-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Proper Actin Ring Formation and Septum Constriction Requires Coordinated Regulation of SIN and MOR Pathways through the Germinal Centre Kinase MST-1

Cytokinesis is a fundamental cellular process essential for cell proliferation of uni - and multicellular organisms. The molecular pathways that regulate cytokinesis are highly complex and involve a large number of components that form elaborate interactive networks. The fungal septation initiation network (SIN) functions as tripartite kinase cascade that connects cell cycle progression with the control of cell division. Mis-regulation of the homologous Hippo pathway in animals results in excessive proliferation and formation of tumors, underscoring the conservation and importance of these kinase networks. A second morphogenesis (MOR) pathway involves homologous components and is controlling cell polarity in fungi and higher eukaryotes. Here we show that the promiscuous functioning Ste20-related kinase MST-1 has a dual role in regulating SIN and MOR network function. Moreover, SIN and MOR coordination through MST-1 can be achieved in an enzyme-independent manner through hetero-dimerization of germinal centre kinases, providing an additional level for activity regulation of signaling networks that is not dependent on phosphate transfer. Given the functional conservation of NDR kinase signaling modules and their regulation, our work may define general mechanisms by which NDR kinase pathway are coordinated in fungi and higher eukaryotes.

Published in the journal: Proper Actin Ring Formation and Septum Constriction Requires Coordinated Regulation of SIN and MOR Pathways through the Germinal Centre Kinase MST-1. PLoS Genet 10(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004306

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004306Summary

Cytokinesis is a fundamental cellular process essential for cell proliferation of uni - and multicellular organisms. The molecular pathways that regulate cytokinesis are highly complex and involve a large number of components that form elaborate interactive networks. The fungal septation initiation network (SIN) functions as tripartite kinase cascade that connects cell cycle progression with the control of cell division. Mis-regulation of the homologous Hippo pathway in animals results in excessive proliferation and formation of tumors, underscoring the conservation and importance of these kinase networks. A second morphogenesis (MOR) pathway involves homologous components and is controlling cell polarity in fungi and higher eukaryotes. Here we show that the promiscuous functioning Ste20-related kinase MST-1 has a dual role in regulating SIN and MOR network function. Moreover, SIN and MOR coordination through MST-1 can be achieved in an enzyme-independent manner through hetero-dimerization of germinal centre kinases, providing an additional level for activity regulation of signaling networks that is not dependent on phosphate transfer. Given the functional conservation of NDR kinase signaling modules and their regulation, our work may define general mechanisms by which NDR kinase pathway are coordinated in fungi and higher eukaryotes.

Introduction

Coordination of cell growth and division is a fundamental subject in biology. Successful cytokinesis relies on the coordinated assembly and activation of an actomyosin-based contractile ring, which must be regulated in a spatially and temporally precise manner [1]–[3]. The underlying molecular pathways are highly complex and involve a large number of components forming elaborate interactive networks. Central components of these networks are the highly conserved nuclear Dbf2p-related (NDR) kinases, which are important for morphogenesis and proliferation in all eukaryotes analyzed to date [4]–[6]. These kinases represent two functional subgroups in fungi and animals. Dbf2p subfamily members are effector kinases of the fungal septation initiation network (SIN; homologous to the animal Hippo pathway; [7]), which consists of a cascade of three kinases that connects cell cycle progression with the initiation of cytokinesis [8]. Activation of the SIN by a spindle pole body (SPB)-associated small GTPase activates a Cdc14p-like phosphatase, which triggers mitotic exit [9]. Moreover, activated Dbf2p relocates to the future site of septum formation, where the kinase is required for the assembly and constriction of the cortical actomyosin ring (CAR; [10], [11]). The second group of NDR kinases controls polarity as components of a homologous morphogenesis network (the fungal MOR network; homologous to the animal Ndr1/2 pathway) [5]. In fungi this pathway plays a critical role in the polar organization of the actin cytoskeleton at cell ends, which seems, at least in part, to be achieved through regulation of Rho-type GTPases [12]–[15]. In addition, the MOR regulates the expression of multiple genes with cell wall-related functions in unicellular yeasts, including genes required for efficient cell separation [16]–[18].

Multiple data indicate that the SIN and MOR function in concert in complex and mutual antagonistic manner to coordinate the remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton during cell growth and division [5], [10], [11]. Inhibition of the fission yeast MOR network by the SIN has been shown to promote cytokinesis, while polar growth in interphase requires inhibition of the SIN by the MOR [19]–[21]. Moreover, the activity of the MOR is SIN-dependent [22], [23], consistent with the hypothesis of the MOR acting as SIN effector after septum constriction to allow cell separation. Significantly, the animal Hippo and Ndr1/2 kinase pathways also have opposing effects on cell morphogenesis and proliferation [24]–[26], indicating that this interdependence of the two NDR kinase modules is conserved among eukaryotes.

In contrast to the total separation of mother and daughter cells, which is characteristic for unicellular yeasts, the vast majority of fungi form mycelial colonies that consist of networks of branched hyphae and are compartmentalized by incomplete septa. The septal pores enable communication and transport of cytoplasm and organelles between adjacent cells. Despite the importance of septation for growth, proliferation and differentiation of molds, our understanding of septum formation and its regulation in filamentous fungi is highly fragmentary [27]–[29]. Genetic and biochemical analysis in the model molds Neurospora crassa and Aspergillus nidulans suggest that cell cycle-dependent signals of a subset of competent mitotic nuclei activate the SIN [30]–[32]. This, in turn, is critical for the cortical localization of a RHO-4/BUD-3 GTPase module complexed by its anillin-type scaffold BUD-4, which allows the generation of the CAR through a second RHO-4/RGF-3 GTPase complex [33]–[35]. In addition to these positive regulators of septum formation, several negative regulators were identified in N. crassa, whose mutation result in hyperseptated strains [36]. Most notably are LRG-1, a RHO-1-specific GTPase activating protein [14] and COT-1, POD-6 and two MOB-2 proteins, the central elements of the N. crassa MOR network [37]–[39]. Moreover, components of the RHO-1 module and the MOR network localize to forming septa, providing additional support for a function of these proteins during septation [14], [40]–[42].

We have recently determined that a hierarchical, tripartite SIN cascade, consisting of CDC-7, SID-1 and DBF-2, together with their regulatory subunits CDC-14 and MOB-1, respectively, are the central components of the SIN and are essential for septum formation in N. crassa [39], [43]. However, the comparative phenotypic characterization of mutants in these SIN components revealed that Δsid-1 and Δcdc-14 deletion strains behave differently than mutants in the remaining SIN components, suggesting that the presentation of the SIN as a linear kinase cascade may represent a simplified view. In this study, we characterized MST-1, the third germinal centre (GC) kinase present in N. crassa and other fungi, which we show is important for proper CAR formation and septum constriction. We provide evidence that MST-1 functions in parallel to SID-1 as part of the SIN, but also that MST-1 has multiple functions in regulating the MOR. Consequently, MST-1 plays an important role in coordinating the antagonistic functions of the SIN and MOR pathways during septum formation.

Results

The germinal centre kinase MST-1 displays features reminiscent of SIN as well as MOR components

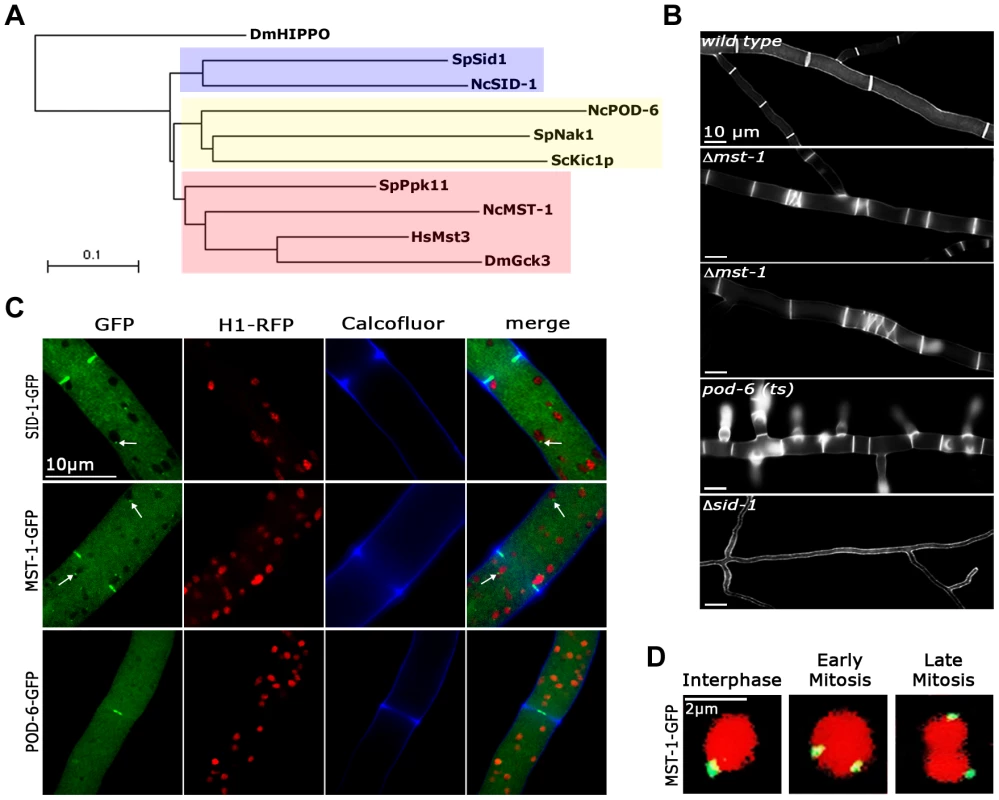

Germinal centre (GC) kinases represent a large family of functionally diverse proteins that can be grouped into eight subfamilies [44]. Fungal GC kinases represent three functionally distinct subgroups of subfamily III (Figure 1 A; Figure S1). N. crassa POD-6 and the related budding and fission yeast kinases Kic1p and Nak1, respectively, clustered together, in line with their conserved function as upstream components of the MOR network [38], [45], [46]. The second subgroup is represented by the SIN kinases Sid1/SID-1 [43], [47]. Proteins of the third subgroup are most closely related to animal group III GC kinases. The fission yeast member Ppk11 was recently characterized as auxiliary factor of the MOR pathway that supports cell separation [48], while the N. crassa protein NCU00772/MST-1 had been implicated as part of the SIN in a preliminary analysis [49].

Fig. 1. MST-1 displays features reminiscent of SIN as well as MOR components.

(A) Phylogenetic comparison of fungal GC kinases. The tree was generated by the neighbour-joining method based on a ClustalW alignment of the indicated S. cerevisiae, S. pombe and N. crassa proteins. HsMst3 and DmGck3 were used as examples for animal group III GC kinases. The GC kinase II DmHippo was used as outgroup member (multiple alignment parameters: open gap penalty 10.0, extend gap penalty 0.0, delay divergent 40%, gap distance 8, similarity matrix blosum). An extended phylogram of fungal GC kinases is found in Figure S1. (B) Phenotypic characteristics of Δmst-1, pod-6(ts) and Δsid-1 during septum formation. Note the presence of closely spaced septa (second panel) and abnormal spirals (third panel) in Δmst-1. For comparison, pod-6-defective cells produce multiple, closely spaced septa, while Δsid-1 cells are aseptate. Cell wall and septa were labeled with Calcofluor White. (C) Functional GFP fusion proteins of the three GC kinases SID-1, MST-1 and POD-6 localize as constricting rings at septa. SID-1 and MST-1, but not POD-6 also localize to spindle pole bodies (arrows), while POD-6 accumulated as dot in the distal region of the Spitzenkörper and as apex-associated crescent (Figure S2). Nuclei were labeled with histone H1-RFP and the cell wall was stained with Calcofluor White. (D) MST-1-GFP associated with SPBs of interphase nuclei as well as during early and late mitotic stages (as indicated by nuclear morphology). Nuclei were labeled with histone H1-RFP. In order to address these discrepancies, we compared localization pattern and mutant characteristics of MST-1/Δmst-1 with those of SIN and MOR components. Δmst-1 formed multiple, closely spaced septa similar to the hyperseptation defects observed in MOR mutants and produced abnormal cross walls in the form of cortical spirals in older hyphal segments (Figure 1 B). However, a MST-1-GFP fusion construct, which complemented all Δmst-1 defects, associated with spindle pole bodies (SPBs) and constricting septa (Figure 1 C; Video S1), a localization pattern characteristic for fungal SIN components. Moreover, the association of MST-1 with both SPBs was constitutive and cell cycle independent (Figure 1 D), consistent with the localization of the three N. crassa SIN kinases [43]. In contrast, a POD-6-GFP fusion protein localized at the hyphal tip in a dot-like structure in the Spitzenkörper, as membrane-associated apical crescent and around the septal pore (Figure 1 C; Figure S2), reflecting the localization pattern of other MOR components [41], [42]. Neither POD-6 nor its target kinase COT-1 and regulatory subunit MOB-2A were detected at SPBs. Therefore, we compared the kinetics of cortex recruitment of the two NDR kinases with that of MST-1 during septum initiation (Figure 2). DBF-2 and MST-1 formed cortex-associated rings 2 : 50±0 : 45 min (n = 17) and 2 : 55±1 : 25 min (n = 19), respectively, prior to the start of septum constriction, which was monitored by plasma membrane invagination and defined as time point 0 : 00 min (labeled with FM4-64). In contrast, COT-1 was only observed after CAR constriction had started (0 : 39±0 : 13 min; n = 15). Furthermore, the fusion protein strongly labeled the mature septal pore [41], [42].

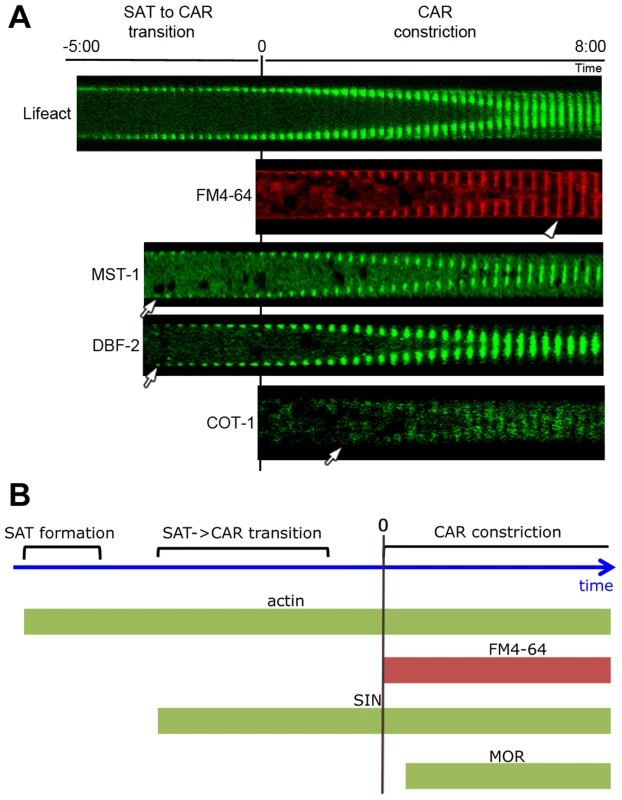

Fig. 2. Kinetics of cortex association of SIN and MOR components DBF-2, MST-1 and COT-1 during septum formation.

(A) Composite images of time series of the indicated proteins during septum formation. The start of plasma membrane invagination was monitored with FM4-64 and defined as time point 0:00 min. Arrows indicate the time point when the GFP-fusion proteins occurred first at the cell cortex and arrowhead the time point of complete CAR constriction. (B) Schematic representation of the chronology of emergence of the SIN and MOR at the cell cortex relative to the actin cytoskeleton. In addition to the observed septation defects in subapical hyphal regions, Δmst-1 displayed only minor vegetative abnormalities. Mycelial extension rates, colony behavior and conidiation pattern were similar to wild type (wt; data not shown). However, sexual differentiation was affected in Δmst-1. Mutant ×wt crosses resulted in ca. 50% of round (yet fully viable) ascospores, in contrast to the typical pea-shaped progeny generated in wt×wt crosses (Figure S3). Moreover, Δmst-1×Δmst-1 crosses resulted in the formation of empty perithecia lacking asci, and the formation of ascospores was abolished. We also observed synthetic behavior of Δmst-1 with SIN-, but not MOR-defective strains during sexual development. Δmst-1×Δcot-1 crosses resulted in the expected segregation of round and normally shaped ascospores, although the total number of generated ascospores was reduced. In contrast, Δmst-1×Δdbf-2 crosses generated empty perithecia and no ascospores. The same synthetic effect was observed in crosses of Δmst-1 with Δsid-1 or Δcdc-7, while crosses of Δmst-1×Δpod-6 produced round as well as pea-shaped spores.

MST-1 controls proper CAR formation

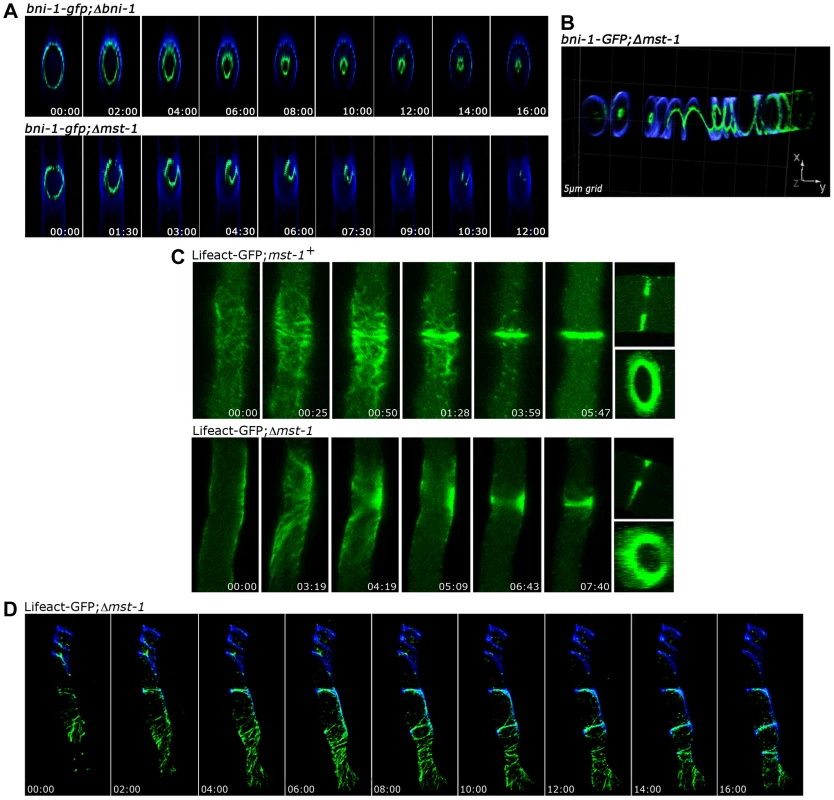

Fungal septum formation is driven through the constriction of a cortex-associated actomyosin ring (CAR; [50], [51]). Thus, we compared the dynamics of septum formation in wt and Δmst-1 by monitoring the behavior of the sole formin BNI-1 present in N. crassa [35]. A functional BNI-1-GFP fusion construct formed cortical rings with uniform signal intensity in wt cells, and septum constriction was concentric, resulting in centrally positioned septal pores (Figure 3 A upper panel; Video S2). In contrast, BNI-1 frequently (i.e. in 38 of 47 septation events analyzed) formed asymmetric rings that led to acentric constriction and asymmetric septal pores in Δmst-1 (Figure 3 A lower panel; Videos S3, S4). BNI-1 also associated with extensive cortical Calcofluor White-labeled spirals (Figure 3 B), indicating that the secretory machinery is still correctly targeted and that growth of the cell wall at these sites is not inhibited through the mis-organized formin rings and spirals. Moreover, CAR assembly and constriction was directly monitored using a Lifeact-GFP construct recently developed for N. crassa [52]. Lifeact-GFP labeled a mesh of F-actin cables and patches named the septal actin tangle (SAT), which appeared approximately >5 min prior to septum constriction at the future septation site in wt (Figure 2; [52], [53]). After 2–3 min, the SAT coalesced to form the CAR (Figure 3 C upper panel; Video S5). In contrast to wt, the F-actin meshwork was mis-organized and the actin cables were irregularly distributed in Δmst-1, and the SAT to CAR transition lasted much longer (8 : 30±2 : 00 min in Δmst-1 (n = 12) compared to 2 : 30±0 : 30 min in wt (n = 15)). This failure of correct CAR assembly resulted in acentric constriction and asymmetric position of septal pores or the formation of open actin spirals, which were unable to constrict (Figure 3 C lower panel, Figure 3 D; Videos S6, S7).

Fig. 3. MST-1 is required for proper contractile actin ring formation.

(A) 4D reconstruction of z-stacks in time lapse series revealed cortical, concentrically constricting BNI-1-GFP rings in wt cells, which resulted in centrally positioned septal pores. In contrast, BNI-1 formed asymmetric and frequently open BNI-1-GFP rings in Δmst-1 that led to acentric CAR constriction and asymmetric septal pores. (B) 3D reconstruction of z-stacks illustrates BNI-1-GFP association with extensive cortical Calcofluor White-labeled spirals in Δmst-1. (C) Comparison of actin dynamics during CAR assembly and constriction in wt and Δmst-1. Lifeact-GFP labeled a dynamic meshwork of actin cables and patches around the future septation site in wt cells, which subsequently coalesced to form the CAR. The actin meshwork was mis-organized and irregularly distributed in Δmst-1 (D) 4D reconstruction of z-stacks in time lapse series visualized open actin spirals labeled by Lifeact-GFP, which were unable to constrict. Cell wall, septa and cortical spirals were labeled by Calcofluor White. The SIN kinase CDC-7 regulates SID-1 and MST-1 in an antagonistic manner

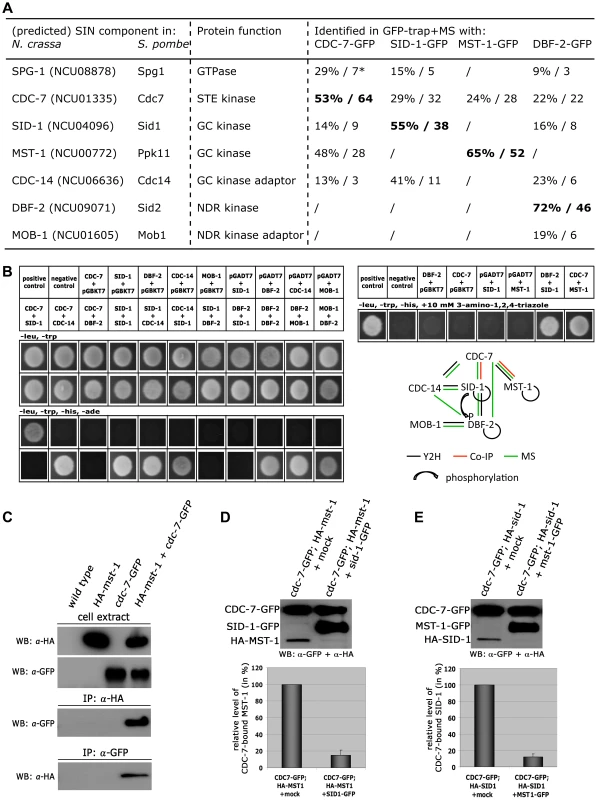

GFP-trap affinity purification experiments coupled to mass spectrometry (MS) allowed determining MST-1-interacting proteins and its relationship to the SIN (Figure 4 A; Table S1). Precipitates of a DBF-2-GFP fusion recovered all components of the central SIN cascade, including its regulatory subunit MOB-1, the two upstream kinases CDC-7 and SID-1 and its adaptor CDC-14, and the predicted GTPase SPG-1/NCU08878. In contrast, SID-1-GFP recovered only its subunit CDC-14 and the upstream components CDC-7 and SPG-1, but not the DBF-2/MOB-1 complex, indicating a less robust interaction with the SIN effector kinase. MST-1 did not co-purify these two kinases. However, CDC-7-GFP co-precipitated both GC kinases SID-1 and MST-1 in addition to the GTPase SPG-1 and the SID-1 adapter CDC-14, while only CDC-7 co-purified with MST-1. Next, we determined physical interactions of the SIN components in yeast two hybrid (Y2H) assays (Figure 4 B). DBF-2 and SID-1 directly interacted with their regulatory subunits MOB-1 and CDC-14, respectively, and both kinases were able to form homo-dimers. In addition, a weak interaction was detected between the two kinases. Interestingly, the upstream kinase CDC-7 did not directly interact with SID-1, but was connected to the GC kinase via its adaptor CDC-14. Finally, we detected a physical interaction of MST-1 and CDC-7 in Y2H tests (Figure 4 B), which was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments (Figure 4 C).

Fig. 4. CDC-7 forms mutually exclusive complexes with SID-1 and MST-1.

(A) AP-MS data from two independent biological replicates were used for identification of predicted SIN components. * denotes % protein coverage and number of unique peptides of the identified protein. Only SIN components identified in both replicate purifications and absent from a control data set obtained in purifications with GFP-expressing cells are displayed (Table S1). GFP-fusion constructs used as bait proteins are in bold type. (B) Yeast two-hybrid tests with the indicated SIN constructs and summary schema of the observed interactions. (C) Reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation experiments of CDC-7-GFP and HA-MST-1 from cell extracts co-expressing both functionally tagged proteins indicate interaction of the two kinases. (D, E) GC-kinase displacement assays of precipitated CDC-7-GFP/GC-kinase complexes. Addition of a second, separately purified GC kinase, but not a mock-IP precipitate to these complexes reduced the abundance of the co-purified GC kinase. The upper panel displays a representative experiment, while three independent experiments are quantified in the lower graph. Our GFP-trap + MS data indicated that SID-1 and MST-1 only co-purified together, when we used CDC-7 as bait, while the two GC kinases behaved mutually exclusive in the other co-purifications. Moreover, we were unable to co-purify SPG-1, CDC-14 and the DBF-2/MOB-1 complex with MST-1, suggesting the presence of distinct CDC-7/SID-1 and CDC-7/MST-1 complexes. In order to further strengthen this assumption, we performed in vitro displacement assays, in which a GFP-trapped CDC-7-GFP/HA-GC kinase complex precipitated from a strain co-expressing both tagged kinases was incubated with excessive amounts of separately purified second GC kinase (Figure 4 D, E). The composition of the resulting CDC-7 complex was determined by Western blot analysis after pelleting the sepharose bead-associated proteins. In these assays, we were able to replace CDC-7-associated SID-1 with MST-1 and vice versa, indicating that the two GC kinases form mutually exclusive assemblies with CDC-7.

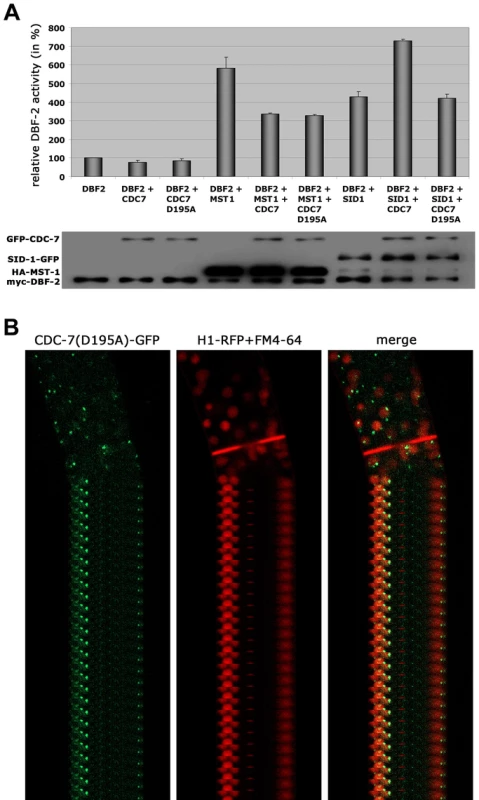

Based on these interaction data, we hypothesized that the two GC kinases function in parallel as part of the SIN. Consistent with this prediction, we determined that purified SID-1 and MST-1 both stimulated DBF-2 activity in vitro (Figure 5 A). As predicted for the stepwise function of the SIN kinase cascade, addition of CDC-7 to the SID-1/DBF-2 kinase mixture further stimulated DBF-2, while addition of kinase-dead CDC-7(D195A) did not. In contrast, CDC-7 inhibited MST-1-driven stimulation of DBF-2, and this inhibition did not require functional CDC-7. As control, we confirmed that the kinase activity of CDC-7 was essential for complementation of the deletion defects of Δcdc-7 (data not shown). Strikingly, we found that septum association of CDC-7, but not its localization at SPBs was dependent on the functionality of CDC-7 (Figure 5 B). In contrast, the localization of DBF-2 and MST-1 at SPBs and septa did not require enzyme activity (Figure S4), potentially because homo-dimerization of the kinase-dead version with a functional kinase variant allowed correct localization in a wt background.

Fig. 5. The regulation of MST-1 and SID-1 by CDC-7 is based on distinct mechanisms.

(A) In vitro DBF-2 activity assays after addition of the indicated kinases. MST-1-stimulated DBF-2 activity is inhibited by addition of CDC-7 or CDC-7(D195A), while SID-1-stimulation requires active CDC-7. Western blot analysis of the precipitated proteins was used to determine comparable kinase levels (n = 4). (B) A GFP fusion construct of wt CDC-7 localized to spindle pole bodies and accumulated around the mature septal pore, while a CDC7(D195A)-GFP construct exclusively localized to SPBs. Nuclei were labeled with histone H1-RFP and plasma membrane with FM4-64. MST-1 regulates the MOR network by two distinct mechanisms

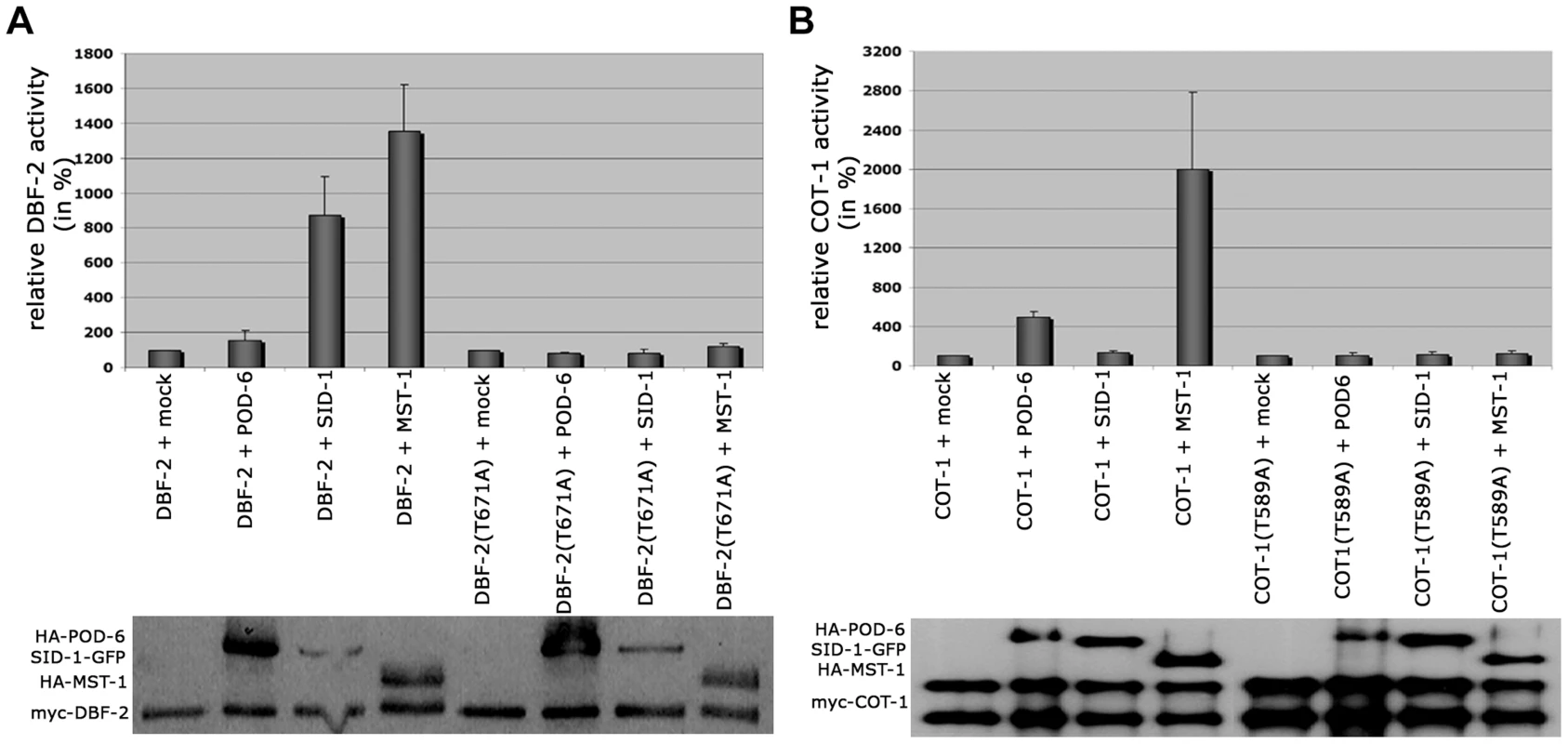

Based on the presented genetic, biochemical and life imaging analyses, we conclude that MST-1 is part of the SIN and functions in parallel to SID-1. However, the hyperseptation defects observed in Δmst-1 partly phenocopied characteristics of MOR mutants. Consistent with the hypothesis that MST-1 may regulate both NDR kinase pathways was the ability of purified MST-1 to activate COT-1 in addition to its activation of DBF-2 (Figure 6 A, B). As control, we confirmed that SID-1 only stimulated DBF-2, while POD-6 was specific for COT-1, confirming that MST-1 has a specific function as promiscuous activator of both pathways. Moreover, MST-1 was unable to stimulate DBF-2 and COT-1 variants, in which their hydrophobic motif phosphorylation sites were modified, indicating that MST-1 activates both target kinases by hydrophobic motif phosphorylation.

Fig. 6. SID-1 and POD-6 are pathway-specific activators of the SIN and MOR, while MST-1 regulates both NDR kinase pathways.

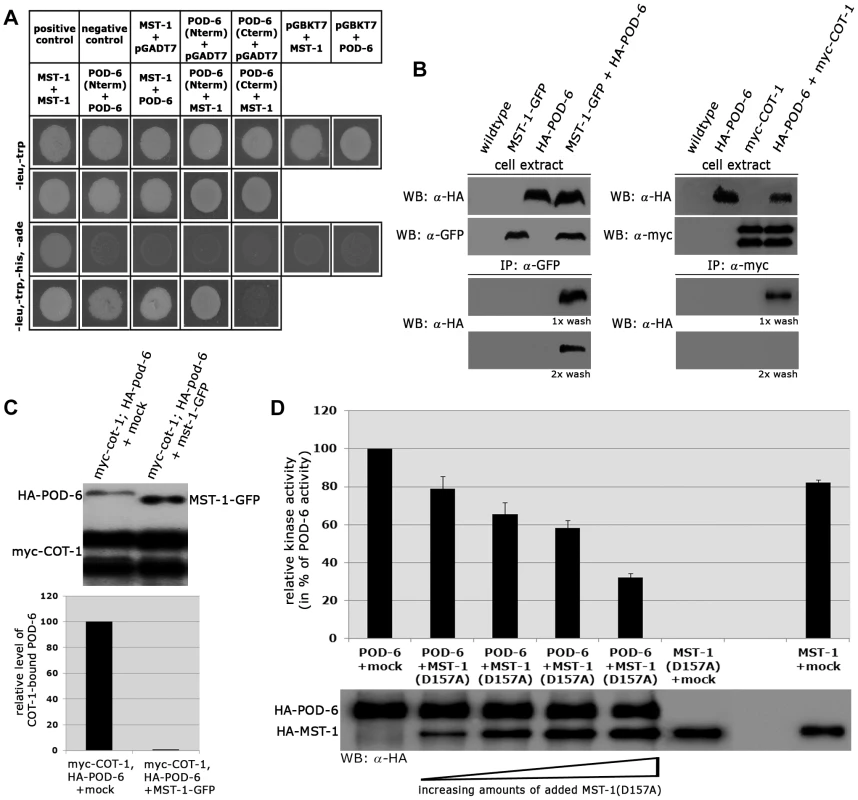

(A) In vitro kinase assays of precipitated MST-1 and SID-1 specifically stimulated DBF-2, but not DBF-2(T671A). (B) COT-1 was specifically phosphorylated by the upstream GC kinases POD-6 and MST-1, but not by SID-1. Western blot analysis of the precipitated proteins was used to determine comparable kinase levels. Because we had detected several POD-6-specific peptides in one of the two MST-1-GFP GFP-trap+MS analyses (Table S1), we asked if MST-1 also interacted with the MOR pathway. Y2H experiments confirmed the physical interaction of MST-1 with POD-6 as well as the capability of both kinases to form homo-dimers through their kinase domains (Figure 7 A). Moreover, co-IP experiments suggested that the MST-1/POD-6 complex was more stable and withstood to more stringent wash conditions than the COT-1/POD-6 interaction (Figure 7 B). Moreover, POD-6 was replaced by MST-1 by adding separately purified MST-1 to the COT-1/POD-6 complex (Figure 7 C). Thus, a second mechanism of MST-1-dependent regulation of the MOR could involve dimerization of POD-6 and MST-1 and thereby inactivation of the GC kinase hetero-dimer. Indeed, when we titrated purified POD-6 with increasing levels of a kinase-dead version of MST-1(D157A) the activity of POD-6 decreased, while addition of a mock precipitate did not interfere with POD-6 activity (Figure 7 D).

Fig. 7. MST-1/POD-6 hetero-dimerization inhibits POD-6.

(A) Yeast two-hybrid tests indicate hetero-dimerization of MST-1 and POD-6. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation experiments of MST-1-GFP and HA-POD-6 and of myc-COT-1 and HA-POD-6 from cell extracts co-expressing both functionally tagged proteins indicate interaction of the two kinase pairs. However, the MST-1/POD-6 interaction was more stable and withstood two washes with IP buffer, while the interaction between COT-1 and POD-6 was abolished under these conditions. (C) Protein displacement assay of a precipitated myc-COT-1/HA-POD-6 complex by the addition of separately purified MST-1 kinase, but not a mock-IP precipitate abolished the COT-1/POD-6 interaction. The upper panel displays a representative experiment, while three independent experiments are quantified in the lower graph. (D) POD-6 activity was determined in vitro in the presence of increasing levels of added kinase-dead MST-1(D157A) (n = 4). Discussion

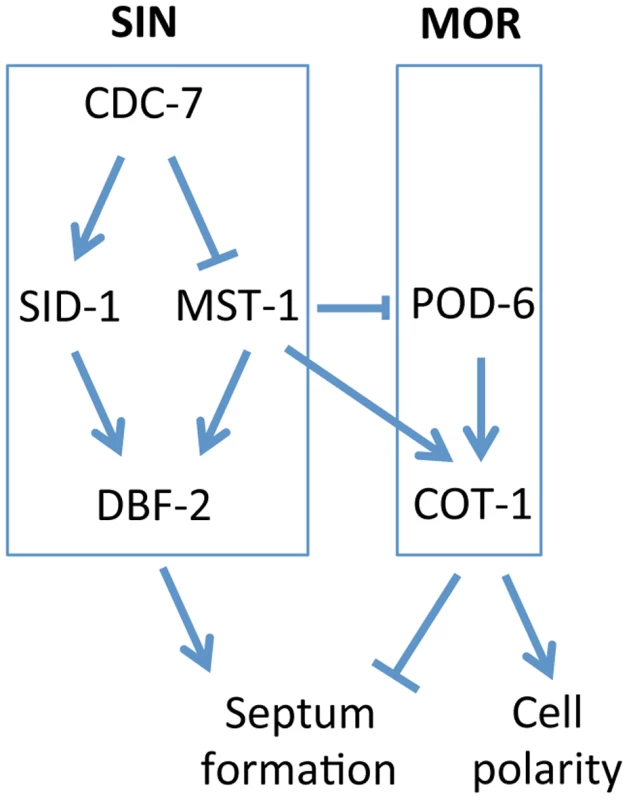

GC kinases function as central components of the SIN and MOR networks, which have antagonistic functions in the regulation of septation in unicellular as well as filamentous fungi [5], [8], [20]. In this study, we report the characterization of MST-1, the third type III GC kinase present in fungi, and dissect its dual function during SIN and MOR signaling (summarized in Figure 8). Our results demonstrate that MST-1 is a SIN-associated kinase that physically interacts with CDC-7 and functions in parallel to SID-1 to activate DBF-2. However, the interaction data strongly suggest that MST-1 is not part of the central SIN cascade, but forms a distinct complex with CDC-7. As predicted for the tripartite kinase cascade, active CDC-7 is required to stimulate hydrophobic motif phosphorylation of DBF-2 by SID-1. In contrast, MST-1 activity is negatively regulated through CDC-7 in a mechanism that does not require active kinase, indicating that the regulation of SID-1 and MST-1 through CDC-7 is based on distinct mechanisms. A possible function of MST-1 in fine-tuning the SIN may be achieved in the generation of an incoherent type 4 feedforward loop through the two, parallel functioning, but negatively regulated CDC-7/SID-1 and CDC-7/MST-1 complexes that together activate DBF-2. This rarely found regulatory motif may allow for adaptive and thus robust SIN activity [54]. This hypothesis is supported by the phenotypic characteristics of N. crassa SIN mutants, which revealed less severe defects of sid-1 mutants compared to strains deficient for cdc-7 or dbf-2 [43]. In summary, these results indicate that the composition and function of the SIN as a linear kinase cascade represents a simplified view. Our biochemical data also imply that the CDC-7/MST-1 complex may function independently of the GTPase SPG-1, a speculation that requires further exploration.

Fig. 8. Model for the proposed interaction of the SIN and MOR networks during septation in N. crassa.

See text for details. The maturation of the CAR in N. crassa is driven by the coalescence of a filamentous actin meshwork, called the SAT [50], [52], [53]. The association of all SIN components except CDC-7 approximately 3 min prior to the start of CAR constriction coincides with the time window of SAT to CAR transition, and thus the SIN is likely involved in this process. However, the aseptate nature of sin mutants precludes a detailed analysis of CAR function in these strains. Here we show that the SIN-associated kinase MST-1 plays a significant role in the proper assembly and constriction of the CAR. The defects generated by mst-1 mutants allow visualizing defects during the transition of SAT to CAR and imply a central function of the SIN in CAR maturation and in CAR constriction. Life imaging of actin as well as formin dynamics revealed two striking defects in Δmst-1. First, the CAR was frequently generated in an asymmetric manner, resulting in its acentric constriction and the formation of mispositioned septal pores. Moreover, the transition from the SAT to the CAR at the future septation site was delayed about 3-4-fold compared to wt cells, and the SAT frequently failed to coalesce into a functional CAR, generating constriction-defective spirals. In summary, we speculate that this complex phenotype is the result of mis-regulated septum initiation; i.e. the trigger required for septum placement/initiation may not be terminated, but can signal into the neighboring area to allow the sequential formation of septa and/or spirals if the SAT does not properly coalesce into a functional CAR (Video S4).

All SIN kinases, including MST-1, also localize in a cell cycle-independent manner to both SPBs. This pattern differs from the localization of homologous kinases in budding and fission yeast. In these unicellular models, only the terminal kinase constitutively associates with both SPBs and relocates after its activation at the SPB to the septum, while the upstream kinases associate only with one SPB in a cell cycle-dependent manner and do not relocate [10], [55]. This re-localization of the activated Ndr kinase is thought to be important for controlling the coordination between cell cycle progression and cell division. Strikingly, SIN activation in A. nidulans does not require its previous interaction with the SPB [32], and localization of the entire SIN at SPBs is cell cycle independent in N. crassa. Moreover, we found that the activity of CDC-7 is essential for its localization to septa, but not its association with the SPB. These data strongly suggest differential regulation of the SIN in uninuclear and syncytial fungi. The mechanism for positioning new septa in a multi-nuclear syncytium is currently unresolved [27], [28]. Although the SIN is a prime candidate for transmitting nuclear signals that are required for the selection of future septation sites [27], [28], [30], we have currently no information if SPB association of the SIN has any function during vegetative hyphal growth.

MST-1 also interacts with and regulates several components of the MOR network. First, MST-1 activates the MOR effector kinase COT1 through hydrophobic motif phosphorylation, a mechanism previously shown for other fungal and animal NDR kinases [41], [43], [56]–[58]. This dual function of SIN and MOR regulation reflects NDR kinase signaling in higher eukaryotes, where the GC kinase Hippo has been shown to activate two NDR kinases that regulate cell proliferation as well as polar morphogenesis, respectively [59]–[61]. Moreover, MST-1 can form heterodimers with the MOR kinase POD-6, and this interaction results in inhibition of the GC kinase complex. Thus, MST-1 can stimulate as well as inhibit MOR signaling. Although the functional significance of this dual function of MST-1 is yet unresolved, the N. crassa MOR likely has multiple functions during septation. First, MOR mutants are characterized by abundant, closely spaced septa, arguing for an early function of the MOR in the inhibition of septum initiation. However, COT1, its regulatory subunit MOB-2A, and POD-6 associate with the CAR only after the start of septum constriction and primarily label the mature septal pore (this study; [41], [42]). Thus, the MOR may also be critical to regulate termination of constriction and proper pore formation/maintenance. Thus, although originally thought to constitute distinct modules, antagonistic cross-talk between the SIN and MOR occurs at multiple levels (this study; [19], [21]). Further analysis is required to dissect their individual impact for the coordinated action of both networks during cell division.

Materials and Methods

Strains, media and growth conditions

Strains used in this study are listed in Table S2. Genetic procedures and media used for handling N. crassa are available through the Fungal Genetic Stock Center (www.fgsc.net; [62]).

Two hybrid plasmids and methods

The Matchmaker Two-Hybrid system 3 (Clontech, USA) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA of genes of interest for two hybrid tests was amplified with primers listed in Table S3 spanning the coding region from start to stop codon as annotated by the N. crassa database (http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/neurospora/MultiHome.html) and cloned either into the pGADT7 vector containing the GAL4 activation domain or into pGBKT7 containing the DNA-binding domain. Because the pGBKT7-POD-6 fusion protein was determined to be self-activating, we generated two fragments containing the N-terminal kinase domain (aa 1–412) and C-terminal non-catalytic domain of POD-6 (aa 415–929). Fusion proteins were (co-) expressed in S. cerevisiae AH109 and potential interactions determined by growth tests on SD medium lacking the amino acids adenine, histidine, leucine and tryptophan or on SD medium supplemented with 10 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole and lacking leucine, tryptophane and histidine.

Plasmid construction and fungal expression of tagged proteins

To obtain strains for the subcellular localization and expression of GFP-tagged POD-6 and HA/GFP-tagged MST-1 fusion proteins from the his-3 locus, their open reading frames were amplified by PCR as annotated by the N. crassa database using primers listed in Table S3 and introduced via SpeI/PacI, BamHI/EcoRI or XbaI/BamHI, respectively, into pMF272 or pHAN1 [63]–[65]. The kinase dead versions of CDC-7 and MST-1 were generated by site-directed mutagenesis according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene). The final plasmids were transformed into his-3, nic-3;his-3 or trp-1;his-3 and were selected for complementation of the his-3 auxotrophy. Strains expressing the fusion constructs were crossed with the respective deletion strain and the progeny assayed for hygromycin resistance, GFP expression and complementation of the mutant growth/septation defects. Alternatively, histidine auxotrophic deletion strains were generated and directly transformed with plasmids allowing expression of the fusion proteins from the his-3 locus, and under control of the inducible Pccg-1 promoter.

Microscopy

Low magnification analysis of fungal hyphae or colonies was performed as described [66], [67] using an SZX16 stereomicroscope, equipped with a Colorview III camera and CellD imaging software (Olympus). In order to avoid accumulation of suppressor mutations, aseptate deletion strains were maintained as heterokaryons. An inverted Axiovert Observer Z1 microscope (Zeiss) equipped with a CSU-X1 A1 confocal scanner unit and a QuantEM 512SC camera (Photometrics) was used for spinning disk confocal microscopy [68]. Slidebook 5.0 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations) was used for image/video acquisition, deconvolution and image analysis. Cell wall and plasma membrane were stained with Calcofluor White (2 µg/ml-1) and FM4-64 (1 µg/ml-1) respectively. Time-lapse imaging was performed at capture intervals of 20–30 s for periods up to 15 min using the oil immersion objective 100×/1.3. Image series were converted into movies (*.movs). For confocal live-cell imaging, we used an inverted LSM-510 Meta laser scanning microscope (Zeiss) equipped with an argon ion laser for excitation at 488 nm wavelength and GFP filters for emission at 515–530 nm and a 63× (PH3)/1.4 N.A. oil immersion objective [69]. Laser intensity was kept to a minimum (1.5%) to reduce photobleaching and phototoxic effects. Time-lapse imaging was performed at scan intervals of 3 to 15 s for periods up to 40 min. Image resolution was 512×512 pixels and 300 dpi. Confocal images were captured using LSM-510 software and evaluated with an LSM 510 Image Examiner.

Protein methods

Liquid N. crassa cultures were grown at room temperature, harvested gently by filtration using a Büchner funnel and ground in liquid nitrogen. The pulverized mycelium was mixed 1∶1 with IP-Buffer (50 mM Tris/HCL pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1% NP-40, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM PEFAbloc SC, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM Na3VO4, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM benzamidine, 2 ng/µl pepstatin A, 10 ng/µl aprotinin, 10 ng/µl leupeptin) and centrifuged twice at 4°C (15 min at 4500 g and 30 min at 14000 g) to obtain crude cell extracts. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed with cell extracts from fused, heterokaryotic strains that were selected by their ability to grow on minimal media lacking supplements. Protein-decorated beads were washed twice with IP buffer, and immunoprecipitated proteins were recovered by boiling the beads for 10 min at 98°C in 3× Laemmli buffer and separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Monoclonal mouse α-HA (clone HA-7, Sigma Aldrich), α-myc (9E10, Santa Cruz) and α-GFP (B2, Santa Cruz) were used in this study. Protein displacement from CDC-7-containing complexes was assayed by precipitating CDC-7-GFP from cell extracts co-expressing HA-SID-1 or HA-MST-1, respectively, and mixed with separately purified MST-1-GFP or SID-1-GFP, respectively. Precipitates of a mock-IP from wt extracts were used as controls. Samples were incubated for 30 min at RT and the suspensions subsequently centrifuged (2 min at 4000 g) to remove supernatant and washed once with IP buffer to remove displaced/unbound HA-SID-1. Immunoprecipitated proteins were recovered by boiling sepharose beads for 10 min at 98°C in 3× Laemmli buffer. GFP-trap experiments, mass spectrometry and database analysis were performed as described [68], [70]. The GFP-trap pulldown reagent is a quality GFP-binding protein derived from alpaca coupled to a monovalent matrix and was obtained from Chromotek. COT-1 and DBF-2 kinase activity assays were performed as described [43], [58] according to a modified protocol described previously for animal NDR kinase [71]. NDR kinase stimulation by upstream kinases was assayed as described [43]. GC kinase activity was determined by phosphorylation of the peptide substrate EESPELSLPFIGYTFKRFDNNFR, which was used at a final concentration of 2 mM [41]. Assay conditions were analogous to NDR kinase assays described above.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. ParkHO, BiE (2007) Central roles of small GTPases in the development of cell polarity in yeast and beyond. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71 : 48–96.

2. PollardTD, WuJQ (2010) Understanding cytokinesis: lessons from fission yeast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11 : 149–155.

3. BarrFA, GrunebergU (2007) Cytokinesis: placing and making the final cut. Cell 131 : 847–860.

4. HergovichA, StegertMR, SchmitzD, HemmingsBA (2006) NDR kinases regulate essential cell processes from yeast to humans. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7 : 253–264.

5. MaerzS, SeilerS (2010) Tales of RAM and MOR: NDR kinase signaling in fungal morphogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol 13 : 663–671.

6. HergovichA (2012) Mammalian Hippo signalling: a kinase network regulated by protein-protein interactions. Biochem Soc Trans 40 : 124–128.

7. HergovichA, HemmingsBA (2012) Hippo signalling in the G2/M cell cycle phase: lessons learned from the yeast MEN and SIN pathways. Semin Cell Dev Biol 23 : 794–802.

8. KrappA, SimanisV (2008) An overview of the fission yeast septation initiation network (SIN). Biochem Soc Trans 36 : 411–415.

9. CliffordDM, ChenCT, RobertsRH, FeoktistovaA, WolfeBA, et al. (2008) The role of Cdc14 phosphatases in the control of cell division. Biochem Soc Trans 36 : 436–438.

10. MeitingerF, PalaniS, PereiraG (2012) The power of MEN in cytokinesis. Cell Cycle 11 : 219–228.

11. WeissEL (2012) Mitotic exit and separation of mother and daughter cells. Genetics 192 : 1165–1202.

12. SchneperL, KraussA, MiyamotoR, FangS, BroachJR (2004) The Ras/protein kinase A pathway acts in parallel with the Mob2/Cbk1 pathway to effect cell cycle progression and proper bud site selection. Eukaryot Cell 3 : 108–120.

13. DasM, WileyDJ, MedinaS, VincentHA, LarreaM, et al. (2007) Regulation of cell diameter, For3p localization, and cell symmetry by fission yeast Rho-GAP Rga4p. Mol Biol Cell 18 : 2090–2101.

14. VogtN, SeilerS (2008) The RHO1-specific GTPase-activating protein LRG1 regulates polar tip growth in parallel to Ndr kinase signaling in Neurospora. Mol Biol Cell 19 : 4554–4569.

15. DasM, WileyDJ, ChenX, ShahK, VerdeF (2009) The conserved NDR kinase Orb6 controls polarized cell growth by spatial regulation of the small GTPase Cdc42. Curr Biol 19 : 1314–1319.

16. BidlingmaierS, WeissEL, SeidelC, DrubinDG, SnyderM (2001) The Cbk1p pathway is important for polarized cell growth and cell separation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 21 : 2449–2462.

17. MazankaE, AlexanderJ, YehBJ, CharoenpongP, LoweryDM, et al. (2008) The NDR/LATS family kinase Cbk1 directly controls transcriptional asymmetry. PLoS Biol 6: e203.

18. Gutierrez-EscribanoP, ZeidlerU, SuarezMB, Bachellier-BassiS, Clemente-BlancoA, et al. (2012) The NDR/LATS kinase Cbk1 controls the activity of the transcriptional regulator Bcr1 during biofilm formation in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002683.

19. RayS, KumeK, GuptaS, GeW, BalasubramanianM, et al. (2010) The mitosis-to-interphase transition is coordinated by cross talk between the SIN and MOR pathways in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Cell Biol 190 : 793–805.

20. GuptaS, McCollumD (2011) Crosstalk between NDR kinase pathways coordinates cell cycle dependent actin rearrangements. Cell Div 6 : 19.

21. GuptaS, Mana-CapelliS, McLeanJR, ChenCT, RayS, et al. (2013) Identification of SIN pathway targets reveals mechanisms of crosstalk between NDR kinase pathways. Curr Biol 23 : 333–338.

22. LeonhardK, NurseP (2005) Ste20/GCK kinase Nak1/Orb3 polarizes the actin cytoskeleton in fission yeast during the cell cycle. J Cell Sci 118 : 1033–1044.

23. KanaiM, KumeK, MiyaharaK, SakaiK, NakamuraK, et al. (2005) Fission yeast MO25 protein is localized at SPB and septum and is essential for cell morphogenesis. EMBO J 24 : 3012–3025.

24. CornilsH, KohlerRS, HergovichA, HemmingsBA (2011) Human NDR kinases control G(1)/S cell cycle transition by directly regulating p21 stability. Mol Cell Biol 31 : 1382–1395.

25. VisserS, YangX (2010) LATS tumor suppressor: a new governor of cellular homeostasis. Cell Cycle 9 : 3892–3903.

26. HergovichA, CornilsH, HemmingsBA (2008) Mammalian NDR protein kinases: from regulation to a role in centrosome duplication. Biochim Biophys Acta 1784 : 3–15.

27. HarrisSD (2001) Septum formation in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr Opin Microbiol 4 : 736–739.

28. SeilerS, Justa-SchuchD (2010) Conserved components, but distinct mechanisms for the placement and assembly of the cell division machinery in unicellular and filamentous ascomycetes. Mol Microbiol 78 : 1058–1076.

29. RiquelmeM, YardenO, Bartnicki-GarciaS, BowmanB, Castro-LongoriaE, et al. (2011) Architecture and development of the Neurospora crassa hypha - a model cell for polarized growth. Fungal Biol 115 : 446–474.

30. WolkowTD, HarrisSD, HamerJE (1996) Cytokinesis in Aspergillus nidulans is controlled by cell size, nuclear positioning and mitosis. J Cell Sci 109 (Pt 8) 2179–2188.

31. MinkePF, LeeIH, PlamannM (1999) Microscopic analysis of Neurospora ropy mutants defective in nuclear distribution. Fungal Genet Biol 28 : 55–67.

32. KimJM, ZengCJ, NayakT, ShaoR, HuangAC, et al. (2009) Timely septation requires SNAD-dependent spindle pole body localization of the septation initiation network components in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Biol Cell 20 : 2874–2884.

33. RasmussenCG, GlassNL (2005) A Rho-type GTPase, rho-4, is required for septation in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot Cell 4 : 1913–1925.

34. SiH, Justa-SchuchD, SeilerS, HarrisSD (2010) Regulation of septum formation by the Bud3-Rho4 GTPase module in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 185 : 165–176.

35. Justa-SchuchD, HeiligY, RichthammerC, SeilerS (2010) Septum formation is regulated by the RHO4-specific exchange factors BUD3 and RGF3 and by the landmark protein BUD4 in Neurospora crassa. Mol Microbiol 76 : 220–235.

36. SeilerS, PlamannM (2003) The genetic basis of cellular morphogenesis in the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Mol Biol Cell 14 : 4352–4364.

37. YardenO, PlamannM, EbboleDJ, YanofskyC (1992) cot-1, a gene required for hyphal elongation in Neurospora crassa, encodes a protein kinase. EMBO J 11 : 2159–2166.

38. SeilerS, VogtN, ZivC, GorovitsR, YardenO (2006) The STE20/germinal center kinase POD6 interacts with the NDR kinase COT1 and is involved in polar tip extension in Neurospora crassa. Mol Biol Cell 17 : 4080–4092.

39. MaerzS, DettmannA, ZivC, LiuY, ValeriusO, et al. (2009) Two NDR kinase-MOB complexes function as distinct modules during septum formation and tip extension in Neurospora crassa. Mol Microbiol 74 : 707–723.

40. RichthammerC, EnseleitM, Sanchez-LeonE, MarzS, HeiligY, et al. (2012) RHO1 and RHO2 share partially overlapping functions in the regulation of cell wall integrity and hyphal polarity in Neurospora crassa. Mol Microbiol 85 : 716–733.

41. MaerzS, DettmannA, SeilerS (2012) Hydrophobic motif phosphorylation coordinates activity and polar localization of the Neurospora crassa nuclear Dbf2-related kinase COT1. Mol Cell Biol 32 : 2083–2098.

42. DettmannA, IllgenJ, MarzS, SchurgT, FleissnerA, et al. (2012) The NDR kinase scaffold HYM1/MO25 is essential for MAK2 map kinase signaling in Neurospora crassa. PLoS Genet 8: e1002950.

43. HeiligY, SchmittK, SeilerS (2013) Phospho-Regulation of the Neurospora crassa Septation Initiation Network. PLoS One 8: e79464.

44. DanI, WatanabeNM, KusumiA (2001) The Ste20 group kinases as regulators of MAP kinase cascades. Trends Cell Biol 11 : 220–230.

45. HuangTY, MarkleyNA, YoungD (2003) Nak1, an essential germinal center (GC) kinase regulates cell morphology and growth in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Biol Chem 278 : 991–997.

46. NelsonB, KurischkoC, HoreckaJ, ModyM, NairP, et al. (2003) RAM: a conserved signaling network that regulates Ace2p transcriptional activity and polarized morphogenesis. Mol Biol Cell 14 : 3782–3803.

47. GuertinDA, ChangL, IrshadF, GouldKL, McCollumD (2000) The role of the sid1p kinase and cdc14p in regulating the onset of cytokinesis in fission yeast. EMBO J 19 : 1803–1815.

48. GoshimaT, KumeK, KoyanoT, OhyaY, TodaT, et al. (2010) Fission yeast germinal center (GC) kinase Ppk11 interacts with Pmo25 and plays an auxiliary role in concert with the morphogenesis Orb6 network (MOR) in cell morphogenesis. J Biol Chem 285 : 35196–35205.

49. DvashE, Kra-OzG, ZivC, CarmeliS, YardenO (2010) The NDR kinase DBF-2 is involved in regulation of mitosis, conidial development, and glycogen metabolism in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot Cell 9 : 502–513.

50. BerepikiA, LichiusA, ReadND (2011) Actin organization and dynamics in filamentous fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol 9 : 876–887.

51. BalasubramanianMK, SrinivasanR, HuangY, NgKH (2012) Comparing contractile apparatus-driven cytokinesis mechanisms across kingdoms. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 69 : 942–956.

52. Delgado-AlvarezDL, Callejas-NegreteOA, GomezN, FreitagM, RobersonRW, et al. (2010) Visualization of F-actin localization and dynamics with live cell markers in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet Biol 47 : 573–586.

53. Mourino-PérezR (2013) Septum development in filamentous ascomycetes. Fungal Biology Reviews 27 : 1–9.

54. RodrigoG, ElenaSF (2011) Structural discrimination of robustness in transcriptional feedforward loops for pattern formation. PLoS One 6: e16904.

55. JohnsonAE, McCollumD, GouldKL (2012) Polar opposites: Fine-tuning cytokinesis through SIN asymmetry. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 69 : 686–699.

56. StegertMR, HergovichA, TamaskovicR, BichselSJ, HemmingsBA (2005) Regulation of NDR protein kinase by hydrophobic motif phosphorylation mediated by the mammalian Ste20-like kinase MST3. Mol Cell Biol 25 : 11019–11029.

57. JansenJM, BarryMF, YooCK, WeissEL (2006) Phosphoregulation of Cbk1 is critical for RAM network control of transcription and morphogenesis. J Cell Biol 175 : 755–766.

58. ZivC, Kra-OzG, GorovitsR, MarzS, SeilerS, et al. (2009) Cell elongation and branching are regulated by differential phosphorylation states of the nuclear Dbf2-related kinase COT1 in Neurospora crassa. Mol Microbiol 74 : 974–989.

59. EmotoK, ParrishJZ, JanLY, JanYN (2006) The tumour suppressor Hippo acts with the NDR kinases in dendritic tiling and maintenance. Nature 443 : 210–213.

60. HergovichA, HemmingsBA (2009) Mammalian NDR/LATS protein kinases in hippo tumor suppressor signaling. Biofactors 35 : 338–345.

61. VichalkovskiA, GreskoE, CornilsH, HergovichA, SchmitzD, et al. (2008) NDR kinase is activated by RASSF1A/MST1 in response to Fas receptor stimulation and promotes apoptosis. Curr Biol 18 : 1889–1895.

62. McCluskeyK (2003) The Fungal Genetics Stock Center: from molds to molecules. Adv Appl Microbiol 52 : 245–262.

63. FreitagM, HickeyPC, RajuNB, SelkerEU, ReadND (2004) GFP as a tool to analyze the organization, dynamics and function of nuclei and microtubules in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet Biol 41 : 897–910.

64. KawabataT, KatoA, SuzukiK, InoueH (2007) Neurosprora crassa RAD5 homologue, mus-41, inactivation results in higher sensitivity to mutagens but has little effect on PCNA-ubiquitylation in response to UV-irradiation. Curr Genet 52 : 125–135.

65. KawabataT, InoueH (2007) Detection of physical interactions by immunoprecipitation of FLAG - and HA-tagged proteins expressed at the his-3 locus in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genetics Newsletter 54 : 5–8.

66. MaddiA, DettmanA, FuC, SeilerS, FreeSJ (2012) WSC-1 and HAM-7 are MAK-1 MAP kinase pathway sensors required for cell wall integrity and hyphal fusion in Neurospora crassa. PLoS One 7: e42374.

67. MaerzS, FunakoshiY, NegishiY, SuzukiT, SeilerS (2010) The Neurospora peptide:N-glycanase ortholog PNG1 is essential for cell polarity despite its lack of enzymatic activity. J Biol Chem 285 : 2326–2332.

68. DettmannA, HeiligY, LudwigS, SchmittK, IllgenJ, et al. (2013) HAM-2 and HAM-3 are central for the assembly of the Neurospora STRIPAK complex at the nuclear envelope and regulate nuclear accumulation of the MAP kinase MAK-1 in a MAK-2-dependent manner. Mol Microbiol 90 : 796–812.

69. Araujo-PalomaresCL, RichthammerC, SeilerS, Castro-LongoriaE (2011) Functional characterization and cellular dynamics of the CDC-42 - RAC - CDC-24 module in Neurospora crassa. PLoS One 6: e27148.

70. RiquelmeM, BredewegEL, Callejas-NegreteO, RobersonRW, LudwigS, et al. (2014) The Neurospora crassa exocyst complex tethers Spitzenkorper vesicles to the apical plasma membrane during polarized growth. Mol Biol Cell In press: doi:10.1091/mbc.E13-06-0299

71. MillwardTA, HeizmannCW, SchaferBW, HemmingsBA (1998) Calcium regulation of Ndr protein kinase mediated by S100 calcium-binding proteins. EMBO J 17 : 5913–5922.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2014 Číslo 4- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- The Challenges of Mitochondrial Replacement

- Concocting Cholinergy

- Genome-Wide Diet-Gene Interaction Analyses for Risk of Colorectal Cancer

- Statistical Power to Detect Genetic (Co)Variance of Complex Traits Using SNP Data in Unrelated Samples

- Mouse Pulmonary Adenoma Susceptibility 1 Locus Is an Expression QTL Modulating -4A

- Transcription-Associated R-Loop Formation across the Human CGG-Repeat Region

- Epigenetic Regulation by Heritable RNA

- Protein Quantitative Trait Loci Identify Novel Candidates Modulating Cellular Response to Chemotherapy

- Genome-Wide Profiling of Yeast DNA:RNA Hybrid Prone Sites with DRIP-Chip

- The Mechanism of Gene Targeting in Human Somatic Cells

- A LINE-1 Insertion in DLX6 Is Responsible for Cleft Palate and Mandibular Abnormalities in a Canine Model of Pierre Robin Sequence

- Interaction between Two Timing MicroRNAs Controls Trichome Distribution in

- DNA Glycosylases Involved in Base Excision Repair May Be Associated with Cancer Risk in and Mutation Carriers

- The Myc-Mondo/Mad Complexes Integrate Diverse Longevity Signals

- Evolutionarily Diverged Regulation of X-chromosomal Genes as a Primal Event in Mouse Reproductive Isolation

- Mutations in Conserved Residues of the microRNA Argonaute ALG-1 Identify Separable Functions in ALG-1 miRISC Loading and Target Repression

- Genetic Predisposition to In Situ and Invasive Lobular Carcinoma of the Breast

- Isl1 Directly Controls a Cholinergic Neuronal Identity in the Developing Forebrain and Spinal Cord by Forming Cell Type-Specific Complexes

- A Synthetic Community Approach Reveals Plant Genotypes Affecting the Phyllosphere Microbiota

- The Sequence-Specific Transcription Factor c-Jun Targets Cockayne Syndrome Protein B to Regulate Transcription and Chromatin Structure

- Determining the Control Circuitry of Redox Metabolism at the Genome-Scale

- DNA Repair Pathway Selection Caused by Defects in , , and Telomere Addition Generates Specific Chromosomal Rearrangement Signatures

- Methylome Diversification through Changes in DNA Methyltransferase Sequence Specificity

- Folliculin Regulates Ampk-Dependent Autophagy and Metabolic Stress Survival

- Fine Mapping of Dominant -Linked Incompatibility Alleles in Hybrids

- Unexpected Role of the Steroid-Deficiency Protein Ecdysoneless in Pre-mRNA Splicing

- Three Groups of Transposable Elements with Contrasting Copy Number Dynamics and Host Responses in the Maize ( ssp. ) Genome

- Sox5 Functions as a Fate Switch in Medaka Pigment Cell Development

- Synergistic Interactions between the Molecular and Neuronal Circadian Networks Drive Robust Behavioral Circadian Rhythms in

- Chromatin Landscapes of Retroviral and Transposon Integration Profiles

- Widespread Use of Non-productive Alternative Splice Sites in

- Ras GTPase-Like Protein MglA, a Controller of Bacterial Social-Motility in Myxobacteria, Has Evolved to Control Bacterial Predation by

- Cell Type-Specific Functions of Genes Revealed by Novel Adipocyte and Hepatocyte Circadian Clock Models

- Phenotype Ontologies and Cross-Species Analysis for Translational Research

- Embryogenesis Scales Uniformly across Temperature in Developmentally Diverse Species

- In Pursuit of the Gene: An Interview with James Schwartz

- Molecular Mechanisms of Hypoxic Responses via Unique Roles of Ras1, Cdc24 and Ptp3 in a Human Fungal Pathogen

- Analysis of the Genome and Transcriptome of var. Reveals Complex RNA Expression and Microevolution Leading to Virulence Attenuation

- Genotypic and Functional Impact of HIV-1 Adaptation to Its Host Population during the North American Epidemic

- RNA Editome in Rhesus Macaque Shaped by Purifying Selection

- Proper Actin Ring Formation and Septum Constriction Requires Coordinated Regulation of SIN and MOR Pathways through the Germinal Centre Kinase MST-1

- Interplay of the Serine/Threonine-Kinase StkP and the Paralogs DivIVA and GpsB in Pneumococcal Cell Elongation and Division

- A Quality Control Mechanism Coordinates Meiotic Prophase Events to Promote Crossover Assurance

- CNNM2 Mutations Cause Impaired Brain Development and Seizures in Patients with Hypomagnesemia

- The RNA-Binding Protein QKI Suppresses Cancer-Associated Aberrant Splicing

- Uncoupling Transcription from Covalent Histone Modification

- Rad51–Rad52 Mediated Maintenance of Centromeric Chromatin in

- FRA2A Is a CGG Repeat Expansion Associated with Silencing of

- A General Approach for Haplotype Phasing across the Full Spectrum of Relatedness

- A Novel Highly Divergent Protein Family Identified from a Viviparous Insect by RNA-seq Analysis: A Potential Target for Tsetse Fly-Specific Abortifacients

- A Central Role for in Regulation of Islet Function in Man

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- The Sequence-Specific Transcription Factor c-Jun Targets Cockayne Syndrome Protein B to Regulate Transcription and Chromatin Structure

- The Mechanism of Gene Targeting in Human Somatic Cells

- Genetic Predisposition to In Situ and Invasive Lobular Carcinoma of the Breast

- Widespread Use of Non-productive Alternative Splice Sites in

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy