-

Články

- Časopisy

- Kurzy

- Témy

- Kongresy

- Videa

- Podcasty

Uncoupling Transcription from Covalent Histone Modification

The proper regulation of gene expression is of fundamental importance in the maintenance of normal growth and development. Misregulation of genes can lead to such outcomes as cancer, diabetes and neurodegenerative disease. A key step in gene regulation occurs during the transcription of the chromosomal DNA into messenger RNA by the enzyme, RNA polymerase II. Histones are small, positively charged proteins that package genomic DNA into arrays of bead-like particles termed nucleosomes, the principal components of chromatin. Increasing evidence suggests that nucleosomal histones play an active role in regulating transcription, and that this is derived in part from reversible chemical (“covalent”) modifications that take place on their amino acids. These histone modifications create novel surfaces on nucleosomes that can serve as docking sites for other proteins that control a gene's expression state. In this study we present evidence that contrary to the general case, covalent modifications typically associated with transcription are minimally used by genes embedded in a specialized, condensed chromatin structure termed heterochromatin in the model organism baker's yeast. Our observations are significant, for they suggest that gene transcription can occur in a living cell in the virtual absence of covalent modification of the chromatin template.

Published in the journal: Uncoupling Transcription from Covalent Histone Modification. PLoS Genet 10(4): e32767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004202

Category: Research Article

doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004202Summary

The proper regulation of gene expression is of fundamental importance in the maintenance of normal growth and development. Misregulation of genes can lead to such outcomes as cancer, diabetes and neurodegenerative disease. A key step in gene regulation occurs during the transcription of the chromosomal DNA into messenger RNA by the enzyme, RNA polymerase II. Histones are small, positively charged proteins that package genomic DNA into arrays of bead-like particles termed nucleosomes, the principal components of chromatin. Increasing evidence suggests that nucleosomal histones play an active role in regulating transcription, and that this is derived in part from reversible chemical (“covalent”) modifications that take place on their amino acids. These histone modifications create novel surfaces on nucleosomes that can serve as docking sites for other proteins that control a gene's expression state. In this study we present evidence that contrary to the general case, covalent modifications typically associated with transcription are minimally used by genes embedded in a specialized, condensed chromatin structure termed heterochromatin in the model organism baker's yeast. Our observations are significant, for they suggest that gene transcription can occur in a living cell in the virtual absence of covalent modification of the chromatin template.

Introduction

Transcription in eukaryotes occurs in the context of chromatin. At most genes, transcriptional activation is accompanied by alterations to the chromatin template, exemplified by the enhanced DNase I sensitivity of coding regions and the presence of associated DNase I hypersensitive sites at linked regulatory elements [1], [2]. DNase I hypersensitivity of promoter regions primarily arises from the partial or transient occupancy of nucleosomes (i.e., nucleosome depletion) [3], [4], while the enhanced nuclease sensitivity of coding regions arises, in large part, from post-translational modification (PTM) of histones. Lysine acetylation of histones increases the accessibility of DNA wrapped around individual nucleosomes [5], contributes to the decondensation of the 30 nm fiber [6], [7] and facilitates nucleosomal displacement during elongation of RNA polymerase [8].

Covalent histone modifications can also create novel nucleosomal surfaces that serve as recognition sites for effector proteins. Histone PTMs, acting singly or in combination, may therefore control the ultimate expression state of a gene, or the ability of the underlying DNA to be repaired, recombined or replicated. This concept has been termed the histone code [9], [10]. A prime example of this is the inducible INO1 promoter in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae where phosphorylation of the Ser10 residue of H3 (H3S10) by the Snf1 kinase triggers acetylation of the Lys14 residue of H3 (H3K14) by the Gcn5 acetyltransferase, and subsequent transcriptional activation [11]. Likewise, in mammalian cells, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-mediated phosphorylation of H2B S36 has been functionally linked to transcriptional activation of genes responsive to metabolic stress [12]. More recently, the combination of H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) and H4K16 acetylation (H3K16ac) was shown to serve as a high-affinity docking site for the human chromatin remodeling enzyme NURF [13]. Observations such as these have contributed to the widespread idea that histone PTMs play important roles in regulating gene transcription [14], [15].

An alternative view is that histone modifications and the enzymes that impart them are not regulatory; that is, they do not play a causative role in transcription [16]. This arises from the fact that most enzymes that convey histone modifications have no specificity. Moreover, most histone PTMs are short-lived and do not persist in the absence of the proteins that recruit them [16]. Instead, according to this view, histone modifications play other roles. For example, they may assist in the fine-tuning of transcription or in its fidelity. They may also delineate one region of a gene (e.g., promoter) from another (e.g., coding region), as well as from other genetic elements, thereby diversifying the chromatin landscape [17]. Therefore, histone modifications may occur as a consequence, rather than the cause, of dynamic processes such as transcription and nucleosome remodeling [17].

In addition to the precise role(s) played by covalent histone modifications, it is unclear whether the dynamic properties of euchromatin are shared with heterochromatin, the compartment of the nucleus that remains condensed throughout interphase, replicates late, is resistant to recombination, and contains relatively few transcribed genes. In multicellular organisms, heterochromatin can exist in both constitutive and facultative (i.e., regulated) forms. Constitutive heterochromatin is enriched in HP-1 (a structural protein) and SU(VAR)3–9 (an H3K9 methyltransferase) in organisms ranging from fission yeast to mammals, and is characteristic of telomeric and pericentric regions, repetitive DNA elements, and other DNA sequences critical to genomic stability. In contrast, facultative heterochromatin is characteristic of reversibly silenced genes such as X-linked genes in female mammals and genes encoding key developmental regulators, is enriched in H3K27me3 - and ubiquitylated H2A-containing nucleosomes, and is under regulation of Polycomb chromatin modification complexes [18], [19], [20].

Budding yeast, although lacking HP-1 and Polycomb proteins, contains specialized chromatin structures that functionally resemble the Polycomb-regulated facultative heterochromatin of insects and vertebrates [21]. These heterochromatic domains are located at telomeres and the HML and HMR silent mating loci [reviewed in 22], [23]. They are silenced via recruitment of a chromatin modification complex containing the Sir2, Sir3 and Sir4 proteins that horizontally spreads over each telomere or HM locus. Absence of any one of the Sir proteins prevents the assembly of silent chromatin [24], [25], [26]. Sir3 and Sir4 are structural proteins [22] while Sir2 is a NAD+-dependent lysine deacetylase that deacetylates histones with a preference for H4K16 and H3K56 [27]. Sir2/Sir3/Sir4-mediated silent chromatin resembles the heterochromatin of other organisms in several ways: [i] it is repressive to gene transcription; [ii] it is organized into chromosomal domains that silence in a position-specific rather than sequence-specific fashion; [iii] its assembly involves entry sites that nucleate the formation and spread of repressor proteins; and [iv] the repressed expression state is mitotically inherited from mother to daughter cell [reviewed in 21], [28].

While heterochromatin is generally repressive of transcription, hundreds of genes are localized within this nuclear compartment in protozoa, insects, plants and animals. The light gene, and at least eight others in Drosophila, depend on a heterochromatic location for normal expression [reviewed in 29]. Likewise, in placental mammals, expression of the Xist gene is 100-fold enhanced on the heterochromatic, inactive X chromosome relative to its euchromatic counterpart [reviewed in 30]. In trypanosomes, antigenic variation stems from variegated expression of telomere-silenced surface glycoprotein genes, a phenomenon underlying trypanosomiasis (African sleeping sickness) [reviewed in 31]. Despite the importance of heterochromatic genes, the mechanisms underlying their transcriptional activation remain largely unknown. To gain insight into this, we investigated chromatin alterations that accompany heterochromatic gene activation in S. cerevisiae. We found that large increases in the transcription of disparate heterochromatic genes occur in the absence (or near absence) of covalent histone modifications. Strikingly, when the same genes are placed in a euchromatic context, they heavily utilize such modifications.

Results

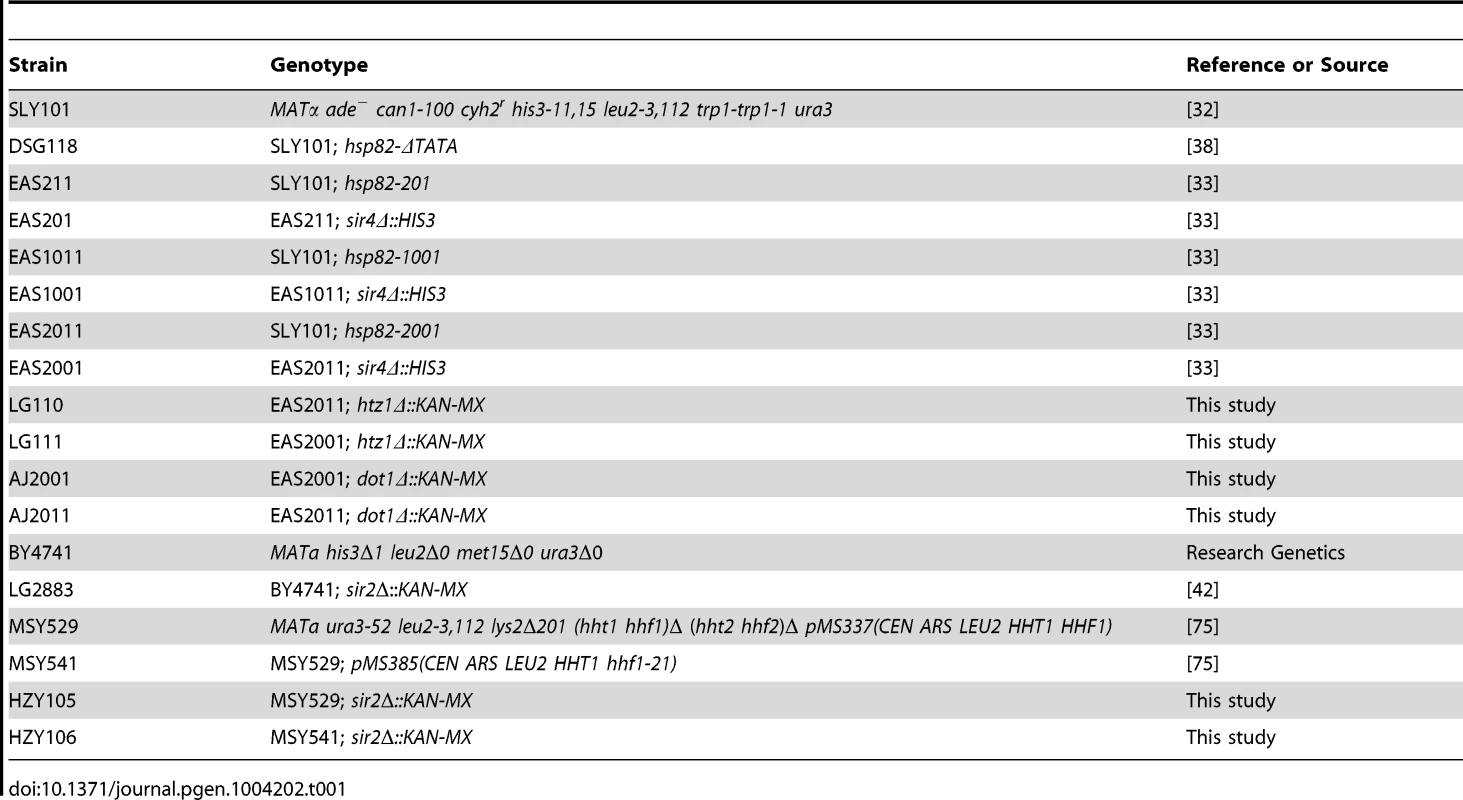

Efficiency of SIR-Dependent Silencing Correlates with Targeted Recruitment and Retention of Sir Proteins

To investigate changes in histone abundance and modification state that take place in activated heterochromatin, we took advantage of a previously described heat shock-inducible transgene system [32], [33]. The system consists of the native HSP82 gene and chromosomal HSP82 alleles flanked by integrated copies of the HMRE mating-type silencer that differ in their dosage and arrangement (illustrated in Figure 1A). As a consequence, the basal transcription of these transgenes is differentially silenced, from 3-fold for hsp82-201 bearing two upstream silencers to 30-fold for hsp82-2001 flanked by tandem silencers (see Figure 1B, left). The transgene termed hsp82-1001, flanked by single silencers, represents an intermediate case and is ∼6-fold silenced.

Fig. 1. SIR-regulated heat shock transgene system.

(a) Summary of hsp82 transgenes used in this study with location, orientation and dosage of integrated HMRE silencers indicated by arrows (see Inset for location of silencer binding proteins ORC, Rap1 and Abf1). Transgenes occupy the native chromosomal HSP82 locus (located ∼95 kb from TEL16L) and contain the indicated silencer insertions with no extraneous DNA sequence (see Materials and Methods). Note that the transcription start site lies 60 bp upstream of the start codon and the 3′ integration site lies ∼50 bp 3′ of the mapped transcription termination site [74]. The ORF is indicated as a black rectangle; coordinates are numbered relative to the ATG codon. (b) Transcriptional output of hsp82 transgenes under non-inducing (30°C) and inducing conditions (20 min heat shock at 39°C). Depicted are bar graph summaries of Northern analyses of SIR+ and sir4Δ cells bearing the indicated hsp82 transgenes (arrows symbolize integrated silencers as in A); HSP82+ was analyzed in the parental strain. Transcript abundance was normalized to ACT1 and is presented relative to the non-induced HSP82+ level set at 100 (depicted are means ± S.D.; N = 2). As expected, Sir proteins occupy the promoter region of each transgene under non-heat-shock (NHS) conditions, and at levels that roughly correlate with the extent of silencing (see Figure 2, panels A and B for a Sir3 ChIP analysis; similar results were previously seen for Sir2 [24]). Sir3 was also observed within the coding regions of hsp82-1001 and hsp82-2001 but not within the ORF of the weakly silenced hsp82-201 gene. Indeed, the domain of silent chromatin at hsp82-1001 and hsp82-2001 spans at least 4 kb based on both ChIP and mRNA expression criteria (Figure S1), closely resembling that seen at the native HMR locus [26], [34]. This observation is consistent with the idea that spread of the Sir2/3/4 complex from its site of recruitment is antagonized by the presence of enhancer and promoter sequences which serve as boundary elements [35], [36].

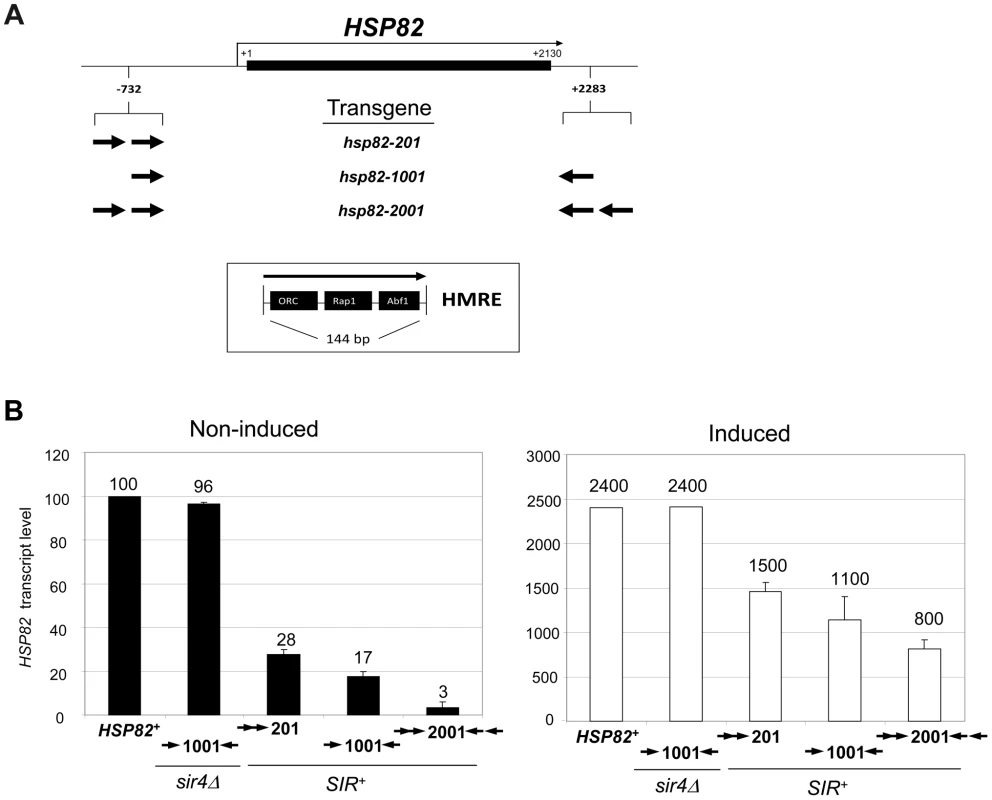

Fig. 2. Retention of the Sir protein complex and increased nucleosome density and stability at the heat shock-induced hsp82-2001 transgene.

(a) In vivo crosslinking analysis of Sir3 at the promoter, ORF and 3′-UTR of hsp82-201, hsp82-1001 and hsp82-2001. Crosslinked chromatin, sheared to a mean size of ∼0.5 kb, was isolated from cells cultivated at 30°C and either maintained at that temperature or subjected to a 20 min 39°C heat shock (HS) (− and +, respectively). Following immunoprecipitation, crosslinks were reversed and purified DNA was subjected to quantitative multiplex PCR in the presence of [α-32P] dATP using primers specific for the five loci indicated. A gel analysis of multiplex PCR products is presented on the left, while a summary of three independent experiments (means ± S.E.) is presented on the right. Input sample (lane 1), derived from strain EAS2011, represents 4% of soluble chromatin used in the corresponding IP (lane 2). In the histogram, Sir3 occupancy at each hsp82 transgene was normalized to its occupancy at HMRa1. prom, promoter. (b) ChIP analysis of Sir3 at hsp82-2001 as in A, except that cells were subjected to the indicated heat shock time course and quantification of Sir3 abundance was performed using Real Time qPCR. Sir3 abundance at the indicated regions was normalized to its occupancy at HMRa2; illustrated are means ± S.D. (N = 2; qPCR = 4). (c) Histone H3 abundance at the promoter, ORF and 3′-UTR of hsp82-2001 in sir4Δ and SIR+ contexts as indicated, normalized to its occupancy at ARS504. Cultures were maintained at 30°C (0 min) or subjected to an instantaneous 39°C upshift for the times indicated. Quantification performed as in B; depicted are means ± S.D.; N = 2, qPCR = 4. In response to a 20 min heat shock (HS), all three transgenes were strongly activated (Figure 1B, right). Notably, despite >200-fold activation, Sir3 occupancy within the hsp82-2001 locus was only slightly reduced (Figure 2, panels A and B), contrasting with the less efficiently silenced transgenes where Sir3 localization was altered through either dispersal or dissociation (Figures 2A and S1A, compare HS (+) samples with NHS (−)). Thus, transcriptional activation of the most efficiently silenced transgene occurred with minimal loss of the Sir2/3/4 complex at either promoter or coding region, consistent with earlier observations of the hsp82-2001 promoter and recent observations of an activated subtelomeric URA3 gene [24], [37].

Disruption of silent chromatin through SIR4 deletion restored transcript levels of each transgene to WT levels (Figure 1B, hsp82-1001 sir4Δ strain and data not shown). This indicates that cis-acting HMRE silencers (and the sequence-specific proteins bound to them) do not affect HSP82 regulation; assembly of the Sir protein complex is required. Consistent with this, the promoter chromatin structure of the three transgenes in a sir4Δ background is indistinguishable from the euchromatic HSP82 gene, based on nucleotide-resolution DNase I, MNase and dimethyl sulfate genomic footprint analyses [33].

Nucleosomal Density Is Increased across the Hyperrepressed hsp82-2001 Transgene and Heat Shock-Induced Histone Eviction Is Suppressed

We next investigated the effect of the Sir proteins on nucleosome density and stability. As previously seen for wild-type HSP82 [38], histone H3 was rapidly depleted in response to heat shock of the euchromatic hsp82-2001 gene, exhibiting a 75% reduction within 60 sec and >90% reduction within 5 min (Figure 2C, sir4Δ samples). Consistent with diminished transcriptional activity during chronic heat shock [39], [40], H3 levels were partially restored between 2 and 24 hr. Assembly of HSP82 into heterochromatin not only resulted in at least a twofold increase in nucleosomal density throughout the gene (compare SIR+ with sir4Δ cells, 0 min), but also restricted the dynamic nature of the chromatin as the extent of nucleosomal disassembly was substantially reduced. Virtually identical results were seen when abundance of either myc-H4 or H2A was evaluated (data not shown); therefore, large (>200-fold) increases in expression can take place in the context of relatively modest changes in nucleosome occupancy, consistent with the retention of the Sir2/3/4 complex described above.

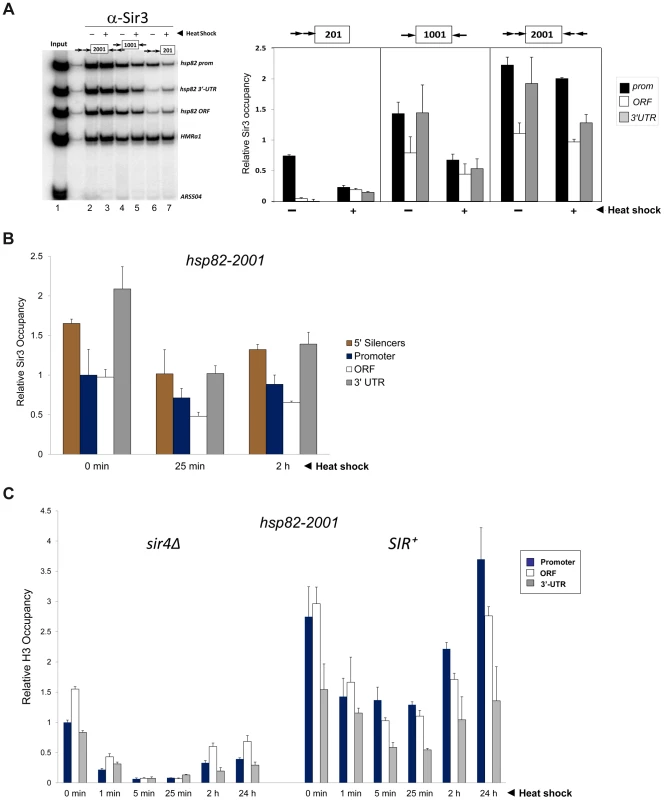

The Transcriptional Machinery Dynamically Associates with Heterochromatic hsp82-2001

Given the relatively static state of the chromatin, we next asked whether inducible occupancy of the Pol II transcriptional machinery could be detected at the heterochromatic hsp82-2001 transgene. Consistent with earlier observations of SIR-silenced genes [24], [41], [42], [43] and reconstituted SIR-heterochromatin [44], Pol II was detectable within the promoter region of non-induced hsp82-2001, albeit at a reduced level (Figure 3A, SIR+, 0 min). Importantly, its occupancy was substantially enhanced (10 - to 15-fold) by heat shock. We additionally examined occupancy of the capping enzyme Cet1. Previous analysis of the HMLα1/α2 and HMRa1 silent mating genes indicated that occupancy of Cet1 was strongly restricted under SIR-silencing conditions [42], consistent with the notion that SIR elicits silencing, at least in part, by targeting steps downstream of PIC assembly. In support, we found that under non-inducing conditions Cet1 was at near-background levels at all three heterochromatic hsp82 transgenes (Figure 3B). This restriction was dramatically overridden by heat shock, which resulted in a >30-fold increase in Cet1 occupancy of the 5′-end of hsp82-2001 and similar increases within the 5′-ends of hsp82-201 and hsp82-1001. Therefore, at least two components of the basic transcriptional machinery, Pol II and Cet1, dynamically occupy the hyperrepressed hsp82-2001 transgene in response to heat shock, in contrast to either histones or Sir proteins.

Fig. 3. Components of the transcriptional machinery are dynamically recruited to activated heterochromatic genes.

(a) ChIP-qPCR analysis of Pol II occupancy at the promoter, ORF and 3′-UTR of the hsp82-2001 gene in sir4Δ and SIR+ cells heat shocked for the indicated times. All values represent net ChIP signals (immune – pre-immune serum) at hsp82-2001 normalized to those at ARS504. Pol II occupancy at the euchromatic hsp82-2001 promoter was set to 1.0; all other occupancies are scaled relative to this. (b) ChIP analysis of Cet1 occupancy of hsp82-201, hsp82-1001 and hsp82-2001 under NHS (−) and 20 min HS (+) conditions, conducted as in Figure 2A. Left, gel analysis. Input sample (lane 1) represents 0.4% of soluble chromatin used in each IP. Mock, chromatin reacted with beads alone. Lanes 3–10, chromatin isolated from SIR+ and sir4Δ strains as indicated (+ and −, respectively) and immunoprecipitated with a Cet1-specific antibody. Histogram represents net mean values (immune signal minus beads alone) of three independent experiments. SIR Severely Reduces H3 and H4 N-Terminal Acetylation upon Transcriptional Activation

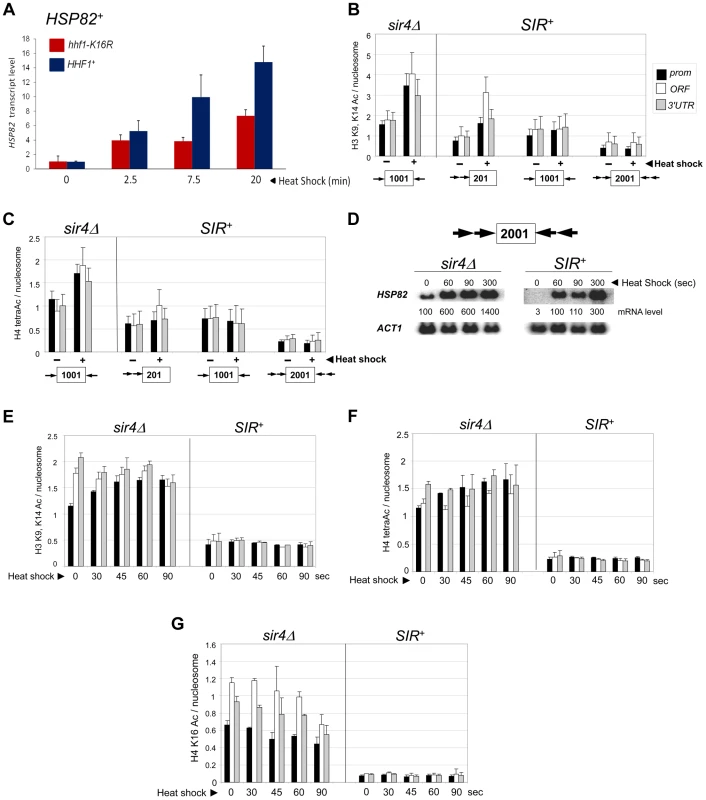

Previous work has shown that euchromatic hsp82 alleles are dependent on the histone acetyltransferases Gcn5 and Esa1 for normal transcriptional activation [45]. Consistent with this, we found that HSP82+ activation was impaired in an H4 K16R mutant (Figure 4A). We therefore asked whether acetylation of histones H3 and H4, a hallmark of gene activation [14], [46], [47], accompanies induction of the hsp82 transgenes. As shown in Figures 4B and 4C, nucleosomes occupying the euchromatic hsp82 transgene (sir4Δ cells) were both H3 di-acetylated and H4 tetra-acetylated under NHS (−) conditions, mimicking the wild-type HSP82 gene [38]. By contrast, nucleosomes within the SIR-silenced hsp82-2001 gene were negligibly acetylated under the same conditions. Thus, hsp82-2001 conforms to the general notion of a histone code, in which absence of N-tail histone acetylation codes for inactivation. The less efficiently silenced transgenes were also impoverished in both di-acetylated H3 and tetra-acetylated H4, but to a lesser degree. Notably, upon heat shock (+), the euchromatic transgene was enriched in both acetylated isoforms (once again resembling HSP82+) yet there was no detectable enrichment of either at the hyperrepressed hsp82-2001 gene. Similarly, the moderately silenced hsp82-1001 transgene, despite >60-fold increase in expression in response to heat shock, showed no enrichment in acetylation. By contrast, the weakly silenced hsp82-201 gene was H3 hyperacetylated, resembling its euchromatic counterpart.

Fig. 4. Heterochromatic gene activation occurs in the context of negligible H3 and H4 acetylation.

(a) Induced transcription of the wild-type HSP82 gene is impaired by an H4 K16R mutation. Transcript abundance was assayed in isogenic HHF1+ and hhf1-K16R cells subjected to a 30° to 39°C temperature shift for the indicated times. Total RNA was isolated, cDNA synthesized, and HSP82 levels were quantified by RT-qPCR followed by normalization to SCR1. Quotients were scaled to the non-induced HHF1+ sample which was set to 1. Depicted are means ± S.D. (N = 2; qPCR = 4). (b) ChIP analysis of H3 diacetylated at K9, K14 at the indicated hsp82 transgenes in sir4Δ or SIR+ cells cultivated under NHS (−) or 20 min HS (+) conditions using multiplex PCR as in Figure 2A. Shown are quotients of diacetylated H3 signal divided by Myc-H4 signal (means ± S.E.; N = 3). Occupancies of acetylated H3 and Myc-H4 at the hsp82 transgenes were normalized to their respective occupancies at PHO5. (c) As in B, except that a ChIP analysis of tetra-acetylated H4 is depicted. (d) Northern analysis of hsp82-2001 in sir4Δ or SIR+ cells subjected to an instantaneous 30° to 39°C thermal upshift for the times indicated. HSP82 mRNA levels, normalized to those of ACT1, were quantified for each time point (values represent means of two independent experiments). (e) H3 K9ac,K14ac ChIP analysis of hsp82-2001 in sir4Δ or SIR+ cells for the indicated times following instantaneous heat shock. Depicted are diacetylated H3/Myc-H4 quotients quantified as in B. (f) Tetra-acetylated H4 ChIP analysis of hsp82-2001 as in E. (g) H4K16ac ChIP analysis of hsp82-2001 as in E. The foregoing analysis indicates that the minimal acetylation state of heterochromatic hsp82-2001 remains unaltered following a 20 min heat shock. However, as transcript accumulation is evident within the first 60 sec (see Figure 4D, SIR+ samples), it was possible that transient histone acetylation may have occurred. To address this, we assayed H3 and H4 acetylation of hsp82-2001 30 sec following an instantaneous heat shock, and at 15 - to 30-sec intervals thereafter, to obtain ‘snapshots’ of the H3/H4 acetylation state within this gene. Despite a 30-fold increase in hsp82 transcript level within the first 60–90 sec of heat shock, neither di-acetylated H3 nor tetra-acetylated H4 was detectably increased (Figures 4E and 4F; SIR+ background). This again contrasts with the euchromatic state where promoter-associated nucleosomes, already enriched in acetylated H3 and H4 molecules, showed a further ∼30% increase.

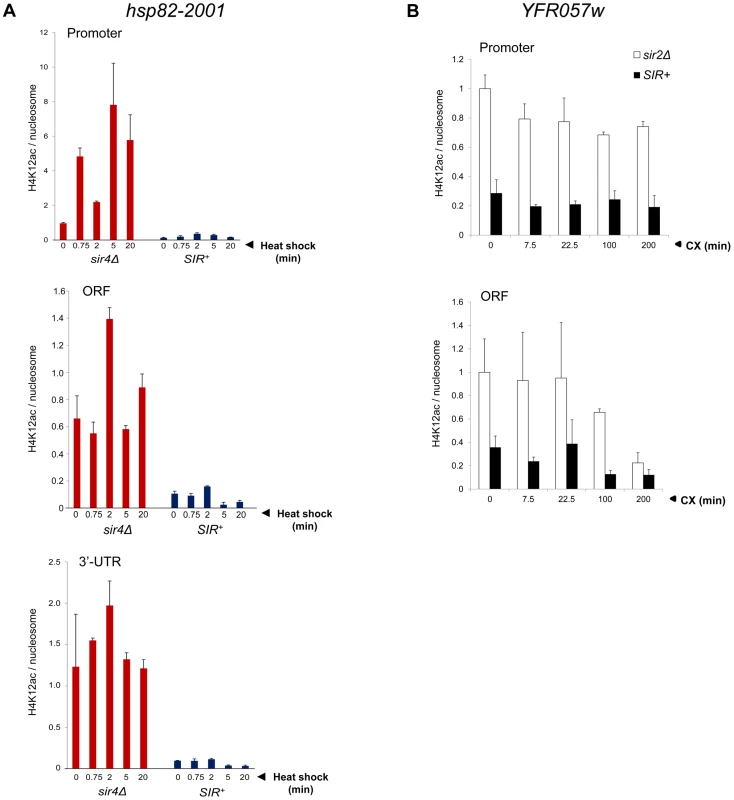

We separately examined H4K16 acetylation, given that this modification is sufficient to inhibit formation of the compact 30 nm fiber in vitro [7], and as previously mentioned, is a preferred Sir2 target. As above, there was no increase in H4K16 acetylation, even transiently, as this modification remained at background levels throughout the heat shock (Figure 4G, SIR+). This finding suggests that Sir2 may actively deacetylate H4K16 to suppress the extent of chromatin unfolding and, as a consequence, diminish gross transcriptional output. We also examined H4K12 acetylation, which has been implicated in telomeric heterochromatin formation and function in S. cerevisiae [48]. However, in contrast to euchromatic hsp82-2001, the hyperrepressed hsp82-2001 transgene was assembled in nucleosomes containing only background levels of H4K12ac, with little if any enrichment upon heat shock (Figure 5A). Thus, its role may be telomere-specific (see below).

Fig. 5. Activation of heterochromatic genes occurs in the context of negligible H4K12 acetylation.

(a) H4K12ac enrichment at hsp82-2001 subjected to heat shock for the indicated times. H4K12Ac and H3 ChIP signals were quantified at promoter, ORF and 3′-UTR using Real Time qPCR and normalized to those measured at PMA1 and ARS504 (for H4K12ac and H3, respectively). H4K12ac/H3 quotients were then determined and scaled to the non-induced promoter signal in sir4Δ cells, which was set to 1. Depicted are means ± S.D (N = 2; qPCR = 4). (b) H4K12ac enrichment at YFR057W promoter and ORF at the indicated times following addition of 200 µg/ml cycloheximide. Quantification was performed as in A. Activating H3K56ac and H3K36me3 Marks Are Strongly Suppressed during Heterochromatic Gene Induction

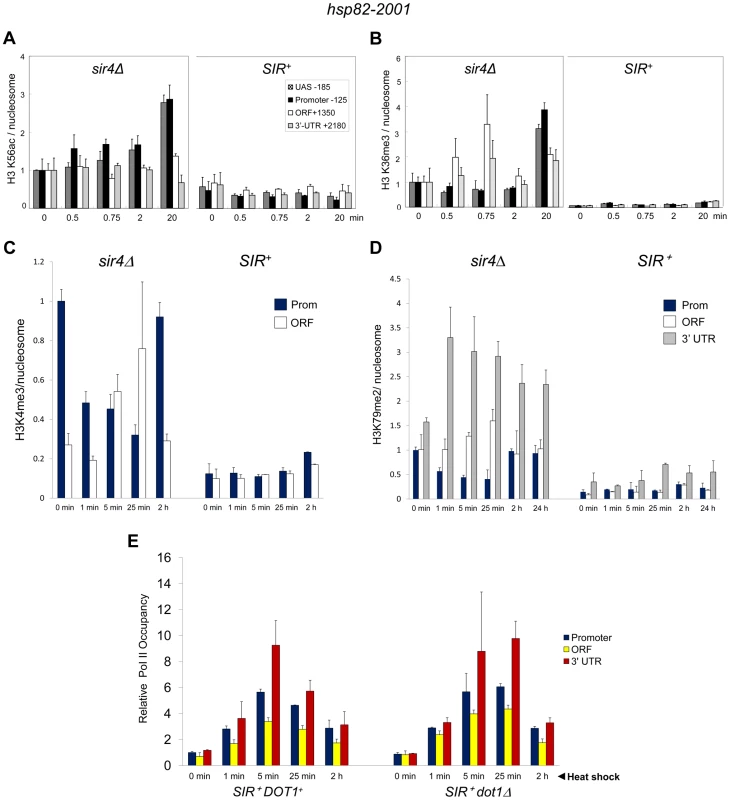

Since the above results argue that heterochromatic transcription is uncoupled from histone N-terminal lysine acetylation, we asked whether acetylation of K56, located within the globular core of H3, or methylation of K36, located at the junction between the H3 N-terminus and the globular domain, accompanies transcriptional activation. H3K56 acetylation is predicted to break a histone-DNA interaction, potentially destabilizing the nucleosome [49] and is a mark of Pol II elongation due to histone exchange [50]. Indeed, there exists a tight linkage between H3K56 acetylation and nucleosomal disassembly in vivo [51]. H3K56 acetylation is of additional interest, given that it is a target of Sir2, and its deacetylation is important in the compaction of telomeric silent chromatin and concomitant repression of transcription [27]. SIR reduced H3K56ac levels at non-induced hsp82-2001 ∼2-fold (Figure 6A). More strikingly, H3K56ac enrichment remained low following a 20 min heat shock time course, when transcript accumulation increased >200-fold. This static modification state contrasts with the euchromatic hsp82 gene where the already elevated H3K56ac levels exhibited a further 2.5 to 3-fold increase at both UAS and promoter regions (Figure 6A, sir4Δ).

Fig. 6. Heterochromatic gene activation occurs in the context of minimal transcription-linked H3 methylation and is unimpaired by ablation of Dot1.

(a) H3K56ac ChIP analysis of hsp82-2001 in sir4Δ or SIR+ cells subjected to an instantaneous 30° to 39°C thermal upshift for the times indicated. Quantification was done using Real Time qPCR. The acetylated H3K56/Myc-H4 quotient of the non-induced sir4Δ sample was set to 1.0 for each amplicon. PTM-specific and Myc-H4 signals at the heat shock transgene were normalized to those measured at PMA1 and ARS504, respectively. Shown are means ± S.D. (N = 2; qPCR = 4). (b) H3K36me3 ChIP analysis of hsp82-2001 conducted as in A. (c) H3K4me3 ChIP analysis of hsp82-2001 in sir4Δ or SIR+ cells subjected to an instantaneous 30° to 39°C thermal upshift for the times indicated. Quantification and scaling were done as in A, except H3K4me3/H3 quotients are depicted, and both PTM-specific and H3 signals were normalized to those measured at ARS504. Shown are means ± S.D. (N = 2; qPCR = 4). (d) H3K79me2 ChIP analysis of hsp82-2001 in sir4Δ or SIR+ cells as in C. (e) Pol II ChIP analysis of heterochromatic hsp82-2001 in DOT1+ and dot1Δ strains subjected to heat shock as above. Pol II occupancy was determined using ChIP-qPCR as in Figure 3A. Shown are means ± S.D. (N = 2; qPCR = 4). H3K36me3 is a hallmark of Pol II elongation within gene coding regions [52]. Despite this, robust transcriptional activation of hsp82-2001 takes place in the context of minimal H3K36 trimethylation (<5% of that seen in euchromatin; Figure 6B). Thus, similar to H3K56 acetylation, H3K36 methylation is largely suppressed during heterochromatic gene activation.

H3K4 and H3K79 Methyl Marks Are Likewise Efficiently Suppressed by SIR

We next addressed the role of H3 methylation at lysines 4 and 79. H3K4 trimethylation is a broadly conserved covalent modification of active (or potentially active) gene promoters [52] where it can promote transcription by serving as a recognition site for a number of transcriptional co-regulators such as TFIID, SAGA and NuA3 [53]. Di-methylation of H3K79, located within the globular core of H3, is also linked with activation [54] and its presence correlates with enhanced access of transcription factors to chromatin [55]. Consistent with roles in expression, the euchromatic hsp82 gene is heavily modified with both methyl marks – H3K4me3 particularly within the promoter region and H3K79me2 particularly within the 3′-transcribed region (Figure 6, panels C and D). Strikingly, SIR strongly suppressed both H3K4me3 and H3K79me2 enrichment within the hsp82-2001 transgene throughout a heat shock time course. Moreover, deletion of DOT1, which encodes the sole H3K79 methyltransferase in S. cerevisiae, had virtually no effect on either Pol II recruitment kinetics or occupancy levels throughout the hsp82-2001 gene (Figure 6E). This indicates that H3K79 methylation is unnecessary for robust activation of heterochromatic hsp82-2001, in contrast to observations of a telomeric URA3 gene which suggested that H3K79me1 and H3K79me2 are important in disrupting transcriptional silencing [37] (see Discussion). These results, together with those described above, argue that a substantial increase in transcription can take place in the context of heightened nucleosomal density and minimal covalent histone modification.

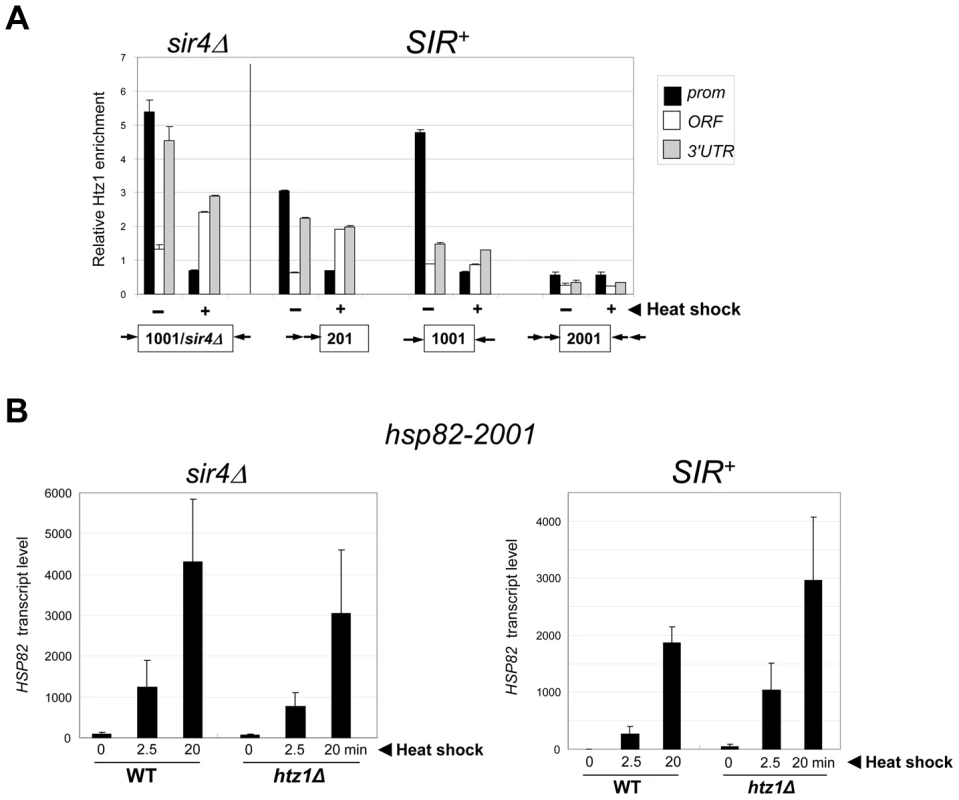

The Histone Variant H2A.Z Is Dispensable for Activation within Silent Chromatin

We next examined the role of the histone variant H2A.Z (Htz1 in S. cerevisiae). Replacement of canonical H2A with H2A.Z at the +1 and or −1 nucleosome poises promoters for transcriptional activation as H2A.Z-containing nucleosomes are more susceptible to disassembly than canonical nucleosomes [56], [57]. ChIP analysis revealed that H2A.Z is enriched within the euchromatic hsp82 promoter, consistent with prior findings [56], and is preferentially evicted upon heat shock (Figure 7A, hsp82-1001 sir4Δ, black bars). As expected, H2A.Z abundance was reduced at the SIR-repressed transgenes. At hsp82-201, its abundance was reduced 40% at the promoter, while at hsp82-1001, H2A.Z levels were altered only at the 3′-end. At both genes, promoter-associated H2A.Z was drastically reduced concomitant with transcriptional induction (Figure 7A, (+) samples). Therefore, the promoter regions of these partially silenced transgenes, like their euchromatic counterparts, are assembled into H2A.Z-containing nucleosomes that are preferentially displaced in response to heat shock. In contrast, the hyperrepressed hsp82-2001 gene is nearly bereft of H2A.Z in non-induced cells (∼90% reduced within both promoter and coding region) and this reduced level remained unchanged during activation. Consistent with this observation, deletion of the gene encoding H2A.Z did not impair hsp82-2001 mRNA induction, and may have even enhanced it (Figure 7B, SIR+ htz1Δ samples).

Fig. 7. Activation of heterochromatic hsp82-2001 occurs in the presence of minimal H2A.Z levels and is unimpaired by deletion of HTZ1.

(a) ChIP analysis of H2A.Z at the indicated hsp82 alleles under NHS (−) and 20 min HS (+) conditions conducted as in Figure 4B, with H2A.Z content normalized per nucleosome (Myc-H4 abundance). Shown are means ± S.D. (N = 2). (b) hsp82-2001 transcript abundance was determined in WT and htz1Δ cells (sir4Δ and SIR+ as indicated) subjected to heat shock for the indicated periods of time. RNA was isolated, cDNA synthesized and HSP82 transcripts were quantified using RT-qPCR and normalized to SCR1 as in Figure 4A. Depicted are means ± S.D. (N = 2; qPCR = 4). Euchromatic hsp82-ΔTATA Undergoes Substantial Chromatin Modification in Response to Heat Shock

It could be argued that the near-absence of covalent histone modification at hsp82-2001 is a consequence of its lower transcriptional output relative to wild-type HSP82. To address this possibility, we used an attenuated euchromatic hsp82 allele, hsp82-ΔTATA, that bears a 19 bp chromosomal substitution of the TATA box and surrounding region [38]. This mutation resulted in a 10-fold reduction in 20 min heat shock-induced transcript levels (Figure 8A). By comparison, silent chromatin diminished the activated expression of hsp82-2001 only 2 - to 3-fold (e.g., see Figures 1B, 7B). If absence of histone PTMs and other chromatin alterations stem from diminished gross transcriptional output, then it would be predicted that hsp82-ΔTATA chromatin would not be modified upon its activation. However, heat shock-activated hsp82-ΔTATA undergoes H4 displacement and substantial H3 acetylation. H4 depletion within the UAS/promoter of hsp82-ΔTATA was both rapid and extensive, closely resembling wild-type HSP82, although there was little histone loss over the coding region (Figure 8B), consistent with diminished expression. Moreover, acetylation of H3K18, which is catalyzed by SAGA [58] and strongly correlates with transcriptional activation in euchromatin [59], was particularly prominent within the UAS/promoter region of hsp82-ΔTATA (Figure 8D). By contrast, the upstream region of heterochromatic hsp82-2001 was negligibly modified at H3K18 and with delayed kinetics (Figure 8F; note difference in scale), whereas H3K18 acetylation at euchromatic hsp82-2001 resembled HSP82+ (compare Figures 8C and 8E). These results argue that the Hsf1-activated heterochromatic hsp82-2001 gene is transcribed at a sufficiently high level to undergo nucleosomal disassembly and significant H3 acetylation over its promoter-proximal region, yet does not do so.

Fig. 8. Euchromatic hsp82-ΔTATA undergoes nucleosomal disassembly and H3 hyperacetylation within its 5′-regulatory region.

(a) Expression analysis of isogenic strains bearing either HSP82 or hsp82-ΔTATA (SLY101 background) and subjected to a heat shock time course for the indicated times. hsp82 transcript levels were quantified and normalized as in Figure 4A (N = 2; qPCR = 4). (b) Summary of Myc-H4 occupancy at the indicated regions within HSP82 and hsp82-ΔTATA, normalized to its occupancy at ARS504. Quantification was done as in Figure 2C (N = 2; qPCR = 4). (c) H3K18 acetylation analysis of HSP82 over a 20 min heat shock time course as in Figure 5A (means ± S.D.; N = 2; qPCR = 4). (d) H3K18ac analysis of hsp82-ΔTATA, performed as in C. (e) H3K18ac analysis of euchromatic hsp82-2001 (sir4Δ cells). (f) H3K18ac analysis of heterochromatic hsp82-2001 (SIR+ cells) (note difference in scale). Transcriptional Activation of a Natural Subtelomeric Gene Likewise Occurs with Minimal Histone Modification

The foregoing results indicate that transcriptional activation of heterochromatic hsp82 can occur largely in the absence of nucleosomal modifications that are characteristic of euchromatic genes. While a SIR-dependent chromatin structure is present at hsp82-2001 that, by several criteria, resembles the silent chromatin established at the natively silenced HM loci (Figures 2 and S1A) [24], [33], it is possible that the absence (or near-absence) of activating histone modifications is unique to Hsf1-regulated genes. Indeed, retention of epigenetic information at yeast heat shock genes may not be critical given the extent of histone loss that occurs within both regulatory and coding regions upon their activation (Figure 2C) [38], [60].

To rule out an Hsf1-specific effect, we asked whether a natural subtelomeric gene could be activated in the absence of covalent histone modification and other chromatin alterations. Previous work has shown that the Sir2/3/4 complex extends ∼3 kb from the right telomere of chromosome VI [61], and that expression of the subtelomeric gene, YFR057w, located ∼1 kb from the chromosomal tip, is under SIR regulation [62]. RT-qPCR demonstrates that this gene is efficiently silenced by SIR (>100-fold; Figure 9A, 0 min). While the function of YFR057w is unknown, we reasoned that it might play a role in pleiotropic drug resistance due to the presence of a consensus DNA sequence for Stb5 (www.yeastract.com), which forms a heterodimer with Pdr1. Pdr1 is known to activate other genes involved in pleiotropic drug resistance [e.g., 63]. Consistent with this idea, we found that heterochromatic YFR057w was strongly induced by exposure of cells to 200 µg/ml cycloheximide (Figure 9A, black bars). Notably, euchromatic targets of Pdr1 such as PDR5 and SNQ2 were also induced by this novel regimen (data not shown), one in which cells remained fully viable (see Figure S2).

Fig. 9. Transcriptional activation of the subtelomeric YFR057w gene is unlinked to covalent histone modification.

(a) YFR057w mRNA levels in SIR+ and sir2Δ cells (BY4741 background) exposed to 200 µg/ml cycloheximide (CX) for the indicated times. YFR057w transcripts were quantified by RT-qPCR, and normalized to those of SCR1. Depicted are means ± S.D. (N = 3; qPCR = 6). (b) ChIP-qPCR analysis of Pol II within the YFR057w promoter and ORF in sir2Δ and SIR+ cells exposed to cycloheximide for the indicated times as in A. Pol II occupancy was determined as in Figure 3A. Occupancy of the non-induced promoter (sir2Δ) was set to 1.0; all other occupancies (both promoter and ORF) are scaled relative to it. Depicted are means ± S.D. (N = 4; qPCR = 8). (c) ChIP-qPCR analysis of histone PTMs within the YFR057w promoter (H3K18ac, H4K16ac, H3K4me2,3) or ORF (H3K79me2) in sir2Δ and SIR+ cells exposed for the indicated times to cycloheximide as in A. Shown are normalized PTM/histone H3 quotients. PTM-specific and H3 signals at YFR057w were normalized to those measured at PMA1 and ARS504, respectively. The PTM/histone H3 quotient of the non-induced sir2Δ sample was set to 1.0 in each case. Depicted are means ± S.D. (N = 2; qPCR = 4). (d) ChIP-qPCR analysis of H3K36me3 enrichment within the ORF and Htz1 enrichment within the promoter as in C, for the indicated times following addition of cycloheximide (N = 2; qPCR = 4). (e) As in D, except H3K56ac enrichment over YFR057w promoter and ORF was assayed. The substantial increase in YFR057w transcript abundance in the SIR+ strain (∼150-fold during first 50 min) is unlikely to be a primary consequence of cycloheximide-mediated mRNA stabilization [64] given that its isogenic sir2Δ counterpart showed just a several-fold increase over the same time frame (Figure 9A, white bars). Consistent with bona fide transcriptional induction, Pol II occupancy of the promoter and ORF markedly increased over the cycloheximide time course in both euchromatic and heterochromatic contexts (Figure 9B). The presence of Pol II at the non-induced heterochromatic promoter is consistent with H3 ChIP-Seq data indicating the presence of a 60–80 bp nucleosome-free region upstream of the +1 nucleosome [65].

These striking observations permitted us to ask whether activation of YFR057w takes place in the presence of covalent histone modifications, as is the case for euchromatic genes, or in their absence, as is the case for the comparably repressed hsp82-2001 transgene. We found that induction of heterochromatic YFR057w occurred without histone displacement (Figure S3, A and B, black bars) and in the context of minimal nucleosomal alterations including H3K18 and H4K16 acetylation (<5% the level seen at the euchromatic gene (sir2Δ; Figures 9C and S3C); H3K4me2,3 and H3K79me2 (<5% of sir2Δ context; Figure 9C); H3K36me3 and H2A.Z deposition (20–40% of that seen in a sir2Δ context; Figure 9D); and H3K56 acetylation (10–30% of that seen at the euchromatic gene with no detectable enrichment following induction; Figure 9E). Minimal H3K56ac at YFR057w is consistent with foregoing results with heterochromatic hsp82-2001, which maintained a low level of H3K56ac and a comparatively high nucleosomal density during its activation, although it is unlike observations of a SIR-silenced HMRE-GAL10 transgene that suggested acetylation of this lysine is needed for Pol II elongation [43].

Finally, as mentioned above, H4K12 acetylation has been observed at telomeric heterochromatin in S. cerevisiae, where it has been implicated in several telomere-related processes including replication, recombination and basal transcription [48]. Indeed, we observed an enrichment of H4K12ac at heterochromatic YFR057w relative to other acetylation marks (20–40% of that seen at the euchromatic gene; Figure 5B). Nonetheless, H4K12ac levels remained low in response to cycloheximide induction, a circumstance in which YFR057w transcript levels increased several hundred-fold. This, coupled with the fact that heterochromatic hsp82-2001 contained only background levels of H4K12 acetylation (Figure 5A), argues that this PTM is unlikely to play an important role in heterochromatic gene activation. We conclude that activation of the subtelomeric YFR057w gene, like that of hsp82-2001, takes place in the context of minimal chromatin modification.

Discussion

The Hypoacetylated, Hypomethylated and Nucleosome-Rich Landscape of Activated Silent Chromatin

A widespread belief in the transcription/chromatin field is that covalent modification of nucleosomal histones is integral to the mechanism by which eukaryotes regulate gene expression [5], [9]–[15], [37], [43], [45], [47]–[49], [66]. Results presented here demonstrate that in contrast to this notion, histone modification of activated heterochromatic genes in the model eukaryote S. cerevisiae is minimal, and in certain instances undetectable, despite robust induction (>200-fold over the basal silent state) and dynamic occupancy of the transcriptional machinery. Activation with minimal chromatin modification is observed at genes regulated by disparate activators and is seen in distinct genetic backgrounds. It is not the consequence of insubstantial transcription, since the euchromatic gene, hsp82-ΔTATA, despite being expressed at a level of only 20–30% of heterochromatic hsp82-2001, exhibits striking chromatin modification during its activation including promoter-proximal H3 hyperacetylation and histone displacement. Moreover, at least in the case of HSP82, it is not due to a lack of a requirement for covalent histone modifications. Previous work has shown a clear dependence of euchromatic hsp82 alleles on the histone acetylases Gcn5 and Esa1 present in SAGA and NuA4, respectively [45]. Consistent with this, both HSP82 and hsp82-ΔTATA are extensively acetylated upon heat shock activation and HSP82 expression is reduced in an H4 N-terminal tail mutant. A similar requirement for histone acetylation likely applies to the euchromatic YFR057w gene as its expression is reduced in an H4K16R mutant (Figure S4).

The work presented here significantly extends earlier observations of the absence of tetra-acetylated H4 enrichment following heat shock activation of the hsp82-2001 transgene [24] in many ways. These include analysis of the coding region of this and other heat shock transgenes, analysis of multiple covalent histone modifications typically linked to gene activation, and most significantly extending the finding to a natural heterochromatic gene, YFR057w, whose inducibility was heretofore unknown and whose activation is unlikely to be under the control of Hsf1. It also substantially extends recent observations of a telomere-linked URA3 gene that like HSP82 is able to activate in absence of H3 and H4 acetylation [37] (see below).

It is possible that absence of detectable covalent marks is a consequence of their transience. We examined histone PTMs at multiple time points during the transcriptional induction of two unrelated genes, including time points spaced as tightly as 15 sec apart, and could find no compelling evidence for their presence. Nonetheless, our experiments cannot rule out the presence of covalent histone modifications that are erased (or occluded, for example, by “reader” molecules) moments after they appear. However, our inability to detect PTMs is unlikely to be due to masking of stable modifications. We utilized antibodies specific to multiple epitopes within the histone octamer – globular domain of H3, N-terminal epitope of Myc-H4, acidic patch of H2A – and all were readily detectable in SIR-mediated heterochromatin.

In addition to the absence of covalent histone modification, the heterochromatic hsp82-2001 gene is only partially and transiently depleted of the H3/H4 tetramer during heat shock. This is in contrast to euchromatic hsp82-2001 that sustains a >90% loss of H2A, H3 and H4 during the early stages (5–25 min) of heat shock induction (Figure 2 and data not shown). Interestingly, even under maximally inducing conditions, the density of H3 and H4 at heterochromatic hsp82-2001 equals or exceeds its density at the non-induced euchromatic transgene. The continued presence of the Sir complex during heat-induced activation is likely crucial for suppression of both histone loss and covalent histone modifications. Regarding PTMs, in the case of H3/H4 acetylation, the Sir2 deacetylase apparently “wins” the competition with the SAGA and NuA4 acetylases for the chromatin template. Why H3 methylation does not occur is less clear, and is the subject of ongoing investigation.

It is possible that the minimal changes in histone modification state that are detected at silent hsp82-2001 and YFR057w are sufficient to serve as novel surfaces to which bromodomain-, chromodomain - and PHD-domain-containing regulatory complexes may bind. We believe that this is unlikely, even in the extreme case in which it is assumed that the euchromatic counterparts of these genes are saturated with acetylated or methylated histone isoforms at their maximum point of enrichment. Since in most cases there is a >10-fold difference in modification levels in euchromatic (sir2Δ or sir4Δ) versus heterochromatic (SIR+) states, modification of the heterochromatic gene is maximally one PTM (of a given type) for every 5–10 nucleosomes. Since the upstream regulatory region of HSP82 spans only two nucleosomes [67], [68], this means that <1 PTM of a specific type is present within the heterochromatic hsp82-2001 promoter. This, combined with the fact that there is no evidence for epigenetic variegation of hsp82-2001 expression (at least when tested under non-inducing conditions [24]), argues against the existence of a subpopulation of cells enriched for activating histone marks and disproportionately contributing to the HSP82 transcript measured in our assays. Instead, our results suggest a dominant role for gene-specific activators (Hsf1 in the case of hsp82-2001 and Pdr1/Stb5 in the case of YFR057w) in recruiting transcriptional co-regulators [69] that disrupt SIR-mediated silencing.

Our findings also provide an interesting contrast to those of Grunstein, Carey and coworkers [37]. These workers examined the chromatin properties of a telomere-linked URA3 transgene under control of the Sir2/3/4 chromatin modification complex, both in cell populations in which it was expressed (cells grown in synthetic medium lacking uracil), as well as those in which it was repressed (cells grown in rich medium containing 5-FOA). As was the case here, the expressed state was characterized by substantial levels of Sir3 and deacetylated H3 and H4. In contrast to our findings, however, other histone modifications – in particular, H3K4me3, H3K36me3 and both mono - and di-methylated forms of H3K79 – were abundant [37]. Based on these and other lines of evidence, the authors speculated that the H3K79me2 mark, while not diminishing the abundance of Sir3 at the expressed URA3-TEL gene, disrupted its physiological interaction with the underlying nucleosomes, thereby accounting for the transcriptionally permissive template [37]. As our data indicate that both hsp82-2001 and YFR057w can be transcribed essentially in the absence of H3K4, H3K36 and H3K79 methylation, an obligatory role for these histone modifications in promoting Pol II transcription of heterochromatic genes seems unlikely.

Instead, our results are more consistent with a large scale mutational analysis in S. cerevisiae which showed that despite the widespread localization of H3K4me, H3K36me and H3K79me marks, deletion of the enzymes responsible for imparting these marks – Set1, Set2 and Dot1 – had very specific effects with the expression of most genes unaffected [70]. Also congruent with our results are observations of Drosophila mutants in which essentially normal transcriptional regulation can occur in the complete absence of H3K4 methylation [71].

A “Fine-Tuning” Role for Histone Modifications in Transcriptional Activation

We have demonstrated that in yeast heterochromatin, substantial increases in transcription can take place in the absence (or near-absence) of chromatin alterations often thought necessary for activation. Nonetheless, gross transcriptional output of hsp82-2001 and YFR057w is reduced several-fold as a consequence of their location within SIR-heterochromatin. Therefore, at least in these two cases, histone modifications may play a role in increasing transcriptional output. Other explanations for how Sir2/3/4 proteins reduce transcription of these genes, including direct or indirect roles in enhancing nucleosome stability [44], are also possible. Whatever the physiological role of histone modifications might be, it is notable that similar to the examples presented here, heat stress-induced activation of heterochromatic transgenes in Arabidopsis occurs without reversal of repressive chromatin marks such as DNA methylation and H3K9 and H3K27 methylation, and without the appearance of activating modifications such as H3 and H4 acetylation [72]. Therefore, absence of activating histone modifications may be a common feature of stress-induced heterochromatic transcription.

Materials and Methods

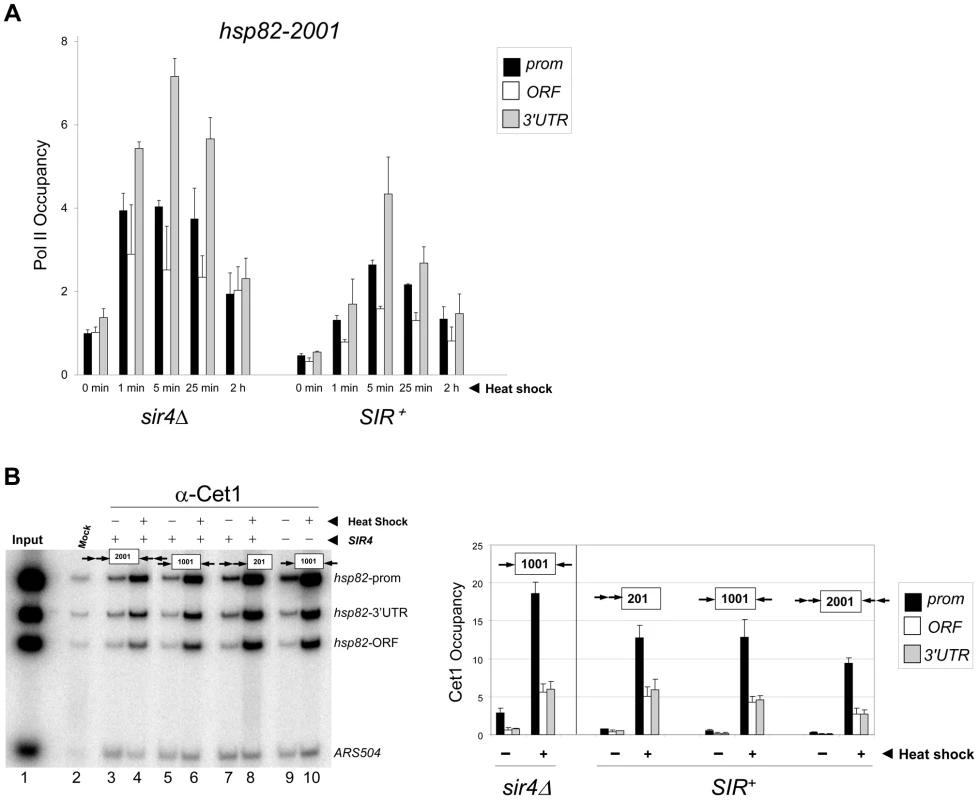

Yeast Strains

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The hsp82 transgenic strains (SLY101 background) were generated by integrating HMRE silencers (144 bp modules [separated by 6 bp spacers in the case of tandem integrants]) both 5′ and 3′ of the chromosomal HSP82 gene using two-step gene transplacement methods [33]. To permit expression of Myc-tagged histone H4, strains were transformed with an episomal myc-HHF2 gene borne on plasmid pNOY436 (TRP1-CEN6-ARS4) as previously described [38]. Strains MSY529 and MSY541 were gifts of M.M. Smith (University of Virginia).

Cultivation and Induction Conditions

Yeast strains were cultivated at 30°C to early log phase (A600 = 0.3 to 0.7) in either rich yeast extract-peptone-glucose broth supplemented with 0.03 mg/ml adenine or synthetic complete medium lacking tryptophan (SDC-Trp). Heat shock induction was achieved by transferring the culture (typically 50 ml) to a vigorously shaking 39°C water bath; once the temperature reached 39°C, incubation was allowed to continue for an additional 20 min before addition of either sodium azide (to a 20 mM final concentration (RNA assays)) or formaldehyde (to a 1% final concentration (ChIP)). For time course assays, instantaneous 30° to 39°C upshift was achieved by rapidly mixing equal volumes of 30°C culture and pre-warmed medium (55°C) and then incubating with rapid shaking at 39°C for the times indicated. Induction was terminated through addition of sodium azide.

For drug induction, 100 ml early log cultures (A600 ∼0.6) were made 200 µg/ml in cycloheximide through a 1∶100 dilution of a 20 mg/ml stock solution prepared in DMSO. Cells were then incubated with agitation at 30°C for various times (indicated in Figure legends) prior to addition of 20 mM sodium azide. Cells were then harvested, washed in 20 mM azide, and stored at −80°C for subsequent chromatin or RNA isolation.

ChIP Analysis

End point (gel-based) ChIP-PCR analysis (Figures 2A, 3B, 4B, 4C, 4E–G, 7A, S1A) was conducted essentially as described [42]. Briefly, 50 ml of mid-log culture (A600 ∼0.5) were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min, then converted to spheroplasts with lyticase (4 mg/ml; Sigma). Spheroplasts were lysed using one volume of 0.5 mm glass beads for 30 min at 4°C on an Eppendorf 5432 mixer. Chromatin was sheared to a mean size of ∼0.5 kb with a Branson 250 sonifier equipped with a microtip using three 25 s pulses at constant power and an output setting of 22 watts. The clarified supernatant (final volume 3.0 ml) was used in immunoprecipitations (IPs) that were typically achieved by adding 2–5 µl antiserum to 300 µl of chromatin lysate. Signal quantification was done using a Storm 860 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) and ImageQuant 5.2 software. To calculate the relative abundance of a given gene sequence present in an IP, we used the following formula: Qgene = IPgene/Inputgene. In most cases, the abundance of each test locus was expressed relative to that of either PHO5 or ARS504, which served as internal recovery controls. In the case of Sir3, abundance at a given locus was quantified relative to its abundance at HMRa1. To reduce background, we subtracted the signal arising from a mock IP (-Ab) for the histone covalent modification, Htz1 and Cet1 ChIPs, and the signal arising from pre-immune serum for the Pol II (Rpb1) ChIPs. For the nonspecific ARS504 IP signal, only gel background was subtracted.

Real Time (ChIP-qPCR) analysis (Figures 2B, 2C, 3A, 5, 6, 8[B–F], 9[B–E], S3) was conducted as follows. Briefly, 125 ml of mid-log cell culture were used and 25 ml aliquots were removed for each time point. Two ml crosslinked chromatin were obtained from each, and ∼10% of that (200–250 µl) was employed for each IP. For all ChIP-qPCR assays, chromatin was isolated as above except cells were lysed with glass beads in the presence of 1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% sodium deoxycholate. Immunoprecipitations were conducted through addition of 40 µl of a 50% slurry of CL-4B Protein A Sepharose beads, with incubation at 4°C overnight. Following immunoprecipitation, DNA was purified and dissolved in 60 µl TE; 2 µl of immunoprecipitated DNA added to each 20 µl Real Time PCR reaction. This was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Real-Time PCR system using RT2 qPCR SYBR Green/ROX MasterMix (SABiosciences; #330529). Through use of a standard curve specific for each amplicon, the quantity of DNA present in each IP was determined, and background signal was subtracted. In the case of Myc ChIPs, the background was the signal arising from chromatin isolated in a parallel culture of an isogenic strain lacking Myc-tagged H4; for histone PTM ChIPs, background was the signal arising from a beads alone control. For Pol II ChIP, background was the signal arising from pre-immune serum. To normalize for variation in sample recovery, abundance of a non-transcribed region on chromosome V (ARS504) was determined for each ChIP DNA sample, and HSP82/ARS504 and YFR057w/ARS504 quotients were derived. In certain cases (see figure legends), normalization to the PHO5 promoter was done instead. Finally, to account for nucleosome loss, all PTM data are presented as (histone PTM)/Myc-H4 or (histone PTM)/H3 quotients.

The following antibodies were used: Myc (MAb 9E10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); H3 globular domain (ab1791, Abcam); H3 K9ac, K14ac (12-360; Millipore); H3 K18ac (ab1191; Abcam); H3 K56ac (gift of M. Grunstein, UCLA); H4 K16ac (07-329, Millipore); H4 K12ac (07-595, Millipore); H4 tetra-acetylated (K5, K8, K12, K16) (06-866, Millipore); H2A acidic patch (residues 88-97; 07-146, Millipore); H3 K4me3 (ab8580; Abcam); H3 K4me2,3 (ab6000; Abcam); H3 K36me3 (ab9050; Abcam); H3 K79me2 (ab3594; Abcam); Htz1 (residues 1–100; ab4626; Abcam); Cet1 (gift of S. Buratowski, Harvard Medical School); Sir3 (gift of R.T. Kamakaka, University of California, Santa Cruz); Pol II, rabbit antiserum raised in our laboratory against a recombinant GST-CTD polypeptide bearing 52 heptad repeats of the mouse large subunit [38].

Amplicons for endpoint PCR were as follows (coordinates relative to ATG): HSP82 promoter, −401 to −34; HSP82 ORF, +1248 to +1444; HSP82 3′-UTR, +1883 to +2155; ARS504, coordinates 9746 to 9817; PHO5 promoter, −507 to −33; CIN2 5′ ORF, +149 to +427; CIN2 3′-UTR, +523 to +797; YAR1 ORF, +3 to +200; YAR1 3′-UTR, +1109 to +1297); IQG1 5′ ORF, +1016 to +1211; IQG1 3′ ORF, +2007 to +2289; SUI3, +451 to +748; YPL236c, +71 to +229; HMRa1, −80 to +50. For Real Time PCR, the amplicons were: HSP82 UAS, −227 to −140; HSP82 promoter, −157 to −88 or −227 to −88 (Figures 2B, 2C, 6C–E); HSP82 ORF, +1248 to +1444; HSP82 3′-UTR, +2134 to +2228; YFR057w promoter, −115 to −45; YFR057w ORF, +312 to +437; ARS504, coordinates 9746 to 9817; PHO5 promoter, −197 to −124; PMA1 5′-coding region, +49 to +112.

Northern Analysis

For the expression analyses summarized in Figure 1B and illustrated in Figures 4D and S1[B-E], RNA was isolated from 10 ml aliquots of cell culture employed for ChIP assays using the glass bead lysis method [73], and blots were hybridized to a gene-specific probe, exposed to PhosphorImager, then re-hybridized to an ACT1 probe as done previously [42]. Probes used were as follows: HSP82, +2167 to +2228; CIN2, +149 to +427; YAR1, +3 to +200; SUI3, +451 to +748; IQG1, +1016 to +1211; and ACT1, +606 to +1000.

RT-qPCR Analysis

For the expression analyses illustrated in Figures 4A, 7B and 8A, cells were cultivated to an A600 of ∼0.5 in a 125 ml culture at 30°C and 15 ml aliquots were removed and subjected to an instantaneous 30 to 39°C upshift for the indicated times. Heat shock induction was terminated through addition of 20 mM sodium azide, and RNA was isolated as above. For induction of YFR057w (Figures 9A, S4), cycloheximide was added to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/ml, 15 ml aliquots were removed at the indicated times and RNA was isolated.

Contaminating genomic DNA was removed from each RNA sample by digestion with RNase-free DNase I (OMEGA Bio-tek Inc #E1091), followed by phenol/chloroform extraction. 0.5 µg purified RNA was used in each cDNA synthesis with ProtoScript RT-PCR Kit (NEB #E6400S). Oligo(dT) primers were used in cDNA synthesis for quantification of Pol II gene transcripts; random primers were used in cDNA synthesis for quantification of SCR1 RNA. 2% of the synthesized cDNA was used in each qPCR, which was performed as described above. Primers were designed to target the 3′UTR of HSP82, YFR057w and PMA1, or the body of SCR1. Their coordinates are: HSP82, +2134 to +2228; YFR057w, +312 to +437; PMA1, +2998 to +3083 and SCR1, +385 to +483. For quantification, SCR1 was used to normalize HSP82 and YFR057w mRNA levels.

Supporting Information

Zdroje

1. ElginSCR (1988) The formation and function of DNase hypersensitive sites in the process of gene activation. J Biol Chem 263 : 19259–19262.

2. GrossDS, GarrardWT (1988) Nuclease hypersensitive sites in chromatin. Annu Rev Biochem 57 : 159–197.

3. WeinerA, HughesA, YassourM, RandoOJ, FriedmanN (2010) High-resolution nucleosome mapping reveals transcription-dependent promoter packaging. Genome Res 20 : 90–100.

4. XiY, YaoJ, ChenR, LiW, HeX (2011) Nucleosome fragility reveals novel functional states of chromatin and poises genes for activation. Genome Res 21 : 718–724.

5. LeeDY, HayesJJ, PrussD, WolffeAP (1993) A positive role for histone acetylation in transcription factor access to nucleosomal DNA. Cell 72 : 73–84.

6. LugerK, MaderAW, RichmondRK, SargentDF, RichmondTJ (1997) Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature 389 : 251–260.

7. Shogren-KnaakM, IshiiH, SunJM, PazinMJ, DavieJR, et al. (2006) Histone H4-K16 acetylation controls chromatin structure and protein interactions. Science 311 : 844–847.

8. GovindCK, QiuH, GinsburgDS, RuanC, HofmeyerK, et al. (2010) Phosphorylated Pol II CTD recruits multiple HDACs, including Rpd3C(S), for methylation-dependent deacetylation of ORF nucleosomes. Mol Cell 39 : 234–246.

9. JenuweinT, AllisCD (2001) Translating the histone code. Science 293 : 1074–1080.

10. StrahlBD, AllisCD (2000) The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403 : 41–45.

11. LoWS, DugganL, EmreNC, BelotserkovskyaR, LaneWS, et al. (2001) Snf1–a histone kinase that works in concert with the histone acetyltransferase Gcn5 to regulate transcription. Science 293 : 1142–1146.

12. BungardD, FuerthBJ, ZengPY, FaubertB, MaasNL, et al. (2010) Signaling kinase AMPK activates stress-promoted transcription via histone H2B phosphorylation. Science 329 : 1201–1205.

13. RuthenburgAJ, LiH, MilneTA, DewellS, McGintyRK, et al. (2011) Recognition of a mononucleosomal histone modification pattern by BPTF via multivalent interactions. Cell 145 : 692–706.

14. KouzaridesT (2007) Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 128 : 693–705.

15. SmithE, ShilatifardA (2010) The chromatin signaling pathway: diverse mechanisms of recruitment of histone-modifying enzymes and varied biological outcomes. Mol Cell 40 : 689–701.

16. PtashneM (2013) Epigenetics: core misconcept. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 : 7101–7103.

17. HenikoffS, ShilatifardA (2011) Histone modification: cause or cog? Trends Genet 27 : 389–396.

18. TrojerP, ReinbergD (2007) Facultative heterochromatin: is there a distinctive molecular signature? Mol Cell 28 : 1–13.

19. ZhaoJ, SunBK, ErwinJA, SongJJ, LeeJT (2008) Polycomb proteins targeted by a short repeat RNA to the mouse X chromosome. Science 322 : 750–756.

20. SimonJA, KingstonRE (2013) Occupying chromatin: Polycomb mechanisms for getting to genomic targets, stopping transcriptional traffic, and staying put. Mol Cell 49 : 808–824.

21. PirrottaV, GrossDS (2005) Epigenetic silencing mechanisms in budding yeast and fruit fly: different paths, same destinations. Mol Cell 18 : 395–398.

22. RuscheLN, KirchmaierAL, RineJ (2003) The establishment, inheritance, and function of silenced chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ann Rev Biochem 72 : 481–516.

23. OppikoferM, KuengS, GasserSM (2013) SIR-nucleosome interactions: Structure-function relationships in yeast silent chromatin. Gene 527 : 10–25.

24. SekingerEA, GrossDS (2001) Silenced chromatin is permissive to activator binding and PIC recruitment. Cell 105 : 403–414.

25. HoppeGJ, TannyJC, RudnerAD, GerberSA, DanaieS, et al. (2002) Steps in assembly of silent chromatin in yeast: Sir3-independent binding of a Sir2/Sir4 complex to silencers and role for Sir2-dependent deacetylation. Mol Cell Biol 22 : 4167–4180.

26. RuscheLN, KirchmaierAL, RineJ (2002) Ordered nucleation and spreading of silenced chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 13 : 2207–2222.

27. XuF, ZhangQ, ZhangK, XieW, GrunsteinM (2007) Sir2 deacetylates histone H3 lysine 56 to regulate telomeric heterochromatin structure in yeast. Mol Cell 27 : 890–900.

28. MoazedD (2001) Common themes in the mechanisms of gene silencing. Mol Cell 8 : 489–498.

29. YasuharaJC, WakimotoBT (2006) Oxymoron no more: the expanding world of heterochromatic genes. Trends Genet 22 : 330–338.

30. LeeJT (2010) The X as model for RNA's niche in epigenomic regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2: a003749.

31. HornD (2009) Antigenic variation: extending the reach of telomeric silencing. Curr Biol 19: R496–498.

32. LeeS, GrossDS (1993) Conditional silencing: The HMRE mating-type silencer exerts a rapidly reversible position effect on the yeast HSP82 heat shock gene. Mol Cell Biol 13 : 727–738.

33. SekingerEA, GrossDS (1999) SIR repression of a yeast heat shock gene: UAS and TATA footprints persist within heterochromatin. EMBO J 18 : 7041–7055.

34. LooS, RineJ (1994) Silencers and domains of generalized repression. Science 264 : 1768–1771.

35. DonzeD, AdamsCR, RineJ, KamakakaRT (1999) The boundaries of the silenced HMR domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 13 : 698–708.

36. BiX, BroachJR (1999) UASrpg can function as heterochromatin boundary element in yeast. Genes Dev 13 : 1089–1101.

37. KitadaT, KuryanBG, TranNN, SongC, XueY, et al. (2012) Mechanism for epigenetic variegation of gene expression at yeast telomeric heterochromatin. Genes Dev 26 : 2443–2455.

38. ZhaoJ, Herrera-DiazJ, GrossDS (2005) Domain-wide displacement of histones by activated heat shock factor occurs independently of Swi/Snf and is not correlated with RNA polymerase II density. Mol Cell Biol 25 : 8985–8999.

39. KremerSB, KimS, JeongJO, MoustafaYM, ChenA, et al. (2012) Role of Mediator in regulating Pol II elongation and nucleosome displacement in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 191 : 95–106.

40. KimS, GrossDS (2013) Mediator recruitment to heat shock genes requires dual Hsf1 activation domains and Mediator Tail subunits Med15 and Med16. J Biol Chem 288 : 12197–12213.

41. SteinmetzEJ, WarrenCL, KuehnerJN, PanbehiB, AnsariAZ, et al. (2006) Genome-wide distribution of yeast RNA polymerase II and its control by Sen1 helicase. Mol Cell 24 : 735–746.

42. GaoL, GrossDS (2008) Sir2 silences gene transcription by targeting the transition between RNA polymerase II initiation and elongation. Mol Cell Biol 28 : 3979–3994.

43. VarvS, KristjuhanK, PeilK, LookeM, MahlakoivT, et al. (2010) Acetylation of H3 K56 is required for RNA polymerase II transcript elongation through heterochromatin in yeast. Mol Cell Biol 30 : 1467–1477.

44. JohnsonA, WuR, PeetzM, GygiSP, MoazedD (2013) Heterochromatic gene silencing by activator interference and a transcription elongation barrier. J Biol Chem 288 : 28771–28782.

45. KremerSB, GrossDS (2009) SAGA and Rpd3 chromatin modification complexes dynamically regulate heat shock gene structure and expression. J Biol Chem 284 : 32914–32931.

46. VidaliG, BoffaLC, BradburyEM, AllfreyVG (1978) Butyrate suppression of histone deacetylation leads to accumulation of multiacetylated forms of histones H3 and H4 and increased DNase I sensitivity of the associated DNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 75 : 2239–2243.

47. LiB, CareyM, WorkmanJL (2007) The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 128 : 707–719.

48. ZhouBO, WangSS, ZhangY, FuXH, DangW, et al. (2011) Histone H4 lysine 12 acetylation regulates telomeric heterochromatin plasticity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet 7: e1001272.

49. XuF, ZhangK, GrunsteinM (2005) Acetylation in histone H3 globular domain regulates gene expression in yeast. Cell 121 : 375–385.

50. VenkateshS, SmolleM, LiH, GogolMM, SaintM, et al. (2012) Set2 methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 suppresses histone exchange on transcribed genes. Nature 489 : 452–455.

51. WilliamsSK, TruongD, TylerJK (2008) Acetylation in the globular core of histone H3 on lysine-56 promotes chromatin disassembly during transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 : 9000–9005.

52. GuentherMG, LevineSS, BoyerLA, JaenischR, YoungRA (2007) A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell 130 : 77–88.

53. ShilatifardA (2008) Molecular implementation and physiological roles for histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20 : 341–348.

54. ShahbazianMD, ZhangK, GrunsteinM (2005) Histone H2B ubiquitylation controls processive methylation but not monomethylation by Dot1 and Set1. Mol Cell 19 : 271–277.

55. GuertinMJ, MartinsAL, SiepelA, LisJT (2012) Accurate prediction of inducible transcription factor binding intensities in vivo. PLoS Genet 8: e1002610.

56. ZhangH, RobertsDN, CairnsBR (2005) Genome-wide dynamics of Htz1, a histone H2A variant that poises repressed/basal promoters for activation through histone loss. Cell 123 : 219–231.

57. RaisnerRM, HartleyPD, MeneghiniMD, BaoMZ, LiuCL, et al. (2005) Histone variant H2A.Z marks the 5′ ends of both active and inactive genes in euchromatin. Cell 123 : 233–248.

58. GrantPA, EberharterA, JohnS, CookRG, TurnerBM, et al. (1999) Expanded lysine acetylation specificity of Gcn5 in native complexes. J Biol Chem 274 : 5895–5900.

59. JinQ, YuLR, WangL, ZhangZ, KasperLH, et al. (2010) Distinct roles of GCN5/PCAF-mediated H3K9ac and CBP/p300-mediated H3K18/27ac in nuclear receptor transactivation. EMBO J 30 : 249–262.

60. ErkinaTY, ErkineAM (2006) Displacement of histones at promoters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae heat shock genes is differentially associated with histone H3 acetylation. Mol Cell Biol 26 : 7587–7600.

61. Strahl-BolsingerS, HechtA, LuoK, GrunsteinM (1997) SIR2 and SIR4 interactions differ in core and extended telomeric heterochromatin in yeast. Genes Dev 11 : 83–93.

62. Vega-PalasMA, Martin-FigueroaE, FlorencioFJ (2000) Telomeric silencing of a natural subtelomeric gene. Mol Gen Genet 263 : 287–291.

63. ShahiP, GulshanK, NaarAM, Moye-RowleyWS (2010) Differential roles of transcriptional mediator subunits in regulation of multidrug resistance gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 21 : 2469–2482.

64. TeboJ, DerS, FrevelM, KhabarKS, WilliamsBR, et al. (2003) Heterogeneity in control of mRNA stability by AU-rich elements. J Biol Chem 278 : 12085–12093.

65. JiangC, PughBF (2009) A compiled and systematic reference map of nucleosome positions across the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Genome Biol 10: R109.

66. TavernaSD, LiH, RuthenburgAJ, AllisCD, PatelDJ (2007) How chromatin-binding modules interpret histone modifications: lessons from professional pocket pickers. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14 : 1025–1040.

67. GrossDS, AdamsCC, LeeS, StentzB (1993) A critical role for heat shock transcription factor in establishing a nucleosome-free region over the TATA-initiation site of the yeast HSP82 heat shock gene. EMBO J 12 : 3931–3945.

68. ErkineAM, MagroganSF, SekingerEA, GrossDS (1999) Cooperative binding of heat shock factor to the yeast HSP82 promoter in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell Biol 19 : 1627–1639.

69. PtashneM, GannA (1997) Transcriptional activation by recruitment. Nature 386 : 569–577.

70. LenstraTL, BenschopJJ, KimT, SchulzeJM, BrabersNA, et al. (2011) The specificity and topology of chromatin interaction pathways in yeast. Mol Cell 42 : 536–549.

71. HodlM, BaslerK (2012) Transcription in the absence of histone H3.2 and H3K4 methylation. Curr Biol 22 : 2253–2257.

72. Tittel-ElmerM, BucherE, BrogerL, MathieuO, PaszkowskiJ, et al. (2010) Stress-induced activation of heterochromatic transcription. PLoS Genet 6: e1001175.

73. Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, et al.. (1995) Current Protocols in Molecular Biology: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

74. FarrellyFW, FinkelsteinDB (1984) Complete sequence of heat shock-inducible HSP90 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 259 : 5745–5751.

75. MegeePC, MorganBA, MittmanBA, SmithMM (1990) Genetic analysis of histone H4: essential role of lysines subject to reversible acetylation. Science 247 : 841–845.

Štítky

Genetika Reprodukčná medicína

Článok vyšiel v časopisePLOS Genetics

Najčítanejšie tento týždeň

2014 Číslo 4- Gynekologové a odborníci na reprodukční medicínu se sejdou na prvním virtuálním summitu

- Je „freeze-all“ pro všechny? Odborníci na fertilitu diskutovali na virtuálním summitu

-

Všetky články tohto čísla

- The Challenges of Mitochondrial Replacement

- Concocting Cholinergy

- Genome-Wide Diet-Gene Interaction Analyses for Risk of Colorectal Cancer

- Statistical Power to Detect Genetic (Co)Variance of Complex Traits Using SNP Data in Unrelated Samples

- Mouse Pulmonary Adenoma Susceptibility 1 Locus Is an Expression QTL Modulating -4A

- Transcription-Associated R-Loop Formation across the Human CGG-Repeat Region

- Epigenetic Regulation by Heritable RNA

- Protein Quantitative Trait Loci Identify Novel Candidates Modulating Cellular Response to Chemotherapy

- Genome-Wide Profiling of Yeast DNA:RNA Hybrid Prone Sites with DRIP-Chip

- The Mechanism of Gene Targeting in Human Somatic Cells

- A LINE-1 Insertion in DLX6 Is Responsible for Cleft Palate and Mandibular Abnormalities in a Canine Model of Pierre Robin Sequence

- Interaction between Two Timing MicroRNAs Controls Trichome Distribution in

- DNA Glycosylases Involved in Base Excision Repair May Be Associated with Cancer Risk in and Mutation Carriers

- The Myc-Mondo/Mad Complexes Integrate Diverse Longevity Signals

- Evolutionarily Diverged Regulation of X-chromosomal Genes as a Primal Event in Mouse Reproductive Isolation

- Mutations in Conserved Residues of the microRNA Argonaute ALG-1 Identify Separable Functions in ALG-1 miRISC Loading and Target Repression

- Genetic Predisposition to In Situ and Invasive Lobular Carcinoma of the Breast

- Isl1 Directly Controls a Cholinergic Neuronal Identity in the Developing Forebrain and Spinal Cord by Forming Cell Type-Specific Complexes

- A Synthetic Community Approach Reveals Plant Genotypes Affecting the Phyllosphere Microbiota

- The Sequence-Specific Transcription Factor c-Jun Targets Cockayne Syndrome Protein B to Regulate Transcription and Chromatin Structure

- Determining the Control Circuitry of Redox Metabolism at the Genome-Scale

- DNA Repair Pathway Selection Caused by Defects in , , and Telomere Addition Generates Specific Chromosomal Rearrangement Signatures

- Methylome Diversification through Changes in DNA Methyltransferase Sequence Specificity

- Folliculin Regulates Ampk-Dependent Autophagy and Metabolic Stress Survival

- Fine Mapping of Dominant -Linked Incompatibility Alleles in Hybrids

- Unexpected Role of the Steroid-Deficiency Protein Ecdysoneless in Pre-mRNA Splicing

- Three Groups of Transposable Elements with Contrasting Copy Number Dynamics and Host Responses in the Maize ( ssp. ) Genome

- Sox5 Functions as a Fate Switch in Medaka Pigment Cell Development

- Synergistic Interactions between the Molecular and Neuronal Circadian Networks Drive Robust Behavioral Circadian Rhythms in

- Chromatin Landscapes of Retroviral and Transposon Integration Profiles

- Widespread Use of Non-productive Alternative Splice Sites in

- Ras GTPase-Like Protein MglA, a Controller of Bacterial Social-Motility in Myxobacteria, Has Evolved to Control Bacterial Predation by

- Cell Type-Specific Functions of Genes Revealed by Novel Adipocyte and Hepatocyte Circadian Clock Models

- Phenotype Ontologies and Cross-Species Analysis for Translational Research

- Embryogenesis Scales Uniformly across Temperature in Developmentally Diverse Species

- In Pursuit of the Gene: An Interview with James Schwartz

- Molecular Mechanisms of Hypoxic Responses via Unique Roles of Ras1, Cdc24 and Ptp3 in a Human Fungal Pathogen

- Analysis of the Genome and Transcriptome of var. Reveals Complex RNA Expression and Microevolution Leading to Virulence Attenuation

- Genotypic and Functional Impact of HIV-1 Adaptation to Its Host Population during the North American Epidemic

- RNA Editome in Rhesus Macaque Shaped by Purifying Selection

- Proper Actin Ring Formation and Septum Constriction Requires Coordinated Regulation of SIN and MOR Pathways through the Germinal Centre Kinase MST-1

- Interplay of the Serine/Threonine-Kinase StkP and the Paralogs DivIVA and GpsB in Pneumococcal Cell Elongation and Division

- A Quality Control Mechanism Coordinates Meiotic Prophase Events to Promote Crossover Assurance

- CNNM2 Mutations Cause Impaired Brain Development and Seizures in Patients with Hypomagnesemia

- The RNA-Binding Protein QKI Suppresses Cancer-Associated Aberrant Splicing

- Uncoupling Transcription from Covalent Histone Modification

- Rad51–Rad52 Mediated Maintenance of Centromeric Chromatin in

- FRA2A Is a CGG Repeat Expansion Associated with Silencing of

- A General Approach for Haplotype Phasing across the Full Spectrum of Relatedness

- A Novel Highly Divergent Protein Family Identified from a Viviparous Insect by RNA-seq Analysis: A Potential Target for Tsetse Fly-Specific Abortifacients

- A Central Role for in Regulation of Islet Function in Man

- PLOS Genetics

- Archív čísel

- Aktuálne číslo

- Informácie o časopise

Najčítanejšie v tomto čísle- The Sequence-Specific Transcription Factor c-Jun Targets Cockayne Syndrome Protein B to Regulate Transcription and Chromatin Structure

- The Mechanism of Gene Targeting in Human Somatic Cells

- Genetic Predisposition to In Situ and Invasive Lobular Carcinoma of the Breast

- Widespread Use of Non-productive Alternative Splice Sites in

Prihlásenie#ADS_BOTTOM_SCRIPTS#Zabudnuté hesloZadajte e-mailovú adresu, s ktorou ste vytvárali účet. Budú Vám na ňu zasielané informácie k nastaveniu nového hesla.

- Časopisy