes in V. cholerae, which does not confer any loss of cell viability or any aberrant cell morphology (data not shown), does not alter the positioning and segregation of oriI and L3I (Figure S24). Nevertheless, future work is needed to investigate the contribution of the MukBEF system to the organization and segregation of the two V. cholerae chromosomes.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the partition machinery and the replication program contribute to the polar mobilization of the origin regions in V. cholerae. We hypothesise that it is the genomic proximity of parS sites to the oriC site, which is a conserved feature of most bacterial chromosomes that serves to ensure the convergence of their polar positioning activities.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and strains

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables S1 and S2 respectively. All V. cholerae mutants were constructed by integration-excision or natural transformation (Protocols and details on the construction of each strain in Text S1). To this end, a derivative of the El Tor V. cholerae N16961 was rendered competent by the insertion of hapR by specific transposition [45]. Engineered strains were confirmed by PCR.

Fluorescence microscopy

Cells were observed in Minimal Media to have only a single copy of each chromosome after division. Protocols for Microscopy are detailed in Text S1. The snapshot images were analysed using the Matlab-based software MicrobeTracker [45], [46], see details for the analysis in Supplementary Text S1.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. KuempelPL, HensonJM, DircksL, TecklenburgM, LimDF (1991) dif, a recA-independent recombination site in the terminus region of the chromosome of Escherichia coli. New Biol 3 : 799–811.

2. PossozC, JunierI, EspeliO (2012) Bacterial chromosome segregation. Front Biosci 17 : 1020–1034.

3. Vallet-GelyI, BoccardF (2013) Chromosomal organization and segregation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Genet 9: e1003492.

4. HarmsA, Treuner-LangeA, SchumacherD, Sogaard-AndersenL Tracking of Chromosome and Replisome Dynamics in Myxococcus xanthus Reveals a Novel Chromosome Arrangement. PLoS Genet 9: e1003802.

5. ViollierPH, ShapiroL (2004) Spatial complexity of mechanisms controlling a bacterial cell cycle. Curr Opin Microbiol 7 : 572–578.

6. SrivastavaP, FeketeRA, ChattorajDK (2006) Segregation of the replication terminus of the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes. J Bacteriol 188 : 1060–1070.

7. FiebigA, KerenK, TheriotJA (2006) Fine-scale time-lapse analysis of the biphasic, dynamic behaviour of the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes. Mol Microbiol 60 : 1164–1178.

8. FogelMA, WaldorMK (2006) A dynamic, mitotic-like mechanism for bacterial chromosome segregation. Genes Dev 20 : 3269–3282.

9. LivnyJ, YamaichiY, WaldorMK (2007) Distribution of centromere-like parS sites in bacteria: insights from comparative genomics. J Bacteriol 189 : 8693–8703.

10. VecchiarelliAG, MizuuchiK, FunnellBE Surfing biological surfaces: exploiting the nucleoid for partition and transport in bacteria. Mol Microbiol 86 : 513–523.

11. SaljeJ, GayathriP, LoweJ (2010) The ParMRC system: molecular mechanisms of plasmid segregation by actin-like filaments. Nat Rev Microbiol 8 : 683–692.

12. OguraT, HiragaS (1983) Partition mechanism of F plasmid: two plasmid gene-encoded products and a cis-acting region are involved in partition. Cell 32 : 351–360.

13. MartinKA, FriedmanSA, AustinSJ (1987) Partition site of the P1 plasmid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84 : 8544–8547.

14. ThanbichlerM, ShapiroL (2006) MipZ, a spatial regulator coordinating chromosome segregation with cell division in Caulobacter. Cell 126 : 147–162.

15. YamaichiY, FogelMA, WaldorMK (2007) par genes and the pathology of chromosome loss in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 : 630–635.

16. LasockiK, BartosikAA, MierzejewskaJ, ThomasCM, Jagura-BurdzyG (2007) Deletion of the parA (soj) homologue in Pseudomonas aeruginosa causes ParB instability and affects growth rate, chromosome segregation, and motility. J Bacteriol 189 : 5762–5772.

17. IretonK, GuntherNWt, GrossmanAD (1994) spo0J is required for normal chromosome segregation as well as the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 176 : 5320–5329.

18. YamaichiY, FogelMA, McLeodSM, HuiMP, WaldorMK (2007) Distinct centromere-like parS sites on the two chromosomes of Vibrio spp. J Bacteriol 189 : 5314–5324.

19. MurrayH, ErringtonJ (2008) Dynamic control of the DNA replication initiation protein DnaA by Soj/ParA. Cell 135 : 74–84.

20. KadoyaR, BaekJH, SarkerA, ChattorajDK (2011) Participation of chromosome segregation protein ParAI of Vibrio cholerae in chromosome replication. J Bacteriol 193 : 1504–1514.

21. GruberS, ErringtonJ (2009) Recruitment of condensin to replication origin regions by ParB/SpoOJ promotes chromosome segregation in B. subtilis. Cell 137 : 685–696.

22. SullivanNL, MarquisKA, RudnerDZ (2009) Recruitment of SMC by ParB-parS organizes the origin region and promotes efficient chromosome segregation. Cell 137 : 697–707.

23. MinnenA, AttaiechL, ThonM, GruberS, VeeningJW (2011) SMC is recruited to oriC by ParB and promotes chromosome segregation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol 81 : 676–688.

24. PtacinJL, LeeSF, GarnerEC, ToroE, EckartM, et al. (2010) A spindle-like apparatus guides bacterial chromosome segregation. Nat Cell Biol 12 : 791–798.

25. SchofieldWB, LimHC, Jacobs-WagnerC (2010) Cell cycle coordination and regulation of bacterial chromosome segregation dynamics by polarly localized proteins. EMBO J 29 : 3068–3081.

26. ShebelutCW, GubermanJM, van TeeffelenS, YakhninaAA, GitaiZ (2010) Caulobacter chromosome segregation is an ordered multistep process. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 : 14194–14198.

27. YamaichiY, BrucknerR, RinggaardS, MollA, CameronDE, et al. (2012) A multidomain hub anchors the chromosome segregation and chemotactic machinery to the bacterial pole. Genes Dev 26 : 2348–2360.

28. LalouxG, Jacobs-WagnerC (2013) Spatiotemporal control of PopZ localization through cell cycle-coupled multimerization. J Cell Biol 201 : 827–841.

29. ViollierPH, ThanbichlerM, McGrathPT, WestL, MeewanM, et al. (2004) Rapid and sequential movement of individual chromosomal loci to specific subcellular locations during bacterial DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101 : 9257–9262.

30. UmbargerMA, ToroE, WrightMA, PorrecaGJ, BauD, et al. (2011) The three-dimensional architecture of a bacterial genome and its alteration by genetic perturbation. Mol Cell 44 : 252–264.

31. FogelMA, WaldorMK (2005) Distinct segregation dynamics of the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes. Mol Microbiol 55 : 125–136.

32. KahngLS, ShapiroL (2003) Polar localization of replicon origins in the multipartite genomes of Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol 185 : 3384–3391.

33. WangX, LiuX, PossozC, SherrattDJ (2006) The two Escherichia coli chromosome arms locate to separate cell halves. Genes Dev 20 : 1727–1731.

34. NielsenHJ, OttesenJR, YoungrenB, AustinSJ, HansenFG (2006) The Escherichia coli chromosome is organized with the left and right chromosome arms in separate cell halves. Mol Microbiol 62 : 331–338.

35. RasmussenT, JensenRB, SkovgaardO (2007) The two chromosomes of Vibrio cholerae are initiated at different time points in the cell cycle. EMBO J 26 : 3124–3131.

36. JoshiMC, BourniquelA, FisherJ, HoBT, MagnanD, et al. (2011) Escherichia coli sister chromosome separation includes an abrupt global transition with concomitant release of late-splitting intersister snaps. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108 : 2765–2770.

37. BrezellecP, HoebekeM, HietMS, PasekS, FeratJL (2006) DomainSieve: a protein domain-based screen that led to the identification of dam-associated genes with potential link to DNA maintenance. Bioinformatics 22 : 1935–1941.

38. MercierR, PetitMA, SchbathS, RobinS, El KarouiM, et al. (2008) The MatP/matS site-specific system organizes the terminus region of the E. coli chromosome into a macrodomain. Cell 135 : 475–485.

39. DemarreG, GalliE, MuresanL, PalyE, DavidA, et al. (2014) Differential management of the replication terminus regions of the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes during cell division. PLoS Genet [In Press].

40. WangX, LesterlinC, Reyes-LamotheR, BallG, SherrattDJ (2011) Replication and segregation of an Escherichia coli chromosome with two replication origins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: E243–250.

41. ToroE, HongSH, McAdamsHH, ShapiroL (2008) Caulobacter requires a dedicated mechanism to initiate chromosome segregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 : 15435–15440.

42. BerkmenMB, GrossmanAD (2007) Subcellular positioning of the origin region of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome is independent of sequences within oriC, the site of replication initiation, and the replication initiator DnaA. Mol Microbiol 63 : 150–165.

43. DanilovaO, Reyes-LamotheR, PinskayaM, SherrattD, PossozC (2007) MukB colocalizes with the oriC region and is required for organization of the two Escherichia coli chromosome arms into separate cell halves. Mol Microbiol 65 : 1485–1492.

44. BadrinarayananA, LesterlinC, Reyes-LamotheR, SherrattD (2012) The Escherichia coli SMC complex, MukBEF, shapes nucleoid organization independently of DNA replication. J Bacteriol 194 : 4669–4676.

45. MarvigRL, BlokeschM Natural transformation of Vibrio cholerae as a tool–optimizing the procedure. BMC Microbiol 10 : 155.

46. SliusarenkoO, HeinritzJ, EmonetT, Jacobs-WagnerC High-throughput, subpixel precision analysis of bacterial morphogenesis and intracellular spatio-temporal dynamics. Mol Microbiol 80 : 612–627.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článek Comparative Phylogenomics Uncovers the Impact of Symbiotic Associations on Host Genome EvolutionČlánek Distribution and Medical Impact of Loss-of-Function Variants in the Finnish Founder PopulationČlánek Common Transcriptional Mechanisms for Visual Photoreceptor Cell Differentiation among PancrustaceansČlánek Integrative Genomics Reveals Novel Molecular Pathways and Gene Networks for Coronary Artery DiseaseČlánek An ARID Domain-Containing Protein within Nuclear Bodies Is Required for Sperm Cell Formation inČlánek Knock-In Reporter Mice Demonstrate that DNA Repair by Non-homologous End Joining Declines with Age

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2014 Číslo 7- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- Cuba: Exploring the History of Admixture and the Genetic Basis of Pigmentation Using Autosomal and Uniparental Markers

- Clonal Architecture of Secondary Acute Myeloid Leukemia Defined by Single-Cell Sequencing

- Mechanisms of Functional Variants That Impair Regulated Bicarbonate Permeation and Increase Risk for Pancreatitis but Not for Cystic Fibrosis

- Nucleosomes Shape DNA Polymorphism and Divergence

- Functional Diversification of Hsp40: Distinct J-Protein Functional Requirements for Two Prions Allow for Chaperone-Dependent Prion Selection

- Comparative Phylogenomics Uncovers the Impact of Symbiotic Associations on Host Genome Evolution

- Activation of the Immune System by Combinations of Common Alleles

- Age-Associated Sperm DNA Methylation Alterations: Possible Implications in Offspring Disease Susceptibility

- Muscle-Specific SIRT1 Gain-of-Function Increases Slow-Twitch Fibers and Ameliorates Pathophysiology in a Mouse Model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

- MDRL lncRNA Regulates the Processing of miR-484 Primary Transcript by Targeting miR-361

- Hypersensitivity of Primordial Germ Cells to Compromised Replication-Associated DNA Repair Involves ATM-p53-p21 Signaling

- Intrapopulation Genome Size Variation in Reflects Life History Variation and Plasticity

- SlmA Antagonism of FtsZ Assembly Employs a Two-pronged Mechanism like MinCD

- Distribution and Medical Impact of Loss-of-Function Variants in the Finnish Founder Population

- Determinative Developmental Cell Lineages Are Robust to Cell Deaths

- DELLA Protein Degradation Is Controlled by a Type-One Protein Phosphatase, TOPP4

- Wnt Signaling Interacts with Bmp and Edn1 to Regulate Dorsal-Ventral Patterning and Growth of the Craniofacial Skeleton

- Common Transcriptional Mechanisms for Visual Photoreceptor Cell Differentiation among Pancrustaceans

- UVB Induces a Genome-Wide Acting Negative Regulatory Mechanism That Operates at the Level of Transcription Initiation in Human Cells

- The Nesprin Family Member ANC-1 Regulates Synapse Formation and Axon Termination by Functioning in a Pathway with RPM-1 and β-Catenin

- Combinatorial Interactions Are Required for the Efficient Recruitment of Pho Repressive Complex (PhoRC) to Polycomb Response Elements

- Recombination in the Human Pseudoautosomal Region PAR1

- Microsatellite Interruptions Stabilize Primate Genomes and Exist as Population-Specific Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms within Individual Human Genomes

- An Intronic microRNA Links Rb/E2F and EGFR Signaling

- An Essential Nonredundant Role for Mycobacterial DnaK in Native Protein Folding

- Integrative Genomics Reveals Novel Molecular Pathways and Gene Networks for Coronary Artery Disease

- The Genomic Landscape of the Ewing Sarcoma Family of Tumors Reveals Recurrent Mutation

- Evolution and Genetic Architecture of Chromatin Accessibility and Function in Yeast

- An ARID Domain-Containing Protein within Nuclear Bodies Is Required for Sperm Cell Formation in

- Stage-Dependent and Locus-Specific Role of Histone Demethylase Jumonji D3 (JMJD3) in the Embryonic Stages of Lung Development

- Genome Wide Association Identifies Common Variants at the Locus Influencing Plasma Cortisol and Corticosteroid Binding Globulin

- Regulation of Feto-Maternal Barrier by Matriptase- and PAR-2-Mediated Signaling Is Required for Placental Morphogenesis and Mouse Embryonic Survival

- Apomictic and Sexual Germline Development Differ with Respect to Cell Cycle, Transcriptional, Hormonal and Epigenetic Regulation

- Functional EF-Hands in Neuronal Calcium Sensor GCAP2 Determine Its Phosphorylation State and Subcellular Distribution , and Are Essential for Photoreceptor Cell Integrity

- Comparison of Methods to Account for Relatedness in Genome-Wide Association Studies with Family-Based Data

- Knock-In Reporter Mice Demonstrate that DNA Repair by Non-homologous End Joining Declines with Age

- Cis and Trans Effects of Human Genomic Variants on Gene Expression

- 8.2% of the Human Genome Is Constrained: Variation in Rates of Turnover across Functional Element Classes in the Human Lineage

- Novel Approach Identifies SNPs in and with Evidence for Parent-of-Origin Effect on Body Mass Index

- Hypoxia Adaptations in the Grey Wolf () from Qinghai-Tibet Plateau

- A Loss of Function Screen of Identified Genome-Wide Association Study Loci Reveals New Genes Controlling Hematopoiesis

- Unraveling Genetic Modifiers in the Mouse Model of Absence Epilepsy

- DNA Topoisomerase 1α Promotes Transcriptional Silencing of Transposable Elements through DNA Methylation and Histone Lysine 9 Dimethylation in

- The Coding and Noncoding Architecture of the Genome

- A Novel Locus Is Associated with Large Artery Atherosclerotic Stroke Using a Genome-Wide Age-at-Onset Informed Approach

- Brg1 Loss Attenuates Aberrant Wnt-Signalling and Prevents Wnt-Dependent Tumourigenesis in the Murine Small Intestine

- The PTK7-Related Transmembrane Proteins Off-track and Off-track 2 Are Co-receptors for Wnt2 Required for Male Fertility

- The Co-factor of LIM Domains (CLIM/LDB/NLI) Maintains Basal Mammary Epithelial Stem Cells and Promotes Breast Tumorigenesis

- Essential Genetic Interactors of Required for Spatial Sequestration and Asymmetrical Inheritance of Protein Aggregates

- Meiosis-Specific Cohesin Component, Is Essential for Maintaining Centromere Chromatid Cohesion, and Required for DNA Repair and Synapsis between Homologous Chromosomes

- Silencing Is Noisy: Population and Cell Level Noise in Telomere-Adjacent Genes Is Dependent on Telomere Position and Sir2

- The Two Cis-Acting Sites, and , Contribute to the Longitudinal Organisation of Chromosome I

- A Broadly Conserved G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Kinase Phosphorylation Mechanism Controls Smoothened Activity

- Requirements for Acute Burn and Chronic Surgical Wound Infection

- LIN-42, the PERIOD homolog, Negatively Regulates MicroRNA Transcription

- WAPL Is Essential for the Prophase Removal of Cohesin during Meiosis

- Expression in Planarian Neoblasts after Injury Controls Anterior Pole Regeneration

- Sox11 Is Required to Maintain Proper Levels of Hedgehog Signaling during Vertebrate Ocular Morphogenesis

- Accumulation of a Threonine Biosynthetic Intermediate Attenuates General Amino Acid Control by Accelerating Degradation of Gcn4 via Pho85 and Cdk8

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- Wnt Signaling Interacts with Bmp and Edn1 to Regulate Dorsal-Ventral Patterning and Growth of the Craniofacial Skeleton

- Novel Approach Identifies SNPs in and with Evidence for Parent-of-Origin Effect on Body Mass Index

- Hypoxia Adaptations in the Grey Wolf () from Qinghai-Tibet Plateau

- DNA Topoisomerase 1α Promotes Transcriptional Silencing of Transposable Elements through DNA Methylation and Histone Lysine 9 Dimethylation in

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy